#ming red paint

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

P'li ✨✨(A.K.A Sparky Sparky Boom Ma'am)

I did Ming-Hua, so naturally P'li was next!!

My Ming-Hua art didn't get many notes, so maybe I have to play the I'm 14 years old card cause I really want some notes ahahaha

Here's my Ming-Hua one btw!!

#young artist#avatar the last airbender#artists on tumblr#art#atla fanart#avatar fandom#original art#beginner artist#digital art#digital illustration#digital drawing#digital painting#p'li#ming hua#red lotus#young red lotus#lok#avatar: tlok#avatar fanart#lok fanart#avatar villains#combustion#14 year old#atla art#korra#tlok fanart#tlok#legend of korra#the legend of korra#fire

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hu Ming - Red, red wine 2010

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wait... the war's over, Xianle has fallen and Xie Lian is called back to the heavens, and almost-certainly-Hong-er is getting into fights with the people burning down Xie Lian's temples? Huh. I thought for sure he died on the battlefield as a soldier...

#Me Talking#tian guan ci fu#heaven official's blessing#TGCF liveblogging#I am only *almost* certain this is Hong-er#because frequently this boy's *eyes* (plural) are mentioned and no mention of either being red#nor any mention of bandages to the face or even of his right eye being swollen shut#(there are in fact several mentions of his 'eyes' doing things that would mean both are open)#and I REALLY thought Hong-er died in battle... I have seen so many references or portrayals in fic of Hong-er dying on the battlefield#But on the other hand there's absolutely no way this isn't Hong-er is there?#Defending Xie Lian's temples. Painting Xie Lian for the temple. That interaction mirroring the one at the little shrine before the war.#The many things the kid said that DEFINITELY Hong-er or Hua Cheng or Wu Ming would say. 'You're the only real god' especially#The accompanying illustration 100% looks like Hong-er (it even has what might be some bandages under his hair and the right eye closed)#I'm so confused... I suppose I'll have to wait until either book four or the Cave of a Thousand Gods clears all this up

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#manor red#manor red paint#manor red colorbond#ming red colour#manor red roof#red roof paint#roof paint red#colorbond manor red#red colorbond roof#manor red colorbond roof#roof paint colours#what colours go with manor red#manor red colour#red roof colour#colorbond manor red roof#red roofing#roof painting#roofing paint colors#ming red asian paints#painted roof#ming red paint#cream bg#dulux roof paint colours#apex ming red#heritage red#mink red colour#dulux manor red#manor red spray paint#asian paint roof tiles colour#maroon roof paint

0 notes

Text

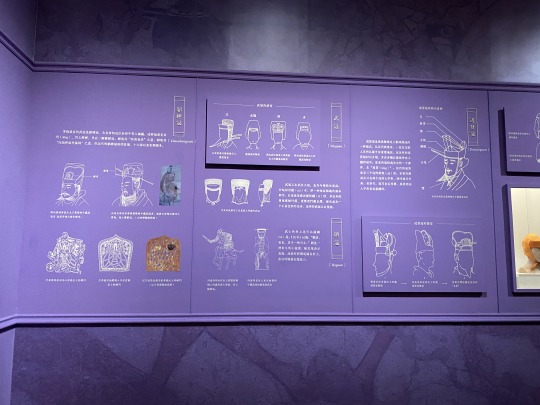

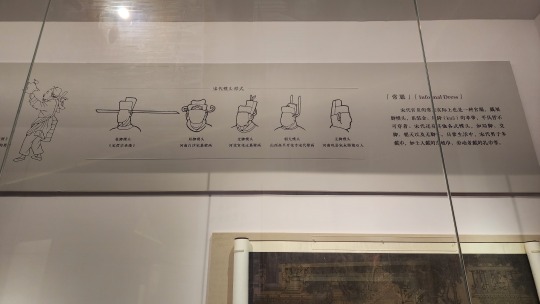

April 20, Beijing, China, National Museum of China/中国国家博物馆 (Part 3 – Chinese Historical Fashion Exhibition):

Another cool exhibition that I visited while at the museum, showcasing popular fashion from different dynasties, historical artifacts, and some other relevant artifacts that gave a glimpse into the fashion of different dynasties. What's even cooler is that you can visit this exhibition virtually! (the site is in Chinese but I highly recommend it to everyone, there's so much more to the exhibition than the pictures I post here) Note that this exhibition does not only include historical hanfu, but also historical fashion of the 少数民族 that ruled some of the dynasties. This post will be pre-Ming fashion, and next post will be Ming and Qing era fashion. The reason is because Ming and Qing dynasties are the two most recent dynasties, so there are a lot of surviving artifacts from these two dynasties, which means there are 30+ pictures total and I couldn't fit them all into a single post.

First is a recreation of Han-era (202 BC - 220 AD) hanfu. The woman on the left is wearing a one-piece robe called a qujushenyi/曲裾深衣. The man on the right is wearing the outfit characteristic of Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD) civil officials, a combo of jinxianguan/进贤冠 hat and zaochaofu/皂朝服 clothing (皂 here means the color black, as in the word "青红皂白", or "blue and red, black and white"):

Left: model of a Han-era magpie tail cap/queweiguan/鹊尾冠 (you can see the influence of these Han-era men’s hats on the outfits of male characters in modern xianxia art). Right: recreation of a Han-era bian/弁 hat (the headscarf-like piece tied beneath the chin):

Line drawings of different hats worn by different types of officials based on artifacts and murals. The center and left sections are different hats of military officials (wuguan/武官 in Chinese), and the right section is different hat styles of civil officials (wenguan/文官 in Chinese).

Jumping back, this is a Warring States period (476 - 221 BC) iron daigou/带钩 inlaid with gold and jade and decorated with dragons. Daigou are basically belt buckles where the flat end is attached to one end of the belt, and the hook will hook into slits in the other end of the belt, so this is an extra fancy belt buckle:

On to Tang-era (618 - 907 AD) hanfu. From the left to right these are: the regular outfit of early Tang dynasty officials (color varies by rank, red is worn by fourth and fifth rank officials), the outfit of a female servant in early to mid Tang era, the ceremonial outfit of a Tang dynasty emperor, and the outfit of noblewomen in late Tang to Five Dynasties era (907 - 960 AD):

Song-era hanfu (front two) and Yuan-era Mongolian fashion (back two). Front left is the formal attire of Southern Song dynasty (1127 - 1279) civil officials (color varies by rank, red is worn by fourth and fifth rank officials), and front right is the regular outfit of women in Southern Song dynasty. Back left is the formal attire of Mongolian noblewomen in Yuan dynasty (1271 - 1368), and back right is the regular outfit of Mongolian men in Yuan dynasty.

Replicas of painted clay sculptures of women from Northern Song dynasty (960 - 1127), the original sculptures are in Hall of the Holy Mother/圣母殿 of Jinci Temple/晋祠 in Shanxi province:

By the way, in the case of Song dynasty, the descriptor "northern" and "southern" basically indicate time periods within Song dynasty (you can refer to the beginning of this post where I explain this in more detail).

And line drawing diagrams of different styles of futou/幞头 hats in Song dynasty based on paintings, murals, and other artifacts:

#2024 china#beijing#china#national museum of china#historical fashion#historical clothing#chinese historical fashion#hanfu#mongolian historical fashion#fashion history#chinese history#chinese culture#history#culture

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

So something that caught my attention with the Dragon symbolism stuff with the world nobles vs how it’a used in the RA led me down a rabbit hole that I found interesting enough to share.

So the whole thing stems from two instances of dragon claws being depicted in One Piece.

So! First we have the Celestial Dragon Claw, four clawed, used as branding to mark word noble “property”. Then we have the Dragon Claw Fist, three clawed, a fighting style that we can assume was developed by the RA using the Finger Pistol of the Six Powers as a base.

The difference here is the number of claws, which is what lead me down the rabbit hole in the first place.

The consensus is that the claw number of a depicted dragon is actually a class indicator. Bear in mind that these observations stem from Chinese folklore and its place in Imperial Chinese law, so it might not hold water. And as always do correct me if I’m off in any of these points.

The number of claws and the colorations of dragons in Imperial China was an extremely important thing, and misrepresentations of these could quite literally get you and others executed for acts of treason.

Five clawed yellow or gold (or red during the Ming Dynasty) dragons are a symbol of imperial power for the emperor alone to use. It was illegal for nobles and civilians to wear anything depicting a five-clawed yellow or gold dragon in Imperial China. It was considered- as stated above- an act of treason, and offenders (and their families) could be imprisoned or executed for the crime.

Four clawed dragons are a symbol of nobility. Lesser in the hierarchy than the imperial dragon, but still a mark of high status. It was illegal for civilians to wear depictions of four-clawed dragons. Again, a treasonous act punishable by death or imprisonment under Imperial law.

Civilians could depict dragons with three claws. This was allowed.

So, we can make an assumption here that through these observations, the RA use the three clawed dragon as symbolic of the class warfare that is happening in the One Piece world. But there is another thing!!!

There are these things called Dragon Dance Competitions, where a nine-segmented dragon puppet is manipulated by a team of dancers and musicians to have the dragon chase a pearl- a symbol of wisdom- across the allocated space. These are very interesting to watch, and I highly recommend giving one a watch, since there are plenty of them to see on YouTube. Do take care if you are photosensitive or sound sensitive, as they are bright and loud.

A tradition for these competitions and others (such as lion dances and dragon boat races) is called an “eye dotting ceremony”, which happens at the beginning of the competition. An authorized party comes by to paint the pupils on a dragon to symbolically awaken or- relevant to this post- empower it.

The Celestial Dragon’s Claw is a symbol nobility, and likely has high amounts of regulation on how it can and cannot be used, with infractions on those regulations met with imprisonment at best, and cipher pol or a buster call at worst. It would be highly guarded, and was used to brand people to mark them as property, as we know.

The dragon depicted in the introduction to the Dragon Claw Fist that Sabo utilizes? Three claws, no pupils. It is an unempowered civilian dragon- a weakling by dragon standards- and it is beating the shit out of a World Government official.

Class warfare symbolism. Revolutionary symbolism.

#one piece#meta#does this count as meta?#revolutionary sabo#revolutionary army#celestial dragons#dragon symbolism#cw slavery

111 notes

·

View notes

Note

Shen Yuan transmigrates into a doll

His body felt strangely stiff. He didn’t know if he was hot or cold, his skin felt like someone had injected the kind of anaesthesia that dentists use, it was there yet he could only feel it passively.

He opened his eyes looking around…a workshop? Was he sitting on a table? Sunlight gleamed through the west window, golden rays making everything seem warmer yet Shen Yuan did not feel warm. He did not feel quite cold, either. It was…strange.

He looked down at himself. Bright snow white and glossy, with paintings of phthalo blue flowers, like the patterns on fine Ming dynasty china. His limbs were divided into different pieces, each held together by a ball to represent a joint. He moved his arms tentatively, marvelling at the craftsmanship, the fact that this was his body had not quite registered to him yet.

Porcelain…he was made of porcelain.

“Goodness.” A voice spoke in front of him.

Shen Yuan slowly looked up, treating his new body as carefully as one would a priceless tea set. The man was wearing a worker’s clothes, covered in dried clay and paint. He was tall, his shoulders were broad, he had a striking poise. Shen Yuan felt a bit breathless.

The man’s hair was swept back and pinned on the top of his head, long waves of brown cascading down his back, leaving his face in full view. Between his brows was a red mark like a flame…a huadian? Black eyes, twinkling with some sort of cold light, like the sun peeking through clouds on a snowy winter day. They were wide, staring at Shen Yuan like he was a marvel, and well, the man was undeniably handsome.

Shen Yuan’s feet dangled above the floor, so he slowly kicked them, like a child, as the man— the craftsman, he concluded, his creator— moved towards him with slow, careful steps.

How should Shen Yuan address him? Calling him father seemed…wrong.

The man had come close enough that Shen Yuan could count his lashes, which were long and curved. The man looked at him in awe, the doll would have blushed if he had any blood to do so. The craftsman caressed his face and Shen Yuan leaned into the touch on instinct. He was delighted to learn he could feel the man’s hand as it stroked his cheek. How was that even possible? Did the porcelain skin have some kind of magic receptor? He could almost feel the man’s warmth.

“You can move,” The man said, and oh, was he not supposed to? He tilted his head in confusion, “Amazing, can you hear me?”

Shen Yuan nodded.

The man let out an incredulous sigh and smiled, holding Shen Yuan’s face with his hands, “I am Luo Binghe, I...”

Shen Yuan nodded once more, trying to signal that he understood. His lips seemed stuck in a smile, but he reckoned he could move them if he wanted to. He decided to stay silent.

Luo Binghe looked starstruck.

Shen Yuan looked down, deciding to try and walk with his new legs. He slowly slipped off the table, making Luo Binghe yelp and try to help hold him up. Shen Yuan leaned into him, legs wobbly as he learned to use them. Luo Binghe held him like some sort of treasure. He decided he could get used to this life, with this sweet man by his side.

———

I got way too excited for this prompt. Porcelain Doll Shen Yuan shall live in my head rent free from now on.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

OVERSTIMULATING KAVEH !! [ MNDI ] [ 18+ ]

✿ [ WARNING(S) :: dom!read. sub!kaveh. overstimulation duhh. bondage. blindfold. blowjob. handjob. dacryphilia. throatpie. gender not specified. ]

kaveh moving into your house was one of the best things that happened to the both of you. waking up next to each other, cooking together and whatnot, but what was even better was the audible moans from your shared bedroom…NSFW UNDER THE CUT

kaveh found himself tied by the wrists to your bed, crawling over him with a silky blindfold in one hand and the other crawling under his shirt, “i’m gonna blindfold you now kaveh, alright?”, he shyly nods, closing his eyes for you in which you swiftly wrap the blindfold over his lashes. soft palms find their way to his pants, unzipping them— surprisingly he’s already hard; now another thing about kaveh is that he is surprisingly sensitive, just a lil grinding on his pants and the precum starts leaking.

you adjust yourself between his knees, kissing his abs and v-line, working your way down just until your lips peck the base of his cock, wrapping your hand around the length and slowly picking up a pace— kavehs reactions are so cute~, “f-faster..please~ ngh”, so shy! but alas, you oblige and keep stroking faster and faster, his hips bucking up to match your rhythm. “g-gonna cum- c-cum..ming!~”, he whines, hips lifting as his cum shoots out, cocktip turning a pretty pink colour. he was catching his breathe until…you started moving again, but this time with your tongue swirling on his slit.

“h-hey! why are you— i-i just- aaah~ mmnggh!~”, his words falter, his back arches and he attempts to close his legs out of instinct however you force them open, fuck; he’s so sensitive, it hurts but it feels so good. his second orgasm catches him by surprise, when you suddenly squeeze your hand tightly at his base; the cum spurting into your mouth; painting a milky white inside, “anghh! oohh-mm! cumming!~”, kaveh squeals; thinking this was his last orgasm…hehe he was wrong <3

now the third really took a toll on him, tears staining through the silk and his wrists tugging at the rope; body shivering and squirming; he throws his head back and completely shuts his legs, you engulf his whole cock, the tip hitting the back of your throat, and when your throat contracts; “hnn-aaaahhh!!! o-ohh archons— i-i can’t! m’too sensitive!~”, he mewls each time you bob your head up n down with loud, “ah! ah! ah!”. to think the best architect of Sumeru would be in such a state, chest heaving up and down. “h-hey! i-i feel like i’m gonna c-cum- cu- ahh!~ cumming!~ cummingcummingcumming~”, you’re pretty sure the neighbours could hear the moan that emerged from him next…your lips meet his pelvis and he cums right in your throat, lucky enough your reflexes haven’t caused you to gag.

you swallow all of his cum, and smile once you look back up at him, his whole body’s gone limp, his whole cock a furious red, nipples perking up, dick softening but twitching all the while…cutie kaveh <33

#genshin drabbles#genshin headcanons#genshin impact drabbles#genshin impact x you#genshin x you#genshin impact headcanons#genshin x reader#genshin impact x reader#genshin impact smut#genshin smut#kaveh x reader#kaveh x gender neutral reader#kaveh x y/n#kaveh x you#sub kaveh#kaveh smut#kaveh x reader smut#kaveh imagines#genshin kaveh

908 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Song Dynasty(960–1279 AD)Emperor Traditional Ceremonies Clothing Hanfu in Cdrama <清平乐/Serenade of Peaceful Joy>

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

Posthumous Portrait of Emperor Zhaowu of Song Dynasty wearing TongTianGuanFu(通天冠服).

Palace Portrait of Emperor Shenzong of Song Dynasty wearing TongTianGuanFu(通天冠服).

The emperor wearing wearing TongTianGuanFu(通天冠服) in the Song Dynasty painting "Book of a girl's filial piety/女孝经图"

【History Note About Tongtianguanfu (Chinese: 通天冠服)】

Tongtianguanfu (Chinese: 通天冠服) is a form of court attire in hanfu which was worn by the Emperor during the Song dynasty on very important occasions, such as grand court sessions and during major title-granting ceremonies. The attire traces its origin from the Han Dynasty. It was also worn in the Jin dynasty Emperors when the apparel system of the Song dynasty was imitated and formed their own carriages and apparel system,and in the Ming dynasty. The tongtianguanfu was composed of a red outer robe, a white inner robe, a bixi, and a guan called tongtianguan(tongtian crown), and a neck accessory called fangxin quling.

Among the Tongtianguanfu (Chinese: 通天冠服), the "Tongtian crown" which wear by emperor has a long history, and has been recorded as early as the Han Dynasty(202 BC –220 AD) in "Book of the Later Han·Yufu Zhixia/后汉书·舆服志下":

“通天冠,高九寸,正竖,顶少邪(斜)却,乃直下为铁卷梁,前有山、展筒、为述,乘舆所常服。”

In the Han Dynasty, when all the officials paid their congratulations on the Zhēngyuè/正月 (the first month of the year in the Chinese calendar), the emperor would wear the "Tongtian crown". According to the Tongtian Crown, it existed in all dynasties from the Qin to the Ming Dynasty (except the Yuan Dynasty), and was abolished in the Qing Dynasty.

And the Tongtianguanfu (Chinese: 通天冠服) of the Han Chinese dynasties in China have gone through a certain amount of evolution.

For reference:

Han Dynasty(202 BC –220 AD) Tongtian crown/通天冠

The earliest form of Tongtian crown that can be seen so far comes from the Han Dynasty stone carvings.

The Tongtian Crown of this period has a similar structure to the Jinxian Crown(进贤冠) of the ministers.

Wei and Jin Dynasties-Southern and Northern Dynasties Tongtian crown/通天冠

Tang dynasty (618–907) Tongtian crown/通天冠

Ming dynasty (1368-1644) Tongtian crown/通天冠

The Tongtian crown of the Ming Dynasty was briefly used in the early years of Hongwu(the early ming dynasty), but was soon completely replaced by Pi Bian(皮弁), and its appearance was much lower-key than that of the Song Dynasty

after replace by Pi Bian crown(皮弁):

This Pi Bian crown belonged to King Luhuang of the Ming Dynasty, so it only has 9 colorful beads, while the emperor's Pi Bian crown has 12 colorful beads on it.

※The Yuan Dynasty established by the Mongols and the Qing Dynasty established by the Manchus did not use this kind of crown and clothing※

#chinese hanfu#Song Dynasty(960–1279 AD)#hanfu#chinese traditional clothing#Ceremonies Clothing#Tongtianguanfu (Chinese: 通天冠服)#hanfu accessories#hanfu history#chinese#china#hanfu_challenge#historical fashion#Serenade of Peaceful Joy#清平乐#漢服#汉服#中華風#Emperor#crown#hanfu man

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nine-headed hermit": the early history of Zhong Kui (and his sister)

Gong Kai's painting Zhongshan Going on Excursion, showing Zhong Kui, his sister and various demons during a journey (wikimedia commons) Zhong Kui is probably one of the most recognizable figures from Chinese mythology today and continues to star in novels, movies and other works. However, his modern image largely depends on sources the Ming and Qing periods. In this article, I’ll attempt to instead shed some light on some lesser known aspects of his earlier history. You will be able to learn why he was called a “nine headed hermit” despite having only one head, what he had to do with foxes, when his sister was portrayed as an exorcist like him, and more. As a bonus, I’ve included a brief summary of Zhong Kui’s reception in medieval Japan.

The earliest history of Zhong Kui

Zhong Kui’s history goes all the way back to the Zhou period (most of the first millennium BCE). A homophone of his name (鍾馗), zhongkui (終葵; also zhongzui, 終椎) at the time referred to a type of ritual mallet used to expel demons. During the Six Dynasties period first cases of this term (now written as 鍾馗 ori 鍾葵) being used as a personal name start to pop up. The purpose was most likely to confer the protection granted by such objects to a child just through their name. Numerous cases are attested, and it doesn’t seem the bearers of the moniker Zhong Kui can be distinguished by a specific origin, social class or even gender. The earliest possible reference to a specific supernatural being named Zhong Kui comes from the Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing (太���洞淵神咒經; “Scripture of the Divine Incantations of the Abyssal Caverns of the Most High”), a Daoist work possibly composed as early as in the fourth century. The oldest surviving copy of the passage concerning Zhong Kui has been identified in a copy from Dunhuang dated to 664. He appears in it as an assistant of king Wu of Zhou and Confucius (sic) who helps them subjugate ghosts and disease demons. It is not impossible that to the compilers of Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing Zhong Kui was only a stand-in for an exorcist, though, not a single well defined figure. There’s an eyewitness account of such specialists dressing up in leopard skins, painting their faces red and announcing they are Zhong Kui in another, slightly newer Dunhuang text. It specifies that many Zhong Kui exist, and that they answer to the “General of Five Paths”, an originally apocryphal Buddhist figure eventually canonized as one of the kings of hell (you can find an excellent article about him here). In any case, regardless of the clear evidence for ambiguous use of the term in earlier times, it is agreed Zhong Kui became a well defined figure by the end of the Tang period. That’s also when legends about his origin started to circulate.

The legend of Zhong Kui

A typical depiction of Zhong Kui as a Tang period official by the Qing period artist Lü Xue (wikimedia commons)

According to the most popular version of Zhong Kui’s origin story, he was a scholar from the Zhongnan Mountains who lived during the reign of Gaozu of Tang (reigned 618-626). He took part either in the imperial examination or the imperial military examination (that’s an ahistorical detail - it was established by Wu Zetian in 702), but failed. This detail is not elaborated upon further in early accounts, but by the Ming period it was attributed not to lack of skill but rather to prejudice against Zhong Kui’s physical appearance (he is fairly consistently described as dark-skinned, unusually tall, with a bulbous head and excessive facial hair). It’s possible that this new backstory was based in part on experiences of real officials of foreign origin, whose appearance was sometimes mocked by their peers, as already documented in Tang sources. Another possibility is that the descriptions were meant to be exaggerated to the point of making him resemble a demon, though. Either way, out of despair caused by failure Zjong Kui committed suicide by smashing his head against the steps leading to the imperial palace. However, since in his final words he swore to protect the emperor and his realm, he didn’t return as a vengeful ghost, but rather as a queller of malevolent supernatural entities. Alternatively, he took this role out of gratitude for Gaozu, who was saddened by his death and organized the burial worthy of an honored official for him. Note that in later plays which often serve as the basis for modern adaptations, the burial is typically arranged by a certain Du Ping (杜平), a friend of Zhong Kui from back home. Apparently a version in which the kings of hell are so impressed by Zhong Kui that they decide to make him the king of the ghosts also exists, though I was unable to track down its original source. In any case, he is associated with Mount Fengdu - one of the terms referring to the realm of the dead - in a poem by Song Wu (宋无; 1260–1340) already. He, or at least generic clerk figures based on his iconography, also sometimes appear in Song period paintings of the Ten Kings.

Several Zhong Kui-like clerks from a depiction of hell in Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation (wikimedia commons)

According to Shih-shan Huang a single example of such a figure has even been identified in a Manichaean context, specifically in the scroll Sermon on Mani’s Teaching on Salvation.

Manichaean curiosities aside, supposedly the first person to be aided by Zhong Kui was emperor Xuanzong of Tang. At some point he fell gravely ill. In a dream, he saw a demon who attempted to steal a flute which was one of his most prized possessions. However, the attempt was foiled by a fearsome giant, who dealt with the thief rather brutally, poking out one of his eyes and then devouring him. After completing this act of demon quelling, he explained that he is Zhong Kui, and how he came to fulfill his current role. After waking up, Xuanzong felt healthy again. He was so impressed he commissioned Wu Daozi, arguably the most famous artist in China at the time, to prepare a painting of Zhong Kui which could be used as a talisman against any further supernatural issues. Supposedly it left quite the impression on the general populace, and soon numerous images of Zhong Kui started to be distributed as talismans. There is definitely a kernel of truth to this part of the legend, as eyewitness accounts of Wu Daozi’s painting exist, but the work itself is lost. As a side note, it’s worth pointing out the flute thief demon, despite meeting a gruesome end here, enjoyed a literary afterlife of his own. A certain Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳), the author of a colophon on one of the earliest surviving Zhong Kui paintings, suggests that the (in)famous rebel An Lushan might have been a reincarnation of this specific entity. While I am not aware of any other attempts at providing him with a backstory, in Ming period retellings of the legend, he received a name, Xu Hao (虛耗).

Zhong Kui’s later career

Zhong Kui’s popularity grew after the Tang period, and he arguably eclipsed figures such as the fangxiang (方相) or the baize (白沢) as the demon queller par excellence. Legends about his origin and his first notable act of demon quelling which I summarized above spread far and wide during the reign of the Song dynasty. After becoming a well defined figure, Zhong Kui came to be most commonly classified as a ghost (鬼; gui). In texts from the Song and Yuan periods he is often labeled more specifically as a “big ghost” (大鬼, dagui) or “ghost hero” (鬼雄, guixiong). However, his popularity effectively made him a god in popular imagination, and as a matter of fact he is referred to as such. His divinity is not exactly conventional, though. This topic is addressed in Fu Lu Shou Xianguan Qinghui 福祿壽仙官慶會 (The Immortal Officials of Happiness, Wealth and Longevity Gather in Celebration) by the Ming playwright Zhu Youdun (朱有燉; 1379-1435). Zhong Kui says himself that unlike his peers, he has no festival to call his own, and receives no regular offerings - and yet, he still vanquishes malicious entities on behalf of humans as long as talismans showing him continue to be distributed.

Interestingly, despite his long career in texts, no images of Zhong Kui older than the thirteenth century are known. This is mostly a matter of selective preservation, though - we know that depictions of him existed as early as in the ninth century, and that they were mass produced, presumably as woodblock prints, in the tenth. However, he didn’t necessarily look similar to his modern depictions. He actually only came to be depicted as a Tang scholar in the Song period. It seems earlier his costume might have varied. One thing which seemingly remained consistent when it comes to Zhong Kui’s appearance is his facial hair. This feature is even emphasized in many of his epithets, such as “Old Beard” (老髯, Lao Ran), “Bearded Elder” (髯翁, Ran Wong) or “Bearded Lord” (髯君, Ran Jun). It’s possible that this was initially a way to highlight his vitality and his opposition to disease-causing demons. Tang and Song sources indicate the state of facial hair could be viewed as an indicator of health. There’s even a handful of peculiar anecdotes about certain emperors, like Taizong of Tang or Renzong of Song, believing their facial hair has supernatural healing powers and offering ailing courtiers concoctions in which it was one of the ingredients. There’s no evidence Zhong Kui’s hair was ever believed to serve a similar purpose, though. Not all of Zhong Kui’s titles revolve around his beard, though. An interesting example is “Nine-Headed Hermit” (九首山人). The intent isn’t to imply he has nine heads, it’s a multilayered pun instead. The character 馗 in Zhong Kui’s name is a combination of 九, “nine”, and 首, “head”. Referring to him as a “hermit”, literally “man of the mountain”, is likely supposed to show that he traverses areas traditionally believed to be inhabited by demons.

The nine-headed snake Xiangliu (wikimedia commons)

Chun-Yi Tsai suggests that this title also highlights Zhong Kui’s physical prowess by implicitly evoking “a nine-headed serpent known for its tremendous strength in Guideways through Mountains and Seas” (presumably Xiangliu).

Zhong Kui’s strength lets him punish his enemies in various unexpectedly creative ways. The earliest sources already mention he could grind vanquished demons in a mill, for instance. References to eating them are particularly common. Depending on the source, Zhong Kui might simply devour them whole, hunt and prepare them like game animals, chop them up to pickle them, mince them to prepare meat snacks, squeeze them to make juice and wine, and so on. Such comedically gruesome descriptions are generally limited to textual sources, since violence was rarely depicted in other mediums, even in relation to military topics. Wu Daozi’s lost painting was apparently one of the exceptions, as according to a tenth century description it showed Zhong Kui gouging out the eyes of the captured demon.

Zhong Kui’s sister and other assistants

While Zhong Kui is often depicted in the company of nondescript demons, there are relatively few recurring figures associated with him. The main exception is his sister. The Song period painter Gong Kai (龔開) and his contemporary Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳) simply refer to her as Amei (阿妹), literally “younger sister”, though here it’s apparently a personal name, following Chun-yi Tsai’s interpretation. Her origin is unknown, and she is not present in any of the early variants of the legend.

Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (wikimedia commons)

Today Zhong Kui’s sister is known chiefly from works of art in various mediums which can be broadly subsumed under the label “Zhong Kui marrying off his sister” (鍾馗嫁妹, Zhong Kui jiamei) which proliferated through the Ming and Qing periods. This label is sometimes applied to earlier paintings too, for example Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (鍾馗嫁妹圖, Zhong Kui jiamei tu) is the conventional modern title of a scroll attributed to the poorly known painter Yan Geng (顏庚). A colophon from the Ming period describing this work calls the figure presumed to be Zhong Kui’s sister Ayi (阿姨; an informal way to refer a maternal aunt) as opposed to Amei. Chun-yi Tsai states it is not impossible that the woman is supposed to be Zhong Kui’s wife, rather than his sister, though. The painting can be dated to the Yuan period, and there is no evidence for the story of Zhong Kui marrying off his sister before the Ming plays - granted, it is not impossible that it was already in circulation earlier. Still, other paintings showing Zhong Kui marrying off his sister only date to the Qing period. Additionally, the procession might be a parody of paintings showing rural marriages or couples moving to a new house.

While as far as I am aware this eventually went out of fashion, in early sources Zhong Kui’s sister could be portrayed as an exorcist herself. An example can be found in one of the sermons of the Chan monk Yuanwu (圓悟; 1063–1135), in which he states that celebrations on the “Double Fifth” (端午節, duanwu jie) - the fifth day of the fifth month - involved a dance of “Zhong Kui and his little sister”. A reference to performers dressed up as the pair (as well as kings of hell, gods of soil and stove, various warrior deities and more) has alsobeen identified in an account of celebrations in Kaifeng from the end of the reign of the Northern Song dynasty.

Similar evidence can be found in art too. For example, Zheng Yuanyou (鄭元祐; 1292-1364) in a poem inspired by a painting titled Zhong Kui’s Sister (馗妹圖; as far as I am aware, this work has not been identified) states that she travels alongside her brother, that she’s armed with a sword, and that demons fear her. A related portrayal of her is known from a critical review of the works of Si Yizhen (姒頤真), a Song dynasty painter. According to Gong Kai, in one of his paintings she is shown in tattered (or unbuttoned - the term used, 披襟, can mean both) clothes, and chases away a boar attacking her brother. He was evidently not fond of this innovation, and criticizes it as “vulgar” and inappropriate. It needs to be stressed that Gong Kai’s displeasure wasn’t necessarily tied to presenting Zhong Kui’s sister as a demon queller, though. In fact, he is actually the author of the most famous work portraying her in this role.

Gong Kai's take on Zhong Kui's sister and her attendants (wikimedia commons; cropped for the ease of viewing)

Gong Kai depicted Amei in unusual black makeup, which is also worn by female demons accompanying her (note the one carrying a kitty!). This might be a parody of the sanbai (三白; “three whites”) face painting popular in the Song period. She and her attendants wear robes decorated with depictions of the “five poisons” (五毒), a term referring to animals perceived as particularly dangerous and inauspicious. The exact list varies, though centipedes, scorpions and snakes in particular are mainstays. The five poisons are directly associated with Zhong Kui, as he can be invoked to ward them off. Direct evidence first appears in the Qing period in accounts of the well known Dragon Boat Festival, but it’s not impossible this was an earlier development.

It is presumed that Gong Kai’s painting might depict Zhong Kui and Amei looking for a demonic version of Yang Guifei, as indicated by various hints in colophons. Her portrayals in art are quite diverse, but attributing demonic traits to her would be hardly unparalleled - she could even be described as a “palace demon” (宮妖, gong yao). The decline of the Tang dynasty was blamed on her, and metaphorically she might have been invoked to criticize other people believed to improperly use the power granted to them by the imperial court.

Gong Kai’s painting also depicts a less recurring member of Zhong Kui’s entourage. One of the demons carries a fox, specifically a nine-tailed specimen. The association between this animal and Zhong Kui goes all the way back to the early Tang period. In one of the Dunhuang manuscripts, the demon queller’s entourage includes a nine-tailed fox and a baize, who acted as bringers of good luck alongside him. It’s also worth pointing out that in another text from the same site, his mount during the hunt for a wangliang (魍魎; I will likely cover this entity a future article, stay tuned) is a “wild fox”. Chun-Yi Tsai attributes the inclusion of a nine-tailed fox among Zhong Kui’s servants as a “family pet” of sorts to the portrayals of this supernatural creature both as an apotropaic antidote to poison (including the five poisons) and as a demon in its own right. It would be a suitable member of Zhong Kui’s entourage both as a conquered malevolent being and as an amplifier for his exorcistic, protective power. A further possibility is that the association is the result of wordplay. A new year celebration involving a procession of people dressed up as members of Zhong Kui’s entourage, including his sister and various supernatural attendants, was known as dayehu (打夜胡). The homphony between 胡 and 狐, “fox”, might have resulted in the inclusion of the animal among the helpers.

Post scriptum: Zhong Kui in Japan

Zhong Kui, as depicted in Extermination of Evil (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui - or rather Shōki, following the Japanese reading of his name - probably reached Japan in the Insei period. Many other figures originating in China reached a considerable degree of popularity in Japan at roughly the same time - Taishan Fujun, Siming, Wudao Dashen, Pangu, Shennong, the examples keep piling up.

The oldest known Japanese depiction of Zhong Kui, which you can see above, is a painting from the twelfth century set known as Extermination of Evil. It might look a bit outlandish compared to most of the other depictions shown through this article, but I was able to locate a very close Chinese parallel:

A Yuan period depiction of Zhong Kui from the collection of the Beijing Library, via Richard von Glahn’s Sinister Way. Reproduced here for educational purposes only.

This is a Yuan period illustration said to be based on Wu Daozi’s painting. Zhong Kui doesn’t look like a Tang scholar yet, and the jacket and wide-brimmed hat are remarkably similar. It seems safe to assume that the Japanese painter was following a similar model - presumably one of the many now lost early depictions of Zhong Kui. Slightly antiquated iconography surviving far away from the core area associated with a specific figure would hardly be unparalleled - it has been recently suggested that the baize/hakutaku is a similar case, with Japanese depictions and descriptions matching Tang sources fairly closely, but missing the elements which developed in the Song period or later. For the most part, Zhong Kui fulfilled a similar role in Japan as in China: he was regarded as a fearsome demon queller, and images representing him were distributed for apotropaic purposes. However, it’s also important to note that there were certain innovations. He arrived in Japan at the brink of the middle ages - theologically speaking an era of unparalleled innovation, during which both native and imported figures were interpreted in unexpected ways, leading to the rise of a new “medieval mythology”. Zhong Kui was hardly an exception from this trend. A “medieval myth” involving Zhong Kui is known from Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), an onmyōdō treatise traditionally attributed to Abe no Seimei, but most likely written by one of his descendants in the fourteenth century. Curiously, Zhong Kui’s name is written in it as 商貴 instead of the expected 鍾馗.

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

In the Hoki Naiden, Zhong Kui is still a queller of malevolent supernatural beings. However, instead of being a scorned scholar, he is a yaksha who became the ruler of Rājagṛha, a city in India. He is said to correspond to both the medieval Japanese deity Gozu Tennō (牛頭天王), and to his celestial “double” Tenkeisei (天刑星; from Chinese Tianxingxing), the “star of heavenly punishment” (I covered him here). They are said to be his manifestations respectively on earth and in heaven. This equation might seem random at first glance, but both of them actually had a lot in common with Zhong Kui: all three were believed to keep demons, especially those causing diseases, in check. Curiously, the reinterpretation of Zhong Kui as a yaksha turned king can also be found in the Genkō Shakusho (元亨釈書), a Kamakura period Buddhist history book. However, I am not aware of any studies examining it in more detail. I assume identifying him as a yaksha was a result of association with Gozu Tennō (I briefly discussed his yaksha credentials here), rather than the other way around, though.

While Hoki Naiden ultimately pertains more to medieval than modern religion, it’s worth noting that an unconventional take on Zhong Kui is still part of an extant tradition. Through history, Zhong Kui could be identified as a dōsojin (道祖神). This term denotes a class of deities meant to protect roads, crossroads and borders of villages. In parts of the Niigata prefecture this form of him is sometimes referred to as Shōki Daimyōjin (鍾馗大明神) today.

Bibliography

Joshua Capitanio, Epidemics and Plague in Premodern Chinese Buddhism

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Richard von Glahn, The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture

Shih-shan Susan Huang, Picturing the True Form. Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China

Wilt Idema & Stephen H. West, Zhong Kui at Work: A Complete Translation of The Immortal Officials Of Happiness, Wealth, and Longevity Gather in Celebration , by Zhu Youdun (1379–1439)

Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai, Imagining the Supernatural Grotesque: Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

tgcf crack au where there are three (two clones) hua chengs in the world

the flame master, wrapped in black clothes with bright red embroidery. eye covered with an eyepatch, reclusive, and when seen out of his palace is harsh. yet, somehow, the flame master became one of the most worshipped gods in heaven, his "flame" expanding to ghost fires and love. why?

an immortal priest, who wanders the lands. a sculptor, painter, devout worshipper. wearing red and white clothes, looking youthful and mischievous. he has a hand in the most breathtaking idols of the flame master, as well as a companion always by the flame master in his art pieces—a figure clad in white, sword and flower in hand.

a calamity in crimson and silver and black, lighting temples to flames and drawing blood with silver butterflies. in an ominous, crescent-smile mask, constructed a city for ghosts and became the bane of heaven. fell thirty-three gods with his martial arts and intellegence, until worshippers turned to him.

what do they have in common?

they are the same person. hua cheng; san lang; wu ming.

===

notes:

hua cheng imparts some "self" into the clones so they are basically apart of him

when hua cheng creates the ghost clone, he wants to remedy all mistakes wu ming made. he despises wu ming for being powerless. he also uses it as a lure, incase his highness did remember him.

san lang is actually a priest for dianxia, but he also wants to grow power as a god. so. even if he were ugly, he's willing to paint his highness next to him for the power to protect his highness.

with every passing day, wu ming grows more and more self-conscious, because his highness still isnt here, did his highness truly hate him? should he change, become unrecognizable, because his highness wouldn't come if he were there?

...anyways i think san lang should suffer a bit

while passing through yong'an, he witnesses the whole shebakle. in a panic, he shapeshifts into xie lian, effectively diverting all the punishment that should come. unfortunately, even if he were a clone, he still felt all the pain and isolation, and the talismans prevented him from escaping. later, after a few decades when he's finally tracked down, he has to he absorbed back into hua cheng because of the mental damage. hua cheng has to isolate himself after to calm his spirit (the only reason lang qianqiu isnt dead).

its just that i think xie lian should not be in the coffin. hes been through enough

anyways imagine if there were fanfiction about the priest and the god—oh wait.

yeah hua cheng discovers self-cest made by enthusiastic believers. idk would be rlly funny though

hey is there any active hua cheng clones in the books?? asking because i kind of am too lazy to reread it

#hua cheng#san lang#tgcf#heaven official's blessing#god hua cheng#clones#xie lian#guys i preordered the first three deluxe hardcover versions i have regrets#someone sedate me

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hu Ming - The East is Red

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zanado / ザナド, Shambhala / シャンバラ, and Agartha / アガルタ

Zanado (JP: ザナド; rōmaji: zanado), also known as the Red Canyon, is the site of ruins that the Nabateans once called home in Fire Emblem: Three Houses. This name comes from ザナドゥ (rōmaji: zanadu) Xanadu, more traditionally known as 上都, Shàngdū. Literally meaning "Upper Capital," Shàngdū was the summer capital of China's Yuan dynasty. When it was first constructed, the city was called 開平, Kāipíng; less than a decade later, it would be Kublai Khan who gave it the name we use today. In a century's time, Shàngdū would be abandoned, the people driven off or killed when the Ming dynasty wrested power from Toghon Temür, the last ruler of the Yuan.

Before its collapse, Shàngdū was a great city that even the Western world had heard of. Infamous Venetian explorer Marco Polo had visited during the reign of Kublai Khan. He referred to the city by the name Chandu or Ciandu, and thoroughly recounted the intricate, artistic structure of the city, remarking of rooms gilded and rich with paintings. The city held two palaces—one of marble, one of wicker—as well as a great park containing vast meadows, lovely fountains and brooks, and a plethora of flora and fauna. Three centuries later, the English cleric Samuel Purchas published a work that, for brevity's sake, we'll simply call Purchas his Pilgrimes, which collected descriptions of various locations and religions. Amongst this was a rewording of Marco Polo's account of Shàngdū, which Purchas instead called Xandu.

It was Purchas' documentation that reached English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1797. He was struck by an intensely vivid dream after reading of Xandu, and from this begot his famed Kubla Khan. He exaggerated the beautiful land that Marco Polo wrote of, and gave the world the Xanadu. He also conjured up a canyon that ruptured, the burst releasing a great river through the land. In that moment, Kubla Khan received a prophecy of war. The poem is most commonly thought to portray Xanadu as an idyllic paradise, and that interpretation persists to this day, with the name being synonymous with paradise and being conflated with similar concepts like Shangri-La. Curiously, the concept of Shangri-La is a paradise hidden away in a Tibetan valley.

The Red Canyon leans into the idea of Shàngdū being this long lost paradise. Even the fact that is a canyon of all things is likely derived from the Coleridge's poem. It could be interpreted that both the destruction of Shàngdū by the Mings and the explosion of the canyon relate to the atrocity that befell the Nabateans. Similarly, the fact that Shàngdū was utterly abandoned and forgotten, and is now largely remembered for this idealized image made by someone who only read someone else's account could tie into how the actual significance of Zanado is lost throughout Fódlan.

Shambhala (JP: シャンバラ; rōmaji: shanbara) is the underground city that the Agarthans use as their stronghold. The name Shambhala originates from Hinduism: according to the Vishnu Purana, it is in this city that Kalki, the final incarnation of the god Vishnu, is supposed to be born. It is said that he will end a dark era of unrighteousness and bring about the most virtuous age before Mahapralaya, the end of the universe.

The concept of Shambhala would later be adopted into Tibetan Buddhism, first mentioned in the Kalachakra tantra. In the story, King Manjuśrīkīrti banished thousands of people of his unnamed kingdom for practicing Surya Samadhi, the worship of the sun. As it turned out, these sun-praisers, were the wisest people of the land, and Manjuśrīkīrti was soon begging them to return. The majority of the exiles would found a city called Shambhala, which is prophesized as the origin of a savior similar to the Hindu city. It is said that when the world is overrun with violence and avarice, the Kalki king Maitreya would come from Shambhala and bring about defeat to evil and peace to the world.

Western esotericism would twist Shambhala into another form. Rather than an actual city, it was common for individuals like Alice Bailey to interpret Shambhala as a realm on another spiritual plane where the deity presiding over Earth resides. Further building off the ideas presented in Buddhism, others will interpret Shambhala as a land of a mysterious faction that do good throughout the world.

The Shambhala seen in Three Houses is very much a twisting of the classic prophecies. The Agarthans, while exiled by the Goddess to their subterranean lands like in the Buddhist text, instead use their great capabilities as a way to bring war, chaos, and darkness to the world. They also corrupt the "mysterious faction" found in esoteric works, but that more has to do with the last name to talk about today.

Agartha (JP: アガルタ; rōmaji: agaruta)was a highly-advanced civilization whose people were driven underground into Shambhala. Agartha is a mystical land found at the earth's core appearing in various occult and esoteric beliefs. Despite this, the name is very transparently derived from modern literature: Louis Jacolliot's Les Fils du Dieu told of the rise and fall of a lost Indian capital of Asgartha. The story followed no Indian traditions, instead styling for a historic account of Norse mythology based on various preexisting theories. In fact, Asgartha is derived from the Norse Ásgarðr, the land of the gods.

However, the book (and its two sequels) were incredibly popular in Jacolliot's homeland of France, and the way he framed to books as being derived from ancient manuscripts led to the idea of Agartha evolving into its own entity. Just over a decade later, occultist Alexandre Saint-Yves d'Alveydre would popularize the modern ideas of Agartha in his Mission de l'Inde en Europe. He claimed to have astral projected to an underground city with a population in the millions, all ruled by a powerful master of magic and advanced technology. From there, many occultists and esoterics would interpret Agartha as housing a Grand Lodge made up of the secret rulers of our world. It's easy to see how the concepts of Agartha and Shambhala are now commonly conflated with one another.

The Agarthans of Fire Emblem wear their inspirations on their dubstep-playing sleeves. They are a highly advanced people living under the earth's surface. They infiltrate the political scene of the overworld, manipulating the world to bring about a scenario that will let them claim revenge and utter domination of the world. Not to mention that their leader is a powerful spellcaster with actual missiles at his disposal. And in a sense of irony, all three of the locations we've looked at today are named after lands that have been viewed as paradise. Likely both the Nabateans and Agarthans thought what they once had was that perfect, idyllic life.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, what IS the Samadhi Fire/True Fire of Samadhi? It can't be an average flame if it can take out Sun Wukong himself in JttW and the name sounds like it means something, but I can't find any context when I look it up.

Journey to the West states that Samādhi fire is not like earthly or heavenly flame. It is something more. Part of a poem in chapter 41 reads:

(Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 2, p. 225)

The general concept of Samādhi (Sk: "concentration"; Ch: sanmei, 三昧) refers to an advanced level of meditation where one can "establish and maintain one-pointedness of mind on a specific object of concentration" (Buswell & Lopez, 2014, p. 743). Some Hindu and Buddhist sources associate it with a spiritually cleansing flame. One example comes from the Gaṇḍavyūha section of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra (Ch: Dafang guangfo huayan jing, 大方廣佛華嚴經; compiled by the 3rd or 4th-century CE).

Sudhana (Ch: Shancai tongzi, 善財童子; i.e. Red Boy), the holy work's protagonist, seeks out 53 teachers in the course of his spiritual cultivation. His ninth instructor, a learned Brahmin named Jayoṣmāyatana (Ch: Shengre poluomen, 勝熱婆羅門; lit: "Victorious Heat Brahmin") is said to have achieved "the light of the concentration [i.e. Samādhi] of adamantine flame" (jingang yan sanmei guangming, 金剛焰三昧光明) (Clearly, 1993, p. 1218). The fire that he produces is so powerful that it scares even the gods and demons. Though, the point of the flames appears to be incineration of the ego and desires and illumination of the mind. Sudhana follows his instructions by throwing himself into the fire, thus gaining a higher level of spiritual knowledge.

Here is a translation of that section of the sutra (warning: it is wordy):

(Clearly, 1993, pp. 1217-1222)

A Song or Ming-era Japanese painting of the fire brahmin and Sudhana.

Sources:

Buswell, R. E. , & Lopez, D. S. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press.

Cleary, T. (1993). The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Boston: Shambhala.

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

#Samadhi fire#Samadhi flame#Red Boy#Red Son#Journey to the West#JTTW#Buddhism#Hinduism#Samadhi#Lego Monkie Kid#Sudhana#Shancai tongzi#Chinese religion#Indian religion#meditation

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

A collection of mini fun facts : I'll explain them base on the sequence of the geography (MAP)

The CAPITALs : (orange circles)

Last time I talked about how palace in the anime take reference of Forbidden Palace, 🏛️ which is located in ☆Beijing, the capital city of Ming and Qing Dynasty.

However Xi'an🏛️ (aka ★ChangAn) is the capital city of TANG Dynasty,

which is the clothing style of the characters. (ChangAn is the ancient name of Xi'an)

FASHION :

During TANG, ★ChangAn, was a cosmopolitan and multicultural city since it is the starting destination of 🐫 Silk Road.

Ah Dou is wearing a riding suit, know as Hufu 👕. It was a fashion among the noble ladies to wear Hufu for horse ride🐴 . Hufu is male clothing of the *Western region (part of 🐫 Silk Road). [ *West is Central Asia, not Europe]

LOULAN : (red on map)

Maomao was curious of 💐Concubine Loulan who has Northen facial feature while wearing Southern outfit. In history, LouLan was the name of an ancient 👑kingdom at *Western region. It's location is modern Xinjiang near the now dried salt lake Lop Nur (MAP). The carved wooden beam above is an artifact of Loulan Kingdom.👑

NAIL POLISH :

Just as the anime, Balsam is a major ingredient for 💅nail polish (also for blush and lip color).

Balsam flowers are usually found in Central, East and South of Asia. When my grandma was a girl, she grounded the flower patels and apply them on nails then wait for a while , letting the juice to stain the nails before getting rid of the residue.

In ancient time, 💅 nail polish are made of juice of the grounded petals of balsam mixing with potassium alum. This chemical is used in drugs and silk painting / writing. 📚

WRITING :

Silk is more often used for painting than writing since it is expensive. Potassium alum is applied on silk as preparation for painting and writing.

Other than silk, bamboo and wooden slips were being used for writing, before paper is commonly used.

OX BEZOARS :

🐃 Ox bezoars (the drugs that turns Maomao into "upper moon demon" ) is used for de-toxing. 牛黃 is Chinese and kanji character of ox bezoars. Nowadays, it's made into tablet form know as 牛黃「解毒」片. In this context 「解毒」is meaning de-toxing. But some people mistaken 「解毒」means de - posion and think 牛黃「解毒」片 (Ox bezoars) can get rid of poison intaken by individuals, since Maomao mentioned to JinShin to use poison if she is ever facing death penalty.

#apothecary diary#maomao#jinshi#loulan#lihua#nail polish#horse#silk road#xi'an#Chang An#changan#beijing#tang dynasty#forbbiden palace#palace#japanese#chinese

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ming and Joe's Colors in My Stand-In, Part 5: Brown

Part 1: Overview

Part 2: Black and Blue

Part 3: Red and Green

Part 4: Yellow/Gold

Part 6: Random Color Moments

I received an ask a couple of days ago asking me about Joe and Ming's colors (which is something I've been thinking about for a while) and decided to answer that question in a separate post (which turned into a series). So, here I am.

I previously stated in my overview in part 1 of this series of posts that:

Ming is black and red.

Joe is blue and green.

Yellow/gold is significant to both.

Brown also has some significance.

As you can tell by the title of this post, I'll focus on the brown in this one. And as I mentioned in the overview in part 1 of this series, brown has significance to both Ming and Joe.

To be honest, brown is the color out of the ones I've written about that I'm most unsure of, but I'll give it a go anyway.

First of all, let's look at the symbolism before I dive into some color theory and then the fun stuff.

Brown is often associated with earth/soil, which is where its solid and grounding symbolism comes from. Brown is also associated with safety, security, resilience, sadness, loneliness, and isolation.

Several of those can be seen in the way they've used brown in My Stand-In so far.

The interesting thing I've noticed with the brown in the series is that it has two opposite roles. It either shows up when Ming and Joe feel the most grounded and relaxed or when things become "too much", too muddled, too stagnant between them.

Now, let's dive into some color theory. I wrote some brief color theory about the two ways in which I usually mix brown hues in the overview. This matters to my reasoning around the use of brown in My Stand-In, but I will only summarize it here since I've already written about it in the overview.

The first (and simplest) way I usually mix brown when painting is to mix orange and black.

I've previously established that one of Ming's colors is black (which I did in part 2). That's his contribution to the brown. I also mentioned in part 4 of this series that (even though they share the yellow/gold color, Ming is gold while Joe is yellow) Joe's yellow sometimes verges towards orange, which is why I call it yellow-ish. That's his contribution to the brown. (I'll get to the other way I usually mix brown in a moment.)

Often when Ming's moodiness or brooding and Joe's youth-like innocence mix together, the brown becomes too much.

An example is in this sequence where Joe has to stand in for Tong and work closely with a woman, whom Joe is really nice to and supportive of (since he's a kind person). Ming is on the set and watches it from behind the camera and becomes visibly moody. Then, he turns petty and tries to pay back with the sting Joe gave him (unintentionally, of course) by feeding Tong in a place where Joe can clearly see them. And this happens when they're both wearing brown (Joe's jacket and the pattern on Ming's clothes).

Another moment when Ming's black and Joe's yellow-ish mix to create brown is in this scene at the bar:

Joe is using some spontaneous deceit as he's trying to get Ming drunk at the bar (which was an unplanned excursion) so he can go back and destroy the evidence he left at his apartment. Ming, on the other hand, is still mourning his loss of Joe (even though he doesn't believe Joe is dead, he's mourning the void Joe left behind), to the point where Ming lets this man who is so similar to Joe 1.0 get him hopelessly drunk.

This scene is not as spiteful and moody as the previous scene, but the brown is still there, surrounding them. Even though Joe has an ulterior motive, and even though Ming shows his jealousy by pulling Joe away from the dude who hit on Joe, this scene is pretty chill compared to the previous one.

The second way I usually mix brown hues is by mixing the primary colors: yellow, red, and blue. Yellow is the color Ming and Joe share, red is Ming, and blue is Joe.

Just like Ming's shirt which includes Joe's blue, Ming's red, and their combined yellow/gold: (Btw, those gold lines being on either side of the blue stripes, which is Joe's color, made me pause the episode because all I could see was the image of their mugs, which were basically Ming's declaration of his love for Joe, mended by gold.)

They're also surrounded by those brown-ish/neutral hues as Ming is being more grounded than he's been in a long time, asking to give Joe a ride, and taking that opportunity to meet Joe's mom and learn new things about Joe 2.0. He's as resilient as he can be in finding Joe (though he wavered there for a while with the blind wise man).

Now let's look at some other scenes.

The brown is grounding when Joe's care, Ming's joy (which he only shows around Joe), and their combined warmth are mixed. Just look at how domestic they are as Joe is making food and Ming is making coffee. They feel as solid as they can at this point.

The brown is also grounding when Joe's loyalty to Ming (as he rejects Sol), Ming's love for Joe (that's slowly growing as he realizes Joe is talking about him), and the light they both share (the light they are in each other's lives) are mixed together.

This scene also leads into the next one where the brown is equally (if not more) grounding. This is when Joe's serenity (finding his peace in Ming), Ming's spontaneity (agreeing to move in with Joe), and their combined happiness mix together.

On the other hand, the brown becomes too much when Joe's loyalty (in particular, from Ming's perspective, Joe's loyalty to Sol, which Ming sees as a contributing factor to why Joe wants him to move out), Ming's anxiety (of losing Joe), and the deception they share (mostly on Ming's side with how he used Joe) are mixed together.

Or when Joe's way of communicating (in getting Ming to blindly trust him), Ming's love and desire for Joe (which turns him blind), and the deception they share (mostly on Joe's side as he's manipulating Ming in this particular scene) mix together.

Or when Joe's perseverance (in getting Ming to realize he didn't do anything with Tharn and that Tong is the problem), Ming's anger (in wondering why someone he "bought" is biting back), and the dishonesty they share (mostly on Joe's side who is hiding who he really is) is mixed together.

In other words, brown is present in some of their more explosive scenes, especially when their individual traits become too much and too unbalanced for them to handle. All it brings is sadness and loneliness for both.

One bonus scene with brown is this one:

Which leads Ming to erupt. He leaves Joe to sleep on the floor out of spite and jealousy. And, in the morning after, he snaps at Joe before ghosting him for some time, isolating himself from Joe.

Another bonus scene with brown is this one:

Where Ming is begging Joe to come back. He wants his safety back but, instead, his actions results in sadness and loneliness for both.

In other words, brown is a very emotional and explosive color for them that leaves them sad and lonely, but can also be the grounding color in their relationship.

Like with so many of the other colors I've written about, balance is key.

Part 1: Overview

Part 2: Black and Blue

Part 3: Red and Green

Part 4: Yellow/Gold

Part 6: Random Color Moments

#iq color post#color symbolism#color meanings#color theory#brown#big color moments#my stand in#my stand in the series#thai ql#thai bl#thai series#my shit#the colors mean things

15 notes

·

View notes