#iphianassa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Danaë in her tower

Sometimes her prison is an underground chamber (which is probably the version y’all are familiar with) but I like the one with the tower bc it ties her to Rapunzel, ever since I’ve realized their commonalities I’ve been thinking about them lol

I like to think Danaë took up several hobbies to pass the time much like Rapunzel, but unlike Rapunzel, she actually remembers her life before her imprisonment and misses her friends, the girls she’s playing with in the fresco are her cousins Nyctaea and Iphianassa.

#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek pantheon#perseus#Danae#danaë#Argos#Acrisius#Nyctaea#Zeus#Iphianassa

390 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Names of Agamemnon’s Daughters and the Death of Iphigenia – SENTENTIAE ANTIQUAE

#agamemnon#iphigeneia#iphigenia#iphimede#iphianassa#elektra#electra#laodike#chrysothemis#klytaimnestra#clytemnestra

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was cursed to think about Clytemnestra too much (alt under cut)

#clytemnestra#epic cycle#digital art#Iphianassa#orestes#Can’t conclude who the baby is#greek mythology

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I acknowledge Iphianssa and Iphigenia as the same character. My view of later poets treating them as different individuals is they didn't realize they were the same character.

0 notes

Text

witchtober week 2 - sea witch 🌊🐚🌙

#dnd#witchtober#witchtober 2023#halloween#halloween 2023#witch#witches#october art challenge#october art 2023#dungeons and dragons#sea sorcerer#sea witch#triton#dnd triton#dnd oc#resolart#iphianassa sfyraina#iphi

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

We have to get out there and write our own reimaging people. It's the only way. Let's goooo!!!

(I personally wouldn't do a retelling or adaptation, I think the og told it best already xD) (however rip fake feminist retelling I would simply NOT butcher the og characterization)

Penelope, Ariadne, & Andromeda in mythology having:

agency

personalities

happy marriages with loving husbands

had a say in their marriages

“Feminist” Retelling Authors: look at these poor women being forced into abusive marriages by their sexist society. I will give them a voice in my retelling *proceed to ignore all their trauma and personality traits, and reduce their personalities into “girlbosses or weak victims that hate men, especially their husbands.”*

They always use the excuse “well, we don’t actually know what they felt about their husbands and situations”. YES, WE DO! Just admit you never bothered doing research or using your brain while reading the source material. If you don’t like how it was written, then just leave it be instead of trying to “fix” it.

#greek myth “retellings”#when most fic I've read are more closer to the originals in character than supposedly renowned authors#< prev tags#because they are right#also I'm a bit perplexed on Ariadne on account of the Odyssey mentioning her being killed 'on the testimony of Dionysus'#ohi Homer what does that even mean?!#but alas Homer imply that Iphigenia/Iphianassa is alive during the Iliad#as always we just pick the myth we like and ignore the others#ANYWAY#glad to see we're on one mind on 'feminist' retellings#they butcher the mythos and the feminism#a lose lose and more lose situation#mutuals

396 notes

·

View notes

Text

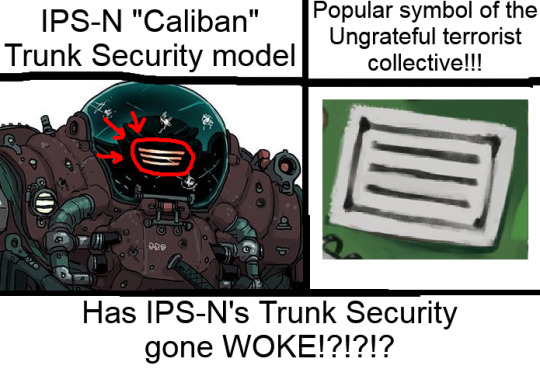

A rather concerning point made by some of our senior staff (Underbaron Iphianassa), perhaps it should be investigated?

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

the doctor is ✨IN✨

had to get one (1) artwork of her in before artfight starts and I focus on other artists' ocs. everyone look at @curiouslavellan's Iffy (Iphianassa) (The Scarred Surgeon) who is the unhinged Watson to Drakona's trainwreck Holmes and whom I love dearly

(I didn't have the brainspace to figure out a detailed marsh-wolf, but Lycaon is there as a Vague Shadow)

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Agamemnon (Person)

Agamemnon was the legendary king of Mycenae and leader of the Greek army in the Trojan War of Homer's Illiad. Agamemnon is a great warrior but also a selfish ruler who famously upset his invincible champion Achilles, a feud that prolonged the war and suffering of his men.

Agamemnon is a hero from Greek mythology but there are no historical records of a Mycenaean king of that name. The Greek city was a prosperous one in the Bronze Age, and there perhaps was a real, albeit much shorter, Greek-led attack on Troy. Both these propositions are supported by archaeological evidence. Unfortunately, though, the famous gold mask found in a shaft grave at Mycenae and widely known as the 'Mask of Agamemnon' is dated up to 400 years before any possible Agamemnon candidate that fits a chronology of the Trojan War.

Agamemnon's Family

Agamemnon was the son of Atreus, or perhaps grandson, in which case his father was Pleisthenes. His mother was Aerope, from Crete which provided a handy link between the Mycenaean civilization of the Greek Peloponnese and the earlier Minoan civilization of Bronze Age Crete. He was married to Clytemnestra with whom he had three daughters. In one version these are Chrysothemis, Laodice and Iphianassa while in other, later versions they are Chrysothemis, Electra and Iphigeneia. Agamemnon was the brother of Menelaos, king of Sparta.

Continue reading...

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like okay, I was in a really terrible mood last night. I have to look on the bright side once in a while, right? And on that note, guess who heads up the Noble Arts syllabus, and who yours truly gets to study under?

It's only Lord Castor-Eyros, Second Herald of the House of Smoke - one of my favourite authors! I have read every single one of his books cover-to-cover at least twice, and it got me through some really dark periods in my life.

They say a lot of things, like "authors don't necessarily make good teachers," and "don't meet your heroes" but I feel like neither apply to him. He's just effortlessly charming, and while he never talks down to you, I feel like he always explains even the most complex concepts in language you can just immediately grasp.

I thought Noble Arts would be the easiest for me, but I was mistaken. I'm really understanding what people mean when they say Kavaliers aren't just "good pilots," they're an ideal. A Kavalier is meant to be able to dominate the field of battle in any chassis they choose, then compose a six-stanza poem about it to ensure that when the history books are written, future generations will smile upon the necessity of the battle and the nobility of the cause.

And the College does not consider the Noble Arts a "soft subject." I'm expected to be just as conversant in Low Passacaglian history and transgenic flower hybridisation as I am in field-stripping my mech's leg assembly or the correct procedure for flanking an entrenched enemy. It's a good thing that Lord Castor is such an excellent teacher, because they are not fucking around.

Stablemaster Imani Rudilis heads up the Technical Syllabus, and I gotta hand it to the College, they really do choose only the best tutors. Mx. Rudilis is clear, concise, and you can tell that this is a subject they have genuine passion for. I understood the inner workings of a mech on a theoretical level before - now I feel like I'm starting to understand them in practice.

I'm actually finding Technical the easiest right now. Everything kind of fits together, and even really diverse topics have some relationship to what we've already learned. Like the Stablemaster says, a mech is holistic - there's no such thing as a non-essential component. Designers are constantly trying to shave down tonnages, remove points of failure, streamline the fuselage; Imani is a designer themself, and you can tell they prefer functional silhouettes over ornate frippery. I respect that.

Underbaron Iphianassa... surprised me. I mean, I've heard about her - I don't think there's a single child on Khayradin who hasn't. She's been fighting in wars for almost as long as military mechs have existed. She recognised me, too. As a member of the House of Stone, I expected she'd have the same contempt for me as the rest do - but she doesn't treat me any different to any other student. She knows my Republican leanings, and probably my opinion on her title "Hero of the Ludran Fields," but that doesn't seem to matter.

That's not to say she's going easy on me - I don't think this woman has ever been easy on anyone. Classes are... brisk. We're not just expected to pick things up quickly, we're expected to master them by the end of the day. I think Tactical is gonna be the most challenging syllabus for me. Actual combat scenarios are way different to anything I was trained on before - that was just one-on-one duels in a fast, close-quarters skirmishing frame.

I have also... met some fellow students? And by "met," I mean I've accidentally gotten them dragged into my shitty personal issues. I probably shouldn't talk about them on a public journal. They don't deserve the kind of negative attention I'd bring down on them. But they're a team with me now, whether they like it or not, Passions help all four of them.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Shadow of Perseus the relationships between women and this overall "Girls supporting girls!" idea is never here.

First let's start with Danaë!

In this book we are told that her mother died while giving birth to her, and her father initially intented to marry a girl around her age (EWW!) for a male heir, before learning about the prophecy. Sure, you could have Eurydice still being present in her life and suffering along with her after her imprisonment by her father in order to avoid that prophecy, or when he tried to kill her by throwing her into a chest and casting it into the sea. You could even have them two reuniting themselves after so many years. But because the author clearly has a hard time portraying motherhood or mother's bonds with their children in general and rather pretends to care about these women too (since they do not fit into her slay queen girlboss definition of a strong woman), Danae’s mom ended up being killed off screen.

There's also an obscure version where Danaë has a sister, but because it's a less common version of the myth even though you can find about Evarete with only one search on Wikipedia she's not here either.

Next we have Proteus' daughters and her cousins, namely Lysippe, Iphinoe, and Iphianassa. Now, we don't know too much about them, so you could do pretty much whatever you want with them, including creating a strong, wholesome friendship between them and Danaë. However, in this book Danaë herself says that they're close to each other only by blood, and that there was never a real connection between them. The fact they three collectively share one braincell in this retelling and their favorite hobby is thinking about husbands and weddings (which Danaë cannot relate to because she knows way better how oppressive marriage is and she's also not like the other girls uWu) doesn't help either.

Last but not least there's Danaë's nursemaid, who got locked along with her in some sources and helped her hide her pregnancy and then her baby before he got discovered by Acrisius, which led to said servant getting hanged as punishment. In this book though Danaë cannot trust even her handmaid named Korinna, who tells her father about her pregnancy the moment she realizes that something's odd about her.

Next we have Medusa, who, despite of being the priestess and leader of a "women's shelter" (which is a deeply anachronistic concept but whatever), her best relationship with a woman she has is between her and an OC, while her bond with her sister is portrayed as cold and distant.

Andromeda's relationship with her mother is almost non-existent, and the only other woman from her life out there is Danaë, who had very racist and xenophobic impressions on her at the beginning.

Last but not least, all of these women's lives are rotating around the exact same male character.

Somebody please tell me how is this supposed to be a feminist retelling again.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iliad Agamemnon: unheroically (?) human.

Is dunking on Agamemnon a recent trend?

No.

Post done, everybody go home xD

Nah I shall elaborate, I have to, as a chronical yapper 🗣️

In short, Homer’s portrayal of him is a bit less flattering than his average blorbo, and his very personality in the Iliad is a bit vague. Later on he got more attention, which came with more characterization and more love for the guy, but here? Keeping things Homeric.

⚔️

In fact, he mainly seem to act as foil to other characters:

- He is riled up by Achilles so the plot can happen.

- He is fooled by Zeus' dream so the plot can happen.

- He is ruthless so Menelaos appears merciful.

- He wants to give up and go home so the others can call him out and look brave and bold in comparison.

🎭

And about this last one and about his lore in the wider Epic Cycle...

- He loves LOVES his brother, he's always looking up for him. In some traditions he represented him when it came to wooing Helen, he trying to keep him from the blunt of the war. Wouldn't him wanting to go home now, his brother unavenged and his brother's wife still lost to them (I headcanon Aga and Helen were friends or friendly but that's me, please ignore that), go against it?

- He declared at the start that Briseis was dearer to him than his own wife, why is he so keen to go home where the absence of a daughter haunts the halls?

- If he's so greedy as to Achilles to throw a fit about him taking other people hard won spoils, implying he does this or has done it before (Achilles is a drama queen, that is why the if xD), wouldn't he want to stay until he's grown fat upon Troy's spoils? Like this post put well.

In fact, going Homeric as I said I would...

✒️

He has less of a tragic backstory in the Iliad - like everybody else, Odysseus' plow incident isn't mentioned, Diomedes past with the Epigoni merely brushed etc - so Atreus and Thyestes whole vendetta is absent, the power is merely mentioned to pass down from the second to the first, and Iphigenia is also not there. If we take Iphianassa being an earlier name for Iphigenia, then she's even alive in the Iliad. No tragics for him in here!

This to say. I feel Homer uses him more as a plot device as a character as fully fledged as the others despite him having a rich characterization to draw from (unless his tragic backstory is later than 8th cent bc). I feel that is why so often he's chosen to be changed into the bad guy his og self isn't, because he has less visible, striking character traits as the others. Homer didn't dunk on him, but neither elevated him like in the way he did others, leaving him vulnerable to be changed sacrificing much of his og personality. In fact, about personality!

🫴💀

Examining his personality.

At the very beginning he proposes to tell the men they should go home now, in a (techincally good) strategy to have them run to the ships only to be persuaded to come back and fight. This is good strategy because it would allow the men to express their tiredness and willingness to go home for a bit, before being brought back. Catharsis. However they turn to the ships in such a rout, they seem unstoppable. In Olympus, Hera sends Athena to half this or, as the lines says (book II 155-6), a return of the Argives, against the fates. Athena goes to her best-with-words favorite Odysseus (opposed to her other favorite, best-for-slaughtering Diomedes), who is 'not touching the ships in anxiety', who gets them under control.

This is a pattern that repeats; Agamemnon does something, others are forced to patch that up for him (the whole Achilles plot). Or he does something and it doesn't work (the dream, the embassy to Achilles).

The dream: sent from Zeus assures him victory; Nestor tell to his face that if that was someone else proposing to fight based on a dream, they would call him stupid. Later on, the same days, they lose, and Agamemnon complains that Zeus deceived him - which is 100% what happened, Zeus needed the Achaeans to lose so they would need to call upon Achilles - and yet Agamemnon loses face there.

Diomedes' aristeia (best moment) has him wounded at the very beginning of the fight, and then he goes on slaying for chapters, including his very sexy god stabbing (and wrecking Aeneas pelvis, unsexy edition), assisted by Athena.

Agamemnon similarly is wounded in his own aristeia, and he goes on fighting like the pro he is, but that doesn't span for chapter but it's almost brushed over, one paragraph. He faces no gods nor particularly important heroes of the Trojans, as even Hector is ordered by Zeus to stay away from him. This is because Agamemnon is still slaying big time (this is his aristeia, he's being as great as he can be which is shown to be a lot), but he's denied a worthy opponent who would have given him glory to face in battle.

Plus the whole Agamemnon getting called a coward many times, basically every time he proposes to leave this war and go home, especially Diomedes and Odysseus the one calling him out.

Both Achilles and Thersites, the best and the worst of the Achaean, calling his greedy and hoarder of riches at the expenses of others - and yet he wants to go home (where he is presumably safe) instead of staying here "enjoying" his rule over all the Achaeans.

He seems to like his gold and his skin (a feature, not a flaw).

The impression we get is that he's quite the average commander, the king of kings who is however not actually better than his subjects, or particularly deserving of his title. He's no Arthur to guide his knights, no Aragon to lead humbly and righteously.

Agamemnon leadership is effective enough, but not brilliant.

[Personally I think his character is a reflection of a society of the past in which he was the first among peers, so not a king in the modern sense and def not an absolute one. No idealizing of him as the Chosen One for rule; on the contrary, maybe a bit of slandering maybe, since the heroes and main characters are his 'subjects'. His role is not quite ruling but more of a judge between the gods and men (without Iphigenia, his beef with Calchas is how the seer apparently keep challenging his authority with religious insane demands) and among the bunch of high-on-ego warrior kings he's surrounded by; see how often he is represented putting himself between sward-drawing Ajax and Odysseus]

🤔

Honestly? He's a human doing his best. Ideal kings are selfless, but actual politicians do tend, like most rich people, to hoard riches. Every time he's wrong, he tries to make up for it. He's not above the others, except in responsibility.

Why does he get polarized into The Fandom Neglected Hero or the Evilest Misogynist out there? He's neither of them - and both of those views are interesting in my opinion (character exploration go brrrrr).

It's because of the Oresteia saga!

If you want people to root for Orestes, Agamemnon must be an ideal, not a struggling (to wrangle all the drama queens of the army) king who other kings constantly call a coward and whose idea turn to bite him half the times. He needs to have his heroism enhanced if the theme is to work. Here we get him to be closer to the Ideal King, to make his death hit all the harder.

If you want people to root for Clytemnestra, Agammenon must be a bad person, deserving of death, incarnating all the bad habits we usually brush over when dealing with Epic Cycle people. Slaves, war brides, women's role. He needs to be a very bad guy if the theme is to work. And he generously becomes the scapegoat we can kill to feel better about all this kind of things, which we cannot fix.

☝️

BOTH THESE INTERPRETATIONS ARE GOOD because they serve their narratives. In modern media and fics, we talk about characters, not people. They are bound to their role and every incarnation of them exists at the same time.

If I had to go with a non-Homeric characterization, I'd pick Euripides' Iphigenia in Aulis as the more Homeric, despite having all that Homer didn't: the curse of Atreus, Iphigenia being sacrificed.

Because Agamemnon once again is portrayed, essentially, as a politician. We empathize with his struggle and grief while Euripides makes his commentary on how he was very ready to pick up the mantle of command, but not as ready to pay the price it entailed.

We have enough stuff in the many og to justify Evil Aga as much as Good Aga. Homer and Euripides already used him as the caricature of the politician. He's not secretly a hero the fandom for some reason hates, he is both. He is the hero and the villain and none of these two are the "true Aga" regadless of the narrative, because they always exist in their narrative.

✨All Agamemnon Are Great Agamemnon(s)!✨

...sorry it's long, I just think a lot about this guy and the fandom. Chew on him like a dog toy and jotting down all the strange sounds it makes lmao

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

imo agamemnon does get villainized in the popular culture, but that's about making him out to be more evil than his peers in the trojan war, when his crimes in the iliad are pretty much on average — iphigenia/iphianassa is alive in the iliad, anyhow — and the conflict between agamemnon and achilles is fundamentally not moral and doesn't have a villain. but in the oresteia, where agammenon did sacrifice iphigenia, someone who enjoys clytemnestra murdering him isn't villainizing agamemnon; they just don't like him. or maybe they like clytemnestra more, for whatever reason. or maybe they just delight in the spectacle of revenge. that doesn't mean they lack reading comprehension.

#anna.txt#some of you are arguing with real people expressing blog opinions as if they personally penned the script for troy 2004#these things are not alike!#a tag for bitching

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me writing in the fic: ...then Ektor put Odysseus in a leash and ordered him to crawl at his feet 3:)

Me wiring in the notes: *adjust prof glasses* so here's a timeline of the distance between the Bronze Age Collapse, setting of the Iliad, and the written version, to prove that Achaeans and ancient Greek people, post Doric invasion, were two completely different ethnicities.

Plus I'm going to use an almost-direct transliteration of the Greek text for the names 'cause screw the Brits (sorry actual Brits, I lived in Ireland for a while and it stuck).

And to mess with everyone even more, I'll let you all know that in the text of the Iliad Iphigenia (Iphianassa) is still alive so all that sacrifice business is just a posterior angsty prequel/sequel.

Me back on the fic: ...and then Odysseus begged him to be spared, kinkily :]

"Blorbo from my shows" no. Blorbo from my BA. Blorbo from my major. Blorbo from my primary source document.

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

Merfolk Master List Part 2:

Merfolk live in oceans and are semi or fully aquatic.

Europe:

Acaste (Oceanid)

Actaea (nereid)

Admete (Oceanid)

Ægir

Aethusa (daughter of Poseidon)

Aethra (Oceanid)

Agaue/ Agave (nereid)

Ahti (Finnish)

Aigikampoi/ sea goat/ Suhurmasu

Akkruva

Amalthea (oceanid)

Amatheia (nereid)

Ambrosia (Nysiad)

Amphinome (nereid)

Amphitrite

Amphirho (oceanid)

Anthas (Alycone's)

Apseudes (Nereid)

Ardescus (Potamoi)

Arethusa (Nereid)

Argia (oceanid)

Arragouset

Arsinoe (Nysiad)

Asia (oceanid)

Asterope (Oceanid)

Autonoe (Oceanid)

Baloz (Albanian)

Bangu māte

Bára/ Dröfn (wave maiden)

Beroe (Nereid)

Beroe (Oceanid)

Bishop- fish

Blóðughadda (wave maiden)

Blue Men of Minch/ Na Fir Ghorma

Bromia (Nysiad)

Bucca/ Bucca- boo

Bunadh Beag Na Farraige

Bylgja (wave maiden)

Cabeiro (halia)

Callianassa (nereid)

Callianeira (nereid)

Calyce (Nysiad)

Calypso (Nereid)

Calypso (Oceanid)

Calypso (Odyssey)

Camarina (oceanid)

Capheira (oceanid)

Cerceis (oceanid)

Chernava (Russian)

Ceasg

Ceto (Nereid)

Ceto (Oceanid)

Charybdis

Chernava

Chesias (nymph)

Chryseis (oceanid)

Circhos

Cisseis (Nysiad)

Clio (Nereid)

Clio (Oceanid)

Clitemneste (oceanid)

Clymene (Nereid)

Clymene (Oceanid)

Clytie (Oceanid)

Cola Pesce

Coronis (Nysiad)

Coryphe (oceanid)

Cranto (Nereid)

Creneis (Nereid)

Cydippe (Nereid)

Cymatolege (Nereid)

Cymo (Nereid)

Cymodoce (Nereid)

Cymothoe (Nereid)

Daeira (oceanid)

Davy Jones

Deino (Graeae)

Deiopea (Nereid)

Dero (Nereid)

Dexamene (Nereid)

Dione (Nereid)

Dione (oceanid)

Dodone (oceanid)

Donbettyr

Donbettyr’s Daughters

Doris (Nereid)

Doris (Oceanid)

Doto (Nereid)

Dúfa (wave maiden)

Drymo (Nereid)

Dynamene (Nereid)

E Bukura e Detit (Albanian)

Eidothea (Halia)

Eione (Nereid)

Electra (Oceanid)

Enyo (Graeae)/ Enie (Etruscan)

Ephyra (Nereid)

Ephyra (Oceanid)

Erato (Nereid)

Erato (Nysiad)

Eriphia (Nysiad)

Euagoreis (oceanid)

Euagore (Nereid)

Euarne (oceanid)

Eucrante (Nereid)

Eudora (Oceanid)

Eudore (Nereid)

Eulimene (Nereid)

Eumolpe (Nereid)

Eunice (Nereid)

Eupompe (Nereid)

Eurynome (Oceanid)

Evadne (daughter of Poseidon and Pitane)

Fae/ Fada- Catalan)/ Faerie/ Faery/ Fairy/ Fee/ Fey/ Doñas de fuera/ Gente Menuda/ Sidheóg/ Slua Sí/ Túathgeinte

Fées des Houles

Finfolk (Shetland)

Galatea (Nereid)

Galaxaura (oceanid)

Galene (Nereid)/ Calaina (Etruscan)

Glauce (Nereid)

Glauconome (Nereid)

Graeae

Hafstrambr

Haliae (Greek)

Halie (Nereid)

Halimede (Nereid)

Havfolk/ Havfrue/ Havmand (Swedish)/ Havmænd (Danish) (mention Harpans kraft)

Havsrå

Hefring/ Hevring (wave maiden)

Hesione (Oceanid)

Himinglæva (wave maiden)

Hippo (Oceanid)

Hippocampus

Hipponoe (Nereid)

Hrönn (wave maiden)

Hyperenor (Alcyone's son)

Hyperes (Alcyone's son)

Hyrieus (Greek)

Iache (oceanid)

Iaera (nereid)

Ianassa (nereid)

Ianeira (Nereid)

Ianeira (Oceanid)

Ianthe (oceanid)

Iasis (Ionid)

Icthyocentaurs

Ida (oceanid)

Idyia (oceanid)

Iku-Turso

Ione (nereid)

Iphianassa (nereid)

Jūras māte

Jūratė (Lithuanian)

Kabeirides

Katthveli

Kólga (wave maiden)

Kópakonan

Laomedeia (nereid)

Leiagore (nereid)

Leuce (oceanid)

Leucippe (oceanid)

Libya (oceanid)

Ligeia (Nereid)

Ligeia (Siren)

Limnoreia (nereid)

Lir/ Ler/ Llŷr

Longana

Lycorias (Nereid)

Lysianassa (Nereid)

Lysithea (oceanid)

Maera (Nereid)

Manannán/ Manawydan fab Llŷr/ Bodach/ Gilla Decair

Margýgr

Marmennill

Meduza (Russian)

Melia (oceanid)

Meliboea (oceanid)

Melite (Nereid)

Melite (Oceanid)

Melobosis (Oceanid)

Menestho (Oceanid)

Menippe (Nereid)

Menippe (Oceanid)

Mereveised (Estonian)

Merfolk/ Ben-varrey/ Dinnymara/ Mereminne/ Merenneito (Finnish)/ Morvoren

Mermaid of Warsaw

Merman (Agnete og Havmanden)

Merman (Doll i' the Grass)

Merope (Oceanid)

Merrow/ Murúch

Mopsopia (oceanid)

Morskoy Tsar

Moryana

Morzeczki

Muirdris

Nastasia of the sea

Nausithoe (Nereid)

Neaera (Nereid)

Neaera (Oceanid)

Nëczk

Nemertes (Nereid)

Nemesis (oceanid)

Neomeris (Nereid)

Nereid

Nereus

Nerites (mythology)

Neso (Nereid)

Nymph

Nysiad/ Nymphs Dodonides

Oceanid

Oceanus

Ocyrrhoe (Oceanid)

Orithyia (Nereid)

Panopea (Nereid)

Pardalokampoi

Pasithea (Nereid)

Pasithoe (oceanid)

Pedile (Nysiad)

Peitho (oceanid)

Pemphredo (Graeae)

Periboea (oceanid)

Perse (oceanid)

Petraea (oceanid)

Phaeno (oceanid)

Pherusa (Nereid)

Philyra (Oceanid)

Phyllodoce (Nereid)

Pleione (oceanid)

Plexaure (Nereid)

Plexaure (Oceanid)

Ploto (Nereid)

Plouto (Oceanid)

Polydora (Oceanid)

Polymno (Nysiad)

Polynoe (Nereid)

Polynome (Nereid)

Polyphe (oceanid)

Polyxo (Oceanid)

Pontomedusa (Nereid)

Pontoporeia (Nereid)

Pronoe (Nereid)

Proto (Nereid)

Protomedeia (Nereid)

Prymno (oceanid)

Psamathe (Nereid)

Quinotaur

Rå

Rán

Rhodea (oceanid)

Rhodope (Oceanid)

Saeftinghe mermaid

Saiva- neida

Sao (Nereid)

Sarmatian Sea Snail

Sea Mither/ Sea Midder

Sea Monk

Selkie/ Saelkie/ Sejlki/ Seal Folk/ Maighdeann-mhara/ Moidyn varrey/ Roane/ Selshamurinn

Selkolla

Sellő (Hungarian)

Seonaidh

Siren

Sjóvættir

Speio (Nereid)

Stia (Macedonian)

Stilbo (oceanid)

Styx (Oceanid)

Super-otter

Taurokampoi

Telchines

Telesto (oceanid)

Tethys

Thaleia (Nereid)

Theia (Oceanid)

The Mermaid of Padstow

The Mermaid of Zennor

Themisto (Nereid)

The Lady of the Flowing Waters (Nart)

The Nine Daughters of Ægir and Rán/ Nine Mothers of Heimdallr

The Sea Tsar (The Sea Tsar and Vasilísa the Wise)

Thoe (Nereid)

Thoe (Oceanid)

Thraike (oceanid)

Tyche (oceanid)

Urania (oceanid)

Vættir

Vasilisa the Wise (The Sea Tsar and Vasilísa the Wise)

Vasilisa the Wise’s Sisters (The Sea Tsar and Vasilísa the Wise)

Vellamo (Finnish)

Xanthe (Nereid)

Xanthe (Oceanid)

Zeuxo (Oceanid)

Zitiron

1 note

·

View note

Text

Can't believe Iphigenia and Iphianassa are the same person, but Eteocles and Eteoclus are two different guys

#anyways thinking about how female names are so much more fluid within greek mythology#and what that tells us about gender roles#*potentially the same person

2 notes

·

View notes