#fairytales in shakespeare

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

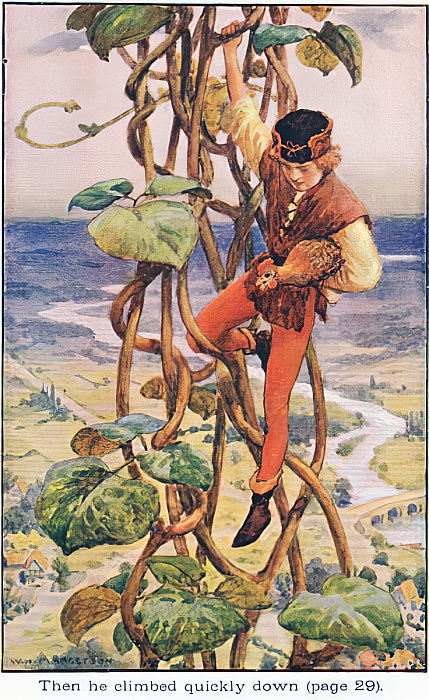

Let's go up the giant beanstalk (2)

I said before that “Jack and the Beanstalk” and “Jack the Giant-Killer” are two different tales that should not be confused with each other – but it does not mean they are not related… Indeed the link between those sibling-stories goes beyond simply sharing a giant-opposing Jack. There is a running tradition in Jack adaptations and pantomimes to name the giant “Blunderbore” – which is actually one of the giants of “Jack the Giant-Killer” – and while this seems to have no root in any of the published texts above… the first printed version of the tale, the “Jack Spriggins” parody, did name the giant using a character from “Jack the Giant-Killer”. Though it was not “Blunderbore” – the Jack Spriggins tale rather names the giant “Gogmagog”.

If things were not confusing enough, the giant of “Jack and the beanstalk” is known for his iconic line, “Fee-fi-fo-fum, I smell the bones of an Englishman.” (It is the Jacobs’ version of the rhyme, which continues, with other rhymes saying how the giant will grind Jack’s bones to make his bread). Well, this line is ALSO present within “Jack the Giant-Killer”, but rather sung by a giant named Thunderdell. “Fee, fau, fum (or alternatively “Fe, fi, fo, fum”) / I smell the blood of an English man” – again, continued by rhymes evoking a bread made out of human bones. This line, “Fee, fi, fo, fum”, has in itself a fascinating history because, as with many British fairytales, we can find an old manifestation of it… within Shakespeare’s plays. More precisely, in Shakespeare’s famous tragedy “King Lear”, we find the lines “Fie, foh and fum / I smell the blood of a British man”. This line comes from the very end of the fourth scene of Act III, where the character of Edgar pretends to be a madman by the name of Tom, and thus speaks in mysterious references and nonsensical riddles, and when he quotes this line, he does not do it in reference to any Jack tale… But rather by mixing it to the famous British story of “Childe Rowland”. The actual quote by Edgar/Tom is “Childe Roland to the dark tower came. / His word was still ‘Fie, foh and fum, / I smell the blood of a British man’.” It is very likely to be a comical mix-up of various folktales together, since the line is not traditionally linked to the Childe Roland tale – but it is extremely interesting, because it explains the first word of the seemingly nonsensical rhyme. Indeed, the “Fe/Fee” of later Jack tales is here a “Fie”, aka the archaic onomatopoeia of disapproval, and one that Shakespeare loved to use. As such, it is possible that the original first word of the rhyme was a “fie”…

Mind you, there is an even older record of the line: it first appears in 1596, under the pen of Thomas Nashe, in his pamphlet “Haue with you to Saffron-Walden” (it was part of a series of attacks he wrote against the writer Gabriel Harvey). It is where the line first appears, under the shape of “Fy, fa and fum, / I smell the blood of an Englishman”, but within the same pamphlet, the rhyme is described as being very old, so old in fact its origin has been lost to time…

There is a lot to say about “Jack and the Beanstalk”, but for now I will highlight a final element that participates in weaving this tale in the tapestry of British folklore: the goose. In the version we all know and share, Jack steals three things from the giant. Money, a magical harp that plays on its own, and a goose that lays eggs made of gold. The goose with golden eggs actually dates back to one of the oldest collections of fables we have: Aesop’s fables written in Ancient Greece, by the seventh or sixth century BCE. One of those fables is titled “The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs”. In France, it was re-popularized by Jean de La Fontaine’s own collection of fables, which had a modernized version of the story, “La poule aux oeufs d’or”, “The hen with gold-eggs”. But it is from Aesop’s fable that came the European symbol of the “goose with golden eggs”, and various sayings and proverbs such as “Do not kill the goose that lays the golden egg”, which itself was then recut and reshaped into various other proverbs (such as “killing the goose” for a self-destructive action). If you do not know, the fable always end up the same way, though the reasons behind differ – the owner(s) of the goose that lays golden eggs end up killing it due to their greed and desire to have more gold, thus destroying the very source of money they relied upon.

But where the “golden-egged goose” link becomes interesting is within the domain of nursery rhymes. I made a LONG time ago a series of posts about “Mother Goose” (they were in fact my very first posts on this blog). Long story short, Mother Goose did not exist in England until the second half of the 18th century. Indeed, she became known to the English world thanks to the translations in English of Charles Perrault’s fairy tale collections “Les contes de ma Mère l’Oye”, “The tales of my Mother Goose”, in the early 18th century. But from the mid 18th century onwards, publishers of nursery rhymes and other children-aimed books started using “Mother Goose” as a sort of mascot, recurring figure or title-cliché, in reference to Charles Perrault’s fairytale book. As such, soon Mother Goose started becoming a British “emblem” or “symbol” of nursery rhymes as a whole, seen as “Mother Goose’s rhymes”. England invented an entire character based on this single name – and by the early 19th century, she even got her own nursery rhyme/pantomimes (the two were always closely linked and I do not have enough expertise to go into the details). The “rhyme” of Mother Goose was not notably known under the title… “Mother Goose, or the Golden Egg”/ “Old Mother Goose and the Golden Egg”. Because to the character of Mother Goose, “mascot” of fairy tales and nursery rhymes, was added the fable of the Goose that Laid Golden Eggs… And in the nursery rhyme and the pantomimes, who is the third character that makes the link between the mother and the egg-layer? Mother Goose’s son… Jack. Yes, another Jack linked to a mother figure and who ends up with a goose laying golden-eggs – though no giant appears in this version, as this Jack is rather inspired by the various Jacks of nursery rhymes (or so I heard, again, I am no expert on the topic).

As you can see, from one simple story we enter a maze of references, links and cultural inter-weaving tying together a lot of various domains…

#jack and the beanstalk#jack tales#jack the giant-killer#shakespeare#fairytales in shakespeare#british fairytales#english fairy tales#the goose that laid golden eggs#the goose with golden eggs#fables#giants#childe roland#childe rowland#mother goose#nursery rhymes

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"black girls deserve fairytale love" - soe noire

planet frizz magazine (2024)

muse: francesca amewudah-rivers

she's my juliet fr, she will do AMAZING

#francesca amewudah rivers#romeo and juliet#protect black women#fairytale#shakespeare#black girl magic#black is beautiful#black tumblr#melanin#princess#musicals#tom holland

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tell Your Dad You Love Him

A retelling of "Meat Loves Salt"/"Cap O'Rushes" for the @inklings-challenge Four Loves event

An old king had three daughters. When his health began to fail, he summoned them, and they came.

Gordonia and Rowan were already waiting in the hallway when Coriander arrived. They were leaned up against the wall opposite the king’s office with an air of affected casualness. “I wonder what the old war horse wants today?” Rowan was saying. “More about next year’s political appointments, I shouldn’t wonder.”

“The older he gets, the more he micromanages,” Gordonia groused fondly. “A thousand dollars says this meeting could’ve been an email.”

They filed in single-file like they’d so often done as children: Gordonia first, then Rowan, and Coriander last of all. The king had placed three chairs in front of his desk all in a row. His daughters murmured their greetings, and one by one they sat down.

“I have divided everything I have in three,” the king said. “I am old now, and it’s time. Today, I will pass my kingdom on to you, my daughters.”

A short gasp came from Gordonia. None of them could have imagined that their father would give up running his kingdom while he still lived.

The king went on. “I know you will deal wisely with that which I leave in your care. But before we begin, I have one request.”

“Yes father?” said Rowan.

“Tell me how much you love me.”

An awkward silence fell. Although there was no shortage of love between the king and his daughters, theirs was not a family which spoke of such things. They were rich and blue-blooded: a soldier and the daughters of a soldier, a king and his three court-reared princesses. The royal family had always shown their affection through double meanings and hot cups of coffee.

Gordonia recovered herself first. She leaned forward over the desk and clasped her father’s hands in her own. “Father,” she said, “I love you more than I can say.” A pause. “I don’t think there’s ever been a family so happy in love as we have been. You’re a good dad.”

The old king smiled and patted her hand. “Thank you, Gordonia. We have been very happy, haven’t we? Here is your inheritance. Cherish it, as I cherish you.”

Rowan spoke next; the words came tumbling out. “Father! There’s not a thing in my life which you didn’t give me, and all the joy in the world beside. Come now, Gordonia, there’s no need to understate the matter. I love you more than—why, more than life itself!”

The king laughed, and rose to embrace his second daughter. “How you delight me, Rowan. All of this will be yours.”

Only Coriander remained. As her sisters had spoken, she’d wrung her hands in her lap, unsure of what to say. Did her father really mean for flattery to be the price of her inheritance? That just wasn’t like him. For all that he was a politician, he’d been a soldier first. He liked it when people told the truth.

When the king’s eyes came to rest on her, Coriander raised her own to meet them. “Do you really want to hear what you already know?”

“I do.”

She searched for a metaphor that could carry the weight of her love without unnecessary adornment. At last she found one, and nodded, satisfied. “Dad, you’re like—like salt in my food.”

“Like salt?”

“Well—yes.”

The king’s broad shoulders seemed to droop. For a moment, Coriander almost took back her words. Her father was the strongest man in the world, even now, at eighty. She’d watched him argue with foreign rulers and wage wars all her life. Nothing could hurt him. Could he really be upset?

But no. Coriander held her father’s gaze. She had spoken true. What harm could be in that?

“I don’t know why you’re even here, Cor,” her father said.

Now, Coriander shifted slightly in her seat, unnerved. “What? Father—”

“It would be best if—you should go,” said the old king.

“Father, you can’t really mean–”

“Leave us, Coriander.”

So she left the king’s court that very hour.

.

It had been a long time since she’d gone anywhere without a chauffeur to drive her, but Coriander’s thoughts were flying apart too fast for her to be afraid. She didn’t know where she would go, but she would make do, and maybe someday her father would puzzle out her metaphor and call her home to him. Coriander had to hope for that, at least. The loss of her inheritance didn’t feel real yet, but her father—how could he not know that she loved him? She’d said it every day.

She’d played in the hall outside that same office as a child. She’d told him her secrets and her fears and sent him pictures on random Tuesdays when they were in different cities just because. She had watched him triumph in conference rooms and on the battlefield and she’d wanted so badly to be like him.

If her father doubted her love, then maybe he’d never noticed any of it. Maybe the love had been an unnoticed phantasm, a shadow, a song sung to a deaf man. Maybe all that love had been nothing at all.

A storm was on the horizon, and it reached her just as she made it onto the highway. Lightning flashed and thunder rolled. Rain poured down and flooded the road. Before long, Coriander was hydroplaning. Frantically, she tried to remember what you were supposed to do when that happened. Pump the brakes? She tried. No use. Wasn’t there something different you did if the car had antilock brakes? Or was that for snow? What else, what else–

With a sickening crunch, her car hit the guardrail. No matter. Coriander’s thoughts were all frenzied and distant. She climbed out of the car and just started walking.

Coriander wandered beneath an angry sky on the great white plains of her father’s kingdom. The rain beat down hard, and within seconds she was soaked to the skin. The storm buffeted her long hair around her head. It tangled together into long, matted cords that hung limp down her back. Mud soiled her fine dress and splattered onto her face and hands. There was water in her lungs and it hurt to breathe. Oh, let me die here, Coriander thought. There’s nothing left for me, nothing at all. She kept walking.

.

When she opened her eyes, Coriander found herself in a dank gray loft. She was lying on a strange feather mattress.

She remained there a while, looking up at the rafters and wondering where she could be. She thought and felt, as it seemed, through a heavy and impenetrable mist; she was aware only of hunger and weakness and a dreadful chill (though she was all wrapped in blankets). She knew that a long time must have passed since she was fully aware, though she had a confused memory of wandering beside the highway in a thunderstorm, slowly going mad because—because— oh, there’d been something terrible in her dreams. Her father, shoulders drooping at his desk, and her sisters happily come into their inheritance, and she cast into exile—

She shuddered and sat up dizzily. “Oh, mercy,” she murmured. She hadn’t been dreaming.

She stumbled out of the loft down a narrow flight of stairs and came into a strange little room with a single window and a few shabby chairs. Still clinging to the rail, she heard a ruckus from nearby and then footsteps. A plump woman came running to her from the kitchen, wiping her hands on her apron and softly clucking at the state of her guest’s matted, tangled hair.

“Dear, dear,” said the woman. “Here’s my hand, if you’re still unsteady. That’s good, good. Don’t be afraid, child. I’m Katherine, and my husband is Folke. He found you collapsed by the goose-pond night before last. I’m she who dressed you—your fine gown was ruined, I’m afraid. Would you like some breakfast? There’s coffee on the counter, and we’ll have porridge in a minute if you’re patient.”

“Thank you,” Coriander rasped.

“Will you tell me your name, my dear?”

“I have no name. There’s nothing to tell.”

Katherine clicked her tongue. “That’s alright, no need to worry. Folke and I’ve been calling you Rush on account of your poor hair. I don’t know if you’ve seen yourself, but it looks a lot like river rushes. No, don’t get up. Here’s your breakfast, dear.”

There was indeed porridge, as Katherine had promised, served with cream and berries from the garden. Coriander ate hungrily and tasted very little. Then, when she was finished, the goodwife ushered her over to a sofa by the window and put a pillow beneath her head. Coriander thanked her, and promptly fell asleep.

.

She woke again around noon, with the pounding in her head much subsided. She woke feeling herself again, to visions of her father inches away and the sound of his voice cracking across her name.

Katherine was outside in the garden; Coriander could see her through the clouded window above her. She rose and, upon finding herself still in a borrowed nightgown, wrapped herself in a blanket to venture outside.

“Feeling better?” Katherine was kneeling in a patch of lavender, but she half rose when she heard the cottage door open.

“Much. Thank you, ma’am.

“No thanks necessary. Folke and I are ministers, of a kind. We keep this cottage for lost and wandering souls. You’re free to remain here with us for as long as you need.”

“Oh,” was all Coriander could think to say.

“You’ve been through a tempest, haven’t you? Are you well enough to tell me where you came from?”

Coriander shifted uncomfortably. “I’m from nowhere,” she said. “I have nothing.”

“You don’t owe me your story, child. I should like to hear it, but it will keep till you’re ready. Now, why don’t you put on some proper clothes and come help me with this weeding.”

.

Coriander remained at the cottage with Katherine and her husband Folke for a week, then a fortnight. She slept in the loft and rose with the sun to help Folke herd the geese to the pond. After, Coriander would return and see what needed doing around the cottage. She liked helping Katherine in the garden.

The grass turned gold and the geese’s thick winter down began to come in. Coriander’s river-rush hair proved itself unsalvageable. She spent hours trying to untangle it, first with a hairbrush, then with a fine-tooth comb and a bottle of conditioner, and eventually even with honey and olive oil (a home remedy that Folke said his mother used to use). So, at last, Coriander surrendered to the inevitable and gave Katherine permission to cut it off. One night, by the yellow light of the bare bulb that hung over the kitchen table, Katherine draped a towel over Coriander’s shoulders and tufts of gold went falling to the floor all round her.

“I’m here because I failed at love,” she managed to tell the couple at last, when her sorrows began to feel more distant. “I loved my father, and he knew it not.”

Folke and Katherine still called her Rush. She didn’t correct them. Coriander was the name her parents gave her. It was the name her father had called her when she was six and racing down the stairs to meet him when he came home from Europe, and at ten when she showed him the new song she’d learned to play on the harp. She’d been Cor when she brought her first boyfriend home and Cori the first time she shadowed him at court. Coriander, Coriander, when she came home from college the first time and he’d hugged her with bruising strength. Her strong, powerful father.

As she seasoned a pot of soup for supper, she wondered if he understood yet what she’d meant when she called him salt in her food.

.

Coriander had been living with Katherine and Folke for two years, and it was a morning just like any other. She was in the kitchen brewing a pot of coffee when Folke tossed the newspaper on the table and started rummaging in the fridge for his orange juice. “Looks like the old king’s sick again,” he commented casually. Coriander froze.

She raced to the table and seized hold of the paper. There, above the fold, big black letters said, KING ADMITTED TO HOSPITAL FOR EMERGENCY TREATMENT. There was a picture of her father, looking older than she’d ever seen him. Her knees went wobbly and then suddenly the room was sideways.

Strong arms caught her and hauled her upright. “What’s wrong, Rush?”

“What if he dies,” she choked out. “What if he dies and I never got to tell him?”

She looked up into Folke’s puzzled face, and then the whole sorry story came tumbling out.

When she was through, Katherine (who had come downstairs sometime between salt and the storm) took hold of her hand and kissed it. “Bless you, dear,” she said. “I never would have guessed. Maybe it’s best that you’ve both had some time to think things over.”

Katherine shook her head. “But don’t you think…?”

“Yes?”

“Well, don’t you think he should have known that I loved him? I shouldn’t have needed to say it. He’s my father. He’s the king.”

Katherine replied briskly, as though the answer should have been obvious. “He’s only human, child, for all that he might wear a crown; he’s not omniscient. Why didn’t you tell your father what he wanted to hear?”

“I didn’t want to flatter him,” said Coriander. “That was all. I wanted to be right in what I said.”

The goodwife clucked softly. “Oh dear. Don’t you know that sometimes, it’s more important to be kind than to be right?”

.

In her leave-taking, Coriander tried to tell Katherine and Folke how grateful she was to them, but they wouldn’t let her. They bought her a bus ticket and sent her on her way towards King’s City with plenty of provisions. Two days later, Coriander stood on the back steps of one of the palace outbuildings with her little carpetbag clutched in her hands.

Stuffing down the fear of being recognized, Coriander squared her shoulders and hoped they looked as strong as her father’s. She rapped on the door, and presently a maid came and opened it. The maid glanced Coriander up and down, but after a moment it was clear that her disguise held. With all her long hair shorn off, she must have looked like any other girl come in off the street.

“I’m here about a job,” said Coriander. “My name’s Rush.”

.

The king's chambers were half-lit when Coriander brought him his supper, dressed in her servants’ apparel. He grunted when she knocked and gestured with a cane towards his bedside table. His hair was snow-white and he was sitting in bed with his work spread across a lap-desk. His motions were very slow.

Coriander wanted to cry, seeing her father like that. Yet somehow, she managed to school her face. Like he would, she kept telling herself. Stoically, she put down the supper tray, then stepped back out into the hallway.

It was several minutes more before the king was ready to eat. Coriander heard papers being shuffled, probably filed in those same manilla folders her father had always used. In the hall, Coriander felt the seconds lengthen. She steeled herself for the moment she knew was coming, when the king would call out in irritation, “Girl! What's the matter with my food? Why hasn’t it got any taste?”

When that moment came, all would be made right. Coriander would go into the room and taste his food. “Why,” she would say, with a look of complete innocence, “It seems the kitchen forgot to salt it!” She imagined how her father’s face would change when he finally understood. My daughter always loved me, he would say.

Soon, soon. It would happen soon. Any second now.

The moment never came. Instead, the floor creaked, followed by the rough sound of a cane striking the floor. The door opened, and then the king was there, his mighty shoulders shaking. “Coriander,” he whispered.

“Dad. You know me?”

“Of course.”

“Then you understand now?”

The king’s wrinkled brow knit. “Understand about the salt? Of course, I do. It wasn't such a clever riddle. There was surely no need to ruin my supper with a demonstration.”

Coriander gaped at him. She'd expected questions, explanations, maybe apologies for sending her away. She'd never imagined this.

She wanted very badly to seize her father and demand answers, but then she looked, really looked, at the way he was leaning on his cane. The king was barely upright; his white head was bent low. Her questions would hold until she'd helped her father back into his room.

“If you knew what I meant–by saying you were like salt in my food– then why did you tell me to go?” she asked once they were situated back in the royal quarters.

Idly, the king picked at his unseasoned food. “I shouldn’t have done that. Forgive me, Coriander. My anger and hurt got the better of me, and it has brought me much grief. I never expected you to stay away for so long.”

Coriander nodded slowly. Her father's words had always carried such fierce authority. She'd never thought to question if he really meant what he’d said to her.

“As for the salt,” continued the king, "Is it so wrong that an old man should want to hear his daughters say ‘I love you' before he dies?”

Coriander rolled the words around in her head, trying to make sense of them. Then, with a sudden mewling sound from her throat, she managed to say, “That's really all you wanted?”

“That's all. I am old, Cor, and we've spoken too little of love in our house.” He took another bite of his unsalted supper. His hand shook. “That was my failing, I suppose. Perhaps if I’d said it, you girls would have thought to say it back.”

“But father!” gasped Coriander, “That’s not right. We've always known we loved one another! We've shown it a thousand ways. Why, I've spent the last year cataloging them in my head, and I've still not even scratched the surface!”

The king sighed. “Perhaps you will understand when your time comes. I knew, and yet I didn't. What can you really call a thing you’ve never named? How do you know it exists? Perhaps all the love I thought I knew was only a figment.”

“But that’s what I’ve been afraid of all this time,” Coriander bit back. “How could you doubt? If it was real at all– how could you doubt?”

The king’s weathered face grew still. His eyes fell shut and he squeezed them. “Death is close to me, child. A small measure of reassurance is not so very much to ask.”

.

Coriander slept in her old rooms that night. None of it had changed. When she woke the next morning, for a moment she remembered nothing of the last two years.

She breakfasted in the garden with her father, who came down the steps in a chair-lift. “Coriander,” he murmured. “I half-thought I dreamed you last night.”

“I’m here, Dad,” she replied. “I’m not going anywhere.”

Slowly, the king reached out with one withered hand and caressed Coriander's cheek. Then, his fingers drifted up to what remained of her hair. He ruffled it, then gently tugged on a tuft the way he'd used to playfully tug her long braid when she was a girl.

“I love you,” he said.

“That was always an I love you, wasn’t it?” replied Coriander. “My hair.”

The king nodded. “Yes, I think it was.”

So Coriander reached out and gently tugged the white hairs of his beard. “You too,” she whispered.

.

“Why salt?” The king was sitting by the fire in his rooms wrapped in two blankets. Coriander was with him, enduring the sweltering heat of the room without complaint.

She frowned. “You like honesty. We have that in common. I was trying to be honest–accurate–to avoid false flattery.”

The king tugged at the outer blanket, saying nothing. His lips thinned and his eyes dropped to his lap. Coriander wished they wouldn’t. She wished they would hold to hers, steely and ready for combat as they always used to be.

“Would it really have been false?” the king said at last. “Was there no other honest way to say it? Only salt?”

Coriander wanted to deny it, to give speech to the depth and breadth of her love, but once again words failed her. “It was my fault,” she said. “I didn’t know how to heave my heart into my throat.” She still didn’t, for all she wanted to.

.

When the doctor left, the king was almost too tired to talk. His words came slowly, slurred at the edges and disconnected, like drops of water from a leaky faucet.

Still, Coriander could tell that he had something to say. She waited patiently as his lips and tongue struggled to form the words. “Love you… so… much… You… and… your sisters… Don’t… worry… if you… can’t…say…how…much. I… know.”

It was all effort. The king sat back when he was finished. Something was still spasming in his throat, and Coriander wanted to cry.

“I’m glad you know,” she said. “I’m glad. But I still want to tell you.”

Love was effort. If her father wanted words, she would give him words. True words. Kind words. She would try…

“I love you like salt in my food. You're desperately important to me, and you've always been there, and I don't know what I'll do without you. I don’t want to lose you. And I love you like the soil in a garden. Like rain in the spring. Like a hero. You have the strongest shoulders of anyone I know, and all I ever wanted was to be like you…”

A warm smile spread across the old king’s face. His eyes drifted shut.

#inklingschallenge#theme: storge#story: complete#inklings challenge#leah stories#OKAY. SO#i spend so much time thinking about king lear. i think i've said before that it's my favorite shakespeare play. it is not close#and one of the hills i will die on is that cordelia was not in the right when she refused to flatter her dad#like. obviously he's definitely not in the right either. the love test was a screwed up way to make sure his kids loved him#he shouldn't have tied their inheritances into it. he DEFINITELY shouldn't have kicked cordelia out when she refused to play#but like. Cordelia. there is no good reason not to tell your elderly dad how much you love him#and okay obviously lear is my starting point but the same applies to the meat loves salt princess#your dad wants you to tell him you love him. there is no good reason to turn it into a riddle. you had other options#and honestly it kinda bothers me when people read cordelia/the princess as though she's perfectly virtuous#she's very human and definitely beats out the cruel sisters but she's definitely not aspirational. she's not to be emulated#at the end of the day both the fairytale and the play are about failures in storge#at happens when it's there and you can't tell. when it's not and you think it is. when you think you know someone's heart and you just don'#hey! that's a thing that happens all the time between parents and children. especially loving past each other and speaking different langua#so the challenge i set myself with this story was: can i retell the fairytale in such a way that the princess is unambiguously in the wrong#and in service of that the king has to get softened so his errors don't overshadow hers#anyway. thank you for coming to my TED talk#i've been thinking about this story since the challenge was announced but i wrote the whole thing last night after the super bowl#got it in under the wire! yay!#also! the whole 'modern setting that conflicts with the fairytale language' is supposed to be in the style of modern shakespeare adaptation#no idea if it worked but i had a lot of fun with it#pontifications and creations

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

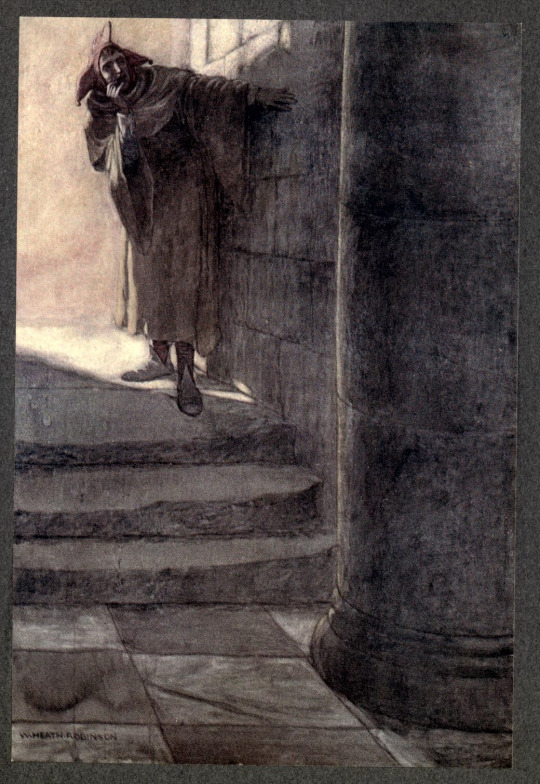

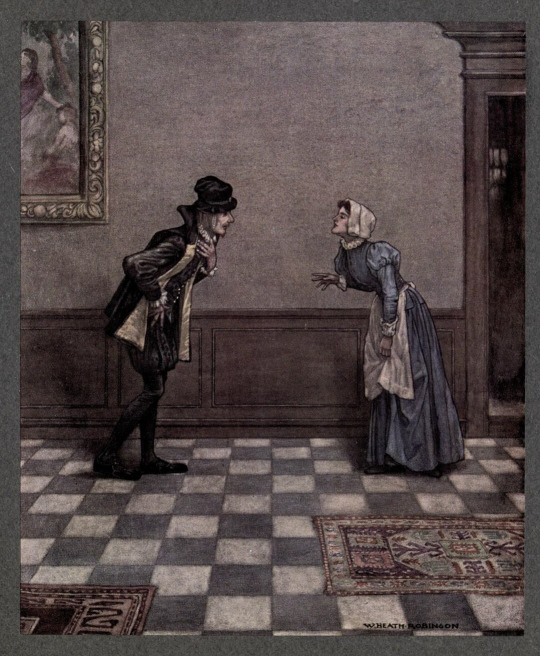

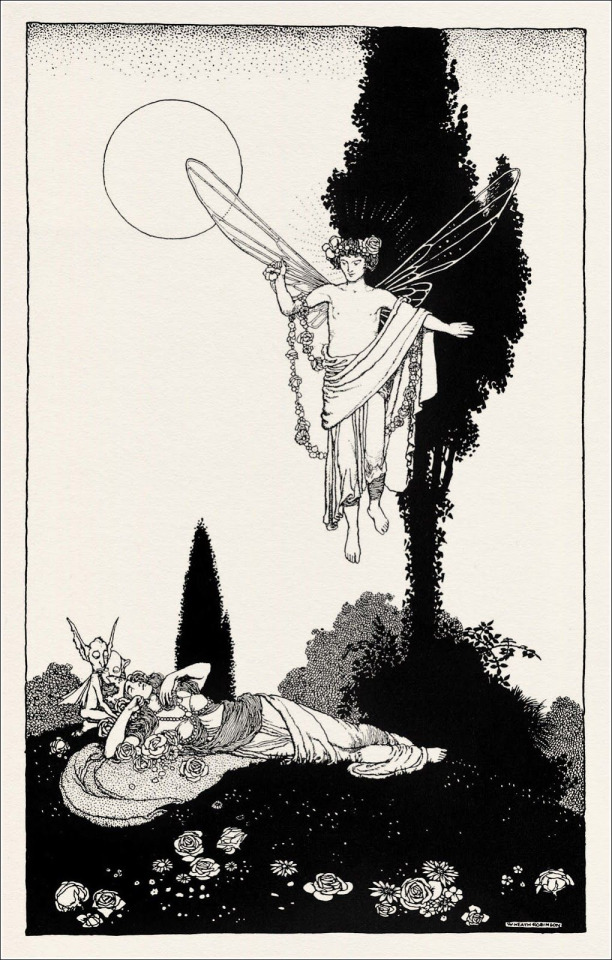

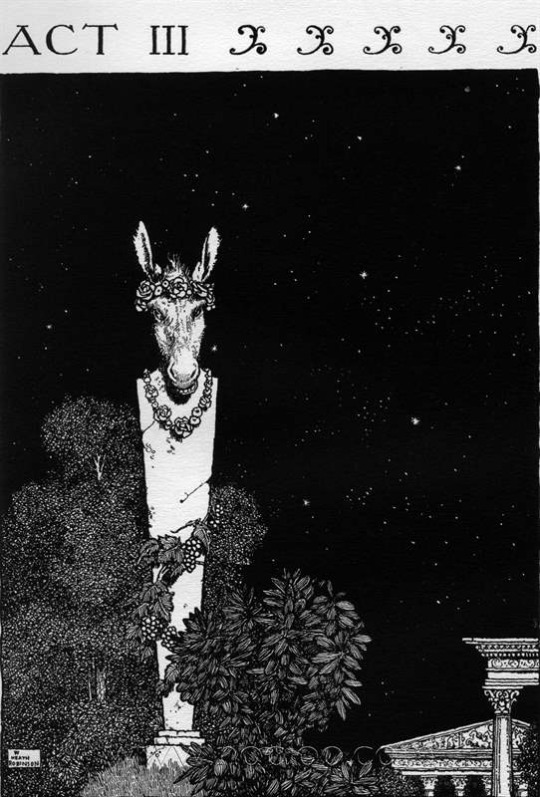

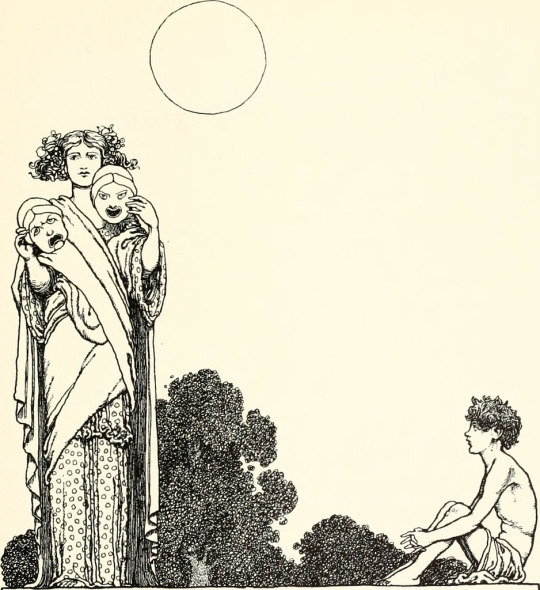

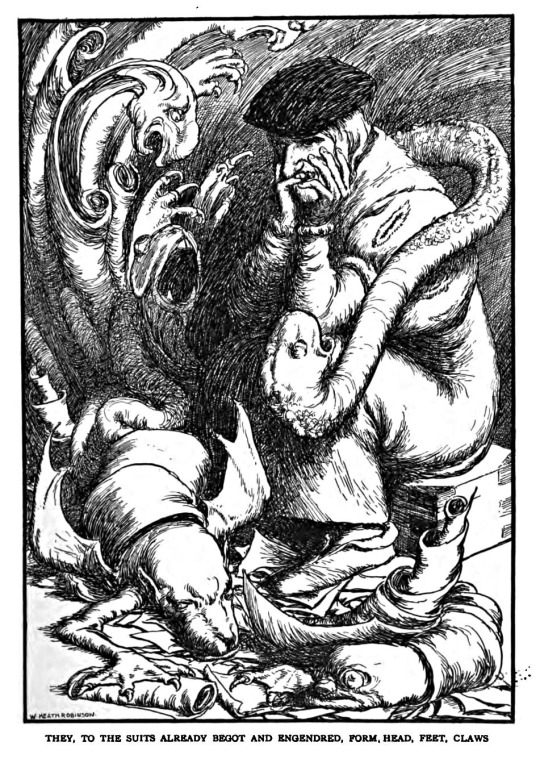

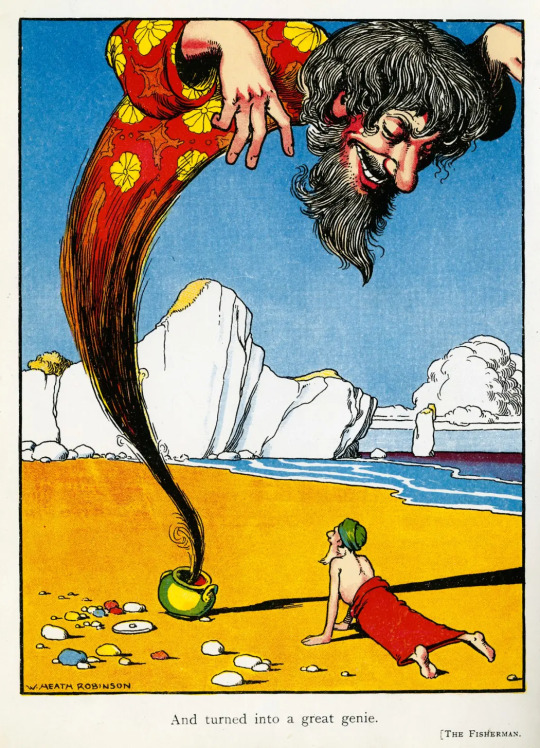

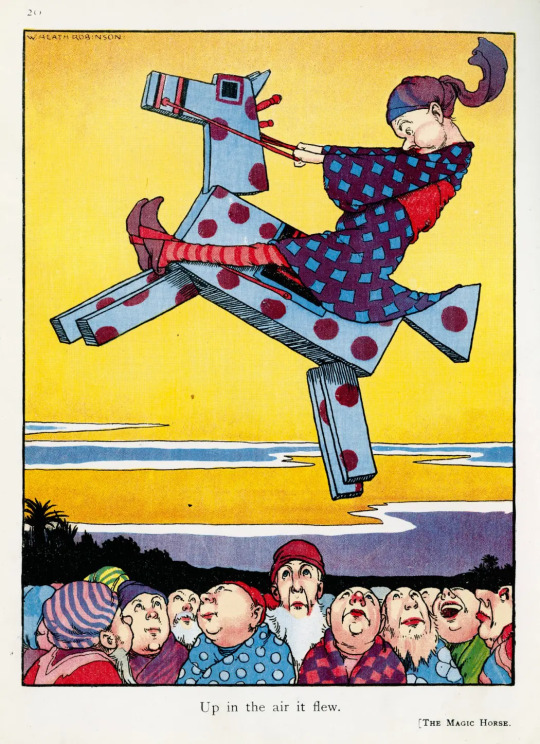

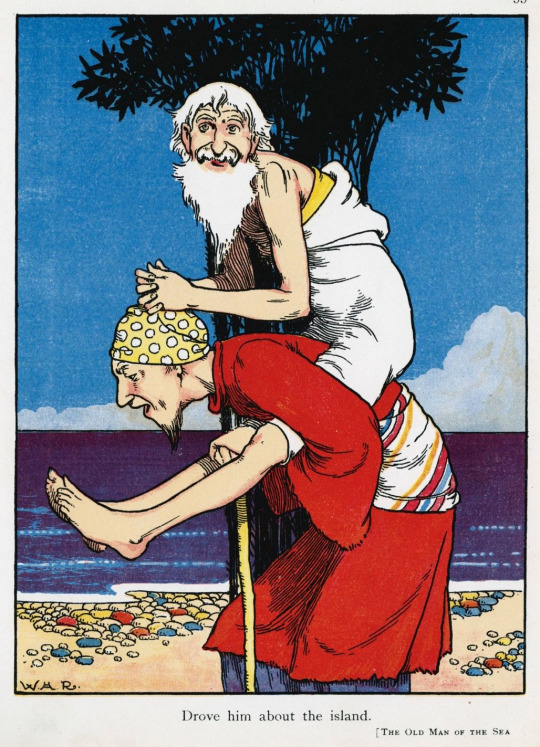

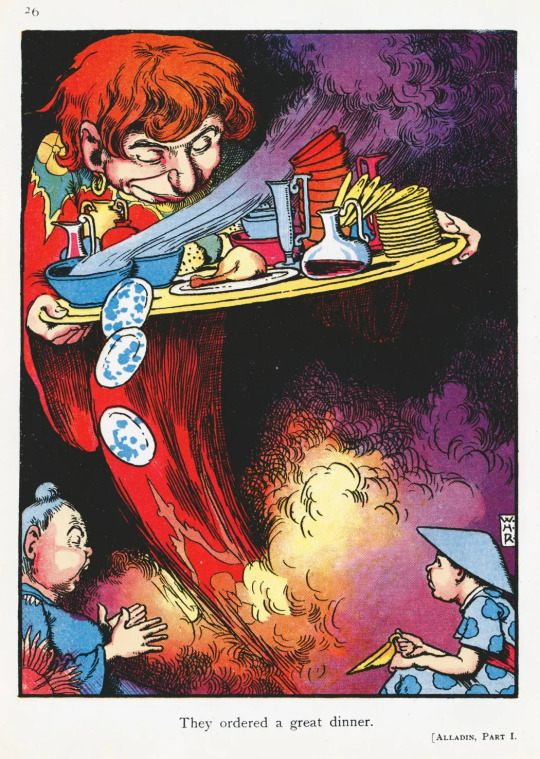

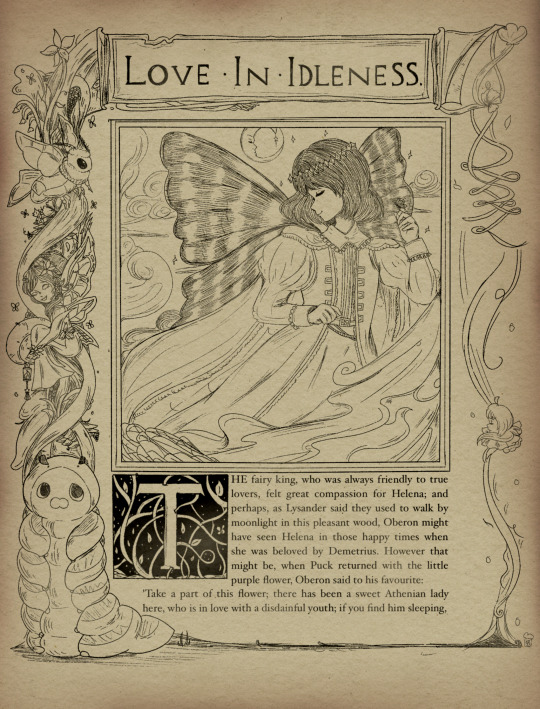

W. Heath Robinson- A Midsummer Night's Dream

#w. heath robinson#illustration#shakespeare#a midsummer night's dream#fairytale#fairy#faeries#midsummer#summer solstice

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

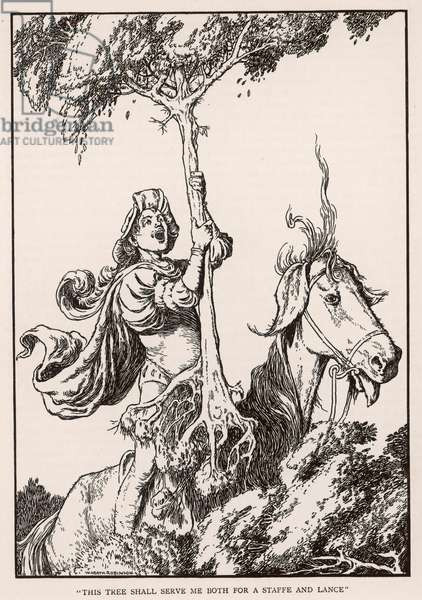

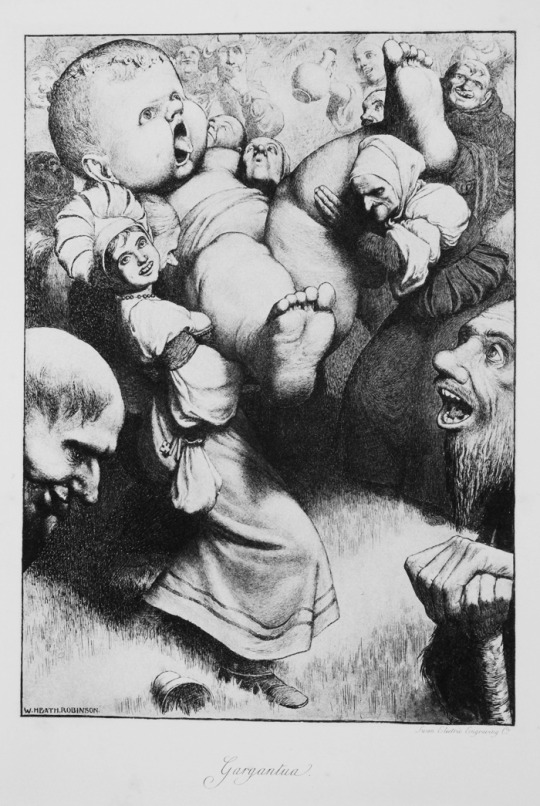

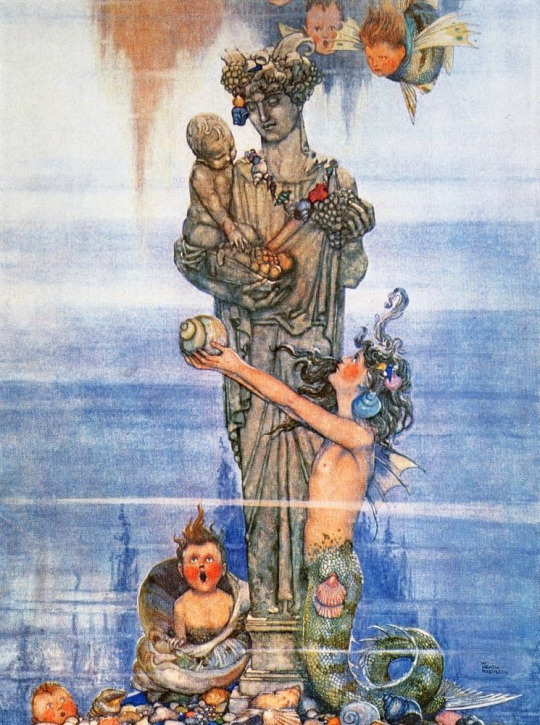

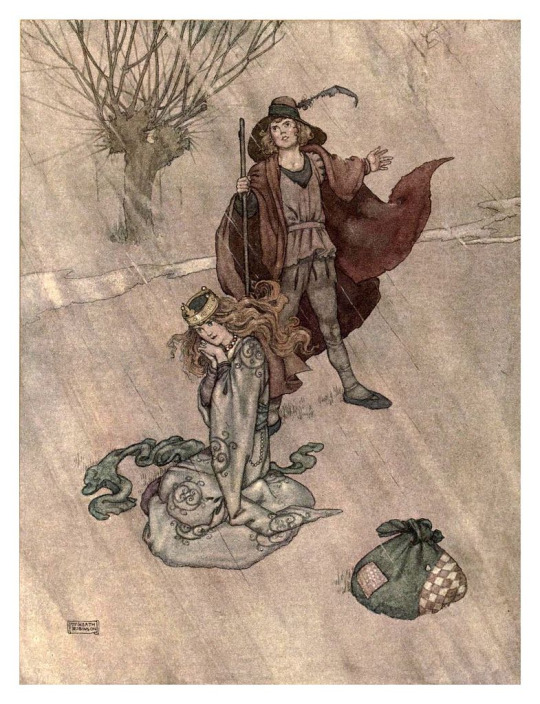

Fantasy sights: William Heath Robinson

William Heath Robinson was an English cartoonist and illustrator of the early 20th century.

He did various Shakespearian illustrations - he most notably illustrated Twelfth Night, in such a way to convey its dark, eerie, ghostly and oniric tones beyond the comedy aspects...

And he also did some very famous illustrations for A Midsummer Night's Dream

Robinson also did an illustrated version of "The Pantagruel and the Gargantua", sometimes grouped together as William Heath Robinson's The Rabelais.

William Heath Robinson was also very as a fairytale illustrator - but since there's a lot more, I'll place them under a cut.

He illustrated Andersen's fairy tales...

He created an illustrated version of "The Arabian Nights"...

And he also illustrated various children-oriented productions, such as Walter de la Mare's "Peacock Pie" or Charles Kingsley's "The Water-Babies".

#william heath robinson#fantasy sights#fairytale illustrations#fairytale art#shakespearian illustrations#shakespeare art#a midsummer night's dream#twelfth night#the arabian nights#rabelais#gargantua#pantagruel

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

excerpt from charles and mary lamb's "tales from shakespeare"

#oberon vortigern#oberon#art#anime#manga#my art#fate grand order#fgo#a midsummer night's dream#shakespeare#fanart#sorry there's something so fun about drawing oberon's first ascension because of how it's so fairytale-like in nature that uOGHGOHGHHH#ill draw vortigern soon enough

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Present fears are less than horrible imaginings.”

#quotes#aesthetics#photography#art#william shakespeare#macbeth#lady macbeth#book quotes#red and black#red aesthetic#dark aesthetic#dark fairytale#dark academia#aesthetic#moodboard#tragedy#inspiration#love#meaepost#english literature#literature#bookblr#studyblr

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm not sure if you've been asked this before but why did you choose Snow White as your display name? (assuming is just a nickname like most people do in fandom spaces) Was it because of the princess or for some other reason?

Yes, dear. ♥️ I did discuss this HERE, but let me clarify it further so it’s fully settled. I’ll add this to my pinned post so anyone curious can read it. ♥️

Why Snow White? ❄️🍎

There are three main reasons, and it will be long. Enjoy.

I. Fairytales

In my early childhood, I grew up in circumstances that didn’t really allow me to explore different types of books. We lived far from any such places, and my parents weren’t particularly aware of their importance.

The only books around were my mom’s horror novels, which never interested me (understandably, as a 6-year-old, parents wouldn’t allow their children to read such material anyway, and I’m still not interested in the horror genre to this day).

The closest books that reflected my current interests in classic literature, philosophy, and psychology were the fairy tales I had access to at that time. I loved all kinds of fairy tales.

Despite some people criticizing them, I found them very helpful in teaching lessons about life—what to do and what not to do in various situations—since they often led to poor or dangerous outcomes. It was the “why’s and but’s” that intrigued me. So, I wasn’t a stranger to fairy tales from the start.

As I got older and social media began to develop (like eBooks, for example), I was able to broaden my horizons.

When I was about 11 or 12, I really got into Shakespeare.

Of course, at a certain age, I also read some cliché romance books, but they never truly satisfied me. In fact, fairy tales were far more interesting to me than those romances.

II. Disney Movies

I also grew up watching old Disney movies and other classic girls’ films like Barbie and similar, though those aren’t really worth mentioning in this context.

In my childhood, I mostly associated with Belle from Beauty and the Beast and Aurora from Sleeping Beauty.

I connected with Belle because she loved reading, and even though she was kind, she didn’t quite fit into the social circle she was part of. This was a struggle for me as well, since I had different interests from most other children and teenagers (literally no one read Shakespeare, and I had no idea why celebrities were supposed to be interesting).

It was frustrating until I got older and learned to blend in (I could have easily been mistaken for an INTP in the earlier stages of my childhood, to be precise).

Aurora, on the other hand, embodied my love for animals and represented femininity and gracefulness. I’ve always been a very girly girl, so she was a fitting representation of how I saw myself.

I admired how she seemed shy, introverted, and dreamy, rather than outgoing. Also, I can totally relate to the idea of sleeping through the entire plot, as I’ve always been a very sleepy person. And honestly, who wouldn’t love the idea of a man fighting a dragon for them? I know I would.

III. The Nickname

Even though I have brown hair instead of black, and rather pale skin, I’ve often been referred to as Snow White by the people around me. (I suppose it’s because of my light skin, dark hair, and the fact that I usually wear a cherry-colored lip tint?) So, it’s actually an established nickname in my private life.

One day, @yonseibananamilk approached me and asked what she should call me. I gave her two options: Snow White or Sleeping Beauty. She chose Snow White, and I accepted. ♥️

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

BSD Gen OC Character Introduction & Fairytale

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#fairytale#bsd organization#bsd generation#aurore perrault#ella perrault#alice caroll#sofia grimm#anneliese grimm#agnete elena anderson#amélie - capucine de villeneuve#julia shakespeare#bella sewell#gacha club

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saltburn makes me wanna throw up. Not because it's perverted (it's not really, it's just got a little cinnamon). No it's got so much symbolism and folklore in that it makes me wanna vibrate out of my skin and I'm not even a folkorist

#they speak#saltburn#i saw someone saying that it's like a proper old fashioned fairytale (not a disney one) and i hard agree#you've got theseus and the minatour#you've got the labyrinth#you've got henry viii#you've got shakespeare#you've got 80s/90s kids tv shows#you've got robin goodfellow and herne the hunter#you've got the oak king and the emperor's new clothes#you've got homoerotic vampires#and vampires in the old sense#you've got lust for a person and their station so much that if you can't have them you'll consume everything and still be left wanting#it's eat the rich coming from someone who is already relatively wealthy and how that translates to not actually helping anyone#you've got a wealthy man cosplaying as being poor to get what he wants#ugh#its a reflection of the poisonous way british classism consumes and consumes and consumes#and it's from the perspective of someone how was hugely benefitted from the system so ofc it's not gonna be an in depth essay on tearing it#all down

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love some good fairytale/Shakespeare briges. And I never realized that I could draw this one:

Jacques Demy's Peau d'Âne and the 1968 Romeo and Juliet movie both are about a youthful love story using red and blue as color-coding for the opposite clans. (Plus both made around the same era and with a similar 60s/70s aesthetic)

#shakespeare and fairytales#romeo and juliet#1968 romeo and juliet#peau d'âne#jacques demy peau d'âne#donkey skin#colors in fairytales

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dang, Ariel, her name debatably double play on her original story self:

I was inspired by the video below. So I could be stretching connections (as yay neurodivergent brain), but Ariel I wonder if was inspired by William Shakespeare’s The Tempest androgynous character Ariel: a gender ambiguous air Spirit. So the original story The Little Mermaid explains Merpeople die they become sea foam, but the titular Mermaid becomes air. So if anyone confirm or disprove my now wondering the animated team of this Disney animated movie meant to do that. That or again I am just finding connections that are not actually that.

youtube

#the little mermaid#hans christian andersen#fairytale#Disney#the tempest#william shakespeare#shakespeare#gender ambiguous#possible non-binary representation#non-binary#neruodiversity#neruodivergent#all connects meme#all connects#lost in adaptation#Dominic Nobel#dom Nobel#review#book Vs movie#movie Vs book#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

File: [Unknown, Ophelia]

Approximate number of times [Unknown, Ophelia]:

sleeps easily: 4; sleeps troubled by nightmares: 7; sleeps alone: 15; sleeps with a girl: 3; sleeps with a boy: 0

kisses someone: 42, loves a man: 3; loves a woman: 1; falls in love: 1

lies to a friend: 5; lies to her father: 11; lies to her king: 3

contemplates death: 18; contemplates own death: 5; contemplates Hamlet and his family and how death seems to follow them like a wretched stench: 2; contemplates Signe’s death as a consequence of their relationship: 3

runs her fingers through Signe’s soft, kinky hair: 32; kisses Signe’s cheek: 24; kisses Signe’s lips: 15; kisses Signe’s bare collarbone: 3; holds Signe’s hand: 17

feels strong: 4; feels strong when she is with Signe: 3; feels ashamed when she is with Hamlet: 6; feels ashamed because she feels ashamed when she is with Hamlet: 5; feels hollow: 3; feels tired of putting up with it all: 2; feels suicidal: [?]

spreads flowers with a distant smile: 1; acts is the fool: 3; is the fool: 1

falls from a branch: [?]; commits suicide: [?]

dies: 1; rises to heaven: [?]; falls to hell: [?]

The way [Unknown, Ophelia] loves:

passionately, madly, coldly, roughly, unkindly, nimbly, caringly, warmly, brazenly, abruptly, softly, toughly, languidly, viciously, purely, sinfully, briefly and forever, thoroughly, without remorse, lustfully, recklessly, honestly

The way [Unknown, Ophelia] lives:

Briefly, rarely mentioned in the page scrawled by a man who paints her the damsel.

Briefly, tumbling from a crib to a kitchenmaid’s bed to a watery grave beneath a tree.

Briefly, in a blaze of fire that tears the castle down.

The way [Unknown, Ophelia] dies:

not floating to her watery grave, the waves and her skirts enveloping her in a poetic embrace

The people [Unknown, Ophelia] has loved:

her father, her prince, her kitchenmaid, her brother

The two things [Unknown, Ophelia] did not say:

1. I love you.

2. I want to die.

Things [Unknown, Ophelia] is not:

fragile

The way [Unknown, Ophelia] dies:

not cursing the heavens for the injustice of her story being overshadowed by a man's, of her life being sacrificed to feed some prince's pain

Truthful thing [Unknown, Ophelia] said to the playwright:

“I was the more deceived.”

The things the playwright decided [Unknown, Ophelia] was not important enough for:

a backstory, a faithful lover, dignity, a kiss, a say in her own future, a birthday, a mother, reciprocated love, a spine, sanity, a life

[Unknown, Ophelia]’s story is entitled:

Hamlet, filed under Tragedy.

The way [Unknown, Ophelia] dies:

not watching her life flash before her eyes, every mistake and good choice falling into the water with her

The first time [Unknown, Ophelia] falls in love:

the world splinters also everything burns also it’s a woman also the Prince is the furthest thing from her mind also her heart sings also fuck her father also Signe’s hair runs soft and crinkly under her fingertips also is the only time

How [Unknown, Ophelia] imagines her lover:

age 5: a boy who will play hoops with her, who will join her on a quest to find buried treasure beneath the castle walls

age 10: a Prince, reckless and dark-eyed, with a smirk already starting to develop

age 15: nothing like herself- a beautiful girl, a princess like she could never be

age 20: a kitchenmaid named Signe, with dark hair and dark eyes and dark skin, curves glistening in the candlelight and smile a beacon of hope

The things [Unknown, Ophelia] does on-page:

drifts from man to man, goes mad in her mind, falls in a lake, drops flowers into people's laps, passes quips to a prince in a theatre, breaks apart into a million insane fragments for a Prince's sake

The things [Unknown, Ophelia] does off-page:

drifts across the underside of a lake, goes mad in her heart, falls in love, drops kisses onto Signe’s cheeks, passes bread between hands in a darkened hallway, breaks a girl's heart with her death

The flowers [Unknown, Ophelia] gave away:

Rosemary, for remembrance

Pansies, for thoughts

Fennel, for you, and Columbines

Rue, for you to wear with a difference

A Daisy, for innocence

But no Violets, for they wither’d all when her father died

The flowers [Unknown, Ophelia] gave herself:

Rue, for repentance, regret, everlasting suffering, and sorrow

The way [Unknown, Ophelia] dies:

[?]

The scene about [Unknown, Ophelia] that ends up immortalized:

Her descent, into madness and death, written by a playwright who writes suicide romantic rather than devastating.

A descent, then:

When Hamlet descends into madness, it is heroic. It is princely. His suicide by sword- for what else is it, truly- is considered truly regal.

When Ophelia descends into madness, it is tragic. It is delicate. She is the flower wilted, the rose with its thorns cut. She is the aftermath, the prequel, the death unimportant save to further a plot.

[Unknown, Ophelia]’s name becomes:

an insult, a title for a lover scorned, a derisive nickname, a contemptuous glare, a metaphor for madness

not a compliment, an appraising glance, a name for a lover true, a loving pet name, a simile for sympathy

What happened to [Unknown, Ophelia] after the funeral:

The story does not say.

The way a kitchenmaid grieves:

Unnoticed, in the midst of death after death. First her lover, then the Queen and the Regent and the Prince. In a kingdom enveloped by grief, a kitchen maid's tears go unnoticed.

A princess’s hair ribbon:

Tucked under a kitchenmaid’s skirts.

The way [Unknown, Ophelia] dies:

Loved.

#hamlet#fairytale retelling#ophelia#sapphic#lesbian ophelia#poetry#writeblr#my writing#i wrote this ages ago but i rediscovered it and i LOVE it#tw sui implied#at least that's one interpretation#shakespeare#retelling

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Do you love works in the public domain, whether it’s fairytales, mythology, or the works of Austen and Shakespeare? Do you ever want to explore all the ways these old stories have been retold over the course of human history? Well then I’ve got the podcast for you!

#podcast#in each retelling#fairytales#mythology#william shakespeare#jane austen#books#movies#I really can't back out of this now omg omg omg

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

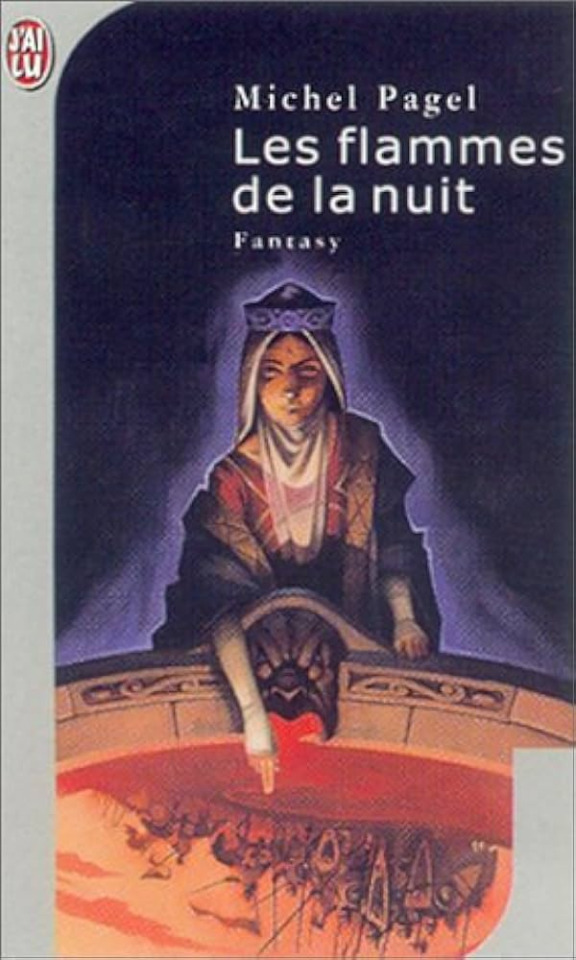

French fantasy review: Les flammes de la nuit

I do wonder why I make these posts – about French novels that I do not think were translated in English, reviewing them in English on an English-speaking website… I do know that some French people are lurking around under a mask of Englishness, but still, most people here are those that I guess will never have access to the novels I review… But oh well, I’ll do what I’ll do, as bizarre as it may sound: and what I’ll do is talk about the French fantasy.

I already translated a long time ago some articles written about the French fantasy literature, but here I will share my personal thoughts and favorites when it comes to this genre of fantasy that is considered “foreign” and “exotic” by the simple virtue of… not being written in English. France is the land of literature, and has already bred, nursed and thoroughly exploited and theorized the two genres that gave birth to the fantasy and yet are so hard to translate in English: the merveilleux of fables and epics, the fantastique of 19th century supernatural tales… Why wouldn’t France have fantasy too? The name of the genre stays English, unfortunately, but it has enough echoes and roots within our own féeries and surnaturel to find a place prepared for it since centuries…

Anyway, enough lyrical: let’s get into the meat of the subject, let’s dig to the bone, and I want to begin with “Les flammes de la nuit” (The flames of the night) by Michel Pagel.

When I picked up this book I was not expecting anything precisely from it, I was just curious. I had only ever heard of Michel Pagel through a huge and dark series of his called “La Comédie Inhumaine” that everybody loved and that was renowned as a dark and violent fantastique, but I never read it. The reason I picked up this book was due to its relationship with fairytales. If you do not know I am REALLY into fairytale stuff, I even have an entire sideblog just to talk about fairytales ( @adarkrainbow ). And this novel was advertised as being a fairytale subversion, so I thought, let’s get into it! [EDIT: I actually also had heard of Michel Pagel through another work of his that now I will definitively read, Le Roi d’Août, a supernatural historical novel that faithfully retells the biography of the king Philippe Auguste… While filling some historical blanks in his life by the intervention and encounter of the supernatural folks hiding within the French landscape.]

Most notably, when I checked briefly online reviews to see if I should get the book, all agreed on a same thing: all said that the book was absolutely great, with wonderful ideas and powerful characters… until the very end which had disappointed everybody (at least at the time the reviews were made, so by the 2000s/early 2010s). As a result I went into this novel saying to myself “Okay, the beginning and middle will be great, the end will be bad, get ready”. And… what a surprise! The ending was not bad at all. A bit confused and rushed but… it was a good ending. Or rather a fitting ending (because it is not a happy or positive one, nor is it a negative one – it is a grandiose, tragic, bittersweet but hopeful ending perfect for the tone of the novel and the project the author set upon himself). If you ask me, all the reviews were wrong – and I had been deceived for the best, since the novel surpassed what I was expecting. Now, I won’t throw the stone, I actually understand why these readers were disappointed with the ending and I’ll explain why (spoiler: it is a question of context and point of view). For now, I’ll simply say that I greatly love this novel which definitively goes into my top French fantasy novels.

In terms of editions and publications, a few indications… This is one of those typical edition thingies that are so peculiar to France. The novel was originally published as a series of novellas. Four in total, between 1985 and 1987, in the “Anticipations” collection of the Fleuve Noir publishing house (it was still in this era where in France fantasy and sci-fi were sold together as one and the same). Later, the four novellas were collected into one full volume, one novel divided into four parts. This complete volume was published in 2000 (in a small format by the J’ai Lu Poche Fantasy, in a large format by Denoël collection Lunes d'encre), and it is both the version I read and the one most people refer to when talking about “Les flammes de la nuit”. I do not know if the text was edited or slightly rewritten for this new format – I don’t think so, but I have to admit the text felt so much like an early 2000s story I was quite surprised it came from the mid-80s… There’s quite notably the fact the main character is openly bisexual, but hey, the 80s in France were quite a time too… More recently in 2014 Les Moutons Electrique republished the integral in a large format, and then in 2022 in a middle format, proving this novel’s great and enduring success.

[Note: As I am writing this post I made a quick checklist and I just discovered that Michel Pagel actually was the French translator of Neil Gaiman’s Anansi Boys and American Gods, as well as of Gary Gygax’s Monster Manual for D&D… Wow, that was a total surprise – and it does explain some things, I notably see how Neil Gaiman’s writing could have had an influence over this novel…]

Let me briefly set you in the mood the very first pages plunge the reader into… We follow an old man who is travelling on a pilgrimage to a great lake at the center of a medieval kingdom name Fuinör. He isn’t just any old man: it is but one of his masks. He is the Enchanter, a great and powerful wizard as old as the universe itself, a supernatural being known to take many forms, and who can be as much a wild animal of omens as a seducing woman luring knights to an uncertain doom… Once he reaches the great lake, called the Mirror for its still waters form the perfect reflection of the sky and the sun above it, in a great burst of light, the sun disappears… and reappears. But the sun is not golden anymore: it is green. And with the sun everything changed color within Fuinör: the sky is not blue but indigo, the sea is the color of emerald, the trees have blue leaves, human skin is orange… And this is perfectly normal, for in the world of Fuinör, every seven years the sun is reborn above the lake, turning into a different color, and with it everything in the world also changes its hue. And as such, seven year by seven year, the light goes through all the seven colors of the rainbow…

This sets the stage for what “Les flammes de la nuit” is. And it is many, many things, a story which likes the sun of Fuinör undergoes different stages and tones (the serial publication helps this feeling of slow transition and evolution throughout the novel).

The story opens as an open, cynical and dark parody of fairytales – for the world of Fuinör is a world of stock fairytales. It is a world in which, when the king has a daughter, seven fairies, each for each color of the rainbow, arrive to bless her with all the usual gifts – beauty, grace, singing – while carefully avoiding anything like strength or intelligence, for these are male gifts for those destined to rule. It is a world in which, when the queen gives an heir to her king (and there is always only one king and one queen), she must die in labor – and if she happens to survive… then the royal doctor must prepare a certain powder to make sure the queen respects the tradition. It is a world where barons often declare themselves vile rebels and wicked usurpers and try to overthrow the high king… but they are always defeated because the law claims there can only be one rebellion at a time, and each baron must warn in advance the king and let him decide how, when and where he wants to do the battle. It is a world where there is a land for each thing – quite literally. Fuinör is divided into different “countries” each dedicated to a specific area: there is a land of Hunting, where the hunts take place, and any hunting elsewhere is outlawed. There is a land for War, and nobody would ever think of waging war elsewhere than there. There is a land for Love, and all love and romance and sex can only take place within its boundaries. Such as the laws, and the customs, and the traditions, and they have always been since the beginning of time…

Fuinör is a mix of all the classical fairytales and the traditional medieval romance and Arthurian tales – but all taken to an extreme. Fuinör is a world stuck in an endless cycle of loops, where the events all repeat themselves in the same way with predictable end, where everyone is given a specific role and fate since birth, where everything is stuck under an order that has been decided by ominous gods a long time ago, and where no surprise and no disorder can ever happen. The brave knights in shining armor always win the heart of princesses, the high king is always victorious of anyone that tries to take his throne – and if someone ever does, THEY are the rightful high king and the other is the usurper – and the peasants… well who cares, they don’t count, they’re not even considered human, they are just here to work and be background props.

But things will change… Things will change thanks to the Enchanter, who decides that when the new princess of the kingdom is born, little Rowena, she shall receive a gift no other princess ever received… the gift of intelligence. An intelligence that will allow her to understand the absurd logic of her world, and use the sclerosis of archetypes and the rigidity of millennia-old customs to her advantage. An intelligence that will make her greater and more powerful than anyone – an intelligence that will threaten the very existence of Fuinör… Thus is the beginning of “Les Flammes de la Nuit”.

The beginning of the novel, Rowena’s own youth and story, is clearly designed to deconstruct all the archetypes, stereotypes and point out all the bad side of both the generic fairytale (especially Disney’s version of fairytales – the novel is filled with jabs at Disney and the “Americanized” fairytale, the seven fairies being basically Disney’s fairy godmothers mixed with Glinda from The Wizard of Oz MGM movie) and of the Arthurian romance as we know it today. It does not mean Michel Pagel hates those genres, quite the contrary! This book heavily pays homage to both domain, in which Pagel has clearly a great interest. In fact, this book is much more “medieval romance/Arthurian epic” than fairytale in tone, and while anybody who saw the Disney movies or read Perrault will get the fairytale references, I do believe someone with zero knowledge of the Arthuriana will miss a LOT of cultural jokes and clever references in this text. From the get go the Enchanter is clearly supposed to be inspired by Merlin from the Arthurian myth – but not the Disneyified, Americanized Merlin. The original Merlin, Myrddinn, the mythical, legendary, ambiguous and terrifying entity that exists beyond shapes and times and manipulates fate as he pleases… In a similar way, if you haven’t done any research on the evolution of the legend of Avalon you won’t get how twisted and cool the climax within the domain of the Fairies is… But I won’t reveal too much spoilers.

But loving doesn’t mean being uncritical, and this book is clearly the result of Michel Pagel thinking about what he adores, and highlighting in an entertaining way all that is wrong with those classical tales. The first part of the story is centered around Rowena, this intelligent and daring girl born within a world of the worst fairytale stereotypes and outdated medieval chivalry. And as she grows up she gets to explore what others were too afraid to explore, she understands what nobody understood, she gains power nobody had access to before… all the while suffering from what her world really is: unfair, classicist, sexist, misogynistic and abusive. And this begins already the bittersweet tone of the novel. At the same time we have a very funny parody that enjoys dark humor and plays all the code of the traditional “fractured fairytale”, and yet it alternates with very sad and dark moments where Rowena is confronted with the cruelties of such a universe and understands why being an intelligent girl in a world where women are to be submissive and stupid can be dangerous. But all is in fact set and prepared for her own fate, prepared by the Enchanter in person: for Rowena will become… the Witch.

And of course I love this, because who doesn’t get to love a dark retelling of fairytales, who doesn’t like a faithful retelling of medieval epics with an acute sense of modern values clashing with outdated morals, who doesn’t get to love the story of how a girl became a witch-queen? But… I think this is where the “fracture” with a certain part of the audience happened. I will return to the reviews I talked about above: many people thought the ending was worthless or were betrayed by it. Having read the novel I understand why they felt that: in their own words, they were sold and expected a feminist retelling of fairytales about breaking conventions and stereotypes. They were sold the story of a girl being a hero, and the old fairytale clichés being mercilessly mocked and denounced and beaten upon. And that was it for them. As such, yes, the ending probably disappointed them… Because it isn’t what the story is about.

It is made clear in the beginning of the story: being a Witch is not a pleasant thing. It is not a power fantasy. It might look like it, and Rowena uses it as such, but we are clearly warned that a Witch is still an unpleasant, dangerous and sometimes disgusting existence which will require suffering, both inflicted by the Witch and received by her. It is in such a path Rowena sets herself upon – and this is part of a greater scope of things. Rowena is the main character of the novel, but she is part of a wider plot by the Enchanter. The Enchanter wants to break the endless, frozen cycle of Fuinör. He wants to destroy those paralyzing traditions and this unnatural order. He wants to plunge back the world into chaos – a benevolent, needed, positive chaos, but a chaos still. And one of the very strong messages of this tale is: a need to go beyond Manicheism. To go beyond simplistic duality or archetypal characters. What Rowena, and the Enchanter, and others later, bring is complexity. The entire point of the novel is to go beyond the idea that there is all good and all bad, clear cut good and evil, black and white. As such, slowly as the cosmic battle wages on, as the Tradition and the Divine Law unravel, the characters grow into shades of gray as all their values, their positions and their allegiances are redefined, put to test or exposed, as the very machine of the universe starts to be pulled apart. Characters that start out as nice and lovable heroes turn into selfish villains. Characters that appear as flawed jerks and unsympathetic narrators learn from their mistake and grow heroic and wise. Courageous warriors grow into cowards, figures of sanity become mad, and this entire novel is the story of one huge revolution where everything changes: moralities, social hierarchies, laws of justice, and even genders! (The novel notably features an exploration of non-binary genders through one specific character – or three depending on how you count it – not including the various shapeshifting of the supernatural entities, which again helps make it resonate with a modern audience despite being around for quite a long time)

As such, no, this story is not a feminist power fantasy, and those that go in expecting this will be disappointed. It is a much, much larger and complex story about an entire world, about this fictional place born out of the classic fairytales and the medieval romances and the Arthuriana, and how this thing is confronted with its own choice of “evolve or die”. And this is still a very powerful and admirable story, which at the same plays subverts tropes, while also playing many clichés and stereotypes straight, but with a clear knowledge of this. Some people in the reviews said they were disappointed that ultimately, it seemed that Michel Pagel, in trying to break down and denounce clichés, ended up himself reasserting those same clichés. And I honestly do not think it is the case – as the novel is rather a strong defense of “We should get rid of all clichés and stereotypes, because they’re always going to trap us, no matter on which side they are”. But again, I can’t reveal too much without spoiling this long modern epic.

A good example of why for example this novel isn’t a pure “feminist fantasy” as many believed: Rowena is not the only main character. There’s another one, a “male counterpart” so to speak of the Witch-Queen in training. A character who doesn’t really have a name (well he has one but it is kind of a spoiler domain), and whose own backstory forms the second part of the novel (or the second novella of the series). A character who lives in a different part of Fuinör, and also should have been trapped in a cycle of millennia-old rituals and binding traditions and unfair customs, but whose fate changes completely due to the interventions of the Witch and the Enchanter… Except that, whereas with Rowena we had a bittersweet parody of Disney movies and traditional fairytales, with this second character we rather explore a deconstruction and attack of a different type of folktales. There is notably a brutal takedown of the whole “Journey of the Hero” system and the “Monomyth” idea. And I don’t say “brutal” lightly: this part of the novel is very, very brutal, physically speaking. Because this second main character is the helpful companion on the road in fairytales that helps the hero get the girl while himself having nothing. He is also the stock archetype of the Fool doomed to make mistakes and be ridiculed or punished. And he is the False Pretender, the False Hero of fairytales here to put in value the True Hero… Except we are told the story through his point of view. Except he is not evil, he is a guy who is trying his best but is put in an unfair position and only gets endless bullying. Except the True Hero doesn’t seem to be deserving of his position, and the question is raised of “Maybe the other guy should have been the Hero”… But here we shift into a fantasy version of what Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil” was and we fully explore the magical dystopia that is Fuinör.

Overall I do have to say… I think so far the closest thing I have seen in terms of overall tone and ambiance, in the English-speaking world, to compare these works… would be Dimension 20’s season “Neverafter”. Both works deal with a very funny parody but also very dark twisting of fairytales and folktales. Both deal with characters being abused and going through horrors at the end of great cosmic powers and otherworldly narrators. Both tread between comedy and horror ; and both deal with the protagonists’ attempt at breaking endless cycles set upon by fairies (because, in both Pagel’s novel and Dimension 20, the fairies are one of the numerous antagonists as the ruthless and terrifying enforcers of the “laws of fairytales” that get everybody stuck in their roles and functions). Of course, the two works are very different beyond that… But there is a common bone.

A final element I need to add so that you get a full understanding of this novel: Michel Pagel placed his book under the patronage of Shakespeare. And if the fact every part opens with a quote from one of Shakespeare’s play, from Hamlet to Macbeth passing by Romeo and Juliet, King Lear and more, wasn’t enough, anyone versed in Shakespearian studies will see how among the many archetypes and stock tropes of the novel, those of Shakespeare also regularly pop up. Someone once wrote that this novel started out as a fairytale parody, but slowly evolved into a Shakespearian tragedy, and I cannot agree more. It does start out as a dark and morbid but entertaining parody – and then things get really brutal, really violent, really sad, really serious, and we enter a terrible and dreary fantasy, but still very poetic and very human, that moves towards a universe where all of Shakespeare’s greatest cruelties fit right at home. The novel most notably has a lot, a LOT of fun exploring the Shakespearian archetype of the “Fool”. There’s almost two handfuls of characters that each is meant to explore a different aspect of the Shakespearian Fool, each expressing a difference nuance of it (the famous non-binary character is one of them, paying homage to the typical gender-plays and gender-questioning within Shakespeare’s plays) – and I am glad to be a Shakespeare enjoyer when reading this novel because again, a random person with zero Shakespeare knowledge would miss a lot of things. (Which again is I believe the reason the Internet reviews attacked this novel, there is a certain degree of medieval and literary knowledge needed to get the parts of this novel that pay homage to the older texts and more ancient roots of the clichéd, Disneyified myths we have today… Without it the novel can still be read, but it might seem much weirder and bleaker than it truly is)

Finally a flaw, because there needs to be a flaw in every review, it can’t all be glowing: I do admit that of the four parts composing this novel, the fourth one did felt unbalanced. Notably the author seemed to spend too much time, description and effort on characters barely introduced (which at the ending climax of a story is not good), and not enough on the characters we were following since the very beginning… But I will blame that on the fact the fourth part was originally meant to be an independent novella read one year after the last part was published. I do believe that, while putting the full series in one volume is quite convenient if you want to buy something to read over holidays, it does make one feel a bit tired by the end since you literally absorb four years of writing into one go… So, my advice would be to enjoy this book by making pauses between each part, to not do an “overdose” that would be too abrupt.

Or two flaw, I feel generous: when it comes to the second part, it felt a tad bit repetitive. A tad bit too much repetitive. I get that we are supposed to have a hopeful character that is trying his best to make things work and obtain what he wishes for, and we are supposed to fully get the injustice of the situation and the hardness of this world… But precisely because of how it explores casual violence and vicious brutality, the repetitiveness is felt more. It’s a type of “break the cutie” (who isn’t here so much a “cutie” as a morally neutral human being) scenario, and I am not well placed to say if the author did just enough or too much.

[Edit: I do love how the original covers for the 80s series tried their best to make it seem like a full horror series... when it is not]

#fantasy novel#fantasy#book review#fantasy book#french literature#french novel#michel pagel#les flammes de la nuit#french fantasy#medieval romance#dark fairytale#neverafter#fairytale parody#deconstruction#subversion#shakespearian#shakespeare

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's magic in every corner if you clean your eyes to watch carefully ✨

This is for sure at the top of my all-time favourite photoshoots -featuring what's most likely to be the most delicate corset I've ever made 🦋 You can learn more about this gorgeous corset here 🦋

🧚♀️ Marta Pardo

📷👗👑 M Pardo Couture

📍 Alcalá de Henares, Spain

#fairycore#a midsummer night's dream#shakespeare#titania#queen of the fairies#18th century stays#corset maker#m pardo couture#acotar#costume designer#fairytale#fashion design#goth fairy

3 notes

·

View notes