#glasses exhibition catalogue

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

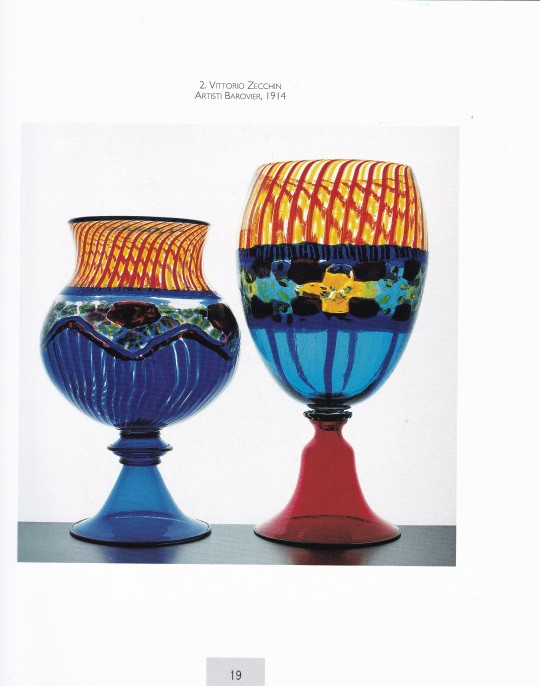

Murano Fantasie di vetro

Marina Barovier

Introduzione di Attilia Dorigato

Arsenale Editrice, Venezia 2008, 60 pagine, 48 ill. colori, brossura, 22 x 24 cm, ISBN 9788877431424

euro 12,00

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

Galleria Marina Barovier, Venezia 3 settembre - 29 ottobre 1994

60 esemplari eccezionali in vetro mosaico, a tessere e a canne dei più noti maestri e designer prodotti tra il 1920 e il 1960 nelle fornaci muranesi.

Accanto al vetro soffiatissimo, trasparente e quasi impalpabile dalle tenui colorazioni, che dà corpo a forme di rigorosa semplicità, ma di grandissima raffinatezza, i primi anni del nostro secolo, a Murano, sono testimoni anche dell’incondizionato successo del vetro morsico, noto pure col termine, improprio tuttavia, di murino. Al fascino del vetro murino non hanno saputo resistere artisti quali Vittorio Zecchin, Carlo Scarpa, Fulvio Bianconi, Riccardo Licata e Mario De Luigi, che hanno creato tessuti vitrei assolutamente inediti, nei quali la forma stessa della tessera di vetro veniva pensata in funzione precisa dell’oggetto e delle sue intonazioni di colore. Canne vitree di colori e dimensioni diversi, intrecciate spesso in complessi viluppi, con eccezionale abilità, hanno costituito tessuti vitrei vivaci quanto quelli in vetro mosaico. È a queste Fantasie di vetro che Marina Barovier ha rivolto la propria attenzione nell’ultima delle sue esposizioni, selezionando, ancora una volta, quanto di meglio Murano ha prodotto in questo settore, nel nostro secolo.

20/01/23

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano tumblr: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano

#Murano#Fantasie di vetro#glasses exhibition catalogue#Galleria Marina Barovier Venezia 1994#vetro mosaico#vetro a tessere#vetro a cannae#vetro murino#Vittorio Zecchin#Carlo scarpa#Fulvio Bianconi#Riccardo Licata#Mario De Luigi#tessuti vitrei#glasses books#designbooksmilano#fashionbooksmilano

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sottsass Glass Works

editor Marino Barovier, Bruno Bischofberger, Milco Carboni

Vitrum, Dublin 1998, 155 pages, 29x29cm, ISBN 1 902 535065

euro 58,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Catalogo pubblicato in occasione dell salone "Vitrum" presso Fieramilano, Rho (MI), 1998

Contents: Glass; by Ettore Sottsass - Glass for the 8th Triennale of Milan, 1947 - Glass for Vistosi, 1974 - Glass for Memphis (first series), 1982-83 - Glass for Memphis (second series), 1986 - "15 Lamps for Yamagiwa" Series, 1990 - "Rovine" Series, 1992 - Glass for Bischofberger Gallery, 1994 - "Big and Small Works" Series, 1995 - "27 legni per un fiore artificiale cinese" Series, 1995 Glass for Venini - "Esercizi e Capricci" Series, 1998 - Biographical notes - Museums and Galleries - List of Glass Works - List of Drawings for Glass - Bibliography.

Ettore Sottsass si laurea in architettura al Politecnico di Torino nel 1939, quindi inizia la sua attività a Milano nel 1947 dove apre uno studio di design, collaborando con Giuseppe Pagano. Nel 1949 sposa Fernanda Pivano. Fa in un primo tempo parte del Movimento Arte Concreta per aderire poi allo Spazialismo. Dal 1958 inizia la sua collaborazione, che durerà per oltre trent'anni, con la Olivetti in qualità di computer design. L'anno successivo vince il Compasso d'oro, primo di una serie di importanti riconoscimenti internazionali. Nel 1980 apre lo studio "Sottsass e associati" e nel 1981 fonda il gruppo Memphis insieme ad architetti di prestigio di tutto il mondo. Vari sono i campi artistici in cui si sperimenta, in particolare nelle arti visive. Nel 1988 esce Terrazzo, rivista da lui ideata e realizzata, e che uscirà fino al 1996. Grandi mostre internazionali e grande fama: Sottsass è stato uno dei più grandi nomi del design e uno dei maggiori architetti del secolo scorso. Morì il 31 dicembre 2007

30/06/24

#Ettore Sottsass#glass works#salone Vitrum 1998#exhibition catalogue#design books#designbooksmilano#fashionbooksmilano

0 notes

Text

Vermeer and the Delft School :: Walter Liedtke with Michiel C. Plomp & Axel Ruger

View On WordPress

#0-3000-8848-5#17th century delft#art expositions#art netherlands#books by walter liedtke with michiel c plomp & axel ruger#delft painting#delft school art#delftware#dutch art#dutch bronzes#dutch drawing#dutch glass#dutch painters#dutch painting#dutch silver#dutch tapestry#exhibition catalogues#flemish artists#gothic sculpture#history netherlands

0 notes

Text

The first outfit of "Murder & the Maiden" (Season 3, Episode 2) is a luxurious red velvet coat over a silver camisole and matching pants, complete with a shaped straw hat accented by feathers.

Known as the Coral Dreamcoat, Phryne's coat is made of a silk shot coral velvet with silver silk lining. Closer examination reveals godets (triangular inserts of fabric to add movement and width) of the velvet lined with silver piping on each side, along with a front tie and upturned sleeves with beaded decorations hanging from the ends of each.

"[The coat] has a front tie, which gives it lots of movement. Gareth Blaha, who's really quite sensational with finishing pieces, made these beautiful dangles off all the sleeves and the front tie." - Marion Boyce, Costume Exhibition Catalogue

Serving as a backdrop for her coral coat is a scoop-neck camisole with a wide hem, and flared trousers are made of a matching grey faille. Topping it all off is an authentic 1920s straw beret, adorned with a few thin maroon swirling feathers on top of a coral and maroon ostrich feather pouf and decorated with two gold buttons.

Phryne also brings along her grey woven handbag with a golden clasp that has been seen previously in 2x01 and 2x02, and ties in with the silver in her coat lining and her camisole and pants. She finishes the look with grey suede heels, white leather gloves, and glass bugle bead earrings.

Season 3, Episode 2 - "Murder & the Maiden"

Screencaps from here, promotional photos from various sources (x, x, x, x, x, x), costume exhibition photo from Dayna's Blog.

#phryne fisher#miss fisher's murder mysteries#mfmm#phryne fisher's frocks#3x02#s3e02#murder & the maiden#murder and the maiden#coral coat#vintage hats#1920's fashion#vintage fashion#costume design#costume breakdown#costume study#phryne costumes#hat photo

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

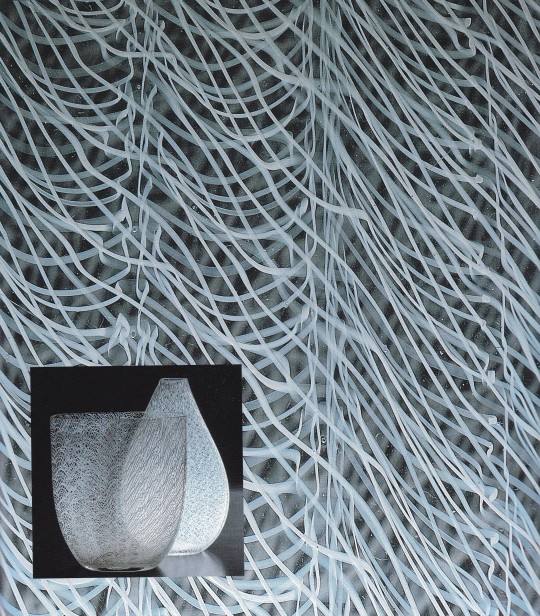

During the 1950s and 1960s the German Ruhr region was a hotbed of abstract art: artists like Emil Schumacher, Heinrich Siepmann and Gustav Deppe rekindled with the avant-garde and sought to make up for the anti-modern times of National Socialism and war. A lesser-known exponent of abstract art was Hans Kaiser (1914-1982), born in Bochum, autodidact and since 1950 residing in Soest, a middle-sized town on the outskirts of the Ruhr region. Up until his death Soest remained the center of his life and it is also here that he inscribed himself in many ways into the town’s face, most prominently in the form of different stained glass windows for the St. Patrokli church.

Stylistically Kaiser went through a number of changes but one aspect of his style remained persistent, namely a calligraphic, writing-like fastidiousness that is present in both his abstract works and in his portrait drawings.

In 2014 the Kunstmuseum Bochum under the title „Hans Kaiser - Imaginäre Räume“ dedicated an exhibition to Kaiser’s so-named „Losschreibung“, i.e. the development of his specific artistic language: as a result of the disentanglement from the image and the simultaneous discovery of writing as the form of conveying the meaning of words Kaiser created imaginary spaces that point beyond language and meaning. The accompanying catalogue in an impressive selection of works from the 1960s up until the 1980s documents Kaiser’s development of imaginary spaces on canvas and paper and demonstrates how the writing-like elements gradually give way to ever deeper spaces made up of colors alone.

In his portrait drawings, as shown in Erich Franz’s catalogue from 2003, Kaiser in turn dissolves the seeming contradiction of abstraction and object by letting the pen „write“ itself into the drawing, a modus operandi that creates obvious parallels between the portraits and abstract works: in both cases writing-like structures provide a self-determined dynamic that is unique to Kaiser’s post 1957 works. At the same time the drawings, unlike the paintings, incorporate the white of the sheet paper and activate them as integrative to the overall dynamic of the portrait and show that Kaiser was in no way afraid of the blank space.

Against the background of the previously discussed qualities and characteristics discussed of Hans Kaiser’s art it is irritating that he is still relatively unknown beyond Soest and the Ruhr region…

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

For your drabble writing thingy🫶

Pairing: Carloscar

Word: satisfaction

Let the rarepair enthusiasts froth at the mouth (me included)! -lo

how satisfying (human behaviour)

a carloscar flash fic rated m 1.3k words read on ao3

dedicated to @lovelylotusf1 for the prompt, and @carlosheinz who is the resident carloscar preacher of the parish.

preview:

Today: Oscar’s hotel room. Too-big bed. Oscar catalogues sensations. A part of his mind, cold and detached. His life on exhibition, behind safety glass. A sign: not too close, please. Mattress, softer than he’d like. Linen, scented in a forgettable hotel way. Minty mouthwash fighting the horrid cinnamon gum, an overwarm taste he has come to know as Carlos. Oscar spent time earlier, pulling different sounds from Carlos. Biting a point on Carlos’s neck, to feel the engine of him growling under Oscar’s own jaw. Minutes slipping onwards as he worked Carlos into a point of sharpened need. Now, Carlos is sprawled out on his back, beneath Oscar. Their two faces flushed, breathing just a little heavier. They’re both proud, and never like to let the effort show.

(this was meant to be a small drabble and i LIED, i'm sorry, the carloscar prompt was just too good. here i am submitting my application to be a permanent resident of carloscar nation.)

#carloscar#f1 rpf#oscar piastri#carlos sainz#carcar#f1 fanfiction#f1 fanfic#f1 fic#formula one fanfiction#formula 1 fanfic#wiz.writing#f1 fiction#op81#cs55#formula 1 rpf#f1 rpf fic#f1blr#prompt fill#tense shifts that don't make sense? it's 2am over here - just pretend u did not see it

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Machine-Age Exposition catalog, New York, 1927

Machine-Age Exposition was held on 16–28 May 1927 at 119 West 57th Street in New York, being advertised as the first event bringing together “architecture, engineering, industrial arts and modern art.”

The exhibition was initiated by Jane Heap of The Little Review, a New York literary magazine, and organised along with Société des urbanistes, Brussels; U.S.S.R. Society of Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries; Kunstgewerbeschule, Vienna; Czlonkowie Group Praesens, Warsaw; Architects D.P.L.G, Paris; and Advisory American Section.

The artists committee of the exhibition included Alexander Archipenko, Robert Chanler, Andrew Dasberg, Charles Demuth, Muriel Draper, Marcel Duchamp, Josef Frank, Hugh Ferriss, Louis Lozowick, André Lurçat, Elie Nadleman, Man Ray, Boardman Robinson, Charles Sheeler, Ralph Steiner, Szymon Syrkus and L. Van der Swallmen.

Represented countries: United States, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Poland and Soviet Union.

The catalogue contains a panorama of European and American architecture and art, with photo documentation, and following articles: “Foreword: Architecture of this Age” by Hugh Ferriss, “The Aesthetic of the Machine and Mechanical Introspection in Art” by Enrico Prampolini, “Machine and Art” by Alexander Archipenko, “The Americanization of Art” by Louis Lozowick, “French Architecture” by André Lurçat, “Architecture Opens Up Volume” by Szymon Syrkus, “Machine-Age Exposition” by Jane Heap, “The Poetry of Forces” by Mark Turbyfill, and “Modern Glass Construction” by Frederick L. Keppler.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

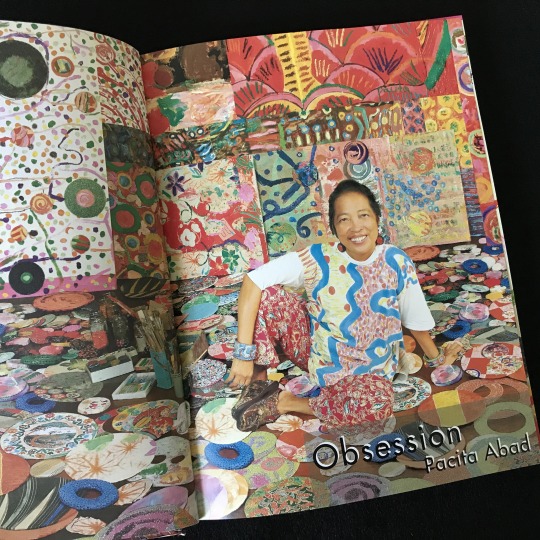

A Filipino-American artist Pacita Abad (1946-2004) was born in Batanes, Philippines, and lived in Philippines until her parents urged her to leave Manila in 1970. As a law student, Abad had begun to organize demonstrations opposing the dictatorial regime of Ferdinand Marcos. Her organizing activities led her and her family in Manila to become targets of political violence. Abad took her parents’ advice and left Philippines. She enrolled at the University of San Francisco to study Asian history while supporting herself as a seamstress and a typist.

Abad became interested in art and eventually became a global artist. She has lived in many countries, including Bangladesh, Yemen, Sudan, Papua New Guinea, and Indonesia, incorporating many different techniques and styles she encountered in her travels into her artwork. Abad would sew, stitch, and collage objects such as stones, sequins, glass, buttons, shells, and mirrors onto painted canvas to create vibrantly colorful works.

Fortunate for those who can visit Harvard, Abad’s work is now being shown as a part of “Future Minded: New Works in the Collection” at the Harvard Art Museums, which is free to the public.

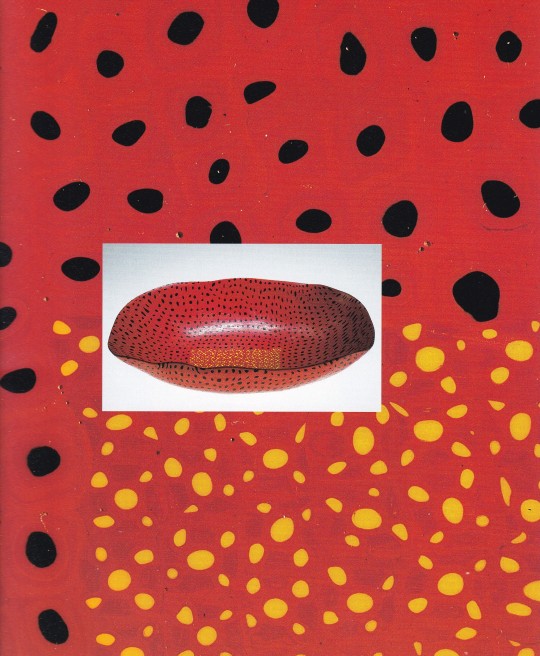

Image 1: Pacita Abad featured in the publication, Obsession

Image 2: “The Great Barrier Reef,” 1991. Mixed media. Currently being exhibited at the Harvard Art Museums.

Obsession Pacita Abad; [catalogue edited by Jack Garrity; with essays by Ian Findlay-Brown and Ruben Defeo]. [Singapore : Pacita Abad Foundation], c2004. English HOLLIS number: 990107751490203941

#WomensHistoryMonth#PacitaAbad#FilipinoAmericanArtist#WomenArtist#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvard art museums

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello everybody i am here again to infodump about a random subject that no one else cares about but i think is interesting and want to share

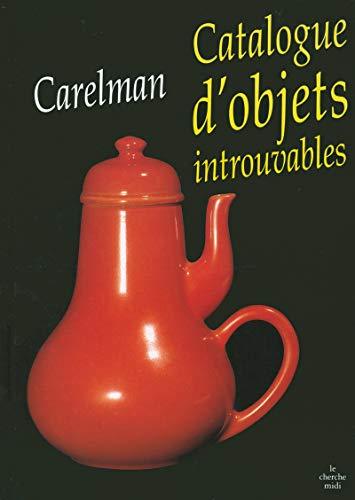

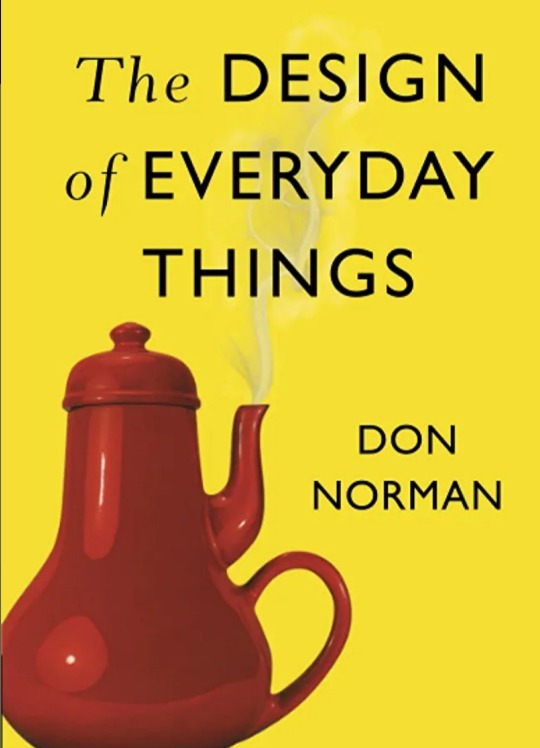

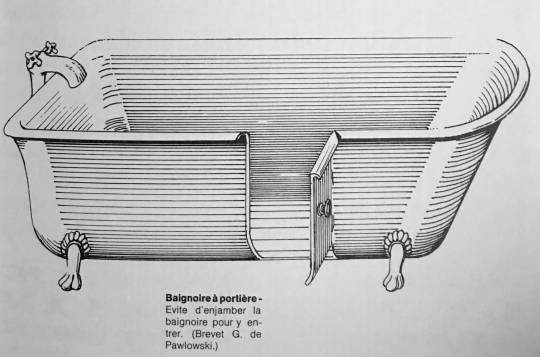

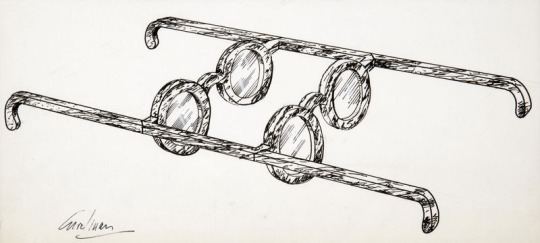

Jacques Carelman (born 1929 - died 2012) was a french painter, illustrator and designer. he has done many things in his life but the thing hes most known for is his book, "Catalogue d'objets introuvables" sometimes translated to "Catalog of fantastic things", or more accurately, "Catalogue of Unfindable Objects", first made in 1969 as a parody of the catalog of the french mail order company Manufrance.

as in what he was specifically parodying were mail order catalogues. common at the time, these were paper publications that showcased various cool and new everyday objects that the readers could order to buy from the mail (the old time equivalent of shopping on amazon)

what his book did, however, was illustrate an entire catalog of objects that are completely nonsense, absurd, useless, and as a whole either impossible to use or unnecessarily hard to, for no reason at all. possibly his own commentary on the consumerist culture of the time that motivated regular people to incessantly buy more and more superfluous objects for everyday use

some of the objects featured in the catalog include:

the famous Carelman Teapot, called by himself "Coffeepot for Masochistics", featured on the cover for "The Design of Everyday Things", book still studied to this day by designer majors

the bathtub with a door, to be easier to get in and out :)

the retro watch

the co-op glasses, for a good shared reading

the free pdf for the entire book with all objects can be found here, which is in italian because its the only pdf i could find. i think its a fun experience to skim through and just check all the weird shit in it!

finally, jacques carelman had some of the objects of his catalog actually made in real life and exhibited from november 1974 to january 1975 in La Vieille Charité, a museum in Marseille, France. heres a video i could find of the exhibition:

#had to rewrite this entire post cause tumblr ate it at first. is it truly worth it#anyways maybe thats not super cool for everyone else but i thought it was interesting! finding that pdf was a hassle#the catalog#<- for me to find it

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

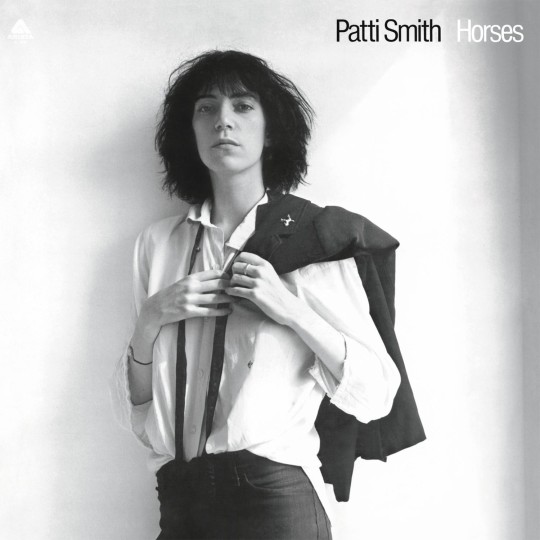

365: Patti Smith // Horses

Horses Patti Smith 1975, Arista

There’s a man named Nicky Drumbolis who lives up in Thunder Bay, Ontario, in an apartment that doubles as perhaps Canada’s greatest bookstore almost no one has ever seen. The septuagenarian Drumbolis is short and nearly deaf, a master printmaker and eccentric autodidact linguist. For years he ran a second-hand shop on Toronto’s Queen St. called Letters, until push (the size of his collection) came to shove (skyrocketing rent) and he went north, where he could afford a sufficiently large space to spread out. Unfortunately, Thunder Bay has little market for antiquarian books and micro press ephemera, and his shop is located on one of the most crime-ridden streets in the country. And so, the transplanted Letters has no storefront—in fact, the building looks derelict, its windows boarded up and covered with what at first glance seems to be graffiti but on closer inspection resembles a detail from the cave paintings at Lascaux. Letters’ patronage is limited to the online traffic in rare first editions that brings him a small income, and the occasional by-appointment adventurer willing to make the long, long 1,400 km drive from Toronto or further abroad.

When you enter, you find yourself in what appears to be a well-kept single room used bookstore, the kind there used to be dozens of in every major city. Books of every type and topic line the shelves, neatly arranged by category, and a long glass display features more delicate items, nineteenth century broadside newspapers and the like, some so fragile they seem on the verge of crumbling into dust. But this is not, Drumbolis warns you as soon as you attempt to take a book off of the shelf, a bookstore: this room is a facsimile, a tribute exhibit to as he calls it, “the fetish object formerly known as The Book.” The real bookstore lies in the chambers beyond this front room, the full catalogues of bygone presses, the one-of-one personal editions he’s assembled over decades of following his personal obsessions, the stacks which crowd his own modest sleeping quarters.

To Drumbolis, the original utility of the book as a container and mediator of information is now effectively passed; virtually every popular book in existence has been digitized, their contents instantly available in formats that are better-indexed, more easily parsed, and more readily transferrable than the humble physical book ever allowed. To desire a book is to desire possession of the thing rather than its contents, this edition, this printing, perhaps this particular copy that once passed through the hands of someone significant. He can show you the copy of John Stuart Mills’ On Liberty that was owned by Canada’s founding father John A. MacDonald, and argue convincingly that this object helped set the course of a nation’s history; or a set of Shakespeare’s complete works bearing Charles Dickens’ ex libris, which sets off a long anecdote about how Dickens liked to troll his houseguests with a collection of fake bookshelves. Drumbolis’s collection is threaded through his life like an old wizard in a fantasy novel whose flesh has fused with the roots of a tree: he eats with his books and he sleeps with them; collecting fuels his arcane research and dictates where and when he travels; 25 years ago he uprooted his life when his collection bade him, and though he’s starved for company in the frozen city it chose for him, he abides.

youtube

My own case of collectivitis is not so advanced, though Lord only knows what I’ll be like when I’m Old (I’m currently 47). And despite the conceit of this blog, I’ve seldom spent much time in these reviews dwelling on the physical properties of my records, evaluating the relative merit of pressings and the like (or even mentioning which one I’ve got). But as I sit here listening to my copy of Patti Smith’s Horses for the first time, I feel a small but definite sense of wonderment. It’s an early ‘80s Canadian pressing, so near-mint I might’ve stepped back in time and bought it new, still with what I take to be the original inner-sleeve, pale azure (to match the Arista disc label) with a texture almost like crepe paper.

It’s a delightful, surprising contrast to the iconic black and white cover portrait of Smith by her former paramour Robert Mapplethorpe. Generations of fans have stared at this image as they listened, not simply because Smith is hot (though this is undeniably true) but because the music’s visionary qualities demand an embodied locus. That a record, unlike a book, can speak aloud, has always primitively fascinated me; that this one contains what I can only describe as rituals makes it magical, this physical copy that is unique because it’s this one that is speaking to me in this moment.

Smith writes on the back of the sleeve:

“…it’s me my shape burnt in the sky its me the memoire of me racing through the eye of the mer thru the eye of the sea thru the arm of the needle merging and jacking new filaments new risks etched forever in a cold system of wax…horses groping for a sign for a breath…”

“charms, sweet angels,” she concludes. “you have made me no longer afraid of death.” The record becomes an extension of Smith’s body as it existed in that time—I think here of the physicality of the moment in “Break it Up” where you can faintly hear her striking her own chest with the flat of her palm to make her voice quaver. It makes me wonder how anyone could sell this thing once they have it: not because it is particularly rare or difficult to acquire, but because it’s hard for me to imagine the experience of slipping the lustrous black disc from its dressing and setting the needle down upon it as anything but a personal one. It is poetry and waves; the subliming of the idea of a rave-up; Tom Verlaine shedding his earthly mantle in an explosion of birds; John Cale; Kaye, Král, Daugherty, and Sohl; one of my boys from Blue Öyster Cult; the pounding of hooves and the Mashed Potato.

I suppose what I’m describing is a fetish, my pleasure in acquiring these things and writing these reviews the hard and strange work of finding life’s joy in its dusty corners. This year has run through my fingers like water, as it seems they all do now. But on my good days, all these words behind me and the records in front of me seem like a document of abundance.

youtube

365/365

#patti smith#horses#john cale#lenny kaye#ivan král#blue oyster cult#tom verlaine#punk rock#art rock#female singer#poetry#collecting#music review#vinyl record#'70s music#the end

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Richard Nixon defied expectations and went to China in 1972, Henry Kissinger, his national security advisor, packed the president’s briefcase. Among Nixon’s reading materials was The Chinese Looking Glass, a book by British journalist Dennis Bloodworth about understanding China on its own terms. In his opening pages, Bloodworth sets the stage by going back to the beginning: “The gaudy catalogue of China’s disasters and dynastic glories, whose monumental scale has given the Chinese much of their character … brings us to our true beginning.”

Kissinger, one of America’s most consequential foreign-policy leaders in recent memory, clearly internalized the centrality of China’s “true beginning.” In his 2011 tome On China, Kissinger marveled at China’s “singularity” and staying power. Indeed, even the hardest of hearts cannot help but be moved by the continuity of a civilization that predates the birth of Christ by hundreds, even thousands, of years.

Awe, however, is no substitute for knowledge. In the opening pages of On China, Kissinger writes of China’s “splendid isolation” that cultivated “a satisfied empire with limited territorial ambition.” The historical record, however, contradicts him. From the Qin dynasty’s founding in 221 B.C. to the Qing’s collapse in 1912 A.D., China’s sovereign territory expanded by a factor of four. What began as a small nation bound in the fertile crescent of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers morphed into an imperial wrecking ball. In the words of Bloodworth, the very author Kissinger recommended to Nixon in 1972, “It would be absurd to pretend that the Chinese had never been greedy for ground—they started life in the valley of the Yellow River and ended by possessing a gigantic empire.”

To be sure, China was not the aggressor in every war it fought. In antiquity, nomadic tribes regularly raided China’s proto-dynasties. During the infamous Opium Wars of the 19th century, Western imperialist powers victimized and preyed upon China at gunpoint. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regularly refers to China’s “Century of Humiliation,” when European empires brutalized China and killed or wounded tens of thousands of Chinese men, women, and children. Indeed, the party has memorialized these grievances in a permanent exhibit of the National Museum of China, just steps away from Tiananmen Square.

For all of Beijing’s legitimate and long-standing security concerns, however, the sheer scope of China’s expansion is undeniable. Western leaders often deny or ignore it, usually at the behest and prodding of Chinese leaders. When Nixon finally gained an audience with Mao Zedong, he reassured the chairman, “We know China doesn’t threaten the territory of the United States.” Mao quickly corrected him: “Neither do we threaten Japan or South Korea.” To which Nixon added, “Nor any country.” Within the decade, Beijing invaded Vietnam.

At the time, Nixon’s gambit was to split the Soviet bloc and drive a wedge between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Nixon and Kissinger saw the Sino-Soviet split and took stock of the PRC’s trajectory: a growing population that, once harnessed, was poised to dominate the global economy. It was textbook realpolitik: cold, dispassionate tactics divorced from moralism. If Washington could turn the Soviet Union’s junior partner, the West could significantly hamper Moscow’s ability to project power into Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia.

During the final years of Nixon’s life, his presidential speechwriter William Safire asked him about that fateful trip to Beijing in 1972. Had opening up to the PRC made Americans safer and China freer? According to Safire, “That old realist, who had played the China card to exploit the split in the Communist world, replied with some sadness that he was not as hopeful as he had once been: ‘We may have created a Frankenstein.’” Over time, many in the United States have come to realize this predicament. Unfortunately, articulating that problem well has proved difficult.

During her brief stint as director of policy planning at the State Department in 2019, Kiron Skinner previewed the shop’s keystone intellectual project: a strategy to counter China, in the spirit of George Kennan’s “containment” strategy. At a public event in April 2019, Skinner tipped her hand and revealed her philosophy of U.S.-China competition: “This is a fight with a really different civilization and a different ideology, and the United States hasn’t had that before.” She went on to add, incorrectly: “It’s the first time that we will have a great-power competitor that is not Caucasian.” Skinner received widespread criticism for these remarks and was soon after dismissed for unrelated issues.

Skinner’s mistake was twofold. First, she simply got the history wrong and ignored imperial Japan in World War II. Of deeper consequence was her failure to explain what strategic culture actually is, why it matters, and how China’s past shapes the CCP’s behavior today. In fairness, these errors aren’t unique to Skinner. Understanding Chinese history can be difficult for most Westerners. In some ways, it’s difficult to think of two more different nations. The United States is less than three hundred years old.

China was unified more than two hundred years before Christ was born. Immigrants founded America. Denizens established China. The United States was born out of revolution against a colonial power. China came into being from a regional conflict of gigantic proportions. Favorable geography allowed America to grow economically and territorially on its own terms and at its own pace. China came into being surrounded by rival kingdoms and tribes on every side.

Americans turn to one source more than any other to make sense of these differences: The Art of War, by Sun Tzu. One of his more recognizable dictums, “All warfare is based on deception,” has captured the imagination of many Western thinkers. Instead of investigating the history that informed Sun Tzu’s counsel, however, many policymakers take the easier path of Orientalizing China. “China thinks in centuries, and America thinks in decades” is a well-worn trope. Another well-meaning but vapid cliché is, “America plays chess, but China plays Go.”

These statements are often left untethered from history and offered as self-evident axioms. What’s left are useless clichés that offer no actual understanding of why Chinese strategists advised cunning and deception, or how China’s unique historical experiences informed military tactics. In the absence of curiosity, an impression easily forms of China as “the other,” a mysterious, inscrutable competitor. A shallow understanding of Beijing’s past leads to incomplete conclusions about its present behavior.

More often than not, policymakers find it easier to avoid China’s history entirely. In late 2020, the policy planning office finished the 72-page report. It was a commendable attempt to reprise Kennan’s strategic clarity, but China’s dynastic strategic culture received a single page of attention.

Reducing strategic culture to vague racial differences helps no one except Chinese President Xi Jinping and his party henchmen. The CCP works to enmesh itself with the Chinese people and regularly uses them as a rhetorical human shield. To criticize the CCP, according to the well-worn rhetorical trope of Beijing’s diplomats, is to “hurt the feelings of 1.4 billion people.” As a matter of course, Beijing uses this specious logic to construe anti-CCP policies as evidence of racism. Years before former U.S. President Donald Trump fell headlong into this trap with his careless rhetoric about the “Chinese virus” and “kung-flu,” a young generation of China hawks had vowed to evade this pitfall.

Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin wrote about this resolve in his 2021 bestseller, Chaos Under Heaven, which documented the collective decision of Washington, D.C.-based China hands to blunt Beijing’s attempts “to divide Americans by party or ethnicity, to divert attention from its actions.” I was a regular member of those meetings and still believe America’s leaders must differentiate the party from the Chinese people—not only out of respect for those who daily live under the CCP’s jackboot, but also for the safety of Chinese Americans, who faced a rise of race-based crime in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. But, in doing so, America must avoid a separate trap: equating the party with China.

China’s history did not begin in 1949 when Mao and the CCP established the PRC. Nor did it start with China’s “Century of Humiliation,” when European imperialist powers forcibly opened China in the mid-19th century. Chinese civilization predates America and the West by orders of millennia. That context gives meaning to the party’s contemporary behavior. The themes of greatness, fall, and restoration hidden in Xi’s remarks in 2013 constitute the essence of Chinese history.

They are the four-act play of China’s story, or “strategic culture”—without which it is impossible to understand the CCP’s strategy today. Strategic culture explains how a country’s unique experiences shape distinct national identities that translate into foreign policy. These three elements—story, identity, and policy—reinforce and shape one another. To be sure, the CCP has its own story, identity, and policies, but the party is one tributary in a long river. American leaders cannot prevail against the CCP without understanding the story and identity that belong to China.

From the start, China has been a civilizational juggernaut striving for political hegemony. China has often attempted to conceal this ambition with conciliatory diplomacy, but its neighbors know from experience the struggle to live—and survive—in the dragon’s shadow. CCP diplomats often bully China’s neighbors by claiming sovereignty over part or all of their territory “from time immemorial”—an inadvertent admission that the party is the latest crusader in a long line of imperialists. This struggle that was once relegated to the nations of East Asia is now a challenge for every country in the world.

Beijing is approaching the world not to embrace it, but to rule it. The Western world has no excuse for missing this reality, and American politicians have badly misjudged Beijing for decades. Washington’s China policy will continue to be a “two steps forward, one step back” affair until it reckons with the Middle Kingdom’s penchant for imperialism.

This reality calls into question the unspoken objective of American policymakers: seeking a democratic China. For all their differences, both hawks and doves in the United States have framed the “China problem” as an ideological challenge. Proponents of engagement believed that economic contacts would necessarily lead to political reform, a belief rooted in liberal internationalism. Advocates of confrontation couch the CCP regime as the problem, which implies an ideological solution.

The one unchanging constant in America’s China policy since Nixon’s meeting with Mao in 1972 is the steady commitment to regime change, either by commerce or competition. The underlying belief in the universal power of democracy has proved intoxicating. “If we can just make them like us,” the thinking goes, “we can turn an enemy into a friend.”

Perhaps this self-delusion is inevitable. America’s national identity is steeped in beliefs about liberty, equality, and opportunity. But the CCP’s heritage raises an uncomfortable question for the United States: Even if modern China were to become a democracy, would it cease to be the Middle Kingdom?

If the CCP collapsed and China followed Taiwan’s path of economic and political liberalization, would it suddenly lose its appetite for hegemony? Maybe. Then again, perhaps simplifying Beijing’s behavior to its current Communist Party overlords ignores thousands of years of China’s own history, as well as the strategic culture that informs those decisions.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Super Famicom - John Madden Pro Football 93

Title: John Madden Pro Football 93 / プロフットボール'93

Developer: Looking Glass Studios / EA Canada

Publisher: Electronic Arts Victor

Release date: 12 February 1993

Catalogue Code: SHVC-JM

Genre: American Football

No. of Players: 1-2

Madden 93 for its time is a great game and is still pretty fun to play today. I'm pretty sure this was the version Hudson Soft used as reference when they made John Madden Duo CD Football for the Turbo Grafx CD in North America. The game contains all of the NFL teams of the day and all the right numbers for each player. The gameplay itself is also pretty solid. The controls may take some time to learn if you do not have the instructions but a quick look on the internet and the controls will become second nature.

On the downside, Madden 93 is a very bare-bones game by today's standards. The game contains no season mode and only a playoff tournament (which oddly contains no Super Bowl), though it does give a pretty comprehensive halftime and post-game summary, including 3rd and 4th down conversions, passes completed, total passing yards, rushing yards, and even a scoring history.

The graphics aren't much to look at, even by Super Famicom standards. All the players look exactly the same with an odd tan and cream skin color and this only starts to become a problem when it comes to the passing game, where it's hard to keep track of which player is where. Also due to the overhead camera, sometimes it can be a little hard to tell exactly how far you have moved, and in a 3rd and 1 situation, it will sometimes make or break the whole game.

A few other complaints are that the game only offers 5-, 10-, and 15-minute quarters, so if players want to plug in, they better be prepared to play a good length game. Another slightly more annoying one is that you don't get to see other team stats until you already get started on a game, which can be hassle-some for any exhibition games.

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Damien Hirst (UK, Bristol, 1965)

Death is irrelevant

Skull. Marker on paper 58.5 x 47 cm. (catalogue cover)

Crucifix detail, 2000, Glass, steel, aluminium, human skeleton, compressor and ping-pong balls, 91.4 x 274.3 x 213.4 cm

thnx dotglobal

https://gagosian.com/news/museum-exhibitions/damien-hirst-death-is-irrelevant-hudson-valley-moca-peekskill-new-york/

https://www.artnet.com/artists/damien-hirst/death-is-irrelevant-wolXQUF2RuKTkny-0egZXA2

#Damien Hirst#sculpture#installation#assemblage#skeleton#crucifix#eyes#levitation#skull#drawing#series#humour

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unknown Egyptian Artisan, Pectoral with Solar and Lunar Emblems, from the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), New Kingdom - Dynasty XVIII, ca. 1330-1323 BCE

At the heart of this magnificent pectoral pendant from the Tomb of Tutankhamun there is a scientific wonder. Since the time of its discovery, archaeologists assumed the central scarab was carved from some kind of semiprecious gemstone. In the catalogue of the famous 1976 exhibition it is listed as chalcedony. However, at the time of the recent reinstallation of items from Tut's tomb at the new Egyptian Musuem, some archaeologists began questioning that. It didn't add up. Tests were run. It's not a gem at all.

It's glass.

Morever, it's not man-made glass. This is a very specific, and very rare, natural glass found in the Sahara. In the Great Sand Sea on the border of western Egypt and eastern Libya there is an area of a very ancient meteor strike which set the desert on fire, and melted the sand into glass. This glass is called impactites.

To be poetic, it's glass from the gods. The ancient Egyptians highly prized it, and seem to have reserved it only for royal use.

Tut's tomb also included a dagger made of iron from a meteorite deposit, so it contained multiple instances of including the "cosmic" to be used in the afterlife.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On an unseasonably warm day in October, the silence outside broken by birdsong and artillery fire, Olga Goncharova sat in her office on the ground floor of the Kherson Regional Museum, a bulletproof vest wrapped around the back of her chair, the windows covered with plywood, and cursed the Russians. “They’re vandals, the people who did this,” she said.

Ms Goncharova escaped from Kherson, in southern Ukraine, in the spring of 2022, shortly after Russian troops poured into the city. By the time she returned, in November that year, Kherson had been liberated. The Russians had evacuated to the other bank of the Dnieper river, from which they have been bombing the city ever since. Ms Goncharova wept when she entered the museum where she had worked for over two decades. “There was broken glass everywhere,” she says. “They had torn some of the exhibits out.”

In fact Russian officials, assisted by local collaborators and the museum’s then-director, had removed more than 28,000 artefacts, loaded them onto lorries and shipped them to Crimea, illegally annexed by Russia in 2014. Gone were the ancient coins, the Greek sculptures, the Scythian jewellery, a precious Bukhara sabre—and even the hard drives containing the museum’s catalogue. Three decades ago, Ms Goncharova says, the museum recovered a collection of Gothic bronzes looted by German occupiers during the second world war. Now the Russians have stolen them.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022, the loss of life and suffering in Ukraine has been great. Many of its museums have been plundered, too. The country’s ministry of culture estimates that over 480,000 artworks have fallen into Russian hands. At least 38 museums, home to nearly 1.5m works, have been damaged or destroyed.

Ukrainian officials have also sent a number of collections to other parts of Europe to protect them from Russian bombs. These include dozens of Ukrainian paintings from the early 20th century, on display at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels before travelling to Vienna and London. When the evacuated treasures will return to Ukraine is unclear.

Artists have not been spared either. Ms Goncharova points to a painting of dried flowers and pottery that hangs opposite her desk. The artist, Vyacheslav Mashnytskyi, from Kherson, went missing after Russian troops turned up at his riverside dacha and requisitioned his boat. Friends who stopped by the house days later found traces of blood. Mr Mashnytskyi has not been heard from since.

Putting a price on the stolen works is nearly impossible, since only a fraction had been appraised for insurance purposes. Last April the un estimated that the war had caused $2.6bn-worth of damage to Ukraine’s cultural heritage. That now seems to be a conservative figure. Tracking what the Russians have looted is also a headache. Many Ukrainian museums, especially smaller regional ones, had relied on paper catalogues, often outdated or incomplete, says Mariana Tomyn, an official at the culture ministry. Some of those catalogues have now gone. Efforts to digitise inventories, which began only three years ago, have taken on a new urgency.

Ukraine will seek redress. Prosecutors in Kyiv are investigating Russian officials and Ukrainians involved in the plunder. Mrs Tomyn is working on a new restitution law and the overhaul of an outdated one on the protection of cultural heritage. And since late October a special army unit has begun to monitor damage to cultural sites. But there is little hope of recovering what the occupiers have stolen. Russian officials will ship Ukrainian collections stored in Crimea to Russia if Ukraine retakes the peninsula, says Vyacheslav Baranov, an archaeologist at Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences.

There have been some breakthroughs. On November 26th, after a long court battle, hundreds of historical treasures from Crimea were returned to Ukraine from the Netherlands. The collection, which includes Scythian gold carvings from the fourth century bc, had been on display at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam in 2014. Russia demanded the return of the objects to the Crimean museums which had loaned them. The Dutch supreme court ruled in 2021 that they belonged in Ukraine.

They are not the only ones to make their way back. At the Lavra museum complex in Kyiv, Maksym Ostapenko slowly unwraps a bundle of white packing paper. Out of it emerges a Bronze Age battle-axe. Another bundle yields a sixth-century Khazar sword. In the summer of 2022 the weapons, plus a few other objects probably destined for America’s antiquities market, surfaced at John F. Kennedy airport. The American authorities sent them back to Ukraine a year later. Most were probably excavated illegally in southern Ukraine, near Crimea, says Mr Ostapenko, the museum’s director, or discovered by Russian troops digging trenches. Such archaeological looting has thrived in the occupied territories, he adds. “The damage done to cultural heritage is immeasurable"

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sand on your Shores (2)

There was nothing quite like being spat out of the Sea of Chaos to drive home just how annoying you could be. Then again, Percy reflected, when your opponent was Gaea, perhaps being a pest too annoying to countenance was what you ought to aim for.

It would prove terrible for your continued good health though, as the steadily growing ache in his chest indicated.

Percy couldn’t quite bring himself to open his eyes. Any second, the grass stinging his hands would trap him in verdant loops, the pebbles under his back would burrow into his body, and the thick loam all around engulf him in its constricting embrace.

He sucked in a reluctant breath.

The air taste weird. A strange thing to fixate upon when he'd just brought about the end of the world, but Percy couldn't take his mind off it.

The air smelled weird too, but the stink radiating off his own body made it impossible to catalogue his surroundings.

And the pain – couldn't forget the pain even if it had become a regular companion. A splitting, shrieking agony as exposed nerves and sinew screamed at being so summarily cleaved from the protection of the rest of his body.

He didn’t want to look at it.

Didn’t want to think about it.

So … the air. That tasted strange.

He couldn't quite identify why. There was a certain lightness to the air, a distinctly pastoral sweet pollen and sharp grass, mixed with the wet mud of just rained upon land. But the absence of tangy pine needles and gritty exhaust shouldn't have struck him as strange as the glass shore of the Cocytus.

It was reality – just a step to the left.

The reminder that there were directions other than straight on top of a rock galvanized his head into lolling to the side.

Percy's head tipped to the left.

Glistening black eyes without a hint of sclera stared back at him.

Percy flinched.

Before forcing himself to take a closer look.

A thin yellow ring of skin encircled fishlike eyes that seemed to take up half the face.

A face that stared back at him like a distorted reflection, like his bathroom mirror had malfunctioned and silver shimmered to craft an illusion of a twin not quite right.

“You look just like me,” the doppelganger whispered, flashing sharp fangs that must have been sheathed into the top of his skull to have any hopes of not slicing his own mouth into pieces.

“You … don’t,” Percy mumbled back.

He couldn’t deny a certain similarity to the facial structure, couldn’t deny that they shared the same bend in the bridge of their noses, the same dip in their chin that didn’t quite reach a cleft, certainly couldn’t deny the matted black hair that shone with blue highlights underneath the Mediterranean Sun.

But he had never sported odd, defined scars along his neck that reminded him of nothing but a fish’s gills, had never exhibited gossamer filaments growing from between his shoulder blades in a pale mimicry of a backfin.

“Who’re you?” the fish person demanded, flailing but failing to push himself into a sitting position.

“Percy,” Percy replied. “Percy–”

“Jackson,” the other finished in a horrified whisper.

His own name shouldn’t have struck such unnamed horror into his being.

“But I’m Percy Jackson,” the half-fish person refuted intensely.

“You can’t be,” Percy rejected instantly. “I’m–” he broke off.

What had been the last thing he’d undergone, what was the cause of the torn, weeping, gaping wound in his self? His every fibre throbbed like it had been stripped of something indelibly crucial.

Fingers trembling only partially with exertion, Percy reached out and touched the blue half-moon protrusions covering the fish-person’s naked chest.

Bliss.

Just for a moment, the pain disappeared.

Just for a second, one that ended much too soon, Percy felt whole.

The person on the other side of his hand flinched back.

The ecstasy faded back into the ever-present agony of existing, made all the more excruciating from the momentary relief.

Sea green stared into nocturnal black.

“We’re both Percy,” the other person voiced the conclusion Percy couldn’t quite prevent himself from reaching.

Percy shuddered.

Split in two, on land distinctly different from his memories, with a Sun indecipherably brighter, in a climate without the markers of industrial pollution Percy had never lived without – it jogged memories he’d done his best to bury inside the room with the glass mirror.

The room that might have slipped at containing the poison-manipulating tormentor of Akhlys, but which would certainly hold memories at bay.

The room with its glass fragments and a gaping void where there should have been a maelstrom of power.

Screaming. The very Earth was screaming. Roiling, cracking, burning. Every single second the inferno in the sky continued blazing, was accompanied by another mighty heave of the land.

Earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, avalanches, landslides.

Toppled civilizations.

Dust rose in the distance in a great cloud as Gaea’s dying spasms destroyed skyscrapers and laid mountains low.

Percy … Percy was the son of the Earthshaker. Son of the Lord of the Sea.

As Jason, Leo, and Piper fought to kill Gaea, Percy shattered the boundaries within himself, until his body burnt with the power flooding through every single blood vessel of him, until fragile flesh burst in star-blooms.

Grip the earth, hold the ocean still, calm the magma bubbling below the crust.

“No, I won’t die. You can’t kill me!” Gaea shrieked with the eruptions of a thousand geysers.

Percy tightened his grip as the very land rolled over onto itself in an effort to stomp out flames fuelled by human life.

Grimly determined, Percy tightened his hold on every domain his father would allow him access to and refused to give an inch.

“You would defy me?” Gaea shrieked. “You can’t. I am Chaosdaughter, the first primordial. I am Earth. I have been and always must be. You can’t stop me.”

“I already have,” Percy thought back at the goddess and restrained yet another twitch that threatened to send the Eastern Seaboard under.

He refused to think of the broken bodies at camp, the snap of bone that had reverberated in his ears, the blank stare that should have never entered those grey eyes.

Annabeth …

“No, you haven’t,” Gaea whispered back.

Something punched through him. Percy looked down, not particularly surprised to see the spear-shaped rock impaling him.

He didn’t let Gaea go.

Gaea writhed, twisted the ground and the sky and the very fabric of reality itself.

Like sand struggled to capture water, she slipped through Percy’s fingers.

No, no, no. She didn’t get to. Not when everyone else …

Percy severed the lingering connection to his dying body and chased Gaea. He’d never let her accomplish her goals. Never, never, never.

Gaea, the queen, the eternal, the sleeper – what power did she hold against Percy, who’d destroyed every single enemy he’d ever opposed, who’d fought and fought without respite? Gaea might have taken refuge in sleep and century wide plots, but Percy had never had that option.

Gaea attempted to retreat, but Percy only knew how to attack and attack even as the nothingness of the void ate away at him.

“You’d follow me to the past?” Gaea demanded hysterically. “Then see how much you like the world ruled by my children!”

“You don’t deserve to live in a world you like,” Percy hissed back.

Gaea glittered in the midst of nothing like a thousand stars, like a constellation taking shape in the Sea of Chaos.

Percy dove into her and split her into a million pieces, to be consumed by the cold fire of creation.

Percy dove into her and was consumed by the cold fire of creation.

Percy dove into her and landed on an Earth inhabited only by a fragment of Gaea.

Percy twisted around.

Percy sat up.

Someone once told Percy that at any given point in time, there were at least seven unrelated people that looked just like him, so he ought to rein in his arrogance lest he be replaced by his more biddable doppelganger.

It might have been Mr D.

A young man that could have passed as Percy were it not for his colourless hair and dark skin looked back at the two Percy’s with the polite attention of a person who had nowhere else to be and no knowledge why he ought to be anywhere at all.

“And you are–” Fish Percy broke into the tense silence.

Sitting cross-legged, without even a stitch of clothing to conceal his body, the piece of Gaea that had survived all of Percy’s attempts at mutilating her by transforming until it could pass as Percy himself in a black-and-white colour test, tilted his head.

“Who am I?” he asked back with an innocence that made Percy throw up a little in his mouth.

Some people might consider time travel as a boon – an opportunity to set right what went awry, to fix that which broke under not careful enough hands, to meet friends long dead and kill enemies that should have never grown this powerful.

Unfortunately, Percy wasn’t one of them.

This was Gaea’s do-over, the attempts of a homicidal goddess to remake the world according to her vision.

This was a moment in time that she’d wiped out more than seven people to reach.

Percy looked at the young, confused man beside him. The shock of white hair atop his head only exacerbated the perplexed look in his eyes.

Eyes golden as the Phlegethon, set in a face the rich brown of fertile soil.

Who am I?

Percy inhaled, counted to five, glanced at his twin from the depths, and arrived at a conclusion he dearly wished he could have avoided.

This was Gaea’s opportunity to fix the world – Percy had merely hijacked it.

“Can’t you tell?” Percy asked brightly, only the slightest hints of hysteria creeping into his voice. “You’re Percy too. Percy Jackson!”

***

Read on ao3.

Previous | Next

#pjo#perpollo#percy x apollo#fanfiction#apollo x percy#percy jackson#time travel#three Percy's#ruined labours of Hercules#the mortal the marine and the eldritch#gaea#the sand on your shores#inimical intentions#ancient greece

21 notes

·

View notes