#naomi murakawa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

RUHA BENJAMIN AND PRINCETON FACULTY WITNESSES SPEAK OUT ON CLIO HALL SIT-IN (excerpted)

That last paragraph is powerful.

#all real ones#protest#Ruha Benjamin#Princeton University#Princeton#New Jersey#free Palestine#Gaza#Palestine#free Gaza#Divya Cherian#Dan-el Padilla Peralta#end the occupation#student protest#campus protest#Naomi Murakawa

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

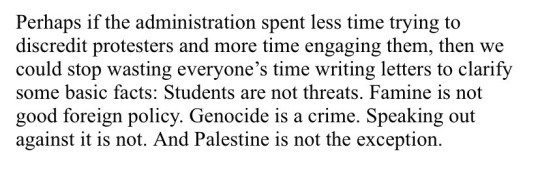

Hey so that reminds me. I have this book — Abolition. Feminism. Now. By Angela Y Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R Meiners, and Beth E Richie, copyright 2022 so very recent — that I have yet to crack open and could use some gentle encouragement to actually read.

And here you are, presumably on tumblr to be entertained, edified, and/or have your brain put through a blender for a few minutes. So let’s have a poll.

[Image descriptions:

Book cover (title and authors as above, abstract background in orange, reddish, and violet tones.)

Back cover. Purple background. Orange and white text reads: “An urgent, vital contribution to the indivisible projects of abolition and feminism, from leading scholar-activists Angela Y David, Gina Dent, Erica R Meiners, and Beth E Richie. As a politic and a practice, abolition increasingly shapes our political moment — halting the construction of new jails and propelling movements to divest from policing. Yet erased from this landscape are not only the central histories of feminist — usually queer, anti capitalist, grassroots, and women of color-led — organizing that continue to cultivate abolition but also a recognition of the stark reality: abolition is our best response to endemic forms of state and interpersonal gender and sexual violence. Amplifying the analysis and the theories of change generated from vibrant community-based organizing, Abolition. Feminism. Now. traces necessary historical genealogies, key internationalist leanings, and everyday practices to grow our collective and flourishing present and futures.

Table of contents. Includes: preface, introduction, part 1 abolition. Part 2 feminism. Part 3 now. Epilogue. Appendices: intimate partner violence and state violence power and control wheel. Incite!-critical resistance statement on gender violence and the prison industrial complex. Reformist reforms vs abolitionist steps to end imprisonment. Further resources. Notes. Image permissions. Index.

list of other books in the abolitionist papers series, edited by Naomi Murakawa, namely: Change Everything: Radical Capitalism and the Case for Abolition by Ruth Wilson Gilmore; Rehearsals for Living by Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson; and We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transformative Justice by Mariame Kaba

Replicated image in the book of a pamphlet cover created by Jeff George and distributed by Survived and Punished (an organization that advocated for incarcerated survivors of abuse.) There is a large line drawing of a scale out of balance with a man in a business suit, large stacks of money, and sky scrapers on the heavy end and a small group of protesters holding a sign saying “free all survivors” on the other end. Large handwritten text says “no good prosecutors now or ever” and smaller stencil-like text says “how the Manhattan district attorney hoards money, perpetuated abuse of survivors, and gags their advocates.”

End image descriptions.]

#It would be so much less effort to just read say 10 or 15 pages of this thing and yet#It’s not a large book it’s under 250 pages#I literally had not cracked open the book before starting the post so I didn’t realize there aren’t ‘chapters’#So much as three main parts

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Not to Think Like a Cop, with Naomi Murakawa

“Naomi Murakawa, a professor of African American Studies at Princeton and the author of The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America.

Naomi talks with us about her J-A roots in Oakland, how her dad’s career in the criminal-legal system got her thinking about carceral politics, why police reform has long been a trap, and the history of hate crimes legislation in the US. She shares her observations on Black Lives Matter, the emergence of abolitionist thinking, and the discourse around “anti-Asian violence.”

What can crime statistics tell us about the world? How do we stop ourselves from thinking like cops? Which groups are pushing Asian America in a more punitive direction? And how should “Asian American history 101” inform our analyses of recent violence?”

Time to Say Goodbye Podcast, April 2021

🔥🔥🔥🔥

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Going over the wave of original ToHeart girls made for the defunct mobile game [ToHeart Heartful Party]

Rea Hanazawa

CV: Tomoko Kaneda - Born October 23

A girl absolutely attached to her phone even when it’s out of charge. Rea loves new and cute things. She devotes most of her time to the daily updates on her blog and become a bit obsessed with the number of hits she’ll receive.

Sakurako Konno

CV: Mai Fuchigami - Born December 1st

A polite honor student who values spending time relaxing. Sakurako radiates a calm atmosphere and never seems to be in a hurry. She’s a member of the tea ceremony club and likes to wear kimono.

Moemi Tsukifune

CV: Sayuri Yahagi - Born November 26

An otaku girl too shy to join the manga club. Moemi is soft spoken and stutters often, unable to convey her feelings. Though when the conversation comes to her interests she becomes incredibly talkative. She's a big fan of doujinshi.

Hina Mitsuhoshi

CV: Anju Inami - Born June 24

A girl who loves instant yakisoba. So much so that her entire body is nearly made up of yakisoba. She has learned everything important in her life from instant yakisoba and can smell instant yakisoba sauce from a mile away.

Yasuko Tsubaki

CV: Yukiyo Fuji - Born April 7

A member of the health committee who is a regular at the infirmary. Yasuko is shown to be quite sickly and collapses often. Though she has a pessimistic outlook on life and feels like she’s going to die, she looks quite healthy.

Maika Marioka

CV: Rie Murakawa - Born April 30

A quiet girl who’s always alone in the library reading books. Maika’s pessimistic about life and has a very negative view of herself. She often tries to avoid people since large crowds feel suffocating.

Krin

CV: Ikumi Nakagami - Born May 18

A student originally from Africa. An adventurous girl excited to learn more about the new world around her (This character unfortunately seems to have a lot of bad stereotypes so I’m keeping it short)

Miya kurohane

CV: Marie Miyake - Born October 31

A cool and mysterious girl. Miya is a self proclaimed 100,016 year old witch who works for the ruler of darkness. Though it seems like a joke at first, her power might actually be real...

Ranju Ayabuki

CV: Yuko Goto - Born June 4

A math teacher quite popular with students. Ranju has a blunt personality and cool demeanor, except when confronted with cute girls. She’s a night owl whose favorite foods are tomato juice and liver.

Yumi Kinjo

CV: Shiho Nakasumi - Born July 20

A calm and easygoing swimmer from Okinawa. Yumi’s the ace of the swim team and highly respected. She actually prefers scuba diving though, and would much rather be swimming by the coral reefs than in a pool.

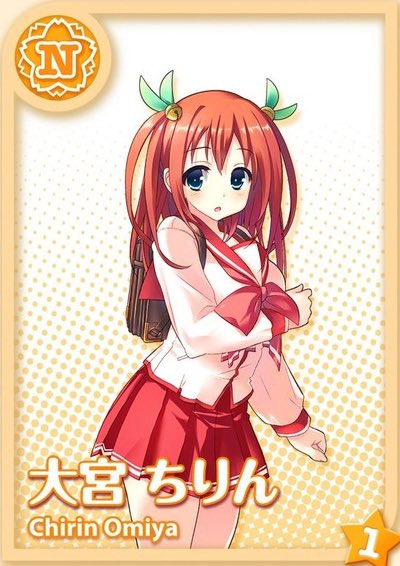

Chirin Omiya

CV: Mai Fuchigami - Born June 16

A good natured girl with a big appetite. Chirin loves to eat and is always up to date on the newest restaurants. However, she worries about her weight and tries to exercise often. This doesn’t stop her love for sweets though.

Mizuho Akatsuki

CV: Natsumi Takamori - Born November 4th

A train otaku attending the nearby private school. Mizuho enjoys all things railway, and doesn’t believe anyone could dislike them. She’s bright and friendly but not great at reading the atmosphere.

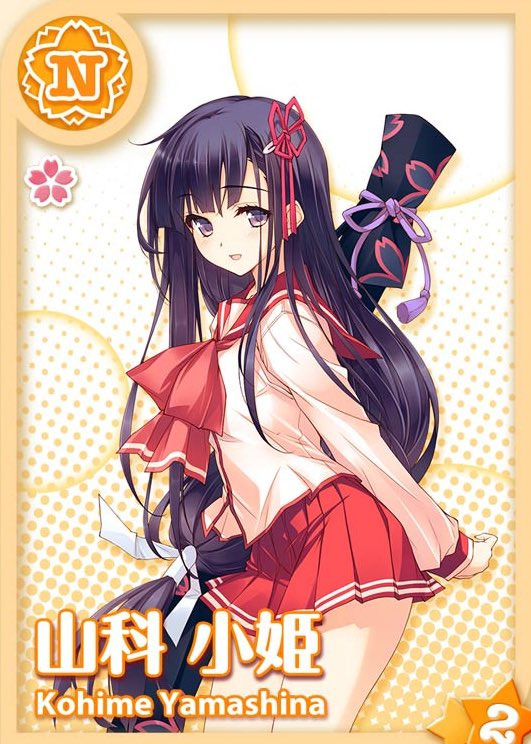

Kohime Yamashina

CV: Naomi Ozora - Born August 16

The daughter of shrine owners in Kyoto. Kohime’s currently training to be a shrine maiden at one near the school. She’s old fashioned but has a lot of interest in foreign cultures. She also likes to draw fortunes.

XAr-10(E) ARTY

CV: Sarah Emi Bridcutt - Born March 25

A police robot developed by a new company. Initially she outperformed Kurusugawa’s robots, but her functions are still immature. ARTY has now been brought to school to be reconditioned as a maid robot for testing.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chosen Family

This year alone, I was able to see Mr. Campos 3 times. I hadn't seen him since I got married about 11 years ago.

The typhoon rains almost made meeting up impossible. The rain was letting up slowly from Sunday through Monday. We spent a lot of time on the group chats trying to excuse him from attending Mari's vow renewal on Monday lunch time.

He still showed up making the drive. Everyone was late and we spent about 4 hours at the restaurant in the hotel. I am sure the wait staff but if there's anything I learned this trip is that some minor inconveniences are okay to savor the moment with the people in front of you.

We spent time talking about everything about Guam, adult lives, history, classmates, trips, and the past. Veronica immediately gelled with Mr. Campos and after everything was said and done, she told me and Mari, I understand the hype and why it's so important for him to continue his presence in your lives.

Below is the vow renewal prayer written by a Queer Pastor:

the blessing—-

Blessed beloveds–

coming and becoming together:

Together, we move in fierce and tender rhythms of care, of solidarity, of joyful alliance.

- We need each other, and we have each other.

- We are from each other; may we be for each other.

Naomi Murakawa asks — Why be a star when you can make a constellation?

Alone, dazzling — one can burn so bright.

But. Beloveds: finding each other, dancing together, we pattern new possibilities.

- Possibilities beyond pain, beyond fear, beyond aloneness.

- Possibilities born of laughter and dream, of refusal and resistance and recreation.

- Possibilities that point us toward sweetness and salve.

We, surrendering into the sacred patterns that heal and hold us.

We, of stardust and spirit and breath.

We, of soil and seeds and spells.

We, of queer and radical rootedness.

Breathing together, we conspire together.

We, of movement and lineage and aliveness that stretches beyond the ages.

We, of elder wisdom and generations yet to come.

We, aligning and realigning into constellations —ancient and emerging— bending our collective life toward freedom.

- Toward the liberating lifeforce of love.

- Toward transformation.

- Toward together.

Until all of us are free,

until we, we, we are free,

until free — we.

This was written by queer pastor and theologian, Anna Blaedel —

Mari talks about how I missed her wedding but still showed up on zoom in my bridesmaid outfit in 2022. She also wanted Campos to preside over her wedding. And their vow renewals taught me that love should always be reflected upon each year. They check in every month what they're doing well and what they need to work on. I am reminder that love is a lot of work and much to work on.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The international Black and Cuba roadshow continues at Princeton University. Professor Naomi Murakawa of the university's African American studies Department included the film and talkback with director Dr. Robin J. Hayes in the graduate seminar, African American Intellectual Traditions. The film is also part of the Princeton library's permanent collection. To screen Black and Cuba in your college classroom, see BlackandCuba.org.

#Princeton#african american studies#robin j hayes#black and cuba#cuba#black radical tradition#naomi murakawa

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly, cop bodycams, at this point, serve a single purpose, which is helping police departments to make their justification narrative more cohesive. The PD waited until the bodycam footage from Duante Wright's murder was available to provide any of the pre-made defenses about it - in this case, 'slips and capture'. With Floyd, they ran with 'excited delirium', the other main one, since their third excuse of 'resisting arrest' wouldn't work.

The fact that the murderer in this case was able to have it on public record that they shouted 'Taser! Taser!' before pulling their gun and killing an innocent person turns that bodycam into an instrument of justification; the same as with every other incident where officers scream 'stop resisting' at someone facedown on the floor.

This has been the whole point of these reforms since the beginning. The bourgeois state doesn't care that the cops are murdering people, they care that the way the cops are murdering people is causing unrest, and to them, the more training and equipment cops have to cover up their executions, the better.

I guess, in short;

"The technique of murder doesn’t comfort the dead. It comforts the executioners—and all their supportive onlookers. Like so much reform to address racism, all this legal fine print is meant to salve the conscience of moderates who want salvation on the cheap..." - Naomi Murakawa

877 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Please for your sake, don’t let a day be a waste

#little dj#japan#novel#film#japanese#kamiki ryunosuke#mayuko fukuda#ryoko hirosue#shigeyuki totsugi#eri murakawa#yoshio harada#ken ishiguro#ken mitsuishi#naomi nishida#yutaka matsushige#katsuya kobayashi#koto nagata#tadashi onitsuka#yuiko miura#drama#romance#day#great#fulfill#sake#you#note to self#advice#movie recommendation

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

R.I.P. (Rest in PDFs), Part II

in progress ...

Part I (A-M) is here.

Note: If you see your work on here and prefer that it not be made freely accessible, please email me at: [email protected], and I will remove it. Thank you!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Naomi Murakawa, The origins of the carceral crisis: Racial order as "law and order" in postwar American politics

Natasha Ginwala, Maps That Don’t Belong

Nathaniel Mackey, Other: From Noun to Verb

Nawal El Saadawi, Woman at Point Zero. Translated by Sherif Hatata.

Nick Estes, Liberation, from Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance

Occupy Poetics. Curated by Thom Donovan

Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment

Patrick Chamoiseau, School Days. Translated from the French by Linda Coverdale

Patrick Wolfe, Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native

Pëtr Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution

Phil Cordelli, New Wave

Phil Cordelli, Tidal State

Poetry of Resistance in Occupied Palestine, translated by Sulafa Hijjawi

Reece Jones, Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right To Move

Rinaldo Walcott, Moving Toward Black Freedom, the first chapter of The Long Emancipation

Rinaldo Walcott, The Problem of the Human: Black Ontologies and “the Coloniality of Our Being”

Rinaldo Walcott, Queer Returns: Human Rights, the AngloCaribbean and Diaspora Politics

Rizvana Bradley, Aesthetic Inhumanisms: Toward an Erotics of Otherworlding

Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman, from CEDE; [Truesse, Unknown Worker, Charles]; Chaos and Rectification

Roberto Tejada, In Relation: The Poetics and Politics of Cuba’s Generation-80

Robin D.G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination

Robin D.G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression

Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse. Translated by Richard Howard.

Roland Barthes, Mythologies. Translated by Annette Lavers.

Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text. Translated by Richard Miller.

Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes. Translated by Richard Howard.

Rosemary Sayigh, Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Fatal Couplings of Power and Difference: Notes on Racism and Geography

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Globalisation and US prison growth: from military Keynesianism to post-Keynesian militarism

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California

Saidiya Hartman, The Plot of Her Undoing (Notes on Feminisms)

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America

Samuel Delaney, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue

Saniya Saleh, Seven Poems. Translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger.

Saniya Saleh, Seven Poems. Various translators

S*an D. Henry-Smith, Flotsam Suite

Shosana Felman & Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History

Simone Browne, Introduction, and Other Dark Matters; Notes on Surveillance Studies; Branding Blackness (from Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness)

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace. Translated by Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr

Simone Weil, The Iliad, or the Poem of Force. Translated by Mary McCarthy

Simone Weil, The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties towards Mankind. Translated by Arthur Wills

Simone Weil, Oppression and Liberty. Translated by Arthur Wills and John Petrie

Simon Leung and Marita Sturken, Displaced Bodies in Residual Spaces

Solidarity Texts: Radiant Re-Sisters

Sophia Terazawa, I Am Not A War

Sora Han, Letters of the Law: Race and the Fantasy of Colorblindness in American Law

#StandingRockSyllabus, compiled by NYC Stands with Standing Rock Collective

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study

Steve Biko, Black Consciousness and the Quest for True Humanity

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, the Black Power chapter of Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America

Sukoon Magazine, Volume 4, Issue 2, Winter 2017

Suzanne Césaire, 1943: Surrealism and Us; The Great Camouflage (from The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent (1941-1945)

Sylvia Wynter, Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World

Sylvia Wynter, “No Humans Involved:” An Open Letter to My Colleagues

Sylvia Wynter, Novel and History, Plot and Plantation

Tamara K. Nopper, The Wages of Non-Blackness: Contemporary Immigrant Rights and Discourses of Character, Productivity, and Value

Tavia Nyong’o, Racial Kitsch and Black Performance

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictee

Thom Donovan, “In The Dirt of the Line”: On Bhanu Kapil’s Intense Autobiography

Tina Campt, Listening to Images

Tina Campt, The Lyric of the Archive

Toni Cade Bambara, The Lesson

Toni Morrison, The Future of Time: Literature and Diminished Expectations

Toni Morrison, Memory, Creation, and Writing

Trinh T. Minh-ha, Documentary Is/Not a Name

Trinh T. Minh-ha, The Walk of Multiplicity

Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism

Veena Das, Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary

Võ Nguyên Giáp, People’s War, People’s Army

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project. Translated from the German by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin

Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa

W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction

W.E.B. Du Bois, The World and Africa: Color and Democracy

Wendy Brown, States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity

Wendy Trevino, Brazilian Is Not A Race

Wendy Trevino, narrative

Winona LaDuke, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Environmental Futures

Worker-Student Action Committees, France May ‘68, by R. Gregoire and F. Perlman

Yanara Friedland, Abraq ad Habra: I will create as I speak

Ye Mimi, eleven poems

Yerbamala Collective, Our Vendetta: Witches vs Fascists

Yi Sang, The Wings. Translated from the Korean by Ahn Jung-hyo and James B. Lee

You Can’t Shoot Us All: On the Oscar Grant Rebellions

Youna Kwak, Home

Yūgen, edited by LeRoi Jones & Hettie Cohen (1958-1962), #1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

Yuri Kochiyama, The Impact of Malcolm X on Asian-American Politics and Activism

Yuri Kochiyama, Then Came the War

Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

6 April 2021

It’s just Andy and Tammy this week, with special guest Naomi Murakawa, a professor of African American Studies at Princeton and the author of The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America.

Naomi talks with us about her J-A roots in Oakland, how her dad’s career in the criminal-legal system got her thinking about carceral politics, why police reform has long been a trap, and the history of hate crimes legislation in the US. She shares her observations on Black Lives Matter, the emergence of abolitionist thinking, and the discourse around “anti-Asian violence.”

What can crime statistics tell us about the world? How do we stop ourselves from thinking like cops? Which groups are pushing Asian America in a more punitive direction? And how should “Asian American history 101” inform our analyses of recent violence?

For those interested in the intersection of the Asian American identity with issue of the criminal justice system, especially with respect to hate crimes, I highly recommend Time to Say Goodbye.

#stop asian hate#anti asian hate#anti asian hate crimes#hate crimes#time to say goodbye#asian american

1 note

·

View note

Link

To understand how these public safety advisors then advanced punitive modernization and the carceral state at home, we must return again to 1947. At the very moment the National Security Act took effect, another crucial document in the history of U.S. law enforcement emerged. The President’s Committee on Civil Rights had been investigating how law enforcement could safeguard civil rights, especially black civil rights, in the United States. The committee’s report to President Harry Truman, To Secure These Rights, advocated for what Mary Dudziak has labeled “cold war civil rights.” It was necessary to ameliorate racial inequality, this argument went, because the Soviet Union frequently invoked lynching and racial abuses to highlight U.S. hypocrisy.

Although the committee was unflinching in its assessment of how the fundamental civil right to the safety of one’s person had been violated frequently (Japanese, Mexicans, and African Americans, as well as members of minority religions, suffered the most), it also understood these problems of racial injustice to be the effect of white extrajudicial violence and “arbitrary” individual actions by cops, particularly in the South. Its solutions were thus focused on strengthening law enforcement and assuring its adherence to due process and administrative fairness. Similar to Kennan, the committee (and the generation of reformers it influenced) believed it was possible to use the tools of policing and prisons fairly, unlike in the Soviet Union.

Political scientist Naomi Murakawa has shown, however, that by framing the problem as arbitrary and as growing out of lawlessness, the committee effectively ruled out the systematic and legally enshrined character of racial abuse. What made it predictable, rather than arbitrary, was its consistent object: racially subjugated peoples. By diminishing the structural aspects of the abuse of minorities, liberal law enforcement reformers opened the door to a wider misunderstanding of what needed to be reformed. The response the committee endorsed—to enact procedural reforms and modernize law enforcement in the United States—rode the high tide of police professionalization initiatives that would crest in the following decades, and which called for a well-endowed, federally sanctioned anticrime apparatus. As historian Elizabeth Hinton and Murakawa have argued, this effort to reform law enforcement and codify its procedures actually made it more institutionally robust and less forgiving, contributing to the country’s march toward mass incarceration.

What is less understood, however, is the fundamental mismatch between what reformers and police chiefs imagined reform to look like. For liberal reformers, injustice looked like a lynch mob. For many police experts, steeped in Cold War ideology and trained in counterintelligence, it looked like the Soviet secret police. Mob rule had to be avoided, but so too did centralized authority over police objectives. Underlying reasons for what police did daily, and to whom, was not the concern of either party.

Command-level cops across the United States, after all, were quick to absorb the lessons and perspectives of public safety officers. In policing’s professional literatures, CIA officials published articles on topics such as policing in the Soviet Union, which emphasized the centralized governing hierarchy. The fact that Soviet police at the lowest level enacted the tyranny ordered at the top resonated with a generation of U.S. police reformers who had watched corrupt political machines in U.S. cities be dismantled. Police reformers thus demanded that police answer primarily to their own professional guidelines, free from political interference. In this way, the negative model of the authoritarian state was misleading: it may have prevented centralized dictatorial rule, but it left police power largely insulated. And so Cold War U.S. empire abroad found its replica in the War on Crime at home: to break the political syzygy of an authoritarian state apparatus in Sacramento or Saigon, in Wichita or Tokyo, police needed to be technically adept, flush with cash, and insulated from political machinations.

[...]

The War on Crime was a creature of federalism. Federal appropriations for upgrading police, courts, and prisons came embroidered with a commitment that no usurpation of local authority or discretion would result. Policing remained decentralized. Even when police killed unarmed people during unrest, causing public complaint, police were protected; outrage could be an orchestrated communist plot, the thinking went, intended to take control over law enforcement by undermining its autonomy. In this way, the reform effort preserved the petty despotism of the nightstick and localized tyranny of the police chief that was at the root of the racial crisis. By insulating police from federal oversight or control, while also affording them increased resources, particularly for capital-intensive repressive technologies, the War on Crime allowed the underlying structure of Jim Crow policing to persist.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backlash: Crime and the Return of Law-and-Order Politics

Talk w/ Naomi Murakawa, author of “The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America” at Socialism Conference 2021

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonfiction Book List

A collection of nonfiction books by Black authors and/or related to intersectional race and gender studies, history, as well as other various topics. The list below is a compilation of various lists I have seen on Instagram, as well as research I’ve done on my own. I am sure I am missing important works, and am happy to add anything that is suggested. This list will be regularly added to and updated.

Race & Anti-Racism

Diangeo, Robin - White Fragility

Eddo-Lodge, Renni - Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race

Kendi, Ibrahim X. - How to Be Anti-Racist

Mahzarin, Banaji & Greenwald, Anthony - Blindspot

Oluo, Ijeoma - So you want to talk about race

Omi and Winant - Racial Formation in the United States

Rankine, Claudia - Citizen

Roberts, Dorothy - Killing the Black Body

Smith, Andrea - Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy

Sowell, Thomas - Black Rednecks and White Liberals

Waheema & Lubiano - The House that Race Built

Ward, Jesmyn - The Fire This Time

Prison Abolition & the Justice System

Alexander, Michelle - The New Jim Crow

Davis, Angela - Are Prisons Obsolete?

Murakawa, Naomi - The First Civil Right

Stefanic & Delgado - Critical Race Theory: An Introduction

Stevenson, Bryan - Just Mercy

Rothstein, Richard - The Color of Law

Policing

Vitale, Alex S. - The End of Policing

Intersectional Feminism

Bambara, Toni Cade - The Black Woman, An Anthology

Carruthers, Charlene - Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements

Cooper, Brittney - Eloquent Rage

Collins, Patricia Hill - Black Feminist Thought

Collins, Patricia Hill - Black Sexual Politics

Cottom, Tressie McMillan - THICK and Other Essays

Crenshaw, Kimberle - On Intersectionality

Davis, Angela - Women, Race, & Class

Davis, Dána-Ain - Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth

Gay, Roxane - Bad Feminist

Gumbs, Alexis Pauline - Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugivity

Hernandez, Ed. Daisy and Rehman, Bushra - Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism

hooks, bell - Ain’t I a Woman

hooks, bell - All About Love

hooks, bell - Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics

Jenkins, Morgan - This Will Be My Undoing

Jones-Rogers, Stephanie E. - They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South

Kendall, Mikki - Hood Feminism

Lorde, Audre - Sister Outsider

Morales, Rosario - This Bridge Called My Back

Morgan, Joan - When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip Hop Feminist Breaks it Down

Oyěwùmí, Oyèrónkẹ́ - The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses

Shakur, Assata - Assata: An Autobiography

Simpson, Leanne Beta - As We Have Always Done

Williamson, Terrion L. - Scandalize My Name: Black Feminist Practice and the Making of Black Social Life

Wilson & Russell - Divided Sisters

Yamahtta-Taylor, Keeanga - How We Get Free

Masculinity

hooks, bell - The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

hooks, bell - We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity

History

Asante Jr., M.A. - It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation

Baldwin, James - The Fire Next Time

Berry, Daina Ramey & Gross, Kali Nicole - A Black Women’s History of the United States

Gates Jr., Henry Louis - Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow

Blackmon, Douglas A. - Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II

Du Bois, W.E.B. - The Souls of Black Folk

Hartman, Saidiya - Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval

Hurston, Zora Neale - Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”

Johnson, E. Patrick - Black, Queer, Southern Women.: An Oral History

Jones-Rogers, Stephanie E. - They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South

Kendi, Ibram X. - Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

Snorton, C. Riley - Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity

Taylor, Candacy A. - Overground Railroad: The Green Book & Roots of Black Travel in America

Washington, Harriet A. - Medical Apartheid

Wilkerson, Isabel - The Warmth of Other Suns

Zinn, Howard - A People’s History of the United States

Politics/Economy

Anderson, Carol - One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy

Baptist, Edward E. - The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism

Psychology

Menakem, Resmaa - My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Mending of Our Bodies and Hearts

Tatum, Beverly Daniel - "Why Are All The Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?": A Psychologist Explains the Development of Racial Identity

Literary Criticism

Morrison, Toni - Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

Education

hooks, bell - Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom

Science & Technology

Benjamin, Ruha - Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code

Skloot, Rebecca - The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Shetterly, Margot Lee - Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race

Autobiography/Memoir

Angelou, Maya - I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

Bernard, Emily - Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother's Time, My Mother's Time, and Mine

Broom, Sarah M. - The Yellow House

Brown, Austin Channing - I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness

Coates, Ta-Nehisi - The Beautiful Struggle

Coates, Ta-Nehisi - Between the World and Me

Hinton, Anthony Ray - The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row

hooks, bell - Bone Black: Memories of Girlhood

Jones, Saeed - How We Fight For Our Lives

Khan-Kullors, Patrisse and Bandele, Asha - When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir

Laymon, Kiese - Heavy: An American Memoir

Mock, Janet - Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More

Noah, Trevor - Born a Crime

Obama, Barack - Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance

Obama, Michelle - Becoming

Shakur, Assata - Assata: An Autobiography

Welteroth, Elaine - More Than Enough

Wright, Richard - Black Boy

X, Malcolm - The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Comedy

Bell, W. Kamau - The Awkward Thoughts of W. Kamau Bell: Tales of a 6' 4", African American, Heterosexual, Cisgender, Left-Leaning, Asthmatic, Black and Proud Blerd, Mama's Boy, Dad, and Stand-Up Comedian

Haddish, Tiffany - The Last Black Unicorn

Rae, Issa - The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl

Robinson, Phoebe - You Can't Touch My Hair: And Other Things I Still Have to Explain

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Learning together while staying apart. Upcoming online events from Haymarket Books (Image above from Just Seeds artists collective)

COVID-19, Decarceration, and Abolition: Ruthie Wilson Gilmore and Naomi Murakawa April 16, 5pm EDT RSVP here

The Pandemic is a Portal: Arundhati Roy April 23, 12pm EDT RSVP here

Previously

Capitalism Is the Disease: Mike Davis on the Coronavirus Crisis Tuesday, March 31, 2020 Andy Hsiao from Verso Books talks with activist-scholar Mike Davis, author of numerous books, including The Monster at Our Door, In Praise of Barbarians, and the forthcoming Set the Night on Fire.

I’ve queued up the video to start when Mike Davis begins discussing the societal and government (local and national) responses to the outbreak in Wuhan China. Davis talks about how governments outside of China are learning the wrong lessons, that you need a semi-totalitarian surveillance society to suppress an outbreak. What mattered in China was the unparalleled fine-grained mobilization network at the neighborhood level.

youtube

[Youtube recording of Capitalism is the Disease starting 25:55]

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Obviously Joe is better than Trump. BUT it is completely irresponsible to suggest that Joe is not a really questionable person and an extremely poor candidate for president. Just some examples: 1) He tried to cut social security several times. 2) His healthcare plan is MORE EXPENSIVE than medicare for all and leaves TEN MILLION PEOPLE UNINSURED. 3) In 2019 he was still supportive of the Hyde amendment. 4) He has a history of touching women and getting in their space, making them CLEARLY

uncomfortable (of course not as bad as many sexual harassment behaviors, but still not something we should ignore) 5) His words: “Whenever people hear the words ‘drugs’ and ‘crime,’ I want them to think ‘Joe Biden.’” Or, to quote criminal punishment historian Naomi Murakawa: “There’s a tendency now to talk about Joe Biden as the sort of affable if inappropriate uncle, as loudmouth and silly… But he’s actually done really deeply disturbing, dangerous reforms that have made the criminal justice

system more lethal and just bigger.” 6) Has a history of lying about his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, most recently in fabricating a story of him getting arrested in South Africa 7) The Obama administration deported more immigrants than any other administration and tore families apart. 7) Has received an F- ON CLIMATE CHANGE from the Sunrise Movement—his climate adviser is a former board member of a natural gas company. 8) He voted for Reagan’s tax cut, and described himself as

“consistent” with his budgetary policies, which were disastrous for the poor of this country. 9) He defended segregationists like Strom Thurmond, worked against busing, welcomed the support of racist, sexist Mike Bloomberg, and has literally helped elect Republican officials like Fred Upton 10) He treated Anita Hill like garbage and is one of the reasons Clarence Thomas is on the Supreme Court. 11) He voted for DOMA 12) He has said that “nothing would fundamentally change" under his admin.

Obama literally picked Joe to be his running mate because he was THE MOST CONSERVATIVE DEMOCRAT who ran for president in 2008. Trump is ALREADY running ads to the left of Biden—on the Iraq War, on Social Security, on NAFTA. Biden has been a truly abysmal campaigner, until the last few weeks when the establishment panicked and threw all their weight behind him.

yes. all of that may be true. i’m not trying to minimize any of that. but he is going to be the nominee whether we like it or not. so we’re gonna have to put all of that aside and realize that we have two choices: biden or trump. that’s it. no third option. and in that case, biden is the better option. unequivocally. and while it’s important that we acknowledge that he isn’t perfect, we need to be aware that the more we drag him down when we are literally on his side, the more ammunition republicans will have to drag him down too. right now, biden seems to be in a really good spot to beat trump and i don’t think bringing up all that stuff is going to help anyone. we need to put smiles on our faces and vote for biden just like all the moderate republicans did with trump. do you really think every single republican wanted to vote for trump? of course not. he’s a monster. but they did it because overall, he was on their side. and biden is on our side whether we like it or not. so you can keep all that stuff in mind, because obviously it’s important that we know who he is, but it’s more important that he is a democrat and if he wins he will have the most progressive agenda in history (according to jon favreau). if you wanna vote for trump over biden then that’s your call but those are the two options that we have and nothing is going to change that.

#politics#i am angry#literally no one likes that it's gonna be biden but we have to swallow our pride and rally behind him like the right did with trump or else#we will tear this party apart from the inside out and then we'll have no chance of beating trump#Anonymous

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I selected The First Civil Right as the title because so often when people are thinking about mass incarceration they begin with Nixon’s understanding of “the first civil right.” He made the phrase famous through his 1968 campaign, in which he said the first civil right of every American is the right of freedom from crime and domestic violence. What was so trenchant and disturbing was he was saying, implicitly, that the first civil right is white freedom from black criminality. And it was as if the other civil rights, the Civil Rights Act, had unleashed this criminality.

Naomi Murakawa - The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America

1 note

·

View note