Hi, I'm Alex (they/them) also known as runningondreams (or running) over on Dreamwidth and AO3. Here you can expect MDZS/The Untamed, SVSSS, Guardian, Discworld, life-consuming Bioware games (Dragon Age and Mass Effect) and some Star Wars, Star Trek and Marvel comics stuff, alongside history, literature, social issues, trans things and art. I also love talking about world-building and writing.My fic on Ao3 | My fic on tumblr My edits | My art tag | Fic recs About me Ask me anything

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

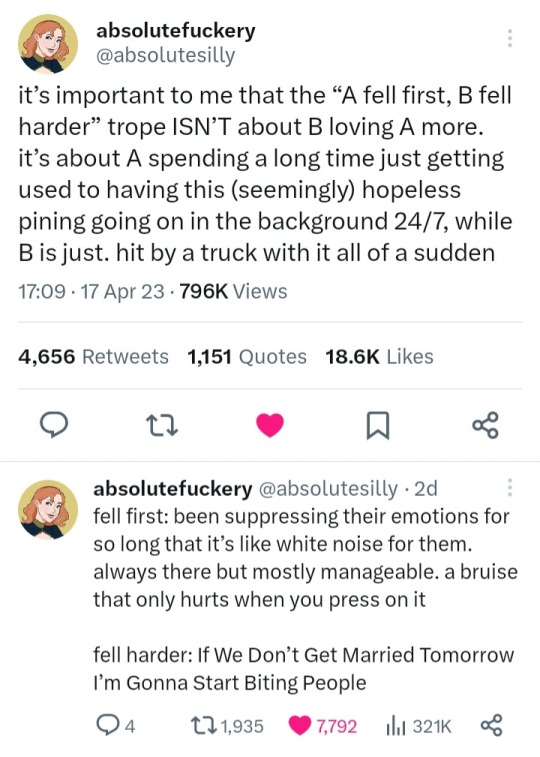

Text

I'm having a great time

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

So I've been playing Baldur's Gate 3

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

excerpt from in-progress "timebending with Zuko" fic

Zuko wakes up and everything hurts.

Most specifically, his scar hurts.

That . . . doesn’t make sense, he thinks, and reaches for it automatically. A strong hand catches his wrist before he can touch it, which seems–fair, yes. Probably a good idea, anyway, because spirits does it hurt. Just . . . so much.

“Uncle?” he asks reflexively, attempting to open his eyes. It’s surprisingly difficult. And Uncle is in Ba Sing Se, of course, but he’s on his back on a futon or bedroll or something similar and someone’s sitting beside him and his head is swimming and he’s injured, clearly, so options for who said “someone” might be are limited, really.

So it’s not Uncle, obviously, but . . .

“Nephew,” Uncle says, very quietly, and Zuko . . . blinks.

At least, half-blinks. The one eye’s in too much pain to open.

The ceiling is metal, he notes absentmindedly. That’s . . . odd. He was in the palace, wasn't he?

“What happened?” he asks, vaguely bemused. Uncle pauses in a very concerning way, and Zuko has about three heart attacks about just how badly he doesn’t want to know what he’s about to say before–

“The Agni Kai,” Uncle says, very carefully. “Do you remember it?”

Zuko frowns–just with the one side of his face, because again, his scar hurts right now. To the point that his whole body feels wrong, does his scar hurt right now.

“Um–which one?” he asks, because there’s been about a dozen this month alone, and frankly he’s getting really sick of fighting them at this point but if the old guard of nobles are just going to keep dragging everything out like this–

“With your father, Nephew,” Uncle says, very carefully.

Zuko . . . blinks.

“Oh,” he says, vaguely perplexed. Uncle never talks to him about that. “Yeah, I remember that. What about it?”

“Do you remember what happened?” Uncle says.

“The part where I disgraced myself or the part where he burned my face?” Zuko says, because it’s so fucked up and awful and horrible that he can’t even get upset about it anymore, except when he’s really upset about it. But if Uncle’s bringing it up, presumably he has a good reason to be, so . . . “Or the whole ‘go find the Avatar who no one even believes exists anymore or you can never come home again’ part?”

“. . . all of that, yes,” Uncle says, still sounding very careful. Zuko frowns a little–again with just the one side of his face–and then looks over at him. His body still feels weird and wrong, but . . .

But . . .

They’re on a ship, he realizes. A Fire Nation one.

Well, explains the metal ceiling.

It doesn’t explain why Uncle is wearing red armor and a topknot like he hasn't in years, though, or why he looks so unspeakably sad.

“Um,” Zuko says, and attempts to sit up. His head immediately starts swimming even worse, and Uncle catches his shoulders and keeps him pinned against the . . . futon? Looks like a futon, yeah. “Where are we, exactly?”

“We are aboard a ship,” Uncle says. “I . . . may have slightly commandeered it.”

“. . . you paid for it, right?” Zuko asks, a little skeptical at that idea.

“Yes, Nephew, I did,” Uncle says, giving him a very tired, pained smile. Zuko doesn’t feel much better, seeing it.

“Is someone dead?” he asks, because he can’t think of anything else that would make Uncle look that way.

“Ah–no, no one has died,” Uncle says.

“Then what’s wrong?” Zuko asks warily.

“. . . you are injured, Nephew,” Uncle says, slowly. Zuko frowns, bemused. “And your father . . . I did not know he was going to do this. I am so sorry.”

Zuko . . . pauses. Looks around the room again, and then realizes: he knows this room, doesn’t he. He knows this ship.

This is the same ship he woke up on after the Agni Kai.

“Hold that thought, Uncle,” he says, then lifts his hands and looks at them. They . . . well, they are his hands, obviously.

But they’re not his hands, obviously.

“Huh,” he says, frowning in bemusement at them; turning them around like he half-expects them to stop being a thirteen year-old’s or something equally ridiculous. They don’t. They are very definitely a thirteen year-old’s hands.

Specifically, his thirteen year-old hands.

Huh.

“You don’t have to be sorry,” he says after a moment, putting his hands back down and glancing back to Uncle, who’s obviously the more important concern. “It wasn’t your fault.”

“I took you into that meeting,” Uncle says, his voice tight. “And I watched the Agni Kai. And I did nothing to stop any of it.”

“I know,” Zuko says. “But it wasn’t your fault.”

“It was,” Uncle says, his smile a sad and terrible thing. “You were there because of my actions. My mistakes.”

“You’re not the one who wanted to sacrifice all those soldiers,” Zuko says. “Or the one who decided to throw fire at my face.”

“You were there because of me,” Uncle repeats, his voice tight and his smile no less terrible. It occurs to Zuko, briefly, that Uncle must be thinking of Lu Ten.

He only ever looks like that when he’s thinking about Lu Ten, so . . .

“Uncle,” he says. “Really. It’s not your fault.”

“Nephew,” Uncle says, and his voice is somehow even tighter. Zuko tries to get up again, and his head swims again, and Uncle moves to stop him again. This time he grabs onto Uncle’s wrists and uses them to pull himself up, and then . . .

Well, then he’s sitting up, at least.

So that’s something.

He tilts his head and his hair slips into his eyes. It’s loose, and long. Not shaved on the sides yet, like he wore it the last time he was thirteen. He supposes he should cut it, but then again, why should he? He's not changing anything, after all.

Except for this conversation, he supposes, because that went very differently last time.

. . . hm.

"Uncle," he says one more time, and reaches out for him. Uncle doesn’t seem to understand what he’s trying to do, so he has to reach out a little farther, and then Uncle makes the connection and leans in and lets him wrap his arms around him and alright, yes: that’s better, Zuko thinks, and clings to him.

Just a little, perhaps, but . . .

Yes. He clings to him.

Uncle wraps his arms around him in turn, very carefully, and makes an awful sound.

“My boy,” he chokes. “I’m so–I’m so–”

“I forgive you,” Zuko lies, because of course there’s nothing to forgive.

But of course Uncle doesn’t understand that, does he.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the day! I'm excited to finally be able to share the fantasy Qijiu that I did for the @qijiuzine The full zine is free and you can download it on the zine's page.

Their love is boundless and fated since primordial times ☀️❤️🍁

310 notes

·

View notes

Text

七九 Private Carriage

371 notes

·

View notes

Text

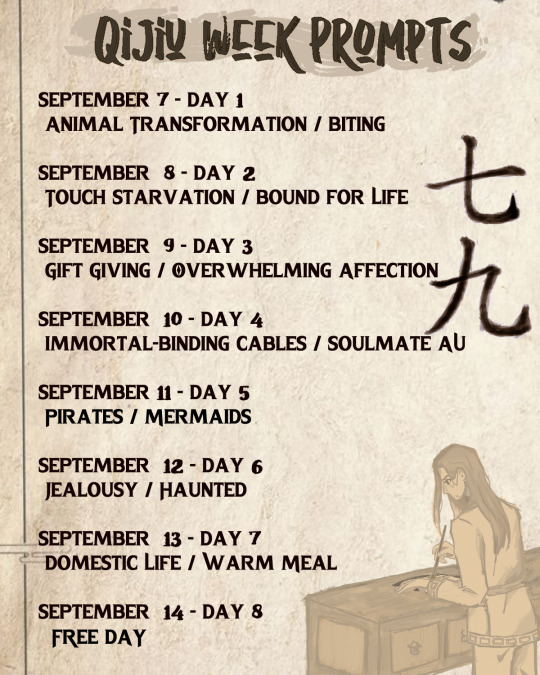

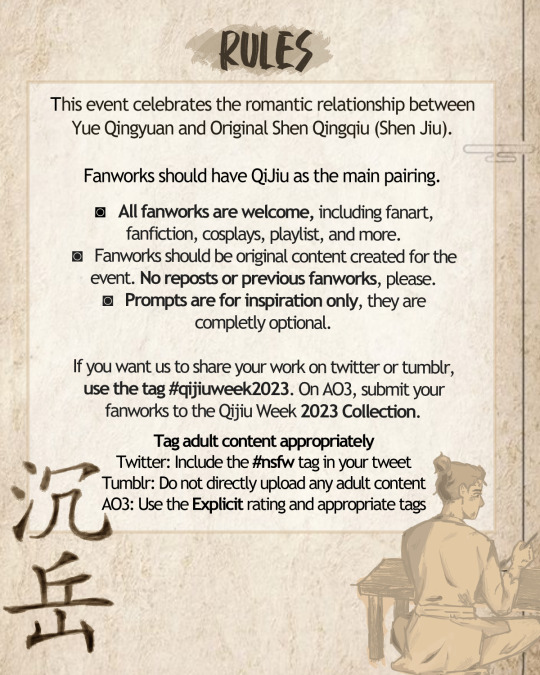

Qijiu Week 2023

A joyous July 9th to all! The prompts for #QijiuWeek2023 have arrived!

From Sept 7th to 14th, join us as we celebrate the love between Shen Qingqiu (Shen Jiu) and Yue Qingyuan.

For each day you can use ONE, BOTH, or NEITHER prompt as inspiration. The choice is up to you!

QIJIU WEEK PROMPTS Sept 7 - Day 1: Animal Transformation // Biting Sept 8 - Day 2: Touch Starvation // Bound for Life Sept 9 - Day 3: Gift Giving // Overwhelming Affection Sept 10 - Day 4: Immortal-Binding Cables // Soulmate AU Sept 11 - Day 5: Pirates // Mermaids Sept 12 - Day 6: Jealousy // Haunted Sept 13 - Day 7: Domestic Life // Warm Meal Sept 14 - Day 8: Free Day

RULES - This event celebrates the romantic relationship between Yue Qingyuan and Shen Qingqiu (Shen Jiu). Fanworks must have Qijiu as the main pairing. - All fanworks are welcome, including but not limited to fanart, fanfiction, cosplays, and playlists. - Fanworks must be original content created for this event. No reposts or previous fanworks, please. - Prompts are provided for inspiration. They are completely optional. - Use the tag #qijiuweek2023 if you want us to share your work on twitter or tumblr. On AO3, submit your fanworks to the Qijiu Week 2023 collection.

Tag adult content appropriately.

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

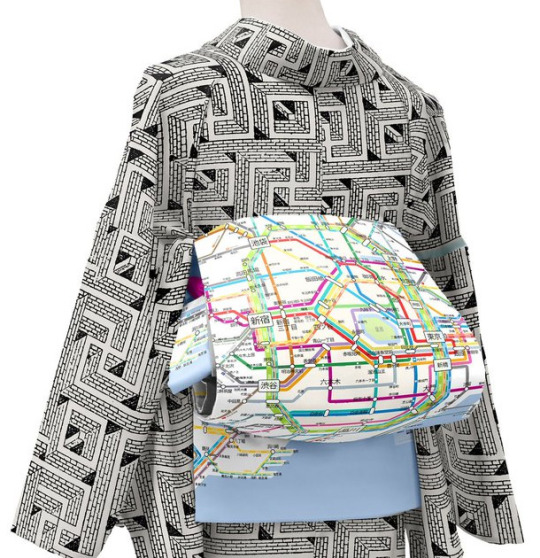

Obi and yukata by Gofukuyasan. Japan

887 notes

·

View notes

Text

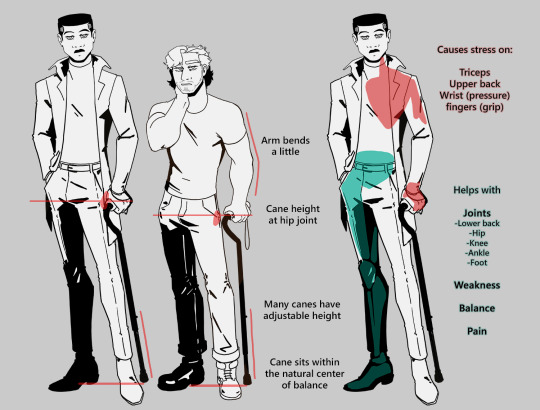

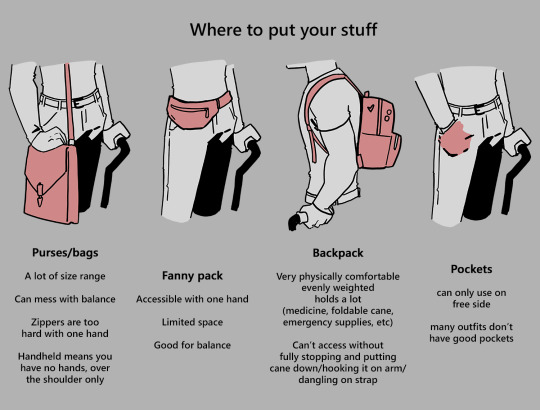

A general cane guide for writers and artists (from a cane user, writer, and artist!)

Disclaimer: Though I have been using a cane for 6 years, I am not a doctor, nor am I by any means an expert. This guide is true to my experience, but there are as many ways to use a cane as there are cane users!

This guide will not include: White canes for blindness, crutches, walkers, or wheelchairs as I have no personal experience with these.

This is meant to be a general guide to get you started and avoid some common mishaps/misconceptions, but you absolutely should continue to do your own research outside of this guide!

The biggest recurring problem I've seen is using the cane on the wrong side. The cane goes on the opposite side of the pain! If your character has even-sided pain or needs it for balance/weakness, then use the cane in the non-dominant hand to keep the dominant hand free. Some cane users also switch sides to give their arm a rest!

A cane takes about 20% of your weight off the opposite leg. It should fit within your natural gait and become something of an extension of your body. If you need more weight off than 20%, then crutches, a walker, or a wheelchair is needed.

Putting more pressure on the cane, using it on the wrong side, or having it at the wrong height will make it less effective, and can cause long term damage to your body from improper pressure and posture. (Hugh Laurie genuinely hurt his body from years of using a cane wrong on House!)

(an animated GIF of a cane matching the natural walking gait. It turns red when pressure is placed on it.)

When going up and down stairs, there is an ideal standard: You want to use the handrail and the cane at the same time, or prioritize the handrail if it's only on one side. When going up stairs you lead with your good leg and follow with the cane and hurt leg together. When going down stairs you lead with the cane, then the good leg, and THEN the leg that needs help.

Realistically though, many people don't move out of the way for cane users to access the railing, many stairs don't have railings, and many are wet, rusty, or generally not ideal to grip.

In these cases, if you have a friend nearby, holding on to them is a good idea. Or, take it one step at a time carefully if you're alone.

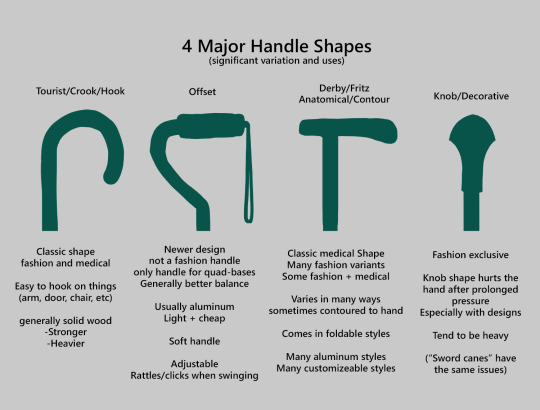

Now we come to a very common mistake I see... Using fashion canes for medical use!

(These are 4 broad shapes, but there is INCREDIBLE variation in cane handles. Research heavily what will be best for your character's specific needs!)

The handle is the contact point for all the weight you're putting on your cane, and that pressure is being put onto your hand, wrist, and shoulder. So the shape is very important for long term use!

Knob handles (and very decorative handles) are not used for medical use for this reason. It adds extra stress to the body and can damage your hand to put constant pressure onto these painful shapes.

The weight of a cane is also incredibly important, as a heavier cane will cause wear on your body much faster. When you're using it all day, it gets heavy fast! If your character struggles with weakness, then they won't want a heavy cane if they can help it!

This is also part of why sword canes aren't usually very viable for medical use (along with them usually being knob handles) is that swords are extra weight!

However, a small knife or perhaps a retractable blade hidden within the base might be viable even for weak characters.

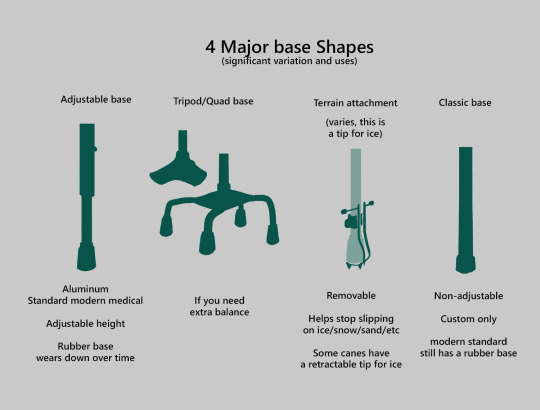

Bases have a lot of variability as well, and the modern standard is generally adjustable bases. Adjustable canes are very handy if your character regularly changes shoe height, for instance (gotta keep the height at your hip!)

Canes help on most terrain with their standard base and structure. But for some terrain, you might want a different base, or to forego the cane entirely! This article covers it pretty well.

Many cane users decorate their canes! Stickers are incredibly common, and painting canes is relatively common as well! You'll also see people replacing the standard wrist strap with a personalized one, or even adding a small charm to the ring the strap connects to. (nothing too large, or it gets annoying as the cane is swinging around everywhere)

(my canes, for reference)

If your character uses a cane full time, then they might also have multiple canes that look different aesthetically to match their outfits!

When it comes to practical things outside of the cane, you reasonably only have one hand available while it's being used. Many people will hook their cane onto their arm or let it dangle on the strap (if they have one) while using their cane arm, but it's often significantly less convenient than 2 hands. But, if you need 2 hands, then it's either setting the cane down or letting it hang!

For this reason, optimizing one handed use is ideal! Keeping bags/items on the side of your free hand helps keep your items accessible.

When sitting, the cane either leans against a wall or table, goes under the chair, or hooks onto the back of the chair. (It often falls when hanging off of a chair, in my experience)

When getting up, the user will either use their cane to help them balance/support as they stand, or get up and then grab their cane. This depends on what it's being used for (balance vs pain when walking, for instance!)

That's everything I can think of for now. Thank you for reading my long-but-absolutely-not-comprehensive list of things to keep in mind when writing or drawing a cane user!

Happy disability pride month! Go forth and make more characters use canes!!!

93K notes

·

View notes

Text

not just ‘he would not fucking say that’ but ‘he would not, under torture, admit that’

#so true#sometimes you write a fic to get the character to that point#of recognition#if not speaking it aloud

91K notes

·

View notes

Text

A safe and cozy cave, perfect for a nap.

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

#!!!!!#i love the dragons#all the art is really so cool#and there are prints!#can get playing cards or art prints!#pride knights#only open to the end of June 2023!

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

One under-appreciated breed of fic writer are the ones who hyperfocus on logistics to the exclusion of all canon shortcuts, and thus usually strike upon an awesome way to flesh out the worldbuilding or characters.

Like, I’m not necessarily talking realism here since often it’s still pretty far from realistic, but more like, “someone has to be running spies in this fantasy kingdom, and we’ve seen the whole royal court, so which background character is it? How does that change these three major interactions?” Or “real life historical nobility did in fact have some things to do that were like jobs, how does this human disaster cope with running an estate?” Or “there’s no reason for a sci-fi robot detective to know how to whitewater kayak, where’d she learn?” Or “if this guy is serving the emperor directly he has to be way high up in the space empire servant hierarchy, why is he doing this menial task for someone else? What’s his motive? Does he perhaps have the secret space telepathy?”

Anyway I’m always DELIGHTED to find a fic or writer who asks these questions because the fics themselves are universally bangers.

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghostbusting Economics: The Great Cultivator Labor Shortage

(Or, an economics nerd tries to write meta)

Ao3 link here.

While I’m an economist by trade, I normally turn my economics brain off while thinking about MDZS. However, there is one theory about the economics of the MDZS jianghu that has crept into my head and won’t go away. My theory? The Sunshot Campaign transformed the labor market for cultivators by creating a labor shortage where there were not enough qualified cultivators to fulfill the demand for cultivation services. This shortage shaped the choices that both sect leaders and disciples made in the post-Sunshot world. Of course, economics cannot explain characters’ decisions on their own: social context and culture matters, and characters’ personal values and desires and worldview matter. However, economic considerations do shape the material stakes characters face in making many of their most important decisions. In particular, a post-Sunshot labor shortage could help explain why:

Mianmian survived to the end of the book

Wen Zhuliu was so deeply grateful to Wen Ruohan

Lure flags were the hottest item on the post-Sunshot market

Rumors of Wei Wuxian’s defection were so threatening to Jiang Cheng

Sect Leader Yao was probably a better boss than you’d think

Xiao Xingchen and Song Lan deeply believed in their dream of starting a new sect

Jiang Cheng never married

First, let’s talk about where money (seemed to) come from in the world of MDZS. The Great Sects made their money by taxing towns in exchange for cultivation services. In addition, judging by the importance of dividing the prey at occasions like the Phoenix Mountain Hunt, some prey may have produced valuable byproducts that the sects could sell or use in medicine and cultivation. Rogue cultivators accepted payment for dealing with cultivation matters that were outside of the geographic regions that the sects protected or otherwise fell outside of the agreements between towns and sects.

Before the Sunshot Campaign, we get glimpses of a cultivation world that was overstaffed and tightly controlled and where the sects competed fiercely for territory and prey. For example, Qishan Wen outright bans the other sects from night hunting in the year after Gusu Summer Camp. While the desire to take away revenue from other sects might have been a reason for this choice, this Wen declaration may also have come because the Wens were confident they had enough cultivators to snap up the prey the other sects were no longer hunting. In fact, the existence of territorial conflicts between any sects suggests that there were more cultivators than prey: if there had been more prey than cultivators, it would have been more profitable for a sect leader to focus their cultivators’ effort on expanding their hunting range and collecting more prey from unprotected areas rather than fighting battles with other cultivators.

Given this scarcity of prey and surplus of cultivators, the Great Sects likely held a monopsony on cultivator labor within their territories. A monopoly refers to when one company is the only seller of a good, like cars or oil; a monopsony happens when a company is the only buyer of a good. For example, a labor monopsony might happen when there’s only one large employer in a small town and thus only one buyer for workers’ labor. Firms like labor monopsonies because when workers have no other options, the firm can drive wages down. As the powerful sects had enough military force to punish cultivators who hunted on their land without permission, they could enforce a monopsony within their territories.

When the Great Sects had this much control over hunting in the best territories, the life of a pre-Sunshot rogue cultivator was unprofitable and dangerous. We know of three pre-Sunshot cultivators who were rogue cultivators at some point: Cangse Sanren, Wei Changze, and Wen (Zhao) Zhuliu. Cangse Sanren and Wei Changze died in Yiling, an area that no sect claimed because the locals were too poor to make facing the Burial Mounds’ extensive dangers worthwhile. Perhaps Cangse Sanren and Wei Changze chose dangerous and poor locations because they wanted to help, but it seems likely that parents of a small child would have placed some value on their own survival. Instead, Yiling may have been one in a string of unprofitable, dangerous hunts that were the only opportunities they could scavenge beyond the reach of the major sects. This is despite Cangse Sangren having been widely known as a very talented cultivator: if this couple couldn’t make it as rogue cultivators, such a life was likely even more brutal for everyone else.

These poor conditions may also explain Wen Zhuliu’s intense loyalty to the Wens. When Wei Wuxian asked Wen Zhuliu why he followed Wen Chao so devotedly, his response was that he owed Wen Ruohan his full devotion and loyalty for recognizing him. The strength of this loyalty had strong cultural grounding, but the terrible economics of life as a rogue cultivator may have also played a role: if the life of a rogue cultivator tended to be dangerous and poor, Wen Zhuliu may truly have felt he owed Wen Ruohan his life for inviting him into the Wen sect. Wen Zhuliu was also a classic example of what happens when workers have no bargaining power in a monopsony situation: employers know that their employees don’t have good alternatives if they leave, so they feel free to treat workers poorly in regards to both pay and general working conditions. In this case, Wen Ruohan handed Wen Zhuliu off to Wen Chao, a regular contender for the Jianghu’s Worst Boss Award. Despite Wen Chao’s abusive bluster and the consistency with which he ignored Wen Zhuliu’s advice, Wen Zhuliu still loyally stuck to the job up until the end.

Ironically, Wen Zhuliu’s death happened right around the time the Sunshot Campaign radically transformed the market for cultivator labor. First of all, cultivators were killed en masse. Out of the five major sects, Wen cultivators were wiped out entirely, the Jiang sect was decimated, and the Lan and Nie sects both suffered large losses. Altogether, I think we can reasonably guess that 50% or more of the Great Sect cultivators died. Mortality rates were high among the smaller sects too. The Yao sect was destroyed right before the Jiang sect massacre (remember an injured Sect Leader Yao stumbling into Sword Hall?), and there are mentions of other small sects being similarly wiped out or forced to battle. So there’s definitely not enough surviving lesser sect cultivators to smooth over the labor market effect of the massive losses of Great Sect cultivators.

At the same time, the war increased demand for cultivator labor. The dead in MDZS became ghosts or fierce corpses in two main kinds of circumstances: when someone died with resentment and when a dead person’s resting place was dishonored. A massive war like the Sunshot Campaign would have killed many civilians who had never received Soul-Calming Ceremonies, and being killed in a war is the sort of resentful death that could definitely leave behind some angry undead. In addition, the disruptions of war would have interrupted typical ceremonies for honoring ancestors and local spirits, causing some of them to turn resentful and harm people nearby. Wei Wuxian’s mass raising of the dead probably didn’t help matters either, since I doubt he always put his corpses away when he was done playing with them. Also, regular night hunting probably came to a near standstill during the course of the war. Who would have the time to chase down ghosts when there were other cultivators trying to chase you down with swords? By the end of the Sunshot Campaign, the need for cultivation work was at an all-time high.

This combination of a decreased supply and an increased demand for cultivator labor added up to create a post-war cultivator labor shortage that made the current burger-flipper situation in the United States look like small potatoes. A labor shortage happens when there aren’t enough qualified workers willing to work in a sector to fill the available jobs in that sector. Sometimes the Jin Guangshans of the world use this to describe any case where people aren’t willing to work under their terrible employment conditions at the low wages the employer wants to pay. However, the post-Sunshot shortage was a true labor shortage: since cultivators take years of training to be able to night hunt, no matter how much employers were willing to pay, there were literally not enough cultivators left alive to do all the night hunts that needed to happen. This meant the price that sects and cultivators were paid for night hunting rose drastically as desperate towns and households bidded against each other to attract cultivators, and some monsters would still remain un-hunted.

To deal with a labor shortage, employers have a few options. One is using labor-saving technology to try to get more done with less people. In the real world this might translate to automated checkouts at grocery stores, investments in self-driving trucks, et cetera. In the jianghu, the newest labor-saving technologies available for cultivators were Wei Wuxian’s wicked tricks. For example, spirit lures allowed cultivators to set up a trap and wait for their prey to come to them, a much quicker and less labor-intensive process than trying to individually track and kill each monster in an infestation. The Compasses of Evil were similar timesavers, helping cultivators go straight to their prey. It’s no wonder that these inventions and their knockoffs were wildly popular on the market and that Jin Guangshan desperately wanted Wei Wuxian’s inventions and notes. The value of these inventions in the face of a labor shortage may be the reason why even the conservative Lan sect was willing to adopt a demonic cultivator’s work. It was much easier for Lan Wangji to add the spirit lures to the curriculum when they helped solve a desperate problem for Gusu Lan.

Although new technology could solve some of the gap between supply and demand, I doubt it closed that gap entirely. There’s still far more night hunts to go around than the existing supply of cultivators could cover. In those conditions, the life of a rogue cultivator would be much, much better than it was before. With the main sects directing their energy at covering night hunts in their domain and raising the next generation of cultivators to replace their losses, they likely had little manpower available for chasing rogue cultivators off their territory, breaking the monopsony power of the Great Sects. In addition, rogue cultivators took the hunts that sect cultivators didn't, and this suddenly encompassed a larger number of higher quality hunts. With villages in urgent need of help, they would likely be willing to pay much higher prices to a passing rogue cultivator. After all, with cultivators so scarce, who knew how long it would be until the next one passed through? Jin Guangyao’s tower system would have been an enormous relief to these rural areas, helping to ensure that at least the most dangerous out-of-the-way night hunts were completed before the monster could take too many lives.

In this type of environment, a skilled rogue cultivator could be treated like a rock star, taking on hunts that won them fame and fortune (if they accepted the money, at least). Take Xiao Xingchen and Song Lan: they were so famous that a bunch of teenagers knew their swords on sight because they’d seen popular illustrations! When Xiao Xingchen and Song Lan fell to misfortune, it was sect politics and not a night hunt that brought them down. Similarly, take the case of Mianmian, who seemed to have built a comfortable life as a rogue cultivator. We don’t know exactly how much she earned through night hunting since her husband also worked as a merchant, but they jointly earned enough for a comfortable home and a happy child, and she was able to stick to night hunts that she could handle safely. For rogue cultivators, post-Sunshot life was good.

This labor shortage also made it a great time to start a new sect. With many towns losing the protection of the Great Sects, they would be happy to help fund a new sect while they got on their feet, and parents would be much more willing to offer their children or even pay for lessons so their children could enter the highly profitable trade of cultivation. Our canon example is Su Minshan, a cultivator skilled enough to spar with Lan Wangji and who felt underappreciated by Gusu Lan. The locals in Moling may have been very willing to fund the sect’s construction and expenses while Su Minshan trained up his first batch of recruits, and the Lan sect were too focused on their own rebuilding to block the sect’s development. Even though the cultivation world disliked him, Su Minshan was able to build a substantial sect during the timeskip, and the patronage of a town in need may explain why.

Since talented cultivators could now make a decent living as rogue cultivators, founding new sects, or getting hired by existing sects in dire need of new cultivators, the leadership of existing sects had to work much harder to keep and attract good people. Defections likely became more common post-Sunshot as cultivators decided they no longer needed to put up with poor conditions. Mianmian is our flagship example, of course: recognizing that the Jin sect would never respect her or care about the ethical standards she did, she decided to throw down her Jin robes and leave. This was still an impactful decision and real sacrifice on her part—she was probably well paid as a member of the cultivation world’s most powerful and wealthy surviving sect—but it was a fully survivable choice for her in a way that it might not have been if she had left before the Sunshot Campaign. This also explains why rumors of Wei Wuxian potentially defecting were so believable and so damaging in the year after Sunshot. In this cultivation shortage, Wei Wuxian could feasibly have struck out on his own, found someplace that needed help badly enough that they would take a demonic cultivator, and set up shop as a sect leader. What’s more, since the Jiang sect badly needed people, a rumor that Jiang Cheng couldn’t even hold on to the talented disciple who was raised with him like a brother would suggest that Yunmeng Jiang was on the edge of collapse.

In this world where cultivators were valuable and had abundant options, the true test of a great sect leader was their ability to attract and keep good people. Some sect leaders could do this through paying their people well: Lanling Jin’s deep pockets would be a big advantage here. Less wealthy sects would need to attract people by being a good place to work. Economists call this a “compensating differential”: people are willing to take lower wages to work at someplace where the work and people are more pleasant. Yunmeng Jiang’s successful rebuilding therefore suggests that Jiang Cheng was likely good to his people despite how brusque he could be towards outsiders. By similar logic, there must be more to Sect Leader Yao than meets the eye: his sect was also massacred by the Wen, and yet he managed to recruit enough people to remain among the prominent sect leaders at cultivation conferences. (And yes, I also cannot believe I’m defending Sect Leader Yao, but sometimes weird rabbit holes lead us to weird places and we just have to go there.)

Another way to attract and keep good people, of course, is to give them opportunities for advancement. Pre-Sunshot, leadership opportunities for cultivators not born to the inner clan of a sect were limited. In Wei Wuxian’s first class at Cloud Recesses, we learned that Qishan Wen sect founder Wen Mao reshaped the cultivation world’s leadership when he decided to put clan over sect. That leadership system elevating bloodline inheritance over talent-based leadership eventually became common to all the Great Sects. For the sect leaders, it guaranteed advancement for their children at the expense of quality of leadership and incentives to other disciples. When potential disciples were numerous, that system produced the occasional Jin Guangshan and cost the resentment of the occasional Su Minshan, but was a fairly painless tradeoff for the Great Sects to make.

Once the labor shortage bit, however, that math changed. The rebuilding sects like Yunmeng Jiang needed every incentive they could give to attract good people. For the most talented and most ambitious cultivators, the chance to be the next sect leader of Yunmeng Jiang would be the biggest prize Jiang Cheng could offer. As long as Jiang Cheng remained unmarried and childless—as long as he chased off matchmakers to ensure he would remain unmarried and childless—he could still leave the role of sect heir open for his most qualified disciple while not openly defying the inheritance norms of the Great Sects. This was a huge change from teenage Jiang Cheng’s plans to marry a sweet filial girl who could give him plenty of Jiang clan bloodline heirs, and it could mark a deliberate strategic decision to help Yunmeng Jiang rebuild despite the labor shortage. With no sect heir to limit their advancement, ambitious cultivators had a good reason to join Yunmeng Jiang and to work hard once they were there. Nie Huaisang and Lan Xichen may have decided to follow Jiang Cheng’s lead and remain unmarried for similar reasons.

This shift in leadership illustrates the potential of a temporary labor shortage to create lasting change through changing institutions. Just like the Black Death labor shortage mattered in the long run because it ended the institution of serfdom, the Sunshot labor shortage could have mattered if people took the opportunity to change sect leadership structures and found new more equitable sects. If none of the institutions changed, the wage boosts of the post-Sunshot era would probably fade within a decade or two as the sects trained up the replacements of the lost generation. However, if the Great Sects really did change the norms around choosing heirs due to the labor shortage, that sort of shift could provide new opportunities for skilled disciples born outside of the inner clans for generations to come. Similarly, the new scrappy sects based on ability and brotherhood rather than blood might have stuck around, competing with the Great Sects and improving employment options for future cultivators. Xiao Xingchen and Song Lan’s dream of founding a new sect was not so much naïve as it was visionary, seeing the potential of a historic upheaval in the cultivation world to create lasting change.

Many thanks to @sometimesophie, Two4Joy, and @eicas for betaing!

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

No problem!

I tend to use scrivener and libreoffice together. When I'm ready to post a story/chapter, I'll either compile or export (depending on if it's all scenes or just one section that I'm posting) a .odt version or copy-paste the scene into libreoffice writer, then use libreoffice's alternative search plugin to batch find/replace for automatic conversion to html. It's the cleanest method I've found for pasting into AO3 without formatting errors.

@ writers, just out of curiosity.... when you write multichapter fics, do you have each chapter in a separate doc or have everything on one big doc?

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

What I've used is this: I keep my main folders in Dropbox so I can easily access the files from two computers, and I also have a scrivener-file back-up on each computer, which is autosaved based on my configuration of scrivener's back-up function (it's on automatically and you can choose when it makes a back-up and how many of the most recent back-ups you want it to save). As I complete parts/when I remember, I also compile the file into a word doc (or rtf, pdf, etc.) to save a back-up in another location that is not a scrivener-specific file type.

You can also choose a back-up in a specific folder whenever you want. There's more about the options here: https://www.literatureandlatte.com/blog/how-to-back-up-your-scrivener-projects

I'm not sure about methods for saving a file as a .doc/rtf/etc., making changes, and then re-opening in scrivener. If I write outside of scrivener I generally copy and paste the new words or edits into the scrivener doc the next time I have it open, but I may just have not figured out tool that the software does have.

@ writers, just out of curiosity.... when you write multichapter fics, do you have each chapter in a separate doc or have everything on one big doc?

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

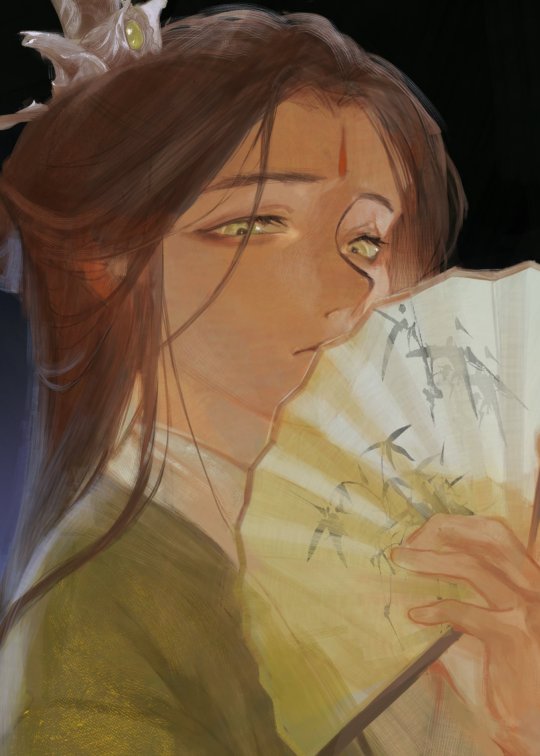

shizun?

#ohhhh very pretty op#love the texture#the eyes and the fan#nicenice#beautiful art#svsss#shen qingqiu

2K notes

·

View notes