#international trade statistics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Unlocking International Markets: Trade Statistics by Country

In today's interconnected global economy, understanding trade statistics by country is essential for businesses, investors, and policymakers alike. Trade statistics provide a detailed view of the flow of goods and services across borders, revealing trends, opportunities, and potential risks. This wealth of data is not just about numbers; it’s about strategic decision-making that can shape the future of economies and businesses. In this article, we’ll explore the significance of trade statistics, how they’re collected, and how you can leverage them to your advantage.

The Importance of Trade Statistics by Country:

Trade statistics offer a clear snapshot of a country’s economic interactions with the rest of the world. This data helps identify which countries are growing their export markets, which are reliant on imports, and how trade balances shift over time. The value of understanding trade statistics by country lies in its ability to:

1. Identify Market Opportunities: For businesses looking to expand, trade statistics reveal which countries are importing particular goods and services. This data helps tailor marketing strategies to tap into the most promising international markets.

2. Support Government Policy: Policymakers rely on trade data to negotiate trade agreements and establish tariffs or other trade regulations. Monitoring a country’s trade performance helps governments make informed decisions on how to promote economic stability and growth.

3. Economic Health Indicator: Trade statistics are key economic indicators, showing the strength of a country’s production capabilities, consumer demand, and overall financial stability. A country with increasing exports, for instance, signals strong global competitiveness, while rising imports may indicate robust domestic consumption.

Key Sources of Trade Statistics:

Various sources compile and publish trade statistics, ensuring the data is accurate and up-to-date. Key sources include:

1. Government Agencies: National customs offices and statistical bureaus collect detailed data on trade activities. This data includes the type and value of goods moving in and out of the country.

2. International Organizations: Global institutions like the World Bank, World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) gather and harmonize trade data across multiple countries to provide comprehensive global reports.

3. Private Sector Reports: Industry-specific associations often track trade trends within their sectors. This information helps businesses understand the performance of specific markets and sectors in different countries.

Key Trade Indicators:

When analyzing trade statistics by country, several key indicators provide a deeper understanding of a country’s trade dynamics:

1. Exports and Imports: These figures reflect the total value of goods and services a country sells to and buys from other nations.

2. Trade Balance: This is the difference between a country’s exports and imports. A positive trade balance (surplus) can indicate a strong export market, while a negative balance (deficit) may suggest reliance on imports.

3. Trade Partners: Identifying major trade partners is crucial. It helps businesses and governments understand where their economic ties are strongest and where new opportunities might emerge.

4. Product Categories: Understanding which product categories dominate a country’s trade portfolio provides insight into that nation’s competitive industries and export strength.

Using Trade Statistics for Strategic Insights:

Trade statistics can be a powerful tool for businesses, investors, and policymakers:

1. Business Expansion: Companies can use trade data to identify growing demand for their products in specific countries, enabling them to target international markets more effectively.

2. Investment Decisions: Investors use trade data to assess economic trends in different countries. A strong export growth rate could indicate a stable investment environment, while fluctuations in trade balances might suggest financial risks.

3. Policymaking: Governments use trade statistics to craft trade agreements, adjust tariffs, and manage international relations. Monitoring these trends helps policymakers anticipate economic challenges and opportunities.

Conclusion:

Trade statistics by country are more than just numbers—they are a roadmap to global economic dynamics. By analyzing these statistics, businesses can uncover lucrative markets, governments can formulate sound trade policies, and investors can make more informed decisions. In an era of increasing globalization, understanding trade patterns by country is key to navigating the complex world of international commerce. Whether you are a business looking to expand, a policymaker shaping economic policy, or an investor seeking growth, trade statistics provide valuable insights to guide your strategy.

#trade data#trade data statistics supplier#global trade data#international trade statistics#Trade Statistics by Country

0 notes

Text

Indonesia Import & Export Data Analysis: Trends for 2024-2025

Indonesia stands as one of Southeast Asia’s largest economies, and its import-export activities play a crucial role in shaping the nation’s economic landscape. For businesses, investors, and analysts looking to understand market trends, having access to Indonesia import data and Indonesia export and import statistics is essential for making informed decisions. The country’s import-export sector is driven by various factors, such as natural resources, manufactured goods, and trade agreements. In this article, we will explore the Indonesia import export data for the year 2024-2025, focusing on trends, key sectors, and future forecasts.

Understanding Indonesia's Import and Export Data

1. Indonesia Import Data for 2024-2025

Indonesia’s import sector continues to evolve as demand for raw materials, machinery, and consumer goods remains high. As the nation moves towards industrialization and urbanization, key imports include:

Machinery and Equipment: These are essential for the expansion of Indonesia’s manufacturing and industrial sectors. With a growing demand for infrastructure development, machinery imports, particularly for construction, electrical equipment, and automotive sectors, are expected to rise significantly in 2024-2025.

Chemical Products: Indonesia relies on chemicals for its manufacturing processes, including the production of pharmaceuticals, textiles, and food products. The demand for chemicals is anticipated to grow as various industries require advanced chemical solutions.

Petroleum Products: Despite Indonesia’s significant oil reserves, it still imports refined petroleum products to meet domestic consumption, especially as demand for energy continues to rise.

Consumer Goods: Indonesia’s middle class is expanding, and with this demographic growth, the demand for consumer goods such as electronics, vehicles, and food products is projected to continue increasing in the coming years.

2. Indonesia Export and Import Statistics for 2024-2025

Indonesia’s exports are primarily driven by natural resources, including palm oil, coal, petroleum, and rubber. According to Indonesia export and import statistics, several key commodities are expected to dominate in 2024-2025:

Mineral Fuels: Coal remains one of Indonesia’s top exports, with significant shipments to countries like China and India. Due to the global demand for energy, the coal export market is expected to remain strong throughout 2024-2025.

Palm Oil: As one of the world’s largest producers, Indonesia continues to lead in palm oil production. This product is primarily exported to countries like India, China, and the European Union. The growth in palm oil exports is expected to be stable in the coming years.

Electrical and Electronics: As technology advances, exports in electrical machinery and electronics are forecast to grow. Indonesia is increasingly exporting smartphones, computers, and related components, particularly to neighboring Asian markets.

Automobiles and Parts: Indonesia has become a significant exporter of vehicles and automobile parts, especially to ASEAN nations. As the automotive sector expands, the export of cars and auto components will likely show positive growth in 2024-2025.

3. Import Data of Indonesia: Key Trading Partners

The Import Data of Indonesia reveals that the country’s primary trading partners include China, Japan, the United States, and Singapore. These nations supply a wide range of goods to Indonesia, which are critical to maintaining its industrial growth and meeting domestic demand.

China: As Indonesia’s largest import partner, China supplies a significant portion of machinery, electronics, and chemicals. With ongoing infrastructure projects in Indonesia, Chinese products, particularly in construction and telecommunications, are expected to see continued import demand.

Japan: Japan exports high-quality machinery, vehicles, and chemicals to Indonesia. As Indonesia focuses on expanding its manufacturing capabilities, imports from Japan are expected to remain integral to its industrialization efforts.

United States: The U.S. exports agricultural products, industrial machinery, and high-tech equipment to Indonesia. The ongoing economic cooperation between the two nations will likely continue to drive trade in the upcoming years.

Singapore: As a key regional hub, Singapore is a significant source of refined petroleum products, chemicals, and electronic goods. Indonesia imports a wide variety of products from Singapore, supporting its growing sectors in energy, technology, and manufacturing.

4. Trends in Indonesia’s Import-Export Data for 2024-2025

Trade Balance and Currency Impact: In 2024-2025, Indonesia is likely to face challenges related to its trade balance. A higher import bill driven by industrial demand may outpace the growth in exports, potentially affecting the country's currency and trade balance. However, with the government’s focus on boosting export industries, this trend could shift over time.

Regional Trade Agreements: Indonesia's participation in various trade agreements, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), is expected to open new export opportunities, particularly in agricultural and manufacturing sectors. This will also allow Indonesia to access more affordable imports, which could boost domestic industries.

Sustainability Focus: As global markets increasingly prioritize sustainability, Indonesia’s exports, especially in palm oil, coal, and other natural resources, may face greater scrutiny. The country will need to adapt by embracing sustainable practices in agriculture and manufacturing to remain competitive in the international market.

5. Indonesia's Import-Export Data Forecast for 2024-2025

Looking forward to the next few years, Indonesia’s import-export data indicates the country will continue to see growth in trade activities. Imports will be driven by industrialization, energy demands, and consumer goods. Meanwhile, exports will likely remain strong in natural resources, technology, and automotive sectors.

Conclusion

The Indonesia import export data for 2024-2025 paints a picture of a dynamic and evolving trade environment. With its robust import needs and competitive export markets, Indonesia is poised for continued economic growth. By focusing on infrastructure, industrial development, and regional trade partnerships, Indonesia can overcome challenges and capitalize on opportunities in both its import and export sectors. Tracking Indonesia import and export statistics will be crucial for understanding how the nation's trade landscape will unfold in the coming years, offering valuable insights for businesses and investors alike.

#Indonesia export data#Indonesia export statistics#Export Data of Indonesia#Indonesia trade data#Indonesia import data#Indonesia export and import statistics#Indonesia import export data#Import Data of Indonesia#global trade data#international trade#trade data

0 notes

Text

India's textile industry, among the world's largest and oldest, is crucial to its economy, supporting millions and significantly contributing to GDP. In 2022, exports hit $16 billion, projected to exceed $45 billion by 2031. Let's explore recent export statistics, key exporters, and trends using modern HS codes, Get access to textile export data textile exports from india textile exporter in india textile exporting countriesindian textile exports statistics textile hs code

list of textile products exported from india

#export#import#trade data#import data#export data#international trade#global trade data#trade market#custom data#import export data#global business#textile hs code#textile export data#textile exports from india#list of textile products exported from india#indian textile exports statistics#textile export data of india#textile exporter in india#textile exporting countries#textile

0 notes

Text

Look, I'm sorry, there's nothing to learn from this post, this is just me complaining about a lack of legibility and expertise available to the amateur.

I wish that international trade data were easier to make sense of. Sometimes you can go to the larger industry groups and get a PDF that breaks down what's moving where and why, but other times the data seems sparse on the ground, or it's just not public-facing, so I'm left with these statistics that don't actually tell me much.

I was looking up potato imports and exports, to win an argument online (of course), and found this in the list of largest import flows:

Imports to Canada from USA (1.52% of the world imports, $92 million according to external trade statistics of Canada)

Imports to USA from Canada (7.4% of the world imports, $447 million according to external trade statistics of USA)

So of the top 10 largest import flows for "potatoes, fresh or chilled", two of those spots are ... USA and Canada sending potatoes back and forth across the border?

Obviously there's got to be some kind of reason for this. The United States and Canada have a long border with each other, so maybe, in spite of friction crossing the border, it actually does make sense for certain parts of the United States to trade their potatoes to Canada, and in other places, for Canada to trade their potatoes to the United States.

Or possibly these are different types of potatoes, with certain kinds suited to growing in Canada and other kinds suited the growing in the United States, and those are what's getting traded across borders.

Or maybe it's the growing season, which is different between the two countries, so that it's a seasonality thing, and the flow of imports depends on the month, which would make sense.

Or the border simply does not provide all that much friction, and so we should expect that they just trade back and forth, because this is as meaningless as trade across arbitrary points within a singular country.

The data seems very scant though, and frustratingly, I feel like there's a potato farmer who just has this information at their fingertips. I am not averse to emailing random farms in Idaho, but I'll exhaust some other avenues first.

Like asking tumblr!

Are you a potato farmer, or do you know one? Can you make sense of the intra-industry trade thing for me with some specific examples of what's going on?

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

God, since the whole “bear vs man” thing came up again

Everything I’ve seen said in defence of using this as a framework to mean something has always relied on a cherry picking of stats and broad application of those to serve bio- and/or gender-essentialism.

The question is meant to be a direct reference to the fact that there were women hikers on TikTok actively stating that in their experience they end up more afraid coming across a man than a bear because if the bear were to attack at least people would believe that.

Great—same if a woman attacked you in the woods. You’d probably actually be believed more if your story is assault by a man than assault by a woman, even though I’d definitely agree that assault by bear would be believed more readily than either.

But men are more statistically likely to commit violent crime! So actually it makes sense that people would be more afraid to meet a man over a bear instead of a woman over a bear!

And people close to you are more statistically likely to commit violent crimes against you than strangers are, and yet I’m not seeing people out here using that statistic to demonize the idea of close friends going hiking together by-way-of “would you rather go hiking in a remote area alone and come across a bear or would you rather trade-off that bear encounter with a having gone with a friend?” Even though you’re even more likely to be violently assaulted by someone you know than some random man you encounter, so you’d think that the same people wanting to enforce fear of being in remote areas with strange men would want to enforce fear of being in remote areas with those you’re close with.

The thing is, what they’re doing is reinforcing their own bio/gender-essentialism (or sometimes reinforcing a trauma response, or both at once, but I’m specifically talking about the bio/gender-essentialism in this post (and also reinforcing stranger danger stuff they may have internalized but that’s even further digression)), as I said, by cherry picking which statistics they’re using to speak about the dangers of existing in the world.

And this isn’t even getting into how many other unstated assumptions are going on in the reading of the question and subsequent answer of it—just to quickly point out one: the assumption that we’re dealing with a potentially malicious man pops up very quickly in a lot of discussions, but I don’t often see people making similar assumption of the bear they’re considering being a bear that is more likely to aggress at you than the average bear (for example, by you unknowingly being between a mother bear and her cubs, by the bear being seriously ill or injured…)

But yeah, anyway, all of this to say that the “man vs bear” thing serves no utility beyond maybe dissecting the question further to see in what other ways we as people will create new ways to serve up the same bio-/gender-essentialism.

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

I thought y'all should read this

I have a free trial to News+ so I copy-pasted it for you here. I don't think Jonathan Haidt would object to more people having this info.

Tumblr wouldn't let me post it until i removed all the links to Haidt's sources. You'll have to take my word that everything is sourced.

End the Phone-Based Childhood Now

The environment in which kids grow up today is hostile to human development.

By Jonathan Haidt

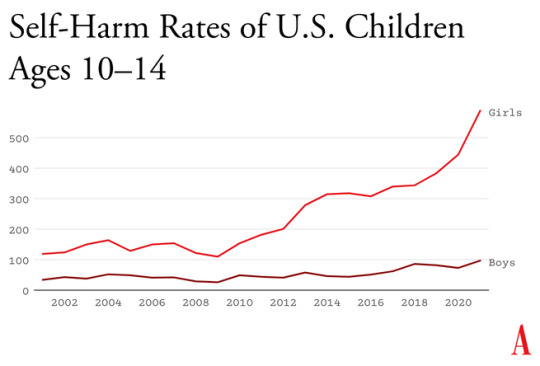

Something went suddenly and horribly wrong for adolescents in the early 2010s. By now you’ve likely seen the statistics: Rates of depression and anxiety in the United States—fairly stable in the 2000s—rose by more than 50 percent in many studies from 2010 to 2019. The suicide rate rose 48 percent for adolescents ages 10 to 19. For girls ages 10 to 14, it rose 131 percent.

The problem was not limited to the U.S.: Similar patterns emerged around the same time in Canada, the U.K., Australia, New Zealand, the Nordic countries, and beyond. By a variety of measures and in a variety of countries, the members of Generation Z (born in and after 1996) are suffering from anxiety, depression, self-harm, and related disorders at levels higher than any other generation for which we have data.

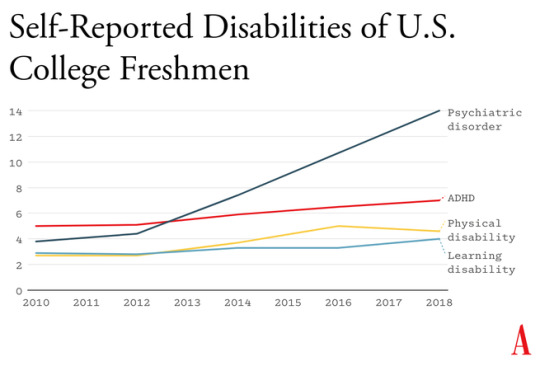

The decline in mental health is just one of many signs that something went awry. Loneliness and friendlessness among American teens began to surge around 2012. Academic achievement went down, too. According to “The Nation’s Report Card,” scores in reading and math began to decline for U.S. students after 2012, reversing decades of slow but generally steady increase. PISA, the major international measure of educational trends, shows that declines in math, reading, and science happened globally, also beginning in the early 2010s.

As the oldest members of Gen Z reach their late 20s, their troubles are carrying over into adulthood. Young adults are dating less, having less sex, and showing less interest in ever having children than prior generations. They are more likelyto live with their parents. They were less likely to get jobs as teens, and managers say they are harder to work with. Many of these trends began with earlier generations, but most of them accelerated with Gen Z.

Surveys show that members of Gen Z are shyer and more risk averse than previous generations, too, and risk aversion may make them less ambitious. In an interview last May, OpenAI co-founder Sam Altman and Stripe co-founder Patrick Collison noted that, for the first time since the 1970s, none of Silicon Valley’s preeminent entrepreneurs are under 30. “Something has really gone wrong,” Altman said. In a famously young industry, he was baffled by the sudden absence of great founders in their 20s.

Generations are not monolithic, of course. Many young people are flourishing. Taken as a whole, however, Gen Z is in poor mental health and is lagging behind previous generations on many important metrics. And if a generation is doing poorly––if it is more anxious and depressed and is starting families, careers, and important companies at a substantially lower rate than previous generations––then the sociological and economic consequences will be profound for the entire society.

What happened in the early 2010s that altered adolescent development and worsened mental health? Theories abound, but the fact that similar trends are found in many countries worldwide means that events and trends that are specific to the United States cannot be the main story.

I think the answer can be stated simply, although the underlying psychology is complex: Those were the years when adolescents in rich countries traded in their flip phones for smartphones and moved much more of their social lives online—particularly onto social-media platforms designed for virality and addiction. Once young people began carrying the entire internet in their pockets, available to them day and night, it altered their daily experiences and developmental pathways across the board. Friendship, dating, sexuality, exercise, sleep, academics, politics, family dynamics, identity—all were affected. Life changed rapidly for younger children, too, as they began to get access to their parents’ smartphones and, later, got their own iPads, laptops, and even smartphones during elementary school.

As a social psychologist who has long studied social and moral development, I have been involved in debates about the effects of digital technology for years. Typically, the scientific questions have been framed somewhat narrowly, to make them easier to address with data. For example, do adolescents who consume more social media have higher levels of depression? Does using a smartphone just before bedtime interfere with sleep? The answer to these questions is usually found to be yes, although the size of the relationship is often statistically small, which has led some researchers to conclude that these new technologies are not responsible for the gigantic increases in mental illness that began in the early 2010s.

But before we can evaluate the evidence on any one potential avenue of harm, we need to step back and ask a broader question: What is childhood––including adolescence––and how did it change when smartphones moved to the center of it? If we take a more holistic view of what childhood is and what young children, tweens, and teens need to do to mature into competent adults, the picture becomes much clearer. Smartphone-based life, it turns out, alters or interferes with a great number of developmental processes.

The intrusion of smartphones and social media are not the only changes that have deformed childhood. There’s an important backstory, beginning as long ago as the 1980s, when we started systematically depriving children and adolescents of freedom, unsupervised play, responsibility, and opportunities for risk taking, all of which promote competence, maturity, and mental health. But the change in childhood accelerated in the early 2010s, when an already independence-deprived generation was lured into a new virtual universe that seemed safe to parents but in fact is more dangerous, in many respects, than the physical world.

My claim is that the new phone-based childhood that took shape roughly 12 years ago is making young people sick and blocking their progress to flourishing in adulthood. We need a dramatic cultural correction, and we need it now.

1. The Decline of Play and Independence

Human brains are extraordinarily large compared with those of other primates, and human childhoods are extraordinarily long, too, to give those large brains time to wire up within a particular culture. A child’s brain is already 90 percent of its adult size by about age 6. The next 10 or 15 years are about learning norms and mastering skills—physical, analytical, creative, and social. As children and adolescents seek out experiences and practice a wide variety of behaviors, the synapses and neurons that are used frequently are retained while those that are used less often disappear. Neurons that fire together wire together, as brain researchers say.

Brain development is sometimes said to be “experience-expectant,” because specific parts of the brain show increased plasticity during periods of life when an animal’s brain can “expect” to have certain kinds of experiences. You can see this with baby geese, who will imprint on whatever mother-sized object moves in their vicinity just after they hatch. You can see it with human children, who are able to learn languages quickly and take on the local accent, but only through early puberty; after that, it’s hard to learn a language and sound like a native speaker. There is also some evidence of a sensitive period for cultural learning more generally. Japanese children who spent a few years in California in the 1970s came to feel “American” in their identity and ways of interacting only if they attended American schools for a few years between ages 9 and 15. If they left before age 9, there was no lasting impact. If they didn’t arrive until they were 15, it was too late; they didn’t come to feel American.

Human childhood is an extended cultural apprenticeship with different tasks at different ages all the way through puberty. Once we see it this way, we can identify factors that promote or impede the right kinds of learning at each age. For children of all ages, one of the most powerful drivers of learning is the strong motivation to play. Play is the work of childhood, and all young mammals have the same job: to wire up their brains by playing vigorously and often, practicing the moves and skills they’ll need as adults. Kittens will play-pounce on anything that looks like a mouse tail. Human children will play games such as tag and sharks and minnows, which let them practice both their predator skills and their escaping-from-predator skills. Adolescents will play sports with greater intensity, and will incorporate playfulness into their social interactions—flirting, teasing, and developing inside jokes that bond friends together. Hundreds of studies on young rats, monkeys, and humans show that young mammals want to play, need to play, and end up socially, cognitively, and emotionally impaired when they are deprived of play.

One crucial aspect of play is physical risk taking. Children and adolescents must take risks and fail—often—in environments in which failure is not very costly. This is how they extend their abilities, overcome their fears, learn to estimate risk, and learn to cooperate in order to take on larger challenges later. The ever-present possibility of getting hurt while running around, exploring, play-fighting, or getting into a real conflict with another group adds an element of thrill, and thrilling play appears to be the most effective kind for overcoming childhood anxieties and building social, emotional, and physical competence. The desire for risk and thrill increases in the teen years, when failure might carry more serious consequences. Children of all ages need to choose the risk they are ready for at a given moment. Young people who are deprived of opportunities for risk taking and independent exploration will, on average, develop into more anxious and risk-averse adults.

Human childhood and adolescence evolved outdoors, in a physical world full of dangers and opportunities. Its central activities––play, exploration, and intense socializing––were largely unsupervised by adults, allowing children to make their own choices, resolve their own conflicts, and take care of one another. Shared adventures and shared adversity bound young people together into strong friendship clusters within which they mastered the social dynamics of small groups, which prepared them to master bigger challenges and larger groups later on.

And then we changed childhood.

The changes started slowly in the late 1970s and ’80s, before the arrival of the internet, as many parents in the U.S. grew fearful that their children would be harmed or abducted if left unsupervised. Such crimes have always been extremely rare, but they loomed larger in parents’ minds thanks in part to rising levels of street crime combined with the arrival of cable TV, which enabled round-the-clock coverage of missing-children cases. A general decline in social capital––the degree to which people knew and trusted their neighbors and institutions––exacerbated parental fears. Meanwhile, rising competition for college admissions encouraged more intensive forms of parenting. In the 1990s, American parents began pulling their children indoors or insisting that afternoons be spent in adult-run enrichment activities. Free play, independent exploration, and teen-hangout time declined.

In recent decades, seeing unchaperoned children outdoors has become so novel that when one is spotted in the wild, some adults feel it is their duty to call the police. In 2015, the Pew Research Center found that parents, on average, believed that children should be at least 10 years old to play unsupervised in front of their house, and that kids should be 14 before being allowed to go unsupervised to a public park. Most of these same parents had enjoyed joyous and unsupervised outdoor play by the age of 7 or 8.

2. The Virtual World Arrives in Two Waves

The internet, which now dominates the lives of young people, arrived in two waves of linked technologies. The first one did little harm to Millennials. The second one swallowed Gen Z whole.

The first wave came ashore in the 1990s with the arrival of dial-up internet access, which made personal computers good for something beyond word processing and basic games. By 2003, 55 percent of American households had a computer with (slow) internet access. Rates of adolescent depression, loneliness, and other measures of poor mental health did not rise in this first wave. If anything, they went down a bit. Millennial teens (born 1981 through 1995), who were the first to go through puberty with access to the internet, were psychologically healthier and happier, on average, than their older siblings or parents in Generation X (born 1965 through 1980).

The second wave began to rise in the 2000s, though its full force didn’t hit until the early 2010s. It began rather innocently with the introduction of social-media platforms that helped people connect with their friends. Posting and sharing content became much easier with sites such as Friendster (launched in 2003), Myspace (2003), and Facebook (2004).

Teens embraced social media soon after it came out, but the time they could spend on these sites was limited in those early years because the sites could only be accessed from a computer, often the family computer in the living room. Young people couldn’t access social media (and the rest of the internet) from the school bus, during class time, or while hanging out with friends outdoors. Many teens in the early-to-mid-2000s had cellphones, but these were basic phones (many of them flip phones) that had no internet access. Typing on them was difficult––they had only number keys. Basic phones were tools that helped Millennials meet up with one another in person or talk with each other one-on-one. I have seen no evidence to suggest that basic cellphones harmed the mental health of Millennials.

It was not until the introduction of the iPhone (2007), the App Store (2008), and high-speed internet (which reached 50 percent of American homes in 2007)—and the corresponding pivot to mobile made by many providers of social media, video games, and porn—that it became possible for adolescents to spend nearly every waking moment online. The extraordinary synergy among these innovations was what powered the second technological wave. In 2011, only 23 percent of teens had a smartphone. By 2015, that number had risen to 73 percent, and a quarter of teens said they were online “almost constantly.” Their younger siblings in elementary school didn’t usually have their own smartphones, but after its release in 2010, the iPad quickly became a staple of young children’s daily lives. It was in this brief period, from 2010 to 2015, that childhood in America (and many other countries) was rewired into a form that was more sedentary, solitary, virtual, and incompatible with healthy human development.

3. Techno-optimism and the Birth of the Phone-Based Childhood

The phone-based childhood created by that second wave—including not just smartphones themselves, but all manner of internet-connected devices, such as tablets, laptops, video-game consoles, and smartwatches—arrived near the end of a period of enormous optimism about digital technology. The internet came into our lives in the mid-1990s, soon after the fall of the Soviet Union. By the end of that decade, it was widely thought that the web would be an ally of democracy and a slayer of tyrants. When people are connected to each other, and to all the information in the world, how could any dictator keep them down?

In the 2000s, Silicon Valley and its world-changing inventions were a source of pride and excitement in America. Smart and ambitious young people around the world wanted to move to the West Coast to be part of the digital revolution. Tech-company founders such as Steve Jobs and Sergey Brin were lauded as gods, or at least as modern Prometheans, bringing humans godlike powers. The Arab Spring bloomed in 2011 with the help of decentralized social platforms, including Twitter and Facebook. When pundits and entrepreneurs talked about the power of social media to transform society, it didn’t sound like a dark prophecy.

You have to put yourself back in this heady time to understand why adults acquiesced so readily to the rapid transformation of childhood. Many parents had concerns, even then, about what their children were doing online, especially because of the internet’s ability to put children in contact with strangers. But there was also a lot of excitement about the upsides of this new digital world. If computers and the internet were the vanguards of progress, and if young people––widely referred to as “digital natives”––were going to live their lives entwined with these technologies, then why not give them a head start? I remember how exciting it was to see my 2-year-old son master the touch-and-swipe interface of my first iPhone in 2008. I thought I could see his neurons being woven together faster as a result of the stimulation it brought to his brain, compared to the passivity of watching television or the slowness of building a block tower. I thought I could see his future job prospects improving.

Touchscreen devices were also a godsend for harried parents. Many of us discovered that we could have peace at a restaurant, on a long car trip, or at home while making dinner or replying to emails if we just gave our children what they most wanted: our smartphones and tablets. We saw that everyone else was doing it and figured it must be okay.

It was the same for older children, desperate to join their friends on social-media platforms, where the minimum age to open an account was set by law to 13, even though no research had been done to establish the safety of these products for minors. Because the platforms did nothing (and still do nothing) to verify the stated age of new-account applicants, any 10-year-old could open multiple accounts without parental permission or knowledge, and many did. Facebook and later Instagram became places where many sixth and seventh graders were hanging out and socializing. If parents did find out about these accounts, it was too late. Nobody wanted their child to be isolated and alone, so parents rarely forced their children to shut down their accounts.

We had no idea what we were doing.

4. The High Cost of a Phone-Based Childhood

In Walden, his 1854 reflection on simple living, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “The cost of a thing is the amount of … life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.” It’s an elegant formulation of what economists would later call the opportunity cost of any choice—all of the things you can no longer do with your money and time once you’ve committed them to something else. So it’s important that we grasp just how much of a young person’s day is now taken up by their devices.

The numbers are hard to believe. The most recent Gallup data show that American teens spend about five hours a day just on social-media platforms (including watching videos on TikTok and YouTube). Add in all the other phone- and screen-based activities, and the number rises to somewhere between seven and nine hours a day, on average. The numbers are even higher in single-parent and low-income families, and among Black, Hispanic, and Native American families.

In Thoreau’s terms, how much of life is exchanged for all this screen time? Arguably, most of it. Everything else in an adolescent’s day must get squeezed down or eliminated entirely to make room for the vast amount of content that is consumed, and for the hundreds of “friends,” “followers,” and other network connections that must be serviced with texts, posts, comments, likes, snaps, and direct messages. I recently surveyed my students at NYU, and most of them reported that the very first thing they do when they open their eyes in the morning is check their texts, direct messages, and social-media feeds. It’s also the last thing they do before they close their eyes at night. And it’s a lot of what they do in between.

The amount of time that adolescents spend sleeping declined in the early 2010s, and many studies tie sleep loss directly to the use of devices around bedtime, particularly when they’re used to scroll through social media. Exercise declined, too, which is unfortunate because exercise, like sleep, improves both mental and physical health. Book reading has been declining for decades, pushed aside by digital alternatives, but the decline, like so much else, sped up in the early 2010s. With passive entertainment always available, adolescent minds likely wander less than they used to; contemplation and imagination might be placed on the list of things winnowed down or crowded out.

But perhaps the most devastating cost of the new phone-based childhood was the collapse of time spent interacting with other people face-to-face. A study of how Americans spend their time found that, before 2010, young people (ages 15 to 24) reported spending far more time with their friends (about two hours a day, on average, not counting time together at school) than did older people (who spent just 30 to 60 minutes with friends). Time with friends began decreasing for young people in the 2000s, but the drop accelerated in the 2010s, while it barely changed for older people. By 2019, young people’s time with friends had dropped to just 67 minutes a day. It turns out that Gen Z had been socially distancing for many years and had mostly completed the project by the time COVID-19 struck.

You might question the importance of this decline. After all, isn’t much of this online time spent interacting with friends through texting, social media, and multiplayer video games? Isn’t that just as good?

Some of it surely is, and virtual interactions offer unique benefits too, especially for young people who are geographically or socially isolated. But in general, the virtual world lacks many of the features that make human interactions in the real world nutritious, as we might say, for physical, social, and emotional development. In particular, real-world relationships and social interactions are characterized by four features—typical for hundreds of thousands of years—that online interactions either distort or erase.

First, real-world interactions are embodied, meaning that we use our hands and facial expressions to communicate, and we learn to respond to the body language of others. Virtual interactions, in contrast, mostly rely on language alone. No matter how many emojis are offered as compensation, the elimination of communication channels for which we have eons of evolutionary programming is likely to produce adults who are less comfortable and less skilled at interacting in person.

Second, real-world interactions are synchronous; they happen at the same time. As a result, we learn subtle cues about timing and conversational turn taking. Synchronous interactions make us feel closer to the other person because that’s what getting “in sync” does. Texts, posts, and many other virtual interactions lack synchrony. There is less real laughter, more room for misinterpretation, and more stress after a comment that gets no immediate response.

Third, real-world interactions primarily involve one‐to‐one communication, or sometimes one-to-several. But many virtual communications are broadcast to a potentially huge audience. Online, each person can engage in dozens of asynchronous interactions in parallel, which interferes with the depth achieved in all of them. The sender’s motivations are different, too: With a large audience, one’s reputation is always on the line; an error or poor performance can damage social standing with large numbers of peers. These communications thus tend to be more performative and anxiety-inducing than one-to-one conversations.

Finally, real-world interactions usually take place within communities that have a high bar for entry and exit, so people are strongly motivated to invest in relationships and repair rifts when they happen. But in many virtual networks, people can easily block others or quit when they are displeased. Relationships within such networks are usually more disposable.

These unsatisfying and anxiety-producing features of life online should be recognizable to most adults. Online interactions can bring out antisocial behavior that people would never display in their offline communities. But if life online takes a toll on adults, just imagine what it does to adolescents in the early years of puberty, when their “experience expectant” brains are rewiring based on feedback from their social interactions.

Kids going through puberty online are likely to experience far more social comparison, self-consciousness, public shaming, and chronic anxiety than adolescents in previous generations, which could potentially set developing brains into a habitual state of defensiveness. The brain contains systems that are specialized for approach (when opportunities beckon) and withdrawal (when threats appear or seem likely). People can be in what we might call “discover mode” or “defend mode” at any moment, but generally not both. The two systems together form a mechanism for quickly adapting to changing conditions, like a thermostat that can activate either a heating system or a cooling system as the temperature fluctuates. Some people’s internal thermostats are generally set to discover mode, and they flip into defend mode only when clear threats arise. These people tend to see the world as full of opportunities. They are happier and less anxious. Other people’s internal thermostats are generally set to defend mode, and they flip into discover mode only when they feel unusually safe. They tend to see the world as full of threats and are more prone to anxiety and depressive disorders.

A simple way to understand the differences between Gen Z and previous generations is that people born in and after 1996 have internal thermostats that were shifted toward defend mode. This is why life on college campuses changed so suddenly when Gen Z arrived, beginning around 2014. Students began requesting “safe spaces” and trigger warnings. They were highly sensitive to “microaggressions” and sometimes claimed that words were “violence.” These trends mystified those of us in older generations at the time, but in hindsight, it all makes sense. Gen Z students found words, ideas, and ambiguous social encounters more threatening than had previous generations of students because we had fundamentally altered their psychological development.

5. So Many Harms

The debate around adolescents’ use of smartphones and social media typically revolves around mental health, and understandably so. But the harms that have resulted from transforming childhood so suddenly and heedlessly go far beyondmental health. I’ve touched on some of them—social awkwardness, reduced self-confidence, and a more sedentary childhood. Here are three additional harms.

Fragmented Attention, Disrupted Learning

Staying on task while sitting at a computer is hard enough for an adult with a fully developed prefrontal cortex. It is far more difficult for adolescents in front of their laptop trying to do homework. They are probably less intrinsically motivated to stay on task. They’re certainly less able, given their undeveloped prefrontal cortex, and hence it’s easy for any company with an app to lure them away with an offer of social validation or entertainment. Their phones are pinging constantly—one study found that the typical adolescent now gets 237 notifications a day, roughly 15 every waking hour. Sustained attention is essential for doing almost anything big, creative, or valuable, yet young people find their attention chopped up into little bits by notifications offering the possibility of high-pleasure, low-effort digital experiences.

It even happens in the classroom. Studies confirm that when students have access to their phones during class time, they use them, especially for texting and checking social media, and their grades and learning suffer. This might explain why benchmark test scores began to decline in the U.S. and around the world in the early 2010s—well before the pandemic hit.

Addiction and Social Withdrawal

The neural basis of behavioral addiction to social media or video games is not exactly the same as chemical addiction to cocaine or opioids. Nonetheless, they all involve abnormally heavy and sustained activation of dopamine neurons and reward pathways. Over time, the brain adapts to these high levels of dopamine; when the child is not engaged in digital activity, their brain doesn’t have enough dopamine, and the child experiences withdrawal symptoms. These generally include anxiety, insomnia, and intense irritability. Kids with these kinds of behavioral addictions often become surly and aggressive, and withdraw from their families into their bedrooms and devices.

Social-media and gaming platforms were designed to hook users. How successful are they? How many kids suffer from digital addictions?

The main addiction risks for boys seem to be video games and porn. “Internet gaming disorder,” which was added to the main diagnosis manual of psychiatry in 2013 as a condition for further study, describes “significant impairment or distress” in several aspects of life, along with many hallmarks of addiction, including an inability to reduce usage despite attempts to do so. Estimates for the prevalence of IGD range from 7 to 15 percent among adolescent boys and young men. As for porn, a nationally representative survey of American adults published in 2019 found that 7 percent of American men agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I am addicted to pornography”—and the rates were higher for the youngest men.

Girls have much lower rates of addiction to video games and porn, but they use social media more intensely than boys do. A study of teens in 29 nations found that between 5 and 15 percent of adolescents engage in what is called “problematic social media use,” which includes symptoms such as preoccupation, withdrawal symptoms, neglect of other areas of life, and lying to parents and friends about time spent on social media. That study did not break down results by gender, but many others have found that rates of “problematic use” are higher for girls.

I don’t want to overstate the risks: Most teens do not become addicted to their phones and video games. But across multiple studies and across genders, rates of problematic use come out in the ballpark of 5 to 15 percent. Is there any other consumer product that parents would let their children use relatively freely if they knew that something like one in 10 kids would end up with a pattern of habitual and compulsive use that disrupted various domains of life and looked a lot like an addiction?

The Decay of Wisdom and the Loss of Meaning

During that crucial sensitive period for cultural learning, from roughly ages 9 through 15, we should be especially thoughtful about who is socializing our children for adulthood. Instead, that’s when most kids get their first smartphone and sign themselves up (with or without parental permission) to consume rivers of content from random strangers. Much of that content is produced by other adolescents, in blocks of a few minutes or a few seconds.

This rerouting of enculturating content has created a generation that is largely cut off from older generations and, to some extent, from the accumulated wisdom of humankind, including knowledge about how to live a flourishing life. Adolescents spend less time steeped in their local or national culture. They are coming of age in a confusing, placeless, ahistorical maelstrom of 30-second stories curated by algorithms designed to mesmerize them. Without solid knowledge of the past and the filtering of good ideas from bad––a process that plays out over many generations––young people will be more prone to believe whatever terrible ideas become popular around them, which might explain why videos showing young people reacting positively to Osama bin Laden’s thoughts about America were trending on TikTok last fall.

All this is made worse by the fact that so much of digital public life is an unending supply of micro dramas about somebody somewhere in our country of 340 million people who did something that can fuel an outrage cycle, only to be pushed aside by the next. It doesn’t add up to anything and leaves behind only a distorted sense of human nature and affairs.

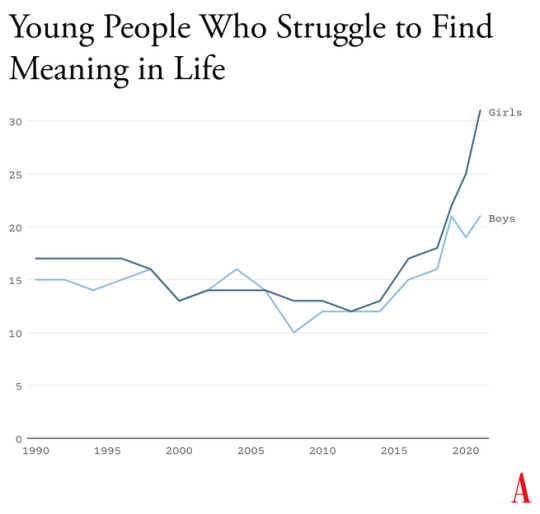

When our public life becomes fragmented, ephemeral, and incomprehensible, it is a recipe for anomie, or normlessness. The great French sociologist Émile Durkheim showed long ago that a society that fails to bind its people together with some shared sense of sacredness and common respect for rules and norms is not a society of great individual freedom; it is, rather, a place where disoriented individuals have difficulty setting goals and exerting themselves to achieve them. Durkheim argued that anomie was a major driver of suicide rates in European countries. Modern scholars continue to draw on his work to understand suicide rates today.

Durkheim’s observations are crucial for understanding what happened in the early 2010s. A long-running survey of American teens found that, from 1990 to 2010, high-school seniors became slightly less likely to agree with statements such as “Life often feels meaningless.” But as soon as they adopted a phone-based life and many began to live in the whirlpool of social media, where no stability can be found, every measure of despair increased. From 2010 to 2019, the number who agreed that their lives felt “meaningless” increased by about 70 percent, to more than one in five.

6. Young People Don’t Like Their Phone-Based Lives

How can I be confident that the epidemic of adolescent mental illness was kicked off by the arrival of the phone-based childhood? Skeptics point to other events as possible culprits, including the 2008 global financial crisis, global warming, the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting and the subsequent active-shooter drills, rising academic pressures, and the opioid epidemic. But while these events might have been contributing factors in some countries, none can explain both the timing and international scope of the disaster.

An additional source of evidence comes from Gen Z itself. With all the talk of regulating social media, raising age limits, and getting phones out of schools, you might expect to find many members of Gen Z writing and speaking out in opposition. I’ve looked for such arguments and found hardly any. In contrast, many young adults tell stories of devastation.

Freya India, a 24-year-old British essayist who writes about girls, explains how social-media sites carry girls off to unhealthy places: “It seems like your child is simply watching some makeup tutorials, following some mental health influencers, or experimenting with their identity. But let me tell you: they are on a conveyor belt to someplace bad. Whatever insecurity or vulnerability they are struggling with, they will be pushed further and further into it.” She continues:

Gen Z were the guinea pigs in this uncontrolled global social experiment. We were the first to have our vulnerabilities and insecurities fed into a machine that magnified and refracted them back at us, all the time, before we had any sense of who we were. We didn’t just grow up with algorithms. They raised us. They rearranged our faces. Shaped our identities. Convinced us we were sick.

Rikki Schlott, a 23-year-old American journalist and co-author of The Canceling of the American Mind, writes,

"The day-to-day life of a typical teen or tween today would be unrecognizable to someone who came of age before the smartphone arrived. Zoomers are spending an average of 9 hours daily in this screen-time doom loop—desperate to forget the gaping holes they’re bleeding out of, even if just for … 9 hours a day. Uncomfortable silence could be time to ponder why they’re so miserable in the first place. Drowning it out with algorithmic white noise is far easier."

A 27-year-old man who spent his adolescent years addicted (his word) to video games and pornography sent me this reflection on what that did to him:

I missed out on a lot of stuff in life—a lot of socialization. I feel the effects now: meeting new people, talking to people. I feel that my interactions are not as smooth and fluid as I want. My knowledge of the world (geography, politics, etc.) is lacking. I didn’t spend time having conversations or learning about sports. I often feel like a hollow operating system.

Or consider what Facebook found in a research project involving focus groups of young people, revealed in 2021 by the whistleblower Frances Haugen: “Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rates of anxiety and depression among teens,” an internal document said. “This reaction was unprompted and consistent across all groups.”

7. Collective-Action Problems

Social-media companies such as Meta, TikTok, and Snap are often compared to tobacco companies, but that’s not really fair to the tobacco industry. It’s true that companies in both industries marketed harmful products to children and tweaked their products for maximum customer retention (that is, addiction), but there’s a big difference: Teens could and did choose, in large numbers, not to smoke. Even at the peak of teen cigarette use, in 1997, nearly two-thirds of high-school students did not smoke.

Social media, in contrast, applies a lot more pressure on nonusers, at a much younger age and in a more insidious way. Once a few students in any middle school lie about their age and open accounts at age 11 or 12, they start posting photos and comments about themselves and other students. Drama ensues. The pressure on everyone else to join becomes intense. Even a girl who knows, consciously, that Instagram can foster beauty obsession, anxiety, and eating disorders might sooner take those risks than accept the seeming certainty of being out of the loop, clueless, and excluded. And indeed, if she resists while most of her classmates do not, she might, in fact, be marginalized, which puts her at risk for anxiety and depression, though via a different pathway than the one taken by those who use social media heavily. In this way, social media accomplishes a remarkable feat: It even harms adolescents who do not use it.

A recent study led by the University of Chicago economist Leonardo Bursztyn captured the dynamics of the social-media trap precisely. The researchers recruited more than 1,000 college students and asked them how much they’d need to be paid to deactivate their accounts on either Instagram or TikTok for four weeks. That’s a standard economist’s question to try to compute the net value of a product to society. On average, students said they’d need to be paid roughly $50 ($59 for TikTok, $47 for Instagram) to deactivate whichever platform they were asked about. Then the experimenters told the students that they were going to try to get most of the others in their school to deactivate that same platform, offering to pay them to do so as well, and asked, Now how much would you have to be paid to deactivate, if most others did so? The answer, on average, was less than zero. In each case, most students were willing to pay to have that happen.

Social media is all about network effects. Most students are only on it because everyone else is too. Most of them would prefer that nobody be on these platforms. Later in the study, students were asked directly, “Would you prefer to live in a world without Instagram [or TikTok]?” A majority of students said yes––58 percent for each app.

This is the textbook definition of what social scientists call a collective-action problem. It’s what happens when a group would be better off if everyone in the group took a particular action, but each actor is deterred from acting, because unless the others do the same, the personal cost outweighs the benefit. Fishermen considering limiting their catch to avoid wiping out the local fish population are caught in this same kind of trap. If no one else does it too, they just lose profit.

Cigarettes trapped individual smokers with a biological addiction. Social media has trapped an entire generation in a collective-action problem. Early app developers deliberately and knowingly exploited the psychological weaknesses and insecurities of young people to pressure them to consume a product that, upon reflection, many wish they could use less, or not at all.

8. Four Norms to Break Four Traps

Young people and their parents are stuck in at least four collective-action traps. Each is hard to escape for an individual family, but escape becomes much easier if families, schools, and communities coordinate and act together. Here are four norms that would roll back the phone-based childhood. I believe that any community that adopts all four will see substantial improvements in youth mental health within two years.

No smartphones before high school

The trap here is that each child thinks they need a smartphone because “everyone else” has one, and many parents give in because they don’t want their child to feel excluded. But if no one else had a smartphone—or even if, say, only half of the child’s sixth-grade class had one—parents would feel more comfortable providing a basic flip phone (or no phone at all). Delaying round-the-clock internet access until ninth grade (around age 14) as a national or community norm would help to protect adolescents during the very vulnerable first few years of puberty. According to a 2022 British study, these are the years when social-media use is most correlated with poor mental health. Family policies about tablets, laptops, and video-game consoles should be aligned with smartphone restrictions to prevent overuse of other screen activities.

No social media before 16

The trap here, as with smartphones, is that each adolescent feels a strong need to open accounts on TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and other platforms primarily because that’s where most of their peers are posting and gossiping. But if the majority of adolescents were not on these accounts until they were 16, families and adolescents could more easily resist the pressure to sign up. The delay would not mean that kids younger than 16 could never watch videos on TikTok or YouTube—only that they could not open accounts, give away their data, post their own content, and let algorithms get to know them and their preferences.

Phone‐free schools

Most schools claim that they ban phones, but this usually just means that students aren’t supposed to take their phone out of their pocket during class. Research shows that most students do use their phones during class time. They also use them during lunchtime, free periods, and breaks between classes––times when students could and should be interacting with their classmates face-to-face. The only way to get students’ minds off their phones during the school day is to require all students to put their phones (and other devices that can send or receive texts) into a phone locker or locked pouch at the start of the day. Schools that have gone phone-free always seem to report that it has improved the culture, making students more attentive in class and more interactive with one another. Published studies back them up.

More independence, free play, and responsibility in the real world

Many parents are afraid to give their children the level of independence and responsibility they themselves enjoyed when they were young, even though rates of homicide, drunk driving, and other physical threats to children are way down in recent decades. Part of the fear comes from the fact that parents look at each other to determine what is normal and therefore safe, and they see few examples of families acting as if a 9-year-old can be trusted to walk to a store without a chaperone. But if many parents started sending their children out to play or run errands, then the norms of what is safe and accepted would change quickly. So would ideas about what constitutes “good parenting.” And if more parents trusted their children with more responsibility––for example, by asking their kids to do more to help out, or to care for others––then the pervasive sense of uselessness now found in surveys of high-school students might begin to dissipate.

It would be a mistake to overlook this fourth norm. If parents don’t replace screen time with real-world experiences involving friends and independent activity, then banning devices will feel like deprivation, not the opening up of a world of opportunities.

The main reason why the phone-based childhood is so harmful is because it pushes aside everything else. Smartphones are experience blockers. Our ultimate goal should not be to remove screens entirely, nor should it be to return childhood to exactly the way it was in 1960. Rather, it should be to create a version of childhood and adolescence that keeps young people anchored in the real world while flourishing in the digital age.

9. What Are We Waiting For?

An essential function of government is to solve collective-action problems. Congress could solve or help solve the ones I’ve highlighted—for instance, by raising the age of “internet adulthood” to 16 and requiring tech companies to keep underage children off their sites.

In recent decades, however, Congress has not been good at addressing public concerns when the solutions would displease a powerful and deep-pocketed industry. Governors and state legislators have been much more effective, and their successes might let us evaluate how well various reforms work. But the bottom line is that to change norms, we’re going to need to do most of the work ourselves, in neighborhood groups, schools, and other communities.

There are now hundreds of organizations––most of them started by mothers who saw what smartphones had done to their children––that are working to roll back the phone-based childhood or promote a more independent, real-world childhood. (I have assembled a list of many of them.) One that I co-founded, at LetGrow.org, suggests a variety of simple programs for parents or schools, such as play club (schools keep the playground open at least one day a week before or after school, and kids sign up for phone-free, mixed-age, unstructured play as a regular weekly activity) and the Let Grow Experience (a series of homework assignments in which students––with their parents’ consent––choose something to do on their own that they’ve never done before, such as walk the dog, climb a tree, walk to a store, or cook dinner).

Parents are fed up with what childhood has become. Many are tired of having daily arguments about technologies that were designed to grab hold of their children’s attention and not let go. But the phone-based childhood is not inevitable.

The four norms I have proposed cost almost nothing to implement, they cause no clear harm to anyone, and while they could be supported by new legislation, they can be instilled even without it. We can begin implementing all of them right away, this year, especially in communities with good cooperation between schools and parents. A single memo from a principal asking parents to delay smartphones and social media, in support of the school’s effort to improve mental health by going phone free, would catalyze collective action and reset the community’s norms.

We didn’t know what we were doing in the early 2010s. Now we do. It’s time to end the phone-based childhood.

This article is adapted from Jonathan Haidt’s forthcoming book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

==>

==>

The anthem of absolution is a gentle song. Sussurant whispers through the background of your life in time with the metronome tick of the doomsday clock in your dreams, now magnified by the empty rolling plains into a proclamation of triumph. For the first time in ten years you step outside your prison, and for the first time in your nineteen years you see a blue sky.

>Frolic through the seussian fields

Yeah this is pretty great.

>Find your next victim

Your big-ass ella purnell eyes spot a lone IMP clinging to a nearby pylon.

>Aim

==>

==>

==>

==>

==>

HAMSTERSPRITE: Nice shot.

>Level up

As you reach the respectable rank of MAXFEASANCE AGENT on your ECHELADDER for your accomplishment--the value of the single BOONCOIN in your GRIFTWALLET responding appropriately with your new notoriety--it occurs to you that in your excitement, you're skipping pretty far ahead in the timeline. What, do you expect a hypothetical audience to have some preexisting framework by which they could intuit the context of your adventure or something? That would be silly.

>Rewind a bit.

No, no, too far back.

>Skip ahead.

Oh come on! Spoilers!

>Find a happy medium between past and future.

That's more like it.

Your name is QIRSMIT though you prefer to go by SMITTY to your extremely small circle of online friends. You live on the tidally locked techno-industrial powerhouse planet of LUSTRIUM, an arbitrarily large number of years in the future removed from the hypothetical audience to this internal monologue. That planet will be destroyed shortly, this you know, or at least have a pretty good hunch about.

This is because you are some kind of PROPHET, with the ability to foretell disaster derived from the strings of numbers you see in your dreams. You turn these numbers into STATISTICAL DATAPOINTS that you compare to the present performance of the Lustrium economy to predict IMMANENTLY DEPRECIATING STOCKS AND CURRENCIES with unerring accuracy.

This has been your job for your entire life, ever since your adoption by the cyborg broker hivemind known collectively as the SHAREBEARS, after you were delivered to the roof of their building by a fortuitous meteor. While not particularly personable, they are attentive to your needs and quick to indulge the many interests you pursue in your free time.

These interests include OLD EARTH MOVIES though the films the Sharebears obtain for you are more often than not related to the stock market and/or data analytics. You enjoy a well-plotted graph, but in your free time you prefer the more mystical studies of SACRED GEOMETRY and OBJECTS OF MATHEMATICAL INTRIGUE.

You enjoy building elaborate MARBLE COURSES and running races, both because it is a practical study of PHYSICS AND ENTROPY as well as very fun to see little glass balls roll down a chute. You have damn good aim with a SLINGSHOT too in case those little glass balls aren’t moving fast enough.

You have an interest in the ancient art of the JAPANESE MANGA and own rare print volumes of your favorite series. You can also amuse yourself for many hours by playing with your dear PET HAMSTER. You are also a bit of a GAMER, particularly virtual reality and simulation games as a substitute for rather limited freedom.

You used to have a lot more freedom, but as the lynchpin of the Sharebears operation there have been several attempts on your life by rival broker organizations over the years. One psychic attack nearly succeeded, resulting in a long stay on the PSYCH MOON to restore your capabilities.

==>

Now you spend your nights floating in a somnotank of PSYGEL to insulate your mind against unseen threats, and live inside a hermetically sealed reinforced glass bunker at the center of the Sharebears cavernous trading floor. The value of your abilities has provided you with a comfortable life and secure employment, you couldn’t ask for more and on Lustrium alone there are much worse ways to live.

But you often wish you didn’t feel so…bunkertrapped. dwellingenclosed. abodenfixed. There’s probably a good word for it.

>Examine Shorts poster.

SHORTS is your favorite film of all time, quite possibly the greatest film ever made. Given to you by the Sharebears after a misinformed assumption about it's content due to the title. On first watch, your eyes were opened to a world of compelling nonlinear narrative structure, the antique but timeless humor of the year 2009, and whimsical all-ages wishing-rock-related hijinks. You have watched it many times since.

==>

You dearly wish Toby “Toe” Thompson, Loogie Short, and “Nose” Noseworthy could be your friends. Helvetica Black was your first crush, and while you since question your prepubescent taste, there is something undeniably attractive about a girl with a rocket bike who can turn into a giant wasp. You assume the characters in the film are either entirely fictional, or as you have more recent reason to believe, long dead.

>Look at wishing rock.

For your fascination with the film is also a matter of predestination. When you arrived on Lustrium as a meteor-borne infant, one of the things you brought with you was a rainbow-colored rock. Pretty but unremarkable, until your first exposure to Shorts led you to the astounding discovery that your mundane trinket was the very same wishing rock from the film. There is simply no other explanation.

However, your rock does not grant wishes, you assume it’s power was either exhausted, or it is waiting for the right conditions to activate once more.

You have written up a long list of carefully-worded possible wishes in anticipation of the day it does.

From a speculative rp project with @alpha-bread and @scrambo surrounding an oc sburb session. Got bit by the homestuck artbug HARD and figured I'd compile my work thus far.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Am I a little bit late for some of you? I might be. But anyways. Here's what went right around the world this past week :)

Youth climate activists won a huge climate lawsuit

Sixteens youths (aged five to 22) from Montana, US, have emerged victorious after suing state officials for violating their right to a clean environment.

In their lawsuit, they argued that Montana's fossil fuel policies contributed to climate change, which harms their physical and mental health. Montana is a major coal producer, with large oil and gas reserves. The state has rebuffed these claims, saying that their emissions were insignificant on a global scale.

Judge Kathy Seely, in a 103-page ruling, set a legal precedent for young people’s rights to a safe climate by finding in their favour. “Every additional tonne of GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions exacerbates plaintiffs’ injuries and risks locking in irreversible climate injuries".

This win marks the very first time a US court has ruled against a government for a violation of constitutional rights based on climate change. It will now be up to Montana lawmakers to bring state policies in line.

“As fires rage in the west, fueled by fossil fuel pollution, today’s ruling in Montana is a gamechanger that marks a turning point in this generation’s efforts to save the planet from the devastating effects of human-caused climate chaos.” - Julia Olson, executive director of nonprofit law firm, Our Children’s Trust, which represented the youths in this case.

Number of Mexicans living in poverty fell by millions

Thanks to a new minimum wage boost and increases to pensions, the number of Mexicans living in poverty fell by 8.9 million between 2020-2022, according to new data published by the country’s social development agency, Coneval.

Coneval’s statistics suggest that the number of people living in extreme poverty also fell – from 10.8 million in 2020 to 9.1 million last year – although that figure is still up from a pre-Covid 8.7 million recorded in 2018.

There is still a long way to go, and some critics do claim that during the current president, López Obrador's presidency has been characterized by austerity.

An organised crime group trafficking endangered species has been jailed

The Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC), a small European wildlife charity, is apparently busting kingpins behind as much as half of the world's illegal trade in pangolin scales. The traffickers began six-year jail sentences a few weeks ago.

The wildlife charity went undercover to expose three Vietnamese and one Guinean national, members of an organised crime group trafficking body parts of endangered species including rhinos.

They were arrested in May 2022, following a four-year investigation by the WJC, and were accused of trafficking 7.1 tonnes of pangolin scales, as well as 850kg of ivory. Last month they pleaded guilty to smuggling and were jailed for six years.

All eight species of pangolin are listed as threatened animals, four critically endangered - they are protected by international law.

“There has not been a reported seizure of pangolin scales in Asia originating from Africa in more than 550 days,” said Steve Carmody, WJC’s director of programmes. “There is no clearer example of the importance of disrupting organised crime networks.”

AI gave conservationists a breakthrough

The use of AI-controlled microphones and cameras seems set to revolutionise

biodiversity monitoring in the UK following groundbreaking work by researchers at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). They used the tech to record and analyse 3,000 hours of wildlife audio captured by monitors located near London railway lines.

The computers detected dozens of bird species, foxes, deer, bats and hedgehogs, and mapped their locations.

It’s hoped the innovation will help improve conservation and habitat management on Network Rail land.

This year is best ever for UK renewable energy installations

This years looks to be the best year so far for UK renewable energy installations, with record numbers of households fitting solar panels and heat pumps.

2023 marks the first time solar panel installations have topped an average of 20,000 a month, as homeowners look to harvest energy from the sun amid rising utility bills.

Read the full story here.

The UK’s Tree of the Year shortlist was revealed

The Woodland Trust has announced the shortlist for its annual celebration of some of the UK’s most treasured ancient trees, and for 2023 the spotlight is on the urban landscape.

“Ancient trees in towns and cities are vital for the health of nature, people and planet,” said the charity’s lead campaigner Naomi Tilley. “They give thousands of urban wildlife species essential life support, boost the UK’s biodiversity and bring countless health and wellbeing benefits to communities.”

Article published August 17, 2023

Thank you so much for reading! Let me know what interested you, and if there's any specific topic you'd like me to dig into, my DM's are always open :)

Much love!

#climate change#climate#hope#good news#more to come#climate emergency#news#climate justice#hopeful#positive news

115 notes

·

View notes

Text