#essay commentary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

i really liked "unwilling hole" gin-san in the ouroboros essay, do you have any other thoughts about it/what a willing hole would be?

thank you! this is a great question.

"reluctant hole" is a term taken from tshirt's scatological gintama essay, eat shit and die. gintoki's status as a reluctant hole in this original context is quite literal. tshirt talks about how the Central Joke in gintama is the inversion of power in the desiring-pair, and how gintama's dirty jokes get imbued with meaning due to the conflation and elision between sex and shit, both being "dirty things"--with the anal naturally becoming the potent symbol of this. the key point made by tshirt that i take up in my ouroboros essay is "gintama, of course, is about preferring dirty things."

in my ouroboros framework, the Hole looms like an antagonist of sorts. but as i specify in my second essay (the one published in yaoizine vol2), the problem with the "hole-sided" gintama villains isn't that they have a hole in them (everyone has a hole. it comes free), but in their response to it. the problem with gintama's villains isn't that their holes are somehow worse than the heroes', but that their hole lacks "dirt." because the shame of being alive, the pain of their human relationships, and the misery of their failures are too much for them to bear.

what i meant by gintoki as a reluctant hole isn't exactly the same thing that tshirt meant, but in the end it's relatively similar. tshirt used the "sword stuck in ass" arc as an example of the sort of punchline that gintama is obsessed with, the way it draws humour from playing with the pole-hole/sword-scabbard binary. yes, he's quite literally a reluctant hole in that arc, but tshirt is talking about the underlying ideas that gintama uses to structures its jokes and its portrayal of a hero who's meant to be incredibly cool, but very carefully designed to be lame and have the opposite qualities of a traditional protagonist.

this "inversion" in his characteristics isn't unique or anything, it's part of a very common type of power fantasy in shounen, and you can also see it in surface-level imagination exercises on tumblr. but either way, it's projected into the gags that gintoki interacts with, and because gintama is obsessed with toilet humour, that means another "binary" ripe for flipping is the pole/hole. quoting tshirt quoting sougo in that arc: “He really is a fucked up samurai. Instead of using the sword to protect his own body, he’s using himself as a scabbard for his friggin’ sword.”

similarly, in my framework, the (deceptive) binary that looms large is the head/tail--which i've mapped the hole/phallus onto as well. i'm not going to go into detail about what my framework is actually about because i assume you've read all that already. but essentially gintoki is a "reluctant hole" not only because he's struggling to not be hole-sided, but because he's also struggling with not being hole-sided. he struggles to fill his hole with the things it needs to be filled with: he struggles to learn how to live, and then he struggles with living. he's reluctant because he never wanted to be the main character, subject to the kind of indignities, tragedies, and ironies expressed through both gintama's gags and serious writing--always oriented towards him being that kind of "anti-hero", and thus inextricably tying him to dirt.

so i think in the end, there really is no such thing as a "willing hole" without changing the meaning of the words used. because it would be easy to describe an antagonist with no more regrets as a willing hole, but would that antagonist be interesting in a gintama context? or you could use it to describe someone who doesn't struggle with what gintoki struggles with--but then they would just be an inhumanly perfect being without struggle, and that wouldn't be interesting either. so in the end, it's a little bit misleading, because there is no real dichotomy here. there are only reluctant holes in the sense that i used it in my essay--and gintoki is the microcosm of the entire series, so he's The reluctant hole, and in describing him this way i was just really describing what gintama is about.

i think the closest thing to an interesting and valuable "willing hole" in gintama is actually shouyou, owing to his dead anime mentor status. he isn't a flawless being, but he knew he would die to utsuro one day, and he embraced it. but this response has already gone on long enough. i hope it satisfies your curiosity!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revolutionary Girl Utena: Gender in Context

beneath the cut, I discuss the RGU's portrayal of gender in the context of 1990s Japan.

in Ikuhara's interview with Mari Kotani, he stated that in traditional Japanese society, "prince" meant "patriarch." the same is true in Western societies--there was a time when a prince would be an heir to a royal line. by 1997, this meaning had died out of large parts of the world. even the association between princes and traditional masculinity was fading. Saionji, the weakest, most pathetic man in the show, is a parody of historical Japanese masculinity, with his kendo and his blatantly regressive beliefs about women.

in RGU, prince may still mean patriarch, but in a far more subtle fashion. Ikuhara and Kotani discussed the changing expectations for men in the latter half of the 20th century--it became gauche to fight over a woman with one's brawn, so instead, power struggles were played out in the arena of looks and sex appeal. one can see this reflected in the character Akio, whose power as a prince arises from his ability to turn "easy sensual pleasure based on dependency" "into a selling point with which to control people."

Akio has his moments of showboating masculinity, but when preying on Utena, he operates by making himself seem non-threatening and soft.

not only that, but he purports to want to allow students to express their individuality and thus approves of Utena's masculine form of dress. this is a front--by the end of the show, he's telling Utena that girls shouldn't wield swords. thus, through Akio's character, the show argues that traditionalist patriarchy in Japan isn't gone, but instead has only been papered over with false progressivism.

with all that said, there seems to be more to the character. he's taken the family name of his fiance, Kanae, and whatever material power he has in the school is dependent upon her family. in Japanese society, this is considered a humiliating position to be in, something that only a shameless man would do. the show never gives the audience any insight into how Akio feels about this--is he unbothered entirely, or are his actions against the Ohtori family an expression of his repressed anger? does he harm the children under his care to compensate for his humiliation?

this aspect of Akio's character may seem irrelevant in light of the larger, immaterial social forces at work in the show. however, I would argue that it was included for a reason. Akio, despite his status as ultimate patriarch of Ohtori, is in fact a highly emasculated character, to the point where lead writer Enokido even said that he is driven by an infantile mother complex.

to explain why Akio was portrayed this way, we have to discuss Japanese history. the nation suffered a major defeat in WWII and was forced to accept whatever terms the United States laid out for it. for an examination of how the Japanese have never truly processed those events and have plunged into modernity with reckless abandon, I recommend Satoshi Kon's Paranoia Agent. to sum it up briefly, in a very short period, the nation regained its economic footing, and by the 1980s had the largest gross national product in the world. this economic boom may have allowed Japan to maintain a sense of sovereignty, dignity, and power, but it was inherently fragile.

the infamous "bubble economy" lasted from 1986 to 1991. during this time, anything seemed possible; financial struggles appeared to be a thing of the past, and capitalist excess reached new heights. the ghosts of this period can be felt across Japanese media; for instance, think of the final shot of Grave of the Fireflies (1998), where the two dead children look down on Kobe, glowing an eerie green to imply its impermanence. the abandoned theme park from Spirited Away (2001) is explicitly referred to as a leftover from the previous century, when many attractions were built and then tossed aside in a few short years.

the bubble popped in 1992, leaving an entire generation feeling cheated. the bright futures they'd been promised, which had actually materialized for their parents and older siblings, had been lost to them overnight. economic crises are often accompanied by gender panics. to quote from Masculinities in Japan, "The recession brought with itself worsening employment conditions, undermining the system of lifelong employment and men’s status of breadwinners in general. The unemployment rate was rising, and although it never reached crisis levels, men could no longer feel safe in their salaryman status. Their situation was further complicated by the rising number of (married) women entering the workforce."

with this in mind, Akio's character can be taken as a representation of masculinity in crisis in 90s Japan. he's forced to rely on women for his position in life and has failed to save his only relative, Anthy. he tries to escape his misery through hedonism, perhaps an allegorical representation of how men tried to maintain their old standard of living after the economic bubble burst.

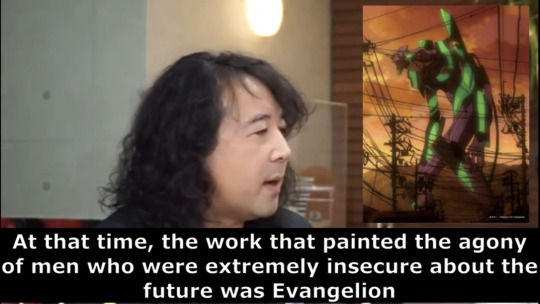

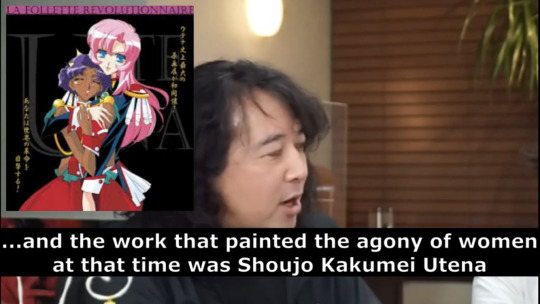

but of course, Akio is not the main character of RGU--the story is about girls. mangaka Yamada Reiji discussed the series in the context of the 90s, stating the following:

while I opened this essay by discussing the prince, the same points could be made about the princess. despite the increasing irrelevance of royalty, princess is still an important concept. how does it relate to the socioeconomic landscape of the 90s?

in Yamada's view, RGU is full of relics of the 80s; for instance, the figure of the ojou-sama, an entitled young woman who never lifts a finger for herself. during the economic bubble, it was increasingly common for women to be entirely taken care of by the men in their lives. Yamada names Nanami as a clear ojou-sama type character: she weaponizes her femininity, demanding to be rescued, doted on, and served.

however, by 1997, the ojou-sama could no longer expect to get what she wanted. from the 80s to the 90s, the percentage of women in the workforce increased around 15%; it was no longer viable for most women to be "kept" by their families. as the men experienced the humiliation of not being able to provide for their wives and children, women were undergoing a disillusionment of their own.

Yamada blames Disney for creating the ideological structure which led women astray. obviously, the company is known for its films about princes rescuing princesses. in Yamada's recounting, during the 80s, the company was infiltrating Japan through its theme parks as well; across the country, Disneylands were opening up, and people were buying into the escapism the corporation offered. Japan, as America, became a country of eternal children. its people were waiting for a prince to appear and save them.

but fairy tales can't stave off reality forever. Yamada claims that RGU embodies the rage of young women who woke up one day and realized that they had been raised on a lie. this anger pervades the work from beginning to end.

though RGU was created in a particular social context, its lessons can be extrapolated to any time and place. as the first ending tells us:

I hope this essay helped provide more context for the series. thanks for reading!

#rgu#commentary#revolutionary girl utena#this was originally a part of another essay but i revamped it and added a lot more detail

905 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I could be totally wrong but, I believe it was sort of expected that men/gentlemen lose their virginity before marriage in regency times. But I also there’s some fandom ‘debate’ about whether or not Mr Darcy would’ve had sex before getting married. So I was just curious about what your canon for Mr Darcy in T3W is. Is he a virgin or not?

I knew someone would ask me this eventually, haha. I've actually had really long conversations with my beta reader about this trying to figure it out. It sounds like this might all be stuff that you’ve already seen discussed in the fandom, but I’ve never thought about it deeply before and so these are new thoughts to me.

I keep going over the historical real-world likelihood, the authorial intent, and the text itself but I’m still not 100%. I’ll explain my thinking and what I find most likely, but here’s your warning that it’s not a clear cut yes/no.

Because on one hand, at that time period it was most common for men in his position to have seen sex workers or have casual encounters/mistresses with women from their estates. Though I do absolutely believe not all men did that, no matter how much wealth and power they had. To go back some centuries, William the Conqueror seemed to be famously celibate (no hints of male lovers either according to the biography I read) until his marriage, and there's no evidence of affairs after it either. The best guesses as to why are that it was due to his religious devotion and the problems that had arisen from himself being a bastard and not wanting to recreate that situation. Concerns over religion and illegitimate children would certainly still have been applicable in the regency to men who thought that way. And in modern times I've seen sex workers say that when an 18/21yo is booked in by his family/friends to 'become a man' often they end up just talking and agree to lie about the encounter. After all, it’s not like every man wants casual sex, even if they aren’t demisexual or something in that vein. But, statistically speaking, the precedent of regency gentlemen would make Darcy not a virgin.

On the other hand, just how aware was Jane Austen, the very religious daughter of a country rector, of the commonness of this? There’s a huge difference between knowing affairs and sex workers existed (and no one who had seen a Georgian newspaper could be blind to this) and realising that the majority of wealthy men saw sex workers at some point even if they condemned the more public and profligate affairs. The literature for young ladies at the time paints extramarital sex - including the lust of men outside of marriage - as pretty universally bad and dangerous. This message is seen from 'Pamela' and other gothic fiction to non-fiction conduct books which Jane Austen would have encountered. Here's something I found in 'Letters to a Young Lady' by the reverend John Bennett which I found particularly interesting as it's in direct conversation with other opinions of the era:

"A reformed rake makes the best husband." Does he? It would be very extraordinary, if he should. Besides, are you very certain, that you have power to reform him? It is a matter, that requires some deliberation. This reformation, if it is to be accomplished, must take place before marriage. Then if ever, is the period of your power. But how will you be assured that he is reformed? If he appears so, is he not insidiously concealing his vices, to gain your affections? And when he knows, they are secured, may he not, gradually, throw off the mask, and be dissipated, as before? Profligacy of this kind is seldom eradicated. It resembles some cutaneous disorders, which appear to be healed, and yet are, continually, making themselves visible by fresh eruptions. A man, who has carried on a criminal intercourse with immoral women is not to be trusted, His opinion of all females is an insult to their delicacy. His attachment is to sex alone, under particular modifications.

The definition of a rake is more than a man who has seen a sex worker once, it's about appearance and general conduct too, but again, would that distinction be made to young ladies? Because they seem to simply be continuously taught 'lust when unmarried is bad and beware men who you know engage in extramarital sex.' As a side note, Jane Austen certainly knew at least something about the mechanics of sex: her letters and literature she read alludes to it, and she grew up around farm animals in the countryside which is an education in itself.

We can also see from this exert that the school of thought seems to be 'reformed rake' vs 'never a rake' in contention for the title of best husband, there's no debate over whether a current rake is unsuitable for a young lady. And, from Willoughby to Wickham to Crawford, I think we have a very clear idea of Jane Austen's ideas of how likely it is notably promiscuous men can reform. This does not preclude the possibility that her disparaging commentary around their lust is based more on over-indulgence or the class of women they seduce, but it's undoubtedly a condemnation of such men directly in line with the first part of what John Bennett says so it's no stretch to believe she saw merit in the follow-on conclusions of the second part as well. Whether she would view it with enough merit to consider celibacy the only respectable option for unmarried men is a bit unclearer.

I did consider that perhaps Jane Austen consciously treated this as a grey area where she couldn’t possibly know what young men did (the same reasoning is why we never see the men in the dining room after the ladies retire, etc) and so didn't hold an opinion on men's extramarital encounters with sex workers/lower-class women at all, but I think there actually are enough hints in her works that this isn’t the case. Though, unsurprisingly, given the delicacy of the subject, there’s no direct mention of sex workers or gentlemen having casual lovers from among the lower-classes in her texts.

That also prevents us from definitively knowing whether she thought extramarital sex was so common, and as unremarkable, as most gentlemen treated it. But we do see from her commentary around the consequences of Maria Bertram and Henry Crawford's elopement that she had criticism of the double standards men and women were held to when violating sexual virtue. Another indication that she perhaps expected good men to be capable of waiting until marriage in the way that she very clearly believed women should. At the very least, a man who often indulges in extramarital sex does not seem to be one who would be considered highly by Jane Austen.

She makes a point of saying, in regards to not liking his wife, that Mr Bennet “was not of a disposition to seek comfort for the disappointment which his own imprudence had brought on, in any of those pleasures which too often console the unfortunate for their folly or their vice.” This must include affairs, though cheating on a wife cannot be a 1:1 equivalent of single young men sleeping around before marriage. However, the latter is generally critically accepted to be one of the flaws that Darcy lays at Wickham’s door along with gambling when talking about their youth and his “vicious propensities" and "want of principle." Though this could be argued that it’s more the extent or publicity of it (but remembering that it couldn't be anything uncommon enough that it couldn't be hidden from Darcy Sr. or explained away) rather than the act itself, or maybe seductions instead of paying women offering those services. I also believe Persuasion mentioning Sunday travelling as proof of thoughtless/immoral activity supports the idea that Jane Austen might have been religious enough that she would never create a hero who had extramarital sex.

So, taken all together this would make Darcy potentially a virgin, or, since I couldn't find absolute evidence of her opinions, leave enough room that he isn’t but extramarital sex isn’t a regular (or perhaps recent) thing and he would never have had anything so established as a mistress.

I’ve also been wondering, if Darcy isn’t a virgin, who would he have slept with? I’ve been musing on arguments for and against each option for weeks at this point. No romantasy has ever made me think about a fictional man's sexual habits so much as the question of Darcy's sexual history. What is my life.

Sex workers are an obvious answer, and the visits wouldn’t have raised any eyebrows. Discretion was part of their job, it was a clean transaction with no further responsibilities towards them, and effective (and reusable, ew) condoms existed at this time so there was little risk of children and no ability to exactly determine the paternity even if there was an accident. It was a fairly ‘responsible’ choice if one wanted no strings attached. In opposition to this, syphilis was rampant at the time, and had been known to spread sexually for centuries. Sex workers were at greater risk of it than anyone else and so the more sensible and risk-averse someone is (and I think Mr Darcy would be careful) the less likely they would be to visit sex workers. Contracting something that was known as potentially deadly and capable of making a future wife infertile if it spread to her could make any intelligent and cautious man think twice.

Servants and tenants of the estate are another simple and common answer. Less risk of stds, it can be based on actual attraction more than money (though money might still change hands), and is a bit more intimate. But Wickham’s called wicked for something very similar, when he dallies (whether he only got to serious flirting, kissing, or sleeping with them I don’t think we can conclusively say) with the common women of Meryton: “his intrigues, all honoured with the title of seduction, had been extended into every tradesman's family.” And it isn't as though Wickham had any personal duty towards those people beyond the claims of basic dignity. Darcy, who is shown to have such respect and understanding for his responsibilities towards the people of his estate and duties of a landlord, would keenly feel if any of his actions were leading his servants/tenants astray and down immoral paths. Servants, especially, were considered directly under the protection of the family whose house they worked in. I think it's undoubtable that Mrs Reynolds (whose was responsible for the wellbeing - both physically and spiritually - of the female servants) would not think so well of Mr Darcy if he had experimented with maids in his youth. It would reflect badly on her if a family entrusted their daughter to her care and she 'lost her virtue' under her watch. Daughters/widows of others living on the estate not under the roof of Pemberley House are a little more likely, but still, if he did have an affair with any of them I can only think it possible when he was much younger and did not feel his duties quite so strongly. Of course lots of real men didn't care about any of this, but Darcy is so far from being depicted as careless about his duties that the narrative makes a point of how exceptional his quality of care was. Frankly, it's undeniable that none of Jane Austen's heroes were flippant about their responsibilities towards those under their protection. I cannot serious entertain an interpretation that makes Darcy not, at his current age, at least, cognizant of the contemporary problems inherent in sleeping with servants or others on his estate.

A servant in a friend’s house would remove some of that personal responsibility, but transfer it to instead be leading his friend’s servants astray and in a manner which he is less able to know about if a child did result. That latter remains a problem even if we move the setting to his college, so not particularly likely for his character as we know it… though it wouldn’t be unusual for someone to be more unthinking and reckless in their teenage years than they are at twenty-eight so I don’t think having sex then can be ruled out. Kissing I can much more easily believe, especially when at Oxford or Cambridge, but every scenario of sleeping with a lower-class woman has some compelling arguments against it especially the closer we get to the time of the novel.

Men did of course also have affairs with women of ranks similar to their own, though given Jane Austen’s well-known feelings towards men who ‘ruined’ the virtue of young ladies we can safely say that Darcy never slept with an unwed middle- or upper-class woman. Any decent man would have married them out of duty if it got so far; but if he was the sort to let it get so far, I think it impossible Jane Austen would consider him respectable. Widows are a possibility, but again, the respectable thing to do would be to marry them. Perhaps a poorer merchant’s widow would be low enough that marriage is off the table but high enough that the ‘leading astray’ aspect loses its master-servant responsibilities (though the male-female ‘protect the gentler sex’ aspect remains) but his social circle didn’t facilitate meeting many ladies like that. Plus, an affair with a woman in society would remove many layers of privacy and anonymity that sex-workers and lower-class lovers provided by simply being unremarkable to the world at large. It carries a far greater risk of scandal and a heavier sense of immorality in the terms of respecting a woman’s purity which classism prevented from applying so heavily to lower-class women.

I think it’s important to note here that something that removes the need to think about duties of landlords towards the lower-classes or gentlemen towards gentlewomen is having affairs with other men of a similar rank. But, aside from the risk of scandal and what could be called the irresponsibility of engaging in illegal acts, it’s almost certain that Jane Austen would never have supported this. For a devout author in this era the way I’m calculating likelihoods makes it not even a possibility. But if you want to write a different fanfiction (and perhaps something like a break-up could explain why Darcy doesn’t seem to have any closer friend than someone whom he must have only met two or so years ago despite being in society for years before that) it does have that advantage over affairs with women of equal- and lower-classes. I support alternate interpretations entirely – it just isn’t how I’m deciding things in this instance.

I keep coming back to the conclusion that, at the very least, Darcy hasn’t had sex recently and it was never a common occurrence. It wouldn’t surprise me if Jane Austen felt he hadn’t done it ever. Kissing, as we can see from all the parlour games at the time, wasn’t viewed as harshly, so I think he’s likely made out with someone before. But in almost every situation it does seem that the responsible and religious thing to do (which Jane Austen values so highly) is for it to never have progressed to sex. I also don’t think it conflicts with his canon characterisation to say that he wouldn’t regard sexual experience as a crucial element of his life thus far, and his personality isn’t driven to pursue pleasure for himself, so it’s entirely possible that he would never go out of his way to seek it. So, I’m inclined to think that the authorial and textual evidence is in favour of Darcy being a virgin even if the real-world contemporary standard is the opposite. (Though both leave enough room for exceptions that I’m not going to argue with anyone who feels differently; and even if you agree with all my points, you might simply weight authorial intent/textual evidence/contemporary likelihoods differently than I do and come to a different conclusion).

Remember that even if Darcy is a virgin this wouldn’t necessarily equate to lack of knowledge, only experience. There were plenty of books and artwork focused on sex, and Darcy, studious man that he is, would no doubt pay attention to what knowledge his friends/male relatives shared. Though some of it (Looking especially at you, 'Fanny Hill, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure') should NEVER be an example of appropriate practice for taking a woman's virginity. Darcy would almost certainly have been taught directly or learnt through exposure to other men talking to make sex good for a woman – it was a commonly held misconception (since Elizabethan England, I believe) that women had to orgasm to conceive. It would be in his interests as an empathetic husband, and head of a family, to know how to please his wife.

Basically, I’m convinced Darcy isn’t very experienced, if at all, and will be learning with Elizabeth. But he does have a lot of theoretical knowledge which he’s paid careful attention to and is eager to apply.

#sorry for how my writing jumps around from quoting sources to vaguely asserting things from the books I only write proper essays when forced#if anyone has evidence that Austen thought a sexually experienced husband was better/men needed sex/it's a crucial education for men/etc#PLEASE send it my way I'm so curious about this topic now#this is by no means an 'I trawled through every piece of evidence' post just stuff I know from studying the era and Austen and her work#so more info/evidence is always appreciated#I had sort of assumed the answer was 'not a virgin' when I first considered this months ago btw but the more I thought about it#the less I was able to find out when/where/who he would've slept with without running into some authorial/textual complication#so suddenly 'maybe a virgin' becomes increasingly likely#But the same logic would surely apply to ALL Austen's heroes... and Knightley is 38 which feels unrealistic#(though Emma doesn't have as much commentary on sex and was written when Austen was older so maybe she wasn't so idealistic about men then)#but authors do write unrealistic elements and it's entirely possible that *this* was something Austen thought a perfect guy would(n't) do#and if you've read my finances breakdowns you know I follow the text and authorial voice over real-world logic because it IS still fiction#no matter how deftly Austen set it in the real world and made realistic characters#pride and prejudice#jane austen#fitzwilliam darcy#mr darcy#discourse#austen opinions#mine#asks#fic:t3w#I'm going to need a tag for 'beneath the surface' but 'bts' is already a pretty popular abbreviation haha#just 'fic: beneath' maybe?? idk

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listen, I will headcanon a happily ever after for Brasso (did Cassian really have the time and presence of mind in that moment to be sure he was dead?) to be living his best life out there with all the other au resurrected sw beloveds, but I think it's actually incredibly important to recognize that, narratively, Brasso is the antithesis of Luthen. Luthen looks at all his soldiers and cannot see the person -in fact, adamantly refuses to see the individual- so no one is safe from being his pawn and he makes sure they all know it. And Luthen is Axis, with everything depending on his ability to keep existing. In contrast, Brasso always sees the person while seeming at times to have no direct functional reason for being. He cares for his best friend explicitly and without question, and even comes up with better and more complete cover stories than Cassian can manage. Brasso treats Bee with more empathy than I have ever seen any character in sw give a droid, showing him a deep level of tenderness in actions that distinctly bestow personhood on the littlest Andor. Brasso takes in Bix like a daughter, comforting her through her nightmares and trauma. Brasso goes after Wilmon with very little hope that they will make it but without hesitation to try. Brasso uses some of his precious last words to help an "unimportant" character escape punishment while sealing his own fate. Where Luthen is ruthless in the name of the cause and always the cause, Brasso is only a part of the rebellion to be with and to protect his friends. But a galaxy that has need of a man like Luthen has no room for a man like Brasso. In this essay I will

#pls do not talk to me about anything past like the first 5 episodes of s2 i have *not* finished#the essay is the running emotional commentary in my head#ragamusings#andor#andor s2#andor spoilers#andor s2 spoilers#andor season 2 spoilers#sw brasso#brasso#andor season 2

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

PIG AND DUCK MANIFESTO #1: Intro to the Classics, Bob Clampett

WELCOME TO MY LATEST OUT OF CONTROL PROJECT! read this ask for context! this is going to be a very long post--one of many--and i want people to read it, so let's just dive right in.

The Classics

THE CLASSICS ARE WHERE IT’S AT. nothing will ever top them in my opinion. you’re getting the characters and their intentions straight from the source. these characters were made up of the life experiences and sense of humor and and contexts of their creators and directors, and everything that has come after that has just been a game of telephone… and not always a very good one. i’m a purist for the classics, i know and don’t even care how snobby that may make me sound. there’s nothing better than seeing these characters in their proper context. they are products of their time, and not even in the typically negative connotation that seems to come with (but it can certainly apply… sigh). i always have and always will be unflinching of this opinion.

but that’s the exciting part: they vary from short to short. with TDTEBU being your gateway, i’m going to lay some things out just as security because I LOVE GETTING TO EDUCATE NEW PEOPLE AHHHHH!! so i’m sorry if this is stuff you already know, but you can never be too careful (and i can never be too eager to play teacher AHHH I’M SO EXCITED.) BUT.

Porky and Daffy are unique in that they’re some of the only characters who receive the benefit of being passed from director to director. most of the time, a director who debuts a certain character will be the only director who works with that character. Yosemite Sam was Friz Freleng’s creation (and modeled after himself!), and there are only two or so shorts that feature the character that weren’t by him… and one of those was directed by an animator in his unit. same deal with Bob McKimson and Foghorn Leghorn–Foghorn’s a McKimson exclusive. same with Chuck Jones and Marvin the Martian. by the time of the ‘50s or so, everyone kinda kept their own characters to themselves. the mix and match nature of the ‘30s and ‘40s was no longer really present

Porky, Daffy and Bugs are happy exceptions to this rule. it’s amusing, too, in that Porky and Daffy have both sort of been “abandoned” by their “fathers”--Tex Avery, who made Daffy, only directed three shorts with him. Friz Freleng directed a considerable amount of Porky shorts, but the last time he touched him was in 1952–Porky’s last short in the golden age was released in 1965 (1966 if you wanna count reused footage). likewise, Porky and Daffy have long been established as a pair essentially since their conception (which’d be 1937; Porky’s Duck Hunt, the first Daffy cartoon made, was obviously the first to have the star together, and they were recurringly established as sidekicks as early as 1938). they often travel together! so, because their dynamic was so set in stone, this meant that many different directors got to lend a hand in showing us how they portray Porky and Daffy. some directors portray them as best buddies, whereas others portray them as mortal enemies. sometimes they’re like a vaudeville act, with Porky playing Daffy’s second banana. sometimes they’re buddies who wanna kill each other! there are so many unique flavors and variations of their dynamic, and that’s also why i’m so huge on them: through them, we get to see the individual identities of the DIRECTORS, how THEIR individual voices compare… and considering my favorite thing about the franchise is its history and the people behind it, well, i love it HAHA.

SO LET’S EXPLORE THOSE DYNAMICS! let’s put some relationships to some names.

Bob Clampett

Bob Clampett is my greatest artistic inspiration of all time, so this PROOOOBABLY isn’t a surprise to most of my followers HAHA. he’s always been my favorite director–i find our sensibilities are very similar, his shorts elicit these visceral and emotional reactions out of me like nobody else, and i love his stuff. i very much gravitate to his portrayal of the characters.

it’s almost unfair to nominate him as #1, because he has the benefit of having so much history with the characters. i mean, ALL of these guys do! but he was really the first to consistently pair them together and establish them as a dynamic duo. much of the understanding of Daffy and Porky as characters, together or separate, were helmed under his direction in the late ‘30s. it’s genuinely very sweet getting to watch them “grow up”--in any sense, but, again, this was largely felt under his shorts.

i love both the early and later Clampett pig ‘n duck joints for different reasons. the early stuff, i love because there’s such a fondness and innocence about them! which seems REALLY funny to say, because some of the shorts i have in mind when referring to this are about “Daffy tries to cut a very conscious and unwilling Porky in half with a handsaw to prove that he’s a reliable surgeon” or “Daffy gets so drunk that Porky has to save his kid in part due to Daffy’s negligence”.

but there’s such a sweetness about these early shorts. i always point to the opening of Porky & Daffy as an example; Daffy is still at an incredibly early stage of his lifespan and is still rather incoherent. at this stage, he’s moreso a bundle of nerve endings and noises–very out of his gourd and juvenile. but whereas most modern interpretations have Porky being annoyed by this, he’s ENDEARED by this! he radiates this fondness for Daffy and it’s the sweetest thing ever. you get the sense that he just sees him as his silly little friend who can do no wrong–aw, shucks, sure he’s a bit out there, but isn’t everyone? (mentally ill duck breaking things in the background) < i stole a friend’s wording on this because it’s just stuck with me for years at how correct and true it is.

and it’s funny, Porky’s a bit of an enabler even in these shorts!! in Porky & Daffy, he’s Daffy’s manager and signs him up for a boxing fight in hopes to get some prize money. he enables a lot of his esoteric behavior, and it actually leads them to victory–i love it because it’s very cute in a funny way, it’s nice that we get to see Daffy and his daffiness celebrated rather than shamed. it reflects an innocence on both characters that’s very fitting for the time and i just… i love it! in a world of shorts that are most well known for their adversity and cynicism, there’s something so special about seeing these two goofballs join up and enjoy each others’ company, even if it’s for the use of the very warped context that they may be put into. i still like thinking that Porky was the one who decided to stuff Daffy full of bags of flour to make it seem like he’s more muscular than he really is, sort of hinting at this bit of doubt towards Daffy’s capabilities (that isn’t entirely unwarranted) and it’s just such a funny little commentary, y’know?

the opening of Wise Quacks also really scratches this itch of demonstrating a similar fondness. as alluded to earlier, Porky actually refers to Daffy as his childhood friend (“why, we were kids together–!”) in this ADOOOOORABLEEEEEEE monologue that i think about all the time. again, there’s just this… innocence feels wrong, but it is kind of innocent! compared to how their dynamic would get later on! warmth, maybe? there’s a clear kinship between the two characters, and this is unique WHOLLY to them in how genuine that kinship feels. you have characters like the Goofy Gophers or Ralph and Sam who are friends (more, in the case of the gophers lol)... but that’s the whole joke of their existence. the whole joke is that they’re buds in a world surrounded by murderous, cynical cretins who want to kill each other. which Porky and Daffy can sometimes fall into as well, though this is largely on Porky’s side…

GETTING AHEAD OF MYSELF. anyway, i love the earnest of the early Clampett pig and duck shorts because no other character dynamic or even characters, period, have that benefit. it offers a very unique glimpse to these characters that gives them some versatility and room to work with. and i just really love how they play off of each other! i like that Porky is probably way more fond of this clearly unstable and not all there duck than he probably should be. and in these shorts (Porky’s Last Stand specifically), you get the feeling that he doesn’t really fully… understand him? and he doesn’t try to? because he just assumes him to be this silly little guy. AND, again, like in the case of P.L.S., that ends up having dire consequences (Daffy tries to warn him against a raging bull approaching him, but Porky is still stuck in “this is my silly friend who is crazy and can’t think for himself so he’s probably just up to his tricks. he’s silly” mode, is COMPLETELY oblivious to Daffy’s frantic gesticulating and pointing, and just assumes that there’s a salesman at the door. as if this is how Daffy would react to a salesman).

this sense of innocent condescension on Porky’s part is still even present in some of the more “transitional” Clampett pig and duck shorts, like the end of A Coy Decoy–this is a short that debuts a bit of a more fleshed out Daffy. trying not to go into the entire history of the characters here–i’m sure i’ll fail–but he’s become quite a bit more lucid at this point; still hasn’t really entirely hit “puberty” yet, but he’s close to it, he can show a wider breadth of emotions and this short rides out on a lot of what P.L.S. establishes, but was limited by Daffy still being a bit more incapacitated by his neuroses. so, basically, it’s PORKY who’s in the wrong and has underestimated him! Porky basically says to his face that he’s an idiot for falling in love with a duck decoy and that he’s wasting his time. and then we see that Daffy has gotten busy in his spare time and proven Porky wrong. i love when Porky has a bit of an innocent ego like this–it’s Porky’s world and we’re all living in it, his obliviousness can often result in some unintentional condescension and i LOVE this about Clampett’s pig, and it’s just so funny to watch paired up against Daffy. especially in these moments where, for a change, he’s actually in the right! you get the sense that Porky is still stuck in the days where he’s Daffy’s boxing manager and having to sneak his robe full of flour bags to make him seem stronger, and not in the current where we now grapple with the horrifying possibility that DAFFY is the one making the most logical sense! horrid!

i’m about to move onto the later Bob Clampett pig and duck shorts (not very many 😢) but going back to my previous points about the fondness and innocence of it all… i mean just c’mon. this is cute. what other LT characters have this benefit. AT ANY POINT IN THE FRANCHISE! played completely straight too!!

WELL… it is LT, and LT is bent on cynicism and violence, and these guys certainly have it. the arrival of the war prompts these shorts to become a lot more brash and raucous, as these cartoons reflect so much about their current eras. and, with it, the characters adapt! everyone is made a bit more abrasive, bold, perhaps mean and fierce. the innocence of the ‘30s is pretty far gone… but not completely. and that’s again why i love Clampett’s pig and duck so much. they have balance.

and that’s why Baby Bottleneck is my all time favorite pig and duck short. directed by–you know who–Bob Clampett!

it’s the perfect short to me for their characterization because it has both sides of what i want from them. it has them working as an established duo, it still has those little subtle, funny themes of condescension from Porky in the tasks he assigns Daffy and way he regards him, and, most importantly, it has them trying to kill each other.

it’s just such a great escalation and sampling of everything you could want from them. i love that they’re working together as a partnership, i love the history that it implies. there’s also a great subtle commentary of Porky giving the unceremonious task of answering all of the phones for their bottlenecked delivery service–i can just so imagine him thinking “well, Daffy never shuts the hell up, so he’ll be perfect for the job of answering all these phones while i go do my quiet, secluded job elsewhere. this’ll keep him occupied”. like having the talkative never-shuts-up guy in charge of answering all these lines.. it’s so funny at how backhanded it is!!

or Porky’s reasoning that ends up being the catalyst for the short’s conflict: there’s an unhatched egg that needs to be hatched so they know who to send the unclaimed egg to, as they run a baby delivery service. Porky’s thinking is simple: Daffy = duck. Duck = hatch eggs. Daffy = hatch egg.

and he just asks him to do this so courteously, he’s so confident in thinking that Daffy will OF COURSE hatch out the egg because he’s a duck!!! it’s just simple facts and logic! not at all processing how unintentionally patronizing and even offensive that can come off, like “hey you’re a duck, you’ll hatch this out without objection. do this for me, egg-hatcher” LMFAO.

and, of course, Daffy takes GREAT offense to this (despite agreeing to it at first), and Porky gets. So. Pissed. no escalation, one shot he’s smiling, seems to vacantly register Daffy’s refusal, and in the next shot he grabs him by the neck and yells at him to sit on the egg. and when he won’t he just immediately starts shoving him. no tact of any kind from either party.

AND I LOVE IT! because these guys are immature pissbabies. said lovingly. at their best they are immature pissbabies. or maybe not. i like when they’re immature pissbabies. and it’s especially made funny because we’ve seen how smiley and happy they were to work together JUST MOMENTS BEFORE. Porky is batting his eyelashes at Daffy and Daffy’s all quick and subservient, appearing at a moment’s notice… and all of the sudden they’re literally wrestling over this stupid egg. at one point Porky grabs Daffy’s hand and tries to force it on the egg–what kind of warmth is a hand gonna give the egg??? it’s not about the hatching of the egg at all, but getting to prove Daffy “wrong”, winning this pissing contest by showing “haha you touched the egg, now you have to sit on it, nyeh nyeh”

and you may be thinking, Eliza. i think you’re going a little far with this. Porky is a sweet and kind little gentleman. maybe a bit esoteric perhaps, but surely he’s not that petty, right?

WRONG! the first short they directed together, What Price Porky, literally has Porky sticking his tongue out at Daffy and going “NYEHHH” in the most wonderfully juvenile way after he “beat” him (got him to stop leading a ducktatorship–sorry–against his hens and stealing their corn). and so Porky’s behavior here is just such a wonderful little callback to that. it’s the last short Clampett directed with them, but a lot of the back and forth fighting and pettiness parallels the first short he directed with them, and there’s just something about that that gets to me!!

and the best part of Bottleneck is that THERE IS NO WINNER. they’re both petty little idiots who brought this upon themselves, and that’s represented by having them get lodged into their own deathtrap inventions and smushed into this awful, horrifying, disgusting and wonderful pigduck baby hybrid that a mama gorilla immediately adopts without question. at least until we get a Classic Clampett “Innuendo” (in quotes because his sophomoric sense of humor is not subtle at all. i would say 60% of his shorts AT THE ABSOLUTE MINIMUM have some sort of dick joke in them, this being one of them) where the mama thinks Porky is Daffy’s talking genitalia and freaks the hell out. understandably so. they both are at a tie and doomed to live this horrible pigduck baby life for the end of time… or at least until the iris closes out. and i just love how balanced that is. we’ve gotten so many shades of their dynamic, packed in 7 minutes of mayhem, and it’s just. AUGH. a little taste of all their different shades and capabilities. also, i should mention that TDTEBU references this short very heavily–everything with the factory is a reference to this short! so, all the more fuel to the fire!

i also feel it necessary to reference The Great Piggy Bank Robbery–the source of my username! and online alias! and icon! and also my favorite cartoon of all time! it’s a Daffy short, but Porky makes a brief cameo in it as an inconspicuously disguised trolley driver and just. HOW I LOVE THAT.

the context for the short is that Daffy accidentally knocks himself unconscious, thusly dreaming about being Duck Twacy–”the famous duck-tec-a-tive!”. and Porky showing up, i’ve always thought was so cute–like a friend of yours showing up in a dream! it implies a history with them! it’s a testament to their dynamic that they’re good enough buds for Porky to show up in his dreams. i just love how casual and real that feels, very observational and gives their dynamic and history a nice bit of depth to it.

considering it’s the last time Clampett would work with either character, it feels like a very fitting send-off to all the years of service he put into working these characters from the ground up. i really think he was hugely influential to the trajectory of their dynamic. all of the directors were–it’s a collaborative effort! but Clampett definitely worked with them very frequently at some of their most amoebic(?), doing a lot to establish their dynamic. Tex Avery was the first to pin them together, but Clampett was the first to establish it as a running dynamic.

and that’s why his interpretation is my all-time favorite. i borrow my interpretation and understanding of these guys from ALL the directors, as we will see in coming posts, but his hits a lot of what i want out of these characters. i wish he did direct more shorts of them paired together in the ‘40s, as i’d love to see what he would have done with a more mature and perhaps explosive Porky and Daffy (a la their dynamic in Baby Bottleneck, though they’re kinda anything but mature in that, aren’t they…?). but he is largely responsible for the friendship angle and giving them an exceptionally unique dynamic that no other LT character can live up to, full stop. there’s a lot to treasure about the way he portrays them. and that’s why i’m so adamant about advertising his earlier shorts, as his black and white cartoons seem to get slept on compared to his later works… they’re so charming and formative! you can feel the history! and most importantly, you can just… feel the fondness. fondness for these characters, their dynamic, these cartoons.

and fondness is important. i’ll probably get into this more in another post (likely the LTC or TLTS post), but a lot of modern adaptations miss that Daffy has a genuine fondness for Porky. even when Porky is shoving a gun in his face and saying he’s gonna blow his head off (real quote! real happening!), there’s this sort of infatuation from Daffy with his persistence in following Porky around–even if it’s just to heckle him for his own satisfaction. if he was that disinterested, if he really hated or was annoyed by him like so many modern adaptations can have a tendency to show, then he just wouldn’t stick around and be as persistent as he is! he could just amuse himself elsewhere! because that’s all he does–tend to his impulses! but i think there’s a real sort of infatuation–even if it doesn’t manifest in him being super smiley or happy all the time about it–he has with Porky, and this is often very misunderstood or overlooked and breaks my heart. “Daffy hates Porky like he hates Bugs” should be on Mythbusters, because not once in the originals is this ever true. i can say that with my full chest.

and yknow? typing this, i’m realizing Clampett never did a “Daffy heckles Porky” short, maybe beyond What Price Porky. there’s The Daffy Doc, where he tries to perform non consensual surgery on him, but there’s no malicious in his intentions. he’s just batshit insane. he thinks he’s doing a good thing and is following a very warped, but nonetheless present logic. he’s not trying to hurt Porky, but thinks he’s doing him a favor. i LOVE the shorts where Daffy heckles Porky. this is why Bob McKimson is right behind. but i love that, even if Porky doesn’t understand or may very fleetingly get annoyed with Daffy in these shorts, Clampett is maybe the only director (next to Frank Tashlin, who only directed one–but a holy grail of a short, which i’ll mention later–short with them together) who doesn’t have Daffy heckling Porky. there’s a real unity with their dynamic and, well, partnership, that’s unique to Clampett’s direction. i genuinely find that touching and perhaps a little necessary.

WHEW! AND THIS IS JUST PART 1. thank you for making it this far! i’ll be ending off each post with a list of recommendations: shorts (or episodes, for modern stuff) from each director/show that i think would be good homework viewing to get an understanding of how they’re portrayed. i’ll also be linking my in-depth analyses to each short that i’ve written one for, so if you want to learn more and dive even deeper, you can.

BOB CLAMPETT PIG 'N DUCK SHORTS YOU SHOULD WATCH (links included):

Baby Bottleneck

Porky & Daffy (CLICK HERE to read my breakdown!)

The Daffy Doc (CLICK HERE to read my breakdown!)

Wise Quacks (CLICK HERE to read my breakdown!)

Porky’s Last Stand (CLICK HERE to read my breakdown!) < this is one of my favorite reviews i've ever done, so... worth a read!

Tick Tock Tuckered (so this is actually a remake of Porky's Badtime Story, the first Clampett short he directed--this isn't one of my go-to's since Daffy's role was originally for another character, all hail Gabby Goat, but it's a rare '40s Clampett color cartoon pig 'n duck joint and i think is still nicely indicative of their dynamic. it's not one i watch often, but first timers will likely appreciate it! i've grown to take it for granted, admittedly...)

and if you still want more.. these aren't great, like, at all, but i did some commentaries on the fly of Baby Bottleneck and Porky's Last Stand back in March 2022. i highly recommend reading the review for Last Stand since there's SOOOO MUCH i packed in there that i couldn't in this, but since i haven't been able to do a formal writeup of my favorite pig 'n duck short of all time, hopefully this is a good little substitute.

ideally, my answer is ALL OF THEM, but that seems like a cheat. there's only one Clampett pig 'n duck short i'm iffy on, Scalp Trouble--can probably assume from the title it's troublesome, but, also, Porky and Daffy are incontestably the best part of the short. the gif of Porky holding Daffy comes from that short. i'll also drop a link to my analysis so you can read and enjoy the good pig 'n duck bits and ignore everything else. but they really are all worth watching!

#i'm not proud of those commentaries at all and there's a reason why i type my posts rather than do video essays or commentaries but i do#like how i can literally hear myself smiling talking about some of these things because of how much i love it LOL#WHAT THE FUCK IT'S MIDNIGHT#IVE BEEN WRITING THIS SINCE 6PM.#Pig and Duck Manifesto#looney tunes#porky pig#daffy duck#bob clampett#i absolutely am tagging this please read it lMFAO#clampett

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

Erin! Do you have rednote? Everyone has been moving there from tiktok and I was wondering if you plan to as well?

tbh i really haven't posted anything on tiktok in a few months and i want to give it a while before i try to find another platform. i'm cool chilling here with all of you, and maybe making a youtube instead of another tiktok version

#not against red note i think it's funny everyone was like “fucking bet”#and the people who were already on there seem very sweet#but i'm not in a hurry and will let y'all know what my next move is in a little bit#if i do make a youtube i have a couple ideas about things i want to post#such as animatic wips or drawing while ranting about smth#or video essays/commentary#maybe clips of me and my friends being silly#and ofc talking about writing!#i wanna make some educational videos too

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matt Smith would make a terrific and terrifying Master.

#and you know it#he'd be a great master#he's not my favourite doctor#but it's not that i don't like him#i'm just a little scared of him#sometimes#but him as master....? oh~#(he'd just need to be a little bit of a loser and not just scary/unstable)#(a bit like a doctor tbh)#eh... how those two are similar to each other#it's material for 3 long essays at least#well anyways i'm back with dw posting#and there will be more of it#soon#(you haven't followed me in vain)#i will try to tell you a bit about oncoming 20th anniversary of nuwho fanzine#and i'm still to watch christmas special soo there will possibly be a commentary on that too#keep looking#it's nice to be back with my own posts#doctor who#dw#11th doctor#eleventh doctor#matt smith#the master#the doctor#and we've seen that one interview#he'd be dangerous#hell yeah#back with tags 10x longer than the actual post

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

#one day want to make a50000 hr long youtube commentary essay about this game but i want to play it myself :-( i have the installer#but im guessing unlike worlds.com the servers are long dead#the palace#obscure games#MMO#dead metaverse#y2k#うp#cd rip

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

making a youtube video about ‘hey melissa’ and this was my outfit :3 fetch my piano wire <3

#hey melissa#starkid#nightmare time#hatchetfield universe#melissa hatchetfield#paul matthews#commentary youtuber#this is just a shameless plug for my new yt video btw#video essay#makeup#twee

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

ROBIN HOBB’S REALM OF THE ELDERLINGS >> The Tawny Man Trilogy Excerpts from Book One: Fool's Errand [Golden Fool + Fool's Fate Sets - to be updated once I post them <3]

#roteedit#bookedit#fantasyedit#tawnymanedit#realm of the elderlings#rote#tawny man trilogy#fool's errand#fitzchivalry farseer#the fool#nighteyes#robin hobb#flashing tw#made by carolyn#here to scratch the itch for adaptations of this series because we won't ever get one which is a GOOD THING <3#really was planning on keeping this to ten gifs but i can't bring myself to delete any of these#like i could give essay length commentary on each one of these but I WILL REFRAIN#and golden fool and fool's fate sets are both currently wips no clue when they'll be ready to post though <3

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

when we talk about head and holes, another example we can unify them with is trepanation. what would that reading of gintama look like?

funnily enough, i don't think trepanation works for gintama. the head and hole aren't really supposed to be unified in that way. the one area where i think the two can meet is the neck where the flesh was severed. this is reinforced by the fact that in japanese, you say "neck" in a lot of instances where you're talking about the (severed) head. the act of decapitation in a way isolates and preserves the head as its own entity. you can't really do much to a head once it's been severed in gintama, as all the energy (including symbolic energy) is produced/released in the actual act of decapitation.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

why are you against ai writing when you make bots? /gen

trying to publicly masquerade ai as writing is disingenuous and cheapening and only broadcasts that you have pisspoor confidence in your own creativity and writing abilities. it lacks integrity and is actively harmful to people who actually sit down and write rather than type a prompt into a generator that regurgitates slop, and try to pass it off as their own. people who use ai as a crutch don’t see it for what it really is; a self-imposed handicap.

chatbotting to real writing is like what porn is to real sex. jacking it to a computer screen vs real intimacy with a real human being. it's a mindless self-indulgence and entirely private between the user and ai. it is a personal vice, and personal vices are almost impossible to police. it is also, like porn, addictive and ultimately more harmful to the user itself. i'd argue people who publish ai writing as their own should just use chatbots to their heart's desire rather than make their own laziness or inability to string a sentence together everyone else's problem .

ai writing is ultimately pointless—because the imitation won’t ever come close to the real thing; the inherent beauty of writing comes from the fact it is written by someone, it is deliberate and intentional and human, from the crafting of plot and imbuing of symbolism and meaning and even down to the slightest, seemingly innocuous word choice. it’s simply not possible for ai to ever mimic that, because ai is not human. writing is innately human, because it has soul, and soul is the one thing that cannot be imitated.

#when people brag they use chatgpt to write essays.. like oh god why did you tell me? now i know you're an inconsolably dumb fuck#excuse the scathing commentary but there is most definitely a difference#private/public endangerment#ai

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

the leading male characters of RGU have variations on the same complex: "I failed at being a prince." however, they have their own specific versions of it, which manifest in widely different behaviors. I'll run through them, basing my account of the characters on how they were at the start of the show:

Saionji is deeply troubled by Utena's despair, but then witnesses her miraculous transformation. since Touga seems to be more mature than himself, he assumes Touga must be responsible for it. Saionji begins to feel himself a child, lacking in insight; not only was he unable to save the girl in the coffin, but he couldn't even understand her plight. having caught glimpse of a world he can't enter himself, he develops an inferiority complex, which he attempts to compensate for with old-fashioned masculinity, violence, and domination of others.

Miki gets sick, and his weakness forces Kozue to go to the concert hall alone. while she learns from this experience that she requires Miki in order to shine, he comes to the conclusion that he has committed a grave sin and destroyed the sunlight garden with his own hands. this irrational belief follows him into early adolescence, and he has somehow managed to turn it around and allot blame to Kozue as well. perhaps this is because siblings do not have strong ego boundaries, or maybe it's that Miki sees Kozue's failure to be a princess as an affront to his desire to be a prince. this becomes a vicious cycle, since negative attention is good enough for Kozue, who flaunts her naughty behavior to keep Miki fixated on her.

Touga is a two-faced character who outwardly projects the version of himself that he'd like to be. in actuality, though he may not be aware of it, he is a person who wishes the world was a better, fairer place and longs to alleviate suffering. however, he learned his own weakness young; to avoid the terror of powerlessness, he is willing to do just about anything. as Saionji believes Touga saved Utena, Touga believes Akio saved Utena, and so he models himself on him. on one level, he maintains a cynical worldview in which he is justified on acting however he pleases because he has gained power, but on another (deeply buried) level, he hopes he will become a prince and set things right. unfortunately for him, his behavior is contradictory with that goal and will only serve to enforce the status quo. he copes with this using cynicism, pretending to himself that he doesn't believe in nobility anyway.

Akio is like a monstrous combination of the previous three, with one crucial difference: Akio no longer actually wishes to be a prince. he may mourn his failure, but that's a form of narcissism; he doesn't even have the commitment to despair. rather, his "sadness" is a grand show in which he is the leading character. does he have a lingering spark of care for Anthy? perhaps, but he only calls it forth for the purposes of manipulation. long ago, his weakness caused Anthy immense suffering, suffering which has never ceased since. as eternity stretched on, Akio began to think to himself, "isn't this actually her fault? she's the reason I'm no longer a prince; she stole my beloved self from me. and what's more, she isn't a princess, which means she deserves this. in fact, doesn't she actually want this? yes, it's true: both of us love the way things are, and so she will always help me to keep them this way. why, I'm so magnanimous that I'll forgive her for starting this, even though it's so hard for me to bear living in my fallen state." thus, to Akio, being a failure of a prince is a sublime torture, and the scab he's grown over his original wound has calcified, not healing but rotting what's underneath.

the question now is where does Utena fit into this schema? I don't think she's in line with the characters listed above, since she's not living her life based on a failure, but instead on determination to suceed. in that way, I think she's most similar to Ruka, at least in outlook. Ruka tries to be a prince through manipulation and coercion, which is of course doomed to failure, but he is staking his life on his desire to be a prince. Utena, after overcoming her own hurdles, does the same.

#i could have described Mikage too bc i think he has a prince complex at least in part#but his deal is a bit different and also it wouldnt have added much (read my Mikage essay for full description of his issues)#rgu#commentary#idk if other ppl see Touga as i describe him but thats how he is to me

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hannah Montana’s Guide to Life Under Capitalism

Haven’t posted in a while but made a new video :)

#queer#youtube#video essay#hannah montana#miley cyrus#lgbt#gay#commentary#sociology#critical theory#Judith butler#gender#trans#transgender

314 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frozen 2: Actions Speak Louder Than Words: Why Elsa’s Apology is Enough

Introduction

Apologies come in many forms, but are words stronger than actions?

Psychological studies suggest that actions can sometimes be a more powerful way to express remorse than simply saying, “I’m sorry.” Research published in the Journal of Business Ethics (Tomlinson and Lewicki) found that while verbal apologies are helpful, demonstrating remorse through actions—such as making amends or changing behavior—can have a stronger impact on rebuilding trust.

Similarly, Lewicki, Polin, and Lount’s study on effective apologies emphasizes that the most meaningful apologies go beyond words and involve restitution. Risen and Gilovich further support this idea, showing that people tend to judge apologies more by the person's actions than by their words alone. If someone takes meaningful action to show regret, their apology is often perceived as more sincere.

This idea is especially relevant when analyzing media and storytelling, where characters may not always say the words "I was wrong," but instead demonstrate their remorse through their actions. One particularly divisive example of this can be found in Frozen 2. One of the most debated moments in the film revolves around Elsa’s decision to send Anna away—an act that many saw as cruel, especially because Elsa never explicitly apologizes for it.

Many fans wanted her to say the words "I'm sorry," but in doing so, they may have overlooked how her actions later in the film serve as her true apology. In the boat scene, Elsa heavily implies that Anna cannot help because she lacks magic, suggesting—whether intentionally or not—that Anna is too weak to be of use.

However, when Elsa reunites with Anna at the end of the film, she directly acknowledges the opposite: Anna is the one who saved everyone, including her. This shift in perspective is Elsa’s apology—she doesn’t just say she was wrong; she demonstrates it by recognizing Anna’s strength and giving her the credit she deserves.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve revisited this infamous boat scene, whether through analysis or casual discussions. But with Frozen 2 approaching its six-year anniversary this November, I wanted to take one final deep dive into the topic. My argument is simple: while Elsa never says the words “I’m sorry,” her actions speak just as loudly—if not louder—than an apology ever could.

More under the cut.

Part 1: Codependency

To fully understand why Elsa's actions serve as an apology, we need to examine the deeper issue that causes the boat scene to play out in this way in the first place: the codependent bond between Anna and Elsa. Their relationship is built on emotional reliance, and the boat scene is the breaking point where that dynamic is forced to change.

A very polarizing topic in Frozen 2 is the codependency between Anna and Elsa. Many fans resist viewing their relationship through this lens, as it challenges the idealized sisterly bond presented in the first film. However, acknowledging their emotional dependence does not mean their relationship is bad or unhealthy—it simply means they both have areas of personal growth to work on.

Throughout the film, we see how Anna and Elsa rely on each other in deeply emotional ways. Anna’s sense of purpose is tied to keeping Elsa safe and preserving the happy ending she fought for in the first movie. Meanwhile, Elsa leans on Anna for emotional validation, struggling with self-doubt and guilt that she cannot face alone. At the start of the film, Elsa expresses this openly when she tells Anna, “What would I do without you?” While this line may seem affectionate on the surface, it reveals how much Elsa depends on Anna to provide emotional reassurance and stability.

This dynamic is further emphasized during the boat scene. When Elsa discovers that their parents died trying to find answers about her powers, she is consumed by guilt. She turns to Anna, who, despite her own grief, takes on the role of emotional caretaker, lifting Elsa out of her self-blame. This moment highlights a key aspect of their relationship: whenever Elsa feels lost or uncertain, Anna is there to pull her back up.

The creators of Frozen 2 have acknowledged this theme. Kristen Bell, who voices Anna, revealed in an interview that the writers even consulted a psychologist to explore Anna and Elsa’s relationship. Bell noted, “I want Anna to deal with her codependency because she lives for everyone else, and I often do that.” (Bell). This intentional storytelling choice frames Anna’s emotional arc—particularly her song “The Next Right Thing”—as a journey toward independence. For the first time, she is forced to navigate life without Elsa at the center of her world.

By the end of the film, both sisters undergo significant growth. Anna learns that her identity cannot be solely defined by her love for Elsa, while Elsa realizes that she must stand on her own without constantly seeking Anna’s reassurance. This resolution does not diminish their love for each other—it strengthens it, allowing them to build a healthier bond based on mutual support rather than dependence.

The reason this discussion of codependency is so important in relation to the boat scene is that this emotional entanglement is what leads to the argument between Anna and Elsa in the first place. Throughout the film, Elsa struggles with an unresolved sense of purpose—Anna’s validation, which once reassured her, is no longer enough. This reflects a larger truth: relying solely on external validation is unsustainable. Eventually, a person must confront the deeper issue at its core. For Elsa, that issue is not knowing whether her powers are truly good or bad and where they come from.

As Elsa gets closer to uncovering the truth, her desperation grows, leading her to act more recklessly. Anna, in turn, becomes increasingly anxious—her entire sense of purpose is tied to Elsa, so the thought of losing her is unbearable. If something happens to Elsa, Anna would not only grieve for the sister she loves but also for the identity and life she has built around protecting her. This fuels a mirrored recklessness between the two: Elsa throws herself into danger searching for answers, and Anna recklessly follows, determined to keep Elsa safe at all costs.

However, the key difference between them is that Elsa has magic to protect her, while Anna does not. Elsa is willing to put herself at risk, but when it comes to Anna, she cannot justify the same danger. This is what ultimately leads to their final confrontation. Elsa is ready to take that last step to find her purpose, even if it means sacrificing her safety, but she refuses to let Anna risk her life alongside her. Anna, however, sees Elsa’s mission for what it truly is—a quest for self-worth and martyrdom—and cannot fathom the idea of Elsa facing it alone.

Elsa: You said you believed in me that this is what I was born to do.

Anna: And I don't want to stop you from that. I-I don't want to stop you from being whatever you need to be. I just don't want you dying, trying to be everything for everyone else too. Don't do this alone. Let me help you, please. I can't lose you, Elsa.

Their codependency means that neither of them knows how to exist without the other, but this moment forces Anna to confront an identity outside of being Elsa’s protector, just as Elsa must learn to define herself without Anna’s constant reassurance.

Part 2: The Implications of the Scene

Ultimately, we now understand Anna and Elsa’s emotional states, and what leads to the confrontation in the boat scene. To understand how Elsa’s actions serve as an apology, we also need to examine what is actually said within the boat scene and how this moment builds up to her eventual apology.

In sending Anna away, Elsa believes she is protecting her, but the unspoken message behind her actions is what makes this moment so painful: by deciding that Anna cannot go with her, Elsa unintentionally reinforces the idea that Anna is not capable enough. This moment is heavily foreshadowed earlier in the film when Elsa first takes on the martyr role mentioned earlier, feeling personally responsible for the spirits’ awakening and the danger facing Arendelle. She decides that she must set things right—alone.

Grand Pabbie: When one can see no future, all one can do is the next right thing. Elsa: The next right thing is for me to go to the Enchanted Forest and find that voice.

Anna’s response mirrors the boat scene almost exactly:

Anna: You are not going alone. Elsa: Anna, no. I have my powers to protect me, you don’t. Anna: Excuse me, I climbed to the North Mountain, survived a frozen heart, and saved you from my ex-boyfriend, and I did it all without powers, so, you know, I'm coming.

Anna immediately becomes defensive, making it clear that she refuses to accept the idea that she is incapable just because she lacks magic. This early exchange sets up the emotional weight of the boat scene. However, this isn’t the first time this tension surfaces before the boat scene. After Elsa saves everyone from the Fire Spirit, she scolds Anna for recklessly jumping into the flames to protect her. Anna, bewildered by the accusation, pushes back, pointing out that Elsa was the one being reckless in the first place.

Elsa: Anna, are you okay? What were you thinking? You could have been killed—you can't just follow me into fire. Anna: If you don’t want me following you into fire, then don’t run into fire. You’re not being careful, Elsa.

Elsa’s repeated reminders that Anna doesn’t share her powers cut deep, striking at the core of Anna’s insecurities. Her entire life has been shaped by her devotion to Elsa, defining herself as her sister’s protector. But when Elsa physically removes her from the journey during the boat scene, Anna is forced to face a painful possibility: that in Elsa’s eyes, she isn’t strong enough to walk this path alongside her.

Elsa: The answers about the past are all there. Anna: So, we go to Ahtohallan? Elsa: Not we, Me.The dark sea is too dangerous for us both. Anna: No, we do this together. Remember the song, "Go too far and you'll be drowned"? Who will stop you from going too far?

For Anna, whose self-worth is tied to being Elsa’s anchor, this realization is devastating. Elsa—who is in the midst of her own reckless search for identity—uses Anna’s lack of power as a reason to push her away. This isn’t just an act of protection; to Anna, it feels like rejection, a sudden shift in the dynamic, the codependency, that has defined her entire existence.This is why Anna’s devastation in the boat scene goes beyond just fear for Elsa’s safety; it is about the identity crisis Elsa’s actions force her to confront. If she is not Elsa’s protector, then who is she?

Part 3: Show, Don’t Tell

After Elsa and Anna part ways in the boat scene, both embark on transformative journeys that reshape their identities and redefine their relationship. Elsa finds the answers she has been searching for, achieving self-actualization at the cost of temporarily losing herself in the process.

Meanwhile, Anna is forced to confront her worst fear—losing Elsa—and for the first time, she must navigate life without her sister at her side. However, rather than succumbing to despair, Anna channels her grief into action, taking charge and destroying the dam to save both Arendelle and the Enchanted Forest. In doing so, she unknowingly saves Elsa as well.

Their eventual reunion marks not only the resolution of their individual arcs but also an unspoken reconciliation between them.

Although Elsa never explicitly says the words "I'm sorry," her actions and dialogue upon reuniting with Anna serve as an apology—one rooted in subtext rather than direct acknowledgment. This is where the principle of "show, don’t tell" becomes crucial in understanding the resolution of their conflict.

Brandon McNulty’s video Good vs. Bad Dialogue outlines three essential rules for effective dialogue:

Sounds Natural – Dialogue should resemble realistic speech patterns.

Attacks or Defends an Idea – Dialogue must serve a purpose by reinforcing or challenging a concept.

Expresses Unspoken Meaning (Subtext) – Characters should convey emotions through implication rather than direct statements.