#histoire de France

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#henri grobet#art#histoire de france#french#france#history#flags#europe#european#medieval#middle ages#napoleonic#franks#frankish#gauls#gallic#charlemagne#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#louis xiv#francis i#vercingetorix#saint louis#philip augustus#louis xi#mediaeval

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Going further with my undertale au because i literally have no remorse and no dignity left

Talleyrand is sans, napoleon is frisk and lannes is undyne and if what i said doesnt make any sense, im on my way to make this au more confusing (actually i have an explanation for every choice i made with these people lmfao I SWEAR)

#history#19th century history#historical figures#history art#histoire de france#early 19th century#historical art#history fanart#history fandom#xix century#histoire#historical au#undertale#undertale art#undertale au#jean lannes#marshal lannes#talleyrand#napoleon bonaparte#napoleon#frisk#frisk undertale#sans#sans undertale#undyne#undyne undertale

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marion from the manga "Natsu e no Tobira" or "The Doorway to Summer" (1975) by Keiko Takemiya

#marion#sara veeda#ledania#natsu e no tobira#the doorway to summer#keiko takemiya#takemiya keiko#year 24 group#belle epoque#france#french history#histoire française#histoire de france

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇨🇵 25 Août 1944 🇨🇵Libération de Paris🗼

" ...Paris martyrisé, mais Paris libéré..."

Général de Gaulle

#gif animé#gifer#libération de paris#25 août 1944#histoire#quotes#général de gaulle#histoire de france#paris#fidjie fidjie

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

France Feodale a l'avenement de Hugues Capet.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Il est interdit d'interdire !"

En revisionnant la série, je note de nouveaux petits détails qui m'avaient échappés.

Comme cette phrase prononcée par Chat Noir dans l'épisode Sangsure (saison 4) :

"IL EST INTERDIT D'INTERDIRE".

Cette boutade prononcée à l'origine par l'humoriste Jean Yanne est devenue l'un des slogans les plus marquants des évènements de Mai 68.

Mais qu'est-ce que c'est, Mai 68 ?

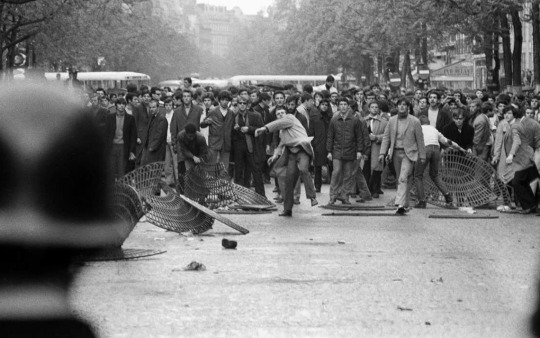

Ce mouvement de révolte sans précédent aux allures de révolution a éclaté en France en mai-juin 1968 dans les universités.

Le contexte : la France sort tout juste des Trente Glorieuses, une période de forte croissance économique et d'amélioration du niveau de vie qu’a connue la grande majorité des pays développés entre 1945 et 1975. Malgré tout, tout le monde ne profite pas de cette croissance économique : 2 millions de travailleurs en France sont payés au SMIG ("Salaire minimum interprofessionnel garanti", remplacé par le "salaire minimum interprofessionnel de croissance" (SMIC) en 1970), et le pays compte 500 000 chômeurs. Les travailleurs s'inquiètent pour leurs conditions de travail, et côté étudiant, la massification de l'enseignement supérieur cause d'innombrables problèmes (locaux peu adaptés à cette croissance rapide, manque de matériel, problèmes de transports...).

Au centre de Paris, la révolution gronde. Les étudiants s'inquiètent pour leur avenir. Des débats, des prises de paroles et des assemblées générales ont lieu dans les rues, les entreprises, les administrations et les universités.

Lorsque la police lance une intervention brutale le 3 mai 1968 pour disperser un meeting de protestation tenu par les étudiants dans la cour de la Sorbonne, la riposte est instantanée : de violents affrontements ont lieu dans les rues du Quartier latin, le point culminant étant atteint lors de la nuit désormais symbolique du 10-11 mai 1968 où les combats de rues ont donné lieu à bon nombres d'interpellations et a même fait plusieurs de victimes.

S'en suit la plus importante grève générale sauvage de l'histoire le 13 mai 1968 : la révolution étudiante s'est muée en crise sociale, et une vague de grèves s'enclenche. Le mouvement s'étend, et la France se retrouve totalement paralysée pendant des semaines.

Il y a encore énormément de choses à dire sur cette période qui a révolutionné l'histoire, je ne suis pas forcément la meilleure personne pour aborder le sujet.

Toujours est-il que Mai 68 reste à ce jour le plus important mouvement social de l'histoire de France du XXe siècle : en quelques semaines à peine, la France a fait bouger ses limites au delà de tout ce qui semblait possible. Et malgré l'échec apparent du mouvement de Mai 68, ses retombées sont énormes : cette crise a largement contribué à la modernisation de la société française. Ne serait-ce que pour les jeunes, les femmes, et les ouvriers qui ont réclamé et ont eu plus de pouvoir, plus de parole, plus de liberté. Bon nombre de leurs rêves sont devenus notre quotidien.

#miraculous ladybug#miraculous#adrien agreste#chat noir#ladybug#marinette dupain cheng#mai 68#un peu d'histoire#il est interdit d'interdire#ml analysis#ml thoughts#miraculous floconfettis#history#french history#histoire de france

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The ideological climate of the defeat of 1940 and the establishment of the French State are related in many aspects to the climate that developed in reaction to Sedan and during the years that followed the defeat of the Paris Commune. For writers close to the National Revolution, the Commune was viewed in the same way as the Popular Front. A propaganda journal published by the new regime stated:

It is a constant law of history that defeats result in revolutions. The French had not forgotten the bloody disturbances of the commune of 1871… . France was going to add even more misfortune to those that already overwhelmed it. It was to be feared that, following the bent to which odious propaganda had accustomed them, minds would turn toward a bloody, fratricidal fight. . . . The Marshal’s government successfully confronted and dealt with this danger. Without any-movement, without one cry of dissension, the political revolution was brought about.

Henri Massis, the officer responsible for press relations to General Huntziger at the time, stated plainly that the first news of the armistice had evoked the memory of 1871 and the fear of a new Commune. Thus, the primary task of the armistice army was to maintain order. The defeat would appear to many intellectuals as the final blow to 'French decadence.’ The themes of national decline, collective fault, and biological and political sins echoed one another in an obsessive litany during the period following June 1940, just as during the 1870s. Maurras even suggested anthologizing Renan’s La Reforme intellectuelle et morale, which he felt might render “a great service to the French people of 1940, since those of 1870 failed to take proper note of it.” The precepts and maxims of the Marshal—the “guide in possession of incomparable and almost superhuman wisdom and intellectual control” — functioned like calls to self-flagellation, and many would lend their skills to an attempt at exegesis. Georges Bernanos offered a gripping expression of the political bases and effects of the encounter between the message of the defeat, spoken by the prophet, and the “expectation” of those who saw the National Revolution as a national opportunity:

All that is called the Right, which ranges from the self-styled monarchists of the Action francaise to the self-styled national socialist radicals and includes big industry, big business, the high clergy, the Academies, and the officers’ staff spontaneously united and cohered around the disaster of my country like a swarm of bees around their queen. I am not saying that they deliberately wished the disaster. They were waiting for it. This monstrous anticipation passes judgment on them.

- Francine Muel-Dreyfus, Vichy and the Eternal Feminine: A Contribution to a Political Sociology of Gender. Translated by Kathleen A. Johnson. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001. p. 15-16.

#révolution nationale#régime de vichy#vichy france#reactionary politics#paris commune#action francaise#marshal pétain#georges bernanos#renan#occupied france#world war ii#academic quote#histoire de france#reading 2024#disaster politics#popular front#front populaire

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Mémoires de Louise Michel : Un ouvrage essentiel pour comprendre l'histoire du mouvement ouvrier et du féminisme.

#louise michel#Mémoires de Louise Michel#la commune de paris#histoire de france#révolution#anarchisme#féminisme

1 note

·

View note

Note

la culture française c'est avoir une passion sans bornes pour Versailles et arriver sur tumblr pour trouver genre deux personnes qui ont lu les Colombes du Roi-Soleil dont une qui se souvient plus de l'intrigue

.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoléon, Ridley Scott, 2023

Comme je suis assez nul en Histoire, ça m'a fait une leçon de rattrapage. Je me rends doucement compte que la période de la Révolution Française est quand même très compliquée à comprendre.

Le film quant à lui est décevant de la part de Ridley Scott. Le souffle épique ne fonctionne pas sur les batailles. Il ne se dégage presqu'aucune émotion d'aucun personnage, si ce n'est peut-être Joséphine. Après, l'histoire est en fait très triste. Après quelques victoires militaires, la vie de Napoléon est une succession de sacrifices qui mèneront à pas grand chose.

★✰✰✰✰

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quand j'étais en Terminale, mon prof d'histoire était fréquemment absent. Je ne sais même plus son nom. Je me souviens surtout que nous n'avons pas eu d'histoire géo pendant un bon moment et quand nous avons enfin eu un remplaçant, il a été effaré de voir le retard accumulé dans le programme, l'année du bac. On n'a jamais fini le programme.

Bref me voilà en train de regarder un documentaire sur Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, parce que j'ai l'impression de ne pas assez bien connaître l'histoire de mon propre pays au 20ème siècle. Si vous avez MyCanal, c'est sur Toute l'histoire, et ça s'appelle "VGE, le théâtre du pouvoir".

youtube

#valéry giscard d'estaing#vge#françois mitterrand#politique française#french politics#french history#histoire de france#politics#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-François Blondel

Ces cathédrales aux mystérieux rayons de lumière Lorsque Jean-François Blondel a constaté le rai de lumière dans la Cathédrale de Chartres, le jour du solstice d’été, il décide d’en savoir plus. L’essai Ces Cathédrales aux mystérieux rayons de lumière est né de ses recherches. Jean-François Blondel croit que les bâtisseurs du Moyen-Âge ont attiré l’attention en mettant en place ce détail…

View On WordPress

#art#Billet littéraire#Chronique littéraire#Chronique livre#Chroniques littéraires#france#histoire#Histoire de France#Histoire de l&039;art#Histoire de Paris#Littérature contemporaine#littérature française#Littérature francaise#Litterature contemporaine#Moyen-Age#Visite

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

J'ai fini la bande dessinée 'Carnets d'Algérie' de Jacques Ferrandez. Je vous la conseille vivement ! C'est vraiment une pépite. L'histoire est inspirée de faits réels même si les personnages principaux sont totalement fictifs. De plus, elle contient des documents historiques sur la guerre d'Algérie, cela permet de venir préciser certains points sur cette guerre. C'est une BD importante qui mérite vraiment plus de visibilité !

#bande dessinée#comics#lecture#livre#booklr#book recommendations#books#history#histoire#histoire de france

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[…] trahi, fait prisonnier, affreusement torturé par un ennemi sans honneur, Jean Moulin mourrait pour la France, comme tant de bons soldats qui, sous le soleil ou dans l'ombre, sacrifièrent un long soir vide pour mieux « remplir leur matin ».

Charles de Gaulle

#gif animé#8 mai 1945#armistice#résistance#jean moulin#quotes#charles de gaulle#histoire de france#hommage#8 mai#fidjie fidjie

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Godefroy de Bouillon

Le matin se levait sur Bouillon, enveloppant le château d'une brume légère qui se dissipait lentement sous les premiers rayons du soleil. Les murs de pierre, témoins de tant d'histoires, résonnaient des préparatifs frénétiques des hommes qui s'apprêtaient à partir pour une aventure qui marquerait l'histoire. En ce jour de 1097, le duc Godefroy de Bouillon, se tenait sur le parvis de son château, entouré de ses barons et de ses fidèles compagnons.

Les cris des hommes, le bruit des armures et le cliquetis des épées créaient une symphonie de bravoure et d'excitation. Godefroy, vêtu de son armure étincelante, observait ses hommes avec fierté. Chacun d'eux avait répondu à l'appel de la croisade, prêt à quitter leur terre natale pour défendre la foi chrétienne et libérer Jérusalem.

« Mes amis, » commença Godefroy, sa voix résonnant avec force, « aujourd'hui, nous faisons un pas vers l'inconnu. Nous partons pour la Terre Sainte, pour répondre à l'appel du pape et pour défendre notre foi. »

Les barons, parmi lesquels se trouvaient des figures respectées comme ses frères, Baudouin de Bouillon et Eustache de Bouillon, acquiescèrent avec enthousiasme. Leurs visages étaient marqués par la détermination, chacun conscient des dangers qui les attendaient, mais également de l'importance de leur mission.

« Nous avons rassemblé des hommes de toutes parts, » poursuivit Godefroy, « des nobles et des paysans, unis par un même but. Que notre courage soit notre guide et notre foi notre force. »

Un murmure d'approbation parcourut la foule, et les hommes levèrent leurs épées en signe de promesse. Godefroy se tourna vers le ciel, une prière silencieuse sur ses lèvres, demandant la protection divine pour lui et ses compagnons.

« N'oublions jamais pourquoi nous partons, » ajouta-t-il, son regard se posant sur les visages de ses barons. « Nous allons libérer ceux qui souffrent, défendre notre terre et notre foi. Jérusalem nous attend. »

Les tambours résonnèrent, marquant le début de leur voyage. Les hommes se mirent en marche, leurs bannières flottant au vent, symboles de leur détermination. Godefroy, à la tête de la troupe, ressentait le poids de la responsabilité sur ses épaules, mais il savait qu'il n'était pas seul. Ses barons marchaient à ses côtés, prêts à affronter les défis qui les attendaient.

Alors qu'ils quittaient Bouillon, les habitants des villages alentours se rassemblaient le long des routes, offrant des prières et des bénédictions pour la sécurité des croisés. Les enfants agitaient des drapeaux faits maison, et les femmes jetaient des fleurs sur leur passage, un geste d'espoir et de soutien.

Le chemin vers Jérusalem serait long et semé d'embûches, mais pour Godefroy et ses barons, chaque pas était une promesse de foi et de solidarité. Ils savaient que leur destin était désormais lié à celui de milliers d'hommes, tous unis par un même rêve : voir la croix flotter sur les murs de Jérusalem.

Alors que le château de Bouillon s'éloignait derrière eux, Godefroy leva son épée vers le ciel, un cri de guerre s'élevant dans l'air frais du matin. « Pour le Christ ! Pour Jérusalem ! » Les échos de sa voix résonnèrent dans les cœurs de ses hommes, une promesse d'honneur et de bravoure qui les accompagnerait tout au long de leur périple.

#Godefroy de Bouillon#first crusade#première croisade#11th century#medieval history#history medieval#moyen âge#fanfic#histoire de france

1 note

·

View note

Text

A fan art of Queen Marie Antoinette and Oscar François de Jarjayes from the manga "Versailles no Bara" or "Lady Oscar- The Rose of Versailles" by Riyoko Ikeda

#rose of versailles anime#rose of versailles fanart#takarazuka#takarazuka revue#takarazuka fanart#berubara#oscar françois de jarjayes#marie antoinette#berusaiyu no bara#lady oscar#ladyoscar#shojo#shojo manga#historical shojo#historical shoujo#shoujo#shoujo manga#french revolution#révolution française#histoire française#histoire de france#queen marie antoinette#louis xvi#versailles no bara#rose of versailles#french history#historical manga#history#histoire#takarazuka theatre

226 notes

·

View notes