#like I WANT that level of linguistic and historical and cultural details

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I feel like reading wuxia originally written in english doesn't do it for me after reading mdzs and tgcf. like obviously they have issues as novels and translation hiccups, but I just can't go back to awkward english-language wuxia-style stories that try to make things simple and digestible for english speakers. like I'm aware what 'authenticity' even means is a whole conversation too but thats what it feels like and I'd rather have these stories in their original language ig.

or maybe I've just never found a good wuxia-style english novel :/ bad luck from me

#as for the fact that I've never been able to get into any webnovel besides mdzs and tgcf and fgep. well I'm very picky#but none kf my issues were 'I feel like this is dumbed-down gruel bejng fed to me as an american'#like I WANT that level of linguistic and historical and cultural details#that was not the reason I had to quit qjj.#OH YOU KNOW WHAT. she who became the sun was not dumbed down. that was pretty good. I dropped it for other reasons#but maybe I should try it again. give the a physical book a try#cor.txt

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

die prinzessin

(PLATONIC könig & sister!reader)

summary: So... turns out your mystery half-brother is a giant Austrian special forces operator. What now? (Catching up on two decades of sibling bonding, that's what)

originally posted on ao3 (wordcount: main version 3.1k)

Rating: T

Relationships: Platonic König & Reader, König/Horangi

Ao3 Tags: Brother-Sister Relationships / Sibling Bonding / Long Lost/Secret Relatives / reader is konig's half sister / Implied/Referenced Self-Harm (reader has scars implied to be from SH but it's ultimately left up to interpretation) / Deutsch | German / Author speaks German (as a second language) / Historical References / reading the prior installment is recommended but not required

this is a part of a series

Notes:

Possible triggers: - König teaches MC to shoot. No violence, but he gives her semi-detailed instructions on how to handle a sniper rifle. - MC talks about past mental health struggles, and König notices old scars of her. These are implied to be from SH, but I tried to leave it open-ended for anyone who doesn't want that in their reading. - König implied to have previously experienced homophobia.

Prior context: I recommend reading the previous installment in the series, but if you really don't wanna here are the truly crucial parts: Your name is Elisabeth "Elise" Linh Veidt, a medical student. You were kidnapped to serve as hostage for a half-brother (König) you've never met before, who ended up rescuing you. There's more, but it's not directly tied to this fic so I'll leave it unspoiled in case you do become interested in reading the first work in the series. I do not use Y/N. I sometimes do use "Elise" & other specific details (you'll see why it's unavoidable in this fic) but I try to—when possible—keep things vague so you can freely project onto her (ex: using "your hair" instead of "your dark hair").

About the German: I speak German as a second language. I like to assess my skill level as "I know what Genitive is, but I don't always remember to use it." As Hochdeutsch-speaking foreign civilian, my speech patterns/vocabulary are going to be pretty similar to Elise's but very different to König, a native Austrian and a hardened soldier. I tried translate as accurately as possible (lots of LEO usage), but besides maybe a "servus" or two, I made and will make no attempt to mimic the Austrian dialect because it's frankly a lost cause for me. That being said, if you are a native speaker and notice any grammatical/syntactical mistakes (or even any sentences where you go "he would not fucking say that" [ex: a term being super formal or old fashioned] please let me know!

About the legibility: This is the primary iteration of the fic. If the German really does make it impossible to read, here's a version devoid of foreign language, but if possible, I highly recommend reading this version for the fullest experience. This version is the most proofread edition and even if you don't speak the language there was linguistic nuances you can still pick up on. If there are any cultural references you don't get, I have an explanation post linked at the bottom. (also available here)

"Können wir jetzt sprechen?” [ Can we speak now? ]

“Fast,” [ Almost ], your brother answered as he continued to guide you through the complex’s winding halls. His refusal to answer questions until your surroundings were secure made the flight over to the KorTac base feel endless.

Finally he stopped at a door-lined hallway. Approaching the second on the left, he punched a combination into its keypad. It swung open, revealing a modest bedroom.

“Großes Bett” [ Big bed ], you noted. His cot was large, even for someone of his rank.

“Ich habe ein Verzicht erhalten” [ I got a waiver ], he lazily indicated at his height. You were once again reminded of your stark height difference.

You looked at him—or at least what you could see of him with the mask—again. Drawing from your bio classes, you knew you shared 25% of your DNA. Clearly none of it manifested in height. Your father had been tall, but even at his peak he was nowhere near as lofty as your brother.

“Deine Mutter muss riesig sein.” [ Your mother must be giant .]

“Sie war.” [ She was. ]

You mentally winced. Way to get off on the wrong foot.

“Meine Mutter ist auch verstorben. Früher dieses Jahres.” [ My mother also passed. Earlier this year. ]

“Entschuldigung.” [ My condolences ].

“Du weißt, dass unser Vater schon ein paar Jahren gestorben ist.” [ You know that our father died a few years ago. ]

You really hoped you weren’t the one to break the news to him.

“Ja, ich weiß. Wir haben einen Brief bekommen.” [ Yes, I know. We received a letter .]

“Gut.” [ Good .]

“Dein Name ist Elisabeth, ja?” [ Your name is Elisabeth, correct? ]

“Ja.” [ Yes. ]

You’re not surprised he knows. There’s gotta be a file on you somewhere packed with everything you’ve ever even sniffed at.

“Magst du deinen Namen?” [ Do you like your name? ]

“Wie bitte?” [ Pardon? ]

“Benutzen Sie Elisabeth oder etwas anderes?" [ Do you go by Elisabeth or something else? ]

“Elise. Und du musst nicht ‘Sie’ benutzen. Wir sind Blut.” [ Elise. And you don’t need to be so formal. We’re blood .] A beat passed. “Wie heißt du?” [ And you? What is your name? ]

“Jeder nennt mich König.” [ Everyone calls me König. ]

“König? Ist das nicht ein wenig dramatisch?” [ King? Isn’t that a bit dramatic? ]

“Wenn du so groß wie ich bin, gibt es keinen Raum für Subtilität. Auch mag ich Geburtsnamens nicht.” [ When you’re as big as me, there is no room for subtlety. Plus I’m not the biggest fan of my birth name. ]

“Darf ich fragen?” [ May I ask? ]

“Ludwig.”

“Ludwig? Wie der König? Der Verrückte?” [ Ludwig? Like the king? The mad one? ]

“Genau. Ich mag es nicht, aber möchte es noch würdigen.” [ Exactly. I don’t like it, but I do enjoy paying tribute to it in my own way.]

“Elisabeth und Ludwig. Unser Vater mochte die Wittelsbacher, ja?” [ Elisabeth and Ludwig. Our father had a fondness for the Wittelsbachers. ]

“Wenn ich der Märchenkönig bin und du die Sisi bist, bist du Kaiserin?” [ If I’m the Fairy Tale King, and you’re Sisi… wouldn’t that make you the Empress? ]

“Dann wäre ich dir überlegen.” [ I would outrank you then. ]

“Gefällt dir das als mögliches Rufzeichen?” [ Would you like that as a callsign? ]

“Was? Kaiserin? Muss ich wirklich einen?” [ What, Empress? Do I even need one? ]

“Ja. Es würde mir ein Stein vom Herzen fallen. Dein Name ist kostbar. Verrate es nicht. Zumindest nicht hier.” [ I think so. It would ease my mind. Your name is a precious thing, I don’t want you to give it away. At least not while you’re on base. ]

Your stomach twisted.

“Du hast mir gesagt, dass dieser Ort sicher sei.” [ I thought you said this place was safe. ]

“Ja voll. Aber jeder kann mithören und hacken.” [ It is. But anyone can tap into radio comms or steal files .]

“Was meinst du damit?” [ What are you implying? ]

“Es ist zusätzlicher Schutz. Bitte. Es könnte irgendetwas. Ich brauche nur, dass du eines hast.” [ It’s an extra barrier of protection. Please. You can pick whatever it is, I just want you to have one. ]

You thought about it for a moment.

“Ich möchte nicht ‘Kaiserin’ sein. Das ist zu viel Macht und Anstrengung. Die Kaiserkrone hat die echte Sisi erwürgen.” [ I don’t want to be ‘Empress’. That’s too much power and pressure. The imperial crown strangled the original Sisi, after all. ]

A smile bloomed on your face.

“Vielleicht zulasse ich ‘Prinzessin’.” [ I might be amenable to ‘Princess’ though. ]

“Prinzessin? Ich kann damit leben. Sinn für kurz?” [ Princess? I can work with that. Sinn (meaning sense/reason/mind) for short? ]

You nodded with deep gravitas, “Einer von uns muss die Intelligenz sein.” [ Someone needs to be the brains around here. ]

Something about the faux-seriousness in your tone made the two of you burst into uncontrollable laughter.

The moment is so beautiful, you almost don’t want to ruin it with the question you know you have to ask. Something ancient, the spirit of Orpheus or Pandora perhaps, urges you to look.

“Darf ich über der Maske fragen?” [ Can I ask about the mask? ]

He paused for a moment, hesitant. Then quietly he spoke:

“Ich kann es ausziehen. Du bist Familie.” [ I can take it off. For you. You’re family, after all. ]

There’s a reluctance in his voice that made your heart twinge.

“Du musst nicht wenn du nicht willst.” [ You don’t have to if you don’t want to. ]

“Nein.” [ No. ] This time his voice seems more resolved, “Ich möchte.” [ I want to. ]

He pulled off his hood. His face was ruddy, but it worked well with his light hair and eyes. You two both looked so similar yet so different.

“Du hast alle guten Gene geerbt,” [ You clearly got all the good genes, ] you joked.

He turned his head bashfully, accidentally revealing his battered side profile.

“Deine arme Nase! Was passiert?” [ Your poor nose! What happened to it? ]

“Zebrochen. Ein paarmal. Bisschen verwickelt medizinische Hilfe zu erkriegen wenn du deinem Gesicht verheimlichst.” [ Broke it. A few times. Bit hard to get medical attention when you refuse to show your face. ]

“Nächste Mal einfach ruf mich. Ich habe dein Gesicht schön gesehen.” [ Next time just come to me. I’ve already seen your face. ]

“Mit Verlaub zu sagen, wie viel kannst du hilf mit helfen?” [ No offense, but how much can you help? ]

“Ja leider. Was weiß ich?” [ You’re right. What do I know? ] you bit back. “Ich habe nur noch ein Viertel vom Medschule übrig.” [ I’m only a quarter out from graduating med school. ]

“Soll das ein Scherz sein?” [ You’re joking. ]

“Das war nicht im Bericht?” [ That didn’t make it into the file? ]

“Nein. Wann ist der Abschluss?” [ No. When’s graduation? ]

You tensed. He was beaming with pride. You hated to ruin it with the ugly truth.

“Ich weiß nicht ob ich graduiere.” [ I don’t know if I will graduate. ]

“Warum? Hast du schulische Probleme?” [ Why? Are you having troubles at school? ]

“Sozusagen. Meine Noten sind gut, aber heuer versuchte ich zu ausscheiden. Sie ließen mich nicht, so nahm ich Gewaltkur.” [ Sort of? My grades are fine but… I tried to drop out earlier this year. They wouldn’t let me so I took more… drastic measures. ]

König’s eyes drifted to your scars.

“Sie sind alt.” [ They’re old, ] you reassured. “Und danach dem ganze Entführungquatch, ich bin entschlossen zu überleben. Vetrau mir. Deshalb möchte ich nicht zurückkehren. Ich möchte leben, nicht in Schule sorgen.” [ Plus after the whole kidnapping ordeal, I’m more determined to live than ever. Trust me. That’s why I don’t want to go back. I want to live, not suffer more in school. ]

Your brother looked at you disapprovingly, “Du musst zurückgehen.” [ You need to go back. ]

“Kann ich einfach hier bleiben? Bei dir? Ich könnte Medizinerin sein.” [ Can’t I just stay here with you? I could be a medic. ]

"Medizinische Arbeit ist nicht leicht.” [ Being a medic is hard work. ]

“Fleiß ist kein fremd.” [ I’m no stranger to hard work.]

“Du wärst ein bessere Medizinerin, wenn du Schule fertigbringst.” [ You’d be a better medic if you finished school. ]

You stared at him with arms crossed, unyielding.

He tried again, “Wenn du dein Medizinstudium abschließt kannst du hier arbeiten. Und du erhältst eine besondere Belohnung von mir.” [ Look, if you graduate you can work here full time—and I’ll ensure you get a special reward. ]

“Was?” [ What? ]

“Eine Überraschung. Du wirst es schön wissen.” [ It’s a surprise. I won’t tell you. Yet. ]

You pursed your lips. Clearly this wasn’t an argument you were going to win.

“In Ordnung. Aber lass mich länger bleiben. Ich möchte dich kennenlernen.” [ Fine. But let me stay a little longer. I want to get to know you.]

“Natürlich.” [ Of course. ]

The tension dissipated.

“Du hast gesagt das du lasst Medical dein Gesicht nicht sehen. Erlaubst du irgendjemand?” [ You said you don’t let medical see your face. Do you let anyone else? ]

Your brother flushed. He really was quite pink under the hood.

“Einer.” [ One person .]

You mentally rolled up your sleeves. You had over two decades of little sister pestering to make up for.

“Echt?” [ Oh really? ]

“Ein Freund.” [ A friend. ]

“Ein Freund oder dein Freund?” [ A friend or your boyfriend? ]

“Ich liebe ihn.” [ I love him. ]

“Gefühl er gleichartig?” [ And does he feel the same?]

“Ja.” [ Yes. ]

“Na ja, ich muss sehen, ob er gut genug für dich ist.” [ Hmm. I’ll have to see if he’s good enough for you. ]

He slumped in relief. With a jolt you realized he was afraid of you… rejecting him. For what? Being in a relationship with another man? No, you of all people would never do that. You silently resolved to make sure he would never have to fear that ever again.

“Du kannst ihn heute Abend in der Kantine begegen.” [ You can meet him in the mess hall tonight. ]

----------

The mess hall is awash with activity. Even here amongst allies and coworkers, people gave König a wide berth.

“Welcher ist er?” [ Which one is he? ]

König pointed to a man sitting alone at a table.

“Dieser.” [ That one. ]

“Noch ein Maskenträger? Bisschen narzisstisch, ja?” [ Another mask? Bit narcissistic of you, isn’t it?]

You felt your brother roll his eyes under his hood. The sitting man’s head jerked up at the sound of his heavy footsteps. His mask already pulled up over his mouth to eat, the man broke out into a brilliant smile.

“Das ist der Horangi.” [ This is Horangi. ] König introduced. “Klarname Kim Hong-jin.” [ Real name Kim Hong-jin. ]

“Sprecht er Deutsch?” [ Does he speak German? ]

“Ja.” [ Yes. ] Horangi responded. “Er war mein Lehrer. So wurden wir unzertrennlich. Du bist seine Schwester, ja?” [ He has been my tutor. It’s actually how we got close. You’re his sister, right? ]

“Richtig.” [ Yes. ]

“Does she speak English?” Horangi asked your brother, switching languages. You knew it was just a way to test your skills, but it irked you.

“I’m American.”

“Just because you’re American doesn’t mean you speak English. I don’t even know if half the stuff that comes out of Graves’ mouth even qualifies as human speech.”

“Graves?” you looked to your brother for explanation.

“Er ist—wie sagt man das? Yee-haw?” [ He is… how do you say it? Yee-haw? ]

“Südstaatler?” [ Southern? ]

“Geneau.” [ Exactly. ]

You crossed your arms and gave Horangi a final thorough look-over.

“I approve under one condition.”

“Yes?”

“Teach me how to fight. It’s great that I was able to meet my brother but I do not want a repeat of the kidnapping.”

Horangi cocked his head, “Wouldn’t you want to learn from your brother?”

“There are plenty of things I want to learn from him. This is not one of them. Based on size alone, we’re going to have very different strategies. I’m sure he’s a great fighter, but I have a feeling that using his technique with my frame would be… lackluster. No offense.”

“Kein Problem.” [ None taken. ]

“Very well,” Horangi relented. If this was all it took to be on the good side of his in-laws, it was a small price to pay. “I expect to see you at 7 sharp. I won’t go easy on you.”

“Perfect.”

----------

Horangi’s right. It’s not easy, but slowly and steadily—and with no small amount of tears and blood—you managed to win Horangi’s respect (and a nice set of abs).

About a week in, he makes a suggestion. You two were on a water break, your brother was sitting nearby. König had taken to watching your sparring, occasionally commentating or tagging in.

“Du verbesserst!” [ You’re improving! ] the Austrian complimented brightly.

“Und ich habe gar nichts mit es zu tun.” [ And I had absolutely nothing to do with the matter, ] Horangi muttered with mock resentment.

“Unsinn, du bist immer ein prima Lehrer.” [Nonsense, you are an excellent teacher.] König apologized with a kiss.

“Wirklich! Vielen Dank.” [ Definitely, thank you so much! ] you corroborated.

Horangi shifted. Even in training, he still wore the mask—at least while in the base’s general gym. He was more lackadaisical about it in private. Your “family dinners” with him and König had given you a good look at both of their faces.

You’d become well versed in his facial reactions. Even with his face covered you could feel his devilish smile.

“자기야, du solltest ihr deine erste Liebe vorstellen.” [You know babe, you should introduce her to your first love.]

Your head snapped to your brother. Sans Horangi, you were probably the person on base who he felt most comfortable talking about his past with, but even then it sometimes felt like pulling teeth. You quickly learned to treasure any lore you gleaned.

“Was? Warum habe ich noch nie von das gehört?” [ What? How have I not heard of this before? ]

König raised his hands in defense.

“Das stimmt nicht. Er verhohnepipelt mich.” [ It’s not like that. He’s making fun of me. ]

“Wer ist diese erste Liebe dann?” [ Who is this first love then? ]

“Scharfschützen.” [ Sniping, ] he replied bashfully.

----------

After much cajoling, you finally got König to teach you to snipe. You had a good feeling about it. You always had a steady hand and good hand-eye coordination. Before the kidnapping, you’d even been looking into specializing in surgery (though now—whenever you’d return—you’d be taking a hard turn into emergency medicine and the other subjects required for a combat medic). Plus maybe it ran in the family.

You met at the shooting range one early morning. Horangi had recently been deployed and your brother needed to stop stressing about it.

“Ich wollte ein Heckenschütze sein.” [ I wanted to be a sniper, ] he explained as he showed you the mechanics. The assembly of the gun soundtracked his words with rhythmic clicking.

“Du bist ein Insertionsspezialist, ja? Was passiert?” [ You’re an insertion specialist, right? What happened? ]

“Zu groß. Das wird kein Problem für dich.” [ Too tall. That won’t be an issue for you. ]

You crossed your arms. Cheap shot. König didn’t notice your disapproval, eyes now trained on the target.

“Auch ich zappele.” [ And I fidget .]

“Ich habe dein Scharfschießen gesehen. Du hast eine feste Hand.” [ I’ve seen you shoot. You have a steady hand. ]

“Hände kann ich ruhen. Alles anderes, nicht so viel. Problematisch, wenn man unauffindbar sein muss. Erinnern: Drück, nicht zieh.” [ I can keep my hands steady. The rest of me, not so much. A slight issue when trying to be undetectable. Remember, squeeze don’t pull. ]

BANG

Bullseye.

“Du bist dran.” [ Your turn. ]

You approached the marked spot. This seemed so much easier before you felt the gun in your hands and witnessed your brother’s expertise first hand.

“Hol drei tief Atemzüge. Großer letzter Ausatmen. Das ist der Moment. Beacht Folgemaßnahmen, Rückstoß ist eine knifflige, besonders bei deiner Größe.” [ Take three deep breaths. Big exhale on the last. That’s when you want to shoot. And remember to follow through, recoil can be a bitch, especially at your size. ]

Even with your nervousness, you still found it in yourself to retort.

“Nennst du mich kurz?” [ Are you calling me short? ]

“Für mich seid ihr alle kurz. Das ist nichts speziell. Schussbereit!” [ You’re all short to me. There’s nothing special about that. Position! ]

The gun was heavy, but thanks to your work with Horangi not unbearable.

One.

Two.

Three.

Even watching your brother’s demonstration hadn’t prepared you for just how loud the gunshot was.

You flinched. Hard.

The bullet went left, landing in the dirt with a small puff.

“Scheiße.” [ Shit. ]

“Gute Form. Ohne dein Zucken, wurdest du ins Schwarze treffen. Du musst nur an dem Krach passen. Probier es noch mal.” [ Good form. If it wasn’t for the flinch you would’ve got it dead on. You just need to get used to the noise. Try again. ]

You were still rattled, but your brother’s confidence in you steadied your hands.

You knew you could do it, you just had to…

Eins.

Zwei.

Drei.

There was no dust cloud this time. Only the noise of the round hitting something solid and your brother’s exhilarated whoop as he took you in his arms.

----------

Saying goodbye was rough. Both König and Horangi joined you on the ride to the airport, wanting to prolong goodbyes for as long as possible.

“Bis bald.” [ See you soon. ]

When your flight finally touched down and you returned to finish med school, it was with a few training bruises, an even steadier finger, and a determination to help your new family the only way you knew how.

An explanation of König & Reader's full names and the historical references behind them

#konig cod#könig#konig#platonic König & reader#platonic konig & reader#korangi#cod#call of duty#körangi#konig x horangi#könig x horangi#fic#fanfiction#die Prinzessin series#die prinzessin au#die prinzessin#cod mw2#modern warfare reboot#sibling!reader#sister!reader#konig sister!reader#könig sister!reader#konig & reader#könig & reader

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

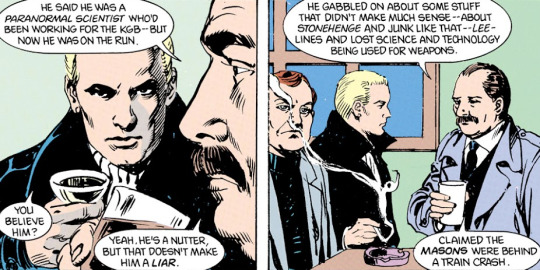

Hellblazer Issue #20

Welcome back, ya’ll.

So, the cover is once again beautiful. I would love to have posters of some of these.

Ahh, Merc further buttering up Dr. Fulton by calling him by his first name. He’s so creepy, but she’s handling it great. Getting him arrested and getting away. Very smart, very brave.

Normally, I feel like kid characters are not well written and therefore are often written all the same; annoying and shallow. But I do like Merc.

Gettin’ into it now. Once again, if the Masons aren’t mentioned then it isn’t a paranormal conspiracy theory, is it?

“ВНЕБ��АУНЫЙ!” seems to mean "bastard!" Though, I'm not sure that this is the right way to use it. In English, words that would be used as an insult might not be used the same way in other languages. Calling someone a bastard might be a major insult in a fight in English, but a different word might be used in that context in Russian. It might still be an insult, but not often used, or something like that. Cultural and historical things play a big part in this. In other words, instances like this can easily expose someone who isn't familiar with Russian language when it comes to everyday/natural use. Like when people translate things too literally or use Google translate.

To be fair, I know very little about Russian. We covered a bit about it on a technical level in one of my linguistics classes, but Slavic languages weren’t my area of concentration.

“ПРЕДáТЕЛЪ.УБИЙЦА. “ seems to mean “Traitor! Killer!”

This man did what I’m sure dozens of people have wanted to do to John. Should we call it a “public service” as opposed to an “unprovoked assault”?

So things are coming together now. It’s becoming very apparent that pretty much everyone in the project except for the few in charge have absolutely no idea what the end game is here. Somehow, I’m not surprised.

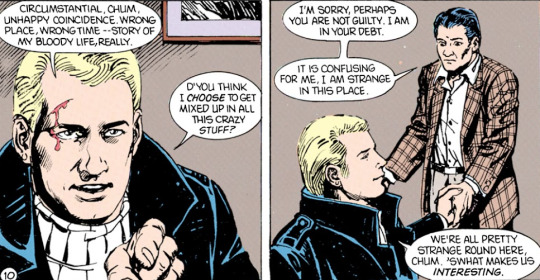

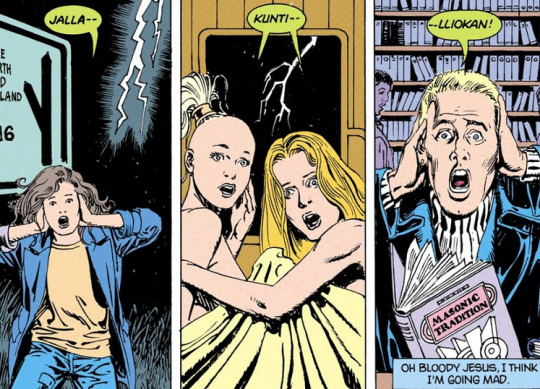

I have often wondered what the meaning of Jallakuntilliokan is. It could be just random syllables, but something tells me that it could be derived from something else. Considering Delano’s attention to detail, it wouldn’t shock me. If anyone has any ideas, please let me know.

According to Google Translate, "magi caecus dominari" means "blind sorcerers rule".

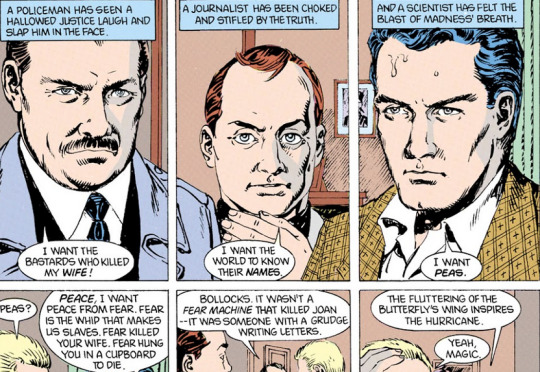

John here spittin’ the truth.

Now, unlike a lot of incarnations of John where he just springs “magic is real, lemmie show you!” on people, here we see him introducing the concept pretty slowly. It’s matter-of-fact, it doesn’t belittle anyone, and he doesn’t make a big show of it like some sort of stage magician (no offense to Zatanna, who is actually a magical stage magician). THIS is one of the things I love about Delano’s era. He makes John realistic by making his world, in many ways, realistic. People who subscribe to magic as a reality rarely just pull a magic circle out of their bum and start casting spells. He introduces it almost as a philosophical concept.

Got this fun little group here. Almost feels like a classic mystery now.

Beyond this point things pick up with a murder, a kidnapping, and...another murder. God, watching the kid get strangled....0/10.

I am...having flashbacks to Scooby-Doo again. Ya’ll see it too, right? No?

Words/phrases I had to look up:

Doo-Lally- deranged or feebleminded

Plod- walk doggedly and slowly with heavy steps. In context, I think he’s referring to a beat cop.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reviews as an Art Form

Back in the day when I had more time and patience, I used to review every Horrible Historical Novel I could find, which grew to a rather daunting task, since most HF of the past ten years churned out by American and a few British scribblers is utter crap. I do not want to compete with Dear Citizen Pixel, and I can't begin to hold a candle to her reviews, which are replete with charm, information, wit, and excellent analyses on many levels.

But if you are interested in pure historical demolition and snark of steroids, then look no further. I'm posting a review I did in 2015 of a book set during the apparently popular 1803 pre-and post Treaty of Amiens era, full of brave, intrepid British spies and dastardly French of any stripe. So pour a glass of wine and settle back. This will take a while. Killing the Bee King

PJ Royal [now re-issued with the author’s name as Jaymie Royal. Either way, she can’t write. And she owns the publishing company, Regal Publishing.]

My Review:

What’s not to like about a massive, 530-page tome with a cast of notables on both sides of the English Channel, not to mention spies, secrets, beautiful women, cunning politicians, a youthful former prime minister, and a choleric emperor? In a book so lengthy and complex, although it covers just two months, November and December of 1803, what about the history portion in this work of historical fiction? The author assures us in her blog dated September 29, 2012, that “Every aspect of the book that could be historically accurate…was.” And she says in another blog dated June 16, 2014, that she has provided “…a historical environment saturated with authentic detail that lends a vibrancy to the narrative without weighing it down unduly.” She includes a prologue for the book entitled “Historical Background: An Optional Read. England and France, November 1803,” to set the stage for the events in the novel. At the novel’s end we find an “Epilogue: The Historical Record,” where the author reminds us that she “sought to maintain the highest degree of historical accuracy throughout the course of this novel—from plants and architectural façades, to fashions, to food-stuffs. Many of the characters contained herein are historical figures, and their depicted appearance and personalities were also based on extensive research.” She admits, however, allowing herself the “fictional tweak” of placing Napoleon’s “self-coronation as emperor” in 1803, rather than in December 1804.

I quoted the author’s claims concerning the historical accuracy of this book because with so much insistence on accuracy, from plants to people and all points between, I was appalled at the extent of errors from first to last, big ones, little ones, and middling ones. Anyone with a scintilla of knowledge about the Napoleonic era, from the establishment of the Consulate in November 1799 until Waterloo in June 1815, would see them at once. No amount of pretentiousness, no faux literary prose as thick as treacle and as false as saccharine can disguise these bloopers. No pretending that this is some great literary work with its tortured, turgid sentences, images, metaphors, and other linguistic jetsam and flotsam clogging every paragraph and page can disguise the fact that the history is unrecognizable. The standard argument offered by some authors and fans of their work that “It’s only fiction!” or “That’s why it’s called historical fiction!” cannot logically prevail when the author makes such a concerted and repetitive case for her accuracy. Worse, I think, is the disservice done to readers who believe they’ve been treated to “the real story” not only with regard to historical events and people but also to the respective social and cultural milieu. I noticed that most reviewers have mentioned the “meticulous research” and the “mammoth amount of research” that allegedly went into this book without, unfortunately, understanding how very flawed on so many levels the history actually is. They were all swayed by what they believed was a fine literary style and use of language.

You have no obligation whatever to believe me or accept my opinion, and you certainly don’t need to read this review. However, this novel has 108 chapters bookended between a prologue and an epilogue, and every chapter has at least one or more errors of historical fact, language, social convention, political usage, or even physical location—I’d never before used the Notes/Marks feature on my Kindle as much as I did for this book. Thus I’ll cite concrete examples from the book, and you are free to decide whether you care that the author’s claims of accuracy cannot be sustained.

Let’s begin with the “Historical Record.” Right out of the box we get the mangled “Armée d’Englaterre,” apparently the author’s phonetic version of the correct French “Armée d’Angleterre.” Then we have the old canard of ‘“A nation of shopkeepers,’ Napoleon derisively said,” when the quote comes from Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Section vii, published in 1776 This is followed in quick succession by references to “the English Isles,” and how Britain was facing her greatest challenge while she was “bereft of allies.” Apparently the author forgot to notice that Britain declared war on France on May 18, 1803, so the alleged lack of allies must not have mattered too much. However, for those who care, Britain had already laid the groundwork for the Third Coalition with Austria and Russia, with Sweden joining the next year.

The “Cast of Characters” also provides an occasion for mirth, and a bit of head-scratching. There’s Wolfe Trant, the Irish rebel supposed to be Wolfe Tone, leader of the United Irishmen, but since Tone committed suicide in 1798 while in a British prison, I guess his doppelgänger Trant carries on here in ghostly form. Malcolm Dundas is the substitute for Henry Dundas, who was one of William Pitt the Younger’s advisors and minister or war for a time, but under no circumstances would Dundas call Pitt “Will,” and Pitt would never address his subordinate as “Mal.” I forgot—one would actually have to know something about these persons in real life, and about social conventions of the time, to know how wrong that is. My favorite is General John Moore, who the author claims “served in the Seven Years’ War and the War for American Independence.” She also alleges Moore was in at least twenty-four battles/engagements/skirmishes, many of them in and around Charleston. Moore was a young lieutenant during the American war, but he spent most of the time in Nova Scotia, with a couple of forays as far south as Maine. However, since he was born in 1761, and the Seven Years’ War ended in 1763, I suppose Moore’s involvement was limited to waving his rattle at the enemy. William Brunskill was no more a “school friend” to William Pitt than he was the “warden of Newgate Prison.” He was the official executioner of London—executions there were carried out at Newgate—and of Middlesex and Surrey.

The villain of the piece, of course, is Napoleon—isn’t he always? Here he is “the self-appointed emperor of the French,” which ignores the May 14, 1804, Senatus Consultum naming him emperor, or the national plebiscite confirming it. Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, often referred to throughout as the “duc de Talleyrand,” which is wrong on many levels, is supposed to be conspiring with the British to overthrow Napoleon because he is “disillusioned with Napoleon’s self-aggrandizing strategies,” a claim as factually incorrect in 1803 as is Talleyrand’s title. Joseph Fouché was not Napoleon’s “commissioner of police”—this was Paris, not New York, and the correct title was minister of police. Finally, we are presented with Jeanne Récamier, Parisian “society hostess,” traveling under the alias of “Primrose” as one of five leaders of the “French Resistance.” I truly feel sorry for the real Mme Récamier, a beautiful if somewhat emptyheaded woman who hosted salons from time to time, didn’t much care for Napoleon, but never lifted a perfectly manicured finger against him, to be portrayed in such a silly and implausible fashion. The worst part, of course, is this alleged “French Resistance,” a term used exclusively during WWII, and never at any time to denote opposition to Napoleon. Quelle horreur!

The author admits she “tweaked history” to place Napoleon’s coronation as emperor —or self-appointment to the position—in 1803. She never explains why, not that it matters, because all the history that flows from the decision to place the action of the novel in November and December 1803 is just wrong. All of it. I have an embarrassment of riches to choose from to illustrate what is nothing more than Bad History, something easily avoided by an eighth-grader spending three hours with Wikipedia. This author’s alleged ten years’ worth of research was time wasted.

A number of events occur during these last two months of 1803 that didn’t occur in the real historical world at this time, or even close. A group of Chouans, supposedly led by Georges Cadoudal, attempted to assassinate Napoleon by blowing up a barrel filled with gunpowder. Cadoudal ordered a number of assassination attempts, but he did not plan or participate in this plot, known as the Infernal Machine, which occurred on December 24, 1800, when First Consul Bonaparte was on his way to the Opéra. The seminal event leading to the establishment of the First Empire was the execution of the duc d’Enghien at Vincennes on March 21, 1804, not December 13, 1803. The duke was extradited—or kidnapped, if you prefer—from Coblenz on the Rhine, and not from his fiancée’s house somewhere in Switzerland. Talleyrand was minister of foreign affairs in 1803, and not plotting to overthrow Napoleon or, more historically correct, First Consul Bonaparte; he was most assuredly not Prince de Bénévente [1806], vice-grand elector [1807], or referring to Napoleon as dung in a silk socking [1808]. Napoleon did not assume the Iron Crown of Lombardy until May 1805. By November/December 1803 it is quite incorrect to say that thousands and thousands of men had perished under the Napoleonic regime—the only battles fought since Bonaparte became first consul in November 1799 were Marengo in June 1800, Hohenlinden in December 1800, although that was Moreau's battle, and in Egypt between the British and the remnants of the French army in 1801. Similarly the claim that men in their thousands—have to love the hyperbole here—were mutilating themselves to avoid conscription is false in 1803, but true to a much smaller extent after 1812. All the fatuous mentions of campaigns in Poland [1807], or the Imperial Guard having served loyally in more than twenty campaigns by the end of 1803 and earning the sobriquet of Les Grognards, are beyond belief. Thus the author did not “tweak” one bit of history—she mangled the entire historical narrative.

Remember that there is more to this novel than mere history—there are all those wonderfully accurate bits about “food-stuffs,” and “architectural façades,” and plants and fashions, right? Well, not at all. Here are just a few examples in the “food-stuffs” category: One did not begin a formal dinner with duck breast, no matter if it is sautéed; eau de vie is a colorless brandy made from fruit and not cognac from Brodiers; and there is no such thing as a “bottle of local kir,” when kir is made by combining crème de cassis and white wine and served in a glass as an aperitif, but not until the 20thcentury. [I just made myself a glass of kir royale, with champagne rather than white wine, so I can finish this review.] With regard to plants, it is certainly not true that the streets of Paris were lined with beech trees—those grow in northern forests for the most part. The streets were and are lined with plane trees, sometimes known as sycamores. Fashions don’t fare particularly well, either. The Duchess of Devonshire, le dernier cri in London fashion, is shown wearing what can only be described as an Ancien Régime style in 1803, while the female aristocrats gracing Talleyrand’s gatherings wear “stiff brocade.” There are also “elegant fashions behind gleaning glass” in a shop on the “Rue Fliette.” Well, no. Bolts of fabric, perhaps, but not ready-made dresses, and not on a street that does not—or did not—exist, at least spelled that way.

The world of architecture, whether in the artistic sense or as specific real estate is equally risible. Andrea Palladio had no more to do with the Tuileries Palace than Frank Lloyd Wright—the palace was the creation of Philippe d’Orme, with nary a trace of “neoclassicism.” Some forgettable character, an aristo named Adelaide, complained to Talleyrand about having to move out of the Louvre because Napoleon was turning it into an art museum. The fact is that the National Convention declared the Louvre to be a museum for the citizens of Paris on August 10, 1793, to coincide with the anniversary of the fall of the monarchy; the Directory added to the artistic treasures in the museum; it was closed for repairs from 1797 until 1801, and reopened with lots of new items from the First Italian Campaign and the Egyptian Campaign. So where Adelaide actually lived is indeed a mystery. Joséphine de Beauharnais’s house on the rue Chantereine was never “confiscated” by Napoleon before or after they were married, it never was in such a state of disrepair as the author claims, and it was never, ever used as a meeting place by the members of the alleged “French Resistance.”

This last architectural tidbit is so wonderful that it truly deserves its very own paragraph. The alleged spy Wolfe Trant/Tone/Whatever is fleeing from the Bad Guys through streets in Paris—many of which are misspelled, misnamed, or non-existent in 1803, as they are throughout this novel—and arrives at the Hotel de Ville, a “slightly disreputable establishment that rose pompously from the banks of the Seine. It overlooked the Place de Grève…that lately served as the home of Madame la Guillotine….Despite the notoriety of its location, indeed perhaps because of it, the hotel was immensely popular. It offered cheap rooms….” It scarcely matters that the guillotine was not anywhere near the Place de Gréve but at the Place de la Révolution further west. What matters is that this “hotel” didn’t rent rooms—it was the City Hall of Paris, and had been, in that very location, since 1357. In fact, every city hall in France, no matter the size of the city, town, or village, is called the Hôtel de Ville. And not one of them, large or small, rents rooms for anything other than the occasional civic gathering. Mon Dieu!

Just a few more jewels—or cubic zirconia, in this case. The author claims two people reviewed her use of French. I hope they didn’t charge for the service, since this novel is replete with errors, either in the use of words like lorgneurs instead of lorgnette, not knowing that “rue” is never capitalized, failing to distinguish masculine and feminine noun/adjective endings., and so forth. Although she didn’t say she had a firm historical grasp on social interactions of the time—the two months in 1803—I’d say the author missed that lesson completely. I already pointed out that Pitt and Dundas were not, nor would they ever have been, on a first-name basis. Lady Hester Stanhope, Pitt’s niece, would not have addressed Dundas or Wolfe Trant/Tone by their Christian names or asked them to call her “Hester.” Even more egregious, I think, is having Lady Hester say, “He is bloody miserable!” or “No bloody end!’ I do not believe any of us can imagine the Duchess of Devonshire, at a gathering in her London home, walking up to a guest and saying, “Allow me to introduce myself. I’m Georgiana….” And finally, there is the matter of William Pitt the Younger, standing in “the pulpit” of the House of Lords and reading a letter about the Irish Question. Pitt was not a peer of the realm, and therefore spoke only in the House of Commons.

There is so much more, folks, at least twice as many truly amazing examples of sheer awfulness as the ones I’ve highlighted here, but I’m done. I’d be surprised if anyone actually reads through this review. But I feel better for having written it , because there is nothing I loathe more than someone trumpeting about his/her historical accuracy in a period I know very well and producing instead a veritable welter of arrant nonsense. And what I detest the most is that readers often believe that it’s all true because they are told that it is.

--Reviewed on Amazon and Goodreads in August 2014, and removed in September 2019 when I pulled all my reviews because of some unpleasant incidents of doxing and stalking.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

So recently I’ve been interacting with activists in South Africa who are pushing for more decolonized conceptualizations of traditional African society and history and one of the things they were talking about is the separations of peoples into certain groups which doesn’t have any traditional precedent, specifically the separation of African peoples into three major groups.

The three groups have been historically called lots of things but most modern bodies of work will use the terms “San, Khoena (or Khoekhoe) and Bantu-speaking peoples”.*

These terms are problematic because they project colonial understandings of “race” and “ethnicity” onto something which doesn’t easily ascribe to either idea. The prescribed differences between the 3 groups are: The San are stone age hunter-gatherers, the Khoena are stone age hunter-pastoralists and Bantu-speaking peoples are iron age agro-pastoralists.

This is a major oversimplification of their relations and the purposes of this oversimplification is far more nefarious then it might seem at first glance.

Firstly, let’s talk about the relationship between the “San” and the “Khoena”. The “San” have lived in South Africa for approximately 44,000 years. They aren’t one singular group so much as several disparately related hunter-gatherer communities, the (near) full extent of which can be seen in this map below:

I say near full because there were “San” communities in the Western Cape and other locations throughout South Africa who’s existence has been recorded but only in the sense of being “pests” in the eyes of colonial governments and so their culture and language has been lost to the annals of time. (Also this only the South African “San”

The “Khoena” on the other hand possibly could have arrived around 2000 years ago and are similarly not a homogenous group. Now if you read the conclusion of the article, you’ll see that “arrived” is a reductionist term, so to speak. And this is where the first problem in dividing these peoples rears its head. How do you cleanly and neatly differentiate the “San” and the “Khoena”? Two issues stop this question from being easily answered:

1) Firstly there’s the language issue. The languages of both of these groups of people were grouped under the umbrella of “Khoisan”, first as a ethnic group by German Zoologist and organ harvester, Leonhard Schultze-Jena, then codified as a linguistic unit by less abhorrent person Isaac Schapera and then popularized as one of the four African language families by Joseph Greenberg. As you can see, none of those names are remotely African and the term is traced back to a man who harvested the organs of dead “Khoekhoen” and “San” who had been killed in the Namaqua-Herero genocide. Which is not a good start. This language family has been debunked as being artificial and is actually made up of 3 (or 4 depending on who you ask) separate language families, the families in question being: Khoe, Tuu and K’xa.

Here’s the interesting part - all “Khoena” languages fit into the Khoe language family. Okay so “all Khoekhoen speak Khoe languages and all “San” speak either a Tuu or K’xa language” right? I wouldn’t be making this post if that was the case. Out of the 11 listed languages on Wikipedia, only 3 of them (Eini, Khoekhoegowab and Khoemana) are/were spoken by the “Khoena”; the rest are/were spoken by “San”. So the difference between the “Khoena” and the “San” cannot be defined linguistically.

2) If it can’t be defined linguistically can it be defined genetically? Take a guess. But before I talk about that let’s go back to the whole “it’s reductionist to say that the “Khoena” arrived in Southern Africa 2000 years ago. The current theory basically is that cattle arrived in S.A from East Africa prior to the so called “Bantu migrations” and the assumption is that it was brought by small migrations of pastoralists from East Africa (see the link on 2000 years ago above for more details). These pastoralists intermixed with hunter-gatherers (“San”) to create a hunter-pastoralist (“Khoena”) culture (so they didn’t arrive as much as there was a meeting of cultures at that point). The thing is, the lactase persistence allele which is one piece of evidence used to argue this theory is not only present in all Khoe speaking peoples (i.e. both pastoralists like the Nama and hunter-gatherers like the Tshua) but it’s also present in both Tuu and K’xa speaking peoples although in lower levels (spoiler alert: It’s also present in Bantu-speaking populations at a higher rate than in Tuu speaking populations). So the difference between “San” and “Khoena” cannot be clearly defined through genetics either.

I could go into how culturally these groups had a lot of overlap too but I’d be treading over much of what I already have said and also I don’t have any good sources that goes into the culture of the various groups so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. But I think you get the point, neither “San” nor “Khoena” make sense as labels describing two separate peoples unless you want to stretch the word Khoena to also describe Khoe speaking hunter-gatherers but at that point you may as well throw the baby out with the bathwater.

I’ll post a second part at some point talking about why “Bantu speaker” also is not a coherent group as well as why this three tier splitting of people is much more insidious then it looks at face value.

*Older terms used include “Bushmen” for the San “Hottentot” and “Khoikhoi” for the Khoena and “Bantu” for Bantu-speaking peoples. All of these terms are slurs today apart from Khoikhoi which is a mishearing of Khoekhoe.

I would also like to say that San is an exonym given to them by pastoralist peoples which means “one who gathers”. There isn’t a word in any of their languages which describes them as a macro-ethnicity. Because they don’t view themselves that way.

#long post#very very long post#lillypad.txt#lilly talks about south africa#mx. gum#wurmd#idk if you'd like it but it's anthropology related so I thought you might...#God this is a long ass post

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I was wondering if you had anything on Y Gododdin 😃

hey! fellow gododdin enthusiast! what a delight

i presume this is a request for reading recommendations - i don’t know exactly what you’re looking for, or how accessible these will be, but i’ve tried to cover most bases here. i WISH there were more literary criticism, maybe there is in the welsh-language scholarship and i just haven’t found it?

it’s entirely possible that i will have missed some obvious things here, i’m mostly sticking to stuff that i personally have read. if something mind-blowing has come out since the last time i did gododdin reading then it’s not here, i’m afraid!

but enough disclaimers. on to the recs!

text and translation:

for a translation, i cannot recommend enough joseph p. clancy’s translation as found in the triumph tree: scotland’s earliest poetry, 550-1350, ed. t. o. clancy (1998). this is fantastic. it’s poetic, it’s a joy to read, and having used it as part of a deep read last year where i went through the welsh text in detail i am honestly AMAZED regularly at how well clancy handles the many translation issues that arise. it’s loose, and it doesn’t translate every single stanza unfortunately, but for the spirit of the poem you really can’t do better

that said, if you need another translation to check against/to fill in the gaps, i’d recommend kenneth jackson’s the gododdin: the oldest scottish poem (1969). it’s a prose translation, so it’s harder to use in conjunction with the text, but it’s pretty clear and accurate

text-wise... things get complicated. honestly, the best edition is probably still ifor williams’ canu aneirin (1938), in terms of faithfulness to the words on the manuscript page. (i also really enjoy his textual commentary, but it is in modern welsh so not accessible to everyone.) the major problem with it is that you are not going to get the stanzas in the order they appear in the manuscript - he reorders them into groups of perceived variants. this also makes it harder to distinguish between the A-text and the B-text. AND it means that the stanzas are not in the same order as in any of the translations!

if you can get hold of it, i really really think it is worth having daniel huws’ llyfr aneirin: a facsimile (1989). the introduction is SO useful for understanding the manuscript context, and it comes with gwenogvryn evans’ transcription of the book of aneirin, which you can compare with williams’ edition if need be to work out where a stanza actually goes.

there’s a conspectus of editions which i think thomas owen clancy put together but i cannot for the LIFE of me remember where it is - if you think you’ll need it, PM me and i’ll see what i can do

dating, textual criticism and historicity:

t. m. charles-edwards, wales and the britons, 350-1064 (2013), chapter 11 - this is from more of a historical perspective than a strictly linguistic/palaeographical/dating perspective, but it’s a really good general introduction and i definitely recommend starting with it. if you read nothing else, read this. this whole book is a godsend

t. m. charles-edwards, 'the authenticity of the gododdin: an historian's view', in astudiaethau ar yr hengerdd, eds. bromwich and jones (1978), pp. 44-91 - this kind of lays out the standard view which everyone has been deconstructing ever since. we don’t know anything about what’s going on with y gododdin, but at one point we thought we did know something and this was what it looked like

d. n. dumville, 'early welsh poetry: problems of historicity', in early welsh poetry: studies in the book of aneirin, ed. b. f. roberts (1988) - and HERE is the deconstruction! a pretty good overview of the issues with “knowing anything” when it comes to y gododdin

p. sims-williams, 'dating the poems of aneirin and taliesin', zeitschrift für celtische philologie 36 (2016), 163-224 - i don’t have any notes on this and haven’t read it recently, but i remember it being good (it’s sims-williams so of course it is). almost certainly contains linguistics, but is probably also written readably

o. j. padel, 'aneirin and taliesin: sceptical speculations', in beyond the gododdin: dark age scotland in medieval wales, ed. a. woolf (2013), pp. 153-75 - if you can stand linguistics talk, padel does his best to make it understandable here and gives a good overview of the linguistic arguments for and against suggested dates for y gododdin. this whole book is actually very useful

g. r. isaac, 'canu aneirin awdl LI', journal of celtic linguistics 2 (1993), 65-91, AND 'readings in the history and transmission of the gododdin', cambrian medieval celtic studies 37 (1999), 55-78 - DEEP IN THE TEXTUAL CRITICISM. honestly, my poor attention span means i find it hard to pay attention all the way through these two, but if you want a really in-depth look at the possible relationships between the A and B-texts of y gododdin, this is the way to go

historical discussion and background:

charles-edwards in wales and the britons chapter 11 again

j. rowland, 'warfare and horses in the gododdin and the problem of catraeth', cambrian medieval celtic studies 30 (1995), 13-40 - this is a pretty cool look at the role of cavalry in y gododdin and while i don’t agree with all of it, i think it’s really useful reading if you’re going for a historical take on the poem

p. m. dunshea, 'the meaning of catraeth: a revised early context for y gododdin', in beyond the gododdin again, pp. 81-114 - makes some ESSENTIAL points re the question of: is catraeth catterick? moreover, IS CATRAETH A PLACE?

c. cessford, 'northern england and the gododdin poem', northern history 33 (1997), 218-22 - a historical perspective on the poem with some very useful points, comparing the situation as sketched out in y gododdin with what we know of the area at the time

m. wood, 'bernician transitions: place-names and archaeology', in early medieval northumbria: kingdoms and communities, AD 450-1100, eds. petts and turner (2011), pp. 35-70 - a welcome look at the archaeological and place-name evidence for what was going on in bernicia as it changed from a brittonic to a germanic-dominated area. really useful to have in mind both when reading the poem and when reading more literary history

r. collins, 'military communities and transformation of the frontier from the fourth to the sixth centuries', in the same book, pp. 15-34 - pretty fascinating look at the earlier background running up to the time period depicted in y gododdin, and the possibility of continuity between the roman occupation of hadrian’s wall and the post-roman era there. useful social/archaeological perspective!

f. h. clark, 'thinking about western northumbria', in the same book, pp. 113-28 - an early medieval english perspective on the area at the time, useful for comparison and completeness’ sake

literary discussion:

ifor williams, lectures on early welsh poetry (1944) and the beginnings of welsh poetry, ed. bromwich (1972, 2nd ed. 1980) - THE CLASSICS. an old-fashioned, not to say outdated, viewpoint, but that’s because this is the guy who INVENTED the viewpoint back when it was new! even now there’s a lot of good stuff packed into these and ifor williams’ prose style is a real pleasure to read. not to be missed

a. o. h. jarman, 'the heroic ideal in early welsh poetry', in beiträge zur indogermanistik und keltologie, ed. meid (1967), pp. 193-211 - likewise somewhat old-fashioned now, but lays out the classic viewpoint well and makes some good literary points. it may also be worth reading the introduction to his edition/translation, aneirin: the gododdin (1988). (i don’t recommend using it as an edition because he conflates the A and B texts and renders the text into modern welsh - this means it reads very smoothly but is quite a bit further away from what’s on the manuscript page.)

h. fulton, 'cultural heroism in the old north of britain: the evidence of aneirin's gododdin', in the epic in history ed. davidson, mukherjee and zlatar (1994), pp. 18-39 - a pretty interesting read, about the mindset expressed in the poetry, its purpose and its construction

this isn’t lit crit but i’m putting in my favourite g. r. isaac quote from his article ‘gweith gwen ystrat and the northern heroic age of the sixth century’, p. 69: ‘Koch writes that the Book of Aneirin’s ‘immediate milieu is… not the Celtic Heroic Age, but the High Middle Ages’, as if the ‘Celtic Heroic Age’ were a period of comparable historical status to the High Middle Ages. This is not the case, however. A ‘heroic age’ cannot be the ‘immediate milieu’ of any literary production, a ‘heroic age’ cannot produce literature, because a ‘heroic age’ is itself produced through literature (taken in the broadest sense). It is a literary product. The Homeric epics are not the product of a Bronze Age Achaean heroic age, but vice versa. The Irish Ulster Cycle is not the product of an Iron Age, pre-Christian heroic age, but vice versa. And the medieval Welsh poems of ‘Aneirin’ and ‘Taliesin’ (and Triads, sections of the Historia Brittonum, and much else) are not products of a sixth-century North British heroic age, but vice versa.’

honestly there just is not nearly enough lit crit for y gododdin, in english at least, especially to explain cool shit that the welsh text is doing that isn’t visible in the translation, and/or things that could be subversive or ambiguous about it - so, i don’t know what your level of engagement with the medieval welsh text is, but if you’re curious, if you want to know more about what’s going on in a specific stanza (or which stanzas are extended puns), or just which things i’ve been dying to yell about all year, PLEASE message me and I! WILL! YELL!

articles which are almost certainly good and useful but it’s been too long since i’ve read them to say:

t. o. clancy, 'the kingdoms of the north: poetry, places, politics', in beyond the gododdin again, pp. 153-75

m. haycock, 'early welsh poets look north', likewise in beyond the gododdin, pp. 115-52

FINAL NOTE:

one of the problems with translations is that they give an impression of way more certainty about the meaning of the text... than is actually there. you’re pretty safe with clancy or kenneth jackson, but tread carefully. again, i don’t know your level of engagement with medieval welsh, but if you want to know if there are any major textual issues with a stanza, hmu and i will gladly consult my copious textual notes! but in general, BEWARE of basing anything too heavily on the following groups of stanzas:

A40, A41, B5, B6 (Am drynni drylaw drylenn; Clancy ‘For the feast, most sad, disastrous’)

A42, B25, B35 (Eur ar vur caer; Clancy ‘Gold on fortress wall’)

A48, B3, B24 (Llech leutu tud leudvre; Clancy ‘Standing stone in cleared ground’)

A62, B14, B15, B16, B36 (Angor dewr daen; Clancy ‘Anchor, Deifr-router’)

the Gorchanau if you’re interacting with those, especially the Gwarchan Maeldderw - if anyone tells you they know exactly what is going on in these, do not believe them. isaac has a full translation of the gwarchan maeldderw in cambrian medieval studies 44, and it’s useful, but i’m not by ANY means completely convinced by it, so tread carefully.

the more stanzas there are in a group of variants (or at least a group that shares lines), the more likely it is that those stanzas are going to be SUPER DUPER TEXTUALLY FUCKED UP, is a pretty good rule of thumb.

#y gododdin#cicely speaks#academic book recs#asnc things#I AM SO DEEP IN THE QUESTIONABLE ETYMOLOGIES AND SADNESS ABOUT DEAD YOUNG MEN#i have PAINFULLY detailed textual notes on this whole fuckin thing#behold my continuing love affair with ifor williams' prose in welsh and english#ANYWAY#hmu for GODODDIN YELLING#it may be yelling of sadness about dead dudes! it may be yelling of frustration about FUCKING SCRIBES!#who can say!#violetcancerian

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Japanese internet slang full of fish? - My washed-up linguistic theory.

A couple of weeks ago I was looking at a glossary of Final Fantasy 14 Japanese internet slang a friend had sent me, and I was struck by an idea: Japanese has a really wide lexicon of fish and fishing related words. Does Japanese internet slang also have more fish related words than English internet slang does? The idea made me laugh, and that was enough to want to try to pursue it.

The Japanese lexicon does, in fact, have a very extensive vocabulary related to fish and fishing. Masayoshi Shibatani (1990) wrote, ‘The vocabulary of a language reflects the cultural and socio-economic concerns of its speakers, and the Japanese lexicon is no exception to this truism.’ He explains that fishing was one of the primary socio-economic activities in traditional Japanese society, and therefore the native Japanese vocabulary has a great number of words and expressions relating to fish. Of course, we have a fairly wide fishing vocabulary in English as well, but Japanese goes into further detail. Shibatani gives examples of 9 different Japanese words for a fish that we would refer to simply as ‘yellowtail’ in all cases in English - in Japanese there are different words for it depending on its size.

Another wonderful piece of evidence of the abundance of fish words in Japanese is a 1940s ‘Glossary of Japanese Fisheries Terms’ that I found on the American National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Publications Office website. In March 1947, J. A. Krug, Secretary of the United States Department of the Interior and Albert M. Day, Director of the Fish and Wildlife service, published a leaflet titled, ‘Glossary of Japanese Fisheries Terms.’ It is a dictionary of fishing terms and names of fish, including both Japanese to English and English to Japanese translations.

The introduction reads, ‘Fish and fishing play such an important role in Japanese life that an extensive and complicated fisheries vocabulary has evolved. Each of the hundreds of kinds of fish, shellfish, and seaweed has several vernacular names, the wide assortment of prepared seafood adds many more words; and the variety of fishing gear has a large specialized nomenclature.’ Clearly, the vocabulary related to fishing in Japan was so specific that it didn’t do well enough simply to translate it to the closest English word - a specialised glossary was needed so that American fishermen could understand precisely what the Japanese fishermen were referring to. (If you, like me, are quite enamoured by historical, niche glossaries or dictionaries, you can read the Glossary of Japanese Fisheries Terms here.)

With this evidence that Japanese does have more words to do with fish and fishing than English does, I wondered if perhaps the extensive fish-related lexicon in Japanese affected the creation of slang terms, particularly internet slang terms. While there is no definitive corpus or complete dictionary of Japanese internet slang, several fish-related phrases came to mind. For example, 雑魚 zako, literally meaning ‘small fish’ is a commonly used phrase in casual Japanese which means ‘a wimp’ or an ‘unimportant person.’ This is also used in MMORPG (Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game, e.g. Final Fantasy 14) lingo to mean ‘low-level NPC (Non Player Character) enemies.’ Of course, we have the word ‘small fry’ in English which has essentially the same meaning of ‘unimportant person’, but we do not use it in the same context in online gaming. (I have been informed that in English we might call these weak enemies ‘trash mob’ or ‘slimes’ - a reference to the slime blob enemies in the game Dragon Quest.) I also recalled that 鯖 saba - ‘mackerel’ is slang for the word ‘server’ - a lovely wordplay on the loanword sābā.

I then asked on twitter if anyone could help me to come up with some more Japanese fish-related internet words. I had a few interesting replies, suggesting 釣り tsuri (fishing) which means ‘trolling’, accompanied with 釣り師 tsurishi (angler) for ‘troll’, and エサ esa (bait) and 釣り針 tsuribari (fishhook) , which both refer to the content used by a troll to entice other users into replying angrily. Although we might also call this practice ‘baiting’ in English, and we of course have the famous term ‘clickbait’ for baiting people into clicking a link, the metaphor is further expanded upon in Japanese internet language. When a troll gets the responses they were hoping for, other net users may say something like ‘大漁だな’ tairyou da na - ‘That’s a big haul.’

I was also told about ウェブ魚拓 webu gyotaku (web fish printing), which is a method of preserving the content of a website in a snapshot, like the service Wayback Machine. Gyotaku is the traditional Japanese practice of dipping a fish in ink to create a print, which could record a fisherman's catch they are particularly proud of, or simply make a nice picture of a fish. (Incidentally, the web address for the website where one can access webu gyotaku is ‘megalodon.jp.')

This is not an incredibly extensive list, but I was pleasantly surprised with the number of responses I received. I also tried to come up with a list of fish-related English internet terms, but all I could think of was ‘phishing’, ‘clickbait’, and ‘catfish.’ None of these are slang as such, but created terms for phenomena that only happen online. (They respectively mean, ‘sending scam emails’, ‘using sensationalised or misleading content to entice users to click on something’, and ‘pretending to be someone else on online dating sites.’) I suppose at a stretch I could actually include ‘the net’ into my list of fishing-related internet vocabulary.

I don’t, however, think that this is enough evidence to suggest that Japanese internet slang does indeed have a larger proportion of fish or fishing-related terms than internet slang in other languages. Furthermore, even if it did, it does not necessarily prove that it is because of the wide fish lexicon that Japanese has in general.

I think my next step would have to be to explore whether other aspects of the Japanese lexicon are reflected in the creation of internet slang terms. Shibatani also mentions that Japanese has an abundance of words to do with nature, but not many body part words. (Even a novice Japanese learner will have noticed that ‘foot’ and ‘leg’ are both expressed with one word, 足 ashi, and that both ‘smile’ and ‘laugh’ are expressed with the verb 笑う warau.)

The problem is, it is fairly difficult to linguistically analyse ‘Japanese internet slang’ as a concept, and to compare it to ‘English internet slang.’ There is no official online corpus of internet slang in English or Japanese, and it changes every day as new slang terms are created and older terms fall out of practice. The only way I can see to continue this research is to compile my own lists, either from spotting slang terms ‘in the wild’ online, or asking strangers on twitter to come up with any terms they can think of.

Even if I could prove that the tendencies of the Japanese vocabulary are reflected in its internet slang, what would this actually demonstrate? That, somehow, the balance of this lexicon is engrained in Japanese minds and so it affects the creation of new slang terms and wordplay? Or just that there are a lot of fish words so people create fish-related associations?

What kind of words are there more of in English than in other languages? Have we English-speakers developed a tendency to create internet slang based on… growing wheat… or… brewing… or whatever is that was traditionally engrained into English society, and therefore probably English vocabulary? Somehow, I don’t think so.

So, I was unable to come to a satisfying conclusion about my theory of fish-heavy Japanese internet slang. But I don’t think it was a complete waste of my time. It was my first foray into researching something just because I was curious and felt like it, and even though it didn’t lead me to any groundbreaking discoveries about the creation of new slang terms in Japanese, I had a lot of fun. It sparked some interesting conversations with friends and twitter strangers, and I got to read a 1940s fish dictionary. Some pretty good mental stimulation for a Wednesday afternoon in lockdown.

#japanese#linguistics#internet slang#internet linguistics#research#fish#fishing#misshanake#essay#japanese linguistics#japanese studies#slang#final fantasy#ffxiv#dragon quest

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pylon Bios (An Update, with New Pylons)

Hello, lovely followers of script-a-world!

Please allow us to introduce ourselves! We haven’t had any sort of about-the-bloggers page available before, and now that we’ve added more to the team, we’re seeking to remedy that!

First of all, we call ourselves Pylons. What the heck is a pylon? Well, outside of this blog, it’s an upright structure for holding up something, usually a cable or conduit. When this blog was started more than a year ago (whoa), the group chose the word Pylon to describe ourselves collectively, as a fun little nickname. Whee!

Without further ado, meet the Pylons (and Mods)! (in alphabetical order)

Brainstormed: Hey there, call me Brainstormed, and you can find me at @thunderin-brainstorm. Any pronouns will do. I'm a student, illustrator, and world traveler. My home is in America, but I'm rarely there for more than a month at a time, so feel free to ask where in the world I happen to be! Worldbuilding has been my hobby for quite a long time and I'd love to give you some tips and tricks that I've learned, or take your idea and turn it on its head to perhaps show you a new perspective. The many projects I've developed have been lifesavers for me, as they allowed me to harness my Maladaptive Daydreaming Disorder and use it as a positive tool for creativity. Aside from drawing and daydreaming, I spend a lot of time biking, hunting for cool rocks and bones, binge reading any scholarly article that catches my eye, and memorising completely useless random facts that I spout at any given moment in lieu of remembering actual important information.

___

Constablewrites: My name is Brittany, and I'm a California girl living in the Midwest. I use she/her pronouns. I've always loved stories with rich and detailed worlds, whether in movies, books, games, or something else entirely. I'm the kind of writer who will spend hours researching to confirm a minor detail. Naturally, I not only write SFF, but my recent projects have all required worldbuilding on more than one axis (like multiple types of magic, or time travel on top of historical) because i am apparently something of a masochist. I'm a walking TV Tropes index and a whiz at digging up random useful knowledge, both of which come in handy as a Pylon. Other random facts: I'm a trained actress and singer, I used to work at Disneyland on the Jungle Cruise (among other attractions), and a laptop held together with duct tape is responsible for my day job in tech support. I blog about writing as @constablewrites and about random things that amuse me as @operahousebookworm.

____

Delta: Hi! I’m Delta and I can be found @dreaming-in-circles or @thedeclineofapollo (writeblr), and I love sci-fi. Like, a lot lol. I work in NEPA compliance for a civil engineering firm in the USA, and have a lot of experience with infrastructure, bureaucracies, biology, and space (for unrelated reasons). I spend a lot of time haunting the astrophysics wikipedia pages, and my current all-consuming project is a novel that is angling to be about 150,000 words (at current projections). Can’t wait to hear your questions!

__

Ebonwing: Hi, I’m Ebonwing. I’m currently studying IT in university. I’m a writer and worldbuilder, and sometimes a worldbuilding writer or a writing worldbuilder. I gravitate towards fantasy, though I’m not going to say no to the occasional stint in scifi, and as I’m also a giant language nerd, I enjoy making conlangs for my creations. Other than that, I’m also an artist and indulge in any number of other crafting hobbies, and if I’m not doing any of those things, I can probably be found playing video games.

___

Feral: Hi! I'm Feral, and you can find me @theferalcollection (if you enjoy feminism, socialism, or over-analyzed fiction) or on my writing blog theferalcollection.wordpress.com. I'm a Southern girl who likes fancy dresses, mint juleps, big hats, and using being-underestimated to my advantage. I work in the interior design industry and am currently in school for industrial design. I have previously earned degrees in comparative literature and theatre & drama. I'm a big nerd who really likes school. I've been world-building since before I knew it was a thing and writing almost as long. I’ve written mostly fantasy but the past couple projects have been science fiction. I'm ridiculously in love with the idea of being an astrophysicist but don't feel like learning calculus, so I just read about science a lot. My hobbies include martial arts, drinking too much coffee, and tabletop games.

____

Lockea: Hello! I’m Lockea. You can find me all over the internet as @lockea or LockeaStone. I’m a leaf on the wind who currently enjoys the SoCal sunshine in Los Angeles where I work as an engineer and data scientist. I love street fashion (especially Lolita) and making jewelry. I have two kitties, Theodore and Cecelia, and I volunteer at the local animal shelter as a cat handler and adoption counselor. I know way too much about cat behavior, honestly, and will yap your ear off if you let me.

Worldbuilding wise, I have a deep affection for science fiction and I’ve consulted professional science fiction writers on developing technology and worlds through the explanation of science and engineering. My engineering specialization is extra-terrestrial robotics, so if it has to do with space, planetary science, or robotics -- I got you. I’m also a fan of politics and really like developing political and socio-economic systems in fantasy and sci-fi worlds.

__

Miri: Miri here, with my main tumblr @asylos and my writing tumblr @mirintala. I am a Canadian Pharmacy Technician by day and a small time ePublisher and gamer of many types by night. Mostly wandering around the Internet helping to organize events in the FFVII tumblr fandom (modding at @ff7central and @ffviifandomcalendar), and stumbling around within the Borderlands of Pandora. I use she/her pronouns.

—-

Symphony: Hey, I’m Symphony! Use whatever pronouns you feel like, any work. I’m currently living in Michigan with my fiance, and in-between jobs but I want to go to nursing school ASAP. My favorite genres in fiction are horror, sci-fi, and really anything that holds my interest. In my own worldbuilding I've always felt myself most interested in developing societies on the macro level (politics, diet, customs, stuff like that), and the more esoteric, strange parts of my world. I like to make a place feel lived in, with secrets that may never be found and people who seek them out.

——

Synth: I’m @chameleonsynthesis on Tumblr, but that’s a mouthful, so just call me Synth. Any pronouns work. Born and raised in Canada, but living in Norway as of autumn 2007. Looking back, I’ve been worldbuilding since at least the age of four (in my early thirties now, so yeah), with a predominantly science-fantasy bent. I’m of the artsy creative type, with way too many projects on the go at any given time, and enjoy long walks through Wikipedia and getting caught in TV Tropes. The best thing is when I stumble across some strange factoid that can justify aspects of my many weird alien species. Stupid Synth facts: I have dual Canadian and Norwegian citizenship. My legal name contains a letter that does not exist in the English alphabet. I can curl my tongue into a cloverleaf shape, and wiggle my ears. My day job is musical instrument repair. I play French horn in a concert band, trombone in a jazz band, and don’t practice my flute or piccolo near as much as I should. Outside of band rehearsals and my job, I volunteer at the local cat shelter, work out at a gym, and attend events at my city’s newly established makerspace.

__

Tex: I'm Tex, and you can find me on tumblr @texasdreamer01. Most of my hobbies are centered around fandom and worldbuilding for it, though I also like cooking and reading up on fiction and non-fiction whenever I have the time. I'm currently studying biochemical engineering, with a slant in nanotechnology and its medical applications, so I need to know a bunch about the different types of sciences, as well as projecting for the development of future fields.

-----

Utuabzu: Hi, I’m Utuabzu, I previously was part of ScriptMyth (RIP) where I tended to take the lead on Mesopotamia and Egypt related asks. I’m most of the way through a Bachelor of Linguistics, e parlo italiano und ein bisschen Deutsch. I have a deep and enduring interest in the history of the ancient world, particularly the ancient Near East, and I’m also a bit of a nerd for politics, which is helpful when it comes to worldbuilding. My random 2am research binges have resulted in my knowing a lot of odd things. I enjoy travelling and experiencing other cultures, however as I am Australian this unfortunately requires flying, which I hate a great deal. I expect to one day be crushed beneath a pile of my books. It is a demise I am ok with.

_____

Wootzel: Hi, I’m Wootzel, or @wootzel-dragon! I use she/her pronouns. I’m a recent college grad trying to figure life out. My favorite thing about worldbuilding is making things as realistic or pseudo-realistic as possible, and finding a justification for everything. Sometimes, this is also my least favorite thing about myself, because it can make things very hard! But, it can also be really rewarding when I get things to work out in a way that I enjoy.