#equilibria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How to design a tech regulation

TONIGHT (June 20) I'm live onstage in LOS ANGELES for a recording of the GO FACT YOURSELF podcast. TOMORROW (June 21) I'm doing an ONLINE READING for the LOCUS AWARDS at 16hPT. On SATURDAY (June 22) I'll be in OAKLAND, CA for a panel (13hPT) and a keynote (18hPT) at the LOCUS AWARDS.

It's not your imagination: tech really is underregulated. There are plenty of avoidable harms that tech visits upon the world, and while some of these harms are mere negligence, others are self-serving, creating shareholder value and widespread public destruction.

Making good tech policy is hard, but not because "tech moves too fast for regulation to keep up with," nor because "lawmakers are clueless about tech." There are plenty of fast-moving areas that lawmakers manage to stay abreast of (think of the rapid, global adoption of masking and social distancing rules in mid-2020). Likewise we generally manage to make good policy in areas that require highly specific technical knowledge (that's why it's noteworthy and awful when, say, people sicken from badly treated tapwater, even though water safety, toxicology and microbiology are highly technical areas outside the background of most elected officials).

That doesn't mean that technical rigor is irrelevant to making good policy. Well-run "expert agencies" include skilled practitioners on their payrolls – think here of large technical staff at the FTC, or the UK Competition and Markets Authority's best-in-the-world Digital Markets Unit:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/13/kitbashed/#app-store-tax

The job of government experts isn't just to research the correct answers. Even more important is experts' role in evaluating conflicting claims from interested parties. When administrative agencies make new rules, they have to collect public comments and counter-comments. The best agencies also hold hearings, and the very best go on "listening tours" where they invite the broad public to weigh in (the FTC has done an awful lot of these during Lina Khan's tenure, to its benefit, and it shows):

https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/events/2022/04/ftc-justice-department-listening-forum-firsthand-effects-mergers-acquisitions-health-care

But when an industry dwindles to a handful of companies, the resulting cartel finds it easy to converge on a single talking point and to maintain strict message discipline. This means that the evidentiary record is starved for disconfirming evidence that would give the agencies contrasting perspectives and context for making good policy.

Tech industry shills have a favorite tactic: whenever there's any proposal that would erode the industry's profits, self-serving experts shout that the rule is technically impossible and deride the proposer as "clueless."

This tactic works so well because the proposers sometimes are clueless. Take Europe's on-again/off-again "chat control" proposal to mandate spyware on every digital device that will screen everything you upload for child sex abuse material (CSAM, better known as "child pornography"). This proposal is profoundly dangerous, as it will weaken end-to-end encryption, the key to all secure and private digital communication:

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jun/18/encryption-is-deeply-threatening-to-power-meredith-whittaker-of-messaging-app-signal

It's also an impossible-to-administer mess that incorrectly assumes that killing working encryption in the two mobile app stores run by the mobile duopoly will actually prevent bad actors from accessing private tools:

https://memex.craphound.com/2018/09/04/oh-for-fucks-sake-not-this-fucking-bullshit-again-cryptography-edition/

When technologists correctly point out the lack of rigor and catastrophic spillover effects from this kind of crackpot proposal, lawmakers stick their fingers in their ears and shout "NERD HARDER!"

https://memex.craphound.com/2018/01/12/nerd-harder-fbi-director-reiterates-faith-based-belief-in-working-crypto-that-he-can-break/

But this is only half the story. The other half is what happens when tech industry shills want to kill good policy proposals, which is the exact same thing that advocates say about bad ones. When lawmakers demand that tech companies respect our privacy rights – for example, by splitting social media or search off from commercial surveillance, the same people shout that this, too, is technologically impossible.

That's a lie, though. Facebook started out as the anti-surveillance alternative to Myspace. We know it's possible to operate Facebook without surveillance, because Facebook used to operate without surveillance:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3247362

Likewise, Brin and Page's original Pagerank paper, which described Google's architecture, insisted that search was incompatible with surveillance advertising, and Google established itself as a non-spying search tool:

http://infolab.stanford.edu/pub/papers/google.pdf

Even weirder is what happens when there's a proposal to limit a tech company's power to invoke the government's powers to shut down competitors. Take Ethan Zuckerman's lawsuit to strip Facebook of the legal power to sue people who automate their browsers to uncheck the millions of boxes that Facebook requires you to click by hand in order to unfollow everyone:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/02/kaiju-v-kaiju/#cda-230-c-2-b

Facebook's apologists have lost their minds over this, insisting that no one can possibly understand the potential harms of taking away Facebook's legal right to decide how your browser works. They take the position that only Facebook can understand when it's safe and proportional to use Facebook in ways the company didn't explicitly design for, and that they should be able to ask the government to fine or even imprison people who fail to defer to Facebook's decisions about how its users configure their computers.

This is an incredibly convenient position, since it arrogates to Facebook the right to order the rest of us to use our computers in the ways that are most beneficial to its shareholders. But Facebook's apologists insist that they are not motivated by parochial concerns over the value of their stock portfolios; rather, they have objective, technical concerns, that no one except them is qualified to understand or comment on.

There's a great name for this: "scalesplaining." As in "well, actually the platforms are doing an amazing job, but you can't possibly understand that because you don't work for them." It's weird enough when scalesplaining is used to condemn sensible regulation of the platforms; it's even weirder when it's weaponized to defend a system of regulatory protection for the platforms against would-be competitors.

Just as there are no atheists in foxholes, there are no libertarians in government-protected monopolies. Somehow, scalesplaining can be used to condemn governments as incapable of making any tech regulations and to insist that regulations that protect tech monopolies are just perfect and shouldn't ever be weakened. Truly, it's impossible to get someone to understand something when the value of their employee stock options depends on them not understanding it.

None of this is to say that every tech regulation is a good one. Governments often propose bad tech regulations (like chat control), or ones that are technologically impossible (like Article 17 of the EU's 2019 Digital Single Markets Directive, which requires tech companies to detect and block copyright infringements in their users' uploads).

But the fact that scalesplainers use the same argument to criticize both good and bad regulations makes the waters very muddy indeed. Policymakers are rightfully suspicious when they hear "that's not technically possible" because they hear that both for technically impossible proposals and for proposals that scalesplainers just don't like.

After decades of regulations aimed at making platforms behave better, we're finally moving into a new era, where we just make the platforms less important. That is, rather than simply ordering Facebook to block harassment and other bad conduct by its users, laws like the EU's Digital Markets Act will order Facebook and other VLOPs (Very Large Online Platforms, my favorite EU-ism ever) to operate gateways so that users can move to rival services and still communicate with the people who stay behind.

Think of this like number portability, but for digital platforms. Just as you can switch phone companies and keep your number and hear from all the people you spoke to on your old plan, the DMA will make it possible for you to change online services but still exchange messages and data with all the people you're already in touch with.

I love this idea, because it finally grapples with the question we should have been asking all along: why do people stay on platforms where they face harassment and bullying? The answer is simple: because the people – customers, family members, communities – we connect with on the platform are so important to us that we'll tolerate almost anything to avoid losing contact with them:

https://locusmag.com/2023/01/commentary-cory-doctorow-social-quitting/

Platforms deliberately rig the game so that we take each other hostage, locking each other into their badly moderated cesspits by using the love we have for one another as a weapon against us. Interoperability – making platforms connect to each other – shatters those locks and frees the hostages:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/facebooks-secret-war-switching-costs

But there's another reason to love interoperability (making moderation less important) over rules that require platforms to stamp out bad behavior (making moderation better). Interop rules are much easier to administer than content moderation rules, and when it comes to regulation, administratability is everything.

The DMA isn't the EU's only new rule. They've also passed the Digital Services Act, which is a decidedly mixed bag. Among its provisions are a suite of rules requiring companies to monitor their users for harmful behavior and to intervene to block it. Whether or not you think platforms should do this, there's a much more important question: how can we enforce this rule?

Enforcing a rule requiring platforms to prevent harassment is very "fact intensive." First, we have to agree on a definition of "harassment." Then we have to figure out whether something one user did to another satisfies that definition. Finally, we have to determine whether the platform took reasonable steps to detect and prevent the harassment.

Each step of this is a huge lift, especially that last one, since to a first approximation, everyone who understands a given VLOP's server infrastructure is a partisan, scalesplaining engineer on the VLOP's payroll. By the time we find out whether the company broke the rule, years will have gone by, and millions more users will be in line to get justice for themselves.

So allowing users to leave is a much more practical step than making it so that they've got no reason to want to leave. Figuring out whether a platform will continue to forward your messages to and from the people you left there is a much simpler technical matter than agreeing on what harassment is, whether something is harassment by that definition, and whether the company was negligent in permitting harassment.

But as much as I like the DMA's interop rule, I think it is badly incomplete. Given that the tech industry is so concentrated, it's going to be very hard for us to define standard interop interfaces that don't end up advantaging the tech companies. Standards bodies are extremely easy for big industry players to capture:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/30/weak-institutions/

If tech giants refuse to offer access to their gateways to certain rivals because they seem "suspicious," it will be hard to tell whether the companies are just engaged in self-serving smears against a credible rival, or legitimately trying to protect their users from a predator trying to plug into their infrastructure. These fact-intensive questions are the enemy of speedy, responsive, effective policy administration.

But there's more than one way to attain interoperability. Interop doesn't have to come from mandates, interfaces designed and overseen by government agencies. There's a whole other form of interop that's far nimbler than mandates: adversarial interoperability:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/10/adversarial-interoperability

"Adversarial interoperability" is a catch-all term for all the guerrilla warfare tactics deployed in service to unilaterally changing a technology: reverse engineering, bots, scraping and so on. These tactics have a long and honorable history, but they have been slowly choked out of existence with a thicket of IP rights, like the IP rights that allow Facebook to shut down browser automation tools, which Ethan Zuckerman is suing to nullify:

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

Adversarial interop is very flexible. No matter what technological moves a company makes to interfere with interop, there's always a countermove the guerrilla fighter can make – tweak the scraper, decompile the new binary, change the bot's behavior. That's why tech companies use IP rights and courts, not firewall rules, to block adversarial interoperators.

At the same time, adversarial interop is unreliable. The solution that works today can break tomorrow if the company changes its back-end, and it will stay broken until the adversarial interoperator can respond.

But when companies are faced with the prospect of extended asymmetrical war against adversarial interop in the technological trenches, they often surrender. If companies can't sue adversarial interoperators out of existence, they often sue for peace instead. That's because high-tech guerrilla warfare presents unquantifiable risks and resource demands, and, as the scalesplainers never tire of telling us, this can create real operational problems for tech giants.

In other words, if Facebook can't shut down Ethan Zuckerman's browser automation tool in the courts, and if they're sincerely worried that a browser automation tool will uncheck its user interface buttons so quickly that it crashes the server, all it has to do is offer an official "unsubscribe all" button and no one will use Zuckerman's browser automation tool.

We don't have to choose between adversarial interop and interop mandates. The two are better together than they are apart. If companies building and operating DMA-compliant, mandatory gateways know that a failure to make them useful to rivals seeking to help users escape their authority is getting mired in endless hand-to-hand combat with trench-fighting adversarial interoperators, they'll have good reason to cooperate.

And if lawmakers charged with administering the DMA notice that companies are engaging in adversarial interop rather than using the official, reliable gateway they're overseeing, that's a good indicator that the official gateways aren't suitable.

It would be very on-brand for the EU to create the DMA and tell tech companies how they must operate, and for the USA to simply withdraw the state's protection from the Big Tech companies and let smaller companies try their luck at hacking new features into the big companies' servers without the government getting involved.

Indeed, we're seeing some of that today. Oregon just passed the first ever Right to Repair law banning "parts pairing" – basically a way of using IP law to make it illegal to reverse-engineer a device so you can fix it.

https://www.opb.org/article/2024/03/28/oregon-governor-kotek-signs-strong-tech-right-to-repair-bill/

Taken together, the two approaches – mandates and reverse engineering – are stronger than either on their own. Mandates are sturdy and reliable, but slow-moving. Adversarial interop is flexible and nimble, but unreliable. Put 'em together and you get a two-part epoxy, strong and flexible.

Governments can regulate well, with well-funded expert agencies and smart, adminstratable remedies. It's for that reason that the administrative state is under such sustained attack from the GOP and right-wing Dems. The illegitimate Supreme Court is on the verge of gutting expert agencies' power:

https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2024/05/us-supreme-court-may-soon-discard-or-modify-chevron-deference

It's never been more important to craft regulations that go beyond mere good intentions and take account of adminsitratability. The easier we can make our rules to enforce, the less our beleaguered agencies will need to do to protect us from corporate predators.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/20/scalesplaining/#administratability

Image: Noah Wulf (modified) https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thunderbirds_at_Attention_Next_to_Thunderbird_1_-_Aviation_Nation_2019.jpg

CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#cda#ethan zuckerman#platforms#platform decay#enshittification#eu#dma#right to repair#transatlantic#administrability#regulation#big tech#scalesplaining#equilibria#interoperability#adversarial interoperability#comcom

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

hii i just recently read equilibria (which i realize was published two years ago but shh time isnt real) but i loved it so much!! honestly i dont typically read omegaverse but stumbled upon ur fic and it made me Think. like above being the sweetest love story and immaculate characterization you've written seungmins relationship with being an omega in such a raw and relatable way? anyways wanted to thank you for writing this fic thats been somewhat pivotal to my psyche. i rly hope ur doing well!!

hi lovely, thank you so much for reading and for your kind words <3 my deepest apologies for the lateness of this response and I hope my gratitude still manages to reach you, wherever you are. I also can't believe it's been two years...truly so much has happened since then. I'm so glad that the story and the characterization resonated with you in some way (especially as it revolves around a theme you usually don't read). happy (belated) new year and I hope you're well also! <3

0 notes

Text

#ruckis vandalizes#art#artists on tumblr#non fandom oc#order of the stars#sire#weirdfur#furry art#furry#taur#multilimb#Ref#reference#oc#original character#anthro#cartoon#robot#scifi#celestial#angel#Equilibrias#fox#hedgehog#gopher#cat

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

worst feeling's when a topic isn't even complicated or hard it's just so BORING but you still have to revise it

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

No, this was a simple case of the market supplying what buyers (schools) wanted:

Simplicity above all else.

Before Chromebooks, schools were full of Macs. Time was every school library and computer room was full of this guy, the iMac G3,

sometimes in color and other times in plain white. Because it was the simplest, easiest to configure, hardest to fuck up, least user-modifiable PC available. And it was available fairly cheap - not below cost, because they're not idiots (nor is Google), but for fairly low profit margins.

Then the Chromebook was developed, specifically for that market. I was on the Chromebook team for a while, and let me tell you, they were pushing for adoption in a hell of a lot more places than schools. But schools bought them, because they were even simpler to configure and even harder to fuck up than the Macs (and, relatedly, also cheaper). Many large companies were equally interested, because for large company purposes they are, just like at schools, obviously and massively superior, but due to principal-agent problems the people making the purchasing decisions stood to lose money if they switched*, so it was only the schools that could switch over easily.

No one was selling anything at a loss. No one was doing anything sinister. The market - specifically the many, many overworked and underpaid local school sysadmins - begged for something simpler, harder for kids to fuck up. And the foolproof way to keep kids from fucking up school hardware is to prevent them from modifying the software on that hardware. And so the market delivered.

Stallman was right - by using unfree software as our primary day to day tools, we lost the habit of and ability to modify those tools, and therefore stopped teaching people how to do it competently. He can wave the flag now and point to his predictions come true, and I hope it gives him a little (cold) comfort in his old age.

But the local incentives pointed toward closed-source and idiot-proof devices. Every small step toward that has obvious benefits and diffuse costs, and people are mostly idiots. There was never any conspiracy; there would be no reason for one, since the natural incentive of everyone, selling, buying, manufacturing, or coding, was to saunter vaguely downwards toward closed ecosystems.

There wasn't a conspiracy. There never is. Just inadequate equilibria.

We need to lay more blame for "Kids don't know how computers work" at the feet of the people responsible: Google.

Google set out about a decade ago to push their (relatively unpopular) chromebooks by supplying them below-cost to schools for students, explicitly marketing them as being easy to restrict to certain activities, and in the offing, kids have now grown up in walled gardens, on glorified tablets that are designed to monetize and restrict every movement to maximize profit for one of the biggest companies in the world.

Tech literacy didn't mysteriously vanish, it was fucking murdered for profit.

#*I can explain this in some detail and probably will as a second reblog#corrections#inadequate equilibria#stallman was right

78K notes

·

View notes

Text

kicking my legs and twirling my hair im having sooooo much fun (<- reading about zermelo’s theorem again)

#it’s SO real like all finite two player games of complete information with alternating moves#do have a solution that can be discerned from identifying nash equilibria via backwards induction…..#samael speaks

1 note

·

View note

Text

Consider the following non-cooperative game with n ≥ 2 players: Each player simultaneously chooses one element in {Yes, No}. If every player chooses No, then the payoff for every player is a < 0. If at least one player chooses Yes, then the payoff for every player who chose Yes is 0, and the payoff for every player who chose No is b > 0.

Among the deterministic strategy profiles, the Nash equilibria are the ones in which exactly one player chooses Yes, and every other player chooses No. The non-deterministic Nash equilibrium in which every player has the same strategy is the one in which every player chooses No with probability (b/(b-a))^(1/(n-1)); this is an unstable equilibrium.

I'm thinking about this mostly as a small exercise while trying to teach myself introductory game theory. I do think it could be somewhat representative of real-life situations in which, in order to avoid catastrophe, you need a certain number of your population to do something to which there's a cost, but as long as you meet that number, there's no additional benefit to exceeding that number. An example is voting in a popular election, if you restrict to a group of citizens who will either vote for the better candidate or refrain from voting: To avoid the bad consequences of the worse candidate winning, you need enough people to vote, but as long as the better candidate wins, there's actually an opportunity cost to more than 'enough' people voting. (I'm neglecting side effects that might depend on the margin of victory, like increased faith in civic processes; just assume that the only consequence of voting to determine the winner of the election.)

I think it might be harder in real life for an outside enforcer to 'solve' this problem than to solve something like the prisoner's dilemma. In the prisoner's dilemma, the optimum occurs when both/all players have the same strategy (of cooperation), so you can just make the cost of defection very high for both/all players to incentivise them to cooperate. In this problem that I've described, the optimum occurs when the players behave 'asymmetrically', so you'd have to choose one player and give him different incentives than the rest. If you give all the players the same incentives, then the best you can do is to get all of them to choose Yes or to get all of them to achieve the non-deterministic equilibrium previously described; in both of these cases, the (expected) sum of payoffs over all players is 0, while in the optimum, the sum of payoffs is (n-1)a > 0. In real life, 'asymmetry' can be hard to enforce when there isn't an apparent way to select which players take which strategy; there's often some expectation of 'fairness', e.g., when your enforcing body is a government. (Of course, in real life, there are also typically some inherent costs corresponding to 'unfairness' or inequality.)

#why does the spell-check think that 'equilibria' is not a word...?#also why does the italicisation keep shifting to other characters that are not the ones I selected...?#that's what I get for trying to write mathematics in a text-box I guess

0 notes

Text

got nerd g(b)f!!

nerd gf ok i genuinely think you're majorly datable. tell me more about lost media and extinct snails

i made a uquiz to find out what kind of gf you are

#no but real actually#I will talk about chemistry to you for 30 mins straight#one time I argued w irl about acid base equilibria#BUT YES when I finish this cheese manufacturing paper I will literally talk about it nonstop

74K notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientific American endorses Harris

TONIGHT (October 23) at 7PM, I'll be in DECATUR, GEORGIA, presenting my novel THE BEZZLE at EAGLE EYE BOOKS.

If Trump's norm-breaking is a threat to democracy (and it is), what should Democrats do? Will breaking norms to defeat norms only accelerate the collapse of norms, or do we fight fire with fire, breaking norms to resist the slide into tyranny?

Writing for The American Prospect, Rick Perlstein writes how "every time the forces of democracy broke a reactionary deadlock, they did it by breaking some norm that stood in the way":

https://prospect.org/politics/2024-10-23-science-is-political/

Take the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, and the Reconstruction period that followed it. As Jefferson Cowie discusses, the 13th only passed because the slave states were excluded from its ratification, and even then, it barely squeaked over the line. The Congress that passed reconstruction laws that "radically reconstructed [slave states] via military subjugation" first ejected all the representatives of those states:

https://newrepublic.com/article/182383/defend-liberalism-lets-fight-democracy-first

The New Deal only exists because FDR was on the verge of packing the Supreme Court, and, under this threat, SCOTUS stopped ruling against FDR's plans:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/09/20/judicial-equilibria/#pack-the-court

The passage of progressive laws – "the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, and Medicaid" – are all thanks to JFK's gambit of packing the House Rules Committee, ending the obstructionist GOP members' use of the committee to kill anything that would protect or expand America's already fragile social safety net.

As Perlstein writes, "A willingness to judiciously break norms in a civic emergency can be a sign of a healthy and valorous democratic resistance."

And yet…the Democratic establishment remains violently allergic to norm-breaking. Perlstein recalls the 2018 book How Democracies Die, much beloved of party elites and Obama himself, which argued that norms are the bedrock of democracy, and so the pro-democratic forces undermine their own causes when they fight reactionary norm-breaking with their own.

The tactic of bringing a norm to a gun-fight has been a disaster for democracy. Trump wasn't the first norm-shattering Republican – think of GWB and his pals stealing the 2000 election, or Mitch McConnell stealing a Supreme Court seat for Gorsuch – but Trump's assault on norms is constant, brazen and unapologetic. Progressives need to do more than weep on the sidelines and demand that Republicans play fair.

The Democratic establishment's response is to toe every line, seeking to attract "moderate conservatives" who love institutions more than they love tax giveaways to billionaires. This is a very small constituency, nowhere near big enough to deliver the legislative majorities, let alone the White House. As Perlstein says, Obama very publicly rejected calls to be "too liberal" and tiptoed around anti-racist policy, in a bid to prevent a "racist backlash" (Obama discussed race in public less than any other president since the 1950s). This was a hopeless, ridiculous own-goal: Perlstein points out that even before Obama was inaugurated, there were more than 100 Facebook groups calling for his impeachment. The racist backlash was inevitable had nothing to do with Obama's policies. The racist backlash was driven by Obama's race.

Luckily, some institutions are getting over their discomfort with norm-breaking and standing up for democracy. Scientific American the 179 year-old bedrock of American scientific publication, has endorsed Harris for President, only the second such endorsement in its long history:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/vote-for-kamala-harris-to-support-science-health-and-the-environment/

Predictably, this has provoked howls of outrage from Republicans and a debate within the scientific community. Science is supposed to be apolitical, right?

Wrong. The conservative viewpoint, grounded in discomfort with ambiguity ("there are only two genders," etc) is antithetical to the scientific viewpoint. Remember the early stages of the covid pandemic, when science's understanding of the virus changed from moment to moment? Major, urgent recommendations (not masking, disinfecting groceries) were swiftly overturned. This is how science is supposed to work: a hypothesis can only be grounded in the evidence you have in hand, and as new evidence comes in that changes the picture, you should also change your mind.

Conservatives hated this. They claimed that scientists were "flip-flopping" and therefore "didn't know anything." Many concluded that the whole covid thing was a stitch-up, a bid to control us by keeping us off-balance with ever-changing advice and therefore afraid and vulnerable. This never ended: just look at all the weirdos in the comments of this video of my talk at last summer's Def Con who are absolutely freaking out about the fact that I wore a mask in an enclosed space with 5,000 people from all over the world in it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EmstuO0Em8

This intolerance for following the evidence is a fixture in conservative science denialism. How many times have you heard your racist Facebook uncle grouse about how "scientists used to say the world was getting colder, now they say it's getting hotter, what the hell do they know?"

Perlstein points to other examples of this. For example, in the 1980s, conservatives insisted that the answer to the AIDS crisis was to "just stop having 'illicit sex,'" a prescription that was grounded in a denial of AIDS science, because scientists used to say that it was a gay disease, then they said you could get it from IV drug use, or tainted blood, or from straight sex. How could you trust scientists when they can't even make up their minds?

https://www.newspapers.com/image/379364219/?terms=babies&match=1

There certainly are conservative scientists. But the right has a "fundamentally therapeutic discourse…conservatism never fails, it is only failed." That puts science and conservativism in a very awkward dance with one another.

Sometimes, science wins. Continuing in his history of the AIDS crisis, Perlstein talks about the transformation of Reagan's Surgeon General, C Everett Koop. Koop was an arch-conservative's arch-conservative. He was a hard-right evangelical who had "once suggested homosexuals were sedulously recruiting boys into their cult to help them take over America once they came of voting age." He'd also called abortion "the slide to Auschwitz" – which was weird, because he'd also opined that the "Jews had it coming for refusing to accept Jesus Christ."

You'd expect Koop to have continued the Reagan administration's de facto AIDS policy ("queers deserve to die"), but that's not what happened. After considering the evidence, Koop mailed a leaflet to every home in the USA advocating for condom use.

Koop was already getting started. His harm-reduction advocacy made him a national hero, so Reagan couldn't fire him. A Reagan advisor named Gary Bauer teamed up with Dinesh D'Souza on a mission to get Koop back on track. They got him a new assignment: investigate the supposed psychological harms of abortion, which should be a slam-dunk for old Doc Auschwitz. Instead, Koop published official findings – from the Reagan White House – that there was no evidence for these harms, and which advised women with an AIDS diagnosis to consider abortion.

So sometimes, science can triumph over conservativism. But it's far more common for conservativism to trump science. The most common form of this is "eisegesis," where someone looks at a "pile of data in order to find confirmation in it of what they already 'know' to be true." Think of those anti-mask weirdos who cling to three studies that "prove" masks don't work. Or the climate deniers who have 350 studies "proving" climate change isn't real. Eisegesis proves ivermectin works, that vaccinations are linked to autism, and that water fluoridation is a Communist plot. So long as you confine yourself to considering evidence that confirms your beliefs, you can prove anything.

Respecting norms is a good rule of thumb, but it's a lousy rule. The politicization of science starts with the right's intolerance for ambiguity – not Scientific American's Harris endorsement.

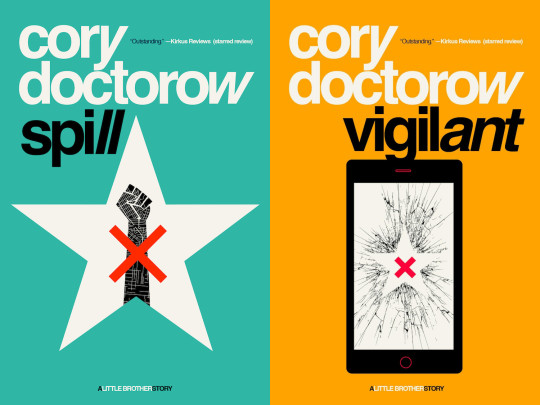

Tor Books as just published two new, free LITTLE BROTHER stories: VIGILANT, about creepy surveillance in distance education; and SPILL, about oil pipelines and indigenous landback.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/10/22/eisegesis/#norm-breaking

#pluralistic#scientific american#science#sciam#rick perlstein#the reactionary mind#conservativism#norm-breaking#slavery#13th amendment#new deal#pack the court#house rules committee#how democracies die

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

day 46/100

7 qns off DE tut

finished remaining acid base equilibria notes + tut (idk it was hard and i feel cooked)

~6 hours 12 min on ypt~ ( im sorry im so bad at everything 🤡)

#studyblr#productivity#academic victim#study motivation#trying#studyspo#stem#studying#stem student#100 days of productivity#mathblr#calculus#chemblr#a levels

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parents have no instinct for giving their kids sex ed because in ye olde ancestral environment, kids would just have experimental sex with each other and there would be nothing the parents could really do about it

cant do two polls in one post so a school sex ed poll will be added as a reblog

#not saying the ancestral environment was great for everyone#it would have sucked for afabs and autistic people in particular#but there are particular bad equilibria that are uniquely modern

613 notes

·

View notes

Text

23 December 2023

Still not a fan of phase equilibria but at least the topic is a little less mysterious to me now

#maybe these gibbs triangles *won't* be the death of me after all#mine#studyblr#studyspo#study motivation#chemblr#chemistry#stemblr#sciblr#op

107 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't know if you've made a post about this already, but any clue how old Kenpachi is? Like, obviously not his exact age, but compared to other characters? Because, like, for instance, he gives me the vibe of being younger than Kisuke, but I'm not sure that makes sense timeline-wise. Then there's also the fact that he knew Retsu while she was the first Kenpachi, but then it's only 9 Kenpachis later that he showed up in Seireitei...help

I feel like Zaraki is one of those ageless Entities in Soul Society, and if anyone studied him it'd prove that time in Rukongai is even more wimey than anyone could know--particularly out there, in that thing called "80th" that may itself not have an outer boundary, might continue indefinitely, or perhaps even at will. No one's ever been, at least no one who's told the tale to the Seireitei. He has no age because time has no form out there; only once wrestled into the Seireitei and the Gotei with its calendars and seasons has he had any relationship to it at all, though his degree of reiatsu tests this hold perpetually.

Mayuri hates Zaraki too much to want to deal with him (or to admit that Zaraki has anything he wants) but secretly and furiously, Mayuri thinks Zaraki would be a great specimen to study, as far as entities from the outer outer reaches go. Something something negligible senescence, something something lives lived in a series of true punctuated equilibria (emphasis on punctuation, even puncture).

Some in Soul Society live lives that are long, more or less linear, all one song; others, several lives in succession, captured in one lifetime; and still others, only in single moments, in seeming independence from one another. Those for whom the only moment that matters is the one you're in, and even then only matters if that moment is a fight worth having. (But then, of course, maybe that independence is a fantasy, and memory comes for everyone. In a cave, at the end of a blade that belongs to someone who is ready to live out her final succession.)

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Interesting Fact About Chemical Equilibria

The rate of a chemical reaction is the speed at which it proceeds. It is primarily affected by the concentration of reactants. So, a chemical reaction will start out fast because the reactants are still abundant, but the reaction will slow down as it proceeds, because the concentration of reactants decreases.

A reversible chemical reaction is one that can occur in both the forwards and backwards direction. Consider the formation of carbonic acid, and the decomposition of carbonic acid.

CO2 + H2O => H2CO3

H2CO3 => CO2 + H2O

Carbon dioxide can react with water to form carbonic acid, and carbonic acid can decompose to form carbon dioxide and water. Each of these reactions have their own rates, which depend on the concentration of reactants. If there is a lot of CO2, but little H2CO3, the formation of carbonic acid will be fast, and its decomposition will be slow, so the total amount of carbonic acid will rise. If the there is much carbonic acid but little carbon dioxide, the formation will be slow and the decomposition will be fast, so the total amount of carbonic acid will fall.

But if the concentrations of carbonic acid and carbon dioxide are just right, the rate of the forward reaction will equal the rate of the backwards reaction, and the amount of carbonic acid formed will equal the amount of carbonic acid decomposed. There will be no net change in the amount of each chemical species, and the system is said to be in equilibrium.

Now I will propose a new chemical system, with hypothetical reactants A, B, and C.

A => B

B => C

C => A

If all three reactions were to proceed at the same rate, the system would be in equilibrium. A would turn into B just as fast as C turns into A, which is just as fast as B turns into C. There would be no net change in the amount of each chemical species. This is an unusual type of equilibrium because it consists not of one reversible reaction, but of three separate irreversible reactions.

But is such a chemical system possible? As it turns out, no! The reason why is thermodynamics.

Thermodynamics is the study of energy, and chemists use the concept of Gibbs free energy (G) to describe the amount of energy in a chemical system. If a chemical reaction would cause the amount of energy in system to increase (∆G > 0) it must use energy. If it causes the energy to decrease (∆G < 0), it produces energy. For a chemical system in equilibrium, there is no change in the properties of the system, and therefore no change in energy, so (∆G = 0).

An irreversible chemical reaction always has a negative ∆G, otherwise, it would not occur. Some reactions have a positive ∆G values, for example protein synthesis, but they only occur because they are combined with reactions with negative ∆G values, for example ATP hydrolysis, so they have a negative ∆G overall.

The chemical system outlined above is in equilibrium, so the overall ∆G should be zero. However, each of the reactions is irreversible, so they should each have a negative ∆G. The total ∆G is equal to the ∆G of each reaction, so this would mean that three negative numbers must add to equal zero. That's impossible. Therefore, a chemical system in equilibrium must be formed only of reversible chemical reactions in equilibrium, not of multiple irreversible reactions.

So, I introduce a fundamental law of chemistry:

In a chemical system in equilibrium, all chemical reactions are in equilibrium.

In other words, equilibrium systems don't have time directionality. Their reactions happen backwards in the same way as forwards.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now what the fuck was that.

I have the AP Chemistry exam today, wish me luck!!

#😀 🔫#SO MUCH SOLUBILITY EQUILIBRIA AND CALORIMETRY#WHERE THE FUCK WAS THE REST OF UNIT 3 AND 4#aren’t these supposed to be weighted equally 😭#I hate electrochem with a passion but at least it wasn’t too bad

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the future looks something like: large renewable deployment that will still never be as big as current energy consumption, extractivism of every available mineral in an atmosphere of increasing scarcity, increasing natural disasters and mass migration stressing the system until major political upheavals start kicking off, and various experiments in alternative ways to live will develop, many of which are likely to end in disaster, but perhaps some prove sustainable and form new equilibria. I think the abundance we presently enjoy in the rich countries may not last, but I don't think we'll give up our hard won knowledge so easily, and I don't think we're going back to a pre-industrial past - rather a new form of technological future.

That's the optimistic scenario. The pessimistic scenarios involve shit like cascading economic and crop failures leading to total gigadeaths collapse, like intensification of 'fortress europe' walled enclaves and surveillance apparatus into some kinda high tech feudal nightmare, and of course like nuclear war. But my brain is very pessimistic in general and good at conjuring up apocalyptic scenarios, so I can't exactly tell you the odds of any of that. I'm gonna continue to live my life like it won't suddenly all end, because you have to right?

Shit that developed in the context of extraordinarily abundant energy and compute like LLMs and crypto and maybe even streaming video will have a harder time when there's less of it around, but the internet will likely continue to exist - packet-switching networks are fundamentally robust, and the hyper-performant hardware we use today full of rare earths and incredibly fine fabs that only exist at TSMC and Shenzhen is not the only way to make computing happen. I hold out hope that our present ability to talk to people in faraway countries, and access all the world's art and knowledge almost instantly, will persist in some form, because that's one of the best things we have ever accomplished. But archival and maintenance is a continual war against entropy, and this is a tremendously complex system alike to an organism, so I can not say what will happen.

56 notes

·

View notes