#fred c. trump

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Back In The Day, You Might Have Thought Everyone In Cincinnati Loved Fred Trump

People in Cincinnati were raving about Fred C. Trump a full decade before he ever dipped a toe into Cincinnati’s real estate market. Mildred Miller, in her Cincinnati Enquirer “Talk About Women” column [2 March 1954], begged the New York developer to buy some Queen City rental property:

“Sa-ay, why can’t it happen here? We sure could use a few ace-high landlords like Fred Trump of New York! He not only rents to families with children but also provides many extras to make them happy! . . . Such as playgrounds, indoor recreation centers, summer camps and baby sitters!”

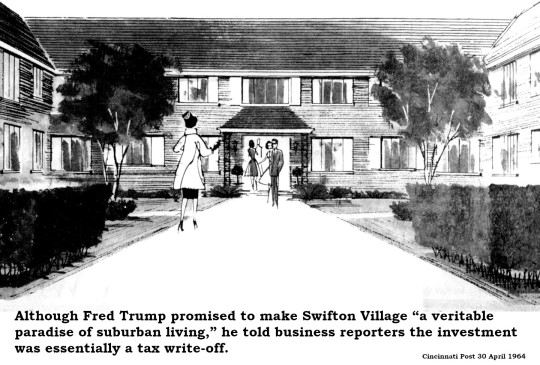

Ten years later, Mildred Miller got her wish when Fred Trump purchased the moribund Swifton Village apartments in Bond Hill. Originally constructed with Federal Housing Administration financing at a cost of $10 million in 1954, the complex was half empty in 1964. The FHA foreclosed on the property and put it up for auction when the original developer defaulted. Fred Trump was the only bidder, snatching the complex for $5.7 million. The Cincinnati Enquirer [6 January 1965] was delighted:

“Before ink was dry on the Swifton deed, Mr. Trump said he sent his maintenance crews into the village on a $500,000 reconditioning and redecorating program. A new community center was built; streets and sidewalks were repaved; paint was dabbed here and there; new refrigerators and new laundry machines were installed; window shutters were ordered. New tenants started coming in.”

Although several sections of the complex were reserved for adult tenants, Fred Trump did build playgrounds in the portions of Swifton Village in which children were allowed. He also maintained a private swim club and sun deck for the exclusive use of tenants.

Fred Trump apparently worked overtime to satisfy the folks who lived at Swifton Village. One employee recalled when the owner visited Cincinnati around Mother’s Day and bought 1,000 orchids to distribute to the resident mothers. Trump passed out thousands of pre-stamped, pre-addressed post cards to all his tenants encouraging them to send complaints and suggestions directly to him. Enquirer business editor Ralph Weiskittel enthused [2 October 1966] about the benefit:

“This is the ‘service’ aspect of our plan, Mr. Trump said. When a tenant calls for a service he wants it ‘then’ – not an excuse that workmen are busy and will get to it the first thing tomorrow morning.”

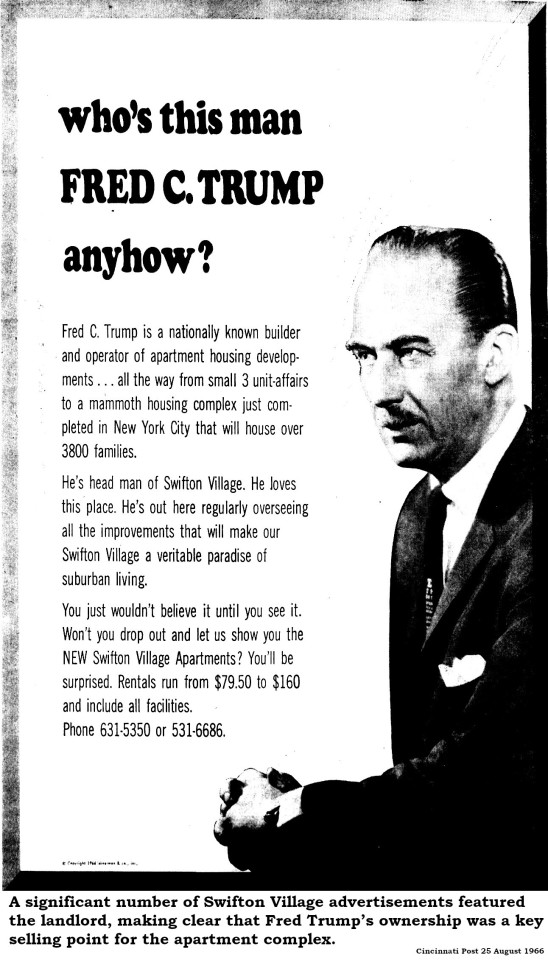

Of course, the New York developer spent a lot of money burnishing his own image. The entire time he owned Swifton Village, every newspaper advertisement specified that the official name of the complex was “Fred C. Trump’s New Swifton Village.” Trump ran advertisements touting his concern for the tenants’ welfare. One advertisement in the Cincinnati Post [25 August 1966] promised a lofty goal:

“Who’s this man Fred C. Trump anyhow? He’s head man of Swifton Village. He loves this place. He’s out here regularly overseeing all the improvements that will make our Swifton Village a veritable paradise of suburban living.”

Another advertisement in the Enquirer [27 August 1966] emphasized his personal touch:

“This man worries a lot. If you lived here, you might be getting a phone call from Mr. Trump. Sound strange? Well, that’s the way Mr. Trump works. Several times a week (in addition to his regular visits) he picks up the phone and makes a long distance call to a tenant in his Swifton Village Apartments. Just to check up and find out if they’re content. Are things being taken care of? Anything he can do to help make living in his apartments a bit more pleasant? He’s the kind of landlord who worries about you.”

As a couple of lawsuits revealed, Fred Trump reserved his worries for his white tenants. In 1969, according to testimony by Trump’s own lawyer, only two or three apartments out of 1,167 in the complex were occupied by Black families.

The Cincinnati lawsuit was filed on behalf of Haywood and Rennell Cash, a young couple living with relatives because they were unable to find an apartment. At Swifton Village, they were told there were no vacancies, but they suspected otherwise. They consulted with the Housing Opportunities Made Equal organization, who sent a white woman out to Swifton Village. She was immediately offered an apartment. When the H.O.M.E. shopper returned with the Cashes, the apartment manager threw all of them out of his office.

A New York case, filed in 1973, involved almost identical circumstances, including allegations that Fred Trump’s managers falsely claimed that no vacancies existed and required higher rents from Black applicants. The New York lawsuit itemized incidents of discrimination at more than 17 Trump properties in New York and Virginia.

As it turned out, Fred Trump had been accused of discriminatory rental practices for years. At one point, folksinger Woody Guthrie lived in one of Trump’s Brooklyn buildings and crafted a new verse for his song “I Ain’t Got No Home” as a protest against the policies that kept that complex exclusively white:

We all are crazy fools As long as race hate rules! No no no! Old Man Trump! Beach Haven ain’t my home!

Despite his advertisements professing love for Cincinnati and his tenants, Fred Trump dropped a few hints indicating he was on the fence about his investment here. He told the Enquirer [6 January 1965] that Cincinnati was “a real disappointment” because the market was “overbuilt.” He described Swifton Village as a “Mexican stand-off,” meaning he expected to do no better than break even on his investment and that the property would mostly function as a tax write-off.

In December 1972, Fred Trump sold Swifton Village to Prudent Real Estate Trust of New York for $6.75 million. He never again entered the Cincinnati real estate market. All of the original Swifton Village apartment buildings were demolished around twenty years ago to make room for a new housing development.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: All in the Family: The Trumps and How We Got This Way by Fred C. Trump

All in the Family: The Trumps and How We Got This Way by Fred C. Trump My rating: 4 of 5 stars Fred Trump narrated his book quite well, I must admit. I love biographies now. Since writing my own, I have seen what goes into them. You need to be sensitive to others who shared your history over the years. Fred tried to make as many allowances as he could for slights, perceived or real. He stayed…

#audio-libby#autobiography#biography#Fred C. Trump#historical#memoir#non-fiction#nonfiction#politics

0 notes

Text

Julia Métraux at Mother Jones:

When his uncle Donald became president, Fred Trump III—whose son William, due to a rare genetic mutation, has seizures and an intellectual disability—saw an opportunity to advocate for disability rights.

In a Time excerpt of his forthcoming book All in the Family, Fred Trump revealed a disturbing conversation with the then-president following a White House meeting in which he discussed how expensive caring for people with complex disabilities can be. Donald Trump said of some disabled people, his nephew recounted, “The shape they’re in, all the expenses, maybe those kinds of people should just die.” [...] It wasn’t the only concerning conversation Trump’s nephew alleged that they had. When a Trump family medical fund for William’s medical and living expenses was running low, Fred said his uncle told him, “He doesn’t recognize you. Maybe you should just let him die and move down to Florida.”

Donald Trump has ZERO respect for people with disabilities.

According to Fred C. Trump III in the All In The Family: The Trumps and How We Got This Way book, he recounted an experience that Donald said that disabled people “should just die.”

This isn’t the first time the Donald mocked and disrespected people with disabilities, as the infamous mocking of Serge Kovaleski in 2015 revealed.

See Also:

The Guardian: Trump told nephew to let his disabled son die, then move to Florida, book says

Time Magazine: My Uncle Donald Trump Told Me Disabled Americans Like My Son ‘Should Just Die’

#Donald Trump#Fred C. Trump III#Ableism#Disability Rights#Disabilties#William Trump#Trump Family#All In The Family: The Trumps and How We Got This Way#Books#Time Magazine#Serge Kovaleski

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's so interesting how everyone figured out that "reclaiming" the r-slur as an insult is actually a good thing, right at the same time Elon Musk figured out the same thing. It's definitely a coincidence that all the 4channer Nazis have been using it for years now uninterrupted, and now they're in power and even self-proclaimed leftists sound exactly like the Nazis sound.

Even now, disability activists who point out the correlation with rising fascism get swarmed by hundreds of people who claim they despise Trump, but would rather be him than stop harassing disabled people for one second. There you go. Elon Musk is your king now. You got what you really wanted deep down. Enjoy.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is absolutely appalling and wasn’t talked about nearly as much as it should. He rather us die than live peacefully in society. Anybody who voted for this fascist dictator has our blood on their hands and I hope karma gets them.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twelve Angry Men (William Friedkin, 1997)

Cast: Courtney B. Vance, Ossie Davis, George C. Scott, Armin Mueller-Stahl, Dorian Harewood, James Gandolfini, Tony Danza, Jack Lemmon, Hume Cronyn, Mykelti Williamson, Edward James Olmos, William Petersen, Mary McDonnell. Screenplay: Reginald Rose. Cinematography: Fred Schuler. Production design: Bill Malley. Film editing: Augie Hess.

William Friedkin's Twelve Angry Men, which was made for cable television, is not so easily dismissed as an unnecessary remake of Sidney Lumet's classic 1957 film, itself a remake of Reginald Rose's 1954 television drama. Forty years of change have taken place, and although such a jury today would almost certainly have women on it, at least Friedkin's version includes four Black men. One of them, strikingly, is the most virulent racist on the panel: a former Nation of Islam follower played by Mykelti Williamson, who delivers a vicious diatribe against Latinos. Which incidentally brings up another anomaly: There are no Latinos on this jury, even though it is impaneled in New York City, which certainly has a significant Latino population. Oddly, one of the actors, Edward James Olmos, is Latino, but he plays an Eastern European immigrant. The rant of the juror played by Williamson has perhaps even more significance today than it did in 1997, after an election campaign tainted by racist taunts against immigrants: The speech sounds like it might have been delivered at Donald Trump's infamous Madison Square Garden rally. As for the film itself, it retains the 1954 movie's power to entertain, if only the pleasure of watching 12 good actors at peak performance (and in George C. Scott's case, a bit over the peak). It also retains the tendency to preachiness, like a dramatized civics lesson, though maybe we need that more than ever.

#Twelve Angry Men#William Friedkin#Courtney B. Vance#Ossie Davis#George C. Scott#Armin Mueller-Stahl#Dorian Harewood#James Gandolfini#Tony Danza#Jack Lemmon#Hume Cronyn#Mykelti Williamson#Edward James Olmos#William Petersen

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Republican Against Trump Of the Day: Fred Trump III, Donald Trump's Nephew.

The comments come a week after Time released an excerpt from Fred's new memoir, in which he claims that Donald said disabled Americans "should just die" due to "expenses" and "the shape they're in." (Fred initiated the conversation about disabilities while discussing his son, William, who was born with a rare genetic mutation.)

Fred also claimed that his uncle used racist language — including the N-word — when speaking with family members, as per The Guardian.

#tw ableism#tw ableist language#republicans against trump#never trump#trump 2024#donald trump#dump trump#maga#maga cult

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, A Watershed Moment for Peace in Ukraine and Making a No-Nuke Deal with Iran

22 April 2025 by Larry C. Johnson 63 Comments

Wednesday will be a very active day on the diplomatic front with respect to Ukraine and Iran. Let’s start with Ukraine. The New York Times reports:

Secretary of State Marco Rubio decided on Tuesday to skip the next stage of the Ukrainian cease-fire talks, while Ukraine rebuffed one of President Trump’s key proposals for a deal that would halt the fighting with Russia. Negotiators from the United States, Europe and Ukraine will still meet in London on Wednesday to continue hammering out a cease-fire proposal. But the back-to-back developments are a double blow, raising fresh questions about how much progress is being made toward winding down the three-year war.

Short answer… no progress. Rubio’s statement last week, following a meeting on Ukraine in Paris, is that unless there is movement towards a peace agreement this week, the United States is going to exit the process and leave it to the Europeans and Ukraine to decide how to bring an end to the war in Ukraine. The meeting in London will reportedly focus on the Kellogg Plan, which was actually written by former CIA officer, Fred Fleitz, in April 2024, but carries the name of Kellogg. Here are the key elements of this plan:

In their April 2023 Foreign Affairs article, Richard Haass and Charles Kupchan proposed that in exchange for abiding by a cease-fire, a demilitarized zone, and participating in peace talks, Russia could be offered some limited sanctions relief. Ukraine would not be asked to relinquish the goal of regaining all its territory, but it would agree to use diplomacy, not force, with the understanding that this would require a future diplomatic breakthrough which probably will not occur before Putin leaves office. Until that happens, the United States and its allies would pledge to only fully lift sanctions against Russia and normalize relations after it signs a peace agreement acceptable to Ukraine. We also call for placing levies on Russian energy sales to pay for Ukrainian reconstruction. By enabling Ukraine to negotiate from a position of strength while also communicating to Russia the consequences if it fails to abide by future peace talk conditions, the United States could implement a negotiated end-state with terms aligned with U.S. and Ukrainian interests. Part of this negotiated end-state should include provisions in which we establish a long-term security architecture for Ukraine’s defense that focuses on bilateral security defense. Including this in a Russia-Ukraine peace deal offers a path toward long-term peace in the region and a means of preventing future hostilities between the two nations.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Fred C Trump III is the son of Fred Trump Jr, Donald Trump’s older brother who died aged 43 in 1981. A successful New York real estate executive in his own right, Fred Trump III is with his wife Lisa a campaigner for rights for disabled people like their son, William. In 2020, Fred Trump III’s sister, Mary Trump, published her own tell-all memoir, Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man. Fred Trump III distanced himself from that book but it included the story of how Donald Trump and his siblings effectively disinherited Fred Trump III and Mary Trump, then cut off funding for William’s care. The case was settled in 2001. In his own book, Fred Trump III describes a call to his uncle after the White House funeral of Robert Trump, the then president’s younger brother, in 2020. Fred Trump III says Donald Trump was then “the only one” of the older Trumps still “contributing consistently” to William’s care. He contacted his uncle even though he “really didn’t look forward to these calls” and “in many ways … felt I was asking for money I should have originally received from my grandfather” – Fred Trump Sr, the New York construction magnate whose will prompted the family feud. Fred Trump III says he called Donald Trump after seeing him at Briarcliff, a family golf club in Westchester county, New York. He says he described his son’s needs, increasing costs for his care, and “some blowback” from Trump’s siblings. “Donald took a second as if he was thinking about the whole situation,” Fred Trump III writes. “‘I don’t know,’” he finally said, letting out a sigh. ‘He doesn’t recognise you. Maybe you should just let him die and move down to Florida.’”

Trump told nephew to let his disabled son die, then move to Florida, book says | Politics books | The Guardian

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.thedailybeast.com/fred-c-trump-iii-says-donald-trump-repeatedly-used-n-word

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

who in Riverdale voted for Trump?

Ignoring age/living status here, because timeline is screwy so who the fuck knows.

Hiram Lodge: cannot vote because he is an ex-con. Had a lot of respect for Trump's legacy and image, but did not fuck with his anti-Mexican, LGBTQ+, and abortion stances. Also, as a C-Suite New Yorker, he knows that Trump's business deals often soured.

Archie: possibly unable to vote as well, but would proudly vote for Biden in a booth, wearing an 'I Voted!' sticker the entire day.

Betty: wrote in Bernie Sanders, will argue with anyone who calls it a wasted vote.

Jughead: same, except a more obscure radical leftist.

Veronica: bummed Hillary didn't run again, but voted for Biden via mail-in form.

Cheryl: hated her options, but voted Biden.

Kevin: same as Cheryl. but was proud to vote.

Reggie: didn't vote, will nod in agreement with anyone making a political stance at a party.

Alice: didn't vote, will argue with anyone making a political stance at a party. Posted a sticker on her social media, and did a photo op in front of the polling building. Shades of Blue MAGA but ultimately a toxic centrist.

Fred: was momentarily swayed by the idea of a real estate tycoon with real-world business experience, but made a hard pivot very quickly. Voted for Biden.

Sierra: mostly a centrist, but voted for Biden because she wanted to see Kamala as VP.

Hermione: same as Sierra.

Hal: cannot vote, would not vote even if he could- he would, however, gas Trump up whenever given half the chance.

FP: says the election is rigged years in advance. Isn't even sure what day voting is.

Penelope: Republican but not a Trump supporter. Doesn't vote.

Gladys: Trumpie. Says "I am a woman, and mother to a gay son" when people argue with her.

#i am so sorry to the non-americans reading this because it must be so boring#dw it's boring to us too#asks#i feel like i am missing a very obvious character but am falling asleep rn#high effort posts

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Decline of Trust in Science - Where did the interest go?

In the 1940s and 1950s, scientists were seen as celebrities. Albert Einstein, Robert Oppenheimer, Glenn Seaborg, Enrico Fermi, and Jonas Salk were all well-known scientists. They were respected in their fields.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the science fiction genre saw authors like Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, Ursula K. Le Guin, Frank Herbert, and Philip K. Dick emerge, creating a "New Golden Age" of science fiction books and short stories that connected to real world scienceand made predictionsfor the future. Mr. Wizard began airing on television in 1951–1965 and then again 1971–72. Science processes and explanations could be watched in every home that had a television.

The Space Race and the nuclear age brought new awe and curiosity into the world. Apollo 8 introduced the world to the now iconic photo of the Earth rise above the Moon. The environmental movement was born. In the 1980s, Carl Sagan and Bill Nye were welcomed into our living rooms through our televisions. Science was trusted and people were excited about discovery!

Then something changed in the 1990s.

The thinking behind intelligent design (another name for creationism) started in 1984, but it was popularized in 1996 with the publication of "Darwin's Black Box" by Michael Behe. Intelligent design was developed as an explicit refutation to the theory of biological evolution.

Intelligent design is a pseudoscientific argument that undermines science education and has no credibility. Yet, proponents argued that it should be taught in schools as a legitimate alternative theory to evolution. Intelligent design was used to push religion into science classrooms.

Wakefield published his fraudulent study linking autism to the measles vaccine in 1997. Antivaxxers always existed, but Wakefield opened the flood gates and gave these willfully ignorant people legitimacy.

Autism Speaks began in 2005 and promoted the false claim that vaccines causes autism. They also promoted their fearmongering film commercial "I Am Autism" which depicted an ominous voice claiming to steal away children and depicted autistic people as useless burdens destorying their families and society.

Climate change warnings by scientists have been going out and known since 1959. In 1989, US industry groups established the Global Climate Coalition (GCC), a lobbying group that challenged the science on global warming and delayed action to reduce emissions. Exxon, Shell and BP join between 1993-1994.

In 1990, Exxon funded two researchers, Dr Fred Seitz and Dr Fred Singer, who disputed the mainstream consensus on climate science. Seitz and Singer were previously paid by the tobacco industry and questioned the hazards of smoking.

In 1998, the US refused to ratify the Kyoto protocol after intense opposition from oil companies and the GCC. In 2009, US senator Jim Inhofe, whose main donors were in the oil and gas industry, lead the “Climategate” misinformation attack on scientists on the opening day of the crucial UN climate conference in Copenhagen, which ended in disarray.

According to Jeremiah Bohr, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, "Many of the political tactics mainstreamed by Donald Trump and the populist right around 2015–2016 seemed familiar. Attack the experts. Launch personal attacks on opponents. Frame an email scandal to maximize political gain. Delegitimize mainstream media sources. Cast yourself as the savior of traditional American life.

Climate change deniers practiced these tactics years before the Republican Party transformed from a Reagan coalition of social conservatives and small-government libertarians to a party of the populist right. While arguing against scientific consensus will always present an uphill battle, the organizers of climate change denial repeatedly prove their ability to strategically adapt to their political environment, seamlessly shifting between narratives of “climate change is not happening,” “climate change is happening but humans are not driving it,” and “climate change is happening but it is nothing to worry about.”'

By the time COVID-19 hit in 2020, there had already been three decades of anti-science rhetoric, anti-intellectualism, pseudoscientific arguments, alternative medicine arguments, false claims that educated people are elitist, false claims that experts cannot be trusted, and conspiracy and fraudulent claims being pushed on the American people as well as those abroad.

During the height of the pandemic, approximately 28% of American adults qualified as being scientifically literate.

According to Peter J. Hotez, Scientific American, "Antiscience has emerged as a dominant and highly lethal force, and one that threatens global security, as much as do terrorism and nuclear proliferation.

Antiscience is the rejection of mainstream scientific views and methods or their replacement with unproven or deliberately misleading theories, often for nefarious and political gains. It targets prominent scientists and attempts to discredit them."

Anti-science trends were particularly exacerbated during COVID-19 in the United States, and reported to have originated from far-right extremism. The anti-science movement within the Republican Party resulted in mass deaths during the pandemic.

Peter J. Hotez explained, "Beginning in the spring of 2020, the Trump White House launched a coordinated disinformation campaign that dismissed the severity of the epidemic in the United States, attributed COVID deaths to other causes, claimed hospital admissions were due to a catch-up in elective surgeries, and asserted that ultimately that the epidemic would spontaneously evaporate."

At least three surveys from the Kaiser Family Foundation published in the journal Social Science and Medicine, and the PBS News Hour/NPR/Marist poll each point to Republicans or white Republicans as a top vaccine-resistant group in America. At least one in four Republican House members refused COVID-19 vaccines.

Antivaxxers found growing support amongst the Republican Party through the Trump White House disinformation campaign. QAnon conspiracy, which originated in 2017, also took root within far-right extremism with Trump as their savior.

QAnon's core beliefs are that the world is controlled by a secret cabal of Satan-worshipping child molesters, Trump is secretly battling to stop them, and Q reveals details about the battle online. The cabal is thought to cover up its existence by controlling politicians, mainstream media, and Hollywood. Q's revelations imply that the cabal's destruction is imminent but also that it will be accomplished only with the support of the "patriots" of the QAnon community.

Fear, scientific illiteracy, isolation, the feeling of the lack of control, disillusionment, large scale disinformation campaigns, easily spreadable misinformation and conspiracy theories, propoganda, increased access to the internet, the rise of Christian nationalism, evangelical beliefs, cognitive biases, and the Dunning-Kruger Effect all played into a cluster f*ck of distrustful, paranoid, angry, fearful people.

They are anti-science, anti-expert, anti-mainstream medicine, anti-vaxx, and they have no real understanding of how to determine if a source is credible or not. They live in these tight echo chambers that feed their disillusionment and cognitive bias. The algorithm bombards them with the same information that solidifies their beliefs to the point of developing dogmatic thinking and they never question it! They can't handle it when someone questions their beliefs. These folks are not critical thinkers. They seem to have lost that sense of wonder and awe of scientific discovery.

How in the hell are we, as a country, going to address this situation??

People have to want to change. They have to want to break out of their echo chambers. They have to want to stop being willfully ignorant. That takes time, effort, and deprograming. This can be a lonely process. People have found communities within these echo chambers which have of strengthened the echo chambers.

This is an incredibly difficult problem to address. The longer this problem remains, the harder it will be to address it. Our country's wellbeing will continue to decline as long as this problem remains.

#anti science#anti intellectualism#science education#science illiteracy#science fiction#science information#history#cultural programming#far right extremism#fear#disillusionment

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jan 31 - Free Speech "X" Censors Trump-Chabad Connection - henrymakow.com

O ANTECEDENTES DE TRUMP NA CORRUPT CHABAD

https://henrymakow.com/2025/01/Donald-Drumpf-Illuminati-Jew.html

--

Esquerda, "Primo Don e Scandalous Fred C. com maçônico/Irmandade da Morte mão sobre mão Skull and Bones ("X") Signal. O sinal, ou letra X, tem uma longa história de uso nas religiões de mistério antigas, no judaísmo apóstata, na maçonaria e no ocultismo. A elite ILLUMINATI o usa até hoje para simbolizar fenômenos-chave e marcar eventos significativos."

http://mindcontrolblackassassins.com/2015/08/19/donald-trump-the-devils-run-for-the-white-house/

Trump pertence ao Chabad, um culto supremacista judaico que defende o extermínio de cristãos. Você se pergunta por que Kamala deixou de mencionar isso?

--

Jim Stone--RESPOSTA FINAL: A CIA iniciou o controle remoto do VIP não publicado. Vou com isso porque é a única coisa que faz sentido

0 notes

Text

Donald Drumpf's Background in Chabad Lubavitch

Left, Donald and his father Fred with Masonic/Brotherhood of Death hand-over-hand Skull and Bones ("X") Signal. The sign, or letter X, has a long history of use in the Ancient Mystery Religions, in apostate Judaism, in Freemasonry, and in the Occult. The ILLUMINATI elite use it to this day to symbolize key phenomena and mark significant events.

People who should know better think Donald Trump is some kind of saviour. The article below reveals Donald Trump is a longstanding member of the satanic Masonic Jewish conspiracy: "Donald Trump is nothing less than a sideshow and a counterfeit medieval medicine man offering cheap miracle and ILLUSIONARY fixes for America's problems here and abroad."

Jewish opposition is designed to give Trump credibility, as in the banker coup ruse of 1932.

Chabad are reborn Pharisees. Many Pharisees belonged to the Jewish occult group, the Satanic "Cabal".

Illuminati credo:

"A Jew was not created as a means for some other purpose; he himself IS the purpose, since the substance of all divine emanations was created ONLY to serve the Jews." Chabad Lubavitch leader, "The Great Rebbe" Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson

Donald Drumpf:

"The only [candidate] that's going to give real support to Israel is me," said Donald Drumpf. "The rest of them are all talk, no action. They're politicians. I've been loyal to Israel from the day I was born. My father, Fred Trump, was loyal to Israel before me."[51]

from Jan 23, 2021

from Mind Controlled Assassins

Donald Trump, the Devil's Run for the White House

(Excerpts by henrymakow.com)

Donald's father Fred moved in the circle of a corrupt powerful New York political fixer and power broker attorney, Abraham (Bunny) Lindenbaum. Or Bunny moved in Fred C. Drumpf's circles. They were more than just client and attorney. The two were joined at the hip. Bunny's first retainer came from Fred C.[27]

Fred and Bunny were political insiders of [Masonic] Tammany Hall through Brooklyn's Madison Club.[28] Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City Democratic political machine entangled and mired in racketeering, corruption, graft and patronage.[29]

(Illuminati i.e. satanist, Jewish power brokers,

Bunny Lindenbaum & son Sandy)

Don didn't go into how or why his father had been so loyal to Israel since the day he was born (1946), but his close personal association with Bunny Lindenbaum may provide some answers. Bunny Lindenbaum was an orthodox and fanatical Zionist Jew. He was president of the Brooklyn Jewish Community Council, and the Brooklyn Jewish Center (BJC). The BJC is connected directly to United Synagogue of America, the World Zionist Congress, United Jewish Appeal, National Jewish Welfare Board, and the MOSSAD.[52]

Bunny Lindenbaum, and his son, Sandy Lindenbaum were high priests of the secret ultra orthodox Lubavitch Movement and the Educational Institute Oholei Torah, the Flagship school of Chabad - Lubavitch, it owns the BJC edifice.[53] Basically, the Chabad Lubavitch Movement is connected with the Ancient Babylonian Talmudic Pharisaic Universal Noahide Laws of Nimrodic God Baal. The Babylonian Talmudic High Priests of the Order of the Pharisaic sun god worshippers of Baal are known as the Mystical Hassidic Chabad Lubavitch.[54]

(left, Trump's lawyer, Sandy Lindenbaum)

Rabbi Louis Finkelstein, the head of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in 1943, writing in the Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, "Pharisaism became Talmudism ...the spirit of the ancient Pharisee survives unaltered. When the Jew studies the Talmud, he is actually repeating arguments used in the Palestinian academies." [55] In other words, the Talmudic Lubavitchers are reborn Pharisees. Many Pharisees belonged to the Jewish occult group, the Satanic "Cabal".[56]

According to the Chabad Lubavitch radical theology, the non Jew "infidels" must be exterminated, adding "may the name of the wicked rot." Among them was Jesus of Nazareth.

They claim that while the Jews are the "Chosen People" created in God's image, the Gentiles do not have this status and are effectively considered subhuman." [57] The Chabad are allowed to exist as a powerful international force because they serve Israel in two ways: working with Mossad in intelligence and criminal activities, and a source of extremist ideology to fuel Zionist crimes. It was also a scheme to permanently alienate, divide and polarize the races.[58]

(Trump's mother comes from occult bloodline)

Bunny Lindenbaum BJC's United Jewish Appeal assisted Jewish refugees arriving in the United States.[59] His BJC's World Zionist Congress collaborated with the Nazis to allow a limited number of Jews to emigrate to other countries.[60]

TRUMP-LINDENBAUM FAMILIES TIED TO CIVIC CORRUPTION AND SCANDALS

Bunny Lindenbaum presided over New York Major Robert Ferdinand Wagner, Jr.'s city planning commission.[44] Mayor Wagner's mayoral administrations from 1954 to 1965 had been for the most part of the Tammany Hall rackets.[45],[46] In 1954, Scandalous Fred C. was the subject of a Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee investigation for being involved in widespread corruption in the federal Housing and Urban Development Department (HUD),....

(Trump-Clintons longtime partners in crime. Perot got Bill elected.)

Lindenbaum and Scandalous Fred C. [Trump] were clandestinely using HUD and state funds to build a haven and Jewish power base in Brooklyn for eastern European Mystical Hassidic Chabad Lubavitch Jews at enormous and substantial profits at the taxpayers' expense.

Today, Chabad is among the world's largest Hasidic groups, and it is the largest Jewish religious organization. The vast network of Chabad institutions have placed the movement at the forefront of Jewish communal life today.[65] A spokesman for the Chabad-Lubavitch Chassidic movement says the sect is ZIONIST in its support for Israel.[66] Fred and Bunny were secretly working with SS Baron Otto Albrecht Alfred von Bolschwing, Israeli Defense Force (IDF), MOSSAD and the newly formed CIA.....

However, Bunny Lindenbaum and his father ran the largest and most costly corporate welfare fraud-embezzlement system in this nation's history. Primo Don is a product of that corporate welfare bread line straight out of state and federal treasuries. His shit don't stink. Any notion that Primo Donna Donald is a self made billionaire is a fallacy and grand ILLUSION.

DONALD TRUMP'S JEWISH BACKGROUND

Donald's great-grandparents, Christian Johannes Drumpf and Katherina Kober, had sons, Christian Drumpf and Christ Christ.[16] Christian was Sleazy Freddy's father. By his name, Christ Christ, may have converted to Judaism. Nevertheless, Donald's great-grandmother, Kathernia Kober, may have been Jewish.[17]

What we know is that the surname Kober is German and Jewish (Ashkenazic): from a derivative of the personal name Jakob or Yakov. German and Jewish (Ashkenazic): from German Kober "basket", Middle High German Kober, hence a metonymic occupational name for a basket maker or perhaps a nickname for someone who carried a basket on his back.[18] The Kallstadt, Pfalz - Rhineland-Palatinate area where they lived in Germany comprised the Jewish communities of Mainz, Speyer and Worms became the center of Jewish life during Medieval times.[19]

Trump's father, Fred

Paul S Writes:

The Trump family, like the Heinz family (also Jewish), is from Kallstadt Germany, which is a small village located within walking distance of the Speyer/Worms/Mainz Rhineland metroplex. This area of the Rhineland (i.e., Speyer/Worms/Mainz) has basically been the "homeland" of Ashkenazi Jews for more than 1,000+ years -- indeed, even Frankfurt and the Rothschild clan are likewise just up the river, again within walking distance of Mainz. If you're a billionaire and you're from the Rhineland, it stands to reason that you're probably a Jew. I suspect his first wife Ivana was also Jewish.

That said, for a country that was founded (literally) by Zionist Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock and constituted 150 years later by Zionist Freemasons in Philadelphia, what would you expect? Rather than complaining about "Zionist" America -- which is something that has been in America's DNA since Day One -- I've found it more constructive to focus on my own heritage and ancestors, and pay as little head to the Beast as possible. Wise as serpents, harmless as doves so to speak.

Glen- "Donald Trump is nothing less than a sideshow and a counterfeit medieval medicine man offering cheap miracle and ILLUSIONARY fixes for America's problems here and abroad."

I've been shouting this shite from the roof tops for months now. Anybody(and by God there are plenty)who cannot see through this "phony bologna, plastic banana good time rock and roller" is a sucker and a fool. Does anyone think this clown made his millions by being a square shooter and playing by the rules? Give me a freakin' break !

0 notes

Text

David Rockefeller, Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski and now Jimmy Carter are united in the grave of infamy for what they did to America in the 1970s. Carter, a peanut farmer from Georgia and former governor of that state, was hand picked, groomed and trained by Brzezinski to capture our nation for the Trilateral Commission, lock, stock and barrel. His vice-President, Walter Mondale, was also a member of the Trilateral Commission.

What was President-elect Trump thinking when he said,

“The challenges Jimmy faced as President came at a pivotal time for our country and he did everything in his power to improve the lives of all Americans. For that, we all owe him a debt of gratitude.”

Let’s examine the record

I remember Carter’s campaign slogan, oft repeated: “I will never lie to you.” Even Reuters dug this out for their obituary last week:

“I’m Jimmy Carter and I’m running for president. I will never lie to you,” Carter promised with an ear-to-ear smile.

In fact, it was all a lie. His image was a lie. Everything that came out of his mouth was a lie. He lied about the Trilateral Commission and its intention to take over the American government.

Trilateral Hedley Donovan was editor of Time Magazine who named Carter “Man of the Year” in 1977. Donovan lied when he wrote,

“As he searched for Cabinet appointees, Carter seemed at times hesitant and frustrated disconcertingly out of character. His lack of ties to Washington and the Party Establishment – qualities that helped raise him to the White House – carry potential dangers. He does not know the Federal Government or the pressures it creates. He does not really know the politicians whom he will need to help him run the country.”

Really? Read on…

He lied when he appointed almost 1/3 of the membership of the Trilateral Commission to top posts in his Administration including,

Zbigniew Brzezinski – National Security Director

Cyrus Vance – Secretary of State

Harold Brown – Secretary of Defense

Brock Adams – Secretary of Transportation

W. Michael Blumenthal – Secretary of the Treasury

Andrew Young – Ambassador to the United Nations

Warren Christopher – Deputy Secretary of State

Lucy Wilson Benson – Under Secretary of State for Security Affairs

Richard Cooper – Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs

Richard Holbrooke – Under Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs

W. Anthony Lake – Under Secretary of State for Policy Planning

Sol Linowitz – co-negotiator on the Panama Canal Treaty

Gerald Smith – Ambassador-at-large for Nuclear Power Negotiations

Elliot Richardson – Delegate to the Law of the Sea Conference

Richard Gardner – Ambassador to Italy

Anthony Solomon – Under Secretary of the Treasury for International Affairs

C. Fred Bergsten – Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for International Affairs

Paul Warnke – Director, Arms Control and Disarmament Agency

Robert R. Bowie – Deputy Direction of Intelligence for National Estimates

There were others.

He lied when he sent Trilateral Sol Linowitz to negotiate the giveaway of the Panama Canal — sovereign property of the United States of America. Linowitz served on the board of directors at Marine Midland Bank that was on the ropes because loans due from Panama were at risk of default.

Sutton and I examined this situation and found,

No fewer that thirty-two Trilaterals were on the boards the thirty-one banks participating in the Republic of Panama $155 million 10-year Eurodollar issued in 1972.

Fifteen Trilaterals were on the boards of fourteen banks participating in the Republic of Panama $20 million floatine rate promissory note issued in 1972.

Jimmy Carter was a sock puppet of the Trilateral Commission. An empty suit. A straw man set up to achieve Trilateral goals to create its New International Economic Order, aka Technocracy.

Indeed, America does not owe Jimmy Carter “a debt of gratitude.”

4 notes

·

View notes