#in 1966 they distributed The Family Way

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

#Alan Durban#seems like a lovely man#Paul’s obsession with playing the guitar from the age of 15#<3#also interesting that Paul apparently had shares in British Lion#(film company)#in 1966 they distributed The Family Way#I definitely clicked this link earlier from somewhere but I can’t find where#so sorry if someone posted this exact thing today#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas With the Super-Heroes (Limited Collectors' Edition #34)

I decided to read all of this, not just the Santa story. It contains:

A reprint of Silent Night, Deadly Night (already covered, though in the fun of rereading it, this was definitely recoloured - the most obvious point is Betsy's dress changes from red in Batman #239 to green in Limited Collectors' Edition #34)

Billy Batson's Christmas (two fake Santas) - this is some classic old Shazam nonsense where Billy is troubleshooting things and a model train starts a fire!

Angel and the Ape: The $500,000 Doll Caper - our Santa story. Another story about repairing old broken toys for kids for Christmas. Apparently this was a major thing?

The toys are delivered to...Santa's Workshop. Santa reusing and recycling for Christmas, hey?

Anyway the actual plot is about a man who smuggled in a diamond sewn inside a doll. Only the doll gets lost in a car accident, Angel picks it up, and "Mr Stooge" (the guy who arranged for the diamond to be smuggled) orders his thugs to find every doll in the city to locate the diamond. This goes poorly.

Here are some *sigh* police detectives acting as bait to try and catch the gang.

We also have a 'evil making' gas that gets reversed and Mr Stooge gives Santa 2 million dollars to buy toys for the children.

A Swinging Christmas Carol - this is a reprint of Teen Titans #13 (1966)

This, of course, a retelling of A Christmas Carol, extremely subtly foregrounded by Bob Haney (oh Bob).

Bob Ratchet needs his job with Ebenezer Scrounge to get an automatic wheelchair for Tiny Tom. Yes, really. (Oh Bob). Then Jacob Farley appears. Farley has escaped from jail and used to work with Scrounge.

The Titans eventually realise everyone in this story maps to A Christmas Carol, just in case you, the reader, happen to be unfamiliar with the story, and explain this (Oh Bob).

Wally pretends to be the Ghost of Christmas Past at Scrounge, Garth the Ghost of Christmas Present and Donna is the Ghost of Christmas Future (in a red and white Santa outfit, it must be said).

But oh no! Donna gets shot!

After a fight scene, Scrounge repents his ways and decides to turn over a new leaf, including buying a fancy new wheelchair for Tiny Tom (Oh Bob).

Christmastown, U.S.A. (Part of Action Comics #117)

There's a flood in Christmastown, and the Osborne family, who always supply Santa, have a missing grandson Danny! So Lois and Clark are sent to report on the flood, and Clark as Superman builds a 'Christmas Ark' to float down the flooded river and distribute 'cheer and presents' to all the flooded communities (Superman makes the presents at superspeed out of wood, of course), and Lois stumbles across our missing grandson, who has amnesia after being hit by a floating log. Danny remembers who he is on seeing the ark and his grandfather playing Santa.

Also Superman makes it snow over Christmastown for a White Christmas, which as you know is exactly what a flooded-in community needs.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

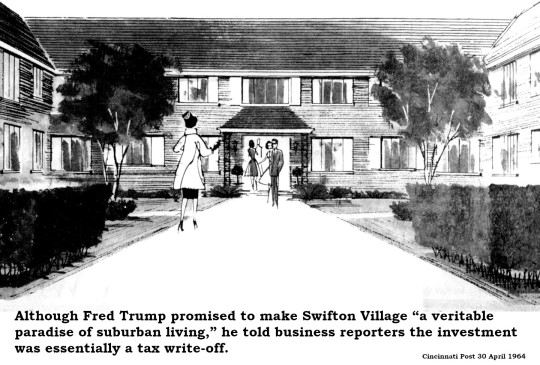

Back In The Day, You Might Have Thought Everyone In Cincinnati Loved Fred Trump

People in Cincinnati were raving about Fred C. Trump a full decade before he ever dipped a toe into Cincinnati’s real estate market. Mildred Miller, in her Cincinnati Enquirer “Talk About Women” column [2 March 1954], begged the New York developer to buy some Queen City rental property:

“Sa-ay, why can’t it happen here? We sure could use a few ace-high landlords like Fred Trump of New York! He not only rents to families with children but also provides many extras to make them happy! . . . Such as playgrounds, indoor recreation centers, summer camps and baby sitters!”

Ten years later, Mildred Miller got her wish when Fred Trump purchased the moribund Swifton Village apartments in Bond Hill. Originally constructed with Federal Housing Administration financing at a cost of $10 million in 1954, the complex was half empty in 1964. The FHA foreclosed on the property and put it up for auction when the original developer defaulted. Fred Trump was the only bidder, snatching the complex for $5.7 million. The Cincinnati Enquirer [6 January 1965] was delighted:

“Before ink was dry on the Swifton deed, Mr. Trump said he sent his maintenance crews into the village on a $500,000 reconditioning and redecorating program. A new community center was built; streets and sidewalks were repaved; paint was dabbed here and there; new refrigerators and new laundry machines were installed; window shutters were ordered. New tenants started coming in.”

Although several sections of the complex were reserved for adult tenants, Fred Trump did build playgrounds in the portions of Swifton Village in which children were allowed. He also maintained a private swim club and sun deck for the exclusive use of tenants.

Fred Trump apparently worked overtime to satisfy the folks who lived at Swifton Village. One employee recalled when the owner visited Cincinnati around Mother’s Day and bought 1,000 orchids to distribute to the resident mothers. Trump passed out thousands of pre-stamped, pre-addressed post cards to all his tenants encouraging them to send complaints and suggestions directly to him. Enquirer business editor Ralph Weiskittel enthused [2 October 1966] about the benefit:

“This is the ‘service’ aspect of our plan, Mr. Trump said. When a tenant calls for a service he wants it ‘then’ – not an excuse that workmen are busy and will get to it the first thing tomorrow morning.”

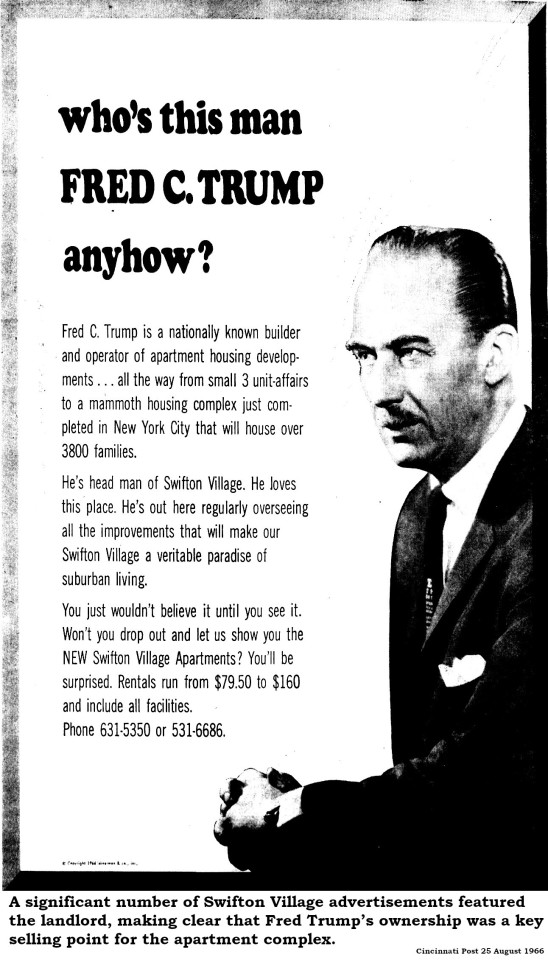

Of course, the New York developer spent a lot of money burnishing his own image. The entire time he owned Swifton Village, every newspaper advertisement specified that the official name of the complex was “Fred C. Trump’s New Swifton Village.” Trump ran advertisements touting his concern for the tenants’ welfare. One advertisement in the Cincinnati Post [25 August 1966] promised a lofty goal:

“Who’s this man Fred C. Trump anyhow? He’s head man of Swifton Village. He loves this place. He’s out here regularly overseeing all the improvements that will make our Swifton Village a veritable paradise of suburban living.”

Another advertisement in the Enquirer [27 August 1966] emphasized his personal touch:

“This man worries a lot. If you lived here, you might be getting a phone call from Mr. Trump. Sound strange? Well, that’s the way Mr. Trump works. Several times a week (in addition to his regular visits) he picks up the phone and makes a long distance call to a tenant in his Swifton Village Apartments. Just to check up and find out if they’re content. Are things being taken care of? Anything he can do to help make living in his apartments a bit more pleasant? He’s the kind of landlord who worries about you.”

As a couple of lawsuits revealed, Fred Trump reserved his worries for his white tenants. In 1969, according to testimony by Trump’s own lawyer, only two or three apartments out of 1,167 in the complex were occupied by Black families.

The Cincinnati lawsuit was filed on behalf of Haywood and Rennell Cash, a young couple living with relatives because they were unable to find an apartment. At Swifton Village, they were told there were no vacancies, but they suspected otherwise. They consulted with the Housing Opportunities Made Equal organization, who sent a white woman out to Swifton Village. She was immediately offered an apartment. When the H.O.M.E. shopper returned with the Cashes, the apartment manager threw all of them out of his office.

A New York case, filed in 1973, involved almost identical circumstances, including allegations that Fred Trump’s managers falsely claimed that no vacancies existed and required higher rents from Black applicants. The New York lawsuit itemized incidents of discrimination at more than 17 Trump properties in New York and Virginia.

As it turned out, Fred Trump had been accused of discriminatory rental practices for years. At one point, folksinger Woody Guthrie lived in one of Trump’s Brooklyn buildings and crafted a new verse for his song “I Ain’t Got No Home” as a protest against the policies that kept that complex exclusively white:

We all are crazy fools As long as race hate rules! No no no! Old Man Trump! Beach Haven ain’t my home!

Despite his advertisements professing love for Cincinnati and his tenants, Fred Trump dropped a few hints indicating he was on the fence about his investment here. He told the Enquirer [6 January 1965] that Cincinnati was “a real disappointment” because the market was “overbuilt.” He described Swifton Village as a “Mexican stand-off,” meaning he expected to do no better than break even on his investment and that the property would mostly function as a tax write-off.

In December 1972, Fred Trump sold Swifton Village to Prudent Real Estate Trust of New York for $6.75 million. He never again entered the Cincinnati real estate market. All of the original Swifton Village apartment buildings were demolished around twenty years ago to make room for a new housing development.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

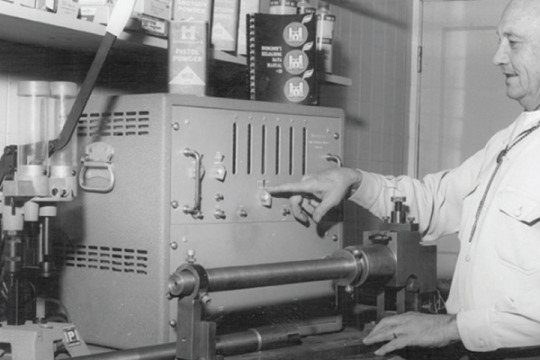

THE HODGDON STORY

Success in the American tradition demands the qualities of motivation, determination, willingness to sacrifice, hard work, timing and a true element of luck. Even in our modern times of high taxation, escalating costs, and governmental regulation, it is still possible for the “common man” to become successful if he has a good idea and most or all of these qualities.

The Hodgdon Companies, as they exist today, are an example of this tradition. Until he began the surplus powder business, Bruce Hodgdon was a salesman for the Gas Service Company, traveling local territory selling gas appliances. From a few dollars borrowed on the cash value of his life insurance policy has evolved a manufacturing and distributing company that has customers in all 50 states and many foreign countries.

All his life Bruce Hodgdon was interested in shooting, hunting, and reloading. He custom-loaded ammunition for friends during World War II while he was in the Navy and after, while working full time as a salesman for the Gas Service Company. Somewhere Bruce had heard that the government burned huge stocks of surplus powder after WWI because of the lack of market for them, and he figured that the same would be true after hostilities ended in 1945.

Even though he had no place to store gunpowder, and did not know if enough shooters would gamble to purchase unknown types of propellant, Bruce cut government red tape and soon owned 50,000 pounds of government surplus 4895. An old boxcar moved to a rented farm pasture served as the first magazine, the first one-inch ad placed in the American Rifleman, and Bruce was in business.

The first 150-pound kegs of powder sold for $30.00 each plus freight! Early shipments also consisted of metal cans with hand-glued labels sent out in wooden boxes made from orange crates and sawed on a homemade circle saw by Bruce and his grade-school age boys, J. B. and Bob. A little later, the boys delivered shipments to the REA or the Merriam Frisco train terminal each morning on their way to high school. The trunk of the family 1940 Ford served as carrier for hundreds of thousands of pounds of powder during this time. Bruce’s Wife Amy served as bookkeeper and saleswoman. Very quickly mail order sales grew to include other reloading components, tools, and finally firearms and ammunition.

In 1952 Bruce resigned from the Gas Service Company and B. E. Hodgdon, Incorporated, was officially underway. J.B. and Bob entered the business full time after graduating from college in 1959 and 1961. After considerable expansion in the 1960s, it became apparent that splitting the wholesale firearm business from the nationwide powder business would save confusion among customers and facilitate bookkeeping. Hodgdon Powder Company came into being in 1966 as a result. Eventually, the wholesale firearms company was sold in 1984.

If it were not for the efforts of a handful of men seeing that changes were made, shooters all over the country would now have much greater difficulty obtaining their powders. In 1963 and 1964, Bruce Hodgdon, Ted Curtis, Homer Clark of the Alcan Company, and Dave Wolfe of Wolfe Publishing Company, were successful in persuading the ICC – now the DOT – through exhaustive tests by the Bureau of Explosives to downgrade certain packages of smokeless powder to the much-easier-to-ship “4.1 – Flammable Solid” Classification. As a result, containers under 8 lbs. each and in approved packages of shipments weighing less than 100 net pounds can today be handled by any common carrier, including UPS and FedEx. Previous to this, all Smokeless powders were considered “Class B explosives” for shipping purposes, which is nearly as restrictive as the almost impossible task of transporting black powder.

After retlentless testing, Hodgdon Powder Company received approval for 1.4C shipping in 2014. Now, nearly all canisters up to eight pounds can be shipped under the 1.4c classification, making shipping much more efficient.

In 1967, the Hodgdon’s built what was then billed as “the world’s largest indoor shooting range,” an indoor structure allowing 44 shooters to share a 25 Yard range at the same time. This range and store is open to the public at 6201 Robinson, Overland Park, Kansas (www.thebullethole.com). Although this business was sold to outside parties in November 1982, we invite any of our nationwide customers to visit when in the Kansas City area.

Bruce Hodgdon passed away in 1997. Bruce was among other things an avid reloader, competitive rifle shooter, trap shooter, hunter, NRA Benefactor Member, and World War II Veteran. The industry honored Bruce for his contributions to the shooting sports in 1995/1996 with the Shooting Academy Award of Excellence. The responsibility of running the company then fell to his sons, J.B. and Bob Hodgdon, the two grade-school boys back in the late 1940’s, who worked hand in hand with their father to establish and grow this company.

Bruce’s oldest son, J.B. Hodgdon is still active in the business today and serves on the board and as Chairman Emeritus. He still remains passionate about shooting and hunting pursuits.

Bruce’s youngest son Robert Eltinge “Bob” Hodgdon went home to be with his Lord and Savior on January 14, 2023. Up to his last year, Bob was still active in shooting and hunting activities with friends and family.

Today, Hodgdon smokeless propellants are developed and manufactured to meet the needs of every reloader. The powder that started Bruce Hodgdon’s business, H4895, is still produced and sold along with world-class powders available for just about any Rifle, Handgun, and Shotshell load.

Smokeless propellants are only half of the famous Hodgdon story. Muzzleloading shooters and hunters around the world recognize Hodgdon as the company that makes the best performing, most convenient, safest, and easy to clean black powder substitute propellants. Pyrodex®, introduced in 1976, is the most successful black powder substitute on the market. Pyrodex products are safer, cleaner burning and produces 30% more shots per pound than common black powder. Pyrodex also makes it easier to clean the gun after shooting.

Innovation is a key part of Hodgdon’s philosophy and values. The patented Pyrodex Pellets give the modern muzzleloader speed and safety in a convenient preformed charge. They offer quick and safe no-spill loading, instant ignition, and faster second shots.

Always looking to the future, Hodgdon took muzzleloading to the next millennium with Triple Seven® muzzleloading Pellets and granular propellants. Introduced in 2001, Triple Seven has proven to be very consistent and accurate but is most recognized for its easy water clean up and no sulfur (rotten egg) smell! In 2007, Triple Seven Magnums were introduced. Magnums deliver higher energy for serious hunting knock down power.

Hodgdon Powder Company offices are located at 6430 Vista Drive in Shawnee, Kansas. The Powder magazine, packaging and manufacturing facilities are maintained about 140 miles southwest of the main office, in Herington, Kansas. In 2020, when Hodgdon Acquired Accurate, Ramshot and Blackhorn 209, the Miles City, Montana location was also acquired. The Miles City location is still occupied with office staff, warehousing space and a world-class ballistics lab.

To better serve our reloading customers Hodgdon Powder Company continues to grow. Hodgdon purchased IMR® Powder Company in October 2003. IMR legendary powders have been the mainstay of numerous handloaders for almost 100 years. IMR powders continue to be manufactured in the same plant and with the same exacting performance criteria and quality assurance standards that shooters have come to expect.

In March 2006, Hodgdon Powder Company and Winchester® Ammunition announced that Winchester® branded reloading powders would be licensed to Hodgdon. Winchester smokeless propellants, the choice of loading professionals, are available to the handloader to duplicate the factory performance of loads from handgun to rifle and shotgun.

In January 2009 Hodgdon acquired an American icon GOEX Powder, Inc. GOEX has a rich history dating back to 1802 where E.I. Du Pont de Nemours broke ground on his original black powder plant along the Brandywine River in Delaware. Goex Powder, Inc. manufactures black powder used for sporting applications such as civil war re-enactments and flintlock firearms, and is a vital component for industrial and military applications. Located in Minden, Louisiana, GOEX Powder, Inc. is the only U.S. manufacturer of black powder. Hodgdon then sold the GOEX plant and brand in 2021.

In October of 2020, Hodgdon purchased the Accurate Powder and Ramshot smokeless brands from Western Powders, along with the Blackhorn 209 black powder substitute brand.

The company continues to drive innovation in smokeless powder through the Hodgdon, Ramshot, Accurate Powder, IMR and Winchester brands. On the black powder substitute product side, brands Blackhorn209, Hodgdon Pyrodex, Hodgdon Triple Seven and IMR White Hots continue our history of bringing technologically advanced and unique propellants to the marketplace. Today, as over the last seventy-five years, the success of the Hodgdon Companies depends upon the goodwill and satisfaction of our loyal customers. Thank you for the trust you continue to give our products; we hope our products are a part of the reason you enjoy your chosen sport of hunting or shooting.

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

Derek Taylor 2020: We’re Still Here

That’s about the best that can be said for a year that pulled out nearly every stop in a surging sea change to calamity, adversity and tragedy. The number of people lost to a pandemic that now stands steadfast as a monument to the true meaning of American Exceptionalism as the epitome of empathy-eradicating self-interest is enough to negate even the noblest efforts at laughing to keep from crying. Musicians and music persisted though, even in a severely altered performance landscape of shuttered venues and virtual concerts. And recorded offerings new and archival remained plentiful.

When so much about the present feels like a sprint backwards, societally, environmentally and across multiple other measures, music reliably endures as a means for finding both meaning and footing in the world. What follows are 20 capsule vignettes describing selections from the sea of albums circulated this year that kept me afloat, followed by 25 more in list form that did the same. Thank you for reading and thanks for sticking with us.

Paul Desmond — The Complete 1975 Toronto Recordings (Mosaic)

Given the magnitude of hardship this year’s wrought on living musicians, it may appear a bit perverse to lead this list with a dead one. Even so, this immersive set’s become an old reliable when it comes to achieving aurally-sourced solace. Desmond, the arch and affluent altoist, leaning into a Canadian club residency with ace sidemen while making good on his gentleman’s agreement with absent Dave Brubeck to abstain from piano accompaniment. The leader’s lady-killer instincts are assiduously evident in the amorously-oriented song choices as his dulcet, tranquilizing tone seduces and delights, night after night.

Chris Dingman — Peace (Inner Arts)

An intensely personal project where abundancy of content arose not out of ambition but rather necessity and is made all the more affecting for it. Dingman designed and played the nearly six hours of solo vibraphone music on this set for his hospice-sequestered father with sole purpose of providing comfort and calm. Reflection after his parent’s passing moved him to release it into the world with the hope that it could do the same for others. Intention accomplished.

Joe McPhee — Black Is the Color (Corbett vs. Dempsey)

It’s been a distressing year for nearly everyone, but particularly for McPhee, who lost his brother Charlie to illness. Even amidst ongoing emotional tumult, his fecundity felt undiminished. AC/DC on the British OtoROKU label offers another entry with the English organ trio Decoy. Of Things Beyond Thule, Vol. 2 is a smashing CD sequel to its vinyl predecessor with Dave Rempis, Tomeka Reid, Brandon Lopez and Paal Nilssen-Love comprising the super group. A reissue of the seminal She Knows… with Scandinavian power trio The Thing on the Ezz-thetics label and Black is the Color compiling early concert material in surprisingly sharp fidelity from the Corbett vs. Dempsey imprint cover the archival end of things.

Sonny Rollins — Rollins in Holland (Resonance)

The Saxophone Colossus holding court with Dutch compatriots in 1967. Most conspicuous is daredevil drummer Han Bennink, who even at this early stage straddles swing to European Free Jazz from behind his kit. Rollins shifts between comparatively pithy studio salvos and effusive concert excursions that once again cement his supremacy in the strenuous realm of long form improvisation. Seven decades as a musician makes for a bank vault-sized cache of bootlegs, but this one, refurbished and authorized remains something special.

Stephen Riley — Friday the 13th (Steeplechase)

Like McPhee, Riley’s a perennial resident of my pantheon. This date realized a long-standing wish to hear him in the company of cornetist Kirk Knuffke backed by the freeing simplicity of bass and drums. Both men have aerated, instantly recognizable tones and pliancy in phrasing that provides practically endless possibilities in tandem. Riley’s also instrumental as featured guest on Pierre Dørge’s Bluu Afroo, a slightly preemptive Ruby Anniversary celebration of guitarist’s multinational New Jungle Orchestra.

Sam Rivers — Ricochet & Braids (No Business)

The auspicious launch of a Sam Rivers archival series last year was among the Lithuanian No Business label’s greatest achievements. Two more seminal entries came down the pike in 2020: Ricochet featuring Dave Holland and Barry Altschul of particularly fine vintage, and Braids spotlighting another pivotal Rivers ensemble in Hamburg with low brass wizard Joe Daley. There are four more to go, which should target the end of 2022 for the series’ completion.

James Brandon Lewis — Live at Willisau & Molecular (Intakt)

Lewis is the type of compelling artist tapped for accolades like Down Beat’s Rising Star award, despite having been active as an accomplished improviser for over a decade. Delayed exposure is common collateral to a career path in improvised music though, and the saxophonist hasn’t let slow-to-cotton critics slow him down a bit. A deal inked with the Swiss Intakt imprint has so far yielded Live at Willsau, which finds him in fiery duo with Chad Taylor, and Molecular, a studio venture with an all-star quartet that will hopefully become a working band again in 2021.

Susan Alcorn — Pedernal (Relative Pitch)

Pedal steel may feel like a nascent voice in improvised music, but in actuality Susan Alcorn and her peers have been plying it as a viable vehicle for some time. While Pedernal is somewhat perplexingly her first album as clear-cut leader, impediments to an earlier debut seem inconsequential given the ample amount of thought and design evident in the end product. Strings wielded by Michael Formanek, Mary Halvorson and Mark Feldman weave with the wide gamut of Alcorn’s aqueous sonorities across intricate pieces further stamped by Ryan Sawyer’s peripatetic drums. The results are at once daring and distinguished.

John Scofield — Swallow Tales (ECM)

ECM has an enviably accomplished record when it comes to matching the austerity and formality of its sound design to artists’ objectives. Case in point this stark, but not standoffish trio set that’s as much (electric) bassist Steve Swallow’s offspring as it is Scofield’s. Drummer Stewart is the third point in the triangle, but he sagely defers to his elders, leaving them to a dance of differently gauged strings that expertly balances motion and space.

Corbett vs. Dempsey

John Corbett is emblematic of that rare breed of music monomaniac who balances obsessiveness with altruistic generosity. He’s personally responsible for bringing dozens of rare and classic recordings back into circulation, first through the fondly remembered Unheard Music Series and more recently via the CvD concern. This year, another stack was added to that sum with Milford Graves & Don Pullen’s The Complete Yale Concert 1966 (including the rarified Nommo), Alexander von Schlippenbach’s Three Nails Left, Tetterettet by the ICP Tentet, Peter Kowald’s self-titled FMP debut as a leader and the madcap New Acoustic Swing Duo from Willem Breuker and Han Bennink as standouts.

Whit Boyd Combo — Party Girls & Dracula (the Dirty Old Man) (Modern Harmonic)

Vintage skin flick soundtracks have rarely if ever received an even-handed shake in terms of relative artistic merits. Tarred with the same smut brush as the visuals they were constructed to accompany, they’re routinely viewed as just as disposable. The Whit Boyd Combo doesn’t exactly dispel this dictum, but it does lay down some funky and at times refreshingly fractious freewheeling horns over organ, bass, and drums driven beats on this late-60s session tape excavated by the folks at Modern Harmonic. The companion Dracula (the Dirty Old Man) isn’t quite on par, but it’s still a solid vessel for competently crafted fossilized grooves.

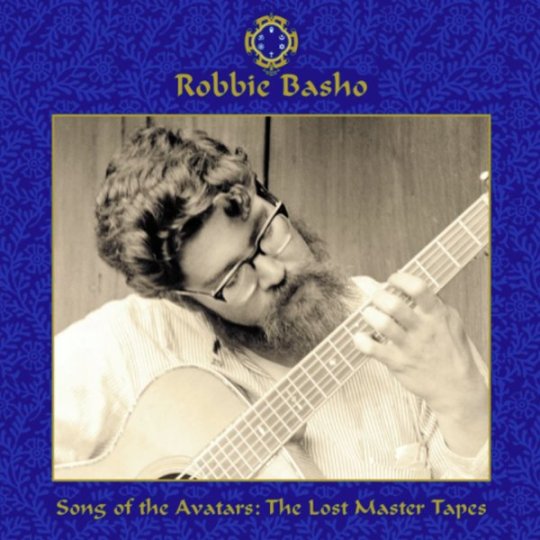

Robbie Basho — Songs of the Avatars (Tompkins Square)

Real Gone Music whet the appetite earlier this year with the release of Songs of the Great Mystery, a “lost session” from Basho’s tenure at the Vanguard label. Songs of the Avatars ups the ante substantially by granting outsider access to a six-hour survey of the dearly departed fingerstyle guitarist’s personal tape trove. The aural riches are ample and include Basho exploring familiar proclivities (Indian, Native American and Japanese interpolations) alongside unexpected new ones (ballet and cantata) with passion and conviction to burn along the way.

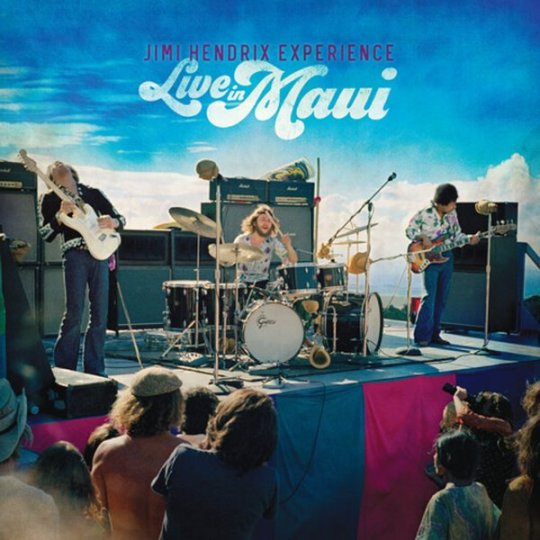

Jimi Hendrix — Live in Maui (Experience Hendrix)

Posthumous Hendrix is a seemingly inexhaustible resource as each year repackaged and repurposed treasures are released into the marketplace. Fortunately, familial heirs are the ones doing the sowing and this lavish set documenting musical and extra-musical particulars of the icon’s reluctant conscription into cosmic hippie scam does right by him. Given the windswept conditions near the Haleakala Crater it’s a minor miracle that he, Billy Cox and Mitch Mitchell mesh as well as they do, and while the footage included can be frustrating in its fragmentary presentation, it’s still a thrill to see and hear them jamming in amiable and ebullient form.

Joe Maneri, Udi Hrant & Friends — The Cleopatra Record (Canary)

Details on this one could easily serve as grist for a credible short film screenplay with perhaps Jim Jarmusch directing. Brooklyn, 1963: A group of marginalized ethnic musicians relegated to playing wedding gigs gets conscripted for an afternoon recording session. The cheaply packaged and provincially distributed results are destined for the anonymity of dime store cut out bins. Except that the band includes two geniuses: Joe Maneri, who would go on to become a master microtonal improviser/composer and Udi Hrant Kenkulian, one of most revered modern doyens of the Turkish oud. Available over at Bandcamp for a pittance.

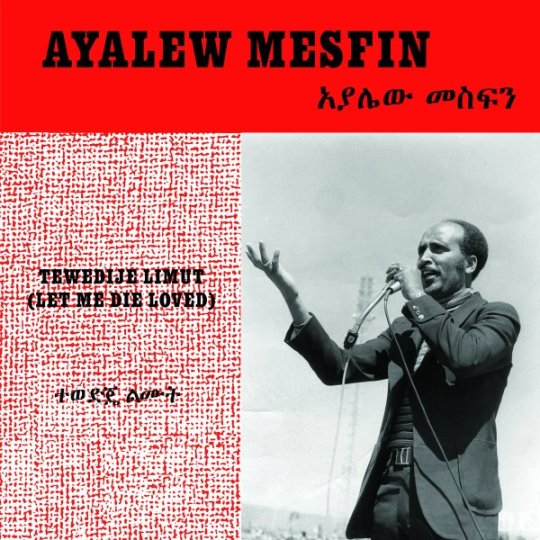

Ayalew Mesfin — Good Aderegechegn, Che Belew and Tewedije Limut (Now Again)

Adding up Buda Musique’s 30-volume Ethiopiques series and a host of other more modest enterprises, it’s obvious that there’s never been more access to vintage Ethiopian music than now. This trilogy of discs from the Now Again label covering vocalist/keyboardist/bandleader Ayalew Mesfin’s catalog restores one of the last untapped reservoirs to circulation. Tight horns, choppy, fuzz and wah-wah drenched guitars and chugging bass fuel dance floor burners while Mesfin’s pipes work memorable magic on a string of melancholic, melismatic ballads.

Kent & Modern Records Blues into the 60s, Vol. 1 & 2 (Ace)

Ace’s appellation as a music label of enviable reach and import has never been an erroneous assignation. This pair of compilations investigates the urban, but far from urbane, blues scene surrounding Los Angeles as documented by the Kent label in the 1960s. Comparatively longer-in-tooth legends like T-Bone Walker and Big Jay McNeely jockey with younger, fame hungry artists like Larry Davis and Little Joe Blue in negotiating a West Coast argot that’s heavy on electricity channeled through guitars and organs. McNeely’s ripping “Blues in G Minor” is one of several snarling sonic wolves in non-descript sheep’s titling.

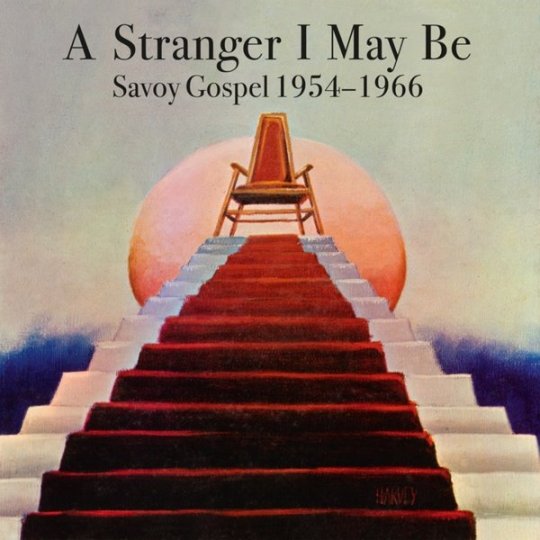

V/A — A Stranger I May Be: Savoy Gospel 1954-1986 (Honest Jons)

This astutely-sequenced set stands out in the particularly plentiful playing field of this year’s gospel reissues. The mighty Savoy label started out as a jazz venture before branching out into other African American musical idioms. The compilers at Honest Jons parse the program chronologically across three-discs and leave the heavy-lifting of context and artists biography to a lengthy essay. Choirs, ensembles, bands, and moonlighting R&B singers all make appearances directing their talents to devotional and invocational celebrations of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost.

Sun Ra

One of the highlight roundtables at Dusted this year was a Listening Post ruminating on the Sun Ra Arkesta with and sans Ra on the occasion of the band’s new release Swirling. I got to play the (hopefully uncharacteristic) part of curmudgeon in those exchanges principally because while I respect the ensemble’s longevity absent their lodestar leader, there’s still an explicit void extant that tends to eclipse my actual interest. The Ra reissue docket for 2020, which included excellent editions of Celestial Love and A Fireside Chat with Lucifer from Modern Harmonic, When Angels Speak of Love on Cosmic Myth, Heliocentric Worlds, Vols. 1 and 2 from Ezz-thetics, and Strut’s Egypt 1971, which collects Dark Myth Equation Visitation, Nidhamu and Horizon alongside a bevy of contemporaneous unreleased recordings, only bolstered the bias.

Fresh Sound Records

Still the standard for thoughtfully and lavishly curated jazz reissues, Barcelona-based Fresh Sound kept commensurately prolific pace throughout the year. Gary Peacock - The Beginnings surveys the recently deceased bassist’s early work as a versatile California-stationed sideman. Remembering does similar service to rare concert recordings by Belgian guitarist Rene Thomas while The Complete 1961 Milano Sessions offers truth in advertising by compiling woodwind savant Buddy Collette’s sojourn on Italian shores with (mostly) indigenous sidemen.

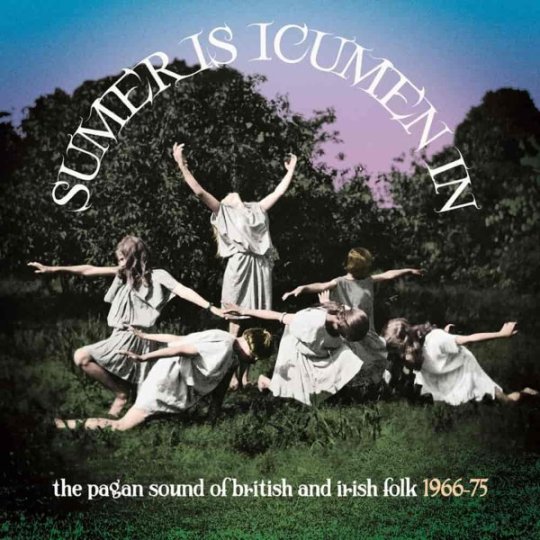

V/A — Sumer is Icumenin (Grapefruit)

An overdue sequel to Dust on the Nettles (2015), which apparently commands on princely sums on Discogs these days, this set encompasses 4+ hours of cherry-picked vintage British freak folk. Second helpings from stalwarts of the style such as Comus, Steeleye Span and Fairport Convention join Albion offerings from obscurants like Vulcan’s Hammer, Mr. Fox and Oberon in celebrating the weird crossroads of ancient Britannic and 1960s counterculture influences. The cant is more to The Wicker Man side of the spectrum with Magnet’s bucolic canticle “Corn Rigs” the ringer in that regard.

Twenty-five more in mostly stochastic order:

Aruán Ortiz - Inside Rhythmic Falls (Intakt)

Brandon Seabrook/Cooper-Moore/Gerald Cleaver — Exultations (Astral Spirits)

Cecil Taylor & Tony Oxley — Birdland, Neuberg 2011 (Fundacja Sluchaj)

Horace Tapscott w/ the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra — Ancestral Echoes: The Covina Sessions, 1976 (Dark Tree)

Damon Smith — Whatever is Not Stone is Light (Balance Point Acoustics)

Frank Lowe & Rashied Ali — Duo Exchange: Complete Sessions (Survival)

Dudu Pukwana — and the “Spears” (Matsuli Music)

Mary Halvorson’s Code Girl — Artlessly Falling (Firehouse 12)

Burton Greene — Peace Beyond Conflict (Birdwatcher)

Albert Ayler — Trio 1964: Prophecy Revisited (Ezz-thetics)

JD Allen — Toys/Die Dreaming (Savant)

Charles Mingus — At Bremen 1964 and 1975 (Sunnyside)

The Warriors of the Wonderful Sound — Soundpath (Clean Feed)

Kidd Jordan/Joel Futterman/Alvin Fielder — Spirits (Silkheart)

Roland Haynes — 2nd Wave (Black Jazz)

Quin Kirchner — The Shadows and the Light (Astral Spirits)

Thelonious Monk — Palo Alto (Universal/Impulse)

Black Unity Trio — Al-Fatihah (Salaam Records/Gotta Groove)

Gary Smulyan — Our Contrafacts (Steeplechase)

Joni Mitchell — Archives Vol. 1: The Early Years (1963-1967 (Rhino)

Elder Charles Beck — Your Man of Faith (Gospel Friend)

Sarhabil Ahmed — King of Sudanese Jazz (Habibi Funk)

V/A – The Right to Rock: The Mexicano and Chicano Rock ‘n’ Roll Rebellion 1955-1963, Episodio Uno (Bear Family)

V/A – Hillbillies in Hell: Country Music’s Tormented Testament (1952-1974) ~ Revelations (The Omni Recording Corporation)

V/A — The Harry Smith B-Sides (Dust to Digital)

#yearend 2020#Dusted magazine#derek taylor#paul desmond#chris dingman#joe mcphee#sonny rollins#stephen riley#sam rivers#james brandon lewis#susan alcorn#john scofield#corbett vs. dempsey#whit boyd combo#robbie basho#jimi hendrix#joe maneri#udi hrant#ayalew mesfin#kent & modern records#a stranger i may be#sun ra#fresh sounds records#sumer is icumenin

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lagerpeton

By Tas

Etymology: Rabbit Reptile

First Described By: Romer, 1971

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Archosauriformes, Eucrocopoda, Crurotarsi, Archosauria, Avemetarsalia, Ornithodira, Dinosauromorpha, Lagerpetidae

Referred Species: L. chanarensis

Status: Extinct

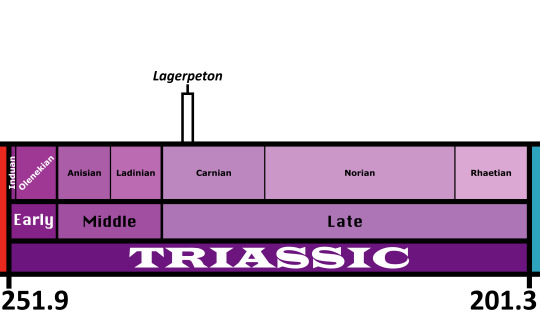

Time and Place: About 235 to 234 million years ago, in the Carnian of the Late Triassic

Lagerpeton is known from the Chañares Formation in La Rioja, Argentina

Physical Description: Lagerpeton was named as the Rabbit Reptile, and for good reason - in a lot of ways, it represents a decent attempt by reptiles in trying to do the whole hoppy-hop thing. You might think that it resembles Scleromochlus in that way, and you’d be right! Scleromochlus and Lagerpeton are close cousins, but one is on the line towards Pterosaurs - Scleromochlus - and the other is on the line towards dinosaurs - Lagerpeton. So, hopping around was an early feature that all Ornithodirans (Dinosaurs, Pterosaurs, and those closest to them) shared. Lagerpeton itself was about 70 centimeters in length, with most of that length represented as tail; it was slender and lithe, built for moving quickly through its environment. It had a small head, a long neck, and a thin body. While it had long legs, it also had somewhat long arms, and while it may have been able to walk on all fours it also would have been able to walk on two legs alone. It was digitigrade, walking only on its toes, making it an even faster animal. Its back was angled to help it in hopping and running through its environment, and its small pelvis gave it more force during hip extension while jumping. In addition to all of this, it basically only really rested its weight on two toes - giving it even more hopping ability! As a small early bird-line reptile, it would have been covered in primitive feathers all over its body (protofeathers), though what form they took we do not know.

By Scott Reid

Diet: As an early dinosaur relative, it’s more likely than not that Lagerpeton was an omnivore, though this is uncertain as its head and teeth are not known at this time.

Behavior: Lagerpeton would have been a very skittish animal, being so small in an environment of so many kinds of animals - and as such, that hopping and fast movement ability would have aided it in escaping and moving around its environment, avoiding predators and reaching new sources of food (and, potentially, chasing after smaller food itself). Lagerpeton may have also been somewhat social, moving in small groups, potentially families, to escape the predators and chase after prey together, given its common nature in its environment. As an archosaur, Lagerpeton was more likely than not to take care of its young, though we don’t know how or to what extent. The feathers it had would have been primarily thermoregulatory, and as such, they would have helped it maintain a constant body temperature - making it a very active, lithe animal.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: Lagerpeton lived in the Chañares environment, a diverse and fascinating environment coming right after the transition from the Middle to Late Triassic epochs. Given that the first true dinosaurs are probably from the start of the Late Triassic, this makes it a hotbed for understanding the environments that the earliest dinosaurs evolved in. Since Lagerpeton is a close dinosaur relative, this helps contextualize its place within its evolutionary history. This environment was a floodplain, filled with lakes that would regularly flood depending on the season. There were many seed ferns, ferns, conifers, and horsetails. Many different animals lived here with Lagerpeton, including other Dinosauromorphs like the Silesaurid Lewisuchus/Pseudolagosuchus and the Dinosauriform Marasuchus/Lagosuchus. There were crocodilian relatives as well, such as the early suchian Gracilisuchus and the Rauisuchid Luperosuchus. There were also quite a few Proterochampsids, such as Tarjadia, Tropidosuchus, Gualosuchus, and Chanaresuchus. Synapsids also put in a good show, with the Dicynodonts Jachaleria and Dinodontosaurus, as well as Cynodonts like Probainognathus and Chiniquodon, and the herbivorous Massetognathus. Luperosuchus would have definitely been a predator Lagerpeton would have wanted to get away from - fast!

By Ripley Cook

Other: Lagerpeton is one of our earliest derived Dinosauromorphs, showing some of the earliest distinctions the dinosaur-line had compared to other archosaurs. Lagerpeton was already digitigrade - an important feature of Dinosaurs - as shown by its tracks, called Prorotodactylus. These tracks also showcase that dinosaur relatives were around as early as the Early Triassic - and that their evolution, and the rapid diversification of archosauromorphs in general, was a direct result of the end-Permian extinction.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Arcucci, A. 1986. New materials and reinterpretation of Lagerpeton chanarensis Romer (Thecodontia, Lagerpetonidae nov.) from the Middle Triassic of La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 23 (3-4): 233-242.

Arcucci, A. B. 1987. Un nuevo Lagosuchidae (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) de la fauna de los Chañares (Edad Reptil Chañarense, Triasico Medio), La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 24: 89 - 94.

Arcucci, A., C. A. Mariscano. 1999. A distinctive new archosaur from the Middle Triassic (Los Chañares Formation) of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19: 228 - 232.

Bittencourt, J. S., A. B. Arcucci, C. A. Marsicano, M. C. Langer. 2014. Osteology of the Middle Triassic archosaur Lewisuchus admixtus Romer (Chañares Formation, Argentina), its inclusivity, and relationships amongst early dinosauromorphs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology: 1 - 31.

Brusatte, S. L., G. Niedzwiedzki, R. J. Butler. 2011. Footprints pull origin and diversification of dinosaur stem lineage deep into Early Triassic. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278 (1708): 1107 - 1113.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2006. A review of the systematic position of the dinosauriform archosaur Eucoelophysis baldwini Sullivan & Lucas, 1999 from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, USA. Geodiversitas 28(4):649-684.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2016. The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriformes. PeerJ 4: e1778.

Fechner, R. 2009. Morphofunctional evolution of the pelvic girdle and hindlimb of DInosauromorpha on the lineage to Sauropoda (Thesis). Ludwigs Maximillians Universita.

Fiorelli, L. E., S. Rocher, A. G. Martinelli, M. D. Ezcurra, E. Martin Hechenleitner, M. Ezpeleta. 2018. Tetrapod burrows from the Middle-Upper Triassic Chañares Formation (La Rioja, Argentina) and its palaeoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496: 85 - 102.

Kammerer, C. F., S. J. Nesbitt, N. H. Shubin. 2012. The first Silesaurid Dinosauriform from the Late Triassic of Morocco. Acta Palaeontological Polonica 57 (2): 277.

Kent, D. V., P. S. Malnis, C. E. Colombi, A. A. Alcober, R. N. Martinez. 2014. Age constraints on the dispersal of dinosaurs in the Late Triassic from magnetochronology of the Los Colorados Formation (Argentina). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 7958 - 7963.

Irmis, R. B., S. J. Nesbitt, K. Padian, N. D. Smith, A. H. Turner, D. T. Woody, and A. Downs. 2007. A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs. Science 317:358-361.

Jenkins, F. A. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VII. The postcranial skeleton of the traversodontid Massetognathus pascuali (Therapsida, Cyondontia). Breviora 352: 1 - 28.

Langer, M. C., S. J. Nesbitt, J. S. Bittencourt, R. B. Irmis. 2013. Non-dinosaurian Dinosauromorphs. Geological Society London, Special Publications. 379 (1): 157 - 186.

Marsh, A. D. 2018. A new record of Dromomeron romeri Irmis et al., 2007 (Lagerpetidae) from the Chinle Formation of Arizona, U.S.A. PaleoBios 35:1-8.

Marsicano, C. A., R. B. Irmis, A. C. Mancuso, R. Mundil, F. Chemale. 2016. The precise temporal calibration of dinosaur origins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of AMerica 113 (3): 509 - 513.

Martz, J. W., and B. J. Small. 2019. Non-dinosaurian dinosauromorphs from the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of the Eagle Basin, northern Colorado: Dromomeron romeri (Lagerpetidae) and a new taxon, Kwanasaurus williamparkeri (Silesauridae). PeerJ 7:e7551:1-71.

Nesbitt, S. J., R. B. Irmis, W. G. Parker, N. D. Smith, A. H. Turner and T. Rowe. 2009. Hindlimb osteology and distribution of basal dinosauromorphs from the Late Triassic of North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29(2):498-516.

Nesbitt, S. J. 2011. The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 353:1-292.

Perez Loinaze, V. S., E. I. Vera, L. E. Fiorelli, J. B. Desojo. 2018. Palaeobotany and palynology of coprolites from the Late Triassic Chañares Formation of Argentina: implications for vegetation provinces and the diet of dicynodonts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 502: 31 - 51.

Rogers, R. R., A. B. Arcucci, F. Abdala, P. C. Sereno, C. A. Forster, C. L. May. 2001. Paleoenvironment and taphonomy of the Chañares Formation tetrapod assemblage (Middle Triassic), northwestern Argentina: spectacular preservation in volcanogenic concretions. Palaios 16: 461 - 481.

Romer, A. S. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. I. Introduction. Breviora 247: 1 - 14.

Romer, A. S. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. II. Sketch of the geology of the Rio-Chañares-Rio Gualo Region. Breviora 252: 1 - 20.

Romer, A. S. 1967. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. III. Two new gomphodonts, Massetognathus pascuali and M. teruggii. Breviora 264: 1 - 25.

Romer, A. S. 1968. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IV. The dicynodont fauna. Breviora 295: 1 - 25.

Romer, A. S. 1969. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. V. A new chiniquodontid cynodont, Probelesodon lewisi - cynodont ancestry. Breviora 333: 1 - 24.

Romer, A. S. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VI. A chiniquodont cynodont with an incipient squamosal-dentary jaw articulation. Breviora 344: 1 - 18.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus. Breviora 373: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IX: The Chanares Formation. Breviora 377: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. X. Two new but incompletely known long-limbed pseudosuchians. Breviora 378:1-10.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XI. Two new long-snouted thecodonts, Chanaresuchus and Gualosuchus. Breviora 379: 1 - 22.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XII. The post cranial skeleton of the thecodont Chanaresuchus. Breviora 385: 1 - 21.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus. Breviora 389: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. Lewisuchus admixtus, gen. et sp. Nov., a further thecodont from the Chañares beds. Breviora 390: 1 - 13.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XV. Further remains of the thecodonts Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus. Breviora 394: 1 - 7.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVI. Thecodont classification. Breviora 395:1-24.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVII. The Chañares gomphodonts. Breviora 396: 1 - 9.

Romer, A. S. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVIII. Probelesodon minor, a new species of carnivorous cynodont; family Probainognathidae nov. Breviora 401: 1 - 4.

Romer, A. S., and A. D. Lewis. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIX. Postcranial materials of the cynodonts Probelesodon and Probainognathus. Breviora 407: 1 - 26.

Romer, A. S. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XX. Summary. Breviora 413: 1 - 20.

Sereno, P. C., and A. B. Arcucci. 1994. Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(1):53-73.

#Lagerpeton#Dinosaurmorph#Lagerpetid#Triassic#Palaeoblr#Triassic Madness#Ornithodiran#Triassic March Madness#South America#Omnivore#Prehistoric Life#Prehistory#Palaeontology#Lagerpeton chanarensis#dinosaur#paleontology#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

TAFAKKUR: Part 430

RIGHT TO FOOD

MORE THAN A BILLION HUMAN BEINGS ON THIS PLANET ARE CHRONICALLY HUNGRY: EVERY 24 HOURS SOME 40,000 DIE DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY FROM LACK OF FOOD; A CHILD STARVES TO DEATH EVERY 2.5 SECONDS. IN SHORT, MORE PEOPLE DIE EVERY TWO YEARS FROM HUNGER THAN WERE KILLED IN THE FIRST AND SECOND WORLD WARS.

Yet, never before has the world produced more food per head of population. While there are places where huge numbers die because they have no crops or no money, there are other places (notably in the West) where the granaries are overflowing with all kinds of foods. While food is stockpiled in some areas, then dumped or wasted in huge quantities in order to maintain price levels, elsewhere, helpless mothers, starving and unable to produce milk, watch their babies die in their arms. Uneven distribution mocks the theoretical sufficiency of global food supply: there should be no world hunger problem but there is (UNO, 1989, p.3).

The ‘world food order’ is a scandal crying out for remedy. It arises within the context of the prevailing economic and political ideologies which are rooted in a crude laissez-faire mentality. According to this mentality, individuals are entitled to absolute ownership over whatever they have acquired lawfully, that is, they have the right to use, to transfer and even to destroy their property (Article 1 of the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966) without being held legally accountable.

It is this mentality, entrenched in law, which prevents the right to food from becoming one of the binding principles of international human rights. Yet, without a right to food, all other human rights are of little value. Once starvation afflicts a people, the very human life for whose sake all human rights are proposed wastes (Alston, 1984, p.4).

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 provides that “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including food…”. Since then, many international documents and most of other normative instruments aiming to secure the right to food of peoples have been agreed upon (Tomasevski, 1987, p.19; see also the 1974 Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition, and the 1986 Food Aid Convention). However, in spite of the enthusiasm and unanimity with which the right to food is endorsed, the amorality of the economic order encourages its constant, continual violation. Measures against world hunger are temporary palliatives in the form of ‘charity’ from governments politically embarrassed by crises (Alston, 1984, p.90).

The impotence of the present world order to eradicate hunger and starvation contrasts sharply with the Islamic world order which enshrines the right to food not only in its ethos but also in its positive laws. To begin with, the Qur’an teaches that all resources are put at the disposal of all human beings by God, the Sustainer. Human beings have no right of absolute ownership, but have right as just trustees (2.30). As God’s vicegerent (khalifah), man is enjoined to deal justly with everyone (not every Muslim) (5.8). To act with justice in the use and management of one’s resources requires the satisfaction of at least the subsistence needs of everyone in society: nothing is more closely connected with the concept of justice than “human rights” (Ahmad, 1991, p.15).

Once the close relationship between justice and human rights is recognized as a fundamental principle, it is a natural next step to base the right to food on the socio-economic teachings of Islam. The aim of the concept of trusteeship (khilafat) is to establish ‘global justice’ in the use of the earth’s natural resources. No discrimination is made between Muslims and non-Muslims, as humanity is a single creation of God, and all have equal right to sustenance from God’s bounty (ni’ma). If one group of the human brotherhood is unable to provide sufficient food to sustain life, for whatever reason, they have a right (haqq) to provision from the wealth of others (Ahmad, 1991, p.17).

The ‘right’ of the hungry is not merely a moral claim; it has a positive, specific counterpart in the corresponding legal obligation to satisfy that right. The authority for this legal obligation is the Qur’an itself whose precepts are binding upon all Muslims (Ahmad, 1991, p.15). The refusal to feed the hungry and to urge the feeding of the hungry is equated with a refusal of religion: Have you observed him who denies religion? That is he who rebuffs the orphan and urges not the feeding of the needy (107.1-3).

In other verses, (e.g. 2.29), the Qur’an specifies that resources be used equitably for the benefit of all mankind (see Chapra, 1992, p207). No people have the right to dump or waste the resources at their disposal in order to manipulate prices (Qur’an 2.205).

The concept of a right to food is explicitly embodied in the teaching and practice of the Prophet, upon him be peace. The civilization of Islam is dated to the Hijrah, the migration to Madina. One of the first measures instituted by the Prophet was to ‘spread peace and distribute food’ (Hamid, 1989, p.l56). He explained that poverty can lead to kufr (ingratitude and rejection of God), and emphasised the link between Muslim solidarity and the right to food: ‘He is not a (true) believer who eats his fill while his neighbour goes hungry’. In another hadith, duty to provide food encompasses animals as well as humans: ‘Whoever brings dead land to life, for him there is a reward in that, and whatever creature seeking food eats of it, shall be considered as charity from him.’ (For other ahadith which clarify the duty to feed and the accountability for failure in it, see Nadvi, 1969 and Ishaque, 1969). The importance of land cultivation in Islamic Law may be gauged from the right of the legitimate authorities to sequester land which is being left idle and apportion it to those who are willing and able to cultivate it: absolute ownership of land is not recognized by the Law.

The right to food is so important in Islamic practice that it is not denied to enemies even in time of siege and war. During the lifetime of the Prophet, upon him be peace, some of his companions blocked the supply of food to Makka, intending to maintain the blockade until Makka surrendered. However, when the hunger of the Quraish was reported to the Prophet he ordered the blockade to be lifted. Following that example, Abu Bakr, the first Caliph, sent Yazid ibn Abu Sufyan on a campaign with the specific instruction that he should not destroy the crops and livestock of the enemy. The same principle is seen in action when the Ottoman army, for example, besieged Vienna, and the city’s poor and sick came to its outskirts to get food from the besieging forces. (What a contrast with the Serbian and Croat militias who are at this time attacking and preventing relief supplies from reaching the Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina with the explicit intention of starving them to death.)

Islamic Law provides for each individual’s basic rights to life and food through zakah and usr, two compulsory annual levies on, respectively the general wealth and the crops and livestock of the better off. Zakah is fixed at one-fortieth and usr at one-tenth of disposable wealth. In the event of the state being unable to meet its commitment to the needy from this revenue, it may compel the rich to give more. The Prophet, upon him be peace, said: ‘God makes it an obligation for the rich of a country to provide for the needs of their poor. Authority must compel them when the resources from zakah are insufficient’. Ibn Hazm and other Muslim savants, on the basis of this hadith, declared that if a person dies of hunger the individual’s neighbourhood is responsible and must pay the bloodwit (diya) by way of atonement (Belkacem, 1979, p.144). (One is bound to reflect how near Somalia is to oil-rich Saudi Arabia.)

Refusal to pay the obligatory levies is equivalent to denying the rights of the needy and a reversion to the values of paganism. Abu Bakr was prepared to go to war in precisely this issue.

Sadaqat al-fitr, a charitable donation made either in money or in kind, at the end of the fasting month of Ramadan, is a further instance, in this case voluntary, of collectively meeting the sustenance needs of the poor.

There is a world of difference between the anthropocentric and egocentric philosophy which has taken such a firm root in the Western mind since the secularization of human rights in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the theocentric ethos of Islam. The latter sees the right to food as a duty, even a debt, owed by those who have a surplus to those who do not have the bare minimum. Further, Islam seeks to establish a social order which recognizes the essential community of all human beings. Without a feeling for that essential community, and a commitment to it in economic transactions, it is hard to see how solidarity can be realized even at a national, let alone an international level. Presenting human beings as objects of ‘charity’ cannot begin to address the problem-for, very soon, the rich become ‘fatigued’ by the demands made upon their compassion and their resources. For people to be dying of famine in a world of plenty, even of excess, is an intolerable scandal and shames us all (Bedjaoui, 1982, p.465). A new ‘world food order’ must be sought as a matter of urgency: if not, the threat of rumbling empty stomachs in Africa and Asia will disturb international peace in the post Cold War era rather more than the threat of nuclear war disturbed it during the Cold War.

#allah#god#prophet#Muhammad#quran#ayah#sunnah#hadith#islam#muslim#muslimah#hijab#help#revert#convert#dua#salah#pray#prayer#reminder#religion#welcome to islam#how to convert to islam#new convert#new muslim#new revert#revert help#convert help#islam help#muslim help

1 note

·

View note

Text

Captain Zap and her Hyperspace Rangers

1988 was the year that the planet Aetheria was liberated at last from the mad Emperor Xerxes, but it was neither the great space hero, Samuel Gerald “Astro” Armstrong, nor his daughter, Samantha Gillespie “Astra” Armstrong, who struck the final, decisive blow.

From 1933 to 1938, Astro Armstrong, Hedy Fine and Dr. Leon Volkov fought for the freedom of the people of Aetheria against the tyranny of Xerxes and his daughter, the wicked Empress Eris.

But in 1959, Astro Armstrong went missing, and in 1966, Astra Armstrong and her mother, Prof. Hedy Feynman, returned to Aetheria after Dr. Leon Volkov’s son, Dr. Leonid Volkov, told them that Astro was still alive, on Aetheria, but captive in the clutches of Xerxes.

As Astro’s family and allies sought to find him again, all while resuming their war with the forces of Xerxes and Eris, they found themselves facing a new foe, the first human ever to join the dark side of the Aetherian Armada, a mysterious masked man known only as Kommissar Blitzkrieg, who somehow seemed capable of anticipating Astra and Hedy at every turn.

By the 1980s, Hedy had begun to suspect the terrible secret of Kommissar Blitzkrieg’s true identity, one that could never be revealed to Astra, which the ruthlessly clinical Prof. Feynman recognized would necessitate the enlistment (or more accurately, the compulsory impressment) of new allies into their struggle, young outsiders with new ways of thinking, whose strengths would draw from their lack of preexisting emotional connections to this star-spanning conflict.

In 1984, the “Hyperspace Pilot” video game had cabinets distributed to the Bits & Blasts Arcade near the edge of the Ned Pines Neighborhood, the Pink Flamingos Mobile Home & RV Park on the outskirts of Eliot’s Expanse, and the Cabaret Cinema in the core of Edwin A. Abbott Square.

Opening in 1922, the Cabaret Cinema remains the oldest continuously operating movie theater in the state of Calizona, its infrequent stints as a Union Gospel Mission location notwithstanding.

The Cabaret Cinema was where a young Valerie Gail Zappa watched nostalgic rescreenings of Saturday matinee serials such as “The Adventures of ‘Astro’ Armstrong," and by the summer of 1984, Val was not only 18 years old and freshly graduated from Stanford S. Strickland Junior High & High School (go Teen Wolves!), but she was also a veteran usher at the Cabaret, where she took in countless classic films for free, and racked up high scores on “Hyperspace Pilot.”

Val and her two-years-younger sister, Tara Moonchild Zappa, lived at their parents’ double-wide at the Pink Flamingos, but like their fellow Pink Flamingos resident Crystal Swan, who was still attending Strickland Junior High in 1984, all three girls were pretty much raising themselves.

Tara had aspirations of enrolling in Beauty’s Beholder Cosmetics & Cosmetology, so she could eventually work at Nagel’s Picture-Perfect Cuts & Colors in the Gold Key Commercial Core.

And while Val’s on-again, off-again boyfriend, Buckminster “Bucky” Martínez, was still sorting through prospective career paths, he’d already earned an athletic scholarship, as a soccer and volleyball player, through Coral Shores Community College (go Atoms!), part of the Calizona Community College Athletic Conference and the National Junior College Athletic Association.

Even Morten Emory Thistlethwaite, the spoiled antisocial prodigy whom Val grudgingly agreed to babysit when she was in junior high, because he was three years her junior, was already on track to attend the University of Calizona, Santa Teresa (go Manticores!), with the Quatermass University of Abstract and Applied Sciences (go Tachyons!) as his designated fallback school.

And yet, Val herself simply drifted, never pursuing a post-secondary education or a long-term occupation beyond what was required to pay for the rent and fun nights out on the town during her weekends off, much to the dismay of her peers and former teachers, all of whom sensed far more potential in her than punching ticket stubs at the Cabaret Cinema, subbing in to lead group workouts at Aphrodite & Adonis Aerobics, or feeding quarters into “Hyperspace Pilot” cabinets.

By 1987, the band of Valerie and Tara Zappa, Bucky Martínez and Morten Thistlethwaite knew they had little enough left in common to wonder aloud why they were still hanging out, but they knew the answer to that as well, since not only had they all remained avid players of “Hyperspace Pilot,” but they’d taken up the next iteration in the franchise, i.e. the “Hyperspace Pistoleer” light-tagging toy guns released in 1986, for which Bits & Blasts had economized its existing space, and even leased adjacent property, to set up a hide-and-seek arena for — among other players — Captain Zap, Brigadier Buckyball, Lieutenant Luna and Master Sergeant Mars, as they preferred to be called on the game clock.

And by the summer of 1987, the band had reasons to celebrate, with Morten’s acceptance for UC Santa Teresa’s fall semester confirmed, Tara feeling confident she would finally be promoted from apprentice to junior stylist at Nagel’s Picture-Perfect Cuts & Colors, and even Bucky finally having settled on a major, after three years, at Coral Shores Community College.

Everyone was heading places, except for Val, who’d always dreamed of travel, but never had the free time or finances to spare, just as her ongoing consumption of classic cinema ensured her lock on the pink-for-entertainment slice of the pie any time she played Trivial Pursuit, and yet, for all her fascination with the film industry, she still couldn’t summon the patience to audition, or even sit still for test shots, for more than sporadic roles as an extra.

“Why does this feel like the end of that made-for-TV movie where roleplaying games drove Tom Hanks crazy?” Tara asked despondently, as the band sat at their regular table in Bits & Blasts, nursing their slices of Pizzazz Pizza.

“You know why,” Val smirked ruefully. “Everyone else is about to embark on grand adventures in bold new campaign settings, while some of us are just destined to ... hang back from the action, and become non-player characters.”

“It doesn’t have to be like this,” Bucky clasped Val’s hand in his own to console her.

“I heard Lis Berger is shutting down the Hyperspace Pistoleer arena after this summer,” Morten blurted out, acutely uncomfortable with the unpleasant emotions his peers were displaying so openly. “Even though it’s still popular, she’s losing a ton of money on it. I say we play one last round now, before it gets torn down.”

Val stood up and laid down a few dollars for the tip. “Might as well go out shooting,” she grinned.

The entry of every officially licensed “Hyperspace Pistoleer” arena was equipped with speakers to play the same opening narration before the players went inside, complete with a flash of light to simulate an interplanetary tesseract:

“As the people of the planet Aetheria cry out for aid, in their fight for freedom against the evil forces of the mad Emperor Xerxes and his Aetherian Armada, a highly trained special mission force has been recruited from the ranks of ordinary humans, right here on Earth, to respond to this call. They are the Hyperspace Rangers, and their brave battles began when they stepped into the Star Point Portal ... and vanished.”

After the obligatory flash of light, Lis Berger’s assistant games supervisor, Rachelle “Ratchet” Chennault, checked the activated “Hyperspace Pistoleer” arena, only to find it empty.

The “Strickland Slackers,” as they came to be branded in subsequent press reports, were gone.

Hedy Feynman knew she had a limited window of time within which to work, because time itself passes on Aetheria at roughly one-seventh the rate that it does on Earth, and because she knew the start of the Harmonic Convergence would commence on Aug. 16, 1987, but even she had failed to grasp how quickly most toy and video game franchises fall out of fashion.

Hedy had commissioned the younger Dr. Leonid Volkov to produce the “Hyperspace Pilot” and “Hyperspace Pistoleer” game lines, as covert training and recruitment tools for what she had envisioned as crack commando units to be branded the “Hyperspace Rangers,” since they would be able to operate not only behind enemy lines, but also between the boundaries that defined both the war and space travel itself.

Because Hedy wished to avoid drawing too much notice, and because she’d retained enough of her conscience not to want to press-gang too many child soldiers into risking life and limb for a cause for which none of them had knowingly consented to sacrifice themselves, the Star Point Portals affixed to the “Hyperspace Pistoleer” arenas absconded with only scattered handfuls of players from her former home planet.

The sustained toll of their secret missions was brutal, culling all but a few of the promising crop Hedy had authorized to transport from Earth during the summer of 1987, but one unlikely band of Hyperspace Rangers somehow not only kept on surviving, but also succeeding in completing their missions, thanks in no small part to the guidance and motivation they drew from the canny strategies and inspiring speeches of their Valkyrie-like leader.

Eventually, the rest of the units were reduced in number enough that their remainders were seconded to Captain Zap and her Hyperspace Rangers.

During the final push to overthrow the misrule of Xerxes, when Astra Armstrong was devastated by the discovery that the merciless Kommissar Blitzkrieg was actually her long-lost father, Astro Armstrong — whose innate heroism had been artificially suppressed by technology the elder Dr. Leon Volkov had been conscripted to create for Xerxes — it was Captain Zap’s Hyperspace Rangers who kept up the pressure on the Aetherian Armada, giving Astra the chance to break through those psychic barriers to reach her real father’s heart, and ultimately redeem his soul.

... And so it was that 1988 was the year that the planet Aetheria was liberated at last from the mad Emperor Xerxes, not by two generations of the same heroic family, but by a third generation of complete strangers to their cause, and yet, even as the rest of the surviving Hyperspace Rangers were returned to Earth per their request, one band asked to stay behind.

Captain Zap, Brigadier Buckyball, Lieutenant Luna and Master Sergeant Mars each had their own reasons for wanting to venture further into the largely uncharted frontier within which they’d found themselves, but Hedy Feynman, as newly elected head of the likewise recently installed government of Aetheria, harbored equally ulterior motives for agreeing to retain their services.

Hedy knew that a tentatively democratic Aetheria, one which was now seeking to atone for the misdeeds of its empire by forging alliances among adversaries, needed free agents to act on its behalf, to make contact with the broader cosmos that Xerxes’ simultaneously expansive and provincial priorities had impacted, and yet also ignored.

Hedy also knew that Astra’s appetite for such crusades had been ground down hard over the course of the war, even before she’d inadvertently unmasked one of her fiercest foes as the vanished father whose legacy she’d sought to live up to her entire life, and for the first time since 1966, Astra found herself missing the old home planet she’d abandoned so casually.

Which was how Astra Armstrong woke up late one morning to the fanfare surrounding the hastily rescheduled launch of the Moebius Loop-powered Cavalry Cruiser-class Unification Searcher Spacecraft (USS) Starlin, the ship she’d simply assumed she would be tasked with commanding, because it had already taken off with its new crew, Captain Zap and her Hyperspace Rangers, without Hedy telling her.

Astra had resigned herself to the likelihood that she would be assigned to provide Captain Zap’s Hyperspace Rangers with essential insights on the various alien species, civilizations and cultures they might encounter, but Hedy had instead sentenced the former Empress Eris to serve as a Hyperspace Ranger, under the command of Captain Zap, as Ensign Eleutherios (”Eleutherios” being the birth name that Eris had always hated), as repayment for her sins.

And with a capable crew protecting the peace in her stead, Astra couldn’t help but smile when Hedy presented her with the Reckless Endeavor, the spaceship with which Astra’s parents and the elder Dr. Volkov had originally traveled to Aetheria, now freshly restored and ready to fly wherever Astra wished.

“First, I’m gonna take a long nap, and then, I’m gonna spend some time doing nothing at all, because I’ve been meaning to do both of those for years,” Astra laughed, even as tears spilled down her cheeks. “After that ... when we left Earth, I was so ready for something so much bigger. The only other gals I knew who wore pants were you, Katherine Hepburn and Laura Petrie on Dick Van Dyke. So much happened, just right after I left.” She chuckled. “It’s like Earth waited until I was gone to get cool.”

“And now?” Hedy brushed the blonde spit-curl from her daughter’s face. “You want to catch up?”

“I want ...” Astra paused, then unclipped the Walkman from her belt loop, that she’d carried to honor all the fallen Hyperspace Rangers, more than one of whom had worn such portable music players into the fray of combat.

Astra cranked the volume on the headphones up to the max, then pressed play, and the voice of Stevie Nicks began to croon:

♫ No one knows how I feel ♪ ♪ What I say, unless you read between my lines ♫ ♫ One man walked away from me ♪ ♪ First he took my hand ♫ ♫ Take me home ... ♪

“I want to go where the music sounds like THAT,” Astra’s voice choked up, as her eyes welled up with fresh unshed tears.

Hedy struggled to keep the quaver out of her own voice, as she squeezed her daughter tight to wish her safe travels. “Then you go there, baby. You go follow the music that’s in your heart.”

#Captain Zap and her Hyperspace Rangers#Captain Zap#Hyperspace Rangers#The Adventures of Astro Armstrong#Astro Armstrong#Astra Armstrong

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When President Franklin Roosevelt signed the GI Bill into law on June 22, 1944, it laid the foundation for benefits that would help generations of veterans achieve social mobility.

Formally known as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the bill made unprecedented commitments to the nation’s veterans. For instance, it provided federal assistance to veterans in the form of housing and unemployment benefits. But of all the benefits offered through the GI Bill, funding for higher education and job training emerged as the most popular.

More than 2 million veterans flocked to college campuses throughout the country. But even as former service members entered college, not all of them accessed the bill’s benefits in the same way. That’s because white southern politicians designed the distribution of benefits under the GI Bill to uphold their segregationist beliefs.

So, while white veterans got into college with relative ease, Black service members faced limited options and outright denial in their pursuit for educational advancement. This resulted in uneven outcomes of the GI Bill’s impact.

Deep knowledge, daily, in The Conversation's newsletter

Sign up

As a scholar of race and culture in the U.S. South, I believe this history raises important questions about whether subsequent iterations of the GI Bill are benefiting all vets equally.

Tuition waived for service

When he signed the bill into law, President Roosevelt assured that it would give “servicemen and women the opportunity of resuming their education or technical training … not only without tuition charge … but with the right to receive a monthly living allowance while pursuing their studies.” So long as they had served 90 consecutive days in the U.S. Armed Forces and had not received a dishonorable discharge, veterans could have their tuition waived for the institution of their choice and cover their living expenses as they pursued a college degree.

This unparalleled investment in veteran education led to a boom in college enrollment. Around 8 million of the nation’s 16 million veterans took advantage of federal funding for higher education or vocational training, 2 million of whom pursued a college degree within the first five years of the bill’s existence. Those ex-service members made up nearly half of the nation’s college students by 1947.

Colleges scrambled to accommodate all the new veterans. These veterans were often white men who were slightly older than the typical college age. They sometimes arrived with wives and families in tow and brought a martial discipline to their studies that, as scholars have noted, created a cultural clash with traditional civilian students who sometimes were more interested in the life of the party than the life of the mind.

Limited opportunities for black servicemen

Black service members had a different kind of experience. The GI Bill’s race-neutral language had filled the 1 million African American veterans with hope that they, too, could take advantage of federal assistance. Integrated universities and historically Black colleges and universities – commonly known as HBCUs – welcomed black veterans and their federal dollars, which led to the growth of a new black middle class in the immediate postwar years.

Yet, the underfunding of HBCUs limited opportunities for these large numbers of Black veterans. Schools like the Tuskegee Institute and Alcorn State lacked government investment in their infrastructure and simply could not accommodate an influx of so many students, whereas well-funded white institutions were more equipped to take in students. Research has also revealed that a lack of formal secondary education for Black soldiers prior to their service inhibited their paths to colleges and universities.

As historians Kathleen J. Frydl, Ira Katznelson and others have argued, U.S. Representative John Rankin of Mississippi exacerbated these racial disparities.

Racism baked in

Rankin, a staunch segregationist, chaired the committee that drafted the bill. From this position, he ensured that local Veterans Administrations controlled the distribution of funds. This meant that when black southerners applied for their assistance, they faced the prejudices of white officials from their communities who often forced them into vocational schools instead of colleges or denied their benefits altogether.

Mississippi’s connection to the GI Bill goes beyond Rankin’s racist maneuvering. From 1966 to 1997, G.V. “Sonny” Montgomery represented the state in Congress and dedicated himself to veterans’ issues. In 1984, he pushed through his signature piece of federal legislation, the Montgomery GI Bill, which recommitted the nation to providing for veterans’ education and extended those funds to reserve units and the National Guard. Congress had discontinued the GI Bill after Vietnam. As historian Jennifer Mittelstadt shows, Montgomery’s bill subsidized education as a way to boost enlistment in the all-volunteer force that lagged in recruitment during the final years of the Cold War.

Social programs like these have helped maintain enlistment quotas during recent conflicts in the Middle East, but today’s service members have found mixed success in converting the education subsidies from the Post-9/11 GI Bill into gains in civilian life.

This new GI Bill, passed in 2008, has paid around $100 billion to more than 2 million recipients. Although the Student Veterans for America touts the nearly half a million degrees awarded to veterans since 2009, politicians and watchdogs have fought for reforms to the bill to stop predatory, for-profit colleges from targeting veterans. Recent reports show that 20% of GI Bill disbursements go to for-profit schools. These institutions hold reputations for notoriously high dropout rates and disproportionately targeting students of color, a significant point given the growing racial and ethnic diversity of the military.