#museum wiesbaden

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

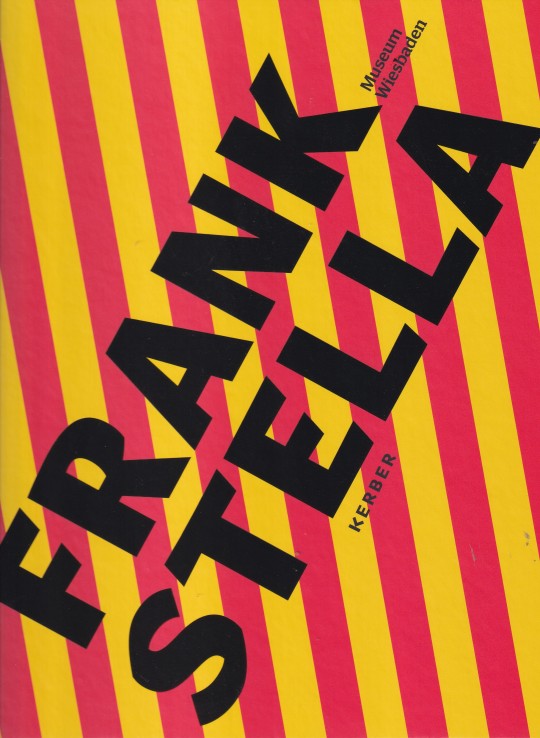

Frank Stella

Editor Jörg Daur, Museum Wiesbaden

Text by Bernard Ceysson, Jörg Daur, Andreas Henning, Lea Schäfer

Design by Frank Bernhard Übler, Leipzig

Kerber, Bielefeld 202, 144 pages, 24x29cm, ISBN 978-3-7356-0873-4

euro 25,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

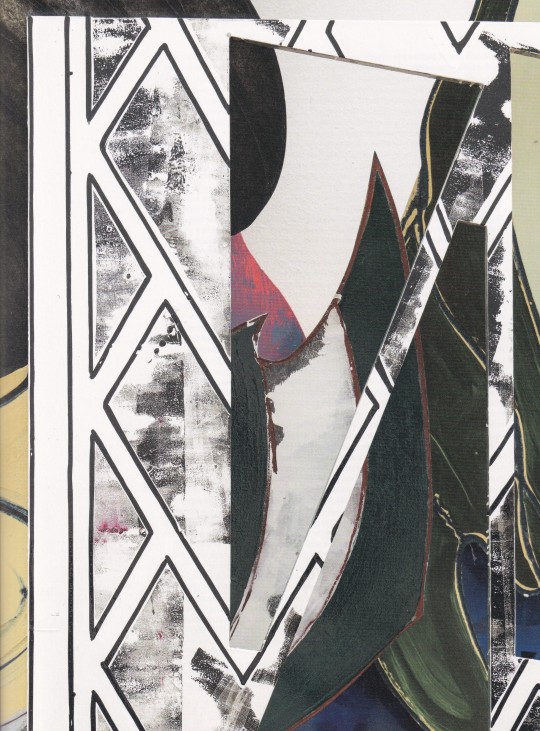

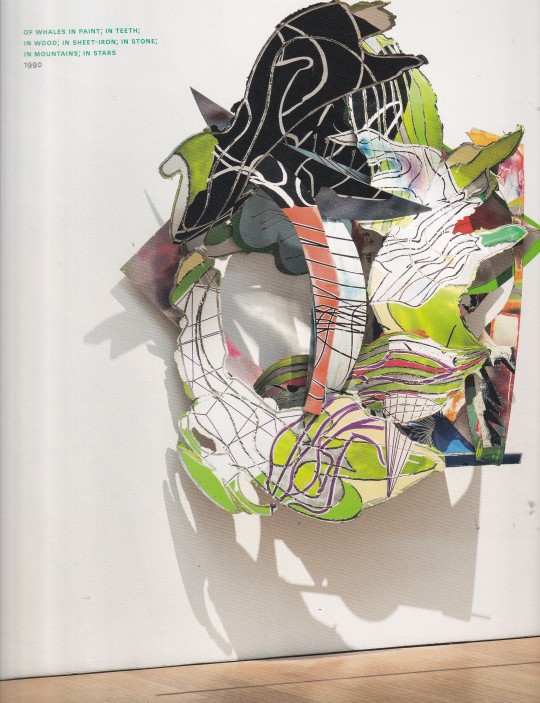

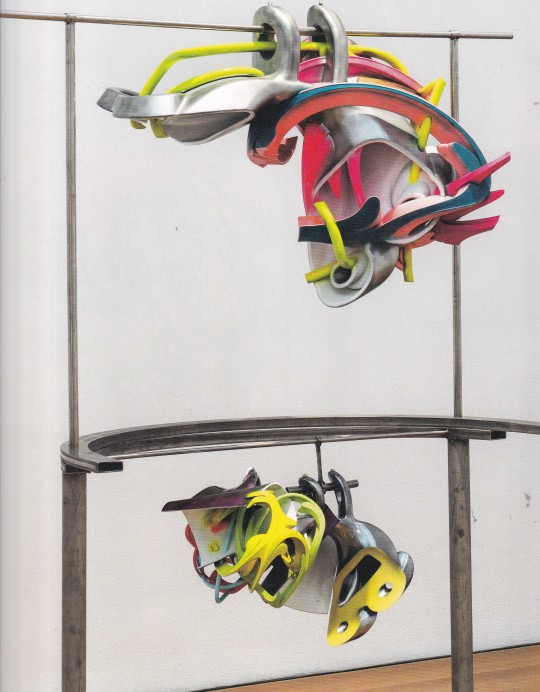

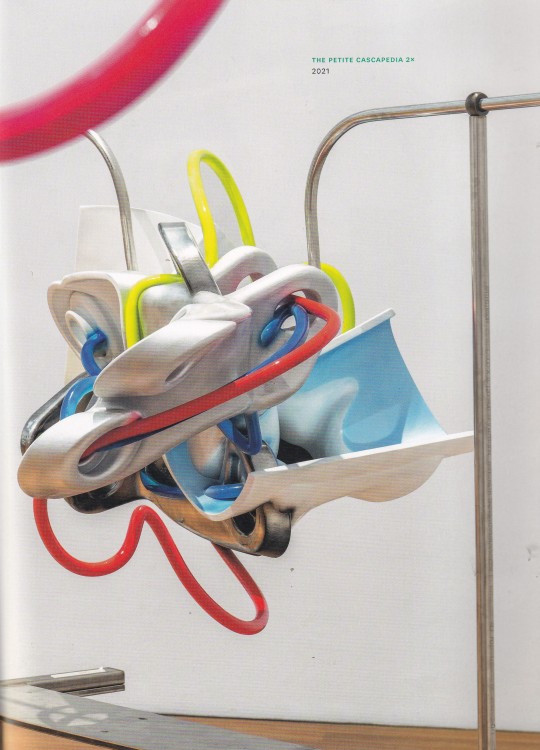

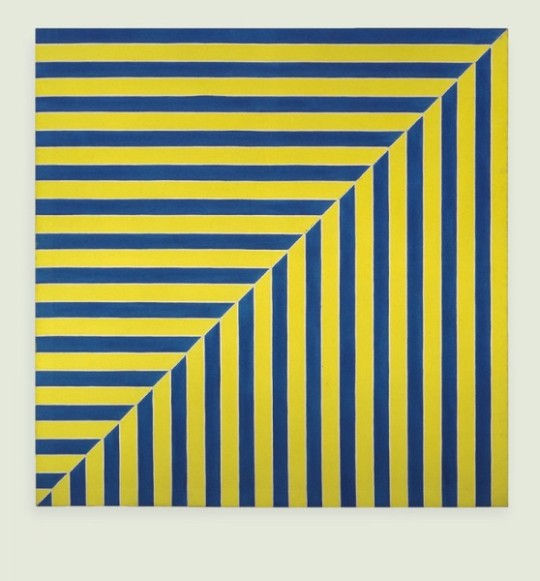

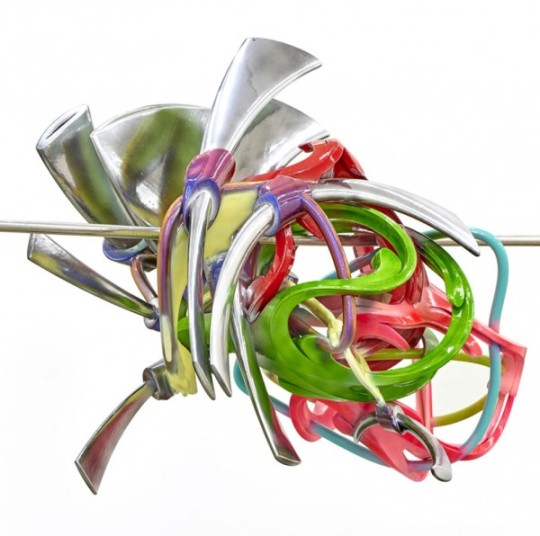

Frank Stella (*1936) situates his oeuvre not only in the present. Abstraction or representation, simulacrum, sign, and ornament, as well as questions of surface and space have fascinated him anew time and again. The publication presents the following phases in his oeuvre in the context of the Museum Wiesbaden’s collection: the early works, the stripe paintings attributed to minimalism, the departure into space, and thus from the picture to the relief, as well as the use of ornament and arabesque. In interplay with current sculptures by the artist, not only the rigorousness of his oeuvre but also the relevance of his work until today is thus shown.

Events Frank Stella. Alexej-von-Jawlensky-Preis 2022, 10.6.–9.10.2022, Museum Wiesbaden

03/02/24

#Frank Stella#art exhibition catalogue#Museum Wiesbaden 2022#stripe paintings#art books#fashionbooksmilano

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tipp: Eröffnung des neuen Kunstmuseums Reinhard Ernst in Wiesbaden

View On WordPress

#Abstrakte Kunst#Esteban Vicente#Karl Otto Götz#Kunstmuseum Wiesbaden#Manuela Mordhorst#Richard Ernst Museum#Wiesbaden

1 note

·

View note

Text

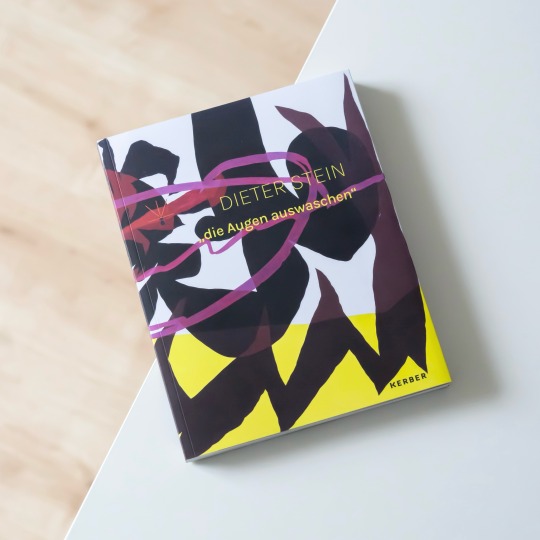

A hundred years after his birth Dieter Stein (1924-2022) remains Würzburg’s most significant abstract artist although his name has largely been forgotten. In 1950 he was the first to present abstract paintings in his rather conservative hometown. During the 1950s and early 1960s Stein also gained recognition through his participation in numerous exhibitions of contemporary art in Germany and beyond: as part of the „Third International Art Exhibition“ his work „8/53“ travelled Japan in 1955, the double exhibition „Biennale 57. Jeune Peinture. Jeune Sculpture“ presented his painting „9/55“ and in July of 1964 his works were presented alongside those of Cy Twombly and Gotthard Graubner in Wiesbaden. By the time Stein had already left behind the firmly contoured shapes, the grids and lines that characterized his work of the 1950s. Instead, his paintings got darker, the compositions more crystalline, differentiated and multi-faceted. At the same time Stein widely stopped taking part in exhibitions and withdrew from the art market, a conscious step he took after reading the critiques of society and capitalism by the Frankfurt School.

Nevertheless, Stein remained a very active and well-connected artist, alas only in Würzburg. That the quality of work remained consistent and just like his earlier works awaits rediscovery demonstrates the current exhibition at Museum Kulturspeicher in Würzburg: up until February 2, 2025 „Dieter Stein. die Augen auswaschen“ offers the opportunity to explore the complete work of the artist. The same goes for the accompanying catalogue, published by Kerber Verlag, that offers those, like the author, who will not make it to the exhibition the same comprehensive overview of Stein’s work. Besides the obligatory illustrations it also includes three very insightful essays that follow the development of Stein’s oeuvre up until his very late works, situate his 1950s work in the context of German abstract art and trace his few but impressive wall paintings. Interestingly the catalogue also doesn’t leave out Stein’s figurative works on paper, a very different but intriguing body of work whose presentation rounds out this informative catalogue.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

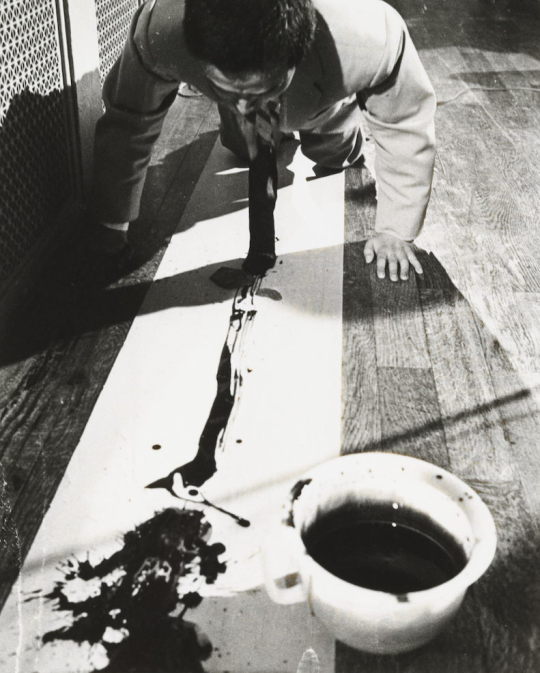

La Monte Young's Composition 1960 #10 performed by Nam June Paik during Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden, 1962

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have to say one of my favorite things last weekend at the Connichi was the collaboration between the convention and the Museum Wiesbaden - I love museums and I am just thankful for the opportunity to take photos of one of my current favorite characters in such an atmosphere.

Bookman Jr. collects information all over the world, mainly about the wars but sometimes it's time to stop and cherish the beauty of nature captured beautifully in the exhibitions within the museum. It wars hard to set on one photo here but I love how this one came out, I was bewitched by that display. Photo by @adragonstale Location: Museum Wiesbaden Character: (past) Bookman Jr. - D.Gray-man

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't wanna! I don't! I don't, I don't I don't!!!

A silly little exempt from a nice and spontaneous photo shoot at Museum Wiesbaden (taken at Connichi 2024).

📸 Pics and edit by

@ crymi_cosplay (on Insta) ❤️

Senshi is @ jos_bizarre_cosplay (on Insta) 👀

Marcille is made and worn by me ✌🏻

#cosplay#danmeshi#delicious in dungeon#dungeon meshi#marcille donato#senshi dungeon meshi#i am cringe but i am free

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The new tool in the art of spotting forgeries: Artificial Intelligence

Instead of obsessing over materials, the new technique takes a hard look at the picture itself – specifically, the thousands of tiny individual strokes that compose it

In late March, a judge in Wiesbaden, Germany, found herself playing the uncomfortable role of art critic. On trial before her were two men accused of forging paintings by artists including Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky, whose angular, abstract compositions can now go for eight-figure prices. The case had been in progress for three and a half years and was seen by many as a test. A successful prosecution could help end an epidemic of forgeries – so-called miracle pictures that appear from nowhere – that have been plaguing the market in avant-garde Russian art.

But as the trial reached its climax, it disintegrated into farce. One witness, arguably the world’s leading Malevich authority, argued that the paintings were unquestionably fakes. Another witness, whose credentials were equally impeccable, swore that they were authentic. In the end, the forgery indictments had to be dropped; the accused were convicted only on minor charges.

The judge was unimpressed. “Ask 10 different art historians the same question and you get 10 different answers,” she told the New York Times. Adding a touch of bleak comedy to proceedings, it emerged that the warring experts were at the wrong end of a bad divorce.

It isn’t a comforting time for art historians. Weeks earlier, in January, the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium, was forced to pull 24 works supposedly by many of the same Russian artists – Kandinsky, Malevich, Rodcheko, Filonov – after the Art Newspaper published an exposé arguing they were all forged. Just days before, there was uproar when 21 paintings shown at a Modigliani exhibition in Genoa, Italy, were confiscated and labeled as fakes. Works that had been valued at millions of dollars were abruptly deemed worthless.

The market in old masters is also jittery after an alarming series of scandals – the greatest of which was that paintings handled by the respected collector Giuliano Ruffini were suspect. A Cranach, a Parmigiano, and a Frans Hals were all found to be forged; institutions including the Louvre had been fooled. The auction house Sotheby’s was forced to refund $10m for the Hals alone. Many experts are now reluctant to offer an opinion, in case they’re sued – which, of course, only intensifies the problem.

Adding fuel to the fire is another development: Wary of being caught, more and more forgers are copying works from the early to mid-20th century. It’s much easier to acquire authentic materials, for one thing, and modern paintings have rocketed in value in recent years.

For many in the industry, it is starting to look like a crisis. Little wonder that galleries and auction houses, desperate to protect themselves, have gone CSI. X-ray fluorescence can detect paint and pigment type; infrared reflectography and Raman spectroscopy can peer into a work’s inner layers and detect whether its very component molecules are authentic. Testing the chemistry of a flake of paint less than a millimeter wide can disclose deep secrets about where and, crucially, when it was made.

“It’s an arms race,” says Jennifer Mass, an authentication expert who runs the Delaware-based firm Scientific Analysis of Fine and Decorative Art. “Them against us.”

But what if you didn’t need to go to all that trouble? What if the forger’s handwriting was staring you in the face, if only you could see it? That’s the hope of researchers at Rutgers University in New Jersey, who have pioneered a method that promises to turn art authentication on its head.

Instead of subjecting works to lengthy and hugely expensive materials analysis, hoping a forger has made a tiny slip – a stray fiber, varnish made using ingredients that wouldn’t have been available in 16th-century Venice – the new technique is so powerful that it doesn’t even need access to the original work: A digital photograph will do. Even more striking, this method is aided by artificial intelligence. A technology whose previous contributions to art history have consisted of some bizarre sub–Salvador Dalís might soon be able to make the tweed-wearing art valuers look like amateurs.

At least that’s the theory, says Ahmed Elgammal, PhD, whose team at Rutgers has developed the new process, which was made public late last year. “It is still very much under development; we are working all the time. But we think it will be a hugely valuable addition to the arsenal.”

That theory is certainly intriguing. Instead of obsessing over materials, the new technique takes a hard look at the picture itself: Specifically, the thousands of tiny individual strokes that compose it.

Every single gesture – shape, curvature, the velocity with which a brush- or pencil-stroke is applied – reveals something about the artist who made it. Together, they form a telltale fingerprint. Analyze enough works and build up a database, and the idea is that you can find every artist’s fingerprint. Add in a work you’re unsure about, and you’ll be able to tell in minutes whether it’s really a Matisse or if it was completed in a garage in Los Angeles last week. You wouldn’t even need the whole work; an image of one brushstroke could give the game away.

“Strokes capture unintentional process,” explains Elgammal. “The artist is focused on composition, physical movement, brushes – all those things. But the stroke is the telltale sign.”

The paper Elgammal and his colleagues November 13, 2017 examined 300 authentic drawings by Picasso, Matisse, Egon Schiele, and a number of other artists and broke them down into more than 80,000 strokes. Machine-learning techniques refined the data set for each artist; forgers were then commissioned to produce a batch of fakes. To put the algorithm though its paces, the forgeries were fed into the system. When analyzing individual strokes, it was over 70% accurate; when whole drawings were examined, the success rate increased to over 80% . (The researchers claim 100% accuracy “in most settings.”)

The researchers are so confident that they included images of originals and fakes alongside each other in the published paper, daring so-called experts to make up their own minds. (Reader, I scored dismally.) One of Elgammal’s colleagues, Dutch painting conservator Milko den Leeuw, compares it to the way we recognize family members: They look similar, but we’re just not sure why. “Take identical twins,” he says. “Outsiders can’t separate them, but the parents can. How does that work? It’s the same with a work of art. Why do I recognize that this is a Picasso and that isn’t?”

The idea of fingerprinting artists via their strokes actually dates back to the 1950s and a technique developed by Dutch art historian Maurits Michel van Dantzig. Van Dantzig called his approach “pictology”, arguing that because every work of art is a product of the human hand, and every hand is different, it should be possible to identify authorship using these telltale strokes.

The problem, though, was that there was too much data. Even a simple drawing contains hundreds or even thousands of strokes, all of which needed to be examined by the human eye and catalogued. Multiply that by every work, and you see how impractical it was.

“It just wasn’t possible to test it,” says den Leeuw, who first became aware of pictology as a student. “I saw many attempts, but mostly it ended in ideas that would never be.”

But can AI now do what humans failed to, and give an art historian’s trained eye some sort of scientific basis? “Exactly,” says den Leeuw. “Very often it’s a gut feeling. We’re trying to unpick the mystery.”

Though Mass says she’s unlikely to throw out her fluorescence gun just yet, she admits to being impressed. “A lot of people in the field are excited by AI It’s not a magic bullet, but it’ll be another tool. And it’s really valuable when you’re dealing with a sophisticated forger who’s got everything else right – paint, paper, filler, all the materials.”

There are issues. So far, the system has been tested mainly on drawings from a handful of artists and a brief time period. Paintings, which generally contain thousands more strokes, are a tougher challenge; older paintings, which might contain numerous layers of restoration or overpainting, are tougher still. “It’s challenging, but it doesn’t mean we can’t do it,” Elgammal says. “I’m confident.”

What about style, though, particularly where an artist changes over time? Think of Picasso’s wildly varying periods – blue, African, cubist, classical – or how in the 1920s Malevich abandoned the elemental abstraction of his black squares for figurative portraits that could almost have been painted by Cézanne (pressure from Stalin was partly responsible).

Another expert, Charles R Johnson, who teaches computational art history at Cornell, is less persuaded – not so much by the AI as by the assumptions that lie behind it. “A big problem is that strokes are rarely individualized,” he says. “Overlap is difficult to unravel. Plus, one must understand the artist’s style changes over their career in order to make a judgment.”

In addition, Johnson argues, many artist’s brushwork is essentially invisible, making it impossible to unpick; it might be better to focus computer analysis on assessing canvases or paper, which can be more rigorously verified. “I remain quite skeptical,” he says.

Elgammal and den Leeuw concede there’s a way to go. Currently they’re working on impressionist paintings – infinitely more complex than Schiele and Picasso line drawings – and hope to publish the results next year. Even with the drawings, the machine can’t yet be left to learn on its own; often the algorithms require human tweaking to make sure the right features are being examined. Artists whose output isn’t large enough to create a reliable data set are also a challenge.

Asking Elgammal if he’s worried about being sued. He laughs, slightly nervously. “That’s something I think about.”

It’s a reasonable question, particularly pressing given the number of fakes that are circulating: What if your database accidentally becomes contaminated? Many people argue that the art market is hopelessly corrupt – so much so that some economists doubt whether calling it a “market” is even fair. Could the algorithm become skewed and go rogue?

“It’s like any system,” Mass agrees. “Garbage in, garbage out.”

Does she think that’s a possibility? How many fakes are out there? “Put it this way,” Mass says, “when I go into auction houses – maybe not the big ones, but smaller, local ones – I think ‘buyer beware.’ It might be between 50 and 70% .”

Rival solutions are coming down the road. Some have proposed using blockchain technology to guarantee provenance – the history of who has owned a work. Others have called for much greater transparency. Everyone agrees that the system is broken; some kind of fix is urgent.

Of course, there are big philosophical questions here. When someone goes to the effort of finding exactly the right 17th-century canvas, dons an antique smock, and paints a near-flawless Franz Hals, it should perhaps make us reconsider what we mean by the words “real” or “fake”, let alone the title of “artist”. Yet the irony is inescapable. It is hard to think of something more human than art, the definition of our self-expression as a species. But when it comes down to it, humans aren’t actually that good at separating forged and authentic in a painting that has all the hallmarks of, say, a Caravaggio but is merely a stunt double. Relying on our eyes, we simply can’t tell one twin from the other. We might even ask: Why do we care?

Forget cars that pilot themselves or Alexa teaching herself to sound less like the robot she is – AI seems to understand the secrets of artistic genius better than we do ourselves.

The irony is that, while machines might not yet might be able to make good art, they are getting eerily good at appreciating it. “Yes, it’s true,” he says thoughtfully. “When it comes to very complex combinations of things, humans are really not so good.” He laughs. “We make too many mistakes.”

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untitled drawings made by EVA HESSE during the early 1960s from the 2019 exhibition Forms Larger and Bolder: EVA HESSE DRAWINGS at Museum Wiesbaden

[courtesy of the Estate of Eva Hesse, Galerie Hauser & Wirth]

Note on context, from the exhibition preview:

Unlike her sculptural works, produced only in the last five years of her brief life, or her paintings, which belong to her early works, Eva Hesse's drawings possess a unique continuity we can trace throughout her entire oeuvre. The exhibition begins with early studies from the mid-1950s, moving through the painterly watercolors, tempera and ink drawings, and on to the draft sketches and construction “blueprints” for the sculptures of the late 1960s to form a comprehensive view of Hesse’s mere 15 years of artistic production. This broad view is complemented by the closer examination of individual works executed with fascinating delicacy. These works, in particular, embody a vivacity whose subtlety and refined aesthetic of balanced color seem to radiate energy and lightness.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

COLLAGE ON VIEW

Kaleidoskop

at the Frauen Museum in Wiesbaden, Germany 5 March-7 May 2023. "Kaleidoskop" is an international exhibition of contemporary collage with twenty invited artists, and an exhibition of Assemblages, from the "Art in a Box" call to artists made on Instagram in September 2022. "Kaleidoskop" is a dynamic collage, an expression that is born by bringing together a number of artists and resources in movement, that finally merge into images that surprise, because the artworks are as different as their creators. MORE

*****************************

Kolaj Magazine, a full color, print magazine, exists to show how the world of collage is rich, layered, and thick with complexity. By remixing history and culture, collage artists forge new thinking. To understand collage is to reshape one's thinking of art history and redefine the canon of visual culture that informs the present.

SUBSCRIBE | CURRENT ISSUE | GET A COPY

SIGN UP TO GET EMAILS

#collage#collage art#collage artist#art#artist#art history#art project#art show#vintage art#art books#art education#book art#artistic#contemporary art#artwork#modern art#fine art#digital art#public art#contemporary artist

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ritschl, Otto (Erfurt 1885 - 1976 Wiesbaden), Two Figures, 1927, oil on canvas, 91 cm by 65,5 cm. Via Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal.

Ritschl's early work is characterized by an expressionistic and still figurative approach. In 1925 he took part in the exhibition “Neue Sachlichkeit” at the Kunsthalle Mannheim with “The Drunken Man”. The exhibition can be seen as a turning point in his work; after visiting the exhibition it was clear to him: “to give up copying in any way”. Due to the influence of a stay in Paris, he broke away from realistic painting and turned to non-representational art under the influence of Cubism and Surrealism.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tipp: moving boxes - Kunstverein Wiesbaden

29. November 2024 – 23. Februar 2025 | Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden Ein Projekt von Heiner Blum und Jakob Sturm mit Gästenin Zusammenarbeit mit Lotte Dinse und Selina Hammerin Koproduktion mit Diamant / Museum Of Urban Culture und Orte möglichen Wohnen Die historische Villa, in der sich der Nassauische Kunstverein Wiesbaden befindet, wurde Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts als Mietshaus mit…

#Ausstellung#Charlotte Posenenske#Charlotte Posenske#Donald Judd#Exhibition#Heiner Blum#Imi Knoebel#Jakob Sturm#Kunstausstellung#Kunstverein Wiesbaden#Lotte Dinse#Manuela Mordhorst#moving boxes#Selina Hammer

0 notes

Text

„Ohne Rose tun wir‘s nicht“ Neulich im Sommer im Museum Wiesbaden.

0 notes

Text

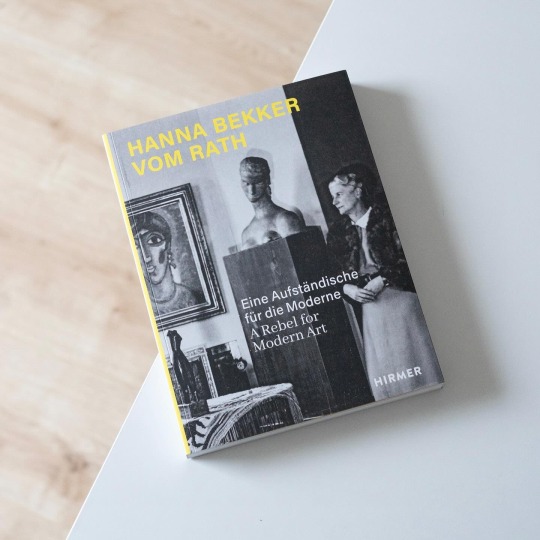

At a time when women were largely confined to household and parenting Hanna Bekker vom Rath (1893-1983) pursued a different path: born into a wealthy, liberal family then Hanna vom Rath neither wanted to fulfill representative functions nor did she want to live the life a traditional housewife. Instead she wanted to become an artists and took painting and drawing lessons with Ottilie Roederstein, Ida Kerkovius and Adolf Hoelzl. But although her dream of a full-time artistic career never materialized she devoted her life to art: at the „Blue House“ in Wiesbaden, the family seat of her, Paul Bekker and their children, she displayed her growing collection of works by Heckel, Kirchner, Lehmbruck or Schmidt-Rotfluff. Together with Alexej von Jawlensky, whom she had befriended around 1926, Schmidt-Rotluff became Bekker's house artist and spent many summer weeks in the „Blue House“, especially after the Nazis seized power in 1933. During these years and despite the danger of being denunciated Bekker began to support „her“ artists by organizing secret exhibitions in her house as well as her apartment in Berlin: her goal was to secure the artists’ economic base by selling their „degenerate“ artworks to progressive collectors. Among the exhibited artists verifiably were Erich Heckel, Willy Baumeister, Ida Kerkovius, Ernst Wilhelm Nay and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff while visitors included sculptor Georg Kolbe, the founding director of the Brücke Museum Leopold Reidemeister as well as Ernst Gosebruch, the forcibly removed former director of the Folkwang Museum. These exhibitions, hosted under precarious conditions, nevertheless lay the foundation for Bekker’s postwar Kunstkabinett in Frankfurt/Main where she showed prewar as well as contemporary art.

Right now and up until 16 June the Brücke Museum in Berlin with „Hanna Bekker vom Rath. A Rebel for Modern Art“ devotes a comprehensive exhibition to her pioneering work and the artists she collected and represented. Alongside it the Hirmer Verlag published the present catalogue which provides a concise overview of Bekker’s many activities: besides featuring a beautiful spreads of her legendary residence and her artworks the included essays elaborate her biography and artist network, her clandestine exhibitions during wartime as well as her women artists network.

This independent and exciting life of hers is very insightfully elaborated and beautifully illustrated in the catalogue that accordingly is highly recommended!

#hanna bekker vom rath#hirmer verlag#art history#art book#exhibition catalogue#gallerist#expressionism#modern art#book

10 notes

·

View notes