#huizong

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Autumn Colors among Streams and Mountains - Huizong (1082-1135) [China, Song dynasty (960-1279)]

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite the eleventh-century economic boom, the Song dynasty's endless war against the Khitans on the northern frontier was a constant financial drain and the emperors kept looking for new ways to pay their bills. Consequently, when in 1115 the "Wild Jurchens" of Manchuria offered to help fight the Khitans, Emperor Huizong eagerly accepted (Figure 8.2).

Only in 1141 did a frontier settle down between the Jurchens, now ruling northern China, and a much-reduced Song state based at Hangzhou.*

*Historians normal divide the Song period into the Northern Song phase (960-1127), when the dynasty ruled most of China from Kaifeng, and a Southern Song phase (1127-1279), when it ruled only southern China from Hangzhou.

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quotes#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#11th century#economic boom#song dynasty#war#khitan#financial drain#pay the bills#12th century#jurchen#manchuria#huizong#helping hand#southern china#hangzhou

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

routinely I think about what a failflop Huizong of Song was and then I have to think about how he popularized some of my FAVORITE song dynasty art and culture related stuff and I just--

*angrily chews on this chocolate bar*

#many ancient chinese emperors were kind of loser men#but NONE make me as mad as Huizong of Song#I can't explain it#I'll be puttering along looking at cool art stuff#and I go “huh! I wonder who's responsible for us having--”#it's huizong of song roughly 90% of the time#anyway#complaints with tav

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

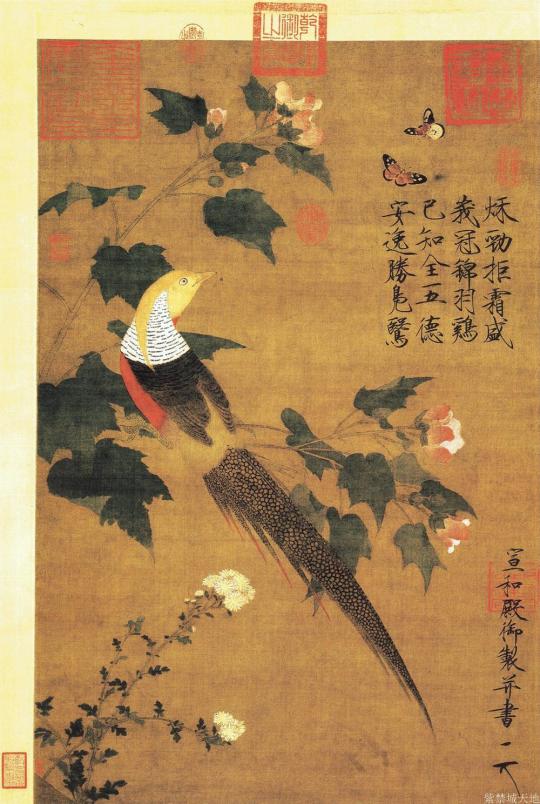

Emperor Huizong of Song (Chinese) • Golden Pheasant and Cotton Rose Flowers with Butterflies (gongbi painting) • 11th century

The name "gongbi" is from the Chinese "gong jin", meaning 'tidy' (meticulous brush craftsmanship). The gongbi technique uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimits details very precisely and without independent or expressive variation.

#still life#art#chinese art#11th century chinese art#painting#gongbi painting#art of the still life blog#emperor huizong of song

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think it sure is something that the unambiguously-framed-as-evil disciples of sanctus medicus are the ones whose writings and hierarchy are carefully crafted to resemble daoist and buddhist scriptures and practices... the buddhist compassion bent to the salvation of all sentient beings . the daoist personal and technical pursuit of immortality. that one scripture they make us copy has all of the framing details of a buddhist sūtra. it begins with "thus i have heard" like almost all buddhist sūtras do. it casts yaoshi in the mold of the thousand-armed form of the bodhisattva avalokiteśvara. the very name "yaoshi" is the chinese translation of the name of the medicine buddha Bhaiṣajyaguru. the "Scripture of the Yellow Pneuma Yang Essence" (黃氣陽精經) is literally the title of a medieval shangqing daoist scripture. some of the disciple enemies are called Internal Alchemists — you know, the highly popular daoist tradition. it just so happens that the imperial state has periodically engaged in the proscription of both buddhism and daoism as heterodox teachings (up to modern times with the cultural revolution, if you like). i'm not explicitly connecting these two things (a lot more needs to be said in various avenues)... but i do wish they treated the followers of yaoshi with more than just claretwheel temple lmao. also. the homoerotic potential in those dan shu diaries is insane. i was so disappointed when they gave her a whole quest as well as these diaries... only to just kill her right after in a relatively minor boss fight...

#i ought to add here that various imperial states also blended either daoism buddhism or both into their ruling ideologies#such as xuanzong of tang or huizong of song's daoistic regimes#or wu of liang's buddhistic one#however the history of favor is balanced out by a history of state persecutions...

1 note

·

View note

Text

i tried making matcha the daguan way today and ? this is so much better holy shit

0 notes

Text

Auspicious Cranes, 112

Northern Song dynasty, China

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

51 x 138.2 cm

Collection of the Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang

A flock of twenty cranes fly against a blue sky, while rolling clouds encircle the roof tiles and ornaments of the city gates below. The image records an auspicious event (a sign of good fortune) witnessed over the capital city of Kaifeng in 1112, as indicated by an inscription and poem by Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) to the left of the painting. Huizong was widely regarded as an ineffective ruler, and his reign hastened the fall of the country to invaders from the north. As if to counter the reality of his poor statesmanship, the painting conveys an image of harmony between nature and humanity—the good omen of cranes emerges from clouds (nature) over the architecture of the capital (the human world). The painting, followed by an inscription and poem, together comprise Auspicious Cranes and suggest that the emperor (like all emperors) held the “Mandate of Heaven,” or the heavenly right to rule (tīanmìng 天命).

Auspicious imagery Mounted on a handscroll that unfurls from right to left, Auspicious Cranes is laid out like a historical document, one that records a natural phenomenon that was interpreted as a good omen for the dynasty. Each pictorial element appears stylized and descriptive—for instance, the flying cranes are pictured with their wings flattened and outstretched, and their legs are rendered as a pair of near parallel lines, recalling motifs seen in tomb murals or textiles (both earlier and later, such as a Portrait of Minister Gu Lin from 1544). This visual mode speaks to both the veracity and otherworldliness of the sighting, in that it accurately portrays the recognizable features of each element but does not characterize them with a lifelike demeanor.

As the inscription reveals, the actual event began in 1112 with a sighting of auspicious clouds over Kaifeng. Clouds and mists represent the vital forces of the universe (qì 氣) in Daoist thought. As residents of the city beheld the extraordinary sight of the clouds, a flock of cranes descended from the clouds and formed over the rooftops—a sign that all was in accord under Heaven. Auspicious images appear as early as the first paintings in China, as seen on tombs, textiles (such as Lady Dai's funeral banner), and murals, and typically embody multiple wishes for good outcomes. They rely on symbols (such as cranes that evoke long life and immortality), to characterize a particular moment or event. Auspicious images may appear in images created in honor of weddings, retirements, or farewells, and other significant occasions, both to delight the eye and offer a blessing. It is possible that certain auspicious images may correspond to traditions and rituals at the court, such as music and dances. Some also may be efficacious, meaning that the images were believed to have embodied the omens and so could bring into being the wish itself.

To Emperor Huizong and his subjects, the sight of clouds and cranes likely signaled a blessing of peace and harmony in the empire. Following the painting of Auspicious Cranes, the inscription and poem recount the moment that the common people witnessed the clouds and cranes materialize over the imperial palace. The text describes people bowing in reverence to the unusual sight, and the gestures of onlookers could be understood as bolstering the legitimacy of the emperor’s reign. Only those close to the emperor would have seen this work, such as highly-ranked members of the court who may have had doubts about Huizong's capabilities as a ruler.��Considering the importance of capturing this image in words and pictures, along with what historians have described of Huizong’s incompetency, it seems that he greatly welcomed this sign of good luck. The imperial brush The inscription and poem accompanying Auspicious Cranes expand our understanding of the picture and its historical context. The calligraphy is composed in “slender gold script,” a style of writing demonstrated by firm, thin strokes with crisp, elegant brushstrokes—like melted gold applied by brush. Slender gold script is specifically associated with Huizong, and therefore conveys the prestige and authority of the emperor. Moreover, the signature notes that it is signed with the “imperial brush” of the emperor (yubi 御筆). Although Huizong did not always write or even sign the works himself, the imperial brush is a mark of his agency. In other words, other officials or even palace ladies may have composed works in the slender gold script under Huizong’s direction and to serve his purposes. Such works, typically poems, nonetheless bear the mark of the imperial brush, and therefore they are still considered to be works by Huizong. The legacy of Emperor Huizong While Emperor Huizong is regarded as an utter failure who contributed to the end of the Northern Song dynasty, his interest in painting, poetry, and calligraphy (“the three perfections”) laid the foundation for new levels of artistic expression. To this end, he first assembled an enormous imperial collection of painting, calligraphy, and antiquities from the past, which served as a foundation for the rigorous study of classical traditions. He then invited leading artists throughout the empire to come to work at the palace workshops, institutionalizing painting traditions and recognizing painting as a respected profession. Scholars have suggested that Auspicious Cranes reflects the elegant style of the Imperial Painting Academy (the artists who worked for the Northern Song court). Moreover, Emperor Huizong used painting, poetry, and calligraphy to capture this auspicious sighting in an image that still defines his legacy today. Additional resources: Maggie Bickford, “Emperor Huizong and the Aesthetic of Agency,” Archives of Asian Art 53, no. 1 (2003): pp. 71–104. Peter C. Sturman, “Cranes Above Kaifeng: The Auspicious Image at the Court of Huizong,” Ars Orientalis 20 (1990): pp. 33–68. Essay by Dr. Kristen Loring Brennan (Source: Khan Academy)

Cranes of Good Omen, emparor Huizong (patron only?) c. 1112, China.

hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 51 × 138.2 cm. (Liaoning Provincial Museum)

#Northern Song dynasty#Song dynasty#symbolism#painting#calligraphy#Zhao Ji#Huizong of Song#12th century#Chinese#art#art history#politics#birds#crane#architecture#Kaifeng#iconography#ink#colour#Liaoning Provincial Museum#language#Kristen Loring Brennan

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 瘦金体 (slender gold script, invented by Zhao Ji the Huizong emperor of Song Dynasty almost a thousand years ago) grinding I’ve been doing is paying off, writing this was pretty smooth with only a few sus characters.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emperor Huizong (attri. to, 1082-1135) "Magpies and Spring Flowers," album leaf, ink and color on silk, nd

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's apocryphal Sun Tzu quote

Sometimes, coming back is way worse than leaving.

Emperor Huizong - Turtledove on a Peach Branch, 1120 AD

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

For #WorldSparrowDay:

Yu Feian (Chinese, 1888-1959)

The Five Nobilities, mid-20th c.

Fan; ink & color on paper

>The artist called this painting The Five Nobilities, a play on the fact that the word for “sparrow” (que 雀) sounds like the word for “noble rank” (jue 爵). According to the artist’s inscription, he copied the composition after a painting attributed to the Song dynasty emperor Huizong (1082–1135).<

From “Noble Virtues: Nature as Symbol in Chinese Art” 2023 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York

#animals in art#animal holiday#20th century art#museum visit#bird#birds#sparrow#sparrows#Chinese art#East Asian art#Asian art#fan#Yu Feian#exhibition#Metropolitan Museum of Art New York#World Sparrow Day

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Auspicious Cranes By Zhao Ji, Emperor Huizong of Song (1082-1135) Song Dynasty

Starting the Year of Dragon well with this auspicious painting :)

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little bit of historical context for Heroes

Heroes is roughly based on history of the ending of Northern Song dynasty (960-1127).

Chancellor Cai is a real historical figure. And there's also Liu Anshi if you want to read about him (x)

"Cai Jing (1047–1126), courtesy name Yuanchang (元���), was a Chinese calligrapher and politician who lived during the Northern Song dynasty of China." (Wiki)

But look at the dates: Cai Jing died in 1126 and Northern Song ended in 1127.

From wiki again:

"This decline can also be attributed to Cai Jing (1047–1126), who was appointed by Emperor Zhezong (1085–1100) and who remained in power until 1125. He revived the New Policies and pursued political opponents, tolerated corruption and encouraged Emperor Huizong (1100–1126) to neglect his duties to focus on artistic pursuits. Later, a peasant rebellion broke out in Zhejiang and Fujian, headed by Fang La in 1120. The rebellion may have been caused by an increasing tax burden, the concentration of landownership and oppressive government measures.

While the central Song court remained politically divided and focused upon its internal affairs, alarming new events to the north in the Liao state finally came to its attention. The Jurchen, a subject tribe of the Liao, rebelled against them and formed their own state, the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). The Song official Tong Guan (1054–1126) advised Emperor Huizong to form an alliance with the Jurchens, and the joint military campaign under this Alliance Conducted at Sea toppled and completely conquered the Liao dynasty by 1125."

So events of Heroes happened somewhere in 1125-1126. Su Mengzhen comes from Nothern borders where he is fighting Liao (1125 probably) and in last episode there's Cai Jing death so it's probably 1126 (not how it happened in real history but it still counts)

What we have is the country on verge of collapsing: weak emperor, corrupted and incapable government, people under tax burden ready to rebel, outside Liao and Jurchen (they weren't mentioned in Heroes but "during the latter invasion, the Jurchens captured not only the capital, but the retired Emperor Huizong, his successor Emperor Qinzong, and most of the Imperial court." Wiki again).

The interesting question is what about House of Sunset Drizzle and Six Half Hall? What is their place in all this mess? And how much power do they have? But this is for the next post, 😁 I'll probably write it 😁

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

I remember there was a strange story involving Erlang. I heard the title from Baiku. I don't know if it was an old story in the end. But it was about how a woman thought that her husband was Erlang. I didn't know the context very well because I had to translate it with Google translator but anyway, you know, the story didn't make much sense bc the translate sucks. But in the end I didn't know if maybe the woman was crazy or what kind of situation it was.

The story you are thinking about is probably 勘皮靴单证二郎神, and it is very significant because it is likely where the name "Yang Jian" comes from.

Like, Yang Jian is this real historical figure in the Song dynasty——an extremely corrupt eunuch who was favored by Song Huizong, aka "Mr. Great Artist + Terrible Emperor".

In this story from Feng Menglong's 醒世恒言, one of Huizong's consorts, Lady Han, got sick, and Yang Jian was asked to host her inside his mansion while she recovered.

She heard that Erlang Shen was very efficient at answering prayers, so she went to his temple to pray...and, after developing a huge crush on his statue and going "Gosh, I wish my future husband is as handsome as Erlang here", met what appeared to be the god himself in flesh!

The god told her that she was an immortal lady incarnate, and if she indeed wished for a romantic relationship, he was happy to oblige. So they basically started an affair, until Yang Jian got suspicious, started investigating the matter, caught them in the act, and then hired a Daoist to exorcise what appeared to be a demon impersonating Erlang.

The first exorcism failed, but the second caused the guy to flee and leave one of his boots behind. By basically checking the labels (yes, it has a label) on the boot and tracing its origins, Yang Jian found the impersonator in question——a temple attendant named Sun Shentong, who overheard Lady Han's prayer and used it to manipulate her.

The guy was sentenced to death, Lady Han was dismissed from the palace, married a regular merchant, and lived a long, uneventful life, and that was that.

"But wait, Yang Jian is the eunuch playing detective, not Erlang or the impostor! Why did his name become the most widely recognized 'real name' for Erlang?"

Welcome to how Chinese folk religion works, where names that sound similar/appear in the same stories together can become the basis of a whole new canon a/o characterization, especially when popularized by later vernacular novels like FSYY.

#erlang shen#yang jian#chinese folklore#investiture of the gods#chinese literature#chinese history#chinese folk religion

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Auspicious Cranes, attributed to Huizong of Song (1082-1135), Chinese emperor and painter during the Song Dynasty.

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't know if this has been asked but how chaotic do you think a palace drama would be if the entire harems and children of say Kangxi, Xuanzong of Tang, or Huizong of Song and all the conflicts that happened with them were dramatized (especially since the three mentioned kept a large number of concubines who bore them a lot of children?)

You'd need a Game of Thrones length show to unpack all of this.

7 notes

·

View notes