#jean-claude rochefort

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Anti-feminist blogger Jean-Claude Rochefort, who was convicted of fomenting hatred against women, has been sentenced to 12 months in jail.

The 74-year-old had been arrested in December 2019 in connection with posts and doctored images he had posted to his blog, in which he praised Marc Lépine, who murdered 14 women at Montreal's École Polytechnique on Dec. 6, 1989 in an anti-feminist attack.

Charged in 2010 for making death threats against women on his website, Rochefort was writing under a pseudonym. Montreal police's cyber investigation team nevertheless managed to find him and charge him again in December 2019.

He was found guilty of wilfully promoting hatred against women last August.

In his ruling, Quebec Superior Court Justice Pierre Labrie rejected Rochefort's claims that his publications constituted satire, exaggeration or self-deprecation.

Noting the use of the word kill and the use of images of firearms and decapitated women in the accused's posts, the judge found that Rochefort could not have been unaware that he was deliberately promoting hatred against women."

Full article

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

#cdnpoli#canada#canadian politics#canadian news#canadian#jean-claude rochefort#misogyny#sexism#violence#violence against women#misogyny tw#sexism tw#violence tw#violence against women tw#montréal#québec#montreal#quebec

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un éléphant ça trompe énormément (1976)

Réalisation : Yves Robert

Directeur de la photographie : René Mathelin

#un elephant ça trompe enormément#Pardon Mon Affaire#yves robert#french side of tumblr#filmedit#cinephile#film#film photography#aesthetic#cinematography#screenshots#film tumblr#paris#france#jean rochefort#rené mathelin#claude brasseur#anny duperey#coupsdecoeur#alexlacquemanne

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching ''Un éléphant ça trompe énormément '' with my family, one of the main characters is gay and it's so well introduced and tackled. He's just a normal guy, having affairs like his friends. I love it. Mind you this movie came out in 1976 with 4 extremely bankable actors and was a huge hit when it came out. Representation matters, especially older representation. We were always here and we were always seen ❤️🏳️🌈

#un éléphant ça trompe énormément#french side of tumblr#upthebaguette#france#happy pride 🌈#pride month#jean rochefort#claude brasseur#victor lanoux#guy bedos

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Symphony for a Massacre' – mercenary French Noir on Cohen Media Channel

Symphony for a Massacre (France, 1963) delivers on the promise of its title. Jean Rochefort stars as Christian, a mercenary member of a gang making the leap from nightclubs and gambling rooms to narcotics, which calls for each member to kick in their share for the purchase. It was Rochefort’s first foray into crime cinema—he was a comedy star at the time—and he keeps a guarded expression but you…

#1963#Blu-ray#Claude Dauphin#Claude Sautet#Cohen Media Channel#France#Jacques Deray#Jean Rochefort#José Giovanni#Michel Auclair#Michèle Mercier#Symphony for a Massacre#VOD

0 notes

Text

French film actors of Alain Delon's generation who were more accomplished, more interesting, and on the whole, less fascist, racist, homophobic, and abusive towards everyone in their personal lives than Delon was: Maurice Ronet, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Michel Piccoli, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Yanne, Laurent Terzieff, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Jean-Claude Brialy, Sami Frey, Charles Denner, Michel Serrault, Gérard Blain, Philippe Noiret, Jean Rochefort, Jean-Pierre Marielle, Michel Lonsdale, Bruno Cremer…

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valentine Merlet, Jacqueline Bisset, Virginie Ledoyen, and Jean-Pierre Cassel in La Cérémonie (Claude Chabrol, 1995)

Cast: Isabelle Huppert, Sandrine Bonnaire, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Jacqueline Bisset, Virginie Ledoyen, Valentine Merlet, Julien Rochefort, Dominique Frot, Jean-François Perrier. Screenplay: Claude Chabrol, Caroline Eliacheff, based on a novel by Ruth Rendell. Cinematography: Bernard Zitzerman. Production design: Daniel Mercier. Film editing: Monique Fardoulis. Music: Matthieu Chabrol.

Claude Chabrol's La Cérémonie begins with a long tracking shot through the window of a café, picking up Sophie (Sandrine Bonnaire) as she walks toward her appointment with Catherine Lelièvre (Jacqueline Bisset). Catherine is as chic as Sophie, boyishly dressed with her hair cut in too-short bangs, is drab. The Lelièvres need a housekeeper, Catherine tells her, and Sophie presents the letter of reference from her most recent employer. The interview is slightly awkward, partly because Sophie is oddly oblique in her answers. But Catherine has a large house in a remote location and she needs a housekeeper right away. When Catherine drives Sophie to the house, a young woman named Jeanne appears and hitches a ride to the village near the Lelièvres house; Jeanne (Isabelle Huppert), who is as brashly forward as Sophie is reserved, works in the village post office. At the house, Sophie meets Catherine's husband, Georges (Jean-Pierre Cassel), a rather blustery businessman; her son from a previous marriage, the teenage Gilles (Valentine Merlet); and her stepdaughter, a university student named Melinda (Virginie Ledoyen). Sophie proves to be an excellent cook and a reliable maid-of-all-work, but we soon discover that she has a secret or two. One is that she's illiterate, the result of a profound dyslexia. She doesn't drive, being unable to pass a driving test, and pretends that she needs glasses. When Georges insists on taking her to an optometrist, she ducks out of the appointment and buys a cheap pair of drugstore glasses -- though even then she is unable to give the sales clerk the exact change. Waiting for Georges, she meets Jeanne again, and the two women strike up a friendship. Jeanne, it turns out, knows another secret of Sophie's, which is that she was accused of setting fire to her house, killing her disabled father. Jeanne herself was accused of abusing her daughter, born out of wedlock, and causing her death, but both women were acquitted for lack of evidence. And so the stage is set for a story of folie à deux that Chabrol and Caroline Eliacheff adapted from a novel, A Judgment in Stone, by Ruth Rendell. Bonnaire and Huppert are extraordinary in their contrasting styles: Bonnaire passive, almost autistic in manner, Huppert bold and outgoing. The climax, in which a frenzied Jeanne releases Sophie's pent-up hostility, is shattering.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claude-Jean-Baptiste HOIN

(Dijon 1750-1817)

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG LADY HOLDING A FLOWER BASKET

H. 91 cm (36 in.), l. 72 cm (28 1⁄2 in.)

Within a gilded Louis XV style frame: H. 122 cm (48 in.), l. 99,5 cm (39 in.)

Provenance:

Comte de Rochefort, Paris c. 1963

Exhibition:

- Claude Hoin, peintre de Monsieur, Paris, galerie Weil, November-December 1934, n°2

- Claude Hoin, musée de Beaux-Arts, Dijon, 1963, n°2, ill.

This portrait of a young anonymous sitter can be considered the masterpiece of Claude-Jean-

Baptiste Hoin, a well-known artist during his lifetime, today unjustly forgotten. It may be

dated from his Parisian career around 1780.

Hoin was born in Dijon, Burgundy, on June 25th 1750, where his father was an important and

renowned doctor. He entered in 1768 the workshop of the architect Claude-François Devosge

in Dijon. In 1772 he moved to Paris and was trained by his fellow Burgundian artist Jean-

Baptiste Greuze. In 1776, he was appointed member of the Académie de Dijon. Two years

later, he entered several academies Lyon, Rouen and Toulouse.

Hoin also pursued an activity as an engraver after the work of Greuze and Fragonard.

In 1779, he exhibited for the first time in Paris at the Salon de la Correspondence. The same

year, he was made professor of drawing at the Royal Military School and then, in 1782, he

became the painter of Monsieur, brother of the king, future Louis XVIII. After the

revolutionary unrest, he exhibited at the Louvre in 1801 and 1802. He was also the curator of

the Museum of Dijon, where he died on 16 July 1817.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hopefully some prisoners murder Jean-Claude Rochefort in jail

Allah forgive me, I hope so too

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Der Bürger und sein Gegenteil

von A. Klib

Michel Piccoli hat siebzig Jahre lang vor der Kamera und auf der Bühne gestanden, er hat mit Hitchcock, Luis Buñuel und fast allen bedeutenden französischen Regisseuren seiner Zeit gedreht. Mit seinem Tod endet eine Epoche des Kinos.

Man muss aufpassen, dass man von diesem Tod nicht überwältigt wird. Denn mit ihm verglüht ein ganzes Arsenal von Erinnerungen, Bildern, Momenten, Abenden im Kino, Nächten vorm Fernseher, Begegnungen, Träumen. Eine Zeit wird versiegelt, ins Museale entrückt, die eben noch greifbar war, lebendige Vergangenheit, mit uns verbunden durch die Gegenwart seines Spiels. Trauernde neigen zu Übertreibungen, aber wenn wir irgendwann, wieder mit kühlem Kopf, gefragt werden, ob es den einen großen europäischen Filmschauspieler je wirklich gegeben hat, dann wird die Antwort lauten: Ja, es gab ihn. Sein Name war Piccoli, Michel Piccoli.

Als er die Bühne des Kinos betritt, liegt Brigitte Bardot nackt vor ihm auf dem Bett und fragt ihn ihre Körperteile ab: „Liebst du meine Brüste, meine Schenkel, meinen Bauch, meine Schultern...?“, und er antwortet: „Ja, ich liebe sie.“ Es ist 1963, der Film heißt „Die Verachtung“ und ist von Jean-Luc Godard, und Piccoli spielt, als hätte er nie etwas anderes als Hauptrollen gehabt.

Er ist der Drehbuchautor Paul, der von Camille alias Bardot für einen amerikanischen Produzenten verlassen wird, aber er ist auch das Alter Ego des Regisseurs und des Zuschauers, er ist, wie sein italienisches Pendant Marcello Mastroianni, von Anfang an alle Männer in einem Mann. Die Selbstverständlichkeit, die er ausstrahlt, kann man nicht lernen, aber sie hat dennoch mit Erfahrung und Routine zu tun, mit Selbstkontrolle, sie ist, wie jede menschliche Aura, ein Bewusstseinsakt. Eine Art, „ich“ zu sagen, heller und deutlicher als alle anderen.

Damals ist er achtunddreißig. Als Sohn einer Musikerfamilie in Paris geboren, hat er schon in vierzig Filmen und zwei Dutzend Theaterstücken mitgespielt, fast immer in kleinen Rollen: ein Offizier, ein Inspektor, ein Konsul, ein Cowboy, ein Kommunist. Die eine Ausnahme ist der Priester, Pater Lizardi, den er 1956 in Buñuels „Der Tod in diesem Garten“ spielt: eine zweideutige Figur, zerrissen zwischen Entsagung und Befreiungstheolog ie, ein erster Vorschein des Ambivalenzzauberers Piccoli. Mit Buñuel wird er noch fünf weitere Filme drehen, immer in Rollen, die zwischen dem Bürgerlichen und dem Abgründigen changieren: In „Belle de jour“ ist er der Hausfreund, der Catherine Deneuve in das Luxusbordell einführt, in dem sie ihr Unbewusstes ausleben kann, in „Die Milchstraße“ dann, noch passender, der Marquis de Sade.

Lächeln mit einem Anflug von Schmerz

Nach der „Verachtung“ aber ist Piccoli ein Riese seines Berufs. Er hat der nackten Bardot standgehalten, jetzt wird er mit Ikonen bombardiert: Jeanne Moreau (in Buñuels „Tagebuch einer Kammerzofe“), Anita Pallenberg (in Marco Ferreris „Dillinger ist tot“), Karin Dor und Claude Jade (in Hitchcocks „Topas“), Françoise Dorléac und abermals Catherine Deneuve (in Jacques Demys „Mädchen von Rochefort“). Aber sie alle sind nur Übergänge, Brücken auf dem Weg zu der Begegnung, die sich tiefer als jede andere in seine Karriere einschreiben wird, der Begegnung mit Romy Schneider.

Als Claude Sautet die beiden für „Die Dinge des Lebens“ zusammenbringt, ist Achtundsechzig gerade vorbei, die Universitäten brodeln noch, Godard dreht jetzt für die Weltrevolution. Aber Sautet erzählt, als gäbe es das alles nicht, von einem Mann zwischen zwei Frauen, der Geliebten (Romy) und der Ehefrau (Lea Massari). Das Leben ist zum Fürchten leicht in diesem Film, nur dass es, als er einsetzt, gerade endet, denn der Mann liegt nach einem Autounfall sterbend im Gras, und die Momente des Glücks ziehen wie Sternschnuppen vor seinem Auge vorbei. Er lächelt – so, wie es nur Piccoli konnte: mit einem Anflug von Schmerz, in dem der Genuss des Daseins ebenso aufgehoben ist wie das Wissen um seine Flüchtigkeit. Der Brief, mit dem er der Geliebten Lebewohl sagen wollte, steckt in seiner Jackentasche. Sie wird ihn nie bekommen.

Seine Ruppigkeit war eine Art des Trauerns

In jenen Jahren war Michel Piccoli mit der Sängerin Juliette Gréco verheiratet, aber auf der Leinwand war Romy Schneider seine Frau. In „Das Mädchen und der Kommissar“ ist sie die Prostituierte und er der Flic, der mit ihrer Hilfe eine Gangsterbande fangen will, aber als sie miteinander allein sind, kehren sich die Rollen um, und er hat Mühe, die Fassung zu wahren. „Magie“ ist ein hilfloses Wort für das, was in solchen Szenen im Kino passiert, eher müsste man von Sinfonik reden, von einem Gleichklang, der über die Addition von Instinkt und Können hinausgeht. Sechs Filme hat Piccoli bis zu ihrem Tod mit Romy gedreht, und wenn man sieht, wie er in Jacques Rivettes Maler-Modell-Drama „Die schöne Querulantin“ mit Emmanuelle Béart umspringt, kann man auf den Gedanken kommen, dass seine kühle Ruppigkeit auch eine Art des Trauerns ist.

Was Sautet 1970 nicht zeigen wollte, hat Louis Malle zwanzig Jahre später in „Eine Komödie im Mai“ erzählt, und wieder steht Michel Piccoli im Mittelpunkt. Er ist das alt gewordene Kind Milou, das in einem Landhaus die Wirren der Zeitgeschichte verschlafen hat, aber als dann wirklich die Revolution ausbricht (oder das, was die Bourgeoisie dafür hält), behält er als Einziger der vielköpfigen Familie die Nerven. Diese Bonhomie ist die andere Seite des Shakespeare- und Thomas-Bernhard-Schauspielers und Gelegenheits-Anarchisten Piccoli: Wenn er wollte, konnte er sich in eine Inkarnation jenes französischen Bürgertums verwandeln, das seine Außenseiterfiguren wie der Anstreicher aus „Themroc“ oder der Serienmörder Sarret aus „Trio infernal“ am tiefsten verachteten.

Er stand immer auf beiden Seiten des Grabens, der die Arrivierten von den Nonkonformisten trennt, das Establishment von der Avantgarde. Eben deshalb konnte er das Kino als Ganzes verkörpern, die breite Skala einer Kunst, die von den Skurrilitäten eines Marco Ferreri oder Michel Deville bis zu den klassischen Filmen von Chabrol, Sautet und Malle reicht.

Michel Piccoli, der, wie jetzt bekannt wurde, letzte Woche in Saint-Philbert-sur-Risle gestorben ist, wurde vierundneunzig Jahre alt. Die Erfahrungen, die sich in einem so langen Leben verdichten, kann das Kino nicht aufbewahren, es kann nur einen Abglanz davon wiedergeben, einen Widerschein, der sich in Gesten und Worten ausdrückt und in dem, was man, aus Mangel an besseren Begriffen, Präsenz nennt. In seiner letzten großen Rolle, in Nanni Morettis „Habemus Papam“, hat Piccoli einen Papst gespielt, der an seinem Glauben irre wird und den Vatikan verlässt, um ihn wiederzufinden. Wir aber haben immer an Michel Piccoli geglaubt.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

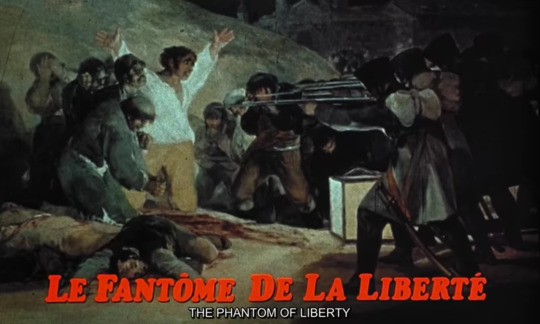

The Phantom of Liberty (1974)

#the phantom of liberty#luis bunuel#luis buñuel#adriana asti#milena vukotic#jean claude brialy#monica vitti#jean rochefort#talks

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

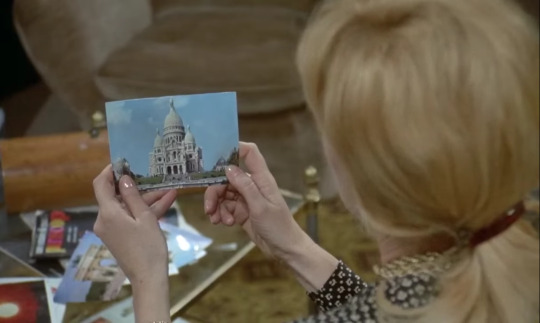

Nous irons tous au paradis (1977)

Réalisation : Yves Robert

Directeur de la photographie : René Mathelin

#nous irons tous au paradis#Pardon Mon Affaire too#yves robert#french side of tumblr#filmedit#cinephile#film#film photography#aesthetic#cinematography#screenshots#film tumblr#paris#france#jean rochefort#rené mathelin#claude brasseur#guy bedos#victor lanoux#coupsdecoeur#alexlacquemanne

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le Crabe-Tambour (Pierre Schoendoerffer, 1977).

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

une balle dans le canon (fr, deville/gérard 58)

#une balle dans le canon#a bullet in the gun barrel#michel deville#charles gérard#roger hanin#jean rochefort#pierre vaneck#mijanou bardot#colette duval#claude lecomte

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le fantôme de la liberté 1974

#le fantôme de la liberté#1974#luis bunuel#un chamboul tout#jean rochefort#jean claude brialy#Adriana Asti#paul frankeur#7/10

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Claude Brialy, Anna Karina, Jean-Paul Belmondo in A Woman Is a Woman (Jean-Luc Godard, 1961)

Cast: Jean-Claude Brialy, Anna Karina, Jean-Paul Belmondo. Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard, based on a story by Geneviève Cluny. Cinematography: Raoul Coutard. Production design: Bernard Evein. Film editing: Agnès Gullemot, Lila Herman. Music: Michel Legrand.

Orson Welles is often quoted as having said, when he saw the production facilities available to him at RKO, "This is the biggest electric train set any boy ever had!" I imagine Jean-Luc Godard saying something like that when he was told that he could make his second feature film, after the success of Breathless (1960), in color and Franscope (an anamorphic wide-screen process like Cinemascope). But of course Godard and his cinematographer, Raoul Coutard, had no intention of using the wide screen for its conventional purpose, the epic and spectacular. Instead, many of the tricks the director and the cinematographer pulled off in A Woman Is a Woman were playful ones, like filming the tiny, cramped apartment of Angela and Émile in a medium more suited to Versailles. The effect is not only slightly giddy, but it also serves to emphasize the difficulties the couple are having in their relationship. The movie is brightly inconsequential, the kind of colorful musicalized nonsense that Jacques Demy would master a few years later with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), using the same composer Godard does, Michel Legrand. The success of Breathless seems to have gone to Godard's head a bit: He enlists its star, Jean-Paul Belmondo, as the third leg of the movie's romantic triangle, and has him speak a line about not wanting to miss Breathless on TV. Belmondo also encounters Jeanne Moreau in a cameo bit, asking her how Jules and Jim is going -- Godard's fellow New Wave sensation, François Truffaut, was in the midst of filming it with Moreau. The best thing A Woman Is a Woman has going for it is Karina, who was about to become Godard's muse and for a while his wife.

2 notes

·

View notes