#it’s the same narrative structure because it’s about the same thing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm not a fan of turning the players into GMs, because I think that distracts from being players. It also requires more complex rules for adjudication, which often come at the expense of rules modelling the world and characters (unless you want something very rules-heavy like Burning Wheel). There's an advantage to having the GM be its own thing, especially as far as having a clear final adjudicator. That said, it doesn't mean the GM has to be one person. My critique is of turning the players into GMs, not with the idea of collectivizing the GM itself. It would just mean the GM collective is a different collective from the players.

The GM role is actually several tasks: managing the game socially, adjudicating disputes about the game, simulating the world, and constructing and running the narrative and mechanical conflicts. Even these can be subdivided as well. With mega-games this is required practice, but there's no reason you can't do it at a table of a half-dozen people as well. The knock-on benefit is that you can bring people back into the game as a co-GM, or bring a new person on.

The new problem becomes one of managing the interactions among these co-GMs to make sure the game runs smoothly for the players. You can fix it using all the oft decried systems for giving players the power to contest control of the game world. Meta-currencies and domains of control can work great for managing relations among the GMs while never directly touching the GM-player interactions. Because efficiency and speed require clarity, you'd need a "GM" for the GMs. (Something some "GM-less" games ironically employ for exactly that reason--they may distribute narrative and world control, but still implement an adjudicator.) It makes the most sense to make the adjudicator for the players the same as the adjudicator for the GM collective. Make adjudication their primary job.

youtube

How finely divided it gets depends on the size of the game you're running, but given how much skill, work, and/or premade materials GMs often need I think we can safely say that even for a table of 4-6 players, one GM is sometimes not enough. Currently my idea is to split the job in two: one will adjudicate and run the world, the other will construct and run all the conflicts, and anything else that challenges the players. Like when a game talks about "GM intrusion," this is the GM that would intrude. Since they already represent the villains, personal tests, battles, and other such things, it makes more sense--though I would prefer the meta-contest be between the two GMs, not between the GM and the players.

The idea originally occurred to me because of issues with running the Shadows in Wraith: The Oblivion. In the 20th Anniversary edition they suggest the idea of a player specifically just for the Shadows, but I don't think that gives them enough to do, and the way it's written it's still far to vague. Any control the Storyteller would have over the Shadowguide is purely interpersonal, since there's no mechanics for regulating most of the Shadow's behavior aside from Angst. If you made the Shadowguide instead the Oblivionguide, and mechanized that role, that's basically what I'm envisioning.

The cool thing about having that more limited secondary GM role is you can cycle people through it. One character dies, then that player replaces the old co-GM, who gets a new character. If they change the structure of the conflicts behind the scenes to keep them in the dark, it could work. This could happen over and over throughout the game, giving people a taste of GMing and maybe a better appreciation for how it is to run a game. (Forever-players are notorious for often not understand or appreciating what the GM does.) Running the villains under the oversight of the long-term GM is less intimidating I think, and having a long-term adjudicator keeps the game consistent even as you cycle co-GMs.

Exerpt from Eureka: Investigative Urban Fantasy.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once you understand Mike’s character arc, there’s no way that you can doubt about byler.

#likeeeee#Mike’s happy ending is also ending up with Will#accepting himself 😭😭😭#learning that he’s enough#of course he’s going to end up with the boy who makes him feel loved and appreciated and not like a random nerd#this boy thought he should date girls and stop playing games with Will#the same season Karen said “people say that you can’t. that you shouldn’t#the stncy/jncy love triangle being so similar to mlvn/byler#it’s the same narrative structure because it’s about the same thing#not ending in a loveless marriage like their parents who only did it because that’s what society expected from them#they have to break the cycle#both nancy and Mike couldn’t say ily because they aren’t in love#Mike is in love with a boy!!! but he thought he can’t and he shouldn’t wish to be with him the rest of his life

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

End of Empathy (time for violence)

[First] Prev <–-> Next

#poorly drawn mdzs#mdzs#wei wuxian#lan jingyi#jin ling#lan sizhui#We are back to the present! Honestly I think I'm going to try and truncate the rest of this arc.#I LOVE yi-city and I really appreciate all of the support the yi-city lovers have given me. And the patience of those who aren't.#But it's been two months. And I need to move this along </3#Anyways; I love the start of ep 3 so much. The worried concern of the juniors is so cute#but the crown jewel by far is wwx responding like a parent that's very hungover but trying so hard to be nice about it#like 'shhh shhhh guys hi I'm up now. Can you keep the volume down. Can you get me some water and my sunglasses from the glovebox.'#and of course the incredible wham line of 'Xue Yang Must Die.'#'Is YX irredeemable? I'm pro 'everyone is capable of change and deserves a chance.' So Im of the camp of 'if he had the opportunity...maybe#The issue is that this setting has no structure to provide those opportunities. You are perceived as a threat therefor you must die#XY is a very interesting parallel to the YLLZ because they both meet the same fate: outsiders determining that they need to be killed#plus both did war crimes. I know it's easy to forget the YLLZ actually did do some of the things he was accused of (most wrong)#but wwx also has blood on his hands. He also sought revenge in pretty twisted ways. Both were given opportunities to step away and refused#The difference is that we empathize with and like XXC & SL and A-Qing. The Narrative says they were wronged and that is an injustice.'

847 notes

·

View notes

Text

usually i kind of hate when a piece of art feels indulgent sorry #earthmoon BUT i hate how often i hear the take that all description in writing needs to serve the Grand Unified Purpose of the work and you can tell its dumb because imagine watching an animated film and saying they shouldnt bother to put any detail in the backgrounds because its not important to the plot or theme 🤔 like it can be one stylistic approach especially in short fiction & can description and details feel pointless and unearned sure but the idea it should only rain if ur character is sad is goofy af and the idea that every element of the world should revolve around ur character and their narrative its giving western individualism

#also using narrative voice means u can MAKE any detail thematic based on how it's observed. skill issue#in fantasy especially idgaf about like. Hard worldbuilding#but I DO gaf about the vibe. and i want to feel like the world exists outside of the character#also think it's another case like the show don't tell of emotion where the issue is probably on a deeper level than prose#like say Piranesi the story is constructed such that all the description is part of the storytelling and feels meaningful bc the story feel#meaningful. in the same way that no matter how u describe the physical sensation of sadness#it will be meaningless unless the character has a good reason to be sad#anyway I read this interesting take a while ago about the very idea of story structure being like#an individual person is changed (which fixes things) is a very western (capitalist) way of defining a story#and honestly even in folklore as much as the players are individuals they're almost always archetypical and representative of a relationshi#on a mass scale e.g class/gender/parent to child#and the turning point represents - for example - disruption of & then reassertion of a social norm#rather than like. this is a Person and they become a better or worse version of themselves which transforms the entire Story World because#orbits them and stems from them in its entirety#anyway whatever. hi

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posts I've seen in just the last week:

AO3 is one of the most visited sites in the world

It's ok if your fanfic [that you're writing for free in your spare time] is unfinished! You do you!

How very dare these WGA writers not finish writing my stories for me [that they spend full work days every day working on] just because they don't get compensated fairly for their paid labor and decided to go on strike?

Respect unions! Unionize your workplace! Respect picket lines!

Posts I have not seen ever but maybe it's just me ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ :

AO3 would not exist without the paid writers who are currently striking. You would have no stories to write fanfic of. The entire world your fic exists in was created by someone else's labor.

#tbh I don't like how you can't say anything remotely critical about fanfic without people getting up in arms like you're invalidating it#I very much agree fanfic is a valid art form#but most of it very much does rely on the work of writers who are able to develop narratives in ways that a lot fic writers don't need to#and who are practicing a craft they are trained in#and granted I don't really rove in fandom circles#but fanfic very much would not exist if not for someone else's world building and character development#and I haven't seen that acknowledged during this strike at all#people are expecting writers to finish their paid work when they can't even afford health insurance#I see so many posts about how fanfic is a valid genre and it is but that doesn't mean it's the same as professional writing#I love that people have such a passion for writing and storytelling that they do it for free in their spare time!#but that's not the same as doing it for a living and planning out a whole TV season's story arc before writing any episodes#it's not the same as writing every single character and plotline from scratch and understanding that process#it's not the same as understanding how to structure a novel and plan and implement literary motifs and themes and metaphors#which isn't to say fanfic can't do these things but how many fic writers do?#and tbh that's not the point of fic and that's fine but where's the acknowledgment that fics exist because other people DO

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

*banging pots and pans* more one piece star trek aus

#i mean fundamentally. it kind of doesnt work because of the role of 'the system' in the narrative#where in st its inherently good (if ocassionally problematic see eg. the entire second half of ds9)#in op its like. celestial dragons#but if you ignore this entire can of worms it actually has a lot of potential#captain luffy whos only reluctantly joined starfleet#number one zoro who is also chief of security#navigator nami with a start chart room like seven of nine#if we're feeling radical ferengi navigator nami#sanji is just neelix#chief engineer franky#weapons control usopp#robin as a vash type of character#helmsman jinbe#and of course doctor chopper#i mean even the plot can stay the same#its basically the same story structure#they go to an island (planet) they topple the corrupt government slash solve whatever problem they have and go to the next island (planet)#this is a very long winded way to tell st and op fans to watch the other thing#obv you arent averse to watching series with 2947354 episodes and lore that spans decades#oh and brook as a vic fontaine type of character? much to think about

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK we're done talking about spoilers now. Mad Rat Dead is fun because it's in the category of "things that, despite giving little to no indication on the cover that a specific subject is even present, handled it significantly better than a piece of media that specifically markets itself on Handling That One Subject". Despite not really marketing itself on the inevitability of death and figuring out how to live a life that you're happy to die with, it still works a damn good story on those terms, and you probably wouldn't guess just how well it works with those themes by initial presentation. Also, the soundtrack slaps.

#we speak#MRD and Spiritfarer are a lot more adjacent to each other theme-wise than you would really guess from the covers#also it stands out to us because we have another indie game that specifically marketed itself as being About Death And Death Positivity#and then fell flat on its face in the presentation and handling of those themes to the point that the whole game felt flat#MRD handling the same general themes with both more skill and more. tact? subtlety? really just sort of hammered it home#we've got stronger negativity bias than average so it Does help with memorability to be able to compare with something that sucks#MRD is very bold and up-front with its themes and it uses a relatively simple narrative structure to hammer things home#it doesn't get entirely into the complexities because that's not the sort of story it is#it's simple and snappy and confident with its premise and its writing#it knows what it's about and it doesn't see the point in beating about the bush#you don't come to MRD for an extended conversation you come to MRD for a fun story that is incredibly unapologetic about being itself#it is what it is. it wouldn't really fit in any other form. and being exactly itself is all that can really be asked of it#if you're looking for extended story and discussion and like. exploring this sort of inevitable death and closure in different forms#then spiritfarer is definitely the way to go#which is another game we will very much recommend#though there are parts of MRD that would be fun to explore they wouldn't fit with the story told#the lack of addressing them is not a flaw but merely a fact of what is being told#and exploring them extracanonically is merely giving the chance to tell a different story

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

hm. adaptations can be good without being true to the source material to ANY degree

#cat’s thoughts#there is a difference between good media and a good adaptation#take the miseducation of cameron post for example#both the book and the movie are very very good and accomplish what they set out to do#but they are /wildly/ different in noticeable ways#and honestly?? that’s fine#i know some people get really hung up about how some adaptations don’t stay true to the source material#and /all/ their critique of the newer media hinges on that and they never look at stuff with a lens other than It Has To Be The Same#honestly that kind of analysis really bothers me i think it’s weird to compare things BEFORE you look at how they can stand on their own#the percy jackson movies weren’t bad just bc they weren’t true to the books#they were bad because of extreme structural weakness in the narrative that could’ve been fixed if they committed to the changes they made#instead of half-assing them to save money

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing about the idea that "rules don't matter" in tabletop RPGs is that, while it's obviously wrong, there's only one relatively narrow sense in which it's actually a problem.

There are basically three major strands of "rules don't matter":

Groups for whom the rules don't matter because they aren't playing a game as we'd conventionally think of it – they're having a freeform RP jam, and occasionally letting a coin-flip decide what happens next for spice. The particulars of rules-based procedures aren't relevant to these groups because they're not following any particular procedures. This is perfectly fine; sure, some players who favour this approach like to go online and write bloviating thinkpieces about how all tabletop roleplayers secretly want to be doing freeform RP, and anyone who claims otherwise is simply too stupid or brainwashed to understand that they're not truly having fun, but that's not doing any harm – it's merely annoying.

Groups who have a narrow idea of what it's possible to do with tabletop RPGs. They'll look at the fact that it's possible to run – for example – a sword and sorcery dungeon crawl and a cyberpunk heist caper using the exact same set of rules, and conclude from this that it must not really matter what rules you use; of course, the real reason this works is because in terms of their formal and narrative structures, a sword and sorcery dungeon crawl and a cyberpunk heist caper are nearly identical. Again, this isn't hurting anyone – if they want to run endless reskinned dungeon crawls in a variety of milieux, that's their business, and the worst that can be said for it is that some people are a little annoying about it.

Groups who do want to play a game with a formal structure, and who recognise that rules have opinions about how the game ought to be played, but think it doesn't matter because if there's ever a disagreement between the game the rules want to produce and the game the group wants to play, the GM can fix it on the fly. This is always going to happen to some extent, because the rules and the group will never perfectly agree about how the game ought to be played, but positioning the ability to repair that disagreement regardless of its magnitude as a basic expectation of any GM is one of the reasons we have so many folks who GM for a year or two, the burn out and never touch a tabletop RPG again.

Basically, "rules don't matter because we don't use them" and "rules don't matter because tabletop RPGs are only one thing" are largely harmless, but "rules don't matter because something something Rule Zero" is demonstrably harmful, and we need to cut that shit out.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

spiderman and cops. okay. intrinsically tied since the beginning. hobie mother FUCKIN brown the anarchist. gwen's dad pointing the gun at her. being the threat— not fully letting go of the goddamn gun even after she took off the mask. he, in the end, recognizing he cannot be good to her and be a cop at the same time, choosing gwen, and her, in the argument, saying "you're a good cop", saying she understands why he can't be her father instead, saying that being a good cop is not a good thing at all. he gives up his badge and saves himself by it. the narrative saves him and saves gwen too.

miguel and the centralized spider government. okay. how the scale of it and the organization around a single person take the spider people from the heroes of their own worlds to the threat in miles'. lost in the utilitarianism. and HOBIE MOTHER FUCKIN BROWN! THE ANARCHIST! not letting miguel unilaterally decide what the greater good looks like, deciding not to act in its name, deciding to act on his own perception of goodness. every spider person in the facility is indeed a spider person, but only hobie and miles act like Spider-Man. when worse comes to worse.

friendly neighborhood spiderman. spiderman as somebody supposed to exist in the small scale, in community, defiant of the complex social structures of the world. your friend. your hero. thread the needle. defy canon. listen to your gut. be there for those who matter to you. and try and try and try and try against everything against all odds because you're SPIDER-MAN YOU'RE SPIDER-MAN it's YOU and you can DO SOMETHING ABOUT IT

#across the spiderverse#miles morales#gwen stacy#spider gwen#hobie brown#spider punk#doveposting#spiderverse

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing that I absolutely love about TFOne's writing is that it manages to avoid a lot of the heavier criticism I've seen regarding MegOp's hero/villain dynamic over the years (trust me, the mid-2010s TF discourse was crazy)

*Spoilers Below*

First of all, the narrative benefits so much from the main 4 cast members all being a part of the same exploited mining class. So many takes on MegOp have Orion being of a higher status (an archivist, a cop, etc) while Megatron is much lower down on the social latter (a miner, a gladiator, often in the context of being a slave).

I've seen many people be put off by this, because it feels as if Megs is being villianized for being rightfully angry at the system that deeply harmed and exploited him, while Orion/Optimus is praised for taking a more pacifistic stance despite him not suffering as much from or in some ways even benefiting from the system he claims to oppose. I don't find their dynamic to be as simple as that, and I do find these takes to be a bit reductive, but I do very much see where they are coming from.

I am definitely one of those people who's very frustrated with the way pacifism is hailed as the one true path of morality, and the inherent implication that taking any sort of revenge on the people who abused/exploited you makes you just as bad as them. Also, Marvel's particular brand of demonizing any form of radical political action, despite the system clearly being broken and corrupt, but being completely unwilling to offer any other alternatives to meaningfully change things for the better.

When looking at what I described above its pretty easy to see how a lot of versions of MegOp's hero/villain dynamic unfortunately fits into that trope. Bringing it back to TFOne, you can see how Op and Meg coming from the same political/social status subverts this. The existence of Elita and Bee only further illustrates that out of the 4 people of the mining class who were all deceived, exploited, and literally mutilated in the same way it is only D-16 that completely loses himself to his rage, even to the point where he loses compassion for his own companions and disregarding the safety of the other miners (when he decides to "tears everything down" and Elita exclaims he's going to "kill everyone").

What I think I love most about the characterization in TFOne is that Orion is the radical one. Not only that, but he is praised by Elita and by extension the narrative for it. He is constantly challenging authority, and is the first to have the suspicion that their society is structured in an unjust way.

Meanwhile D-16, to be frank, is kind of a bootlicker. He fully believed in the system and that Sentinal Prime, as someone with power, had the right to decided "what was best" for those who are weaker/lesser (I wish I had the specific quote from D-16 to support this, but the movie's still in theaters). It illustrate that D-16 already held certain fascistic ideals, and that he and Orion already have fundamentally opposing moral/political values, it simply hasn't been of any consequence yet. It shows that their eventual falling out was inevitable, even if they had decided to rebuild Cybertron together.

It should also be noted that D-16's feelings of anger and betrayal do not necessarily have anything to do with the unjust system itself, but that said unjust system was predicated on a lie. Hence his fixation on deception in the post-credits scene and him naming his faction the Decepticons. Meanwhile, when Orion learns the truth he's just sort of like "yeah, I always kinda knew something was up" because again, he understood on some level that their system was predicated on injustice.

Even D-16's obsession with Megatronus Prime, while initially an endearing aspect of his character, is also an indicator of the questionably large amount of value he puts on one's strength. It foreshadows the "might makes right" ideology that the decepticons follow, and is a key part of their ideological characterization across continuities.

Instead of the narrative we often see in Transformers media were Optimus is idolized by the narrative for being more moderate and Megatron is villiainized for being radical (or so people often claim), it is instead Optimus who is rewarded and praised by the narrative for being radical, and Megatron who is villainized and punished by the narrative for holding potentially fascistic values.

I do agree with some criticism I've seen that the whole thing with killing Sentinel and D-16's final turn into villainy felt a bit rushed and more than a little cliche, but I also understand it both had a limited runtime and that it is ultimately a family film meant to be accessible to children. More importantly though, I think the movie set the groundwork early on that, no matter how this final act played out, D-16 was always going to turn to darkness, and Orion would not have been able to stop him.

Its perfectly tragic, the way all MegOp should be, while also feeling really well thought out from a thematic standpoint. I love it.

#transformers#tf#tfone#transformers one#orion pax#megatron#d-16#optimus prime#maccadam#megop#megatron x optimus prime#kaysposts

949 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been running this writing experiment lately to cut out phrases like "I felt" in my fiction writing. Like I was looking at a sentence in a draft that said, "he felt as if character's eyes were pinning him in place." And then I was like, "well, does he think that or is it true? As a result of this person watching him, he's froze. It's not like a thing, it is that thing."

Oh and "almost"! I'm always going, "He felt almost relieved that it hadn't happened." Well, did he feel better that it didn't happen or didn't he? Or "somewhat", I'm always going, "she felt somewhat perturbed."

And like none of that is wrong, to be clear. I don't know if it'd improve your writing, I don't even know if it'll improve my writing, but I use this sentence structure all the time so every viewpoint is from a voice that thinks about what it thinks, hedges its statements, and offers the same ability for wry little jokes formatted in the exact same way. And I have a lot of writing like that and I think (!) that they're good, but read as a whole, I'm like, "god, they all sound the same." Like there's one melody that I write songs to, so even with different lyrics, it's almost (!) the same song. Something I've been struggling with in regards to my writing and why I've felt so blocked is how boring I found writing my usual way. I'd read something and enjoy the individual parts of it, but then I'd step back and I didn't like the whole. And I got good at this enough at seeing that I didn't like it to do it in real time as I was writing, which as you can imagine didn't improve the process of writing because now I was bored AND dejected about being bored.

There's this sentence-level structure fact that I use unconsciously. A pattern I find easy is short sentence, short sentence, short sentence, long sentence. So I write that. "He [verbed]. He [verbed]. Then he [verbed]. As he [verbed] to his [consequence], he [verbed] that [noun] was [statement of condition]." Which could work, it often does make for a nice rhythm, but it's something I reach for often because it's easier for me.

Just last sentence, I originally typed, "I find it easier for me." But if what I mean is "using this pattern is less effort than another pattern," then it's easier for me. One voice is hedging its bets and the other asserting. Either is fine! But they're different! And, again, GOD you would not believe how many words I've cut out of this paragraph as I write it. I'm so chatty. I love using twelve words when six will do. And that gives my writing a specific tone to my ear.

So if I am bored of that tone, why not try using just the six words? Why be understated? Why be afraid of stronger opinions? So right now with my fiction, I'm experimenting with cutting out as many self-reflective words as I can. Sometime you do need to draw attention to the face that this is the character's interpretation, but like you definitely don't need to do it as much as I naturally want to do it. You don't need to always go out of your way to allow the possibility that the narrative voice is wrong. During editing, I trim the weaker ones (I originally typed, "what I consider the weaker ones" Is that more accurate?). But I think them being there in the first place shifts my language which shifts my character's which shifts my plot. It's sentence structure all the way down!!

(this barely applies to my writing on here, btw. i try to do good but yknow this is a tumblr blog. i'm not trying to get a lit mag to accept it.)

Anyway blah blah (chatty!) the point is I've been trying to write in a way opposite of my interests. Something that doesn't take itself too seriously, that emphasizes EMOTION and ACTION instead of minimizing it, and that clips through scenes at a good pace. Doing this been amazingly fun. I've been having such a good time doing it. I am writing so much because I really enjoy doing it. The process of writing is so fun again.

This post is about two things. One is my new mood stabilizer and therapy day camp. The other is about the benefit of pretending to be MXTX.

#mxtx#w.#b.#the thing about writing scum villain is that you have to write a character so is SO CONFIDENTLY wrong.#sqq needs to be as sure of that he is wrong to the degree with which he is actually wrong#i've used more exclamation points in the last month than i have perhaps in my life. i might in fact have too many exclamation points#but turns out that shit's fun as hell#it's word confetti

793 notes

·

View notes

Note

So many TTRPG people, like yourself, seem to exist in a world where players don't actually enjoy the campaigns they're in, and don't actually like playing with the people they play with, and your whole approach to game mechanics seems like it's about trying to bribe these people to continue playing at a given table.

i have no idea where you get this idea from, I play a bunch of different games - including freeform text rp, fest larps, parlour larps, regular tabletop campaigns, longform play-by-post games and narrative wargames - and I have a lot of fun doing it. I wouldn't be a game designer if I didn't actually enjoy games. The thing is, if you study game design and ttrpg theory seriously, you think about the intent behind design decisions. Game design doesn't just happen by accident, the designer put a given rule in for a reason. So, you ask yourself why the designer made the game the way it did, and what they were trying to achieve.

A significant tool for game design is considering the feedback the game provides; what behaviours that ruleset rewards and what it discourages. (You can apply this analysis to other games, too, like video games). When I'm talking about a bribe, it's in that context; how does the game reward you for doing things, and what things does it reward. (For example, 'scrabble' rewards you for playing words with weird letters in them by making those letters worth more points.)

The thing is, ultimately, every game relies on a simple proposition; that if you volunterily use its rules, you will have fun. You don't need to follow the rules, and you can have fun without them, but the idea is that using the rules will let you have more fun, or a different type of fun, than if you didn't. (For example, throwing a ball around is a bit fun, but if everybody agrees to follow the rules of basketball, you get a different experience that a lot of people prefer). So, the only bribe you're making on the interpersonal, out-out-of-game level (unless something weird is going on) is "if we play this game it will be fun". When I talk about bribes and incentives, it's *inside* the game, after we've all agreed to the game's proposition of "if you use the rules, you will have fun".

Now, what counts as an incentive varies by game. Some, like Warhammer 40k, are challenge-based, and have ways to keep score of success and victory; here, things that signify overcoming the challenge are your incentives; how you get a high score, how you win, etc. Others, like most ttrpgs, are creative-based. What constitutes an incentive within the game's structure is less precisely defined. By and large, though, these incentives tend to be things like increased agency within the game fiction, space for creative expression, and experiencing and learning about more of the game fiction. (In this structure, 'being more mechanically powerful' can be thought of as a way of granting a player more agency, because their actions are more likely to succeed and result in the outcomes that they want. If the mechanical growth is lateral as well as vertical, then how to get more powerful is - itself - a venue for creative expression in what to prioritise, which is also a reward).

In the same way that you have the adage that 'restrictions breed creativity', the same goes for Fun. Limiting your scope from anything-goes freeform by voluntarily agreeing to use a set of game rules can produce similar results. Voluntarily limiting your agency in the fiction according to a set of game rules produces a friction that players of roleplaying games find enjoyable to push against. In this context, a reward structure within a game serves the useful purpose of signposting which direction you should push to get the fun kind of friction. A game which limits your options, and then gives you more options when you engage with certain behaviours, is telling you that those are the intended behaviours. Likewise, a game that limits your options even further when you do something is encouraging you not to do that. This is because game designs are not neutral and universal, they exist to create specific experiences. A game that rewards you by giving you more space for creative expression when you get in a fight - and gives you less space for creative expression when you avoid violence - is one that wants you to engage in violence, because it's designed to be a game where you have fun by fighting. This isn't bribing the players to sit down at the table and play the game; that has already happened outside the context of the game. They have already agreed to the game's offer of 'if you use these rules, you will have fun'. Rather, this bribing is within the game-space, the games mechanics encouraging the players to engage with it as intended, in the way that will be most fun. IE: these incentive structures are a tool the game uses to achieve the promise it makes; they guide the players towards the fun that they volunteered to have. Hope that makes sense. * * * Now, your initial ask is a weird take that's entirely unrelated to anything I've posted, and - particularly from an anon account- oddly antagonistic. I don't know if you're genuinely confused about game design, or arguing in bad faith. Either way, this probably doesn't merit the small essay I've produced, but have one anyway, it's always fun to clarify my ideas in written form.

907 notes

·

View notes

Text

SHIGARAKI VS. YUBEL: HOW TO SAVE YOUR VILLAIN

The failure of Deku to save Shigaraki isn’t just a tragic conclusion for Shigaraki’s arc, it’s also My Hero Academia failing as a story. When I say the story failed, I mean the story has failed to answer any of the questions it asked its audience. It’s themes, character arcs, everything that communicates the meaning of the story to the audience is no longer clear.

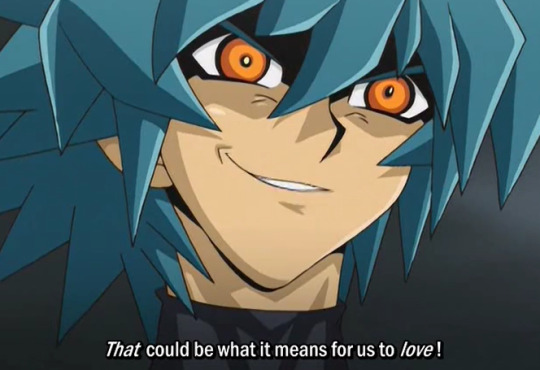

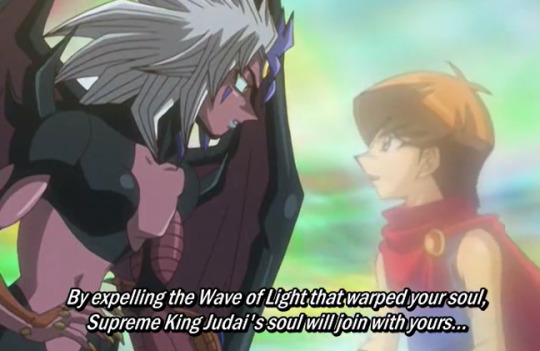

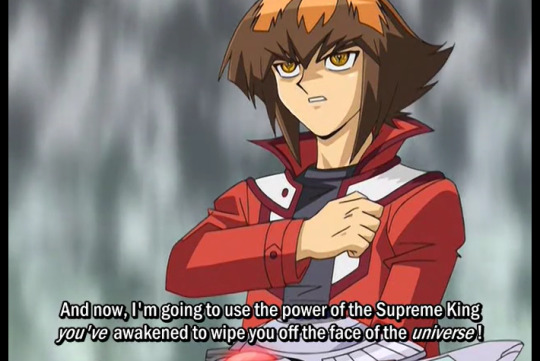

Saving Shigaraki was the central goal of not only the story itself, but the main character Deku. By failing in its goal you can’t call this a good ending. In order to illustrate why this goal of saving the villain is so important to both Deku’s character and the central idea of MHA, I’m going to provide a positive example in Yu-Gi-Oh GX were the main character Judai successfully saves their villain. One of these stories fails, and the other succeeds. I will illustrate why under the cut.

BROKEN THEMES = BROKEN STORY

When artists draw they have to consider things like perspective, anatomy, shading, light, coloring. Drawing has rules, and it’s hard to produce good art without knowing these rules beforehand. If I draw something that has bad anatomy, you can criticize me for that.

Writing has rules, just like drawing. The rules of storytelling are important because writing is an act of communication. You can write whatever you want, just like how you can draw whatever you want, but if you break the rules the audience won’t understand what you are trying to communicate.

When I refer to MHA as a broken story, I am referring to the fact that it has broken the rules of storytelling. As this youtuber explains.

“I guess we should first define what broke and broken even means in this context. Has the story turned into an unintelligible mess? Not really. Value judgements aside, the narrative is still functional and fulfills the criteria of being a story. So how can a story that still functions be broken? Maybe to you it cannot. But to me a story that is still functional isn’t enough. What I mean when I say MHA is broken is that it’s lost something crucial. A codifying style of structure, pacing and payoff that until a certain point was the core of its identity.”

I could launch into a long-winded explanation of what themes are, but for the sake of simplicity I like to define themes in terms of “Ask, and answer.” The author asks a question to the audience, and then by the end of the story provides an answer. The audience is also invited to come up with their own answer which prompts them to think about the story on a deeper level. The question both MHA and GX are asking both its main characters and the audience is “Can you save the villain?” with the additional complicated question of “Should you save the villain?” This post will detail how both stories go about answering those two questions, and more importantly why those answers matter for the story.

With Great Power… You know the rest.

My Hero Academia and Yu-Gi-Oh Gx are actually similar stories once you get past their superficial differences. MHA is a story with way better worldbuilding, compared to a society where everything revolves around the trading card game, and people go to school to be better at a trading card game.

However, if you get past that. They are both bildungsroman, stories about the main characters growing up into adults. They both have an academy setting where the goal is for the main character to graduate and enter the adult world. They are both shonen manga. GX is the sequel of Yu-Gi-Oh a manga that ran in Shonen Jump the exact same magazine as MHA. The biggest point of comparison is their main characters, who both start out as young and naive who are driven by their admiration of heroes. Deku is a fan of All Might who wants to become a hero despite not having a quirk, because he loves All might who saves everyone with a smile. Judai’s entire deck archetype revolves around “Elemental Heroes’ and later “Neo-Spacians” who are all based on popular sentai heroes like ultraman.

The central arc for both characters is to grow up. Growing up for both of them not only requires figuring out what kind of adult they want to be, but also what kind of hero they want to be.

Now I’m going to drastically oversimplify what a character arc is.

A character arc first starts out with the character being wrong. Being wrong is essential because if the character is right from the beginning, then there’s no point in telling the story. A character often holds the wrong idea about the world, or has some sort of flaw that hinders their growth. The narrative then needs to challenge them on that flaw. It usually sets up some kind of goal or win condition. That flaw gets in the way of a character “winning” or achieving their goal, so they need to fix that flaw first. If their ideals are wrong, then they need to think about what the right ideals are. If they’re too childish, they need to grow up. If they have unhealthy behaviors or coping mechanisms, they need to unlearn it and require better ones. Otherwise, that flaw will keep sabotaging them until the end.

I’m borrowing the word “win condition” from class1akids here because it’s an incredibly appropriate terminology. Midoriya needs to do “x” in order to win, otherwise this victory doesn’t feel earned. The “x” in this case is usually character development. As I said before, a story where the main character hasn’t changed from beginning to end feels pointless. Especially in Deku’s case, he was already a brave, strong hero who would charge right into battle and defeat the bad guys in chapter one, so him defeating Shigaraki in a fist fight doesn’t represent a change.

The story sets up not only “What does the hero need to do to win?” but also “How does the hero need to change in order to win?” A character either meets these requirements before the end of the story, or they don’t and usually this results in a negative ending.

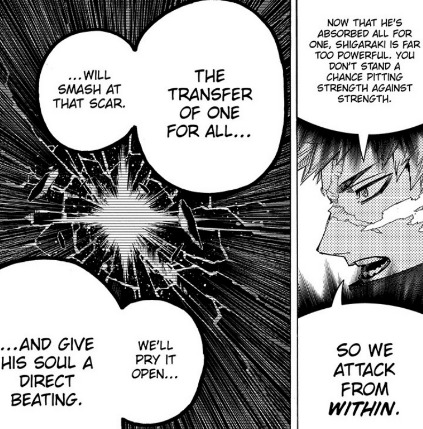

MHA in its first half quite clearly set up both the final conflict of saving the villains, and also that saving the villains is its “win conditions.” The hero shouldn't be allowed to win without first fixing this flaw.

From this panel onward the central question Deku is forced to answer shifts from “Am I strong enough to defeat ShigarakI” to “Can I save Shigaraki?” However, much earlier than that All Might goes on to basically set up the win conditions of what makes the ultimate hero as someone who “Saves by winning, and wins by saving.”

All might: You can become the ultimate heroes. Ones who save by winning, and win by saving.

Therefore the story has set it’s criteria for what kind of hero Deku needs to become. If he wins without saving, then he’s failed to become what the series has set up as the Ultimate Hero.

Shigaraki and Yubel aren’t just narrative obstacles, or boss monsters to be killed like in a video game. They are narrative challenges, which means that the character can’t grow in any way if they don’t answer the challenge presented by the characters. They are villains who actively resist being saved, to provide a challenge for two heroes who define their heroism by saving others. The challenge they pose adds a third question to the story and the main characters.

"Can I save the villain?"

"Should I save the villain?"

"If I don't save the villain, then can I really call myself a hero?"

In other words the decision they make in saving, or not saving their final antagonist defines what kind of hero they are. In Deku’s case it’s even more critical he defines what hero he wants to be because the MHA is also a generational story, and several of the kids are asked to prove how exactly this generation of heroes is going to surpass the last one. The kids growing physically stronger than the last generation isn’t a satisfactory answer, Deku getting strong enough to punch Shigaraki hard is not a satisfactory answer, because we are reading a story and not watching a boxing match.

I’m going to focus on the last two questions though for a moment. Many people who argue against saving villains like Shigaraki argue he is a mass murderer and therefore isn’t worthy of salvation. However, the act of saving Shigaraki isn’t a reflection of Shigaraki himself, but rather the kind of hero Deku wants to be. It all boils down to Spiderman. In the opening issue of Spiderman, teenage Peter Parker is bitten by a radioactive spider and suddenly gains super strength, the ability to stick to walls along with other powers. However, being a teenager he uses these powers selfishly at first. He doesn’t feel the obligation to use his powers for other people, and therefore when he sees a robbery happening right in front of him he lets the robber go. However, because he lets the robber go, the robber then attempts to hijack a car and kills his Uncle Ben in the process. If Spiderman had stopped the robber then he might have prevented that from happening. He had the power to stop the robber, but he didn’t feel responsible or obligated to save other people. As a result Uncle Ben dies. It’s not enough to have power, ti’s how you use that power that reflects who you are, therefore: “with great power comes great responsibility.”

The choice to save Shigaraki actually has little to do with whether or not Shigaraki is redeemable, but rather how Deku chooses to use his power, and what he thinks he is responsible for reflects who Deku is as a person. Deku himself also clearly outlines how he wants to use his power, that One for All is a power for saving, and not killing.

How he uses his power reflects Deku’s ideal in saving others, and therefore if he doesnt use his power to save, then he’s failed to live up to his ideals. It's not whether it's morally right to save a murderer like Shigaraki, but rather the way Deku wants to choose to use his power. It's about whether he feels the responsibility to save others.

Judai explores an incredibly similar arc to Deku. They are basically both asked what kind of responsibilities a hero is supposed to have, which is also a metaphor for growing up to handle the responsibilities of adulthood. As both characters start out with incredibly naive and childish ideas about what a hero is. Therefore realizing what a hero is responsible for is key to them growing as a character. However, Judai is different from Deku. In some ways he’s more like Bakugo. Judai is a prodigy who’s naturally good at dueling. He doesn’t duel to save others, but rather because duels are fun and he’s good at it. He’s very much like Bakugo, who admired All Might as a hero just as much as Deku did, but admired the fact that he was strong and always won rather than he saved others.

However, I would say both Deku and Judai are questioning what a hero is responsible for. They are both asking if they have the responsibility to use their power to save others. If they have to fight for other people, just because they have power. His first big challenge as a character comes from Edo Phoenix, who calls out Judai for not thinking through what it means to be a hero, and what responsibilities heroes carry. Judai duels because he thinks it’s fun. He will show up to duel to help his friends, but that’s because he’s the most powerful person in the group. Even then it’s because he finds fighting strong opponents to be enjoyable. Bakugo will beat up a villain, but for him it’s more about winning then if the action will save someone or not.

Judai is more often than not pushed into the role of being a hero, he doesn’t play the hero because he’s a particularly selfless person, and he’ll often avoid responsibility if not forced. He has power but no sense of responsibility and the narrative calls them out as a problem.

Edo: Can you even fathom that, Judai?

For Judai, he can’t understand the responsibility of being a hero. For Deku, he idealizes heroes so much he can’t understand that there are people out there the heroes have failed to save. These two callouts towards Deku and Judai are discussing similar because they’re both discussing where a hero’s responsibilities lie. Is a hero responsible for saving everyone? Is someone strong like Judai responsible for using their strength to help other people?

Judai’s arc continues into the third season where he’s not shown to just be naive but ignorant. He’s not just childish, he actively resists growing up because he doesn’t want to take on adult responsibilities.

THe same way that Deku just decides not to think about whether or not All Might failed to save people in the panels above. However, in Judai's case he's actively called out for his choice to remain ignorant.

Satou: Now, which one is at fault? Judai: Isn’t it the guy who saw it, but didn’t pick it up. Satou: Not quite. If one is aware of the trash that fell, it may be picked up someday. But there is no possibility fo the unaware one ever picking it up. Judai-kun you are the foolish one unaware of the trash that has fallen. Judai: Are you calling me out for how I am? Satou: Your behavior towards me was atrocious. The worst was attending class only for credit, even if you were there you only slept. Judai: Yeah, I know. I was all bad, but it wasn’t that big a- Satou: It is important. You see, one by one, the students inspired by your attitude were losing their motivation. Now if you were a mediocre duelist, then this would not be an issue. Satou: However, you are the same hero who defeated the three mythic demons. Every single student in the academy admires you. You should have been a model for this academy. Judai: Me, a role model? Are you kidding? I just do whatever I feel like doing. Satou: Great power comes with great responsibility. Yet, as you remain unaware of that, you’ve spread your lethargy and self-indulgence.

seems like a minor issue, but look how Judai responds to the accusations. “I just do whatever I feel like doing.” Satou is arguing that Judai should pay attention to the influence he has on others because of his power, because how he chooses to use that power affects others. However, Judai chooses to actively not look at the consequences of his actions because he doesn’t want to take on that level of responsibility, and therefore he’s looking away from the trash.

While it seems like it doesn’t matter in Satou’s specific example, not thinking of the consequences, or how you use your power can have unexpected consequences. Spiderman doesn’t feel like it’s his responsibility to stop a bank robber, and that bank robber shoots his uncle. You could still argue it’s not Spiderman’s responsibility to stop every crime in the world, and I guess no one owes anyone anything from that point of view - but Spiderman failing to act responsibility had the consequence of directly hurting someone else.

Spiderman has to live with that consequence because it was his own Uncle that was hurt. This is where we really reach the duality of Judai.

In GX, Judai is, symbolically speaking, The Fool of the Tarot Deck, the Novice Alchemist — a person brimming with infinite potential, yet one who is also supremely ignorant, who walks forward with his eyes closed and often unknowingly causes harm in his great ignorance. In this, he is very much the embodiment of the faults we most commonly associate with teenagers — selfishness, recklessness, shallowness, a lack of dedication or empathy when it’s most needed. Like most people, he has good traits that work to balance out some of the above, but his narrative path through GX ends up being that of the flawed hero undone by his faults — and then that of the atoner, the repentant sinner. In his case, the mistakes of his teenage years are the catalyst for his growth from a boy into a man burdened with duty and purpose. Judai is someone with infinite potential, with great power, but also ignorant on how he should use that power, and that makes him an incredibly flawed hero who needs to learn how that power should be used.

Deku similarly exists in a society where heroes deliberately turn a blind eye to the suffering of a certain type of victim. Shigaraki’s speech heavily resmebles Satou’s speech about garbage on the side of the road.

Shigarali: "For generations you pretended not to see those you coudln't protect and swept their pain under the rug. It's tainted everything you've built."

Deku shares Judai’s ignorance, because he’s not only a part of a system that doesn’t even see trash on the side of the road, but he also worships heroes so much that he’s incapable of criticizing them. If Deku saw the flaws of heroes, but at first didn’t have the courage to speak out, but eventually gained the courage that would be one thing. However, if he doesn’t see the flaws of heroes, then the problem will never be fixed.

There are also consequences for both Judai and Deku failing to use their powers responsibly. These consequences take the form of the villains who came about because of all of society’s ignorance to the suffering of victims (Shigaraki) and because of the main character’s ignorance to their suffering (Yubel). Shigaraki and Yubel are also explicitly victims that the heroes failed to save, turned into villains who are active threats to the heroes.

Should I save the villain?

The answer is yes, because the decision to save is reflective of the kind of hero each character wants to be. Each story clearly sets up that Deku and Judai aren’t punisher style heroes who shoot their villains, they are being set up as heroes who save. Deku needs to “save by winning.” As for Judai, a big deal is made of Judai’s admiration for another character Johan who represents a more idealistic kind of hero. Johan unlike Judai is someone who duels with a purpose, something Judai outright says he admires because he’s empty in comparison.

Judai: Johan what have you been dueling for? See, it’s about fun for me… Well, for the surprise and happiness too. I guess I do do it for the fun. Sorry, I guess I put you on the spot by asking out of nowhere. Johan: What’s this about Judai? Judai: It’s nothing. Johan: I suppose there is one goal I have. Johan: Even if someone doesn’t have the power to see spirits, they can still form a bond with a spirit. That’s why I do it for people like him. [...] Johan: I'll fight for everyone who believes in me, and I'll do it with my Duel Monsters. Judai: I'm jealous you've got feelings like those in you.

Becoming a hero who uses their power to help others isn’t just a goal the story sets for Judai, it’s a goal that Judai sets for himself because of his admiration for Johan. Johan represents the idealistic hero Judai wants to be, but is also held back from because of his personality flaws. Johan represents the kind of heroic ideal that Deku is aspiring to be.

Johan’s ultimate goal isn’t punishing the wicked, but to use his power to save others.

Johan: Judai, it was my dream to save everyone through my dueling!

The story sets up the idea that it’s not enough for Judai to simply be strong, he’s also challenged to become a savior who uses his power to help others like Johan. Deku needs to “save by winning” and Judai needs to “Save everyone through his dueling.” However, Johan also adds another condition to what saving means. His idea of saving isn’t to defeat a villain, but rather his dream is to help connect spirits and humans together, even if there are humans who can’t see spirits. Johan doesn’t save people with the power of physical force, but rather the power of human connection.

Should I save the villain?

Here the answer is "Yes", because wants to become more like Johan someone who uses their power to help others not just for themselves. Then we reach the third question

If I don't save the villain, can I really call myself a hero?

It once again comes to power and responsibility. Heroes have great power, and they are responsible in how they use that power, if they use it irresponsibly then there are consequences. Shigaraki wants to destroy hero society, because the heroes irresponsibly use their power to turn a blind eye to everyone’s suffering.

People suffer when heroes fail to live up to their responsibilities. The entire conflict of season 3 is created by Judai failing to save Yubel. If Judai had helped Yubel when they most needed it, instead of abandoning them, then Yubel would never have been twisted by the light of destruction, would never have attempted to teleport the school to another dimension, would never have attacked all of JUdai’s friends.

These consequences matter. Deku can turn his eyes away from Shigaraki’s suffering, but let’s say a hero failed to stop a robbery, or rather he didn’t even try, and because of that his mom was shot and died in the street. Would Deku consider the man who failed to stop a bank robbery a hero? When Spiderman let a bank robber go instead of trying to stop him, was he being a hero in that moment? Both the stories and the characters themselves have defined heroes as people who use their powers to save others, therefore if Judai and Yubel fail to save their villains then they can’t be called heroes by the story’s own definition. Now let’s finally return to the question of "Can I save the villain?"

Was there ever someone you couldn’t save?

m going to start with Yu-Gi-Oh Gx as a positive example of how to save your villain. Gx works for two reasons. One, it’s established from the start that Yubel isn’t beyond salvation, and two, it makes it so Judai can’t win without saving Yubel. The conflict of the story does not end until Judai makes the decision to save Yubel. In some ways the writing is even stronger because Judai is directly responsible for the pain and suffering that Yubel went through that turned them into a villain in the first place. Yubel isn’t just a victim, they’re specifically Judai’s victim.

Yubel is a duel spirit who is also essentially Judai’s childhood friend. A duel spirit just like the kind that Johan wants to save. During their childhood Yubel got too overprotective of Judai, and started to curse his friends for making him cry or upsetting him in any way. Until everyone Judai’s age started avoiding him and Judai became all alone with only Yubel for company. Judai’s decision was to abandon Yubel at that time. He took the yubel card and shot them into space, hoping that being bathed in space rays will somehow “fix” what was wrong with them. I know that’s silly but just go with it. Judai abandoning Yubel had the unintended consequence of Yubel being subjected to the light of destruction, a corrupting light that subjected Yubel to years of pain. This pain literally takes the form of Yubel burning alive.

Yubel connected to his dreams called out for Judai every night, only for Judai’s parents to give him surgery that repressed his memories of Yubel causing him to forget them entirely. Yubel then spent the next ten years alone in space, continuously subjected to painful torture, with their cries for help being ignored.

"I was suffering even as you came to forget about me..."

Yubel is then met with the question of how can Judai treat them this way if they loved him so much? As from Yubel’s perspective, they’ve only ever tried to protect Judai, only for Judai to not only throw them away, but subject them to painful torture and ignore their cries for help. Judai effectively moves on with his life, goes to duel academy, makes friends while Yubel is left to suffer in silence all but forgotten. This is where Judai’s ignorance has serious plot consequences.

It’s not just the pain that Yubel endured that made them snap. It’s that their pain went ignored.

Yubel holds out the faint hope that Judai will answer their calls fro help until they finally burn up upon re-entry into earth’s orbit. At which point they’re left as nothing more than a single hand crawling on the ground. Yubel who cannot fathom why Judai would cause them so much pain, and then forget about them, convinces themselves that Judai must be causing them pain, BECAUSE he loves them.

But you see, I couldn't possibly forget about you in the time that I've suffered...

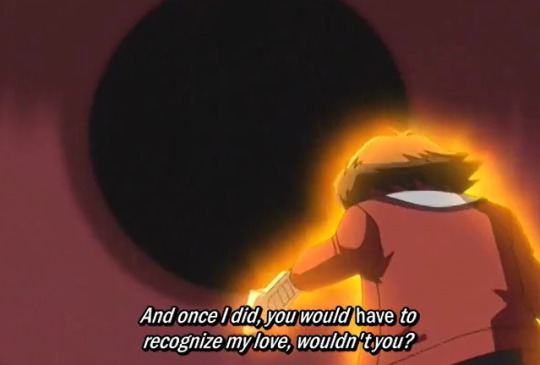

Judai is allowed to move on with his life, to make friends, to spend the next ten years doing so while Yubel is subjected to ten years of agony. When they finally escape their painful torment, they see all the friends Judai has made while they’re left alone and forgotten. However, Yubel’s goal isn’t revenge. Rather, it’s to make Judai share and recognize their pain. WHich is why I said it’s not the fact that they were made to suffer, but their suffering is ignored. Yubel’s entire philosophy revolves around the idea that sharing pain is an expression of love, and that they and Judai share their love for each other by hurting each other.

"That's why I sought to fill all those linked to you, your world, with both sadness and anguish..."

For Yubel, making all of Judai’s friends suffer and Judai themselves suffer is a way of making them and Judai equals again. They want to show “their love” for Judai, but it’s more about forcing Judai to recognize the pain he’s caused them by forcing him through the same pain. Yubel’s philosophy of sharing pain is actually a twisted form of empathy.

They’re not entirely wrong either, that even people who love each other can cause each other pain, and that if one person is suffering alone in a relationship or the suffering is one-sided then there’s something wrong with that relationship.

Yubel: I get it now… You weren’t in love, with Echo. Yubel: No.. you may have loved her just enough to clear the conditions in palace for you to control Exodia, but the you didn’t truly love each other. Yubel: You were only unfairly hurting her, while you stayed unharmed. You wouldn’t suffer. You wouldn’t suffer. You wouldn’t be in pain. Amon: What are you getting at? Yubel: I’ve been hurt! I’ve suffered! I’ve been in pain. That’s why I’m making JUdai feel the same things I did!

Yubel’s twisted theory of love, is a pretty thinly veiled cry for empathy.

They break out into tears when talking to Amon about the way they’ve hurt and suffered. They clearly state upfront that their goal is for Judai to recognize their love. One of the first things they say to Judai is a plea for Judai to remember them.

Yubel is presented as a very human character suffering through a lot of pain throughout their entire villai arc, they break down into tears multiple times, they cry out in agony, they're visibly suffering and you see their mental walls begin to break down when Judai denies them any empathy.

Yubel is actually incredibly clear and straightforward about their desire to be saved by Judai. However, Judai doesn’t lift a single finger to help Yubel the entire arc, even though they themselves admit they are directly responsible for Yubel’s suffering but they helped create who they are today.

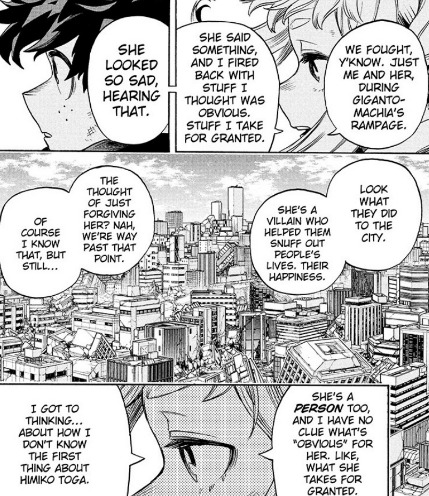

Judai plunges into a different dimension and gives up everything to save someone, but it’s Johan, not Yubel they try to save. You have Johan, the perfect friend, and perfect victim that Judai gets obsessed over and will not stop at anything to save, and then you have Yubel, the imperfect victim that is actively harming Judai and all of his friends that Judai chooses to ignore. The whole season Judai only focuses on saving the perfect victim Johan, and this is clearly shown to be a flaw. Judai doesn’t just ignore Yubel to save Johan, he also ignores every single one of his friends.

Judai only caring about saving Johan, and deliberately ignoring and abandoning the friends who came with him to help, essentially abandoning them the way he did Yubel leads to another consequence. After he abandons them they get captured, rounded up, and actually die and become human sacrifices.

Losing his friends, causes Judai to snap. Judai becomes the supreme king and decides power is all that matters; he starts killing duel spirits en masse in order to forge the super polymerization card. Which means being left alone, suffering alone, being abandoned by everyone causes Judai to snap the exact same way that Yubel did.

In fact Judai is only saved from his darkest moment, because two of his friends sacrifice their lives, trying to get through to him and appeal to his humanity. At that point Judai’s friends could have just chosen to put him down like a mad dog, to punish him for the amount of people he’s killed, but instead they try to save him because of their friendship.

I just want to save my friend. That is all.

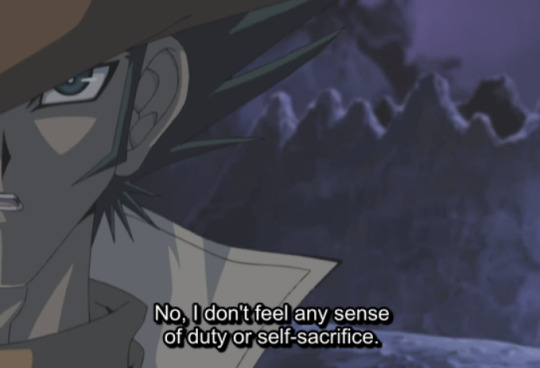

By the time Judai is facing Yubel in their final fight, Judai doesn’t have the moral highground against Yubel in any way whatsoever. They’ve both lashed out because of the pain they endured and killed countless people in the process of lashing out. The only real difference between them is that Judai is lucky. He had friends to support him at his lowest point, while Yubel didn’t. Does Judai learn from Jim’s example, and go out of their way to save Yubel the same way they were saved because Yubel is still a friend? Nope, Judai tries to kill Yubel at this point.

I made a lot of friends... And they all taught me something… real love is wide enough, large enough and deep enough to fill the universe. Your so-called love is only a conceited delusion.

Like, Judai, sweetie baby honey darling. How was Yubel supposed to make friends when they were floating in the empty void of space?

Judai hasn’t learned, they are still ignorant, and still turn a blind eye to Yubel’s suffering. After all if his love is wide enough, large enough,and deep enough to fill the universe then why don’t thy have any room in their heart whatsoever for empathizing with Yubel?

Judai making friends while Yubel was trapped in space doesn’t make Judai a better person than Yubel, it makes Judai lucky. Judai doesn’t even appreciate that luck, because he treats his friends like garbage. It’s not about whether Yubel is worthy of salvation, because Judai is a mass murderer and his friends still went to great lengths to save them anyway. It’s that Judai doesn’t want to empathize with Yubel, because they still want to remain ignorant and irresponsible. Judai wants to continue playing hero, with a very black and white definition of what a hero is. By this point Judai’s killed lots of people, but if he makes Yubel the villain in the situation, he can keep playing hero. He doesn’t have to look at himself and what he’s done, because blaming everything that happened on Yubel and then putting Yubel down like a mad dog allows Judai to absolve his own guilt. Judai practically ignores Yubel’s cries for help, even when Yubel spells it out for them.

I couldn't have lived with the heartache unless I felt that I was being loved...

At this point Yubel themselves acknowledges that their love was just a delusion. That it was a coping mechanism, because they couldn’t live with all the pain otherwise. WIthout it they would have just died, which makes Judai unmoved. The implication here is that Judai thinks yes, Yubel should have just died in that crater. It would have been easier for Yubel to die a perfect victim, then for Yubel to crawl out of that crater and go on to hurt other people. While that may be true the same can be said for Judai - it would have been better if Judai died rather than become the Supreme King. His friends could have put him down like a mad dog, you could have even called that justice - but they didn’t. Judai making no attempt to save Yubel isn’t because he thinks it’s morally wrong to save someone who’s killed as many people as Yubel has, or because he thinks he can’t forgive Yubel, it’s because Judai is taking the easy way out. Johan is a nice, easy victim to save, because he’s Judai’s perfect boyfriend, while Yubel is a complex victim that requires Judai to understand their suffering. Even the act of saving Johan isn’t about Johan himself, it’s about the fact that Judai feels guilt over Johan’s disappearance. What Judai wants isn’t really to save a friend, but to stop feeling guilty over that friend. Judai isn’t just disgusted by Yubel’s actions towards his friend, he also wants to avoid the guilt he feels over causing all of Yubel’s suffering, because it requires acknowledging the complex reality that he is both victim and perpretrator in this case, just as Yubel is both victim and perpetrator.

So how can an arc where Judai doesn’t try to save Yubel until the last possible minute, be better than an arc where Deku makes it his goal for the final act of the manga to save the crying boy in Shigaraki?

It’s because the story does not let Judai get away with his continual refusal to empathize with Yubel. Yubel’s entire character revolves around empathy, in the form of sharing pain. As a duel monster, Yubel’s effect is that they are a 0/0 attack monster who is immune to all damage, but when you attack them they deal all the damage back to you. Which means that Yubel will respond to all the pain they feel, by causing you just as much pain in return. Yubel is not a character who can be defeated in a fight, or a duel. In fact they’re the only Yu-Gi-Oh villain who never loses a duel once. The most Judai can do is duel them to a draw, and they draw three times. Yubel wins against everyone else who challenges them. In a way Yubel is like Shigaraki, the ultimate, unkillable enemy that can’t be done away with violence. Judai’s refusal to empathize with Yubel or attempt communication also makes them worse, every time Yubel is hurt they escalate. THe more Judai hurts them, the more they will hurt in return, it’s a cycle that will never be broken simply by killing Yubel, because Yubel is unkillable.

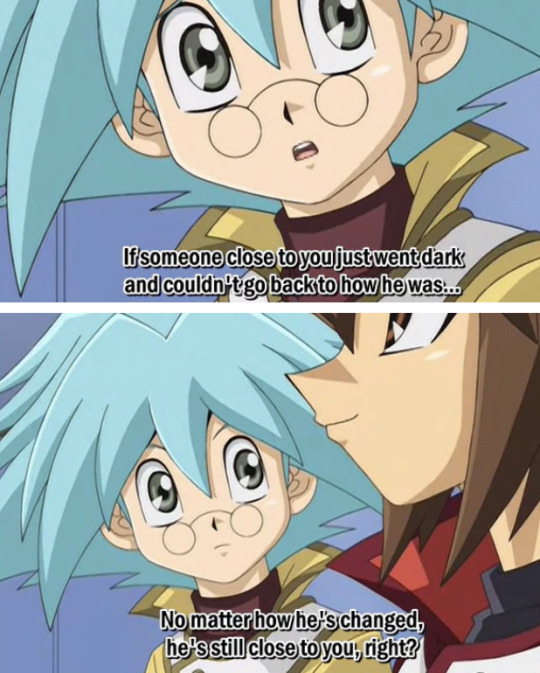

Not only that but the story has gone to great lengths to show that saving Yubel is the correct course of action. If Judai doesn’t save Yubel, he’s basically spitting on the selflessness Jim showed in saving him. In fact if he doesn’t save Yubel, Judai is contradicting his own words on what makes a good friend. Sho once asks Judai after witnessing his brother change, what he should do if a person you lov ehas changed into an entirely different person. What if they're a person you don't even recognize any more? A person you don’t even necessarily like anymore?

That's why if it were me. I'd probably just be looking after him until the very end, even if I didn't like him. I'd do it cause I think it'd prove that I care about him.

Judai doesn't even say that Sho is obligated to save his brother or morally redeem him, just that he has to keep looking at him instead of turning away or ignoring him.

Judai is being a bad friend, by his own definition. By choosing to deliberately look away from Yubel, Judai’s not living up to his advice for Sho for how you treat people you care about.

Which is why the resolution for Judai and Yubel’s arc is so important, because it’s done by Judai finally acknowledging Yubel’s pain, and promising to watch over them from now on, words that are followed by the action of physically fusing their souls together so they’ll never be alone again. Judai doesn’t just say pretty words about how they won’t ignore the crying child inside of Yubel, but instead he makes a sacrifice to save Yubel at risk to themselves to show their words are backed up by actions. Judai says Yubel will never be alone again, and then he commits.

"And even if that means I won't exist anymore... I don't care."

Judai has resolved his character arc by this action, because Judai is finally taking on responsibility and that responsibility is watching over Yubel, so the two of them can atone together. Judai even says himself this isn’t an act of sacrifice on his part, but rather him finally accepting adult responsibilities.

Judai: I wouldn't sacrifice myself for you guys. I'm just going on a journey to grow from a kid into a man.

Judai needed to save Yubel to complete his character arc and grow as a person. If Judai hadn’t saved Yubel, he would have still remained an ignorant child. By learning not to turn a blind eye to Yubel’s pain, and also smacking sacrifices and physically doing something to atone for the way they ignored Yubel up until this point they’ve not only saved Yubel they’ve also done something to address their wrongs. This also continues into the fourth season where Judai’s personal growth results in him learning what kind of hero he wants to be as in Season 4 in order to atone for the spirits that Judai slaughtered, he decides to leave his friends behind and walk the earth with Yubel helping spirits and humans get along with each other. In fact Judai’s final speech as a character isn’t even about how strong he is as a hero, but how weak he is as a person.

And I put my friends through some rough times. Form that, I figured a few things out... all I can do is believe in them.

The lesson Judai learned is because he’s weak, he needs to empathize and believe in other people the same way that his friends once believed in him when he was at his lowest point. Judai’s not the strongest hero, he’s the weakest one, but that gives him the ability to empathize with people who were lost just like he was, and guide them back from the darkness.

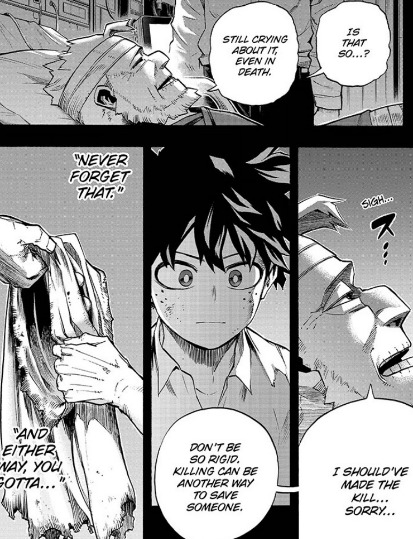

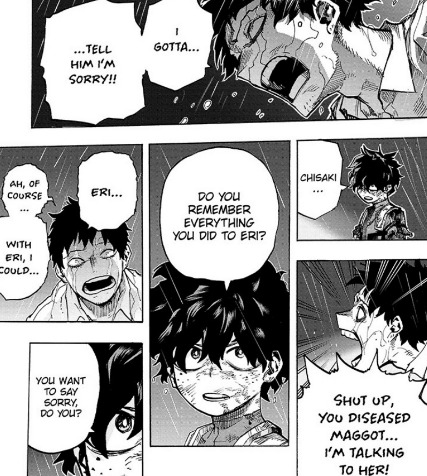

The story of how Deku became the worst hero.

I’m going to say this right now it might turn out next week that Shigaraki is just fine, and he’ll use the overhaul quirk to reconstruct his body. However, even if that happens Deku has completely failed at his goal of saving Shigaraki for the reasons I’ll illustrate below. In theory, Deku’s arc of saving Shigaraki, and therefore winning by saving should be much easier for the story to accomplish and also much less frustrating to watch. After all, Shigaraki has been around since the beginning of the manga, he’s literally the first villain that Deku faces. He’s also the first villain that Deku talks to, where he brings up the idea that there were some people All Might failed to save. There’s also many intentional parallels between the two characters, the entire manga is about their parallel journeys of becoming the next generation hero and the next generation villain. Shigaraki even directly quotes the line at one point that all he wanted was for someone in his house to tell him he could still be a hero, the same line Deku said in the first chapter was that he wanted his mom to tell him to be a hero instead of apoalogizing to him for being quirkless.

Not only is the setup for Shigaraki and Deku made obvious (Deku can redeem Shigaraki by telling him that he can still be a hero too), but Deku himself states out loud that he wants to save the crying child inside of Shigaraki.

Judai runs away from Yubel the whole time, whereas Deku is running towards Shigaraki and actively makes it his goal to understand Shigaraki and continue to see him as a human being rather than a villain. The story also makes it clear that saving Shigaraki is necessary to saving hero society as a whole. After all Yubel is just Judai’s victim. Whereas Shigaraki is the victim of all of society. He’s the crying child who was ignored. The cycle won’t be broken if heroes continue choosing to ignore people like Shigaraki, because more victims will grow up to replace him.

Shigaraki: Everything I've witnessed, this whole system you've built has always rejected me. Now I'm ready to reject it. That's why I destroy. That's why I took this power formyself? Simple enough, yeah? I don't care if you don't understand. That's what makes us heroes and villains.

Shigaraki rejects the world because the world continues to reject him. THe solution to this problem is not rejecting Shigaraki, because Shigaraki won’t go away, the system will just continue to reject people like Shigaraki. As long as heroes and villains don’t understand each other, they’ll keep being forced to fight and the conflict won’t end, because hero society is what engineers it’s own villains.

clear as day by the story itself. If the objective of saving Shigaraki is clear, then how exactly did the story fail in this objective? What went wrong? In this case it’s a failure of framing, and breaking the rules of “show don’t tell.” Stories are all about actions and consequences. When a character makes a certain action in a story, the way other characters around them, the world, and whatever consequences that action frames that action in a certain light. It provides context for how we are supposed to interpret that character in that moment.

For example, when a character does something wrong and another character directly confronts them over what they did wrong, that frames them as in the wrong. The story is criticizing the character for what they did wrong. Context is everything in a story. Stories are just ideas, so they require framing and context to communicate those ideas for the audience. Certain character attributes can be strengths or flaws depending on the context. My go to example is that if you put Othello in Hamlet, the conflict would be resolved in five seconds because Othello’s straightforward personality and determination would have him kill Hamlet’s uncle without questioning things. Whereas, Hamlet constantly questioning and second guessing himself would lead to the worst ending possible. However, if you put Hamlet in Othello, then Hamlet wouldn’t fall prey to Iago’s manipulations, because Othello doubts and questions everything so he wouldn’t believe Iago the way Othello did.

Hamlet’s contemplative and introverted nature can be a strength in one situation, and a flaw in another. Othello’s tendency to act without thinking things through can be a strength in one situation, and a flaw in another. Context matters, because context tells you how you’re supposed to interpret a certain characters actions, and therefore tells you more about that character. This is why people repeat “Show don’t tell” as the golden rule of storytelling, it’s one thing to say something about a character, it’s another to us the characters actions in the story itself to show them something about the character.

What’s even worse then breaking the rules of show don’t tell however, is telling the audience one thing, and then going onto show in the narrative something completely different. In that case the narrative becomes muddled and confusing to read. If I the narrator say “Hamlet is someone who overthinks everything” and then in the story Hamlet walks up to his uncle and kills him with no hesitation, then the narrator is straight up unreliable. It becomes impossible to tell as an author what message I’m trying to get across about these characters, because I’m telling you one thing and showing another.

This is why the writing fails in the second half of My Hero Academia because we are constantly told one thing, but then the story shows something entirely different and sometimes even contradictory to the thing we are being told.