#minsk ghetto

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

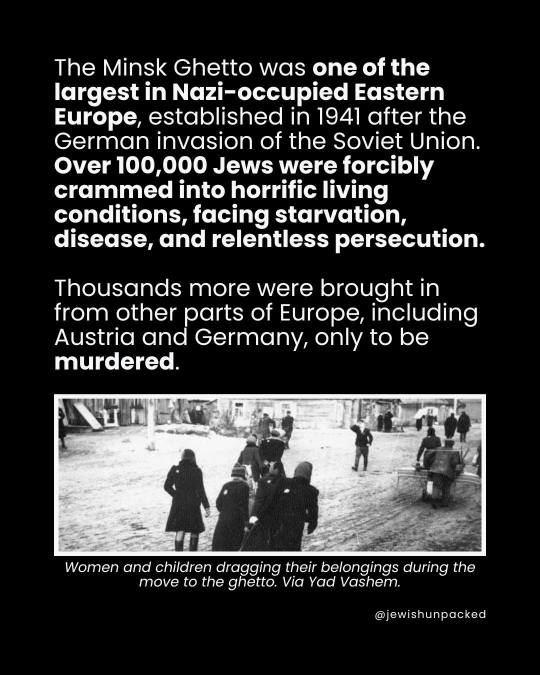

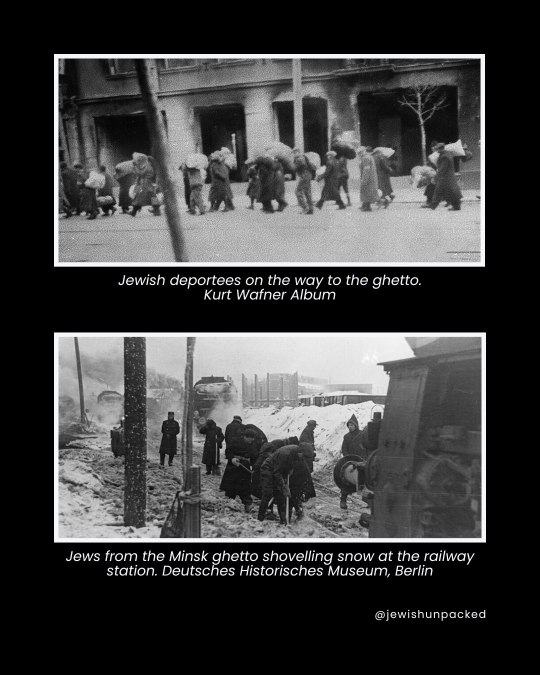

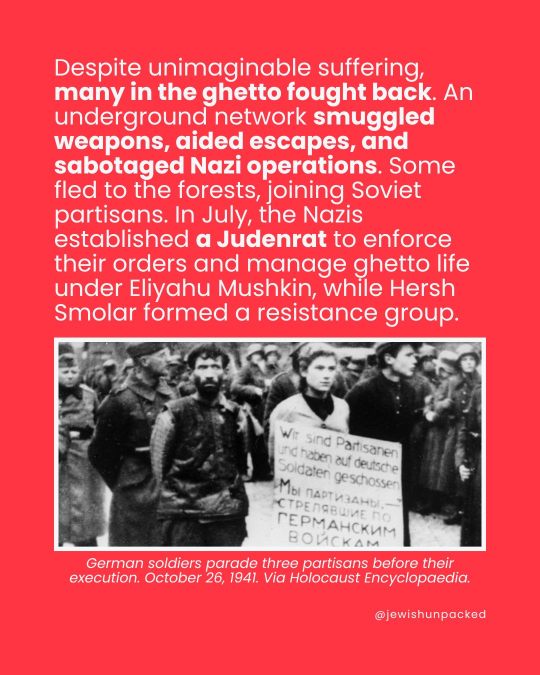

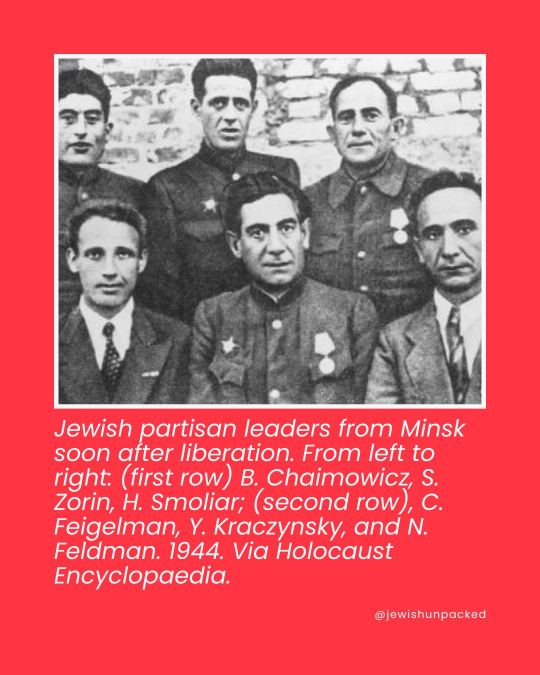

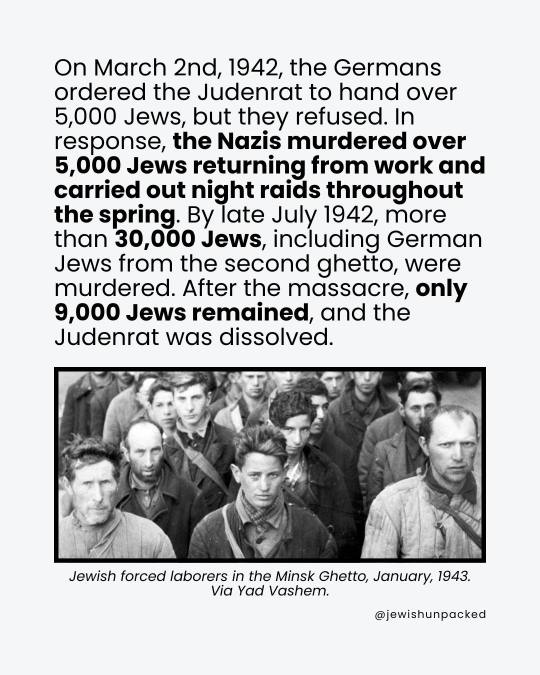

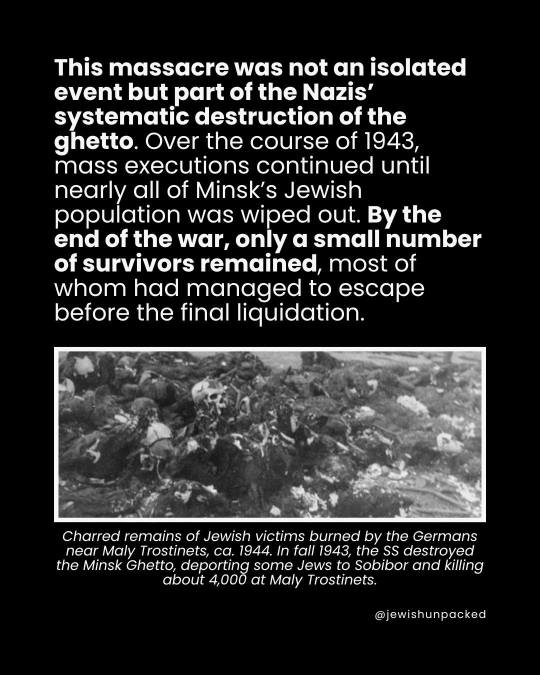

OTD in 1943, the Nazis massacred 5,000 Jews in the Minsk Ghetto, one of the largest in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe.

Established in 1941, the ghetto held over 100,000 Jews, many of whom suffered starvation, disease, and brutal persecution. Despite acts of resistance, the Nazis carried out mass executions until nearly the entire Jewish population of Minsk was wiped out.

Today, we remember the victims and honor their memory.

101 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! In one of your posts you mentioned Anna Louise Strong's The Soviets Expected It, where she describes that Belarusians did not turn on their Jewish neighbors when Nazis invaded the USSR. Then you said that in 30 years the USSR managed to extirpate antisemitism from the general population. Was this something Strong said in the book explicitly? I'm interested in the topic and I was wondering whether Strong's book is worth reading for her analysis on how the USSR managed to eliminate antisemitism or whether she only mentions it briefly. Thank you!

Hello! After searching for it, @komsomolka helped me find this quote. It wasn't by ALS as I remembered, but rather by Vic L. Allen in his book The Russians are Coming: The Politics of Anti-Sovietism:

It was German practice as they entered Soviet territories to encourage the local populace to engage in pogroms against the Jews as a first stage in their genocidal policy. They had some success in those areas which had become part of the Soviet Union since 1939 but in the Soviet Union proper there was no evidence of spontaneous anti-Semitism. A Jewish historian commentated that "In Byelorussia, a conspicuous difference is evidenced between the old Soviet part of the region and the area which had previously belonged to Poland and was under Soviet rule from September 1939 to June 1941. Nazi and anti-Jewish propaganda drew a weak response in the former Soviet Byelorussia: we encounter complaints in Nazi documents that, "it is extremely hard to incite the local populace to pogroms because of the backwardness of the Byelorussian peasants with regard to racial consciousness" Another view of the cause of the racial attitudes in Byelorussia was given in a secret memorandum by a collaborator to the chief of the German army in August 1942. He wrote: "There is no Jewish problem for the Byelorussian people. For them, this is purely a German matter. This derives from Soviet education which has negated racial difference... The Byelorussians sympathize with, and have compassion for the Jews, and regard the Germans as barbarians and the hangman of the Jew, whom they consider human beings equal to themselves...".

The Russians are Coming: The Politics of Anti-Sovietism (pages 144-145), Vic L. Allen, via ebook-hunter.org

This book goes into some detail regarding jews in the USSR, the sixth chapter, in part II, is dedicated to this.

Anna Louise Strong also wrote about antisemitism in the USSR, although just like almost any other subject in her books, she tackles it through a collection of anecdotes and observations, though I still think she paints a clear picture that's corroborated by Allen's book, for example:

Acts of race prejudice are severely dealt with in the Soviet Union. Ordinary drunken brawls between Russians may be lightly handled as misdemeanors, but let a brawl occur between a Russian and a Jew in which national names are used in a way insulting to national dignity, and this becomes a serious political offense. Usually, the remnants of national antagonisms require no such drastic methods; they yield to education. But the American workers who helped build the Stalingrad Tractor Plant will long remember the clash that Lewis and Brown had with the Soviet courts after their fight with the Negro Robinson, in the course of which they called him “damn low-down nigger.” The two white men were “deported” to America, disgraced in Soviet eyes by a serious political offense; the Negro remained and is now a member of the Moscow City government. The devotion of long-suppressed peoples and their willingness to die for their new equality is the prize that the Soviet national policy won for the present war. The Jews in the Soviet Union especially know that they have something to fight for as they see beyond the border Hitler’s destruction of the Jews and the anti-Semitism that spreads from country to country. When I last visited Minsk, which under the tsar was a ghetto city, and under the Soviets was the capital of the Byelo-Russian republic, with more than one-third of the population Jews, I asked the young Intourist guide, “Don’t you yourself, as a Jewish woman, ever encounter racial feeling in your daily contacts?” “I haven’t for years,” she answered. I wonder what she encountered when the Nazis entered Minsk.

The Soviets Expected it, Anna Louise Strong, via redstarpublishers.org

I recall across the years one of the Birobidjan leaders who went on the same train with me to Moscow. His energy and teasing laughter made him the life of the train. He frequently sat in the compartment with two Red Army commanders, joshing them about the quantities of edibles they consumed and declaring that he would have them arrested for upsetting the food balance of the country. Later he told me that these two commanders gave him more delight than anything on the train. He told me of his own early life in the Ukraine amid constant pogroms. He repeated the discussions with the two Red Army commanders. They had been asking whether the Red Army gave adequate help to the Jewish settlers. “We hear they made you a road. Was it a good one? Do they help you properly with your harvest? How are relations developing between the Red Army and the new immigrants?” “Can you imagine what those questions mean to me, a Jew of Birobidjan?” he asked. “No, you can never imagine it, for you cannot live my life. Those Red commanders are the sons of the Cossacks who used to commit the pogroms! And now it is all gone like a dream! They want to know if they help us adequately! They are too young even to remember pogroms. But I remember; I am old enough.”

The Soviets Expected it, Anna Louise Strong, via redstarpublishers.org

How much discrimination there was against Jews in educational institutions is hard to tell. It was never general but certainly there was some. It was evasive and struggles always developed against it. My best friend felt for a time undermined in her university job because she refused to yield to the anti-Semitism which seemed to be promoted by the Party secretary at the university. One day she came home exultant. “Now I know the Party doesn’t stand for anti-Semitism,” she said. “They removed A… He was in charge of universities here for the Central Committee and was behind much of this anti-Semitism.” This anecdote shows the confusion that existed. Anti-Semitism was sometimes promoted by people high in office, but always with evasion. The basic law that made it illegal was never attacked, challenged or revoked. The disease of anti-cosmopolitanism passed, and anti-Semitism with it. Not by law or decree, but because of three facts. In 1950, the USSR reached the highest production in its history, with comparative abundance of goods. The USSR also attained the A-Bomb — the threat of America’s monopoly was gone. And, also in 1950, the Chinese People’s Republic was established in Peking, and at once made alliance with the USSR. The sick, excessive patriotism bred by the cold war could not survive close contact with an eastern, equal ally, whose inventions began a thousand years before Russia’s, and whose present intelligence and achievements even the most successful Russians had to acclaim.

The Stalin Era, Anna Louise Strong, via redstarpublishers.org

In simple oratory the worker and peasant deputies to the new National Assemblies told of their tortured past and of their happiness when the Red Army arrived. Women told how in former days young boys had been held on anthills by landlords’ agents in order to break the spirit of rebellion, how a mother picking up fuel in the woods to heat water for a newborn baby had been caught by the lord’s forester, beaten, and afterward turned over to the attack of fierce dogs. It was a gruesome account of medieval conditions. Deputies from Grodno told how the Jewish and ByeloRussian workers of the city had organized their own militia before the Red Army came and had rushed out and helped build a bridge for it into the city under the fire of Polish officers. “As soon as the Red Army came,” said a carpenter from Bialystok, “we asked them to set up Soviet power for us. But they told us: ‘Soviet power is the power of the people. Organize it yourselves, for now you are the bosses of your lives’.” A simple peasant women deputy said: “Let the priests pray to God for Paradise, but for us the daylight is already come; the bright sun is come from the East.” Letters telling a similar story reached America from Jews in the occupied regions. They especially commented on their rescue from death, for they had been threatened both by German bombing and by anti-Semitic bands of Poles. “If the Red Army had been a day later, not a Jew in our town would have been left alive,” wrote a man from Grodno. Other letters marvelled at the new equality. “To the Bolsheviks everyone is equal; there is no difference between Gentile and Jew.” There was a grimmer side to the story. Poles in fairly large numbers were deported to various places in the Soviet Union. Letters received by their relatives in Europe and America showed that they were scattered all over the U.S.S.R.; the sending of the letters also indicated that they were not under surveillance but merely deported away from the border district. The Soviet authorities claimed that former Polish officers and military colonists had done considerable sabotage and kept the people disturbed by rumors of imminent invasions by Rumanian and British troops. After the conclusion of the Soviet-Polish alliance against Hitlerite Germany, these Poles rapidly joined the Polish Legion under the Red Army High Command. Most of them then stated that they fully understood the necessity of the Red Army’s march into Poland.

The Stalin Era, Anna Louise Strong, via redstarpublishers.org

The new people’s government of Lithuania had appointed as governor of Vilna an able Communist, Didzhulius, not long since out of prison. Prison had injured his health and he had gone to a rest home, but had not been able to take the time to get well. People were needed for Vilna, and so he came. When I saw him he had held office only three days. “We must end this evil process whereby first Poles suppress Lithuanians and then Lithuanians suppress Poles,” he told me. “Under Smetona only thirty thousand people here had the vote. We have given it at once to everybody. “There were one hundred thousand unemployed here. We at once began road-building and other public construction; we are setting up public relief. The old Polish pensioners had buildings and funds which Smetona did not let them touch. We have made their possessions available to them for the relief of those most in need. We have done more to relieve the misery of starving people in three days than Smetona did in six months.” One of the first decrees passed was that government officials must hear citizens’ requests in whatever language the citizens choose. For this purpose officials are sought who can speak as many languages as possible. Schools also are to be in all the local languages. “Under the Poles education was only in Polish; under Smetona it was only in Lithuanian,” said Didzhulius. “Now we shall have to have schools in our languages since there are four chief languages in this district: Polish, Jewish, Lithuanian and Byelorussian.”

The New Lithuania, Anna Louise Strong, via redstarpublishers.org

Overall, I think the picture ALS paints is a nuanced one. The USSR made a lot of progress removing racism and nationalism from its population, although it was not perfect and some decisions like the deportations were negative for the moved population (though not as genocidal or malevolent as most like to paint it), they did an outstanding job at the task of removing prejudice from their society at a time where that was not happening anywhere else, and this was reflected both in laws and in action. We have a lot to learn from their policies, both their many (even to this day) unparalleled achievements as well as from their flaws.

To these third party accounts I'll also add Stalin's own words:

In answer to your inquiry: National and racial chauvinism is a vestige of the misanthropic customs characteristic of the period of cannibalism. Anti-semitism, as an extreme form of racial chauvinism, is the most dangerous vestige of cannibalism. Anti-semitism is of advantage to the exploiters as a lightning conductor that deflects the blows aimed by the working people at capitalism. Anti-semitism is dangerous for the working people as being a false path that leads them off the right road and lands them in the jungle. Hence Communists, as consistent internationalists, cannot but be irreconcilable, sworn enemies of anti-semitism. In the U.S.S.R. anti-semitism is punishable with the utmost severity of the law as a phenomenon deeply hostile to the Soviet system. Under U.S.S.R. law active anti-semites are liable to the death penalty. J. Stalin

Anti-Semitism: Reply to an Inquiry of the Jewish News Agency in the United States . J. V. Stalin, 1931. First published in the newspaper Pravda, No. 329, November 30, 1936

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Israeli preparations for the "final solution" of the Palestinian issue. History repeats itself⬇️

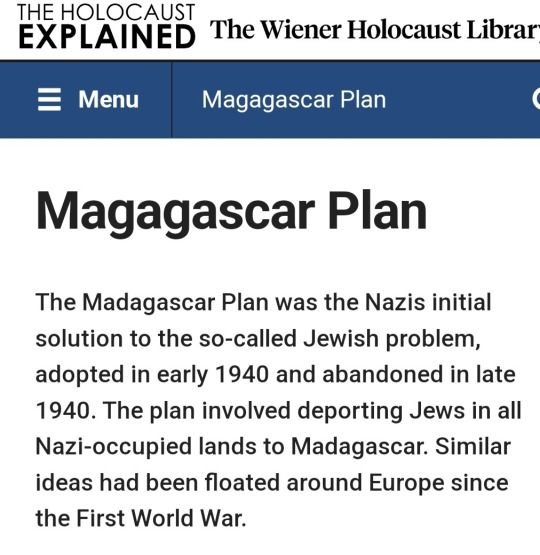

In the autumn of 1941, approximately 338,000 Jews remained in Greater Germany. Until this point, Hitler had been reluctant to deport Jews in the German Reich until the war was over because of a fear of resistance and retaliation from the German population. But, in the autumn of 1941, key Nazi figures contributed to mounting pressure on Hitler to deport the German Jews. This pressure culminated in Hitler ordering the deportation of all Jews still in the Greater German Reich and Protectorate between 15-17 September 1941.

Following the order, Himmler, Heydrich and Eichmann attempted to find space for the Jews from the Greater German Reich in the already severely overcrowded ghettos in eastern Europe. Officials in the Łódź, Litzmannstadt, Minsk and Riga ghettos were all informed that they would need to absorb the population of Jews from the Greater German Reich, irrespective of overcrowding.

The Minsk Ghetto was full, so in order to make room for the Reich Jews, the local SD , German Army and local collaborators gathered approximately 25,000 of the local ghetto inhabitants, drove them to a local ravine, and murdered them. German Jews soon filled their places in the ghetto. Similar murders took place in Riga.

In Łódź Ghetto, no local Jews were removed prior to the arrival of 20,000 Jews from the Greater German Reich. Instead, following the success of the experiments in using gas vans for mass murder at Chełmno extermination camp in December 1941, deportations from the ghetto to Chełmno began on 16 January 1942, four days before the Wannsee Conference.

As with most of the Nazis’ murderous actions, the deportation of German Jews was improvised and haphazard . The increased numbers of Jews arriving in the ghettos of eastern Europe led to severe overcrowding, unsustainable food shortages and poor sanitation. This, in combination with the slow progress in the German invasion of the Soviet Union, convinced the Nazis that a ‘solution’ to the ‘Jewish problem’ needed to be organised sooner than had been originally envisaged. The deportations also partly led to the gas experiments at Chełmno, and heightened the Nazis’ sense of urgency to coordinate the policy towards Jews at the Wannsee Conference.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Jewish Partisans Challenged Nazi Forces in Soviet Byelorussia.

The Bielski brothers, natives of Stankevichi in Western Byelorussia, emerged as icons of resistance against Nazi persecution. Rather than succumbing to the horrors, they initiated a fierce armed resistance, safeguarding numerous Jews and retaliating against their oppressors. As Aron Bielski articulated, "We weren't afraid of the Nazis. We were on home soil."

The brothers personally endured the German's savagery, witnessing several family members fall victim. Choosing defiance over submission, they sought refuge in the woods, rapidly forming a significant partisan detachment predominantly consisting of Jews. Their mission wasn't just survival; they proactively rescued people from nearby ghettos. Tuvia Bielski, the eldest, asserted, "We may be killed while we try to live. But we will do all we can to save more lives."

Their base, named "Jerusalem in the Woods," was established deep within the Naliboki Forest. This well-organised hideout boasted essential facilities, including a command HQ, workshops, a school, and even a synagogue. As Aron Bielski reminisced, the forest symbolised their "freedom and salvation."

Throughout the war, the Bielski partisans exhibited immense courage, confronting the Nazis and collaborating with Soviet partisan detachments. Their contributions led to the rescue of an estimated 1,230 Jews.

Among those who found refuge with the Bielskis were Raia (Rae) and Zeidel Kushner, the grandmother and grandfather of businessman Jared Corey Kushner, Donald Trump's son-in-law.

After the war, the brothers moved to Israel and subsequently to the U.S., where they pursued various careers. Their exceptional tale gained widespread attention with the 2008 film 'Defiance', featuring Daniel Craig as Tuvia.

Discover the full account here: https://www.rbth.com/history/336751-how-jewish-partisans-struck-terror]

#FromTheOtherSide 🇧🇾 #Minsk #Belarus

0 notes

Photo

Uncredited Photographer Three Jewish Woman Anti-fascist Fighters From the Minsk Ghetto and the Partisan Ranks Outside the City After the nazis Destroyed the Ghetto and Murdered the Remaining Jewish Population: Zelda Nisanilevich Treger, Rozka Korczak-Marla and Vitka Kempner-Kovner Undated (Probably taken after the Red Army liberated Minsk, July, 1944)

100 notes

·

View notes

Photo

JOURNEY WITH NO RETURN Today I visited an exhibition that focuses on the deportation of Jews from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which took place as part of the “final solution to the Jewish question”. In 1939–1945, almost 81,000 of these Jews were deported to the ghettoes in Łódź, Minsk and Terezín and to the concentration, labour and extermination camps in the German-occupied territories of Eastern Europe. More than 78,000 of them fell victim to the Shoah. In the Jewish Quarters there was a cemetery and one grave had this beautiful red rose placed on it. There was something so beautiful and sad about it at the same time. I was full of emotions. If you look at the second and third picture you will notice handwritten notes left by people for their loved ones. I wonder why do we humans treat each others so badly?! I hope all these people are in peace now and in their happy place. #ayushkejriwal #pragueworld #journeywithnoreturn #jewishquarterprague (at Prague Jewish Quarter) https://www.instagram.com/p/ClEN_W-s_rg/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

so after reading the minsk ghetto: jewish resistance and soviet internationalism im very interested in reading hersch smolar’s memoir but my uni library has that as “read on site” only. which considering the condition of some of the books ive checked out it must be pretty damn delicate

1 note

·

View note

Text

GESCHICHTE

Der Name Berlin leitet sich vermutlich von dem slawischen Begriff br’lo bzw. berlo mit den Bedeutungen ‚Sumpf, Morast, feuchte Stelle‘oder ‚trockene Stelle in einem Feuchtgebiet‘ sowie dem in slawischen Ortsnamen häufigen Suffix -in ab. Dafür spricht vor allem, dass der Name in Urkunden immer wieder mit Artikel auftaucht („der Berlin“).

Der Stadtname ist weder auf den angeblichen Gründer der Stadt, Albrecht den Bären, noch auf das Berliner Wappentier zurückzuführen. Hierbei handelt es sich um ein redendes Wappen, mit dem versucht wird, den Stadtnamen in deutscher Interpretation bildlich darzustellen. Das Wappentier leitet sich demnach vom Stadtnamen ab, nicht umgekehrt

Mittelalter

Die auf der Spreeinsel gelegene Stadt Cölln wurde 1237 erstmals urkundlich erwähnt. 1244 folgte dann die Erwähnung (Alt-)Berlins, das am nordöstlichen Ufer der Spree liegt. Neuere archäologische Funde belegen, dass es bereits in der zweiten Hälfte des 12. Jahrhunderts vorstädtische Siedlungen beiderseits der Spree gegeben hat. 1280 fand der erste nachweisbare märkische Landtag in Berlin statt. Dies deutet auf eine frühe Spitzenstellung, wie sie auch aus dem Landbuch Karls IV. (1375) erkennbar wird, als Berlin mit Stendal, Prenzlau und Frankfurt/Oder als die Städte mit dem höchsten Steueraufkommen nachgewiesen werden. Die beiden Städte bekamen 1307 ein gemeinsames Rathaus.

Berlin teilte das Schicksal Brandenburgs unter den Askaniern (1157–1320), Wittelsbachern (1323–1373) und Luxemburgern (1373–1415). Im Jahr 1257 zählte der Markgraf von Brandenburg zum ersten Mal zum einzig zur Königswahl berechtigten Wahlkollegium. Die genauen Regeln wurden 1356 mit der Goldenen Bulle festgelegt; seitdem galt Brandenburg als Kurfürstentum. Nachdem der deutsche König Sigismund von Luxemburg 1415 Friedrich I. von Hohenzollern mit der Mark Brandenburg belehnt hatte, regierte diese Familie bis 1918 in Berlin als Markgrafen und Kurfürsten von Brandenburg und ab 1701 auch als Könige in bzw. von Preußen.

Im Jahr 1448 revoltierten Einwohner von Berlin im „Berliner Unwillen“ gegen den Schlossneubau des Kurfürsten Friedrich II. („Eisenzahn“). Dieser Protest war jedoch nicht von Erfolg gekrönt, und die Stadt büßte viele ihrer mittlerweile ersessenen politischen und ökonomischen Freiheiten ein. Kurfürst Johann Cicero erklärte 1486 Berlin zur Hauptresidenzstadt des brandenburgischen Kurfürstentums.

Bereits seit 1280 gab es Handelsbeziehungen zur Hanse, insbesondere zu Hamburg. Ab dem 14. Jahrhundert war Berlin Mitglied der Hanse. 1518 trat Berlin formal aus der Hanse aus bzw. wurde von ihr ausgeschlossen.

Die Reformation wurde 1539 unter Kurfürst Joachim II. in Berlin und Cölln eingeführt, ohne dass es zu großen Auseinandersetzungen kam.

Der Dreißigjährige Krieg zwischen 1618 und 1648 hatte für Berlin verheerende Folgen: Ein Drittel der Häuser wurde beschädigt, die Bevölkerungszahl halbierte sich. Friedrich Wilhelm, bekannt als der Große Kurfürst, übernahm 1640 die Regierungsgeschäfte von seinem Vater. Er begann eine Politik der Immigration und der religiösen Toleranz. Vom darauf folgenden Jahr an kam es zur Gründung der Vorstädte Friedrichswerder, Dorotheenstadt und Friedrichstadt.

Im Jahr 1671 wurde 50 jüdischen Familien aus Österreich ein Zuhause in Berlin gegeben. Mit dem Edikt von Potsdam 1685 lud Friedrich Wilhelm die französischen Hugenotten nach Brandenburg ein. Über 15.000 Franzosen kamen, von denen sich 6.000 in Berlin niederließen. Um 1700 waren 20 Prozent der Berliner Einwohner Franzosen, und ihr kultureller Einfluss war groß. Viele Einwanderer kamen außerdem aus Böhmen, Polen und Salzburg.

Preußisches Königreich

Berlin erlangte 1701 durch die Krönung Friedrichs I. zum König in Preußen die Stellung der preußischen Hauptstadt, was durch das Edikt zur Bildung der Königlichen Residenz Berlin durch Zusammenlegung der Städte Berlin, Cölln, Friedrichswerder, Dorotheenstadt und Friedrichstadt am 17. Januar 1709 amtlich wurde. Bald darauf entstanden neue Vorstädte, die Berlin vergrößerten.

Das Berliner Schloss, seit 1702 die Hauptresidenz der preußischen Könige und ab 1871 der Deutschen Kaiser.

Nach der Niederlage Preußens 1806 gegen die Armeen Napoleons verließ der König Berlin Richtung Königsberg. Behörden und wohlhabende Familien zogen aus Berlin fort. Französische Truppen besetzten die Stadt von 1806 bis 1808. Unter dem Reformer Freiherr vom und zum Stein wurde am 19. November 1808 die neue Berliner Städteordnung beschlossen und in einem Festakt am 6. Juli 1809 in der Nikolaikirche proklamiert, was zur ersten frei gewählten Stadtverordnetenversammlung führte. An die Spitze der neuen Verwaltung wurde ein Oberbürgermeister gewählt. Die Vereidigung der neuen Stadtverwaltung, Magistrat genannt, erfolgte am 8. Juli des Jahres im Berliner Rathaus.

Bei den Reformen der Schulen und wissenschaftlichen Einrichtungen spielte die von Wilhelm von Humboldt vorgeschlagene Bildung einer Berliner Universität eine bedeutende Rolle. Die neue Universität (1810) entwickelte sich rasch zum geistigen Mittelpunkt von Berlin und wurde bald weithin berühmt.

Weitere Reformen wie die Einführung einer Gewerbesteuer, das Gewerbe-Polizeigesetz (mit der Abschaffung der Zunftordnung), unter Staatskanzler Karl August von Hardenberg verabschiedet, die bürgerliche Gleichstellung der Juden und die Erneuerung des Heereswesens führten zu einem neuen Wachstumsschub in Berlin. Vor allem legten sie die Grundlage für die spätere Industrieentwicklung in der Stadt. Der König kehrte Ende 1809 nach Berlin zurück.

In den folgenden Jahrzehnten bis um 1850 siedelten sich außerhalb der Stadtmauern neue Fabriken an, in denen die Zuwanderer als Arbeiter oder Tagelöhner Beschäftigung fanden. Dadurch verdoppelte sich die Zahl der Einwohner durch Zuzug aus den östlichen Landesteilen. Bedeutende Unternehmen wie Borsig, Siemens oder die AEG entstanden und führten dazu, dass Berlin bald als Industriestadt galt. Damit einher ging auch der politische Aufstieg der Berliner Arbeiterbewegung, die sich zu einer der stärksten der Welt entwickelte.

Im Ergebnis der Märzrevolution machte der König zahlreiche Zugeständnisse. Ende 1848 wurde ein neuer Magistrat gewählt. Nach einer kurzen Pause wurde im März 1850 eine neue Stadtverfassung und Gemeindeordnung beschlossen, wonach die Presse- und Versammlungsfreiheit wieder aufgehoben, ein neues Dreiklassen-Wahlrecht eingeführt und die Befugnisse der Stadtverordneten stark eingeschränkt wurden. Die Rechte des Polizeipräsidenten Hinckeldey wurden dagegen gestärkt. In seiner Amtszeit bis 1856 sorgte er für den Aufbau der städtischen Infrastruktur (vor allem Stadtreinigung, Wasserwerke, Wasserleitungen, Errichtung von Bade- und Waschanlagen).

Im Jahr 1861 wurden Moabit und der Wedding sowie die Tempelhofer, Schöneberger, Spandauer und weitere Vorstädte eingemeindet. Den Ausbau der Stadt regelte ab 1862 der Hobrecht-Plan. Der Fluchtlinienplan orientierte sich mit großzügigen Straßenzügen und Plätzen an der Umgestaltung von Paris durch Baron Haussmann. Die Blockbebauung mit einer Traufhöhe von 22 Metern prägt viele Berliner Stadtviertel. Durch den rasanten Bevölkerungsanstieg, Bauspekulation und Armut kam es zu prekären Wohnverhältnissen in den Mietskasernen der entstehenden Arbeiterwohnquartiere mit ihren für Berlin typischen mehrfach gestaffelten, engen Hinterhöfen.

Deutsches Kaiserreich

Mit der Einigung zum kleindeutschen Nationalstaat durch den preußischen Ministerpräsidenten Otto von Bismarck, die am 18. Januar 1871 vollzogen wurde, kam Berlin auch in die Stellung der Hauptstadt des deutschen Nationalstaats, zunächst mit dessen staatsrechtlicher Bezeichnung Deutsches Reich (bis 1945).

Mit Gründung des Kaiserreichs lässt sich der Beginn der Gründerzeit, in dessen Folge Deutschland zur Weltmacht und Berlin zur Weltstadt aufstieg, für Deutschland sehr genau auf das Jahr 1871 datieren. Im mehr als vier Jahrzehnte währenden Frieden, der im August 1914 mit Beginn des Ersten Weltkriegs endete, wurde Berlin im Jahr 1877 zunächst Millionenstadt und überstieg die Zweimillionen-Einwohner-Grenze erstmals im Jahr 1905.

Nach seiner Abdankung 1918 in Spa kehrte Kaiser Wilhelm II. nicht mehr nach Berlin zurück.

Weimarer Republik und Nationalsozialismus

Nach dem Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs wurde am 9. November 1918 in Berlin die Republik ausgerufen. In den Monaten nach der Novemberrevolution kam es mehrfach zu teils blutigen Auseinandersetzungen zwischen der Regierung und ihren Freikorps sowie revolutionären Arbeitern. Anfang 1919 erschütterte der Spartakusaufstand die Stadt, zwei Monate später ein Generalstreik. 1920 kam es zum Blutbad vor dem Reichstag und später zum Kapp-Putsch.

Im gleichen Jahr folgte mit dem Groß-Berlin-Gesetz eine umfassende Eingemeindung mehrerer umliegender Städte und Landgemeinden sowie zahlreicher Gutsbezirke. Berlin hatte damit rund vier Millionen Einwohner und war in den 1920er-Jahren die größte Stadt Kontinentaleuropas und die nach London und New York drittgrößte Stadt der Welt.

Die Stadt erlebte in den 1920er Jahren eine Blütezeit der Kunst, Kultur, Wissenschaft und Technik. Diese Zeit wurde später als die „Goldenen Zwanziger“ bezeichnet. Berlin war auch aufgrund der weit ausgedehnten Stadtfläche, die größte Industriestadt Europas.

Nach der „Machtergreifung“ der Nationalsozialisten im Jahr 1933 gewann Berlin als Hauptstadt des zentralistischen Dritten Reichs an politischer Bedeutung. Adolf Hitler und Generalbauinspektor Albert Speer entwickelten architektonische Konzepte für den Umbau der Stadt zur „Welthauptstadt Germania“, die jedoch nie verwirklicht wurden.

Das NS-Regime zerstörte Berlins jüdische Gemeinde, die vor 1933 rund 160.000 Mitglieder zählte. Nach den Novemberpogromen von 1938 wurden tausende Berliner Juden ins nahe gelegene KZ Sachsenhausen deportiert. Rund 50.000 der noch in Berlin wohnhaften 66.000 Juden wurden von 1941 an in Ghettos und Arbeitslager nach Litzmannstadt, Minsk, Kaunas, Riga, Piaski oder Theresienstadt deportiert. Viele starben dort unter den widrigen Lebensbedingungen, andere wurden von dort während des Holocausts in Vernichtungslager verschleppt und ermordet. Ab 1942 fuhren Deportationszüge nach Auschwitz.

Während des Zweiten Weltkriegs wurde Berlin erstmals im Herbst 1940 von britischen Bombern angegriffen. Die Luftangriffe steigerten sich massiv ab 1943, wobei große Teile Berlins zerstört wurden. Die Schlacht um Berlin 1945 führte zu weiteren Zerstörungen. Fast die Hälfte aller Gebäude war zerstört, nur ein Viertel aller Wohnungen war unbeschädigt geblieben. Von 226 Brücken standen nur noch 98.

Geteilte Stadt

Nach der Einnahme der Stadt durch die Rote Armee und der bedingungslosen Kapitulation der Wehrmacht am 8. Mai 1945 wurde Berlin gemäß den Londoner Protokollen – der Gliederung ganz Deutschlands in Besatzungszonen entsprechend – in vier Sektoren aufgeteilt, nämlich die Sektoren der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika, des Vereinigten Königreichs Großbritannien und Nordirland, Frankreichs und der Sowjetunion: amerikanischer, britischer, französischer und sowjetischer Sektor. Weder in der Konferenz von Jalta noch im Potsdamer Abkommen war eine förmliche Teilung in Westsektoren und Ostsektor (West-Berlin und Ost-Berlin) vorgesehen. Diese Gruppierung ergab sich 1945/46 durch das Zusammengehörigkeitsgefühl der West-Alliierten einerseits und das Gefühl der Mehrzahl der Berliner andererseits, die die West-Alliierten als Befreier „von den Russen“ empfanden.

Die Sowjetische Militäradministration in Deutschland schuf schon am 19. Mai 1945 einen Magistrat für Berlin. Er bestand aus einem parteilosen Oberbürgermeister, vier Stellvertretern und 16 Stadträten. Für Groß-Berlin blieb allerdings eine Gesamtverantwortung aller vier Siegermächte bestehen. Die zunehmenden politischen Differenzen zwischen den Westalliierten und der Sowjetunion führten nach einer Währungsreform in den West-Sektoren 1948/1949 zu einer wirtschaftlichen Blockade West-Berlins, die die Westalliierten mit der „Berliner Luftbrücke“ überwanden.

Bornholmer Straße im westlichen Teil Berlins, 1989. Nach dem Fall der Mauer bereitet ein Spalier den Besuchern aus der DDR einen Empfang.

Mit der Gründung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland im Westen Deutschlands und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik (DDR) im Osten Deutschlands im Jahr 1949 verfestigte sich der Kalte Krieg auch in Berlin. Während die Bundesrepublik ihren Regierungssitz in Bonn hatte, was zunächst als Provisorium gedacht war, proklamierte die DDR Berlin als Hauptstadt. Der Ost-West-Konflikt gipfelte in der Berlin-Krise und führte zum Bau der Berliner Mauer durch die DDR am 13. August 1961.

West-Berlin war seit 1949 de facto ein Land der Bundesrepublik Deutschland – allerdings mit rechtlicher Sonderstellung – und Ost-Berlin de facto ein Teil der DDR. Berlins Osten und Westen waren ab 1961 völlig voneinander getrennt. Der Übergang war nur an bestimmten Kontrollpunkten möglich, allerdings nicht mehr für die Bewohner der DDR und Ost-Berlins und bis 1972 nur in Ausnahmefällen für Bewohner West-Berlins, jene die nicht nur im Besitz des Berliner Personalausweises waren.

Im Jahr 1971 wurde das Viermächteabkommen über Berlin unterzeichnet und trat 1972 in Kraft. Während die Sowjetunion den Viermächte-Status nur auf West-Berlin bezog, unterstrichen die Westmächte 1975 in einer Note an die Vereinten Nationen ihre Auffassung vom Viermächte-Status über Gesamt-Berlin. Die Problematik des umstrittenen Status Berlins wird auch als Berlin-Frage bezeichnet.

Wiedervereinte Stadt

In der DDR kam es 1989 zur politischen Wende, die Mauer wurde am 9. November geöffnet. Am 3. Oktober 1990 wurden die beiden deutschen Staaten als Bundesrepublik Deutschland wiedervereinigt und Berlin per Einigungsvertrag deutsche Hauptstadt.

Am 20. Juni 1991 beschloss der Bundestag mit dem Hauptstadtbeschluss nach kontroverser öffentlicher Diskussion, dass die Stadt Sitz der deutschen Bundesregierung und des Bundestages sein solle. 1994 wurde das Schloss Bellevue auf Initiative Richard von Weizsäckers zum ersten Amtssitz des Bundespräsidenten. In der Folgezeit wurde das Bundespräsidialamt in unmittelbarer Nähe errichtet.

Im Jahr 1999 nahmen Regierung und Parlament ihre Arbeit in Berlin auf. 2001 wurde das neue Bundeskanzleramt eingeweiht und von Bundeskanzler Gerhard Schröder bezogen. Die überwiegende Zahl der Auslandsvertretungen in Deutschland verlegten in den folgenden Jahren ihren Sitz nach Berlin.

Zum 1. Januar 2001 wurde die Zahl der Berlin untergliedernden Bezirke durch deren Neugliederung von 23 auf 12 reduziert, um eine effizientere Verwaltung und Planung zu ermöglichen.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holocaust là gì

Holocaust là một trong những hành động diệt chủng khét tiếng nhất trong lịch sử hiện đại. Nhiều hành động tàn bạo của Đức Quốc xã trước và trong Thế chiến thứ hai đã hủy diệt hàng triệu sinh mạng và thay đổi vĩnh viễn bộ mặt của châu Âu.

Holocaust : Từ tiếng Hy Lạp holokauston , có nghĩa là hy sinh bằng lửa. Nó đề cập đến cuộc đàn áp và tàn sát có kế hoạch của Đức Quốc xã đối với người Do Thái và những người khác được coi là thấp kém hơn so với người Đức “chân chính”.

Bạn đang xem: Holocaust là gì

Shoah : Một từ tiếng Do Thái có nghĩa là tàn phá, đổ nát hoặc lãng phí, cũng được sử dụng để chỉ Holocaust.Nazi : từ viết tắt của Đức là viết tắt của Nationalsozialistishe Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (Đảng Công nhân Đức Quốc gia xã hội chủ nghĩa).Giải pháp cuối cùng : Thuật ngữ Đức quốc xã ám chỉ kế hoạch tiêu diệt người Do Thái của họ.Kristallnacht : Nghĩa đen là “Đêm pha lê” hay Đêm thủy tinh vỡ, đề cập đến đêm 9-10 tháng 11 năm 1938 khi hàng nghìn giáo đường Do Thái và các ngôi nhà và cơ sở kinh doanh thuộc sở hữu của người Do Thái ở Áo và Đức bị tấn công.Trại tập trung : Mặc dù chúng ta sử dụng thuật ngữ chung chung là “trại tập trung”, nhưng thực tế có một số loại trại khác nhau với các mục đích khác nhau. Chúng bao gồm các trại tiêu diệt, trại lao động, trại tù binh chiến tranh và trại trung chuyển.

Adolf Hitler, thủ tướng Đức, được những người ủng hộ chào đón tại Nuremberg vào năm 1933. Hulton Archive / Stringer / Getty Images

Holocaust bắt đầu vào năm 1933 khi Adolf Hitler lên nắm quyền ở Đức và kết thúc vào năm 1945 khi Đức Quốc xã bị quân Đồng minh đánh bại. Thuật ngữ Holocaust có nguồn gốc từ tiếng Hy Lạp holokauston , có nghĩa là hy sinh bằng lửa. Nó đề cập đến cuộc đàn áp và tàn sát có kế hoạch của Đức Quốc xã đối với người Do Thái và những người khác được coi là kém hơn so với người Đức “thực sự”. Từ Shoah trong tiếng Do Thái – có nghĩa là tàn phá, đổ nát hoặc lãng phí – cũng đề cập đến tội ác diệt chủng này.

Ngoài người Do Thái, Đức quốc xã còn nhắm vào người Roma, người đồng tính luyến ái, Nhân chứng Giê-hô-va và người khuyết tật để bắt bớ. Những người chống lại Đức Quốc xã bị đưa đến các trại lao động khổ sai hoặc bị sát hại.

Từ Nazi là từ viết tắt trong tiếng Đức của Nationalsozialistishe Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (Đảng Công nhân Đức Quốc gia xã hội chủ nghĩa). Đức Quốc xã đôi khi sử dụng thuật ngữ “Giải pháp cuối cùng” để chỉ kế hoạch tiêu diệt người Do Thái của họ, mặc dù nguồn gốc của điều này không rõ ràng, theo các nhà sử học.

Người chết

Theo Bảo tàng Tưởng niệm Holocaust của Hoa Kỳ, hơn 17 triệu người đã thiệt mạng trong Holocaust, nhưng không có tài liệu nào ghi lại tổng số. Sáu triệu người trong số này là người Do Thái – khoảng 2/3 tổng số người Do Thái sống ở châu Âu. Ước tính có khoảng 1,5 triệu trẻ em Do Thái và hàng nghìn trẻ em Romani, Đức và Ba Lan đã chết trong Holocaust.

Số liệu thống kê sau đây là từ Bảo tàng Holocaust Quốc gia Hoa Kỳ. Khi nhiều thông tin và hồ sơ được phát hiện, có khả năng những con số này sẽ thay đổi. Tất cả các con số là gần đúng.

Xem thêm: Squeeze Là Gì – Squeeze Trong Tiếng Tiếng Việt

6 triệu người Do Thái5,7 triệu thường dân Liên Xô (thêm 1,3 thường dân Do Thái Liên Xô được tính vào con số 6 triệu người Do Thái)3 triệu tù nhân chiến tranh của Liên Xô (bao gồm khoảng 50.000 lính Do Thái)1,9 triệu thường dân Ba Lan (không phải Do Thái)312.000 thường dân SerbLên đến 250.000 người khuyết tậtLên đến 250.000 Roma1.900 nhân chứng Giê-hô-vaÍt nhất 70.000 người tái phạm tội và “người không xã hội”Một số lượng không xác định các đối thủ chính trị và các nhà hoạt động của Đức.Hàng trăm hoặc hàng nghìn người đồng tính luyến ái (có thể được bao gồm trong 70.000 người tái phạm tội và số “asocials” ở trên).

Sự khởi đầu của Holocaust

Vào ngày 1 tháng 4 năm 1933, Đức Quốc xã kích động hành động đầu tiên của họ chống lại người Do Thái Đức bằng cách tuyên bố tẩy chay tất cả các doanh nghiệp do người Do Thái điều hành.

Các Luật Nuremberg , ban hành ngày 15 Tháng 9 năm 1935, được thiết kế để loại trừ người Do Thái khỏi đời sống công cộng. Luật Nuremberg tước quyền công dân của người Do Thái Đức và cấm kết hôn và quan hệ tình dục ngoài hôn nhân giữa người Do Thái và người ngoại bang. Những biện pháp này đặt tiền lệ pháp lý cho luật chống Do Thái sau đó. Đức Quốc xã đã ban hành nhiều luật chống người Do Thái trong vài năm sau đó: Người Do Thái bị cấm vào các công viên công cộng, bị sa thải khỏi các công việc dân sự và buộc phải đăng ký tài sản của họ. Các luật khác cấm các bác sĩ Do Thái điều trị cho bất kỳ ai khác ngoài bệnh nhân Do Thái, trục xuất trẻ em Do Thái khỏi các trường công lập và đặt ra các hạn chế đi lại nghiêm trọng đối với người Do Thái.

Mặt tiền đổ nát của các cửa hàng thuộc sở hữu của người Do Thái ở Berlin sau Kristallnacht. Hình ảnh Bettmann / Getty

Vào đêm ngày 9 và 10 tháng 11 năm 1938, Đức Quốc xã kích động một cuộc tấn công chống lại người Do Thái ở Áo và Đức được gọi là Kristallnacht (Đêm của thủy tinh vỡ, hay dịch theo nghĩa đen từ tiếng Đức, “Đêm pha lê”). Điều này bao gồm việc cướp bóc và đốt phá các giáo đường Do Thái, phá cửa sổ các cơ sở kinh doanh do người Do Thái làm chủ và cướp phá các cửa hàng đó. Vào buổi sáng, kính vỡ vương vãi khắp mặt đất. Nhiều người Do Thái đã bị tấn công hoặc bị quấy rối, và khoảng 30.000 người đã bị bắt và đưa đến các trại tập trung.

Sau khi Thế chiến thứ hai bắt đầu vào năm 1939, Đức Quốc xã ra lệnh cho người Do Thái đeo ngôi sao màu vàng của David trên quần áo của họ để họ có thể dễ dàng bị nhận ra và nhắm mục tiêu. Những người đồng tính cũng bị nhắm mục tiêu tương tự và buộc phải mặc áo tam giác màu hồng.

Khu ổ chuột Lublin ở Ba Lan. Hình ảnh Bettmann / Getty

Sau khi Thế chiến thứ hai bắt đầu, Đức Quốc xã bắt đầu ra lệnh cho tất cả người Do Thái sống trong các khu vực nhỏ, tách biệt của các thành phố lớn, được gọi là các khu biệt lập. Người Do Thái bị buộc phải rời khỏi nhà của họ và chuyển đến những nơi ở nhỏ hơn, thường được chia sẻ với một hoặc nhiều gia đình khác.

Một số khu ổ chuột ban đầu mở cửa, điều đó có nghĩa là người Do Thái có thể rời khỏi khu vực vào ban ngày nhưng phải trở lại sau giờ giới nghiêm. Sau đó, tất cả các khu ổ chuột đều trở nên đóng cửa, có nghĩa là người Do Thái không được phép rời đi trong bất kỳ hoàn cảnh nào. Các khu biệt động lớn nằm ở các thành phố Bialystok, Lodz và Warsaw của Ba Lan. Những chiếc ghettos khác được tìm thấy ở Minsk, Belarus ngày nay; Riga, Latvia; và Vilna, Lithuania. Khu ổ chuột lớn nhất ở Warsaw. Lúc cao điểm tháng 3 năm 1941, một số 445.000 đã được nhồi nhét vào một khu vực chỉ 1,3 dặm vuông trong kích thước.

Quy định và thanh lý các Ghettos

Trong hầu hết các khu ổ chuột, Đức Quốc xã ra lệnh cho người Do Thái thành lập một Judenrat (hội đồng Do Thái) để quản lý các yêu cầu của Đức Quốc xã và điều chỉnh cuộc sống nội bộ của khu Do Thái. Đức Quốc xã thường xuyên ra lệnh trục xuất khỏi các khu ổ chuột. Tại một số khu ổ chuột lớn, mỗi ngày có từ 5.000 ��ến 6.000 người bị đưa đến các trại tập trung và tiêu diệt bằng đường sắt. Để khiến họ hợp tác, Đức Quốc xã nói với người Do Thái rằng họ đang bị chuyển đi nơi khác để lao động.

Khi chiến tranh thế giới thứ hai chống lại Đức quốc xã, họ bắt đầu một kế hoạch có hệ thống để loại bỏ hoặc “thanh lý” các khu nhà ở mà họ đã thiết lập thông qua sự kết hợp của giết người hàng loạt tại chỗ và chuyển những cư dân còn lại đến các trại tiêu diệt. Khi Đức Quốc xã cố gắng thanh lý Khu ổ chuột Warsaw vào ngày 13 tháng 4 năm 1943, những người Do Thái còn lại đã chống trả trong cuộc nổi dậy được gọi là Cuộc nổi dậy Warsaw Ghetto. Các chiến binh kháng chiến của người Do Thái đã chống lại toàn bộ chế độ Đức Quốc xã trong gần một tháng.

Trại tập trung

Mặc dù nhiều người gọi tất cả các trại của Đức Quốc xã là trại tập trung, thực tế có một số loại trại khác nhau , bao gồm trại tập trung, trại hủy diệt, trại lao động, trại tù binh và trại trung chuyển. Một trong những trại tập trung đầu tiên là ở Dachau, miền nam nước Đức. Nó mở cửa vào ngày 20 tháng 3 năm 1933.

Từ năm 1933 đến năm 1938, hầu hết những người bị giam giữ trong các trại tập trung là tù nhân chính trị và những người mà Đức Quốc xã gán cho là “người không có tâm”. Những người này bao gồm người tàn tật, người vô gia cư và người bệnh tâm thần. Sau Kristallnacht năm 1938, cuộc đàn áp người Do Thái trở nên có tổ chức hơn. Điều này dẫn đến số lượng người Do Thái bị đưa đến các trại tập trung tăng theo cấp số nhân.

Cuộc sống trong các trại tập trung của Đức Quốc xã thật kinh khủng. Các tù nhân bị buộc phải lao động chân tay nặng nhọc và được cho ăn ít. Họ ngủ từ ba người trở lên trong một chiếc giường gỗ chật chội; giường chưa từng được nghe nói đến. Tra tấn trong các trại tập trung là phổ biến và thường xuyên xảy ra tử vong. Tại một số trại tập trung, các bác sĩ Đức Quốc xã đã tiến hành các thí nghiệm y tế đối với các tù nhân trái với ý muốn của họ.

Xem thêm: Bản Chất Là Gì – Nghĩa Của Từ Bản Chất

Trại tử thần

Trong khi các trại tập trung nhằm mục đích làm việc và bỏ đói các tù nhân thì các trại tiêu diệt (còn được gọi là trại tử thần) được xây dựng với mục đích duy nhất là giết chết một nhóm lớn người một cách nhanh chóng và hiệu quả. Đức Quốc xã đã xây dựng sáu trại tiêu diệt, tất cả đều ở Ba Lan: Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor , Treblinka , Auschwitz và Majdanek .

Các tù nhân được vận chuyển đến các trại tiêu diệt này được yêu cầu cởi quần áo để họ có thể tắm. Thay vì tắm, các tù nhân bị dồn vào phòng hơi ngạt và bị giết. Auschwitz là trại tập trung và tiêu diệt lớn nhất được xây dựng. Người ta ước tính rằng gần 1,1 triệu người đã thiệt mạng tại Auschwitz.

Chuyên mục: Hỏi Đáp

from Sửa nhà giá rẻ Hà Nội https://ift.tt/2V6H9JN Blog của Tiến Nguyễn https://kientrucsunguyentien.blogspot.com/

0 notes

Text

today is 75th anniversary of Warsaw’s Ghetto Uprising

under the command of Mordecai Anielewicz. The Warsaw ghetto uprising was the largest, symbolically most important Jewish uprising, and the first urban uprising, in German-occupied Europe. The resistance in Warsaw inspired other uprisings in ghettos (e.g., Bialystok and Minsk) and killing centers (Treblinka and Sobibor).

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#OTD: This year, Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom Hashoah in Hebrew) is today, April 8th, according to the Jewish calendar. "Today, Days of Remembrance ceremonies to commemorate the victims and survivors of the Holocaust are linked to the dates of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising." (Ushmm.org) . "The #WarsawGhettoUprising (began in April 1943.) (It) was the 1943 act of Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto in German-occupied Poland during WW2 to oppose Nazi Germany's final effort to transport the remaining ghetto population to Majdanek and Treblinka concentration camps. ...The remaining Jews began to build bunkers and smuggle weapons and explosives into the ghetto... Hundreds of people in the Warsaw Ghetto were ready to fight, adults and children, sparsely armed with handguns, gasoline bottles, and a few other weapons that had been smuggled into the ghetto by resistance fighters." (Source: Wikipedia) . "The Warsaw ghetto uprising was the largest, symbolically most important Jewish uprising, and the first urban uprising, in German-occupied Europe. The resistance in Warsaw inspired other uprisings (fighting to save their lives) in ghettos (e.g., Bialystok and Minsk) and (in Nazi) killing centers (Treblinka and Sobibor)... Today, Days of Remembrance ceremonies to commemorate the victims and survivors of the Holocaust are linked to the dates of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising." ✡🕯📚🌹 📖(3rd paragraph source - & for more reading: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/warsaw-ghetto-uprising) 📷(This photo is a closeup of "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising;" source: Freepik.com. It is a cropped photo of the bronze sculpture of "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising" in Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Israel. The complete monument is on: Wikimedia. It was created by sculptor Nathan J. Rapoport in 1947. His special monument is a replica of the "Monument to the Ghetto Heroes" in Warsaw, Poland - also, sculpted by Rapoport.) #books #Holocaust #ww2 #sculpture #writersofinstagram #worldwar2 #history #writer #Shoah #art #wwii #bookstagram #WeRemember #HolocaustRemembranceDay #neverforget ✡📚🕯🌹

0 notes

Text

In October 2007, Serafinowicz dropped his attempt to use the Human Rights Act against the national newspapers; he had sought to prevent the publication of details revealing that his grandfather, Szymon Serafinowicz, was a member of the Belorusian Auxiliary Police who became the first man in the UK to be tried under the War Crimes Act.[23] Szymon was charged with direct involvement in three murders and personal involvement in the destruction of the Jewish populations of Mir and Minsk, including the 1941 massacre of the Mir Ghetto which resulted in the deaths of 1,800 people, but was found unfit for trial on grounds of dementia in 1997 and died later that year at the age of 86.[4]

Wow

What ever happened to Peter Serafinowicz

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

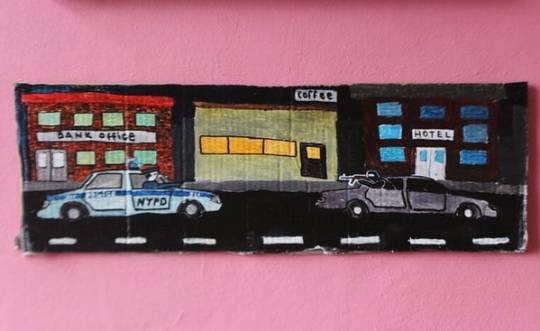

Жизнь в гетто (картон от коробки ≈20х45см, акрил, маркер. 2018г.) обменяю на 5 рублей которые пойдут на краски и другие материалы для новых произведений, либо на еду. #artist #avantgarde #funart #beauty #fineart #modernart #naiveart #illustration #contemporaryart #artgallery #арт #искусство #современноеискусство #художник #живопись #drawing #arte #kunst #минск #беларусь #instaminsk #minskgram #outsiderart #artstudio #artcollection #paintingart #underground #nypd #police # ghetto (at Minsk, Belarus)

#artgallery#police#illustration#fineart#contemporaryart#kunst#минск#paintingart#beauty#modernart#современноеискусство#живопись#funart#artist#underground#художник#artcollection#искусство#instaminsk#arte#беларусь#avantgarde#minskgram#drawing#naiveart#арт#outsiderart#nypd#artstudio

1 note

·

View note

Text

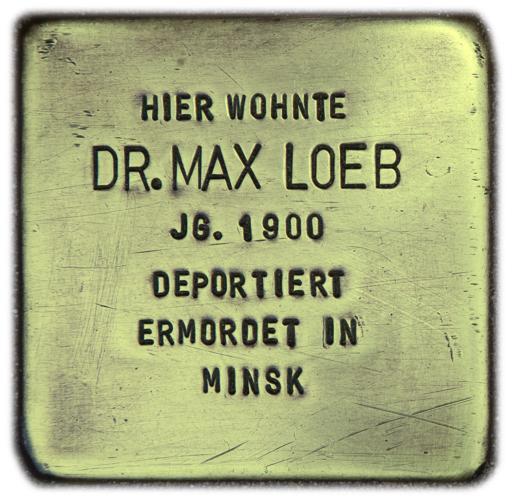

Dr. jur. Max Loeb

» Dr. jur. Max Loeb wurde in Irlich (heute Neuwied-Irlich) am 23. Januar 1900 als Sohn des Fabrikbesitzers Jakob Loeb und seiner Ehefrau Rosalie, geb. Cahn, geboren. Die Eltern besaßen die in Neuwied bekannte sogenannte "Bürstenfabik" in der Langendorfer Straße 50. Er legte 1922 am Kaiser-Wilhelm-Realgymnasium (heute: Eichendorff-Gymnasium) sein Abitur ab.

Er wohnte zusammen mit seiner Ehefrau Lilly Loeb, geb. Simon, in Neuwied, Augustastraße 7, und Köln. Als sein Beruf wird Diplom-Kaufmann und Rechtsanwalt angegeben. Seine Schwester Hertha emigrierte im November 1938 mit ihrem Ehemann Paul Marcus nach Uruguay; sie konnte aber ihren Bruder nicht überreden, sie zu begleiten.

Das nebenstehende Hochzeitsfoto wurde im September 1927 aufgenommen. Es zeigt in der Mitte Max' Schwester Hertha mit ihrem Ehemann Paul Marcus, zudem Max Loeb (2. von links), den Fabrikbesitzer Jakob (1. von rechts) und dessen Ehefrau Rosalie (3. von links).

Von seinem Vater erbte er das zwischen 1914 und 1920 erworbene Haus Moltkestraße 8 in der Koblenzer Südstadt, das am 29.5.1940 "arisiert", also enteignet wurde.

Am 15. November 1938 wurde Dr. Max Loeb im Zwangsarbeiterlager Bardenberg inhaftiert. Am 20. Juni 1942 wurde er ab Köln in das Ghetto Minsk deportiert und in der Tötungsstätte Maly Trostinec ermordet.

Winfried Nachtwei, MDB a.D. präsentiert auf seiner Website einen ausführlichen Bericht zu der Einweihung des zweiten Abschnitts der Gedenkstätte Maly Trostinec am 29.6.2018 und liefert umfangreiche Hintergrundinformationen über diese größte NS-Vernichtungsstätte in der ehem. Sowjetunion. «

»[...] Schuld die auch wir hätten begehen können [...]«

Quelle & weitere Informationen => http://stolpersteine-neuwied.de/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=140:loeb-dr-jur-max-2&catid=8&Itemid=119 [abgerufen am 2020-01-22]

Vergessen ist der Ausgangspunkt von Wiederholung.

Unless the world learns the lesson these cruel fates teach, night will fall.

Zeugnisse jüdischen Lebens und Leidens in Neuwied | Rolf Wüst, verantwortlich für das Projekt „Stolpersteine" im Deutsch-Israelischen Freundeskreis Neuwied, hielt im voll besetzten „Café Auszeit" der Marktkirchengemeinde einen Vortrag über „Zeugnisse jüdischen Lebens und Leidens in Neuwied". In einer ausführlichen Einleitung untersuchte er das Verhältnis der Gesellschaft zum Judentum früher wie heute, das oftmals zwischen den Extremen Ablehnung und Hass einerseits und Idealisierung und übersteigerten Erwartungen andererseits oszilliert. http://www.nr-kurier.de/artikel/66565-zeugnisse-juedischen-lebens-und-leidens-in-neuwied

Holocaust | Mehr als ein Trostpflaster | Über die Stolpersteine ging man irgendwann hinweg. Dann kam ein privates Forscherteam mit einem aufrüttelnden Buch. http://www.zeit.de/2017/05/stolpersteine-forschung-nationalsozialismus-opfer-oswald-pander/komplettansicht

Stolpersteine gegen das Vergessen Mehr als 5500 Stolpersteine erinnern in Hamburg an die Opfer des Holocaust. Mit selbstgemachten Schablonen und Kreidefarbe gibt die Schülerin Nele Borchert ihnen nun ein Gesicht. 2 min Datum: 25.01.2019 https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/heute-plus/videos/stolpersteine-gegen-vergessen-100.html

#Dr. jur. Max Loeb#Erinnerung#Vergessen#Wiederholen#Stolpersteine#Neuwied#Nazi-Opfer#rsopstolpersteine

0 notes

Photo

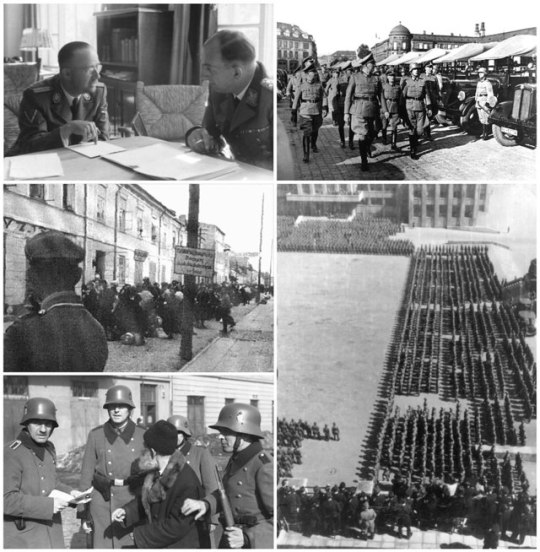

Clockwise from top left: Kurt Daluege (right), Chief of the Order Police, with Heinrich Himmler, 1943

Unit inspection at Strasbourg, 1940: Daluege (centre), with Bomhard, and Winkler

Ordnungspolizei in Minsk, Reichskommissariat Ostland, 1943

Police raid (razzia) in the Kraków Ghetto, January 1941

Biała Podlaska Ghetto liquidation action, 1942

The Ordnungspolizei (German: [ˈʔɔɐ̯dnʊŋspoliˌt͡saɪ], Order Police), abbreviated Orpo, were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany between 1936 and 1945.[2] The Orpo organisation was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly on power after regional police jurisdiction was removed in favour of the central Nazi government (verreichlichung of the police). The Orpo was under the administration of the Interior Ministry, but led by members of the Schutzstaffel (SS) until the end of World War II.[2] Owing to their green uniforms, Orpo were also referred to as Grüne Polizei (green police). The force was first established as a centralised organisation uniting the municipal, city, and rural uniformed police that had been organised on a state-by-state basis.[2]

The Ordnungspolizei encompassed virtually all of Nazi Germany's law-enforcement and emergency response organisations, including fire brigades, coast guard, and civil defence. In the prewar period, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and Kurt Daluege, chief of the Order Police, cooperated in transforming the police force of the Weimar Republic into militarised formations ready to serve the regime's aims of conquest and racial annihilation. Police troops were first formed into battalion-sized formations for the invasion of Poland, where they were deployed for security and policing purposes, also taking part in executions and mass deportations.[3] During World War II, the force had the task of policing the civilian population of the conquered and colonised countries beginning in spring 1940.[4] Orpo's activities escalated to genocide with the invasion of the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa. Twenty-three police battalions, formed into independent regiments or attached to Wehrmacht security divisions and Einsatzgruppen, perpetrated mass murder in the Holocaust and were responsible for widespread crimes against humanity and genocide targeting the civilian population.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordnungspolizei

0 notes

Text

#UnDíaComoHoy: 11 de septiembre en la historia

El 11 de septiembre es el 254.º día del año. Quedan 110 días para finalizar el año. A continuación te presentamos una lista de eventos importantes que ocurrieron unía como hoy 11 de septiembre.

-En Venezuela se celebra el Día de la Virgen De Coromoto. Santa María de Coromoto en Guanare de los Cospes o Virgen de Coromoto es la patrona de Venezuela y, desde el 19 de noviembre de 2011 Patrona Principal de la Iglesia arquidiocesana de Caracas luego que la Santa Sede aprobó su designación. Es una advocación mariana, venerada tanto en la ciudad de Guanare, donde apareció hace 361 años, como en toda Venezuela. En 1950 el Papa Pío XII la declaró Patrona de Venezuela, el Papa Juan Pablo II la coronó en su visita al Santuario mariano en Guanare y el Papa Benedicto XVI elevó en 2006 al Santuario Nacional de Nuestra Señora de Coromoto a la categoría de Basílica Menor.

-1906: Mahatma Gandhi inicia su ‘Movimiento de No Violencia’.

-1913: nació Jacinto Convit médico y científico venezolano, conocido por desarrollar la vacuna contra la lepra y sus estudios para curar distintos tipos de cáncer. Recibió el Premio Príncipe de Asturias de Investigación Científica y Técnica de 1987 y fue nominado al Premio Nóbel de Medicina en 1988. Falleció en mayo de 2014 a la edad de 100 años.

-1926: en Roma (Italia) en un atentado contra Benito Mussolini resultan heridos ocho transeúntes.

-1940: nace Brian De Palma, cineasta estadounidense. Conocido por films como Scarface, The Untouchables, Mission: Impossible, Dressed to kill, Carrie.

-1940: George Stibitz, hace la primera operación remota desde un teléfono hacia una computadora.

-1941: en Estados Unidos empiezan las excavaciones para la construcción del Pentágono. El Pentágono es la sede del Departamento de Defensa de los #EstadosUnidos. El edificio tiene forma de pentágono, y trabajan en él aproximadamente 23.000 empleados militares y civiles, y cerca de 3.000 miembros de personal de apoyo. Se halla en el condado de Arlington, Virginia. Tiene cinco pisos, cada uno de los cuales incluye cinco corredores. La construcción del Pentágono comenzó el 11 de septiembre de 1941 (poco antes del ingreso de los Estados Unidos en la II Guerra Mundial), fue inaugurado el 15 de enero de 1943.

-1943: en Minsk y Lida, los nazis comienzan el exterminio del ghetto judío. Durante el régimen nazi, Alemania reintrodujo el sistema de “guetos” en Europa Oriental para confinar a la población judía, y a veces también a la población gitana, lo cual facilitó su control por parte de los nazis. Los habitantes de los guetos de Europa del Este fueron transportados desde diferentes partes de Europa, privados de cualquier derecho, hacinados en pésimas condiciones, mal alimentados y obligados a trabajar para la industria bélica alemana. De ahí eran gradualmente deportados a campos de exterminio durante el Holocausto. El sistema de guetos constituía la primera escala del proceso de deportación y exterminio de los hebreos de Europa.

-1951: Florence Chadwick es la primera mujer que atraviesa nadando el Canal de la Mancha Inglaterra-Francia en ambas direcciones.

-1961: se funda la World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF) (Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza). Esta es la más grande y respetada organización conservacionista independiente del mundo. Su misión es detener la degradación del ambiente natural del planeta y construir un futuro en el cual los seres humanos vivan en armonía con la naturaleza, conservando la diversidad biológica del mundo, garantizando el uso sustentable de los recursos naturales renovables y promoviendo la reducción de la contaminación y del consumo desmedido. WWF cuenta con unos 5 millones de miembros y una red mundial de 27 organizaciones nacionales, 5 asociadas y 22 oficinas de programas, que trabajan en más de 100 países. La sede internacional está ubicada en Suiza y la dirección para América Latina, en Estados Unidos. La organización ha jugado un papel fundamental en la evolución del movimiento ambientalista internacional, rol que continúa en pleno crecimiento y desarrollo. Entre sus socios destacan Organizaciones de las Naciones Unidas, la Unión Mundial para la Naturaleza (UICN), Traffic, la Comisión Europea y entidades de financiamiento como el Banco Mundial, con el cual WWF ha formado una alianza para favorecer los bosques del planeta. Actualmente también esta asociado con Microsoft Game Studios y Blue Fang Games en el popular juego Zoo Tycoon 2, estos últimos donan 100.000 dólares en la ventas de cada una de las expansiones del juego, promoviendo la conservación de especies.

-1962: en Inglaterra, The Beatles terminan de grabar su primer single Love Me Do.

-1973: en Chile, Augusto Pinochet derroca a Salvador Allende, quien muere ese mismo día, y da inicio a un régimen militar de 17 años.

-1977: nace Jon Buckland, guitarrista británico, de la banda Coldplay.

-1981: el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York, MoMA, entrega a España el Guernica, célebre cuadro de Pablo Picasso pintado en 1937. El 26 de abril de 1937, durante la Guerra Civil española, la aviación alemana, por orden de Francisco Franco, bombardeó el pueblo vasco de Guernica. Pocas semanas después Picasso comenzó a pintar el enorme mural conocido como Guernica. Fue realizado en menos de dos meses, por encargo del Gobierno de la República Española para ser expuesto en el pabellón español durante la Exposición Internacional de 1937 en París, con el fin de atraer la atención del público hacia la causa republicana en plena Guerra Civil Española. En la década de 1940, puesto que en España se había instaurado el régimen dictatorial del general Franco, Picasso optó por dejar que el cuadro fuese custodiado por el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York, aunque expresó su voluntad de que fuera devuelto a España cuando volviese al país la democracia. En 1981 la obra llegó finalmente a España. Se expuso al público primero en el Casón del Buen Retiro, y luego, desde 1992, en el Museo Reina Sofía de Madrid, donde se encuentra en exhibición permanente.

-1987: El cuadro de Van Gogh, Los Girasoles es subastado a un precio récord en la época, 320 millones de francos.

-1987: muere Peter Tosh, reconocido músico jamaicano, miembro de The Wailers.

-2001: ocurre el atentado de las Torres Gemelas, el Pentágono y un avión en Pensilvania, donde en total fallecen casi 3000 personas. El World Trade Center era un complejo ubicado en la isla de Manhattan de Nueva York, Estados Unidos donde se situaban las Torres Gemelas, dos grandes edificaciones diseñadas por el arquitecto estadounidense de origen japonés Minoru Yamasaki. Fueron destruidas tras estrellarse dos aviones comerciales secuestrados en los atentados del 11 de septiembre de 2001 donde fallecieron 2.749 personas. Este ha sido el peor de los desastres en Nueva York hasta la fecha. El World Trade Center fue uno de los grandes símbolos del capitalismo financiero internacional: 430 compañías de 28 países, la mayoría pertenecientes al ámbito financiero, tenían oficinas arrendadas en los rascacielos. Entre ellas, por citar sólo algunas, el Banco de América, Morgan Stanley, American Express o el Grupo de Crédito Suizo.

-2001: la Asamblea de la OEA aprueba la Carta Democrática Interamericana.

La entrada #UnDíaComoHoy: 11 de septiembre en la historia aparece primero en culturizando.com | Alimenta tu Mente.

1 note

·

View note