#ingvaeones

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

I have a world in which a lot of words, majority being nouns are never actually translated and thus languages all have common and unaltered loan words. What I mean is like 'chocolate' is always 'chocolate', there's no 'chocolat' 'coklat' 'cokolada' etc... To make it easier, all languages do have a similar alphabet. If this continues on a vast scale, how do languages develop and how understandable are different languages?

Tex: What is your base language? Why is it not another language?

To illustrate a point, here is the etymology of the word chocolate (Wikipedia):

Cocoa, pronounced by the Olmecs as kakawa,[5] dates to 1000 BC or earlier.[5] The word "chocolate" entered the English language from Spanish in about 1600.[6] The word entered Spanish from the word chocolātl in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. The origin of the Nahuatl word is uncertain, as it does not appear in any early Nahuatl source, where the word for chocolate drink is cacahuatl, "cocoa water". It is possible that the Spaniards coined the word (perhaps in order to avoid caca, a vulgar Spanish word for "faeces") by combining the Yucatec Mayan word chocol, "hot", with the Nahuatl word atl, "water".[7] A widely cited proposal is that the derives from unattested xocolatl meaning "bitter drink" is unsupported; the change from x- to ch- is unexplained, as is the -l-. Another proposed etymology derives it from the word chicolatl, meaning "beaten drink", which may derive from the word for the frothing stick, chicoli.[8] Other scholars reject all these proposals, considering the origin of first element of the name to be unknown.[9] The term "chocolatier", for a chocolate confection maker, is attested from 1888.[10]

To illustrate another point, here is an excerpt for the article on the history of the English language (Wikipedia):

English is a West Germanic language that originated from Ingvaeonic languages brought to Britain in the mid-5th to 7th centuries AD by Anglo-Saxon migrants from what is now northwest Germany, southern Denmark and the Netherlands. The Anglo-Saxons settled in the British Isles from the mid-5th century and came to dominate the bulk of southern Great Britain. Their language originated as a group of Ingvaeonic languages which were spoken by the settlers in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages, displacing the Celtic languages (and, possibly, British Latin) that had previously been dominant. Old English reflected the varied origins of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms established in different parts of Britain. The Late West Saxon dialect eventually became dominant. A significant subsequent influence on the shaping of Old English came from contact with the North Germanic languages spoken by the Scandinavian Vikings who conquered and colonized parts of Britain during the 8th and 9th centuries, which led to much lexical borrowing and grammatical simplification. The Anglian dialects had a greater influence on Middle English.

Linguistics is a large, old, and complex subject. It has a lot of overlap with other sciences, and there are always new things being found out about it. Below is a list of links to help introduce the depth and breadth of languages and their development:

Further Reading

Linguistics (Wikipedia)

Global language system (Wikipedia)

Integrational linguistics (Wikipedia)

Language geography (Wikipedia)

Dialect continuum (Wikipedia)

Sprachbund (Wikipedia)

Writing system (Wikipedia)

List of creators of writing systems (Wikipedia)

Ebonwing: If your world’s languages evolved and changed in a broadly similar way than ours did (independently all over the world, resulting in a great deal of linguistic diversity) this is unrealistic. Pronunciation naturally changes as languages evolve over time; English wasn’t always pronounced the way it is today, either. As a result, a word loaned from another language isn’t going to sound the same way a few hundred years later.

Plus, loan word pronunciation changes are also driven by languages having different phonology from the source language. Japanese loaned chokoretto from chocolate, but it’s really not pronounced the same way. Sometimes even the meanings change in the process; in German, a Handy (loaned from English) is actually a mobile phone.

Of course, if you’re not going for an Earth-like linguistic background, you have more leeway in doing things like this.

Utuabzu: Something you should consider when dealing with multiple languages is that every language has its own phonology - set of sounds - and phonotactics - rules about how sounds can be combined - and these can differ significantly. These differences become particularly clear with loan words, as speakers will alter the word to fit their language’s rules and available sounds, eg: Hawaiian alters Christmas to kalikimaka, because it doesn’t have the sounds ‘r’, ‘s’ or ‘t’ and doesn’t allow consonants to follow consonants or to end a syllable.

This doesn’t even account for the problems of trying to use a single script for all languages. Different languages have different rules about what sounds are distinct enough to differentiate words. For instance, English has a relatively limited number of vowels, but other Germanic languages have more, which they write using additional letters, eg. å, ä, æ, â, ø, ö, ü, etc. Some languages, like Icelandic, even have additional consonant letters - þ and ð - because it’s necessary to clearly distinguish those sounds. Then there are languages that aren’t generally written with roman script, like Hindi, which needs to clearly distinguish aspirated consonants, or Chinese languages, which need to account for lexical tone*. If you want a script that can depict all the many, many possible sounds of human language, you’re going to end up with something like the International Phonetic Alphabet, which is far too unwieldy to be used to write any single language, and even linguists don’t generally use unless they’re describing the sounds of a language. Especially because most languages will consider multiple sounds to be equivalent and interchangeable that IPA uses distinct characters for, because different languages will lump together different sets of sounds and usually omit many of them entirely. (Eg, Standard English dialects lack the voiced glottal fricative

Much of the time, it’s just going to be easier to use a purpose-made script that can actually depict the language accurately, and even when that doesn’t happen, the borrowed script is likely to be altered and evolve over time to accommodate the needs of its users. Roman, Greek, Cyrillic, Arabic, Hebrew, Armenian, Georgian and the vast Brahmic family of scripts are all derived from a common ancestor, Proto-Canaanite, and have mutated and evolved over the course of 3500 years to suit the languages that use them.

This further complicates loan words, as they then need to be altered for the script, because not all scripts have equivalent characters, eg Japanese hiragana ら is most often realised as /ɾa/ or /la/ which to English speakers sounds like ‘ra’ or ‘la’, but to Japanese speakers are considered the same sound.

A further complication also comes from grammar, as many languages have rules that alter words based on their role in a sentence or the surrounding words. A common way to do this is with morphemes - units of language that have independent meaning but cannot appear on their own, eg. suffixes and prefixes (together with infixes, which get shoved inside the root, and circumfixes, which get split and tacked either side of the root, these are called affixes) like ‘-s’, ‘-ed’, ‘re-’, ‘pro-’, ‘anti-’, etc. - these are attached to the root, the base word, to convey additional information.

Agglutinative languages (like Finnish or Inuktitut) add multiple affixes to indicate case and number of nominals,, while fusional languages (like German or Russian) use one affix to express both. Polysynthetic languages (like Algonquian languages) frequently and extensively alter both to convey a lot of information. Other languages, most famously Welsh, alter the sound of a word based on the words immediately around them (mutation).

All these factors are going to make what you want here really difficult to achieve. If you are determined to have this, you probably need all the languages in your world to have a relatively recent common ancestor that had a well established literary standard and standardised orthography. By recent I mean very recent. The Romance languages have been diverging for over 2000 years (Cicero was complaining about the Sardinian dialect of Vulgar Latin in the 1st Century BCE), while the entire Indo-European language family - containing languages from Icelandic to Sinhala and the first languages of approximately 46% of the global population - is estimated to have been diverging for about 6000-10,000 years, depending on the theory. Our species, Homo sapiens, is over 300,000 years old, so this isn’t very long in comparison.

*lexical tone is one of two main tone systems, the other being prosodic tone. Lexical tone means that individual words have a tone that impacts their semantic meaning, while prosodic tone is carried across multiple words and conveys pragmatic meaning. This difference is why native speakers of lexical tone languages (like Mandarin or Zapotecan languages) can often sound oddly flat when speaking prosodic tone languages (like English). The roman alphabet was not created to deal with lexical tone and Vietnamese gives an excellent example of how much it needs to be altered to depict tones.

Blue: Natural languages change for so many different reasons; some of the big contributing factors are technological and cultural changes. The farther apart they are geographically, the harder it is to maintain the homogeneity. One would think that the advance of modern technology, such as the internet, would smooth out the differences, but it does not appear to be the case (see Wikipedia’s article on ELF)

Language has a socioeconomic, cultural, and religious (e.g.: sacred language) significance. It can be a status symbol: French was adopted at various courts across Europe and became the distinguishing feature of aristocracy. People are often very reluctant to part with their native language, because it means giving up a part of their identity. If it's an artificial language imposed on different communities, why would they accept it and refuse their own language? If this situation developed naturally, how did it happen?

Lingua franca – "common language". Some of the historical examples are Akkadian, Koine Greek, and Latin; more recent ones are English, French, and Arabic. The spread of linguae francae is often associated with the colonial efforts to establish the language of the colonizer as the primary language of communication, but it is not always so: Tupi (Brazil) and Classical Maori (New Zealand) were adopted by the colonizing population. A lot of linguae francae were adopted and stayed dominant to facilitate trade most and foremost.

Due to the cultural and economic hegemony, English is arguably the lingua franca of the world. One of the reasons why English is the dominant language of international communication is the expansion of the British Empire. In Russia, lingua franca is (obviously) Russian, but there are many native languages across the country that are officially recognized and taught at schools in their respective regions; Russian also serves as a lingua franca in many post-Soviet countries. In the Americas, there are obviously native languages that are very far removed from English and Spanish. In all these examples, native languages are used alongside the common languages: the lexicon and grammar of the native languages perseveres.

There is also such a thing as an auxiliary language - the kind of language that's been artificially constructed to aid communication internationally (esperanto) or for a more limited group (Interslavic). Esperanto is the only one that is relatively well-known and widely used; none of auxiliary languages have ever become widely spread though. That might change one day, but then the question becomes: will they stay the same across the globe, or will they also see regional changes?

It's theoretically possible for a language to exist in a time capsule if it's used by a small isolated community that doesn't see much change; but even then, there's a possibility of phonetic shifts over the years.

Let's for a second imagine that it did happen to a degree, but only with nouns.

Here we run into another issue that would hinder understanding: a lot of human languages view verbs rather than nouns as a central feature of a sentence. On a larger scale, verbs convey the relationships between nouns and actions you perform with an object: “I ate chocolate” and “I bought chocolate” are two very different things, and just knowing the word "chocolate" tells you nothing about the meaning of the sentence in general.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

English is a West Germanic language that originated from Ingvaeonic languages brought to Britain in the mid-5th to 7th centuries AD by Anglo-Saxon migrants from what is now northwest Germany, southern Denmark and the Netherlands.

In other words,English is a European language. American languages are The Indigenous languages of the Americas are the languages that were used by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas before the arrival of non-Indigenous peoples. Over a thousand of these languages are still used today

The most widely spoken Indigenous languages are Southern Quechua (spoken primarily in southern Peru and Bolivia) and Guarani (centered in Paraguay, where it shares national language status with Spanish), with perhaps six or seven million speakers apiece (including many of European descent in the case of Guarani). Only half a dozen others have more than a million speakers; these are Aymara of Bolivia and Nahuatl of Mexico, with almost two million each; the Mayan languages Kekchi, Quiché, and Yucatec of Guatemala and Mexico, with about 1 million apiece; and perhaps one or two additional Quechuan languages in Peru and Ecuador. In the United States, 372,000 people reported speaking an Indigenous language at home in the 2010 census. In Canada, 133,000 people reported speaking an Indigenous language at home in the 2011 census. In Greenland, about 90% of the population speaks Greenlandic, the most widely spoken Eskaleut language.

#kemetic dreams#brownskin#brown skin#asians#asian#native american#native#native girls#nativebaddiez#nativeamericans#nativebigtitt#ndn#native women#navajo#first nations#indigenous#nahuatl#indigenous languages#Kekchi#Aymara#Eskaleut#Yucatec

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Proto-Indo-European(s): *vibe with their reflexive pronouns*

Ingvaeonic B: Nah, we're losing the third person ones

Old English: *sigh* okay...

Middle English: what if I just... his + self... hisself?

Modern English: himself :) herself :) themself :) themselves :)

Ingvaeonic B:

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comparison of Garish Dialects

The Word Nine

Standard: nön [nøːn] Altaug: nön [neːn] Southern: neoin [neu̯n] Dane: njø [njøː] Ingvaeonic: nuin [nœi̯n] Middle (central): neoin [nʲe̯øi̯nʲ]

The Word Bread

Standard: bråd [brɒːt] Altaug: bråd [brɔ(ː)t] Southern: braud [bɹˠɑu̯t] Dane: brœd [bʀœːð̞] Ingvaeonic: brood [broːt] Middle (central): braud [bɹˠɑɔ̯tˠ]

The Word Here

Standard: hêr [heɨ̯~hɘ̟ː] Altaug: hêr [ɦɘ̟ː] Southern: heer [(ɦ)ei̯ᵊɹʲ] Dane: hér [heɐ̯] Ingvaeonic: hier [hiːr] Middle (central): heer [çeːɹʲ]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

the dutchposting is entertaining but dutch is also imo interesting as being near the far end of a not-quite-continuum with high german at the opposite end. ofc because of the ingvaeonic/istvaeonic/irminonic split it's not quite that smooth of a transition between them but still, it's nearly just a few isoglosses over (including the german consonant shifts) from what's spoken in switzerland. also you all would enjoy west frisian i think.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Image IDs: slide contents 1: etymologically speaking; or, how to completely change the way you talk to match the original meanings of words. caption: so due to some posts i saw earlier today and my general saltiness levels i decided to share a powerpoint on this topic that i made a couple of years ago please enjoy.

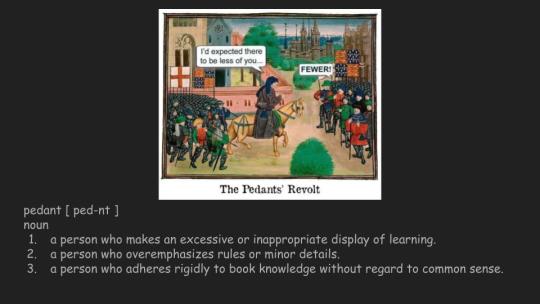

[slide contents 2: pedant [ ped-nt ] - noun -a person who makes an excessive or inappropriate display of learning. a person who overemphasizes rules or minor details. a person who adheres rigidly to book knowledge without regard to common sense. caption: do you know any pedants? i know some pedants. [obi-wan of course i know him.jpg.]

slide contents 3: decimate!!

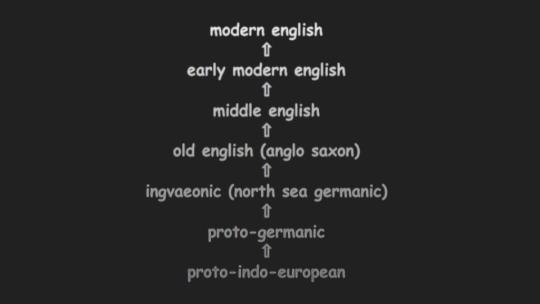

slide contents 4: a flow chart showing the evolution of english from proto-indo-european to proto-germanic to ingvaeonic (north sea germanic) to old english (anglo saxon) to midde english to early modern english and finally to modern english. caption: so the question is how far back this grand tradition goes. 'cause, you know, every language comes from an origin in other, older languages spoken by the people who came before us. it takes about 1000 years for a language to evolve into something that modern speakers can’t understand. that’s why anglo-saxon, which began to shift into middle english in 1100 BCE, and from middle to early modern english by 1500, is fully impossible for us to comprehend. chaucer, from the 1400s, is difficult to read, and some people even have trouble with what’s considered fully modern english as written by the constitutional framers in the 1770s. caption: we all know that pedant who says that ‘decimate’ really means to kill off one tenth, or that you can’t use the word ‘literally’ figuratively. i think if we are going to be pedants we should go whole-hog with it.

slide contents 5: Gramer þe grounde of al · bigyleth now children - For is none of þis newe clerkes · who-so nymeth hede - Þat can versifye faire · ne formalich enditen - Ne nouȝt on amonge an hundreth · þat an auctour can construe - Ne rede a lettre in any langage · but in latyn or in englissh — William Langland. caption: pedantry, is, of course, a long-standing tradition among scholars throughout history. take this quote from William Langland from the 1300s. this is full of words that have shifted meaning and/or spelling since the 1300s, although langland WAS writing in english, SO we actually need a translation to understand it.

slide contents 6: churl comes from the old english ‘ceorl’ "peasant, one of the lowest class of freemen, man without rank," which evolved to early middle english "man of the common people". caption: the modern meaning of churl is a rude, boorish, or surly person, or someone who is stingy.

slide contents 7: girl derives from an unrecorded old english word that later became ‘gyrle’ c. 1300 with the meaning "child, young person" of either sex. caption: now, we all know what a girl is. but this means in our new way of speaking english, girl is the perfect gender-neutral term we’ve all been looking for! we should immediately start calling every young child a girl. i see no way in which this could go wrong.

slide contents 8: meat is from middle english mēte, descended from old english mete "food, nourishment, sustenance," also "a meal, a repast". caption: so originally, a picture of meat would be more like this. vegetables were called grene-mete until the 15 century; dairy products similarly referred to as whyte-mete. what we now refer to as meat today would have been known as flesh-mete or simply bread. yes, bread.

slide contents 9: awful comes to us circa 1300 ‘agheful’ "worthy of respect or fear, striking with awe” or “profoundly reverential”, caption: originally a synonym of the word awesome, which has retained this sense to this day. one might think the fact that this word’s meaning has shifted so far is simply awful.

slide contents 10: nice is from the late 13c., "foolish, ignorant, frivolous, senseless". caption: nice is a word that’s shifted a lot from its meaning in the 1300s, many times, to the point where researchers sometimes don’t know what meaning someone writing in the 1700s or 1800s was even going for. so that’s nice.

slide contents 11: silly changed meaning often but could mean "pitiable" (late 13c.), "weak" (c. 1300), and "feeble in mind, lacking in reason, foolish" (1500s). caption: so you might think begging on the street is a silly way to try to make money, but under this definition it’s literally completely silly.

slide contents 12: slut is circa 1400, "a dirty, slovenly, or untidy woman" or in other words, a slob. caption: the word slut did not shift meaning from its 1400s meaning until the 1960s, which is the strongest case I know for one of these entries to go back to what it originally meant.

slide contents 13: the scene so far: the nice girl sat down with his father, the churl, and ate some bread that consisted of flesh-metes and whyte-metes. it was absolutely awful. the girl’s mother, a silly slut from saskatchewan, was actually a real giglot.

caption: what, you're telling me you don’t know what a giglot is?

caption: giglot: "lewd, wanton woman" (mid-14c.). End IDs.]

i made this presentation a couple of years ago for a comedy slide presentation event. my presentation was the most educational of the bunch and i think everyone felt betrayed.

#etymology#language#linguistics#english#powerpoint#i try to be funny#mine#it took me 45 minutes to realize i'd forgotten to caption the slides please forgive me#it should all be there now#marti made this

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philology

Dear Caroline:

I really love this philological snippet of yours, all the more so as it rhymes with some of my own inclinations, and even if as most of your early posts, it is a borrowing from somebody else's tumblr. While preparing the civil service exams for language teaching, the units I was most hoping to have to write about were the literature ones or those about culture and history, including the diachronic evolution of English: the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law, medieval latin borrowings, i-umlaut and palatalization (as in cheese), the borrowings from French and their reinforcement after king Henry's marriage to Eleanor de Provence and his munificence to his Poitevin half-brothers... A veritable linguistic Leviathan, so well chronicled in Baugh and Cable's A History of the English Language, which is sitting right next to me at the moment of typing these lines.

And not only English! You reference Finnish here, a language notorious for its non-Indo-European background. Many years ago, I took a summer course in Estonia for the purpose of studying the local speech -it must have been around 2007-, spending a month in the old university city of Tartu with the only company of a very worn and reread edition of Milton's Paradise Lost, which is my favorite epic poem ever. And the local lingo was a treasure trove of curiosities, with very melodious vowels and no less than fourteen grammatical cases(nominative, genitive, partitive, illative, inessive, elative, allative, adesive, ablative, translative, terminative, essive, abessive, and comitative). But this is stuff that a competitor in the Linguistic Olympiads like yourself does not need reminding of.

On another linguistic tangent, it would be nice to know your take on the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Myself, I tend to be quite Chomskian, but more of a function of my biases than anything else - a universalist view of language pairs well with a universalist view of the human race and its capacities and basic thought mechanisms.

A couple of weeks from now will be Estonia's Mother Tongue Day, whose date coincides on purpose with poet Kristian Jaak Peterson's birthday. Some verses of his celebrating his native speech will serve as the quote for today.

Quote:

Kas siis selle maa keel

Laulutuules ei või

Taevani tõustes üles

Igavikku omale otsida?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Languages Closely Related To English (Ingvaeonic Languages)

“Woah! Dude! New fact! Languages x and y are basically mutually intelligible! Sometimes, speakers of language x who live close to country y understand language y more than speakers of language x who live far away! Sometimes, if you whisper language x in the middle of the night, speakers of language y will cry in their sleep out of sheer intelligible-ness!”

I’m preeeetty certain that you recognize the kind of post I’m talking about. Whether it’s the Nordic languages (it’s usually the Nordic languages) or some other group of tight-knit languages, people are fascinated with mutual intelligibility between two languages not-quite similar enough to be dialects.

When these kinds of posts or memes or whatever may have you circulate, I see plenty of people wonder about English. Some are curious if English-speakers get any similar international clout, while others are under the false assumption that there is nothing that closely related to English, save for a directly ripped French phrase or two.

This post is brought to you by my heart going out to both kinds of people. Fear not, English speakers! We have hope! I bring to you the Ingvaeonic/“North Sea” branch of Germanic languages, where you can find English. While I can’t guarantee that you can go out right now and have a conversation with a Low German speaker the same way recalled in tales by Norwegians who have ran into a peculiar Swede in a Swedish-Norwegian border town, you’re still looking at English’s closest cousins, and there is a lot of fun to be had in that.

Have you ever heard of “Scottish English”? Maybe you’ve seen an odd Scottish tweet or two in a bizarre dialect that you can somehow perfectly understand yet can’t understand at all? That would be the language of Scots, the closest distinct relative to English. Scots and English separated relatively recently, all things considered, and it is the main place you will find such shenanigans from the viewpoint of an English speaker. It’s so close to English that some argue that it’s just a dialect with its own distinct culture and identity, but I’ll let you in on a linguistic secret: when you get down to it, a dialect with its own identity is all a language is.

The Frisian languages and the Low German dialects aren’t as intelligible to English as Scots, but are still quite interesting if you like the topic. If you’re the kind of nerd that compares languages for fun, it’s a pretty neat experience compare and contrast them to English.

———————————————————————

NOTES:

• Dead languages and the various fringe minority dialects are not featured in this graphic. There are a few I wanted to feature, but I had to hold myself back in the name of simplicity.

• As stated above, this is an introduction, and was made with simplicity in mind. If you take up extensive research on the topic expect many “Oh, that’s HELLA complex” moments to come your way. This is especially the case for Low German, which is a beast of confusion.

• If you’re interested in this topic and how it relates to English, I’d definitely do some research into German and Dutch. While they aren’t AS closely related to English as the languages above, they’re both still Germanic languages, and have quite a lot in common with English. If you ever need a laugh, set your smartphone’s system language to Dutch and google the German name for birth control pills.

———————————————————————

Anyways, I hope this post has offered you some form of dopamine and look forward to making more of them! Spreading this post around if you enjoyed it (or maybe if you didn’t, I’m not here to judge) would be greatly appreciated. Also, if I slipped up on something, please feel free to tell me. I am by no means perfect or a main authority on this subject or any I choose to cover in the future.

#Article#OC#linguistics#language learning#languages#language#germanic languages#germanic language learning#English#Scots#Frisian langaugss#Low German#Old English#Ingvaeonic languahes#Germanic#something something shilling with tags

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Frey

Frey is the Germanic God of harvest, peace and fertility. He's the twin brother of Freya and possibly the most loved God of all the Germanic deities, which makes sense considering that the harvest and fertility were one the most important aspects of Germanic life in peace time. Judging by his character and attributes, he could also be one of the oldest Germanic deities.

Frey is being described as part of the Vanir tribe. He owns a ship, Skidbladnir, which has the ability of being able to fold up so that it could be carried inside a pocket. He is often depicted with his boar, Gullinbursti, who has a golden mane and can run faster through air and water than any horse. Further more he is often depicted with a huge phallus, which symbolizes his fertility, and a sword.

The meaning of his name is incredibly similar to his twin sister's name. Both Frey and Freya are titles rather than personal names. As I have explained in an earlier post, Freya means 'lady', the same seems to be true for Frey. Frey literally means 'lord', the word is derived from the Proto-Germanic 'Frawan' which means lord. The actual true name of Frey is therefore uncertain but we have a very likely theory.

Several archeological finds, written sources, still existing traditions and place names have been discovered that have a link to this deity. There is also a theory that might explain Frey's actual name. Yngvi is the name often linked to Frey and might actually be a much older name to describe this deity than Frey is. But why? Frey is a name, or rather a title, that seemed to have been used in the early medieval ages, especially during the viking age. The name Yngvi however has been mentioned by Tacitus back in 98AD.

Tacitus described a region which belonged to the Ingvaeonic people, Ingvaeones can be translated into 'son of Yngvi'. The Ingvaonic people are said to have been descended from Yngvi who in turn was a son of Mannus, Mannus himself was a son of Tuisto, better known as Tyr the oldest deity of the Germanic pantheon and former chief God. This theory might actually be the only, pre-viking, attempt in making a family tree of the Germanic Gods. It gives us an interesting insight in the ancestral tree of the Gods before the medieval ages. The modern day Ingvaeonic offspring are: the Dutch, North-west Germans and the Danish people.

Another source linking the name Yngvi with Frey comes from the Ynglinga saga written by Snorri Sturluson. In this tale, that tries to legitimize the reign of old Norse kings by linking them to Frey, Frey is being mentioned as Yngvi-Frey. If Yngvi is really the true name of Frey, that means the Inguz rune is bound to him. There are also many modern day names in the Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Frisian, old English, Norse and Incelandic language that are linked to Yngvi, per example 'Inge' and 'Ingrid'.

The old English Runic poem, written somewhere during either the 8th or 9th century, contains a stanza about Inguz which seems to confirm the link between Yngvi and Frey:

"Ing wæs ærest mid Eástdenum gesewen secgum, oð he síððan eást ofer wæg gewát. wæn æfter ran. þus Heardingas þone hæle nemdon."

"Ing was first among the East Danes so seen, until he went east over the sea. His car followed. Thus the Haerdingen called that hero."

Here he is also described as 'first of the Danes' just like Tacitus had done many centuries before this poem was written down.

Most of our written and archeological sources however come from medieval Scandinavia. Adam of Bremen, a German chronicler from the 11th century, has written down several Scandinavian pagan practices and mentioned the God Frey with his Latinized name 'Fricco':

"In this temple, entirely decked out in gold, the people worship the statues of three gods in such wise that the mightiest of them, Thor, occupies a throne in the middle of the chamber, Woden and Fricco have places on either side. The significance of these gods is as follows: Thor, they say, presides over the air, which governs the thunder and lightning, the winds and rains, fair weather and crops. The other, Woden that is, the Furious—carries on war and imparts to man strength against his enemies. The third is Fricco, who bestows peace and pleasure on mortals. His likeness, too, they fashion with an immense phallus." - Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis

A statue of Frey has also been found in Södermanland, Sweden in 1904. This statue has been dated back to around the year 1000 and is made entirely out of bronze. The statue is about 7 centimeters tall and depicts Frey with a beard, hat and an erect penis. Interestingly enough, ancient wooden statues have been found inside bogs, in both Denmark and the Netherlands, that depict a figure with an erect penis. These statues date back to the bronze age and might perhaps be the earliest representations of Frey.

Unfortunately we do not exactly know how the ancient Germanic people worshiped Frey. There are several theories based on present day traditions and historical research, by comparing Frey with other fertility deities. One of these theories, based on the fact that Frey is almost always depicted with an erect penis, is that Frey might been linked to certain unknown sex rites. It is of course completely unknown what these rites would have been like, perhaps by singing? Adam of Bremen mentioned in his work that certain raunchy songs were sung in temples.

Another theory, which might date back to the Proto-indo European culture, is that the people might have honoured or sacrificed a horse's phallus. Another, perhaps the most wildest theory, concerns the description made by Ibn Fadlan, a 10th century muslim traveler who witnessed a bizare ritual surrounding a burial. According to his words, a slave girl that was sacrificed, was first put through several sexual rites, it is unknown if it was basically a rape or part of an ancient ritual, perhaps a ritual based on the worship of Frey.

There is still at least one existing tradition that can possibly be linked to Frey. This tradition, which I have practiced myself as well, is practiced in the Netherlands right after harvest. According to the tradition, the last piece of harvest is left behind on the field and made into a doll figure to thank Frey for the succesful harvest and blessing the land for next year's harvest.

Frey certainly is a fascinating deity and we still have much to learn about him and the history behind the people who worshiped him.

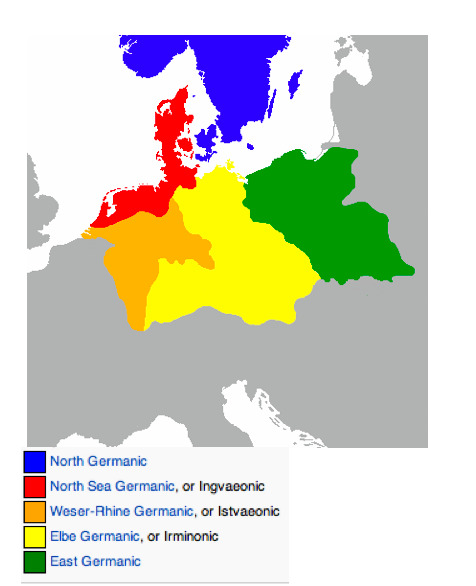

Here are images of: Frey by Johannes Gehrts, Swedish Frey statue, Danish bog statue of a possible ancient depiction of Frey, A map showing the Ingvaeonic people in red, A Dutch harvest doll,

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Languages of the world

West Frisian (Westerlauwersk Frysk)

Basic facts

Number of native speakers: 470,000

Official language: Friesland (Netherlands)

Language of diaspora: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United States

Script: Latin, 26 letters

Grammatical cases: 0

Linguistic typology: fusional, SVO

Language family: Indo-European, Germanic, West Germanic, Ingvaeonic, Anglo-Frisian, Frisian, West Frisian languages

Number of dialects: 3

History

9th century - earliest written examples

12th-16th centuries - Old Frisian

1498 - replacement of West Frisian by Dutch as language of government

16th-19th centuries - Middle Frisian

>19th century - New Frisian

Writing system and pronunciation

These are the letters that make up the alphabet: a b c d e f g h i y j k l m n o p q r s t u v w z.

-A-, -e-, -o-, and -u- may have acute or circumflex accents.

Grammar

Nouns have two genders (common and neuter), two numbers (singular and plural), and no cases. All plural and common singular nouns take the same definite article.

Unlike nouns, personal pronouns have three genders. Some adpositions are inflected.

Verbs are conjugated for tense, mood (indicative and imperative), person, and number. There are only two inflected tenses, present and past. The rest of them are formed using auxiliary and modal verbs.

Dialects

There are three dialects: Clay Frisian, Wood Frisian, and South Frisian. All of them are mutually intelligible, but have some phonological and lexical differences.

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

Apparently old English is so similar to German and Dutch (or is it Frisian?!).

Frisian, I believe. If I recall rightly Old English and Old Frisian share a much more recent ancestor than they do with German and Dutch, along with Old Saxon. According to wikipedia they were part of a group of languages called the North Sea Germanic or Ingvaeonic.

#i think this might have been in my inbox for a while i'm sorry#old english#frisian#langblr#language blog

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

o neporiadku a zmätku

Dnes sa mi na chvíľu zazdalo, že som niekde úplne inde. Na ceste do práce. Veziem sa Južnou triedou a vonku je zima, počujem ako sa dve ženy bavia a cenách bytov, nájomoch a večnej nezamestnanosti. Ale dnes bolo v skutočnosti horúco, blúzka sa mi lepila na pokožku a v električke bolo počuť len tiché nezrozumiteľné rozhovory. Pocity ma premáhajú ozaj často. Chcem byť sama a zároveň chcem byť s ľuďmi s ktorými byť nemôžem, lebo sú ďaleko. Je mi strašne smutno a hrozne ťažko sa všetko vysvetľuje. Hľadám, kde sa veci začínajú a kde končia a čo má a nemá zmysel. Ako vyjadriť čo viem, chcem a môžem a čo by som nemala. Ako ľahko sa žije v abstraktnosti, kde je v poriadku mať vo veciach zmätok. Na múriku oproti obchodu s ochrannými odevmi fajčím a pri mne leží DVD “Ako funguje svet?” Prezerám si staré poznámky v mobile.

13.3. (14:06)

Gevoelens van ongemak

17.1. (16:07)

Pochodzę ze wschodniej Słowacji

17.5. (16:33)

Dni sú pridlhé a inokedy krátke. Najradšej sedávam na záhradke medzi dvoma fakultnými budovami, cez ktorú prechádza málo ľud�� - niekedy dokonca nikto. Absorbujem chvíľkové ticho v rušnom, rozbitom, hučiacom, kričiacom a plačúcom meste. Cítim pominuteľnosť svojej prítomnosti tu. Viem, že to nie je zďaleka čo chcem, po čom túžím, ale momentálne sa musím koncentrovať na to aby som kládla jednu nohu pred druhú a pomaly sa prebojovala ať k poslednej cigarete v medzizáhradke.

22.2. (12:12)

Nebude tu vícekrát být

10.6. (22:00)

Wymysorys has traditionally been classified as a member of the Irminonic family: Standard German, Yiddish and Silesian German. Istvaeonic which includes Dutch, Flemish and Afrikaans, Ingvaeonic languages, to which English, Scots, Low German and Frisian belong.

6.6. (17:26)

čo je to za frašku vyjebanú kokotinu

20.3. (12:39)

how can I do this, how. Nothing makes sense. Latvian literature doesn’t make sense. People in blue shirts don’t make sense. It’s warm, it’s cold. Everything hurts, my fingers hurt, my back hurts, everything is so painful and confusing.

25.6. (15:45)

Ik zeg altijd 'portemonnee'.

11.4. (14:38)

minä rakastan sinua

niinkuin vierasta maata

kallioita ja siltaa

niinkuin yksinäistä iltaa joka tuoksuu kirjoilta

minä kävelen sinua kohti maailmassa

ilmakehien alla

kahden valon välistä

minun ajatukseni joka on veistetty ja sinua

(Pentti Saarikosken kokoelmasta Mitä tapahtuu todella?)

_________________

ako

funguje

svet

?

všetko sa mení

mení

mení

a ostáva

rovnaké

rovnaké

stále

také

isté

1 note

·

View note

Text

I have applied the methodology behind the grouping of the Papuan languages to the languages of Eurasia, and made several exciting discoveries.

The largest subgroup of Mitian is Finno-Hindustani, spanning from eastern Europe to the Indian subcontinent and the easternmost reaches of Siberia. The pronouns of Proto-Finno-Hindustani are approximately *mænV *θɨ *(jæ)çoɲ, and 1PL *mɘd. In Finnish and Nganasan, the *-nə element of the 1SG has been extended to the 2SG; this may also explain the Assamese and Hindi forms. (There may be other, secondary pronouns in these languages, of course; but many are underdocumented, and short word lists with pronouns are all we have to go on.) In the Albano-Kamchatkan genus of Finno-Hindustani, however, the 1SG has been prefixed with *ɣ(ɘ)-, perhaps related to Anglo-Frisian *ig, which on occasion (Albanian /unə/, Hungarian /e:n/, Greek /eɣo/) resulted in a form *ɣænV with loss of the initial *m-. In Chukchi and Itelmen, however, the *-m- was retained.

Almost as large as Finno-Hindustani is Pashto-Tsakonian, characterized by the pronominal proto-forms *æz *tɨ *ɣiʑ, the 1PL *men-ʂ- (possibly derived from the Pre-Proto-Finno-Hindustani form, or possibly reformed along the lines of the lost 1SG), and the oblique forms 2SG *tæβe and 3SG *nə-ɣu- and *nə-ɣa- for the masculine and feminine respectively. These gender markers were not extended into the plural except in Lithuanian and Latvian, where they evidently conditioned umlaut.

Turko-Icelandic is likely shallower than either of these two; with the exception of Welsh, an almost full set of pronouns may be reconstructed: 1SG *wjeŋ, 2SG *tu, 3SG *θan (with *θ preserved as t- only in Mongolian, and debuccalized to *h- > h-/0- elsewhere, including in the otherwise highly archaic Welsh), 1PL *vitn, 2PL *tætən (with the distinction between *-Cn and *-Cən reflected only in Kalmyk, Mongolian, and Norwegian, and lost in Faroese, Icelandic, Turkish, and Welsh), and 3PL *toirnar (with *r-n > /nl/ in Turkish and perhaps dissimilatory loss of *t-; an alternative, of course, is to instead connect Turkish /onlar/ to Welsh /n̥u/).

The Romance and Ingvaeonic languages are upheld by this method, with the important exception of Sardinian, likely an isolate within Mitian unless the third-person /isse/ is to be connected to Proto-Finno-Hindustani *(jæ)çoɲ. It is likely, however, that this is a retention; forms like it are preserved everywhere in Mitian except for the clearly innovative third-person forms of Romance and Greek.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freyr may be the progenitor of the Ingvaeones tribe (from which I descend), but his sister, Freyja, is so much cooler

If the old ways call for ancestor worship, then it means I should be worshipping Freyr. But Freyja’s so much cooler!

I mean, if she’s his sister then that makes her like my aunt or something. So I guess that’s neat...

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, originally spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England.[3][4][5] It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated from Anglia, a peninsula on the Baltic Sea (not to be confused with East Anglia in England), to the area of Great Britain later named after them: England. The closest living relatives of English include Scots, followed by the Low Saxon and Frisian languages. While English is genealogically West Germanic, its vocabulary is also distinctively influenced by Old Norman French and Latin, as well as by Old Norse (a North Germanic language).[6][7][8] Speakers of English are called Anglophones.

The earliest forms of English, collectively known as Old English, evolved from a group of West Germanic (Ingvaeonic) dialects brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the 5th century and further mutated by Norse-speaking Viking settlers starting in the 8th and 9th centuries. Middle English began in the late 11th century after the Norman conquest of England, when considerable French (especially Old Norman) and Latin-derived vocabulary was incorporated into English over some three hundred years.[9][10] Early Modern English began in the late 15th century with the start of the Great Vowel Shift and the Renaissance trend of borrowing further Latin and Greek words and roots into English, concurrent with the introduction of the printing press to London. This era notably culminated in the King James Bible and plays of William Shakespeare.[11][12]

Modern English has spread around the world since the 17th century as a consequence of the worldwide influence of the British Empire and the United States of America. Through all types of printed and electronic media of these countries, English has become the leading language of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and professional contexts such as science, navigation and law.[3] Modern English grammar is the result of a gradual change from a typical Indo-European dependent-marking pattern, with a rich inflectional morphology and relatively free word order, to a mostly analytic pattern with little inflection, and a fairly fixed subject–verb–object word order.[13] Modern English relies more on auxiliary verbs and word order for the expression of complex tenses, aspect and mood, as well as passive constructions, interrogatives and some negation.

English is the most spoken language in the world (if Chinese is divided into variants)[14] and the third-most spoken native language in the world, after Standard Chinese and Spanish.[15] It is the most widely learned second language and is either the official language or one of the official languages in 59 sovereign states. There are more people who have learned English as a second language than there are native speakers. As of 2005, it was estimated that there were over 2 billion speakers of English.[16] English is the majority native language in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand (see Anglosphere) and the Republic of Ireland, and is widely spoken in some areas of the Caribbean, Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia and Oceania.[17] It is a co-official language of the United Nations, the European Union and many other world and regional international organisations. It is the most widely spoken Germanic language, accounting for at least 70% of speakers of this Indo-European branch. There is much variability among the many accents and dialects of English used in different countries and regions in terms of phonetics and phonology, and sometimes also vocabulary, idioms, grammar, and spelling, but it does not typically prevent understanding by speakers of other dialects and accents, although mutual unintelligibility can occur at extreme ends of the dialect continuum.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_language

0 notes

Photo

A Year in Language, Day 15: AAVE (African American Vernacular English)

AAVE, also known as Black English, Blaccent, or, with some controversy, Ebonics, is a leaf of the American English twig of the Ingvaeonic stem of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family.

AAVE was first formally studied in the late 60's and 70's to prove a rather strange point: that AAVE was a language. I would love to be able to talk about how people ~used~ to think about the speech of black Americans, but the frank truth is people still very much maintain the idea that black speech is "ungrammatical", "slang" and a result of poor education. What linguists demonstratively proved, what frankly any decent human being already knew, was that AAVE is a true language with consistent grammatical rules.

There are many theories about AAVE being influenced by the West African languages of slaves or a child of the creole languages of the southeast and Caribbean. However this is likely untrue, or at most a minimal influence. AAVE is most similar to archaic forms of Southern English and is probably a sister dialect. The two share many phonological features, like "monopthongal ai" (pronouncing "nice white rice" like "nahs waht rahs") and also unique lexical entries like "fixing to" also spelled "finna" meaning "going to, about to".

What little forms of conjugation persist in English, like the third person -s (ex. I run, he runs) are dropped in AAVE. It also exhibits zero-copula, where the copula i.e. word that equates two things (ex. the word "are" in "dogs are great") can be dropped, hence white English "who is that?" vs. AAVE "who that?". Hebrew is also a zero-copula language. AAVE has a pretty robust system of verb tense and aspect, consider "he workin", "he been workin" "he be workin" "he done work" "he do work" "he done been workin" are all distinct placements of one mans action of working in time, and that these are consistent and identifiable verbal constructions.

It should not come as a shock that I chose this language on MLK day. I feel like I've made it very clear that the speech of black Americans, and frankly the dialectical speech of all Americans, is as much a language as any other tongue. Now I'd like to make certain we understand the ramifications of this knowledge. AAVE is NOT a sign of poor education or poor socialization, and the fact that you cannot speak it in formal settings, that no newscasters speak it on tv, that no nature documentary is narrated in it, is a facet of racism and nothing else. While not all black Americans speak AAVE, most do, especially those from primarily black communities. All of them will be basically forced by our society to learn a second language, specifically the language of white Americans, in order to be taken seriously. 2018 is still young, and I ask everyone, especially white people, reading this to go into the rest of this year with an additional resolution: Stop acting like AAVE is lesser, or more comical. When you see a friend or celebrity typing in their native tongue don't make jokes about how you "can't understand" or can't take them seriously like that. Admire how much subtle meaning can be implied with just a slight change in word choice or order. Marvel that "fuck with" has an entirely different meaning in AAVE not found in white dialects. Stop being a racist pedant.

409 notes

·

View notes