#i like the more grounded/realistically depicted stuff within light's world more

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

can you please share your thoughts on watari as a character 😭🙏

I sure can!

I think he was introduced originally as a purely plot devicey sort of guy, without a lot of deep thought put into him... just this mysterious cloaked figure slinking around in the classic detective trenchcoat and fedora, bringing intriguing news from L on his laptop now and then. Then as the story progressed Ohba expanded his role into another plot devicey stoic background Alfred the Butler sort of guy. THEN once Ohba decided to go the direction he did with the story, he filled in L's backstory more (as he said he didn't have a fixed origin story in mind for L when he first created him) and came up with the idea that Watari had originally been a great inventor / the concept of Wammy's & L being something of a "invention" of Watari's - which definitely puts a potentially creepier/darker spin on him as a character and his relationship with L, and by extension L's successors. And other stuff like the one-shots showing how Watari first met L, and how darkly the Another Note novel depicts being one of Watari's experimental L runner-ups, further adds to this ominous vibe.

Thinking about Watari realistically and the implications of Wammy's, putting these orphans into competition with each other in ways that clearly messed many of them up, he seems like a bit of an evil bastard, and even Ohba said something along those lines about Watari/Wammy's in the behind the scenes book himself. but I don't think originally that had been the plan for him as a character. It just sort of developed that way as Ohba filled in the backstory of his characters and further extended the plot. I actually think it's a bit annoying sometimes, because I find him to be kind of a funny/inoffensive presence in the story otherwise, and at times I wish he could have remained just some guy that L hangs out with - I'm always caught a bit between going "haha look at the funny old guy scooping ice cream/scolding L for being rude/sniping people from helicopters" and thinking that it's not okay to appreciate him for that because Wammy's is kind of the worst/he is kind of the worst for founding it, maybe...

#in short: L's backstory is def a cartoonish aspect of the series and not my most fave part but#it definitely adds a lot to the series in its own way that the fandom loves too?#idk i go back and forth on how much fun i find it to think about and how much i like it as part of the lore#i dont think it's the strongest aspect of the series as a whole at any rate#i like the more grounded/realistically depicted stuff within light's world more#ask#anon#p#watari

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bear “Pasta” episode is about tainted/interrupted magic.

Walk with me.

In my previous meta I discussed how The Bear uses magical realism or marvelous realism in its story telling as evidenced in “Pop”. This is also very evident in the episode “Pasta”.

What Is Magical Realism?

Magical realism is a genre of literature that depicts the real world as having an undercurrent of magic or fantasy… Within a work of magical realism, the world is still grounded in the real world, but fantastical elements are considered normal in this world.

David Lodge defines magic realism: "when marvellous and impossible events occur in what otherwise purports to be a realistic narrative"

The genius of The Bear is that it’s so subtle in its use of marvelous realism that it is totally left to interpretation. The magical aspects of the stories are so blended in with the ordinary so much so that you might not notice at all. We can see The Bear employing aspects of folklore and the supernatural in the most subtle ways.

Violet.

Over the course of the season, we’d see the color and general ambience of the show shift a lot to emphasize the mood and the events. This episode focuses on Carmy and Syd bonding over the menu they’re trying to create and it feels (to the sydcarmys at least) like some type of love is in the air. This is the closest Sydney and Carmy had ever been in proximity and intimacy to that point. It is also the most progress they made on organizing the menu in the season. We even arguably see Carmy the most animated and relaxed for how neurotic he is known to be.

In this episode we see a lot of violet or purple, which is associated in magic with love potions. There’s a ray of violet light streaming through the restaurant and all through the episode we can that (especially) Carmy’s skin is ever so slightly tinged purple. There’s also a hint of purple in almost every scene either from the lighting to random purple objects in the background (remember season 1 with the tomato cans everywhere? They’re saying something).

This was a very deliberate choice and the biggest evidence is the Chicago flag shown at the start of the episode.

The Chicago flag in The Bear vs the real Chicago flag.

Wiz Richie

Richie assumes the role of the wizard-in-charge, dressed in the purplest purple and trying to assert himself all over the ongoing renovations at the restaurant. He calls himself the supervisor (supervisor of the spell?), accuses people (obviously the audience) of not knowing “how to watch stuff”, in other words we should be paying more attention. The movement or beat of the episode is also centered on him. Everything is going chaotically well as it does with the Berzatto clan both at the restaurant and away but then…

Richie finds an anomaly.

Mold is the death knell

Fak tells them mold is the death knell and it could "ruin everything". In other words, it could spoil the magic that's already happening, because it will.

Richie is in denial about the presence of the death knell and is trying to get everyone to ignore the problem instead of dealing with it the right way. But there really IS a problem and his efforts to prove there wasn’t results in a more catastrophic ruining of the magic.

This moment is where the whole trajectory changes. That’s the exact moment Carmy runs out of veal stock and has to go to the store. While Emmanuelle and Syd's dinner turn from sweet memories to an argument about whether Carmy is trustworthy, Carmy runs into Claire.

A breached portal

What I love about this scene is how once you see it you can’t unsee it.

The way Claire is introduced into the scene, it’s almost like in a marvel-esque fantasy film where a portal is opened do or create something good but some other force gains access to that portal and is introduced to their world. We also see the introduction of the cold blue that pervades the rest of the season.

We can sense Carmy's discomfort. He tries to gently evade what's to come.

But the mold has taken hold.

Sometimes the dark force is not a horned creature with a three pronged weapon. Sometimes the dark force is beautiful and smiling and “remembers you”.

Note: While I now and forever will be anti Claire bear and even though the format, through this marvelous realism lens, casts her as a malevolent force, in reality she probably isn't. Storer stays deceiving and léger de main, remember? Ultimately Carmy is the one "trapped in a prison of his own design".

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

that big “what the fuck is up with Matt Murdock’s senses” post I keep threatening to make

For context, my day job involves studying animal communication, where I am a PhD student in evolution/animal behavior. I don't work on organisms that use non-standard sensory modalities directly, but I'm very familiar with the adaptations that electroceptive and echolocatory systems (mostly in bats, that latter one) generally require.

I also spend an awful lot of time watching my cat Dent, who has been blind probably from birth and definitely since he was about ten weeks old. (We're not entirely sure whether he can see light or movement, and he definitely can't see anything else.) Dent therefore has access to certain sensory modalities that are more sensitive than vision (cats can hear much higher into the ultrasonic than humans and have a wider range of olfactory sensitivities) without actually having vision to rely on, and thinking about what it is that specific sensory modalities actually bring to the table in terms of function.

What I am not is a blind person, nor have I lived or worked closely with someone who is. This is therefore going to be a discussion that focuses pretty heavily on "okay, let's assume Matty really does have ears like a bat--how does that constrain what he can and cannot do?" and less on the actual functional issues for someone who is, you know, a blind human--although if folks have comments on that, I would absolutely fucking love to hear them.

TL, DR: radar isn't fucking magic, and neither is echolocation. And physics still matters when we get down into sensation, more than you might think.

One of the things you have to understand when you're trying to study sensation and perception is that different sensory modalities--sight, touch, hearing, proprioception/balance, echolocation, etc--are good for different things. We tend to intuitively understand this in humans, but when reading experiences of characters with very different sensory toolboxes I often find that people simply... assume that the "extra-sensitive" senses can more or less perfectly compensate for the loss of vision.

The thing is, different sensory modalities are good for different things. That's why different groups of animals develop specialties in different modalities in the way they do. Some of what evolution can do is constrained by phylogenetic history--mammals are always going to have a leg up on birds when it comes to hearing in high frequencies, for example, because of a quirk of the development of the mammalian jaw--but a lot comes down to the interaction between the world around a particular animal and the needs and ecological niche that the animal takes up. Species generally specialize and hone the sensory systems that they have available which are useful to the needs of the animal in question.

What I mean by this is that you have to understand that different sensory systems are really good at different things, and sometimes you need different levels of resolution for different tasks. You can think of sensory systems as having two kinds of resolution: temporal and spatial. Vision has, generally speaking, pretty fine temporal resolution--you get a continuous "picture" of things around you and where they are at any given time. Your spatial resolution, as anyone who wears glasses (me included!) can tell you, varies based on your individual eyes and level of focus.

There's one final distinction that is important to bring up with respect to choosing sensory modalities, and that is active versus passive sensation. You can define this by asking yourself: do you have to do anything to work this sense and pick up stimuli from the environment around you? If yes, we're active; if not, we're passive. Humans don't really have any equivalent active sensory modalities with the possible exception of touch, but because Matt is almost always depicted as having access to at least one (echolocation, "radar"), I'm going to talk a little bit about those here, too.

Why does resolution matter?

Well, when we talk about modalities compensating for each other as an individual navigates the world, resolution is what lets us adapt senses to do each other's jobs. Fine resolution isn't always the most useful range for a given sense, either: olfaction has very coarse temporal resolution and moderate spatial resolution in most species, and that means that you can use it to tell where things have been even if the thing creating the signal is no longer there. Echolocation has perhaps the finest possible temporal resolution in that it is not a continuous signal--more on that in a minute--and very, very fine spatial resolution, but only for the instant of a given vocalization. Vision has very tight temporal resolution and very tight spatial resolution, depending on the level of focus a given person has.

What's the deal with active versus passive sensation?

For one thing, that means that Matt should not be able to use either echolocation or "radar" unless he's actually producing some kind of signal. I keep putting "radar" in quotes because it's not used by any known biological system; the closest analogue is probably electroception, but electroception is prettyk much exclusively used and developed by aquatic or semi-aquatic animals and uses different ranges of electromagnetic waves to most human-built radar systems. That means that echolocation doesn't produce continuous information the same way that passive sensory systems (like vision!) do, which means that Matt has to string together a series of disconnected "impressions" of where things are in space and time to make a "picture" of the world around him, at least with respect to that sense.

Basically, the way these sensory systems work is that you produce a signal and you "listen" to the response patterns. This means that if you aren't producing that signal, you don't get anything. This is interesting and important in the context of Daredevil because Matt very specifically does not produce any vocalizations or noises that could be used for echolocation in the human range, and it's even less likely that he's continously emitting weak electric charges into his environment--the air just isn't a good enough conductor to give him any real distance.

So if he's doing this, he's doing it at either very high pitches, outside the usual human auditory range, or else at very low pitches--and high is much more likely. High-frequency vocalizations decay faster over space, which is why they don't carry well. Because of this, and because the pattern of reverberation and decay of the sound is what you're using to construct the idea of shape with echolocation, all known echolocating species use very high-frequency, very loud vocalizations to create pulses of sound that will decay in ways that are sensitive to the shape of whatever they're bouncing off of.

Personally, I like to imagine Matt squeaking at very high pitches like a real bat might, mostly because I think it's funny. This is particularly amusing because in many social species that rely very heavily on echolocation or electroception, individuals produce a signal that is unique to them within the local group--so it's the equivalent of Matt wandering around yelling MATT MATT MATT MATT whenever he wants to get a good sense of its position and shape without having to actually, you know, touch it. (This may or may not be a good way for Stick and Matt to get a sense for where each other are at a distance--if they're managing to make a super high-pitched vocalization, it probably doesn't carry too well. On the other hand, if they're fighting something as a team, as we see both of them doing, the odds are good that each is listening to the information that the other is getting if one or both is using whatever this sensory system is. )

If I'm going to take a more realistic tack on the whole thing, I'd guess he's probably vocalizing through his nose, which is pretty common in both human vocalizations (you don't need your mouth to be open to say nnnnn or mmmm, because those sounds are produced via reverberations through the nasal cavity) and also in many ultrasonic vocalizations specifically (for example, the ultrasonic communication that rodents often engage in).

(Humans who say they can use echolocation in real life rely on clicks and taps, which is why I think it's particularly interesting that Matt is consistently shown using his long cane a few inches above the ground. I don't think he ever uses it to tap the ground in the show, and he certainly isn't making a loud click noise with it. Both clicks and taps can work for echolocation because these are wide-frequency noises, so you still have the decay patterns of the higher frequencies to work off of if you can filter through the lower-frequency stuff muddying the waters. It's not very sophisticated and will only give you a comparatively broad sense of where things are, but it's certainly better than nothing. But whatever Matt is using, he's specifically not using that to navigate his world.

A friend who uses a long cane suggested dryly that this might be an attempt to avoid the common peril of getting one's cane stuck in a pothole and winding up taking your cane to the balls or the kidneys, which... given the general lack of maintenance of Hell's Kitchen in other venues of the show, I suspect this is a peril Matt has been negotiating for some time.)

So what is Matt likely to use?

Honestly, I'm pretty sure that Matt's most important sense day-to-day isn't echolocation. It's his proprioception--his sense of where he is in the world, his spatial memory and his sense of balance. I heavily suspect that he has an incredibly good spatial sense and ability to process spatial information, and I notice that his combat style is heavily geared towards blocking his opponents into a space and hitting them until they go down. (Matt spends a lot of time using space to his advantage in combat--when he's not stalking an opponent and bringing them down by surprise, he's either constantly blocking them in and grappling close in or he's using a narrow confine like a hallway or an alley to constrain his opponent's ability to move quickly. Because the ability to echolocate does require him to produce a sound and because I'm not aware of any way to produce sufficiently high-pitched sounds that doesn't involve forcing air through the larynx at some level, I would guess that he's actually primarily relying on passive listening to pick up cues about what is going on in his environment in the middle of combat. I'd gamble he's most likely to quickly use his active sense (whatever it is) to make a rough "sketch" of what's going on around him in moments of relative quiet, when he's not moving too quickly to control his breathing.

I like constraint in my headcanons, because it lets me plumb the unexpected boundaries of abilities, perceptions, and creates avenues for conflict and unexpected humor; if you don't--and the writers of Daredevil in all forms certainly don't seem to be particularly careful about this--seriously, by all means ignore me or pick out whatever you like and leave the rest. But hey, I had fun putting this fucker together.

This post is crossposted at pillowfort and dreamwidth.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Through 2019 (Part 1)

As always, I had a lot of fun with reading this year. I found a couple of new used bookstores that I love, I made good use of libraries, I discovered new authors and doubled down on some favorites, I created a #Bookstagram account, and maybe most importantly...I got really good at reading on airplanes!

Heading into 2019 I knew that with a new work commitment (I took a job that had me travelling about 75% of each month) I had to be realistic with my reading goals. I cut my goal down to 25 after reading 40 books last year. This turned out to be a wise move and I comfortably hit my mark. I got in a good mix of Fiction, History, Biography, and Memoir.

Here’s what I read this year (in chronological order):

The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama, by David Remnick (2011, 704 pages) This is the best book on Barack Obama (not including his memoir, Dreams from My Father) that I’ve come across. Remnick is a talented writer and successfully combines compelling prose and detailed research with a tremendous number of interviews of folks close to the 44th president from the different parts of his life. I took my time reading this one, usually in 20-30 page chunks in bed before sleeping.

Leadership: In Turbulent Times, by Doris Kearns Goodwin (2018, 473 pages) I read this entire book on a long day of travel between Des Moines, Iowa and Newark, New Jersey. An important endorser gave this book to my boss and I got to read it. I saw DKG speak about Leadership at the 2018 National Book Festival and was completely taken by her. This is a good book with a relatively unique format, to be coming from a historian, that works well to instill some solid lessons from the individuals profiled in the book: Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, FDR, and LBJ.

One L: The Turbulent True Story of a First Year at Harvard Law School, by Scott Turow (1977, 288 pages) A fun book to read, though maybe not the most original. I don’t think I got much substance from this that I didn’t get from the book The Paper Chase, which was published six years earlier.

Liar’s Poker, by Michael Lewis (1989, 310 pages) I’m a big Michael Lewis fan so I was excited to tear into his first book about his time at the legendary investment bank, Solomon Brothers. Lewis’ characteristic mixture of accurate, educational factoids and history, hilarius details, and masterful storytelling were all mostly in place in this book. This is a great book for anyone interested in finance, but will definitely keep you entertained even if that’s not exactly your forte.

The House of God, by Samuel Shem (1978, 416 pages) Hilarious. Disgusting. True. These are the overwhelming reactions I got from this book. Shem (real name, Dr. Joseph Bergman) got a lot of flack from the professional medical community when he released this satire depicting the hell that is the intern year at a top hospital just after graduating from a top medical school. This book is not for the faint of heart, but seems to give some genuine insight into the old, elite, and maybe a bit self-important profession of medicine.

“LAWS OF THE HOUSE OF GOD I Gomers don’t die. II Gomers go to ground. III At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse. IV The patient is the one with the disease. V Placement comes first. VI There is no body cavity that cannot be reached with a #14 needle and a good strong arm. VII Age + BUN = Lasix dose. VIII They can always hurt you more. IX The only good admission is a dead admission. X If you don’t take a temperature, you can’t find a fever. XI Show me a BMS who only triples my work and I will kiss his feet. XII If the radiology resident and the BMS both see a lesion on the chest X ray, there can be no lesion there. XIII The delivery of medical care is to do as much nothing as possible.”

Beneath a Scarlet Sky, by Mark T. Sullivan (2017, 513 pages) Another book that I read entirely on a series of airplanes. This time I was travelling between DC, Indianapolis, El Paso, and Las Vegas, before heading to Wisconsin to return it to my girlfriend’s mother who lent it to me. We both agreed that this historical fiction piece was a little light on beautiful writing, but more than made up for it with compelling prose and historical detail. Recommended for history buffs who might want a unique look at a subject (the Italian experience in WWII) that doesn’t get as much artistic coverage as some others.

Spy Master, by Brad Thor (2019, 402 pages) I picked this one up to pass the time in a Wisconsin airport during a long weather delay back to DC. I’m a casual fan of paperback espionage/military/government thrillers and hadn’t read a Thor book before. Not my favorite practitioner of the genre, but I wasn’t disappointed.

When Life Gives You Lululemons, by Lauren Weisberger (2019, 352 pages) Another airport bookstore special - I loved reading this book. I had a short break from work when I got this and was looking for something to totally get me out of my headspace. Emily Charlton (the protagonist from Devil Wears Prada), and her world of celebrity sex scandals, coverups, and adult irresponsibility did the trick.

Losing Earth: A Recent History, by Nathaniel Rich (2018, 224 pages) A compelling and heartbreaking quick read history of when the US government almost preemptively tackled climate change. Picked this one up from the new releases section of my local library.

Sag Harbor, by Colson Whitehead (2009, 273 pages) An interestingly constructed recounting of childhood from a super talented writer. Recommended for Black people, for a summer read, or for those looking to escape to the summer in their mind in the middle of an urban winter.

The Fifth Risk, by Michael Lewis (2018, 219 pages) The second of three Michael Lewis books for me this year. Fascinating dive into parts of the federal government that most people don’t understand at all. I saw Lewis speak about this one at the 2017 National Book Festival when he was still in the writing process.

On the Brink: Inside the Race to Stop the Collapse of the Global Financial System, by Henry M. Paulson, Jr. (2010, 528 pages) The 2008 financial crisis is one of my very favorite historical (weird to say as we all lived through it) events to read and study about, and Hank Paulson, then the Secretary of the Treasury is my favorite character within the all encompassing drama. This book is FULL of technical details that you’ll savor if you love federal government of finance. The lack of personal anecdotes was a bit disappointing (though totally in character for Paulson) and might make this a tough read for those who aren’t active nerds for the topic.

The Right Stuff, by Tom Wolfe (1983, 369 pages) A candidate for favorite book of the year. I’ve read other Tom Wolfe material before and loved it, and this one did not disappoint. Wolfe was a standard bearer for a style of writing called “New Journalism” that aimed to communicate real stories that read like a novel. He nailed it with this book detailing the creation of NASA’s successful Mercury effort to reach the moon ahead of the Sovient Union. High octane and drama, comedy, historical accuracy - this book’s got it all.

“After all, the right stuff was not bravery in the simple sense of being willing to risk your life (by riding on top of a Redstone or Atlas rocket). Any fool could do that (and many fools would no doubt volunteer, given the opportunity), just as any fool could throw his life away in the process. No, the idea (as all pilots understood) was that a man should have the ability to go up in a hurtling piece of machinery and put his hide on the line and have the moxie, the reflexes, the experience, the coolness, to pull it back at the last yawning moment—but how in the name of God could you either hang it out or haul it back if you were a lab animal sealed in a pod?”

0 notes

Text

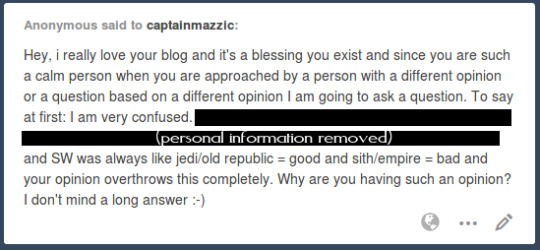

Well hi there, and thank you for the compliment. I’m a little less calm than I look, honestly, but at least with questions on tumblr I can take my time to answer them. It definitely helps me get my thoughts together.

And I do have a very long answer for you, and it comes in several parts. Bear with me.

Answer part one:

The basic idea of Jedi/Old Republic = good and Sith/Empire = bad is a very, very simplistic premise, and significantly unreflective of anything remotely realistic. I like highlighting the grey areas, the areas where the Jedi and Old Republic were NOT good, and the areas where the Sith and Empire were NOT bad. And mostly it’s a heavy emphasis on the former.

Many times I do this because it’s something that not a lot of people are doing, and I feel it’s something that should be taken notice of more often. While we might be told we’re supposed to see the Jedi and Republic as pure innocents, as saints, as the heroes and the ones who are purely Good, and at worst maybe a little misguided sometimes, that is not what is depicted. I take issue with people showing me a picture of a grassy field under a blue sky and telling me that even though that’s what’s depicted, I’m actually seeing a cityscape. And that’s kind of the impression I have of how Star Wars is presented to its audience right now.

What is depicted is the Republic/Jedi/Alliance performing questionable and sometimes downright atrocious acts of religious persecution, murder, slavery, brainwashing, terrorism, and unethical warfare.

And here’s the kicker – obviously, the Empire and the Sith are/were doing these things too. Every faction on this playing field is utilizing the same horrible set of skills and tactics and behaviors, but only one side of the conflict is being vilified and blamed for performing them, via the narrative. The narrative is quick to highlight, in high relief, all of the atrocities that the Sith and the Empire perform, yet doesn’t even acknowledge that the Republic/Jedi/Alliance are prone to doing these same things. At least, not openly. But the overwhelming evidence that they DO perform them is all over the place. I have cited many common examples before, but I’ll run the risk of repeating myself here:

the Jedi kidnapping children from their parents because they feel they have a religious right to these childrens’ bodies and minds before they even have the capability of making the choice themselves;

the Jedi readily going along with utilizing a slave army born and bred solely for the purpose of dying in a war;

the Republic utilizing orbital bombardment of Mandalore to the point where the planet’s entire surface was rendered unlivable for over 300 years, even though Mandalore was not currently at war with the Republic, and had made no move to declare such a war;

the systematic genocide of a wide variety of non-human species that the Republic performed for over eight hundred years that resulted in humans taking up the huge percentage of the population of sentient beings in the galaxy that they do today;

the Republic designing and utilizing a staggering variety of weapons of mass destruction capable of inducing planet-scale catastrophes (Hammer Station, Shadow Arsenal, Baradium Bombs, the Death Mark, the Shock Drum, etc. etc.);

the Alliance to Restore the Republic performing actions and displaying behaviors identical to modern-day terrorists (sabotage, espionage, theft, kidnapping, assassination, bribery, violence, and widespread destruction of government and public property in order to instigate political and ideological change);

the Republic actively endorsing and allowing an extremist religious sect to take a heavy-handed lead in, and sometimes even take entire control of, almost every aspect of the government and social lives of its people, including but not limited to politics, law enforcement, law making, judicial affairs, the military, religious freedoms, family planning, and forcibly implementing their own insular religious culture’s needs and desires upon non-member’s cultures;

The Republic claiming to be a “democracy” being run by “senators” and representatives where an alarming number of worlds have representatives which were not elected by their people and had no standard bar of leadership to pass to be included in the Republic’s proceedings (Republic worlds’ leaders range from actual senators, governors, and presidents to kings and queens, emperors, nobility, influential clans and families, military warlords, despots, dictators, heads of corporations and other business leaders, religious leaders, and criminal kingpins, not to mention the dozens of puppet governments that the Republic itself set up after it invaded and subjugated “problematic” planets).

This is a very brief and partial list, by no means exhaustive. And very few people talk about this stuff. Much of what I write is because I feel that this is a dialogue that can only benefit from being put out in the open, because there’s never just one side to a story. People are not arithmetic - there’s never just one right answer and all the rest are wrong. Things are complicated. People are not Good or Evil, they’re just people. And I think that’s very important to highlight, particularly here on tumblr, because it’s something that often gets lost in the highly charged and highly polarizing world of tumblr discussion and politics.

Answer part two:

One of the problems that I tackle frequently is people assuming that since I like the Sith and the Empire, that means that I must approve of everything that they do, and assume that I view them as the “good guys”. I don’t. Overall they’re just as terrible as the Republic and the Jedi and the Alliance, I just like the Sith and Imperials better than my other options. I like them for many reasons, and none of them have to do with me assuming that they would hold the real-world moral high ground. A few examples:

Aesthetics. I like the way they look, I like the way they feel, I like the atmosphere and mood that they set.

Childhood bias. I grew up thinking Darth Vader was The Coolest™, and the Star Destroyers were so awesome, and I got really excited hearing the shriek-roar of the TIE fighter engines, and red was my favourite colour and all the Sith had red lightsabers.

Individual characters being favourites within each group. Almost all of my favourite characters in Star Wars happen to be Imperials, Sith, or other disapproved-of fringe groups like bounty hunters, mercenaries, pirates, crime lords, etc. This tends to put me in the position of looking more favourably towards their faction or allegiance of choice, however slight.

None of this has anything remotely at all to do with whether or not I think the Sith and the Empire have the moral high ground. As far as I’m concerned, nobody has the moral high ground in Star Wars. I just don’t feel the need to echo and parrot the sentiment that everyone already knows, that the Sith and the Empire do bad things. Of course they do. They’re made of people. People do bad things. It doesn’t matter what sect or organization or government they belong to. And the same can be the reverse, as well. People do good things, regardless of what sect or organization or government they belong to. The Sith and the Empire are no exception, but we rarely get to peek into their side of things because that’s not the direction the dominant narrative prefers to go.

Everybody knows that the Republic and the Alliance and the Jedi are capable of doing good things. Everybody acknowledges those things already. The same with the fact that the Empire and the Sith do bad things. Everybody acknowledges that already.

But it’s the things that nobody likes to mention, the bringing out in the open of the fact that not everything the Republic and Jedi do is good, that not everything that makes them what they are is right; that is something that I feel is important to discuss. So that’s what I focus on. I feel like I’ve said the same thing in five different ways, but it’s something I want to be certain I’ve been clear on.

Nowhere, ever, have I said that the Sith and the Empire are the Actual Good Guys. I may like them more, but likability and intrinsic goodness are not the same thing, and have zero correlation. Personally, I don’t believe intrinsic goodness or badness even exist, but that is for a talk on relativism in general, and we’re here to talk about Star Wars.

Answer part three:

Another thing that I’d like to touch on, at least in regards to the Sith, is a partial religious identification with what the Sith are subtly engineered to represent. This one takes a little bit to explain, bear with me.

I adhere to an animistic, polytheist Pagan religion that I will refrain from naming. It maintains that there is a lot of power in the earth and the elements and our ancestors. The dualistic belief in a war between good and evil like the type so characteristic of monotheistic religions has never entered into my religion, so I fail to understand the appeal of something like, say, Light Side vs. Dark Side. Instead, I am much more comfortable with a worldview and belief system that sees the world in much more relative terms.

Circling back to how this relates to Star Wars, the Sith (and many non-Jedi Force-using sects, most of which turn out to be Dark Siders) as depicted in the many movies, books, comics, and animations are painted in unquestionably polytheistic Pagan colours. They are coded to look like Pagans, they have been designed to have rites and rituals geared to bring images of Pagans to mind, and underneath the Saturday-morning-cartoon “violence and blood and death and destruction! Yay!” veneer, many of them hold relative values and worldviews like Pagans. And to top it all off they are caricatured, vilified and reviled like Pagans so often are by many proponents of monotheistic religions in the world today. I am not impressed nor am I pleased.

From what I can see and the supplemental material I’ve read, the Jedi are modeled after well-established monotheistic religion, with bit of Buddhist and Taoist proverb taken out of contest and sprinkled on top to spice it up. And they play their part very well. Again, I am not impressed nor am I pleased, seeing the Sith – the biggest representative entity in Star Wars that’s painted in my colours, that reflects parts of my own worldview, however poorly – consistently depicted as the horrible evil Bad Guys that need to all be killed, for the good of the galaxy, and by the hand of the dominant monotheistic religion. That hits a little too close to home for me to be comfortable with it, particularly for the message it, intentionally or unintentionally, is communicating about how people should view or treat adherents of Pagan religions. My kneejerk reaction to that is to quietly say “no” and subversively adopt the Sith, and claim them as my own.

Answer part four:

This one is very related to that last sentence up there. My intrinsic nature is to find the people that nobody cheers for, to find the villains and the antagonists and the questionable side-characters and the morally ambiguous tricksters, and adopt them. I identify very closely with people like that. In life outside of tumblr, I fit into quite a few minority groups and often find myself on the outside looking in, when it comes to society and privilege and being deemed worthy or qualified to have good things in life. So I find that when it comes to fictional worlds and fictional characters in the stories and universes that I have grown to love, my heart goes out to the characters that nobody likes, or characters that everyone seems to think deserve to die, or just characters that get sidelined or ignored or left out in the cold. I take it upon myself to love them, and when many of them come from a group that is also deemed just as unworthy and unlovable as the characters themselves are, I tend to reach out to those groups as well. Honestly, this is the crux of the matter. I love Star Wars, I love the planets and the plotlines and the species and the technology and the starships and the magic of the Force, but I love it most for the individual characters.

So that’s pretty much it, I guess. This is all just my own personal reasoning for why I like the things I like and write the things I write, and I don’t claim to have all the answers or believe my word is some sort of sci-fi gospel or anything. There are lots of people out there who are perfectly happy with interpreting Star Wars in a dualistic light, and deeming that the Jedi/Republic have done nothing wrong, and that the Light Side truly does reflect Good and the Dark Side Evil. And you know what? That’s how they enjoy Star Wars and they are very welcome to a differing opinion. We tend to play in very different sandboxes, and none of us have any right to come stomping into the others’ sandbox and knock over their sandcastle. Dialogue and debate between us can be wonderful tools to help one another understand each other and enrich the fandom environment, as long as everyone involved is doing so willingly, and as long as those tools are not abused by using them to attack or demean others in a personal way.

When I make a post like this stating strong opinions I tend to get a bunch of angry anonymous messages bordering on hate mail, so I’m going to temporarily turn off anonymous messaging for a while. But I do appreciate the question, and I hope my answer was sufficient. :)

#star wars meta#sarc has opinions#replies#jedi critical#old republic critical#rebel alliance critical#dark side positive#imperial positive#sith positive#republic critical#anonymous#sarc talks to strangers#sarc speaks#long post

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Collector

The story told most often is that Greg Wilson was a child rapist, a murderer, and a monster, feeding off the trusting nature of young boys. But Greg had been my friend, and I know he didn’t do those things. I've tried to tell people the truth, but no one will listen. Maybe one of you will believe me.

The southwestern town I grew up in was small and isolated, surrounded by tall mountains, and resting near a deep canyon. There was one two-lane highway that stretched through the mountains and ran lazily across the town from one end to the other. Buying comic books there was impossible before the internet, so for me and the few other nerds and geeks in my town, Greg was the hero we thought we deserved, but, as we learned later, not the one we needed.

Greg owned the only comic book store in my town: The Rusty Robot. It was my favorite place in the world when I was a preteen. My friends and I worshipped Greg, whose inventory, as well as his personal collection, was the envy of everyone from small kids to some of my friend’s dads.

Greg had inherited a building when his father passed away, a two story space with a store on the ground level, and an apartment on the upper floor. After he inherited the place, Greg changed it from a hardware store into a geek’s paradise, filled ceiling to floor with stacked boxes of backlogged comic books. Figurines and collector’s items lined the tops of shelves, while valuable items were carefully positioned in shadow boxes behind the large glass counter, which held first editions of classic books.

One night, when the store was empty except for me and Greg, he swore me to secrecy as he donned white cotton gloves and delicately brought out a rare edition of the first book in the original Amazing Spider-Man series, placing it on the counter with a reverence reserved usually for holy objects. It was the most beautiful thing my young self had ever witnessed.

I loved comic books, but my real passion was collecting figurines from Fireball XL5, a sci-fi show popular in the sixties. My father had watched the show when he was young, and we used to watch it together when I was really little. My attachment to the show was solidified when my father passed away a week before my sixth birthday. I became a bit obsessed.

Greg knew of my collection, and would let me know if he found anything on the road at a convention or another store. Once, he purchased a pristine figure of Colonel Steve Zodiac from a Japanese collector he ran into in Indiana. He knew I was low on funds at the time, so he gave it to me as a birthday gift. Birthdays were hard for me, and he wanted to give me something that’d remind me of the happy memories with my dad. His mother had died when he was little, and I think he felt especially attached to me since we both knew what it was like to lose a parent as a kid. He really was a great friend.

Our town had a history of children disappearing: usually one a year. Each loss was devastating to the town, but between the mountains, the cliffs of the canyon, and the wild animals that occupied both, these disappearances were nothing anyone thought of as intentional malice.

The year I turned thirteen, that changed. Four boys went missing within nine months. The first one, Brandon, nine years old, went missing that January. The entire town got together and searched for him in the mountains and along the closest wall of the canyon. Then Jack, eight, went missing in February and the town doubled their efforts. Kyle, nine, disappeared one evening in early June, and Zack, seven, in September.

The kidnappings didn’t affect me much, beyond my parents spending a few nights assisting the searches. I hate to admit it but, as a new teenager, dealing with puberty and the selfishness found in most teens, I didn’t pay much attention to the missing flyers that began appearing in great numbers all over town. That is, until Zack was taken.

The town’s Middle School had a program called Kids Assisting Kids. Older students would sign up to tutor struggling Elementary School students. I had been tutoring Zack in math, and we had grown close over the year. As an only child, I found it nice to have a younger boy look up to me. I had gotten him into comic books, and he’d accompanied me often to The Rusty Robot. We were as close as an eight year old and a thirteen year old could be. When his mother called me, I was horrified. I remember feeling scared for what my friend might be going through, as well as anger at whoever could have taken such a sweet boy.

People noticed the trend of disappearing children instantly, and suspicion and accusations started spreading like wildfire. By the time Zack went missing, everyone in the town was in full panic mode. It was a small town and so everyone knew that all four of the boys had only two things in common: they went to the same school, and they all frequented The Rusty Robot. Greg became the town’s main suspect.

My mom, like most people’s mothers at that point, banned me from going to the store, so I didn’t see Greg for almost a month. From the news reports, I knew that they had found no evidence to support that Greg was the one behind the boys’ disappearances.

One weekend in late October, my mom went out of town on business. I woke up that Saturday a free man. I used a mixing bowl instead of a regular bowl to eat my Lucky Charm’s, and filled the late snowy morning with cartoons. A little after lunch, I decided to check in on Greg. I bundled myself in my thick winter jacket and boots, and hopped on my red Mongoose mountain bike. I rode down to the small central street in our town, lined with mom and pop shops.

Stopping in front of the door of The Rusty Robot, I noticed the “closed” sign hanging in the dirty glass. My stomach dropped. Greg never closed the shop during the day, especially not on a weekend. The media must have been doing more damage to the business than I had realized.

I pounded on the glass door, but heard nothing from inside. I pressed my face to the door, blocking the sun from my vision with my hands, and peered inside. The place was dark and empty.

Turning to the buzzer at the door, I rung the apartment bell. A window opened above me, so I stepped back to see Greg’s face hanging out.

I waved up at him.

“Oh, heyya Nate.” Greg said, without his usual enthusiasm. “I’ll let you in, one sec.” With that, Greg’s face vanished back into the apartment, and I heard the window close.

Moments later, I could see Greg approach the door from inside the shop. He waved as he saw me, and unlocked the door, stepping aside as he opened it to allow me past his large frame.

“Hey Greg!” I said, as cheerily as I could, and stepped inside. He closed the door behind me and gestured for me to follow. We walked to the back of the store, past rows of comics and graphic novels. The sun feebly stretched from the glass door towards us, but without much success. The posters of poised superheroes and cut outs of famous sci-fi characters looked menacingly down at me in the dim light as we passed. I stopped in front of Farscape’s villain, Scorpius, who loomed above me. His leather mask revealed taught grey skin. Deep red lines that looked like a blend of wrinkles and scratches, stemmed from beneath his eyes and mouth. His black lips were pulled back into a nasty smile, revealing yellow pointed teeth.

I shuddered. The show was silly, and I had never been shaken by the character’s appearance before, but his face morphed into a nightmare in the dark stale air.

I jogged to the stairway at the back of the room, which Greg had vanished into. That had been the first time I ever saw the door to his apartment opened. I followed him up into the dark unknown.

Entering the kitchen, I squinted at the sudden light. A bare bulb above me illuminated the entirety of the main room, which consisted of both the kitchen and a small living room. Greg’s apartment was pretty much what I was expecting. The first thing I noticed was that, like the store, the walls were lined with boxes from floor to ceiling. The contents of his collection. The kitchen’s once white linoleum floor was curling with aged and yellowing from a lack of mopping. The wooden cabinets looked warped, one door hanging loosely from its top hinge. Outdated wainscoting ran along the perimeter of the entire room, cut off halfway up by an over the top but faded floral pattern.

The kitchen had an old rectangular table in the middle, with two chairs on either side. There was a worn beige armchair with a matching footrest in the living room, placed strategically in front of a small television I recognized from shows that played after cartoons stopped during weekday afternoons, like I Love Lucy and The Happy Days. I’d watch them sometimes when I was home from school, sick.

The room smelt bodily, like a mix of sweat, old food, and fear. I mindlessly picked up a figurine I didn’t recognize, and examined it. It was an amazingly realistic depiction of an older man. He was tall and thin, his mouth set in a tight scowl. He felt like he might have been made of leather, the texture of his skin more forgiving than the hard plastic I was used to, and his fine white hair rested in a comb-over above splotched wrinkled skin.

I felt the heaviness of the silent room around me, and looked up at Greg, who stood before me, staring at the floor. His face was oddly unshaven, and his hair was even frizzier than normal. He looked like he had lost weight, his skin waxy and loose.

Uncomfortable in the silence, I finally spoke. “How is it going?” I asked, realizing how stupid that question was in the moment, but unable to think of a better conversation starter.

He looked up at me with eyes outlined in red, and stared for a moment. I swallowed, shifting my feet beneath me in discomfort.

“I’ve been collecting.” He responded.

I looked around, nodding encouragingly, “yeah, this place is full of stuff!” I smiled at him, hoping the conversation would become less awkward.

“No, not this stuff.” He said, gesturing towards the boxes. “I’ve been collecting something better.” He emphasized the last word, his eyes growing wide. “A man from Russia came into my store six years ago and sold me something. Something… special.” His face gleamed with a manic thrill.

I nodded slowly, trying to figure out what he was trying to tell me.

He continued, “at first, I just used it to get this place started. But then, over the years, I’ve grown to love it.” He leaned closer towards me, and I took a step backwards, uncomfortable with his tone. “I’ll admit, it’s turned into a bit of an obsession.” He paused, his eyes never leaving mine. “You’re a collector.” He said in a low tone. “You understand how addicting it can become.”

My heart was racing. This was not the Greg I knew. This was a Greg, who for the first time, I realized might be as bad as the press claimed he was. But I had never even heard Greg swear, let alone express any interest in violence against someone else. He even refused to carry some of the more mature comics for that very reason.

“I’ll show you.” He turned, and shuffled to a door in the back. He opened it, and I reluctantly followed, lead by a loyalty to my friend, even though my heart pounded with fear. The door revealed a much cleaner and neater room then the rest. White bookcases lined the walls, filled with what I recognized as the more valuable part of Greg’s collection. The items were illuminated by small lights set into the top of each shelf.

He gestured to a thin glass cabinet in the corner, set apart, and stopped. I walked up to it and looked inside. It displayed nine small figures of children. They were each about six inches tall, and were the most lifelike figures I had ever seen. The features of their faces were incredibly realistic. I examined each one individually, in complete awe of the detail.

I stopped at the last figure, my blood turning cold. I recognized that face. It was Zack’s.

I turned slowly towards Greg, who was behind me holding a small futuristic toy gun. It looked sort of like one of the Phasers from Star Trek, but it was different somehow. The more I looked at it, the more real the collectible seemed. It wasn’t one of those cheap plastic things you usually see, but actually made of metal and glass.

“What’s going on, Greg?”

“I got this from the Russian. He had called it a Ctatyetka Gun. It sounded impossible, but the price was cheap enough, so I bought it on the spot.” He rubbed the toy affectionately, then turned his attention back to me, “I’m so happy you came. I’ve been waiting for you.”

“What do you mean, Greg? What does that gun do?” I said, my throat tightening with fear.

Greg nodded to the glass case, to the figurines, to the young boys shrunken and frozen in time. I knew that even the ones who had disappeared years ago still had family searching for them, hoping with the last of their strength that they were okay. Despite all logic and reason, these boys were standing in a display case in Greg’s apartment.

My eyes grew with realization and horror as Greg held up the gun, aiming it directly at my chest. “I have to leave here soon, Nate. I have to get out of this town.” Greg said, stepping towards me, “You’re a little old for the collection, but I love you so much, I can’t bear to leave without you. I want you to be apart of it.”

I stepped back, trying to make my way towards the door.

I watched Greg’s finger tighten over the trigger. He shook his head, “now we can be together forever, Nate. I can be the father you deserve.”

Instinctively, I dropped to the floor. A high pitched buzz vibrated over my head, and an unnatural green light illuminated the walls. Greg’s face was bathed with the eerie light. He looked like he was radioactive, his facial features tight with determination, his thin lips twisted into a sneer.

I remembered the old man figurine I was still holding. I reached up and smacked Greg’s hand as hard as I could. He yelped, and the gun flew out of his grasp, landing by my leg.

I grabbed it and jumped up, aiming the weapon at his chest. Terror washed across Greg’s face.

“Guess I’m not as slow as a nine year old.” I growled. I felt my outstretched arms shake with anger as I thought of the missing posters all over town. Zack wearing a bright yellow jersey, on one knee in a grassy field, a soccer ball resting on his thigh. I could see the wide warm smile that followed me as I biked through the familiar town streets, the right front tooth missing.

I tightened my finger over the trigger, and shot him. Green light spilled from the narrow muzzle, encapsulating his large body in a sickly aura. I watched with fascination as Greg shrunk in front of me. The green light grew brighter with every second, and I eventually had to turn away from the sight. My eyes burned, so I shut them tight, small tears of pain and loss escaping my eyelids. I let go of the trigger, and looked up.

An eight inch figure of a man stood in front of me, the statue of the older man lying on the floor next to him. I put the gun down on the table beside me, and picked both figurines up. The new one was a man in his late thirties, the red shirt and grey pants he wore were stained and worn. I looked at Greg’s tiny face. His expression was one of betrayal and hurt. My eyes darted to the older man’s and I screamed. I dropped both dolls and ran outside, jumping on my bike and pedaling as fast as I could away from there.

The old man’s scowl had transformed into a satisfied smile.

I called my mom the second I got home and told her what happened. She immediately canceled the rest of her trip and came back. The next week was full of police questioning. I repeated my story over and over again, but no one believed me.

The official story is that Greg Wilson tried to kidnap me, as he did the others, but I had escaped. Greg had left town when his attempt was foiled, but neither him nor any of his victims were ever found. During the next ten years, the disappearance rate of boys under ten in my childhood town diminished back to what it had been before Greg’s father passed away six years ago.

The part of the story I had never told anyone before now is that I went back to Greg’s apartment later that week. The figurines weren’t taken as evidence, and I found the gun on the table where I left it, surrounded by what a naive cop considered collectibles of the same value and nature.

As an adult, I’ve continued growing Greg’s collection. But not with little boys. I prefer older men. Despite the trauma of that day, I still think fondly of my other memories with Greg. And besides, Greg wasn’t a child rapist, nor was he a murderer, or even a monster, really. He was a collector.

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is your brain on art: A scientist’s lessons on why abstract art makes our brains hurt so good

Kandel’s took a Nobel-winning scientist who specializes in human memory to break new ground in art history

The greatest discoveries in art history, as in so many fields, tend to come from those working outside the box. Interdisciplinary studies break new ground because those steadfastly lashed to a specific field or way of thinking tend to dig deeper into well-trodden earth, whereas a fresh set of eyes, coming from a different school of thought, can look at old problems in new ways. Interviewing Eric Kandel, winner of the 2000 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, and reading his latest book, "Reductionism in Art and Brain Science," underscored this point. His new book offers one of the freshest insights into art history in many years. Ironic that it should come not from an art historian, but a neuroscientist specializing in human memory, most famous for his experiments involving giant sea snails. You can’t make this stuff up.

I’ve spent my life looking at art and analyzing it, and I’ve even brought a new discipline’s approach to art history. Because my academic work bridges art history and criminology (being a specialist in art crime), my own out-of-the-box contribution is treating artworks like crime scenes, whodunnits, and police procedurals. I examine Caravaggio’s "Saint Matthew Cycle" as if the three paintings in it are photographs of a crime scene, which we must analyze with as little a priori prejudice, and as much clean logic, as possible. Likewise, in my work deciphering one of most famous puzzle paintings, Bronzino’s "Allegory of Love and Lust," a red herring (Vasari’s description of what centuries of scholars have assumed was this painting, but which Robert Gaston finally recognized was not at all, and had been an impossible handicap in trying to match the painting with Vasari’s clues about another work entirely) had to be cast aside in order for progress to be made.

Ernst Gombrich made waves when he dipped into optics in his book, "Art and Illusion." Freud offered a new analysis of Leonardo. The Copiale cipher, an encoded, illuminated manuscript, was solved by Kevin Knight, a computer scientist and linguist. It takes an outsider to start a revolution. So it is not entirely surprising that a neuroscientist would open this art historian’s eyes, but my mind is officially blown. I feel like a veil has been pulled aside, and for that I am grateful.

Ask your average person walking down the street what sort of art they find more intimidating, or like less, or don’t know what to make of, and they’ll point to abstract or minimalist art. Show them traditional, formal, naturalistic art, like Bellini’s "Sacred Allegory," art which draws from traditional core Western texts (the Bible, apocrypha, mythology) alongside a Mark Rothko or a Jackson Pollock or a Kazimir Malevich, and they’ll retreat into the Bellini, even though it is one of the most puzzling unsolved mysteries of the art world, a riddle of a picture for which not one reasonable solution has ever been put forward. The Pollock, on the other hand, is just a tangle of dripped paint, the Rothko just a color with a bar of another color on top of it, the Malevich is all white.

Kandel’s work explains this in a simple way. In abstract painting, elements are included not as visual reproductions of objects, but as references or clues to how we conceptualize objects. In describing the world they see, abstract artists not only dismantle many of the building blocks of bottom-up visual processing by eliminating perspective and holistic depiction, they also nullify some of the premises on which bottom-up processing is based. We scan an abstract painting for links between line segments, for recognizable contours and objects, but in the most fragmented works, such as those by Rothko, our efforts are thwarted.

Thus the reason abstract art poses such an enormous challenge to the beholder is that it teaches us to look at art — and, in a sense, at the world — in a new way. Abstract art dares our visual system to interpret an image that is fundamentally different from the kind of images our brain has evolved to reconstruct. Kandel describes the difference between “bottom up” and “top down” thinking. This is basic stuff for neuroscience students, but brand new for art historians. Bottom up thinking includes mental processes that are ingrained over centuries: unconsciously making sense of phenomena, like guessing that a light source coming from above us is the sun (since for thousands of years that was the primary light source, and this information is programmed into our very being) or that someone larger must be standing closer to us than someone much smaller, who is therefore in the distance. Top down thinking, on the other hand, is based on our personal experience and knowledge (not ingrained in us as humans with millennia of experiences that have programmed us). Top down thinking is needed to interpret formal, symbol or story-rich art. Abstraction taps bottom-up thinking, requiring little to no a priori knowledge. Kandel is not the first to make this point. Henri Matisse said, “We are closer to attaining cheerful serenity by simplifying thoughts and figures. Simplifying the idea to achieve an expression of joy. That is our only deed [as artists].” But it helps to have a renowned scientist, who is also a clear writer and passionate art lover, convert the ideas of one field into the understanding of another. The shock for me is that abstraction should really be less intimidating, as it requires no advanced degrees and no reading of hundreds of pages of source material to understand and enjoy. And yet the general public, at least, finds abstraction and minimalism intimidating, quick to dismiss it with “oh, I could do that” or “that’s not art.” We are simply used to formal art; we expect it, and also do not necessarily expect to “understand it” in an interpretive sense. Our reactions are aesthetic, evaluating just two of the three Aristotelian prerequisites for art to be great: it demonstrates skill and it may be beautiful, but we will often skip the question of whether it is interesting, as that question requires knowledge we might not possess.

We might think that “reading” formal paintings, particularly those packed with symbols or showing esoteric mythological scenes, are what require active problem-solving. At an advanced academic level, they certainly do (I racked my brain for years over that Bronzino painting). But at any less-scholarly level, for most museum-goers, this is not the case. Looking at formal art is actually a form of passive narrative reading, because the artist has given us everything our brain expects and knows automatically how to handle. It looks like real life.

But the mind-bending point that Kandel makes is that abstract art, which strips away the narrative, the real-life, expected visuals, requires active problem-solving. We instinctively search for patterns, recognizable shapes, formal figures within the abstraction. We want to impose a rational explanation onto the work, and abstract and minimalist art resists this. It makes our brains work in a different, harder, way at a subconscious level. Though we don’t articulate it as such, perhaps that is why people find abstract art more intimidating, and are hastier to dismiss it. It requires their brains to function in a different, less comfortable, more puzzled way. More puzzled even than when looking at a formal, puzzle painting.

Kandel told The Wall Street Journal that the connection between abstract art and neuroscience is about reductionism, a term in science for simplifying a problem as much as possible to make it easier to tackle and solve. This is why he studied giant sea snails to understand the human brain. Sea snails have just 20,000 neurons in their brains, whereas humans have billions. The simpler organism was easier to study and those results could be applied to humans.

“This is reductionism,” he said, “to take a complex problem and select a central, but limited, component that you can study in depth. Rothko — only color. And yet the power it conveys is fantastic. Jackson Pollock got rid of all form.”

In fact, some of the best abstract artists began in a more formal style, and peeled the form away. Turner, Mondrian and Brancusi, for instance, have early works in a quite realistic style. They gradually eroded the naturalism of their works, Mondrian for instance painting trees that look like trees early on, before abstracting his paintings into a tangle of branches, and then a tangle of lines and then just a few lines that, to him, still evoke tree-ness. It’s like boiling away apple juice, getting rid of the excess water, to end up with an apple concentrate, the ultimate essence of apple-ness. We like to think of abstraction as a 20th century phenomenon, a reaction to the invention of photography. Painting and sculpture no longer had to fulfill the role of record of events, likenesses and people — photography could do that. So painting and sculpture was suddenly free to do other things, things photography couldn’t do as well. Things like abstraction. But that’s not the whole story. A look at ancient art finds it full of abstraction. Most art history books, if they go back far enough, begin with Cycladic figurines (dated to 3300-1100 BC). Abstracted, ghost-like, sort-of-human forms. Even on cave walls, a few lines suggest an animal, or a constellation of blown hand-prints float on a wall in absolute darkness.

Abstract art is where we began, and where we have returned. It makes our brains hurt, but in all the right ways, for abstract art forces us to see, and think, differently.

0 notes