#july monarchy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

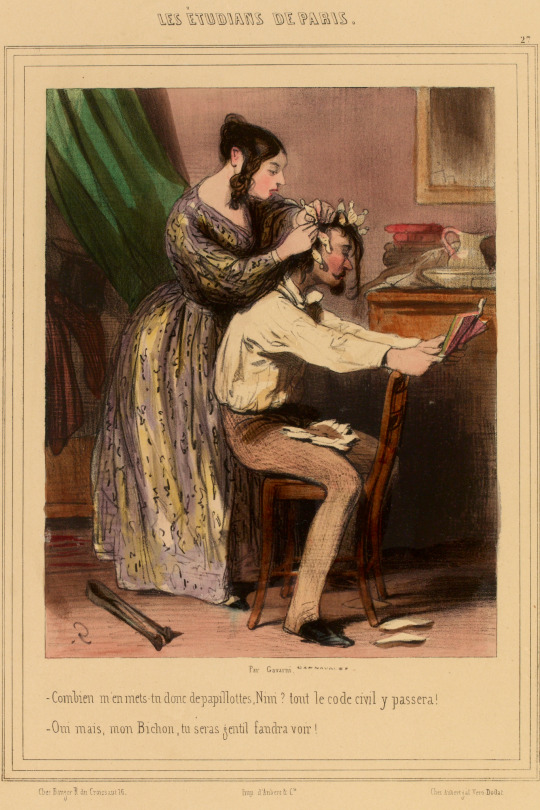

Another wonderful and adorable men's haircurling scene circa 1840 by Paul Gavarni, this one in high quality! (Paris Musées). Dated 1839-1841, in the "Students of Paris" series, the dialog goes something like:

How many papillotes are you going to give me, Nini? I'll have read the entire civil code!

Yes but, sweetie, you're going to look so nice!

He has papillotes on his lap, there are curling tongs and more papillotes on the floor. His hair is chin-length, showing how long men's hair is at this time, he's in his shirtsleeves—it's so intimate and cute.

eta: thanks to @daffenger and @sainteverge, who suggested a better translation of the dialog that makes it even more amusing: he's actually saying that they're about to run out of the civil code, which is being used to make his curl papers!

#paul gavarni#1830s#1840s#men's fashion#july monarchy#historical hairstyles#historical hair curling#papillotes#hair curling#looks much more 1840s than 1830s#i love them your honor#she looks so nurturing#i love you mister gavarni

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fighting at the rue Saint-Antoine barricade, 1830

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

French History Primer for Les Mis Fans

Or: an extremely informal, somewhat rude, unashamedly biased, probably not-100%-accurate summary of post-Revolutionary French history for people who want to know what the fuck Victor Hugo was talking about.

Most of this was originally written for the entertainment and edification of a fail_fandomanon thread back in April. If you know the basic succession of governments from 1789 to 1851 nothing in here will be news to you, but I'm not sure there is a historical-context-101 writeup for new fans or people who have yet to dip their toes into the history side of things. And that's something that, as an oldfandom person and a history nerd, I should've done my part to rectify back at the very beginning of post-movie fandom to help make canon era more accessible to everyone, but hey, better late than never, right?

This is a long post, but it's a single post, and better a long post than either an inadequate one-page summary or an endless series of Wikipedia articles that all assume you know the context from the surrounding articles. It doesn't even attempt to tackle the French Revolution, but presumably you remember at least a garbled basic version of that from history class or, like, the Wishbone Tale of Two Cities episode or wherever else cultural osmosis comes from.

So what even HAPPENED in France post-Revolution?

Okay! Um, basically Napoleon happened post-Revolution. After the Terror--which your humble correspondent has A Lot Of Feelings about, mostly that it was an extreme situation where everyone was being terrible and the fact that the bloodthirsty infighting within Robespierre's faction is the only part that's remembered amounts to a spectacular propaganda job--right, where was I? After the Terror France straggled along under the dysfunctional government of the Directory, and then Napoleon swept in on a wave of military glory. (Because there had been a war on for the past decade. Because all the other monarchies in Europe were scared shitless by the Revolution and declared war on France, resulting in aforementioned extreme situation. Except France not only held them off singlehandedly but decided this was fun and started liberating--or 'liberating'--its neighbors from their assorted kings.) Anyway, Napoleon swept in from the Italian campaign, helped stage a coup d'état that installed him as First Consul in a triumvirate, then crowned himself Emperor and decided to go liberate conquer Europe in the name of... the revolution or something, except he was running a military dictatorship back home. This went on for a long time. A long time. It would've gone on even longer if Napoleon hadn't decided it would be a great idea to invade Russia. That went about as well as one might imagine, and ended in the Allies Coalition invading Paris in 1814 and replacing Napoleon with... a king. The younger brother of the one who got guillotined, in fact. Napoleon they exiled to the island of Elba in the Mediterranean, which proved to be an exceedingly poor life choice, because within nine months he'd hitched a ride back to the mainland and then all he had to do was walk back up to Paris to accrue an army as he went. Yeah, the first attempt to restore the monarchy didn't last very long. Of course, neither did Napoleon--his second term is known as the Hundred Days, because that's about how long it took for him to look at the odds (France vs. Britain, Prussia, Russia, Austria, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Sweden, fucking Switzerland, and a royalist insurrection back home), decide the logical thing to do was to go on the offensive, and get his ass handed to him by the Brits and the Prussians at Waterloo. So that was the end of that. This time Napoleon got exiled to St Helena, which is a desolate fucking rock smack in the middle of the South Atlantic, and stayed there until he died in 1821. Meanwhile Louis XVIII, the same king as before, got back on the throne and tried to turn back the clock from 1815 to 1788. He... sort of made it work, as a constitutional monarchy with emphasis on 'monarchy', mostly because he was boring and everyone was too tired to make a fight of it. But below the surface were a bunch of disaffected Napoleonic veterans, a generation of disaffected kids born during the war and unimpressed by their lack of opportunities in a government full of geriatric aristocrats flooding back into France, a silenced working class, and in the actual corridors of power, liberal-ish constitutional monarchists versus a batshit extremist right wing (the legitimists or ultraroyalists, also called carlists after 1830) calling for everything to be exactly like it had been before the Revolution. On the outside, though, the Restoration was pretty fucking boring.

And then Louis XVIII died and his younger brother Charles X got the throne. Charles X was an ultraroyalist. It is, frankly, a miracle that he lasted six years before he tried to pull off some electoral fuckery to rig the legislature, made the giant mistake of trying to muzzle the press while he was at it, and got himself unceremoniously booted out in the July Revolution of 1830. After the July Revolution there were calls for a republic, but it wound up getting hijacked by aggressively moderate constitutional monarchists who installed Louis-Philippe on the throne. L-P was from a junior branch of the royal family (the Orléans line, as opposed to the Bourbon line of the Restoration), his father had thrown his lot in with the Revolution back in the day, and he was almost more bourgeois than aristocratic. So he represented a decent compromise for almost everybody, but I'm not sure anyone was happy with him except the middle classes. The republicans and the legitimists, at least, were both spitting mad and kept staging rebellions all through the 1830s. Which brings us back up to 1832.

OR, SHORT SNAPPY SUMMARY: Revolution, Napoleon until Waterloo (1815), conservative restoration of the monarchy until the July Revolution (1830), moderate/bourgeois July Monarchy under Louis-Philippe until the revolution of 1848. And then all hell broke loose.

"But what even happens to France after the end of Les Mis? Does the Les Amis uprising inspire any further social movement or was it an isolated disaster?"

France continued on for another sixteen years industrializing under its very bourgeois monarchy (like, this is where the term "laissez-faire capitalism" originated), which kind of dragged it from being a fight over what form of government they should have into an outright class struggle. The thing about the 1832 uprising is that they grokked two years into the July Monarchy that this was all a bad idea and France would be better off with representative democracy, and then they all got shot for it because it took the rest of France eighteen years to get the memo. Maybe it would've happened sooner, but Louis-Philippe, who sweet-talked his way onto the throne after the revolution of 1830 by making all sorts of promises about popular sovereignty and revolutionary heritage and freedom and reform and stability, spent the rest of the decade progressively cracking down on freedom of the press and getting increasingly nasty about putting down revolts in order to maintain his grip on the throne. To drag in a Doctor Who metaphor, 1832 is a fixed point in time and space: something like it would always have happened, because the movement in favor of a republic still had enough momentum that it would've broken into outright revolt sooner or later, but it also had to fail for history to stay on course, because it was in the industrial pressure cooker of the 1830s and 40s that communism was born.

(Obviously the industrial pressure cooker and the beginnings of communism weren't only going on in France, but in both 1830 and 1848, France having a revolution set off an Arab-Spring-esque series of revolts all across Europe. The gun was loaded, it was mostly a question of when the trigger would get pulled. Fuck knows what would've happened if it'd been pulled in 1832, when socialism was still in its theoretical, pacifistic Saint-Simonian infancy, instead of 1848.)

Back up a second, you said all hell broke loose. What happened in 1848?

Your humble correspondent is not at all comfortable presenting herself as an authority on the Second Republic, the June Days, or the Second Empire or analyzing the issues involved, because this is where things get extraordinarily messy. And when I say messy, I mean they fucked up Victor Hugo's convictions so badly that his capital-f Feelings about 1848 and 1851 are what drive a lot of the politics in Les Mis--so shit, I have to talk about this, don't I?

In brief, Louis-Philippe was ousted in the revolution of February 1848 and this time, an actual Republic was set up. But it was characterized by a growing split between the working classes and the increasingly conservative 'mainstream' republican government, exacerbated by the worsening of the financial crisis of the years leading up to the 1848 revolution and by the right-to-work initiative that led to the expensive failure of the National Workshops. The closure of the workshops threatened an already-destitute population with mass unemployment. In June 1848, the 'red' proletarian neighborhoods of Paris rose up in insurrection, and the government mounted a brutal repression that led to a large-scale massacre of the rebels. Victor Hugo participated in this insurrection--on the side of the government. He was conflicted, had plenty of sympathy for the insurgents, and his involvement consisted mainly of trying to convince them to lay down their arms and prevent bloodshed, but he was still on the side of maintaining the legitimacy of the new republican government, and thus on the side of the repression. The June Days drove an enormous rift into French left-wing politics, and Hugo tried to straddle that rift for pretty much the rest of his life--when he spends pages talking about riot vs. revolution, that's his ambivalence and attempts to rationalize his own actions talking.

So what happened in 1851? The Second Republic staggered along for another couple of years, on an increasingly repressive and conservative tone, and then Napoléon Bonaparte's nephew Louis-Napoléon was elected President. It didn't take long for him to repeat history, stage a coup d'état, and declare himself Emperor--and that, December 1851, is when Hugo declared himself a revolutionary and tried to lead a revolt against the newly-proclaimed Napoléon III. The revolt failed, and Hugo went into exile, shifting around into various places before settling on Guernsey in the Channel Islands.

Hugo had mixed feelings about the original Napoléon--having grown up in a divided household, with a Royalist mother and a father who was a general in the Imperial army--and considered him both a tyrant and an emblem of national glory. But his views on Louis-Napoléon were utterly unambiguous; he hated the man's guts, regarded him as having all of his uncle's vices and none of his virtues, and attacked him in both poetry and prose with Les Châtiments, Napoléon le Petit, and The History of a Crime. The Second Empire was still in full swing when he published Les Misérables in 1862, and the political subtext of the book can usually be traced back to either Hugo's Feelings On the June Days or Hugo's Feelings On the Bonaparte Family.

(Hugo's hatred of Louis-Napoléon extended into another realm, too: the destruction of historic Paris in the name of urban improvement, which had been an obsession of his even as an up-and-coming writer in his 20s--Notre-Dame de Paris may or may not have singlehandedly saved the cathedral from demolition--but reached its height during the Second Empire. That was the era of the Baron Haussmann's large-scale destruction of the old Parisian neighborhoods to make way for broad boulevards and public-works projects that irrevocably gentrified central Paris and displaced the poor out to the outskirts of the city. Keep this subtext in mind and I guarantee you the digression on the Paris sewers will become a lot more interesting.)

And... I think that's it for the broad outlines of the history behind Les Misérables? Unless you want to get into religion, which I am eminently unqualified to pontificate about, except that it usually boils down to Hugo's beliefs on Christianity as a force for progressivism vs. Hugo's stinkeye directed at the conservative, regressive Catholic establishment and its perpetual grasping after the political and social stranglehold it had wielded before the Revolution. (See also: Hugo's appreciation of the humanistic and scientific progress of the Enlightenment vs. Hugo's suspicion of the Enlightenment's atheistic tendencies and reductive over-reliance on rationalism vs. Hugo's utter disdain for the bourgeoisie's selective appropriation of Enlightenment philosophy to excuse social Darwinism.) (Which brings us to classics vs. classicism vs. romanticism, which is a whole other ball of wax and this post is long enough, jesus. Somebody shut me up already.)

#french history#victor hugo#les misérables#les miserables#july monarchy#resources#history geeking ahoy#my stuff

402 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Organization of the National Guard

A few notes on the organization of the National Guard in Paris at the time of the June Rebellion.

The National Guard is organized into legions, which are subdivided into battalions. (Any time you see Hugo mention a legion in the Paris chapters, he’s talking about a National Guard unit rather than a Municipal Guard unit or an army unit – the army is organized into regiments in this era.) There are thirteen Parisian legions, one for each arrondissement* plus a cavalry unit. In addition, there are four legions from the suburbs.

Parisian legions, quite sensibly, take the number of their arrondissement. Each legion is comprised of four battalions, one for each quartier. The Thirteenth Legion is the cavalry unit and covers the whole of the city.

The banlieue legions each correspond to two of the cantons surrounding Paris. The First Legion covers Saint-Denis and Pantin, the Second covers Courbevoie and Neuilly, the Third covers Sceaux and Villejuif, and the Fourth covers Vincennes and Charenton. Within the legions, each battalion corresponds to a different commune or handful of communes. I’ve put the full list up here.

This means that if you know anyone’s home address, you can figure out which National Guard unit they’d be assigned to, and likewise you can trace people’s address (or at least their arrondissement) from their legion number.

Some Points of Interest

Jean Valjean/Fauchelevent is registered for guard duty at his Rue Plumet address, so he’s in the Tenth Legion.

The Sixth Legion whose standard Enjolras spots on his dawn reconnaissance is the legion that corresponds, to a first approximation**, to the neighborhood of the barricade. It’s interesting that they even mustered, as the 6th arrondissement is not particularly wealthy and it’s right at the center of the fighting. During the June Days some of the National Guard units from the rebellious arrondissements stayed home or defected to the side of the insurgents, but that clearly isn’t happening here. It indicates to a certain degree the lack of popular support for the rebellion – it’s not just legions from the richer neighborhoods in the western half of the city and the outlying suburbs that are being marched in to knock down barricades in the slums; the local unit has also turned out to fight against the insurgents.

Of course, the National Guard isn’t exactly an unbiased sample of the neighborhood, since Louis-Philippe had purged it of everyone who couldn’t pay for their own weapons and uniform, but I think the choice of legion was very deliberate on Hugo’s part. This is the point at which Enjolras realizes the rest of Paris is not going to join the revolt and the barricade is doomed, because he’s seen the banner of the local National Guard unit arrayed alongside the rest of the forces of order. The people have risen, but they’re fighting on the wrong side.

* Under the the old twelve arrondissement system in place at the time

** The barricade itself is actually on the border of the 4th and 5th arrondissements, because the layout of the old arrondissement system was ridiculous. But the 6th arrondissement covers the neighborhood on the other side of the Rue Saint-Denis, which is the main thoroughfare the barricade is theoretically guarding (to the extent it’s guarding anything besides Grantaire’s wine supply).

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Speech before La Société des Amis du Peuple

Speech given by Louis Auguste Blanqui to La Société des Amis du Peuple in 1832...of interest to those wondering about the milieu around the 1832 rising. La Société des Amis du Peuple is one of the sources of inspiration for Les Amis de l'ABC.

The fact shouldn’t be hidden that there is a war to the death between the classes that compose the nation. This truth recognized, the truly national party, the ones patriots should rally to, is the party of the masses.

Until now there have been three interests in France: that of the so-called upper classes, that of the middle or bourgeois class, and finally that of the people. I place the people last because they were always the last and because I count on an imminent application of the Gospel maxim that “the last shall be first.”

In 1814 and 1815 the bourgeois class, tired of Napoleon not because of despotism (it cares little for liberty, which in its eyes it isn’t worth a pound of good cinnamon or a nice fat bill), but because the blood of the people being exhausted, the war was beginning to take its children from it and, even more, because it harmed its tranquility and hindered commerce. The bourgeois class then received the foreign soldiers as liberators and the Bourbons as God’s envoys. They were the ones who opened the gates of Paris, who treated the soldiers of Waterloo as brigands, and who encouraged the bloody reaction of 1815.

Louis XVIII rewarded them with the Charter. This Charter established the upper classes as an aristocracy and gave the bourgeois the Chamber of Deputies, called the democratic chamber. With this the émigrés, the nobles, the big landowners who were fanatical partisans of the Bourbons, and the middle class who accepted them from self-interest found themselves the masters in equal part of the government. The people were pushed to the side. Bereft of leaders, demoralized by foreign invasion, having lost faith in liberty, they remained silent and submitted to the yoke while remaining on their guard. You know the consistent support the bourgeois class gave the Restoration until 1825. It loaned its hand to the massacres of 1815 and 1816, to the scaffolds of Borie and Berton, to the war in Spain, to the arrival of Villèle and the changes in the electoral law; until 1827 it regularly sent majorities given over to those in power.

In the period 1825-1827 Charles X, seeing that he was succeeding at everything and believing himself strong enough without the bourgeois, wanted to proceed to their exclusion, as was done with the people in 1815. He took a daring step towards the Ancien Régime and declared war on the middle class by proclaiming the exclusive dominance of the nobility and clergy under the banner of Jesuitism. The bourgeoisie is by essence anti-spiritual: it detests churches, and believes only in double entry bookkeeping. The priests irritated them: they had consented to share with the upper classes in oppressing the people, but seeing its turn arrive as well, full of resentment and jealousy against the high aristocracy, it rallied to that minority of the middle class that had combated the Bourbons since 1815 and that it had sacrificed up till then. It was then that a war of newspapers and elections began, carried out with so much steadfastness and fury. But the bourgeois fought in the name of the Charter and nothing but the Charter, and in fact the Charter assured their power. Faithfully executed, it gave them supremacy within the state. Legality was invented to represent this interest of the bourgeoisie’s and to serve as its flag. The legal order became a kind of divinity before which constitutional opponents burned their daily incense. This struggle was carried out from 1825 -1830, ever more favorably to the bourgeois, who rapidly gained ground and who, masters of the Chamber of Deputies, soon threatened the government with complete defeat.

What were the people doing in the midst of this conflict? Nothing. They remained a silent spectator to the quarrel, and everyone knows that its interests didn’t count in the debates of its oppressors. To be sure, the bourgeois cared little about them and their cause, which were looked on as having been lost fifteen years before. You recall that the papers most devoted to the constitutionals regularly repeated that the people had submitted their resignation to their representatives, the only organs of France. It wasn’t only the government that considered the masses as indifferent to the debate: the middle classes detested them perhaps even more, and they surely counted on being the only ones to pluck the fruits of victory. That victory didn’t go further than the Charter. Charles X and the Charter with an all-powerful bourgeoisie, this was the goal of the constitutionals. Yes, but the people understood the question differently. The people mocked the Charter in execrating the Bourbons. Seeing its masters argue among themselves it spied out in silence the moment to leap onto the battlefield and bring the parties into agreement.

When the classes arrived at such a point that the government no longer had any resource than coups d’état, and that that threat of a coup d’état was suspended over the heads of the bourgeois, then they were gripped with fear! Who doesn’t recall the regrets and terrors of the 221 after the order of dissolution that answered their famous address? Charles X spoke of his firm resolve to resort to force, and the bourgeoisie blanched. Already most of them loudly disapproved the 221 for having allowed themselves to be carried away by revolutionary excesses. The most daring placed their hope in the refusal of a tax that would have been paid and in the support of tribunals, almost all of who would gladly have filled the office of summary political courts. If the royalists demonstrated so much confidence and resolution, if their adversaries showed so much fear and uncertainty, it’s that both regarded the people as having resigned themselves and expected to find them neutral in the battle. And so on one hand the government depended on the nobility, the clergy and the big landowners, and on the other was the middle class which, after five years of warming up in a war of words, was ready to come to blows with the people, silent for fifteen years and believed resigned.

It was in these conditions that the combat was engaged. The ordinances were issued and the police smashed the newspaper presses. I won’t speak of our joy, citizens, we who are shaking the yoke and who are finally witnessing the reawakening of the popular lion that had slept for so long. July 26 was the most beautiful day of our life. But the bourgeois! Never has a political crisis offered a spectacle of such frightful, such profound consternation. Pale, frantic they heard the first shots as the first discharge of a picket that was to shoot them down one by one. You all remember the conduct of the deputies on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. They used what presence of mind and faculties fear left to them to ward off, to halt the combat. Preoccupied with their own cowardice, they were unready to foresee popular victory and were already trembling beneath Charles X’s knife. But on Thursday the scene changed. The people were the victors. And then another terror seized them, more profound and oppressive. Farewell dreams of the Charter, of legality, of constitutional royalty, of the exclusive domination of the bourgeoisie! The powerless ghost that was Charles X faded away. In the midst of the debris, of flames and smoke, the people appeared standing on the corpse of royalty, standing like a giant, the tricolor flag in hand. They were struck with stupor. It was then that they regretted that the National Guard didn’t exist July 26, that they condemned the lack of foresight and the folly of Charles X, who had smashed the anchor of his own salvation. It is too late for regrets! You can see that during these days, when the people were so grand, the bourgeois were tied up between two fears, that of Charles X in the first place, and then that of the workers. A noble and glorious role for these proud warriors who float their high plumesat parades on the Champ de Mars.

But citizens: how is it that so sudden and fearsome a revelation of the force of the masses remained sterile? By what fatality did that revolution made by the people alone, and that should have marked the end of the exclusive reign of the bourgeoisie as well as the success of popular interests and might, have no other results than the establishing of the despotism of the middle class, aggravating the poverty of the workers and peasants, and plunging France a bit further into the mud? Alas, the people, like the other old man, knew how to win, but not how to profit from its victory. The fault is not all their own. The combat was so brief that its natural leaders, those who would have led the way to victory, didn’t have the time to distinguish themselves from the crowd. They necessarily rallied to the leaders who had figured at the head of the bourgeoisie in the parliamentary struggle against the Bourbons. What is more, they were grateful to the middle classes for their little five year war against their enemies, and you have seen what benevolence, I would almost say what feeling of deference they showed towards those men in suits they met on the streets after the battle. That cry of “Long Live the Charter!” which was so perfidiously abused was nothing but a rallying cry for proving its alliance with these men. Did they already feel, as if by instinct, that they had just played a nasty trick on the bourgeoisie and, in the generosity of the victor, did they want to make advances and offer peace and friendship to their future adversaries? Whatever the case, the masses hadn’t formally expressed any positive political will. What acted on them, what had thrown them into the public square, was the hatred of the Bourbons, the firm resolution to overthrow them. There was both Bonapartism and the Republic in the wishes they formed for the government that was to issue from the barricades.

You know how the people, in its confidence in the chiefs they’d accepted and which their ancient hostility to Charles X made them consider them as equally implacable enemies of the entire Bourbon family, retired from the public squares once the battle was finished. At that point the bourgeois came out of their cellars and threw themselves in their thousands onto the streets, which the departure of the combatants had left free. There is no one who doesn’t remember with what amazing suddenness the scene changed on the streets of Paris, like at a theatre; the way suits replaced work jackets, in the blink of an eye, as if a fairy wand had made some disappear and others spring up. This was because the bullets were no longer flying. It was no longer a question of receiving blows, but of gathering up loot. To each his role: the men of the workshops disappeared, the men who work behind the counter appeared.

It was then that the wretches who had been given victory as a deposit, after having attempted to place Charles X back on his throne, feeling that their lives were at risk and lacking the courage to brave the dangers of such a treason, stopped at a less perilous treason. A Bourbon was proclaimed king. Under the direction of agents paid with royal gold 10-15,000 bourgeois put in place in the courts of the new palace saluted the master for a few days with their cries of enthusiasm. As for the people, since they have no dividends and lack the means to stroll beneath the windows of palaces, they were in the workshops. But they weren’t accomplices in this unworthy usurpation that would not have occurred had they found men capable of guiding their angry and vengeful blows. Betrayed by their chiefs, abandoned by the schools, they remained silent and on their guard, as in 1815. I’ll cite you as an example a coachman who drove me last Saturday. After having told me of the part he played in the combats of the three days he added: “ On the way to the Chamber I encountered the procession of deputies headed towards the Hotel de Ville. I followed them to see what they’d do. Then I saw Lafayette appear on the balcony with Louis-Philippe and say, ‘Frenchmen, here is your King.’ Sir, when I heard that word it was as if I’d been stabbed. I was blinded; I went on my way.” That man is the people.

This then was the situation of the parties immediately following the July Revolution. The upper class was crushed; the middle class, which hid itself during the combat and disapproved it, demonstrating as much cleverness as it did prudence, snatched the fruits of victory that were won despite them. The people, who did everything, remained a zero, as before. But a terrible act has been accomplished: like a thunderbolt, the people had suddenly entered the political scene that they took by assault, and though more or less chased from it at the same instant, they nevertheless acted with mastery. They withdrew their resignation. It will henceforth be between them and the middle class that bitter war will be carried out. It’s no longer between the upper classes and the bourgeois: in order to better resist, the latter will need to call their former enemies to their assistance. In fact, for a long time the bourgeoisie has not hidden its hatred of the people.

If we examine the conduct of the government there is in its policies, the same march, the same progression of hatred and violence as among the bourgeoisie, whose interests and passions it represents.

When the bricks of the barricades were still piled up in the streets all that was spoken of was the program of the Hotel de Ville, of republican institutions; handshakes, popular proclamations, the grand words of liberty, independence, and national glory were bandied about. And then, when those in power had at their disposal an organized military force, pretensions mounted; all the laws, all the ordinances of the Restoration were invoked and applied. Later, the prosecution of the press, the persecutions of the men of July, the people beaten and tracked down with bayonet blows, taxes increased and collected with a rigor unheard of under the Restoration: this entire apparatus of tyranny revealed the governments hatreds and fears. But it felt that the people felt that same hatred for them, and not judging itself strong enough with the support of the bourgeoisie alone it sought to rally the upper classes to its cause in order that, established on this dual base, it would be in a state to more successfully resist the threatened invasion of the proletarians. It is to this maneuver to conciliate the aristocracy that we should attach the system it has developed in the past eighteen months. This is the key to its policy. And this upper class is almost entirely composed of royalists. In order to bring them along it was thus necessary to as nearly as possible approach the Restoration, to follow its meanderings, to continue them. And this is what was done. Nothing was changed except the name of the king. The people’s sovereignty was denied, trod upon. The court wore mourning attire for foreign princes, legitimacy was copied in all regards. Royalists were maintained in their places, and all those who had to leave in the first onrush of the revolution found more lucrative positions; the magistracy was preserved in such a way that the whole administration is in the hands of men devoted to the Bourbons. What is more, a part of this upper class, the most rotten part of it, that which above all wants gold and pleasures, deigned to promise its protection to public order. But the other part, the one I’ll call the least rotted in order not to say “ honorable,” that which has self-respect and faith in its opinions, which worships its flag and its old memories, these people reject with disgust the caresses of the middle way. They have behind them the largest part of the populations of the south and the west, all those peasants of the Vendée and Brittany who, having remained foreign to the movement of civilization, preserve an ardent faith in Catholicism, and with reason confound in their devotions Catholicism with legitimacy, for these are two things that have lived and must die together.

Do you think that these simple and believing men are open to the seductions of bankers? No, citizens! For the people, whether if in their ignorance they are enflamed with religious fanaticism or if, more enlightened, they allow themselves to be carried away by enthusiasm for liberty, the people are ever great and generous; they don’t obey low monetary interests but the nobler passions of the soul, the aspirations of elevated morality. But however delicately and deferentially we might handle Brittany and the Vendée, they are still ready to rise at the cry of “God and King” and threaten the government with their Catholic and royal armies, which the first shock will smash. And that’s not all: that faction of the upper classes that attached itself to the middle way will abandon it at the first moment. All they promised was to not work to overthrow them. As for devotion, you know it’s possible to have it towards coupon clippers. Even more, I’d say that the greatest part of the bourgeois, who are pressing, gathering around the government from hatred of the people who they fear, from fright at war, which they have a horror of for they think it’ll take their écus from them, these bourgeois barely care for the current order; they feel it to be powerless to protect them. Let the white flag [of the Royalists] come along that would guarantee them the oppression of the people and material security and they’d be ready to sacrifice their former political pretensions, for they bitterly regret having, through pride, sapped the power of the Bourbons and prepared their fall. They would abdicate their part of power to the hands of the aristocracy, willingly trading tranquility for servitude.

For the government of Louis-Philippe hardly reassures them. It can copy the Restoration all it wants, persecute patriots, set itself to erasing the stain of insurrection it is soiled with in the eyes of the adorers of public order. The memory of those three terrible days pursues them, dominates them. Eighteen months of successful war against the people were unable to counter-balance one sole popular victory. The battlefield is still theirs and that already old victory is suspended over power’s head like the sword of Damocles. All are looking to see if the thread is not soon going to break.

Citizens, two principles share France, that of legitimacy and that of popular sovereignty. The first is the ancient organization of the past. This is the framework society lived in for 1400 years, and that some want to preserve by instinct of self-preservation, and others because they fear that the framework won’t be able to be promptly replaced and anarchy will follow its dissolution. The principle of popular sovereignty rallies all men of the future, the masses who, tired of being exploited, seek to smash the framework that suffocates them. There is no third flag, no middle term. The middle road is foolishness, a bastard government that wants to give itself airs of legitimacy that one can only laugh at. And so the royalists, who perfectly understand this situation, profit from the tact and indulgence of those in power who seek to bring them over to them so as to more actively work at their destruction. Their many newspapers demonstrate daily that the only possible order is legitimacy, that the middle road is powerless to constitute the country, that apart from legitimacy there is only revolution and once the first has been left behind, there is only the second.

What will then happen? The upper classes are waiting for the moment to raise the white flag. In the middle class the great majority, composed of those men who have no other homeland than their counter or their cash box, who would gladly become Russian, Prussian, or English to earn two liards on a piece of cloth or 1/4 % additional profit on discount, will without fail line themselves up behind the white flag. The very name of war and popular sovereignty makes them tremble. The minority of that class, made up of intellectual professions and the small number of bourgeois who love the tricolor flag, the symbol of France’s independence and freedom, will take the side of popular sovereignty.

What is more, the moment of disaster is rapidly approaching. You see that the Chamber of Peers, the magistracy, and most civil servants are openly conspiring for the return of Henri V, mocking the middle road. Legitimist gazettes no longer hide either the hopes or the projects of the counter-revolution. The royalists in Paris and the provinces are gathering their forces, organizing the Vendée and Brittany, and are proudly planting their banner. They are openly saying that the bourgeoisie is with them, and they aren’t wrong. They are only waiting for a signal from foreign lands to raise the white banner, for in foreign countries they would be crushed by the people. They know this and we are counting on their being crushed, even with foreign support.

You can be assured Citizens that they will not want for this support. This is the place to take a look at our relations with the European powers. It should be noted, in fact, that the external situation has developed in parallel with the political march of the government internally. External shame has grown in the exact same proportion as bourgeois despotism and the poverty of the masses internally.

At the first sound of our revolution the kings lost their heads, and the electric spark of insurrection having rapidly set Belgium, Poland, and Italy aflame, they sincerely thought their last day had arrived. How could it be imagined that the revolution didn’t mean a revolution, that the expulsion of the Bourbons didn’t mean the expulsion of the Bourbons, that the overturning of the Restoration would be a new edition of the Restoration? Not even the maddest of individuals could believe this. The cabinets saw in the three days the awakening of the French people and the beginning of its vengeance against the oppressors of nations. Nations judged in the same way as cabinets. But for our friends and enemies it was soon obvious that France had fallen into the hands of cowardly merchants who asked only to traffic in its independence and to sell its glory and liberty at the best price possible. While the kings awaited our declaration of war they received begging letters in which the French government implored pardon for its errors. The new master excused himself for having participated against his will in the revolt. He protested his innocence and his hatred for the revolution that he promised to tame, to punish, to wipe out if his good friends the kings promised him their protection, a small place in the Holy Alliance whose faithful servant he would become.

The foreign cabinets understood that the people weren’t complicit in this treason and that it wouldn’t delay in rendering justice. Their decision was taken: exterminate the insurrections that had broken out in Europe, and when everything returns to order unite their forces against France and come strangle in Paris itself the revolution and the revolutionary agent. This plan was followed with an admirable consistency and skill. They couldn’t go too fast, because the people of July, still full of their recent triumph, would have been too alert to a too direct threat and would have forced its government’s hand. In any event, it was necessary to grant time to the middle way to stifle enthusiasm, discourage patriots and instill mistrust and discord in the nation. They also couldn’t go too slowly, for the masses could have grown tired of the servitude and poverty that weighed on it internally and for a second time smash the yoke before the foreigners were in shape.

All of these shoals were avoided. The Austrians invaded Italy. The bourgeois who govern us said “Good!” and bowed before Austria. The Russians exterminated Poland. Our government cried “Very good!” and prostrated itself before Russia. During this time the London conference amused the onlookers with its protocols aimed at assuring the independence of Belgium, for a Restoration in Belgium would have opened France’s eyes and it would have been in a position to defend its work. The kings are now taking a forward step. They don’t want an independent Belgium: it’s a Dutch restoration they want to impose on it. The three courts of the north, confronted with the massacre, refuse to ratify the famous treaty that cost the conference sixteen months of labor.

And now will the middle way respond with a declaration of war on this insolent aggression. War! Good God! The word makes the bourgeois turn pale. Listen to them! War means bankruptcy, war means the Republic! War can only be supported with the blood of the people; the bourgeoisie doesn’t involve itself in this. Their interests, their passions have to be appealed to in the name of liberty, of the fatherland’s independence. The country must be put back into their hands, which alone can save it. It would be a hundred times better to see the Russians in Paris than to unleash the passions of the multitude. At least the Russians are friends of order; they reestablished order in Warsaw... These are calculations and the language of the middle way.

The Royalists will keep themselves at the ready, and next spring the Russians, on crossing the border, will find their lodgings prepared for them as far as Paris. For you can be sure that when the time comes the bourgeoisie will not resolve to make war. Its terror will have been increased by all the fear that will be inspired in it by the anger of a people betrayed and sold out, and you’ll see the merchants brandish the white rosette and receive the enemy as a liberator, for the Cossacks frighten them less than the mob in work jackets.

156 notes

·

View notes

Photo

UNIFORM COLONEL OF CHASSEURS À CHEVAL (SHAKO, HABIT), July Monarchy,1831.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just randomly leafing through Gisquet’s memoirs when I notice a chapter description mentioning a “riot of July 14th 1831“ and I was like “ooh, what’s that? I’ve never heard of this one“ and:

“For the 14th of July, the republican party had decided on the plantation of three trees of liberty in three different points in the city streets; and all the enemies of the government seemed to be preparing for a serious clash.“

Excuse me, why did nobody tell me about this radical tree-planting riot? that apparently happened???

Somebody please tell me more about this and also there has to be fanfiction of this, right? If not, there should be.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

having a very normal one looking into canon era newspapers. here’s what I got, ordered by year of creation:

La Gazette: Established 1631. Girondist during the Revolution, Bonapartist during the Empire, Royalist during the Restoration, Legitimist during the July Monarchy.

Journal de Paris: Established 1777, originally pop culture rather than politics, Royalist during the Restoration, defunct 1840

Journal des débats: Established 1789, critical of Napoleon during the Empire, Doctrinaire during the Restoration, most read newspaper during the Restoration and July Monarchy, defunct 1840

Le Moniteur: Established 1789. Official paper of the government from 1799-1868, particularly propagandist under Napoleon, defunct 1868

La Quotidienne: Established 1790, Royalist, defunct 1848

Le Constitutionnel: Established 1815, Liberal, Bonapartist, Anti-Church, defunct 1914

La Minerve: Established 1818, Liberal, Pro-Charter, suspected of Bonpartist & Republican advocacy, seems like it was already defunct by 1820?

Le Courrier français: Established 1820, liberal, Doctrinaire, centrist, defunct 1851.

Journal asiatique: Established 1822, biannual peer-reviewed journal about Asian studies

Le Globe: Established 1824, originally Romanticist, Anti-Restoration, became Saint-Simonist (Utopian Socialism) in 1830, banned in 1832

Le Figaro: Established 1826. Satirical, Royalist but made fun of Ultra-Royalists from what I understand, Pro-July Revolution, critical of the July Monarchy, bought by Monarchists in 1832

Le Messager des Chambres: Established around 1827? by Martignac, Ultra-Royalist, defunct around 1852

Le Correspondant: Established 1829, Catholic and Royalist, ceased publishing for a decade in 1831, defunct by 1937

Le Temps: Established 1829, Liberal/Center-Left, very critical of Polignac, harassed by police, defunct 1842

Revue de Paris: Established 1829, literary magazine, defunct 1970

Le National: Established january 1830 with Talleyrand’s money, Doctrinaire, pro-Constitutional Monarchy anti-Charles X, protested the July Ordinances, banned 1851

L’Avenir: Established 1830, wanted to merge Liberal and Catholic idea, pro separation of church and state, pro freedom of education and press, pro pope, Ultramontane, Romantic, condemned by the pope and subsequently defunct in 1832

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gold brooch encasing a diamond-ringed enamel portrait of King Louis-Philippe, whose reign lasted from 1830 to 1848 (when the short-lived Orléans monarchy toppled). It can be seen this autumn and until February 2019 at the exhibition Louis-Philippe in Fontainebleau, held at that palace.

#1840s#jewellery#france#july monarchy#19th century art#orléans#louis philippe#19th century design#queued

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

During the July Monarchy of 1830-1848, Marie Antoinette's theater at the Petit Trianon was refurbished to better reflect the style of the mid-19th century as well as the style of its new patron, the queen Marie-Amélie--who was in fact the daughter of Marie Antoinette's sister, Maria Carolina. The blue tapestries and other furnishings ordered by Marie Antoinette were removed and replaced with bright and (in my opinion) garish red. Additionally, the monogram above the center stage was replaced briefly with an eagle emblem by Louis-Philippe before finally being replaced with M-A, the monogram of Marie-Amélie. The theater has since been redone to better reflect its original appearance as desired by Marie Antoinette, although Marie-Amélie's monogram is the monogram which has remained to this day.

images:(C) RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)/Gérard Blot

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Because as Bossuet could tell you, it’s just not a barricade without an omnibus (and, I would add, barrels. They’re nearly as essential as the paving stones).

The Louvre barricade, 29 July 1830

233 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Laffitte: *hands Louis-Philippe the resolution inviting him to assume the throne*

Périer: *looks out of the painting like he’s in The Office*

#Casimir Périer#Jacques Laffitte#Louis-Philippe#July Revolution#July Monarchy#He's upset for the wrong reasons but still#This painting is hilarious#Laffitte is so excited about constitutional monarchy and their wonderful new king!#Périer... is not

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

EIGHTEEN-THIRTIES FASHION CHANGES IN REAL TIME: Louis Philippe tries to outrun the Pear look, with mixed results.

#Eighteen-Thirties Thursday#1830s#july monarchy#honoré daumier#caricature#hairstyles#romantic era#he has seen the mean drawings you can tell he's upset#la poire

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cooper. Lafayette. Soult

Three names I never imagined to put together ...

As usual I find all the things I’ve never looked for – in this case, a description by James Fenimore Cooper (of all people) of a brief conversation that he witnessed before an audience with king Louis Philippe that he had during his stay in Paris in February 1832, a conversation between - marshal Soult and general Lafayette. Of all people. (Quoted after J. F .Cooper, »A Residence in France«).

We found the inner court crowded, but following our leader [Lafayette, of course], his presence cleared the way for us, until he got up quite near to the doors, where some of the most distinguished men of France were collected. I saw many in the throng whom I knew, and the first minute or two were passed in nods of recognition. My attention was, however, soon attracted to a dialogue between Marshal Soult and Lafayette, that was carried on with the most perfect bonhomie and simplicity. I did not hear the commencement, but found they were speaking of their legs, which both seemed to think the worse for wear. »But you have been wounded in the leg, monsieur?« observed Lafayette. »This limb was a little mal traité at Genoa«, returned the marshal, looking down at a leg that had a very game look: »but you, General, you too, were hurt in America?« - »Oh, that was nothing; it happened more than fifty years ago, and then it was in a good cause – it was the fall and the fracture that made me limp.« Just at this moment, the great doors flew open, and this quasi republican court standing arrayed before us, the two old soldiers limped forward.

Which must have been a sight to behold. It’s also just what I love – worlds colliding. Because I hardly can imagine greater political opposites than those two. But as »old soldiers« they apparently still had enough in common to have a civil if unremarkable chat. (As for old: Lafayette would turn 75 that year, while Soult was a couple of weeks shy of his 63rd birthday.)

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cartoon by Honoré Daumier for La Caricature, 23 February 1832. Lafayette is weighed down by Louis-Philippe (depicted as a giant pear). Behind him on the wall General Lafayette can be seen supporting Louis-Philippe on the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, with a tricolour flag - the events that took place during the Trois Glorieuses that led to the July Monarchy (also referenced in the paper in Lafayette’s hand - the Hôtel de Ville program). Lafayette’s response is indicated by the title - ‘Le Cauchemar’ (The Nightmare...which rather invokes Fuseli’s work of the same title!). This change in mood towards the July Monarchy, as expressed here with Lafayette’s disenchantment with the regime he helped bring to power, would reach a head during the cholera epidemic that was already fermenting. In June 1832 the barricades would rise again in Paris (as depicted in Les Misérables)

#marquis de lafayette#Gilbert du Motier Marquis de Lafayette#louis-philippe#july monarchy#les miserables

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il est donc vrai, Francais! ô Paris, quel scandale! Quoi! déjà subir un affront! Laisseras-tu voiler par une main vandale Les cicatrices de ton front? Juillet, il est donc vrai qu'on en veut á tes fastes Au sang épanché de ton coeur! Badigeonneurs maudits! Nouveaux iconoclastes! Respect au stigmate vainqueur!

-Petrus Borel, 1830

Rough translation, no attempt made to keep rhyme or meter here: (with assist from @kingedmundsroyalmurder, but all mistakes are mine)

So it’s true, France! O Paris, what scandal! What! An affront already! Will you let a vandal hand veil the scars of your brow? July, so it’s true we begrudge you the luxury of the blood flowing from your heart! Rotten painters! New iconoclasts! Respect the stigmata of the victor!

(the poem is from shortly after the July Revolution; it’s a protest of the hurried covering of the bullet holes from the fighting, and more symbolically of the general July Monarchy attempts to erase the signs and memory of the actual fighting.)

#Petrus Borel#Four People and a Shoelace#July Monarchy#barricade Relevant#singing wild with anger#is my new Protest Art tag

37 notes

·

View notes