#music interviews

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It’s very difficult, but it's as simple as remembering that you love these people. Things can get frustrating, there’s more at stake. There’s times where you have to put all of those things aside and just see the five boys [Fontaines D.C.] that would rehearse in a shed. The thing that we wanted to maintain forever was how we felt about each other, and you have to take care of that and make efforts. It’s a relationship. You have to remember why you love someone in the first place. It’s easy to forget sometimes. You have to make efforts to keep that alive in your head.

I have a baby now, and things change in a relationship when you have a baby. Things take on more importance and you can get lost in all that, but my girl and I do these date nights every now and again where we get a babysitter for the night and book a hotel in the city, we don’t go on our phones or anything, we’ll just have our own date. That totally refreshes everything.

I think it’s the same with the boys. We do that sort of thing together. The last time we went on tour, we booked flights maybe a week before the tour started and hung out. I think the tour started in Madrid, so we booked flights to Balbao, and that was all we booked. We said lets just be those five guys again who showed up for a gig and had nowhere to stay. So we flew to Balboa, rented a car at the airport and had nowhere to go, so we just drove out and were like, ‘lets see where this takes us’. We spent a week in Balboa where nothing was planned and it kind of brings you back to when the entire world was these five guys just making the most out of wherever we are or whatever we were doing.

It can feel really strange sometimes. It requires a lot of planning and effort, and it feels very systematic because you have to make the time to do these things, but it’s so important. I do the same thing with my girlfriend with our date nights. When there's so much more at stake than the relationship, it’s easy to lose the relationship.

—Carlos O’Connell on maintaining healthy relationships, whether in Fontaines D.C. or otherwise in life. 7 August 2024 in Monster Children

#carlos o’connell#fontaines d.c.#music#fontaines dc#musicians#interviews#music interviews#Monster Children#relationships#bands

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephen Sanchez

Traveling Troubadour

By Emma Fox

Since his hit single “Until I Found You” went Triple Platinum, generated over 2 billion streams, and made the Top 25 of Billboard Hot 100, Stephen Sanchez has proven himself to be quite the powerhouse in music. Additionally, after the release of his debut album, Angel Face, Sanchez sold out his first ever headline tour, earning acclaim from the likes of Rolling Stone, Vogue, Billboard, and more.

We got the chance to chat with Sanchez following the release of the highly anticipated Angel Face (Club Deluxe), as he anticipates his worldwide fall tour. He discussed influences in songwriting, the depth behind his lyrics, and what we can expect from him down the road.

When asked about his influences and inspirations, Sanchez gave us some insight into a more intimate side of his creative process. Sanchez spoke of the films that he takes inspiration from, specifically Lost in Translation.

He stated that love is a ���wonderful escape from reality a lot of the time, and then love becomes real once you shake off all the clouds.”

Films similar to this one that truly align with his songwriting and storyline as an artist he said are very inspiring, reminding him of “that magic, but also that reality of heartache and of circumstance pulling two people away from each other”.

A lot of Sanchez’s music is known to tug at the heartstrings, and his songs carry a lot of emotional weight within their lyrics. Storytelling is something that Stephen Sanchez does like no other, and for him, it’s exciting to be able to write from real stories and real feelings that have happened in his life, but then to “hide behind a character so it feels like it lessens the blow of vulnerability”.

Sanchez’s album Angel Face follows the story of the fictional musician/character The Troubadour Sanchez, who blew up in 1958 with “Until I Found You” and fell in love with Evangeline in 1964. Angel Face serves as his “long lost debut” that has been unearthed 59 years later.

During our chat, Sanchez was asked about what advice he would have for one of

his listeners if they found their way into a forbidden romance just like Troubadour Sanchez, in order for them to achieve a storybook ending.

Sanchez laughed and responded, “Oh my god, don’t. Don’t do that. Don’t do any of what that character did.”

He continued, “Storybook endings, what even are those? Who even knows? To each their own.”

Finishing his answer with some solid advice, he told listeners to “pursue a thing that’s healthy. They want to know you. You want to know them, that’s it. You’re on the same page”.

As we look ahead and see what the future looks like for Stephen Sanchez, there’s a lot to look forward to with the upcoming fall tour. Sanchez’s first headline tour told the story of Troubadour Sanchez, where on stage Sanchez and his band played the ghosts of the characters existing in the album, haunting each venue and walking fans through the storyline.

This time around however, fans can expect to be taken further back and have the opportunity to experience “the real thing, as if you were back in the 50’s, actually seeing The Troubadour Sanchez and the Moon Crests live.”

The journey and growth of Stephen Sanchez has been an incredible one to watch, and his influence is only continuing to rise. His ability to transform a room, command a stage, and take you back in time with his nostalgic aesthetic, smooth vocal tones, and powerful and emotionally intense songwriting is something that is a true testament to Sanchez’s pure talent and potential. We are so excited to see what he has up his sleeve next!

Copyright ©2024 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved. Posted: September 2, 2024.

Photos by Emily DiMarcangelo © 2023. All rights reserved.

youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ting is in Apple podcasts, also Amazon but can be bothered so screen cap that

#apple podcasts#Podcast#Music interviews#music industry#music history#music#vinyl#london#records#grime#beats#soundcloud#house#food#dj#vinyl collection#vinyl community

0 notes

Text

We BYKE 🕺🏾

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

not very convincing gerard.

#frank iero#gerard way#my chemical romance#mcr#mcredit#yahoo! music exclusive interview#gifs*#*#edit: THIS GIFSET LOOKS SO BAD LOOK AWAY#i should've made the file sizes smaller 🥲

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

RALEIGH RITCHIE????

Link.

#OH MY GOD OH MY GOD#jacob's music in season three????#iwtv#interview with the vampire#jacob anderson#text post

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with the Vampire | 2.01 "What Can the Damned Really Say to the Damned"

#interview with the vampire#iwtvedit#iwtvsource#tvedit#louis de pointe du lac#*#very self indulgent set because#well#i enjoy louis enjoying music

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

— Do you want to hear my story? — Yes.

#interview with the vampire#iwtvedit#iwtv#iwtv spoilers#armand#armandedit#iwtv s2#i apologize for the terrible coloring and lighting i really tried i really did#anyway lots to unpack here#i have thoughts but they are incoherent so y'all get gifs instead#the music at this moment was doing such a clever thing echoing the melody from when he and louis were in the gallery

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

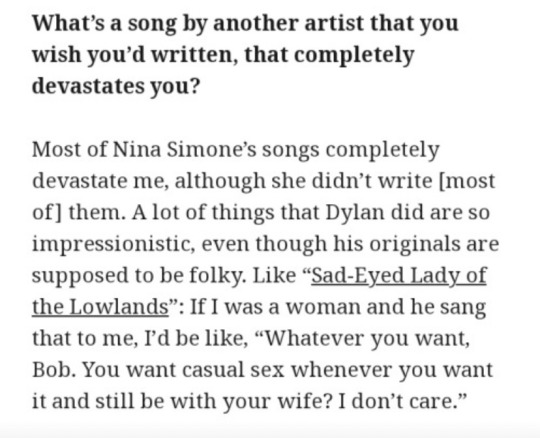

jeff buckley in an interview about bob dylan writing for nina simone. bob dylan’s wrote sad-eyed lady about sara.

#nina simone#indie rock#jeff buckley#music#journaling#love letters#musician#trendingtopics#lover you should've come over#naturecore#bob dylan#rock music#daisy jones and the six#heath ledger#rock n roll#music journalism#peaceful army#lilac wine#interview#witchcraft#aesthetic#artisits on tumblr#artists#pinterest#december#lgtbtq#romantic academia#illustration#cottagecore#eras tour

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

"We recently bought an apartment, a fairly large one, with a small studio inside.

We finally wanted to have our own place to stay. Our friend, the photographer Wolfgang Tilmans, has a very similar apartment. A good 100 years old, with a “Berlin room” in the middle. It was very difficult to get an apartment in Berlin at all. We have bicycles that we like to cycle with in the Tiergarten. Summer is particularly wonderful, of course. In summer everything is great in Berlin. We spend a lot of time outdoors with our bikes, either in the woods or at the lakes in the surrounding area. We particularly like the Schlachtensee, it is the perfect size.

In the studio we spend more time chatting and laughing than making music. The basic mood of the Pet Shop Boys is a furious, cheerful mood."

"Do married couples stay together as long as we do? Not many, right? However, this is more of a friendship than a marriage with us. We like each other but we don't have sex. Okay, some spouses may not either. Anyway: the basis of our relationship is music and we both love good food. We are constantly trying out new restaurants."

Chris Lowe, on him and Neil sharing an apartment, making music together, and on their relationship after 40 years of being a band, resembling that of an old married couple. Interview from 2020.

#Chris Lowe#Neil Tennant#Pet Shop Boys#interviews#PSB interviews#music interviews#original not in English so here's a fan forum linked#music#musicians

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

+ bonus:

Interview With The Vampire + Daniel being horny for Louis

#interview with the vampire#cinematv#filmtvcentral#userthing#smallscreensource#userstream#dailyflicks#tvarchive#filmtvtoday#usersource#chewieblog#tvfilmspot#usertelevision#tvedit#give the people and eric what they want and let them fuck#pls note the slinky jazz music is accompanying this gifset#daniel molloy#louis de pointe du lac#danlou#that under the eyelashes look from luke in the 3rd gif -> how dare you sir!#manifesting luke to return somehow I love him

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE 2.05 "Don't Be Afraid, Just Start the Tape"

#iwtv#iwtv spoilers#iwtvedit#interview with the vampire#vampterview#louis de pointe du lac#armand#daniel molloy#tvedit#tvgifs#*#body horror#this was literally a horror movie scene the music and all

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Off The Record Interview Sessions now on the Spotify so you can listen whenever wherever. Also, shout out Joe Jackson

#Spotify#Podcast#music interview#Music interviews#Djs#Collectors#vinyl collection#Vinyl collectors#Music history#Rare#london

0 notes