#house of valois burgundy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (1433-1477).

#royaume de france#duché de bourgogne#Charles le Téméraire#duc de bourgogne#maison de valois#bourgogne#valois bourgogne#house of valois#kingdom of france#house of valois burgundy#burgundy#charles the bold#duke of burgundy#equestrian portrait#in armour

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Women Week || Favorite Queen or Queen-adjacent ↬ Jeanne “la Boiteuse” de Bourgogne

Philip VI’s relentless persecution of Robert of Artois long after the man had become a broken and impoverished exile is revealing of his character. No doubt much of the venom was due to the influence of the Queen (the Duke of Burgundy’s sister). Philip himself, although he was not by nature a vindictive man, was an extremely superstitious and unconfident one. He took most seriously the threats which Robert hurled at him from abroad to foment rebellion in France and to strike down his children by sorcery. — Trial by Battle: The Hundred Years War, vol. 1 by Jonathan Sumption Philip VI’s queen, Jeanne, was the sister of the duke of Burgundy and headed a faction at court. A contemporary chronicler wrote about her: “the lame Queen Jeanne de Bourgogne... was like a king and caused the destruction of those who opposed her will”. — The Valois: Kings of France, 1328–1589 by Robert J. Knecht

#medievalwomenweek#joan of burgundy#house of valois#french history#european history#women's history#history#medieval#house of burgundy#nanshe's graphics

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

GUESS WHO’S THE BIRTHDAY BOY!

#Charles the Bold#birthday boy#House of Valois#Duke of Burgundy#Count of Charolais#and the list goes and goes

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thread about Joanna of Castile: Part : 10 “A Storm of Jealousy: Juana and Philip's Turbulent Reunion"

By May 1504, Juana was in Burgundy. Juana’s reunion with Philip and the children was joyful.

But soon afterwards she suspected, or discovered, an affair between Philip and a noblewoman in her entourage:

“They say,” writes Martire, “that, her heart full of rage, her face vomiting fames, her teeth clenched, she rained blows on one of her ladies, whom she suspected of being the lover, and ordered that they cut her blond hair, so pleasing to Philip …”

Philip’s response was equally furious. He had “thrown himself” on his wife and publicly insulted her.

Sensitive and obstinate, “Juana is heartbroken … and unwell …”. Isabel “suffers much, astonished by the northerner’s violence.

Maximilian’s biographer, Wiesfecker, describes Juana’s response as:

"The symptom of a pathological, passionate, if not unfounded, Haßliebe, fomenting continual strife. "

Juana would have known for years about Philip's visits to the baigneries and his more casual relationships with women. However, this affair seemed to pose a direct challenge to her standing and dignity. Juana knew her faults and had tried to limit them. In 1500, after becoming princess, she had asked Isabel to send her an honest and prudent Spanish lady who:

“Knows how to advise her, and where she sees something out of order (‘deshordenado’) in her conduct could say so as servant and adviser but not as an equal because, even if the advice were good, if expressed in a disrespectful way it would create more anger in she to whom it was said than it would allow for correction.”

Sources: Fleming, G. B. (2018). Juana I: Legitimacy and Conflict in Sixteenth-Century Castile (1st ed. 2018 edition). Palgrave Macmillan.

Fox, J. (2012). Sister Queens: The Noble, Tragic Lives of Katherine of Aragon and Juana, Queen of Castile. Ballantine Books.

Gómez, M. A., Juan-Navarro, S., & Zatlin, P. (2008). Juana of Castile: History and Myth of the Mad Queen. Associated University Presse.

#joanna of castile#juana i of castile#juana la loca#philip the handsome#isabel#european history#spanish monarchy#spanish princess#infanta#irene escolar#raul merida#flanders#vlaanderen#Huis Habsburg#House of Valois-Burgundy#Filips I van Castilië#Philippe le Beau

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tomb of Mary of Burgundy in the Church of Our Lady, Bruges, 1501

#mary of burgundy#new post#historical#bruges#burgundy#medieval#historical fashion#history#medieval fashion#effigy#duchy of burgundy#coats of arms#bronze#gilt#Tomb effigy#house of habsburg#House of Valois-Burgundy#House of Valois#Maximilian I#Holy Roman Emperor#Philip the Handsome#1500s#1480s#gothic art#International Gothic#renaissance#Northern Renaissance#renaissance fashion

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary of Burgundy (1386–1428) was a Duchess of Savoy by her marriage to Amadeus VIII of Savoy, who was later known as Antipope Felix V.

0 notes

Text

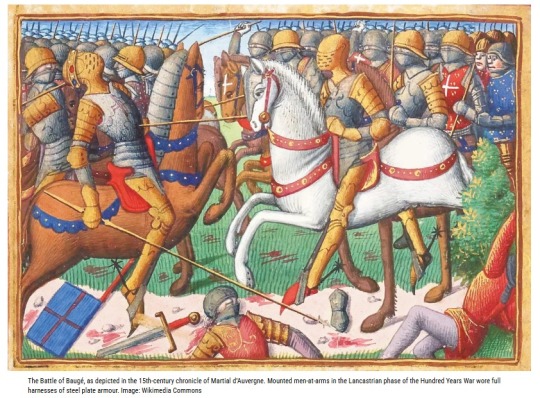

On 22nd March 1421, Franco-Scottish army. under the Earl of Buchan defeated English forces at Bauge in Anjou, France.

Not heard of it? That’s because the history we were taught in school was all anglicized, oh we did get a wee bit about the 100 year war, mainly Agincourt, because the English won that day, or possibly Crecy, another victory for them, Bauge and many other times the English were gubbed are ignored.

Ok you might be wondering why I say a Scottish army, historians all say that the majority of the troops were Scottish soldiers, aye there was a few Frenchmen fighting on “our” side, but this was very much a Scottish victory over an English army.

This all goes down as part of the Auld Alliance, which was signed in 1295 by King John Balliol and Philip IV of France. The Alliance was renewed periodically after that date and by the 1410s it was very much “in play” as Henry V of England initiated the third phase of the Hundred Years War, often known to historians as the Lancastrian War.

In 1418, it was the French Dauphin who called on his Scottish allies for assistance in his efforts to curtail Henry’s depredations after the great battle of Agincourt in 1415. It had to be the Dauphin, or Crown Prince, who sought help from Scotland because the French king, Charles VI, was already showing signs of the mental illness that would eventually see him nicknamed Charles the Mad.

The French aristocracy had split into two factions with many supporting the Duke of Burgundy in his aspirations to take the throne, while many others stayed loyal to the King and the House of Valois, known as the Armagnacs. Increasingly it was the teenaged Dauphin, the future Charles VII, who made all the major decisions for the Valois regime and, faced with the Burgundy alliance with Henry V and the surrender of many of his own forces, he sent for help from Scotland.

The complicating factor at the time was that King James I of Scotland was still a prisoner of the English, albeit that he was part of the royal household of Henry, whom he greatly admired, and he would actually fight with the English army against the French in France in 1420. In charge of Scotland was the Duke of Albany, Robert Stewart, who had become regent when James was first captured by the English in 1406 while en route to France.

There had been no large battles between the Scots and the English since the Battle of Homildon Hill, or Humbleton Hill, in 1402 won by the English, but with England preoccupied with France, Albany no doubt felt it safe to respond positively to Scotland’s oldest ally. By 1419, there was also peace of a sort along the border with England so the Scots could afford to send an army of around 6000 men including men at arms, spearman and archers to serve alongside the remaining French royal army.

Henry V’s of England’s brother, Thomas the Duke of Clarence led 10,000 men south towards the Loire. They set about besieging the castle at Bauge when the Scots were garrisoned, they made contact with them the day before Good Friday. A truce was reached, lasting until Monday, so that the combatants could properly observe the religious occasion of Easter.

The English lifted their siege and withdrew to nearby Beaufort, while the Scots camped at La Lude. However, early in the afternoon of Saturday Scottish scouts reported that the English had broken the truce and were advancing upon them hoping to take them by surprise. The Scots rallied hastily and battle was joined at a bridge which the Duke of Clarence, with banner unfurled for battle, sought to cross. A detachment of a few hundred men under Sir Robert Stewart of Ralston, reinforced by the retinue of Hugh Kennedy, held the bridge and prevented passage long enough for the Earl of Buchan to rally the rest of his army, whereupon they made a fighting retreat to the town where the English archers would be ineffective.

Both armies now joined in a bitter melee that lasted until nightfall. During this time Sir John Carmichael of Douglasdale broke his lance unhorsing the Duke of Clarence; since that day the Carmichael coat of arms displays an armoured hand holding aloft a broken lance in commemoration of the victory. Once on the ground, the Duke was killed by Sir Alexander Buchanan. The English dead included the Lord Roos, Sir John Grey and Gilbert de Umfraville, whose death directly led to the extinction of the male line of that illustrious family, well known to the Scots since the Wars of Independence. The Earl of Somerset and his brother were captured by Laurence Vernon (later elevated to the rank of knight for his conduct), the Earl of Huntingdon was captured by Sir John Sibbald, and Lord Fitz Walter was taken by Henry Cunningham.

On hearing of the Scottish victory, Pope Martin V passed comment by reiterating a common mediaeval saying, that the Scots are well-known as an antidote to the English.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of French Princesses at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

This list is composed of princesses of France until the end of the House of Bourbon; it does not include Bourbon claimants or descendants after 1792.

The average age at first marriage among these women was 15.

Judith of Flanders, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 12 when she married Æthelwulf, King of Wessex in 856 CE

Rothilde, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 19 when she married Roger, Count of Maine in 890 CE

Emma of France, daughter of Robert I: age 27 when she married Rudolph of France in 921 CE

Matilda of France, daughter of Louis IV: age 21 when she married Conrad I of Burgundy in 964 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Reginar IV of Hainault in 996 CE

Gisela of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Hugh of Ponthieu in 994 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Robert II: age 13 when she married Renauld I, Count of Nevers in 1016 CE

Adela of France, daughter of Robert II: age 18 when she married Richard III of Normandy in 1027 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Philip I: age 16 when she married Hugh I, Count of Troyes in 1094 CE

Cecile of France, daughter of Philip I: age 9 when she married Tancred, Prince of Galilee in 1106 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Louis VI: age 14 when she married Eustace IV, Count of Boulogne in 1140 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry I, Count of Champagne, in 1159 CE

Alice of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Theobald V, Count of Blois in 1164 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry the Young King in 1172 CE

Alys of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 35 when she married William IV of Ponthieu in 1195 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 8 when she married Alexios II Komnenos in 1180 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Philip II: age 13 when she married Philip I of Namur in 1211 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 14 when she married Theobald II of Navarre in 1255 CE

Blanche of France. daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married Ferdinand de la Cerda in 1269 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married John I, Duke of Brabant in 1270 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 19 when she married Robert II, Duke of Burgundy in 1279 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Philip III: age 22 when she married Rudolf III of Austria in 1300 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Philip III: age 20 when she married Edward I of England in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip IV: age 13 when she married Edward II of England in 1308 CE

Joan II of Navarre, daughter of Louis X: age 6 when she married Philip III of Navarre in 1318 CE

Joan III, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Odo IV, Duke of Burgundy in 1318 CE

Margaret I, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Louis I of Flanders in 1320 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip V: age 11 when she married Guigues VIII of Viennois in 1323 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Charles IV: age 17 when she married Philip, Duke of Orleans in 1345 CE

Joan of Valois, daughter of John II: age 9 when she married Charles II of Navarre in 1352 CE

Marie of France, daughter of John II: age 20 when she married Robert I, Duke of Bar in 1364 CE

Isabella, daughter of John II: age 12 when she married Gian Geleazzo Visconti in 1360 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles V: age 8 when she married John of Berry, Count of Montpensier in 1386 CE

Isabella of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 6 when she married Richard II of England in 1396 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VI: age 5 when she married John V, Duke of Brittany in 1396 CE

Michelle of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 14 when she married Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1409 CE

Catherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 19 when she married Henry V of England in 1420 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married Charles I, Duke of Burgundy in 1440 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married John II , Duke of Bourbon in 1447 CE

Yolande of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Amadeus IX, Duke of Savoy in 1452 CE

Magdalena of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Gaston, Prince of Viana in 1461 CE

Anne of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Peter of Bourbon in 1473 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Louis XII in 1476 CE

Claude of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 15 when she married Francis I in 1514 CE

Renée of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 18 when she married Ercole II d'Este in 1528 CE

Madeleine of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 17 when she married James V of Scotland in 1537 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 36 when she married Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy in 1559 CE

Elisabeth of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 13 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1559 CE

Claude of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married Charles III, Duke of Lorraine in 1559 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 19 when she married Henry IV in 1572 CE

Elisabeth of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Philip IV of Spain in 1615 CE

Christine of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy in 1619 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 16 when she married Charles I of England in 1625 CE

Louise Élisabeth of France, daughter of Louis XV: age 12 when she married Philip, Duke of Parma in 1739 CE

Marie-Thérèse, daughter of Louis XVI: age 21 when she married Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême in 1799 CE

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think that Philip the Good, heady with his success, seized the opportunity to erect Anne of Burgundy's tomb as a memorial both to his desire for reconciliation about the different branches of the Valois house and to their recent political differences. Upon her death Anne chose to be buried in the Celestine Church, a monastery with royal and Armagnac associations. Her exact motives for select- ing this site are not known. Father Beurrier claimed Anne was impressed by the monks' unusual piety. Anne may well have shared her brother's desire for a reconciliation of the Valois house since with her inclusion the Burgundians, the cadet branch of the Valois house, join the royal line and its Orleans offshoot. As mentioned, the Celestine Church was a royal foundation. Besides the portal statues and entrails tomb of Queen Jeanne, stained glass portraits of Charles V and his father John II (1350-1364) were set in the choir windows. Since the deaths of John II and his wife Jeanne of Burgundy, the monastery was a favorite burial site for royal viscera and hearts. The hearts of John II, Jeanne of Burgundy, Charles VI and his wife Isabeau of Bavaria were all enshrined here. The Celestine Church was also the mausoleum for the Dukes of Orleans and their families. The Orleans Chapel, located immediately to the south of the choir, had been founded by Louis of Orleans, younger son of Charles V and brother of Charles VI, a few years before he was murdered in 1407 in Paris on the orders of John the Fear- less. Louis had been the head of the Armagnac or anti- Burgundian political party in France. That Anne wished to be buried near her father's bitterest enemy cannot be merely coincidental. Rather the movement towards reconciliation had been initiated before Anne's death. In 1440 Philip the Good won over the last of his Armagnac foes when he ransomed Charles, Duke of Orleans, who had languished in England ever since his seizure in 1415 at the Battle of Agincourt.

Jeffrey Chipps Smith, "The Tomb of Anne of Burgundy, Duchess of Burgundy, in Musée du Louvre", Gesta, Vol. 23, No. 1 (1984)

#while i really like the idea of anne having a say in her burial and the way it indicates her political nous...#would she really be advocating for burial in the celestine church to reconcile with charles vii and the armagnacs#when she was happily married to the regent of france and some years before it became clear the english were losing?#and john buried her here so he was presumably ok with whatever reason she wanted to be buried there#and i really doubt he'd be ok with 'make peace with charles vii' in 1432#anne of burgundy#philip the good duke of burgundy#graves and tombs#historian: jeffrey chipps smith

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if it's obvious, but I admit I'm a bit confused on there being both Dukes of Burgundy and also Counts of Burgundy and what's the difference?

Because the medieval border region between France and the HRE can't ever be straightforward and rational, there was both a Duchy and a County of Burgundy. And to make matters more confusing, they were right next to each other:

The most significant political difference between them is that the Duchy of Burgundy was part of the Kingdom of France (although they didn't always agree on that) and the County of Burgundy (better known as the Free County or the Franche-Comté) was part of the Holy Roman Empire.

However, and this is an example of how complicated medieval politics could get, both Burgundies were in personal union under the House of Valois-Burgundy, and thus were part of the Burgundian State that Charles the Bold very much wanted to make the core of his revived, independent, and coequal Kingdom of Burgundy. It didn't work out thanks to the Swiss pikemen and the treacherous Hapsburgs, but it came very close to becoming a thing.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (1342-1404). Unknown artist.

#philippe le hardi#duc de bourgogne#duché de bourgogne#bourgogne#Philippe II le Hardi#philip the bold#duke of burgundy#royaume de france#kingdom of france#duchy of burgundy#maison de valois#house of valois#engraving#in armour#engravings#count of flanders#count of artois#count of burgundy#valois bourgogne#regent of france#régent de france#royalty

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 6: Yolande of Aragon

Yolande of Aragon (also known as Yolanda de Aragón and Violant d'Aragó.)

Born: 11 August 1381 Died: 14 November 1442

Parents: John I of Aragon and Violant of Bar Duchess of Anjou and Countess of Provence Children: Louis III, Duke of Anjou Marie, Queen of France René, King of Naples Yolande, Countess of Montfort l'Amaury Charles, Count of Maine

Yolande was born in Zaragoza, Aragon as the eldest daughter of John I of Aragon and his second wife Violant of Bar, granddaughter of John II of France.

In 1387 a marriage offer came through the mother of the King of Naples, Louis II. At 11 years old she signed a document that disallowed any marriage promises made by ambassadors. In 1395 another marriage offer came from Richard II of England. After her father’s death, her uncle was convinced to marry Yolande to Louis. She was forced to retract her protest to the marriage.

Yolande and Louis were married on December 2, 1400 in Arles. Despite her initial rejection and her husband’s illness, they had 5 children.

As a daughter of a king, she had a claim to the throne of Aragon after her uncle’s death without an heir. The laws at the time favored male heirs, thus after two years without a king they chose Ferdinand the son of Eleanor of Aragon and John I of Castile. Yolande’s son, Louis, was the Anjou claimant to the throne, although his claim was excluded by the Pact of Caspe..

In the second phase of the Hundred Years' War, Yolande supported the French, particularly the Armagnacs. After the attack on the Dauphin of France by the duke of Burgundy, she and her husband refused the marriage of their son Louis to the duke’s daughter. She met with the Queen of France to arrange the marriage of her daughter and the third son of the queen, Charles.

When Charles became the Dauphin and his mother worked against his claim, Yolande became a substitute mother for the teenager. She protected him against plots, funded and helped his cause. Yolande removed Charles from his parents' court and took him to her residence where he received Joan of Arc. After his marriage to her daughter Marie she became his mother-in-law and was heavily involved in the conflict of the House of Valois. She succeeded in having him crowned.

As her husband was often away fighting in Italy, Yolande preferred to hold court in Angers and Saumur..

After the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, the Duchy of Anjou was threatened and Louis II had Yolande, their children and Charles moved to Provence.

On 29 April 1417, Louis II died leaving Yolande, aged 33, in control of the House of Anjou. Yolande acted as regent for her young son.

Yolande not only took care of the House of Anjou but also of Charles’s cause. Yolande supported Joan of Arc from the beginning and practiced political moves to ensure the success of Charles.

She retired to Angers and then to Saumur, where she continued to play a role in politics. From at least 1439 onwards Yolande took care and prepared her granddaughter Margaret of Anjou for marriage.

She died on 14 November 1442 at the town house of the Seigneur de Tucé in Saumur.

She is described as "the prettiest woman in the kingdom", a wise and beautiful woman and her grandson Louis XI of France described her as "a man's heart in a woman's body”.

#women history#women in history#french history#joan of arc#margaret of anjou#anjou#15th century#medieval#medieval history#1400s#france

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello my friend, can you share some interesting facts about Philip the Good and Charles the Bold?

I love his question! Well, here they are:

Philip the Good:

-He was the son of the legendary John the Fearless and his Bavarian wife, Margaret of Bavaria-Straubing.

-He sold Joan of Arc to the English, of whom he had become ally after his father was killed by the friends of Charles VII of France.

-He was kind of a lavish dude, serving roasted swans and peacocks during his feasts.

-He married thrice; firstly to Michelle of Valois, sister of Charles VII, of whom he had a daughter who died young; secondly, to his uncle’s widow, Bonne of Artois; and finally, to a Portuguese infanta woman he had rejected once, Isabella of Portugal. Both were in their early thirties, but their union was surprisingly fruity, having three children (of whom the last and only surviving would become Charles the Bold).

-He was the founder of the Order of the Golden Fleece, made to honour his wedding to his Portuguese wife.

-He was also quite amorous having at least thirty illegitimate children.

-His wife Isabella and his infant son Charles Martin were briefly kidnapped by rebels in the city of Bruges, to which he hastily responded by seizing the city economically.

-He lived to his seventies!

Charles the Bold.

-He was the youngest knight of the Golden Fleece in his time, being ordered within days of being born.

-He played music! He was quite the music lover, seemingly quitting holy music himself. He also sang, but it appears that he did not have that much of a pleasant voice.

-He met Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus (history’s greatest crossovers).

-He had a complicated relationship with his father the Good Duke, based in the fact that he had to often beat with his demanding upraising (learning to ride at four; almost fighting to death as eighteen as his father prompted his adversary to fight “harder”) and yet the duke’s fears of loosing his only legitimate son made him force him out of his first battlefield experience with lies of the duchess being terribly ill. He misliked his father’s amorous tendencies, but ultimately, when his father fell ill and nearer death, he hastened to his deathbed and wept most soundly during his funeral, reportedly tearing his own hair and falling to the floor in the church.

-He firstly married at age six to a French princess, Catherine of Valois. This union lasted eight years, until she passed away of tuberculosis; she supported his musical inclination and was reportedly very dear to him. Most tragically, his next wife, Isabelle of Bourbon, died of tuberculosis fairly young too.

-He was most likely celibate (his only child was Mary of Burgundy, born to his wife Isabelle).

-He burned Liege. Twice.

-Had he survived Nancy and lived as much as his father and maternal grandfather did, he would have lived enough to meet his great grandson and namesake, Charles V.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

So the first flag is NOT of the Kingdom of Burgundy, but it is actually medieval (though late medieval. You're not that far by saying Renaissance actually)

The first kingdom of Burgundy died in 843, before the rise of modern heraldry: as far as we know it didn't have a flag (not in the modern sense of it in any case). The second kingdom of Burgundy was most usually called the kingdom of Arles at the time, sometimes the kingdom of Burgundy-Provence; it died in 1378 and its coat of arms was completely different (three gold stripes and two red stripes vertically- sorry idk the terms in English, but it was modelled after the coat of arms of the counts of Provence)

The flag displayed here is the one of the dukes of Burgundy, specifically the house of Valois-Bourgogne. The duchy of Burgundy coexisted with the second kingdom of Burgundy for three or four centuries, meaning the two were different political entities for that time. That flag was used in the mid-1400s and the modern flag of the Région Bourgogne is modelled after it

#source : I'm from Provence and I lived in Burgundy for 5 years and a half#I know the history of my homeland and I've seen that flag very often thank you very much

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet; containing an account of the cruel civil wars between the houses of Orleans and Burgundy; of the possession of Paris and Normandy by the English; their expulsion thence; and of other memorable events that happened in the kingdom of France, as well as in other countries ... Beginning at the year MCCCC. where that of Sir John Froissart finishes, and ending at the year MCCCCLXVII. and continued by others to the year MDXVI. Translated by Thomas Johnes.

Description

Tools

Cite this

Main AuthorMonstrelet, Enguerrand de, -1453.Related NamesJohnes, Thomas, 1748-1816 Language(s)English Published[n.p.] At the Hafod Press by J. Henderson, 1809. SubjectsFrance > France / History > France / History / House of Valois, 1328-1589. History Physical Description5 v. 30 cm.

0 notes

Text

Matilda of Hainaut (November 1293 – 1331), also known as Maud and Mahaut, was Princess of Achaea from 1316 to 1321. She was the only child of Isabella of Villehardouin and Florent of Hainaut, co-rulers of Achaea 1289–1297. After Florent's death in 1297, Isabella continued to rule alone until she remarried to Philip of Savoy in 1300. Per arrangements made with King Charles II of Naples, Isabella was not allowed to marry without his consent and after Philip failed to adequately participate in the king's campaigns against Epirus, Charles in 1307 revoked their rights to Achaea. Matilda, just fourteen years old, tried to press her claim as their heir but was refused by the bailiff Nicholas III of Saint Omer, who instead chose to wait for orders from Naples. Shortly thereafter, Charles appointed his favorite son, Philip of Taranto as the new Prince of Achaea.

Philip of Taranto spent little time in Greece and appointed as his bailiff Guy II de la Roche, Matilda's husband. Guy did not last long in this position, dying in 1308. Matilda was then betrothed by Philip of Taranto to his eldest son, Charles of Taranto. In 1313, this betrothal was broken off and Matilda was married to Louis of Burgundy as compensation to the House of Burgundy due to Philip of Taranto in the same year having married Catherine of Valois, previously betrothed to Hugh V, Duke of Burgundy. Philip of Taranto also renounced his rulership of Achaea and bestowed the Principality of Achaea on Matilda and Louis. Before they had travelled to their new domain, Achaea was seized in 1315 by the usurper Ferdinand of Majorca. Matilda and Louis landed in Achaea in early 1316 and secured control of the principality after the defeat and death of Ferdinand in the Battle of Manolada. Their co-rule did not last long; Louis died less than a month later, widowing Matilda for the second time.

The new king of Naples, Robert, wished to exploit Matilda's uncertain position to gain the principality back for his family. In 1317, he proposed that Matilda should marry his brother, John of Gravina. Matilda refused as she did not wish to enter into a third political marriage. In 1318, Robert's emissaries abducted the princess and brought her to Naples by force. She was forced to go through a marriage ceremony with John, but she refused to recognize him as her husband. In 1321, Matilda was dragged in front of Pope John XXII who ordered her to obey Robert and marry John, but she still refused. Matilda then confessed that she had secretly married the knight Hugh de la Palisse. No more attempts were made to marry her to John but Robert could now revoke Achaea from her control as she had married without his consent. Robert also fabricated a story that Hugh had made an attempt on his life, and that Matilda was his accomplice, and used this as an excuse to imprison the princess. Matilda spent the rest of her life as a prisoner, first in the Castel dell'Ovo in Naples and then in Aversa, where she died in 1331.

3 notes

·

View notes