#minoan snake priestess

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

a line-up of the "main characters" of the Museum Squad! Or the Museum Friends. Or the Museum Scouts? I don't know what they're called but they're a bunch of art history objects that live in a Museum and they have art history adventures!!! in the group pic from left to right: Bastet, Haniwa, Dogū, Minoan Snake Priestess, Jizō, and Colima Dog. Most of them are just named after what they are, but I need to name the minoan snake priestess I think. Maybe just Minoa? Her snakes are definitely Lefty and Righty

#my art#museum squad#bastet#haniwa#dogu#minoan snake priestess#jizo#colima dog#mostly i just made these images so that their artfight/toyhouse entry didn't look so weird with just the one illustration lol#i'm not sure i'm really happy with this style but any image completed is good

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

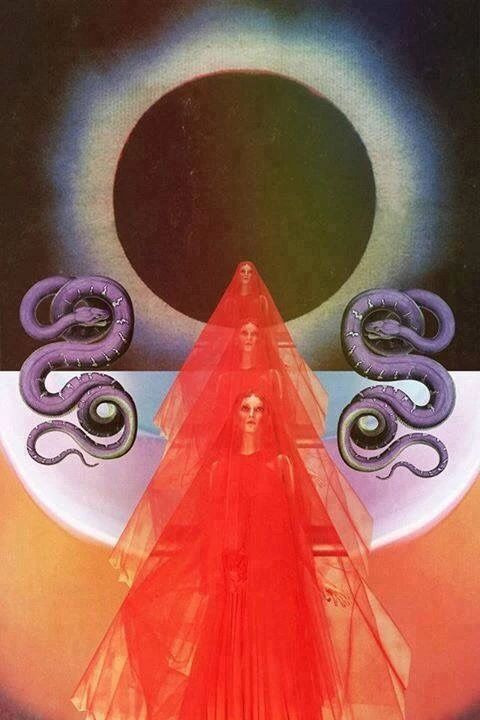

#snake priestess#modern minoan snake goddess#sorceress#witchy art#occult art#esoteric#collage art#dark moon#moon eclipse

91 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Britomartis

Britomartis, also known as Diktynna (Dictynna), was the Cretan goddess of hunting and fishing nets in Greek mythology. Although referred to as a nymph and worshipped locally, she had at least two significant and active shrines, one in Crete and another in Aigina, where worshippers would bring offerings. They regarded her as a vanished maiden immortalized and deified by Artemis.

According to her most popular myth, Britomartis, meaning "sweet maiden," was an exceptional huntress and a beloved companion of Artemis. As such, she had vowed to remain a virgin. Nevertheless, King Minos desired her and relentlessly pursued her for nine months. He eventually caught her atop a high peak and attempted to seize her, but Britomartis leaped from the cliff into the sea to escape. She was recovered by fishermen's nets (diktuon) and brought to the island of Aigina. There, Artemis transformed her into the goddess of the nets, Diktynna, to preside over her own cult.

Despite her clear Cretan origins, Britomartis/Diktynna was likely a minor goddess who was reintroduced into the Bronze Age pantheon of the island by Classical Greek writers. Over time, Diktynna came to be associated with divine genealogies and was even included among the children of Leda by Zeus, Apollo and Artemis. Her cult remained popular throughout the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial periods, as evidenced by the archaeological remains of her sanctuaries and the coins bearing her image.

In Minoan Religion

The Cretan system of sacred beliefs and practices is marked by impressive processions, bountiful sacrifices and offerings, mystery symbols such as the double-axe (labrys), and ritual activities such as bull-leaping. It also features painted and sculpted images of female characters commonly interpreted as goddesses or priestesses, most typically with raised arms. Some of these goddesses/priestesses are shown holding snakes, which led Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941), the key figure in the discovery of the Minoan civilization, to suggest they may represent a 'Great Mother Goddess' and her fellow associates.

The discovery of numerous inscriptions at Knossos, an archaeological site he believed to be King Minos' palace, convinced Evans that deciphering these inscriptions would reveal a clear understanding of his material finds and their significance in the Minoan religion and culture. He dedicated his life to this effort, only to find that the inscriptions represented three different scripts: Cretan Hieroglyphs, Linear A, and Linear B. While the first two scripts remain undecoded, the Linear B script was eventually deciphered by Michael Ventris (1922-1956). As nearly all the tablets read since then contain administrative and commercial records, understanding the Minoan religion has largely remained dependent on drawing parallels between pieces of visual evidence from art, archaeology, and architecture. In other words, we have no written evidence yet that can directly tell us what the Minoans used to call their goddess or goddesses.

Minoan Snake Goddess, Knossos.

Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

Still, there is a foundational agreement among the scholars that the Minoan religion, like many other aspects of this culture, was later adopted or adapted by the Mycenaeans and Greeks. Just as Michael Ventris demonstrated that the language of Linear B inscriptions is an early form of Classical Greek, scholars such as Jennifer Larson explain that

From its beginnings in the Bronze Age, “Greek” religion was a synthesis. The strong influence of Minoan ideas and aesthetics is clearly discernible in the material culture of Mycenaean religion…

(138)

The idea of the persisting prominence of several gods and goddesses such as Zeus, Apollo, Dionysus, and Athena from the Minoan down to the Mycenaean and Greco-Roman cultures finds material support in the names of these deities on a few Linear B tablets. These tablets were discovered at the Palace of Nestor in the Mycenaean city of Pylos, c. 1200 BCE. The tablets list the offerings and sacrifices that were dedicated, or must be dedicated, to each deity. On one tablet, Tn 316, the divine recipients of gold vessels include Zeus, Hermes, Hera, and Potnia. The name Potnia, written as po-ti-ni-ja in Linear B, means "The Female God Who Has Power." This title was given to several important goddesses in Minoan Crete, sometimes as an epithet, e.g. Potnia Athena, sometimes denoting the geographical or functional attribute of the goddess, e.g. Potnia Hippia (Mistress of the Horses), and sometimes solely as her name or title. If we trust that Potnia must be the Minoan/Mycenaean designation for sacred female figures in the Minoan art because they are both noticeably frequent, then it is likely that this Minoan/Mycenaean great goddess survived the Bronze Age Collapse and made her way into the Archaic Greek pantheon in the form of one or more female deities.

Since the Bronze Age goddess was often featured concerning warfare and protection, most scholars suggest that Athena is the Greek revival of Potnia. Nevertheless, the Cretan goddess, who was consistently honoured and praised by Greek writers from the 5th century BCE onwards, was Britomartis/Diktynna. And she was explicitly linked to Artemis and, later, to her divine family.

Minoan Gold Signet Ring with Three Figures before a Temple

Nathalie Choubineh (CC BY-NC-SA)

Continue reading...

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Minoan Civilization: A Surprisingly Modern Society

The Minoan civilization, which flourished on the island of Crete, is renowned for its advanced and, for its time, unusually liberal society. Although our knowledge of the Minoans is incomplete due to limited written sources and primarily based on archaeological finds, a picture emerges of a culture that, from around 2700 to 1450 BC, exhibited remarkable openness, equality, and joie de vivre.

Equality and Tolerance

Current archaeological and anthropological studies often highlight the Minoans' liberal attitude. Researchers like Nanno Marinatos have examined the religious and social structures of the Minoans and found that this society exhibited an unusually high level of gender equality for its time. Women actively participated in public life, possibly held leadership positions such as priestesses, and enjoyed similar rights to men in the private sphere.

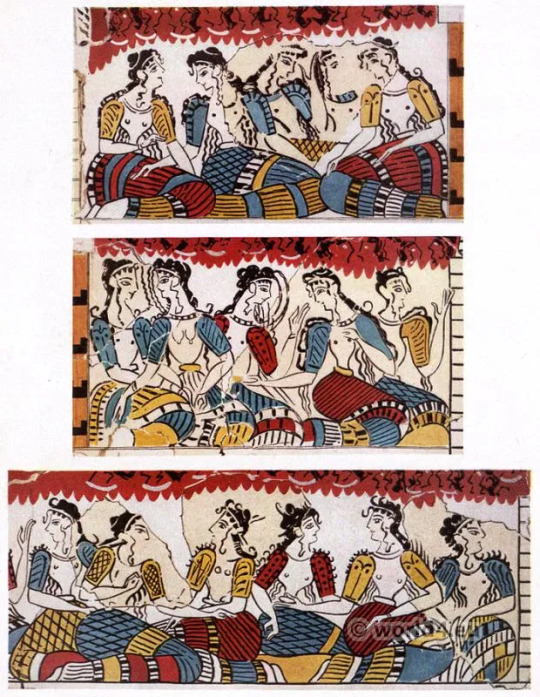

Regarding sexuality, the Minoans also appear to have adopted a tolerant attitude. Artistic depictions of intimate relationships between same-sex individuals suggest that such relationships were accepted in Minoan society. Although the interpretation of these depictions is debated among scholars, there are numerous indications that the Minoans had a more open stance towards various forms of love and romance, including same-sex relationships. The portrayal of homoerotic scenes in art and a relaxed attitude towards sexuality indicate that such relationships were accepted and respected in Minoan society.

Katherine A. Schwab: Her work on Minoan frescoes and the analysis of the scenes depicted provide insights into the social dynamics and possible homoerotic aspects of Minoan culture. Current archaeological and anthropological studies often emphasize the Minoans' liberal attitude. Researchers like Nanno Marinatos have examined the religious and social structures of the Minoans and found that this society exhibited remarkable openness and tolerance towards various lifestyles.

Cultural and Social Freedom

Minoan culture was characterized by its artistic flourishing and a preference for the beautiful and pleasurable. The Minoans were masters in the art of fresco painting, ceramics, and architecture. Their palaces, such as the famous Palace of Knossos, were not only political and economic centers but also places of art and culture.

The Minoans lived in close contact with nature, as reflected in their frescoes, which often depicted dolphins, lilies, and other natural motifs. This deep connection with the natural environment is also evident in their appreciation of water, which likely played a significant role in ritual purification and bathing practices.

Festivals, dances, and athletic competitions were integral parts of social life. These events provided not only entertainment but also strengthened the Minoan community and identity through shared experiences.

Religion and Spirituality

Religion played a central role in the lives of the Minoans, and their spiritual practices reflected their liberal values. The Minoan religion was matriarchal, with goddesses such as the Snake Goddess being central figures. The worship of goddesses is often associated with the high status of women in society, as they symbolized aspects such as female fertility and the power of nature.

Rituals and religious ceremonies were opportunities for the community to gather, celebrate, and express their connection with nature and the divine. These rituals, often accompanied by music and dance, emphasized harmony and unity with the environment.

The Minoan civilization was, in many ways, a fascinating and progressive culture, whose societal structure differed from many other ancient cultures. Their values of equality, cultural freedom, and spiritual connectedness remain relevant and inspiring today. The Minoans show us that progressive societal forms were not only a phenomenon of modernity but also existed in antiquity.

Text supported by GPT-4o, Gemini AI

Base images generated with DALL-E, overworked with SD-1.5/SDXL inpainting and composing.

#MinoanCivilization#AncientCrete#Archaeology#HistoricalSociety#LiberalCivilizations#ArtHistory#AncientEconomics#culturaldevelopment#gayart#queer#manlovesman#LGBT#gaylove

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snake Girl Sketch - Based on Minoan Snake Priestess.

This one took me two hours to draw, but she really came out beautifully.

#creatuanary#creatuanary2024#fantasy oc#ink drawing#sketchbook#snake hair#snake goddess#medusa#cute Medusa#gorgon#gorgon oc#priestess#snakes#snake art#three eyes#snake girl#kawaii#kawai girl#Medusa oc#snake#Python#minoan#myth oc#greek myth art#greek mythology#dnd oc#pretty#snake people#snake princess#princess

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Minoan Snake Goddess / Priestess

🐍 🐍 🐍

#minoan#ancient greece#ancient crete#tagamemnon#greek mythology#bronze aegean#kurjdraws#i hate the hat and i got rid of it#my minoan art

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks for @flashfictionfridayofficial for the prompt!

~

Warnings: for violence and mentions of blinding.

~

The creature was old, as old as it was possible to be, maybe. As old as the dark before sunshine. So when Odysseus saw it gleaming even from a distance, it didn't take him aback too much. Snakes and lizards seek warmth, it is their nature, and they love light and bask in the sun. This creature followed those themes, for it was snake and lizard and sun all at once. And of course you know what can happen when one looks at the sun.

So when Odysseus knew he had to talk with the Hydra, he steeled himself, and sought the aid of his friend and a great priestess. And as the Minoan priestess approached, knife held trembling in her hand, he stared at the Hydra's glowing, discarded scale. As she raised her knife to save his life at the cost of his sight, he fixed that glowing scale in his memory, the last he would ever see.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minoan Gods

Decided to take an old article and repackage it for the tumblr audience.

The double-edged axe or labris, likely the least controversial thing written here.

To honor the latest release of Minotaur Hotel I decided to do an article on what is known of the Minoan deities.

Known as the “first European city-makers” and a distant precursor to Greece, what is called the Minoan Civilization after King Minos of Crete was a mysterious Bronze Age nation that governed Crete and neighbouring parts of the Aegean. Its age, likely influences over posterior Greek (and by extension western) culture and unique art has long made it a subject of mystique and intrigue. Whereas it’s the several still undeciphered scripts and languages or the fact that it seems to have a rare genuinely matriarchal society, it seems the countless research and academia only raises more questions than answers.

One such well documented but ultimately unsuccessful endeavour is identifying the pantheon these people worshipped. It is strongly speculated that Minoan Crete was theocratic (Kristiansen & Larsson, 2005, among several others) and several art either represents cultic activities (such as the famous bull leaping) if not gods themselves, but in the absence of the proper written word this is beyond impossible to ascertain. The implications of understanding Minoan religion are very clear, as beyond offering a snapshot to the lives of these people it also bears the potential implication that many Greek gods and mythological figures ultimately had their origins here.

To completely compile, summarise and synthesize all that has been written on Minoan religion is a task far too vast to implement, so here are some of the most widely agreed upon gods.

Queen of the Gods

Snake goddess figurine by C messier. The most well known Minoan possible religious artifact, it’s still not clear if these figurines represent a goddess, multiple goddesses or human priests.

By far the most well kown figure attributed to Minoan religion is the Queen or Mother goddess, sometimes known as “Snake Goddess” due to an abundance of figurines depicting women holding snakes. Perhaps surprisingly (or not given the second paragraph), she’s not actually attested anywhere, given that Minoan scripts haven’t yet been deciphered, but her existence can be inferred due to a variety of factors:

Female figurines are by far the most common representation of what could be interpreted as a god in Minoan sites. Chief among these are the aforementioned “snake goddess” figurines. While there is considerable debate on whereas these truly represent deities (plural or singular) or mortal priestesses, they are comparable to apotropaic depictions of surrounding cultures, most notably those of the latter Athena Parthenos which similarly is associated with serpentine iconography as controlling these forces of chaos (Ogden 2013).

The fact that Minoan society was matriarchal in nature, which would lend credence to the supreme being in their cosmology being feminine in nature. While a dominant female deity does not always correlate to a matriarchal society (i.e. Amaterasu, Virgin Mary, et cetera), the opposite, a matriarchal society with a masculine supreme god, is yet to be documented (though see below).

Several Greek mother goddesses such as Demeter and Rheia are thought to have a Cretan origin (Mylonas 1966, Sidwell 1981 among several others), so it’s not terribly hard to see them as “descendents” of this Minoan deity.

The Philistines, contray to biblical assertions on Dagon worship, seem to have favoured a goddess as their primary deity (Schäfer-Lichtenberger 2000, Ben-Shlomo 2019). The Philistines, through genetic legacy and material culture, are now understood to have had an Aegean origin, so again seeing this as a continuation of a Minoan goddess is plausible.

Several names have been speculated for this deity, usually along the lines of the author’s interpretation of Minoan scripts (which should be noted, are not only undeciphered but very likely don’t mention deities at all, since all we have seem to brief texts likely attributed to tax reports). The name “Rhea” doesn’t seem to be of Indo-European origin (Nilsson 1950, Sidwell 1981), making it very likely that this is a theonym with Minoan origins. The same applies to Ariadne (Alexiou 1969) and possibly also Athena (Beekes 2009). Conversely, the Philistine goddess is possibly attested as “Ptgyh” (Ben-Shlomo 2019), a name that is speculated to be related to Greek “Potnia”, “mistress”. In all likelihood, such an important goddess likely was known by a variety of epithets.

Fertility is naturally considered a major function of this mother goddess, but perhaps in ways one might not expect. An emphasis on solar worship has been noted due to temple arrangements and material objects such as “frying pans” with solar iconography (Ridderstad 2009), suggesting that, rather than an earth goddess as one might expect, this was a solar goddess. Solar goddesses are known from a variety of Near Eastern cultures such as Egypt (Sekhmet, Hathor), Anatolia (Arinniti, Istanu, Estan, Wurunsemu) and Canaan (Shapash) so a solar interpretation of the Minoan supreme goddess isn’t unusual. In particular, this might imply a more “chthonic” interpretation of the sun than the Classical “object in the sky”, due to temple angles tressing sunrises and sunsets (Ridderstad 2009), whch is consistent with the Hittite notions of the sun goddess ruling the underworld. Regardless, as noted below in Talos there is also possible evidence for a Minoan male sun.

More unambiguously, this goddess had a civil and possibly domestic function. As noted above snake goddess figurines might be apotropaic in nature, used to ward off evil spirits or more mundane threats like snakes. If Athena is derived from this goddess then a role as the protector of the palace is also implied given Athena’s role in the Mycenaean era, and both Ariadne and Athena are associated with weaving. Conversely, so are solar goddesses in other places, like the Baltic Saule or the Turkic Gun Ana, as the rays of the sun are easily linked to threads, further suggesting this role for the Minoan goddess. Both Rhea and Demeter are also associated with lions, animals that not only are symbolic of the sun but also of a notable sun goddess across the sea, Sekhmet.

The fact that the Minoan ruling goddesses was the possible genesis for several Greek goddesses like Rheia, Demeter, Ariadne and Athena suggests a rather extensive and important function in ancient Cretan religion. Conversely, it might also suggest that what we might attributing to a single goddess was in fact several different deities, but as deities overlap and flow into one another it is possible that these goddesses were either seen as one or acquired independent identities several times throught Minoan history.

The Bull God

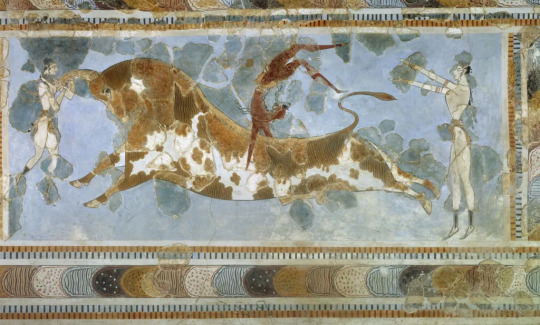

Bull-leaping fresco. A stapple of Minoan art.

The bull is extensively depicted in Minoan art. Most common are bull-leaping frescos depicting youths of both genders leaping or interacting with bulls, suggesting this was a common Minoan sport and perhaps even a religious ritual. But bulls are depicted in many other contexts as well, and as such the existence of an actual Minoan bull god is frequently speculated upon.

In Near-Eastern cultures, bulls are both solar and lunar symbols. On the one hand, the bull’s horn/s resemble/s a lunar crescent, and indeed not only are Middle Eastern male moon gods like Nanna and Suen associated with the bull but even the Greek Selene is described as having a chariot pulled by bulls, suggesting that not even a shift towards a feminine moon deity erased this iconography. On the other hand, a bull is a powerful animal and thus worthy of male solar gods, most notably the Mesopotamian Marduk (literally “calf of the sun”). Sometimes both interpretations show up in the same culture: in Egypt the Apis bull is associated both with Ra and with Osiris as Yah (the moon). Perhaps the same applied to ancient Crete (again, see Talos below), but a lunar bull would certainly be a vivid symbol contrasted against the sun goddess.

The bull is associated with Dionysus which otherwise is mired in more “exotic” symbols, suggesting that the putative “Minoan Dionysus” might be the bull god. It has long been speculated that the bull god is a male youth and son and consort to the queen of the gods, though women are also depicted bull leaping.

The Greek minotaur has long been speculated to be a remnant of the Minoan bull god, not without reason being so throughly linked with Crete as a concept. In this case, the monstrous depiction is either fully discontinuous from older practises or defamatory, with my personal two cents that it is also a jab against the bull gods of the Phoenicians, accused at the time of human sacrifice by the (infant killing) Greeks. Asterion is said to be the birth name of the minotaur by Pseudo-Apollodorus, but I wouldn’t read much into this since this name (literally “starry one”) is a common Greek name for many figures both historical and mythological, and at any rate a recent Indo-European name at odds with the most likely Pre-Greek Cretan languages.

“Dionysus”

“Prince of the Lilies” fresco, often but by no means universally interpreted as a male youth figure.

There is extensive evidence of wine cults in Minoan Crete (Kerényi 1976). This, combined with the Mycenaean depictions of a bull-horned Dionysus (or “di-wo-nu-so” as it is) seems to point to a Minoan origin for this god. “Dionysus” is an Indo-European name connected to Zeus and other sky father figures but the actual character of the god is not easily identified in the PIE world, suggesting a Pre-Greek, local origin. A possible exception is the Lusitanian god Andaeico (Teixeira 2014) which might resemble the putative “flower Dionysus” (see below), but this deity is himself not well understood and might be from an ancient Iberian stratum in Lusitanian culture.

The Mycenaean Dionysus is a figure with stronger ties to death and rebirth than revelry necessarily but the evolution from “eldritch god” to “party dude” might not have been as linear (geddit) a concept as one might expect. Male figurines thought to represent a young god increase in popularity in later stages of Minoan history (Vasilakis 2001) as do male youth figures often identified as “prince of the lilies/flowers” which alongside the wine cults is closer to the Classical Dionysus than the Mycenaean or later Orphic one. However once more in the absence of deciphered scripts it is impossible to say for certainty that these figurines represent deities let alone are Dionysus. Hell, the “flowery figures” have even been interpreted as female at times.

If an actual god, the “Minoan Dionysus” might very well be identified with the bull god, as the bull is a rather odd symbol for the “exotic” attributes the Classical Dionysus is associated with. Ariadne in Greek myth does get hitched with Dionysus; an imbalanced, reversed remnant of the male youth/Minoan queen goddess pairing perhaps?

Talos

Talos by laura Jastrow.

Perhaps the only Minoan or at least Cretan god we may truly known by name is Talos. In Greek myth Talos is best known as the strange automaton made by Hephaestus, but it was also the Cretan word for “sun”, analogous to “Helios” of mainland Greece according to Hesychius of Alexandria. Zeus was worshipped in Crete as Zeus Talaios, who was associated with the sun, and the Tallaia was a spur of Mt. Ida associated with sunrise rituals (Nilson 1923).

This association of Zeus with Talos is as peculiar as it is extensive. Zeus, a god whose origins are well documented to be Indo-European in nature, is held in Greek myth as born and raised in Crete, and Cretan depictions of Talos differ from those of mainland Greece in having wings. Further, the seduction of Europa by Zeus as a bull links the Classical Zeus to Crete in a very fundamental way. This seems to indicate a rather through syncretism between the Greek/Mycenaean sky god and this indigenous Cretan deity, which in turn implies a rather relevant role to the Minoan Talos.

Conversely, outside of Crete Talos is an enigmatic figure, as noted by Pausanias himself which seems more confused than anything. Certainly, the story of a pre-sci-fi robot is weird, let alone how it relates to an ancient Cretan god, linked to the supreme god of all Greeks down to his very birth.

Talos is truly an anomaly. A solar god which was important enough to warrant syncretism with Zeus, in a matriarchal culture where the sun seems to have been traditionally the supreme goddess herself. Crete was likely never a monolith even at the height of Minoan rule, but all current signs point to Talos being an ancient Cretan deity from before PIE influences in Greece, and he seems so out of place.

My personal two cents is that Minoan cosmology was similar to that of the Hittites and other Anatolian cultures, where the sun is male during the day as it travels through the sky and female at night where it rules the underworld. Talos’ syncretism with Zeus therefore would be derived from representing the male, skyward aspect of the sun, corroborated by worship at the Tallaia. In the original Minoan religion Talos was probably lesser compared to his female aspect (which even as a chthonic deity would easily be accepted as the supreme power; even Mycenaeans favoured the chthonic Poseidon to the celestial Zeus after all), but his roled ensured syncretism with the king of the gods once Crete was conquered.

Britomartis

Candiacervus by Peter Schouten.

Britomartis is possibly another deity we might know from a genuinely Minoan or at least Cretan name. Solinus claims it is “sweet virgin” in Cretan and the name doesn’t seem to have Indo-European roots. If true, I’d imagine this theonym is more due to syncretism with the Greek Artemis if anything as I doubt ancient Minoans cared much about virginity as a concept, though Artemis herself may be derived from this deity. Some archaeologists have further suggested that it is an euphemism for the deity’s actual name, since being a goddess of the wilds saying it might have been unwise (Ruck 1994). Another name attributed to her is Diktynna, “hunting nets”, or simply Dicte/Dikte (unsurprisingly, she named said mountain, and was likely its spirit). I’ve never seen the etymology of this name tracked, so I can’t say for sure if it is Greek or Pre-Greek in origin

Britomartis is in Greek myth a mere oread or mountain nymph, said to have invented hunting nets. She is said to have fled Minos’ lust, a tale that even Siculus expressed disbelief at due to her divinity. Thus, although greatly diminuished by Hellenistic times, she was still clearly held to be a deity, and still seems to have been worshipped in Crete during Classical times, frequently appearing in coinage as a winged figured. She is equated to Artemis, a goddess associated with the wilderness and mountains, and it can be assumed she represents a similar “lady of the beasts” archetype. Artemis herself has a name of unclear etymology, and could be of Minoan origin, being perhaps another name for Britomartis.

Some authors tempt to lump Britomartis with the Minoan mother goddess, but to me these seem like clearly distinct figures. Whereas the queen of the gods is a civic, fertility and possibly solar figure, Britomartis is alcearly a goddess of the wild places, perhaps even more specifically the embodiment of Mt. Dicte. Of course, overlap between these two goddesses likely happened at several points in Cretan history.

And that’s it for now.

Other Minoan gods have been positted, including a sea one (naturally), but they aren’t sufficiently supported by everyone in the field at large, so I won’t bother.

References

Kristiansen, Kristian & Thomas B. Larsson. The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Ogden, Daniel (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 9780199557325 – via Google Books.

George Mylonas (1966), “Mycenae and the Mycenean world “

Sidwell, R.T. (1981). “Rhea was abroad: Pre-Hellenic Greek myths for post-Hellenic children”. Children’s Literature in Education. 12 (4): 171–176. doi:10.1007/BF01142761. S2CID 161230196.

Christa Schäfer-Lichtenberger, The Goddess of Ekron and the Religious-Cultural Background of the Philistines, Vol. 50, No. 1/2 (2000)

David Ben-Shlomo, Philistine Cult and Religion According to Archaeological Evidence, January 2019Religions 10(2):74, DOI: 10.3390/rel10020074

Nilsson, Martin Persson (1 January 1950). The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and its Survival in Greek Religion. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. ISBN 9780819602732 – via Google Books.

Alexiou, Stylianos (1969). Minoan Civilization. Translated by Ridley, Cressida (6th revised ed.). Heraklion, Greece.

Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009), Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Leiden and Boston: Brill

Marianna Ridderstad, Evidence of Minoan astronomy and calendrical practices, October 2009

Kerényi, Karl. 1976. Dionysus. Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691029156, 978-0691029153

Monteiro Teixeira, Sílvia. 2014. Cultos e cultuantes no Sul do território actualmente português em época romana (sécs. I a. C. – III d. C.). Masters’ dissertation on Archaeology.. Lisboa: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa.

Andonis Vasilakis, MINOAN CRETE: FROM MYTH TO HISTORY Paperback – January 1, 2001

Nilsson, “Fire-Festivals in Ancient Greece” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 43.2 1923

Carl A.P. Ruck and Danny Staples, The World of Classical Myth [Carolina Academic Press], 1994

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“It is important for women whose religions define them as inferior to men, based on the gender of God, to learn that before there was God, there was the Goddess. In ancient Greece, the original Trinity was the triple goddess as maiden, mother, and crone. Eleusis, just outside of Athens, was the site for the Eleusinian Mysteries, where for more than 2,000 years, until the temple was destroyed in 396 CE, people came and participated in a ritual and mystical experience, possibly with the aid of a hallucinogenic drink, and overcame the fear of death. It was Persephone, the divine daughter, rather than Jesus Christ, the divine son, who returned from the underworld realm of death, but the message, that death was not the end and not to be feared, was essentially the same. Awe of the supernatural or divine is archetypal. There is in us all a tendency toward the spiritual— an orientation toward an invisible presence, to something greater than ourselves that cannot be fully known. Spirituality unites us— in silence, in awe, in devotion, and in soul connections.” ~ Jean Shinoda Bolen From: Page 71 … ‘Urgent Message from Mother’

Artwork: ‘Ancient Ways of the Snake Goddess’ by Raine © Inner Voice Art™ This creation was inspired by the rituals and worship of the Ancient Minoan Snake Goddess or Priestess from the Palace of Knossos, Crete, dated 1600 bce. In this aspect she embodies the Fertility and Spirit of the Great Earth Mother from which all life begins and returns. The snakes were worshipped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration and were often believed to be incarnations of the dead. They symbolised immortality in the shedding and renewal of their skins.

#Jean Shinoda Bolen#Urgent Message from Mother#Goddess#eleusinianmysteries#eleusinian#persephone#demeter#eleusis#athens#archetypes#archetypal#ancientgreece#divine#spirituality#divine feminine#sacred feminine#authorsofinstagram#jeanshinodabolen#Raine @ Inner Voice Art#imagika#art#inner voice art#Snake Goddess#Minoan Snake Goddess#Priestess#Palace of Knossos#Knossos#Crete#1600bce#Fertility

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minoan Thera Wallpainting Exhibition: Young Priestess, 17th C. BCE

"The West House Room 5, south-east portal, east door jamb H: 1.51 / W: 0.35 m A young female figure wearing a long robe is depicted as if she is about to enter room 5. Her head is almost entirely shaven (blue) and crowned with a snake-like band; her lips and ears are painted in red. In her left hand, she holds a fire-box which appears to be lit and with her right hand, she adds incense to the fire. The most striking element of this wall-painting is the yellow-reddish saffron colour of her robe. Saffron, as a colouring agent, was used throughout antiquity as a clothing dye. Such garments were normally reserved for people of high status. Saffron was probably derived locally and is an enduring theme and colour throughout the wall-paintings."

-taken from therafoundation

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2020/01/minoan-thera-wallpainting-exhibition_73.html

#minoan#ancient greece#greek#european art#pagan#europe#antiquities#classical art#paganism#art history#santorini#17th century bce

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch the Video on youtube:

youtube

The Sporty & Joyful Life of the Minoans 🏛💖✨🎶

The Minoan Civilization: A Surprisingly Modern Society

The Minoan civilization, which flourished on the island of Crete, is renowned for its advanced and, for its time, unusually liberal society. Although our knowledge of the Minoans is incomplete due to limited written sources and primarily based on archaeological finds, a picture emerges of a culture that, from around 2700 to 1450 BC, exhibited remarkable openness, equality, and joie de vivre.

Equality and Tolerance Modern archaeological and anthropological studies frequently highlight the Minoans' liberal attitudes. Researchers like Nanno Marinatos have examined the religious and social structures of the Minoans and found that their society displayed an unusually high level of gender equality for its time. Women actively participated in public life, possibly held leadership positions as priestesses, and enjoyed similar rights to men in private spheres.

Regarding sexuality, the Minoans also seem to have embraced a tolerant attitude. Artistic depictions of same-sex relationships suggest that such relationships were accepted in Minoan society. While interpretations of these depictions remain debated among scholars, there are numerous indications that the Minoans had a more open stance towards various forms of love and romance, including homoerotic relationships.

Katherine A. Schwab, through her work on Minoan frescoes, has provided insights into the social dynamics of Minoan culture, including possible homoerotic aspects. This, combined with the lack of evidence for strict gender or sexual norms, suggests a society that valued personal freedom and expression.

Cultural and Social Freedom Minoan culture was characterized by its artistic flourishing and a strong preference for beauty and pleasure. The Minoans were masters of fresco painting, ceramics, and architecture. Their palaces, such as the famous Palace of Knossos, were not only political and economic centers but also hubs of art and culture.

The Minoans lived in close connection with nature, as reflected in their vivid frescoes depicting dolphins, lilies, and other natural motifs. Their appreciation for water is evident in their ritual purification and bathing practices, which likely held both religious and social significance.

Festivals, dances, and athletic competitions were integral to Minoan society. These events served not only as entertainment but also as ways to strengthen social bonds and express identity through shared experiences.

Religion and Spirituality Religion played a central role in Minoan life, and their spiritual practices mirrored their liberal values. The Minoan religion was largely matriarchal, with goddesses like the Snake Goddess taking central roles. The emphasis on female deities aligns with the high status of women in Minoan society, symbolizing fertility, protection, and the power of nature.

Rituals and religious ceremonies were opportunities for the community to come together, celebrate, and express their connection with the natural and divine worlds. Often accompanied by music and dance, these rituals emphasized harmony, unity, and a deep respect for the environment.

The Minoan civilization was, in many ways, a progressive and unique culture, whose values of equality, artistic freedom, and spiritual connectedness set it apart from many other ancient societies. Their world reminds us that progressive social structures did not begin in modernity—they existed even in antiquity.

Text supported by GPT-4o, Gemini AI Base images generated with DALL-E, FLUX, enhanced with SD-1.5/SDXL inpainting and composing.

#LiberalCivilizations#AncientEconomics#CulturalDevelopment#GayArt#Queer#ManLovesMan#minoancivilization#lgbt#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ariadne and why the Mycenaeans can fuck right off

Warning: Includes brief mentions of r*pe, cultural destruction, ancient patriarchy reminding us why no woman would ever time-travel more than 5 years into the past if that and a great deal of spite for male historians/public education history/mythology classes.

Possible side effects may include a sudden intense rage for an ancient society equivalent to the innate rage one has for the Romans burning the library of Alexandria, a distinct hatred for ancient men not being able to let anyone have nice things, and a sudden fascination for Minoa.

Usually, I stick to writing imagines and being happy with that. It’s fun! I love it! But every now and again, in an attempt to escape the crushing forces known as reality and responsibilities I’ll put on a few cutscenes from games I’m: A) Too lazy to play B) Too broke to play C) Too unskilled to play D) All of the above

because cutscenes are free and why torture yourself with impossible levels when its free on Youtube?* *In all seriousness please support video games and video game creators, but no shame to those of us who prefer cutscenes to gameplay. A few weeks ago I added the game Hades made by Supergiant to the list because the cutscenes were bomb and the characters are so much fun! Intricate as all hell! Hella cute too but that’s unrelated! Now my pretty little simp patootie is especially a big fan of Dionysus and his gorgeous design so the cutscenes with him are my favorite.

I’m re-watching his cutscenes a few nights ago for fun as background when he has a certain line about Theseus. Don’t quote me on this since my memory is foggy at best but roughly it was: Dionysus: Good job with Theseus. Never cared much for him- what he did to that girl was just horrible.*

*I know that’s not his exact line but this is clearly a rant post fueled by spite and ADD-hyper-focused obsessions with ancient civilizations so let’s not worry too too much about the semantics here.

Now, I like mythology! Personally, I prefer the Norse mythology due to the general lack of very very gross dynamics that several other ancient mythologies seem to include, but I’m decently familiar with Greek mythos. Enough to go - “Why does the God of Wine give a single fuck about the frat bro of Greek heroes being a dick to a woman? Grossness is embedded into the very DNA of all distant relatives of Zeus, a woman being harassed by Zeus or his bastard army is a typical Tuesday in ancient Greece.”

Wikipedia confirms that Ariadne is the only woman in the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, which I kinda knew already so unless Theseus did some f’ed up shit to some other princess of Minos, Dionysus could only be referring to her. Disregarding what I know about Wikipedia and how it can suck you down the rabbit hole of rabbit holes through sheer fury I stupidly clicked the link to Ariadne’s article.

By the time we get to the end of this shitstorm, I will have two separate plotlines for two separate stories based of Ariadne, 2k+ notes (and going) on an ancient civilization prior to a week ago I didn’t know existed and within me there will be a rage towards a different ancient civilization I vaguely recall learning about in high school.

Here’s how this shit went down.

First of all, apparently after Theseus abandoned Ariadne on an island to die (yep! He did that! To the one person who is the only reason he defeated the minotaur! Fuck this guy.) there are multiple storylines where Dionysus takes a single look at Ariadne and falls in love.

“A god falls in love?” you say, aware of how most love stories in Greek mythos can be summed up with Unfortunately, Zeus got horny and Hera is a firm believer in victim blaming. “This poor woman is about to go through hell!” I thought so too! And in one variation of the story, Dionysus does his daddy proud by being an absolute tool to Ariadne. In the majority though? He woos the fuck out of her, and ultimately marries her by consent!

Her consent!

In ancient Greece!

The party dude of the Greek pantheon knows more about consent then his father and modern day frat brothers!

Okay! That’s interesting, so I keep reading.

Ariadne getting hitched to Dionysus is a big deal in Olympus, to the point of getting a crown made of the Aurora Borealis from Aphrodite who is bro-fisting Dionysus, beyond glad she didn’t have to give him the talk about consent. The rest of the gods are pissy especially Hera who doesn’t like Dionysus much since he is the son of Zeus and Semele but they don’t do much. Ariadne ascends to godhood, becomes the goddess of Labyrinths with the snake and bull as her symbol and that’s that on that.

Colorin, colorado, este cuento se acabado. And they lived happily ever after. That’s the end of the post right?

NO! Because curiosity has made me their bitch and there’s more to this calling me.

Also, I was pissed! Still am! Why the fuck-a-doodle-do did I have to learn about the time Poseidon r*ped a priestess instead of the arguably healthiest relationship in the entirety of the pantheon? Why is Persephone and Hades’ story (which has improved since it was first written and I like more modern versions of it, no hate) the only healthy-ish Greek love story I had to learn when Dionysus and Ariadne were right there? The rage of having endured several grade levels of “Zeus got horny and Hera found out” stories in the nightmare of public education led me to keep looking into this.

There’s this wonderful Youtube channel called Overly Sarcastic Productions that I highly recommend that delves a lot into mythology, and I have seen their bombass video about Dionysus and how his godhood has changed since he was potentially first written in a language we comprehend.

Did ya’ll know this man is the heir apparent to Zeus? ‘Cause I didn’t know that!

YEA! Dionysus, man of parties, king of hangovers and inducer of madness, is set to inherit the throne of Olympus! Ariadne didn’t husband up the God of Wine, she husbanded up the Prince of Olympus and heir apparent to the throne! Holy shit! No wonder some of the gods were against her marriage to Dionysus - can you imagine the drama of an ex-mortal woman sitting on the Queen’s throne of Olympus? Hera must have been pissed.

BUT WAIT.

There’s more.

The reason we know Dionysus is a very important god and is possibly even more important than we think is because of a handy-dandy language known as Linear B, otherwise known as the language of the Mycenaeans!

For those of you fortunate enough to have normal hobbies and interests, the Mycenaeans were the beta version of the Greeks. Their written language of Linear B is one of, if not the first recorded instance of a written Indo-European language. This language, having been translated, gives us an interesting look at what the Greek gods were like back in their beta-stages before they fixed the coding and released the pantheon.

Interesting side facts of the Mycenaean Greek gods include:

Poseidon being the head god with an emphasis on his Earthquake aspect, and being much more of a cthonic god in general.

Take that Zeus, for being so gross.

The gods in general being more cthonic, as Mycenaeans were obsessed with cthonic gods (probably due to all the earthquakes and natural disasters in Greece and Crete at that time)

Several of the gods and goddesses that we know being listed, alongside some that we don’t consider as important (Dione)

The first mention of Kore, later Persephone, but no Hades because since a lot of gods were cthonic, there would be no need for one, specific cthonic god to represent the majority of death-related rituals.

That’s not what we’re focusing on though! What we’re focusing on is a specific translated portion of Linear B that we have. One of the translated portions of Linear B that for the life of me I can’t find (someone please help me find it and send the link so I can edit this post) says an interesting phrase. “Honey to the gods. Honey to the Mistress of Labyrinths.”

One more time. “Honey to the gods. Honey to the Mistress of Labyrinths.”

Mistress of Labyrinths.

Now wait a gosh darn minute. Isn’t there a goddess of labyrinths in the Greek mythos? Why yes! Yes there is! Ariadne!

Here’s a question for you. If Ariadne is but a minor god in the pantheon, a wife to a more predominant god, why is it that while all the other gods and goddesses are bunched together in a sentence of praise, the so-called ex-mortal gets a whole-ass sentence to herself singing praises?

And thus, we have arrived to Minoa!

What is Minoa, you ask? Minoa is to Rome what Rome is to us. An old-ass civilization either older than or younger by a hundred years to ancient Egypt. Egypt, that started in 3200 B.C-ish depending on who you ask. That’s old. Old as balls. They were contemporaries to their trading partner, Egypt until 1450 BC-ish. A 2000 year old civilization.

Minoa was founded on the island of Crete, and was by what artifacts we have found a merchant civilization with its central economy centered on the cultivation of saffron and the development of bronze/iron statues of bulls. Most of what we know about them comes from artifacts and frescoes found on Crete that managed to survive everything else I will mention later, but what matters is that we know a few things about them.

Obsessed with marine life for some time, given their pottery.

Had the first palaces in all of Europe, some of them ridiculously big.

Wrote in Linear A and Cretan Hieroglyphs, both still untranslated languages.

Had a ritual involving jumping over a bull, for some reason.

Firm believers in “Suns out, Tits out.”

You’d think I’m kidding on the last one but no! No no no! All the women apparently rocked the tits-out look in Minoa!

^^^^One of many, many Minoan works featuring women giving their titties fresh air. ^^^^

“Wait a second Pinks! What does this have to do with Ariadne being the Mistress of labyrinths?”

Well you see dear wonderful darling, while we know very little about Minoan religion because Mycenaeans (we will get to those bastards in a second), we do know this:

All the religious figures appear to be exclusively women.

The most important figures of their religion seem to be goddesses as there are few artifacts featuring male gods.

Because of the religion, the culture may have been an equal society or even a matriarchy! Historians who are male aren’t sure.

A frankly ridiculous amount of their temples, including the ones in caves in the middle of fuck-all feature labyrinths. A lot of labyrinths!

Their head god is a goddess! Whose temples have labyrinths and whose main symbols are snakes and bulls. Who do we know is a) the mistress of labyrinths and b) is symbolized a lot by snakes and bulls?

ARI-fucking-ADNE THAT’S WHO!

Ariadne didn’t upgrade by marrying the prince of Olympus! Dionysus wifed up possibly the most important goddess in all of Crete and becoming her boy-toy!

I’m not even kidding, most Minoan depictions of the goddess’ consort features a boy/man who cycles through the stages of death. Dionysus himself in several myths goes through the same cycle - life, being crushed, death, rebirth, repeat. Cycles the consort goes through in Minoan legend depictions too!

Okay, that’s great, but what does that have to do with the Mycenaeans? Why do you want to single-handedly go back in time and strangle the beta-Greeks with the nearest belt?

Everything I just said about Ariadne being a Minoan goddess, the Mistress of Labyrinths being hella important on Minoa, is all theoretical. The Mycenaeans are partially to blame for making it theoretical.

Minoa thrived for 2000 years but it had a lot of issues, mostly caused by natural disasters. Towards the end of their civilization (1500 BC-ish), the nearby island of Thera, today known as Santorini, decided to blow up. The island was a hella-active volcano that when erupted, destroyed a lot.

How big was the eruption? Well when Pompeii was wasted by Mt. Vesuvius, the blast was heard from roughly 120 miles away, 200 km.

The blast on Thera was heard from 3000 miles away. 4800 km away.

Fuck me, the environmental effects of the explosion were felt in imperialistic CHINA.

Holy shit that would waste anybody! And it did! Minoa went from being a powerhouse in the Mediterranean to scrambling to recover from losing 40,000 citizens and who knows how many cities. Tsunamis may have followed the blast, further destroying ports which for a navy-powerhouse of an island nation is a bad thing and the theorized temperature drops caused by a cloud of ash lingering for a while would have destroyed crops for the year.

Minoa was fucked.

The Mycenaeans and all their bullshit made it worse.

Up until a few hundred years prior to Thera’s explosion, Minoan artifacts don’t depict much in terms of military power. Why would it? Crete is a natural defense post. Sheer cliffs, high mountains and a few semi-fortified areas would make it pointless to invade. It’s only when the Mycenaeans in all their bullshit decided to attack/compete that Minoa really needed any army to speak of.

Guess who decided to invade while Minoa was reeling from an incredibly shitty year? Mycenaea!

Guess who won?

Also Mycenaea!

Nobody knows how this shit went down though because wouldn’t you know it, the Mycenaeans in all their superiority-complex glory decided to destroy most written accounts about Minoa, a good junk of the temples and culturally eliminated most of Minoan beliefs.

Minoa isn’t even the real name of the civilization! It’s just the name Arthur Evans, the guy who re-motivate interest in Minoan archaeology, gave to the civilization because the writings that would have included the name of the civilization were destroyed.

“That sucks!” Fuck yes that sucks! “What does that have to do with Ariadne though?”

Oh ho ho. Strap in because you’re about to be pissed.

Those of us unfortunate enough to be aware of all the bullshit the Christians pulled on the European pagan belief system are familiar with the concept of cultural, religious destruction. There’s a special name for it I don’t know but if I did I would curse it to be absorbed by the horrendous will of fungi.

An example: Christianity was not the most popular of religions amongst the Vikings. A monotheistic religion that is heavily controlled did not strongly appeal to anyone with a pantheon as rad as the Norse one.

In order to appeal to the Vikings, what monks would do is they would write down traditionally Viking stories which up until that point were orally passed down. Beowulf, the story of the most Viking Viking to have every Vikinged, was one of these first stories.

However! Did these monks write Beowulf as closely to the original oral transcript as possible? Of course not! They took liberties! While Norse features such as trolls and dragons and all sorts of Norse magic occur, there is a lot of Christian features added in.

This happened across all Pagan religions that Christianity came into contact with in Europe. Stories would be altered when written down to be more Christian (this happened to the Greek Pantheon too btw), holidays that were Pagan magically lined up with ones the Vatican just happened to suddenly have. Even names of mythological figures were taken and added onto Christian figure names. Consequently, a lot of pagan religions they did this to got erased over time, with many of their traditions and details being lost forever, and the details we do know being tinted by Christianity.

The Mycenaeans were likely no different.

Minoa and Mycenaea were as culturally opposite as can be. Minoa is theorized to be a matriarchal or equal society*. Mycenaea and most of early Greece absolutely was not. In fact, during early stages of their religion where they believed in reincarnation, the Mycenaeans believed the worst thing to come back as was a woman.

Did you get that? With your options ranging from man to ever single animal on Earth, a woman was ranked as beneath literal animals in Mycenaean society.

Fuck the Mycenaeans.

* This is not to say Minoa was without fault, as a society that is matriarchal or equal can still have rampant issues such as privilege, classism, racism, sexism and more, but when history has a shortage of civilizations that didn’t treat women like shit, you find yourself rooting for them more.

What do you do then, when you take over a society that is very much the opposite of a nightmare of a patriarchy? You fold their beliefs into your own to bait them into yours. Going back to the Linear B line about “Mistress of Labyrinths” that line would/could have been an early tactic of incorporating Minoan belief into Mycenaean belief. Other goddesses and gods were made into aspects of Mycenaean gods. Bristomartis, the Minoan goddess of the hunt, would become Artmeis. Velchanos, a god of the sky, would become Zeus.

With more time, the religion shifted more into Mycenaean and eventually into ancient Greece as we know it. Through trade other gods and goddesses would continue to shift and change, some being straight up imported (Aphrodite for example). Dionysus himself changed a lot too, going from a God representing freedom and attracting slaves, women and those with limited power into his cult, to a God of parties for the wealthy.

Theseus and the Minotaur was a myth likely based on a Mycenaean myth based on a Minoan myth that changes Ariadne from an important, possibly the important goddess of an ancient religion and relegates her to a side character in a pantheon so vast that she would be lost within it.

All of this brings us to today. Today, where as soon as work ended I spent most of the day, as well as the past two days, looking up everything I can on Minoan civilization and added it to my notes. Spite is fueling me to write two possible different stories for two different fandoms where Minoa dunks of Mycenaea and it is giving me life. Expect an update within the next two weeks folks as I lose control of my writing life once more.

In summary: Ariadne deserves more respect, fuck the public education system for skipping over the good parts of Greek mythology instead of the r*pey as shit parts, the Mycenaeans can eat my shorts, and a world were Minoa became the predominant power instead of Greece would be an amazing world to live in.

Thank you for coming to my TedTalk. Pink out.

#minoa#minoan#crete#ancient history#ariadne#mycenaea#mycenaean#I hate#HATE#HATE HATE HATE the Greeks so much#homer is a dick#So much spite and curiosity went into this#if I ever get a time machine I will travel to the first years of Mycenaea for the express purpose of burning it to the ground before#they get a chance#the opportunity#to look at Minoa wrong

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oracle

An oracle is a person or agency considered to provide wise and insightful counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. As such, it is a form of divination.

Description

The word oracle comes from the Latin verb ōrāre, "to speak" and properly refers to the priest or priestess uttering the prediction. In extended use, oracle may also refer to the site of the oracle, and to the oracular utterances themselves, called khrēsmē 'tresme' (χρησμοί) in Greek.

Oracles were thought to be portals through which the gods spoke directly to people. In this sense, they were different from seers (manteis, μάντεις) who interpreted signs sent by the gods through bird signs, animal entrails, and other various methods.

The most important oracles of Greek antiquity were Pythia (priestess to Apollo at Delphi), and the oracle of Dione and Zeus at Dodona in Epirus. Other oracles of Apollo were located at Didyma and Mallus on the coast of Anatolia, at Corinth and Bassae in the Peloponnese, and at the islands of Delos and Aegina in the Aegean Sea.

The Sibylline Oracles are a collection of oracular utterances written in Greek hexameters ascribed to the Sibyls, prophetesses who uttered divine revelations in frenzied states.

Origins

Walter Burkert observes that "Frenzied women from whose lips the God speaks" are recorded in the Near East as in Mari in the second millennium BC and in Assyria in the first millennium BC. In Egypt, the goddess Wadjet (eye of the moon) was depicted as a snake-headed woman or a woman with two snake-heads. Her oracle was in the renowned temple in Per-Wadjet (Greek name Buto). The oracle of Wadjet may have been the source for the oracular tradition which spread from Egypt to Greece. Evans linked Wadjet with the "Minoan Snake Goddess".

At the oracle of Dodona she is called Diōnē (the feminine form of Diós, genitive of Zeus; or of dīos, "godly", literally "heavenly"), who represents the earth-fertile soil, probably the chief female goddess of the proto-Indo-European pantheon[citation needed]. Python, daughter (or son) of Gaia was the earth dragon of Delphi represented as a serpent and became the chthonic deity, enemy of Apollo, who slew her and possessed the oracle.

Read more

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

why don’t you pray to the Minoan Snake Goddess Statue Cretan Snake Goddess Sculpture and maybe you’ll calm down

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A brief moment of vaguely uncomfortable silence is appropriate, and Mulder's mind goes on a free-associating rampage. Spellcasting Scully, a fine small finger, no, two, drawing practiced symbols in goofer dust, finishing a glyph with a sideways stroke of her thumb. A Minoan snake priestess, blue-eyed like no Cretan woman would be, red-haired, bare-breasted and sea-powered.

—— “Weret-Hekau” Khyber

#this is a call out for myself#cause look at this shit#Khyber had me and still has me chained#msr#x files#x files fic#frost reads fic#words

1 note

·

View note

Text

Around 2,200 BC the Minoan culture on the isle of Crete develops into the Minoan civilisation they were known to revere bulls and the myth of the Minotaur and labyrinth would later develop on this island they also had a humanoid bee Goddess later known as the “Delphic Bee” who was originally known as the “pure mother bee” or “mistress” and had priestesses called “Melissa” meaning “Bee”, the connection between bulls and bees here may connect to the Egyptian Apis bulls mythology. The Minoans also had a Goddess depicted holding two snakes with a sacral knot of cord across her breasts she was a Goddess of the houshold and may have been an earth Goddess, Goddess of poisons, remedies, snakes and/or animals and was known to have some relation to silence as a religious practice perhaps indicating secrets and mysteries. Similar designs were found in Egypt. The Minoans also venerated double-axes called “Labrys” which may have some relivance to the Minoan “Labyrinth” these were likely weapons of war or ritual tools of sacrifice and may have been a symbol of the mother Goddess. The Knossos was also built on Crete and is thought to be Europes oldest city before being abandoned some time between 1,380-1,100 BC.

9 notes

·

View notes