#i have vasari’s lives of the artists

Text

oh good my [checks notes] book on the vatican’s ethnological collection, lil gravies roast beef flavor, and piercing aftercare fine mist will be delivered today

#that’s just today#i have vasari’s lives of the artists#a black nyx lip gloss#a book about the portrait of pope julius ii#and a book on repatriating cultural heritage#all on the way#all the books are used and cheap thank fuck because this is insane rn

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was doing my silly lurking bit in twitter and this gem appeared:

and you know what? I am gonna say it:

His name was Giorgio Vasari , the renaissance painter, and I, personally, fucking hate that guy.

He was the one silly man to bring to modernity (well to the more modern times in the 1500s) the idea that artists had this "natural creative divine talent". It is his goddamn fault that artist is given the Born Genius treatment. Not sure he invented the myth, but he did the whole bit of "this poor little shepherd kid is drawing fruit so realistic with a stick in the mud flies are drawn to his scribbles, God gave him the innate artistic skills to fool nature with his Gift so he must follow his true calling as an Artist" and brought it back to the public imaginary.

You see, back in the more medieval days being a renowned artist was not common or looked after, but then many things happened, the printing press and money flowing to different classes in society, the pictorial interest shifted to imitating nature, blablabla, and, within the renaissance, Giorgio wrote this cursed thing: Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. A selected group of biographies of artists that created this narrative that artists are born and that talent was necessary to be an Excelent artist.

Long story short, this collection of biograpgies was for a long time, the primary source of the biography of many Renaissance artists and the base for writing about artists since "the guy who wrote it was an artist himself so he must be right ", making it the be all end all in terms of who is who in the history of art... And well, it is just full of Florentine and Roman artists that Giorgio liked very much himself. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Giotto, etc, some contemporaries of him, but it also included the ones that lived before him, and he knew nothing about it. Girogio did his research and wrote his book filled with his personal heroes.

My guy Vasari basically invented Art History as a Subject with capital S, but, as all guys set in a historical period, his views were painfully biased. Filling his book with anecdotes that were closer to gossip and in line with the idea of the renaissance at full speed, remarking the existance of this set progressive timeline where art evolves to imitate nature, elevating artists to an exceptional born-talented person who was put on this earth because, idk, the Holy Spirit illuminated them to partake in the adoration of God's perfect creation from the moment they exited the womb by drawing perfectly?? Not sure, I read it long ago. still, you get the point.

But, as we gotta do from our postmodernist perspective, we gotta ask about the context, the point of view: who was writing those biographies and why. And Vasari , helpfully, in his book of Most Excellent Artists... included himself. He positioned himself among his heroes, placing himself in the middle of his own narrative. He said, "Look at them and look at me." He had the political agenda to set his homestate (Florence and Rome ) and himself as the cradle and centre of the Good Arts and "not like those barbarian others. " Even if this belief was widely spread at the time, having it on print solidified it as some kind of undeniable truth. He was the first to write about it, widely publish it and subsequently he fucked up how people wrote about artists for the next centuries.

And if you ask yourself, "Who invented the idea that artists are jealous of each other and compete to get the attention of the rich and powerful and are nasty and cocky about it?" ..it was also him.

Fuck Vasari.

#giorgio vasari#rants in art history and theory#my goddamn professor would be proud of me but would still make my life hell#lini writes#italian men ruining my life since 1550#i would throw hands with him

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Lorenzo’s adolescent years certainly seem to have about them a fairy-tale quality; the intimate correspondence of his brigata is full of allusions to music, dancing, storytelling, and lovemaking. There is the pathos of his doomed love for Lucrezia Donati, to whom many of his juvenile poems are addressed, a young married gentlewoman so compelling that Sigismondo della Stufa wrote to an absent Lorenzo in March 1466 describing how she looked as she left church: “You never saw anything so beautiful, dressed in black and with her head veiled, stepping so gracefully that it was as if the very stones and walls should worship her as she passed. I will say no more, lest you be tempted by sin in this holy season.”

According to Vasari, Andrea himself restored ancient sculpture for the Medici, as Bertoldo and others were to do in the next decade. It would surely have been Lorenzo himself, hardly his father, who commissioned from Verrocchio, as early as the late 1460s, a painted por- trait of the younger Medici’s beloved Lucrezia Donati, which cannot now be identified. Surely this “wooden frame within which is the head of Lucrezia Donati,” mentioned in the well-known list of works done for the Medici for which the artist was not paid, was the same “small painting [tavoletta] in which a woman was depicted” at the foot of which Lorenzo composed one of his early love sonnets addressed to Lucrezia, a self-conscious reference by the young poet to Petrarch’s poems about Simone Martini’s portrait of Laura. It is poignant indeed now to dis- cover that in October 1495 Lucrezia’s son, Niccolò Ardinghelli, bought from the Medici estate for twenty-three large gold florins “a figure or image or painting of his mother,” almost unbearably poignant to think that Lucrezia Donati, who was to live another six years, may have wanted for herself this image commissioned by her Medici lover of thirty years earlier." - F. W. Kent, Lorenzo de' Medici and the Art of Magnificence.

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#italian renaissance#women of renaissance#renaissance italy#renaissance women#renaissance#rinascimento#lucrezia donati#lorenzo il magnifico#lorenzo de' medici#medici#imedici#dvdedit#da vinci's demons#donne della storia#donne nella storia#donneitaliane#donne italiane#lana del rey#lyricsedit#perioddramacentral#period drama costumes#period drama#perioddramasource#perioddramasonly#userthing#usermarcy#laura haddock

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

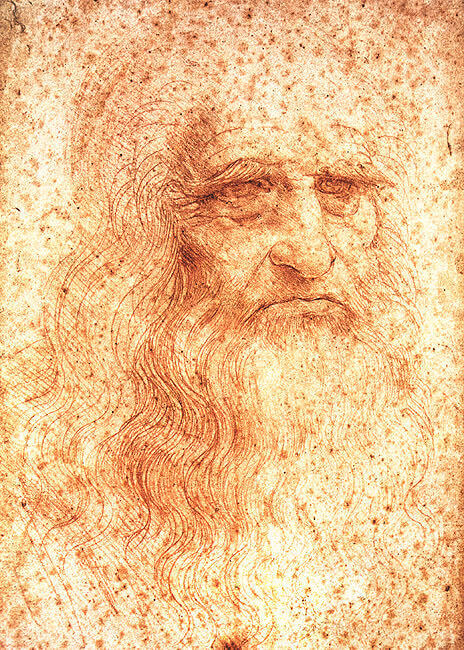

LEONARDO DA VINCI

Whew! Venturing into the city to unearth some cool discoveries, I stumbled upon two absolute gems by the legendary Da Vinci - "The Mona Lisa" and "The Last Supper". Da Vinci, the brainiac son of ser Piero da Vinci, (Giorgio Vasari: "Life of Leonardo da Vinci)” had a knack for everything from arithmetic to art. He was so sharp with numbers that he even left his teacher scratching their head at times. Although music briefly caught his attention, his heart always belonged to his drawings. Leonardo's talent didn't go unnoticed, and with a little nudge from Andrea, his dad finally signed him up for art classes. Fast forward to the iconic Mona Lisa - Da Vinci captured the essence of Francesco del Giocondo's wife in this masterpiece. The enigmatic smile and the captivating gaze of the Mona Lisa have intrigued art lovers and scholars for centuries. The painting's sneaky use of sfumato, a fancy technique that blurs colors like a soft rainbow, shows off Da Vinci's mad skills and eye for detail. And then, there's "The Last Supper," one of Leonardo da Vinci's most iconic masterpieces, captures a moment of profound significance and emotional intensity. The painting, located in the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, depicts Jesus and his twelve disciples during the pivotal moment when Jesus announces that one of them will betray him. Each figure in the scene is rendered with meticulous detail, their expressions and gestures conveying a range of emotions from shock to sorrow. The use of perspective draws the viewer's eye to the central figure of Jesus, whose calm demeanor contrasts with the turmoil around him. This work not only showcases da Vinci's extraordinary skill as an artist but also invites viewers to reflect on themes of loyalty, betrayal, and the human condition. But hold onto your hats - Leonardo wasn't just a painting wizard; he dabbled in anatomy, engineering, and even dreamt of soaring through the skies. His journals, packed with doodles and discoveries, reveal a mind that never took a nap, always on the hunt for answers and new tricks. Strolling around town, bumping into these creations up close felt like catching a live show of a genius whose ideas still rock the world today.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For half a century, the Sernesi family lived in a storied villa overlooking Florence where the Renaissance artist Michelangelo was raised and which he later owned. The property came with several buildings, an orchard and a drawing of a muscular male nude etched on the wall of a former kitchen. Tradition has it that the work was drawn by a young Michelangelo, though scholars are not as sure.

Last year, the Sernesi family sold the villa. Now they want to sell the mural drawing, which was detached from its original location in 1979 so that it could undergo a much-needed restoration. Art historians have identified the figure, etched with charcoal or black chalk on plaster and measuring about 40 by 50 inches, as a “triton,” a god of the sea, or a “satyr,” part man part beast.

Over the decades, the drawing has been loaned as a Michelangelo work to exhibitions in Japan, Canada, China and, most recently, the United States, where it was included in the Metropolitan Museum’s blockbuster 2017 show “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer.” The catalog entry for that exhibition, by Carmen C. Bambach, the Met’s curator of drawings and prints, describes it as “the only surviving manifestation of Michelangelo’s skill as a draftsman in large scale.”

News that the drawing is going on the market is likely to expand what has until now been a rather low-key, academic debate over the authorship of a work that has remained in private hands, and mostly out of the public eye, for the past five centuries.

[Info about the auction house & Italian law that I didn't bother pasting.]

The Sernesis track the drawing’s attribution to Giorgio Vasari, Michelangelo’s contemporary biographer, who wrote that the young artist honed his skills by drawing on “papers and walls,” though Vasari does not give precise indications where. Some visitors to the villa over the centuries wrote of seeing Michelangelo’s doodles there.

When the drawing first began making the rounds in exhibitions, several of the catalog entries attributing the piece to Michelangelo were written by Giorgio Bonsanti, an Italian Renaissance expert who also oversaw the 1979 restoration. “I just can’t imagine another person entering Michelangelo’s house and drawing a figure on the wall of his kitchen,” he said.

We can all agree Joe drew this, right? Joe & Nicky had dinner at Michelangelo's one day, they all had wine, and Joe & Michelangelo got into a debate/argument about who was the better artist. And they settled it by sketching on the walls. Somehow Joe's survives but Michelangelo's doesn't.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"School of Athens" by Raphael

If someday somehow you obtain the power to step into any painting, then I highly suggest that you should take that first step into Raphael’s “School of Athens”. I mean, seriously, it’s where legendary, and some are quite mythical, philosophers and thinkers casually mingle in one massive hall, as if it was the classiest and most epic TED Talk ever.

Raphael basically teleports you straight into the midst of the gathering of the greatest smarties in the history of human civilization. He didn’t merely slap paints on the wall of the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, he was crafting a passionate tribute, or, if I may, a love letter to the exploration of science and knowledge upon the altar of science.

Each character on the fresco was displaying peak spirit of curiosity, wrapped in togas and intellectual banter. At the center of the stage, we can see Plato, holding a copy of his Timaeus, indulging himself in deep conversation with his pupil, Aristotle.

Not to mention how Raphael depicted the Renaissance architectural marvel in the background which, according to Giorgio Vasari in his biography series The Lives of the Artists, was consulted with and inspired by the works of Donato Bramante, an Italian architect that puts up the basic design of St. Peter’s Basilica, which then executed by none other than Michaelangelo Buonarroti. Raphael also paid homage to the Ancient Greek antiquities by putting sculptures of Apollo, the Greek god of light, archery, and music, and Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom.

Raphael perfectly captured the essence of the Renaissance spirit in this work. As we know, the Renaissance was all about reviving the classics, celebrating individuality and humanism, and having a strong will to dive head-first into the pool of knowledge and wisdom. It was a remarkable visual composition that expressed the Renaissance thirst for human discovery.

Quick fact: some of the Renaissance figures were featured in this work, particularly people that were, in some way, Raphael found inspiring or influential. Some of these figures are:

Leonardo da Vinci as Plato

Michelangelo as Heraclitus

Donato Bramante as Euclid

Timoteo Viti (Raphael’s mentor) and Raphael himself

=====

Stay curious, ciao!

Ray

#renaissance#neorenaissance#artwork#art#dark academia#academia#philosophy#greek#raphael#athens#knowledge#wisdom#painting#leonardo#vasari#bramante#michaelangelo

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

"the lives of the artists" aka vasari's art history burn book is the pettiest and funniest primary source i have ever seen in my entire life. a real fucking legacy to leave indeed. as one of the first art historians, he truly was a gossip.

to bela

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Room of Cloudy Whispers

ACT 2 SCENE 3

THE HOUSE: Who are these that fly like a cloud, and like doves to their windows? [1]

The drones,

The drones!

Takeshi keeps fighting the drones, they irritated him. One might call it fear.

It is not worthwhile to argue whether this fear is a servile or a so called filial fear. [2]

In the end, Fear is an acknowledgement of Power [3] states KATI. She is smart. Annoyingly smart one might add.

KATI to HOUSE: So you would wish to have two eyes like city folk and respectable people? [4]

HOUSE: From the street it should look like Heaven. [5] Everything naturally desires to remain in its own state.[6]

TAKESHI is seething with anger.

Heat Heat Heat.

Never has the house been in a state of heaven like appearance. It’s inventions have brought some golden ages, but technology has challenged its inventions and the HOUSE has drowned its sorrows in drinks.

The candles melt away, dripping on velvet cushions.

The HOUSE, the little fallen star, how TAKESHI is phrasing it; gets some of its old glitter back. I want a bubble Bath.

[1] Melanchthon Bucer, Collected Works

[2] Melanchthon Bucer, Collected Works

[3] Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier

[4] Hobbes, On the Citizen

[5] Vasari, The Lives of the Artists

[6] da Vinci, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci

0 notes

Text

Mona Lisa (Do you understand what you're looking at?)

There are few things I'm willing to state definitively, but that this is the most famous painting in the "western" world, I've no doubt. You know the one:

Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci, 1503, oil on panel, 77x53cm

But why? Why is Mona Lisa so famous?

There's many elements to that answer. The first and simplest argument is the Mona Lisa is so very famous because we know so little about it, allowing us to invent mythologies for the work nearly as grand as the ones we invent for its painter. Leonardo da Vinci himself is a heavily mythologized figure, being inextricably linked to the invention of the "Renaissance" and to the invention of the artist as an individual and a genius - both forwarded by Giorgio Vasari's 1550 book, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (a topic worthy of a post unto itself). Of this ubiquitous character in history, this is his most famous, and ubiquitous, work.

And I do mean ubiquitous. Once you start looking for her, you'll find Lisa everywhere - on clothing, mugs, tchotchkes, reproductions, parodies, etc, etc, etc.

Mona Lisa? What are you doing in my falafel?

Another reason historians believe the Mona Lisa has experienced a rise to popularity few (see: no) other works can claim is precisely because it was stolen in the early 20th Century. A worker at the Louvre cut the painting from the frame, and though piece was ultimately recovered, being found under the thief's bed, it was arguably the sensationalized news story of this crime, more than the work of art itself, which launched its following.

(as a fun side note: if you've ever been to see the Mona Lisa in person and were disappointed by the size, rest knowing the painting we see today is indeed smaller than the original - there is believed to have been two columns and a ledge in the original - a difference owing to how many times it has been sliced from the frame)

So Mona Lisa has captured the public's imagination and launched this piece into pop culture stardom and a state of repeated reproduction and familiarity which has bestowed upon it a particular cultural cache.

This next section is the important part, this is why I have titled this rant? essay? Do you understand what you're looking at?

The Mona Lisa is valued as one of the most important works of art today. The Mona Lisa was not considered particularly important, or even particularly good, at the time of its creation. It wasn't even the most noteworthy of da Vinci's works.

Let's work backwards.

How did this work, by a Florentine artist, ended up in Louvre?

Leonardo da Vinci lived in France for a time, completing work for the King, and it is where he ultimately died. All those works in his possession at the time of his death were claimed as property of the King, which were in turn seized by the French State following the French Revolution, and ultimately ended up on display in the Louvre.

This suggests this piece had essentially no viewing audience during da Vinci's lifetime.

Why was it in Leonardo da Vinci's possession at the time of his death?

The sitter has been identified as 24-year-old Italian noblewoman Lisa del Giocondo, and the work was likely a commission by her husband, Florentine silk merchant, Francesco di Bartolomeo del Giocondo, as a celebration of the birth of their second son. That this commission remained in da Vinci's possession suggests it was rejected upon completion.

Why was this portrait rejected by its patron?

This is the fun part: the Mona Lisa was probably rejected (and I say probably because this is pure inference and conjecture) because, for the time and setting, this is an unconventional depiction of a woman: she's presented as androgynous bordering on masculine, aggressive, without the requisite hallmarks of class and station, and, ahem, loose.

We have more extant portraits of women surviving from Florence in the quattrocento leading into the cinquecento than we do of men (approximately five are known of men, compared to 40 of women), and the majority of them have been identified as forming part of a donora or counter-donora (the dowry and counter-dowry) and thus follow specific rhetorical conventions. These paintings are both part of and proof of the economic and material exchange made in a marriage, of which the woman also is and is presented as an object in that exchange - sumptuously dressed and dripping in jewels, expressing the wealth of the families and the size of the dowry.

Now, this portrait is not intended to celebrate a donora, and given Lisa's age, she would have been subject to Florence's sumptuary legislation (until they were married and for three years after, girls were spared from these laws), so it makes some degree of sense that she is depicted in plain clothes and without jewelry (though that may have been taken as offensive by the wealthy patron).

But while her age and married state my excuse her dress, it damns her hair. Virgins and brides could wear their hair loose as a symbol of innocence, but married women were expected to keep their hair decorously concealed as a matter of propriety. That her hair is loose is erotic, it suggests she is loose. The implication is that Lisa has loose morals and is sexually promiscuous. This is scandalous!

(This is why likely why many copies, including Raphael's Pen and Ink Portrait Portrait of a Young Girl, 1505 age her down - if she is younger, everything is forgivable. But not with her apparent age)

The women in conventional portraits of the time are depicted with all the virtues of a woman - chastity, elegance, modesty. Their bodies were contained and limbs controlled, most commonly presented in profile with the eyes averted. But not Lisa! She is in 3/4 frontal view, gazing out at the viewer, in a manner that is a little aggressive. This painting is lifelike, that is, she has weight and volume, it seems as though you can see the blood moving beneath her skin. Rather than being concealed, her humanity is revealed. Her direct gaze, like her loose hair, is challenging and erotic, and coupled with her enigmatic smile she seems to be finding pleasure in her encounter with the viewer. Yet she maintains a sprezzatura, a cold aloofness prized in portraits of men but unheard of in portraits of women. And just look at her hands - for all they are relaxed they are active, set in a rhetorical expression which was typically reserved for portraits of men.

To answer the final question then, my best guess for why this painting was rejected by its patron is because it challenged traditional conventions of womanly presentation and behavior in a manner the patron found insulting, if not obscene.

So, what's my conclusion here? Honestly, this has all been an exercise in my own wonder and mystification. Here is a painting that is frankly radical, was in fact rejected for being too unconventional, that, by virtue of happenstance and coincidence rose to absurd levels of popularity - a state of fame which has served to make this unconventional painting the literal archetype of the conventions of the era.

And I see all these people flocking to the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa because it's a must-do, and I just have to ask, do you understand what you're looking at? Do you see the irony? Do you get how funny this entire story is?

#mona lisa#leonardo da vinci#renaissance art#renaissance#italy#history#art history#early modern europe#louvre#florence italy

0 notes

Photo

This month we are celebrating Sofonisba Anguissola and the novel “The Secret Life of Sofonisba Anguissola” by Melissa Muldoon Melissa Muldoon is known for her portrayal of strong women overcoming the odds to fulfill their dreams, and it is one of the many reasons I find her stories so delightful. The author continues to inspire women through her work with her messages of believing in yourself and staying true to your convictions. “The Secret Life of Sofonisba Anguissola” is her best work yet. — Reader Views (2020) Set in the sixteenth-century, The Secret Life of Sofonisba Anguissola tells the story of a woman’s passion for painting and adventure. In a world where women painters had little to no acknowledgment, she was singled out by Michelangelo and Vasari who recognized and praised her talent. Gaining the Milanese elite’s acclaim, she went on to become court painter to Spanish King Philip II and taught his queen to paint. One can’t live such an extraordinary life without having stories to tell, and tell them Sofonisba does to Sir Anthony Van Dyke, who comes to visit her toward the end of her life. During their meeting, she agrees to reveal her secrets but first challenges the younger painter to find the one lie hidden in her tale. In a saga filled with intrigue, jealousy, buried treasure, unrequited love, espionage, and murder, Sofonisba’s story is played out against the backdrop of Italy, Spain, and Sicily. Throughout her life, she encounters talented artists, authoritative dukes, mad princes, religious kings, spying queens, vivacious viscounts, and dashing sea captains—even a Barbary pirate. But of all the people who fell in love with Sofonisba, only one captured her heart. The painter may have kept many secrets, but only she knows the truth. #SofonisbaAnguissola #SecretLifeSofonisbaAnguissola #Cremona #Sicilia #Michelangelo #StrongWomen #MelissaMuldoon #NovelItaly https://www.instagram.com/p/CoprVsnO-vG/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#sofonisbaanguissola#secretlifesofonisbaanguissola#cremona#sicilia#michelangelo#strongwomen#melissamuldoon#novelitaly

0 notes

Text

Visit to Leonardo da Vinci, 1495

My husband sought to commission a portrait of myself to be hung in our home as a reminder of my beauty even as I grow old. My husband considered many artists but desired to have Leonardo da Vinci paint my likeness after once viewing the beautiful portrait he made of Ginevra de’ Benci.

We traveled by horse and cart to Milan where he was working for the Church after a mutual friend agreed to arrange for us to meet and to talk about what price we could agree upon and if he had the time. Along the way we saw fields of open plow land and people toiling them, we saw herds of goats and sheep (and even when we didn’t see them we could smell them nearby), over the hill country to our destination stopping to rest each night. Our horses were in could shape and we made great time.

On our arrival, we met while he was working on a painting of Christ and his apostles at the Last Supper. Da Vinci stood there lost in contemplation. He had been known to take years to finish his works, starting and stopping them, sometimes not even finishing them at all. He had been like this for many years, potentially always like this. Da Vinci had too much on his mind, my husband could sense this while we discussed the potential for a portrait of myself. But his gifts from God held us in contempt, we were still willing if he would agree. Da Vinci studied me and said that he could not paint my portrait to his likeness because of the immense pressure he faced at the moment from the church. He had a number of unfinished works and other projects and experiments, and he simply realized that he did not possess the amount time necessary to create a portrait for us despite our willingness to pay. The Prior of the place where he had been working was pressing him to finish this work of the Last Supper, we could not blame this other man. Just by looking at the image so far, we could see the importance that this future work of da Vinci would have. My husband and I left to return to Florence without any agreement for a portrait by the great Leonardo da Vinci. On the way we discussed finding a different artist to paint my portrait, one that was much less occupied.

Feinberg, Larry J. The Young Leonardo : Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence. (Cambridge University Press, August 29, 2011). (accessed November 3, 2022)

Vasari, Giorgio. Life of Leonardo da Vinci. Manuscript.London: Philip Lee Warner, 1912-1914. From Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/vasari1.asp. (accessed November 3, 2022)

da Vinci, Leonardo. Portrait of a Man in Red Chalk. 1512, Biblioteca Reale, Turin. JPG, https://www.leonardodavinci.net/self-portrait.jsp#prettyPhoto. (accessed November 24, 2022)

0 notes

Photo

But Sofonisba of Cremona, the daughter of Messer Amilcaro Anguisciuola, has laboured at the difficulties of design with greater study and better grace than any other woman of our time, and she has not only succeeded in drawing, colouring, and copying from nature, and in making excellent copies of works by other hands, but has also executed by herself alone some very choice and beautiful works of painting.

Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

Sofonisba (of Sophonisba) was born in Cremona (at that time, part of the Duchy of Milano, ruled by the Austrian pawn, Francesco II Sforza) around 1532. She was the eldest child of nobleman (but not wealthy) Amilcare Anguissola (also spelled Angussola or Aguisciola) and his second wife, noblewoman Bianca Ponzone. Following Sofonisba, Bianca would give birth to five other daughters (Elena, Lucia, Europa, Annamaria – all future painters - and Minerva, a writer and Latin teacher) and a son, Asdrubale.

Amilcare Anguissola was an art lover and part of the culturally vibrant Cremonese high society. It’s no wonder then that he introduced his daughters to the study of literature, art and music, although he had another much prosaic reason behind it. He couldn’t afford to pay a dowry for six daughters, and so he hoped they could provide for themselves and secure additional incomes to the meagre familial funds.

From 1545 to 1549, Sofonisba studied fine arts at Bernardino Campi’s workshop (although Vasari affirms it was Giulio). When her maestro left Cremona, she moved to study under artist Bernardino Gatti (called il Sojaro).

As an art appreciator, Amilcare must have noticed his daughter’s talent and also thanks to his (perhaps interested) support, he contributed to making Sofonisba well known outside Cremona. He, for example, sent two of her drawings as a gift to the Duke of Ferrara and in 1554 the proud father sent to Michelangelo Buonarroti one of her works, a drawing representing a laughing girl. It’s said Michelangelo appreciated her style but challenged the younger painter to draw a good crying face. She then proceeded to draw and sent to him Fanciullo morso da un gambero, where she sketched her younger brother, Asdrubale, crying because his sister Europa had just pinched him. This earned Sofonisba Michelangelo’s appreciation and guidance. The sketch, alongside Buonarroti’s Cleopatra, was sent to Cosimo I de’ Medici.

Amilcare introduced Sofonisba’s art to some of the most notorious Italian dynasties, such as Gonzaga, Este and Farnese, on whose behalf she painted some portraits.

In 1557 she stayed for about a month in Piacenza to study miniature under the great artist Giulio Clovio, who also showed her many masterpieces, like Raffaello’s Madonna Sistina (now in Dresden). In 1557, she was commissioned a portrait of Massimiliano Stampa, the young son of Ermes Stampa second marquis of Soncino, one of the most important noble families in Lombardia. By the time she finished the portrait (1558), Ermes had died and Massimiliano had become the third Marquis.

Sofonisba’s life changed dramatically in 1559. In June of that year, 14-years old Élisabeth of Valois became Felipe II of Spain’s third wife. The Duke of Alba, at that time Governor of the Duchy of Milan, convinced the Spanish sovereign to hire Sofonisba (already a famous artist at European level) to give the young new Queen painting lessons. The whole Anguissola family moved then to Milan, where they stayed, personal guests at the Governor’s mansion for about two months before Sofonisba left for Madrid, where she arrived at the beginning of 1560.

The artist and the teen Queen became fast friends. She held the office of official portrait painter as well as lady-in-waiting and art teacher for the Queen and her two daughters, the princesses Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catalina Micaela, for almost twenty years, enjoying the Royal couple’s sponsorship and a very generous annual pension of 100 ducats. It is known she used part of her salary to support her family back in Cremona, especially following her father’s death in 1573. Sofonisba financially helped her brother Asdrubale, to the point of granting him an annual stipend of 800 lire and, later in 1606, she requested that her lifetime pension from the Spanish crown be transferred to him.

During her Spanish period, she portrayed many royal members, like Élisabeth of Valois, the two princesses, the King, Juana Regent of Spain, Don Carlos (whose original portrait, sadly, is lost, but were made many copies), Margherita of Parma, and Anna of Austria, who’ll become Queen of Spain after Élisabeth of Valois’s death in childbirth in 1568.

Following his third wife’s death, Felipe II became interested in marrying off Sofonisba (who was already 36 at the time) to one of his noblemen, perhaps to keep her anchored in the Spanish court, and provided her a dowry of 12 thousands scudi plus an annual income of 1000 ducati. In 1571 she married by proxy Sicilian nobleman Fabrizio Moncada Pignatelli. Fabrizio was the second son of Francesco I Moncada de Luna, earl of Caltanissetta and prince of Paternò, and Caterina Pignatelli Carafa. In that same year, his older brother Cesare had died, leaving his title and possessions to his 2-years old son Francesco II. Fabrizio had then stepped in to act as regent for his infant nephew and was named governor of the city of Paternò (nearby Catania).

It is not known for sure when she had moved to her husband’s Sicilian domains, what is certain is that in 1578 her brother Asdrubale had meant to join her in Palermo. At that time Sofonisba was already a widow (and childless) since Fabrizio had died that same year in a pirate attack off the coast near Capri. Moncada had drowned after desperately trying to defend his ship. The painting representing the Madonna dell’Itria, preserved in the Church of Santissima Annunziata of Paternò, dates back to this period.

By the end of 1579, the widowed Sofonisba sailed from Palermo together with her brother headed for her native Cremona. Surely she would have never thought another chapter of her life was about to begin. During the journey, she met and fell in love with the Genoese sea captain Orazio Lomellini, widowed with a son. Lomellini was the illegitimate son of wealthy shipowner Nicolò and some 15 years younger than Sofonisba. Because of bad weather, the ship had to dock in Livorno, from there Orazio escorted Sofonisba and Asdrubale in Pisa since in Livorno they couldn’t find a proper accommodation. Defying her brother’s opposition, she married Orazio and moved with him to Genova, where we can find her surely in 1584. This marriage too would be childless, but it appears Sofobisba got along quite well with her step-son, Giulio.

She’ll live in Genova for about 30 years, becoming the city’s leader portrait painter and hosting in her house many famous artists and literates. In 1585 she might have traveled with her husband all the way to Savona where she paid homage to her former pupil, Catalina Micaela of Spain, headed for Torino to marry Carlo Emanuele I Duke of Savoy. It has been hinted Anguissola had often been a guest of the new Duchess of Savoy from then on, although this hasn’t been yet proved.

The Portrait of three kids, the Game of tric-trac, the Portrait of a Lady of the Galleria Borghese presumably date back to this period. In 1599 she met another one of her august pupils, Isabella Clara Eugenia had stopped in Genova to meet her former art teacher on her way to Brussels to marry Archduke Albert VII of Austria. On this occasion Sofonisba painted the Spanish princess and the artwork was later sent as a gift to Isabella Clara’s half-brother, Felipe III.

In 1615 the Lomellini couple decided to move to Sicily, where Orazio would better pursue his business deals and in Palermo they bought a mansion in strata Pilerij nearby Palazzo Branciforte. Sofonisba was already over 80 and her eyesight had started to fail her and in 1620 she painted her last self-portrait. She compensated her loss of sight by becoming a patron of the arts and her mind showed to be sharp even past the 90s. On July 12th, 1624 Sofonisba was visited by a young Anthony van Dyck, her successor as official portrait painter for the Spanish court, who was impressed by her clear-headness. He recorded their conversation and sketched the old artist.

On November 16th, 1625 she died of old age. She was buried in San Giorgio dei Genovesi, church of the Genoan community of Palermo. Seven years later, in 1632, on what would have been her 100th birthday, her widower Orazio placed an inscription which reads:

“To Sofonisba, my wife, who is recorded among the illustrious women of the world, outstanding in portraying the images of man. Orazio Lomellino, in sorrow for the loss of his great love, in 1632, dedicated this little tribute to such a great woman.”

Sources

Fortune Jane, Michelangelo Buonarroti and his women

Nicotra Alfio, Sofonisba Anguissola. Dalla Sicilia alla corte dei Savoia

Romanini Angiola Maria, ANGUISSOLA, Sofonisba, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol 3

Ross Sarah Gwyneth, Anguissola, Sofonisba (b. ca. 1532–1625), in Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance: Italy, France, and England, p. 14-18

Vasari Giorgio, The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

#women#history#historicwomendaily#historical women#art#sofonisba anguissola#orazio lomellini#fabrizio moncada pignatelli#spanish sicily#Palermo#province of palermo#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is Architecture? What Are the 5 Senses Of Architecture?

What Is Architecture

Buildings or other structures may be planned, designed, and built in a process called architecture. Buildings that are the physical manifestation of architectural works are often regarded as works of art and cultural icons. Architecture from past civilizations is often used to define them now.

The custom, which dates back to the ancient past, has been employed by civilizations on all seven continents as a means of displaying their cultural identity. Because of this, architecture is seen as a type of art. Since antiquity, books about architecture have been written. The Roman architect Vitruvius’ book De architectura, written in the first century AD, is the first known work on architectural ideas. Vitruvius claimed that a good structure includes firmitas, utilitas, and venustas (durability, utility, and beauty).

Centuries later, Leon Battista Alberti expanded on these concepts, considering beauty to be a property of structures that can be determined by their proportions. In his 16th-century book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Giorgio Vasari introduced the concept of style in the Western arts. Louis Sullivan said that ���shape follows function” in the 19th century.

The term “function” started to take the place of the traditional “utility,” and it came to mean not simply something useful but also anything with artistic, psychological, and cultural components. In the latter half of the 20th century, the concept of sustainable architecture first emerged.

Asia as a whole was inspired by Indian and Chinese architecture, and Buddhist architecture, in particular, included several regional influences. In reality, throughout the European Middle Ages, cathedrals and abbeys in the Romanesque and Gothic styles evolved on a pan-European scale, but the Renaissance favored Classical forms used by renowned builders.

Later, the functions of engineers and architects were divided. After World War I, an avant-garde movement that aimed to create an entirely new aesthetic suitable for a brand-new post-war social and economic order centered on serving the demands of the middle and working classes gave birth to modern architecture. Modern methods, supplies, and geometric shapes were emphasized, opening the way for high-rise superstructures.

Due to the disillusionment of many architects with modernism, which they saw as anti-historical and anti-aesthetic, postmodern and contemporary architecture emerged. The practice of architectural building has grown to include anything from ship design to interior design throughout the years.

De architectura, written by the Roman architect Vitruvius in the first century AD, is the first extant written work on the topic of architecture. According to Vitruvius, a good structure should adhere to the three firmitas, utilitas, and venustas principles, which are also known as firmness, commodity, and luxury in their original Latin. An equivalent in modern English would be:

Durability – a building should stand up robustly and remain in good condition

Utility – it should be suitable for the purposes for which it is used

Beauty – it should be aesthetically pleasing

According to Vitruvius, the architect should make every effort to achieve each of these three qualities. In his work De re aedificatoria, which expands on Vitruvius’ theories, Leon Battista Alberti considered adornment as secondary to proportion in the pursuit of beauty. Alberti believed that the Golden mean, the idealized human form, was guided by the laws of proportion. The most significant feature of beauty, therefore, was founded on universal, recognizable truths and was an intrinsic part of an item rather than something imposed superficially. It wasn’t until Giorgio Vasari’s writings in the 16th century that the idea of style in the arts was formed.

5 Sense of Architecture:

Here is the list of 5 senses of architecture.

1. The Eye and Sight

Historically, the eye and sight have dominated architectural practice. The other senses, such as sound, touch (including proprioception, kinesthesis, and the vestibular sense), smell, and in rare instances, taste, have, nevertheless, begun to get more attention from architects and designers in recent years. The expanding knowledge of the multimodal nature of the human mind that has come from the area of cognitive neuroscience research has not yet received much attention.

The phrase has been used to describe the primal reaction elicited by the interaction of architectural components including form, material, size and proportion, light and shadow, color, building techniques, etc. Each sense makes a contribution that is both equal in strength and distinct from the others.

2. The Sense of Sound

Architecture is a complicated way of perceiving sound, and every structure has one. The sound of flipping pages is accentuated when one enters a silent library; in a church, muttered prayers are delicately recorded. Depending on the properties of the sound, materials, and textures with a tendency to reflect, change, absorb, channel, or enhance sound may help shape a place. Unlike eyesight, these omnidirectional biological phenomena are not confined; because of their fluid, horizonless character, it is free to wander anywhere it wants.

3. The Eyes of The Skin

This explains why humans see wood as a more aesthetically pleasing material and consider concrete to be a more harsh one. In the past, this phenomenon was only sparingly explored, and it is now mostly ignored in built environment design. But it still has a strong capacity to affect how space is perceived. The tactile world is also renowned for its capacity to hold onto memories from the past. Pallasmaa describes its potential as having a deep connection with history, custom, and vestige.

4. The Sense of Smell

The sense of smell is understood by all people, yet the feelings and memories it brings back are unique to each person. With only a tiny sniff, the nose is said to be the most effective memory creator, connecting the past and present. Some fragrances are deeply ingrained in our memory and difficult to recall on demand; they often need a trigger. This memory often fills the mind with memories connected to the particular fragrance; images that are ordinarily unreachable.

5. The Sense of Touch

The primary sensory organ for spatial awareness is thought to be the eye, which is notorious for being a “gullible” sense. Since ancient times, ornamentation, symmetry, strict proportions, rhythm, and patterns have all been used to address the visual sense in our constructed world. Making aesthetics the first priority results in structures that lack soul since the material selection is only justified in terms of aesthetic criteria and does not appeal to the senses of hearing, touching, or smell. Design that appeals to all the senses creates an experience that goes well beyond the visible.

#architecture#construction#construction management#civil engineering#home & lifestyle#interiors#building#safety

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’ve been meaning to make a masterpost with a list of books and articles for people interested in the Italian Renaissance - so, behold! These are taken mostly from my own bookshelf, syllabi of classes I’ve taken, and bibliographies I’ve compiled for papers I’ve written. I’ve tried to provide a broader overview of the Renaissance with more general topics, and not to give books that are too incredibly specific and not relevant unless you’re working specifically in topic. I’ve also tried to find PDFs or links for anything that you can access online.

I hope this is useful for anyone who’s interested in this period, and I will always be happy to answer questions or try to provide sources for more specific topics!

** indicates a primary source

General Reading.

The Renaissance in Europe by Margaret L. King

**The Civilization of the Italian Renaissance: A Sourcebook by Kenneth Bartlett

Florence and Beyond: Culture, Society and Politics in Renaissance Italy : Essays in Honour of John M. Najemy, ed. David S. Peterson and Daniel E. Bornstein | Google Books

The Renaissance: Italy and Abroad, ed. John Jeffries Martin | Google Books

Daily Life and Culture, Public and Private.

**The Book of the Courtier by Baldassare Castiglione | English PDF

Public Life in Renaissance Florence by Richard Trexler

Friendship, Love, and Trust in Renaissance Florence by Dale Kent | JSTOR

Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortune, and Fine Clothing by Carole Collier Frick | Google Books

Household and Lineage in Renaissance Florence: The Family Life of the Capponi, Ginori and Rucellai by Francis William Kent | JSTOR

“Did Women Have a Renaissance?” by Joan Kelly | PDF

Politics and Diplomacy.

**The Online Tratte (Election Records) of Office Holders, 1282-1532

Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livy by Niccolò Machiavelli || English: PDF | Archive.org || Italian: PDF

The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli || English: PDF | Archive.org | Audiobook || Italian: PDF | Project Gutenberg

Note: the Prince is not really representative of political ideology in the Italian Renaissance. I would actually recommend the Discourses more highly because of how they explore the reality, rather than the possible or ideal, of Italian politics. For Machiavelli’s works, I really like the Allan Gilbert translations, published as The Chief Works and Others

The Cambridge Companion to Machiavelli, ed. John Najemy

“The Dialogue of Power in Florentine Politics” by John Najemy, in The Renaissance: Italy and Abroad, ed. Martin| Google Books

The Florentine Magnates: Lineage and Faction in a Medieval Commune by Carol Lansing | JSTOR

Economics.

The Economy of Renaissance Florence by Richard Goldthwaite

Medici Money by Tim Parks

**The Online Catasto (Tax Records) of 1427-29

Classic Works. Some of these are now considered out-of-date, but they have done a lot to inform the current work on the Italian Renaissance.

The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy by Jacob Bruckhardt | PDF | Project Gutenberg

The Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance by Hans Baron | Library Access

Paleography and Manuscript Studies.

Dictionary of Latin and Italian Abbreviations/Dizionario di Abbreviature Latine e Italiane/Lexicon Abbriviaturarum by Adriano Cappelli – an absolute must-have for the would-be paleographer!! | Archive.org

Latin Paleography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages by Bernhard Bischoff

A Guide to Western Historical Scripts from Antiquity to 1600 by Michelle P. Brown

Introduction to Manuscript Studies by Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham

Art History.

**The Lives of the Artists by Giorgio Vasari - a must have the Renaissance art historian, but also just a pleasure to read

**On Painting/De pictura by Leon Battista Alberti | Latin | Italian | English Excerpts

There are a lot of great works on individual artists, topics, or works of art, so it would be too much to list them all here! I didn’t use a single textbook to start my study of Italian art - it’s very easy to find things in this topic!

The Medici.

The House of Medici: Its Rise and Fall by Christopher Hibbert

The Lives of the Early Medici as Told Through Their Correspondence, ed. Janet Ross | Archive.org

Magnifico: The Brilliant Life and Violent Times of Lorenzo de’ Medici by Miles J. Unger

The Life of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Called the Magnificent by William Roscoe - Slightly outdated now, but a classic work, and includes some relevant primary sources | Archive.org

April Blood by Lauro Martines

The Montefeltro Conspiracy by Marcello Simonetta

Inventari medicei, 1417-1465 : Giovanni di Bicci, Cosimo e Lorenzo di Giovanni, Piero di Cosimo, ed. Marco Spallanzani

Libro d'inventario dei beni di Lorenzo il Magnifico, ed. Marco Spallanzani and Giovanna Gaeta Bertelà

Lorenzo de' Medici at Home: The Inventory of the Palazzo Medici in 1492, ed. Richard Stapleford

#letters from the authoress#queen of the quattrocento#renaissance#italian renaissance#also people please free to add or if tell me if you find any other online versions#bibliography#original#stat rosa pristina nomine

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

As the years passed, I learned to think of dreams as an integral part of life. There are dreams that, because of their sensory intensity, their realism or precisely their lack of realism, deserve to be introduced into autobiography, just as much as events that were actually lived through. Life begins and ends in the unconscious; the actions we carry out while fully lucid are only little islands in an archipelago of dreams. No existence can be completely rendered in its happiness or its madness without taking into account oneiric experiences. It’s Calderón de la Barca’s maxim reversed: it’s not a matter of thinking that life is a dream, but rather of realizing that dreams are also a form of life. It is just as strange to think, like the Egyptians, that dreams are cosmic channels through which the souls of ancestors pass in order to communicate with us, as to claim, as some of the neurosciences do, that dreams are a “cut-and-paste” of elements experienced by the brain during waking life, elements that return in the dream’s REM phase, while our eyes move beneath our eyelids, as if they were watching. Closed and sleeping, eyes continue to see. Therefore, it is more appropriate to say that the human psyche never stops creating and dealing with reality, sometimes in dreams, sometimes in waking life.

Whereas over the course of the past few months my waking life has been, to use the euphemistic Catalan expression, “good, so long as we don’t go into details,” my oneiric life has had the power of a novel by Ursula K. Le Guin. During one of my recent dreams, I was talking with the artist Dominique González-Foerster about my problem of geographic dislocation: after years of a nomadic life, it is hard for me to decide on a place to live in the world. While we were having this conversation, we were watching the planets spin slowly in their orbits, as if we were two giant children and the solar system were a Calder mobile. I was explaining to her that, for now, in order to avoid the conflict that the decision entailed, I had rented an apartment on each planet, but that I didn’t spend more than a month on any one of them, and that this situation was economically and physically unsustainable. Probably because she is the creator of the Exotourisme project, Dominique in this dream was an expert on extraterrestrial real-estate management. “If I were you, I’d have an apartment on Mars and I’d keep a pied-à-terre on Saturn,” she was saying, showing a great deal of pragmatism, “but I’d get rid of the Uranus apartment. It’s much too far away.”

Awake, I don’t know much about astronomy; I don’t have the slightest idea of the positions or distances of the different planets in the solar system. But I consulted the Wikipedia page on Uranus: it is in fact one of the most distant planets from Earth. Only Neptune, Pluto, and the dwarf planets Haumea, Makemake, and Eris are farther away. I read that Uranus was the first planet discovered with the help of a telescope, eight years before the French Revolution. With the help of a lens he himself had made, the astronomer and musician William Herschel observed it one night in March in a clear sky, from the garden of his house at 19 New King Street, in the city of Bath. Since he didn’t yet know if it was a huge star or a tailless comet, they say that Herschel called it “Georgium Sidus,” the Georgian Star, to console King George III for the loss of the British colonies in America: England had lost a continent, but the King had gained a planet. Thanks to Uranus, Herschel was able to live on a generous royal pension of two hundred pounds a year. Because of Uranus, he abandoned both music and the city of Bath, where he was a chapel organist and director of public concerts, and settled in Windsor so that the King could be sure of his new conquest by observing it through a telescope. Because of Uranus, they say, Herschel went mad, and spent the rest of his life building the largest telescope of the eighteenth century, which the English called “the monster.” Because of Uranus, they say, Herschel never played the oboe again. He died at the age of eighty-four: the number of years it takes for Uranus to go around the sun. They say that the tube of his telescope was so wide that the family used it as a dining hall at his funeral.

Uranus is what astrophysicists call a “gas giant.” Made up of ice, methane, and ammonia, it is the coldest planet in the solar system, with winds that can exceed nine hundred kilometers per hour. In short, the living conditions are not especially suitable. So Dominique was right: I should leave the Uranus apartment.

But dream functions like a virus. From that night forward, while I’m awake, the sensation of having an apartment on Uranus increases, and I am more and more convinced that the place I should live is over there.

For the Greeks, as for me in this dream, Uranus was the solid roof of the world, the limit of the celestial vault. Uranus was regarded as the house of the gods in many Greek invocation rituals. In mythology, Uranus is the son that Gaia, the Earth, conceived alone, without insemination or coition. Greek mythology is at once a kind of retro sci-fi story anticipating in a do-it-yourself way the technologies of reproduction and bodily transformation that will appear throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; and at the same time a kitschy TV series in which the characters give themselves over to an unimaginable number of relationships outside the law. Thus Gaia married her son Uranus, a Titan often represented in the middle of a cloud of stars, like a sort of Tom of Finland dancing with other muscle-bound guys in a techno club on Mount Olympus. From the incestuous and ultimately not very heterosexual relationships between heaven and earth, the first generation of Titans were born, including Oceanus (Water), Chronos (Time), and Mnemosyne (Memory) … Uranus was both the son of the Earth and the father of all the others. We don’t quite know what Uranus’s problem was, but the truth is that he was not a good father: either he forced his children to remain in Gaia’s womb, or he threw them into Tartarus as soon as they were born. So Gaia convinced one of her children to carry out a contraceptive operation. You can see in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence the representation that Giorgio Vasari made in the sixteenth century of Chronos castrating his father Uranus with a scythe. Aphrodite, the goddess of love, emerged from Uranus’s amputated genital organs … which could imply that love comes from the disjunction of the body’s genital organs, from the displacement and externalization of genital force.

This form of nonheterosexual conception, cited in Plato’s Symposium, was the inspiration for the German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs to come up with the word Uranian [Urning] in 1864 to designate what he called relations of the “third sex.” In order to explain men’s attraction to other men, Ulrichs, after Plato, cut subjectivity in half, separated the soul from the body, and imagined a combination of souls and bodies that authorized him to reclaim dignity for those who loved against the law. The segmentation of soul and body reproduces in the domain of experience the binary epistemology of sexual difference: there are only two options. Uranians are not, Ulrich writes, sick or criminal, but feminine souls enclosed in masculine bodies attracted to masculine souls.

This is not a bad idea to legitimize a form of love that, at the time, could get you hanged in England or in Prussia, and that, today, remains illegal in seventy-four countries and is subject to the death penalty in thirteen, including Nigeria, Pakistan, Iran, and Qatar; a form of love that constitutes a common motive for violence in family, society, and police in most Western democracies.

Ulrichs does not make this statement as a lawyer or scientist: he is speaking in the first person. He does not say “there are Uranians,” but “I am a Uranian.” He asserts this, in Latin, on August 18, 1867, after having been condemned to prison and after his books have been banned by an assembly of five hundred jurists, members of the German Parliament, and a Bavarian prince—an ideal audience for such confessions. Until then, Ulrichs had hidden behind the pseudonym “Numa Numantius.” But from that day on, he speaks in his own name, he dares to taint the name of his father. In his diary, Ulrichs confesses he was terrified, and that, just before walking onto the stage of the Grand Hall of the Odeon Theater in Munich, he had been thinking about running away, never to return. But he says he suddenly remembered the words of the Swiss writer Heinrich Hössli, who a few years before had defended sodomites (though not, however, speaking in his own name): “Two ways lie before me,” Hössli wrote, “to write this book and expose myself to persecution, or not to write it and be full of guilt until the day I am buried. Of course I have encountered the temptation to stop writing … But before my eyes appeared the images of the persecuted and the wretched prospect of such children who have not yet been born, and I thought of the unhappy mothers at their cradles, rocking their cursed yet innocent children! And then I saw our judges with their eyes blindfolded. Finally, I imagined my gravedigger slipping the cover of my coffin over my cold face. Then, before I submitted, the imperious desire to stand up and defend the oppressed truth possessed me … And so I continued to write with my eyes resolutely averted from those who have worked for my destruction. I do not have to choose between remaining silent or speaking. I say to myself: speak or be judged!”

Ulrichs writes in his journal that the judges and Parliamentarians seated in Munich’s Odeon Hall cried out, as they listened to his speech, like an angry crowd: End the meeting! End the meeting! But he also notes that one or two voices were raised to say: Let him continue! In the midst of a chaotic tumult, the President left the theater, but some Parliamentarians remained. Ulrichs’s voice trembled. They listened.

But what does it mean to speak for those who have been refused access to reason and knowledge, for us who have been regarded as mentally ill? With what voice can we speak? Can the jaguar or the cyborg lend us their voices? To speak is to invent the language of the crossing, to project one’s voice into an interstellar expedition: to translate our difference into the language of the norm; while we continue, in secret, to practice a strange lingo that the law does not understand.

So Ulrichs was the first European citizen to declare publicly that he wanted to have an apartment on Uranus. He was the first mentally ill person, the first sexual criminal to stand up and denounce the categories that labeled him as sexually and criminally diseased.

He did not say, “I am not a sodomite.” On the contrary, he defended the right to practice sodomy between men, calling for a reorganization of the systems of signs, for a change of the political rituals that defined the social recognition of a body as healthy or sick, legal or illegal. He invented a new language and a new scene of enunciation. In each of Ulrichs’s words addressed from Uranus to the Munich jurists resounds the violence generated by the dualist epistemology of the West. The entire universe cut in half and solely in half. Everything is heads or tails in this system of knowledge. We are human or animal. Man or woman. Living or dead. We are the colonizer or the colonized. Living organism or machine. We have been divided by the norm. Cut in half and forced to remain on one side or the other of the rift. What we call “subjectivity” is only the scar that, over the multiplicity of all that we could have been, covers the wound of this fracture. It is over this scar that property, family, and inheritance were founded. Over this scar, names are written and sexual identities asserted.

On May 6, 1868, Karl Maria Kertbeny, an activist and defender of the rights of sexual minorities, sent a handwritten letter to Ulrichs in which for the first time he used the word homosexual to refer to what his friend called “Uranians.” Against the antisodomy law promulgated in Prussia, Kertbeny defended the idea that sexual practices between people of the same sex were as “natural” as the practices of those he calls—also for the first time—“heterosexuals.” For Kertbeny, homosexuality and heterosexuality were just two natural ways of loving. For medical jurisprudence at the end of the nineteenth century, however, homosexuality would be reclassified as a disease, a deviation, and a crime.

I am not speaking of history here. I am speaking to you of your lives, of mine, of today. While the notion of Uranianism has gone somewhat astray in the archives of literature, Kertbeny’s concepts would become authentic biopolitical techniques of dealing with sexuality and reproduction over the course of the twentieth century, to such an extent that most of you continue to use them to refer to your own identity, as if they were descriptive categories. Homosexuality would remain listed until 1975 in Western psychiatric manuals as a sexual disease. This remains a central notion, not only in the discourse of clinical psychology, but also in the political languages of Western democracies.

When the notion of homosexuality disappeared from psychiatric manuals, the notions of intersexuality and transsexuality appear as new pathologies for which medicine, pharmacology, and law suggest remedies. Each body born in a hospital in the West is examined and subjected to the protocols of evaluation of gender normality invented in the fifties in the United States by the doctors John Money and John and Joan Hampson: if the baby’s body does not comply with the visual criteria of sexual difference, it will be submitted to a battery of operations of “sexual reassignment.” In the same way, with a few minor exceptions, neither scientific discourse nor the law in most Western democracies recognizes the possibility of inscribing a body as a member of human society unless it is assigned either masculine or feminine gender. Transsexuality and intersexuality are described as psychosomatic pathologies, and not as the symptoms of the inadequacy of the politico-visual system of sexual differentiation when faced with the complexity of life.

How can you, how can we, organize an entire system of visibility, representation, right of self-determination, and political recognition if we follow such categories? Do you really believe you are male or female, that we are homosexual or heterosexual, intersexed or transsexual? Do these distinctions worry you? Do you trust them? Does the very meaning of your human identity depend on them? If you feel your throat constricting when you hear one of these words, do not silence it. It’s the multiplicity of the cosmos that is trying to pierce through your chest, as if it were the tube of a Herschel telescope.

Let me tell you that homosexuality and heterosexuality do not exist outside of a dualistic, hierarchical epistemology that aims at preserving the domination of the paterfamilias over the reproduction of life. Homosexuality and heterosexuality, intersexuality and transsexuality do not exist outside of a colonial, capitalist epistemology, which privileges the sexual practices of reproduction as a strategy for managing the population and the reproduction of labor, but also the reproduction of the population of consumers. It is capital, not life, that is being reproduced. These categories are the map imposed by authority, not the territory of life. But if homosexuality and heterosexuality, intersexuality and transsexuality, do not exist, then who are we? How do we love? Imagine it.

Then, I remember my dream and I understand that my trans condition is a new form of Uranism. I am not a man and I am not a woman and I am not heterosexual I am not homosexual I am not bisexual. I am a dissident of the sex-gender system. I am the multiplicity of the cosmos trapped in a binary political and epistemological system, shouting in front of you. I am a Uranian confined inside the limits of techno-scientific capitalism.

Like Ulrichs, I am bringing no news from the margins; instead, I bring you a piece of horizon. I come with news of Uranus, which is neither the realm of God nor the sewer. Quite the contrary. I was assigned a female sex at birth. They said I was lesbian. I decided to self-administer regular doses of testosterone. I never thought I was a man. I never thought I was a woman. I was several. I didn’t think of myself as transsexual. I wanted to experiment with testosterone. I love its viscosity, the unpredictability of the changes it causes, the intensity of the emotions it provokes forty-eight hours after taking it. And, if the injections are regular, its ability to undo your identity, to make organic layers of the body emerge that otherwise would have remained invisible. Here as everywhere, what matters is the measure: the dosage, the rhythm of injections, the order of them, the cadence. I wanted to become unrecognizable. I wasn’t asking medical institutions for testosterone as hormone therapy to cure “gender dysphoria.” I wanted to function with testosterone, to experience the intensity of my desire through it, to multiply my faces by metamorphosing my subjectivity, creating a body that was a revolutionary machine. I undid the mask of femininity that society had plastered onto my face until my identity documents became ridiculous, obsolete. Then, with no way out, I agreed to identify myself as a transsexual, as a “mentally ill person,” so that the medico-legal system would acknowledge me as a living human body. I paid with my body for the name I bear.

By making the decision to construct my subjectivity with testosterone, the way the shaman constructs his with plants, I take on the negativity of my time, a negativity I am forced to represent and against which I can fight only from this paradoxical incarnation, which is to be a trans man in the twenty-first century, a feminist bearing the name of a man in the #MeToo movement, an atheist of the hetero-patriarchal system turned into a consumer of the pharmacopornographic industry. My existence as a trans man constitutes at once the acme of the sexual ancien régime and the beginning of its collapse, the climax of its normative progression and the signal of a proliferation still to come.

I have come to talk to you—to you and to the dead, or rather, to those who live as if they were already dead—but I have come especially to talk to the cursed, innocent children who are yet to be born. Uranians are the survivors of a systematic, political attempt at infanticide: we have survived the attempt to kill in us, while we were not yet adults, and while we could not defend ourselves, the radical multiplicity of life and the desire to change the names of all things. Are you dead? Will they be born tomorrow? I congratulate you, belatedly or in advance.

I bring you news of the crossing, which is the realm of neither God nor the sewer. Quite the contrary. Do not be afraid, do not be excited, I have not come to explain anything morbid. I have not come to tell you what a transsexual is, or how to change your sex, or at what precise instant a transition is good or bad. Because none of that would be true, no truer than the ray of afternoon sun falling on a certain spot on the planet and changing according to the place from which it is seen. No truer than that the slow orbit described by Uranus as it revolves above the Earth is yellow. I cannot tell you everything that goes on when you take testosterone, or what that does in your body. Take the trouble to administer the necessary doses of knowledge to yourself, as many as your taste for risk allows you.

I have not come for that. As my indigenous Chilean mother Pedro Lemebel said, I do not know why I come, but I am here. In this Uranian apartment that overlooks the gardens of Athens. And I’ll stay a while. At the crossroads. Because intersection is the only place that exists. There are no opposite shores. We are always at the crossing of paths. And it is from this crossroad that I address you, like the monster who has learned the language of humans.

I no longer need, like Ulrichs, to assert that I am a masculine soul enclosed in a woman’s body. I have no soul and no body. I have an apartment on Uranus, which certainly places me far from most earthlings, but not so far that you can’t come see me. Even if only in dream …

79 notes

·

View notes

Note

ima need that list of the 50 books u have on leonardo

here is my leonardo specific collection. there are some others i have that i couldn’t find on goodreads or couldn’t remember since i’m currently separated from all my books:

the artist, the philosopher, and the warrior

leonardo da vinci

leonardo’s notebooks

leonardo: the artist and the man

vasari’s lives of the artists

leonardo da vinci (frank zöllner)

there’s also a wider collection i have about the renaissance in general, a few books about the medici and machiavelli, a book on the borgias, and some about renaissance women. when i’m back in my home and have bought a bookshelf, i could probably do an updated collection!!

11 notes

·

View notes