#emile littler

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The actor Brigit Forsyth, who has died aged 83, made her name as Thelma in the BBC television series Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads? One critic described Thelma as so prim that she could turn the lifting of a lace curtain into an art form.

Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais’s creation, which ran from 1973 to 1974, was the sequel to the popular 1960s sitcom The Likely Lads, which starred Rodney Bewes and James Bolam as Bob Ferris and Terry Collier, two single north-east England factory workers who share a flat and the same interests – women, drink and football.

Thelma Chambers was brought in as a girlfriend for the upwardly mobile Bob, now in the white-collar class with a house, car and annual holiday on the Costa Brava, scoffed at by Terry, who clings on to his working-class roots. Thelma and Bob were married halfway through the two series of the show.

“Up until then, I had done a lot of drama on telly,” said Forsyth. “If I wasn’t being murdered, I was murdering somebody or I was a disturbed art teacher. I was playing quite a lot of deranged people, so comedy was a nice change.”

She created laughs again with the sitcom Sharon and Elsie (1984-85), in which she co-starred as the middle-class Elsie Beecroft alongside Janette Beverley as the more down-to-earth Sharon Wilkes, two employees in a greetings card manufacturing company.

But Forsyth’s own favourite television part was Francine Pratt in Playing the Field (1998-2002), the on- and off-pitch women’s football drama created by Kay Mellor. Her character, who hates the game, is married to the Castlefield Blues’ sponsor, played by Ricky Tomlinson, and keeps him happy in return for designer clothes and other luxuries.

“I have never played awful glamour before,” she said. “I had a blond wig, six-inch heels, makeup and my bosom hitched up high.”

Forsyth was born in Malton, North Yorkshire, to Scottish parents, Anne (nee Forsyth), an artist, and Frank Connell, an architect and town planner, and brought up in Edinburgh. She was mesmerised by Stanley Baxter’s performances as a pantomime dame at the city’s King’s theatre and, aged 18, landed her own first lead role, as Sarat Carn, on her way to the gallows, in Charlotte Hastings’s play Bonaventure with the Makars amateur drama group.

But when she left St George’s school, Edinburgh, her parents insisted she learn a skill, so she trained as a secretary. After a couple of jobs, she headed for London and Rada (1958-60), where she won the Emile Littler prize.

She began her professional career back in Edinburgh with the Gateway theatre company (1960-61) before moving on to the Theatre Royal, Lincoln (1961-62) and the Arthur Brough Players in Folkestone (1962). With other actors already named Brigit McConnell and Bridget O’Connell, she changed her professional name to Forsyth on her return to Lincoln in 1962.

At the Edinburgh festival three years later, she played one of the witches in a headline-making production of Macbeth. “That show caused an absolute uproar because they wanted the witches to have the bodies of young girls and the faces of old women, and they wanted us to have our top half naked,” Forsyth recalled. “But the Earl of Harewood, who was running the EIF at the time, said ‘No’. So they put nipple caps on us, which looked absolutely disgusting – and they used to drop off each night. It was absolutely hysterical.”

Later, in the West End, Forsyth played Annie in The Norman Conquests (Globe, now Gielgud, and Apollo theatres, 1974-76) and Dusa in the feminist play Dusa, Fish, Stas and Vi (Mayfair theatre, 1976-77). She put her TV breakthrough down to cutting her hair short. “It proved a tremendously lucky omen,” she said.

That break came with Adam Smith (1972), in which she played the younger daughter of the title character, a Scottish minister (Andrew Keir). The director, Brian Mills, then worked with Forsyth on the psychological thriller Holly (1972), when she took the part of a young art teacher kidnapped by a mentally unstable student. Forsyth and Mills married in 1976.

Television roles kept on coming. She was Veronica, one of the product-promotion team, in The Glamour Girls (1980-82), Harriet in the inter-generational sitcom Tom, Dick and Harriet (1982-83), and Helen Yeldham, a hotelier, in the 1989 series of Boon.

There were also appearances in soap opera: as GP Judith Vincent in The Practice (1985-86); Babs Fanshawe, Ken Barlow’s escort agency date who dies of a heart attack, in a 1998 Coronation Street episode; Delphine LaClair, a sales rep for a French company interested in buying Rodney Blackstock’s vineyards, for two short runs in Emmerdale (2005 and 2006); Cressida, mother of the millionaire Nate Tenbury-Newent, in Hollyoaks in 2013; and three roles in Doctors between 2000 and 2012.

Forsyth also played the miserable Madge, who frustrates her sister Mavis’s attempts at a relationship with Granville, in the sitcom sequel Still Open All Hours (2013-19).

A cellist from the age of nine, Forsyth starred as the real-life virtuoso Beatrice Harrison in a 2004 tour of The Cello and the Nightingale. Also on tour, she was a remarkably believable Queen Elizabeth II in A Question of Attribution (2000) and played Marie in Calendar Girls (2008). “I’m Mrs Frosty-Knickers, the one who doesn’t approve of it all.”

In 2017, she played a terminally ill musician in the stage comedy Killing Time, written by her daughter, Zoe Mills, who acted alongside her. At the time, Forsyth revealed that her maternal grandfather, a GP in Yorkshire, had helped dying patients to end their lives. Declaring herself a supporter of euthanasia, she said: “He bumped off probably loads of people with doses of morphine.”

In 1999, Forsyth separated from her husband, but they remained friends until his death in 2006. She is survived by their children, Ben and Zoe.

🔔 Brigit Forsyth (Brigit Dorothea Connell), actor, born 28 July 1940; died 1 December 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌹 DEARIL - CHAPTER 2 🩸

🤍 grim reaper!yandere x immortal!reader 🖤 nobody expects to watch their parents die, but those days always come. those meetings weren't fun. 🤍 warnings: death, dying of an illness, technically parentification, dying from drowning, implied suicide, yandere tendencies (still rather tame in this part) 🖤 rating: sfw

🕯️ masterlist 🕯️

it was a year and two months before you saw the figure again. things had been going well. your sister got married. your youngest brother was born. your twin had started his apprenticeship. it had all been going so well.

now, your mother is bound to her bed, coughing out blood every few hours. it reminds you too much of how you were on death's door. the scar aches every time you hear her coughs.

your dear mother isn't the only one sick in the village. but she is on the worse end of it. your father, the only doctor for miles and miles, has been running around trying to help and looking after your mother fell mostly on you. your littler siblings are kept far away from the bedroom, only seeing your mother for brief glimpses during dinner.

"how's ma?" emil, your younger brother, asks as you're feeding your youngest sibling. your mother has become too weak to do it herself.

"she's feeling rather well." you answer, knowing full well you're lying. you'd seen a hooded figure, shrouded in swirling shadows, walking through the village. you don't yet know who it is that's died, but at least it didn't come to your door yet.

emil looks sceptical, but leaves to play with his sister ella. you're left with your tiny little brother, silently staring at the wall as he eats. at this point you're just waiting. and you hate nothing more than waiting.

especially when it's on the grim reaper.

you're changing your mother's wet towel when she wakes up for the first time in the whole day. you almost don't notice it, until she reaches for your hands.

"[mc]." she rasps. you turn to her, taking her frail hand in between your own. yours are steady, strong. hers are shaking.

"yes, mama?" you ask softly.

"when i die..." she coughs. "look after your father will you? he's... he's so fragile. he'll try and be stupid once i'm gone."

"of course, mama." you mutter, not trying to argue with her. you both know she's dying. you both know your father loves her far too much. there'd be no point in denying it.

"good child." she relaxes back into her sheets. "you've always been such a good child."

you don't think so. good children don't kill people.

but you don't refute her then either. it's better to let her die thinking that her children are all good sweet angels. it's better for everyone. as she falls back asleep, you re-wet the towel and place it on her head. your poor angel of a mother. this isn't a fate she deserves.

you wait by her bedside that night too.

the dead eyes arrive in the dead of night. you notice the moment your mother stops breathing, knowing that the wait is over. you feel sort of horrible for how relieved you are over it.

"hello, soul." the figure greets, talking to you over your mother's corpse. it feels disrespectful.

"hello, strange figure." you say back, relaxing in your seat. your eyes start to droop, finally feeling like you can rest.

the figure silently extends his hand to your mother's corpse, from where a pallid hand rises. you watch with interest as your mother sits up, her corpse left behind to eternally sleep. she looks around with confusion before finally casting eyes on to the figure.

"i hope you know that your child was meant to die, not you." the figure reveals, much to your astonishment. your mother's eyes widen, but contrary to what the figure believed would happen, they soon soften and melt.

"wonderful." she sighs, a happy smile on her lips. your own eyes soften. she's probably pain free for the first time in months, finally without any worries. some part of you is glad that she finally died.

"you mortals confuse me yet again." the figure frowns.

"parents are meant to die for their children, i'd rather it me than any of them." your mother explains, smiling at you with such affection. you don't think she knows you can see her. "i'd rather not see them follow me to the afterlife any time soon."

"don't worry. this one you'll never see again." the figure mutters. your mother turns to him with confusion, but before she can question his words he squeezes her hand and she turns into a glowing ball.

"quite the thing to say." you finally talk as the figure deposits the glowing soul into his robes.

"it is the truth."

"i thought all souls were meant to die when they're told to?" you repeat the words he'd once said. the figure looks at you with surprise, the wilted rose of a blush appearing on his cheeks once again.

"..." you get no answer, only two dead eyes set on your tired body, very much still breathing and well. the silence stretches, and you really want to go sleep now.

"so... what'd you mean that i was supposed to die instead of ma-?"

the figure disappears into the shadows before you're even finished with your sentence. you scoff, leaning down onto the bed to sleep. you're bound to have a busy day tomorrow, especially once your father comes home. at least you no longer have to wait.

the funeral is two days later. you could barely call it a funeral though. too many people were dying in the village, there isn't time or space for proper funerals.

you spent the whole event comforting your poor father, and comforting your siblings. you know a few days later when your sister arrives you'll have to comfort her too. you don't think you need comforting much, but you've been wrong before. death mostly just makes you... numb.

everything becomes a lot after that, watching after your siblings, watching after your father, watching after the house and home... your father isn't in any condition to work anymore either, which leaves that all on you too. you're not nearly as good a doctor as he is, but at least you have no fear of catching the illness yourself.

your eyes never did get to rest.

you're walking home from another house visit, the poor kid would probably be dying tonight, when you catch sight of the figure again. he's walking towards you, hiding another one of those glowing souls inside his cloak.

"your father's at the bottom of the river."

you shiver hearing his callous words. you open your mouth to question him, but decide against it. you don't think a reaper would lie to you about something like that... but that does bring up a different question.

"why are you here to tell me?" you ask, your fingers tightening around your bag's strap. the news that your father is dead is slowly sinking in.

"..." the figure tilts his head, taking his hood down to look you in the eyes with his dead ones. "someday, these news will be too much for you and you will throw yourself into that knife of yours. i will be here the day that happens. only i can have that stubborn soul of yours."

"i don't think i have much say in such matters." you swiftly answer, almost automatically. the figure smirks, and chuckles. the sound is grating, like a knife in your throat. you would know.

"we'll see, my soul." the figure disappears.

you stand there for a moment, thinking. you'd promised your mother you'd look after your father. you'd failed. what a good child you are.

you start walking home again. there's dinner to be made.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red House

A wayward children self insert fanfic, part 1

In which you get to meet our hero and our villain before the story's even began

This is a story that does not necessarily need to be told. But no story needs to be told. They want to be told, wish to be read, and yearn to be adored.

This is a story you've heard before, set in a place you've been.

A little boy, not yet calling himself Emile, and truthfully not yet a little boy, but not quiet a little girl either, runs as fast as his feet will carry him across broken blacktop on a cool autumn day.

He'd just gotten off the school bus, and had gone home just long enough to empty his backpack of books and homework and refill it with toys and snacks. Then he was back out the door and running before his older brothers could ask him where he was off to, or worse yet, follow him.

The trailer park they lived in overflowed with kids coming home from the nearby school, and his house in particular overflowed the most. Five kids and two full time working parents rattling around in a three bedroom home of plastic and kindling was suffocating at times, especially when you were the smallest.

So the boy, not yet a boy, ran from the after school fights and arguments before they started, quickly ducking between bramble bushes at the mouth of the woods circling his home, and slid down a muddy hill that'd yet to dry from the rain two weeks ago.

"MIKEY!" He called, twisting down a well troded path through the woods until he came upon a makeshift house of plywood and garbage left to rot and ruin the forest around them.

Another little boy, littler than the not yet a boy, with thick glasses and short cut black hair, sat within the makeshift home, doing homework on a metal garden table with a half broken glass top.

"Emile," The smaller boy did not say, but for now we shall assume he did, "You could have just gotten off on my stop if you were gonna run straight here anyway."

The littler boy who's name was not Mikey, but instead Micheal, lived in the same trailer park as Emile and his many brothers, just up the street infact, a single stop earlier than Emile.

Unlike the older he did not go home before making the trip into the woods, because even if he had the door would have been locked, with a note from his foster parents saying they would be out until late, and to play outside for the day.

"Yeah, I COULD have, but then we wouldn't have anything to eat." Emile proclaimed as he shoulded his backpack off and dumped it's contents onto the tiny garden table. Some things tumbled through the hole in the table's top or over the edges and spilled onto the floor.

Great Value brand chips in single serving bags and Hug juice barrels and a single Great Value Swiss Roll pack with two chocolate rolls inside, a feast for the kings of the woods.

Micheal immediately shifted through the menagerie of snack foods, landing on a bag of almost cheetos and a blue hug juice which he opened by stabbing through the thin foil with his pencil. "Doesn't your mom get mad when you take too many snacks?"

Emile shrugged as he picked up a red hug, stabing into the foil with his sharp canines before sitting in an old tire with a blanket thrown over it, "Yeah, but she'll never know it was me. My brothers always eat more than we're supposed to anyway."

Micheal nodded and returned to his homework, his legs dangling from the green painted metal garden chair they'd found along side the broken table, supposedly thrown out together. If one was broken, they both were in the eyes of the original owner, making them both worthless.

"What're you working on?" Emile shifted in his spot, grabbing one of the stuffed animals he's packed in his bag that had tumbled out among the snacks.

"Fractions," Micheal answered without looking up, using his spare hand to dig into his not-cheetos bag, "Did you bring your homework? I'll do it for you if you want."

Emile let out a loud sigh, "Noooo, I dumped my bag out to quickly and left it at home. You woulda been bored anyway, it's just multiplication."

Micheal and Emile were the same age, but not the same grade. Though Micheal was far behind in the height department, he was a brilliant mind. He'd skipped from 2nd to 4th grade at his last school, which actually put him ahead of the 5th graders when he moved this past year. Sense he moved in the middle of the year he was currently stuck in Emile's class during the school day, but was doing 5th grade level lessons as homework to prepare to take the Finals at a 5th grade level. His teachers tell him if he does well enough on the final at the end of the year he can go into middle school next year.

Many people looking in would think what a brilliant and talented child, how amazingly lucky he was to be born so smart, and they wouldn't even be half right.

Micheal was a genius yet, but not because of luck, or genetics, or some invisible disability he'd yet to be diagnosed with. Micheal was smart with purpose, with intent to blast through school. The less years he had to spend learning basic division and decimal placement the better, because as soon as he was done with school he could get a job, and as soon as he could get a job, he could buy his own house, and as soon as he could buy his own house he could have his own key, and never ever be locked out to "Go play outside :)" ever again.

He can't be forced to move if he owns the house, he can't be restricted dinner if he made the dinner, he won't have to sleep on the couch or even the floor some nights because there were guests over who needed a bed more. His house, his rules.

Yes, Micheal was smart, smart enough to know his life wasn't fair, and it would never be fair, and it was up to him to tilt the unbalanced scale in his favor, and up until this year he'd planned to do so all on his own.

"So I'm thinking red."

"Red?" Micheal looked up from his homework to Emile, his first friend sense Kindergarten, sense all the moving, sense being the new kid three times in one year.

Emile sat up and smiled as he turned a notebook he'd had stashed in his tire chair to face Micheal, a crude drawing of a house done fully in red crayon sat squarely in the middle. "Red." He smiled confidently, the dye from his hug juice had colored his upper lip almost as bright as the poorly drawn house.

Micheal placed his pencil down and took in the house. Fully red, with four windows in the front with a round door perfectly in the center. There was even a window in the triangle that made up the roof, implying an attic. The yard was green with a crude version of a brown dog and a purple cat standing on either side of two people holding hands in the center, one with black hair and thick glasses, and the other in a triangle dress with long yellow hair.

Micheal nodded

"I like red."

#Emile's Writing#Wayward Children#Self Insert#Self insert fanfiction#Micheal Bleak#Me? Writing Micheal Bleak backstory fanfic? Nooooooo#Maybe.#Youngest of far too many siblings 🤝 Foster Care kid who keeps getting bounced from house to house#'We should get our own house where we can make the rules'#Anyone else grow up making plans with your friends to live together in the future platonically?#That is ALL I did#This is my MOST self indulgent fic series yet#Because this is a book self insert#But some people HAVE read this book#BTW THIS IS CANON DIVERGENT#We'll get there when we get there but like#It's more than JUST Micheal Bleak backstory#Me in the woods surrounded by Tetanus literally every day#God I wanna go out and find my old fort kfdjgkdfg#No clue where it is the woods have changed#But I wanna go anyway...

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

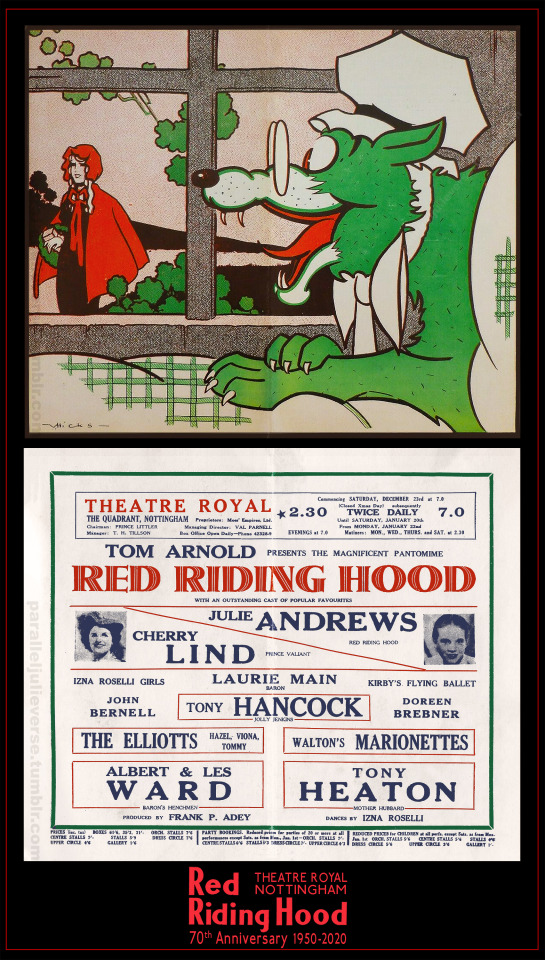

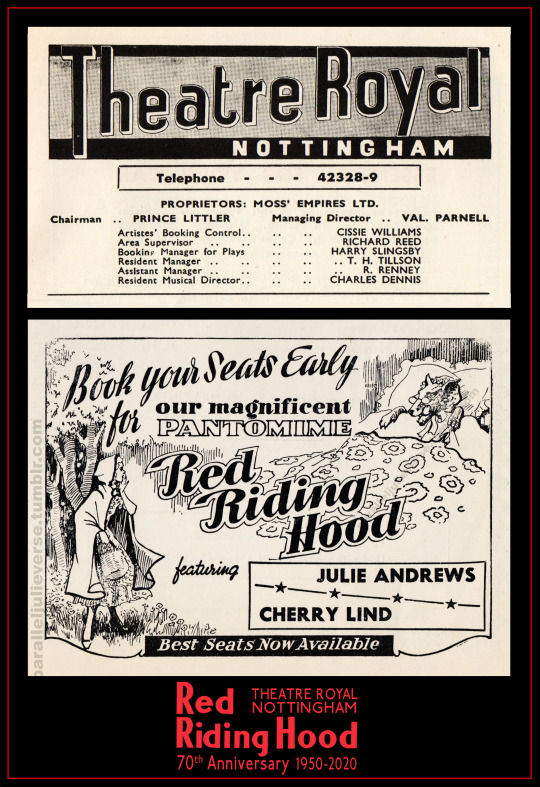

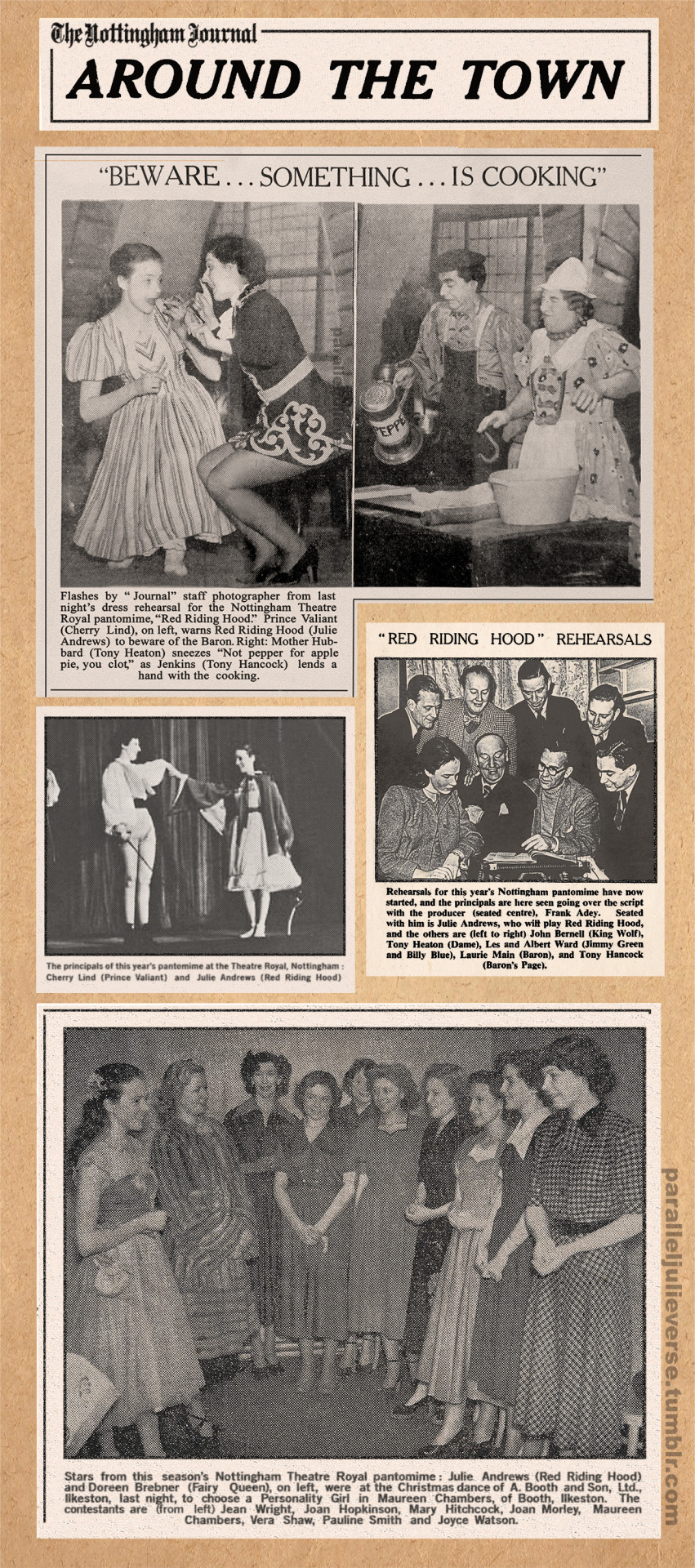

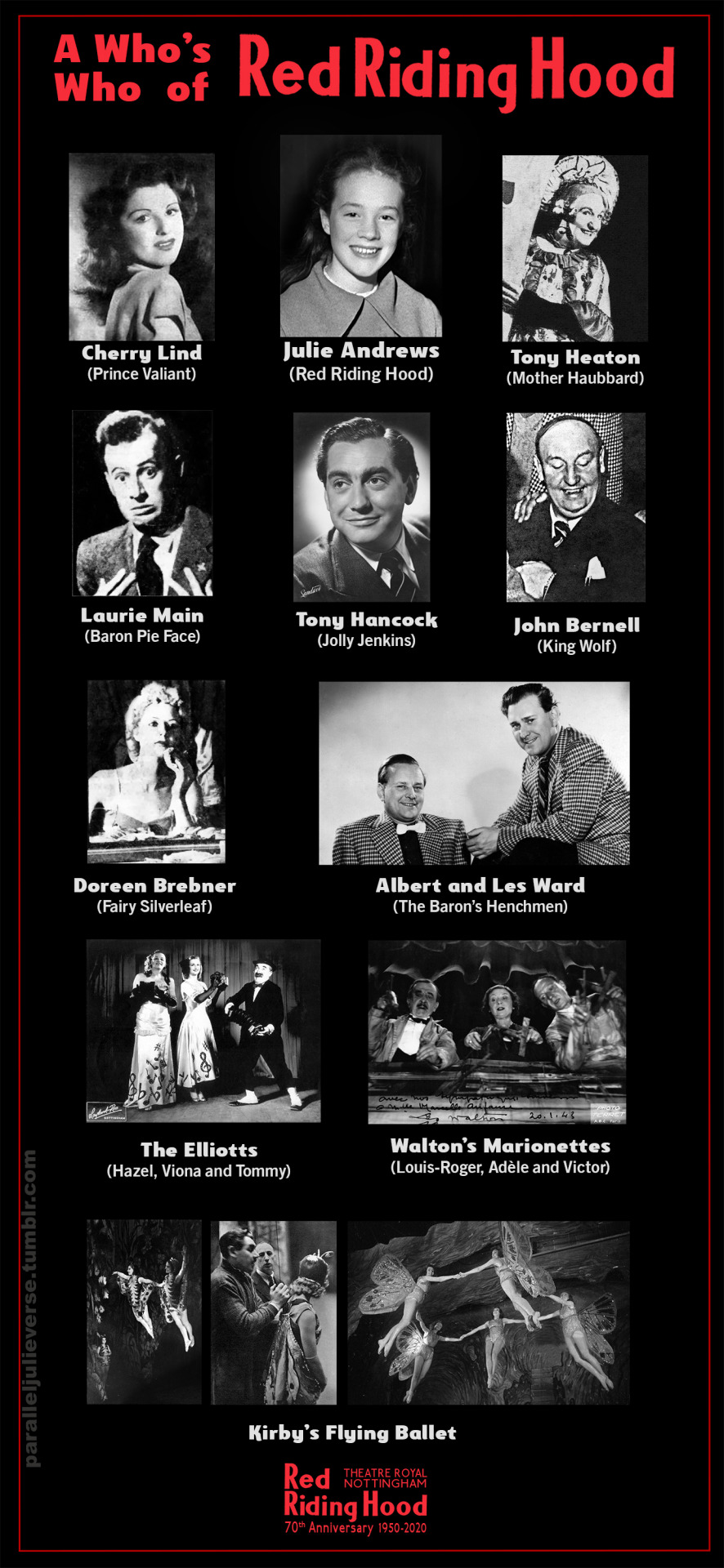

70th anniversary of Aladdin London Casino, 103 performances with 1 charity preview (19 December 1951 - 23 February 1952)

This week marks the 70th anniversary of another milestone event in the early career of Julie Andrews: the opening of Aladdin at the London Casino on 19 December 1951.

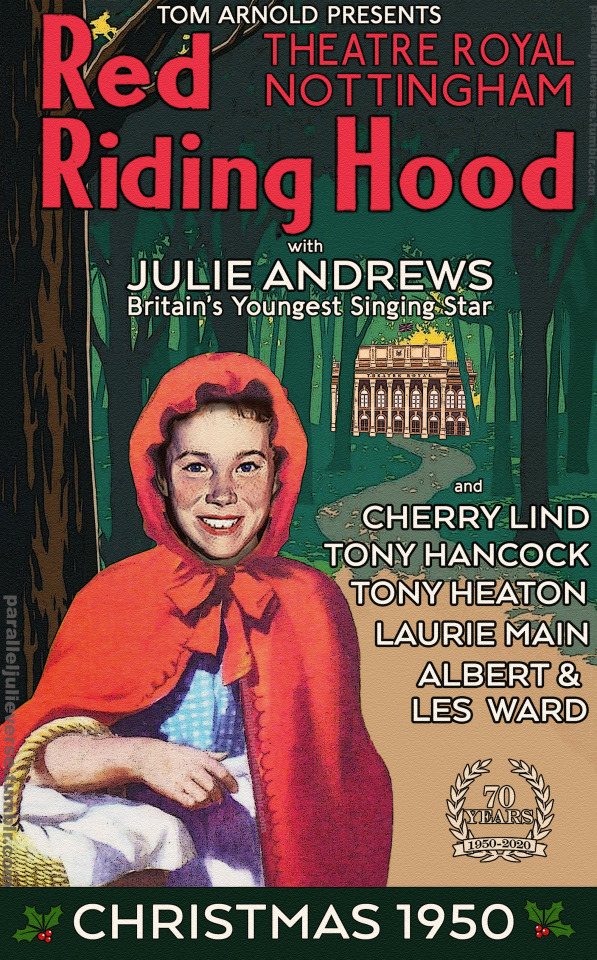

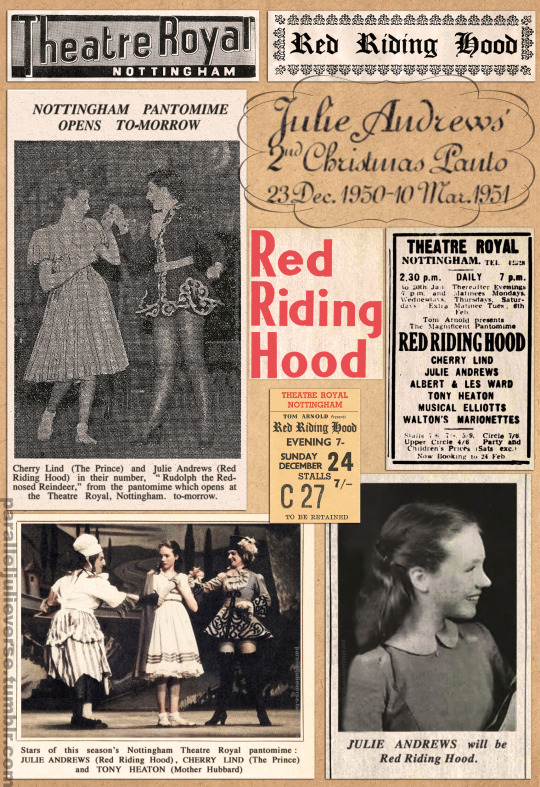

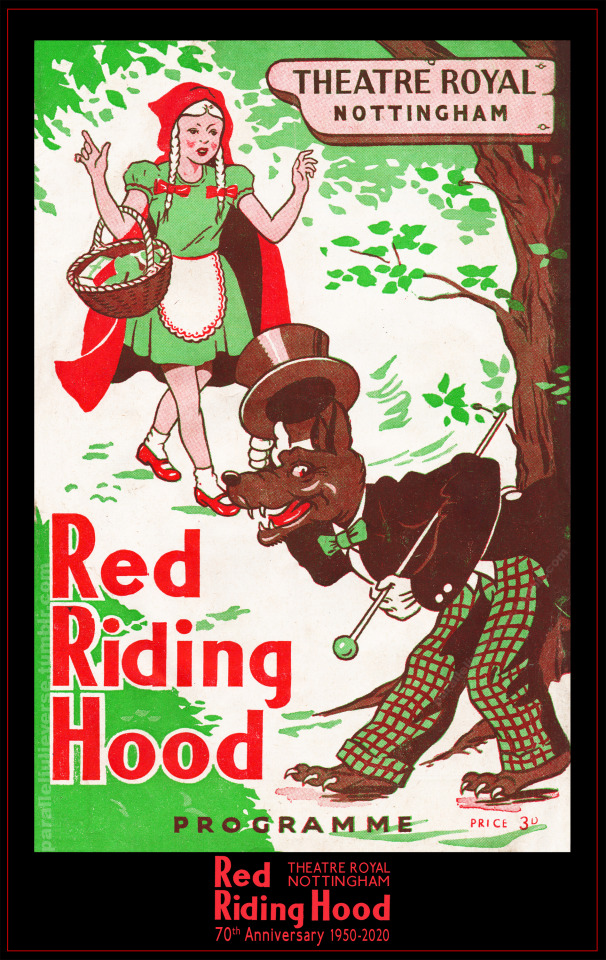

Aladdin was Julie’s third annual pantomime, following earlier runs in Humpty Dumpty (1948) and Red Riding Hood (1950). By Christmas 1951, Julie was 16-years-old and an established young star of variety and radio. She was thus 'promoted’ in Aladdin to the ‘principal girl’ role of Princess Balroulbadour — her first adult part — and given top billing alongside the show’s other principals, Jean Carson and Nat Jackley (Bishop, p. 6; ’Principal’, p. 5).

Aladdin also marked the second Christmas show Julie did with Emile Littler, the celebrated theatre impresario who, as discussed in an earlier post, was a formative figure in the star’s early career. Popularly dubbed the ‘King of Pantomimes’ -- a soubriquet which was, admittedly, shared by a few other theatre magnates -- Littler was famous for his legendary Christmas extravaganzas. In any given year, Littler would produce upwards of half-a-dozen pantos across the nationwide theatre chain he ran with brother, Prince, and sister, Blanche (Pedrick, p. 8).

A producer of the old school, Littler took an active role in these shows, not only producing but also writing, casting, and, in many cases, directing them himself (Pedrick, p. 8). Such was his commitment to pantos that Littler established a dedicated production facility in Birmingham, ‘Pantomime House’, where a team of craftsmen and women worked year-round to prepare the costumes, scenery and props needed for the lavish shows (Konig 1949). “No man,” opined one contemporary commentator, “has ever carried on such a wholesale enterprise for the production of Pantomime” (Wilson, p. 127).

For the Christmas season of 1951, Littler launched an ambitious roster of eight pantos across the country: alongside Aladdin at the London Casino, there was Little Miss Muffett at the Manchester Hippodrome; Puss in Boots at the Leeds Empire; Mother Goose at the Birmingham Royal; Humpty Dumpty at the Sheffield Empire; Jack and Jill at the Plymouth Palace; Cinderella at the Hanley Royal; and, Goody Two Shoes at the Bournemouth Pavilion (’Emile Littler Sends’, p. 5)

The biggest and most prestigious Littler panto was, not surprisingly, the London offering. Commencing in 1941, Littler staged a major West End panto each Christmas, initially at various theatres but, from 1946, moving permanently into the recently refurbished London Casino which Littler co-owned with Tom Arnold (Emile Littler Souvenir, p. 25; Knox, p. 314). Aladdin would be Littler’s eleventh London pantomime and his seventh at the Casino.

The show was based on a script treatment of Aladdin that Littler had developed for earlier productions. In keeping with panto traditions, the story is set in China, rather than the Middle Eastern locales popularised though later Hollywood versions of the tale (Chang, pp. 180-192). Aladdin is a carefree lad who lives in “Old Peking” with his mother, the laundress Widow Twankey, and his spoiled younger brother, Wishee Washee. Aladdin meets and falls in love with Princess Balroulbadour, much to the displeasure of her father, the Emperor, who charges his bumbling policemen to keep the impish lad away. Meanwhile, a mysterious stranger, Abanazar, has appeared claiming to be a long lost relative of Widow Twankey. He coaxes Aladdin to accompany him to a cave in the mountains so that he may retrieve a magical lamp. Aladdin finds the lamp but refuses to give it to Abanazar as promised. Cursed and imprisoned by Abanazar in the cave, Aladdin rubs the lamp, conjuring the magical genie, Kazim, who grants Aladdin his wish to become a wealthy Prince and thus clear the way for him to marry the Princess. Abanazar returns to create more mischief, stealing the lamp and using its power to transport the Princess and the entire Palace to Egypt. In possession of a magic ring, Aladdin summons the Fairy Queen who takes the lad to Egypt in pursuit where he thwarts Abanazar, wins back the Princess, and brings proceedings to a happy ending.

As is often the case with panto, the story of Aladdin is something of a pretext for the genre’s main points of appeal: spectacle, stars, music, comedy, and audience participation. With his 1951 staging of Aladdin, Little was determined to up the ante on all counts. Afforded a huge production budget of over £50,000, it was Littler’s most expensive panto to date and he pulled out all the stops with lavish production values, state-of-the-art stagecraft, and top-notch talent (Lloyd-Williams, p. 4; Wearing 2014, p. 138).

For the costume and scenery, Littler contracted Anthony Holland, a young set designer with a flair for visual spectacle (Hainaux 1965). The show’s Eastern settings were a perfect fit for Holland’s aesthetic and he went to town designing over a thousand costumes at a cost of £15,000 (Lloyd-Williams, p. 4). The sumptuous costumes were recalled fondly by Julie (2008) in the first volume of her memoirs: “I wore exotic, sparkling headdresses, which I loved, and a lot of satin kimono-style robes with long, draped arms” (p. 140). In addition, Holland designed fifteen changing sets for Aladdin complete with revolving buildings, a garden with a huge tree made of jade clouds, and a gasp-inducing cave of magical wonders. The result was what The Times described as “a breathless succession of marvels” (‘London Casino’, p. 6).

For the music, the show featured a mix of classic tunes interspersed with original compositions by Littler’s resident house composer, Hastings Mann (‘Hastings Mann’, p, 3). Overseeing the musical arrangement and direction for the production was Debroy Somers, the celebrated big band leader and star conductor (‘Debroy’ p. 3). Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado had just come out of copyright, and the musical team drew heavily from the score, interpolating several songs -- in one scene, the chorus sang ‘Gay Little Mandarins Are We’ to the tune of ‘Three Little Maids’ -- and using other musical motifs and bridges as entrance music (‘Christmas Shows’, p. 5).

The cherry on top of this spectacular theatrical and musical confection was the cast. Announced in October 1951, the cast for Aladdin was a star-studded line-up of big names from theatre, variety, film, dance, circus, and, even, opera. Other than Julie, the show’s featured performers included:

Jean Carson as Aladdin (principal boy): A vivacious flame-haired Yorkshire lass with a strong voice, comely appearance, and good comic flair, Carson started performing from a young age as part of her parents’ music hall act and she quickly emerged as a favourite on the variety and musical theatre circuit. In 1948, aged 20, she had an early success in Starlight Roof, the celebrated Val Parnell revue show at the London Hippodrome that also launched 12-year-old Julie Andrews to stardom. The same year Carson scored her first film role with a lead in the British musical revue, Date with a Dream (1948). Something of an Emile Littler protege, Carson appeared in several of his productions including a string of Christmas pantos where she typically took the part of the principal boy. She played the role of Aladdin in a 1948/49 Littler production at the Sheffield Empire which is possibly why she was tapped to recreate the role in the bigger London staging three years later ( ‘Provincial Pantomimes’, p. 8). Littler would also give Carson her greatest stage triumph when he cast her as the lead in the Hugh Martin scored musical, Love from Judy, a role she would play to great acclaim on the West End and elsewhere from 1951-1953. A film contract with Rank ensued where Carson starred in light musical comedies such as As Long As They’re Happy (1954) and An Alligator Named Daisy (1955). At the height of her British success, Carson was coaxed to the United States by a record-making TV deal where she was rechristened Jeannie -- to avoid confusion with the American TV star, Jean Carson of Peter Gunn and The Andy Griffith Show fame (‘Jean Carson makes’, p. 11). Carson’s US career got off to a promising start. She appeared in a number of well-received TV specials before being launched as the star of her own CBS TV sitcom, Hey, Jeannie! (1955). Sadly, the series failed to ignite and it was cancelled after just one season (Tucker, pp. 54-60). Thereafter, mainstream US success eluded Carson, though she continued to find work in musical theatre. She starred in a 1960 Broadway revival of Finian’s Rainbow, where she met the man who would become her American husband, actor Biff McGuire. The pair worked frequently together, including starring in a touring production of Camelot in 1964 (Waters, p. 3). In the 1970s, the couple settled in the Seattle area where they become stalwarts of the local theatre scene for almost fifty years till McGuire’s recent passing in early-2021 (Seattle Rep 2021). As of the time of writing, Miss Carson is living in retirement in Seattle at the august age of 93. She has often been asked over the years about her memories of working with Julie and her standard reply is to boast with a smile that “I was Julie’s leading man!” (Holloway, p. A-7).

Nat Jackley as Widow Twankey (Panto Dame): Lanky and loose-limbed, Nat Jackley was a visual comic who found enormous success on the British music hall scene. Born into a show business family, Jackley started in his teens with the famous clog-dancing ‘Eight Lancashire Lads’, the same troupe that gave an early start to Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel (Dixon, p. 39). Jackley migrated into a series of comedy duos, first with his sister Joy and then with fellow comedian Jack Clifford, before going solo during the war. Billed as Nat ‘Rubber Neck’ Jackley, he developed a trademark blend of eccentric dancing, jerking neck movements, and an original funny walk described by one critic as “the strut of a demented turkey” (’Nat Jackley’, p. 35). At the height of his career, he topped the bill at the Palladium, appeared in three Royal Variety Performances, and made a successful tour of Australia. He also featured in a string of popular British films such as Demobbed (1944), Under New Management (1946), and Stars in Your Eyes (1956). With the demise of variety, Jackley moved into television and had a successful late career as a character actor in a diverse range of British TV shows. Another string to Jackley’s professional bow was as a legendary panto Dame and he appeared in a record fifty pantos between 1927 and his retirement in 1980 (ibid.). In Aladdin, he took on one of the most famous of all Dame roles, Widow Twankey, Aladdin’s comic-vain mother. Jackley passed in 1988, aged 79.

Walter Crisham as Abanazar: Though he is little remembered today, Crisham was a noted American actor of stage and screen who appeared in number of high profile productions. Born in Worcester, Mass. in 1908, he originally trained as a dancer and performed in several musical revues in the New York area during the 1920s. In 1933, Crisham travelled to London to appear in a dance revue called Ballyhoo and he ended up staying in the UK for almost twenty years (Short, pp. 88-89). Some of his more notable British stage successes included Cole Porter’s Nymph Errant (1933), opposite Gertrude Lawrence; the Ivor Novello musicals, Careless Rapture (1936) and Crest of the Wave (1937); several revues with favourite partner, Hermione Gingold, including Rise Above It (1941), Sweet and Low (1943) and Slings and Arrows (1948); and, with Jessie Matthews, Don’t Listen Ladies (1949). Throughout this period, Crisham made a number of films including several straight dramas such as They Met in the Dark (1943), No Orchids for Miss Blandish (1948) and Her Favourite Husband (1950). He scored his most famous film role in the small but flashy part of Valentin le Désossé in John Huston’s Moulin Rouge (1952). Though he had appeared in a West End holiday production of The Wizard of Oz in 1946, Aladdin would be Crisham’s first and only panto with one critic noting that “he makes his debut in pantomime with a zest implying that such has been his ambition all along” (Dent, p. 3). Crisham returned to the US permanently in the late-1950s, settling in the Los Angeles area. Other than a few minor TV appearances and some community theatre work, he seems to have entered semi-retirement. He passed in 1985 (‘Walter’, p. 54).

Martin Lawrence as The Emperor: A distinguished operatic bass who had forged a garlanded career in the opera houses of Europe, Lawrence might seem an unorthodox choice for a Christmas panto -- and, indeed, much was made in the press about his “history making” casting (’Concert Notes’, p. 6). His stature and booming voice was, however, a good fit for the magisterial role of the Emperor and, well versed in the comic traditions of opera buffa and Gilbert and Sullivan, Lawrence had “an ease in humorous acting” that meant “the transition from grave to gay in no way daunts him” (ibid.). Alongside his career in opera where, among other achievements, he created the role of Don Jerome in Gerhard's The Duenna, Lawrence was a strong proponent of traditional Jewish music. He made several recordings of Yiddish folk songs, wrote a number of studies on the history of Jewish music, and was, for many years, the musical director and choirmaster at the New London Synagogue till his death in 1983 at 73 years of age (‘Obituary’, p. 378).

Desmond and Marks as Bend Hi and Bend Lo: Fred Desmond and Jack Marks were dancers who met in the RAF during the war and, following ‘demob’, formed a comedy duo that lasted for decades (E.M.M., p. 2). With a 'knockabout’ comic act blending dance, pratfalls, and gags, ‘Desmond and Marks’ proved a very popular duo on the post-war variety circuit, extending to several international tours of Europe, Australia, and the US (’Variety News’, p. 3; ‘Light Entertainment’, p. 3). Like many variety acts of the era, they also found regular work in pantomimes, playing comic relief support characters and, on occasion, ‘skin’ roles including a fire-and-smoke-belching alligator (Frow, p. 179). In Aladdin, the pair performed the role of the classic -- if dubiously stereotyped -- Chinese policemen, Bend Hi and Bend Lo. Desmond and Marks performed in many other Littler pantos and could still be found doing Christmas shows into the 1980s (‘Christmas Greetings’, p. 40.).

Jimmy Clitheroe as Wishee Washee: A pint-sized comic actor who would find lasting fame on radio, Jimmy Clitheroe was one of the last of the popular tradition of music hall ‘midgets’. With his diminutive size, high-pitched voice, and musical Lancashire accent, Clitheroe developed a crowd-pleasing persona as a cheeky schoolboy with lots of sharp comments and double entrendres. In pantomimes, he would invariably play classic juvenile roles like Buttons, Tom Thumb, or, as here, Wishee Washee, Aladdin’s spoiled younger brother. Later in the decade, Clitheroe starred in his own hugely successful BBC radio series, The Clitheroe Kid that ran for 17 seasons till 1972 and spawned a parallel TV version in the 1960s (Elmes, pp. 203-7). Despite his success, Clitheroe remained his whole life in the family home, living with his mother. When his mother passed away in 1973, Clitheroe was inconsolable and, tragically, he was found dead from a suspected accidental overdose on the day of his mother’s funeral (Johnson, p. 12).

Carole Jeffries as Prince Pekoe: A 21-year-old honey-haired beauty, Jeffries was a relative newcomer in the Aladdin cast. She was a trained dancer who got an initial break as one of the burlesque troupe of ‘Windmill Girls’ at London’s Windmill Theatre (Storey, pp. 4-5). With ambitions for a career in musical theatre, Jeffries appeared in a few revues and provincial pantos, and even scored an early TV appearance (’She Gets’, p. 5). She had a small part in Littler’s 1950 panto at the Casino, Goody Two Shoes, and she must have impressed because he promoted her in Aladdin to the support ‘pants’ role of Prince Pekoe. The following Christmas, she was promoted yet again to principal girl in Dick Whittington at the Nottingham Theatre Royal. Thereafter, the available record on Jeffries grows dim. Reports state that she got married in 1953 (Stevenson 1953: p. 4), so she might have retired and/or changed her name.

David Davenport as Kazim: A versatile performer of many talents, Davenport had a distinguished career across dance, theatre, film. and television (Taylor, p. 36). He trained as a ballet dancer and performed with great success in the 1940s with several troupes including the New Russian Ballet, Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, and the New International Ballet. In the 50s he moved into musical comedy and pantomime, while retaining his interest in dance as a choreographer. He forged a successful career in film and television with credits ranging from comedies (he was in three Carry on films) to straight dramas such as The Darwin Adventure (1972). Tall and distinguished with an athletic build and a booming voice, Davenport was ideally cast in the magical genie role of Kazim, the Slave of the Lamp in Aladdin. Indeed, he would reprise the part in several later productions including a 1967 TV broadcast on ITV. Davenport passed in 1995 at the age of 74 (Taylor, p. 36).

Jacqueline St. Clere as Fairy Moonbeam: An English ballet dancer, Jacqueline St. Clere started her career in the late-40s with the London-based Metropolitan Ballet (Percival, p. 22). Aladdin marked her West End debut in the principal dance role of the Fairy Queen where she was showcased to strong effect in the show’s spectacular second act ballet. During the run of Aladdin, St. Clere married Frank Staff, the celebrated South African dancer and choreographer (‘Chit Chat’, p. 18). The following year, she was cast by Littler again as principal dancer in his 1952 Casino panto, Jack and Jill, in the role of the Fairy of the Well (‘Seven-and-a-half’, p. 3). In 1953, St. Clere accompanied her husband back to his native South Africa where she helped him establish the influential Frank Staff Ballet Studio (Rosen, p. 95). St. Clere continued to perform in several of Staff’s ballets, and branched out into teaching and costume design. She had a son with Staff but the marriage ended sometime in the late-1950s. It is not known what become of St. Clere after that, though records suggest she remained in South Africa (Rosen, p. ix).

Ross Harvey as the Aviary Keeper: One of several 'specialty’ acts integrated into Aladdin, Ross Harvey -- real name: Harry Rossofsky -- was an American vaudeville entertainer who found considerable success with his trained bird act. Billed as ‘Ross Harvey and his Dancing Parrot-Cuties’, the act consisted of Harvey doing soft shoe routines while the birds performed acrobatic tricks on his body and fingers in time with the music (Rasmussen, p. A14). In 1951, Harvey had a high profile run at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria which garnered a good deal of press attention. The exposure inspired Emile Littler to offer Harvey a novelty spot in Aladdin where he was billed as the Royal Aviary Keeper (‘Ross’, p. 1). His act was very well received and Harvey would return to the UK several times for other pantos and variety tours throughout the 1950s. He retired from show business in the 1960s and retrained as a cosmetologist, before passing in 2010 at the grand age of 90 (Rasmussen, p. A14).

Fiery Jack as Oriental Road Hog: Another speciality spot in the show was provided by Fiery Jack -- the stage name of Fred Zetina -- a well-known British clown who plied his trade in both circuses and music halls for many decades. Born into a theatrical family of acrobats, Zetina developed a novelty act built around a comical jalopy car that would shoot flames, smoke and fall apart, hence the name ‘Fiery Jack’. In Aladdin, he appeared as a motorist in one of the set scenes allowing him to perform his automative schtick. Zetina took his final bows in 1978 at the respectable age of 93 (Ashton, p. 4).

The Olanders as the Royal Tumblers: A further specialty act was provided by this troupe of young acrobats. A family of five young brothers from Denmark, the Olanders rose to prominence on the European circus scene in the 1940s before moving into the more stable and lucrative world of cabaret and variety. They undertook a successful tour of the UK in 1948, including a run at the London Palladium on a bill with Danny Kaye. They were contracted by Emile Litter to perform in his end-of-year panto, Jack and Jill at the Manchester Hippodrome where they impressed with their “exhilarating display of high speed somersaults” (M.M., p. 3). Thereafter, the Olanders became somewhat of a regular feature on the Littler panto circuit, appearing again in his 1949 staging of Jack and Jill at the Leeds Empire (A.T., p. 6) and the show’s 1950 reprise at the Coventry Hippodrome, co-produced by Littler and S.H. Newsome (’Accent’, p. 4). In 1951, the Olanders were afforded the ultimate honour of appearing in Littler’s London panto where they were billed as Royal Tumblers in the Court of the Emperor. By this stage, one of the original brothers had left the troupe and a young English adoptee was added (’Boy Acrobat’, p. 11). The Olanders have a special place in Julie lore as one of the boys, Fred, was an early crush for the 16-year-old star. In her memoirs (2008), Julie recalls him as “attractive, fit (obviously), and very gentle and dear” (p. 140).

The Tiller Girls (Dance Chorus): This famous precision dance troupe first formed by John Tiller in the 1890s became such a popular feature of British entertainment that Tiller schools were set up all over the country and multiple troupes of trained dancers sent to theatres far and wide (Reilly 2013). Renowned for their tightly synchronised routines and disciplined kick lines, Tiller Girls provided backing for principal performers as well as showcase displays of formation dancing during spectacle scenes. The troupe of Tiller Girls used for Aladdin consisted of 32 dancers under the tutelage of Phyllis Blakston, Littler’s resident choreographer.

The Terry Children (Juvenile Chorus): Like the Tiller Girls, the Terry Children was something of a British theatrical institution of the era. Juvenile choruses, or ‘babes’ as they were often known, were a core ingredient of pantomime dating from the Victorian era and there were several companies that emerged to meet market demand for trained child performers (Varty, pp. 138-147). ‘Terry’s Juveniles’ was one of the most successful. It was established in the late-1910s by an enterprising dance instructor who went by the name of ‘Miss Terry’, likely to cash in on the celebrated Terry theatrical dynasty. By the 1930s, Miss Terry had a plush office in Shaftesbury Avenue and several stage schools offering lessons and hopes of theatrical glory to the tiny tots and pushy stage parents of Britain (‘Baby Terry’, p. 7; ‘Terry’s Juveniles’, p. 14; ‘Terry Triumphs’, p. 11). Terry’s Juveniles was also the preferred source of panto babes for Emile Littler and he would regularly feature troupes of Terry Children dancing and singing their little hearts out in his shows. For Aladdin, Terry’s Juveniles provided a troupe of 24 ‘babes’ who coaxed collective oohs-and-aahs with their cute antics and what one critic termed “simple but effective ensembles” (Beaumont, p. 7). Though demand for its brand of hyper-trained child choruses was dwindling, Terry’s Juveniles continued into the 1960s before finally closing in 1968. Miss Terry passed in 1973 (‘Obituary’, p. 19)

With the cast in place, rehearsals for Aladdin started in mid-November at the London Casino. The Littler revue, Latin Quarter of 1951, was still playing till the end of the month so the cast performed in the rehearsal space before moving onto the stage proper in the first week of December. With a fixed holiday run of just a few months, pantos in this era didn’t usually hold previews. However, Aladdin did host a special ‘charity preview performance’ on Tuesday, 18 December, the day before its official opening, in aid of the King George’s Fund for Sailors with Lord and Lady Mountbatten in attendance (‘Events’, p. 13). Public performances of Aladdin started the following day on Wednesday 19 December.

Aladdin was the first of the big West End pantomimes to open for the 1951 season and it attracted a good deal of critical attention. For the most part, reviews were positive, even glowing, with particular praise for the principals, including Julie who was singled out for her glorious singing. Below is a sample of excerpts from reviews of Aladdin in some of the major publications:

The Times: “The pantomime season opens with a flash and a bang...Mr Emile Littler’s Aladdin admirably satisfies the requirements of this strange form...It provides a beautiful principal boy (Miss Jean Carson)...It gives us a fresh and unspoilt principal girl (Miss Julie Andrews) who can sing. It offers once again in Mr Nat Jackley a Dame who upholds the best comic traditions of a famous race” (‘London Casino’, p. 6).

Variety: “First of the West End pantomimes was Emile Littler’s London Casino production of Aladdin. His 11th London effort, this show...looks big with all the essential elements of a successful holiday show. Spaciously mounted and laced with ample comedy, Nat Jackley clicks as Widow Twankey and Jean Carson...makes a spirited boyish figure of Aladdin. Julie Andrews, 16-year-old, proves a delightful vocalist as the Princess” (’International’, p. 13).

Daily Telegraph: “Emile Littler’s Aladdin [is] one of the best shows of its kind for years. It has everything you want...: a glittering spectacle, good singing, a certain amount of dancing, just enough story, and plenty of rich fruity comedy...Julie Andrews, a very young Princess, is...impressive [with] the range of her singing...A first rate show” (Bishop, p. 3).

The Stage: “[T] his is uncommonly good entertainment -- the best...of ‘Emile Littler’s eleven London laughter pantomimes’. In Nat Jackley and Jean Carson it has a dame and principal boy of exceptional quality...Young Julie Andrews sings with almost operatic power and beauty” (’Christmas Shows’, p. 5).

The Sketch: “Aladdin, elaborate and pictorial,...chunners along blithely, thanks to Nat Jackley’s Dame, a contorted giraffe. And Julie Andrews has the best singing voice in the three main pantomimes” (Trewin, p. 55).

Daily Mail: “Emile Littler’s 11th London pantomime, gay without being gaudy,...is triumphantly British and pantomimic...Jean Carson is as jaunty and glamorous as a redheaded Aladdin as you could wish, and 16-year-old Julie Andrews, as the Princess, sings with a faintly puzzled air, as if sharing our surprise that such a powerful voice should emerge from such a petite throat” (Wilson, p. 5).

West London Observer: “Emile Littler’s eleventh annual pantomime, Aladdin (London Casino) seems rather like a rolling snow-ball to have got larger and larger during its passage through the years. The present panto has 15 spectacular scenes, irrelevant diversions -- clowning, acrobatics, and what-not -- not to mention Mr Littler’s own version of the Aladdin legend. This has Nat Jackley as Widow Twankey -- great fun in the best and broadest style -- and Jean Carson as a cute Aladdin...Julie Andrews and Martin Lawrence supply fine singing voices” (‘Spectacle’, p. 6).

Daily Worker: “Emile Littler’s production...really succeeds in telling an honest story tunefully, colourfully, cleanly and well...Nat Jackley of the rubber-neck made an extraordinarily attractive as well as funny Widow Twankey. The splendid singing of Martin Lawrence, Jean Carson, and Julie Andrews set a first-rate standard” (D.D., p. 3).

News Chronicle: “This, the first pantomime of the London season, is an affair of genuine gaiety and glitter...It has an unusually dainty Widow Twankey in Nat Jackley (who, moreover, has never been funnier), an unusually audible Aladdin in Jean Carson, [and] an unusually musical Princess in Julie Andrews” (Dent, p. 3).

The Sphere: “Mr Jackley as the Dame upholds the best comic traditions of pantomime, giving us a ludicrous parody of beauty with flashing eyes, raven hair and an air of roguishness. Julie Andrews, as the principal girl, is in excellent voice” (‘Aladdin and Humpty Dumpty’, p. 3).

Birmingham Gazette: “The stage gleams and sparkles in this production of Aladdin...Jean Carson is a gallant principal boy and Julie Andrews a strong-voiced principal girl” (‘London Letter’, p. 4).

Any Littler panto was assured of a popular reception but these excellent reviews helped make Aladdin a smash hit of the 1951 Christmas season. It played to packed houses right throughout its two-and-a-half month season closing on 23 February after 103 performances. Theatregoers who couldn't get tickets to the show weren’t left completely unsatisfied as excerpts from Aladdin were recorded and broadcast as a special half-hour radio programme on the BBC on January 3 1952 (‘Light Programme’, p. 33). It is not known if this recording is still in existence but what a treat it would be to hear it.

References:

‘Accent on Comedy in New Pantomime.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 10 October 1950: p. 4.

‘Aladdin and Humpty Dumpty: The lure of the pantomime.’ The Sphere. 5 January 1952: p. 3.

Andrews, Julie. Home: A memoir of my early years, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2008.

Ashton, Ellis. ‘Music Hall Miscellany.’ The Stage and Television Today. 1 June 1978: p. 4.

A.T. ‘Feast on Pantomime Opens in Leeds.’ The Yorkshire Post. 24 December 1949: p. 6.

‘Author! Author!’ The Sketch. 16 January 1952: p. 60.

‘Baby Terry.’ The Coventry Herald. 19 August 1932: p. 7.

Beaumont, Cyril. ‘Ballet in Pantomime.’ The Sunday Times. 30 December 1951: p. 7.

Bishop, George W. ‘Theatre Notes: West End plans for pantomime.’ Daily Telegraph and Morning Post. 29 October 1951: p. 6.

‘Boy Acrobat from Coventry, The.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 29 February 1952: p. 11.

Chang, Dongshin. Representing China on the Historical London Stage: From orientalism to intercultural performance. London: Routledge, 2015.

‘Chit Chat.’ The Stage. 3 January 1952: p. 18.

‘Christmas Greetings.’ The Stage and Television Today. 16 December 1982: p. 40.

‘Christmas Shows: Casino Aladdin.’ The Stage. 3 January 1952: p. 5.

‘Christmas Holiday Shows: The Casino Goody Two Shoes.’ The Stage. 29 December 1950: p. 5.

‘Concert Notes: Opera to pantomime.’ The Stage. 22 November 1951: p. 6.

D.D. ‘Vintage Year for Panto: Aladdin.’ Daily Worker. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

'Debroy Somers.’ The Stage. 29 May 1952: p.3.

Dent, Alan. ‘It’s Gay and Glittering.’ Daily News. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

Dixon, Stephen. ‘Nat Jackley: 100 funny walks.’ The Guardian. 21 September 1988: 39.

Elmes, Simon. Hello Again: Nine decades of radio voices. London: Random House, 2012.

‘Emile Littler Sends Greetings.’ The Stage. 20 December 1951: p.5.

Emile Littler Souvenir, The. London: Dewynters Ltd, 1953.

E.M.M. ‘Comedy Pair Great Fun.’ Derby Evening Telegraph. 31 August 1948: p.2.

‘Events from our Social Diary.’ The Sketch. 2 January 1952: pp. 12-13.

From, Gerald. Oh, Yes It Is: A history of pantomime. London: BBC, 1985.

Hainaux, René. Stage Design throughout the World since 1935. London: Harrap, 1965.

‘Hastings Mann’, The Stage. 14 May 1964: p, 3.

Hobson, Harold. "Christmas Shows." Sunday Times, 23 December 1951, p. 2.

Holloway, Tony. ‘Stage a Big Bouquet for “Cactus” Couple.’ The Pantagraph. 1 March 1969: p. A-7.

‘International: London Pre-Xmas Stage Prems Hit Best Since May; 'Crook' Looms Okay.’ Variety. 185 (3), 26 December 1951: p.13.

‘Jean Carson Makes TV History.’ The Stage. 10 March 1955: p. 11.

‘Jimmy Clitheroe.’ The Guardian. 7 June 7, 1973: p. 5.

Johnson, Gill. ‘Research reveals life of “Clitheroe Kid”.’ Lancashire Telegraph. 17 May 2007: p. 12.

Knox, Collie. ‘Candid Cameo: Emile Littler.’ The Sketch. 10 December 1947: p. 314.

Konig, George. ‘Prelude to Christmas: The panto factory.” The Sketch. 23 November 1949: p. 450-51.

‘Light Entertainment.’ The Stage and Television Today. 30 September 1976: p. 3.

‘Light Programme: Thursday 3 January.’ Radio Times. : p. 33.

Lloyd-Williams, Anne. ‘Physhe surprised the Americans.’ Birmingham Gazette. 24 January 1952: p. 4.

‘London Casino: Aladdin.’ The Times. 20 December 1951: p. 6.

‘London Letter: Littler and good.’ Birmingham Gazette. 21 December 1951: p. 4.

M.M. ‘Manchester Hippodrome: Jack and Jill.’ Manchester Evening News. 24 December 1948: p. 3.

‘Martin Lawrence.’ The Musical Times. 124: 1684, June 1983: p. 378.

‘Nat Jackley.’ The Stage and Television Today. 13 October 1988: p. 35.

News Chronicle Reporter. ‘Aladdin loses his hat.’ Daily News. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

‘Obituary: Miss Terry.’ The Stage.15 February 1973: p. 19.

Pedrick, Gale. ‘Emile Littler: Producer of two hundred pantomimes’, The Stage, 19 December 1957: p. 8.

Percival, John. ‘Backward Glances: The Metropolitan Ballet.’ Dance and Dancers. February 1960: pp.20-22

‘Principal Girl in Aladdin.’ Daily News. 15 December 1951: p. 5.

‘Provincial Pantomimes.’ The Stage. 31 December 1948: p. 8.

Rasmussen, Frederick N. ‘Harry R. Rosofsky dies at age 90.’ The Baltimore Sun. 11 September 2010: p. A14.

Reilly, Kara. ‘The Tiller Girls: Mass ornament and modern girl.’ In Theatre, Performance and Analogue Technology: Historical interfaces and intermedialities, K. Reilly, ed. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013: pp. 117-132.

Rosen, Gary. Frank Staff and his role in South African ballet and musical theatre from 1955 to 1959. Dissertation. University of Cape Town, 1998.

‘Ross and budgerigars arrive.’ Evening News. 7 December 1951: p. 1.

Seattle Rep. ‘Remembering Biff McGuire.’ SeattleRep.org. 1 April 2021 <https://www.seattlerep.org/about-us/inside-seattle-rep/remembering-biff-mcguire/>

‘Seven-and-a-half Pantos’. The Stage. 16 October 1952: p. 3.

‘She Gets TV Chance.’ Daily Herald. 9 July 1951: p. 5.

Short, Edgar. London Theatre, 1919-1949. London: Wiseman, 1983.

‘Spectacle Galore!’ The West London Observer. 28 December 1951: p. 6.

Stevenson, W.B. ‘Show Piece: Pre-London tryout for new show.’ Nottingham Journal. 18 February 1953: p. 4.

Storey, Basil. ‘The Windmill Tilted.’ Speedway Gazette. 4 December, 1948: pp. 4-5.

Taylor, Jeffrey. ‘Obituary: David Davenport.’ The Stage. 7 December 1995: p. 36.

‘Terry’s Juveniles.’ The Era. 30 March 1921: p. 14.

‘Terry Triumphs.’ The Era. 28 May 1930: p. 11.

‘Theatre Fare.’ The Courier and Advertiser. 24 December 1951: p. 3.

Trewin, J.C. ‘The Pantomimes.’ The Sketch. 16 January 1952: p. 55.

Tucker, David C. Lost Laughs of '50s and '60s Television: Thirty sitcoms that faded off screen. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2010.

‘Variety News: Desmond and Marks welcomed behind ‘that’ curtain.’ The Stage. 11 October 1956: p. 3.

Varty, Anne. Children and Theatre in Victorian Britain: ‘All work and no play.’ Houndsmill: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008.

‘Walter Crisham.’ Plays and Players. August 1985: p. 53.

Waters, Bill. ‘Forsooth! Here cometh Biff and Jeannie.’ Miami News Entertainment Section. 5 April 1964: p. 3.

Wearing, J.P. The London Stage 1950-1959: A calendar of productions, performers, and personnel. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Wilson, Albert Edward. Pantomime Pageant: A procession of harlequins, clowns, comedians, principal boys, pantomime-writers, producers and playgoers. London: S. Paul & Co, 1946.

Wilson, Cecil. ‘Aladdin Is Gay but Not Gaudy.’ Daily Mail. 20 December 1951: p. 5.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2021

#julie andrews#aladdin#pantomime#british theatre#emile littler#theatre#west end#london casino#1951#70th Anniversary

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sons Of The Silent Age. Part One.

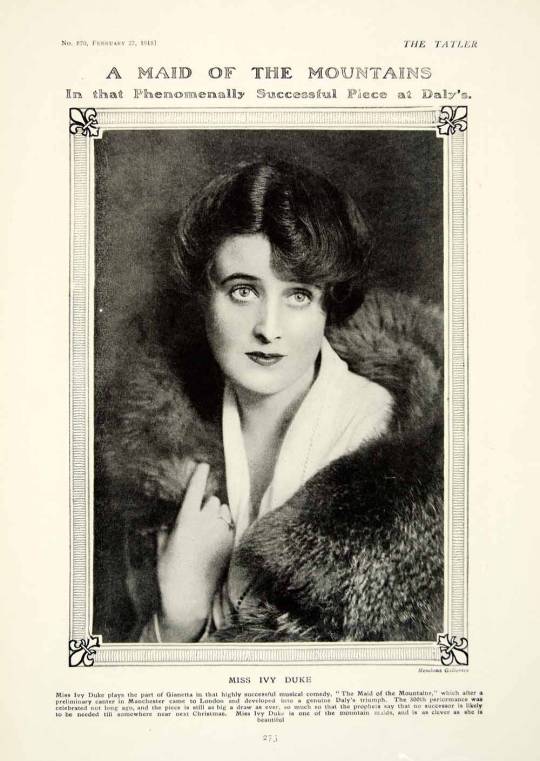

1) Ivy Duke (1896-1937) starred in the 1920 hit film The Lure of Crooning Water. She drank herself to death after her career took a downward turn.

2) Sybil Rhoda (1902-2005) starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s Downhill opposite Ivor Novello. Interviewed at age 101, she said "I'm amazed I've existed so long. I'm surprised about the whole thing. I can't get over it,"

3) Maurice Elvey (1887-1967) was one of the most prolific film directors in history, making nearly 200 films between 1913 and 1957. During the silent film era, he directed as many as 20 films per year. His adaptations of Sherlock Holmes were praised by Arthur Conan Doyle. In order to film the sinking of a troop ship, Elvey built a water tank in his own back garden, spending two months to fill it up via his kitchen tap.

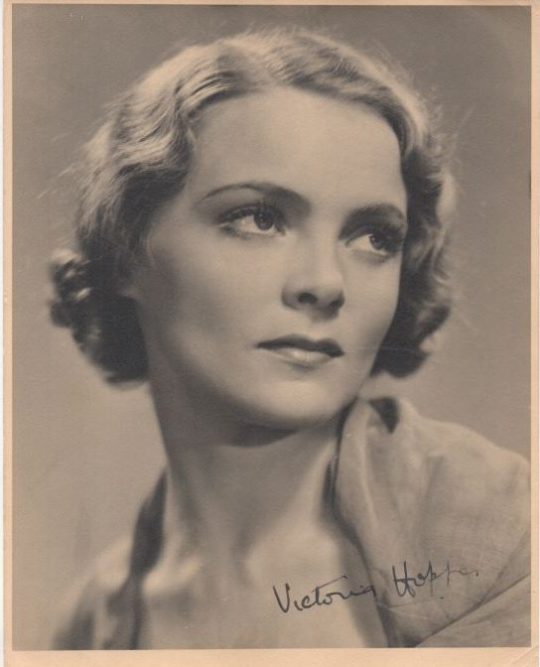

4) Victoria Hopper (1909–2007) was a British actress popular during the 1930s. From 1934 until 1939, she was married to film director Basil Dean, who grew interested in Hooper due to her resemblance to his former lover Meggie Albanesi (1899-1923). Dean cast her in several major films, which did badly at the box office.

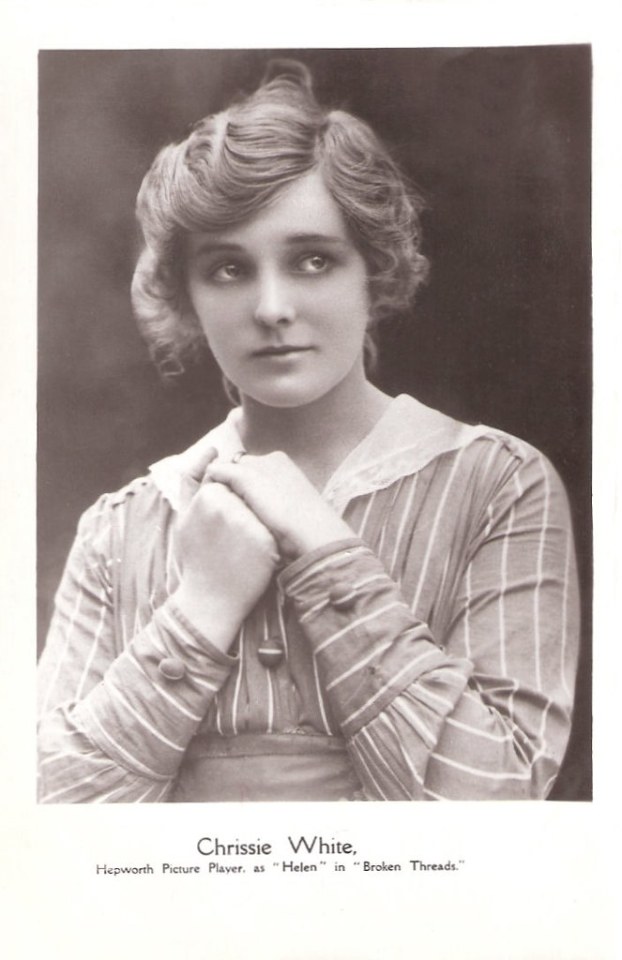

5) Chrissie White (1895-1989) appeared in more than 180 films. White married director Henry Edwards, and they became one of the most newsworthy celebrity couples of the 1920s. They had two children, and remained together until his death in 1952.

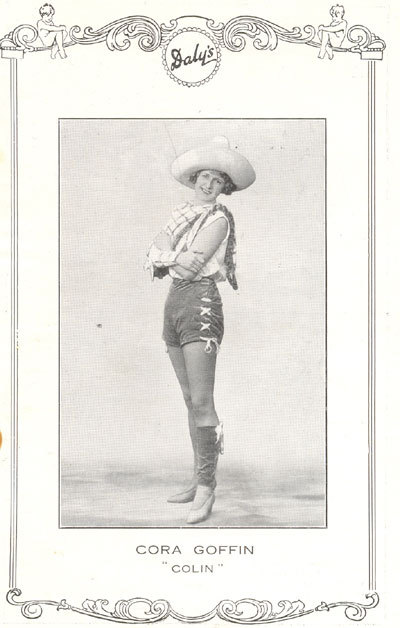

6) Cora Goffin (1902-2004) was an actress on the London stage. She acted in two silent films, during which she leapt from a moving horse and threw herself beneath a moving car in Paris. There were reports that she had her legs insured for £20,000 with Lloyd's of London. Goffin married theatre manager Emile Littler in 1933. She became Lady Littler when Emile was knighted in 1974

#shepperton babylon#sepia#1920s#1930s#cora goffin#chrissie white#victoria hopper#maurice elvey#sybil rhoda#ivy duke#vintage photography#matthew sweet#sherlock holmes#arthur conan doyle#alfred hitchcock#the lure of crooning water#old britain#ivor novello#david bowie#henry edwards

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backstories for my Sanders Sides Pets AU

Warnings: Mentions of Death, Mentions of Abuse, Mentions of Neglect, Mentions of Abandonment, Mentions of Selective Dog Breeding, i think that’s all but let me know if i should add any others.

Roman

Roman was Thomas’ first pet. Thomas adopted him from a pet shelter his friend, Joan visited to get food for their ferret, Elliot.

Roman was the only surviving puppy of the litter and was going to be euthanized since all his siblings were stillborn and his mother died during her childbirth. His mother was a show dog that was force-breeded to make ‘perfect puppies’ (sadly, the litter Roman was in was her first and only litter).

Joan saved him and took him home and made sure he was well taken care of and very much loved and cared for.

Joan was planning on keeping him at first but then Roman became aquainted with Thomas and Roman just wouldn’t let Thomas not take him home (aka wouldn’t let go). Talyn claims Roman imprinted on him since Thomas was holding him when Ro finally opened his eyes.

Patton

Patton was, at first, just being fostered by Thomas for a friend (Terrence) who moved to a new apartment that didn’t allow pets (Terrence only learned this after moving in because the complex owner didn’t care enough to tell him there were no pets allowed until he saw Terrence about to take Patt into the apartment when moving in).

Thomas later adopted him from Terrence when Terrence moved to Arizona where they were both worried if Patton would adapt well or not, so Thomas kept him.

Logan

Logan was a stray young cat from a littler of maine coon cats that a feral mother had.

Logan lived behind Thomas’ apartment complex. He took a liking to Thomas so Thomas took him in and gave him shelter. He later adopted him and Logan is a half-indoor/half-outdoor cat now, since Lo still loves the outdoors.

Virgil

Virgil’s mom was owned by a bad human who let her leave and come back whenever she wanted. His mother got surprise pregnant and the owner couldn’t tell. When she had Virgil, the mom, nor the mom’s owner wanted him, so the owner abandoned him outside.

Once he was outside, Virgil survived on his own for about a week before Logan found him and adopted him as his not-as-furry kitten.

Logan adopted him because he’s all black and Lo determined that this small black half fuzzy thing is a badly groomed cat that can apparently fly now. The flying did kind of confuse him but Logan’s committed so he’s just like ‘yeah, my kid flies, so be it as long as he’s in my sight so he doesn’t get lost’.

Thomas adopted Virgil to stay indoors to keep him protected and let him live as long as possible away from possible predators, since he was already abandoned by his mother.

Deceit (named Ethan)

Ethan was abandoned outside by his mother’s owner (a breeder who simply wanted certain typed of snakes) because he was born the wrong color (the breeder wanted albinos but the momma snake had lil super black pastel Dee).

Logan adopted him as his very not-so-furry kitten and took care of him.

Again, was easier for Lo to mistake him for a kitten since Ethan is all black just like Logan himself. Plus, at that point, Logan had a flying ‘kitten’ and could care less over having a slithery ‘kitten’ or not.

Thomas adopted Ethan when Logan brought him (and Virgil) to Thomas when Eth got sick with an upper respiratory infection and Logan knew Thomas would care for his not-so-fluffy kittens.

Thomas adopted him very shortly after Eth was back to being healthy.

Pets In The Future

He definitely plans to adopt something else but he has yet to fully adopt them.

He’s talked to a chameleon breeder and is planning to adopt one from the new clutch once they’re old enough to be adopted.

He’s also planning to adopt the baby bunny of a a friends’s two rabbits, once it’s big enough that Ethan won’t think it’s food (not that he would, Ethan is still tiny and only likes pinkies, but Thomas doesn’t want to chance it).

He is fostering/caring for two pets for friends. He’s fostering a sugar glider named Emile for Valerie while she is too busy to do so.

He’s taking care of a green iguana named Remy for his friend, Talyn, who had a housefire and Remy was left without somewhere to stay while Talyn stays with Joan (who’s complex owner won’t allow more than one pet in the apartments). Remy did have a few burns when Thomas got him but all are healed over now.

Taglist (I’m just gonna tag a couple who seemed to be interested in the AU in the previous two posts about it): @sirpuppetuniverse @lovesupportandcookies @just-another-rainbowblog @please-nope @dabookwormcat @stormy-sides

#sanders sides#sympathetic deceit#roman sanders#patton sanders#logan sanders#virgil sanders#deceit sanders#remy sanders#emile picani#thomas sanders#ts joan#ts terrence#ts elliot#tw death mention#tw abuse mention#tw neglect#tw abandonment#animal au#pets au#dog#cockatoo#cat#bat#snake#chameleon#bunny#sugar glider#green iguana#now you know why i changed dee's colors in the au

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

yknow what i want?

i have three ideas of what the finale will be

either (in order fr4om least fave to fave)

a four parter lore heavy omfgeveryonesdying angst fest including the orange side

a four parter where the orange side is proved to be emile, and the darks sides were just being lil shits, where littlerally everyone just gets therapy.

or my fave where

we still dont know the orsnge side. whats their purpose, whats their name??

idfk

what we do know is that they are pattons ex husband. maybe not canonically, but the vibes are THERE. there is some TENSION here.

and orage acts like pink. the singer. very

SO SO WHAT IM STILL A ROCKSTAR FUC K YOU PATTON HAHA

youknow 'try'

just becuase it burns doesnt ,ean your gonna die. youve gotta get up and try, try, try.

ye no jan may be the sassy wine aunt, and pat the 'oh, im the dad lol' but orange is THE mom. 'oh logans the mum' no. hes already said he doesnt like that idea. 'why do i have to be the mum'

orange sung LULABYS to beby virgy/ twins.

HES THE MUM

and hes so fokin sassy to his ex.

yknow fanon remus crazy/ riot? that but not in the 'just a lil creature' crazy more in a....

'fock you, fock this, ive dealt with too much shit from you guys, im lashing out. no, not agressively. but i will make you regret EVERYTHING. what? no, put that sword down. i meant im gonna be a lil sassy shit, im not gonna be a bitch, i KNOW bondaries. geez'

also, he is very emo/rock chick/punky

he makes virgil look like an uwu boy.

the boy has a spiky collar. and wrist cuffs.

he is unadbashedly himself, just bc thats what ppl didnt likre about him.

also, he taught virgil everything he knows about fashion/ makeup

1 note

·

View note

Text

Will's breaths were shaky as he rolled his hips into him, in and out, warm and slick and tight and perfect. A long whine pulled from his throat as Emile wrapped himself around him and he was pulled close, held down between his arms and his thighs. Every time Emile rocked down against him in return was heaven-- the only place he'd ever found it, buried deep inside the both of them for when they pulled so close together. He moaned out, those tears once again burning at his eyes. Not because of the past few days, but because he loved him. Oh, god, did he love him.

"Emile.." He whined into the kiss, his hips jerking as he tried to bury himself deeper into Emile, tried to give him every piece of himself he could possibly offer. The hands across his skin, searching or gripping at him, sent a shudder through him. "Oh, Emile!" He called out, a shaky hand reaching up to brush across his jaw. He laughed at the plea, squeezing his eyes shut just to take in the full feeling of him. Pressed against him, the both of them breathing hard and holding on to each other like there was nothing left in all the rest of the world. "Emile.. you know I- I'll- I'll give you anything," he managed, laughing again. He slipped his arm around his back just to hold him close, the other feeling over his waist as his hips started to pick up their pace, working a little faster, pushing a littler harder.

Will whimpered at the feeling it pulled over him, the sweet shocks each rock sent through his middle. "Emile- Emile!" He called, pressing his lips against the side of his face in a series of desperate, breathless kisses. His fingers dug into Emile's back as he rolled into him and he whined again. "Perfect," he whispered, kissing his cheek again. "God, you're- love- I love you!" Letting out a breath of a laugh, he pulled his hand from Emile's waist and reached between them, teasing him with a brush of his fingers along his cock. "Emile, darling, I've- I love you!"

Questions and Answers

He was going to go out again tonight. Will could tell from the moment Emile returned from the clinic, the way in which he didn't stop to rest in the pair of hours they had before sunset. He was preparing to leave again and continue hunting for.. whatever it was he was hunting for. Other vampires, Will supposed, but if that was the only criteria it felt.. blind. There had to be more to it, something he'd seen or heard, maybe something that had scared him.

He had to ask him about it. The not-knowing was going to just keep eating at him if he didn't, as was the worry, and it was starting to be unbearable. He didn't know what he'd do if Emile came home again with blood on his hands or a bullet in his chest.

Will's hands continued to work as he worried over it, idly tying together bags of tea on the kitchen counter for the next time they went to the farmer's market together. Preparing them had kept him busy for some time, able to keep his mind from spiraling too far while he had work to do, but soon enough he was tying the last bag closed. Will stood still for a long moment, staring down at the counter and wondering if he shouldn't just start the process all over again. It was better than stillness. It was better than waiting.

Sighing, he glanced outside. It would be dark soon and he'd be waiting anyway, unless he tried to speak to him now. He hesitated for another moment, then decided to go and find him.

@antiquedemon

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

TRICK OR TREAT

Mario glared at the crumpled invitation in his hand, then at the two begging brothers across from him. "No."

The two whined in unison, "But Maaaario we haven't been to a Halloween party sense we moved here!"

"We are not going to BOWSER'S Halloween party!" Mario recrumpled the invitation he had already thrice thrown away and shoved it into the littler brother's hand.

"But Mario think of all the desserts! Cake and candied apples!" Luigi tried to appeal to his brother's appetite, which usually worked.

"We can make those here, together."

"Think of the costumes! We could all match, like when we were little!" Emile attempted, uncrumpling the paper for the fourth time now.

"No. No absolutely not." Mario took the paper from Emile and shook it at him, "This? Is a trap. We're not going. Who even gave you this?"

"Devin. You like Devin. You two are practically the same person." Emile argued on his friend's behalf, leaning on Luigi to once again try their combined puppy eyes attack.

Mario returned is glare to the invitation, the handwriting was neat and in all caps, surrounded by crayon drawings of Halloween things like Bats and Pumpkins and what Mario assumed was meant to be a Skeleton, though it was probably Junior's first time drawing a human skeleton.

Mario looked again to his brothers, their big pleading eyes and quivering lips. They were already so powerful apart, together it was impossible to say no forever.

Mario sighed,

"Fine. Just an hour won't hurt.."

#Emile's Writing#In which Luigi and I pressure Mario to take us to Bowser's party because we are Halloween Fanatics#And the Mushroom Kingdom does NOT celebrate apparently (headcanon)#It probably isn't Halloween the exact same as it was back in Our World and it's probably not called the same thing#Buuuuuuuuut I would have done research on the Holiday actually mentioned on the invite#And just call it Halloween if it sounds similar enough#Peach also got an invite and she is of course going she always goes#She calls like the day before to ask Mario to be her plus 1 and honestly he would say yes instantly to her#We are his weakness but she is his obligation do you understand#He'll go anywhere she goes no question

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

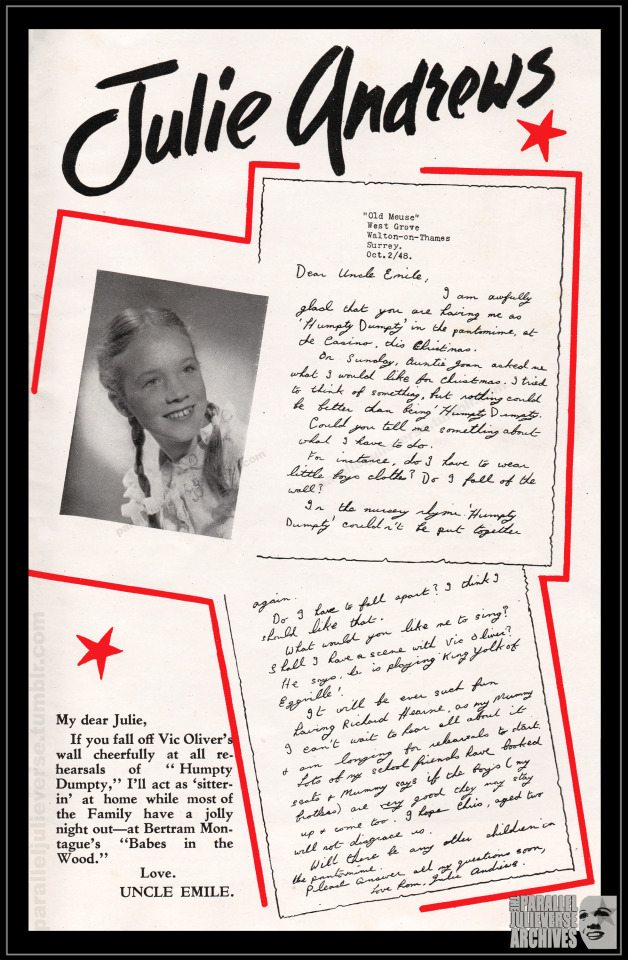

From the Archives: Dear Uncle Emile...

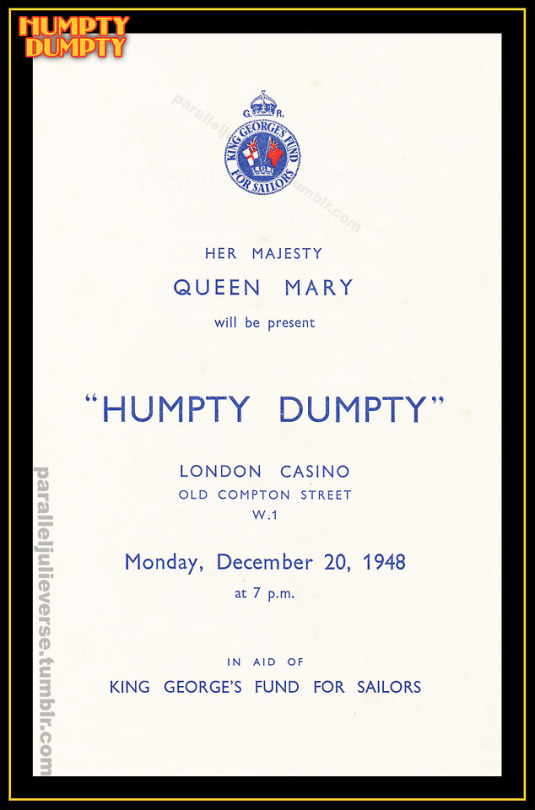

On October 2nd 1948, one day after her 13th birthday, Julie Andrews sat down at her family home in Surrey and penned a heartfelt letter of thanks to theatre impresario, Emile Littler. The influential magnate had just cast Julie as the juvenile lead in his big 1948 Christmas pantomime, Humpty Dumpty at the London Casino and the youngster was brimming with chirpy delight.

“I am awfully glad you are having me as ‘Humpty Dumpty’”, she writes, “On Sunday, Auntie Joan asked me what I would like for Christmas. I tried to think of something, but nothing could be better than being ‘Humpty Dumpty’” (Littler 1948, n.p.).

Granted, the letter was likely coaxed, if not coached, by Julie’s enterprising parents. And the fact it was reprinted a few weeks later in Littler’s annual Pantomime Pie publication, a seasonal showcase of his current and coming attractions, suggests it might even have been commissioned. Nevertheless, Julie’s guileless expressions of effusive gratitude were far from hollow sentiment.

Humpty Dumpty came at a critical juncture in the performer’s early career. Her star-making run in Starlight Roof was coming to a close and it was unclear what her next career step might be. Indeed, to hear Julie tell it, the pint-sized ‘prima donna in pigtails’ feared there might not even be a next step:

“Because of the County Council laws, I was only allowed to perform in Starlight Roof for one year, and that year flew by. On the day of my last performance, I was so choked with sadness, I could barely sing. The company gathered at the side of the stage and applauded and cheered...I remember rushing past them in floods of tears and sobbing my heart out in my dressing room. I honestly thought that was the end of my career, the end of all the fun, and I would never work again. I recognised, quite sensibly, that I might just be a flash in the pan” (Andrews, 87-88).

Enter Emile Littler to dry those tears. Popularly dubbed “King of the Pantomimes”, Littler was part of a theatrical dynasty that ruled the West End for decades (Pedrick, 8). Together with brother Prince and sister Blanche, the Littlers built up an empire of theatres that, by the mid-40s, accounted for over half the major houses nationwide (Elsom, 645). As Julie recalls:

“Emile and Prince Littler were impresario brothers who became the most powerful figures in the West End and the provinces, with a virtual monopoly on producing musicals and pantomimes throughout the country. Prince was by far the better known, having become chairman of Moss Empires in 1947, which encompassed the biggest theater circuit in England. If one booked a Moss Empires tour, it was considered an “A” tour” (Andrews 2008, 93).

Julie had already been semi-initiated into the Littler circuit with Starlight Roof which played at the London Hippodrome, the jewel in the crown of the Moss Empires chain. Her subsequent casting in Humpty Dumpty cemented what would become a long professional association with the Littlers. Possibly because he was more involved in the production side of affairs, Emile Littler became a particularly significant figure in Julie’s early years. The two would work again closely on the 1951 pantomime, Aladdin and, in 1958, Emile and his wife, Cora, served as official escorts to Julie when she was presented to the Queen at a Buckingham Palace Garden Party.

All of which makes it so charming that the 13-year-old Julie should have written such an affectionate letter to her “dear Uncle Emile...”

Sources:

Andrews, Julie. Home: A Memoir of My Early Years, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2008.

Elsom, John. ‘Littler, Prince (1901 - 1973) and Sir Emile Littler (1903 - 1985)’, The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, M. Barnham, ed., 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: p. 645.

Littler, Emile. Emile Littler’s Pantomime Pie, London: Findon, 1948.

Pedrick, Gale. ‘Emile Littler: Producer of Two Hundred Pantomimes’, The Stage, 19 December 1957: p. 8.

‘People’, Time and Tide, September 1976: pp. 4-5.

© 2020, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved.

#julie andrews#emile littler#pantomime#prince littler#british theatre#west end#London theatre#theatre history

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Postscript to our recent post in honour of the 70th Anniversary of Julie Andrews’s professional pantomime debut in Humpty Dumpty at the London Casino. Here is a rare shot of Julie and the cast meeting Queen Mary and the young Princess Alexandra at the special preview Royal Performance on 20 December 1948. The show folk seem happy, though not so sure about the “throne folk”!

Pictured, L to R, are: Vic Hyde, HRH Princess Alexandra (aged 12), Pat Kirkwood, Julie Andrews (aged 13), Vic Oliver, and Her Majesty Queen Mary.

#julie andrews#humpty dumpty#pantomime#london#west end#queen mary#princess alexandra#vic oliver#emile littler

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

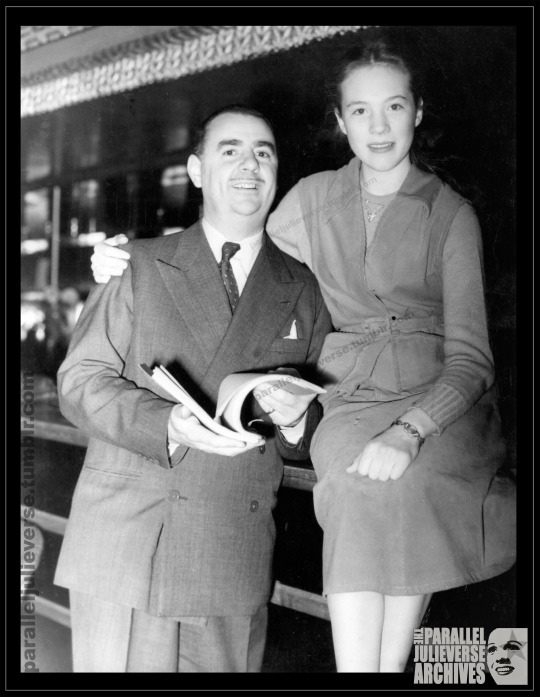

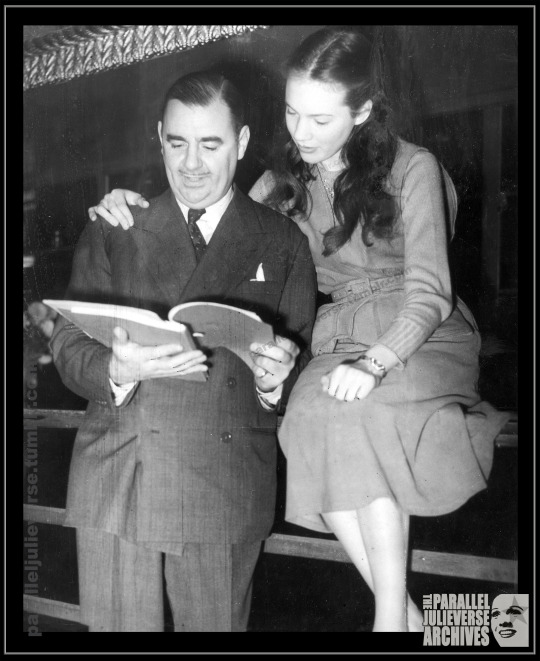

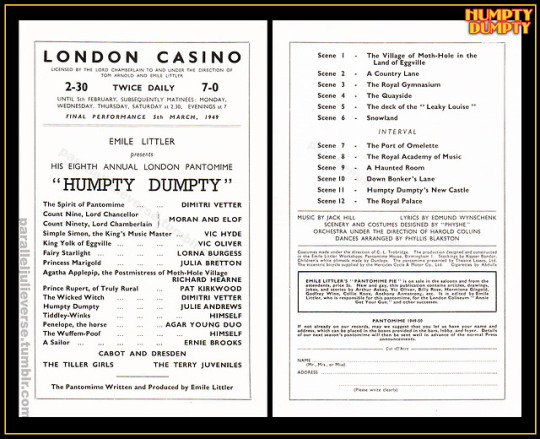

70th anniversary of Julie Andrews Christmas pantomime debut in Humpty Dumpty London Casino, 119 performances (21 December 1948 - 5 March 1949)

Seventy years ago this month, the young Julie Andrews realised another significant career milestone when she made her professional pantomime debut in Emile Littler’s all-star production of Humpty Dumpty. Blending music, dance and slapstick into a family variety entertainment, pantomimes, or ‘pantos’ as they are popularly known, are a longstanding British theatrical staple most popularly staged at Christmastime. And Emile Littler, part of a dynasty of theatrical impresarios that ruled the West End for decades across the mid-20th century, was the undisputed king of Christmas pantomime spectaculars (Hughes, 128).

Being cast in a Littler ‘panto’ was, thus, a major professional coup for the 13-year-old Julie Andrews who had not long come out of her acclaimed twelve-month stint in Starlight Roof. Cast alongside fellow Starlight Roof alumni, Vic Oliver and Pat Kirkwood, and other major UK stars of the era such as comedian Richard Hearne, Julie assumed the titular role of Humpty the Egg. As Julie recalls: