#juan de la cruz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

They can be like the sun, words. They can do for the heart what light can for a field.

— Juan de la Cruz, The Poems of St. John of the Cross (University of Chicago Press, 1979)

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. John of the Cross on the recklessness of love

But when once the flame has enkindled the soul, it is wont to conceive, together with the estimation that it already has for God, such power and energy, and such yearning for Him, when He communicates to it the heat of love, that, with great boldness, it disregards every-thing and ceases to pay respect to anything, such are the power and the inebriation of love and desire. It regards not what it does, for it would do strange and unusual things in whatever way and manner may present themselves, if thereby its soul might find Him Whom it loves.

6. It was for this reason that Mary Magdalene, though as greatly concerned for her own appearance as she was aforetime, took no heed of the multitude of men who were at the feast, whether they were of little or of great importance; neither did she consider that it was not seemly, and that it looked ill, to go and weep and shed tears among the guests, provided that, without delaying an hour or waiting for another time and season, she could reach Him for love of Whom her soul was already wounded and enkindled. And such is the inebriating power and the boldness of love, that, though she knew her Beloved to be enclosed in the sepulchre by the great sealed stone, and surrounded by soldiers who were guarding Him lest His disciples should steal Him away, she allowed none of these things to impede her, but went before daybreak with the ointments to anoint Him.

7. And finally, this inebriating power and yearning of love caused her to ask one whom she believed to be a gardener and to have stolen Him away from the sepulchre, to tell her, if he had taken Him, where he had laid Him, that she might take Him away; considering not that such a question, according to independent judgment and reason, was foolish; for it was evident that, if the other had stolen Him, he would not say so, still less would he allow Him to be taken away. It is a characteristic of the power and vehemence of love that all things seem possible to it, and it believes all men to be of the same mind as itself. For it thinks that there is naught wherein one may be employed, or which one may seek, save that which it seeks itself and that which it loves; and it believes that there is naught else to be desired, and naught wherein it may be employed, save that one thing, which is pursued by all. For this reason, when the Bride went out to seek her Beloved, through streets and squares, thinking that all others were doing the same, she begged them that, if they found Him, they would speak to Him and say that she was pining for love of Him. Such was the power of the love of this Mary that she thought that, if the gardener would tell her where he had hidden Him, she would go and take Him away, however difficult it might be made for her.

8. Of this manner, then, are the yearnings of love whereof this soul becomes conscious when it has made some progress in this spiritual purgation. For it rises up by night (that is, in this purgative darkness) according to the affections of the will. And with the yearnings and vehemence of the lioness or the she-bear going to seek her cubs when they have been taken away from her and she finds them not, does this wounded soul go forth to seek its God. For, being in darkness, it feels itself to be without Him and to be dying of love for Him. And this is that impatient love wherein the soul cannot long subsist without gaining its desire or dying.

—St. John of the Cross, Dark Night of the Soul

#St. John of the Cross#love#love theory#christian mysticism#mysticism#christianity#theology#Dark Night of the Soul#Juan de la Cruz#literature#Mary Magdalene

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

They can be like the sun, words. They can do for the heart what light can for a field. ~ Juan de la Cruz, The Poems of St. John of the Cross

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Y como quiera que cada viviente viva por su operación, como dicen los filósofos, teniendo sus operaciones en Dios, por la unión que tienen con Dios, el alma vive vida de Dios y se ha trocado su muerte en vida. Porque el entendimiento, que antes de esta unión naturalmente entendía con la fuerza y vigor de su lumbre natural, ya es movido e informado de otro principio de lumbre sobrenatural de Dios y se ha trocado divino, porque su entendimiento y el de Dios todo es uno.»

San Juan de la Cruz: «Llama de amor viva (primera redacción)», en Obras de San Juan de la Cruz, tomo IV. Tipografía de “El Monte Carmelo”, pág. 44. Burgos, 1931

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dias-de-la-ira-1

#san juan de la cruz#juan de la cruz#juan de yepes álvarez#llama de amor viva#natural#naturaleza#sobrenatural#únión mística#mística#literatura mística#mística cristiana#mística española#mística experimental#mística experimental cristiana#misticismo#dios#alma#entendimiento#cristianismo#orden de los carmelitas#místicos carmelitas#renacimiento#renacimiento español#teo gómez otero#zurbarán#pensamiento español

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

juan de la cruz -- shake your brain

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

John of the Cross The dark night of the soul

St. John of the Cross was one of the most famous mystics of Christianity. He supported Teresa of Avila's reform efforts in the Carmelite order and repeatedly came into conflict with the church superiors as a result. He passed on his mystical experiences in an extensive lyrical work.

John of the Cross was born in 1542 in the small village of Fontiveros near Ávila in Castile. His father Gonzalo de Yepes came from the Toledan nobility, but was disowned because he had married the weaver Catalina Alvarez. Johannes grew up in poor circumstances. At the age of nine, he lost his father and moved with his mother and brother Francisco to Medina del Campo near Valladolid.

Here he attended the “Colegio de los Doctrinos” and did simple jobs for the nuns of the convent of the “Santa María Magdalena” church. He initially worked as a nurse at the “Inmaculada Concepción” hospital. At the age of eighteen, he was accepted into the newly founded Jesuit College in Medina del Campo. Here he studied humanities, rhetoric and classical languages for three years. After his training, he began a one-year novitiate with the city's Carmelites. It seems that his deprived childhood and youth led him to choose the secluded path of a contemplative life. Before John turned his full attention to monastic life, he studied philosophy for three years in Salamanca, was then ordained a priest and returned to Medina del Campo. It was there that John met Teresa of Avila for the first time. The encounter had a lasting impact on his life. Teresa suggested that he join her “for the glory of God” and support her plan to reform Carmel. In Spain's “golden age”, the 16th century, the Catholic Church ruled as a matter of course - also protected by the cruel instrument of the Inquisition. The overseas conquests created enormous wealth for the already wealthy.

In the monasteries, the strict rules of the order were increasingly being abolished. Teresa of Avila sought to reform the order against this trend. She aimed to counter “secularization” with greater contemplation and seclusion of the religious. In practical terms, this meant a strictly eremitical orientation: collective solitude, inner prayer and physical work. In many monasteries, a storm of indignation broke out against the reform. The conflict is finally defused by the separation into “shod” and “unshod” Carmelites. Johannes found his home among the “unshod”. In 1568, he founded the first reformed male religious community.

From 1572 to 1577, John lived as spiritual director and confessor to the sisters of the convent of Avila. Teresa of Avila wrote her most important works during this time, John his first. His commitment to the reform of the order was soon to bring him much suffering.

“Bring me out of this death, / my God and give me life; Hold me not fast / in this so hard snare, / She as I suffer to see thee. And so comprehensive is my suffering, / that I die because I do not die.”

These lines from the “Spiritual Canticle” were written in a lightless dungeon in 1577. John of the Cross - as he now called himself - was kidnapped by conservative Carmelites and thrown into a monastery dungeon in Toledo due to the intrigue of a false accusation. Here, among other poems, he wrote the “Spiritual Song” and the famous “Dark Night” of the soul. The saint remained incarcerated for nine months - without a change of clothes, conversation or spiritual support. On the night of August 16-17, 1578, he made an adventurous escape to the convent of the Discalced Carmelites in Toledo.

“On a dark night / full of longing inflamed with love / oh happy event! I escaped unrecognized / when my house was already silent.” In addition to the horror of “horror vacui” - the horror of emptiness - John experiences the nine-month period in prison as a time of purification. In the dungeon, he experiences the presence of God in the darkness. Similar to Teresa of Avila's “seven dwellings of the inner castle”, John also sees the union with the divine divided into different stages of development. Thus, the insights of the “Dark Night” presuppose a process that John describes above all in the writing “Ascent to Mount Carmel”. “The soul must pay loving attention to God.” This “loving attentiveness” is an inward listening, because God is present in people. “The center of the soul is God.” Says St. John of the Cross. But only a few people experience this, because in everyday life people's senses, intellect and will are loud and overactive. But truly experiencing God requires silence. It requires “loving attention” that listens and looks without expectation and without a concrete idea of God.

In contrast to actively preparing oneself on the path to “Mount Carmel of God's unification”, in the next stage man experiences the work of God more passively as a dark force that temporarily hides its light and reveals itself as darkness. Those who surrender to the dark night of the soul can expect a rich reward in the union with God: “It produces in the soul an intense, tender and deep bliss that cannot be expressed with mortal tongue and surpasses all human understanding. For a soul united and transformed in God breathes in GOD and to GOD the same divine longing as God breathes to the soul. Each lives in the other and one is the other and both are one through loving transformation. I live, but not I. Christ lives in me.”

After his escape from prison and a brief period of recuperation, John of the Cross was sent to Andalusia, where he spent ten years in various monasteries. In the south of Spain, the conflict between shod and unshod Carmelites was less charged. He then returned to his native Castile, to the Carmel of Segovia, where he held the office of superior of the community. In 1591, another attack on the uncomfortable mystic: he was relieved of all responsibilities and expelled from the order. Later, plans were made to send the monk, already weakened by illness, to the order's new province of Mexico. Only his poor health thwarted this plan. “What worries me is that people are blaming someone who doesn't have any.”

At the age of 49, John retired to a solitary monastery in Jaén, where he fell seriously ill. He died on the night of December 13-14, 1591, while his confreres were saying the night prayer of Matins. It is not least Juan de la Cruz's poetic legacy, his spiritual love poetry, that makes the mystic worth reading and thinking about even in the 21st century.

youtube

#juan de la cruz#Johannes vom Kreuz#John of the Cross#Giovanni della Croce#Иоанн Креста#十字若望#十字架のヨハネ#Ristin Johannes#Jean de la Croix

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The writers of ABS-CBN's Juan De La Cruz were cooking and it's upsetting that nothing else was done with the franchise after its run ended.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT JOHN OF THE CROSS The Doctor of the Church and Mystical Doctor Who is the Patron of Contemplative Life Feast Day: December 14

"Whenever anything disagreeable or displeasing happens to you, remember Christ crucified and be silent."

John of the Cross, who is the co-founder of the reformed Carmelites (Discalced Carmelites), was born Juan de Yepes y ��lvarez in Fontiveros, Ávila, Crown of Castile (Spain), on June 24, 1542.

At the age of 21, he entered the Carmelites at Medina, taking the religious name of John of St. Matthias. He frequently asked God, that he might not pass one day of his life without suffering something. After his ordination in 1567, he was granted permission to follow the original rule of Rule of Saint Albert, which stressed strict discipline and solitude. In 1568, together with St. Teresa of Ávila (Teresa of Jesus), he opened the first monastery of the newly reformed Discalced (barefoot) Carmelites, whose members were committed to a perfect spirit of solitude, humility and mortification.

On the night of December 2, 1577, John's monastic reform fomented the anger of some old Carmelites, who accused him of rebellion and had him arrested. It was in prison that he began to compose some of his finest works, like the 'Cántico Espiritual (The Spiritual Canticle)' and 'The Living Flame of Love'.

In 'The Dark Night of the Soul (La Noche Oscura del Alma)', John wrote: 'It is impossible to reach the riches and wisdom of God, except by first entering many sufferings.'

One time, John corrected a certain Fr. Diego who used to disregard the rule. This wicked religious, rather than repent, went about over the whole province trumping up accusations against the saint. Thus, John was transferred to a remote friary at Úbeda, Kingdom of Jaén, Crown of Castile, where he died due to erysipelas (a bacterial skin infection) at the age of 49.

John of the Cross is canonized by Pope Benedict XIII on the feast of St. John the Apostle on December 27, 1726 and declared a Doctor of the Church in 1926 by Pope Pius XI after the definitive consultation of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange O.P., professor of philosophy and theology at the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum in Rome. His major shrine can be found in Segovia.

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#carmelites#discalced carmelites#john of the cross#juan de la cruz#contemplative life#doctor of the church

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Juan de la Cruz. Al natural', de Fernando Donaire

Hoy traemos a nuestro blog la noticia de una nueva obra de Fernando Donaire, ocd. Se titula Juan de la Cruz, y el subtitulo, que se toma del nombre de la colección es Al natural. Acaba de salir publicado por la editorial PPC y tiene 192 páginas. Así nos lo presenta la página web de la Editorial: Hablar de Juan de la Cruz es adentrarse en su universo poético y en el misterio de su experiencia de…

0 notes

Text

"Z wielkości i piękna stworzeń...poznaje się ich Stwórcę..."

Z wielkości i piękna stworzeń poznaje się przez podobieństwo ich Stwórcę… Jeśli ich moc i działanie wprawiły ich w podziw – winni byli z nich poznać, o ile jest potężniejszy Ten, kto je uczynił. Urzeczeni ich pięknem… winni byli poznać, o ile wspanialszy jest ich Władca, stworzył je bowiem Twórca piękności (Mdr 13, 5. 4. 3). Te przepiękne słowa z mojej ulubionej Księgi Mądrości rozpoczynają…

0 notes

Text

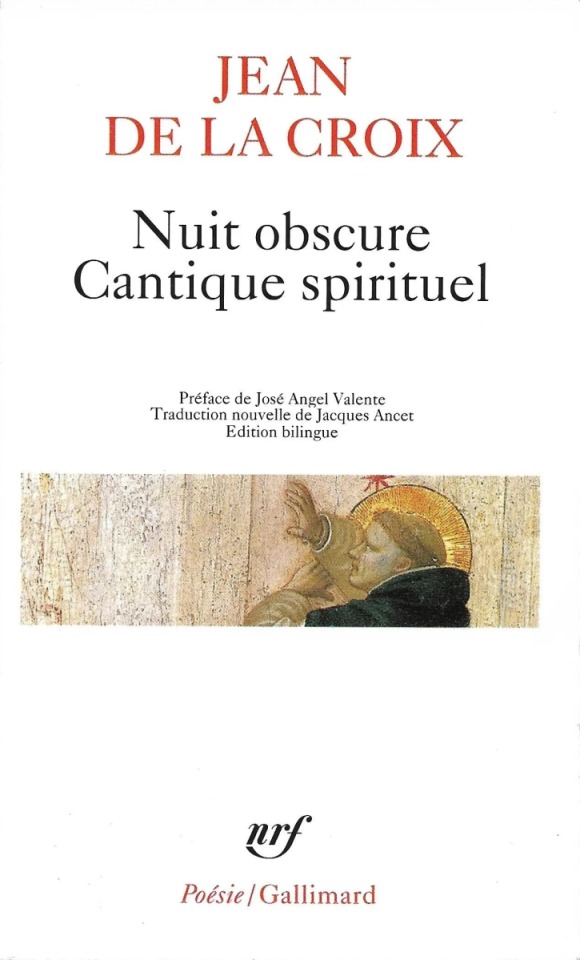

Poésie - Jean de la Croix (Juan de la Cruz), Noche oscura (Canciones del alma) [Nuit obscure (Chansons de l’âme)]

Poésie - Jean de la Croix (Juan de la Cruz), Noche oscura (Canciones del alma) [Nuit obscure (Chansons de l’âme)] #Philosophie #Poésie #JeudiCestPoésie #Poesia #Espagne #España #Nuit #Ombre #Âme

Poésie et Philosophie Poésie n° 25 Jean de la Croix, Nuit obscure Noche oscura (Canciones del alma) En una noche oscuracon ansias en amores inflamadaoh dichosa venturasalí sin ser notadaestando ya mi casa sosegada A oscuras y segurapor la secreta escala disfrazadaoh dichosa venturaa oscuras y en celadaestando ya mi casa sosegada En la noche dichosaen secreto que nadie me veíani yo miraba…

View On WordPress

#JeudiCestPoésie#Canciones del alma#Chansons de l’âme#España#Español#Espagne#espagnol#Jean de la Croix#Jeudi c’est Poésie#Juan de la Cruz#Noche oscura#Nuit obscure#Philosophie#Poésie#Poesia

1 note

·

View note

Text

San Juan De La Cruz, tr. by John A. Crow, from An Anthology of Spanish Poetry: From the Beginnings to the Present Day, Including Both Spain and Spanish America; "It was the darkest night"

[Text ID: "I climbed my secret stairway to the skies,"

#san juan de la cruz#excerpts#writings#literature#poetry#fragments#quote#words#selections#quotes#poetry collection#typography#poetry in translation

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

1608 Juan Pantoja de la Cruz - Philip III, King of Spain, as Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Tolson

(Goya Museum)

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

San Nicolás de Tolentino (detail), Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, 1601

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (Spanish, 1551-1608) Portrait of Don Diego Gomez de Sandoval Y Rojas, Count of Saldana, ca.1598 Norton Simon Museum Don Diego Gomez de Sandoval (c. 1578–1632) was the son of King Philip III’s chief minister, and attained the title of Count upon his marriage to the Condesa de Saldaña in 1604. This painting was once part of the vast collection of Philip, Duke of Orleans, Regent of France (1624–1723).

#Juan Pantoja de la Cruz#art#spanish art#spanish#spain#1500s#portrait of don diego gomez de sandoval y rojas#count#count of saldana#europe#hispanic#latin#southern europe#fine art#european art#classical art#european#oil painting#fine arts#europa#mediterranean#history#european history#historical art#espana#male portrait#male#portrait#painting

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posters for HBO's remake of Como Agua Para Chocolate.

Azul Guaita as Tita de la Garza

Ana Valeria Becerril as Rosaura de la Garza

Andrés Baida as Pedro Múzquiz

Andrea Chaparro as Gertrudis de la Garza

Ángeles Cruz as Nacha

Irene Azuela as Elena de la Garza

Mauricio García Lozano as Don Pedro Múzquiz

Louis David Horné as Juan Alejandrez

#como agua para chocolate#tita de la garza#rosaura de la garza#pedro muzquiz#gertrudis de la garza#nacha#mama elena#don pedro muzquiz#juan alejandrez#azul guaita#ana valeria becerril#andres baida#andrea chaparro#angeles cruz#irene azuela#mauricio garcia lozano#louis david horne

16 notes

·

View notes