#humanist cinema

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

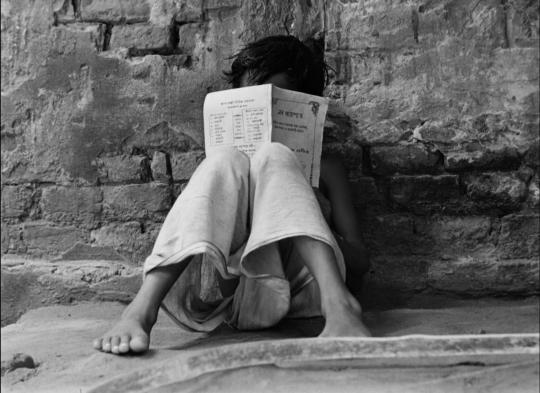

Pather Panchali (1955) Directed by Satyajit Ray

#pather panchali#satyajit ray#1955#indian cinema#bengali cinema#realism#humanist cinema#coming of age#rural life#neorealism#austerity and beauty#family and struggle#visual poetry#subrata mitra#bimal roy influence#cinema of emotions#nature and innocence#soulful storytelling#life and hardship#classic world cinema#arthouse film#existential journey#timeless masterpiece#50s cinema#essential films

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

VIFF 2023 | Top 10 Films

1) Evil Does Not Exist (dir. Ryûsuke Hamaguch)

2) Anatomy of a Fall (dir. Justine Triet)

3) The Boy and the Heron (dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

4) Priscilla (dir. Sofia Coppola)

5) The Royal Hotel (dir. Kitty Green)

6) La Chimera (dir. Alice Rohrwacher)

7) Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person (dir. Ariane Louis-Seize)

8) How to Have Sex (dir. Molly Manning Walker)

9) Union Street (dir. Jamila Pomeroy)

10) Seagrass (dir. Meredith Hama-Brown)

#rick chung#viff#viff 2023#film festival#movies#features#reviews#media#film#films#cinema#movie#film review#movie review#evil does not exist#the boy and the heron#boy and the heron#anatomy of a fall#priscilla#priscilla movie#the royal hotel#royal hotel#la chimera#humanist vampire#how to have sex

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey so can we like stop with the "Zutara is for the girls and Kataang is for the boys" thing. It's silly and it's breakdancing just on the edge of gender essentialism.

The assumption that there is something inherent to Zutara that appeals predominantly to women and Kataang that appeals predominantly to men is dishonest because every ship can have appeal to all genders.

The discussion of the "female gaze" in Zutara and the "male gaze" in Kataang is also redundant. I enjoy dissecting the concept of "the gaze", however it is important to note that the "female gaze" doesn't have a set definition or grouping of conventions it adheres to. Lisa French, Dean of RMIT University’s School of Media and Communication says:

“The female gaze is not homogeneous, singular or monolithic, and it will necessarily take many forms... The aesthetic approaches, experiences and films of women directors are as diverse as their individual life situations and the cultures in which they live. The "female' gaze” is not intended here'to denote a singular concept. There' are many gazes."

Now excuse me as I put on my pretentious humanistics student hat.

Kataang's appeal to women and the female gaze

Before I start, I want to note that the female gaze is still a developing concept

There are very few female film directors and writers, and most of them are white. The wants and desires of women of colour, the demographic Katara falls into, are still wildly underepresented. Additionally, the concept of the female gaze had many facets, due to it being more focused on emotional connections rather than physical appearance as the male gaze usually is. Which means that multiple male archetypes fall into the category of "for the female gaze".

The "female gaze" can be best described as a response to the "male gaze", which was first introduced by Laura Mulvey in her paper: "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" , however the term "male gaze" itself was not used in the paper.

Mulvey brought up the concept of the female character and form as the passive, objectified subject to the active voyeuristic male gaze, which the audience is encouraged to identify, usually through the male character.

To quote her:

"In a world ordered by sexual imbalance', pleasure' in looking has been split between active'/male' and passive/female'. The determining male gaze' projects its fantasy onto the female' figure', which is styled accordingly."

Mulvey also brings up the concept of scopopfillia (the term being introduced by Freud), the concept of deriving sexual gratification from both looking and being looked at. This concept has strong overtones of voyeurism, exhibitionism and narcissism, placing forth the idea that these overtones are what keeps the male viewer invested. That he is able to project onto the male character, therefore being also able to possess the passive female love interest.

However, it's important to note that Mulvey's essay is very much a product of its times, focused on the white, heterosexual and cisgender cinema of her time. She also drew a lot of inspiration from Freud's questionable work, including ye ole penis envy. Mulvey's paper was groundbreaking at the time, but we can't ignore how it reinforces the gender binary and of course doesn't touch on the way POC, particularly women of colour are represented in film.

In her paper, Mulvey fails to consider anyone who isn't a white, cis, heterosexual man or woman. With how underrepresented voices of minorities already are both in media and everyday life, this is something that we need to remember and strive to correct.

Additionally Mulvey often falls into gender essentialism, which I previously mentioned at the beginning of this post. Funny how that keeps coming up

"Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" started a very interesting and important conversation, and I will still be drawing from certain parts of it, however huge swathes of this text have already become near archaic, as our culture and relationship with media evolves at an incredible pace.

And as filmaking evolves, so does our definition of the male and female gaze. So let's see what contemporary filmakers say of it.

In 2016, in her speech during the Toronto International Film Festival , producer of the TV series Transparent, Jill Soloway says:

“Numero uno, I think the Female Gaze is a way of “feeling seeing”. It could be thought of as a subjective camera that attempts to get inside the protagonist, especially when the protagonist is not a Chismale. It uses the frame to share and evoke a feeling of being in feeling, rather than seeing – the characters. I take the camera and I say, hey, audience, I’m not just showing you this thing, I want you to really feel with me.

[Chismale is Soloway's nickname for cis males btw]

So the term "female gaze" is a bit of a misnomer, since it aims to focus on capturing the feelings of characters of all genders. It's becoming more of a new way of telling stories in film, rather than a way to cater to what white, cisgender, heterosexual women might find attractive in a man.

Now, Aang is the decided protagonist of the show, however, Atla having somewhat of an ensemble cast leads to the perspective shifting between different characters.

In the first episode of atla, we very much see Katara's perspective of Aang. She sees him trapped in the iceberg, and we immediately see her altruism and headstrong nature. After she frees Aang, we are very much first subjected to Katara's first impressions of him, as we are introduced to his character. We only see a sliver of Aang's perspective of her, Katara being the first thing he sees upon waking up.

We see that she is intrigued and curious of him, and very excited about his presence. She is endeared and amused by his antics. She is rediscovering her childish side with his help. She is confiding in him about her own trauma surrounding the Fire Nation's genocide of the Southern Waterbenders. She is willing to go against her family and tribe ans leave them behind to go to the Northern Water Tribe with Aang. We also see her determination to save him when he is captured.

As the show moves on and the plot kicks into gear, we do shift more into Aang's perspective. We see his physical attraction to her, and while we don't see Katara's attraction quite as blatantly, there are hints of her interest in his appearance.

This is where we get deeper into the concept of Aang and Katara's mutual interest and attraction for one another. While her perspective is more subtle than most would like, Katara is not purely an object of Aang's desire, no more than he is purely an object of her desire.

When analysing this aspect of Katara and Aang's relationship, I couldn't help but be reminded of how Célene Sciamma's Portrait of a lady on fire (in my personal opinion, one of the best studies of the female gaze ever created) builds up its romance, and how it places a strong emphasis on the mutuality of the female gaze.

Portrait of a lady on fire's cinematography is very important to the film. We see the world through the perspective of our protagonist, a painter named Marianne. We also see her love interest, Héloïse, the woman whom she is hired to paint a portrait of, through Marianne's lense.

We see Marianne analyse Héloïse's appearance, her beauty. We look purely through Marianne's eyes at Héloïse for a good part of the movie, but then, something unexpected happens. Héloïse looks back. At Marianne, therefore, in some way, also at the audience. While Marianne was studying Héloïse, Héloïse was studying Marianne.

We never shift into Héloïse's perspective, but we see and understand that she is looking back at us. Not only through her words, when she for example comments on Marianne's mannerisms or behaviours, but also hugely through cinematography and acting of the two amazing leads. (Noémie Merlant as Marianne and Adèle Haenel as Héloïse. They truly went above and beyond with their performances.)

This is a huge aspect of the female gaze's implementation in the film. The camera focuses on facial expressions, eyes and body language, seeking to convey the characters' emotions and feelings. There's a focus on intense, longing and reciprocated eye contact (I have dubbed this the Female Gays Gaze.). The characters stand, sit or lay facing each other, and the camera rarely frames one of them as taller than the other, which would cause a sense of power imbalance.

The best way to describe this method of flimaking is wanting the audience to see the characters, rather than to simply look at them. Sciamma wants us to empathise, wants us to feel what they are feeling, rather than view them from a distance. They are to be people, characters, rather than objects.

Avatar, of course, doesn't display the stunning and thoughtful cinematography of Portrait of a Lady on Fire, and Katara and Aang's relationship, while incredibly important, is only a part of the story rather than the focus of it.

However, the 'Kataang moments' we are privy to often follow a similar convention to the ones between Marianne and Héloïse that I mentioned prior.

Theres a lot of shots of Katara and Aang facing each other, close ups on their faces, particularly eyes, as they gaze at one another.

Katara and Aang are often posited as on equal grounds, the camera not framing either of them as much taller and therefore more powerful or important than the other. Aang is actually physically shorter than Katara, which flies in the face in usual conventions of the male fantasy. (I will get to Aang under the male gaze later in this essay)

And even in scenes when Aang is physically shown as above Katara, particularly when he's in the Avatar state, Katara is the one to pull him down, maintaining their relationships as equals.

Despite most of the show being portrayed through Aang's eyes, Katara is not a passive object for his gaze, and therefore our gaze, to rest upon. Katara is expressive, and animated. As an audience, we are made aware that Katara has her own perspective. We are invited to take part in it and try to understand it.

Not unlike to Portrait of a Lady on Fire, there is a lot of focus placed on mannerisms and body language, an obvious example being Katara often playing with her hair around Aang, telegraphing a shy or flustered state. We also see her express jealousy over Aang, her face becoming sour, brows furrowed. On one occasion she even blew a raspberry, very clearly showing us, the audience, her displeasure with the idea of Aang getting attention from other girls.

Once again, this proves that Katara is not a passive participant in her own relationship, we are very clealry shown her perspective of Aang. Most of the scenes that hint at her and Aang's focus on their shared emotions, rather than, for example, Katara's beauty.

Even when a scene does highlight her physical appearance, it is not devoid of her own thoughts and emotions. The best example of this being the scene before the party in Ba Sing Se where we see Katara's looking snazzy in her outfit. Aang compliments her and Katara doesn't react passively, we see the unabashed joy light up her face, we can tell what she thinks of Aang's comment.

In fact, the first moment between Katara and Aang sets this tone of mutual gaze almost perfectly. Aang opens his eyes, and looks at Katara. Katara looks back.

There is, once again, huge focus on their eyes in this scene, the movement of Aang's eyelids right before they open draws out attention to that part of his face. When the camera shows us Katara, is zooms in onto her expression as it changes, her blinking also drawing attention to her wide and expressive eyes.

This will not be the first time emphasis is placed on Katara and Aang's mutual gaze during a pivotal moment in the show. Two examples off the top of my head would be the Ends of B2 and B3 respevtively. When Katara brings Aang back to life, paralleling the first time they laid eyes on one another. And at the end of the show, where their gaze has a different meaning behind it.

We see Katara's emotions and her intent telegraphed clearly in these instances.

In Book 1, we see her worry for this strange bald boy who fell out of an iceberg, which melts away to relief and a hint of curiosity once she ascertains that he isn't dead.

In B2 we once again see worry, but this time it's more frantic. Her relationship with Aang is much dearer to her heart now, and he is in much worse shape. When we see the relief on her face this time, it manifests in a broad smile, rather than a small grin. We can clearly grasp that her feelings for Aang have evolved.

In B3, we step away from the rule because Aang isn't on the verge of death or unconsciousness for the first time. It is also the first time in a situation like this that Aang isn't seeing Katara from below, but they are on equal footing. I attribute this to symbolising change of pace for their relationship.

The biggest obstacle in the development of Katara and Aang's romance was the war, which endangered both their lives. Due to this, there was a hesitance to start their relationship. In previous scenes that focused this much on Aang and Katara's mutual gaze, Aang was always in a near dead, or at least 'dead adjacent' position. This is is a very harsh reminder that he may very well die in the war, and the reason Katara, who has already endured great loss, is hesitant to allow her love for him to be made... corporeal.

However, now Aang is standing, portraying that the possibily of Katara losing him has been reduced greatly with the coming of peace, the greatest obstacle has been removed, and Katara is the one to initiate this kiss.

Concurrently, Katara's expression here does not portray worry or relief at all, because she has no need to be worried or relieved. No, Katara is blushing, looking directly at Aang with an expression that can be described as a knowing smile. I'd argue that this description is accurate, because Katara knows that she is about to finally kiss the boy she loves.

Ultimately, Katara is the one who initiates the kiss that actually begins her and Aang's romantic relationship.

Kataang's appeal to women is reflected in how Katara is almost always the one to initiate physical affection with Aang. With only 3 exceptions, one of which, the Ember Island kiss being immediately shown by the narrative as wrong, and another being a daydream due to Aang's sleep deptivation. The first moment of outwardly romantic affection between Aang and Katara is her kissing his cheek. And their last kiss in the show is also initiated by Katara.

I won't falsely state that Kataang is the perfect representation of the female gaze. Not only because the storyline has its imperfections, as every piece of media has. But also because I simply belive that the concept of the female gaze is too varied and nebulous to be fully expressed. With this essay, I simply wanted to prove that Kataang is most certainly not the embodiment of catering to the male gaze either. In fact it is quite far from that.

The aspects of Kataang that fall more towards embodying the female gaze don't just appeal to women. There's a reason a lot of vocal Kataang shippers you find are queer. The mutual emotional connection between Katara and Aang is something we don't have to identify with, but something we are still able to emphasise with. It's a profound mutual connection that we watch unfold from both perspectives that sort of tracends more physical, gendered aspects of many onscreen romances. You just need to see instead of simply look.

✨️Bonus round✨️

Aang under the gaze

This started off as a simple part of the previous essay, however I decided I wanted to give it it's own focus, due to the whole discourse around Aang being a wish-fullfilling self insert for Bryke or for men in genral. I always found this baffling considering how utterly... unappealing Aang is to the male gaze.

It may surprise some of you that men are also subjected to the male gaze. Now sadly, this has nothing to do with the male gaze of the male gays. No, when male characters, usually the male protagonist, are created to cater to the male gaze, they aren't portrayed as sexually desirable passive objects, but they embody the active/masculine aide of the binary Laura Mulvey spoke of in the quote I shared at the beginning of this essay.

The protagonist under the male gaze is not the object of desire but rather a character men and boys would desire to be.

They're usually the pinnacle of traditional, stereotypical masculinity.

Appearance wise: muscular but too broad, chiseled facial features, smouldering eyes, depending on the genre wearing something classy or some manner of armour.

Personalitywise they may vary from the cool, suave James Bond type, or a more hotblooded forceful "Alpha male" type. However these are minor differences in the grand scheme of things. The basis is that this protagonist embodies some manner of idealised man. He's strong, decisive, domineering, in control, intimidating... you get the gist. Watch nearly any action movie. There's also a strong focus placed on having sway or power over others. Often men for the male gaze are presented as wealthy, having power and status. Studies (that were proved to be flawed in the way the data was gathered, I believe) say that womem value resources in potential male partners, so it's not surprising that the ideal man has something many believe would attract "mates". [Ew I hated saying that].

Alright, now let's see how Aang holds up to these standards.

Well... um...

Aang does have power, he is the Avatar. However, he is often actually ignored, blown off and otherwise dismissed, either due to his age or his personality and ideals being seen as unrealistic and foolish. Additionally, Aang, as a member of a culture lost a century ago, is also often posited as an outsider, singled out as weak, his beliefs touted as the reason his people died out and.

Physically, Aang doesn't look like the male protagonist archetype, either. He isn't your average late teens to brushing up against middle aged. Aang is very much a child and this is reflected in his soft round features, large eyes and short, less built body. This is not a build most men would aspire to. Now, he still has incredible physical prowess, due to his bending. But I'm not sure how many men are desperate to achieve the "pacifist 12 year old" build to attract women.

Hailing from a nation that had quite an egalitarian system, Aang wouldn't have conventional ideas surrounding leadership, even if he does step up into it later. He also has little in the way of possessions, by choice.

As for Aang's personality, well...

I mean I wouldn't exactly call him your average James Bond or superhero. Aang is mainly characterised through his kindness, empathy, cheerful nature and occasional childishness (which slowly is drained as the trauma intesifies. yay.)

Aang is very unwilling to initiate violence, which sets him aside from many other male protagonists of his era, who were champing at the bit to kick some ass. He values nature, art, dance and fun. He's in tune with his emotions. He tries to desecalate situations before he starts a fight.

Some would say many of Aang's qualities could be classified as feminine. While the other main male characters, Zuko and Sokka try to embody their respective concepts of the ideal man (tied to their fathers), Aang seems content with how he presents and acts. He feels no need to perform masculinity as many men do, choosing to be true to his emotions and feelings.

These "feminine" qualities often attract ridicule from other within the show. He is emasculated or infantiliased as a form of mockery multiple times, the most notable examples being the Ember Island play and Ozai tauntingly referring to him as a "little boy". Hell, even certain Aang haters have participated in this, for example saying that he looks like a bald lesbian.

I'd even argue that, in his relationships with other characters, Aang often represents the passive/feminine. Especially towards Zuko, Aang takes on an almost objectified role of a trophy that can be used to purchase Ozai's love. [Zuko's dehumanisation of others needs to be discussed later, but it isn't surprising with how he was raised and a huge part of his arc is steerring away from that way of thinking.]

Aang and Zuko almost embody certain streotypes about relationships, the forceful, more masculine being a literal pursuer, and the gentler, more feminine being pusued.

We often see Aang framed from Zuko's perspective, creating something akin to the mutual gaze of Katara and Aang, hinting at the potential of Zuko and Aang becoming friends, a concept that is then voiced explicitly in The Blue Spirit.

However, unlike Katara, Zuko is unable to empathise with Aang at first, still seeing Aang as more of an object than a person. We have here an interesting imbalance of Aang seeing Zuko but Zuko meerly looking at Aang.

There is a certain aspect of queer metaphor to Zuko's pursuit of Aang, but I fear I've gotten off topic.

Wrapping this long essay up, I want to reiterate that I'm not saying that Zutara isn't popular with women. Most Zutara shippers I've encountered are women. And most Kataang shippers I've encountered are... also women. Because fandom spaces are occupied predominantly by women.

I'm not exactly making a moral judgement on any shippers either, or to point at Kataang and go: "oh, look girls can like this too. Stop shipping Zutara and come ship this instead."

I want to point out that the juxtaposition of Zutara and Kataang as respectively appealing to the feminine and masculine, is a flawed endeavour because neither ship does this fully.

The concept of Kataang being a purely male fantasy is also flawed due to the points I've outlied in this post.

Are there going to be male Kataang shippers who self insert onto Aang and use it for wish fulfilment? Probably. Are there going to be male Zutara shippers who do the same? Also probably.

In the end, our interpretation of media, particularly visual mediums like film are heavily influenced by our own biases, interests, beliefs andmost importantly our... well, our gaze. The creators can try to steer us with meaningful shots and voiced thought, directing actors or animating a scene to be a certain way, but ultimately we all inevitably draw our own conclusions.

A fan of Zutara can argue that Kataang is the epitome of catering to the male gaze, while Zutara is the answer to women everywhere's wishes.

While I can just as easily argue the exact opposite.

It really is just a matter of interpretation. What is really interesting, is what our gaze says about us. What we can see of ourselves when the subject gazes back at us.

I may want to analyse how Zutara caters to the male gaze in some instances, if those of you who manage to slog through this essay enjoy the subject matter.

#ok getting off my soapbox#i forgot how much i love to write these long sprawling essays...#kataang#pro kataang#aang#pro aang#aanglove#aang defense squad#pro katara#katara defense squad#kataang love#zuko#avatar#atla#avatar: the last airbender#the last airbender#avatar the last airbender#aang the last airbender#anti zutara

432 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just saw Barbie at my local cinema and holy shit was it an experience.

People from all walks of life, families with their daughters, young lovers, seniors all came to see Barbie and all appropriately dressed in hot pink.

Especially fitting considering the film’s humanistic message. You don’t have to be all of the things that are expected of you, what you are already is good enough, so just enjoy yourself! Such a universal message that I think only something like Barbie could pull off.

But also this film is on Zoolander levels of humour, could not breathe during the Ken-off.

Ken out of Ken.

#barbie#barbie movie#gecko boy#i feel like this’ll be an era defining film#like barbie will be to gen z what clerks and dazed and confused is to gen x#also this film deconstructs gender roles very very well#more humanist movies please#barbenheimer

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

In any case, in 2024 it is possible to eat delicious food you didn’t make yourself, watch movies that have recently come out in the cinema, buy all manner of clothes, tools and fripperies, do the food shopping, speak to friends and family and earn a wage – all without ever leaving the house. Why should we, then? What’s in it for us? There are a number of ways to answer those questions, not all of which will appeal to everyone, but it is worth setting them out. Living a real, physical life outside the home is good because humans need friction. Convenience is alluring but it is dangerous, because getting used to it means forgetting that being alive isn’t meant to always be easy. We should run our errands in person and queue at the Post Office and eat in restaurants because it is good to remember that sometimes we have to wait around, or go to several shops because the first one didn’t have what we needed. Resilience is one of the most important traits a person can and should develop, and it works like a muscle. Glide effortlessly through life and, when something bad does happen, because it always will, you won’t know how to react. On a similar note, forcing ourselves to go out even when we’d rather stay on the couch can remind us that good, surprising things usually tend to take place when we least expect them. You may bump into an old acquaintance while out buying a pair of shoes or a carton of milk, or see someone you’d forgotten even existed. You may get to pet a very cute dog, or have a nice laugh with an old lady who struck up a conversation with you, or help someone else who got knocked off their bike and feel good about it, or, or, or – the possibilities are endless. That’s the entire point. The outside is where the unknowable can and will take place, and that’s what makes it so wonderful. A life without any serendipity is hardly worth living and yes, chance is precious enough that it is worth its cost.

Marie Le Conte, 'The Introverts are Winning' (25 July 2024) The New Humanist

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nights of Cabiria (1957) Directed by Federico Fellini

#nights of cabiria#federico fellini#1957#italian cinema#neorealism#giulietta masina#tragic heroine#cinema of emotions#hope and despair#existential journey#visual storytelling#soulful filmmaking#rome at night#loneliness and resilience#spiritual longing#cinema of dreams#humanist cinema#poetic storytelling#classic world cinema#black and white cinema#golden age of italian film#modern classic#1950s movies#50s#filn#movie

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

84 years ago, Charlie Chaplin's "The Great Dictator" (1940) was released.

The film "The Great Dictator" is an extraordinary satirical gem. Charlie Chaplin directed, wrote, produced and starred in this cinematic gem. "The Great Dictator" is an iconic piece of cinema history, carrying a deep message of social justice. Through comedy, Charlie Chaplin skillfully expresses his deep concern about the political climate of his time. The final speech, which is the key to this film, is a humanistic lecture for humanity, with a message full of hope, unfortunately very relevant today. The unique ability to seamlessly blend humor and pathos truly sets this film apart, transcending the conventions of typical commercial films.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝓗𝓲 𝓪𝓷𝓭 𝔀𝓮𝓵𝓬𝓸𝓶𝓮 𝓽𝓸 𝓶𝔂 𝓰𝓲𝓻𝓵𝓫𝓵𝓸𝓰

-"but the innocence... Because it adheres to me with an important part of my temper, dismantles me and makes me fall in love"-

-Mercè Rodoreda

~•𝑨𝒃𝒐𝒖𝒕 𝒎𝒚 𝒃𝒍𝒐𝒈:

There's not really much to say here, as you might have seen, I post about things that make me happy, whereas it is a picture of myself, the book that I'm reading or my favourite songs and singers. Therefore you will find some variety in my posts.

Here's a brief summary of my main based-interests posts:

🎀.Classic Catalan and Spanish literature and authors, specifically those from the 20th century.

🩰.Moodboards and collages inspired in various aesthetics

🪷.Some weekly - monthly photo blogs about my life, outfits, trips, etc.

🍂. Thoughts and complaints about everything

🌸.The seventh art (cinema) and my current favourite TV series, including reviews and moodboards

~•𝑨𝒃𝒐𝒖𝒕 𝒎𝒆:

I would love to be seen as mysterious and esoteric but I know damn well I can't stfu.

I'm a chemistry student, but I'm looking to do a kind of "secondary" degree in a more humanistic aspect such as philosophy or languages and literature.

My hobbies are: Writing and reading, and my favourite authors are: Catalan novelist 𝓜𝓮𝓻𝓬è 𝓡𝓸𝓭𝓸𝓻𝓮𝓭𝓪 and spanish poet 𝑭𝒆𝒅𝒆𝒓𝒊𝒄𝒐 𝑮𝒂𝒓𝒄í𝒂 𝑳𝒐𝒓𝒄𝒂 . I also really enjoy watching movies, my current favourites being: 𝓣𝓱𝓮 𝓼𝓲𝓵𝓮𝓷𝓬𝓮 𝓸𝓯 𝓽𝓱𝓮 𝓵𝓪𝓶𝓫𝓼, and 𝓣𝓱𝓮 𝓿𝓲𝓻𝓰𝓲𝓷 𝓼𝓾𝓲𝓬𝓲𝓭𝓮𝓼 by Sofia Coppola. I also love the works of Keanu Reeves and Kristen Dunst.

I enjoy lots of things like sunsets, music (don't really have a favourite artist), nature, especially the beach, romanticism and hedonism, and vintage stuff.

On the other hand, I hate fascist pigs, people who don't respect each other's languages, homophobes and racists, the patriarchy, the oligarchy, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, and maths.

The end

#female hysteria#girl interupted syndrome#coquette#lana del rey#just girly things#just girly thoughts#im just a girl#blogging#girlblogging#femcel#welcome to my blog#tumblr girls#girly stuff#spotify#female manipulator#female rage#girl interrupted#girlhood#hell is a teenage girl#girly blog#girl blogger

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SUBLIME CINEMA #653 - HANA-BI

Humanist take on a gangster picture that nabbed Beat Takeshi a Golden Lion in Venice and finally garnered him respect as an artist behind the camera as well as in front of it.

#cinema#film#movie#movies#filmmaking#Japan#films of Japan#Japanese director#Japanese cinema#cinema of japan#beat takeshi#takeshi kitano#ren osugi#Susumu Terajima#Kayoko Kishimoto#Hakuryû#filmmaker#great film#hana-bi#hana bi#fireworks#films#director#cinephile#entertainment#gangster#yakuza

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

I. The Politics of Film Theory: From Humanism to Cultural Studies

Prior to its emergence as a distinct academic discipline in the 1970s, film studies could be roughly divided into two distinct but closely-related camps: humanism, which analyzed cinema in terms of its promotion of, or opposition to, classical Enlightenment values (e.g., freedom and progress), and various schools of formalism, which focused on the formal, technical, and structural elements of cinema in general as well as of individual films.[1] As Dana Polan notes, humanist critics frequently vacillated between skepticism toward cinema and profound, even hyperbolic adulation of it (Polan, 1985: 159). To some, film represented “the death of culture for the benefit of a corrupt and debasing mass civilization” (ibid.).[2] To others, film did not kill culture so much as democratize it by destabilizing the privileged, elite status of art (cf., Cavell, 1981). Ultimately, however, “the pro and con positions merge in their common ground of originary presuppositions: they understand art as redemption, transport, utopian offer” (Polan, 1985: 159).

Like the pro-film humanists, formalist critics emphasized the artistic depth and integrity of cinema as genre. (This is especially true of auteur theory, according to which films are expressions of the unique ideas, thoughts, and emotions of their directors; Staples, 1966–67: 1–7.) Unlike humanism, however, formalism was centrally concerned with analyzing the vehicles or mechanisms by which film, as opposed to other artistic genres, generates content. This concern gave rise, in turn, to various evaluative and interpretive theories which privileged the formal elements of film (e.g., cinematography, editing, etc) over and above its narrative or thematic elements (cf., Arnheim, 1997, 1989; Bazin, 1996, 1967; Eiseinstein, 1969; Kracauer, 1997; Mitry, 1997).

In contrast to the optimistic humanists and the apolitical formalists, the Marxist critics of the Frankfurt School analyzed cinema chiefly as a socio-political institution — specifically, as a component of the repressive and mendacious “culture industry.” According to Horkheimer and Adorno, for example, films are no different from automobiles or bombs; they are commodities that are produced in order to be consumed (Horkheimer & Adorno, 1993: 120–67). “The technology of the culture industry,” they write, “[is] no more than the achievement of standardization and mass production, sacrificing whatever involved a distinction between the logic of work and that of the social system” (ibid., 121). Prior to the evolution of this industry, culture operated as a locus of dissent, a buffer between runaway materialism on the one hand and primitive fanaticism on the other. In the wake of its thoroughgoing commodification, culture becomes a mass culture whose movies, television, and newspapers subordinate everyone and everything to the interests of bourgeois capitalism. Mass culture, in turn, replaces the system of labour itself as the principle vehicle of modern alienation and totalization.

By expanding the Marxist-Leninist analysis of capitalism to cover the entire social space, Horkheimer and Adorno severely undermine the possibility of meaningful resistance to it. On their view, the logic of Enlightenment reaches its apex precisely at the moment when everything — including resistance to Enlightenment — becomes yet another spectacle in the parade of culture (ibid., 240–1). Whatever forms of resistance cannot be appropriated are marginalized, relegated to the “lunatic fringe.” The culture industry, meanwhile, produces a constant flow of pleasures intended to inure the masses against any lingering sentiments of dissent or resistance (ibid., 144). The ultimate result, as Todd May notes, is that “positive intervention [is] impossible; all resistance [is] capable either of recuperation within the parameters of capitalism or marginalization [...] there is no outside capitalism, or at least no effective outside” (1994: 26). Absent any program for organized, mass resistance, the only outlet left for the revolutionary subject is art: the creation of quiet, solitary refusals and small, fleeting spaces of individual freedom.[3]

The dominance of humanist and formalist approaches to film was overturned not by Frankfurt School Marxism but by the rise of French structuralist theory in the 1960s and its subsequent infiltration of the humanities both in North America and on the Continent. As Dudley Andrew notes, the various schools of structuralism[4] did not seek to analyze films in terms of formal aesthetic criteria “but rather [...] to ‘read’ them as symptoms of hidden structures” (Andrew, 2000: 343; cf., Jay, 1993: 456–91). By the mid-1970s, he continues, “the most ambitious students were intent on digging beneath the commonplaces of textbooks and ‘theorizing’ the conscious machinations of producers of images and the unconscious ideology of spectators” (ibid.). The result, not surprisingly, was a flood of highly influential books and essays which collectively shaped the direction of film theory over the next two decades.[5]

One of the most important structuralists was, of course, Jacques Derrida. On his view, we do well to recall, a word (or, more generally, a sign) never corresponds to a presence and so is always “playing” off other words or signs (1978: 289; 1976: 50). And because all signs are necessarily trapped within this state or process of play (which Derrida terms “differance”), language as a whole cannot have a fixed, static, determinate — in a word, transcendent meaning; rather, differance “extends the domain and the play of signification infinitely” (ibid, 280). Furthermore, if it is impossible for presence to have meaning apart from language, and if (linguistic) meaning is always in a state of play, it follows that presence itself will be indeterminate — which is, of course, precisely what it cannot be (Derrida, 1981: 119–20). Without an “absolute matrical form of being,” meaning becomes dislodged, fragmented, groundless, and elusive. The famous consequence, of course, is that “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” (“There is no outside-text”) (Derrida, 1976: 158). Everything is a text subject to the ambiguity and indeterminacy of language; whatever noumenal existence underlies language is unreadable — hence, unknowable — to us.

In contrast to Marxist, psychoanalytic, and feminist theorists, who generally shared the Frankfurt School’s suspicion towards cinema and the film industry, Derridean critics argued that cinematic “texts” do not contain meanings or structures which can be unequivocally “interpreted” or otherwise determined (cf., Brunette & Wills, 1989). Rather, the content of a film is always and already “deconstructing” — that is, undermining its own internal logic through the play of semiotic differences. As a result, films are “liberated” by their own indeterminacy from the hermeneutics of traditional film criticism, which “repress” their own object precisely by attempting to fix or constitute it (Brunette & Wills, 1989: 34). Spectators, in turn, are free to assign multiple meanings to a given film, none of which can be regarded as the “true” or “authentic” meaning.

This latter ramification proved enormously influential on the discipline of cultural studies, the modus operandi of which was “to discover and interpret the ways disparate disciplinary subjects talk back: how consumers deform and transform the products they use to construct their lives; how ‘natives’ rewrite and trouble the ethnographies of (and to) which they are subject...” (Bérubé, 1994: 138; see also Gans, 1974, 1985: 17–37; Grossberg, 1992; Levine, 1988; Brantlinger, 1990; Aronowitz, 1993; During, 1993; Fiske, 1992; McRobbie, 1993). As Thomas Frank observes,

The signature scholarly gesture of the nineties was not some warmed over aestheticism, but a populist celebration of the power and ‘agency’ of audiences and fans, of their ability to evade the grasp of the makers of mass culture, and of their talent for transforming just about any bit of cultural detritus into an implement of rebellion (Frank, 2000: 282).

Such a gesture is made possible, again, by Derrida’s theory of deconstruction: the absence of determinate meaning and, by extension, intentionality in cultural texts enables consumers to appropriate and assign meaning them for and by themselves. As a result, any theory which assumes that consumers are “necessarily silent, passive, political and cultural dupes” who are tricked or manipulated by the culture industry and other apparatuses of repressive power is rejected as “elitist” (Grossberg, 1992: 64).

A fitting example of the cultural studies approach to cinema is found in Anne Friedberg’s essay “Cinema and the Postmodern Condition,” which argues that film, coupled with the apparatus of the shopping mall, represents a postmodern extension of modern flaneurie (Friedberg, 1997: 59–86). Like Horkheimer and Adorno, Friedberg is not interested in cinema as an art form so much as a commodity or as an apparatus of consumption/desire production. At the same time, however, Friedberg does not regard cinema as principally a vehicle of “mass deception” designed by the culture industry to manipulate the masses and inure them to domination. Although she recognizes the extent to which the transgressive and liberatory “mobilized gaze” of the flaneur is captured and rendered abstract/virtual by the cinematic apparatus of the culture industry (ibid., 67), she nonetheless valorizes this “virtually mobile” mode of spectatorship insofar as it allows postmodern viewers to “try on” identities (just as shoppers “try on” outfits) without any essential commitment (ibid., 69–72).

This kind of approach to analyzing film, though ostensibly “radical” in its political implications, is in fact anything but. As I shall argue in the next section, cultural studies — no less than critical theory — rests on certain presuppositions which have been severely challenged by various theorists. Michel Foucault, in particular, has demonstrated the extent to which we can move beyond linguistic indeterminacy by providing archeological and genealogical analyses of the formation of meaning-producing structures. Such structures, he argues, do not emerge in a vacuum but are produced by historically-situated relations of power. Moreover, power produces the very subjects who alternately affect and are affected by these structures, a notion which undermines the concept of producer/consumer “agency” upon which much of critical theory and cultural studies relies. Though power relations have the potential to be liberating rather than oppressive, such a consequence is not brought about by consumer agency so much as by other power relations which, following Gilles Deleuze, elude and “deterritorialize” oppressive capture mechanisms. As I shall argue, the contemporary cinematic apparatus is without a doubt a form of the latter, but this does not mean that cinema as such is incapable of escaping along liberatory lines of flight.

#cinema#film theory#movies#anarchist film theory#culture industry#culture#deconstruction#humanism#truth#the politics of cinema#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues#anarchy works#anarchist library#survival#freedom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LEVON FLJYAN 1983, Gyumri Boy + Girl, 2012 paper, graphite, pencil

+ the text that was accompanying the exhibition, because I find it interesting

During the European Renaissance in the 15th century, artists turned towards humanist ideas that made man into the primary subject of Western art. Reviving the philosophical tenets of Greco-Roman antiquity, the leading art schools and academies across Europe positioned the human figure as nature’s most sophisticated creation and hence, the very epitome of beauty and perfection. No longer circumscribed by religious moral codes, the naked form was transformed by artists such as Titian, Velasquez, Rembrandt and Rubens into an object of aesthetic admiration and a marker of artistic excellence. By the 17th century the Nude had evolved into an autonomous genre of fine art, becoming a key cultural signifier of Western modernity. Armenian artists adopted these concepts relatively late, after they gained access to Russian and European art schools in the first half of the 19th century. However, while many of these pioneers excelled at academic studies of the nude figure, few of them turned to the genre itself in their professional practice. For the 19th century Armenian public, representations of nakedness were still cloaked in strict cultural bias of decency and there was little demand for such images from Armenian artists. The fact that classicist aesthetics were defined primarily by European male artists (women were barred from studying the nude until the late 19th century) presented other challenges. Classicism created impossible standards of beauty based on racist conceptions of white man’s superiority and pseudo-scientific notions of physical perfection. Such prejudices let to the idolisation of European bodies as well as the exoticisation and denigration of other ethnicities in Western art. This situation hindered the expression of specifically local, Armenian sensibilities in regards to nudity in visual art well into 20th century. Though the rise of modernist art in the 1900s destabilised classical models of figurative representation, the Renaissance-inspired “flawless” nude has remained remarkably pervasive. Reappearing time and again in both European and Armenian art as a fantasy object of aesthetic admiration, the impossibly idealised body is still one of the most universally-recognized cultural constructions. Perpetuated by cinema, mass media, advertising and pornography, it continues to condition how we view ourselves and evaluate those around us.

#art#armenian#artistic nudity#this piece was a part of an exhibition about the nude figure in art from the art museum of armenia. from september 2023

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katharine Hepburn - The Greatest Female Star

Katharine Houghton Hepburn (born in Hartford, Connecticut on May 12, 1907) was an iconic American actress who holds the record for the most wins for an actor in Oscar history and is considered to be "The Greatest Female Star" of classic Hollywood.

Raised in Connecticut by wealthy, progressive parents of English and Scottish heritage, Hepburn began to act while at Bryn Mawr College, where she graduated with a degree in history and philosophy. Favorable reviews of her on Broadway got the attention of Hollywood, where director George Cukor pushed for her to sign a contract with RKO at 1932.

Her early films brought her fame, but this was followed by commercial failures. She masterminded her comeback, buying out her contract and acquiring rights to The Philadelphia Story, which she sold on the condition that she be the star. The film was a success and landed her a 3rd Oscar nomination in 1940.

She continued to have acclaimed films, including her last Oscar for On Golden Pond (1981). In the 1970s, she began appearing on TV alongside her film and stage roles. She made her final screen appearance at 87. After a period of inactivity and ill health, she died from cardiac arrest at 96 at the Hepburn family home in Fenwick, Connecticut.

Legacy:

Won four Academy Awards for Best Actress: Morning Glory (1933), Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967), The Lion in Winter (1968), On Golden Pond (1982) - and nominated for eight (1936, 1941, 1943, 1952, 1956, 1957, 1960, 1963), holding the record for the longest time span between first and last nominations, at 48 years

Won the 1975 Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Actress in a Special - Drama or Comedy and nominated for six (1974, 1979, 1986, 1993)

Nominated for 11 Golden Globe Awards (1952, 1956, 1959, 1962, 1967, 1968, 1981, 1992); two Tony Awards (1970, 1982); the 1994 Screen Actors Guild Award; and the 1988, 1992 Grammy Best Spoken Word Album

Received two BAFTA Best Actress awards (1969, 1983) and five nominations (1953, 1956, 1958)

Won the Volpi Cup for Best Actress at the 1934 Venice Film Festival; Best Actress at 1962 Cannes Film Festival; and the Special Prize of the Jury at 1984 Montréal World Film Festival

Won the 1940 New York Film Critics Circle Best Actress, the 1965 Mexican Cinema Journalists Best Foreign Actress, and the 1973 Kansas City Film Critics Circle Best Actress

Won three Golden Laurel Awards for Top Female Dramatic Performance in 1960, 1963, and 1970, and nominated as Top Female Star in 1970 and 1971

Received the David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Actress for Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967)

Won Golden Apple Awards for Female Star of the Year in 1975 and 1982; and Favorite Motion Picture Actress at the People's Choice Awards in 1976 and 1983, and nominated in 1975, 1977

Received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Screen Actors Guild in 1979

Purchased war bonds worth #30K to support the Hartford Red Cross in 1941 and donated $10K to Hartford Hospital in 1947

Selected by Harvard University as 1958 Hasty Pudding Woman of the Year

Featured in exhibits, such as The Career of an Actress: Katharine Hepburn at the MoMA in 1969, One Life: Kate, A Centennial Celebration at the National Portrait Gallery in 2007, Katharine Hepburn: In Her Own Files at the NYPL in 2009, and Katharine Hepburn: Dressed for Stage and Screen at Kent State University in 2010

Supported Planned Parenthood since 1981 with the Katharine Houghton Hepburn Fund and received the Margaret Sanger Award in 1983

Inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in 1979, the Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame in 1994, and the Online Film and Television Association Hall of Fame in 1999

Received the 1985 Humanist Arts Award from the American Humanist Association and the Lifetime Achievement Awards from the Council of Fashion Designers of America in 1985, the American Comedy Awards in 1985 and the Kennedy Center Honors in 1990

Released her 1991 autobiography, Me: Stories of My Life

Awarded an honorary doctorate by Columbia University in 1992

Has had a garden in her name since 1997 and an intersection, Katharine Hepburn Place, since 2003 in New York

Named the greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema in 1999 by the American Film Institute

Named in Ladies Home Journal's 1998 book 100 Most Important Women of the 20th century; Encyclopædia Britannica's 300 Women Who Changed the World in 2006; the 2007 book Women Who Changed The World; and Variety's 100 Icons of the Century in 2005

Ranked #68 in in Empire’s Top 100 Movie Stars in 1997; #2 in Entertainment Weekly’s 100 Greatest Movie Stars of All Time in 1998; #84 in VH1's "200 Greatest Pop Culture Icons of All Time" in 2003; #14 in Premiere's 50 Greatest Movie Stars of All Time in 2005 and #13 and #54 in 100 Greatest Performances of All Time in 2006 for The Lion in Winter (1968) and The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Featured in the 2002 play, Tea at Five, and a two-month retrospective by the British Film Institute in 2015

Has personal collections at The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences library, the New York Public Library, and the University of Hartford since 2003

Became the namesake of Bryn Mawr College's Katharine Houghton Hepburn Center, which manages the Hepburn Fellows Program, Hepburn Scholarships, and the Katharine Hepburn Medal, since 2006

Inspired the The Katharine Hepburn Cultural Arts Center, which opened in 2009 in Old Saybrook and runs the Katharine Hepburn Museum and the Spirit of Katharine Hepburn Award

Became the 16th star honored by US Postal Service's Legends of Hollywood stamp series in 2010

Honored as Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month for January 2004 and June 2023

Has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6294 Hollywood Blvd for motion picture

#Katharine Hepburn#The Greatest Female Star#The Great Kate#Silent Films#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Classic Hollywood#Film Classics#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#hollywood legend#movie stars#1900s#28 Hollywood Legends Born in the 1900s

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Montana Story (2021)

How can the ripple effects of trauma be explored in cinema? The obvious, clunky, boring answer is for characters to remind one another of important events in the past when they have their first conversation because it’s easier for the screenwriter to front-load information and context. But that’s not how human beings work. I don’t need to remind that one friend of a friend that they can kick rocks for things they’ve done to me before when I’m unable to avoid them at social gatherings, but that certainly colors my demeanor toward them with an icy palette. In Montana Story, Erin’s arrival at the family ranch is jarring and her mood jagged and terse. The father of her and her brother Cal is in a coma and under palliative care. The exact nature of her relationship to her father isn’t clear, but the fact that she cannot be in a room alone with his comatose body signals that something deeply wrong happened between them. Flashbacks can be another cinematic tool, allowing the viewer to glimpse key moments of the past, to compare and contrast with the events unfolding in the current timeline. How have things changed or remained the same, for good or ill? This film eschews that entirely, which is an interesting choice given its character in focus. While the core drama is between Erin and her father, the viewer’s entry point is Cal. We first learn of the brutality visited upon Erin by her father through the words of Cal, and in the way that events unfold his sense of guilt over not helping her in that moment and her forgiving him on some level or other becomes the focus of the film. A victim becomes the tool of redemption for another. A flashback to the scene of the domestic violence isn’t necessary; that would teeter on the edge of exploitative voyeurism, depending on the execution. And reflecting on the siblings’ relationship as children might not be useful either, rose-colored glasses donned in a film otherwise agnostic to the past: if the thesis is about acknowledging that things before have happened and that nothing can be done about it, that moving onward is the only option, gazing nostalgically backwards is counter-productive. But giving the verbal accounting of that pivotal night to one character or the other implicitly hands them power over the narrative and shapes the overall thrust. Cal is perfectly valid in his inner turmoil, and deserves resolution. But structuring the story in this way, making the victim’s suffering so operatic in a sense and then sidelining that same character within their own trajectory minimizes the pain in its own way, makes it a tool for Sundance-bait storytelling rather than one for organic, humanistic processing of trauma.

Anyway, here’s my dumb drinking game.

THE RULES

SIP

Someone says 'ranch'.

The father is mentioned.

Dramatic establishing shot of mountains.

BIG DRINK

Cell phone service issues (this film brought to you by Verizon)

The film cuts to black.

Mr T's "appointment" is brought up.

#drinking games#montana story#david siegel#scott mcgehee#haley lu richardson#owen teague#drama#western

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Cinema is the love of my life."

Have you ever experienced the rush of emotions, the thrill of storytelling, and the magic of visual artistry all rolled into one? If you resonate with this sentiment, you're in the right place! Welcome to Cinephile's Corner, a virtual haven dedicated to our undying love for the silver screen.

In this corner of the internet, we gather to celebrate the mesmerizing world of cinema—a universe that has captured our hearts and minds. From black and white classics to cutting-edge masterpieces, we embark on a journey through time, exploring the works of visionary filmmakers who have left an indelible mark on the art of storytelling.

As we venture forth, we encounter an array of cinematic geniuses, each with their unique style and narrative flair. One cannot speak of cinematic brilliance without mentioning the legendary Martin Scorsese, whose films have forever redefined American cinema. From "Taxi Driver" to "Goodfellas" and beyond, Scorsese's storytelling prowess is nothing short of awe-inspiring.

We delve deeper into the world of art cinema with Andrei Tarkovsky, the Russian auteur whose films are known for their profound philosophical themes and stunning visual poetry. Prepare to be entranced by the ethereal beauty of "Mirror" and the enigmatic journey of "Stalker."

Stanley Kubrick, a master of his craft, shall forever hold a place of reverence in our cinephilic hearts. His meticulous attention to detail and audacious storytelling gave us cinematic treasures like "2001: A Space Odyssey," "A Clockwork Orange," and "The Shining."

And how can we forget Akira Kurosawa, the Japanese maestro whose samurai epics and humanist tales continue to inspire filmmakers worldwide? "Seven Samurai," "Rashomon," and "Yojimbo" are just a few of the many gems he bestowed upon us.

Our love for cinema is not confined to the West; we also cherish the works of revered directors from different regions. In the Indian landscape, we find ourselves drawn to the films of Mahendran and Bharathiraja, who pioneered a new wave of Tamil cinema with their thought-provoking narratives.

Venturing southward to the lush landscapes of Kerala, we lose ourselves in the profound storytelling of Adoor Gopalakrishnan—a master of subtlety and social commentary in Malayalam cinema.

And of course, no homage to world cinema would be complete without paying respects to the maestro of Bengali cinema, Satyajit Ray. His iconic "Apu Trilogy" remains an unparalleled work of art that continues to resonate with cinephiles across the globe.

As we traverse this cinematic landscape, we'll also explore the groundbreaking works of Eric Rohmer and Godard, whose contributions to the French New Wave have redefined cinema's language.

At Cinephile's Corner, we invite you to immerse yourself in the enchanting world of cinema, where every frame is a brushstroke of emotion, every dialogue a symphony of words, and every performance a reflection of the human spirit.

Join us on this thrilling ride of cine-adventure, as we celebrate the past, present, and future of cinema. From passionate discussions and in-depth analyses to reviews and recommendations, this blog is a homage to the love that unites us all—our love for cinema.

So grab your popcorn, dim the lights, and let's embark on this cinematic odyssey together!

Lights, camera, action! Welcome to Cinephile's Corner!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

City Lights (1931) Directed by Charlie Chaplin

#city lights#charlie chaplin#1931#silent film#romantic comedy#tramp character#classic cinema#visual storytelling#slapstick comedy#pathos and humor#golden age hollywood#love and kindness#cinematic poetry#silent era masterpiece#timeless storytelling#humanist cinema#hollywood legend#emotional depth#comedy and drama#classic romance#iconic film moments#cinema history#early sound era#1930s movies

1 note

·

View note

Text

Victoria Nelson’s The Secret Life of Puppets, a beautiful study of the Neoplatonic, gnostic, or Hermetic “soul” of Western culture as temporarily repressed and demonized. Here Nelson gives us a brilliant study of the modern demonization of the soul as puppet, robot, or cyborg and the bracketing (really repressing) of the deeper questions of human consciousness within contemporary intellectual culture. In the process, she examines what we too will encounter below, that is, the imaginative exile of Spirit into the furthest reaches of “outer space,” from where, of course, it returns to haunt us as the Alien.

For Nelson, this demonization and subsequent alienation is born of an exaggerated and unbalanced scientism, a one-sided Aristotelianism that she sees us now moving beyond before a balancing Platonic resurgence. It is not about one or the other, though. It is about both. It is about balance. Western intellectual, spiritual, and cultural life, at their best and most creative anyway, work through a delicate balancing act between this Aristotelianism (read: rationalism) and this Platonism (read: mysticism).

The pendulum has been swinging right, toward Aristotle, for about three hundred years now. It has now reached its rationalist zenith and is beginning to swing back left, toward Plato. Which is not to say, at all, that Western culture will somehow become irrational and unscientific again, that we suddenly won’t need Aristotle or science any longer. This vast centuries-long process is ultimately about balance, about wisdom. It is also about making the unconscious conscious, about realizing and living our own secret life:

The new sensibility does not threaten a regression from rationality to superstition; rather, it allows for expansion beyond the one-sided worldview that scientism has provided us over the last three hundred years. We should never forget how utterly unsophisticated the tenets of eighteenth-century rationalism have left us, believers and unbelievers alike, in that complex arena we blithely dub “spiritual.” Even as we see all too clearly the kitsch of much New Age religiosity and fear the rigidity of rising fundamentalism, we remain alarmingly blind to our own unconscious tendencies in this same direction.

Our conventional secular bias whispers to us that the ideas we see naively articulated on the cinema screen (ideas as blasphemous to secular humanists as they are to the religious orthodox), if they are to be taken seriously at all, signal a backward slide into religious oppression and intolerance. What our perspective does not allow us to recognize is the positive and enduring dimension of such ideas when they are consciously articulated in our culture. We forget that Western culture is equally about Platonism and Aristotelianism, idealism and empiricism, gnosis and episteme, and that for most of this culture’s history one or the other has been conspicuously dominant—and dedicated to stamping the other out.

Such a Platonic balancing or mystical revival, of course, cannot enter the house of elite culture directly. Its kitsch clothes and tastes in movies are too easily rebuffed, demeaned, belittled, and shamed by the scientistic and pious doorkeepers. So it walks around the house and comes in the back door, through the imaginative products of popular culture and the inexorable mechanisms of market capitalism (if elite intellectuals and orthodox religious leaders don’t buy this stuff, almost everyone else does, literally). In our own time, Nelson argues, this back-door gnosis arises out of the “sub-Zeitgeist” of science fiction, superhero comic books, fantasy, and especially film.

-- Jeffrey J. Kripal, Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred

3 notes

·

View notes