#look i KNOW the theories been disproven and its not scientific fact

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i think that dipper and mabel represent the left and right sides of the brain. thank you for coming to my ted talk.

#look i KNOW the theories been disproven and its not scientific fact#but it still is a good shorthand for those two aspects of human nature#if you have no idea what im talling about go read a book#three pigeons in a trench coat

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay

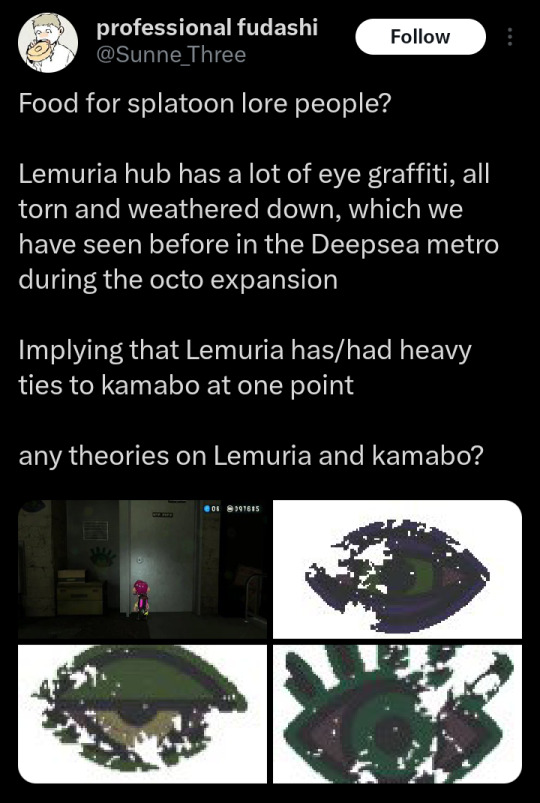

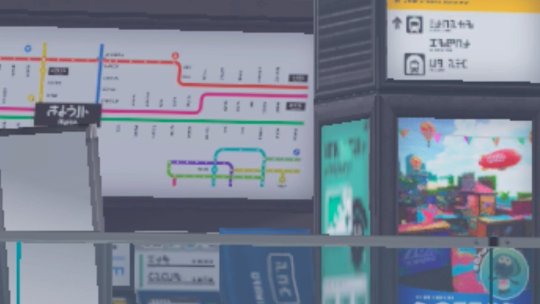

so i saw a post about Lemuria Hub and the Deepsea Metro having ties to each other, and i have a conspiracy theory that's been rotting in my brain ever since i saw the Deepsea Metro map in Lemuria Hub

here's all your proof of that:

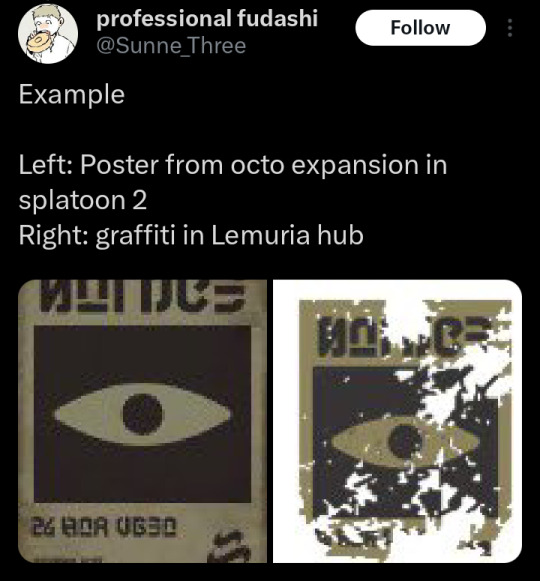

plus, the eye posters from Kamabo Co. being present in Lemuria Hub as well. it's pretty obvious from these that Lemuria and Kamabo are tied together.

we all know and remember Tartar's goal: bring back humanity. but the name "Lemuria" holds a lot more weight than most casual splatoon players might realize.

because i am a nerd, i looked it up.

From the Wikipedia page:

Lemuria, or Limuria, was a continent proposed in 1864 by zoologist Philip Sclater, theorized to have sunk beneath the Indian Ocean, later appropriated by occultists in supposed accounts of human origins. (...)

The hypothesis was proposed as an explanation for the presence of lemur fossils on Madagascar and the Indian subcontinent but not in continental Africa or the Middle East. Biologist Ernst Haeckel's suggestion in 1870 that Lemuria could be the ancestral home of humans caused the hypothesis to move beyond the scope of geology and zoogeography, ensuring its popularity outside of the framework of the scientific community. (...)

The theory was discredited with the discovery of plate tectonics and continental drift in the 20th century.

this (now disproven) theory ties in pretty neatly with Tartar's goal. "Bring back humanity". the implications of Lemuria Hub being tied to Kamabo Co. very likely means that Tartar's hypothetical new age of humans would have originated from Lemuria. Splatoon 3 seems to like a focus on origins, because we also get the origins of marinekind in its storymode, Alterna and the Return of the Mammalians.

but there's something else that caught my eye too.

SashiMori.

with the release of Lemuria Hub, nintendo brought back the fictional band, SashiMori! which is great and fantastic, but im pretty damn sure that they didn't bring any other bands back from Splatoon 1 or 2 completely unchanged for Splatoon 3. sure, OTH was brought back for multi-player OSTs, but in the form of Damp Socks. (and the idols are a sort of special case anyways.) Squid Squad returned only as Front Roe. Yoko from Ink Theory returned only in Yoko and the Gold Bazookas.

but nintendo didn't change SashiMori's presentation at all. the only thing that did change, and was notably very mentioned, was the fact that SashiMori's DJ Paul was older now. that's it. (nintendo also didn't change Acht. this is an important detail, but ill get to them in a minute).

Paul is pretty interesting when you look at him. there's very little information, but what we do have about him ties in pretty nicely with Kamabo Co., Tartar's association with humanity, and Lemuria Hub. for starters, Paul's DJ mixing for SashiMori is hailed as unique in universe, for incorporating human voices into SashiMori tracks.

From the Splatoon Wiki page on SashiMori:

Paul is the band's DJ, an Octoling. He is 10 years old in Splatoon 2 and 16 years old in Splatoon 3, and his favorite foods are kelp and biscuits. He remixes from sources including DJ Real Sole, DJ Octavio, and various ancient records, and is surprisingly talented for his age. Originally, SashiMori had a traditional vocalist, but they were replaced due to their self-centered personality, after which Paul was recruited through a tweet. According to the Japanese Family vs. Friends dialogue, he is friends with Marina.

(...) This music has vocals but no vocalist! Through the genius of DJ Paul, all the vocals have been sampled from a collection of ancient vinyl.

so, Paul and SashiMori are associated with humanity because they literally use human voices in their tracks.

here's the final nail in coffin to make it all tie together. it's a pretty popular theory that Paul and Acht "Dedf1sh" (who was sanitized by Commander Tartar and composed all the Octo Expansion soundtracks) are blood relatives.

Here's their designs from Splatoon 2 and Splatoon 3:

Acht and Paul have the same symbols on their hats. their ink color even matches (from before Acht was sanitized). Acht has blue tentacles and red tips, Paul has red tentacles and blue tips.

even from the wiki trivia section of SashiMori's page:

In-universe, Paul and Acht are speculated to be blood relatives. They notably have the same symbol appearing on their hats, wear black clothing, with Paul wearing black T-shirts in both album artwork and Acht wearing a black dress, have three tentacles for their hair, and Paul's ink color looks similar to Acht's ink color before they were sanitized.

so what does this have to do with Lemuria Hub?

following nintendo's trend of splatoon artist releases with each season, they bring back an old artist and repurpose them into a new band or presentation. for Sizzle Season 2024, the band they brought back was SashiMori, but completely unchanged. (tangentially related, for the release of Side Order, they brought back Dedf1sh, also completely unchanged.)

the return of SashiMori completely unchanged breaks nintendo's pattern. alongside that, the stage released this time was only Lemuria Hub, and no other stage. (with the exception of Drizzle Season 2024, which released only Marlin Airport,) the trend has been to release two stages per season. this time, it's only one stage.

TLDR:

Kamabo Co.'s goal was to bring back humanity via testing and blending marinekind through the deepsea metro. Acht "Dedf1sh" was the musician of Kamabo Co., and sanitized in the name of this goal. Paul from SashiMori uses human voices in his tracks. Acht and Paul are very likely related. Lemuria Hub has Kamabo Co. posters and its deepsea metro map on display. the name "Lemuria" is associated with the origins of humanity via a (now disproven) theory. SashiMori's new music was released alongside Lemuria Hub.

SashiMori's new songs, with human voices mixed in them, playing over the train station of Lemuria Hub, which was likely an access point of some kind or tied in to Kamabo Co. somehow, is an EXTREMELY POWERFUL AND INTERESTING IMAGE. Lemuria Hub is hearing human voices for the first time via SashiMori's new songs, and it's been taken over for the one thing Tartar hated the most about marinekind: Turf War. (in a twisted way, Lemuria Hub hearing human voices is probably what Tartar wanted, but I doubt it wanted it like this. very ironic, i approve.)

so what does all of this mean? well... we can only speculate at this point. the themes of humanity in Splatoon 3 are matched in quantity only by Salmon Run lore (but, that's a whole other essay post, i won't get into it here). i personally think it means that we're going to see some kind of connection to humanity, OR salmonid development/lore in the next game. and with the FinalFest theme for Splatoon 3 being "Past, Present, or Future", im REALLY excited to see what it could mean. maybe Tartar's alive somehow, or maybe we'll get to look back at the evolution and development of marinekind, or maybe Lil Judd will finally snap since he's taken over Grizzco and the salmonids will have their apocalypse.

(as a final ending note: there's also a TON of association from all of this... with Off The Hook. OTH is associated with nearly everything here; its speculated Pearl was SashiMori's original vocalist before they got Paul, Marina is friends with Paul, OTH helped 8 break out of Kamabo Co., Pearl herself murdered Tartar with her voice; Off The Hook changed the world with Chaos vs Order, and Off The Hook is representing "the present" in the FinalFest. coincidence? maybe. who knows?)

#splatoon#splatoon 3#deepsea metro#octo expansion#splatoon 2#commander tartar#splatoon theory#splatoon lore#paul sashimori#sashimori

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Night Vale Fan Episode: Curly Fries

I wrote this Welcome to Night Vale fan episode for fun. I had a lot of fun writing out an outline of the story and coming up with ideas for dialogue. I might not have built up the outro as well as I wanted to, it’s kind of emotionally discordant with the story, but I had fun writing it all anyway. Honestly the entire story is based on me hearing the song I chose for the weather three times in one day, associating it with a concept from the series, and imagining Carlos and Cecil driving while it plays in the background. I wrote around that idea and this is what I came up with. I don’t promise official quality but I hope you enjoy! -------------------------- Cecil: Not all who wander...are lost.

...But, uh, we are. We are very lost. Please help. Welc-

Carlos: Ooh, let me do it! Carlos: Welcome...to Night Vale! Cecil: Listeners, today’s broadcast is very special, because as I’m sure you’ve already deduced, we have a special guest in our midst- my husband, Carlos! With whom I am hopelessly lost in the desert. Carlos: Hi everybody, really glad to be here! Cecil, we’re not hopelessly lost. We’re talking to Night Vale right now! They’ll help us! Cecil: I’m...sure they will. Not terrified in the least. We’re definitely not going to wander this hellscape for eternity. Anyway, uh, Carlos, what brings you to the show today? Carlos: Well, Cecil, as you know, we were out on a date at the Night Vale Harbor and Waterfront Recreation Area, on a sunset stroll across the boardwalk, when we came across a vendor renting out metal detectors.

We rented one, went down to the...uh, beach...or, as much of a beach as it can be, considering there’s no water, and the ocean is only visible from the boardwalk itself, and started searching for treasures.

Cecil: Untold treasures.

Carlos: Yes, excuse me, untold treasures. Of the deep, you know, that sort of thing. But we wandered too far from the boardwalk and were swept out to sea by the phantom ocean, and we woke up...uh, here.

And now we’re stuck here, and we don’t know how to get home, and it’s very boring, so we’re putting on a broadcast together!

Cecil: Oh, it feels so good to be back on the air. Listeners, I don’t know how long we’ve been trapped here. My portable radio equipment doesn’t seem to be broadcasting, and my phone is dead. So I couldn’t reach anyone for help. Help we desperately need. Or we’re going to die here.

Carlos’ phone is fine, but he’s got no signal at all. He’s been trying to play Pokemon Go all morning and it’s just not working. It just shows his cute little trainer standing there in a big empty void of space, which is normal for the desert, but none of the Pokemon are showing up and it’s just been very frustrating for both of us.

Also, I wore these new boots, and I’m very upset that they are hurting my feet. They’re 6 inch high platform boots with a goldfish swimming in a little fish bowl embedded permanently in the platform with no hope of escape and no source of food, and after days of trying to break them in they still just aren’t comfortable for some reason. All things considered, this has not been a good morning for us.

Carlos: At first I thought we may be in the Desert Otherworld somehow, but that was quickly disproven when I realized my phone had no signal. Also, there are no mountains, or lighthouses, or crippling post traumatic stress reactions, or masked armies, or geographical loops. But mostly no cell phone reception. That place had incredible cell phone reception. Cecil: Really, the only thing here is lots and lots of sand, and also old televisions, refrigerators, mysterious piles of magnetic shavings, all sorts of neat stuff. It really takes my mind off the inevitable bleached skeletons we’re going to leave here in the desert. I’ve been playing with this metal detector and honestly, this place is a gold mine for neat junk that if we ever manage to find our way out with, I’m going to take home and then put in the garage, and every time I look at it I’ll think “Why did I bring this home with me? What was I thinking?”, before formulating plans to organize or dispose of it, only to keep it there forever as a monument to my obsessive need to collect mementos and symbols representative of my experiences in an attempt to create a physical record of the fact that I did something, went somewhere, was someone, even if they pile uselessly in a corner serving only to remind me that I opted for material goods and trinkets in lieu of crafting meaningful personal memories of events and loved ones that only I could ever truly understand that would die with me rather than be thrust upon whoever is saddled with the task of organizing my affairs after death, walking into my garage, seeing my pile of junk, and not grasping for even a second the depth of what I wanted it to mean and represent and communicate about my life, tossing it into the trash and along with it any dreams I may have had in the back of my mind of being immortal by way of inspiring others with my personality made manifest by collected worldly goods. Oh! And radio equipment! We found some radio equipment that seems to be working just fine, unlike mine. And to elaborate on this phenomenon, it’s time for the Children’s Fun Fact Science Corner! Carlos? Carlos: Cecil, and kids at home, my running theory is that we are trapped in another time entirely. You see, we’ve dug up a lot of stuff here. But all of it is from the past. When scientists do a lot of digging- it’s called Earth Science, by the way- they often find things underground organized in layers of sediment, one on top of the other. As you dig further down, you find older things, and that’s how we know which fossils are older than other fossils. But here, no matter where we dig, we seem to find things at random, completely disorganized. It’s very unscientific of these random objects to appear all in the top layer of dirt. Meanwhile, Cecil’s portable broadcasting equipment seems to work, but based on how none of you came out here to rescue us during our first several broadcasts, it doesn’t seem to be reaching you. I believe that it can only broadcast to the present day, and- because we are surrounded by anachronisms, we are not in the present day. It’s 2019, I think. So we should, in theory, only be surrounded by things people use in 2019. But we’ve dug up several Furbys and at least one toot-a-loop, which indicate that it is not 2019, wherever we are. We’ve found such a wide range of things there’s no telling what year it really is! But this set of radio equipment we found is timelessly elegant in its design, and so I believe it probably broadcasts to any point in time. Also I can pick it up on the portable radio we brought with us to the beach, so it’s definitely working. Cecil: It is true that my equipment only seems to broadcast to the present day. I know my phone back at the studio sometimes makes and receives calls through time itself, but I don’t know that I’ve ever broadcast to another era...but it is also possible that our listeners just plain aren’t feeling very helpful today. Maybe they’re busy. Maybe we’re doomed. Maybe we’re just doomed. Carlos: Cecil, nobody is ever too busy to listen to your show. And we’re not doomed. Cecil: Oh, Carlos, you’re embarrassing me. And we’re probably doomed. Carlos: I’m sorry, but it’s true. And it has to be, otherwise my theory sounds ridiculous. And we’re not doomed. Cecil: Fair enough. It sounds very scientific to me! Anyway, this has been the Children’s Fun Fact Science Corner. Also we’re doomed. Carlos: Cecil, I’m going to go run some tests with the metal detector and see if I can find anything to help us figure out where and when we are. And maybe a refrigerator that still has food in it. So far, besides the radio equipment, everything’s just a bunch of junk. I’ll take my radio with me so I can hear your broadcast, be sure to call me back if you need anything! Try to stay calm, alright? Cecil: Good luck, Carlos! Listeners, in the meantime, let’s get to the news. Local radio host Cecil Gershwin Palmer was reported as saying that despite the suffocating fear of eternity or the dark void of ceased existence, he doesn’t really mind being trapped in an endless mysterious desert, as long as it’s with his husband Carlos. He could, quote, “Do science here forever”, as long as it was with his handsome husband. Aw, isn’t that sweet?

Meanwhile, we’ve got...uh...there’s...hm. I’ll level with you, Night Vale. This place is booooo-ring. Nothing’s happening at all. There’s barely any plants. I’ve only seen one animal, and it was a lizard, and it was a very boring lizard. It only had 4 legs, and it just kind of sat there on a rock for a while. The fish in my shoes died, so their senseless agony is no longer a viable source of tragic entertainment. I can’t check my tumblr. It’s just dirt and sand and rocks and sun and junk. If we were going to be whisked away to a mysterious time and place, couldn’t it at least have been an interesting one? I do have to admit...I’ve tried to keep a strong, stoic face about this whole situation, but I’m getting a little worried. We don’t know how long we’ve been here. Carlos claims it’s only been a few hours, but you know how he is with time and perception and facts. There’s never any wiggle room with him for senseless anxiety and baseless assumptions of doom. I shouldn’t make fun, I’m sure he’s worried too. At least we’re here together, I suppose. Better than being lost in the desert alone... Oh, uh, looks like it’s time for Traffic.

A car, gliding effortlessly across the sands of a vast desert. The man inside turns up the radio, and hears a familiar story- familiar because it’s literally happening, right now. The radio describes his every action. The way he glances at the radio as if it is another human being to make eye contact with, questioning its words with his eyes. It describes the way he turns the dial to increase the volume. The way he furrows his brow, attempting to understand how the voice on the radio knows what he’s doing. The way he pulls out a set of beakers and places them carefully on the dashboard, normally a reckless act while driving, but completely safe in the flat, closed-course, car commercial style desert he’s driving on. He sends some colored liquids through swirling crazy straw tubes from one container to another, a bunsen burner aflame, attempting to science some sort of sense out of this disembodied narrator. The liquids are turbulent and sloshing, but he does not care. He looks out the windshield and stares at a dot, in the distance- and the dot stares back. He focuses all his energy, all of the vehicle’s horsepower, the entire weight of his leg on the gas pedal, and every photon receptor in his eyes on that tiny...little...dot. He stares with such intensity that his eyes start to lose track of their own interpretation of the light that enters them, blurring into one solid color, forcing him to focus on something else to be able to focus back on his goal. He blinks furiously. The dot becomes bigger, and bigger, and bigger, until finally- he sees that it’s me! Hi Carlos! This has been, Traffic. Carlos: Cecil, look! The metal detector came through! I found a 1987 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am 2-door coupe! And a renewed interest in those psychic energies I told you that you sometimes give off and that I really need you to let me probe into! Cecil: A car, that’s wonderful! We can use that to get...home. Assuming it’s...nearby, and that we’re...in the same timeline as home, and...in the same year. Maybe we’ll even be back by dark! The sun is starting to set... Carlos: Cecil, I know how to get back home. We’re going to be okay. Get in the car. Wait- first, help me take the t-tops off. On the drive back we may as well enjoy the weather. [THE WEATHER] Cecil: Listeners, we are home. As we drove dramatically with sweeping camera angles and rolling hills through that sudden downpour of mysterious flashes of light, pink clouds, psychedelic wind, nostalgic VHS fog, and laser beams erupting from the desert floor, the sun set and we could see in the distance a guiding light. As we drove towards it, we reached an old dirt road, and down that dirt road, we found a fence, and a gate, and a sign. I turned around in my seat to read the sign, and...well, you remember a few years ago, when we got the new landfill, which doesn’t accept any physical items? Carlos: My theory had one major flaw. I thought based on all the anachronisms we had found in the dirt, all at the same layer of sediment, we must be in some sort of mishmashed timeline, outside of the linear time that we’re normally outside of, but also outside of the non-linear time we’re normally not outside of. Some third form of time never before seen. But they...well, they weren’t anachronistic. There weren’t any items from the future. That would be anachronistic. Everything we found was from the past. Which is...normal. That’s just normal. That’s how time works, even here. Cecil: Yeah, we were...just...in the old landfill. Also my portable radio equipment was working fine, I just...forgot to...plug in the microphone. I was very stressed. I forget to plug in microphones when I’m stressed. Carlos: I guess the sand blew over top of it over time and hid it entirely, and the phantom ocean must have created a phantom beach next to the raised sands as a result, and we washed up on top of it. But, hey, even if my science was flawed, at least we got to spend the day together, and I got to be a big part of your show! Plus, it was my day off, so I really didn’t want to do any accurate science anyway. Cecil: Yes, we’ve never done a show together like this. It was a lot of fun even if I was terrified the entire time. Carlos: Cecil, I was scared too, but I didn’t want you to worry, so I tried to be strong, for you. And you know, despite the suffocating fear of eternity or the dark void of ceased existence, I also wouldn’t really mind being trapped in an endless mysterious desert, as long as it’s with you. I could, quote, “Do radio broadcasts there forever”. Cecil: Aw, you were listening! And so intently. That’s almost word for word, with adorable changes in perspective. And it’s a good segue into an inappropriately sappy closing statement for tonight’s broadcast. Listeners, Steve Carlsberg, my brother in law, speaks often of lights and guiding markers in the sky, telling him exactly how the universe works. I’ve never really believed in any of that stuff. But today, some lights in the sky showed Carlos and I the way home from the old landfill. As soon as we crested the horizon I saw them- and I’d recognize those lights no matter where they were, Arby’s or not. Sometimes I wonder if maybe they’re part of something bigger, too, like the lights in the sky Steve talks about. They lead us home today. And they lead us to each other years ago. Carlos, I’m glad we have each other. I’m glad we have this place. I’m glad we have delicious roast beef sandwiches and curly fries with horsey sauce. We have not eaten in days. I love you.

Carlos (mouth full of curly fries): Aw, Cecil, I love you too.

Cecil (mouth full of curly fries): Today’s broadcast is sponsored by Arby’s. Not officially, it’s just, (swallows), we’re currently eating Arby’s and I don’t know how to end the broadcast. I don’t normally do broadcasts off the cuff like this. Carlos: I know how to end it! Can I end it? Cecil: Well, I mean, it’s my show...I always...um. You know what, sure, it’s fine. Go ahead. Carlos: Good night, Night Vale! Carlos and Cecil: Good night.

#welcome to night vale#welcome to nightvale#WTNV#nightvale#night vale#cecil palmer#carlos the scientist#fanfiction

105 notes

·

View notes

Note

Aside from Zombieman who are your favorites? Also what’s in Genus’s basement

OH BOI yeah this took a while to answer cause I actually had to compose my thoughts on the matter. It's a lot, long post ahead friendos

It would be easier and faster to list my LEAST favorites asdfghjkl but Hmmmm surprisingly, would you believe the reason I even started watching opm was because I saw Geryuganshoop and adored the weird simplistic alien squid design? He was actually my first fave lol oops??? Buuuut now, aside from Z, definitely Metal Bat, Genos, Child Emperor... And honestly Phoenixman? Also pretty darn high up there on the list is Tanktop Master, as well as Lightning Max, Oneshotter, Mizuki and Needlestar I love their Dynamic so much holy crap, and Atomic Samurai's disciples. The Egg himself goes without saying. Homeless Emperor and Vampire Pureblood also hold special places for me, which may or may not be obvious as to why... really though i just love everyone minus like, 3 or 4 characters who dont do much for me. but ANYWAY

What is in Dr. Genus's basement.

This question has been absolutely PLAGUING me since I read the chapter.

So to start, I'm going to go over something thats crossed my mind, but i don't think will (or want to) happen.

It is possible that it will be an actual device or method Genus has developed to remove a limiter. I don't want this. Mainly because we know it won't work, so it would likely end very badly for Z. But really, going off what we know of how such a thing might work, we have been shown that extreme stress (e.g. multiple near death experiences) result in major power-ups assuming the individual survives. So if there IS something in the basement meant to remove a limiter... well I'm praying its not some sort of torture device. And given Z's apparent subborness, immortality, and general nihilism, I don't think he would nope the fuck out of there if faced with such a thing, either. The fool would absolutely agree to some dumb thing like that. So. Please no. ONE I'm on my knees begging you not to do this. Please don't hurt him I'll die I swear

But as for my best guess... honestly, we don't really have much to go on here. At surface level, Genus appears to be telling the truth, and has disband the HoE and it's research. After witnessing Saitama' s impossible strength, the crushing realization that the culmination of his life's work and entire belief system was fundamentally flawed logically would have him give up the house of evolution and it's goals. HOWEVER, that isnt to say he gave up science and research altogether. Actually, I would find that REALLY hard to believe. Heck, even The anime emphasized the intensity of his passion for scientific advancements. Even if his current belief system upon which he founded the HoE was blatantly disproven, the passion and desire to learn and understand and discover doesn't just dissolve into thin air. I think it would be near impossible for someone who has dedicated their entire life to research to just... give up science altogether, at least in such an abrupt manner.

Remember this cool thing season 1 did that showed up 3 times and never again?

So why wouldn't he just switch gears? Saitama has essentially solved the same problem Genus was trying to tackle, only through a completely different method. What reason would Genus have to NOT begin researching the Nature of Saitama's power? And actually, the fact that Genus was even able to explain as much as he did about the 'limiter' to Zombieman during their reunion suggests he did just that. He at the very least looked into the subject enough to coin the term 'limiter' and create a theory about how every being has one, etc.

At the same time, when Zombieman confronted him about the House of Evolution, axe raised and ready for execution, Genus didn't seem particularly worried. Rather, he admitted he didn't have much left to live for. So I think, though he may have started research into the 'limiter' and its removal, I think he was unable to make any sort of headway on emulating Saitama and has since given it up. Or at the very least, if it IS ongoing, he honestly doesn't see any sort of success on the horizon. If he truly thought he could replicate Saitama's power, with or without its prices, I don't think he would have accepted death so quickly? I think his passion would have been reignited, and he would be doing SOMETHING with his findings. He wasn't the type to just... die with unfinished business. Quite the opposite actually, remember he was willing to die in order to see his research through to the end at the hands of Carnage Kabuto.

So, I'm lead to believe that there is SOMETHING pertaining to research on limiters in the basement. Maybe failed experiments, maybe calculations upon calculations with impossible solutions. I'm thinking Genus is going to show Zombieman why 'removing his limiter' isn't just a simple task that can be done at the drop of a hat. I think this will largely be a way for us the audience to recieve some more insight on how the limiter theory works. That said, I'm not certain where that will leave Zombieman. So long story short, I'm still quite worried for Z, and don't know where his story is going.

#option 3 infinite octopus tentacle dungeon#👀#ahahaha i regret nothing (by that i mean everything)#zombieman#dr. genus#opmiss mumbling#theory#i gues??#also mad spoilers#web comic#web comic spoilers#spoilers#one punch man#opm#ask#gottahaveguts#thanks dude i totally went off whoops#this was a good one#sorry i cant to a read more on mobile asdfghjkl

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

a modern prometheus - chapter one

description: A large figure was standing at the foot of his bed. It towered above him, head brushing up against the ceiling. The figure noticed Logan’s movements, and it bent down, as if trying to get a closer look at him. Logan’s throat closed up as he recognized the figure for what it was. It was the creature—the one he had left lying in the lab with as much life in it as a rock. And here it was now, eyes an odd yellow color in the half life. Its mouth was twisted up in an odd grimace. It almost looked like it was attempting to smile. (OR: logan discovers the secret to life and decides the best course of action is to create his own human)

warnings: dicussions of death, bodies and slight body horror (nothing graphic)

notes: i present the frankenstein au that nobody asked for! it’s spooky month, so of course i have to adapt my favorite horror story to my favorite fandom!! i mostly wrote this because logan sanders is ten times the man victor frankenstein could ever be lol. there’s going to be three chapters, and hopefully it should be done by halloween!! i really hope you like this first chapter!! i also want to give a big shout out to the wonderful @nobody-is-evil who beta’ed this chapter,, thank you so much!!!

~~~

Logan was, by birth, Genevese.

This isn’t a particularly important fact, but it does paint a picture into the way Logan was raised. Imagine, if you will, a cottage on a humble piece of land. Beyond the fence that does little to dictate borders, rolling hills slope away as far as the eye can see. To the right, a large lake where Logan spent many a day sailing with his brother, Patton, and his childhood friend, Roman, by his side. Down to the left, a barely paved road that leads into a respectable sized village where everyone knows each other.

It should be pointed out that in technical terms, Patton was only Logan’s brother by mere association. No blood was shared between the two boys; Patton was brought into the family when Logan was five and Patton was four. Patton had been treated rather cruelly by his aunt, who had been tasked with his upbringing when his mother died, and when Logan’s mother had found out about the situation, she immediately volunteered to take over Patton’s well being. Logan, who was only five and understandably didn’t comprehend the difference between biological and adoption, took Patton under his wing as only an older brother could do.

He even missed Roman, a fact that took Logan by surprise. Roman had lived in the town nearby Logan’s home, and even to this day Logan still didn’t know how he and Roman became acquainted. From the beginning, Roman was loud and obnoxious. He had gotten into his head that he was a knight, that kind that populate the pages of the fantastical and romantic books he was always reading. He would do his best to rope Patton and Logan into performing plays with him, acting out adventures involving knights and damsels in distress and, often at the request of Patton, dragons. Logan would rather have done a great many other things than play along, but he secretly enjoyed Roman’s talent for weaving stories.

The time not spent with Roman and Patton (or with his nose deep in a book) was occupied by wandering the fields around the cottage. Nature was something that had always fascinated Logan—he admired the way it was resilient against all odds. Plants died and came back each year, animals ventured into places of danger just to get food.

Logan loved nature, and he had notebooks filled with notes and observations about anything and everything.

It’s this love of nature that leads Logan to the works of Cornelius Agrippa, and then later on Paraulus and Albertus Magnus. Each philosopher has their own ideas on what they call “natural science”, and while Logan is sceptical about some of their ideas, he does admit that it’s all rather interesting.

He asked his father about the philosophers one day. His father took one look at the covers of the books Logan held in his arms, shook his head, and said, “Don’t waste your time on these, Logan. Those books are nothing but trash.”

What Logan’s father should have explained was that Agrippa’s theories had been long since disproven, and that modern science had advanced further than any of the philosophers Logan was reading could ever imagine. But he didn’t say any of that, and so Logan continued to read and absorb every bit of information about natural science that he could.

He was fifteen when his mother died. The sickness struck out of nowhere, taking his mother in the blink of an eye. Nothing could be done to save her, no matter how hard the doctors tried, and her loss hit the family like a ton of bricks. Logan locked himself in his room for a week, refusing to speak to anyone who came knocking at his door. When he finally emerged from his room, eyes red and puffy, he continued to hold his silence on the matter.

The death of his mother followed him around wherever he went, unable to be shaken off.

Two years later, his father sent him off to college. Logan had been going to different schools in Geneva, but his father found the university of Ingolstadt and decided that it could offer Logan the chance to learn about life outside his own little world.

Logan could hardly wait to go.

Patton was excited for Logan, but he couldn’t help but be a little upset as well. He and Logan had always been together as children, and this would be the first time they would be apart for longer than a day.

“Be sure to write every day,” he told Logan on the day he left for university, clinging to Logan’s hand as if he wanted to make sure that Logan was really there.

“I will,” Logan promised, squeezing Patton’s hand gently.

“I expect letters too,” Roman said, hitting Logan on the back in what was supposed to be a friendly gesture, but really just made Logan stumble forward.

Logan knew for a fact that Roman would be sending him letters comprised of all the “adventures” he and Patton would take in his absence. The thought stung a little, although Logan would never admit to it. He had a reputation to uphold, after all.

The journey to Ingolstadt was long, and Logan’s only company came in the form of his books and his thoughts. The carriage driver didn’t talk to him at all throughout the trip, much to his disappointment, and so Logan filled his time with writing letters and rereading the books he shoved into his bags before he left. Logan was relieved when he finally saw the buildings that made up the city of Ingolstadt. He was never going to spend that amount of time in a carriage ever again if he could help it.

As soon as the carriage stopped, Logan was shown into an apartment that his father had rented out for him. It was rather nice, with two rooms—a bedroom and what looked like a sitting room. As soon as he saw it, Logan began to plan out all the ways he could convert the room into a makeshift lab. He wasted no time unpacking and getting to work making the apartment his own.

The next day, Logan went out to meet the professors he would be studying under. The first one he met was Professor Aisling, who taught natural philosophy. He was a rather laid back man, always with a drink in hand, and the two talked at length. Aisling asked Logan a lot of different questions, such as why Logan was interested in the natural sciences and different works he had read.

It’s during this conversation that Logan casually admit that he’s mostly read Agrippa and the like, rather than the newer works in the scientific world. He didn’t think too much of that, but the statement gave Aisling pause.

“You’ve really spent your time reading that?” he asked, leaning back slowly in his chair and giving Logan a look of disbelief.

“Yes?” Logan said, not sure how his reading habits could have confused the man so greatly.

Aisling rolled his eyes and took a long drink from his mug before answering. “I hope you realized that you wasted your time with those books,” he said matter-of-factly, pinning Logan with a frown. “You could have studied today’s greatest scientific discoveries, and what did you do? Read about a science that has been disproven over and over again.”

Logan was suddenly reminded of his father, and the disdain he held for those books all those years ago.

Shaking his head, Aisling scribbled down a list of books and shoved the paper at Logan. “Here. You’ll need to read all of these if you want to be caught up with where we are in class.” And with that, he ushered Logan out of his office and closed the door before Logan can get a word in edgewise.

Logan decided right then and there that he hates Aisling. The man hardly gave him a chance to defend himself, and his haste to brush aside the philosopher's Logan spent years reading leaves a bad taste in Logan’s mouth. Of course he knew most of those ideas aren’t one hundred percent scientifically sound, but Aisling made it seem like Logan was stupid for reading them.

There’s another professor of natural science, Professor Picani, but Logan doesn’t get the chance to meet him before classes start. The first time he sees Picani is during a lecture. Logan doesn’t expect much - he’s still skeptical after the way Aisling acted, but he’s willing to at least give Picani a try.

The first thing that Logan noticed about Picani is that he was so excited about everything. He all but bounced into the room and gifted every single person sitting down with a dazzling grin. He started off with a warm welcome, as if they were already close friends, and then launched into his lecture. It’s mostly an overview of modern natural science, with terms and explanations, but it’s the end of the lecture that draws Logan’s attention.

“Science,” Picani said, hands waving animatedly, “is a constantly changing field. We know things today that scientists years ago could never have dreamed of! Every day is an opportunity for growth! And we have to remember that without the philosophers and scientists of the past, we never would have been able to reach the levels of knowledge that we have today.”

After hearing Picani talk so enthusiastically about the philosophers that Aisling had flatly insulted, Logan started to feel much better about his place at the college. After the lecture, he went up and introduced himself to Picani.

They go through the same questions Aisling asked, with Logan telling Picani why he’s studying natural science and the like. But when Picani hears about what Logan had read in the past, he seemed delighted to learn that Logan was so familiar with Agrippa.

“They’re the reason we can do what we do today, you know,” he said, inviting Logan into his office. It’s a warm and inviting place, walls painted a cheery color and bookshelves stuffed to the brim. “They laid the groundworks and let us study the world more in-depth.”

Logan felt like a weight was being lifted off of his shoulders. He began to ask questions about Picani’s lectures and if Picani has any books he recommends Logan read to help him in his studies?

Pushing a cup of tea into Logan’s hands, Pianci beamed at him. He seemed happy to answer all of Logan’s questions. He got slightly sidetracked when he began to ramble on about all of his favorite books, and he makes Logan a list as he goes along. He also took Logan into the lab right off his office and gave him a tour, pointing out each instrument and explaining their uses. Logan took it all in with wide eyes and tried to commit everything to memory.

The night left Logan with a lengthy list of books to read and an open invitation to Picani’s office if he ever needs anything. “You’re going to do great!” Picini promised him when Logan leaves.

The semester started soon after, and Logan threw himself into his studies with fervor. His days bled into his nights, and all his time became consumed by his studies.

When he managed to pull himself away from his work, he wrote letters to Patton and Roman. They’re usually just responses to whatever they sent him previously. Logan’s letters could be longer; he writes brief overviews of his work and answers any questions they send his way, but that’s about it. Sometimes he feels guilty, like he’s neglecting them, but then he’ll get distracted and that particular worry gets pushed to the back of his mind.

He kept every letter he gets. Patton’s detail each daily activity, from the walks he took into town to the latest thing he baked. Roman’s are filled with stories he would normally have Logan act out with him; Roman seemed to be determined that the distance between them isn’t stopping Logan from having to hear about his latest fantasy.

Whenever Logan felt lonely or discouraged, he pulled out the letters and read them over and over again until he feels better.

It was sometime later during his studies that Logan became interested in the human body. Anatomy in itself is a complex science, but the question that plagues Logan’s mind is the idea of life.

What causes life? What exactly lead living things to breathe, to walk around and have ideas of their own?

It’s something that scientists and philosophers had questioned for as long as the world existed, but no one had ever found the answer. It’s one of the greatest mysteries of nature, and most people have accepted it at face value, not bothering to wonder too deeply why exactly it occurred.

Logan wasn’t one to let things lie, and he’d be damned if he let the question go unanswered.

Of course, before he can really determine what caused life, he had to understand what takes it away. Anatomy became his newest area of study. He frequented mortuaries throughout the city and observed exactly how bodies decay over time.

He doesn’t mention this part of his studies in his letters to Roman and Patton; he knew it would only upset them. They were both fascinated with superstition, stories told in the dark with the intent of sparking fear in the heart of the listener. Logan, on the other hand, never paid any attention to these stories, and so the nature of his work wasn’t clouded by fear. He approached every case with logic and logic alone, not allowing his emotions to get in the way.

His days were spent in a haze. All his other studies were left to the wayside. What importance were they? Logan was trying to figure out the great mysteries of the universe; essays on different historical figures could wait.

Logan couldn’t say for sure how long he worked like this, days bleeding into nights with little time for sleep or food, but then it changes. One minute he’s paging through a book Picani had given him, and the next he’s hit with an Idea.

It’s a capital-I Idea that is so earth shattering that Logan drops everything he’s holding and lunges for his notebook, immediately scribbling it down so that he’ll remember it.

When everything is said and done, Logan will be asked how he managed to find the answer to the spark of life. And Logan won’t have an answer. It’s only through extreme sleep deprivation and sheer will alone, he’ll say later, that he was able to succeed in his experiment.

But that’s later, when Logan’s had time to reflect. For now, Logan is so entirely convinced of his genius that he’s certain nothing could go wrong.

Logan’s Idea, in short, is how to bring life to something that dies. Any sane person would recognize the fact that bringing things back from the dead is impossible; it goes against nature and anyone who thinks they can is just kidding themselves. But Logan wasn’t exactly in his right mind, which might explain how he is able to twist the laws of nature to his will without even trying.

He decided that the best way to go about proving his hypothesis was to create his own body. He could technically find a body to use, but something about that felt wrong. Logan refused to dig up any graves or sneak into any mortuaries to steal a body. He may have been tampering with the fabric of nature, but he had standards.

So Logan decided that he’ll make his own human. And it’s here that Logan encountered his first problem.

Human beings are complex, filled with delicate veins and organs that are woven so intrinsically through one another that the slightest mistake could spell disaster. Logan knew all this too well, evidenced from the anatomical maps he spent months hunched over by candlelight. Logan’s hands are sturdy, but he isn’t perfect.

His solution is to just make a bigger human. This way, he reasoned, everything would be on a bigger scale and there would be less room for error. Did that make any sense? Of course not. But Logan was busy trying to create life itself, and didn’t bother wasting time by wondering if his actions made sense.

Getting the parts required for the completion of this project was difficult, to say the least. Logan tried his best and tried to keep the parts consistent throughout. It didn’t always work, and Logan learned early on that beggars can’t be choosers. He took what he can get, whenever he can get it, and tried his best not to get caught.

It’s slow going, but eventually Logan gathered enough supplies to form a fully functioning human body. He kept everything in the back room of his apartment, which he had finished converting into a lab ages ago. The body lay on a table in the middle of the room.

Logan thought it was beautiful. Most people would disagree.

It was a dark and stormy night when Logan put the next stage of the plan into action. The body was prepped and all the instruments Logan gathered had been switched on, humming with energy. He himself is scribbling down notes in his notebook, muttering to himself every now and then. Everything had to be perfect. This had to work.

The most important part of the set up was the lightning rod, which was hooked up to the body with wires that run and twist across the floor. Logan set the whole thing up himself, climbing out of the window with armfuls of wires and balancing precariously over the city. Electricity was the key to this whole experiment, and with this device he could harness it to give life to his creation.

With each strike of lightning, Logan could feel his excitement rising. He was hovering over the edge of a groundbreaking scientific discovery. If he could only prove his theory to be correct, if he could get the body’s heart pumping, he could change history as the world knew it. The world of science would explode and, thanks to him, humans could discover a cure to death.

Logan glanced quickly at the clock mounted on the wall, noting the time. The storm raged around the apartment; at any moment the lightning would strike the rod, and Logan would find out if his calculations were correct.

Any moment now.

And then it happens. A bolt of lightning struck the rod in a violent crackle of energy, sending sparks flying into the air. The electricity raced through the wires and into the body.

It’s like an explosion went off. The body arched up into the air, electricity coursing through its veins. Thunder cracks over the building like a gunshot, rattling the windows with enough force that Logan feared they’d shatter. He cried out, fear and excitement mixing into one another.

But as soon as it started, it was over. The body sagged back to the table, the blue sparks that had been surrounding it fading away. Silence settled over the lab, heavy and all encompassing. Logan waited with bated breath, wide eyes watching the body and shaking hands clutching his notebook like a lifeline.

And then the body took in a breath.

As quickly as he could, Logan flew to the body’s side, notebook abandoned on the floor in his haste. He fumbled for the body’s wrist and pressed down, searching for a pulse. For a moment he couldn’t locate it, and panic started to settle into him. Had he been mistaken about the breath? But then he felt the heartbeat pulse against his fingers and he nearly sobbed with relief. It was weak, only fifty-six beats per minute, but it’s there. It worked.

“I did it.” He whispered to himself, tears blurring his vision. He created life. He was right. He’s dizzy with joy, and his mind began to race, thinking of all the ways he could break this news to the world.

The body’s ragged breathing drew Logan’s attention back to the present. The breaths were few and far between, and they sounded painful. The body’s eyes seemed to be moving sluggishly beneath the lids. When Logan checked the pulse again, he found that it dropped down to thirty-two beats per minute.

“Come on,” Logan said, louder now, talking to the body—talking to the new life he’s created. “You can do it. You’re alive! Just keep breathing, come on.”

He kept talking, alternating between encouragement and outright begging. He needed this to work; he needed this new creature to open its eyes and sit up and prove that Logan was right. Logan talked for the better part of an hour until his voice cracked with overuse, trying his best to keep the creature alive, but it’s no use. The creature’s pulse slips away and its breathing stops altogether.

Tears slid down Logan’s cheeks, but now for an entirely different reason. He was so close. He was right there, had gotten the heart and lungs to start working and then had fallen short. Why did he think he could do this?

Logan drops the creature’s wrist and stumbleed away from the table. The adrenaline that was driving him for the past few weeks ebbs away, leaving bone weary exhaustion in its place.

Something had obviously gone wrong, but at the moment Logan had no idea what it could be. He needed to go over his notes, to review every little step in an attempt to find what exactly could have caused this experiment to fail.

But right now he needed to sleep.

Collapsing into his bed is a welcome relief. Logan can’t remember the last time he’d gotten a proper night sleep; he’d been so consumed by his experiment that there really wasn’t much time for anything else.

He’s asleep as soon as his head hits the pillow.

Logan wasn’t sure how long he slept. It could have been a few minutes, or several hours. All he knew was that the next time he woke up, light was beginning to filter in through the window, casting the corners of the room into shadow.

He rubbed his eyes tiredly. He had forgotten to take his glasses off before he fell asleep, and they hung awkwardly off his face. Adjusting them, he unconsciously glanced around the room—and froze.

A large figure was standing at the foot of his bed. It towered above him, head brushing up against the ceiling. The figure noticed Logan’s movements, and it bent down, as if trying to get a closer look at him.

Logan’s throat closed up as he recognized the figure for what it was. It was the creature—the one he had left lying in the lab with as much life in it as a rock. And here it was now, eyes an odd yellow color in the half life. Its mouth was twisted up in an odd grimace. It almost looked like it was attempting to smile.

Logan gaped up at the creature in disbelief. The creature tilted its head and made an odd, garbled noise.

“Hello,” Logan said weakly, fluttering his fingers weakly up at the creature.

And then he promptly passed out.

~~~

tag list (lmk if you want to be added or taken off!): @basilstorm@artistfromthestars@storytellerofuntoldlegends@romananalogicality@verymuchanidiot @istolelittleredshoodie @dont-cry-croft @speechless-angel@thefamouszombiebouquet @wolfwalker100 @datonerougecookeh@virgilient @virgil-is-verge@impatentpending@zaisling@trixie85592 @sillysandersides @hamster-corn @adventurousplatypus @unring-this-bell@mymiddlenameisunderscore @evilmuffin @zephyrria

#logan sanders#sanders sides fanfiction#roman sanders#patton sanders#ts frankenstein au#halloween fic#katwrites#i hope you guys like this#i'm honestly really excited about this#this chapter is a bit slow#because i have to work up to everything#but i promise next chapter has so much more with logan's creation (aka virgil lol)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Magic Works

These are just some of many different theories about how spells work. For anybody who really enjoys “magical theory” like I do or is looking for validation that there’s something to all these weird spells! None of these serve to discredit magic, but rather add a deeper level of understanding to it. The success of a spell could be credited to more than one of these, or something else entirely!

Law of Attraction. Basically, the idea that you attract what you focus on. A popular example is focusing on the color red, and seeing how much red is around you that you didn’t notice before. This is most effective for spells involving personal matters and success, by formally opening your eyes to details and opportunities you may have missed otherwise.

The Placebo Effect. It’s a proven fact that our bodies can heal ourselves merely by belief that what we’re doing helps! This can extend beyond health spells to things like confidence, performance ability, and other things that aim at personal improvement. The placebo effect may be all that spell needs to be successful ( and it wouldn’t have happened without the spell!)

Direct cause/effect. Something about the spell and the way it was cast directly affects the outcome. Example: a sigil designed for protection, when looked at, serves as a constant visual reminder that you are protected, subconsciously strengthening your wards.

Science/chemistry. This is most true for kitchen witchery and herbalism. Chamomile, lavender, and other herbs aren’t corresponded with calmness and sleep for nothing... they’re made up of chemicals that have been scientifically proven to calm the nerves and aid in sleep!

Quantum physics. There’s a phrase called “Quantum Woo,” where people use quantum physics (often incorrectly) to explain any type of magical thinking or practice. While the ultimate theory behind quantum physics was recently disproven, the discoveries made through research still hold true. Basically, we know particles behave differently when observed, and our energies can effect this. We just don’t know why that is. This is the baseline behind a lot of energy work.

Divine string pulling. Ask and ye shall receive. This is where we depart from the physical to the spiritual side of magic. Many people do magic by appealing to divine forces, Mother Earth, God(s), the Universe, whatever you want to call it. This could be with an offering, a ceremony, or even just bedside prayer. The divine force hears the request, and grants it by affecting change and “pulling strings” to cause the desired outcome.

Spiritual string pulling. Very similar to the previous point, but with entities that are not worshipped or seen as divine. Many believe that spirits can still affect change “behind the scenes.” A spirit worker may make a deal with a spirit for luck or protection, or someone may ask their ancestors for good fortune and health.

Personal string pulling. Instead of asking an outside entity, this is the idea that we, as the practitioner, pull the strings. This is most seen through the “cone of energy” method of casting, where we raise a lot of concentrated energy and intent in a space, then release it all at once to do its thing. You also see it with sympathetic magic, where by doing something to a poppet, we actively affect that change on the target. No middle man included.

19K notes

·

View notes

Link

The most famous psychological studies are often wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. Textbooks need to catch up.

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

The study took paid participants and assigned them to be “inmates” or “guards” in a mock prison at Stanford University. Soon after the experiment began, the “guards” began mistreating the “prisoners,” implying evil is brought out by circumstance. The authors, in their conclusions, suggested innocent people, thrown into a situation where they have power over others, will begin to abuse that power. And people who are put into a situation where they are powerless will be driven to submission, even madness.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been included in many, many introductory psychology textbooks and is often cited uncritically. It’s the subject of movies, documentaries, books, television shows, and congressional testimony.

But its findings were wrong. Very wrong. And not just due to its questionable ethics or lack of concrete data — but because of deceit.

A new exposé based on previously unpublished recordings of Philip Zimbardo, the Stanford psychologist who ran the study, and interviews with his participants, offers convincing evidence that the guards in the experiment were coached to be cruel. It also shows that the experiment’s most memorable moment — of a prisoner descending into a screaming fit, proclaiming, “I’m burning up inside!” — was the result of the prisoner acting. “I took it as a kind of an improv exercise,” one of the guards told reporter Ben Blum. “I believed that I was doing what the researchers wanted me to do.”

The findings have long been subject to scrutiny — many think of them as more of a dramatic demonstration, a sort-of academic reality show, than a serious scientific finding. But these new revelations incited an immediate response. “We must stop celebrating this work,” personality psychologist Simine Vazire tweeted, in response to the article. “It’s anti-scientific. Get it out of textbooks.” Many other psychologists have expressed similar sentiments.

Many of the classic show-stopping experiments have lately turned out to be wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. Yet many introductory psychological textbooks have yet to be updated. And it’s high time that we teach the next generation of students to understand them this way.

In science, too often, the first demonstration of an idea becomes the lasting one — in both pop culture and academia. But this isn’t how science is supposed to work at all! New studies offer conclusions that are most likely to be amended with time. No one thinks of Galileo’s simple tube telescope as the go-to instrument for modern-day astronomy. Our most sophisticated telescopes in operation today don’t even work with light our eyes can see, a fact Galileo might have found preposterous.

In recent years, social scientists have begun to reckon with the truth that their old work needs a redo, the so-called “replication crisis.” But there’s been a lag — in the popular consciousness and in how psychology is taught by teachers and textbooks. It’s time to catch up.

Many classic findings in psychology have been reevaluated recently

Getty Images

The Zimbardo prison experiment is not the only classic study that has been recently scrutinized, reevaluated, or outright exposed as a fraud. Recently, science journalist Gina Perry found that the infamous “Robbers Cave“ experiment in the 1950s — in which young boys at summer camp were essentially manipulated into joining warring factions — was a do-over from a failed previous version of an experiment, which the scientists never mentioned in an academic paper. That’s a glaring omission. It’s wrong to throw out data that refutes your hypothesis and only publicize data that supports it.

Perry has also revealed inconsistencies in another major early work in psychology: the Milgram electroshock test, in which participants were told by an authority figure to deliver seemingly lethal doses of electricity to an unseen hapless soul. Her investigations show some evidence of researchers going off the study script and possibly coercing participants to deliver the desired results. (Somewhat ironically, the new revelations about the prison experiment also show the power an authority figure — in this case Zimbardo himself and his “warden” — has in manipulating others to be cruel.)

Other studies have been reevaluated for more honest, methodological snafus. Recently, I wrote about the “marshmallow test,” a series of studies from the early ’90s that suggested the ability to delay gratification at a young age is correlated with success later in life. New research finds that if the original marshmallow test authors had a larger sample size, and greater research controls, their results would not have been the showstoppers they were in the ’90s. I can list so many more textbook psychology findings that have not stood the test of time.

Like:

Social priming: People who read “old”-sounding words (like “nursing home”) were more likely to walk slowly — showing how our brains can be subtly “primed” with thoughts and actions.

The facial feedback hypothesis: Merely activating muscles around the mouth caused people to become happier — demonstrating how our bodies tell our brains what emotions to feel.

Stereotype threat: Minorities and maligned social groups don’t perform as well on tests due to anxieties about becoming a stereotype themselves.

Ego depletion: The idea that willpower is a finite mental resource.

Alas, the past few years have brought about a reckoning for these ideas and social psychology as a whole.

Many psychological theories have been debunked or diminished in rigorous replication attempts. Psychologists are now realizing it's more likely that false positives will make it through to publication than inconclusive results. And they’ve realized that experimental methods commonly used just a few years ago aren’t rigorous enough. For instance, it used to be commonplace for scientists to publish experiments that sampled about 50 undergraduate students. Today, scientists realize this is a recipe for false positives, and strive for sample sizes in the hundreds and ideally from a more representative subject pool.

Nevertheless, in so many of these cases, scientists have moved on and corrected errors, and are still doing well-intentioned work to understand the heart of humanity. For instance, work on one of psychology’s oldest fixations — dehumanization, the ability to see another as less than human — continues with methodological rigor, helping us understand the modern-day maltreatment of Muslims and immigrants in America.

In some cases, time has shown that flawed original experiments offer worthwhile reexamination. The original Milgram experiment was flawed. But at least its study design — which brings in participants to administer shocks (not actually carried out) to punish others for failing at a memory test — is basically repeatable today with some ethical tweaks.

And it seems like Milgram’s conclusions may hold up: In a recent study, many people found demands from an authority figure to be a compelling reason to shock another. However, it’s possible, due to something known as the file-drawer effect, that failed replications of the Milgram experiment have not been published. Replication attempts at the Stanford prison study, on the other hand, have been a mess.

Science is a frustrating, iterative process. When we communicate it, we need to get beyond the idea that a single, stunning study ought to last the test of time. Scientists know this as well, but their institutions have often discouraged them from replicating old work, instead of the pursuit of new and exciting, attention-grabbing studies. (Journalists are part of the problem too, imbuing small, insignificant studies with more importance and meaning than they’re due.)

Thankfully, there are researchers thinking very hard, and very earnestly, on trying to make psychology a more replicable, robust science. There’s even a whole Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science devoted to these issues.

Follow-up results tend to be less dramatic than original findings, but they are more useful in helping discover the truth. And it’s not that the Stanford Prison Experiment has no place in a classroom. It’s interesting as history. Psychologists like Zimbardo and Milgram were highly influenced by World War II. Their experiments were, in part, an attempt to figure out why ordinary people would fall for Nazism. That’s an important question, one that set the agenda for a huge amount of research in psychological science, and is still echoed in papers today.

Textbooks need to catch up

Psychology has changed tremendously over the past few years. Many studies used to teach the next generation of psychologists have been intensely scrutinized, and found to be in error. But troublingly, the textbooks have not been updated accordingly.

That’s the conclusion of a 2016 study in Current Psychology. “By and large,” the study explains (emphasis mine):

introductory textbooks have difficulty accurately portraying controversial topics with care or, in some cases, simply avoid covering them at all. ... readers of introductory textbooks may be unintentionally misinformed on these topics.

The study authors — from Texas A&M and Stetson universities — gathered a stack of 24 popular introductory psych textbooks and began looking for coverage of 12 contested ideas or myths in psychology.

The ideas — like stereotype threat, the Mozart effect, and whether there’s a “narcissism epidemic” among millennials — have not necessarily been disproven. Nevertheless, there are credible and noteworthy studies that cast doubt on them. The list of ideas also included some urban legends — like the one about the brain only using 10 percent of its potential at any given time, and a debunked story about how bystanders refused to help a woman named Kitty Genovese while she was being murdered.

The researchers then rated the texts on how they handled these contested ideas. The results found a troubling amount of “biased” coverage on many of the topic areas.

But why wouldn’t these textbooks include more doubt? Replication, after all, is a cornerstone of any science.

One idea is that textbooks, in the pursuit of covering a wide range of topics, aren’t meant to be authoritative on these individual controversies. But something else might be going on. The study authors suggest these textbook authors are trying to “oversell” psychology as a discipline, to get more undergraduates to study it full time. (I have to admit that it might have worked on me back when I was an undeclared undergraduate.)

There are some caveats to mention with the study: One is that the 12 topics the authors chose to scrutinize are completely arbitrary. “And many other potential issues were left out of our analysis,” they note. Also, the textbooks included were printed in the spring of 2012; it’s possible they have been updated since then.

Recently, I asked on Twitter how intro psychology professors deal with inconsistencies in their textbooks. Their answers were simple. Some say they decided to get rid of textbooks (which save students money) and focus on teaching individual articles. Others have another solution that’s just as simple: “You point out the wrong, outdated, and less-than-replicable sections,” Daniël Lakens, a professor at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, said. He offered a useful example of one of the slides he uses in class.

For example: pic.twitter.com/WdtbjcZ6mR

— Daniël Lakens (@lakens) June 11, 2018

Anecdotally, Illinois State University professor Joe Hilgard said he thinks his students appreciate “the ‘cutting-edge’ feeling from knowing something that the textbook didn’t.” (Also, who really, earnestly reads the textbook in an introductory college course?)

I tried to frame things as four steps: 1) here's the big idea 2) here's the famous study and how it illustrates 3) here are the damning criticisms 4) here's what you can do as scholars to figure out what you believe / make a contribution to the literature

— Joe Hilgard, that psych prof we all know and love. (@JoeHilgard) June 11, 2018

And it seems this type of teaching is catching on. A (not perfectly representative) recent survey of 262 psychology professors found more than half said replication issues impacted their teaching. On the other hand, 40 percent said they hadn’t. So whether students are exposed to the recent reckoning is all up to the teachers they have.

If it’s true that textbooks and teachers are still neglecting to cover replication issues, then I’d argue they are actually underselling the science. To teach the “replication crisis” is to teach students that science strives to be self-correcting. It would instill in them the value that science ought to be reproducible.

Understanding human behavior is a hard problem. Finding out the answers shouldn’t be easy. If anything, that should give students more motivation to become the generation of scientists who get it right.

“Textbooks may be missing an opportunity for myth busting,” the Current Psychology study’s authors write. That’s, ideally, what young scientist ought to learn: how to bust myths and find the truth.

via Vox - All

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trying to convince the public that one model is unlikely and one model is most likely by sayin my one is right and one is wrong is not only untruthful it is just as likely to create more annoying problems in the future or worse completely destroy public credibility to the point where dinosaurs leave the realm of plausible but unlikely to pure fantasy..

Ummm... isn't that how science works? Like besides the fact that plumage in maniraptorans is confirmed and no longer a hypothesis but in general searching for the most accurate hypothesis to test and compare. It is the scientific venture.

Otherwise we'd stick to now disproven the Davson-Danielli model of protein membrane and not accept the more realistic fluid mosaic model. There is no such problem with the responsibility of "upholding public credibility by being consistent" because it is scientific research that is curated by different perspectives and not some form of entertainment that requires PR so to make them err... not become fantays creatures? Or making it annoying? Like look, me personally, when the quadruped Spinosaurus got invalidated at sometime due to the possible mixup with another dinosaur's remains and it seems like the bipedal reconstruction is correct? I was disappointed. But if that was the truth then it is, regardless the new discoveries this year.

As much accuracy as possible is the purpose of science right? The reason for everything? We built computers to calculate more accurate numbers down to the digits. We study the neural connections in our body down to the teeniest dendrites for accuracy. Will we achieve pure accuracy? Not guaranteed. But how is accountable trial and error to achieve that called misinformation?

And it's not that palaeobiologist and theorizing and hypothesizing with no basis or proper methodology without being called out. This is why palaeontologists hate David Peters with his batshit theories. The palaeontological field has accountability and reassasments, it's not a creature design class where anything can happen (assigning a fossil to a species could take a decade, new theories are critically explored too just look at the Soimosautus discourse) ; the theories or speculative portions of it are made with awareness of it being speculative and also limited with realms of realism. Of course these expert would know better than the public, duh its their field, they study this for their living. And yet this does not absolve any discussions between them nor unrealistic 'pushing' of their certain agendas. Outliers would certainly be called out and therefore there is no orthodoxy.

Ok now to feathers. It'a concrete evidence. This is not like Spinosaurus that has 1 questionable remain or anything. It'a widspread and many people have already stated it above. We may not know how they look like, their exact behaviours, their plumage arrangements, or colors (though we do for some), bit we know they indeed have feathers. It's fact just like how water is wet. There is no orthodoxy or "unprovenness" when it is something that has been proven a thousand times. That should be common pro-scientifc praxis. Isn't it the basic scientific method?

And the public either doesn't recognize this due lack of significant representation of this fact or anti-science attitudes. There is no understanding that this is the absolute truth and no enough understanding separation fiction and reality in this aspect that warrants that much 'creative' representation in the form of naked raptors when the more accurate representations are not recognized or sidelined.

Like I'm sorry for health of academia, I think your arguments are very anti-science. Not making (based) assumptions is due to fear of contradiction is strictly against the scientific method. Being wrong despite a basis is not the destruction of credibility, its a chance to learn and grow and achieve the best version of something. However we need to accept that what we have right now is the best of now because if we just wait out for some hypotethical future "answer" it just stunts us from ever developing in the first place.

Hey just a quick reminder

82K notes

·

View notes

Text

(You Can’t) Prove It.

[October 10th, 2017]

One of my favorite comedians is a mixed-race man by the name of Louis C.K. If you aren’t familiar with him, he is a well-known, long-time comedian with several specials on Netflix, and a show on FXX named Louie. While his comedic style can be described as dark, dirty, crass, and possibly even disturbing, his masterful ability to critically and accurately analyze society is, quite simply, profound. There’s one story of his in particular that I quote to people often, where he tells about a time he talked to an atheist about life after death. Upon asking the atheist what he thought it would be like, the atheist responded with this:

Atheist: “Well, do you remember, like, when you were born and when you were a baby and stuff?”

Louis: “W- well, no, not really.”

Atheist: “Yeah, so, kinda like that.”

That perspective has always amazed me. I often ask people to imagine this perspective, and they often reply with something along the lines of “that would suck”, but it wouldn’t. It wouldn’t suck, but it wouldn’t be great either. It would be nothing. You would stop existing, stop feeling, stop thinking, stop being anything at all. You wouldn’t experience anymore. You wouldn’t be. But, as a Christian, I don’t believe that will happen to me, or anyone else, for that matter. But I can’t prove it. Does that mean it’s false?

Atheists and other religious skeptics often claim that due to the lack of evidence proving God’s existence, that he is therefore not real. This way of thinking is false; a lack of evidence towards one thing doesn’t count as evidence towards it’s disproval, because each side needs its own evidence. It means that it can’t be proven true – but it also can’t be proven false. It means that it is a theory: something that is plausible, but not factual. Even when I say this, people will often misconstrue this, because many people associate the word “fact” with “true”. While this can be accurate in many cases, there are many other cases where things that are not facts can be truths. Universal morals, like how it is bad to murder, is not a fact or law of the universe, but it is a truth. The same goes for religion. Religion is a theory, which means that it is not necessarily factual, but it is true. It took us nearly seventy years to find any evidence towards Einstein’s theory of relativity, and an average atheist would be more likely to support that theory before the discovery of evidence before religion. Funny enough, whether that applies to you or not, we will be using Einstein’s theory of relativity to help explain “my theory” of why science and religion are two parts to one whole: the scientific-religious creation story, and the logical intervention of God in modern times.