#legal and health effects of Dobbs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The legal and health effects of Dobbs

Two years ago, the reactionary majority on the Supreme Court did something that no other cohort of justices had done in the history of our nation: It extinguished an existing constitutional right. In a single decision, it denied women equal protection under the Constitution and demoted them to a subservient status with fewer rights than a fertilized ovum.

It is difficult to measure health effects for large populations in a short period of time. Still, the emerging evidence is that Dobbs is increasing the number of risky and dangerous pregnancies, resulting in increased infant and maternal mortality. Predictably, the most extreme effects are felt by women of color and women who live near or below the poverty line.

A study published in Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) examined the health effects of Texas’ 2021 ban on abortion. See JAMA Pediatrics, Infant Deaths After Texas’ 2021 Ban on Abortion in Early Pregnancy.

The finding of the JAMA investigation was that “recorded infant deaths in Texas and 28 comparison states found that the Texas abortion ban was associated with unexpected increases in infant and neonatal mortality in 2022.” Moreover, the results show that Texas experienced a “12.9% increase [in infant mortality], whereas the rest of the US experienced a comparatively lower 1.8% increase.”

The state abortion bans post-Dobbs are also affecting maternal health. Again, the relatively short time since Dobbs makes it difficult to conduct studies, but statistical modeling predicts a significant increase in maternal mortality—with women of color and women living near or below the poverty line showing the greatest risk. See Nicole Narea’s excellent analysis in Vox, What two years without Roe looks like, in 8 charts.

I recommend Narea’s entire article to your attention. The article covers the legal and medical changes in abortion healthcare since Dobbs. The article also discusses efforts to create statistical models predicting maternal mortality in the absence of access to abortions:

So for now, the best information is based on statistical modeling. Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder projected based on 2020 data on maternal outcomes that, if no abortions were performed nationally, there would be an overall 24 percent increase in maternal deaths after a year. Black mothers would see the biggest increase in mortality.

Finally, OBGYNs have said that their ability to provide reproductive care that meets the medical standard of care has been impacted:

In states where abortion is banned or restricted, for example, six in 10 OBGYNs say their decision-making autonomy has become worse since the Dobbs ruling.

The article also discusses the political dimensions of the post-Dobbs landscape. It repeats a common talking point promoted by (mostly) male political consultants who claim that abortion will not be a decisive factor in 2024. They are wrong—largely because they ignore actual results in 2022 and special elections post-Dobbs and instead rely on flawed polling.

For example, as reported in the Vox article, the survey question that prompts the dismissive attitude toward abortion is this: “What is the most important issue facing the country?” The answers are (in order of frequency of response), “Government,” Immigration,” Inflation,” and “Abortion.”

With all due respect (which is almost none), the question is so poorly phrased as to be meaningless—at least to the extent that it supposedly tests attitudes toward the importance of abortion. It asks about the most important issue “facing the country.” A sensible and reasonable answer to our national crisis is “government”—which encompasses the rule of law, democracy, the Supreme Court, voter suppression, and individual liberty, including reproductive rights. Saying that “government” is the most important issue facing the country does nothing to diminish the importance of reproductive liberty to the women and men affected by Dobbs.

Moreover, “Immigration” is a code word for “I am a MAGA voter.” If the designers of the survey couldn’t figure that out, they should find a new line of work.

And, of course, everyone is concerned about inflation—which is a surrogate for “I am not one of the top 2% that lives on investment returns.” In other words, it is everyone who works for a living saying that their daily economic struggle is the top issue facing America—which says nothing about the passion and anger that surrounds restrictions on reproductive liberty.

I am not a pollster, but I have met people, including women. And anyone who believes that abortion will not be a decisive factor in the 2024 election needs to look up from the spreadsheets and social media to engage with the tens of millions of women and men who are of childbearing age. They care deeply about reproductive liberty and are going to vote on that issue up and down the ballot. Don’t let any political consultant tell you otherwise!

Supreme Court grants review of state bans on gender affirming care

The Supreme Court granted review of Tennessee’s ban on gender affirming care. The grant of review is an ominous sign, as explained by Erin Reed in their Substack, Erin in the Morning, Supreme Court Takes Up Trans Care Ban In Tennessee, With Potentially Huge Impacts.

(Erin In The Morning is the leading source on Substack for news regarding legal developments regarding transgender rights. If you or someone you know is interested in or affected by such developments, I highly recommend the newsletter.)

Per Erin Reed,

On Monday morning, the Supreme Court announced it would take up whether gender-affirming care bans for transgender youth violate equal protection rights under the U.S. Constitution. The case under consideration involves the gender-affirming care ban in Tennessee, where the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals allowed the ban to take effect. The court ruled that transgender people do not have equal protection rights under the Constitution, citing the Dobbs decision overturning abortion and Geduldig v. Aiello, a ruling on pregnancy discrimination that has gained new traction in conservative courts targeting transgender individuals.

It cannot be said often enough: Transgender people are people. Period. They are entitled to the full protection of the Constitution and the laws of the US. But it appears that the Supreme Court is intent on repeating their travesty in Dobbs—creating a second-class citizenship status based on gender identification.

First Roe v. Wade, next transgender rights, then LGBTQ+ rights (including same-sex marriage), and then contraception. The reactionary majority is coming for it all. They are telling us as loudly and clearly as they can.

The Supreme Court is on the ballot in 2024—we must win both chambers of Congress and the presidency so we can expand the Court and release the death grip of the reactionary majority on the Constitution!

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#women's rights#human rights#abortion ban#SCOTUS#Robert B. Hubbell#Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter#election 2024#reproductive rights#Roe v. Wade#Dobbs#legal and health effects of Dobbs

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

when you say “positive / negative right”, what do those mean?

thanks for the good posts :)

a negative right is a claim to protection from some sort of interference; a positive right is a claim that the other party has an obligation to act in some way beyond just refraining from causing harm. for example, the right to free speech is generally spoken about as a negative right: it guarantees me the freedom from state intervention into what i can say. a right to health, on the other hand, would be a positive claim that i should be guaranteed access to things like clean air and water, health care, sick leave, &c.

in practice this distinction is actually much messier than i'm making it sound, and most 'negative rights' are basically meaningless without positive interventions, except in the fantasyland of libertarian political discourse. for example, the united states prohibits one human being from enslaving another (a negative right to legal and bodily freedom) but simultaneously engages in, and permits, incarceration with & without forced and un(der)-compensated labour requirements. the state is not actually granting freedom, and slavery has only been outlawed on a very limited and technical basis. another example is the right to abortion, which, prior to the dobbs decision, was legal in the us on the basis of a 'right to privacy' as established in roe v wade—a freedom from specific interventions in one's medical decisions. however, for decades the actual right to abortion was eroded by the us's lack of universal health care and paid time off, and by laws that became progressively more restrictive in terms of when in a pregnancy abortions were allowed, what clinics had to do in order to be allowed to operate, and what requirements patients had to satisfy first (waiting periods, ultrasounds, &c). in practice this meant that fewer and fewer people could actually access abortion, despite having, technically, legal protection from government interference in its provision. even freedom of speech falls apart as a purely negative right, because, as i've said before, most enforcement of speech limitations actually happens via economic mechanisms like the threat of losing your job—meaning, the operative issue here is not usually whether the state can directly censor me but whether i risk starving to death if a corporation disliked what i said. in other words, what makes my speech vulnerable is the fact that i live in a society that does not guarantee me food, shelter, and basic necessities as positive rights.

negative rights appeal to liberals and other reactionaries because they're framed as maximising everybody's freedom: your actions are only constrained if they risk impinging on me. however, in actuality what this means is that a right defended on 'negative' grounds is basically incapable of redressing existing social and political inequities, and instead upholds or even exacerbates the power dynamics already in effect. i am actually not a huge fan of 'rights' as a legal framework period, and i think a well-defended 'positive right' is really moving beyond the construal of 'rights' and into a more materialist and socially contextualist framework, but that's a different post.

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noah Berlatsky at Everything Is Horrible:

Post election, progressives have argued that Harris spent too much time talking about fracking and military preparedness, and not enough talking about pocketbook issues. Centrists have argued that Harris spent too much time talking about trans issues and marginalized people, and not enough talking about pocketbook issues. Both of these narratives have little to do with the campaign we actually saw, in which Harris spoke extensively about lowering housing costs, helping first time home buyers, and fighting for the middle class. Memory holing Harris’ actual economic proposals is frustrating and silly. But it doesn’t seem likely to do long term damage since there’s at least a general agreement that helping working people and the middle class is in fact a good thing. But there is one aspect of the “Harris didn’t talk about economics” consensus that is disturbing. Abortion, in these discussions, tends to be treated as a side issue disconnected from the concerns of working people and from economic well being. And that’s fucked up.

Abortion Is An Economic Issue

I think everyone would agree that Harris made abortion a central issue in the campaign. She mentioned “Trump abortion bans” at every opportunity and regularly blamed Trump (rightly) for the Supreme Court picks that led to the end of Roe and paved the way for draconian state restrictions. Democrats hoped that state abortion rights ballot measures would boost Harris in states like Arizona and Florida—and though they didn’t win her the election, many of the measures themselves passed, even in very red states like Missouri. Abortion tends to get bracketed as an “identity politics” issue, or as a culture war issue. But part of the reason Dobbs is so unpopular is because, among its other horrors, loss of access to reproductive care is economically devastating.

[...]

Whose pocketbooks are we talking about?

Harris’ campaign focused more on the health dangers of abortion restrictions, especially on two heartbreaking cases in Georgia where the state’s abortion ban prevented two women from receiving care, leading to their deaths. The longterm damage to women’s economic standing and career options were less of a focus, in part no doubt because these consequences are seen as less sympathetic. Many conservatives believe that pregnant women should be willing, and if not willing, forced, to prioritize a blob of fetal tissue over their careers. Democrats and progressives, though, should in theory be better than that. We should know that abortion rights are a pocketbook issue for anyone who can get pregnant, and for their partners, parents, and children. When assessing Harris’ campaign, we should be acknowledging that abortion rights are crucial for economic wellbeing. To say that Harris didn’t campaign on pocketbook issues is to say that abortion is not a pocketbook issue. Which it is.

[...]

You can’t have economic progress without rights

Democrats can be timid about connecting economic wellbeing with social justice and civil rights, because they worry that any mention of non white male identity will lead to powerful white male backlash. Again, this is why Harris probably played down the economic effects of abortion in her messaging. In the second, wretched Trump era, though, it’s going to become painfully clear that when you’re denied equal rights, you’re also denied economic opportunity. You can work hard, but that’s not going to matter much if Trump revokes your legal immigration status or deports your spouse. You can go to school and get a degree to teach, but that won’t help you if LGBT people and Black people are purged from secondary and post secondary education. And, once more, if reproductive care—maybe including birth control—is banned, the financial fate of women and pregnant people becomes extremely precarious.

This piece from Noah Berlatsky on why abortion is an economic justice issue is spot on.

#Abortion#Economy#Health Care#Kamala Harris#2024 Presidential Election#2024 Elections#Maternal Mortality#Economic Justice#Reproductive Health

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coverture is an arcane but newly relevant legal idea that goes all the way back to the 1700s: the notion that a woman’s legal identity vanishes whenever it finds itself in close proximity to something deemed to be a superior interest. In the 1700s, that interest was the husband. Today, it’s the fetus.

Currently, those in favor of legislative restrictions on abortion usually justify them on two bases. The first is that restrictions exist to protect the health of the pregnant person. Sometimes this justification focuses on the medical safety of the procedure (“Abortion is dangerous”), and sometimes on the mental health of the pregnant person (“People regret getting abortions”). In either case, this justification has proven relatively easy to debunk, since there is extensive evidence demonstrating that abortion is not only safe and common, but that people who are denied abortions experience worse physical and mental health outcomes. The second, stickier justification is that the state can restrict abortion because the state has an interest in protecting the embryo or fetus. (For ease of reading, I will be primarily using the term “fetus,” but it is worth noting that “fetus” refers to a specific stage of development beginning around the eleventh week of pregnancy. Many legislative restrictions prohibit abortion earlier than that, while the pregnant person is still carrying an “embryo.”) The idea that the state has this prevailing interest gets articulated in a variety of ways: from Roe’s more objective-sounding “interest in protecting the potentiality of human life” to the more emotional insistence on using terms like “unborn human being” rather than clinical descriptors for fetal development���as in the Mississippi Gestational Age Act (the legislation that was at issue in Dobbs). This justification is closer to what most people think of as the “real” reason motivating abortion restrictions: Namely, people oppose abortion because they want to protect the fetus.

The legal maneuver performed by coverture—the subsuming of a woman’s identity into a nearby and supposedly superior interest—precisely describes what happens in legislation that is advanced on the basis of the state’s interest in protecting potential life. In other words: When the state recognizes the legal interest of the fetus but not that of the pregnant person, it is subsuming the identity of the pregnant person into that of her fetus. From a legal standpoint, when a person becomes pregnant, she simply stops existing. The only thing that exists is her fetus. We can see this conspicuous absence all over the current panoply of abortion restrictions. This is particularly the case in the definitions embedded in the legislation, which often feature elaborate wordings that foreground the legal identity of the fetus and de-emphasize that of the pregnant person. ... What is so insidious and effective about repurposing the mechanisms underlying coverture in this new context is that it sanitizes coverture’s now-obvious sexism by replacing the idea of the husband with the idea of the child. Nowadays, a law that expressly privileged men over women would have a hard time surviving public scrutiny. But a law that expressly privileges the idea of children over women is another matter entirely. Because even today, we tend to view pregnant women as mothers first and anything else second, and women who attempt to fight against this framing are often vilified as cruel or uncaring, or simply bad mothers. In short, we already have a cultural apparatus that primes us to minimize a woman’s identity in proximity to pregnancy or children.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shira Fishbach, a newly graduated physician, was sitting in an orientation session for her first year of medical residency when her phone started blowing up. It was June 24, 2022, and the US Supreme Court had just handed down its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, nullifying the national right to abortion and turning control back to state governments.

Fishbach was in Michigan, where an abortion ban enacted in 1931 instantly came into effect. That law made administering an abortion a felony punishable by four years in prison, with no exceptions for rape or incest. It was a chilling moment: Her residency is in obstetrics and gynecology, and she viewed mastering abortion procedures as essential to her training.

“I suspected during my application cycle that this could happen, and to receive confirmation of it was devastating,” she recalls. “But I had strategically applied where I thought that, even if I didn't receive the full spectrum, I would at least have the support and the resources to get myself to an institution that would train me.”

Her mind whirled through the possibilities. Would her program help its residents go to an access-protecting state? Could she broker an agreement to go somewhere on her own, arranging weeks of extra housing and obtaining a local medical license and insurance? Would she still earn her salary if she left her program—and how would she fund her life if she did not?

In the end, she didn’t need to leave. That November, Michigan voters approved an amendment to the state constitution that made the 1931 law unenforceable, and this April, Governor Gretchen Whitmer repealed the ban. Fishbach didn’t have to abandon the state to learn the full range of ob-gyn care. In fact, her program at the University of Michigan, where she’s now a second-year resident, pivoted to making room for red-state trainees.

But the dizzying reassessment she underwent a year ago provides a glimpse of the challenges that face thousands of new and potential doctors. Almost 45 percent of the 286 accredited ob-gyn programs in the US now operate under revived or new abortion bans, meaning that more than 2,000 residents per year—trainee doctors who have committed to the specialty—may not receive the required training to be licensed. Among students and residents, simmering anger over bans is growing. Long-time faculty fear the result will be a permanent reshaping of American medicine, driving new doctors from red states to escape limitations and legal threats, or to protect their own reproductive options. That would reduce the number of physicians available, not just to provide abortions, but to conduct genetic screenings, care for miscarriages, deliver babies, and handle unpredictable pregnancy risks.

“I worry that we’re going to see an increase in maternal morbidity, differentially, depending on where you live,” says Kate Shaw, a physician and associate chair of ob-gyn education at Stanford Medicine. “And that’s just going to further enhance disparities that already exist.”

Those effects are not yet visible. The pipeline that ushers medical graduates through physician training is about a decade long: four years of school plus three to seven years of residency, sometimes with a two-year, sub-specialty fellowship afterward. Thus actions taken in response to the Dobbs decision—people eschewing red-state schools or choosing to settle in blue states long-term—might take a while to be noticeable.

But in this year, some data has emerged that suggests trends to come. In February, a group of students, residents and faculty surveyed 2,063 licensed and trainee physicians and found that 82 percent want to work or train in states that retain abortion access—and 76 percent would refuse to apply in states that restrict it. (The respondents worked in a mix of specialties; for those whose work would include performing abortions, the proportion intending to work where it remains legal soared above 99 percent.)

Then in April, a study from the Association of American Medical Colleges drawing on the first round of applications to residency programs after Dobbs found that ob-gyn applications in states with abortion restrictions sank by 10 percent compared to the previous year. Applications to all ob-gyn programs dropped by 5 percent. (Nationwide, all applications to residency went down 2 percent from 2021 to 2022.)

Last month, two preliminary pieces of research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists uncovered more perturbations. In Texas—where the restrictive law SB8 went into effect in September 2021, nine months before Dobbs—a multi-year upward trend in applications to ob-gyn residency slowed after the law passed. And in an unrelated national survey, 77 percent of 494 third- and fourth-year medical students said that abortion restrictions would affect where they applied to residency, while 58 percent said they were unlikely to apply to states with a ban.

That last survey was conducted by Ariana Traub and Kellen “Nell” Mermin-Bunnell, two third-year medical students at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta—which lies within a state with a “fetal heartbeat” law that predates Dobbs and that criminalizes providing an abortion after six weeks of pregnancy. The law means that students in clinical rotations are unlikely to witness abortions and would not be allowed to discuss the procedure with patients. It also means that, if either of them were to become pregnant while at med school, they would not have that option themselves.

Before they published the survey, the two friends conducted an analysis of how bans would affect medical school curricula, using data collected in the summer of 2022. They predicted that only 29 percent of the more than 129,000 medical students in the US would not be affected by state bans. The survey gave them a chance to sample med students’ feelings about those developments, with the help of faculty members. They also founded a nonprofit, Georgia Healthcare Professionals for Reproductive Justice. “We're in a unique position, as individuals in the health care field but not necessarily medical professionals yet,” Traub says. “We have some freedom. So we felt like we had to use that power to try to make change.”

Ob-gyn formation is caught between opposing forces. Just over half of US states have passed bans or limitations on abortion that go beyond the Roe v. Wade standard of fetal viability. But the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, a nonprofit that sets standards for residency and fellowship programs, has always required that obstetric trainees learn to do abortions, unless they opt out for religious or moral reasons. It reaffirmed that requirement after the Dobbs decision. Failure to provide that training could cause a program to lose accreditation, leaving its graduates ineligible to be licensed.

The conflict between what medicine demands and state laws prevent leaves new and would-be doctors in restrictive states struggling with their inability to follow medical evidence and their own best intentions. “I’m starting to take care of patients for the first time in my life,” says Mermin-Bunnell, Traub’s survey partner. “Seeing a human being in front of you, who needs your help, and not being able to help them or even talk to them about what their options might be—it feels morally wrong.”

That frustration is equally evident among trainees in specialties who might treat a pregnant person, prescribe treatments that could imperil a pregnancy, or care for a pregnancy gone wrong. Those include family and adolescent medicine, anesthesiology, radiology, rheumatology, even dermatology and mental health.

“I’m particularly interested in oncology, and I’ve come to realize that you can’t have the full standard of gynecologic oncology care without being able to have access to abortion care,” says Morgan Levy, a fourth-year medical student in Florida who plans to apply to ob-gyn residency. Florida currently bans abortion after 15 weeks; a further ban, down to six weeks, passed in April but has been held up by legal challenges. In three years of med school so far, Levy received one lecture on abortion—in the context of miscarriage—and no clinical exposure to the procedure. “It is a priority for me to make sure that I get trained,” she says.

But landing in a training program that encourages abortion practice is more difficult than it looks. Residency application is an algorithm-driven process in which graduates list their preferred programs, and faculty rank the trainees they want to teach. For years, there have been more applicants than there are spaces—and this year, as in the past, ob-gyn programs filled almost all their slots. What that means, according to faculty members, is that some applicants will end up where they do not want to be.

“Students and trainees do exert their preferences, but they also need to get a training spot,” says Vineet Arora, the dean for medical education at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine and lead author on the survey published in February. “Would they forgo a training spot because of Dobbs? That's a tall order, especially in a competitive field. But would they be happy about it? And would they want to stay there long term?”

That is not a hypothetical question. According to the medical-colleges association, more than half of residents stay to practice in the states where they trained. But it’s reasonable to ask whether they would feel that loyalty if they were deprived of training or forced to relocate. “If even a portion of the 80 percent of people who prefer to practice and train in states that don't have abortion bans follow through on those preferences, those states that are putting in abortion bans—which often have workforce shortages already—will be in a worse situation,” Arora says.

An ACOG analysis estimated in 2017 that half of US counties, which are home to 10 million women, have no practicing ob-gyn. When the health care tech firm Doximity examined ob-gyn workloads in 2019, seven of the 10 cities it identified as having the highest workloads lie in what are now very restrictive states. Those shortages are likely to worsen if new doctors relocate to states where they feel safe. The legal and consulting firm Manatt Health predicted in a white paper last fall: “The impact on access to all OB/GYN care in certain geographies could be catastrophic.”

Faculty are struggling to solve the mismatch between licensing requirements and state prohibitions by identifying other ways residents can train. They view it as protecting the integrity of medical practice. “Any ob-gyn has to be able to empty the uterus in an emergency, for abortion, for miscarriage, and for pregnancy complications or significant medical problems,” says Jody Steinauer, who is vice-chair of ob-gyn education at UC San Francisco.

Steinauer directs the Kenneth J. Ryan Residency Training Program, a 24-year-old effort to install and reinforce clinical abortion training. Even before Dobbs, that was hard to come by: In 2018, Steinauer and colleagues estimated that only two-thirds of ob-gyn residency programs made it routine, despite accreditation requirements—and that anywhere from 29 to 78 percent of residents couldn’t competently perform different types of abortion when they left training. In 2020, researchers from UCSF and UC Berkeley documented that 57 percent of these programs face limitations set by individual hospitals more extreme than those set by states.

Before Dobbs, the Ryan program brokered individual relocations that let trainees temporarily transfer to other institutions. Now it is working to set up program-to-program agreements instead, because the logistics required to visit for a rotation—the kind of arrangements Fishbach dizzily imagined a year ago—are more complex than most people can manage on their own. And not only on the visiting trainee: Programs already perform delicate calculations of how many trainees they can take given the number of patients coming to their institutions and the number of faculty mentors.

Only a few places have managed to institutionalize “away rotations,” in which they align accreditation milestones, training time, and financing with other institutions. Oregon Health & Science University’s School of Medicine is about to open a formal program that will accept 10 to 12 residents from restrictive states for a month each over a year. Oregon imposes no restrictions on abortion, and both the med school’s existing residents and the university’s philanthropic foundation supported the move.

“I'm very concerned about having a future generation that knows how to provide safe abortion care—because abortion will never go away; becoming illegal only makes it less safe,” says Alyssa Colwill, who oversees the new program and is an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology. “There are going to be patients that are going to use unsafe methods because there's no other alternative. And providers are going to be placed in scenarios that are heartbreaking, and are devastating to watch.”

The accreditation council now requires programs that cannot train their own residents in abortion to support them in traveling somewhere else. But even at schools that are trying to accommodate as many learners as possible, trainees can attend for only a month—the maximum that fully enrolled programs in safe states can afford. After that, they must go back home, leaving them less-trained than their counterparts. As faculty look forward, they fear a slow spiral of decay in obstetric knowledge.

This isn’t imaginary: Already, research has shown that physicians practicing in red states are less likely to offer appropriate and legal procedures to treat miscarriages. Receiving abortion training, in other words, also improves medical care for pregnancy loss.

“Ultimately, I do not think there is capacity to train every resident who wants training,” says Charisse Loder, a clinical assistant professor of ob-gyn at the University of Michigan Medical School, who directs the program where Fishbach is training. “So we will have ob-gyn residents who are not trained in this care. And I think that is not only unfortunate, but puts patients in a position of being cared for by residents who don't have comprehensive training.”

Doing only short rotations also returns residents to places where their own reproductive health could be put at risk. Future physicians are likely to be older than in previous generations, having been encouraged to get life experience and sample other careers before entering med school. Research on which Levy and Arora collaborated in 2022 shows that more than 11 percent of new physicians had abortions during their training. Because of the length of training, they also may be more likely to use IVF when they are ready to start families—and some reproductive technologies may be criminalized under current abortion bans.

As a fourth and final-year psychiatry resident, Simone Bernstein had thought about abortion restrictions through the lens of her patients’ mental health, as she talked to them about fertility treatment and pregnancy loss. As cofounder of the online platform Inside the Match, she had listened to residents’ reactions to Dobbs (and collaborated on research with Levy and Arora). She had not expected the decision to affect her personally—but she is in Missouri, a state where there is an almost complete ban on abortion. And this spring, she experienced a miscarriage at 13 weeks of pregnancy.

“I was worried whether or not I could even go to the hospital, if my baby still had a heartbeat, which was a conversation that I had to have with my ob-gyn on the phone,” she says. “It didn’t come to that; I caught the baby in my hands at home, hemorrhaging blood everywhere, and the baby had already passed away. But until that moment, I didn't recognize the effects that [abortion restrictions] could have on me.”

This is the reality now: There exist very few places in the US where abortion is uncomplicated. Faculty and their trainees do not expect that to change, except for the worse. Staying in the field, and making sure the next generation is prepared, requires commitment that they will have to sustain for years.

“Part of the reason why I sought advanced training in abortion and contraception is because I think there will be a national ban,” says Abigail Liberty, an ob-gyn and fellow in her sixth postgraduate year at OHSU. “I think it will happen in our lifetime. And I see my role as getting as much expertise and training as I can now and providing care while I can. And then coming out of retirement, when abortion will be legal again, and training the next generation of physicians.”

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amarillo is the biggest Texas locality, so far, to consider the policy as a ballot measure—making this perhaps the most significant chance for ordinary Texas residents to vote on abortion rights since Roe v. Wade was overturned in June 2022. Statewide, voters may never get the chance to protect abortion rights as they have in Kansas, Kentucky, and Ohio and might in at least 10 other states this November. This is because Texas is among the two dozen states that do not allow citizen-initiated statewide ballot measures, something only the GOP-controlled Legislature could change.

[...]

“Generally, we don’t allow states to reach outside of their borders and regulate activity in another state,” said Liz Sepper, a University of Texas at Austin professor who specializes in healthcare law. “It’s even more suspect for a city to try and enforce its moral code outside its boundaries well beyond what the state has even done.”

However, there is a “complex gray area” that could be open to a loophole, said Sepper. For instance, in his concurring opinion in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling that overturned Roe, Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted that patients could not be prosecuted for out-of-state abortions under the constitutional right to interstate travel, yet he failed to address the civil enforcement strategy found in the travel bans. Additionally, that private enforcement framework helps shield the bans from federal lawsuits seeking to block them, as is also the case with SB 8.

When confronted with the possible unconstitutionality of the ordinance, Dickson and his anti-abortion cohort often cite the federal Mann Act, a 1910 law—accused of being used as a tool of racially motivated persecution in the mid-20th century—that was originally intended to criminalize the transport of “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.”

“These prohibitions on abortion trafficking no more infringe the constitutional right to travel than prohibitions on sex trafficking infringe the constitutional right to travel,” said Dickson.

Regardless, the ordinance would likely create a chilling effect on those traveling out of state for care—and advocates say that’s by design. SB 8’s similar vigilante-style enforcement created the risk of potential litigation against anyone supporting care, which immediately halted abortion in Texas, causing damage even before legal pushback. “Like with SB 8, the point is to create fear,” said Sepper.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Illinois legislature passed an assault weapons ban earlier this year. On Friday the Illinois Supreme Court upheld that ban.

The Illinois Supreme Court has rejected a challenge to the state’s ban on assault weapons, meaning that law will stay in effect statewide. In a 4-3 decision issued Friday morning, the high court overturned a lower court’s ruling, stating the ban is constitutional and does not “deny equal protection nor constitute special legislation.” Gov. J.B. Pritzker said he was “pleased” with the ruling Friday and called it a win for “advocates, survivors, and families alike because it preserves this nation-leading legislation to combat gun violence and save countless lives.” “This is a commonsense gun reform law to keep mass-killing machines off of our streets and out of our schools, malls, parks, and places of worship,” he said in a statement. “Illinoisans deserve to feel safe in every corner of our state—whether they are attending a Fourth of July Parade or heading to work—and that’s precisely what the Protect Illinois Communities Act accomplishes.”

The law is not retroactive and those who legally bought such guns before the law went into effect can keep them. The differentiation between existing ownership and new ownership was the basis for the suit which SCOIL ruled on.

“To the extent plaintiffs allege they already possess restricted items, plaintiffs may retain them but may not acquire more, which matches the restrictions placed on those who are grandfathered under the Act,” the court wrote in its ruling. “The statutes treat plaintiffs who already possess assault weapons and LCMs the same as the grandfathered individuals.”

There will probably be other attempts to overturn the Illinois law. The Illinois assault weapons ban may very well end up before the US Supreme Court. A SCOTUS ruling against the Illinois law in an election year could set off a firestorm similar to what happened after the Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision last year.

The assault weapons law would not have been possible without a Democratic trifecta in Illinois.

After decades of treating state government like a poor cousin, Democrats in many states have taken a renewed interest in that level of governance. Michigan Democrats gained a trifecta in Michigan for the first time in over 35 years with the 2022 elections and passed a remarkable series of reforms in 100 days.

So good things happen when people get more involved in state politics. As I like to remind people, the first step is to find out who represents you in your state legislature. This site makes it easy to find that out...

Find Your Legislators Look your legislators up by address or use your current location.

#illinois#assault weapons#assault weapons ban#illinois legislature#illinois law#illinois supreme court#j.b. pritzker#gun violence#democratic trifecta#state government#election 2023#election 2024

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the greater indignities of the Dobbs Supreme Court decision—besides stripping millions of American women of their bodily autonomy—was how deeply out of step it was with the majority of Americans’ beliefs. According to a 2023 Gallup poll, a record-high 69 percent of Americans believed that first-trimester abortions should be legal. Considering this statistic, it’s surprising that Democrats haven’t more robustly rallied people around this issue. One reason may be that they just don’t know how.

Roe gave American women decades of false comfort: Abortion access and reproductive rights could remain firmly in the dominion of feminist causes. Keep Your Hands Off My Reproductive Rights T-shirts became nearly as ubiquitous as Girl Boss tote bags. But although most Americans support abortion access, feminism remains more polarizing. Only 19 percent of women strongly identify as feminists. That number is far higher among young women, but among young men, the word has a different resonance: Feminism has been explicitly cited as a factor driving them rightward. Democrats might not like how this sounds, but what they need to do now is reframe a winning issue in nonfeminist terms.

One way is to talk about abortions as lifesaving health care, which more women have been doing. Another model is to talk about it not as a women’s issue, but as a family issue. This is the strategy of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice. For 15 years, NLIRJ has worked in states such as Florida, Texas, and Arizona, training community leaders it calls poderosas to speak with their neighbors. The conversations don’t necessarily begin with abortion at all.

[Read: It’s abortion, stupid]

Most Hispanics in the United States are Catholic. Despite a deeply ingrained religious taboo against abortion, 62 percent now believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. That number has risen 14 percentage points since 2007. This remarkable change is partly a reaction to draconian abortion restrictions in several Latino-heavy states. But much credit should also be attributed to years of grassroots work by organizations like NLIRJ to shift the culture.

“We ask them what keeps them up at night,” Lupe Rodríguez, the group’s executive director, told me. Rodríguez holds a degree in neurobiology from Harvard and was a scientist before she shifted into reproductive-justice work. That opening question might yield answers about problems at home or a lack of functioning electricity in their neighborhood. The point, Rodríguez said, is to go past individual “rights” and to connect “reproductive autonomy and bodily autonomy to the conditions that people live in, right? Like whether or not they’re able to feed their kids, whether or not they have money to pay the rent—like everyday concerns.” In this way, reproductive rights go beyond a niche women’s issue to something that affects every aspect of a community.

None of NLIRJ’s materials uses the term feminist. Rodríguez said this wasn’t a conscious decision, but she stands by it. “Our approach is a lot about certainly freedom, certainly bodily autonomy, certainly folks being able to make the best choices for themselves and their families. But it’s very connected to community and family.”

Poderosas are trained on how to discuss faith and abortion, and voting and abortion. Crucially, they are not required to personally hold pro-abortion views. The organization is nonpartisan. Involvement has no ideological requirement other than believing that everyone should be entitled to make decisions that are appropriate for themselves and their family. “We’re bringing people in that way, by not casting them aside” if they don’t share the same perspectives, Rodríguez told me.

This has proved an effective strategy for Latino advocates across the country, and one that Democrats can learn from. In Florida, NLIRJ and other organizations, such as the Women’s Equality Center, have shifted the narrative around abortion bans to be about the government interfering in private family matters. In Arizona, a recent poll by LUCHA, a family-oriented social-justice organization there, found that 75 percent of Latino voters agreed that abortion should be legal, regardless of their personal views on the matter. In New Mexico, male Hispanic Democratic politicians are campaigning on reproductive rights even in conversations with Latino male voters, whose primary concern is typically the economy. Representative Gabriel Vasquez is banking on this being a matter of family and personal liberty—exactly what drove so many Latino immigrants to America in the first place. “It is not about whether we are pro-choice or pro-life,” he recently told The New York Times. “It is about trusting the people that we love to make those decisions for themselves.”

Latinos have played large roles in getting abortion-rights measures on the ballot in Florida and Arizona this fall. And although just 12 percent of the general electorate considers abortion access a leading issue, according to a 2022 national survey, that number was 19 percent among Latinos.

[Read: Are Latinos really realigning toward Republicans?]

So often, political analysts look at how Latinos vote without asking why. It’s as if they assume that Latinos’ rationales are too foreign to understand. Democrats should not make that mistake now. This pragmatic approach is appealing to Latinos because they are largely politically moderate, working- and middle-class people concerned about their family, and about kitchen-table issues—just like much of the population in swing states. The Republican Party seems to have caught on to this; Democrats can’t afford to miss it.

No self-identified feminist who deserves the title will be supporting the intergenerational-bro ticket of Trump-Vance in 2024. The Democratic Party doesn’t need to pander to those voters, or pass a rhetorical purity test on women’s rights to galvanize them; they’re voting Democratic no matter what. Democrats need to focus on all the other voters—who may not care about feminism but do care about their families’ health and ability to thrive—and reframe abortion as an issue that affects everyone.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Downfall of the US Supreme Court

The recent trajectory of the United States Supreme Court has raised significant concerns about its credibility and impartiality. The Court, historically viewed as a pillar of justice and an arbiter of constitutional integrity, now faces scrutiny due to a series of decisions that appear to align closely with right-wing ideologies. This perceived shift challenges the foundational principles of impartiality and equity that are essential for maintaining public trust in the judiciary.

One of the most contentious issues involves the Court's rulings on voting rights. Decisions such as Shelby County v. Holder, which invalidated key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, have been criticized for undermining efforts to protect against racial discrimination in voting. By effectively weakening federal oversight, the Court has enabled the implementation of state-level laws that disproportionately affect minority voters, raising questions about the commitment to ensuring equal access to the democratic process.

Additionally, the Court's approach to reproductive rights has sparked significant debate. The overturning of Roe v. Wade in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision represents a profound shift in legal precedent, affecting millions of women across the country. Critics argue that this decision not only disregards decades of established jurisprudence but also imposes a particular moral viewpoint, thereby infringing on personal liberties and bodily autonomy.

The influence of corporate interests on the Court's decisions has also come under scrutiny. In cases like Citizens United v. FEC, the Court has expanded the role of money in politics, equating financial expenditure with free speech. This interpretation has paved the way for unprecedented levels of corporate influence in elections, potentially skewing political outcomes in favor of wealthy interests at the expense of ordinary citizens.

Furthermore, the Court's stance on environmental regulations has raised alarms among advocates for climate action. By limiting the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, the Court appears to favor deregulation over environmental protection, potentially jeopardizing efforts to combat climate change and protect public health.

The cumulative effect of these decisions suggests a judiciary increasingly aligned with conservative ideologies, raising critical questions about the balance and separation of powers. As the Court continues to wield significant influence over American life, it is imperative to ensure that its rulings reflect a commitment to justice, equality, and the broader public good, rather than narrow partisan interests.

Rebuilding trust in the Supreme Court requires a renewed dedication to impartiality and a recognition of the diverse needs and values of the American populace. Only through such measures can the Court regain its standing as a fair and just arbiter of the nation's laws.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Get ready for Dobbs 2.0, a decision that will far exceed the damage done by the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson’s Women’s Health.

In Dobbs v. Jackson’s Women’s Health, the radical majority on the Supreme Court ruled that there is no constitutional right to privacy that protects reproductive liberty. As a result, the debate over regulation of abortion was returned to the states. Or so we thought.

It is likely that a single federal judge in Texas will issue a nationwide ban on Mifepristone, a drug approved by the FDA for more than two decades to induce therapeutic abortions. The ruling, if made, will effectively outlaw or deny access to abortions across vast swaths of the nation—even in states where legislation or the state constitution protects the right of reproductive liberty.

We have reached this sorry state of affairs because ultra-conservative federal judges in Texas have rigged the system to ensure that all challenges to reproductive liberty and LGBTQ rights are funneled to a single judge with extreme religious views. The situation is explained by Dennis Aftergut and Laurence Tribe in Slate, The Texas-Sized Loophole That Brought the Abortion Pill to the Brink of Doom.

Aftergut and Tribe write,

The problem here goes beyond a single hearing, or even this single case. The real issue is systemic. Far-right groups have created a judicial pipeline to predictable triumph in one culture war battle after another: from Kacsmaryk in the plains of the Texas panhandle, to the hyperconservative U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, to the radically stacked majority on the Trump-packed U.S. Supreme Court. One Amarillo-based judge with carte blanche, virtually certain his extreme views will prevail on appeal, is apparently planning to curtail abortion access across the country.

[Here, there is] a coordinated national strategy, enabled by a district court federal bench, to bring right-wing legal causes into a single courtroom where a favorable result is a sure thing and where fair-minded appellate review has also been hijacked.

There is a simple—albeit difficult to achieve—solution. We need only elect a Congress and president willing to enact legislation to reform the federal judiciary. That will require (in my view) a carve-out of the filibuster, an expansion of the Supreme Court, curbs on the ability of a single federal judge to issue nationwide injunctions, restrictions on the ability of the Supreme Court to issue merits-based decisions on its “shadow docket,” and enactment of an enforceable code of ethics on the Supreme Court (among many other reforms).

At some point, the imposition of an extreme religious ideology on all Americans by a new class of judicial aristocrats—or “juristocrats” as described by Aftergut and Tribe—should cause Americans to reclaim their constitutional birthright. We have been too complacent in the face of a concerted assault over the last decade. Perhaps Dobbs 2.0 will be the decision that finally causes Americans to understand that the reactionary judges aren’t going stop until they have effectively codified their religious beliefs in federal law. The coming decision will hurt. Let’s turn our outrage into action.

North Carolina Supreme Court to reconsider case underlying Moore v. Harper.

On Tuesday, March 14, the North Carolina Supreme Court will hold a hearing to reconsider its ruling in the case underlying Moore v. Harper, currently on appeal before the US Supreme Court. You may recall that Moore v. Harper raises the question of whether the Independent State Legislature theory insulates the NC state legislature from judicial oversight.

Last year, the North Carolina Supreme Court overturned congressional district boundaries drawn by the state legislature. When the partisan composition of the NC Supreme Court flipped from Democratic to Republican, the new Republican majority on the court agreed to reconsider its ruling—for no good reason other than that it could.

Chances are good that the NC Supreme Court will reverse its prior ruling, thereby mooting the appeal to the US Supreme Court. The complicated procedural background and possible outcomes are explained by Democracy Docket, North Carolina Supreme Court To Rehear State-Level Redistricting Case Underlying Moore v. Harper - Democracy Docket.

Like the rogue federal judges in the Fifth Circuit, the Republican judges on the NC Supreme Court are making nakedly partisan rulings because they can. Like the solution for the federal judiciary, the solution in North Carolina is through the ballot box.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#Corrupt SCOTUS#Opus Dei SCOTUS#Robert B. Hubbell#Robert B Hubbell Newsletter#Women's Rights#women's history#reproductive freedom#reproductive rights#political#the law

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every conservative justice on the Supreme Court bowed out of deciding a case stemming out of Texas.

In a rare move, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett all sat out deciding whether to hear MacTruong v. Abbott, a case arguing that the Texas Heartbeat Act (THA) is constitutional and that the state law violates federal law. The six justices were named as defendants in the case. They did not give a detailed justification as to why they chose not to weigh in, and are not required to do so.

Monday's order list from the Supreme Court states that the six conservatives on the bench "took no part in the consideration or decision of this petition." Because there were not enough justices for a quorum—the court needs at least six and only Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson remained—the court affirmed the judgment of a lower court to dismiss the lawsuit.

The case was brought by MacTruong, a U.S. citizen who resides in New Jersey, against the six conservative justices, Texas Governor Greg Abbott, Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives Dade Phelan and former President Donald Trump. MacTruong alleges the defendants were involved in either passing, enacting or upholding the THA because he believes the Dobbs decision was incorrectly decided and thus, Roe v. Wade is still law.

In June 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, ending federal access to abortion.

Judicial politics expert Alex Badas told Newsweek that the justices may be ineligible to partake in the decision because of the court's recent statement on its ethics. "A Justice should disqualify himself or herself in a proceeding in which the Justice's impartiality might reasonably be questioned, that is, where an unbiased and reasonable person who is aware of all relevant circumstances would doubt that the Justice could fairly discharge his or her duties," the statement said.

"I believe being named in the suit falls into this category of disqualification," Badas said.

Affirming the decision from the Fifth Circuit, which ruled against MacTruong and decided that he did not have standing to sue, the Supreme Court effectively tossed the suit altogether.

"The Fifth Circuit was unanimous against MacTruong," Badas said. "It is worth noting that two of the three judges who heard the case were appointed by Democratic presidents. These judges may be sympathetic to his claim that Dobbs was incorrectly decided but it shows that his legal case for standing is very weak that they vote against him."

Badas noted that MacTruong has other pending cases involving the same issue, but it is likely that they will end like this case, "with him losing and the courts issuing decisions arguing that he lacks standing."

Other plaintiffs named in the suit include the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar, Cory Booker and Bernie Sanders, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, President Joe Biden, California Governor Gavin Newsom, actors George Clooney, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, Tesla Founder Elon Musk, singer Britney Spears and media expert Norah O'Donnell.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna North at Vox:

Imagine you’re eight months pregnant, and you wake up in the middle of the night to a bolt of pain across your belly. Terrified you might be losing your pregnancy, you rush to the emergency room — only to be told that no one there will care for you, because they’re worried they could be accused of participating in an abortion. The staff tells you to drive to another hospital, but that will take hours, by which time, it might be too late.

Such frightening experiences are growing more common in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health decision, as doctors and other medical staff, fearful of the far-reaching effects of state abortion bans, are simply refusing to treat pregnant people at all. It’s part of what some reproductive health activists see as a disturbing progression from bans on abortion to a climate of suspicion around all pregnant patients. “People are increasingly scared even to be pregnant,” said Elizabeth Ling, senior helpline counsel at the reproductive justice legal group If/When/How. The fall of Roe has led to an ever-widening net of criminalization that can ensnare doctors, nurses, and pregnant people alike, leading to devastating consequences for patients’ health, experts say.

Complaints of pregnant women turned away from emergency rooms doubled in the months after Dobbs, the Associated Press reported earlier this year. Concerns about such treatment, combined with stories of people like Kate Cox, who was denied an abortion despite the risks her pregnancy posed to her health, have made some Americans afraid of conceiving: In one recent poll, 34 percent of women 18 to 39 said they or someone they knew had “decided not to get pregnant due to concerns about managing pregnancy-related medical emergencies.” Such surveys, along with ER records and calls to helplines, reveal a sense that in a post-Dobbs America, any pregnancy can be dangerous — to patients, to doctors, or both. “The fact that people are viewing the condition of pregnancy as something that makes them vulnerable to state violence is just so heartbreaking,” Ling said.

Americans are facing prosecution after miscarriage

The Dobbs decision has created an environment in which people experiencing miscarriage are treated as criminals or crimes waiting to happen, advocates say — or sometimes both. In October 2023, an Ohio woman named Brittany Watts visited a hospital, 21 weeks pregnant and bleeding. Doctors determined that her water had broken early and her fetus would not survive, but since her pregnancy was approaching the point at which Ohio bans abortions, a hospital ethics panel kept her waiting for eight hours while they debated what to do. She eventually returned home, miscarried, tried to dispose of the fetal remains herself, and was charged with felony abuse of a corpse. The charges were ultimately dropped, but experts say her case is part of a larger pattern. “There has become this hypersurveillance, hyperpolicing, hyperinterrogation” of pregnant people in America, said Michele Goodwin, a professor of constitutional law and global health policy at Georgetown and the author of Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood.

That surveillance isn’t entirely new, advocates and scholars say. Black pregnant women, especially, have been targets of suspicion for generations, stereotyped as drug users or “welfare queens” and even arrested when they tried to seek maternity care, said Goodwin. “There are cases of Black women having been dragged out of hospitals, literally in shackles and chains,” Goodwin said. Black women and other women and girls of color have also been disproportionately targeted for arrest or investigation following miscarriages or stillbirths. In 1999, Regina McKnight, a 22-year-old Black woman in South Carolina, became the first person prosecuted for homicide after experiencing a stillbirth, according to Capital B. She was convicted and sentenced to 12 years in prison for endangering her pregnancy through drug use, but her conviction was eventually overturned. But now, the atmosphere of criminalization around pregnancy is “spreading into wider and wider groups of people,” said Karen Thompson, legal director of the group Pregnancy Justice, which tracks the criminalization of pregnant people.

[...] The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) requires all hospitals that accept Medicare to stabilize the medical condition of anyone who arrives at an emergency room, including pregnant people. But the medical interventions allowed under new state abortion laws are often less than what EMTALA requires, Rosenbaum said. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court in the coming days will decide a case that could gut EMTALA, giving hospitals even more leeway to turn away pregnant patients.“I don’t think it’s an understatement to say that the loss of EMTALA, or even just weakening of EMTALA, puts pregnant people’s lives at risk,” Ling said.

2 years after the disastrous Dobbs verdict at SCOTUS, pregnancy in America feels like a crime, especially in states that have draconian abortion bans. Pregnancy-related prosecutions have occurred pre-Dobbs, but have expanded in scope in the post-Roe era.

#Pregnancy#Abortion#Criminalization of Abortion#Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization#Miscarriage#Brittany Watts#EMTALA#Moyle v. United States

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abortion pills are a vital option for millions of people nationwide following the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health this summer. But a lawsuit filed by a conservative Christian legal group threatens to dismantle the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval of abortion pills. If successful, it would effectively ban medication abortion nationwide — decimating what little access to abortion care is left “It would be apocalyptic,” Illinois state Rep. Kelly Cassidy (D) told HuffPost during a Thursday roundtable hosted by the State Innovation Exchange, a nonprofit organization working on public policy at the state level. The lawsuit was filed in November by the right-wing legal organization Alliance Defending Freedom on behalf of groups and doctors who oppose abortion. It claims that the FDA dangerously fast-tracked the approval of mifepristone, one of the two drugs used in medication abortion, in 2000. Mifepristone, along with the second drug used in medication abortion, misoprostol, is a safe and effective medication that accounts for over 50% of all abortion and miscarriage care in the U.S. A decision from the federal district court in Texas is expected soon — likely in the coming weeks. Although legal experts say the arguments in the lawsuit are weak, Alliance Defending Freedom intentionally filed in Amarillo, Texas, because suits filed there have a 100% chance of drawing Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, a far-right Trump appointee, according to University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck. Years of research have shown that medication abortion is extremely safe and effective. When used together, mifepristone and misoprostol are more than 95% effective and safer than Tylenol. The FDA currently approves its use up until 10 weeks of pregnancy, and the World Health Organization says mifepristone can be safely used until 12 weeks. Mifepristone is a “safe, effective and important component of treatment and management for early pregnancy loss ... and induced abortion,” the American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists wrote in a letter to the FDA in June.

1 note

·

View note

Text

An open letter to the U.S. Supreme Court

Abortion as reproductive healthcare is a right, PERIOD.

46 so far! Help us get to 50 signers!

A cadaver who holds viable organs ripe for life-saving donations can impact eight individual human lives. One citizen can save eight viable human beings, living breathing people with families, likely with social security numbers, even jobs, but most certainly: with economic investment in their very existence. But, without the express consent of a dead person, that means nothing. The body will be processed for eternal rest rendering its lifesaving organs useless to the living. As is legal, as is that cadaver’s right, the right to body autonomy.

Why then do the citizens of the United States come to hear that the supreme court is of the opinion that the same body autonomy granted to corpses in the face of documented citizens is not extended to women in the face of undocumented fetuses? It is the right of a person to decide what their body is used for, before death as well as after. This includes their reproductive rights. In fact, forced pregnancy is an assault on the human rights set forth by the United Nations (UN) of which the United States of America (USA) is a permanent member of. Denial of reproductive healthcare such as abortion is a violation of human rights.

Depending on the supreme court’s decision on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the already tenuous protections provided by Roe v. Wade will be entirely up for debate. Regardless of your personal beliefs on the morality of abortions, know that unprotected access to abortions will, and has already, resulted in women being charged with manslaughter over uncontrollable miscarriages, families weeping for doctors to abort miscarrying fetuses that are actively killing their beloved wives and mothers, women who are sentenced to death by pregnancy with a non-viable fetus. Even a healthy woman and fetus can, and do, turn deadly at a moment’s notice. To speak nothing on why a person might decide against the permanent body and life changes outside of concerns about mortality. Or how these policies disproportionately affect transgender people, people of color, and impoverished people. Or even how we have proof that reinforcing sexual education, access to birth control, paternity protections, and family welfare programs all are more cost-effective, more impactful, and more humane ways to decrease the rate of abortions.

To restrict access to reproductive healthcare, access to abortions, to any of these people, to do so will kill Americans. Do not cripple Roe v. Wade.

To quote Planned Parenthood, “Our bodies are our own — if they are not, we cannot be truly free or equal. Across the country, some politicians are trying to make decisions about our bodies for us. We won't let the abortion bans sweeping the country put our lives and futures at risk, and we won't be silenced while our fundamental right to control our bodies is taken away.

“Everyone deserves health care that's free of shame, stigma, or judgment. Together, we say: Get your bans off our bodies!”

▶ Created on May 26, 2022 by Ret. SGT Guild, Breeding Chattel

📱 Text SIGN PINRVQ to 50409

🤯 Liked it? Text FOLLOW IVYPETITIONS to 50409

#ivy petitions#PTKRPA#Abortion Is Healthcare#Reproductive Rights#Body Autonomy#My Body My Choice#Protect Roe V Wade#Abortion Rights Are Human Rights#No Forced Pregnancy#Healthcare Not Politics#Abortion Access For All#Stand With Planned Parenthood#Human Rights Violation#Womens Rights Are Human Rights#UN#Dobbs Vs Jackson#Stop The Abortion Bans#Forced Birth Is Violence#Health Not Hate#Protect Trans Rights#Equal Rights For All#Healthcare For Everyone#Gender Equality Now#Reproductive Justice#End The Stigma#Bodily Integrity#Pro Choice#Fund Abortion Providers#Abortion Is Essential#Say No To Forced Pregnancy

0 notes

Text

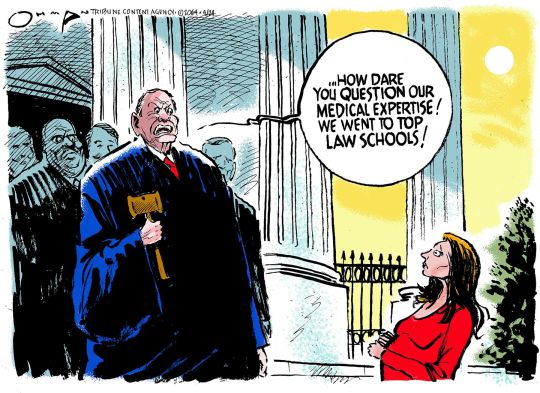

Jack Ohman, Tribune Content Agency

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

May 1, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

MAY 02, 2024

Today, Florida’s ban on abortions after six weeks—earlier than most women know they’re pregnant—went into effect. The Florida legislature passed the law and Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed it a little more than a year ago, on April 13, 2023, but the new law was on hold while the Florida Supreme Court reviewed it. On April 1 the court permitted the law to go into operation today.

The new Florida law is possible because two years ago, on June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that recognized the constitutional right to abortion. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the modern court decided that the right to determine abortion rights must be returned “to the people’s elected representatives” at the state level.

Immediately, Republican-dominated states began to restrict abortion rights. Now, one out of three American women of childbearing age lives in one of the more than 20 states with abortion bans. This means, as Cecile Richards, former president of Planned Parenthood, put it in The Daily Beast today, “child rape victims forced to give birth, miscarrying patients turned away from emergency rooms and told to return when they’re in sepsis.” It means recognizing that the state has claimed the right to make a person’s most personal health decisions.

Until today, Florida’s law was less stringent than that of other southern states, making it a destination for women of other states to obtain the abortions they could not get at home. In the Washington Post today, Caroline Kitchener noted that in the past, more than 80,000 women a year obtained abortions in Florida. Now, receiving that reproductive care will mean a trip to Virginia, Illinois, or North Carolina, where the procedure is still legal, putting it out of reach for many women.

This November, voters in Florida will weigh in on a proposed amendment to the Florida constitution to establish the right to abortion. The proposed amendment reads: “No law shall prohibit, penalize, delay, or restrict abortion before viability or when necessary to protect the patient’s health, as determined by the patient’s healthcare provider.” Even if the amendment receives the 60% support it will need to be added to the constitution, it will come too late for tens of thousands of women.

It is not unrelated that this week Texas attorney general Ken Paxton, along with other Republican attorneys general, has twice sued the Biden administration, challenging its authority to impose policy on states. One lawsuit objects to the government’s civil rights protections for sexual orientation and gender identity. The other lawsuit seeks to stop a federal rule that closes a loophole that, according to Texas Tribune reporter Alejandro Serrano, lets people sell guns online or at gun shows without conducting background checks.

In both cases, according to law professor and legal analyst Steve Vladeck, Paxton has filed the suit in the Amarillo Division of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, where it will be assigned to Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, the Trump appointee who suspended the use of mifepristone, an abortion-inducing drug, in order to stop abortions nationally.

Last month the Judicial Conference, which oversees the federal judiciary, tried to end this practice of judge-shopping by calling for cases to be randomly assigned to any judge in a district; the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas says it will not comply.

And so the cases go to Kacsmaryk, who will almost certainly agree with the Republican states’ position.

Republicans are engaged in the process of dismantling the federal government, working to get rid of its regulation of business, basic social welfare laws and the taxes needed to pay for such measures, the promotion of infrastructure, and the protection of civil rights. To do so, they have increasingly argued that the states, rather than the federal government, are the centerpiece of our democratic system.

That democracy belonged to the states was the argument of the southern Democrats before the Civil War, who insisted that the federal government could not legitimately intervene in state affairs out of their concern that the overwhelming popular majority in the North would demand an end to human enslavement. Challenged to defend their enslavement of their neighbors in a country that boasted “all men are created equal,” southern enslavers argued that enslavement was secondary to the fact that voters had chosen to impose it.

At the same time, though, state lawmakers limited the vote in their state, so the popular vote did not reflect the will of the majority. It reflected the interests of those few who could vote. In 1857, enslaver George Fitzhugh of Virginia explained that there were 18,000 people in his county and only 1,200 could vote. “But we twelve hundred…never asked and never intend to ask the consent of the sixteen thousand eight hundred whom we govern.” State legislatures, dominated by such men, wrote laws reinforcing the power of a few wealthy, white men.

Crucially, white southerners insisted that the federal government must use its power not to enforce the will of the majority, but rather to protect their state systems. In 1850, with the Fugitive Slave Act, they demanded that federal officials, including those in free states, return to the South anyone a white enslaver claimed was his property. Black Americans could not testify in their own defense, and anyone helping a “runaway” could be imprisoned for six months and fined $1,000, which was about three years’ income. A decade later, enslavers insisted that it was “the duty of the Federal Government, in all its departments, to protect…[slavery]…in the Territories, and wherever else its constitutional authority extends.”

After the Civil War, Republicans in charge of the federal government set out to end discriminatory state legislation by adding to the Constitution the Fourteenth Amendment, establishing that states could not deny to any person the equal protection of the laws and giving Congress the power to enforce that amendment. That, together with the Fifteenth Amendment providing that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” Republicans thought, would stop state legislatures from passing discriminatory legislation.

But in 1875, just five years after Americans added the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, the Supreme Court decided that states could keep certain people from voting so long as that discrimination wasn’t based on race. This barred women from the polls and flung the door open for voter suppression measures that would undermine minority voting for almost a century. Jim and Juan Crow laws, as well as abortion bans, went onto the books.

In the 1950s the Supreme Court began to use the Fourteenth Amendment to end those discriminatory state laws—in 1954 with the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, decision that prohibited racial segregation in public schools, for example, and in 1973 with Roe v. Wade. Opponents complained bitterly about what they called “judicial activism,” insisting that unelected judges were undermining the will of the voters in the states.

Beginning in the 1980s, as Republicans packed the courts with so-called originalists who weakened federal power in favor of state power, Republican-dominated state governments carefully chose their voters and then imposed their own values on everyone.

Just a decade ago, reproductive rights scholar Elizabeth Dias told Jess Bidgood of the New York Times, a six-week abortion ban was seen even by many antiabortion activists as too radical, but after Trump appointed first Neil Gorsuch and then Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, the balance of power shifted enough to make such a ban obtainable. Power over abortion rights went back to the states, where Republicans could restrict them.

Trump has said he would leave the issue of abortion to the states, even if states begin to monitor women’s pregnancies to keep them from obtaining abortions or to prosecute them if they have one.

Vice President Kamala Harris was in Jacksonville, Florida, today to talk about reproductive rights. She put the fight over abortion in the larger context of the discriminatory state laws that have, historically, constructed a world in which some people have more rights than others. “This is a fight for freedom,” she said, “the fundamental freedom to make decisions about one’s own body and not have their government tell them what they’re supposed to do.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#history#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#corrupt SCOTUS#rule of law#women#women's rights#human rights#states rights#Civil War#slavery#white Southerners#fugitive slave act#income inequality#wealthy white men#Fifteenth amendment

3 notes

·

View notes

Text