#giant tube worm

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

oh worm? (my piece for the fathoms mermay anthology zine!!)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

🪱 #InsertAnInvert2024

April Theme: Wormification

-Long and Limbless: Shipworm (Teredinidae)

-Long and Limbed: Giant Tube Worms (Riftia Pachyptila)

-Short and Limbless: Green Spoonworm (Bonellia Viridis)

-Short and Limbed: Horseshoe Worm (Phoronis Australis)

Can't believe its the worms that posed such a challenge for me! Such a wild month, it was so hard to choose what guys to do each week.

---

Interested in learning more about the invertebrate animals around us? Join into the year-long InsertAnInvert event organized by Franzanth, where every week a new animal is spotlighted! Draw unique animals, read up on cool facts, or just follow the tag online to see a lot of cool artwork.

---

Like my work? Visit my shop, or support me on Ko-Fi!~

#cuttledreams#insertaninvert2024#shipworm#giant tube worm#green spoonworm#horseshoe worm#teredinidae#riftia pachyptila#bonellia viridis#phoronis australis

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fish of the Day

Today's fish of the day is the giant tube worm!

The giant tube worm, known by scientific name Riftia pachyptila is a common marine invertebrate. Unlike the common ship parasite of the same name, this animal is found in the deep sea, only discovered in 1977 when exploring the hydrothermal vents off the Galapagos islands in the rift nearby. The range of the tube worm is concentrated at rifts and trenches formed by tectonic plates around the world, and although they are theorized to possibly be in other areas of the world, they have only been recorded in the Pacific and Indo-Pacific oceans. Living anywhere from 2,564 - 2,673 Meters of depth (8,412- 8,770 feet) these animals have a life that is irreparable tied to the hydrothermal vents they concentrate around.

Due to their scarcity, hydrothermal vents are often misunderstood. These are fissure vents along the sea bed near volcanic activity that emits extremely heated water and chemicals. This supports environments of bacteria and archaea in the deep sea that previously could not have managed in the cold waters, with the trade off that the waters near them are anywhere from 60-440 degrees celcius (140-870 degrees fahrenheit). This works particularly well for the tube worms, as they prefer to live in warmer temperatures. In fact, when there were live specimens caught in 1998, the captive worms were found to enjoy living in environments around 80 degrees Fahrenheit. These hydrothermal vents also foster the bacteria that keep adult worms alive, the Campylobacterota phylum.

The giant tube worm has a life cycle similar to many others within its family, worms start life as free swimming planktonic organisms, which swim weakly and move via rows of cilia along the outer layer of their skin. Once they find a hydrothermal vent, this is when they enter a sessile stage as a juvenile, where they will begin acquiring the bacteria around the vent within themselves. These worms have no mouth, and the bacteria is an essential part of the organism, acting as their only source of sustenance in a kind of symbiosis referred to as chemoautotrophic symbiosis. Once they are stably rooted into a colony around a vent, these worms will grow quicker than any other deep sea animal, breaking the ideas in 1977 about how slow life in the deep sea was. They can grow around 1.5 meters within less than 2 years, reaching a total or 2 meters or 6.6ft total, giving them the fastest growing rate of any marine invertebrate known.

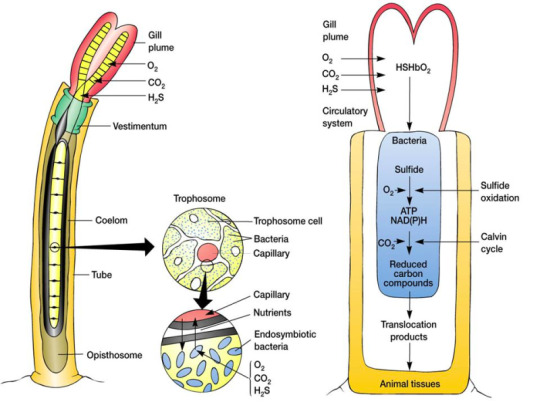

The campylobacterota takes root in the tube worms similar to an infection, through the skin. This bacteria will then bloom inside of its host, starting at what was once the mouth and esophagus in juvenile and larvae worms, before taking place in the midgut. This bacteria will then carve out an area within the worm called the Trophosome cavity, and the remainder of the digestive tract fills in. This bacteria subsists off of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, from which it can create all organic compounds needed to sustain life, releasing sulfur as a waste product. It gains energy by oxidizing the inorganic sulfur in a cycle similar to the calvin cycle used for photosynthesis.

After the worm has settled into its home along the vent and has entered the symbiotic cycle with bacteria, the worm will begin growing what is referred to as a husk or a shalth around it. This is a hard chitin shell that is used to prevent predation on the internals of the worm, along with protection for the trophosome cavity within. Then, above that is the vestimentum, which are muscle bands that can be used to pull in a gill structure above in the presence of predators, this is also where the genitals can be found, and the heart. The most striking and visible section of the worm is the branchial plume. This plume is a bright red color due to the extensive hemoglobin chains within it, despite the presence of sulfides, which usually inhibit hemoglobins. These plume gill structures are used for extending into colder water where more oxygen is available, along with bringing in carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfides for the bacteria.

Reproduction of this animal is not reliant on a season or specific age, but rather to the volcanic tectonic plate activity around it. During a spawning event, males within the colony will release spermatozoa into the water, which will locate female tube worms, swimming within the husk structure and into the ovaries. In laboratory specimens, this process takes only 30 seconds, but in the wild it is thought to take much longer and survival of the spermatozoa to rely upon the hydrothermal vent. Once fertilized, eggs will grow within the worm for several months, and when the hydrothermal vent conditions are right, the eggs will be released into the water column, relying on deep sea currents and buoyancy to carry them to the pelagic layer. The life cycle begins all over again.

Have a wonderful day everybody!

#tube worm#deep sea#hydrothermal vent#giant tube worm#deep#vents#volcanic#Riftia pachyptila#fish#fish of the day#fishblr#fishposting#aquatic biology#marine biology#freshwater#freshwater fish#animal facts#animal#animals#fishes#informative#education#aquatic#aquatic life#nature#river#ocean

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

By NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Galapagos Rift Expedition 2011 - Flickr NOAA Photo Library, Public Domain

#giant tube worm#tube worm#annelid#wet [critter creature or beast] wednesday#can't edit the poll but it should be “these are”

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy MerMay.

Happy MerMay #16-20(I’m gonna be busy this weekend so I won’t be posting)

Here’s two vent dwellers in one, Giant Tube Worm/Yeti Crab and I love her hair, I’m really proud of that detail!

#art#artists on tumblr#my art#artwork#fantasy#original character#art challenge#mermay#Mer may#mermay 2024#tube worms#yeti crab#giant tube worm#mermaid#small art account

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The aquatic critter of the day is the Giant Tube Worm! They are a chemoautotrophic keystone species that lives near hydrothermal vents and feeds off of the chemicals emitted from them. They are a large food source in vent ecosystems and often support the majority of the food chain in these areas! What neat little critters :)

#aquatic#aquatic critter of the day#aquatic critter otd#marine biology#marine life#otd#🌊 otd#aquatic life#marine#worm#sea worm#tube worm#giant tube worm#hydrothermal vents

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fishuary Day 11: They're Molluscs?!?!?!

I think they still count as deep sea fish.

@fish-daily

#art#drawing#line art#ink#my art#traditional art#sketch#fish#fishuary2024#@fish daily#tube worms#deep sea fish#day 11#giant tube worm#giant tube worms#giant beard worm#mollusc#molluscs

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#giant tube worm#tube worm Tuesday#happy Tuesday#deep sea creatures#there are many benefits to being a marine biologist

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

After the crew of the Misty Bramble bought the ship from their Captain, no one took up the position of Captain. But at least Ship can look the part.

#savage worlds the last parsec#robot#ttrpg character#giant tube worm#OC: Ship#a robot based on an aquatic alien race based on riftia pachyptila#a ship of theseus#and also greece

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

me and the girlies!!! love them so much💕💕💕

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Low Tide High is mostly made up of tropical reef species, but they have a sports rivalry with Benthic Tech and there's a whole cast of deep-sea creatures they only ever see when visiting each other for football games

#low tide high#sketches#character art#marine life#anglerfish#sea angel#giant tube worm#tube worm#giant isopod#japanese spider crab

1 note

·

View note

Text

🪱 #InsertAnInvert2024

Worms: Long and Limbed

Giant Tube Worm (Riftia Pachyptila)

The bright red of their plumes comes from their hemoglobin being very close to the surface to grab nutrients and oxygen!

------

Interested in learning more about the invertebrate animals around us? Join into the year-long InsertAnInvert event organized by Franzanth, where every week a new animal is spotlighted! Draw unique animals, read up on cool facts, or just follow the tag online to see a lot of cool artwork.

Prompt List: https://bsky.app/profile/franzanth.bsky.social/post/3khyob3xn742q

------

Like my work? Visit my shop, or support me on Ko-Fi!~

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wet Beast Wednesday: giant tube worms

You voted that I would talk about a worm and so I shall discuss the mighty giant tube worms. But first, we need to define what a tube worm is. This is another "no such thing as a fish" situation because there are actually a lot of different things we call tube worms. Turns out the "noodle in a tube" body plan is a pretty successful one. The worms I'm discussing today are members of Siboglinidae, a family of annelids (segmented worms) that was formerly classified as two different phyla until genetic evidence came in. I will primarily be talking about two species: Riftia pachyptila and Lamellibrachia luymesi, who have both adapted to distinct extreme environments in similar ways.

(Image ID: multiple patches of Riftia pachyptila growing from rock at a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. The worms are housed in long, white tubes, some stained yellow. Emerging from the tubes are respiratory organs covered in what appears to be red fur. End ID)

All members of Siboglinidae share a basic body plan consisting of a worm body inside of a mineral tube (side not, I think I will be including an orc or ogre named Sibog in my D&D campaign). The tube is composed of chitin and minerals and is secreted through glands along the body of the worm as it grows from larva to adult. The tube provides the worm within with protection from predators and environmental hazards while also providing support, allowing the worm to lift itself up into the water rather than remain on the substrate. The tube either connects to a solid object or is rooted in the sediment with extensions called roots. The roots are composed of the same material as the tube and can be considerably longer than the rest of the worm, though they are so fragile it is hard to study them. Since the worms often live in large congregations, their roots can twist together is massive mats called ropes. The inside of the tube is where you get into the squishy worm parts. The body of the worm is divided into four regions. The first of these regions I found many alternate names for while researching including cephalic lobe and branchial plume. I'm going to simplify and call it the plume because this segment is composed of one to 200 tentacles that are covered with feathery filaments that can make it look like the plume of a quill pen. The feathery portions of the plume are usually red because they are highly vascularized and filled with blood, similar to a fish's gils. The plume is used for respiration, taking in dissolved oxygen and (depending on the species) other dissolved gasses from the water. In most species, the plume is the only part of the body that extends from the tube. When in the presence of threats, the plume can withdraw into the tube, which can then be close with a structure called the obtraculum, similarly to the operculum found in many other invertebrates like snails. The second body region is the vestimentum. It has a winged shape and is composed of multiple bands of muscle. The vestimentum also contains the heart, a simple brain, and genital pores that release gametes. The third body region, which makes up most of the body, is the trunk. The trunk is the wormiest part of the worm and contains the gonads, the coelom (main body cavity), and the trophosome, which I will come back to later. The last body region is the opistosome, which connects the animal to the tube and is used to store and (maybe) excrete waste.

(Image ID: the tubeworm Lamellicrachia satsuma removed from its tube to show its anatomy. It has a plume made up of multiple feathery white tentacles, the vestimentum is a thick white section with flared tips, the trunk is long, brown, and wormlike, and ends with the yellowish opistosome. The body regions are labeled as "op" for opistosome, "tr" for trunk, "ves" for vestimentum, and "ten" for the plume. End ID. Source)

You'll notice that I didn't mention a digestive tract above. That's because these worms don't have one. Instead of a digestive tract, they have a trophosome, an organ composed of highly spongy tissue vascularized by two main blood vessels. Housed within the trophosome is a colony of bacteria that exists in a mutualistic symbiotic relationship with the worm. The worm provides the bacteria with a place to live and protection from predators while the bacteria provide the worm with all of its nutrition. The bacteria are all chemoautotrophs, gaining all their nutrition from chemical reactions using chemicals in their environment without needing to intake nutrients. In particular, they use oxygen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide provided to them by the worm. The worm also provides other elements including nitrogen and phosphorus that the bacteria need. I'm going to be honest with you, I tried to comprehend the chemical reactions involved but it's been a long time since I took chemistry and I was never that good anyway so it's over my head. The short version is that the bacteria produces nutrients and chemicals (primarily carbohydrates and ATP) that it shares with the worm. Waste products are also sent into the worm's bloodstream and are sequestered at the opistosome.

(Image ID: a scientific diagram of the internal anatomy of Riftia pachyptila. Of note is the section showing the trophosome, illustrating it as several yellow, spongy cells filled with bacteria and fed by a capillary. End ID. Source)

The most famous of the tube worms is Riftia pachyptila, which you will recognize if you have ever seen a documentary about the deep sea. They're the ones that look like giant tubes of lipstick. These are the most studied of the Siboglinids and live around hydrothermal vents in the deep pacific ocean. Hydrothermal vents are places on the seafloor where water underground is heated by geothermal activity in the Earth's mantle and then released into the water column, often carrying with it chemicals from deeper in the planet. These vents are hotspots of biodiversity in the deep sea and are hypothesized to play a major role in the origin of life. These ecosystems are among the only ones on the planet where the primary source of energy is not sunlight via photosynthesizing organisms. Instead, chemosynthetic bacteria forms the base of the trophic web, generating energy from the heat and chemicals released by the vents. Riftia requires vents which release sulfur into the water and blanket vents with the right conditions all throughout the Pacific. The lifestyle clearly works for them as they have the fastest grown rate of any marine animal. They can go from a larva to a sexually mature adult of 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) long in 2 years. These worms can reach 3 meters in length (9.75 ft) long, but only get to about 4 cm (1.5 in) in diameter within the tube. When reproducing, males will release blobs of stuck-together sperm called spermatozeugmata that collectively swim towards female worms, entering the tube and seeking out the female's oviduct. The female then releases fertilized larvae into the water. These larvae usually spend a few days in the water column before settling down on the substrate and beginning growth into an adult. However, the larvae have been known to reach newly-formed hot vents up to 200 kilometers away from their parent's vents. We don't know how the larvae find new sites to colonize or how long they can remain in the initial, motile state before succumbing to starvation as the larvae do not have digestive tracts and do not develop their internal bacterial colony until they settle down on the substrate. Once the larva does settle down, it develops its internal colony by intaking bacteria from the water using the plume. Riftia are some of the first organisms to colonize a new vent and play a major role in building that vent's ecosystem. Genetic tests show low genetic diversity amongst and between all colonies, which may be a result of how fast they colonize new vents and the fact that if a vent goes dormant or dies, all of the local worms will die with it.

(Image ID: a cluster of Rifita tubeworms, most of whom have their red, feathery plumes exposed. Some tubes do not have exposed plumes, indicating that either the worm has retracted into the tube or the worm has died. Several crabs are crawling on the tubes. End ID)

The other giant tube worm species I'm spotlighting is Lamellibrachia luymesi. These aren't as flamboyant as Riftia, but can get nearly as large (up to 3 meters) and also play a very important role in their ecosystems, though they are less studied. While Riftia likes it hot, Lamellibrachia is more chill. They live at cold seeps, places in the ocean where hydrogen sulfide and hydrocarbons like methane and oil seep out of the sea floor. Like Riftia, these worms depend entirely on an internal bacterial colony for their nutrition. Oxygen is intaken through the plume, but these worms can't get hydrogen sulfide the same way due to the different conditions. Instead, they absorb the sulfide through their roots. While the hot and cold worms absorb their hydrogen sulfide differently, they both have an adaptation to deal with it: specialized hemoglobin. Most forms of hemoglobin can't carry oxygen in the presence of hydrogen sulfide, which is a problem because that's the whole point of hemoglobin. The tube worms, who need to transport hydrogen sulfide, have specialized hemoglobin that seems to use zinc ions to allow for oxygen to bind to it anyway. The cold seep tube worms also excrete their waste products through the roots, returning it to the sediment. The intake of hydrogen sulfide and sequestering of the wast product in the roots and sediment lets the tube worms play an important role in the cold seep ecosystem. Them intaking the sulfide protects organisms who can't handle it as well and sequestering waste products also keeps it away from organisms who could be harmed by the chemicals in it. Hot vents are inherently unstable places. They are formed primarily in places where two tectonic plates are moving away from each other, exposing the planet's mantle. This exposed spot will eventually cool down and the hot vent will die off. Because of this, hot vent ecosystems grow fast and die young. Cold seeps by contrast are extremely stable and long-lasting. Lamellibrachia luymesi grow very slowly and can live for over 250 years. There's no need to hurry when your food comes out of the ground and won't be going anywhere for a very, very long time.

(Image ID: a colony of Lamellibrachia luymesi. Their tubes are more visibly segmented than those of Rifita, with the top of each segment being noticably wider than the base of the next. The tubes are a pale blue, but switch to white at 2 - 9 segments below the top. Many tubes have brown algae growing on them. The exposed plumes are short, red, and feathery. End ID)

#wet beast wednesday#tube worms#giant tube worms#Lamellibrachia luymesi#Riftia pachyptila#worm#wormblr#hydrothermal vents#cold seeps#marine biology#marine life#annelids#chemosynthesis#zoology#ecology#biology#long post#image described

115 notes

·

View notes

Note

Excuse me whomst is the little isopod in your adventure time self and gf???

thats bathtub!!

her name comes from the latin name of giant marine isopods, Bathynomus Giganteus. shes also a member of my gf's band.

#gf is out of town im watching bathtub#she keeps digging around in the cat food bowl not even eating it just like scattering it into runes......#unrelated but the first time i really flirted with my gf when we met it was because she told me the scientific name of giant tube worms is#riftia pachyptila and i was like. i need her#ez answers

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

cracking open a cold one while I crack open a book on the hydrothermal vents

7 notes

·

View notes