#the burgundian state

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Sorry if it's obvious, but I admit I'm a bit confused on there being both Dukes of Burgundy and also Counts of Burgundy and what's the difference?

Because the medieval border region between France and the HRE can't ever be straightforward and rational, there was both a Duchy and a County of Burgundy. And to make matters more confusing, they were right next to each other:

The most significant political difference between them is that the Duchy of Burgundy was part of the Kingdom of France (although they didn't always agree on that) and the County of Burgundy (better known as the Free County or the Franche-Comté) was part of the Holy Roman Empire.

However, and this is an example of how complicated medieval politics could get, both Burgundies were in personal union under the House of Valois-Burgundy, and thus were part of the Burgundian State that Charles the Bold very much wanted to make the core of his revived, independent, and coequal Kingdom of Burgundy. It didn't work out thanks to the Swiss pikemen and the treacherous Hapsburgs, but it came very close to becoming a thing.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Golden Age of Dutch painting: a Prelude

Portrait of Susanna Lunden (née Fourment) or Le Chapeau de Paille, by Peter Paul Rubens (The National Gallery, London) Suzanne Fourment Lunden, portrayed above, was Baroque Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens‘s sister-in-law. In 1630, four years after Rubens’s first wife, Isabella Bran(d)t, died of the plague, fifty-three-year-old Rubens married sixteen-year-old Hélène Fourment. His first marriage…

View On WordPress

#Antwerp#Dutch Golden Age of painting#Eighty Years&039; War#Flanders#Flemish Baroque artist#Hélène Fourment#History#Peter Paul Rubens#Suzanne Lunden#The Burgundian State#The Duchy of Brabant#Twelve Years&039; Truce

1 note

·

View note

Text

Duke Philip "the Good" (1396-1467) of Burgundy

Artist: Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1399 or 1400-1464)

Date: 15th century

Object: Painting

Collection: Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria

Phillip the Good

Philip III the Good (31 July 1396 – 15 June 1467) ruled as Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death in 1467. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty, to which all 15th-century kings of France belonged. During his reign, the Burgundian State reached the apex of its prosperity and prestige, and became a leading centre of the arts.

Duke Philip has a reputation for his administrative reforms, for his patronage of Flemish artists (such as Jan van Eyck) and of Franco-Flemish composers (such as Gilles Binchois), and for the 1430 seizure of Joan of Arc, whom Philip ransomed to the English after his soldiers captured her, resulting in her trial and eventual execution. In political affairs, he alternated between alliances with the English and with the French in an attempt to improve his dynasty's powerbase. Additionally, as ruler of Flanders, Brabant, Limburg, Artois, Hainaut, Holland, Luxembourg, Zeeland, Friesland and Namur, he played an important role in the history of the Low Countries.

He married three times and had three legitimate sons, all from his third marriage; only one legitimate son reached adulthood. Philip had 24 documented mistresses and fathered at least 18 illegitimate children.

#portrait#duke philip the good#duke of burgundy#french history#valois dynasty#burgundian state#painting#oil painting#costume#hat#document#rogier van der weyden#netherlandish painter#netherlandish art#fine art#french nobility#15th century painting#european art#artwork

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some nations and their birth/death date

- Britannia : born around 800BCE (beginning of British Iron Age); died around 500CE, but she had been getting weaker ever since Rome's forces left.

- Rome : born in 753BCE (Rome's fonding); died in 476CE, for obvious reasons

- Gaul (celtic) : born around 700BCE (between the Halstatt and La Tène cultures); died not long after the Gallic wars in 52BCE

- Germania : born around 750BCE (Nordic Iron Age) died not long after Rome's fall

- Frankish Kingdom/Empire: died in 843 (Treaty of Verdun), son of Germania

- Burgundian Kingdom/State: died in 1482 (end of the Burgundian War of Succession), daughter of Germania

- Frisian Kingdom: died 1523 (end or Frisian Freedom after a failed Frisian rebellion), son of Germania (and is either the biological or the adopted father of the Low Countries (or at least the Netherlands))

- France: born shortly before the Gallic Wars, son of Gaul

- England: born around 500 CE (first Anglo-Saxon kingdoms), he would fully become his "own" in 927 with the Kingdom of England, son of Britannia

- Spain: born somewhere during the Roman era, son of Rome

- Portugal: same as Spain, but earlier, son of Rome

- Netherlands: born shortly before the Roman conquest of Gaul (Belgae), son of idk who yet

- HRE: born in 486CE, when the Franks beat the Soissons Domain; died 1806 for obvious reasons, son of the Frankish Kingdom

- Middle Francia/Lotharingia: born in 843CE (Treaty of Verdun); died either 958CE (division of the Kingdom of Lotharingia) or 1190CE (Lower Lotharingia lost its territorial authority), daughter of the Frankish Kingdom

- Austrasia & Neustria: born in 511CE, died in 751CE, those boys were literally twins and they started the tradition of ✨️fratricide✨️ in the family (later carried on by France killing HRE), sons of the Frankish Kingdom

- Prussia: born 1226CE (creation of the State of the Teutonic Order)/born 1th century CE if we consider him an Old Prussian (Baltic tribe), son of how do I know

- Germany: born...1806(Confederation of the Rhine), 1815(German Confederation), 1866 (North German Confederation) or 1871 (Proclamation of the Reich)

Or he's HRE according to some... I don't know he's complicated...

#feel absolutely free to propose other dates if you don't agree or think there can be another date#very west european/germanic centred sorry :(#i have no idea when Germania's children would be born tho so uh yeah sorry#mes blogs#hetalia#historical hetalia#aph rome#aph germania#aph gaul#aph britannia#aph frankish empire#aph burgundian state#aph frisian kingdom#aph france#aph england#aph spain#aph portugal#aph netherlands#aph hre#aph lotharingia#aph austrasia#aph neustria#aph prussia#aph germany#ill stop here thanks-#hetalia headcanons

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

on the subject of decentralization/federalism, the italian city-states are often presented as evidence of the value of decentralization and competition....

and like i've said before, yeah i think there is some truth to this. there is good to be found in some decentralization and competition and whatnot.

and the italian city-states are perhaps the most excellent example of this.

but man, did they squander it. they were at the top of the game for those few centuries. but then they lost it all and ended up a bygone impoverished backwater. the were relatively late to the game of unification and state-formation. they were at the top and ended up at the bottom.

at a time when many other countries were beginning to form proto-states italy remained disunited and often violently opposed to each other. i think this was a detriment and hastened its downfall and they lose out to other more unified/centralized states like england and the low countries.

i can just easily imagine an alternative italian history where they go through a similar slow state-formation process like other european countries and this actually permits them to maintain some of their momentum, instead of it being squandered and dissipated.

if only one of their many "leagues" took on a more permanent political role. a kind of federalism or even a confederacy, which would have still permitted a great degree of local/regional autonomy but allowed some central government to protect and cultivate the common weal.

#the netherlands as part of the burgundian state is a great example of this#it basically lines up with the shift of power/wealth/cultural centers moving from italy to the north#and while the hre itself was rather weak#i'd say it incubated and nurtured a bunch of smaller but very strong proto-states#it was like a garden of gardens#and of course we can get into the factors of wages and technology and productivity and all that#these are all interrelated#but still i think some kind of union and state-formation would have saved the italian city-states

1 note

·

View note

Note

About Edward IV of England's previous marriage choices, I know Bona of France, Isabella of Spain, Mary/Jeanne of Burgundy ... Queen Mother of Scots ...? Where did these proposals finally go? Edward IV of England should be the most supportive of the marriage with Burgundy, but the good Philip disagreed?

Those talks mainly died because Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville. But before that, the french option through bona of Savoy was preferred because of Warwick's heavy-handed involvement in the negotiations. It's also possible that Philip the Good was reluctant to associate himself with an usurper whose control over England was frail.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I feel that one of the most overlooked aspects of studying the French Revolution is that, in 18th-century France, most people did not speak French. Yes, you read that correctly.

On 26 Prairial, Year II (14 June 1794), Abbé Henri Grégoire (1) stood before the Convention and delivered a report called The Report on the Necessity and Means of Annihilating Dialects and Universalising the Use of the French Language(2). This report, the culmination of a survey initiated four years earlier, sought to assess the state of languages in France. In 1790, Grégoire sent a 43-question survey to 49 informants across the departments, asking questions like: "Is the use of the French language universal in your area?" "Are one or more dialects spoken here?" and "What would be the religious and political impact of completely eradicating this dialect?"

The results were staggering. According to Grégoire's report:

“One can state without exaggeration that at least six million French people, especially in rural areas, do not know the national language; an equal number are more or less incapable of holding a sustained conversation; and, in the final analysis, those who speak it purely do not exceed three million; likely, even fewer write it correctly.” (3)

Considering that France’s population at the time was around 27 million, Grégoire’s assertion that 12 million people could barely hold a conversation in French is astonishing. This effectively meant that about 40% of the population couldn't communicate with the remaining 60%.

Now, it’s worth noting that Grégoire’s survey was heavily biased. His 49 informants (4) were educated men—clergy, lawyers, and doctors—likely sympathetic to his political views. Plus, the survey barely covered regions where dialects were close to standard French (the langue d’oïl areas) and focused heavily on the south and peripheral areas like Brittany, Flanders, and Alsace, where linguistic diversity was high.

Still, even if the numbers were inflated, the takeaway stands: a massive portion of France did not speak Standard French. “But surely,” you might ask, “they could understand each other somewhat, right? How different could those dialects really be?” Well, let’s put it this way: if Barère and Robespierre went to lunch and spoke in their regional dialects—Gascon and Picard, respectively—it wouldn’t be much of a conversation.

The linguistic make-up of France in 1790

The notion that barely anyone spoke French wasn’t new in the 1790s. The Ancien Régime had wrestled with it for centuries. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, issued in 1539, mandated the use of French in legal proceedings, banning Latin and various dialects. In the 17th and 18th centuries, numerous royal edicts enforced French in newly conquered provinces. The founding of the Académie Française in 1634 furthered this control, as the Académie aimed to standardise French, cementing its status as the kingdom's official language.

Despite these efforts, Grégoire tells us that 40% of the population could barely speak a word of French. So, if they didn’t speak French, what did they speak? Let’s take a look.

In 1790, the old provinces of the Ancien Régime were disbanded, and 83 departments named after mountains and rivers took their place. These 83 departments provide a good illustration of the incredibly diverse linguistic make-up of France.

Langue d’oïl dialects dominated the north and centre, spoken in 44 out of the 83 departments (53%). These included Picard, Norman, Champenois, Burgundian, and others—dialects sharing roots in Old French. In the south, however, the Occitan language group took over, with dialects like Languedocien, Provençal, Gascon, Limousin, and Auvergnat, making up 28 departments (34%).

Beyond these main groups, three departments in Brittany spoke Breton, a Celtic language (4%), while Alsatian and German dialects were prevalent along the eastern border (another 4%). Basque was spoken in Basses-Pyrénées, Catalan in Pyrénées-Orientales, and Corsican in the Corse department.

From a government’s perspective, this was a bit of a nightmare.

Why is linguistic diversity a governmental nightmare?

In one word: communication—or the lack of it. Try running a country when half of it doesn’t know what you’re saying.

Now, in more academic terms...

Standardising a language usually serves two main purposes: functional efficiency and national identity. Functional efficiency is self-evident. Just as with the adoption of the metric system, suppressing linguistic variation was supposed to make communication easier, reducing costly misunderstandings.

That being said, the Revolution, at first, tried to embrace linguistic diversity. After all, Standard French was, frankly, “the King’s French” and thus intrinsically elitist—available only to those who had the money to learn it. In January 1790, the deputy François-Joseph Bouchette proposed that the National Assembly publish decrees in every language spoken across France. His reasoning? “Thus, everyone will be free to read and write in the language they prefer.”

A lovely idea, but it didn’t last long. While they made some headway in translating important decrees, they soon realised that translating everything into every dialect was expensive. On top of that, finding translators for obscure dialects was its own nightmare. And so, the Republic’s brief flirtation with multilingualism was shut down rather unceremoniously.

Now, on to the more fascinating reason for linguistic standardisation: national identity.

Language and Nation

One of the major shifts during the French Revolution was in the concept of nationhood. Today, there are many ideas about what a nation is (personally, I lean towards Benedict Anderson’s definition of a nation as an “imagined community”), but definitions aside, what’s clear is that the Revolution brought a seismic change in the notion of French identity. Under the Ancien Régime, the French nation was defined as a collective that owed allegiance to the king: “One faith, one law, one king.” But after 1789, a nation became something you were meant to want to belong to. That was problematic.

Now, imagine being a peasant in the newly-created department of Vendée. (Hello, Jacques!) Between tending crops and trying to avoid trouble, Jacques hasn’t spent much time pondering his national identity. Vendéen? Well, that’s just a random name some guy in Paris gave his region. French? Unlikely—he has as much in common with Gascons as he does with the English. A subject of the King? He probably couldn’t name which king.

So, what’s left? Jacques is probably thinking about what is around him: family ties and language. It's no coincidence that the ‘brigands’ in the Vendée organised around their parishes— that’s where their identity lay.

The Revolutionary Government knew this. The monarchy had understood it too and managed to use Catholicism to legitimise their rule. The Republic didn't have such a luxury. As such, the revolutionary government found itself with the impossible task of convincing Jacques he was, in fact, French.

How to do that? Step one: ensure Jacques can actually understand them. How to accomplish that? Naturally, by teaching him.

Language Education during the Revolution

Under the Ancien Régime, education varied wildly by class, and literacy rates were abysmal. Most commoners received basic literacy from parish and Jesuit schools, while the wealthy enjoyed private tutors. In 1791, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand (5) presented a report on education to the Constituent Assembly (6), remarking:

“A striking peculiarity of the state from which we have freed ourselves is undoubtedly that the national language, which daily extends its conquests beyond France’s borders, remains inaccessible to so many of its inhabitants." (7)

He then proposed a solution:

“Primary schools will end this inequality: the language of the Constitution and laws will be taught to all; this multitude of corrupt dialects, the last vestige of feudalism, will be compelled to disappear: circumstances demand it." (8)

A sensible plan in theory, and it garnered support from various Assembly members, Condorcet chief among them (which is always a good sign).

But, France went to war with most of Europe in 1792, making linguistic diversity both inconvenient and dangerous. Paranoia grew daily, and ensuring the government’s communications were understood by every citizen became essential. The reverse, ensuring they could understand every citizen, was equally pressing. Since education required time and money—two things the First Republic didn’t have—repression quickly became Plan B.

The War on Patois

This repression of regional languages was driven by more than abstract notions of nation-building; it was a matter of survival. After all, if Jacques the peasant didn’t see himself as French and wasn’t loyal to those shadowy figures in Paris, who would he turn to? The local lord, who spoke his dialect and whose land his family had worked for generations.

Faced with internal and external threats, the revolutionary government viewed linguistic unity as essential to the Republic’s survival. From 1793 onwards, language policy became increasingly repressive, targeting regional dialects as symbols of counter-revolution and federalist resistance. Bertrand Barère spearheaded this campaign, famously saying:

“Federalism and superstition speak Breton; emigration and hatred of the Republic speak German; counter-revolution speaks Italian, and fanaticism speaks Basque. Let us break these instruments of harm and error... Among a free people, the language must be one and the same for all.”

This, combined with Grégoire’s report, led to the Décret du 8 Pluviôse 1794, which mandated French-speaking teachers in every rural commune of departments where Breton, Italian, Basque, and German were the main languages.

Did it work? Hardly. The idea of linguistic standardisation through education was sound in principle, but France was broke, and schools cost money. Spoiler alert: France wouldn’t have a free, secular, and compulsory education system until the 1880s.

What it did accomplish, however, was two centuries of stigmatising patois and their speakers...

Notes

(1) Abbe Henri Grégoire was a French Catholic priest, revolutionary, and politician who championed linguistic and social reforms, notably advocating for the eradication of regional dialects to establish French as the national language during the French Revolution.

(2) "Sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser l’usage de la langue francaise”

(3)On peut assurer sans exagération qu’au moins six millions de Français, sur-tout dans les campagnes, ignorent la langue nationale ; qu’un nombre égal est à-peu-près incapable de soutenir une conversation suivie ; qu’en dernier résultat, le nombre de ceux qui la parlent purement n’excède pas trois millions ; & probablement le nombre de ceux qui l’écrivent correctement est encore moindre.

(4) And, as someone who has done A LOT of statistics in my lifetime, 49 is not an appropriate sample size for a population of 27 million. At a confidence level of 95% and with a margin of error of 5%, he would need a sample size of 384 people. If he wanted to lower the margin of error at 3%, he would need 1,067. In this case, his margin of error is 14%.

That being said, this is a moot point anyway because the sampled population was not reflective of France, so the confidence level of the sample is much lower than 95%, which means the margin of error is much lower because we implicitly accept that his sample does not reflect the actual population.

(5) Yes. That Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand. It’s always him. He’s everywhere. If he hadn’t died in 1838, he’d probably still be part of Macron’s cabinet. Honestly, he’s probably haunting the Élysée as we speak — clearly the man cannot stay away from politics.

(6) For those new to the French Revolution and the First Republic, we usually refer to two legislative bodies, each with unique roles. The National Assembly (1789): formed by the Third Estate to tackle immediate social and economic issues. It later became the Constituent Assembly, drafting the 1791 Constitution and establishing a constitutional monarchy.

(7) Une singularité frappante de l'état dont nous sommes affranchis est sans doute que la langue nationale, qui chaque jour étendait ses conquêtes au-delà des limites de la France, soit restée au milieu de nous inaccessible à un si grand nombre de ses habitants.

(8) Les écoles primaires mettront fin à cette étrange inégalité : la langue de la Constitution et des lois y sera enseignée à tous ; et cette foule de dialectes corrompus, dernier reste de la féodalité, sera contraint de disparaître : la force des choses le commande

(9) Le fédéralisme et la superstition parlent bas-breton; l’émigration et la haine de la République parlent allemand; la contre révolution parle italien et le fanatisme parle basque. Brisons ces instruments de dommage et d’erreur. .. . La monarchie avait des raisons de ressembler a la tour de Babel; dans la démocratie, laisser les citoyens ignorants de la langue nationale, incapables de contréler le pouvoir, cest trahir la patrie, c'est méconnaitre les bienfaits de l'imprimerie, chaque imprimeur étant un instituteur de langue et de législation. . . . Chez un peuple libre la langue doit étre une et la méme pour tous.

(10) Patois means regional dialect in French.

#frev#french revolution#cps#mapping the cps#robespierre#bertrand barere#language diversity#amateurvoltaire's essay ramblings

772 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Literally why isn't is partitioned by France and Germany."

To be fair, the House of Valois-Burgundy and the House of Hapsburg both tried really, really hard to do just that. It didn't work, because Swiss pikemen were both almost impossible to break on the defensive when they formed square, and were terrifyingly aggressive in columns where they were fast enough to pull off foot charges against cavalry, and simply would not stop charging no matter how many casualties they absorbed, as long as they could actually come to grips with their opponents.

It is entirely possible that, had a few battles gone the other way, that Milan would be Swiss today.

I think Switzerland might have the highest "people act like it's a real country":"is actually a real country" ratio. Extremely fake country. Literally why isn't is partitioned by France and Germany. Who gives a fuck. They have their own currency. It's asinine

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Young Girl Bathing

Artist: Attributed to Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (French, 1758 - 1823)

Date: 1782

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA, United States

Information

Few works from the earliest period of Pierre-Paul Prud'hon's career have survived, making it difficult to attribute this painting on stylistic grounds. Although the signature and date at lower left were partially effaced when the painting was cleaned, photographs made in the early twentieth century show that the canvas once bore the date 1782. This was the same year that the young and ambitious artist first went to Paris from his native Dijon, and this date, if accurate, would make the work one of the earliest known paintings by Prud'hon. While in Paris, Prud'hon lodged with the Fauconniers, a family of fellow Burgundians. A member of this family owned this painting as late as 1874. In addition to the circumstantial evidence for an attribution to Prud'hon provided by this provenance, the work resembles in some of its details, such as the draperies, certain drawings Prud'hon made in this early period of his career. As a mature artist, Prud'hon became known for his idiosyncratic and proto-romantic interpretation of the then-fashionable neoclassicism and for his extensive work for the Napoleonic court.

#painting#female figure#genre art#bathing#forest#trees#stream#nude female#oil on canvas#fine art#textiles#bathing nymph#fantasy#french culture#pierre paul prud'hon#french painter#french art#oil painting#artwork#european art#18th century art#the huntington art museum#18th century painting

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Ballock Dagger, XVth century.

Inspired by various models popular in the northern parts of the powerful Burgundian states.

Blade is high carbon steel, with an elegant hollow grind and decorative false edge. Grip is cherry wood, with brass plate and end. Carved and tooled vegetable tanned leather scabbard, and mild steel chape.

As always, everything is hand made.

There is an obvious anatomical analogy in the shape of these daggers, probably associated to some symbolism and nonverbal forms of communication that elude us, but which certainly explains their popularity from the XIVth century onwards.

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

The chapel on the left of the altar of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Zavelkerk in Brussels belonging to the Thurn und Taxis family.

Saint Ursula Chapel, a unique Italian Baroque style chapel in black Belgian marble and white Carrara marble, was built according to a design by Lucas Fayd'herbe (1617-1697). The sculptures are by various southern Netherlandish sculptors. The restored Caritas statue made by Jan van Delen was recently placed back. The statue was confiscated by French revolutionaries in 1795 and therefore returned after more than 200 years.

The von Thurn und Taxis family initiated international postal traffic in Europe. A German descendant is today known as the richest man in his thirties and the largest private landowner in Europe with 28,000 hectares. The powerful 'DHL predecessors' von Thurn und Taxis had the chapels added to the church in the second half of the seventeenth century.

Von Thurn und Taxis (also Thurn and Tassis in Dutch) is a German noble family of Italian origin that acquired great wealth through its activities in the postal system. The current monarch, Albert II von Thurn und Taxis, resides in the Fürstliches Schloss of Regensburg. For two centuries the family was based in Brussels, where they owned a city palace (ca. 1500-1700). The still existing site of Thurn and Taxis was at the time the grazing land for the post horses.

The patriarch of the postal dynasty was Omodeo Tasso, the first family member to be located in Cornello dei Tasso. At the end of the 13th century, he and 32 relatives organized the Compagnia dei Corrieri, a courier company that worked on behalf of the Serenissima (Venice). She provided foot connections between Venice, Milan and Rome, Genoa,... The Bergamots had always occupied a major place in the old Venetian postal service (couriers were called bergamaschi in Italy). At the end of the 15th century they organized themselves into the Compagnia dei Corrieri dei Roma, a company controlled by the Tasso family.

Other members of the family were called to the Papal States to take care of the papal post. They did this from 1460 to 1539. It was two brothers from another branch who eventually took the business to a European level: Janetto and Francesco. As head of the family (procuratore generale della famiglia e società di Tassi), Janetto entered into a contract with Emperor Maximilian I to set up a truly transnational post (1489-90). He had to connect the emperor's headquarters in Innsbruck with Italy, the Burgundian Netherlands (Mechelen) and France. Janetto was given the title Kuriermeister and called on his brother Francesco and his cousin Giovanni Battista. Under the leadership of the trio, an innovative relay service was created that allowed messages to travel at a speed never before seen in Europe. Thanks to a succession of stopping places along the routes, it was possible to constantly change horses and riders. Only the leather mailbag ("Felleisen") was constantly in motion.

Francesco settled in the Netherlands around 1500, after his brother David had prepared the way. Under Maximilian's son Philip the Fair, he became postmaster and captain and had a beautiful city palace built in Brussels. After the government of Spain de facto fell to Philip, he renewed his agreement with Francesco of Tassis. The new postal contract of January 18, 1505 included more destinations and, for the first time, binding order deadlines (extended in winter). The postmaster guaranteed strict compliance with his life. A star-shaped network of postal routes departed from Brussels: to Innsbruck, to Paris-Blois-Lyon, to Toledo-Granada. For the important route to Spain, an alternative was provided via the Alps and the sea in the event of war with France.

#architecture#europe#historic buildings#historical#architectural history#belgium#history#historical interior#art history#sculptor#sculpture#scultura#sculptures#arte#artwork#art style#baroque#barok#baroque art#baroque architecture#brussels#brussel#bruxelles#bruselas#postal#post#mail#courier#postal service#chapel

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why George Russell's Disqualification is Really Napoleon's Fault

Alright motorsports fans, with the end of the Belgian Grand Prix (held before the summer break this year because the F1 calendar is becoming increasingly cursed year after year) F1 enters its summer break. NASCAR and Indycar are on an Olympic break thanks to both series currently being on NBC (who is the US broadcaster of the 2024 Paris Olympics), and MotoGP doesn't come back from its second summer break until next week.

So what the hell am I going to talk about in this blog.

Well, George Russell won the 2024 Belgian Grand Prix until he got disqualified for having an underweight car. Some people have theorized that Mercedes made a mistake and underfueled him, others have said that George switching to a one-stop meant he lost out of valuable pitlane speed time, using up more fuel, still others have theorized it's down to the unique procedures at Spa - where drivers turn around after turn one and drive the wrong way into pit exit - that meant Russell didn't have the chance to pick up rubber and thus increase the weight of his tyres.

I, meanwhile, have a different theory.

George Russell could only have been disqualified from the Belgian Grand Prix because of Napoleon!

Yes, really.

How, you may ask? Well, the Napoleonic Wars created the conditions that ultimately allowed for the the Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps to exist. Thus, the long lap that causes F1 cars to deliberately underfuel for the race, the unique post-race procedures due to track length, and choice of this area as the venue for the Belgian Grand Prix...none of that would've been possible with Napoleon.

Our story, as all good motor racing stories do, begins in 651 when the Benedictine Monk, Saint Remaclus of Stavelot founded the dual Abbeys of Stavelot and Malmedy (which you may recognize from corner names of the Spa-Francorchamps circuit, as these are neighboring villages).

These abbeys wound gain more territory in 747 when Carloman, the Majordomo of the Franks and uncle of Charlemagne, abdicated and became a monk himself.

They would be enlarged again in 882 by Charles the Fat, Holy Roman Emperor, in compensation for the Normans raiding and burning down both abbeys the previous year.

Thus, the Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy became one of the many mosaic pieces of the complex historical mindscrew that is the Holy Roman Empire, holding territories along what is now the Belgian-Germany border. Back then though, they were a rather significant ecclesiastical territory, holding land where Lothringia met the Low Countries.

This was the exact region where, in the late 15th and early 16th century, the Dukes of Burgundy attempted to create their own sovereign territory, using the chaos of the Hundred Years War in France to become lords over Luxembourg, Hainaut, Flanders, Brabant, and Holland. Soon enough, the Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy was one of only three independent states remaining in the region.

It was Stavelot-Malmedy, an ecclesiastical state which thus couldn't easily be absorbed into secular Burgundy.

Then the Prince-Bishopric of Liege, which again, was an ecclesiastical state which meant it would be a tricky proposition for a Catholic Duke of Burgundy to try and conquer.

And finally the Duchy of Bouillon, which was a downright weird state in that the title was a secular Duchy that was sold to the Prince-Bishopric of Liege, and in the late 17th century became a sovereign possession of the La Tour d'Auvergne, a French noble family.

In any case, upon the death of the Burgundian line, their territories were divided between France, the feudal overlord of Burgundy, and Philip the Handsome (the son of Mary the Rich, the last Duchess of Burgundy, and Maximilian von Habsburg, an Austrian Prince).

Philip the Handsome was in turn married to Joanna the Mad (we should bring back the random ass nicknames people used to get in the past btw), the Queen of Castile and Aragon. Their son, Charles, would thus inherit Spain, the Burgundian possessions in the Low Countries, and, eventually, Austria and the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Yeah.

So thanks to Charles V rolling a natural 20 in his birth dice roll, Stavelot-Malmedy was suddenly one small little ecclesiastical holding squeezed between the two halves of what would eventually become known as the Spanish Netherlands.

Then, the northern half of the Spanish Netherlands decided they didn't want to be Catholic anymore. This ushered in the Dutch Revolt of the 17th century, a bloody religious struggle concurrent with the Thirty Years War and the Portuguese War of Independence that marked the end of the golden age of Spanish power.

Come 1700 and Charles II of Spain (Charles V was Charles I in Spain, regnal numbers get weird when you rule over half of Europe), the last Habsburg King of Spain, dies an inbred and infertile mess. The Low Countries become a battleground in the War of the Spanish Succession.

On one side, France and Spain, as Charles II had declared his grandnephew, the French Prince Philip of Anjou, threatened to tip the scales of western Europe towards the Bourbon dynasty.

On the other side, a grand coalition of Austria, England, the Dutch Republic, Prussia, Portugal, and Savoy aimed to contain French power.

This was the War of the Spanish Succession, and the war would be transformative for the southern Low Countries. The Spanish Netherlands went back to Habsburg hands and became the Austrian Netherlands, meanwhile, the Duchy of Cleves, just to the east, was returned to Prussia following a French occupation.

The Dutch Republic in the north was Protestant, the Austrian Netherlands were Catholic, and Protestant Prussia was emerging on the scene as well. This would more or less lay the stage for the Napoleonic Wars, where the armies of the French Republic and later the French Empire would occupy all of this land. Gone were the Austrian Netherlands, gone was Stavelot-Malmedy, Liege, and Bouillon, and gone was Prussian Cleves.

Instead, the land surrounding Spa-Francorchamps would became part of the French Department of Ourthe, named for one of the principal rivers of the region.

However, much like the War of the Spanish Succession, numerous grand coalitions would rise up against Napoleon, the primary participants being Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, the Dutch, and Russia. In 1815, they would finally defeat Napoleon once and for all, and the Peace of Vienna would shape the new postwar Europe.

Of the old Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy, Stavelot would go to the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (the new kingdom combining the modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg), while Malmedy would go to the Kingdom of Prussia.

The border would be a minor tributary of the River Ambieve known for its reddish water. The name? Eau Rouge.

Fast forward to 1830 and the largely Catholic southern Netherlands revolt from their Protestant overlords in the north and demand the creation of a Kingdom of Belgium. Following a great power conference in London, the Belgians would get their wish, and in 1831, the Kingdom of Belgium was born, including Stavelot.

The Dutch would recognize Belgium Independence in 1839.

Eau Rouge was now the Belgian-Prussian border.

Come 1871, and Prussia becomes the German Empire.

Come 1914, and this border region is amongst the first overrun by the Germans in World War I. Spa becomes a major German field hospital from the get-go, and by 1918, Spa is the German military headquarters and the primary residence of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Upon the German surrender in 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm would abdicate and leave for the Netherlands, meanwhile, France and Belgium - the countries that wore the greatest scars from World War I - would demand harsh reparations from Germany. For Belgium, this would include Eupen-Malmedy.

Thus, the great majority of the old Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy was now within Belgian borders.

Jules de Thier, owner of the La Meuse newspaper in Liege, found this new territory to be the perfect site for a high-speed triangular race track in 1921. The race would begin in old Belgium, with a run to the old border - originally they would veer right, pass through Ancienne Douane - the old customs office on the Belgian-Prussian border - then back left to rejoin the track on the other side of what is now the Eau Rouge corner - then run through the German territories.

Burnenville and Malmedy were in old Germany, then swing back at the bottom of the track, crossing back into pre-war Belgian territory in time for the Masta kink, then Stavelot, Blanchimont, and La Source would all be in pre-war Belgium as well. Cross the start-finish line after La Source (as it was back then) and then cross into former Germany again on the next lap.

Thus, the Belgian Grand Prix was born in a region that had only just been annexed from Germany.

This led to Spa again becoming a battlefield during World War II, but with the borders restored after the war, Spa would again be in Belgium and, from 1950, the Belgian Grand Prix would become a traditional staple on the Formula One calendar.

Spa-Francorchamps would be transformed a couple of times over, not assuming its current form until 2007, but it was born from the great Napoleonic shakeup in European politics.

The ancient double abbeys of Stavelot-Malmedy were separated for the first time in 1200 years, and it would take another century for them to be reunited in modern Belgium.

So yeah, if you're mad that George Russell was disqualified, blame Napoleon...or Kaiser Wilhelm II I suppose, whichever one fits your fancy.

Oh, and by the way, Lewis Hamilton takes a record-extending 105th win following his teammate's disqualification, so I suppose Mercedes still has something to be happy about.

#motorsports#racing#f1#formula 1#formula one#yeah this is just a self-indulgent blog from a history major#no one is gonna care about this blog but I had fun writing it#spa francorchamps#belgian gp 2024#belgian grand prix

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The turbulent life and political career of Isabeau of Bavaria provides much material through which to approach a theme of queenship, reputation, and gendered power. Isabeau held an unprecedented position for a queen of France because of the extraordinary circumstances following the first attack of insanity suffered by her husband, Charles VI, in August 1392, and his subsequent descent into a distressing and debilitating state of mental illness. Isabeau was faced with political intrigues, assassinations, and acts of vengeance among the royal families of France that spiraled into civil war [...]. After the deaths of two of her sons in their teenage years from infections, Isabeau herself suffered a humiliating period of captivity at the hands of the Armagnacs in 1417, isolation politically from her last remaining son and, finally, by what one might call the most important victory of Henry V—when he negotiated an alliance with the Burgundians that would lead to the negotiation of the Treaty of Troyes.

[…] The 1402 ordinance had been a first attempt by a temporarily recovered Charles VI to break the cycle of feuding, by raising his queen as an independent force between the dukes of Burgundy and Orleans, while that of April 1403 sought to neutralize further the dukes’ potential for unlicensed absolutism through the check of quasi-majority rule. The collegiate administration was intended to prevent any one prince being able to intimidate his way to supremacy by keeping power and responsibility divided up as much as possible—as did the mere act of including the queen.

The sovereign status of Isabeau of Bavaria trumped any claims for preeminence based on seniority or blood relationship that might be pursued by the dukes, while she herself was not a force that could imperil the king. Her rank and position as queen gave her power, but that (quite clearly) was inextricably dependent on her relationship with the king and one might argue that this made her above all others more neutral, with no agenda of her own. As the king’s wife and the legal guardian of his heir, she was the most entitled to act as a proxy yet, unlike the rest of the royal family, could never be a successor herself; so she was no threat. A queen has power (the capacity to persuade people to act or make things happen) but no royal authority of her own, no publicly recognized right to rule. If authority was granted or sanctioned by the king, and recognized by his peers, a queen held it and it was legitimate, as was the case for Isabeau for most of her reign. The provisions establishing the queen as head (présidente) of the Regency Council set her into a position of substantial authority and great vulnerability. While being appealed to, buffeted and threatened by both sides in an increasingly acrimonious civil war, Isabeau was careful always to claim intermediary status for her acts, as the representative and deputy of her husband’s authority—and she needed to do so. By sheer definition, the role of queen consort was as a subordinate to the king and Isabeau had to maintain the perception that she was acting only in support of her husband, not as an independent political being with her own agenda. However, Charles VI’s selection of Isabeau as head of the Regency Council, ruling in the king’s stead in his periods of illness with all the powers of a lieutenant-general appointed in short periods of absence for war, demonstrates that the office of queen was not regarded as peripheral to monarchy, but an integral part of it that could be utilized when necessary in the service of the Crown as a corporate entity and invested by the king with the authority of kingship.

The queen’s authority would be tested to the full over the twenty years following the outbreak of the king’s madness in 1392, and first shared with, then gradually yielded to, her eldest son, the dauphin Louis, as he grew toward maturity, both in years and in diplomatic capability. As soon as it was legally possible, in the days before his thirteenth birthday, Isabeau organized Louis’s emancipation (his legal majority). Although Isabeau tended to retain chairmanship of the regency council, there were occasions after 1410 when she might easily have attended but chose not to, thereby pushing forward her son into the limelight as next in line after her as the king’s deputy. The dauphin Louis represented the king during the preliminary negotiations at Arras in September 1414, and at the later meetings at Saint-Denis and Paris in February 1415 that led to the eventual truce between the warring Burgundian and Orleanist/Armagnac factions. In fact, the phrase recorded by Michel Pintoin, the Religieux de Saint-Denis, in his account of the peace of Arras describes Louis’s role perfectly as the one “who held the reins of the State during his father’s illness."

However, the end of 1415 witnessed two disasters for France, with the desolation of the battle of Agincourt in October and the sudden death of the dauphin Louis in December. Grieving and politically isolated, Isabeau of Bavaria would spend the remainder of her life, another long 20 years, as subsumed and powerless as the rest of the country in the disaster of division and conquest. She was imprisoned by the Armagnac faction in 1417, who issued an ordinance establishing her last remaining son, the future Charles VII, as the king’s deputy instead. It is an interesting coda to this discussion of the regency provisions to consider their later misuse as well. Although Isabeau was in no position to exert power herself in 1417, the ordinance of April 1403 naming her as the king’s deputy in periods of emergency Council-run government seems only to have been replicated (not revoked) when the dauphin was granted his title. By arguing that the grant of powers to Isabeau in 1403 was irrevocable, as Burgundy would claim when releasing her from captivity in 1418, it was worth his while to fund her and establish her as the figurehead of a rival regime, seeking to regain possession of the person of the king. Isabeau of Bavaria found herself in an unenviable situation, with no financial backup of her own, no power base, and absolutely no prospect of being able to take back government herself. In such a scenario, control of the queen and her authority, by neutralizing her in prison like Armagnac or, like Burgundy, by persuasion or coercion, or perhaps even deceptive use of her titles and seals with no attempt or interest in gaining her consent or not, remained the ultimate weapon in the civil war. Regency authority somehow endured, despite the essential powerlessness personally of the individual regent queen."

— Rachel C. Gibbons, "Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France: Queenship and Political Authority as “Lieutenante-Général” of the Realm", Queenship, Gender, and Reputation in the Medieval and Early Modern West, 1060–1600 (Edited by Zita Eva Rohr and Lisa Benz)

#isabeau of bavaria#french history#queenship tag#historicwomendaily#women in history#15th century#hundred years war#charles VI#my post#not sure if i should tag henry v or Charles vii

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Philip II of Spain (1527-1598), Bust in Spanish Court Dress with the Order of the Golden Fleece

Artist: Alonso Sanchez Coello (Spanish, 1531/1532-1588)

Date: c. 1568

Medium: Oil painting

Collection: Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria

Description

Alonso Sánchez Coello, a student of Anthony Mors, was first court painter to John III of Portugal, then to Philip II of Spain. This bust of the king is a variant of a portrait in the Prado in Madrid, also attributed to Sánchez, in which the sitter's hands can also be seen. Philip II is wearing Spanish court dress with the Order of the Golden Fleece, the symbol of the knightly order of the same name that the Habsburgs had adopted from the Burgundians. Philip II, known as "El Prudente" (= the Wise), was born in 1527 as the son of Emperor Charles V and Isabella of Portugal. In 1556 he became King of Spain. His reign brought Spain's supremacy within the European states. Philip II also suffered some major defeats: in 1579/81 the northern provinces of the Netherlands were lost, and in 1588 the Spanish Armada was defeated by England. This was offset by the acquisition of Portugal and its large colonial empire. The greatest victory of the century, however, was the destruction of the Turkish fleet at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 under the leadership of Don Juan de Austria, a half-brother of King Philip. His four marriages to Mary of Portugal, Mary Tudor, Isabella of Valois and Archduchess Anne were in line with political goals. Philip II's conscientiousness and absolute self-control were both admired and feared.

#portrait#painting#bust painting#fine art#philip ii of spain#spanish court dress#order of the golden fleece#symbol#knightly order#spanish history#spanish monarchy#oil painting#alfonso sanchez coello#spanish painter#spanish culture#16th century painting#spanish art#artwork#european art

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

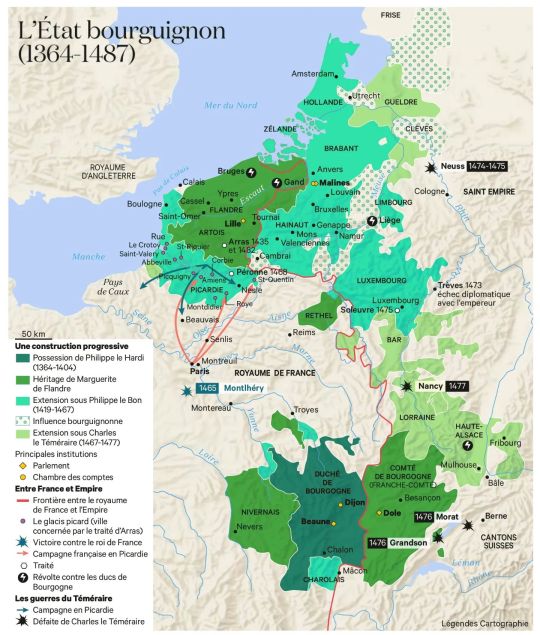

The Burgundian state, 1364-1487.

« Atlas historique mondial », Christian Grataloup, Les Arènes/L'Histoire, 2e éd., 2023

by cartesdhistoire

In 1363, the king of France, John the Good, gave Burgundy as an appanage to his son Philippe the Bold. Duke until 1404, he became master of a vast area, including Charolais, Artois, Franche-Comté, Rethel, Nevers and Brabant. His power made Flanders independent and it was a solid base for expansion in the Empire, continued by Duke Philip the Good (1419-1467): Namur, Hainaut, Holland, Zeeland and Luxembourg ( in addition to a nebula of satellites like the ecclesiastical principalities of Liège, Utrecht and even Cologne).

The Burgundian “State” is therefore made up of two blocks of territories, both shared between France and the Empire: Burgundy (France) and Franche-Comté (Empire) are governed from Dijon; from Lille then from Brussels from 1430, Flanders, Artois (France) and the Netherlands (Empire). The frequent meeting of States within the framework of each province allows regular taxation, which makes the Duke one of the richest sovereigns in the West, the bulk of his income coming from Flanders and the Netherlands. The administrative structure is close to that of the French monarchy (aids, Chambers of Accounts, states, Parliament).

Duke Charles the Bold (1467-1477) tried to reunite the two blocks, barely 60 km apart after 1441. He centralized, increased taxes and borrowed enormous sums from banks to obtain an imposing army and artillery. He then aimed for Lorraine and the archbishopric of Cologne but his ambitions united his enemies against him: Louis XI, the emperor, Lorraine, Savoy and the Swiss. In 1475, the Swiss crushed Charles's army at Grandson and Morat then the duke died in 1477, trying to retake Nancy. He is succeeded by his daughter Marie who married Maximilien, son of the emperor. She died on March 27, 1482 and on December 23, the Treaty of Arras divided her inheritance between Valois and Habsburg.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 30

One thing you’d change about the Nibelungenlied

This is a minor thing, but I would change the name of Dankrât, the father of Kriemhild and her brothers (who is only mentioned once or twice in the Nibelugenlied). Everywhere else he’s called Gibich/Gybich/Gibica/Gjuki etc. With his children’s names being Gunther, Gernot, Giselher and Kriemhild/Grimhild – there is obviously a tradition in the family of alliterating names to G (which corresponds to the names of the historical Burgundian kings). The Nibelungenlied poet cannot simply break with this tradition like that! xD

The commentary of one of my Nibelungenlied editions (Deutscher Klassiker Verlag) states, that it's not clear, according to research, why the poet replaced the name (the name Gibeche is reintroduced in the manuscript k of the Nibelungenlied). I personally assume the name Dankrât might have been a reference to a patron or some figure in the poet’s environment.

But I will never accept it as my personal canon! xD

There is even a person named Gibeche in the Nibelungenlied, but he’s just some random knight at Etzel’s court.

Challenge over!

Thank you so much @haljathefangirlcat for creating the Nibelungen challenge all those years ago, it was a lot of fun to participate! And thank you, @galarix and @haljathefangirlcat for all your comments – it's been a lot of fun to converse with you so much about the Nibelungenlied! 😊

#30 days nibelungen challenge#nibelungenlied#so glad lili vogel used the name gibech in her kvb books

9 notes

·

View notes