#fleischer studio staff

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fleischer Studios staff from 1930-1931

Vet Anderson, Andy Engman, and Ed Rehberg were formerly Fables/Van Beuren men who later moved to the west coast

Grim Natwick, James “Shamus” Culhane, Bernie Wolf, Al Eugster, & Art Turkisher all ended up going to Ub Iwerks before the other four men moved to other studios (mainly Disney)

William Henning was the inbetweening supervisor before Edith Vernick replaced him

Sam Stimson worked for Bill Nolan’s studio in New Jersey during the silent ages

Al Windley was a Harrison-Gould camera operator

Nick Tafuri, Bill Turner, Joe Stultz, Seymour Kneitel, Isadore Sparber, and Myron Waldman became Famous Studios regulars (with Seymour and Izzy also being supervisors for the studio as well)

H. Ritterband and Louis McCormick were camera operators who later moved to famous studios

Charles Schettler. Vera Coleman, Ruth Fleischer, and Edith Vernick were Inkwell studio veterans

Frank Paiker would later do camerawork for Hanna Barbera

Ted Sears later became a driving force in Disney’s story department

Sadie Friedlander later married and became Sadie Bodin, she got fired from Van Beuren during the time Burt Gillett reigned on the studio

George Cannata and Reuben Timmins (R. Timinsky here) worked in different studios Coast to Coast

Nelly Sanborn was the head of the timing department and later move on to famous studios somewhere into the ink & paint department under the name of Nelly Sanborn-Greene

Ben Shenkman would later become a prolific caricaturist/character designer for cartoons as well as assistant animator & animator

Harvey Eisenberg, Saul Kessler, & Al Geiss later became associated with TerryToons before moving to other studios (Eisenberg becoming a prominent layout artist/character designer for MGM’s Tom & Jerry and Al Geiss was involved with the Screen Gems Studio during the 40’s)

Milt Platkin would change his name to Kin Platt and become a noted story artist/scriptwriter. He’s noted for writing almost all of the Top Cat episodes for Hanna-Barbera

and Mae Schwartz was Dave Fleischer’s secretary

#fleischer studios#fleischer studio staff#staff photo#animation#golden age of animation#1930’s#1930’s animation#classic cartoons#staff#animation veterans#grim natwick#berny wolf#shamus culhane#rudy zamora#al eugster#reuben timmins#max fleischer#dave fleischer#lou fleischer#joe fleischer#seymour kneitel#isadore sparber#edith vernick#vera coleman#william henning#taken from the fabulous fleischer cartoons restored facebook banner#credit to them!!!#alongside virginia mahoney#who is related to seymour kneitel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In light of the current WGA and SAG AFTRA Strikes still going strong at well over 100 days at this point, I thought that it would be interesting to cover another strike by creative folk in Hollywood: the 1941 Disney Animators Strike.

For context, by 1941 the other major animation studios in Hollywood by this point had unionised, following the first being the 1937 Fleischer Studios Strike which produced the first union contracts, while over at Disney the studio remained a firm holdout.

However, due to a series of incidents, including Disney not following through on the promise to share profits from the phenomenally successful Snow White (trade papers at the time reported that Disney’s studio was going to distribute an estimated 20% of Snow White’s earnings among the studio’s 800 employees, the actual bonuses those artists received were equal to or less than what they had previously received for the studio’s short films, with some Snow White animators, including Art Babbitt, did not receive any bonuses for their work), the alienating behaviour of Gunther Lessing (the lawyer responsible for Disney copyrighting Micky Mouse), and other factors (such as Disney's management style consisting of playing favourites, stealing credit and so on) understandably led to tensions rising within the company.

Things came to a head in 1941, when Art Babbitt, his highest-paid animator, resigned as president of the Disney company union to join the Animation Guild. After Disney fired Art in retaliation three days later, the strike was on.

The strike went on for five weeks, and destroyed the somewhat communal atmosphere some felt that the studio had amongst its staff at the time. Support came in the form of labour organiser Herbert Sorrell, a former boxer, who had successfully lead some other Hollywood strikes, including one with the Screen Actors Guild in the mid-1940s that brought him into conflict with their president, a man by the name of Ronald Reagan.

A notable incident involving Sorrell came when rumours of hired goons were coming to break the strike, leading to Sorrell send a gang of Lockheed aircraft mechanics with monkey wrenches to guard the tents of the striking animators which were pitched on the land across from the Disney Studio. It turned out to be merely a rumor and no damage was done, although Walt did reportedly almost get into a fight with Art

Eventually, FDR ended up having to send a federal negotiator to resolve the dispute, where they found in favour of the strikers in every issue. Disney, for his part, reportedly had been nearing a mental breakdown over the animators' "betrayal" left on a tour of Latin America to try and ease tensions.

Disney never forgave the strikers for the strike, and would maintain for years that rather than it being due to any mismanagement on his part, it was due to the animators being infiltrated by communists. Specifically, Herbert Sorrell, whom Disney would later report to the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 as a communist infiltrator who was trying to turn his employees against him.

Y'know, so he learned nothing.

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Superman and Gigantic the Ape have crashed to the ground as they battle beneath the big top!

Their fall has torn loose electric wires, which spells disaster in a canvas tent with a floor of sawdust!

The Man of Steel battles to subdue the enraged ape while the fire spreads around them!

Once again Superman has saved the day!

Later, back at the Daily Planet...

Clark: “Lucky Lois! Always gets her story.”

Lois: “And, luckily, she lived to write it.”

Clark: “Thanks to Superman?”

Sadly, this was the last Superman cartoon, or any other cartoon, produced by Fleischer Studios.

The animation studio, which had been in business for more than twenty years, was taken over- for a number of reasons - by Paramount Pictures and renamed Famous Studios. It is under that name that the last eight Superman cartoons were produced.

Max and Dave Fleischer, who’d been feuding for years by the time the Superman series began production in 1941, and only communicating with each other via memo, were removed from the company that bore their name.

Although the majority of the Fleischer Studios staff stayed onboard after the takeover, there was a change in the tone of the Superman series for the final eight episodes. Paramount had been trying to dictate the story content from the beginning, and now with the Fleischer brothers no longer running interference Paramount would finally get its way.

This final cartoon, Terror on the Midway, is not up to the standards the earlier cartoons had. The production seems to have been rushed, with the animators taking many short-cuts: action depicted in shadow or silhouette, characters and movement obscured by objects in the foreground, extreme close-ups of characters that make it difficult to follow the action, and only the lower half of characters being seen (so there were no faces to animate!). But even given all that, it’s still better than 99% of any other cartoons made!

The Fleischers’ story is a fascinating portrayal of the American animation industry in its infancy. I encourage everyone to read the numerous excellent sources on the Interweb, as well as the book Out of the Inkwell (2005) by Richard Fleischer (Max’s son, and also the director of the films 20,000 Leagues under the Sea [Disney version], Tora! Tora! Tora! and Soylent Green).

#Superman#Terror on the Midway#Clark Kent#Lois Lane#Fleischer Studios#Out of the Inkwell#Max Fleischer#Dave Fleischer#cartoons#animation

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Night 65: Rotoscopy!

Hello friends! It is a multiple of 5 tonight, which means, according to my arbitrary definitely-always-followed schema, tonight is a theme night focused on some kinda animation technique... and tonight, that means the rotoscope!

So what is a rotoscope? In the modern day, the term refers generally to drawing over live action footage with animation - very easy to do in the digital era!

But in its original form, the rotoscope was actually a contraption built by Max Fleischer to enable him and his animators to accomplish that in the era of physical film...

...by projecting the film behind the drawing surface to shine through the paper. With this technique, the Fleischer brothers were able to create some of their most world-known films, starting with shorts like Out of the Inkwell and eventually reaching the Cab Calloway performances we talked about back on Animation Night 21.

Before long, the contraption would find its way into the hands of Disney. In The Illusion of Life, the book that declared the ‘12 principles of animation’, Thomas and Johnson discuss starting on page 318 how it was used in the earlier days of the studio: while trying to figure out how best to express the character of Dopey the dwarf in Snow White, someone suggested that they should look at the performance of burlesque comedian Eddie Collins. The animators piled into the theatre, then invited him to the studio to perform interpretations of the character, which they filmed and used to inform their animation.

This worked so well that they started inviting “entertainers from vaudeville, men who had done voices for the other dwarfs” as well as filming random members of Disney staff. They write:

As resource material, it gave an overall idea of a character, with gestures and altitudes, an idea that could be caricatured. As a model for the figure in movement, it could be studied frame by frame to reveal the intricacies of a living form's actions.

At first, these frame by frame studies were done using a Fleischer-style rear-projection rotoscope; before long they developed a system of printing out the films onto ‘photography paper the same size as our drawing paper’ called photostats. There’s a very cool passage where they get excited at what could be discovered in there...

We were amazed at what we saw. The human form in movement displayed far more overall activity than anyone had supposed. It was not just the chest working against hips, or the backbone bending around, it was the very bulk of the body pulling in, pushing out. stretching, protruding. Here were living examples of the “squash and stretch” principles that only had been theories before. And here was the “follow through” and the “overlapping action,’’ the changing shapes, the tensions and the counter tensions, the weight shown in the “timing,” and the “exaggeration”—unbelievable exaggeration. We thought we had been drawing broad action, but here were examples surpassing anything we bad done. Our eyes simply are not quick enough to detect the whole gamut of movement in the human figure.

youtube

So at this stage, Disney primarily used these studies as reference to be interpreted and developed by the animator, rather than directly copied. And they also discovered the peril of rotoscoping, a certain uncanny lifelessness:

But whenever we stayed too close to the photostats, or directly copied even a tiny piece of human action, the results looked very strange The moves appeared real enough, but the figure lost the illusion of life. There was a certain authority in the movement and a presence that came out of the whole action, but it was impossible to become emotionally involved with this eerie, shadowy creature who was never a real inhabitant of our fantasy world.

(...)

The camera certainly records what is there, but it records everything that is there, with an impartial lack of emphasis. On the other hand, an artist shows what he sees is there, especially that which might not be perceived by others.

Disney made increasing use of live reference over time, since it proved a useful way to plan out and judge shots in the early stages. This had its pitfalls...

Unless a director is exceptionally wise, or an animator himself, he should ask the man* who ultimately will animate the scenes to help plan the business on the stage. Almost always when someone else shoots film for an animator the camera is too far back, or too close, or the action is staged at the wrong angle to reveal what is happening, or it is lighted so that what you want to see is in shadow. Occasionally the footage will show only continuity of an actor moving from one place to another, or just waiting, or getting into position to do something interesting later on. The action must be staged with enough definition and emphasis to be extremely clear, but neither overacted nor so subtle that it fails to communicate.

(*this would have been a man, because old Walt banned women from being animators - we would have been restricted to the ink and paint department up until Reidun “Rae” Medby was first permitted to work as an assistant animator in 1944, in the wake of the animators’ strike and a lot of animators going off to war after the Pearl Harbour bombing.)

By the time of Cinderella, a cash-strapped Walt decided he needed another feature film to pay for the not-yet-profitable Pinnochio, Fantasia and Bambi. (Strange to imagine Disney ever struggling for money, but it wasn’t quite the monster it became back then.) To save as much effort for the animators as possible, he shot basically the entire film in live action, which was closely followed by the animators:

A new, less expensive way to make the projected Cinderella as a full-fledged animated feature had to be found. Reasoning that animation was the most costly part of the business, Walt felt that everything possible should be done to save the animator’s lime, to help him make that first test "OK for cleanup" without correction. He turned to live action to solve his problem.

All of Cinderella was shot very carefully with live actors, testing the cutting, the continuity, the staging, the characterizations, and the play between the characters, Only the animals were left as drawings, and story reels were made of those skelehes to find the balance with the rest of the picture. Economically, we could not experiment; we had to know, and it had to be good. When all of the live film was spliced together, this was undeniably a strong base for proving the workability of the scenes before they were animated, but the inventiveness and special touches in the acting which had made our animation so popular were lacking. The film had a distinctly live action feel, but it was so beautifully structured and played so well that no one could argue with what had to be done. As animators we felt restricted, even though we had done most of the filming ourselves, but the picture had to he made for a price, and this was, undeniably; a way of doing it.

The extent of rotoscoping in Disney films has always varied; after Cinderella they continued to use live footage for films like Peter Pan, but would interpret it more creatively. A lot of this close study of film was applied to animals. For The Lion King, they actually brought real lions into the studio, so you get these very cute videos of a baby lion being led between a row of drawing desks and getting petted by the animators (skip to 1:35...)

youtube

So that’s Disney. They had a particular way of using rotoscopy. Later they’d use live footage in different ways - with 101 Dalmations, they actually drew lines on a toy car and filmed it, then xeroxed the film, to create what appeared to be a line drawing.

In the 70s, as a few people started to escape the Disney orbit and their somewhat stifling house style, animators like Ralph Bakshi also got the rotoscopy bug, in part as a way to create animation with limited costs. We saw the results a couple of weeks ago in Wizards and Lord of the Rings (as well as American Pop and Fire and Ice which we haven’t seen yet). The former of these did some pretty wild experimental techniques, such as xeroxing war scenes from existing movies - resulting in a delirious, dreamlike battle sequence. For LotR, almost all shots were either rotoscoped or solarised video footage; presumably a fully live-action cut of the film could be made from all the test footage.

The results of Bakshi’s experiment were... mixed. At its best, the rotoscopy in LotR gives its characters a great degree of weight and solidity appropriate to a more ‘serious’ fantasy movie. The decision to solarise video footage for the battle scenes, or the really long chase sequence in the middle of the movie, is a fun and vivid experiment... but it’s no surprise it didn’t catch on.

Don Bluth (Animation Night 23 - animals, 31 - hanukkah) also used rotoscopy in his films The Secret of NIMH and An American Tail, as well as the same xerox trick as 101 Dalmations for semi-stylising physical objects. This ends up much more successful on the whole: while the physical objects stood out, they work as a particular style, while none of the character animation seemed ‘obviously rotoscoped’. On the donghua side (Animation Night 27), rotoscopy was used in Princess Iron Fan. And through the latter half of the 20th century, there were many other films using the technique which I’ve yet to cover, which you can read about over on WP.

20th-century rotoscoping tended, with some exceptions like Yellow Submarine, to aim for something approximating traditional Disney-style animation with flat colours and caricatured designs. In anime, rotoscoping does not seem to have been especially common, likely because the generally limited drawing counts really force a different approach to timing than strict realism.

All of this changed as we approached the 2000s. In the West, MIT researcher and frequent Liquid Television animator Bob Sabiston developed a program called Rotoshop that eased the work of rotoscoping by interpolating between drawings. (We might compare this with EBSynth, which requires only a few frames to stylise a whole video sequence - Rotoshop on the other hand takes a much more granular artist-controlled approach, but it is consequently more time consuming).

Sabiston’s software caught the attention of live-action director Richard Linklater, who used it in two films, Waking Life (2001) and an adaptation of Philip K Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly (2006). These films proved pretty popular in arthouse circles, and the clips show a striking effect, with the shading of the face simplified into shifting vector shapes that’s very consciously uncanny.

Over in Japan, in 2013 Hiroshi Nagahama and studio Zexcs experimented with adapting the manga The Flowers of Evil into a fully rotoscoped anime TV series. The result is an anime that looks very unlike typical anime: characters constantly moving and breathing and rotating subtly in 3D space. This seems to have been extremely polarising: some critics lavished praise on its cinematography and unusual style, but it also caught a lot of flack for cutting corners.

A second anime attempt at rotoscoping arrived a couple years later in Shunji Iwai’s film The Case of Hana and Alice, a prequel to his 2004 live-action film Hana and Alice. This one seems to have landed a lot better, with rotoscoping allowing them to portray what would otherwise be extremely difficult scenes like this roomful of dancers:

It’s very interesting looking at these clips: the style leads me to read them as traditional animation, and then is immediately struck by the perfect perspective and weighty movement of cloth and bodies - I get that “how could anyone have...” feeling. That is perhaps the great power of rotoscoping: it allows us to look at things that would otherwise be everyday and see the fascinating complexity of motion going on at every moment...

One thing that strikes me about both of these films is that both use a kagenashii (flat-shaded) style, much like the films of Mamoru Hosoda. The same is true of Bakshi’s LotR. This makes the characters fit oddly into the scenes: exceptionally 3D the subtle changes of contour, but shaded perfectly flat. It’s a nice effect but I wonder why so many rotoscoped films ended up here? Perhaps it is much more difficult to draw out shadow shapes on a frame by frame basis than the obvious contours of a character...

Rotoscoping has also been used occasionally in other animated films, such as the beautiful dance scene in Your Name by the young Naoko Kawahara. There are also some rather amusing cases, like the idol anime Love Live quietly rotoscoping multiple shots from the American live-action musical show Glee.

The next major film experiment in rotoscoping came in 2017, a biopic of Vincent van Goph directed by Polish filmmakers Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman. Kobiela is a painter herself, and got the seemingly mad idea of making a film that is entirely Van Goph-style oil paintings shot on 2s, making for 65,000 drawings over a 90 minute film. They took this idea to Kickstarter and the usual European art funds, and, wildly, actually made it work. The result is characters that move with all the subtlety of real film, but with the beautiful textures and abstraction of impressionism.

The production involved a multi-step process: CG animation and live footage would be composited together to get a close approximation of the intended frame, and then it would be fully repainted by a team of 80 oil painters. The various shots of the film are composed after van Goph paintings, but many edited to change the time of day or adjust the framing from one of Goph’s vertical compositions.

Anyway, even for a really skilled oil painter with a good reference, I can only imagine how difficult it must have been to keep the subtleties of each painting consistent frame to frame. It landed at Annecy to enormous acclaim. Judging by the short films at Annecy this year, this kind of paint-rotoscoping seems to have taken off since then, to somewhat varied effect. While For their part, the makers of Loving Vincent are currently creating another oil paint rotoscoped film titled The Peasants...

youtube

This technique has some similarities to the paint-on-glass method made famous by the Russian animator Aleksandr Petrov, but while paint-on-glass is destructive, overwriting each frame with the next creating a situation where frames blend into one another, I believe the method of Loving Vincent is to create an entirely original oil painting for every frame. (I presume they have some digital trick to help them composite it onto the backgrounds, which seem to remain static).

So, what’s the plan tonight? We’re going to check out The Case of Hana and Alice and Loving Vincent, one or two episodes of The Flowers of Evil, and a few of the shorts by Bob Sabiston. That certainly doesn’t cover the whole story with rotoscoped films, but I think it should give us a nice little cross-section!

Animation Night 65 will begin at 7pm UK time (about three and a half hours) at twitch.tv/canmom. Hope to see you there!

41 notes

·

View notes

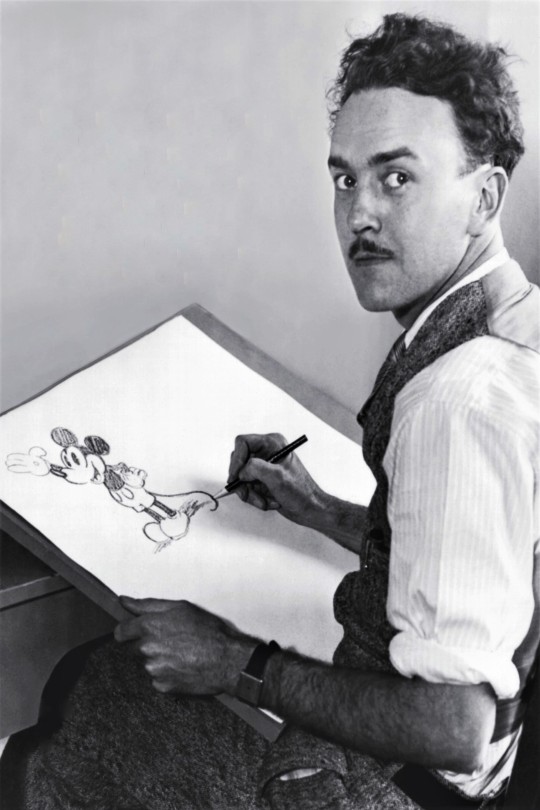

Photo

Ubbe Eert "Ub" Iwwerks was born on March 24, 1901. He was an American animator, cartoonist, character designer, inventor, and special effects technician, who designed Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and Mickey Mouse. Iwerks produced alongside Walt Disney and won numerous awards, including multiple Academy Awards.

Iwerks spent most of his career with Disney. The two met in 1919 while working for the Pesmen-Rubin Art Studio in Kansas City, and eventually started their own commercial art business together. Disney and Iwerks then found work as illustrators for the Kansas City Slide Newspaper Company (which was later named The Kansas City Film Ad Company). While working for the Kansas City Film Ad Company, Disney decided to take up work in animation, and Iwerks soon joined him.

He was responsible for the distinctive style of the earliest Disney animated cartoons, and was also responsible for designing Mickey Mouse. In 1922, when Disney began his Laugh-O-Gram cartoon series, Iwerks joined him as chief animator. The studio went bankrupt, however, and in 1923 Iwerks followed Disney's move to Los Angeles to work on a new series of cartoons known as “the Alice Comedies” which had live-action mixed with animation. After the end of this series, Disney asked Iwerks to design a character that became Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. The first cartoon Oswald starred in was animated entirely by Iwerks. Following the first cartoon, Oswald was redesigned on the insistence of Oswald's owner and the distributor of the cartoons, Universal Pictures. The production company at the time, Winkler Pictures, gave additional input on the character's design.

In spring 1928, Disney was removed from the Oswald series, and much of his staff was hired away to Winkler Pictures. He promised to never again work with a character he did not own. Disney asked Iwerks, who stayed on, to start drawing up new character ideas. Iwerks tried sketches of frogs, dogs, and cats, but none of these appealed to Disney. A female cow and male horse were created at this time by Iwerks, but were also rejected. They later turned up as Clarabelle Cow and Horace Horsecollar. Ub Iwerks eventually got inspiration from an old drawing. In 1925, Hugh Harman drew some sketches of mice around a photograph of Walt Disney. Then, on a train ride back from a failed business meeting, Walt Disney came up with the original sketch for the character that was eventually called Mickey Mouse. Afterward, Disney took the sketch to Iwerks. In turn, he drew a more clean-cut and refined version of Mickey, but one that still followed the original sketch.

The first few Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies cartoons were animated almost entirely by Iwerks, including Steamboat Willie, The Skeleton Dance and The Haunted House. However, as Iwerks began to draw more and more cartoons on a daily basis, he chafed under Disney's dictatorial rule. Iwerks also felt he wasn't getting the credit he deserved for drawing all of Disney's successful cartoons. Eventually, Iwerks and Disney had a falling out; their friendship and working partnership were severed in January 1930. According to an unconfirmed account, a child approached Disney and Iwerks at a party and asked for a picture of Mickey to be drawn on a napkin, to which Disney handed the pen and paper to Iwerks and stated, "Draw it." Iwerks became furious and threw the pen and paper, storming out. Iwerks accepted a contract with Disney competitor Pat Powers to leave Disney and start an animation studio under his own name. His last Mickey Mouse cartoon was The Cactus Kid. (Powers and Disney had an earlier falling-out over Disney's use of the Powers Cinephone sound-on-film system—actually copied by Powers from DeForest Phonofilm without credit—in early Disney cartoons.)

The Iwerks Studio opened in 1930. Financial backers led by Pat Powers suspected that Iwerks was responsible for much of Disney's early success. However, while animation for a time suffered at Disney from Iwerks' departure, it soon rebounded as Disney brought in talented new young animators.

Despite a contract with MGM to distribute his cartoons, and the introduction of a new character named “Flip the Frog”, and later “Willie Whopper”, the Iwerks Studio was never a major commercial success and failed to rival either Disney or Fleischer Studios. Newly hired animator Fred Kopietz recommended that Iwerks employ a friend from Chouinard Art School, Chuck Jones, who was hired and put to work as a cel washer. The Flip and Willie cartoons were later distributed on the home-movie market by Official Films in the 1940s. From 1933 to 1936, he produced a series of shorts (independently distributed, not part of the MGM deal) in Cinecolor, named ComiColor Cartoons. The ComiColor series mostly focused on fairy tales with no continuing character or star. Later in the 1940s, this series received home-movie distribution by Castle Films. Cinecolor produced the 16 mm prints for Castle Films with red emulsion on one side and blue emulsion on the other. Later in the 1970s Blackhawk Films released these for home use, but this time using conventional Eastmancolor film stock. They are now in the public domain and are available on VHS and DVD. He also experimented with stop-motion animation in combination with the multiplane camera, and made a short called The Toy Parade, which was never released in public. In 1936, backers withdrew financial support from the Iwerks Studio, and it folded soon after.

In 1937, Leon Schlesinger Productions contracted Iwerks to produce four Looney Tunes shorts starring Porky Pig and Gabby Goat. Iwerks directed the first two shorts, while former Schlesinger animator Robert Clampett was promoted to director and helmed the other two shorts before he and his unit returned to the main Schlesinger lot. Iwerks then did contract work for Screen Gems (then Columbia Pictures' cartoon division) where he was the director of several of the Color Rhapsodies shorts before returning to work for Disney in 1940.

After his return to the Disney studio, Iwerks mainly worked on developing special visual effects. He is credited as developing the processes for combining live-action and animation used in Song of the South (1946), as well as the xerographic process adapted for cel animation. He also worked at WED Enterprises, now Walt Disney Imagineering, helping to develop many Disney theme park attractions during the 1960s. Iwerks did special effects work outside the studio as well, including his Academy Award nominated achievement for Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (1963).

Iwerks' most famous work outside creating and animating Mickey Mouse was Flip the Frog from his own studio. According to Chuck Jones, who worked for him, "He was the first, if not the first, to give his characters depth and roundness. But he had no concept of humor; he simply wasn't a funny guy."

Iwerks was born in Kansas City, Missouri. His father, Eert Ubbe Iwwerks, was born in the village of Uttum in East Frisia (northwest Germany, today part of the municipality of Krummhörn) and immigrated to the United States in 1869. He is the father of Disney Legend Don Iwerks and grandfather of documentary film producer Leslie Iwerks.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movie Odyssey Retrospective

Fantasia (1940)

With production on Bambi postponed, Walt Disney dedicated himself to Pinocchio (1940) and a film featuring animated segments accompanying classical music. Walt’s demands for innovation saw Pinocchio’s budget skyrocket, and the film left Walt Disney Productions (today called Walt Disney Animation Studios) on unstable financial grounds. This laid impossible financial expectations for the latter film – tentatively entitled The Concert Feature – to meet. War halted the possibility of cross-Atlantic distribution as Walt continued to emphasize innovation for each of his features and workplace tensions rose among his animators. What was planned as a glorified Mickey Mouse short set to Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – Mickey’s popularity was flagging by the mid-1930s, trailing other Disney counterparts and Fleischer Studios/Paramount’s Popeye the Sailor – grew to include seven other segments. The film that became known as Fantasia remains the studio’s most audacious work. Though it built off the visual precedents of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the volume of artistry for artistry’s sake contained in Fantasia, eighty years later, remains unsurpassed.

After the Philadelphia Orchestra’s conductor/music director Leopold Stokowski offered to record The Sorcerer’s Apprentice for free (he did so with a collection of Hollywood musicians; the English-Polish conductor, a rare conductor who spurned the baton, was among the best of his day), cost overruns on The Sorcerer’s Apprentice led to its expansion as a feature. To provide commentary as Fantasia’s Master of Ceremonies, the studio sought composer and music critic Deems Taylor – who came to Disney and Stokowski’s attention in his role as intermission commentator for radio broadcasts of New York Philharmonic concerts. But both Disney and Stokowski were too busy during the summer of 1938 to brief Taylor on their plans. Stokowski spent that summer in Europe seeking permission for the rights to use certain pieces from various composers’ families (this included visits to Claude Debussy’s widow and Maurice Ravel’s brother); Disney was occupied with the construction of the Burbank studio. After Stokowski returned from Europe in September, Disney asked Taylor to come to Los Angeles to formally discuss Fantasia. Taylor agreed, arriving one day after Stokowski and Disney began their meetings, staying in Southern California for a month.

Over several weeks that September, Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made the final selections for pieces – suggested by story directors Joe Grant and Dick Huemer (both worked on 1941’s Dumbo and 1951’s Alice in Wonderland) – to be featured in Fantasia. Hours were spent listening to classical music recordings, followed by brainstorming potential visualizations. The meetings were recorded by stenographers, with transcripts (housed at the Walt Disney Archives in Burbank) provided to all three participants. During these meetings, Walt mostly listened to Stokowski and Taylor consider every suggestion by Grant and Huemer:

DISNEY: Look, I really don’t know beans about music. TAYLOR: That’s all right, Walt. When I first started, I thought Bach wrote love stuff – like Romeo and Juliet. You know, I thought maybe Toccata was in love with Fugue.

During these meetings, an admiring Walt – in addition to gifting a potential last hurrah for Mickey Mouse and to create a film unrestrained by commercial demands – realized he wanted to create a gateway to classical music for those who might not otherwise give such music a chance. Always leading his writing staff in developing stories, Walt felt relieved that he could share this responsibility with Stokowski and Taylor. Free of the storytelling stresses plaguing the Pinocchio and Bambi productions at the time, these tripartite meetings were not beholden to narrative cohesion, allowing the participants to suggest anything that their imaginations conjured. Without the constraints of narrative logic or predictions about what an audience wanted to see, Fantasia became the center of Walt Disney’s passion until its completion.

Nine selections were made by the trio, with one piece later being dropped entirely (Gabriel Pierné’s Cydalise and the Satyr) and another being replaced after its completion. A completed segment for Debussy’s Clair de Lune* was substituted out for Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (the mythological scenario Walt envisioned for the Pierné reverted to the Beethoven, but more on this later). Over the next few years, Disney’s animators would complete the artwork; Stokowski would study, arrange, and record the selections with the Philadelphia Orchestra (except for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which had already been recorded); Taylor would write his introductions to be filmed at the Disney studios.

In almost all of cinema, music accompanies and strengthens dramatic or comedic visuals. Fantasia is the reverse of this relationship. The animation provides greater emotional power to the music – an arrangement that may be startling to viewers unfamiliar with or disinclined to classical music or cinematic abstraction. Fantasia’s opening scenes and piece introductions feature the affable Taylor, who outlines the film’s conceits:

TAYLOR: Now there are three kinds of music on this Fantasia program. First, there’s the kind that tells a definite story. Then there’s the kind that, while it has no specific plot, does paint a series of more or less definite pictures. And then there’s a third kind, music that exists simply for its own sake.

That last kind, also known as “absolute music”, opens Fantasia with Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, an organ piece arranged for orchestra (“Toccata” and “Fugue” refer to the musical forms of the piece’s two halves). As James Wong Howe’s (1934’s The Thin Man, 1963’s Hud) gorgeous live-action cinematography of the orchestra (the Toccata) transitions to animation (the Fugue), the audience witnesses Walt Disney Animation’s first, and arguably only, foray into abstract animation – as opposed to abstract stylizations to bolster a macro-narrative – for a feature film. The Toccata and Fugue is a pure visualization of listening to music, as if the animation was improvised. The sequence involves, among other things, string instrument bridges and bows flying in indeterminate space, figures and lines rolling across the screen, and beams of light and obscured shapes timed to Bach’s piece. In these opening minutes, Fantasia announces itself as a bold hybrid of artistic expression in atypical fashion for Disney’s animators.

Next is The Nutcracker Suite by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, which is subdivided into six dances (“Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy”, “Chinese Dance”, “Arabian Dance”, “Trepak”, “Dance of the Reed Flutes”, “Waltz of the Flowers” – these dances are placed out of order, and the “Miniature Overture” and “Marche” which open the suite are not present). Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made this selection decades before Tchaikovsky’s now-most famous ballet became a Christmas cliché in the United States – it was barely performed in the early twentieth century and is usually regarded, among classical music experts and by the composer himself, as a lesser Tchaikovsky ballet.

History aside, this animated treatment of The Nutcracker utilizes an astonishing array of different animation techniques across all six dances. With The Nutcracker, the Disney animators, for the first time, take a piece with a preexisting story, animate sequences adhering to the music’s essence, yet producing images that have nothing to do with the original material. In Fantasia, The Nutcracker remains a ballet – the sugar plum fairies, racially insensitive mushrooms, fish, and flowers move as if they are on a ballet stage. But there is nothing, in the sense of a narrative through line, to connect all six dances. Set to the changing of the seasons, The Nutcracker contains gorgeously-animated fairies and intricate fish (Cleo from Pinocchio was a testing run for the “Arabian Dance”), climaxing with fractal flurries that look like an antique Christmas card brought to life. Even the racist “Chinese Dance” exemplifies masterful character design – simplicity does not preclude expressiveness. The Nutcracker’s spectacular inclusion improved Tchaikovsky’s standing and his least acclaimed ballet among casual classical music fans.

Based on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem of the same, Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice ushers in the Mickey Mouse short that overshadows all others. With the animators’ adaptation closely following Goethe’s poem, Dukas’ original piece is impossible to listen to without imagining Mickey, rogue anthropomorphic broomsticks, and thousands of gallons of water. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice marked the cinematic debut of Mickey Mouse with pupils, as designed by Fred Moore (the dwarfs on Snow White, the mermaids in 1953’s Peter Pan) – Mickey was first drawn with pupils on a program to an infamous, booze-filled party Walt Disney threw in 1938. With pupils, Mickey’s gaze provides a sense of direction that black ovals make ambiguous. The additional personality – not to say Mickey Mouse’s original character design lacked personality – thanks to the pupils strengthens Mickey’s expressions of jollity, shock, submissiveness. A lanky, stern sorcerer is Mickey’s brilliant foil. Their physical differences and reactions imbue The Sorcerer’s Apprentice with a troublemaking charm recalling Mickey’s earliest short films, sans the slapstick that defined those appearances. These decisions heralded a new era for how the Walt Disney Studios’ mascot would be animated and portrayed in his upcoming shorts.

This segment’s chiaroscuro sets a pensive atmosphere, enclosing Mickey in a black and brown gloom as he – a nominal apprentice – is tasked with menial duties, not magic. The indefinite shape of the sorcerer’s chambers owes to German Expressionism (as does the penultimate piece in Fantasia), with its impossibly curved angles and architectural fantasy hiding secrets that no sorcerer’s apprentice assigned to carry buckets of water could understand. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice tonal shifts always feel justified, rooted in the sequence’s character and production design – although, in this regard, the sequence is surpassed later in Fantasia.

Immediately following a mutual congratulations between Mickey (voiced by Disney) and Stokowski is Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky’s brief one-act ballet/piece debuted in 1913 to an audience riot because of its musical radicalism – The Rite of Spring liberally partakes in polytonality (using two or more key signatures simultaneously), polyrhythms, constant meter changes, unorthodox accenting of offbeats, chromaticism, and piercing dissonance. Concert hall attendees had heard nothing like The Rite of Spring before and, even in 1940, Stravinsky’s composition divided audiences. The Rite of Spring – precipitating the concert hall’s philosophical battles of the late twentieth and twenty-first century over whether melody and coherent rhythm still has a role to play in contemporary classical music – is a gutsy choice to present to general audiences.

At fifty-eight years old when Fantasia was released, the Russian-born, French-naturalized (and soon-to-be American citizen) Stravinsky is the only composer to have lived to see one of his pieces adapted for a Fantasia movie. Stravinsky despised Stokowski’s interpretation and cutting of his music (all musical cuts were Stokowski’s decisions, reasoning that an audience of classical music neophytes might not be comfortable in a theater for too long during Fantasia), but applauded the animated interpretation of his work. As a ballet, The Rite of Spring is about primitivism. The Disney animators sheared the piece of its human element to liberate themselves from the ballet’s narrative (and believers of creationism). Instead of portraying primitive humans, they elected to depict an account of Earth’s early natural history – its primeval violence, the beginning of life, the reign and extinction of the dinosaurs. Astronomer Edwin Hubble, English biologist Julian Huxley, and paleontologist Barnum Brown served as scientific consultants on The Rite of Spring, imparting to the animators the most widely-accepted theories within their respective scientific fields at the time.

As the camera moves towards the young Earth, Stravinsky’s piece clangs with orchestral hits emboldened by the volcanic violence on-screen – the animated flow of the lava and realistic bubble effects (studied by the animators using high-speed photography on oatmeal, mud, and coffee bubbles inflated by air hoses) are technical masterstrokes. Giving way to single-celled organisms and later the dinosaurs, the camera’s perspective keeps low, emphasizing the height of these prehistoric creatures. The suggestion of weight to the dinosaurs distinguish them from comic, cartoonish depictions in American animation up to that point. The Rite of Spring is the only Fantasia segment where I can imagine viewers unversed in classical music, but making an honest attempt to appreciate the music, being repelled for the entire passage because of the music itself. Otherwise, so ends Fantasia’s immaculate first half.

After the intermission, we meet the Soundtrack, a visual representation of the standard optical soundtrack, with Deems Taylor. It is an entertaining diversion before Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (“The Pastoral Symphony”) – accompanied by scenes of winged horses, centaurs, pans, and gods from classical mythology. These characters and backgrounds, and clear story were intended for Pierné’s Cydalise and the Satyr before its deletion from the program. Seeking a replacement piece, Disney chose Beethoven’s Pastoral over Stokowski’s objections. Stokowski, who largely dismissed potential criticisms from diehard classical music fans and encouraged Walt’s experimentation in their meetings, noted that Symphony No. 6 – the unidentical twin of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5; both were composed simultaneously and debuted to the public on the same evening in 1808 – was Beethoven’s tribute to the Viennese countryside and that, according to Beethoven’s program notes from that 1808 concert, represented, “more an expression of feeling than painting.” Beethoven’s long summer walks amid babbling brooks, verdant forests, and wildlife provided solace from his increasing deafness. Deems Taylor, acknowledging Stokowski’s citations of the symphony’s history, thought the decision a brilliant one. By simple majority, Walt’s repurposed idea for the mythological setting for the Pastoral was produced.

For the entirety of the Pastoral’s second movement, we see cupids assisting in centaur courtship. These hackneyed scenes are glacially paced, overly dependent on Fred Moore’s risqué good girl art. Fantasia’s most objectionable content also appears in the second movement in the form of crude racial caricatures of black women – though the worst example will almost certainly not be in any available modern print of Fantasia, as the Walt Disney Company has consistently cut the footage and essentially denies it ever existed. The story’s tone almost trivializes Beethoven’s Pastoral, making the seond movement a tiresome Silly Symphony. Arguably the weakest of the original Fantasia numbers (Stokowski’s criticisms justified by the final product), the Pastoral nevertheless contains an eye-catching palate of color that makes it unmissable. Encouraged by the supervising animators on the Pastoral to use as much color as possible, the throngs of artists assigned to this were up to the task. Rarely does Technicolor, in full saturation, look brighter than when the young flying horses take to the sky, centaurs and centaurettes partake in mating rituals, and an ever-inebriated Bacchus stumbles into the centaurs’ party.

From the closing ballet of Act III of Amilcare Ponichelli’s opera La Gioconda, the Dance of the Hours is the penultimate piece in Fantasia. Dance of the Hours suffers from its placement in the film. After Bacchus’ simpleminded, jolly antics in the Pastoral, this whole segment is the one that most resembles Disney’s Silly Symphony short films. Presented as a comic ballet with ostriches, elephants, hippopotamuses, and alligators, the Dance of the Hours has the ideal supervising animators assigned to it – caricaturist “T.” (Thornton) Hee and Pluto/Big Bad Wolf animator Norm Ferguson. Dancer Marge Champion (the model for Snow White’s dancing), ballerina Tatiana Riabouchinska and her husband David Lichine served as models for the balletic motions, endowing the segment with choreographic – though perhaps not biological – accuracy. As long as the viewer basks in the Dance of the Hours’ unadulterated silliness and does not mind the fact it is the least innovative piece in terms of its animation, it is an enjoyable several minutes of Fantasia.

Fantasia concludes with a staggering pairing: Modest Mussorgsky’s‡ tone poem Night on Bald Mountain (partial cuts) and Franz Schubert’s Ave Maria (with English lyrics). After an inconsistent second half to Fantasia, the film ends with two selections so remarkably contrasting in musical form and texture and animation. Night on Bald Mountain, like Dance of the Hours, is the responsibility of an ideal supervising animator in Wilfred Jackson (1937’s The Old Mill, Alice in Wonderland) and one of the finest character animators in Bill Tytla (Stromboli in Pinocchio, Dumbo in Dumbo). Using Mussorgsky’s written descriptions for the piece, the animators closely adhere to the composer’s imagined narrative. On Walpurgisnacht, a towering demon atop a mountain unfurls his wings and summons an infernal procession from the earthly and watery graves below. This demon, the Slavic deity Chernabog, is Tytla’s greatest triumph as a character animator and for all animated cinema. With movements modeled by Béla Lugosi of Dracula (1931) fame – one could not ask for a better model – and Jackson himself, Tytla captures Chernabog’s enormity, the torso’s muscular details, and graceful arm and hand movements that never falter frame-by-frame. Chernabog moves more realistically than any Disney character – in shorts and features, Rotoscoped or not – and would retain that distinction until the advent of computerized animation. In Tytla’s mastery, one forgets that Chernabog is nothing but dark paints.

Jackson’s use of contrasting styles to demarcate Chernabog from the ghosts and spirits summoned to the mountain’s summit further contributes to Night on Bald Mountain’s satanic atmosphere. The shades answering Chernabog’s call appear as either rough white pencil sketches that one might expect in a concept drawing or translucent, wavy figures animated with rippling effects that required a curved tin to complete. That rippling, wafting effect – lasting only several seconds in Night on Bald Mountain – was among the most labor-intensive parts of Fantasia, requiring animators to be present at work in multiple shifts across twenty-four hours to photograph the movements for each frame. The Walt Disney Animation Studios would not delve into such darkness again until The Black Cauldron (1985).

Night on Bald Mountain benefits from being followed immediately – without a Deems Taylor introduction (he introduces both pieces prior to the Mussorgsky) – by Schubert’s Ave Maria, and vice versa. As Chernabog and the spirits romp, an Angelus bell tolls just before the dawn, signalling the end of their nocturnal merriment. Stokowski arranged Night on Bald Mountain’s final bars to fade away as a vocalizing chorus precedes the beginning of the Ave Maria. Where Night on Bald Mountain incorporated numerous styles in a disorderly frolic, the Ave Maria is rigid and structured by design (the camera only moves horizontally from left to right or zooms forward). In twos, robed monks walk through a forest bearing torches – their figures obscured behind trees, their reflections gleaming in the water. As the camera zooms forward for the first time, darkness envelops the screen. Using English lyrics by Rachel Field that do not adapt Schubert’s German lyrics, soprano Julietta Novis sings the final stanza of the Ave Maria (Field’s first two stanzas were unused) as the multiplane camera gradually glides through a still bower. The Ave Maria features some of the smallest individually-animated pieces (the monks) ever brought to screen. And with the multiplane camera (when the monks are onscreen, the multiplane camera – which was created to provide depth to animated backgrounds – is utilized, for the first time in its existence, to evoke flatness), it also contains what may be the longest uncut sequence in animation history.

The Ave Maria’s beauty sharpens the contrast between itself and Night on Bald Mountain – the sacred and the profane. Their spiritual and musical pairing is cinematic transcendence. Yet, the Ave Maria was almost cut entirely from the film at the last moment, as it was spliced into the final cut four hours before Fantasia’s world premiere – all thanks to an earthquake that struck Southern California a few days earlier. How fortunate for those worked on the segment, the preceding Night on Bald Mountain, for Fantasia, and cinema that the Ave Maria was included in the end.

Some of the pieces considered by Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor that did not make the final cut appeared in Fantasia 2000 – most notably Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite (1919 version), which Walt initially preferred over The Rite of Spring until convinced by Taylor otherwise. In contrast to his company’s contemporary attitude, Walt Disney himself was disapproving towards proposing sequels, with Fantasia proving the only exception. Walt imagined sequels to Fantasia to be released every several years, with newer Fantasia sequences starring alongside one or two reruns. Other pieces Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor (who wrote additional introductions in anticipation of future Fantasia films; I am looking into whether these introductions still exist) contemplated remain unadapted as Fantasia segments. The notes and preliminary sketches of some of these proposed segments – including a fascinating consideration to adapt selections from Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (the Ring cycle) to J.R.R. Tolkien’s then-newly-published children’s book The Hobbit – most likely reside in the Walt Disney Archives for reference if and when the company’s executives approve a third Fantasia movie.

Walt Disney’s dream of Fantasia sequels was quickly dashed. His proposal to add Fantasound – the studio’s prototypical variant of a stereo sound system – proved extravagantly expensive for all but a dozen movie theaters in the United States. Released as a roadshow (a limited national tour of major American cities followed by a general release), the inflated ticket prices due to the roadshow’s Fantasound system harmed Fantasia’s box office. Though a vast majority of film critics and some within classical music circles hailed Fantasia, the vocal and vehement division was inescapable. Some cultural and film critics, citing solely that Walt Disney had bothered to touch classical music, castigated Walt and Fantasia as pretentious (classical music’s negative reputation of being dated, inaccessible, and snobby was not nearly as widespread in the 1940s as it is today; musical appreciation and education has receded in the U.S. in the last several decades). Intransigent classical music purists – usually noting Stokowski’s frequent cutting of the music – lambasted Fantasia as debasing the compositions (I dislike Stokowski’s cutting, certain stretches of the Bach and Stravinsky recordings, and much of the Pastoral’s story, but this is a reactionary overreach). The negativity from both spheres stole the headlines, eroding interest from North American audiences. With the European box office non-existent, Pinocchio and Fantasia stood no chance of turning a profit on their initial releases. Their combined commercial failure sent the studio in a financial tailspin – a crisis that a comparatively low-budget Dumbo single-handedly averted.

Rankled by the criticism directed towards Fantasia, Walt Disney’s anger turned inwards, fostering a personal and corporate disdain of intellectuals that marked the rest of his career. One sees it in his irritation towards critics decrying the handling of race in Song of the South (1946); it is also there in his dismissive treatment of P.L. Travers over an adaptation of her novel Mary Poppins.

Mounting tension among Disney’s animators over credits, favoritism towards veteran animators over the studio’s pay scale and workplace amenities, the announcement of future layoffs due to the studio’s financial crisis, the unionization of animators at all of Disney’s rival studios, and Walt’s political naïveté in heeding the words of Gunther Lessing (the studio’s anti-communist legal counsel) threatened to explode into public view. On May 28, 1941, unionized Disney animators began what is known – and downplayed to this day by the Walt Disney Company – as the Disney animators’ strike. The strike, which lasted for two months, shredded friendships between strikers and non-strikers. Walt Disney, who surveyed the striking animators and filed away names in his deep memory, is said to have repeatedly referred to the strikers as, “commie sons of bitches”. More than once at the studio’s entrance, Walt slammed on his car’s accelerator towards the strikers and hit the brakes before making contact.

Under pressure from lenders, Walt recognized the union in late July but nevertheless fired numerous striking (and non-striking) animators in the months afterwards. Many of those terminated by Disney joined cross-Hollywood rivals or founded the upstart United Productions of America (UPA; Mr. Magoo series, 1962’s Gay Purr-ee). An embittered Walt would never again feel the sense of family among his studio’s staff as he did in the 1920s and ‘30s at the Hyperion studio, despite his public persona and statements to the contrary.

A wonder of filmmaking, Fantasia arrived in movie theaters as Disney’s Golden Age began to fracture. If not for war or Walt Disney’s obstinance, this era might have lasted longer. In the decades since, the contemptuous responses to Fantasia from classical music elites have cooled – for classical music lovers with not nearly as much institutional power, Fantasia has indeed become a beloved gateway into the genre. Its irrepressible beauty, invention, and bravery as a visual concert cannot be overstated.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating.

This is the sixteenth Movie Odyssey Retrospective. Movie Odyssey Retrospectives are reviews on films I had seen in their entirety before this blog’s creation or films I failed to give a full-length write-up to following the blog’s creation. Previous Retrospectives include The Wizard of Oz (1939), Dumbo (1941), and Godzilla (1954).

For more of my reviews, check out the “My Movie Odyssey” tag on my blog.

* The completed Clair de Lune segment was re-edited and integrated into Make Mine Music (1946).

‡ Mussorgsky’s original score for Night on Bald Mountain – which was not performed again during his lifetime following the piece’s premiere – went missing after his death in 1881. In 1886, fellow composer and colleague Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, controversially began editing Mussorgsky’s partially missing scores using his “musical conscience” (including the opera Boris Godunov). Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to preserve and retain his colleague’s music among aficionados of Russian classical music. The version of Night on Bald Mountain heard in Fantasia is Rimsky-Korsakov’s arrangement of the piece. Mussorgsky’s original score to Night on Bald Mountain was found in 1968, but the Rimsky-Korsakov arrangement is more frequently performed today.

#Fantasia#Walt Disney#Leopold Stokowski#Deems Taylor#Mickey Mouse#Philadelphia Orchestra#Joe Grant#Dick Huemer#James Wong Howe#Fred Moore#T. Hee#Norm Ferguson#Wilfred Jackson#Bill Tytla#My Movie Odyssey

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the mid 1930s, the Disney Studios grew quickly to staff up for Snow White. Roy Disney ran several "raids" on East coast studios, hiring away their top talent to come join the Disney brothers in the West. This caused a schism at the studio between "Walt's Boys" (the ones from the West coast) and the "New Yorkers" (artists hired away from New York studios). The New Yorkers dressed differently, with three piece suits and hats, while Walt's Boys were more casual. They sat at different tables at lunch. The two factions interacted with each other on a business level, but there was an unspoken feeling of "us and them" at the studio. Eventually, when Snow White was finished, Walt's Boys were richly rewarded with bonuses, while the New Yorkers got token bonuses. They say that history is written by the victor, and that is definitely true of Disney history. After the strike, many of these East coast artists left Disney and never returned. When the time came to write "The Illusion of Life", the focus was on Walt's Boys and the New York animators got short shrift again.

One of these artists was Berny Wolf. He started at Fleischer animating Cab Calloway as a walrus in Minnie the Moocher, trained under Grim Natwick at the Iwerks Studio, and animated many classic scenes at Disney, including Mickey on the tightrope in "Mickey's Circus" and Jiminy Cricket riding the seahorse in "Pinocchio". I interviewed Bern late in his life and he was still the consummate East coast animator with a three piece pinstripe suit, a gold watch chain and a carnation in his lapel. You should know about him. CLICK to see some of his incredible work... https://animationresources.org/biography-berny-wolf-1911-2006-2/

Corporate animation history books focus on studios and characters, but the history of animation isn't the history of Bugs Bunny or Disney Studios- it's the story of the artists who worked for the studios to create those memorable characters. Animation Resources is an organization by artists and for artists. It's one of the few places where you can get the stories of the great people who built the animation business from their own perspective. And it's one of the few organizations dedicated to help you become a great artist too; so you carry the art form further. WHY AREN'T YOU A MEMBER OF ANIMATION RESOURCES YET? Join today. https://animationresources.org/membership/levels/

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1965, Japan’s premier animation studio, Toei Doga, was busy producing their eighth feature film, Gulliver’s Space Travels. It was their first movie created with an international audience in mind, drawing inspiration of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver's Travels books.

Toei President Hiroshi Okawa founded the animation studio in 1956 with the dream of becoming “the Walt Disney of Japan,” sharing his nation’s rich cultural heritage with the rest of the world, and showcasing the innovative talents of his animators. These animators had studied the pioneers of Western animation, from Disney to Fleischer and all points in between, but they were slowly developing new ideas for animation theory, encouraging all staff members, regardless of status, to suggest story ideas.

One young man jumped at the opportunity, an in-between animator who was hired two years prior and trained by the studio’s teachers. Despite his entry-level position, the young animator was bursting at the seams with energy and ideas, and he had a bold idea: he wanted to change the ending to the movie.

Gulliver’s Space Travels is an outer-space adventure about a young boy named Ted who joins up with a grandfatherly Gulliver for an adventure to the stars. They discover an alien world where a race of robotic puppets are oppressed by a sinister race of evil robots from an adjacent world. Armed with a water pistol and an assortment of cartoon friends, Ted and Gulliver rescue the puppet princess, defeat the invading machines and bring peace to the realm.

This rookie animator had a novel idea: Instead of merely rescuing the world of puppets, what would happen if the princess, and all her people, were not puppets at all, but humans trapped inside by their robot overlords? When the princess is rescued, her shell could be cracked open with water, revealing a young human girl inside.

The young man’s name, of course, was Hayao Miyazaki. The studio, and his peers, quickly took notice of his talents, and he soon rose to key animation, first with television, later on the classic Toei features Puss in Boots, Animal Treasure Island (a Miyazaki film in all but name) and Ali Baba & the 40 Thieves.

http://ghiblicon.blogspot.com/2018/04/the-continuing-adventures-of-bungalow.html

#hayao miyazaki#i always come back to this blog bc it's a valuable resource but i don't like the author very much tbh lol

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Fleischer

Max Fleischer was an American animator, inventor, film director and producer, and studio founder and owner. More famously known for his invention/creation of Betty and Superman. Max immigrated to the US and served as the head of Fiescher Studios where he created Superman and Betty.

Fleischer began his career at The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Beginning as an errand boy, he advanced to photographer, photoengraver, and eventually, staff cartoonist. He started out by drawing single panel editorial cartoons, but then graduated to the full strips "Little Algie" and "S.K. Sposher, the Camera Fiend".

0 notes

Text

Animation has it’s share of many, many uncredited artists/animators. Especially those that weren’t key men (story, layout, background, animation, etc). One of them, Michael “Mike” Balukas, was deaf and while working at Disney. He had his own method to combat the problem of not hearing the word, “earthquake!” Which was stacking pencil stubs on the top of his desk, in which the later Disney animators would “prank” him after that. He is seen in a 1928 Harrison-Gould staff photo (in the far left) and in this 1930-1931 Fleischer Studios photo, an inker for H-G and I presume that or an inbetweener at Flesicher and Disney.

He was born in 1906 in Pennsylvania and died somewhere else in 1992 and his mother came from Lithuania and was more than likely raised Catholic.

The 1940 census lists him as living with his mother, Anna. And his 5 brothers and 2 sisters in Brooklyn, New York so it’s safe to say that he left the industry sometime after the 1930’s.

Sources: https://www.ancestry.com/1940-census/usa/New-York/Michael-Balukas_99fk0 http://animationguildblog.blogspot.com/2007/05/harrison-and-gould-krazy-kat-crew-circa.html https://www.athensnews.com/opinion/columns/wise_up/wise-up-11-30-09/article_f86fc725-db2c-5b52-bca0-bb8fdc72616f.html

#toot’s talking corner#deaf people#deafculture#deafness#animators#artists#inkers#ink & paint#cel animation#fleischer studios#harrison-gould#disney#charles mintz#max fleischer#walt disney#lithuania#golden age of animation#silent age of animation#animation#fleischer studio staff#disney staff#1920’s#1930’s#uncredited artist#new york

1 note

·

View note

Text

Happy Halloween: a 20′s & 30′s Cartoon Playlist to Spook & Delight

*If you don’t want to read any intro blurb just scroll further down (click "Keep Reading” if you’re seeing this on your dashboard) to watch the shorts.

I’ve been seeing a lot of interest in 20′s and 30′s animation recently (I’m sure a huge thank you is in order to Cuphead and studio MDHR for that!) and I’ve been really enjoying it. Up until Disney set a certain standard for realism in cartoons, they were particularly... bizarre. Cartoons have always been wacky, but there’s a certain delight in watching a 20′s or 30′s cartoon and thinking “...what the hell?” to yourself, in the best possible way. With Halloween giving creators themes of hell, demons, and all sorts of spooky things to play with, the bizarre factor of these cartoons is even higher and so I thought I’d compile a playlist to watch on Halloween itself. What I initially started as a playlist for myself has ended up being something I’d like to share with everyone - I ended up watching a lot more cartoons than are included here, but I thought I’d cherry pick them for the public playlist.

I’m by no means an expert and I feel most of these cartoons are fairly well known, however I certainly hope you’ll find them as delightful as I do. And while I can’t guarantee any of them will outright spook you, I’m sure you will feel at least a bit... bewildered, in a good way. Happy Halloween and enjoy!

To start the playlist click here, or read on for individual videos with commentary!

Heads up! This post is in two parts due to Tumblr’s 5 video per post limit. You’ll find a link to part 2 at the bottom.

The Haunted House (1929)

Talk about skeletons in the closet! This Mickey Mouse cartoon about Mickey finding himself in a haunted house is a great example of recycled animation - it borrows a lot of its animation from the earlier Skeleton Dance. Besides being quite a fun short, The Haunted House also helped pave the way for further horror-themed Disney cartoons.

WARNING: There’s some intense black and white flashing in this cartoon - briefly, but very vividly. If you have photosensitive epilepsy you’ll want to be careful with this one or skip it altogether.

youtube

Betty Boop’s Hallowe’en Party (1933)

This cartoon is definitely not as spooky as much as it is fun - and with a Halloween theme specifically!

youtube

Bimbo’s Initiation (1931)

Bimbo’s Initiation is not necessarily Halloween themed but it has been described as the “darkest” of Fleischer cartoons - just give it a watch and you’ll now why.

youtube

Spooks (1931)

Oh man, I love this one! A Flip the Frog cartoon slightly similar to The Haunted House earlier on this list. Flip finds himself in a house inhabited by skeletons and has a generally good time (though not for long!)

youtube

Swing You Sinners (1930)

This is one of those cartoons where things just keep getting darker and weirder! Definitely a staple for Halloween and any time you want to watch something utterly bizarre. Not only the content is bizarre - there’s a caricature of a Jewish man halfway through that I found absolutely bewildering. Apparently, however, the atmosphere in the studio made it seem acceptable even to the Jewish staff at the studio (from Wikipedia, which cites animator Shamus Culhane’s memoir. As I have not read it myself I cannot confirm this).

Cuphead fans might recognise the inspiration the caricature provided for Cagney Carnation! According to the Youtube comments the creators of the game have cited this cartoon as a huge source of inspiration.

youtube

Click here for part 2!

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Welcome to the tenth of the Superman cartoons, released in theaters by Paramount Pictures on September 18, 1942.

While generally known as the “Fleischer Studios’ Superman cartoons,” in fact Fleischer Studios no longer existed. Due to numerous reasons, Paramount took over Fleischer Studios, forced Max and Dave Fleischer out, and renamed the animation company Famous Studios.

The bulk of the staff at the animation studio remained with the company (at least until Paramount started downsizing the company when they forced it to move from Miami to New York), which is why the last eight cartoons in the Superman series look identical to the first nine. Additionally, Max Fleischer’s son-in-law and head animator, Seymour Kneitel, was promoted to director and supervising producer, so he did his best to keep up the good work his father-in-law started.

Besides changing the name of the animation studio, Paramount dictated the types of stories it wanted to see in the Superman series. The studio had tried to do so at the beginning but the Fleischer brothers refused to comply. The stories they crafted involved wild science fiction themes and larger-than-life mad scientists and criminals. Paramount, instead, had Superman dealing with much more mundane matters like gangsters and saboteurs (as in this episode).

This is going to be a truncated presentation of the cartoon, as opposed to previous posts. In 1942 the United States was at war with Japan, and the attack on Pearl Harbor was still a fresh wound. People of Japanese descent all over America were being herded up and placed in concentration camps (dubbed “internment camps”). The Japanese were the enemy at the time and, as most nations do, it was common to dehumanize/demonize the enemy.

Unfortunately, this cartoon is no exception. I won’t even post the title because it contains a slur, which is repeated a few times throughout the story. I will also not be presenting most of the scenes with the bad guys (who are Japanese saboteurs) because they are drawn as grotesque caricatures that may have been acceptable back in the day (although they shouldn’t have), but are certainly unacceptable now.

Anyhow, let me get off my high horse, dispense with the history lesson, and get on with the show!

A lone figure peruses the morning paper with great interest.

A none-too-subtle sign to the audience that this is a bad guy.

(And you’d think he’d hide that secret button a little better. All it needs is for the janitor to bump it while cleaning the office and the jig is up!)

Just in case you’re not how this guy feels about America’s newest weapon.

They’re busy at the factory loading the giant bomber for its test flight.

But nefarious figures have infiltrated the factory!

Wow! They weren’t kidding when they named it the “giant bomber!” That thing’s almost as big as the starship Enterprise!

And, of course, the press arrive for the big roll-out.

“Lois Lane of the Daily Planet.”

“Clark Kent. Planet.”

(Notice that Clark didn’t let Lois steal his press pass this time.)

The giant bomber is so large that people get altitude sickness riding the escalator to enter it.

Clark: “How would you like to be making the test flight in this, Lois?”

Lois: “Hmm. Maybe I will.”

Clark: “Ha! Fine chance.”

Army officer: “Everyone off, please. Everyone off.”

Clark: “Come on, Lois. That’s us.”

Oh, Lois! Haven’t you learned that nothing good ever happens when you do stuff like this?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephanie Grisham: Trump’s Press Secretary Who Doesn’t Meet the Press