#expat life in russia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

wanderlust destinations, societal norms, anthropology, Russia, documentary, travel vlog, hidden gems, off the beaten path, documentaries, tan globe, cultural exploration, unique customs, countries with more females than males, which countries have more females than males, discover countries, travel documentary, expat life in russia, best country to find a traditional wife, travel guide, strange traditions, societal explorations, anthropology travel

#wanderlust destinations#societal norms#anthropology#Russia#documentary#travel vlog#hidden gems#off the beaten path#documentaries#tan globe#cultural exploration#unique customs#countries with more females than males#which countries have more females than males#discover countries#travel documentary#expat life in russia#best country to find a traditional wife#travel guide#strange traditions#societal explorations#anthropology travel

0 notes

Text

For the past few days, I’ve been binge watching content from many #Russian #expats and others who still remain in Russia giving us an #insight into their #lives. https://halflifecrisis.com/hlc-articles/lets-talk-about-the-russian-people… To truly understand #Russia you must need explore their vast #history. It's eye-opening.

#half life crisis#baqueroalvarez#authoritarianism#propaganda#politics#worldhistory#russia#expats#russo ukrainian war#war in ukraine

0 notes

Text

Over the past two years, stories of foreigners moving to Russia for ideological reasons have become a recurring theme in the country’s media. In October 2024, Russia’s Interior Ministry reported a surge in applications for temporary residence permits from citizens of “unfriendly nations.” Many of these expats, dissatisfied with so-called “LGBT propaganda” and feminism in their home countries, have turned to YouTube to share their experiences of life in Russia and promote “traditional values” — often relying on sexualized portrayals of Russian women to draw in viewers. Since 2023, the Russian government has poured millions of rubles into promoting the country’s image as a haven for disillusioned Westerners. The reporting project Glasnaya investigated how successful these YouTube trends have been and what narratives pro-Russian foreign vloggers are spreading. Meduza shares an abridged English-language version of their reporting.

Samuel Hyland, a 46-year-old from Nottingham in the U.K., moved to Russia in the early 2000s, settled in Vladimir, and eventually gained citizenship. Hyland speaks decent Russian, having developed an interest in the language as a teenager after a Russian family moved into his neighborhood.

In 2017, he launched a YouTube channel, Sam’s Russian Adventures, where he documents life in provincial Russia in English. His channel only really took off in 2022, though, when he began posting videos about exploring abandoned places and life in Russia under Western sanctions.

A woman named Milena frequently appears in Hyland’s videos. In one clip, she strolls with him through a village wearing tight, neon workout gear and holding a cardboard sign that reads, “Looking for a husband.” In another, she rocks back and forth on a piece of children’s play equipment in a white corset and a long silky black skirt, as she gazes up at Hyland. “Would you fly in my plane?” she asks. “Of course! You’re such a smart and beautiful girl,” he replies.

Hyland has found a simple formula to attract viewers: clickbait titles. Choice examples include “Russian Girl Shows Me Her Ass,” “Englishman Invited to GIRLS ONLY Party in RUSSIA,” and “She told me THIS was forbidden in RUSSIA.” The actual content is mundane — looking at art at a market in Vladimir, attending a yoga festival, or getting yelled at by a local woman for filming.

He pairs the provocative titles with voyeuristic thumbnails catering to the male gaze. In one, a young woman in a tight black dress that exposes her cleavage licks a popsicle while locking eyes with the camera. The video, titled “I got SCAMMED in Russia,” is about Hyland getting swindled while buying a car during his early years in the country.

Hyland, whose videos attract anywhere from a few thousand to half a million views, says this is what his audience wants. He’s complained that YouTube deprioritized his content after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine since he shows the “real Russia” without “Western propaganda.” In his videos, Hyland emphasizes that Russia is a country of “traditional values,” where women view men as providers and continue to care for their appearance after having children — unlike, he claims, women in the West.

When Hyland learns that a woman he’s speaking to has kids, he showers her with compliments and praises Russian women for their ability to maintain their looks. In one video, a woman remarks, “When you watch TV, [Western women] are all plus-size. Here, everyone takes care of their body, diet, [and goes to] the gym, even after having two kids.” Hyland enthusiastically agrees.

The British YouTuber has tried his hand at various ventures while living in Russia. In 2012, he opened an English language school in Vladimir, but the business failed. Now, Hyland focuses on his two YouTube channels and offers consultations for foreigners interested in moving to Russia. His website also features a section called “Russian Dating.” Hyland claims foreign men and Russian women often ask him to set them up. So far, though, there’s just one sample profile on his site.

‘Traditional values’

English-language YouTube channels about life in Russia occupy a small niche, but topics about relationships with women and discussions of feminism are quite popular. Videos on who should pay the bill on a date, the differences between American and Russian women, and how to win over a Russian woman often attract hundreds of thousands of views.

Many of these channels are run by foreigners who moved to Russia after marrying Russian women, says Natasha, the creator of the English-language YouTube channel Natasha’s Adventures, where she documented life in her hometown of Spassk-Dalny in Russia’s Far East before emigrating. “These are people who adhere to so-called traditional family values and have become disillusioned with the West,” she said. “According to them, rainbow flags are everywhere in the West, but in Russia, the traditional family is still preserved. They’re often well-off individuals with Western salaries, savings, and property.”

One of the vloggers Natasha is talking about is former U.S. Marine Daniel Castellon. He came to Siberia in April 2022 to explore the region and “test himself,” but when he landed in Irkutsk, he struggled to find anyone who spoke English — except for one woman. Two years later, they got married, and Castellon shared the wedding on his YouTube channel, Wild Siberia.

A former Californian, Castellon calls Siberia the “new frontier for freedom.” He purchased land in the town of Slyudyanka on Lake Baikal, where he grows radishes and goes fishing with his father-in-law. Castellon says he appreciates that Russia, unlike the U.S., respects “traditional values,” and he says he admires Russian women for being “wise” and desiring men who will “protect and love them.” In his view, such women are becoming harder to find in the U.S. and Europe due to “LGBT propaganda.”

He also believes masculinity is rooted in military service, lamenting that the U.S. military now recruits LGBTQ+ people. In one of his videos, Castellon says the U.S. is currently being run by “weak men,” which is dragging the country downhill, while Russians are constantly dealing with harsh weather, sanctions, and global pressure, “so they’re always creating strong men.”

Castellon views Russia’s war in Ukraine as an opportunity for young men from small towns like Slyudyanka. He admits that there have been casualties but says “not all will die, obviously,” adding that the money from Russian soldiers’ “exploits” will benefit the economy in their hometowns.

A ‘moral refuge’

According to Natasha, videos about Russia on YouTube can be fairly lucrative. “There isn’t much content about Russia in the West, especially in English. The country has always been interesting to foreigners, even before the war — some studied Russian, others had roots here. After the war started, many also became curious about Russian politics,” she explained.

The Russian government has been working to capitalize on this interest, positioning the country as a “moral refuge” for Westerners who share “traditional family values.” In 2023 and 2024, the Presidential Fund for Cultural Initiatives allocated about six million rubles ($60,000) to a competition called From Russia with Love, which aims to fill the gap in content presenting Russia as “an attractive country to live in.”

English-speaking foreign vloggers are encouraged to select video ideas from “patriotic” Russian YouTubers and collaborate with them. “There are long-standing ideological trends justifying leaving Russia for the ‘West’ as practically the only positive path for progressive youth,” reads the project description. “At the same time, many educated, well-earning residents of Europe and America, for political or ideological reasons, no longer wish to live in these countries and are either considering Russia as a destination for relocation or have already moved here.”

Since September 1, 2024, foreigners who share “traditional Russian spiritual and moral values” can apply for temporary residence in Russia through a simplified process. Applicants are not required to know Russian, or the country’s laws or history. Pro-Kremlin foreign vloggers have actively been making videos about the new decree, often using the opportunity to promote their own products, such as consultation services for those considering moving to Russia.

Some of the most notorious foreign vloggers sit on From Russia with Love’s panel of experts. Among them is Tim Kirby, who immigrated to Russia from the U.S. in 2006. Kirby says he made the move after his daughter’s school principal in the U.S. threatened to involve child protective services if she continued to miss classes.

In Russia, Kirby worked as a host on various propaganda outlets such as Russia Today and the Christian Orthodox news network Tsargrad TV. He speaks fluent Russian and got Russian citizenship a few years ago. Kirby runs a YouTube channel where he documents his travels across Russia. Unlike many other English-speaking vloggers, he rarely features Russian women in his videos. “It’s much better for society when men are valued,” he claimed. “When a woman admires a man, she bonds with him — and a family and a marriage begin. But when a woman is put on a pedestal, she ends up alone, buying cats and boxed wine at 40.”

The project’s creators envision these “experts” providing “guidance” to Russian YouTubers, helping them see their hometowns “through the eyes of foreigners.” They also hope to leverage the “wow factor” of titles like “Expat Vloggers Shocked by the Real Russia” to create viral content and attract large audiences.

In 2023, the videos produced for the competition exceeded expectations, garnering more than a million combined views (compared to the anticipated 100,000), according to the competition’s website. One winning video, about how “Crimea has transformed over 10 years as part of the Russian Federation,” garnered more than 1.4 million views. However, the results were mixed. Of the 10 videos featured on the project’s site, four received only a few hundred views, while another four ranged from 2,200 to 11,000 views. As of this writing the least-viewed video, Union of Fathers, hasn’t even broken 300.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a very important article. I believe china is doing the same.

Trace their money. If they’re paid to have relationships with people, they should be expelled.

I’ve always felt something fishy going on with every russian expat I know sympathizing russia but fucking living in United States. that is very different from other countries when they know living in america is a better life.

2 countries of expats and immigrants most reliable that they’d be criticizing america in favored of where they came from. China and Russia.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are a few things I want to have happen to Marina and Elijah in Expats, which, inspired by Everything is Illuminated, is going to include a road trip through rural Ukraine, possibly to hide out at the family cabin.

-- Fun bit of trivia: Elijah Wood had to get a motorcycle license for his role as a teenager in Deep Impact, because one of the scenes required him to ride a motorcycle down a stretch of highway. Presumably, he still remembers how to do it, even if it's been a while and even if his license is no longer valid. This might tie in nicely into a scenario of "we're in the middle of nowhere and our car broke down and the nice man who is essentially the only one in this town and has worn the same hat for ten years has only a motorcycle to lend us." And when Elijah questions what to do if he's stopped and asked for his license, which he doesn't have on him and which is probably expired, he's told that 1) there's like one police officer for the entire county, and 2) in the unlikely scenario you are stopped, just give them a bribe and be done.

-- A rural location that includes the following piece of directions: "Drive until you can't drive anymore, and then get out and walk." (which kind of begs the question of what do you do with your car, do you just abandon it and is it going to be ok, but that's another story). Granted, this is a little more likely to happen in rural Russia than in rural Ukraine because the distances are greater, but I just think this is everything when it comes to rural locations. Bonus points for a dying village where there are more houses than residents, and the only reason Marina's family still has the cabin is because, in that remote location, you can't give real estate away, nobody wants it.

-- a joke about the fact that "Marina" means "boat parking lot." Possibly one of Elijah's friends/costars is fond of this joke. AhemDomAhem.

@from-the-coffee-shop-in-edoras @konartiste, @konjugaltdien I am tagging you because I've realized this is basically modern day LOTR/FoM in some ways - innocent, blue-eyed person flees a great peril with the love of his life.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the voice actor for artemy in p1 works with children. ough that makes so much sense

#he's also 😳😳😳#he's british 😔😔#but he fits so well oughhhhh#pathologic#pathologic 2#artemy burakh#мор утопия

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Honestly, everytime I see a new photo of Till during Rammstein downtime, he's always in a different place - Dubai, Mexico, Costa Rica, Russia. He's really living his life ro the fullest. Most musicians stay at home after touring because they travel a lot, but you really see nothing and never fully relax whilst on tour, even though you can be in wonderful new cities every night.

Love that for him and no doubt he brings (grand)kids along with him.

On a side note -- myself being from the Eastern block, I've noticed that we have that extra push to travel and see things as much as possible. It really doesn't go away.

Interesting idea, maybe his east-german upbringing indeed factors in with his travel-enthusiasm, but i also think Till is very interested in people, especially in people who are a bit different than others, in whichever way. He must have so many friends and acquaintances by now 🌺

From what i gather from posts during the 2022 tour, he often meets up with the east-european circles (maybe expats from russia?) in various places.

I checked that new pic's original source, but it's in cyrillic and i'm can't read that; not sure if that pic was taken in Russia (which would be.. well..unexpected, given the current situation in the world) or if it's somewhere else..

No idea if family comes along on his travels, he is very private about his family i think, and more power to him, in that way they can at least travel with some sort of normality 🍀

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

my dad's brother (the one who used to live in russia and whose son is a neonazi who maybe tried to kill him kinda (a story i never got around to telling on here)) who was apparently living in costa rica which i didn't know, met a woman who was on vaca there and then moved back with her to some place in germany, and is currently working in her cafe that she otherwise runs totally solo and they're soon going to go on some long vacation themselves

there's a ton to unpack here, the first item being: if she was a tourist, how long did he even know her before he moved across the fucking globe ? a week? a month? does that mean her cafe that she runs solo was just closed the whole time? and now will be again? how can she afford to do that??

also idk how healthcare works for expats in either costa rica or germany but i assume that hiv medication isn't magically free there, so... how has he been getting money to pay for those meds on top of his life and now this new vacation? or is she bankrolling him, in which case just how profitable is this little cafe that's run by one person and seems to potentially just close for weeks at a time?

as usual his life continues to be fascinating. my dad already thought he'd been in with some soviet black market shit but daniel and i think it's not all super past tense bc none of his life makes sense otherwise. not even just in terms of having squirreled away money before, i mean right fucking now bc otherwise why was he stealing ~50k from my dad's mom?

...i feel like there are some new people here since i last posted about him. so yk. welcome to the party, ask away

0 notes

Text

Life in Russia: A Handbook for Foreigners

Relocating to a new nation brings both exciting and difficult circumstances. If you're an expat considering relocating to Russia, it's imperative that you have a clear understanding of what to expect. This blog offers a range of topics as a guide for tourists visiting Russia. It covers everything from the booming expat employment market to the cost of living, language, climate, and crucial data in an effort to make managing your new adventure easier for you. Read about how the top foreign moving firms in Russia can help ensure that your time there is seamless…Read More

0 notes

Text

International moving companies in Russia

When making one of the biggest decisions of your life, choosing the appropriate people to support you will be crucial to the success of your relocation. We know how challenging moving to a new country can be, so we aim to make the transition for expats to Russia as simple as possible. In order to assist a client's migration in any way possible, our teams of dedicated consultants are on the ground in Russia. We at Help Xpat are certain to fulfil your needs and exceed your expectations, whether you're a firm seeking for a mobility specialist to help HR with the onboarding process or strategic transfers of relocating workers. In addition to our specialised mobility programmes, we help expats in a number of ways, such as the planning and transportation of their international shipment and the relocation of their pets. This is what distinguishes us as one of Russia's top relocation service providers.

0 notes

Text

The Complete Guide to Social Media Marketing for Limassol Businesses

Social media presents immense potential for businesses in Limassol to engage customers, drive growth, and build their brand. But where do you start? After consulting small businesses in Limassol for over a decade, I've seen firsthand how a thoughtful social strategy tailored to this city can fuel tangible results. In this comprehensive guide, you’ll learn insider tips to succeed on every major platform and take your marketing to the next level. Let's dive in! Knowing Your Audience in Limassol Limassol has a diverse, multicultural population. Get to know your customers first before crafting any social strategy: Locals - Mostly Greek Cypriots who are proud of their city and seek tight-knit communities. - Appreciate tradition but also attracted to latest trends. - Responsive to posts highlighting local culture, food, history. Expats - Skilled professionals from Europe, Russia, Middle East drawn by job opportunities. - Seek ways to connect, network and socialize in new home. - Engage with content helpful for navigating life abroad. Tourists - Visit beaches, nightlife, historic sites like Kolossi Castle. - Looking for tips on attractions, restaurants, things to do. - Interactive platforms like Instagram or TikTok ideal to inspire. Businesses - Numerous companies in shipping, trade, real estate and more. - Interested in platforms like LinkedIn for professional networking. - Share useful industry news, tips, and local success stories. Consider your target customer's interests and behaviors. This will inform platform and content choices. Setting Your Social Media Goals Start by defining clear objectives to guide your strategy: - Increase brand awareness or sales by __% in __ months - Gain __ new followers on Instagram in __ months - Achieve __% engagement rate per post - Generate __ sales leads via social media in __ months - Grow email list by __ new subscribers in __ months Revisit these goals often to track progress using built-in analytics on each platform. Choosing the Right Social Platforms It’s unrealistic to be active across every network. Focus your time on 1-3 key platforms aligned with your goals and audience: Facebook With over 2 billion monthly users, Facebook is ideal to engage locals and the Limassol community. Profile Optimization - Professional profile & cover photo representing your brand - Compelling “about" section with description, history, contact info - Add buttons linking to your website, booking platforms, etc. - Use Shop section if selling products online Content Strategy - Share announcements, new products/services, upcoming events - Highlight special deals and offers to drive sales - Post videos showcasing your business and behind-the-scenes - Engage followers with polls, questions, user-generated content Targeting - Location targeting within Limassol region - Interest targeting based on customer preferences - Behavior targeting focused on purchase intent - Lookalike audiences modeled after current followers Advertising - Offer promotional discounts or free shipping - Encourage contest entries or giveaways - Retarget recent customers to drive repeat sales Instagram With 500 million daily active users, Instagram is perfect for visually oriented businesses to showcase products and personality. Profile Optimization - Cohesive aesthetic and vibe in profile photo and highlights - Link website and other contact info in bio - Consistent branded hashtags in captions Content Strategy - Post high-quality lifestyle images conveying your brand - User-generated content to highlight satisfied customers - Behind-the-scenes photos/videos to build rapport - Leverage trends, challenges, and hashtags Targeting - Use popular local hashtags like #limassol or #limassollife - Run influencer campaigns with local personalities - Geotarget content in Limassol area Advertising - Promote posts, unique offers or events as sponsored - Advertise in Stories with swipe up links - Partner with influencers on sponsored content LinkedIn With over one billion registered users and over 58.4 million companies, LinkedIn is ideal for B2B outreach and lead generation. Profile Optimization - Headline and about section highlighting your expertise - Experience section outlining company history and team - Media tab with related videos and content Content Strategy - Share articles and tips positioning your expertise - Post case studies demonstrating client success - Promote webinars, events, and other resources Targeting - Join active industry and local community groups - Target sponsored content by job title and company Advertising - Sponsored messaging for promotions or lead gen - Sponsored content for gated assets like whitepapers - Webinar or event promotion targeted locally Crafting Engaging Social Media Content Consistency and quality are key when creating content on social platforms. Follow these best practices: - Post Frequently: 2-3 times per week per platform minimum - Offer Variety: Mix promotional posts with other helpful info - Include Visuals: Posts with images/video drive most engagement - Inspire Sharing: Ask questions, highlight user content, run contests - Watch Trends: Jump on viral hashtags, trends, and challenges - Monitor Performance: Track engagement metrics to refine efforts Here are specific types of content that resonate in Limassol: - Local highlights: Historic sites, cuisine, culture, beaches etc. - Industry insider tips and actionable advice - Q&As and AMAs (Ask Me Anything) with customers - User reviews, testimonials, and engagement - Spotlights on influential locals and businesses - City guides for tourists and newcomers - Current news and events like festivals Mix up your content types to provide value and attract new followers. Interacting With Customers and Followers Social media is inherently social. Be sure to: - Respond thoughtfully to comments and messages - Ask questions to spark engaging conversations - Highlight user generated content like reviews and tags - Give back by liking others' content and sharing to your followers These simple efforts go a long way. In one study, 96% of consumers were more likely to do business with brands that reciprocated social interactions. Analyzing Performance and Data Consistently evaluate your efforts using built-in analytics: - Engagement metrics like reactions, comments, clicks - Audience growth across platforms and demographics - Post/account reach to gauge total exposure - Website traffic from social referrals - Conversions like sales, sign-ups, bookings Compare data to benchmarks and goals. Double down on what works and change what doesn’t. Small optimizations can lead to big lifts in results. Ranking in Social Media Search Results You can also improve visibility and search engine optimization (SEO) through social: - Include target keywords in profile bios and post text - Use relevant hashtags and tags - Share high-quality content from other sites - Post consistently to establish authority and expertise - Encourage social shares to boost inbound links - Monitor search ranking positions over time The Power of Influencer Marketing in Limassol Partnering with influencers who have strong local clout can rapidly expand your reach and credibility. First, research potential brand ambassadors on Instagram and TikTok who are based in Limassol, post frequently about the city, and have engaged followings in your target demographic. Reach out to micro-influencers with 5k-50k followers, as they often have the highest engagement rates. Offer to provide exclusive discounts, products, or experiences to the influencer and their followers in exchange for promotional posts and stories. Be clear upfront about expectations for post frequency, types of content, and messaging so both parties align. Track engagement metrics on influencer content using unique links and promo codes. Calculate the following: - Impressions and Reach: Total number of views - Engagement Rate: Likes and comments divided by reach - Conversions: Sales, sign-ups, or bookings from clicks and promo codes If results are strong, continue working with those influencers. If not, test partnerships with others who may be a better fit. Building an In-House Social Media Marketing Team For larger companies who prioritize social media, hiring a dedicated in-house team allows for greater focus and results. Each member can specialize in a particular area: - Content Creators: Generate engaging posts, captions, articles, and videos consistently - Community Managers: Respond promptly to all consumer messages and comments - Graphic Designers: Design visually appealing and cohesive graphics and ads - Advertising Specialists: Manage and optimize paid campaigns and budgets - Data Analysts: Track KPIs and identify opportunities through social analytics Create an editorial calendar for organized content creation across platforms and campaigns. Conduct regular team meetings to discuss what's working well and areas for improvement. Using project management tools like Asana can facilitate smooth collaboration. Investing in dedicated social media management software like Hootsuite or Buffer can also help maximize productivity. Advertising Tips and Best Practices Getting the most from your ad spend comes down to rigorous testing and optimization: Always A/B test multiple versions of each ad, adjusting elements like imagery, copy, captions, and calls-to-action to see what resonates best. Retarget engaged website visitors who are already familiar with your brand rather than trying to attract cold traffic. Craft tailored ads reminding them to purchase or complete sign up. Set specific budget limits per platform and campaign based on expected ROI, and monitor spend closely. Reduce or pause underperforming ads to focus budget on what works. Use website analytics integration and Facebook pixel to build custom audiences for ads based on actions site visitors have taken. Target them with relevant offers. Schedule ads strategically around times of peak engagement such as evenings or weekends, or during relevant events, launches, or holidays. Closely track conversion metrics so you can calculate ROI on ad spend and optimize accordingly. Prioritize campaigns generating sales, leads, and sign ups. Putting It All Together The opportunities to grow through social media marketing in Limassol are immense. By taking the time to learn your audience, set strategic goals, adopt suitable platforms, create engaging content, meaningfully interact with followers, analyze data, and optimize for search visibility, you will be primed for social success in this vibrant city. I hope this comprehensive guide provided helpful insights as you elevate your social presence. What are your biggest takeaways? Any other questions? Let me know in the comments! Read the full article

0 notes

Text

To expand on the latter three as I did the former two: Claire Clairmont of course was a key player on that stormy 1816 night in Lake Geneva. She was the step-sister of Mary Shelley, lived with Mary and Percy, was briefly coupled with Byron, introduced him to Mary and Percy, and had a child with him. Thus, she is not only a primary part of the Shelley-Byron circle, but its main facilitator (arguably along with Mary, who wished to meet Byron before Percy did, and Percy, whose funds sustained the three of them and made it all happen).

Claire and Byron's child Allegra died young of an illness that ravaged Europe at the time (I don't remember which one, as there were several). Claire never had children but she was a pretty proud aunt and kept correspondence, especially later in life, with her brother's family. This is where her nephew Wilhelm comes in. For more information on Claire and Wilhelm: The Clairemont Correspondence by Marion Kingston Stocking, probably the greatest Clairemont biographer (also edited Claire's journals and wrote a biography of her). Claire did a bit of creative writing too but everyone praised her more for her personality-filled letters, and she didn't want to publish anything (with the exception of a short story The Pole when desperate for money & encouraged by Mary, who may have edited or written some of it as well) because she didn't want to compete with Percy, her step-sister Mary Shelley, and Mary's celebrity author parents.

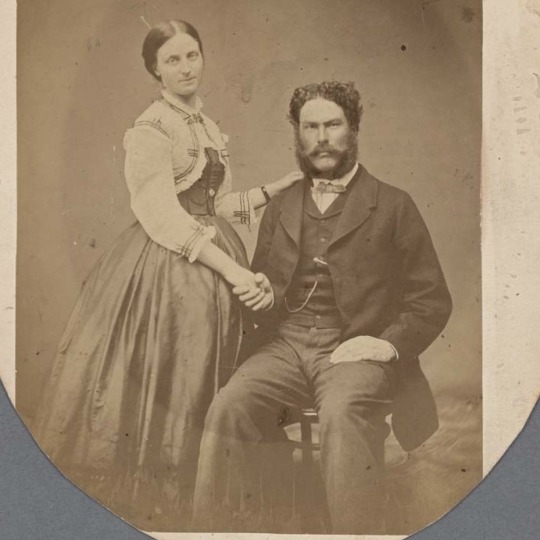

Wilhelm (1831-1895) is pictured with his wife Ottilie Clairmont (1843-1913) in 1866, making them about 35 and 23 respectively. She was Austrian, he was born and raised in Austria where Claire briefly moved after the Shelley-Byron circle totally disbanded and mostly everyone left Italy after the deaths of Percy Shelley and Edwad Ellecker Williams, which was also importantly shortly preceded by the death of one of Mary and Percy's children and the death of Claire and Byron's child, and succeeded by mutual dramas of all sorts — in short, everyone in the circle had good cause to want to leave their Italian expat community and start life afresh somewhere else after the events of 1822.

Claire briefly lived with her young nephew Wilhelm in England in 1849. He moved to Australia in 1852 and then traveled various places. Claire moved back to Italy in 1859 after also living in a million places her whole life and trying to retain her independence at all costs ever since she stopped living with Mary and Percy, first living independently in England briefly in 18 when she started her affair with Byron, then moving back in with Mary and Percy, then living independently again in Italy after she had her child with Byron and they lived with the Williams.

It was not usual for women, especially young women, to live alone, to not marry, and to earn their own livings. At first she was sustained by Percy who respected her wish for independent living and vowed to be her patron when she damaged her reputation by leaving with him and Mary at 16. Shelley left a large sum for her in his will, but unfortunately for her and everyone else in the will, the funds could not be handed out until after he postumously inherited them after the death of his father, who lived a very long time (as Claire and Mary lamented in their letters). So after Percy's death, Claire moved abroad again to Austria, Germany, and Russia, where she worked as a tutor and governess to sustain a very meagre and hard living. Her brother Charles, father of William, ran a school in Austria.

Thomas Medwin lived with Jane and Edward at one point and also lived with Mary and Percy Shelley at another time. He was a writer himself, and he wrote poems with Shelley and translated works for Byron. As I said, he was a main player in the Italian circle, and could often be seen accompanying then on their daily adventures in pistol shooting, boating, writing, riding, reading, writing, editing, drinking (with Byron), discussing love affairs (with Byron), what have you.

Thomas Medwin is sometimes considered a controversial figure in the Byron-Shelley circle because many, like Mary Shelley, found some of his biographical writings to be distasteful and/or had personal grudges against him, and like they do with Trelawny, many claim to have caught him in exaggerations and even outright lies.

Mary wrote to Mrs. Hunt of Medwin’s Byron biography: “Have you heard of Medwin’s book? Notes of conversations which he had with Lord Byron (when tipsy); every one is to be in it; every one will be angry. He wanted me to have a hand in it, but I declined. Years ago, when a man died, the worms ate him; now a new set of worms feed on the carcase of the scandal he leaves behind him, and grow fat upon the world’s love of tittle-tattle. I will not be numbered among them.”

However, Mary contributed to Thomas Moore's biography of Byron, a work which some including Lady Byron criticized for being inaccurate (source: Remarks occasioned by Mr. Moore’s Life of Lord Byron. Literary Gazette No. 687 20 March 1830) 185-86). Moore's work wasn't inaccurate, but simply biased, like all biographies are in my experience. Like with Moore and Trelawny, people exaggerate Medwin's exaggerations.

Even a lot of his critics, like Lady Caroline Lamb, still admitted that much of what he said was truly accurate. For the most part, from the research I've done, much of his biographical writing is mostly true and the "lies" are often his memory failing him, nothing malicious. If anyone is remotely interested in assessing the accuracy or inaccuracy of historical biographies & memoirs, or interested in researching Shelley/Byron/related figures, see Lovell Jr.'s editor's note from the 1966 copy of Medwin's Conversations of Byron (here). Lovell Jr. is a great Romantic scholar.

Also, his Wiki page is memeable & when taken out of context kind of makes it seem like he and Byron murdered Shelley together lmao

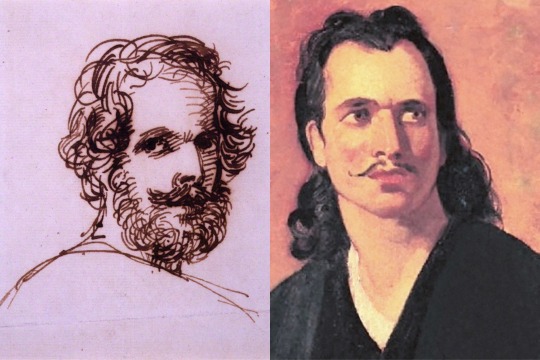

Part 3 of PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE ROMANTICS, A TUMBLR HISTORY EXHIBIT: photos i've collected of people related to the english writers of the romantic period and/or who were part of the byron-shelley circle.

Edward John Trelawny (above: a photo of him as an elder compared to a portrait of him as a young man). A key member of the circle, celebrity/adventurer/writer, friend and biographer of Byron and Shelley. Outlived everyone. Proposed to both Mary Shelley and Claire Clairmont and remained in touch with them their whole lives. Really interesting person but also a chronic liar, making it difficult to tell which parts of his life stories are fact or fiction. He is buried next to Shelley (who is buried next to Keats); Trelawny bought the cemetery plot when Shelley died decades prior and later offered it to Mary Shelley who declined it. The last two portraits below were done by Joseph Severn, the artist who was friends with Keats, did most of his portraits, & took care of him as he was dying in Rome. I don't think Trelawny ever met Keats.

Jane Williams Hogg (née Cleveland). She was married to an abusive man named John Edward Johnson who she left for Edward Ellecker Williams, who was the father of her first two children and a friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley's cousin Thomas Medwin. The family then lived in the same household with the Shelley family (Mary, Percy, and their children) in Italy. Percy dedicated some of his last poems to Jane. After Percy and Edward died together in a boating accident she lived with Mary before partnering with Shelley's best friend from college Thomas Jefferson Hogg who she had two children with.

I think the similarity between her younger portrait (1822, age 24) & her photograph (date unknown, but she died in 1884 & seems like she could be in her 80s in the photo) are very striking; you can clearly see the nose, eyes, hair, and mouth are exactly the same, only older.

She also knew George Eliot and William Michael Rossetti; I mentioned the Rossetti's in my last post. I wonder if she ever discussed Shelley's connection to John Polidori with them; I don't believe she ever met John Polidori, but maybe the Shelleys would have mentioned him to her.

Thomas Medwin, another key player of the Shelley-Byron circle in Italy. Cousin of Percy Bysshe Shelley and friend/biographer of Shelley and Byron.

Wilhelm Charles Gaulis Clairmont, the nephew of Clara Mary Jane Clairmont aka Claire Clairmont. Wilhelm was the son of her half-brother Charles Gaulis Clairmont.

#romanticism#thomas medwin#claire clairmont#the romantics#english romanticism#english romantics#romantics#romantic poets#biography#memoirs

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Posted @withregram • @amatlcomix You’ve waited long enough‼️Amatl Comix #5 Jose Alaniz’s The COMPLEAT MOSCOW CALLING is live and available via our linktree here @amatlcomix #amatlcomix The Compleat Moscow Calling José Alaniz Paperback – February 24, 2023 AMATLCOMIX 2023 “Both wonderful and wonderfully demented. Also makes me strangely nostalgic.” Gary Shteyngart, author of The Russian Debutante's Handbook and Absurdistan Now, from Amatl Comix! THE COMPLEAT MOSCOW CALLING, a lost 90s epic of expat life in Russia! Innocent abroad Pepe Pérez finds himself in a vibrant post-Soviet Moscow of colorful personalities, extreme contrasts, and a “mafiya” boss after his head. Worst of all, there's no Mexican food! José Alaniz's “Moscow Calling,” the first ongoing American comic strip in Russia, appeared in the English-language newspaper “The Moscow Tribune” not long after the wall fell. This collection gathers and concludes the strip along with additional material, including the unfinished sequel “Cassie's Turn” and the novella “Moscow 93.” Step back into a pre-Putin Russia of startling beauty and danger! Advance Notices! "The Compleat Moscow Calling makes for quite the culture shock with its tale of a Mexican-American's adventures in pre- Putin Russia. Remarkable, multilingual- a sequential arts achievement!" Hector Rodriguez, creator of El Peso Hero "Treat yourself to José Alaniz's idiosyncratic comics created in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union. With a journalist's eye and a cartoonist's wit, he spins grand tales that interweave a talking bat and a motorcycle-riding Baba Yaga amongst his many other characters. Taking inspiration from such divergent sources as Dostoevsky, The Clash and Sal Buscema, Alaniz adroitly mixes fact and fantasy to serve up an entertaining visual Molotov cocktail. Heed the call!" Javier Hernandez, creator of the El Muerto graphic novel series https://www.instagram.com/p/Cpt6qOvu4g8/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Content warning: This article contains a scene including a graphic sexual assault.

My friend sets aside his cocktail, its foamy top sprinkled with cinnamon in the shape of a hammer and sickle, to process his disbelief at what I’ve just told him. “You want to return to Russia?” he asks.

I met Enrico when I arrived in Stockholm eight months ago. He understands my situation as well as anyone. He knows that I fled Moscow three days after Russia invaded Ukraine; that my name, along with the names of other journalists who left, has fallen into the hands of pro-Kremlin activists who have compiled a public list of “traitors to the motherland”; that some of the publications where I’ve worked have been labeled “undesirable organizations”; that a summons from the military enlistment office is waiting for me at home; that since Vladimir Putin expanded the law banning “gay propaganda,” I could be fined up to $5,000 merely for going on a date. In short, Enrico knows what may await if I return: fear, violence, harm.

He wants me to explain why I would go back, but I can’t think of an answer he’d understand or accept. Plus, I’m distracted by the TV screens in the bar. They’re playing a video on loop—a crowd in January 1990 waiting to get into the first McDonald’s to open in Russia. The people are in fluffy beaver fur hats, and their voices speak a language that, for the past year, I’ve heard only inside my head. “Why am I here?” a woman in the video says in Russian. “Because we are all hungry, you could say.” As the doors to McDonald’s open and the line starts to move, I no longer hear everything Enrico is saying (“You could live with me rent-free …” “You could go to Albania. It’s cheaper than in Scandinavia ...” “We could get married so you can live and work here legally …”).

Part of me had planned this meeting in hopes that Enrico would persuade me to change my mind—and he did try. But I’ve already bought the nonrefundable plane tickets, which are saved on my phone, ready to go.

A week later, I spend a night erasing the past year from my life—a year of running through Europe as if through a maze. I clear my chats in Telegram and unsubscribe from channels that cover the war. I wipe my browser history, delete my VPN apps, remove the rainbow strap on my watch, and tear the Ukrainian flag sticker from my jacket. The next day—March 29, 2023—I fly to Tallinn, Estonia, and ride a half-empty bus through a deep forest to the Russian border. The checkpoint sits at a bridge over the Narva River, between two late-medieval castles. German shepherds keep watch, and an armed soldier patrols the river by boat.

“What were you doing in the European Union?” the Russian guard asks.

“I was on vacation,” I say.

“You were on vacation for more than a year?” she asks.

I reply that I have been very tired. She stamps my passport and the bus moves on.

What I didn’t tell the guard, and what I couldn’t tell Enrico, is that I’m tired of hiding from my country—and that I want to trade one form of hiding for another. I have conducted my adult life as if censorship and propaganda were my natural enemies, but now some broken part of me is homesick for that world. I want to be deceived, to forget that there is a war going on.

“Start from the beginning,” my mother would say when I couldn’t figure out a homework problem. “Just start all over again.”

I woke up on February 24, 2022, to a message from a friend that read: “The war has begun.” At the time, I was an editor at GQ Russia, gathering material for our next issue on Russian expats who had moved back home during the pandemic. I was also editing a YouTube series called Queerography. For a blissful moment, I took my friend’s text for a joke. Then I saw videos from Ukrainian towns under bombardment. Russian forces had encircled most of the country. My boyfriend was still asleep. I wished I could be in his place.

A few months earlier, American intelligence had informed Ukraine and other countries in Europe of a possible offensive. But Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, had responded: “This is all propaganda, fake news and fiction.” While I didn’t necessarily believe the truth of Lavrov’s words, I doubted the regime could afford to tell a lie so big. Vladimir Putin’s approval rating was near its lowest point since he gained power. On the eve of the attack on Ukraine, only 3 percent of my fellow citizens thought the war was “inevitable.”

After the invasion, I spent three days in silence. I couldn’t sleep, and I had no appetite. My hands trembled so badly that I couldn’t hold a glass of water still. When I visited friends, we’d sit in different corners of the room scrolling through the news, occasionally breaking the silence with “This is fucked up.”

In Moscow, armed police patrolled the streets to deter protesters. Soon, the press reported that a man was arrested in a shopping mall for an “unsanctioned rally” because he was wearing blue and yellow sneakers, the colors of the Ukrainian flag. News media websites were blocked in accordance with the new law on “fake news” about Ukraine. People stood in line to empty the ATMs. “War” and “peace”—two words that form the title of Russia’s most celebrated novel—were now forbidden to be pronounced in public. Instagram was filled with black squares, uncaptioned, seemingly the only form of protest that remained possible. The price of a plane ticket out of Russia soared from $100 to $3,000, in a country where the minimum wage was about $170 a month.

If I waited another day, it seemed, the Iron Curtain would descend and I would become a hostage of my own country. So on the morning of March 1, my boyfriend and I locked the door to our Moscow apartment for the last time and made for the airport. In my backpack were warm clothes, $500 in cash, and a computer. We were leaving for nowhere, not knowing which country we would wake up in the next day.

At the international airport in Yerevan, Armenia, flights arrived every hour from Russia and the United Arab Emirates, another route along which people fled. Once we were there, we boarded a minivan to Georgia, the only country in the South Caucasus with which Russia no longer maintained diplomatic ties. The van was packed with families and their pets. From one of the back seats, a girl asked her mother: “Mama, are we far away from the war now?” A night road through mountain passes and volcanic lakes took us to the border. I asked a guard there to share a mobile hot spot with me so I could get online and retrieve coronavirus test results in my email. “Of course,” he replied, “though you don’t deserve it.”

In Tbilisi, the alleys were lit up at night with blue and yellow. On the city’s main hotel hung a poster that read “Russian warship, go fuck yourself.” Fresh graffiti on walls around the city read: “Putin is a war criminal and murderer.”

At an acquaintance’s apartment, we shared a room with two other men who had fled. “The most important thing is that we’re safe,” we reassured each other if one of us began to cry. “I’m not a criminal,” said one of the guys. “Why should I have to run from my own country?” None of us had an answer.

In Russia I was now labeled a “traitor and fugitive.” The Committee for the Protection of National Interests, an organization associated with Putin’s United Russia party, had stolen a database containing the names of journalists who had left the country and distributed it on Telegram. Liberal journalists in Moscow had begun to find the words “Here lives a traitor to the Motherland” scrawled on their doors. One critic was sent a severed pig’s head.

My fellow fugitives and I started looking for somewhere more permanent to live, but most rental ads in Tbilisi stipulated “Russians not accepted.” We tried to open bank accounts, but when the bank employees saw our red passports they rejected our applications. Like so many other companies, Condé Nast—which publishes GQ and WIRED, among other magazines—pulled out of Russia. I was without a job. The YouTube show I edited closed down soon after, its founder declared a foreign agent and later added to the Register of Extremists and Terrorists. Foreign publications told me that all work with Russian journalists was temporarily suspended.

Soon signs began to appear outside bars and restaurants in Tbilisi saying that Russians were not welcome inside. I decided to sign in to Tinder to try to meet people in this new city, but most men I chatted with suggested that I go home and take Molotov cocktails to Red Square. I placed a Ukrainian flag sticker on my breast pocket and wandered the city in silence, ashamed of my language.

My boyfriend and I finally found a room in a former warehouse with no windows, the furniture covered in construction dust. The owner was an artist who was in urgent need of money. To pay the rent, I sold online all my belongings from the Moscow apartment: a vintage armchair from Czechoslovakia, an antique Moroccan rug, books dotted with notes, a record player given to me by the love of my life. Ikea had closed its stores in Russia, and customers wrote to me: “Your stuff is like a belated Christmas miracle.”

One day in mid-spring, I left the warehouse for an anti-war rally that was being held outside the Russian Federation Interests Section based in the Swiss Embassy. The motley throngs of people chanted “No to war!” In the crowd I glimpsed the familiar faces of journalists who had left Russia like me. “Why did you come here?” a stranger asked me in English. “To us, to Georgia. Do you really think your cries will change anything? You shouldn’t be protesting here. You should be outside the Kremlin.”

I wanted to tell him that I grew up in a country where a dictator came to power when I was 6 years old, a man who has his enemies killed. I wanted to say: One time, when I was an editor at Esquire, my boss denounced an author I worked with to Putin’s security service, the FSB, and the FSB sent agents to interrogate me, and when I warned the author, the FSB came for me again, threatening to arrest me and listing aloud the names of all my family members. I wanted to tell the stranger on that street in Tbilisi that I’d had to disappear for a while, and that when I felt brave enough, I had gone to protests and donated money to human rights organizations. That I had fought but, it seemed, had lost. That I just wanted to live the one life I’ve got a little bit longer. But at the time I couldn’t find the words.

A month later, the world saw images of mass graves in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, dead limbs sticking out of the sand. Outside our building one morning, on an old brick wall that was previously empty, was a fresh message, the paint still wet: “Russians, go home.” My boyfriend went back to Russia so he could obtain a European visa, promising he would be back in a month, but he never returned.

I spent the rest of the year on the move: Cyprus, Estonia, Norway, France, Austria, Hungary, Sweden. I went where I had friends. The independent Russian media that I’d always consumed went into exile too, setting up operations where they could. TV Rain began broadcasting out of Amsterdam. Meduza moved its Russian branch to Europe. The newspaper Novaya Gazeta, cofounded by the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Dmitry Muratov, reopened in Latvia. Farida Rustamova, a former BBC Russia correspondent, fled and launched a Substack called Faridaily, where she began publishing information from Kremlin insiders. Journalists working for the independent news website Important Stories, which published names and photos of Russian soldiers involved in the murder of civilians in a Ukrainian village, went to Czechia. These, along with 247,000 other websites, were blocked at the behest of the Prosecutor General’s Office but remained accessible in Russia through VPNs.

“During the first days of the war, everything was in a fog,” says Ilya Krasilshchik, the former publisher of Meduza, who went on to found Help Desk, which combines news media and a help hotline for those impacted by war. “We felt it our duty to inform people of what the Russian army was doing in Ukraine, to document the hell that despair and powerlessness leave in their wake. But we also wanted to empathize with all of the people caught up in this meat grinder.” Taisiya Bekbulatova, a former special correspondent for Meduza and the founder of the news outlet Holod, tells me, “In nature you find parasites that can force their host to act in the parasite’s own interest, and propaganda, I believe, works in much the same way. That’s why we felt it was our duty to provide people with more information.”

I wanted to continue my work in journalism, but the publications that had fled Russia weren’t hiring. My application for a Latvian humanitarian visa as an independent journalist was rejected, and I didn’t have the means to pay the fees for US or UK talent visas.

The panic attacks began in the fall, during my first stay in Stockholm. Red spots, first appearing around my groin, started to take over my body, creeping up to my throat. I’d get sick, recover, and then wake up with a sore throat. In October, I learned that my boyfriend had married someone else. The next day, my mother called to tell me that a summons from the military enlistment office had arrived.

I was in Cyprus when, at 3 am one February morning, I woke to the sound of walls cracking and the metal legs of my bed knocking on marble. Fruit fell to the floor and turned to mush. The tremors of a magnitude-7.8 earthquake in Gaziantep, Turkey, had passed through the Mediterranean Sea and reached the island. I didn’t scramble out of bed. I hoped instead that I would be buried under the rubble—a choice made for me by fate. Later that month, my friends in Stockholm insisted that I come stay with them again. I wandered the streets on a clear winter day, buying up expired food in the stores. The blue and yellow flags of Sweden shone bright in the sun, but I saw in them the flag of another country. Back in the apartment, I slept all the time, and when I did wake I lulled myself with Valium. One day I felt the urge to swallow the whole bottle.

Frightened by my own thoughts, I felt how much I wanted to be back in Russia. In my mother country, all the tools of propaganda would keep painful truths at bay. “The news in Russia is only ever good news,” Zhanna Agalakova, a former anchor on state TV’s main news show, later told me. Agalakova quit after the invasion began and returned the awards she had received to Putin. “Even if people understand that they’re being brainwashed, in the end they give up, and propaganda calms them down. Because they simply have nowhere to run.”

Masha Borzunova, a journalist who fled Russia and runs her own YouTube channel, walked me through a typical day of Russian TV: “A person wakes up to a news broadcast that shows how the Russian military is making gains. Then Anti-Fake begins, where the presenters dismantle the fake news of Western propaganda and propagate their own fake news. Then there’s the talk show Time Will Tell that runs for four, sometimes five hours, where we’ll see Russian soldiers bravely advancing. Then comes Male and Female—before the war it was a program about social issues, and now they discuss things like how to divide the state compensation for funeral expenses between the mother of a dead soldier and his father who left the family several years ago. Then more news and a few more talk shows, in which a KGB combat psychic predicts Russia’s future and what will happen on the front. This is followed by the game show Field of Miracles, with prizes from the United Russia party or the Wagner Private Military Company. And then, of course, the evening news.”

I had gone from being infuriated by this kind of hypnosis to envying it. The free flow of information had become for me what a jug of water is to a severely dehydrated person: The right amount can save you, but too much can kill.

“Welcome to Russia,” the bus driver said as we crossed the border from Estonia. I was nearly home. There was no particular reason for me to return to Moscow, so I made for St. Petersburg, where some friends had an apartment that was empty. I used to look after it before the war, coming over to unwind and water the flowers. It was a place of peace.

All my friends had left Russia too, so I was the first person to set foot in the apartment in a year. Black specks covered every surface-—midges that had flown in before the war and died. I scrubbed the place through the first night, starting to cry like a child when I came across ordinary objects I remembered from peacetime: shower gel, a blender, a rabbit mask made out of cardboard. Over the next few weeks, I tried to return to the past as I remembered it. I went to the bakery in the morning. I exercised, read, wrote. At first glance, the city seemed unchanged. There were the same boatloads of tourists on the canals, tour groups on Palace Square, overcrowded bars in Dumskaya Street. But more and more, St. Petersburg began to feel to me like the backdrop of a period film: impeccably executed, the gap between the past and the present visible only in the details.

One day I heard loud noises outside my window, as if all the TVs in town had suddenly started emitting the sound of static. The next day the headline read: “Terrorist Suspected of Bombing St. Petersburg Café Detained and Giving Testimony.” The café had hosted an event honoring the pro-war military blogger Vladlen Tatarsky, and a bust of his likeness had blown up, killing him and injuring more than 30 people. But life went on as if nothing had happened. St. Petersburg was plastered with posters for an upcoming concert by Shaman, a singer who had become popular since the invasion thanks to his song “I’m Russian.” (He would later release “My Fight,” a song that seemingly alludes to Hitler’s Mein Kampf.) In a candy store I noticed a chocolate truffle with a portrait of Putin on the wrapper. “It’s filled with rum,” the clerk said.

Sometimes in checkout lines at the supermarket I glimpsed mercenaries in balaclavas, newly returned from or preparing to go to the front. On the escalator down to the subway, where classical music usually floated from the speakers, Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto was interrupted by an announcement: “Attention! Male citizens, we invite you to sign a contract with the military!” In the train car, I saw a poster that read: “Serving Russia is a real job! Sign a military service contract and get a salary starting at 204,000 rubles per month”—about $2,000. One afternoon, as I stood on the platform next to a train bound for a city near the Georgian border, I overheard two men talking:

“I earned 50,000 in a month.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No, bro. But I won’t go back to Ukraine again. It’s fucking terrifying.”

This was a rare admission. The horror of the war’s casualties—zinc coffins, once prosperous cities turned to ruins—were otherwise hidden behind the celebrations for City Day, the opening of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, and marathons held on downtown streets.

After a week or so in Russia, feeling very alone, I went on Tinder. One evening I invited a man I hadn’t met over to the apartment. I placed two cups of tea on a table, but when the man arrived he didn’t touch his. He threw me to the floor, unbuttoned his pants, and inserted his dry penis inside me. “I know you want it,” he whispered, covering my mouth. “I can tell from your asshole.”

I bit him and squirmed, trying to get him off me. After he left, my legs kicked frantically and I couldn’t breathe. I knew that the police wouldn’t help me. I contacted Tinder to tell them that I had been raped and sent them a screenshot of the man’s profile, but no one answered. That evening I bought a ticket for a night train to Moscow. More than ever, I wanted to see my mother.

“You must have frozen over there,” My mother said as she met me at the door to her apartment outside Moscow. Putin had said that, without Russian-supplied gas, “Europeans are stocking up on firewood for the winter like it’s the Middle Ages.” People were supposedly cutting down trees in parks for fuel and burning antique furniture. Some of the only warm places in European cities were so-called Russian houses, government-funded cultural exchanges where people could go escape the cold as part of a “From Russia with Warmth” campaign. When I told my mother that Sweden recycles waste and uses it to heat houses, she grimaced in disgust.

Thirteen months earlier, when I had left the country, my mother called to ask me why. I told her that I didn’t want to be sent to fight, that I couldn’t work in Russia anymore. “You’re panicking for no reason,” she said. “Why would the army need you? We’ll take Kyiv in a few days.” After the horrors in Bucha, I had sent her an interview with a Russian soldier who admitted to killing defenseless people. “It’s fake,” she responded. “Son, turn on the TV for once. Don’t you see that all those bodies are moving?” She was referring to optical distortions in a certain video, which Russian propagandists used to their advantage.

After that, we had agreed not to discuss my decision or views so that we could remain a family. Instead, we talked about my sister’s upcoming wedding, my aunt’s promotion at a Chinese cosmetics company whose products were replacing the brands that had quit the country. My uncle, a mechanic, had finally found a job that would get him out of debt—repairing military equipment in Russian-occupied territories. My mother was planning to take advantage of falling real estate prices to buy land and build a house. In their reality, the war was not a tragedy but an elevator.

I had arrived on Easter Sunday, and the whole family gathered at my mother’s house for the celebration. My aunt told me she was worried that I might be forced to change my gender in the West; she had heard that the Canadian government was paying people $75,000 to undergo gender-affirming surgery and hormonal therapy. My stepfather was interested in the availability of meat in Swedish stores. Someone asked whether it was dangerous to speak Russian abroad, whether Ukrainians had assaulted me. I kept quiet about the fact that the only person who had attacked me since the invasion was a Russian man, that the real threat was much closer than my family thought. The TVs in each of the three rooms of the apartment were all switched on: They played a church service, then a film called Century of the USSR. There were news broadcasts every two hours and the program Moscow. The Kremlin. Putin—a kind of reality show about the president.

“Do you know what this is?” my mother said as she placed a dusty bottle of wine without any labels in the middle of the festive table. “Your uncle gave it to us,” my stepfather chimed in. “He brought it from Ukraine.” A trophy from a bombed-out Ukrainian mansion near Melitopol, stolen by my uncle while Russian soldiers helped themselves to electronics and jewelry. “Let’s drink to God,” said my stepfather, raising his glass. “You can’t raise a glass to God,” my mother answered. “That’s not done.” “Let’s drink to our big family,” he said. The clinking of crystal filled the room; to my ears it sounded like cicadas.

Suddenly I felt sick and locked myself in the bathroom. I tried to vomit, but my stomach was empty, bringing up only a retch. “What’s wrong?” my mother asked, standing outside the door. “Drink some water, rest, sleep.” I tried to lie down. My skin began to itch. My friend Ilya Kolmanovsky, a science journalist, once told me: “Did you know that a person cannot tickle himself? Likewise you cannot deceive a mind that already knows the truth.” Self-deception is dangerous, he said: “Just as your immune system can attack your own body, your mind can also engage in destroying you day by day.”

That evening I left my mother’s apartment for St. Petersburg and made an appointment with a psychiatrist. I told the doctor that I felt like the past had been lost and I couldn’t find a place for myself in the present. She asked when my problems began. “During the war,” I answered, careful to keep my face expressionless. The psychiatrist noted my response in the medical history. “You’re not the only one,” she said. She diagnosed me with prolonged depression and severe anxiety and prescribed tranquilizers, an antipsychotic, and an anti-depressant. “There are problems with drugs from the West,” she said. Better to take the Russian-made ones. If the Western pills were like Fiat cars, then these would be the Russian analog, Zhigulis: “Both will bring you closer to calm, but the quality of the trip will differ.”

Though the drugs seemed to help, I began to realize over the next several weeks that no amount of pills could change this fact: The home I was looking for in Russia existed only in my memories. In June, I decided to emigrate once again. At the border in Ivangorod, spikes of barbed wire pierced the azure sky and smoke from burning fuel oil rose from the chimneys of the customs building. This time, as I left, I felt that I had no reason to return. My home was nowhere, but I would continue searching for one.

With financial help from a friend, I moved to Paris and signed a contract with a book agent. I made an effort not to read the news. Still, from time to time, I came across stories about Putin’s increasing popularity at home, how foreign nationals could obtain Russian citizenship for fighting in Ukraine, how the regime passed a law that would allow it to confiscate property from people who spread “falsehoods about the Russian army.” One day, when air defense systems shot down a combat drone less than 8 miles from my mother’s home, she called me and asked: “Why did you leave? Who else will protect me when the war comes to us? Who if not my son?” I didn’t have an answer. “I love you, Mama”—that was the only truth I could tell her.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four years in Russia!

Four years in Russia!

To be honest, each year gets more surreal thinking I’ve survived for one more of Earth’s trips around the sun in everybody’s favorite capital, Moscow. Despite saying this every time, I still cannot believe that things have, on the whole, gone pretty well. This anniversary happens to coincide with the 871st birthday of the city I’ve since called home, which is a happy coincidence; the fireworks…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Truth hurts

More than a month after the start of the war between Russia and Ukraine, my own reaction has shifted through a wide range of emotions: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance and, finally, analysis. Through all of that came the realisation that, unlike many Russian expats such as myself, a vast majority of people inside Russia do not want to know the truth about the war. This was the hardest fact to accept – and even harder to explain. But here goes.

A friend of mine, a young woman in St Petersburg, absolutely refuses to acknowledge both the tragic events taking place on the frontline and those around her in everyday life. For her, like millions of others, it has become a matter of mental self-preservation to believe that closed shops will reopen soon, the shelves will somehow be quickly restocked and everything will get back to normal in no time. It would be an oversimplification to say that she is a victim of state propaganda. Rather, she is a living example of what it’s like to exist in a post-truth society. She declares that everyone around her is lying or being paid to lie and that it is impossible to trust anyone except her immediate circle of friends and family.

For such people in Russia, moral considerations are immaterial; they’re only interested in keeping themselves ensconced in a comfortable bubble by negating reality. State propagandists know and use this to their advantage. The state TV channels work to create fantastic stories about nationalists and fascists in Ukraine, about Pentagon-run biolaboratories directed against ethnic Russians. The purpose of these fantasies is to create a distorted sense of togetherness, of being besieged by an external, hostile world. The question is whether anything can burst through this bubble as the war continues. That could lead to civil outrage and collapse of the present regime – but only if Russians are willing to accept reality.

Alexander Zhuravlyov is a Russian-born journalist who spent 30 years working for the BBC Russian Service in London.

from The Monocle Minute - Newsletter

43 notes

·

View notes