#in favour of maglor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

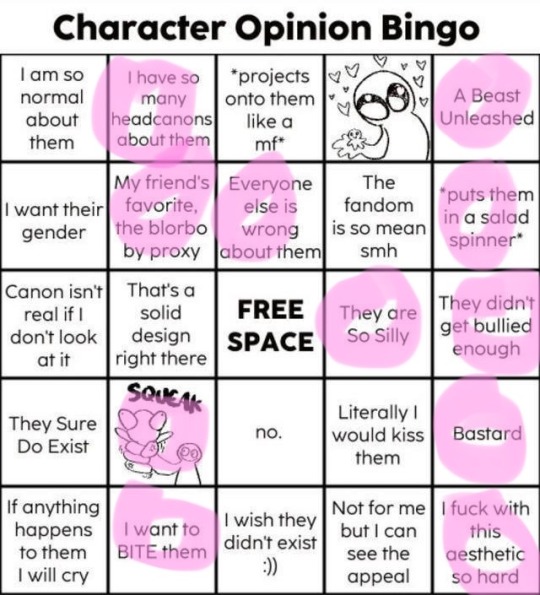

Maglor for the character bingo? - Sauroff

where is the fandom isn’t mean enough?

(the ‘beast��� is the bastard in battle btw. bc i do think he could rip reality to shreds with his voice.)

tragedy enjoyers like no he doesn’t get to live happily in rivendell now

also i think his best traits ultimately caused his downfall and isn’t that what we’re looking for in tragedies?

thank you! 🧡

#honestly he’s one of the characters that the fandom can make me hate#if i’m not careful and don’t filter things out#especially in the ways that elrond and elros#show connections to their full heritage#so if ppl want to make them reject elwing and earendil#in favour of maglor#who they didn’t even like right away#i get very irritated#also for the love of god#study child development#before you write about children#especially wartime traumatised children#but this is me being irritated still at comments i sometimes get#and my general distaste#for ppl in the silmarillion fandom#assuming fanon is canon#maglor seems disproportionally viewed this way#like sorry he still killed civilians#which most likely included children#let’s talk about how the fear of eternal damnation and darkness#drives actions in life#and what that says about tolkien’s catholicism#because that is interesting to me#character bingo#maglor#tolkien#silmarillion#jr2t#silm#sauroff

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maglor, a ghost, as I try to teach myself how to do it more "painterly."

#maglor#kanafinwe makalaüre#the silmarillion#one of our favoured genuses of magloriana: the beachglor#silmarillion art#artists on tumblr#my art#my silm#ive been feeling very sad and so im endulging on the healing properties of blorbodrawing#not this one. this is from a while ago and I think I have gotten better at painting like this like... between this one and the maemags week#painting i posted theres only a couple of months of studies and i feel like the difference is there!#its the same brush and everything

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 17 - featuring Conversations and also Scheming!

Just as the Elves of Himring rush to the aid of their beleaguered companions, the Sun rises.

Between the appearance of the detested light and the sudden attack, the orcs are taken by surprise, beaten back towards the north.

Fingon cuts a swathe through them until he reaches Maedhros' side at the base of the hill.

"We have to stop meeting like this," he says.

Maedhros' answering smile is more radiant than the Silmaril in his pocket.

It falters a little, though, when he catches sight of Curufin behind Fingon.

But he is used to keeping a cool head on the battlefield, and apprises Fingon of the situation swiftly and efficiently.

“We have been hard-pressed,” he says, “but we can turn the tide now, with your help. My King.”

His mouth curling a little mischievously, the sunlight picking out the shades of gold and chestnut in his red hair, the black viscera clinging to his sword: I love him, thinks Fingon, I love him.

How could anyone ever knowingly hurt him?

He keeps his own assessment of the battle to himself, for now, and says only, “No doubt!”

When he lifts his sword the soldiers rally to him – rally, he observes, as they did not to Maedhros – and the orcs retreat further.

They will be back again by nightfall, emboldened by the darkness, but for now they have a little breathing space at least.

There is plenty to discuss – now that Maedhros’ own captains are actually returned to him they are long overdue a council of war – but Fingon finds time, as they traipse back into the fortress, to pull Curufin aside and set the tip of his sword to his cousin’s throat.

“What was it your father said?” he asks. “This is sharper than thy tongue? I will not hesitate to turn it on you should you come near him. You have done enough damage already. Understood?”

“Understood,” Curufin says hoarsely, and Fingon backs away. His eyes are very cold and very bright.

Curufin is getting kind of used to death threats tbh. Maedhros put a knife to his throat as well.

Speaking of which, Maedhros seems unnervingly stable right now. The brother he left behind was not in any way capable of running Himring’s defences.

Curufin isn’t welcome in Maedhros’ war-council, and he can’t even fight that well with his burned right hand.

He goes in search of Maglor instead.

Maglor is expecting Maedhros when the door pushes open – a good thing because seeing Maedhros comforts him, and because he needs to hold the Silmaril again, but also a bad thing because he will invariably have to talk Maedhros down from the edge of panic.

His voice is very sharp, then, when he sees Curufin and says, “Ah, Curvo. You have rather a lot to explain.”

Curufin also has plenty of questions, but his mouth is at first too dry to ask them.

Maglor is so, so pale.

“I,” Curufin says, and stops.

Maglor is very angry, but he is also too tired to maintain his anger for long. “Why did you do it?” he asks, more quietly.

There are furious tears beginning to sting at Curufin’s eyes. He blinks them away and says, “I wish – I wish you had died and he had lived—”

Maglor understands this sentiment, awful as it is. How many times, during the long years of Maedhros’ captivity, did he wish that it had been any of his other brothers who were lost instead – anyone but Maedhros whom he loved best?

For a moment his instinct is to be gentle. But then he thinks of Maedhros standing just where Curufin is now, staring at Maglor with the bleak terrified look of an enemy – no, not an enemy, not anything so equitable as that – the look of an ill-used thrall.

“I still might,” he says, and twitches aside his coverlet to show Curufin the ugly, unhealed stab wound in his side.

Curufin draws in a breath. “How—?”

“Nelyo stabbed me,” says Maglor. It is the first time he has spoken the words aloud. They hurt more than he expected. “He thought – he thought I was an illusion, a trick of the Enemy. Because someone had told him I was dead.”

(Easier to turn all his anger onto its rightful target, to focus on the reasons why it happened and not the fact that it did – he is not angry with Maedhros, how could he ever be angry with Maedhros? This is Curufin’s fault.)

Curufin feels sick. “I didn’t—”

“How could you, Curvo?” Maglor asks, voice now barely above a whisper. “It was so cruel.”

“I didn’t mean for this,” says Curufin. “I just—” He closes his eyes; Maglor’s expression is hard to look at.

Focus. He has questions. “Where’s the other Silmaril? It might help—”

“That’s what you care about?” Maglor demands, instantly on the defensive. He doesn’t want to be reminded of his own failures. “Thingol has it. Isn’t that why you marched off to Doriath with most of our people?”

Curufin should have known Fingon was lying to him.

It might be a teensy bit hypocritical if he complains about that now.

“Go away, Curvo,” Maglor says wearily. “I am not in the mood for this.”

“I’m sorry,” Curufin manages, but his brother doesn’t respond.

Meanwhile Fingon and Maedhros have managed to put together some sort of battle plan [which I am not going to describe but it involves Manoeuvres and maybe also Tactics].

Now that the first delirious gladness of reunion is past Fingon can see that Maedhros does not look very well. He’s clearly stressed, and the people who stayed behind in Himring keep casting suspicious looks his way.

When the council is over and it is just the two of them left to take their private greetings of each other, Fingon takes Maedhros’ face between his hands and looks at him carefully, trying to read the story of all he must have suffered lately in his shadowed eyes and sharp cheekbones.

When Fingon kisses him, Maedhros sighs into his mouth as though he has not been able to breathe until this very moment.

“I missed you,” Fingon murmurs as they break apart.

“I thought,” says Maedhros, but he does not want to talk about what he thought, does not want to do anything but lean into the steady warmth of Fingon’s embrace.

But there is always work to be done, and so after a time he says, “Tell me what you really think, then.”

“About the battle?” Of course Maedhros didn’t miss Fingon’s reluctance to voice his own opinions during the council. But it is harder to lie now. “Russo, you cannot hold.”

Maedhros closes his eyes briefly. “I have to,” he says. “Now that my own captains are here – and you—”

(It is still hard to believe that anything could ever go wrong with Fingon, all shining faith in the face of impossible odds, beside him.)

“It will not be enough,” Fingon says gently, tracing small circles on Maedhros’ cheek with his thumb. “There are so many of them, and they have come so close. You will have to call a retreat sooner or later.”

It pains him to say it. Himring is the last bastion of the Noldor in the East, the last Fëanorian stronghold. All Maedhros’ fierce unwavering spirit is woven into these chilly stones.

Maedhros gives him a despairing look. “I can’t,” he says. “It’s Káno. He isn’t well, and I can’t put him through a retreat.”

“Then send him away now,” Fingon suggests, “he managed our last journey well enough.”

“He won’t go,” says Maedhros.

Fëanorians! thinks Fingon.

This does, at least, seem like a simple problem with a clear solution, so he goes to visit Maglor and inform him that he is being unreasonable.

Maglor, who after all has a penchant for Dramatic Reveals, stops his scolding in its tracks by once again tossing aside his coverlet to show Fingon his stab wound, although explaining where he got it is less fun.

Fingon lets out a string of curses. “He doesn’t know?”

“No,” says Maglor emphatically, “and he is never going to find out.”

"Well," Fingon says. He sits down on Maglor's bed, shocked.

Maglor manages a sideways smile. "Shall you miss me when I'm dead, cousin?"

"Don't say that," Fingon protests. "You might still – you might—"

"After all your hard work rescuing me from Menegroth, as well," says Maglor. He gives Fingon's arm a little squeeze.

"This is absurd," Fingon says firmly. "You aren't going to die. Russo can give you the Silmaril back, for a start. That helped before. And we can send you somewhere safer—" But it is now perilously obvious that Maglor's refusal to leave was not for any sentimental reasons, but merely that he is far too weak to travel. "We'll work it out, Makalaurë."

"Finno," Maglor murmurs, "at some point you will have to learn that you cannot save everyone."

Fingon makes a distressed sound and Maglor changes the subject. "You sorted things out with Thingol, at least. How did you convince him we posed no threat?"

Fingon glances at him and then gives in, perhaps rather selfishly, to the impulse to unburden himself. "I promised him Curufin's head," he says.

Maglor is quiet for a while. At last he says, "Are you going to do it?"

"I don't know," Fingon says. "I was so angry when I said it! How he could be so cruel to Russo – and I gave Thingol my word—"

"Curvo and Nelyo don't know," says Maglor. It isn't really a question, but Fingon shakes his head anyway.

Maglor thinks for a little while and then says, "If I die – no, listen to me – if I die, you can't do it." And when Fingon gives him a look, "Please. You didn't... you didn't see what Nelyo was like. He won't be able to – not after Tyelko too. Not both of us, please, Finno. My death or Curvo's, but not both."

"Makalaurë," Fingon says, dismayed.

"Promise me," Maglor insists.

"Fine," says Fingon, "I promise."

He can't deny it is a relief to have a loophole on the execution thing. This isn't how he wanted to find it, though.

But Maglor is smiling faintly. He falls back against the pillows, his burst of animating energy gone.

That doesn't mean you can deliberately refuse to get better for Curufin's sake, Fingon wants to say, but it's hard to phrase that in a non-absurd way. Instead he says, "Russo loves you, you know."

"I know," says Maglor, sounding tired.

Meanwhile Maedhros has been busy catching an orc.

(Most of them sleep during the day, but this one was stupid and/or hungry enough to slip away from its commanders.)

Fingon comes down to the dungeons to watch the interrogation, which Maedhros, as is his habit, carries out personally.

At first he speaks to the orc in Sindarin, but when it proves recalcitrant he switches to one of the orc-tongues instead.

Fingon is pretty sure he should not find the sound of his beloved speaking the harsh, guttural mockery of a language as sexy as he does. Whatever.

Maedhros asks it a sharp question or two and the orc, clearly startled to hear its language from an elf, answers sullenly.

Then Maedhros draws out the Silmaril and asks the orc another question as it flinches away from the light. He smiles, rather viciously.

(How fair his face in the light! But he was no less lovely in the darkness.)

"Put it to death," he tells one of the guards – in Quenya, which orcs do not, as a rule, understand.

Is it kinder this way, Fingon wonders? Is it better to keep the orc ignorant of its fate?

That is so not the point right now.

When he and Maedhros have come out again into the sunlit courtyard, Maedhros says, "As I thought. Morgoth wants the Silmaril back: every orc has been tasked with seizing it."

"Stupid on multiple levels," Fingon observes; "they won't be able to hold it, and they're far more likely to run off with it than bring it to Angband."

Maedhros smiles. "They'll be able to hold it if they capture its bearer instead," he says, eyes rather distant.

"Well, that settles it," Fingon says firmly. "You are not carrying that thing onto the field again. Leave it with Maglor." He pauses, and then adds, "It'll help him heal, too."

Maedhros agrees instantly; he has been worrying about Maglor all day.

If only all Fingon's problems could be dealt with so easily.

"Remember what I said," he warns, slipping his hand into Maedhros' as they enter a more secluded part of the fortress. "Himring will not hold forever, Russo."

"It need not hold forever," Maedhros murmurs. "Only until—" He breaks off and bites his lip.

Until Maglor is healed enough to manage a retreat, he means. But that feels far too selfish to say aloud.

He has always known he will put his own concerns before those of his people; that is why he gave the crown to Fingolfin long ago, after all.

It is quite another thing to see it put into practice, to weigh Maglor's life against all his followers' and find it is indisputably the heavier.

Fingon, meanwhile, is wondering whether Maglor will even outlast Himring.

Curufin holds his breath as they pass the little alcove where he is sitting; but, absorbed in the conversation and each other, they walk by without noticing him.

Maedhros still hasn't spoken to him since his return. Curufin isn't sure if he wants him to.

He comes to a decision.

(to be continued)

the fairest stars, continued

The "Beren and Lúthien steal two Silmarils" AU that has spiralled completely out of my control: time for a new post again! Parts 1-9 are here and Parts 10-15 here. Also now slowly being uploaded to AO3 here, though you still want tumblr for the latest version.

To recap:

Maedhros and Maglor are in Himring.

Maedhros has (somewhat, a bit, with caveats) recovered from his very bad unreality attack, and is now attempting to defend Himring from an army of orcs. Unfortunately 90% of his people aren't there.

Maglor has very much not recovered from being stabbed by Maedhros, and is not really in a great situation.

Fingon is busy trying to stop Curufin's war with Doriath. He's kind of managing to talk Thingol down from attacking Himring's assembled army.

Although his bright idea for accomplishing this was offering to execute Curufin.

Maedhros holds one Silmaril in Himring, Thingol has kept one in Menegroth, and the last one is still in Angband.

Dead characters who are nonetheless still in the story: Lúthien, Beren, Finrod, Celegorm.

When Maedhros' mother named him well-made, she was not picturing his prowess on a battlefield: but Maedhros was forged anew in the crucible of Angband, or perhaps more gently in his long months of healing by Mithrim's shores, and this is what he is good for, now.

And he is very good at war.

Under his command the defence of Himring rallies. Maedhros sets the few archers he has to rain down arrows on the arrows on the attacking orcs, and takes a small party out on horseback to drive them further back, and the fortress gains a little breathing space.

But there is only so much he can do with so few people – and people, at that, who are so strangely slow to respond to his command.

Not that they will disobey him openly, but he is far too aware of their suspicious eyes on his back, the wave of mutters that breaks every time he issues an order.

"And the way they look at me – as if I'm, as if I'm one of the Enemy's thralls – do you think—?"

"Nelyo," Maglor says instantly, "you are not a thrall."

Maedhros attempts to stop his frenetic pacing up and down Maglor's room. "Then why," he says. There is so much noise in his head. He cannot seem to finish the sentence.

"They're Curvo's people," says Maglor, and there is something hard and unfamiliar in his voice as he speaks their brother's name. "Who can say what poison he's fed them?"

That was the wrong thing to say. Maedhros blanches for a moment, draws in a sharp breath, and then says, "Curvo told me – he told me—"

"I know," Maglor says, reaching out a hand. "I know, and he lied. Come here."

Maedhros clutches at his hand. Maglor can feel his frantic, fluttering pulse beneath his fingers.

Maedhros can feel Maglor's, faint and irregular.

He tries to steady his breathing. Tries not to sort through the jumble of memories pressing against his skull (they're dead, they're both dead) and focuses on the present.

Maglor is here, alive, alive – although his pallor has worsened every time Maedhros can snatch a moment from the siege to visit him, and his grip on Maedhros' Silmaril is white-knuckled, and some nameless fear touches Maedhros as he looks at him.

"Should I send you away, dearest?" he asks.

Maglor's eyes widen. "What?"

"It isn't safe here," Maedhros explains, although he has little heart for his suggestion in the face of Maglor's obvious dismay. "If Himring does fall – I don't wish to put you through a hard retreat."

"Don't make me leave you," Maglor begs, his voice teetering on the edge of real distress. "I want – I want to stay here, and—"

"All right," Maedhros soothes. "All right. You can stay as long as I hold."

"You'll hold, Nelyo," Maglor says. "You always do."

In the face of this unwavering confidence Maedhros manages to summon a shaky smile.

When he is gone – and the sustaining warmth of the Silmaril with him – Maglor reviews his objectives, which are threefold.

One: stay alive. Not going very well tbh. He has not recovered from the blood loss. And more than that the world feels grey and cold to his eyes – he who has always loved sunrises – and he cannot stop remembering: the splintered haunted look in Maedhros' eyes, the way, before Maglor sang him to sleep, he was reaching for the knife to try again.

Two: make sure Himring doesn't fall. He cannot quite believe it will, while Maedhros is in command, but the news about the recalcitrance of the few soldiers they have is concerning. He should have realised that rumour would spread through the castle after Maedhros was found in a pool of Maglor's blood, should have blackmailed Curufin's lieutenant into keeping her mouth shut about it – but too late now. Hopefully Maedhros can rally them.

Three: keep Maedhros generally sane, and specifically unaware that he stabbed Maglor. Also not going too well. Maedhros is growing stressed and paranoid. He's noticed that Maglor is healing very slowly (or not at all, to be more accurate). And – as today's incident shows – he will remember, sooner or later.

A dire situation all round, Maglor concludes, and he is not sure how much longer he will have the energy to attempt to handle it.

Where's Fingon when you need him?

Exactly where he should be, actually!

Fingon is mostly succeeding in his objectives.

The Sindar have stood down.

(Thingol agreed to his terms. That’s what matters, right? Not the vague flash of disgust in his eyes.)

“Are we going back to Himring?” Curufin wants to know. “They’re in danger.”

I have to kill you, Fingon thinks, and says aloud, “Yes, we are. But if you’re lying to me again, Curufin…”

He lets the threat trail off.

Anyway. More pressing concerns for now.

He sets a hard pace back through Himlad, reasoning that even if Curufin is lying there won’t be any harm done in getting back to Himring quicker.

Curufin has been trying to make contact with Maglor again, but his brother’s mind is closed – worrying.

All he gathered from Maglor’s brief use of ósanwë was the scent of blood and panic, the sound of orc-horns in the distance and a terrible pain in his side.

Has Maglor been injured in battle? Surely not; his leg can’t be mended enough for him to fight yet. But then what’s wrong with him?

Curufin definitely isn’t going to try touching Maedhros’ mind, considering the state Maedhros was in when he left Himring.

This is such a mess. And it’s all his fault. And Celegorm is still dead.

Be better, Fingon told Curufin – but now he won’t even look at Curufin, and Curufin’s hand is still burned and he doesn’t think it will ever heal.

Does he even want it to?

Back at Himring, Maedhros watches as the orcs press closer. If they manage to surround the great hill completely—

[look I know nothing about military stuff. in lieu of any actual manoeuvres or strategies we are going to assume that the Bad Thing that needs to be prevented is the fortress being encircled. got it? cool.]

“Harass them from both flanks,” he orders. “Keep them contained, don’t let them spread out.”

His paltry force obeys, but with plenty of murmuring.

The patrols, Maedhros catches, and His own brother.

He doesn’t know what they mean. He doesn’t know how much longer he can possibly hold. He doesn’t know where Fingon is, or whether he’s succeeded at preventing a war with Doriath, or why Maglor isn’t getting better.

When there is nothing left but the clamour in his head and his racing pulse, there is still war, at least: still the swift brutal swing of his sword though orc-neck after orc-neck, the splatter of black blood against his breastplate and the deadly dance of the battle-field.

(Still the gentle light of the Silmaril in his pocket. Still Maglor, breathing. But those are harder to hold on to.)

Himring will not fall. Himring must not fall.

As the weary battle for the fortress continues, its chronicle is woven by steady, skilful hands in the House of Vairë.

Míriel Therindë’s grandson has little difficulty finding her tapestries in the Halls of Mandos.

He is staring at them in transfixed horror when he feels a presence behind him.

“Oh. It’s you. What are you doing here?”

“Same as you, I imagine,” says Finrod, coming to sit beside him (metaphorically. since spirits can’t really sit. you know the drill). “Looking at the tapestries.”

Celegorm snorts impatiently. In life he had a tendency, when frustrated, to slip into the language and mannerisms of whatever bird or beast he felt most appropriate to the situation – elves are simply too stupid to talk to being the clear implication.

Finrod is absurdly pleased to find out this is still the case.

Or maybe it isn’t absurd, he tells himself, maybe it’s natural to want to believe that this is still the cousin he grew up with, that a person can betray you and turn your kingdom against you and still have some parts worth saving.

“I meant,” Celegorm is saying derisively, “what are you doing in these Halls? I thought your dear cousin won you a special boon.”

“Impressive you can still speak of her, after what you did,” observes Finrod. “But yes, Mandos did tell me I was to be re-embodied. First of all the Exiles, you know.”

“And?” Celegorm presses, after he is silent for a time.

Finrod smiles at him. “I told him thanks, but no thanks,” he says.

Celegorm splutters for a bit. “What?” he manages at last. “Ingoldo, have you lost your mind? How – why – is this all out of some misguided form of pity? Or are you just flinging it in my face that you can choose to leave and I can’t?”

“Lúthien reminded me,” Finrod says seriously, “that we always have a choice.”

Back in Himring, Maedhros is being pressed hard.

They are so badly outnumbered, and the orcs keep coming and coming, a never-ending river.

If Himring falls, Maglor dies – for there is no chance of his surviving a hurried retreat, Maedhros can see that even without fully understanding what ails his brother, and he has refused to be sent away in advance.

Himring can’t fall, Maedhros tells himself.

(To evil end shall all things turn that they begin well – how those words echoed in his ears four hundred years ago, as he watched his high stone fortress built. He realises, now, that he always expected Himring to fall.)

The orcs have pushed them back to the south of the hill, almost closing off the circle, cutting off their last path of retreat.

Will he burn with the house, then – like Amrod, like his father? The prospect would not be so awful were it not for Maglor.

Nothing lasts forever; Maedhros understands that as few other elves do, and has done since Angband.

But Maglor – Maglor has to live forever – Maglor is dying—

To the south-west sounds a clear silver horn, the horn of Fingolfin.

(to be continued)

#silmarillion#my fic#bullet point fic#the fairest stars#fingon#maedhros#maglor#curufin#russingon#<- do you know how long it's been since I could tag them!!#in which a battle is going on but we ignore it in favour of dramatic conversations#curufin finds out about the consequences of his actions#and maglor concocts a new scheme#also I couldn't work an m&m interaction into this one which makes me deeply Upset :(

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok a lil hc for why Curufin is so close to Fëanor and why the twins went to Beleriand.

So idk how many of you have seen twin pregnancies, and no doubt many of you will know more than me. But the ones I have seen were *exhausting* for the mother. Constantly tired, unable to do a whole lot, usually in some kind of pain be it back, ribs from the kicking babies, legs, hips, you name it. Not to mention the nausea. Nerdanel would have been absolutely shattered for most of her pregnancy, but by this point Fëanor is confident enough (has been reassured by Nerdanel over the last five pregnancies) that he’s ok leaving her to her own devices.

What this means though is Nerdanel doesn’t have a lot of energy to spare looking after her other children. Caranthir is old enough to happily stick with his brothers or sit with his embroidery, but little Curvo is around 5/6 equivalent and is very attached to his parents. Nerdanel suddenly not being able to do much creates a distance, neither of their faults, in which Fëanor steps in. This time spent with his father shapes Curufin’s interests and personality to make him embody his mother name. Atarinkë indeed, in more than just looks.

Now this temporary distance that should’ve started to close by the time Ambarussa were two or three is furthered because now is when Fëanor and Nerdanel start getting into arguments. At this point they’re small spats at most, nothing too serious, but Curufin who’s very attached to his now primary caregiver and distanced from the other, immediately takes Fëanor’s side. Again at this point both parents are still trying to get him close to his mother again, but it’s not going well and with how heated both parents get, it’s difficult to keep disagreements behind closed doors.

Then Curvo becomes a teen and it’s his father above all else. The time for change is passing, Fëanor and Nerdanel have started to spend days apart, days in which Maedhros and Maglor often take care of the twins so their mother can have a break, and Curufin sees this as another sign his mother isn’t worthy of their family. By the time we get to the banishment to Formenos, Curvo refuses to speak to Nerdanel, and whilst his brothers still send letters and occasionally go out to meet her, he burns the letters as soon as they come.

On a side note, the twins end up very very close to their oldest brothers because of this. It’s why they decide to go to Beleriand: their brothers, their primary caregivers, are all going. So they are too. They don’t know their mother well enough to stay.

Disclaimer: I adore Nerdanel and think she’s absolutely brilliant. You have to have some guts to not only marry Fëanaro Curufinwë, but then stick to your guns and refuse to follow him. And successfully wrangle seven very skilled, very opinionated sons. She’s the best and was no doubt an amazing mother, but the way things turned out just didn’t work in anyone’s favour.

Also to still be known as ‘the wise’ after marrying Fëanor and everything he did? Insane.

Fëanor was also a great father ok. At least until Morgoth really got in his head towards the end of their time in Aman. There’s a reason all his kids followed him to Beleriand.

#nerdanel#feanor#feanaro curufinwe#fëanorians#house of feanor#curufin#Curufinwë#atarinke#Maedhros#Maglor#Celegorm#Caranthir#Amrod#Amras#ambarussa#nerdanel the wise#silmarillion#tolkien#silm#silm headcanons

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

i hate posting discourse it's pointless and doesn't do anything for me except prolong my annoyance but i'm Tired™ and feel like shouting into the void. apologies to my beautiful feanorian mutuals please look away i love u

i neeeeeeed everyone to stop claiming they like elwing if their characterisation of her is completely made-up biased bullshit that paints her as an immature and disdained ruler (?????) who couldn't balance her responsibilities with the husband she married too young (at 22. practically a child bride honestly) and the children she never wanted (where. where does it say this). she's clearly such a bad mother that she abandoned them at first opportunity (she knew the feanorians were more than capable of killing a pair of twin boys because they literally already did that. that's very much a thing that already happened. to her brothers) and it was her selfish nature that made her soooo eager to flee (she had no reason to think ulmo would save her it was literally a suicide attempt. she wanted to make sure the deaths of her people and presumed deaths of her sons weren't in vain by ensuring they never obtained the silmaril)

like i'm gonna touch your hand as i say this. it's okay if you hate her! just don't pretend that you weren't thriving in the 2016 era of silm fandom where everyone pushed all their male fave's negative traits onto any other woman in a 5 mile radius to grab Poor Little Meow Meow status for war criminal #1 #2 and #3 to then turn around and spout the exact same (factually untrue) sexist rhetoric concealed under seven layers of buzzwords just because it's the year of "unlikable and complicated female characters" like buddy who are we talking about here. have you perhaps considered making an oc?

and i'm NOT saying i want the whole fandom to mimic my exact opinions and thoughts about elwing i realise that one of the best parts of the silm is how divisive it is and how you have so much wiggle room to come to your own interpretations because of how VAGUE the source material is but i'm genuinely convinced everyone's just parroting shit they saw in ao3 fanfics where maglor is secretly lindir and the premise is elrond sneaking him into valinor and elwing yells at him for slaughtering her people. TWICE. and this is framed as a category 5 Woman Moment so elrond disowns her and calls maglor his real dad

(eärendil misses this entire ordeal because he went on a voyage to save the world that one time and no one's let him live it down since because the whole fandom as a collective decided he did this because he's a terrible dad and not because the whole continent was at war and about to be wiped out and maybe he came to the unfortunate but reasonable conclusion that leaving is the best thing he could do for his family if it meant there was a chance his sons could grow up safe in a world that wasn't ruled by Fucking Satan so now his whole Beloved Sacrificial Lion: The Thin Line Between Doomed and Prophesized Hero™ shtick is tossed out in favour of.... *checks notes* Guy Who Forgot To Pay Child Support? oh and they're a lot louder about this because he's a man so no one can call it misogyny that's why no one ever goes the #girlflop #ILoveMyBlorbosNastyAndComplicated route with him and he gets dubbed as that one asshole who just wanted fame and glory even though that goes against the general themes for tolkien's hero characters. and tolkien loved that dude to bits that was his specialist little guy so you can't seriously tell me you think that's what he was trying to portray???????? is that seriously what you think he was trying to portray????????? babe????????????

also there's a BIG difference when it's a character that's only named in one draft and doesn't exist in the rest or gil-galad who has like three and a half possible fathers but ELWING??????? the only possible way you could be coming to these conclusions is if you read the damn book with your eyes closed. FUCK.

#im clicking post and then never opening my mouth about it again#i got all i needed to say out in one solid swing that's good enough for me. pacifism restored 👍#anti feanorians#<- which im not but i genuinely dont want to shit stir#elwing#earendil#silm#mine

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maglor in the Third Age:

he's stopped his shtick of only keeping to the seashores sometime in the early second age

look, it's lonely. also, probably a waste of time and everything. he's not fixing anything that way.

so, by the third age, he's just travelling here and there... as often as not, it is the coastal regions of middle-earth, but, ultimately, he goes pretty much everywhere.

sometimes he gets some money by playing at inns and doing odd jobs for mortals. he's gotten used to making an illusion of not having glowy amanyar eyes, because it makes the non-numenorean peoples take interest, and the gondorians and arnorians know

he just keeps adopting children? it's not his fault!

he doesn't steal children anymore. unless they're mistreated. let's just say he may be starting off many changeling myths (though not only him; elves in general will always approach a child they see treated badly and ask if it needs help)

a lot of those kids (from a hundred different cultures) just go a-wandering with him? half of them end up as the greatest musicians among men. but he drops the ones that want to off at rivendell.

elrond knows it's maglor. he also hardly ever gets to see him because maglor is stealthy.

mmm, if there are any places he avoids it's the elvish realms.

and yet, he does come to rivendell in secret, once in a while. and even pays a suprise visit to galadriel.

galadriel has last spoken to him at the mereth aderthad. yes, she's mad. no, she won't miss an occasion to speak with old kin in the language of her youth.

he does not go to mirkwood. ever. that would be suicide, and he is good at reassuring himself that he's doing the mirkwood elves a favour by not giving them flashbacks and not making them kinslayers.

all in all, he travels around.

he definitely is part of many "resistance movements" against sauron in the South whenever things get bad

there's probably some resentment there because it's easy enough to mistake him for someone of númenorean descent ? (that noldorin appearance + the only answer he gives when asked his age is "older than I look")

he probably replies to accusations of gondorian affiliation by "I'm a far off relation but I'm pretty sure I'd be hated there"?

that works I guess. somehow "villainous character from stories of the elder days" isn't a potential reason they come up with, unlike say, helping the people gondor would colonise.

though he's a bit wrong on that count because a fair bit of learned gondor sees him as mostly tragic

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where 👏 is 👏 Finrod!

Where 👏 is 👏 Finrod!

Where 👏 is 👏 Finrod!

This is: Ardavision 😎

#i am irrationally in his favour#anyway canonically daeron is best right?#although this might just be the famous anti-fëanorian bias of elrond's library#i will vote maglor to spite tolkien#and because of my spite toward anything lay-of-leithian-related#tolkien

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diplomatic Concerns. (russingon, on ao3).

When they did at last come together, it did not feel like an inevitability to Maedhros. Far easier it was to believe - to contrive - ways in which they might betray themselves, and allow their understanding to betray their people.

This, they both agreed, could not be permitted. Maedhros would have loved Fingon less, if he had been willing to brave the storm of opposition and defiance their open courtship would cause.

His people had cause, just cause to stand against it; and Maedhros had his own brothers and vassals to rule over, in less official fashion, without the benefit of official authority to put them in place if it prove needed.

They pledged their troth under the stars, a wordless promise with no bitter oath to mar it; and thereafter took the greatest care and discretion that none guessed at it.

-

It was some effort, Maedhros admitted, if only in their very secretive correspondence, written on hidden wink in the back of their official missives.

His mouth ached, his arms felt emptier - poetry, he found, spoke to him beyond the pleasure of precise meter and rhyme.

It was absurd; it was dangerous. Always he kept Fingon swept from his mind, lest some of his heart bleed through enough to be perceived; and always it was work, to keep Fingon out of the forefront of his thinking.

And it was mortifying, too. To be infatuated, to have a joy to hide, to know himself cherished and desired - he could not have bourne it to be known, not easily.

It was only some consolation to know Fingon found his pining ardor very pleasing, being that he was at too great a distance to do much with that. As a matter of fact, it made it all the more torturous.

This lasted all through the first fortnight of the autumn summit.

Maglor looked at him indulgently. “How many horses can Fingon possibly need? Nay, not at all. You must give him the best foal, and rear it by your hand, and drape it in Fingon’s raiment and colours, and teach it the signals he favours. Quality, not merely quantity! Do you hear me wasting breath on too many love songs? There must be a measure, by which things are made precious.”

“You were song-wed by proxy fashion to an ascetic zither-master you knew from correspondence only, and met thrice every ten yéni,” Maedhros told him.

Maglor shrugged. “Once every ten yéni was enough. It made the anticipation all the sweeter.”

Maedhros raised all three colts to perfect training. If some of his braids were chewed away, and much of the fur of his best coats, then at least Fingon was suitably impressed.

-

None guesses at our affections, Maedhros amended on his next letter, besides Maglor, and his silence is our boon. Fingon was swift to tease him for that - and in truth he had barely bothered to hide it from Maglor.

There was little use; therefore he worried little. All the rest of his brothers held their own domains, were occupied with their duties - if it became pressing, he could always invent a new task to distract their tracks.

He had forgotten Caranthir. Caranthir never needed to be given new directions; if anything, he excelled at taking attentive initiative, especially on matters of international commerce.

“I,” Maedhros said. “Have never offered any thing, to lord or vassal, besides gifts of friendship, and diplomacy, and cunning morsels of what might attained with a better trade arrangement.”

“Explain to me how Fingon’s newest gem-crown counts as a diplomatic expense,” Caranthir demanded.

-

Besides Caranthir and Maglor, none noticed.

The next time they met - a well-prepared hunting retreat, and the anticipation did have a certain strain of pleasure in it - it was only some time after the first enthusiastic greetings that they found time and patience to speak at lenght about their dealings, those small or great matters they had not trusted even to set to hidden writing.

"Did you -”

"I told none. Besides those who know."

“Are you entirely certain. Amras and Amrod keep sending me cured meats? Excellent sausages for my table, and lovely truffles. For some reason; they did not last year.”

"They are not poisoned," Maedhros assured automatically. Then hesitated. "They do like to experiment with spices and certain powders, however."

"I noticed," Fingon said, mouth curved. It was a lovely smile, better for being not amused; Maedhros suffered the rather stupid instinct to kiss his cheek. "Around the time the sugared mushrooms caused an apparition of a great mammoth grazing upon my father's head as we sat in public Council. It appeared purple to my eyes, the mammoth; also my father."

Maedhros had suffered great torments of the flesh and spirit; the image made him wince with genuine feeling. Fingolfin kept a very eclectic conjunction of lords near him, Sindar and Noldor and Avari, all of them clever, cunning, far-seeing people with an unhappy habit of keeping a wide awareness to every stray thought that they might fish out slyly round them on a wide range of space. It made Maedhros feel unusually warmly towards his straightforward, stone-silent dwarves and the fierce, scarred, closed minds that came to serve Himring.

"You need to string them up from a high tower," Maedhros concluded. "You shall have their apologies in a season."

"Need is a strong word," said Fingon. But his mouth was twitching, more genuinely.

Through the place where their spirits pressed together he passed on the faint, kaleidoscopic memories of that afternoon - Maedhros had stifle his own crinkling eyes. It was impossible not to admit Fingolfin did look rather fetching in tints of purple; and the mammoth was very realistic.

"If you want them to redeem themselves, have them send more next year. I would rather have enjoyed them in privacy. Lalwen thought it was very amusing. Eventually; she stole the rest of the bounty, and left me none at all, which was very like her and rather a disappointment. If your brothers are found wandering the wilds naked and intoxicated, you shall find no way to prove it was her work."

"They will enjoy it too much." Maedhros thought of when the twins's nonsense had been joyful, once. And involved less paperwork. The worst of it was that they likely thought it a good gift.The twins had ever liked Fingon well enough, as much as they liked anyone outside their enclosing understanding.

Fingon turned around, with that sweeping grace that made him deadly. In a moment he had rolled them over. His hands dug into the loam around Maedhros's head; his legs tangled in him, pressing down, delicious.

There you are, he thought, directly at Maedhros. No distance at all, and his laughing mind dizzying like a windfall, a sweeping rush. You stay away too often, Russandol, even here.

"Let them," he said, voice low and warm, close enough Maedhros could feel it thrum in his own throat. He was so very warm. Maedhros's whole body felt alive under him, as if he were fresh from a battle; as if it could feel alive and joyful with no violence. "I mean to enjoy myself with a clear mind. I mean to recall you perfectly while we are apart."

-

Maedhros, rather wisely, he thought, kept any commissioned tokens away from familiar forges.

It was a marvel, the inspiration which which Curufin could contrive as an insult. In this he truly was Fëanor's heir.

I will not have any of our Father's house be known for offering substandard works, he wrote, a stiff note of parchment atop a casket.

Inside the casket was a treasure - elf-made emeralds, and rubies, fine gleaming garnets that caught the golden light from the candles and would assuredly shine beauteously strung around golden ribbons, and on the chained earrings Fingon favoured.

Keep those Dwarven pieces away from Fingolfin and his ilk, lest he rethink our work agreements. Have you lost your sense, along with your shame? Findekáno's not the least suited to Belegost's blue-steel and sapphires, they wash him out terribly, I do not know how Fingolfin can be so tasteless in his heraldry as not to consider it.

-

Maedhros recalled a time when his brother at least pretended to attend to elvish mores, those small contrivances of decent conduct. Such as pretending at ignorance. Pretending at ignorance had been a good habit, one Huan's master remembered these days merely when it was convenient for him.

Celegorm only looked at him in a flat vulpine fashion, nostrils flaring. Worse than a smirk, worse than mischief. Maedhros had seen it turned on others often enough; he could not say he enjoyed the very unpleasant awareness with which it remind everyone of all the passionate embraces they may or may not have indulged in the wild, where a little bird might carry gossip, or a finicky squirrel pass on mockery.

It also made him rethink the wisdom of wearing Fingon's undershirt under his tunic.

"Not a word," he ordered.

Celegorm only whistled in wolf-like fashion and darted away from his swing.

The next time Fingon dared him for a swim after a lengthy ride up the hills of Barad Eithel, Maedhros quite ruined the romance of it all by insisting on raising a tarp-and-leather tent beforehand.

-

Huan had the good grace to wait until they passed each other on an empty corridor before stopping to block his path.

Oromë's hunting hound looked at him with those terribly knowing dark eyes and let out a soft snorting sound. It was not a very approving woof; a little mournful, perhaps. Maedhros did not speak Hound.

"Do not you start also," Maedhros said. His tone held little effort, as it ever did in these cases.

He had to fight the instinct to cross his arms. He refused to be easily biddable or intimidated. As a matter of principle; he had few of those, and it tended to be better to keep to those he did maintain.

Woof-woof, said Huan.

"We are all Doomed regardless," argued Maedhros.

A sniff, rather pointed. A little charming, perhaps - none of his brothers had offered, so far.

"It is very generous of you to offer," Maedhros said. "No biting will be necessary. I would rather Fingon whole as he may."

Huan licked his bad arm. Shifting ears, which, in all honesty, were insulting.

"I am not letting myself be carried off as a mate to establish a new collective dynamic as pertaining previous intra-community competitions," Maedhros said, rather stiffly. "No, not though I was stolen from the Enemy for that purpose."

Maedhros did not speak Hound, as such; but Huan and him understood each other a little. If anyone was going to look at him with the knowledge that Maedhros would have let himself be carried off as a prize, and possibly did not dislike the notion, he would rather it was him.

"I will bring you some of that good hind meat from Dor-Lómin," he conceded, eager to bribe him away.

Huan's dog-grin finally widened. Maedhros, relieved to be free from evaluation, scratched his chin until his wagging tail was thumping the carpet. Some relatives, he thought, were harder to please than others.

-

"We have failed at every avenue," Maedhros concluded, as displeased as he could stand to be just then. "Let this be not a sign of our joined efforts to come!"

Fingon was rather less moved at their failure than Maedhros would have expected. Possibly that was the effort of the long ride to the fortress, and their - reunion. Maedhros did not want him alarmed and on his feet, as such; but he did eye his complacence a little.

"Brothers are not Balrogs. It could be worse," Fingon said, very confidently.

Maedhros lifted his head from Fingon's chest. His own eyes were growing half-lidded; his muscles too felt weary, suffused still with satisfaction. Himring's walls, warm within like a living body, rumbled faintly with the noise of their gaseous pipes. He was warm, and sated, and all in all quite in accord with the form of the world, at least for the foreseeable candle-mark.

It was only that he had not trusted messengers to pass on the news; and he had felt an urgency to share the state of affairs with Fingon for months. They had determined to be fully discreet.

"How?"

"Turgon and Aredhel might return," Fingon said promptly. His voice showed he had considered the matter at great length, and was very amused by the way Maedhros went still against him. "And be less generous with their blindness than the rest of my - our kin."

"They might not have noticed. Your father has not."

Fingon lifted himself on his elbow, and looked at him, a little pityingly.

"Beloved," he said. "Whom do you think invented the art of invisible writing?"

#february ficlet challenge#prompt 2 - pretend not to be dating#maedhros#fingon#russingon#my fics#silm fic

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mun Speaks: More about Molinde

And because I still have some time, I am going to talk a bit more about my girl Molinde.

She can be a bit material. She will be kind, do stuff for free from time to time, she will find a really good compromise and fold herself over if needed, but let's face it: a girl's gotta eat. Even if it is just a coin or two, she will take payment for her work. She has learned the hard way that if she doesn't want to starve to near death, as it happened when she first set foot on ME, she needs to have some money. Also, material costs, especially if it is during a war and especially if Lord [INSERT NAME] has requested banners today for yesterday.

I know I have said in her bio that she has petitioned several times for the hand of a SoF in marriage in exchange for free war banners and tapestries. This is not actually something she is THAT serious about, she is self-aware enough that to even think of attracting the eye of a prince/king she should actually do something worthy and that seing/embroidering war banners is just her job. The "petition" is mostly something she says to the Elf in charge of designing the banners when they request her something inane and ungodly.

Due to the above she has indeed collected a few pricey things. Like a metal/silver armor that she dons over her dress when needed (because she can fight, but she is not a soldier)

By the time she is in Eregion she has a tiny army of apprentices and she can delegate a bit of the smaller work to them. She personally taught them all.

Of course she knows that "Annatar" is Sauron. She has seen him in the First Age, he has spotted her. They have a general idea of who is who, but it's the second age, Sauron is undercover and she maybe is thinking that she is seeing things, until something really clicks. And then it's like the "I know that you know that I know that you know". They probably are spending time together mainly for different reasons: she is hovering over Annatar and Celebrimbor to keep an eye on definitely-not-sauron and he is trying to get her off his scent. She definitely feels guilty, but also she is seeing Celebrimbor full of energy, Eregion thriving and she knows she'd just be taken for a mad elf if she said anything at all. She might suggest, or give a nudge, vagueing about the whole thing, but she definitely will carry her guilt. And then ofc everything happens and she then sews the "FUCK YOU, I TOLD YOU THAT "ANNATAR" WAS SUS AS HELL" banner.

By Third Age she is noticeably quieter. She is now established in Imladris under Lord Elrond's realm, and she has mostly left war banners in favour of napkins, handkerchiefs, tablecloths and pretty dresses. I have headcanoned her as the one who taught young Arwen how to embroider/sew. I think it gives her a nice closure.

Whilst brainstorming a little bit, I quite liked the idea of her finally tying the knot with Maglor (who in my head is in Imladris as well under code name Lindir), who has been found by Elrond and dragged in Imladris. Yes, I know Maglor is technically married already, but would he still be in the Fourth Age? With his faceless wife apparently ditching him the moment he followed Father and Brothers? I think it would be nice for Maglor and Molinde to bond over shared losses and proceed from there <3

Thoughts? Comments?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

@silmarillionepistolary Lord Maedhros of Himring

Prince Nelyafinwë Maitimo Russandol of The Noldor

I’ve sent my latest ledger alongside this and I believe you know by now that there is no chance of you finding a fault with it so let’s not shall we? You will not be able to prove anything with any group of accountants you can cobble together from those battle fixated imbeciles in your employ and it’s not as if I intend to withhold aught from you.

I agree begrudgingly that we must approach things from a united perspective, why I even agreed to give Celegorm a loan recently, for military matters apparently though I have my doubts, and I certainly won’t see a coin of it returned without having to write him much more persistently than I like to. He’ll yield eventually, he always does. Though it would be faster if you applied some pressure as well I’m close to getting Ambarussa on side and he’s always been putty in their hands so your assistance isn’t strictly necessary this time.

I am aware that when you talk about the risks of fighting amongst ourselves you are including the Arafinwean and Nolofinwean elements but I am simply electing to ignore that excessively ambitious request. The only ‘us’ that matters to any extent here is the seven of us and our followers and I think, considering I would say those relationships are all in a relatively good place presently, you should cut your losses and accept the win on that front.

You can’t fix all the Noldor, Maedhros, and the sooner you manage to accept that the better as far as I’m concerned. Besides, from what I hear of your own particular diplomatic skills in regards to a certain Nolofinwean you should have an in there no matter what the rest of us do. Curufin and I think you don’t take advantage of it anyone near regularly enough when all of Beleriand knows he would not refuse you any favour you may ask of him but I suppose that’s your own prerogative; we can count on his support on the more dire situations for your sake which is something in any case.

I trust my last shipment of wool will have reached you by the time you receive this; which is all for the better considering I have heard from reliable sources (Maglor but even so) that the weather has taken a sharp turn into an early winter. It was your decision to settle so far north when you could have shunted it on to those Arafinwean brats so you shan’t get my sympathy on that matter but it wouldn’t do for us to lose our mannish recruits to the cold, without all the soldiers we can get our position in the north will quickly become untenable.

In reference to your last letter I do wish that you would stop nagging me about said Arafinwean brats, Nelyo, I have been entirely well behaved in my dealings with them in recent months and am entitled to place whatever taxes I wish on my own exports. If they are unhappy with this they can go elsewhere, they certainly shouldn’t go whining to my older brother to get a discount on my perfectly standard rates.

The disparity you pointed out between their rates and your own was entirely unfounded as I am naturally giving you a discount as head of the house of Feanor and my boneheaded older brother who decided he’d like to freeze to death while fighting off Morgoth armed only with fury. So really you should be thanking me but I am used to receiving no gratitude for my efforts with this family so I shall let it slide.

As for the comparisons you drew between other rates and their’s, if you had time to peruse them I have a list of criteria for which I give lower prices and why they apply to specific groups, ledgers upon ledgers of meticulous, complex calculations, Nelyo dear. Dorothion just happens to meet none of them by pure chance.

On the matter of my trade to the west I think the plan you detailed in your last letter sounded quite satisfactory. I assume you have already begun on having the diplomatic groundwork laid down so we receive ample credit as the benevolent saviours of their economy for the deal I ran by you?

It’s rather ingenious I have to say, I’m sure your end of it will work perfectly and you needn’t worry about the wording of the deal itself, it’s quite brilliant if I do say so myself. Irreproachable really, Fingolfin won’t be able to find any justification to turn it down without looking hopelessly petty. Maybe have Maglor spread a bit of propaganda, some catchy song with subliminal messaging and the like, he’s quite useful for that I suppose. It’s a pleasure doing business with you as always.

I should pay a visit to Himring next summer if all goes to plan, I would only be staying about three months mind; it’s looking to be a busy year and I’ve already got two important trade deals lined up for the autumn that I should be east for at the final stages. I warn you this far in advance because I know your Fingon tends to travel north in the warmer months and I’m sure you would like to avoid any overlap after last time with Curufin.

I recommend you issue an official invitation for a state visit soon, it makes it simpler to write things off as diplomatic expenses on my payments to Fingolfin and it is going to be a hard winter after all. I look forward to it, I haven’t seen you in quite some time now, I miss you. Keep an eye on Maglor, his expenditure has been lower than usual recently and while it hasn’t crossed the threshold of a concerning change best watch for anything out of the ordinary.

No I am not giving you a source for my information on his accounts, I have my ways and I’ll leave it there. On an entirely unrelated note now would be an excellent time to see if Belegost may be more open to a military agreement with Himring than it was previously. I have my ways.

The Lord Caranthir of Thargelion

Prince Morifinwë Carnistir of The Noldor

#silmarillion#tolkien#silmarillionepistolary#caranthir and maedhros#caranthir#maedhros#sons of feanor#feanorians#Background Russingon

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1 – Maedhros – Coping

For @feanorianweek You can also read it on AO3

Maedhros used to think he didn’t have a traditional Noldorin craft. That his craft was the same as his grandfather Finwë’s, excelling in diplomacy, politics, being a skilled orator and an attentive listener, a natural leader among brothers, cousins and his people. That his talents ended there and no further.

He knew his father was proud that he had found in him a worthy heir in court. Yet Maedhros always knew that Fëanor secretly wished he had skill and passion in creation, in the works of his hands.

So, Maedhros applied himself, and took lessons in any and every craft he could find. He weaved and stitched and embroidered. He carved and apprenticed with carpenters. He did masonry, wove baskets, and painted landscapes and portraits alike. He played with clay and chiselled stone together with his mother. He hammered hot metals and cut precious gems under the tutelage of his father. He hunted in the company of little brothers and cousins, and sang songs and played instruments privately, only sharing with steadfast Maglor or beloved Fingon.

In every craft he tried his hand at he did good, solid work, but never exceptionally, and never passionately.

Now, Maedhros lay bundled in soft furs and linens, steadily healing from wounds, starvation, and exposure to the elements, grateful for dear Fingon’s kind and valiant heart, grateful to be alive. Yet he was left short of one hand, and with no craft to keep the nightmares at bay.

Relearning to merely write with his off hand was a slow and arduous process, what chance did he have for anything more involved than that? He could not hold an embroidery hoop properly in place, and his fingers shook and cramped up from pinching a needle for more than five minutes. He was more a hazard and a liability in the forge, he had too few hands to play any instruments other than a drum or tambourine, and his voice was shot to gravelly rumblings from screaming it raw in pain. He would eventually learn to hunt once more, but never with bow and arrow again, and more out of necessity.

Then one afternoon a bundle of charcoal sticks lay waiting on his office desk with a pile of blank parchment. Maedhros stared and contemplated it for a while, and shoved it aside to ignore in favour of hours of paperwork. Eventually, though, his mind grew weary, and as the Sun dipped low on the sky into twilight, he reached for a fresh unmarked parchment. Maedhros mindlessly sketched shapes and lines, the soft scratch of coal on paper and the repetitive motions of the hand soothing to his mind. By the time a servant came in with the dinner tray, he had scribbled the interior of his office down.

He thanked the servant as she left and regarded the work of his hand. The lines were uneven, and the perspective was off, yet the image was recognisable. With practice it could be improved upon.

Maedhros doodled and sketched every night, his office over and over again, until it looked perfect. Then the view outside his window, the crow on the ledge, a still life of his dinner, and many, many portraits of his staff, warriors, his people.

One day he found his charcoal sticks replaced with a brush and watercolour paints. Then months later it was gouache, then egg tempera, and finally oil paint. The walls of Himring were soon lined with landscapes of fierce mountains and sleepy meadows, of riders on planes and warm torchlit halls full of revelry. In Maedhros’ private rooms he kept only two paintings. One was a tableau of himself with his brothers arranged around him, proudly displayed above the mantelpiece. The other a simple portrait of his dearest cousin, kind smile and gold braids falling to his shoulders, guarding his dreams beside his bed.

When next Maedhros found a lump of clay on his desk and a pottery wheel by the window, he knew he was up for the challenge.

He quickly saw that forming the clay with only his one hand made the process more difficult, the cups and vases under his touch turning wonky and lopsided without the counter pressure. Maedhros thought of being stubborn about it, trying again and again until endless practice yielded results. But it only takes one mistake that almost had the lump of wet clay spin right off of the wheel, and he instinctively reached for it with his right, and his wrist ended up pushing it back onto the wheel.

Maedhros experimented after that. His single hand pinched and manipulated as dishes and mugs spun into form, while he could push and smooth the soft clay with his stump, and easily reaching inside his creations with it to widen the mouth of a vase.

Sitting down to do pottery at the end of a long day calmed his mind and nerves perhaps better than painting. The motion of his leg working the treadle was a steady rhythm he matched his breaths to. The slow yet decisive movements of his hand and stump required just the minimum of focus to empty his head of all worries and nightmares. The coolness of the clay sticking to his fingers and scarred skin grounded him in the present on dark nights when his memory wished to steer him towards pain.

Washing away the residue from his stump at the end of it all almost felt like healing.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

My headcanons for Maglor and Curufin's wives

Curufin's Wife

Her name is Wilwarindea (means butterfly-like)

She's a painter! She favours watercolours.

She has a strange sense of humor, laughs at weird things.

kind of a funny little bird all around. The type of person to see a misshapen fruit at the market and packbond with it.

She’s whip-smart.. but also a bit of a cloudcuckoolander

Very sweet but doesn't fall for Curufin's nonsense.

Or anyone's nonsense really. It’s part of the reason Curufin fell for her.

Half-Vanyarin

She dies at Alqualondë

I’m unsure that if she would have lived that she would have followed Curufin to Middle Earth, I’m leaning on the side of her going, if only for her son.

Maglor's wife

Her name is Tintilare Ivariel

Maglor calls her Lissë as apesse

as you can tell by her fathername, she's the daughter of the Ivárë mentioned in the Lay of Luthien and Beren!

She met Maglor when he went to study music under the Teleri.

She and Maglor originally HATED one another, she thought he was a spoiled big-headed idiot and he thought she was a snobby tightwad

Musical rivals to lovers

Their relationship was also a musical partnership

Arguing about chord arrangement is their idea of foreplay

She doesn't go to Middle Earth (get divorced, Maglor you bozo)

Really struggles after the Kinslaying at Alqualondë because those were her people that died, but also she's guilty for their deaths in a way. She isn’t welcomed back by the Teleri because of her connection to the Feanorians. and her other family has all left (and is also stained with the blood of innocents)

Hangs out with Nerdanel for a while.

Her and Wilwarindea were extremely close and best friends

Her feelings for Maglor are very conflicted

She loves him and doesnt love him

and they've been apart longer than they ever were together

and the name she loved him with is not the name he is now known by. He will always be Makalaurë to her.

but Elves marry for life and so it's a rough situation all around

The first time she hears the Noldodantë she is inconsolable.

I like to imagine that the tune in the section about the kinslaying at Alqualondë is based on music the two wrote together

#I am so attatched to these ladies#i orginally made Lissë in eighth grade#she's changed a lot over the years#Maybe I should make a tag for these characters#the world is gnawed by nameless things#silmarillion headcanon#silmarillion#the silmarillion#maglor’s wife#Curufin’s wife#I get so crazy thinking about them#I love them soooo much#I have face claims for them too!#And drawn designs#the marchioness rambles

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's interesting how, in the Maedhros poll, everybody believes he started out as a good person. Whether he later turns into a misguided soul, or an anti-hero, or an anti-villain, or straight up villain is up for debate. But the consensus on him being morally good at the beginning is unanimous (or that is how it seems to me, given how I favourably worded the poll).

I find this fascinating because I disagree. I don't think he was ever a good person; he wasn't evil but he wasn't good good.

He showed loyalty and care towards his loved ones, yet he never went out of his way to help others, nor was any particularly good deed attributed to him. Have we seen him interacting in good faith with people outside the Noldor? (But he looked for Dior's twins! Did he find them though? It's the thought that counts! Well, his thought might as well have been to capture them for ransom, who knows?)

Some examples of a character being good are Fingon, he gambled his own life to rescue Maedhros, swept in at Alqualonde thinking the Noldor were being unjustly attacked. Even Caranthir is shown to possess compassion when he rescued the Haladin. Maglor famously slew a traitor, fostered their enemy's twins, and argued to break the Oath. Finrod was often found mingling with Men and willingly walked into the enemy's lair and thus to his death, all to repay a life-saving grace.

Amidst all this, what has Maedhros done to be called 'good'? He stood aside at Losgar but did not take any action to stop it or remedy it. Indeed, he stood aside at all for Fingon, not for Idril, or Finduilas or any of the others. Then he 'begged forgiveness for the desertion in Aman' and gave up his crown to keep peace, but the question arises, why could he not ensure harmony between the factions if he was King and repenting? Was it fear of his faction's arrogance or the distrust of the other? But a king is he that can hold his own, and Maedhros knew he could not do that. I think this act was a play at leaving with his head held high than to have himself be dispossessed of it. He might not be power hungry but he was pride-driven.

Then came the Dagor Bragollach. Most of the Fëanorions are driven out of their strongholds. Where was Maedhros? We have Finrod trying to help his brothers, while he himself is saved by Beor in turn. And in the end, it is Fingolfin challenging Morgoth to get revenge, if not reprieve, for his people. Where was Maedhros? He did deeds of surpassing valour to defend his own fortress. The narrative never has him extending a helping hand to anyone.

Then comes the Union of Maedhros, the alleged helping hand. An attempt to gather Beleriand together to fight against Morgoth. But was it to defeat the Enemy once and for all, ridding the people of his tyranny? Or was it to retrieve the Silmarils? Here too, Maedhros was asking for help, not giving it. Maedhros and his brothers only ever stood against the Vala because of their Oath and personal vendetta. It was never about 'oh but Morgoth is the enemy of all free people'. Their reasons were not altruistic.

Maedhros was never portrayed as virtuous or kind or empathetic. His descriptions in canon (if we can rely on its consistency) all leaned towards how lethal he was. That is not the mark of a good person. It is easy to forget Alqualonde in light of Doriath and Sirion, but never was it said that Maedhros did not kill in the first kinslaying. If the text could note him standing aside at Losgar, if 'good person' Maedhros ever aimed to maim instead of kill at Alqualonde, we would've known. But it didn't happen. He willingly shed blood, made no attempts to diffuse the situation, and agreed with his father 'to seize all the ships and depart suddenly' while leaving the rest behind. All this before his capture and trauma induced personality changes.

He did repent some things: the desertion of Fingolfin, Doriath, Elured and Elurin (note the lack of Alqualonde and Sirion). His repeated offences though, minimise any redemptive value this could've held. Moreover, did he ever send aid to the refugees at Sirion? Did he ever compensate all those who lost their loved ones on the Ice? So did Maedhros truly repent or was it again the thought that counts?

Maedhros may not have started with sins staining his records, but he also did not start with virtues painting him golden. He was deemed a good guy, simply by virtue (one of very few) of not being a bad one.

#this is simply how I chose to read him. not an opinion on your opinion of him#or how he truly is in 'canon'#I greatly prefer to see him as someone masquerading as good or rather trying to be good when he's actually quite grey#maedhros#silmarillion#me back on my 'mae was always bad guy coded' agenda

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multiple Sentences Monday

Tagged by @tanoraqui, @welcomingdisaster and @eilinelsghost to share a WIP snippet! Here's a very delirious Maglor utterly failing to grasp what's going on:

Tried to check how Nelyo was eating — for he so often neglects it in times of stress — but he was wroth to see me, and shouted at me, and carried me back to my bed by force — I do not know why, and I tried to apologise, and then he kissed my forehead before he left — so perhaps he is not too angry. I hope not. Need to make sure ~ Tired, so tired, I cannot make it out — and it was so very cold in the room when I woke, and it seemed to me that a great Wyrm was looming over me, but I was alone, and thought I might go searching for Nelyo. I checked the battlements first — he often likes to walk there, and look out at the land, and sometimes (though I should not say it) brood. But he wasn’t there, and the air was so terribly thick with smoke, and then I came across Nelyo on the way back to my chambers. He looked very afraid, but he kept his voice calm, and said, “Káno, why are you out of bed?” I tried to explain that I was worried about him, and wanted to make sure he was well, and then he laughed for some reason, and brought me back to my room again. I did not want to get into the bed — I had just woken up, after all. But he said, “It would be a great favour to me if you would rest, my Káno,” and he looked so worn about the edges that I did not want to defy him. Once I had lain down he took my hand, and his skin was so cold to the touch that I grew worried.

Tagging @thescrapwitch and @polutrope if you'd like to share! <3

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

And Love Grew: Chapter 4

Rating: T | Violence, Character Death Words: 5.3k (Chapter), 17k (WiP) Relationships: Elrond & Elros & Maglor, Caranthir's Wife & Maglor Characters: Maglor, Elrond, Elros, Caranthir's Wife, Original Characters Genre: Tragedy

As a host of survivors makes the journey from Sirion to Amon Ereb under Maglor’s leadership, old bonds unravel and loyalties crumble. But from the scraps and ruins, new and unlikely bonds take shape. A story of perseverance through suffering.

Chapter 4: The host pauses for rest on the eaves of Taur-im-Duinath. Dornil learns some disturbing truths about Maglor. Gwereth does her best to care for Elros and Elrond while struggling against her own grief and anger.

On AO3

Chapter excerpt:

Taur-im-Duinath was a strange forest. So dense with vegetation, pressing out to its very edges, as to seem untouched by any creature that fed upon things that grow. Indeed, besides small stream-dwellers and the occasional bird flitting in and out of the crowns of ancient trees, they had seen no animals. Strangest was that much of what lived here was unknown elsewhere in Beleriand. The forest, vast and deep and verdant, was a world unto its own. Silent, some called it, and by day it lay quiet indeed, its thick growth swallowing the chatter, the whinnying of horses, the scrape of the whetstone, the fall of water from wrung textile. The sounds, too, of children laughing. Glancing up from her work, Dornil noticed the berry-gatherers’ baskets had been forgotten in favour of a game of hiding and chasing through the understory. Dornil’s eyes rose to the darkening underbelly of the clouds. Dusk was coming on. At night, Taur-im-Duinath was not silent. At night, the forest threw back echoes of the day’s noises in strained, shrill tones. Noises that swirled and churned in the mind long after they had died, turning, turning until out of the confusion of sounds voices rose. Voices speaking, shouting, singing.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angband falls. Beleriand sinks. And Maglor’s wandering when comes across an emaciated hand on the sea shore. Now, it’s not uncommon to see bodies and limbs especially with the mass death of so many orcs and elves killed in the War of Wrath.

But this one he recognises.

The ring bearing the star of the Crown Prince turned King, at the time only recently given by a dying father to his eldest son. The misshapen gold from a young nephew learning his craft, worn with pride even in the darkness of Beleriand. Favoured gemstones embedded in a more elegant ring given by a younger brother as a gift for reaching the highest level of scholarship.

But he wouldn’t need any of that. Not really. Because even scarred and bloodied and shrivelled as it is, Maglor recognises the hand of his eldest brother, left in an iron shackle on the heights of Thangorrodrim.

A hand taken trophy by a Vala and enchanted never to decay. A prize with a place of honour in Morgoth’s Iron Hell.

A hand that’s all Maglor has left of his older brother.

Cradling the slowly decaying flesh, Maglor slowly works at pulling off the iron cuff, careful not to damage Nelyo’s hand any further. It takes days. Weeks. But he refuses to make another mark on it. When it finally comes off, he tosses the cursed object to the depths of the sea, and for the first time, leaves the shore.

Ulmo watches as the Singer makes his way inland, single minded focus driving him away from his lamentation. Maglor walks and walks, weeks, months, all the while carefully protecting the last piece of his brother. The Vala of the Oceans isn’t the only one watching as he stumbles and falls and fights what orcs remain with terrifying fervour until he at last reaches what he’s looking for.

A fiery chasm. One of few left in an almost sunken Beleriand. Just big enough to do what’s needed.

Kneeling at the edge, he holds the hand to his chest, and for a moment it’s like Nelyo is there with him, promising it will be ok. It’s all the courage he needs.

When Maglor falls, he doesn’t feel fear. Pain. Grief. Or even the fire.

Only his brother welcoming him home.