#el niño (ENSO)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A trio of physicists and oceanologists, two with the University of Cologne's Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology and the third with the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel, all in Germany, has found via the CESM1 climate model that an extreme El Niño tipping point could be reached in the coming decades under current emissions. The study by Tobias Bayr, Stephanie Fiedler and Joke Lübbecke is published in Geophysical Research Letters. The El Niño‐Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a climate phenomenon in which heat released in parts of the ocean into the atmosphere results in more rainfall in places like the western coast of North and South America and droughts in places like Canada and Africa. Over the past several years, weather watchers have noticed that ENSO events have become more extreme. Prior research has shown that such extreme events used to occur approximately eight or nine times per century. Some in the field have suggested that rising global temperatures could make them happen more often.

continue reading

#world#global warming#el niño (ENSO)#more extreme#more often#el niño tipping point#climate crisis#environment#carbon emissions

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I need to put this out here: I keep seeing people get all sad and defeatist about it not being snowy this season. There is an El niño right now. That is the second biggest effector on local climates globally.

What this means is that the trade winds have essentially disappeared, and increased convection over the ocean is changing air circulation patterns globally.

Scientists don't know what causes this but we have a few theories. We have noticed them getting more frequent due to climate change.

This has happened before. It's probably getting more frequent now, but there have been variations due to El niño years basically forever. This year is an anomaly, not the new norm. We do need to worry about climate change, but the situation is not as dire as this year would make it appear. The biggest thing we can all do is educate ourselves about how the climate works, and take action as a group as appropriate.

#a lack of snow is not proof of climate change any more than the presence of snow is proof that there isn't climate change.#evidence of climate change comes from years and years of data collected by many scientists#there will be a white Christmas again. they might be less common someday in the future. but there will be white Christmases.#weather varies within a region by quite a bit#and weather is not the same as climate#climate change#christmas#el niño#ENSO

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding La Niña: Unraveling Its Impact on (Global and) Indian Climate, Monsoon, Agriculture, and Weather Patterns in 2024

La Niña is a climate phenomenon that is part of the larger El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, which refers to the periodic fluctuations in sea surface temperatures and atmospheric conditions over the equatorial Pacific Ocean. La Niña is the opposite phase of El Niño and typically occurs every few years. Key Characteristics of La Niña: Cooler Sea Surface Temperatures: During La Niña,…

#2024 climate forecast#agriculture#Agriculture in India#Climate Change#Cyclone Activity#El Niño-Southern Oscillation#ENSO#Extreme Weather#Extreme Weather Events#Flooding in India#global climate#Indian Monsoon#Indian Winters#Kharif Crops#La Niña#weather patterns

0 notes

Text

Six Answers to Questions You’re Too Embarrassed to Ask about the Hottest Year on Record

You may have seen the news that 2023 was the hottest year in NASA’s record, continuing a trend of warming global temperatures. But have you ever wondered what in the world that actually means and how we know?

We talked to some of our climate scientists to get clarity on what a temperature record is, what happened in 2023, and what we can expect to happen in the future… so you don’t have to!

1. Why was 2023 the warmest year on record?

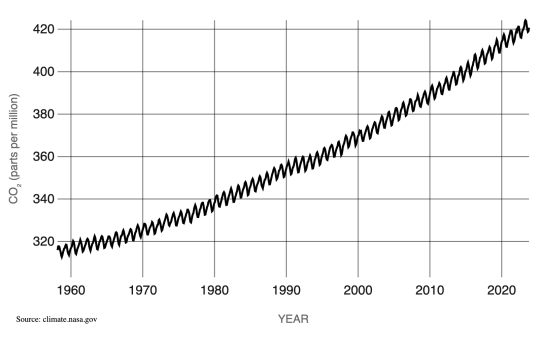

The short answer: Human activities. The release of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere trap more heat near Earth’s surface, raising global temperatures. This is responsible for the decades-long warming trend we’re living through.

But this year’s record wasn’t just because of human activities. The last few years, we’ve been experiencing the cooler phase of a natural pattern of Pacific Ocean temperatures called the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). This phase, known as La Niña, tends to cool temperatures slightly around the world. In mid-2023, we started to shift into the warmer phase, known as El Niño. The shift ENSO brought, combined with overall human-driven warming and other factors we’re continuing to study, pushed 2023 to a new record high temperature.

2. So will every year be a record now?

Almost certainly not. Although the overall trend in annual temperatures is warmer, there’s some year-to-year variation, like ENSO we mentioned above.

Think about Texas and Minnesota. On the whole, Texas is warmer than Minnesota. But some days, stormy weather could bring cooler temperatures to Texas while Minnesota is suffering through a local heat wave. On those days, the weather in Minnesota could be warmer than the weather in Texas. That doesn’t mean Minnesota is warmer than Texas overall; we’re just experiencing a little short-term variation.

Something similar happens with global annual temperatures. The globe will naturally shift back to La Niña in the next few years, bringing a slight cooling effect. Because of human carbon emissions, current La Niña years will be warmer than La Niña years were in the past, but they’ll likely still be cooler than current El Niño years.

3. What do we mean by “on record”?

Technically, NASA’s global temperature record starts in 1880. NASA didn’t exist back then, but temperature data were being collected by sailing ships, weather stations, and scientists in enough places around the world to reconstruct a global average temperature. We use those data and our modern techniques to calculate the average.

We start in 1880, because that’s when thermometers and other instruments became technologically advanced and widespread enough to reliably measure and calculate a global average. Today, we make those calculations based on millions of measurements taken from weather stations and Antarctic research stations on land, and ships and ocean buoys at sea. So, we can confidently say 2023 is the warmest year in the last century and a half.

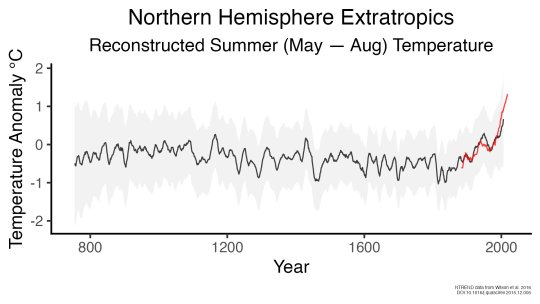

However, we actually have a really good idea of what global climate looked like for tens of thousands of years before 1880, relying on other, indirect ways of measuring temperature. We can look at tree rings or cores drilled from ice sheets to reconstruct Earth’s more ancient climate. These measurements affirm that current warming on Earth is happening at an unprecedented speed.

4. Why does a space agency keep a record of Earth’s temperature?

It’s literally our job! When NASA was formed in 1958, our original charter called for “the expansion of human knowledge of phenomena in the atmosphere and space.” Our very first space missions uncovered surprises about Earth, and we’ve been using the vantage point of space to study our home planet ever since. Right now, we have a fleet of more than 20 spacecraft monitoring Earth and its systems.

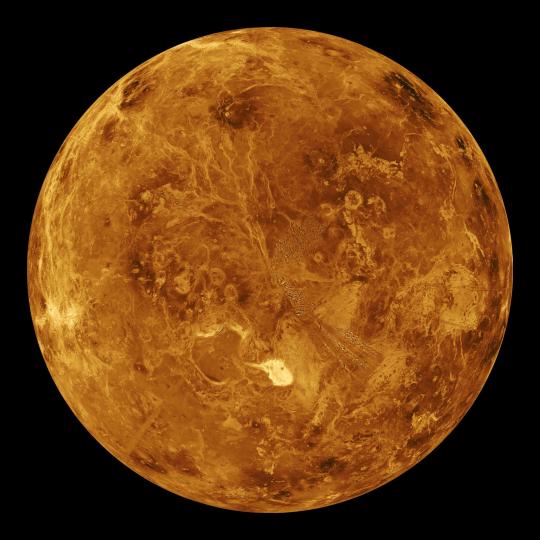

Why we created our specific surface temperature record – known as GISTEMP – actually starts about 25 million miles away on the planet Venus. In the 1960s and 70s, researchers discovered that a thick atmosphere of clouds and carbon dioxide was responsible for Venus’ scorchingly hot temperatures.

Dr. James Hansen was a scientist at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, studying Venus. He realized that the greenhouse effect cooking Venus’ surface could happen on Earth, too, especially as human activities were pumping carbon dioxide into our atmosphere.

He started creating computer models to see what would happen to Earth’s climate as more carbon dioxide entered the atmosphere. As he did, he needed a way to check his models – a record of temperatures at Earth’s surface over time, to see if the planet was indeed warming along with increased atmospheric carbon. It was, and is, and NASA’s temperature record was born.

5. If last year was record hot, why wasn’t it very hot where I live?

The temperature record is a global average, so not everywhere on Earth experienced record heat. Local differences in weather patterns can influence individual locations to be hotter or colder than the globe overall, but when we average it out, 2023 was the hottest year.

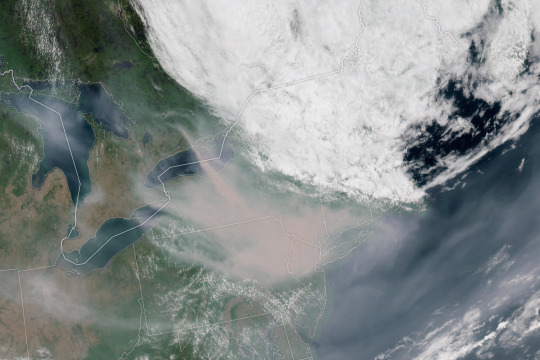

Just because you didn’t feel record heat this year, doesn’t mean you didn’t experience the effects of a warming climate. 2023 saw a busy Atlantic hurricane season, low Arctic sea ice, raging wildfires in Canada, heat waves in the U.S. and Australia, and more.

And these effects don’t stay in one place. For example, unusually hot and intense fires in Canada sent smoke swirling across the entire North American continent, triggering some of the worst air quality in decades in many American cities. Melting ice at Earth’s poles drives rising sea levels on coasts thousands of miles away.

6. Speaking of which, why is the Arctic – one of the coldest places on Earth – red on this temperature map?

Our global temperature record doesn’t actually track absolute temperatures. Instead, we track temperature anomalies, which are basically just deviations from the norm. Our baseline is an average of the temperatures from 1951-1980, and we compare how much Earth’s temperature has changed since then.

Why focus on anomalies, rather than absolutes? Let’s say you want to track if apples these days are generally larger, smaller, or the same size as they were 20 years ago. In other words, you want to track the change over time.

Apples grown in Florida are generally larger than apples grown in Alaska. Like, in real life, how Floridian temperatures are generally much higher than Alaskan temperatures. So how do you track the change in apple sizes from apples grown all over the world while still accounting for their different baseline weights?

By focusing on the difference within each area rather than the absolute weights. So in our map, the Arctic isn’t red because it’s hotter than Bermuda. It’s red because it’s gotten relatively much warmer than Bermuda has in the same time frame.

Want to learn more about climate change? Dig into the data at climate.nasa.gov.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

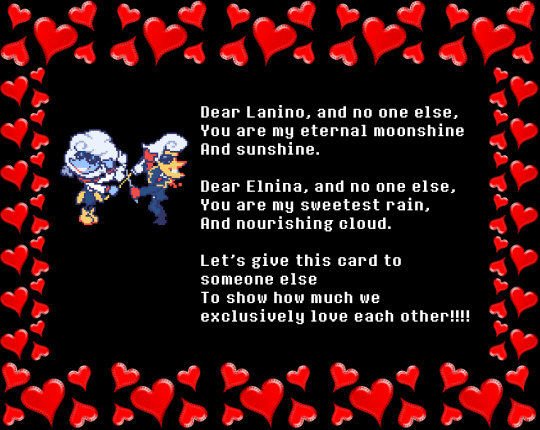

okay deltarune fandom! i haven’t posted to or gone through these tags in a while, but in light of recent events (me deciding to replay the games just in time for the newsletter), i have some things to share concerning our friends The Weather.

ID in alt text, and aforementioned “things to share” under the cut.

this message tells us some interesting information about the Weather. for those who don’t know, i believe the Weather were first introduced during the spamton sweepstakes under the link https://deltarune.com/weather/. the page functions similarly to lancer’s. despite having no information on these new characters—other than that they’ll probably appear in the next couple chapters, are called “The Weather,” and always stick together—the deltarune fandom immediately latched onto them, because that’s what we do.

and now, after the newsletter? we have names. do we know which name goes to which sprite….? not really. but there’s something interesting about what those names are.

when i first looked at the names Lanino and Elnina, one of my first thoughts was that they sounded gendered. in english and in romance languages, names ending in -o are often thought to be masculine, whereas names ending in -a are interpreted as feminine. not a common name convention in undertale and deltarune, where most names end in constants or “-ee” sounds, and obviously not an absolute rule — for example, chara is not feminine-presenting, but its name still ends in -a. still, many english-speakers, as well as speakers of romance languages and any other similar languages i’m not thinking of, will see “lanino” and “elnina” and assume masculinity and femininity respectively.

at this point, i was still thinking of romance languages because i’m autistic about words, and noticed that the endings of the names are very similar to the spanish words for boy and girl: niño and niña. then i noticed the beginnings of the names, “la” and “el,” are the spanish words for “the.” funny thing, though? “la” is feminine and “él” is masculine.

so… they’re mixing and matching gendered terms!!!? bigender weather real!!!!!! post over!!!!

…except it’s NOT over. put linguistics aside—it’s time for some environmental science.

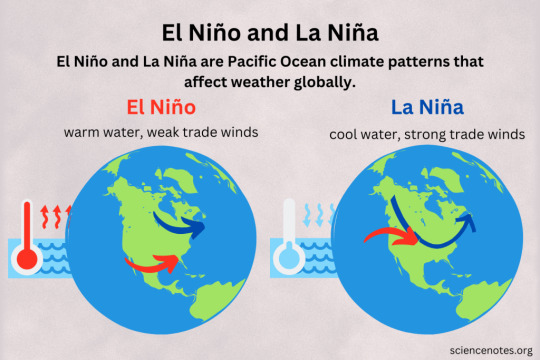

this graphic (which has an ID in alt text) is a lot of information, so i’m going to break it down: the earth experiences something called El Niño–Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. it’s a climate phenomenon that consists of two main phases: El Niño and La Niña. each one of these phases is a global event that can last years, and leads to changes in wind patterns, sea surface temperatures, and extreme weather events. it affects everything—how dry the land is in certain places, how many fish can be found in the ocean, etc.

to differentiate between the two, most simply: el niño is the warm phase, and la niña is the cooling phase.

why does this matter, you ask? because el niño and la niña climate events are largely inverse and opposites. that’s a simplification, but it does lend us some potential insight into the weather’s devoted and apparently monogamous relationship dynamic. or it would, if they hadn’t mixed up their names… but hey, that’s food for thought too!! could it be that the weather is so devoted to each other that they blended together? maybe that’s why their color palettes are the same—they balance each other out!

either way, i’m quite excited to do battle with them in the next year or so. they’re going to have such fun bullet patterns, i just know it… i hope they heal each other with photorealistic milk. or something weather-related, idk.

anyway. BIGENDER WEATHER REAL!!! post over!

#elnina#lanino#weather duo#deltarune#the weather deltarune#utdr#safe utdr#annoying dog#safeutdr#deltarune theory#the weather always sticks together#the weather always sticks together!#deltarune chapter 3#deltarune chapter 4#utdr newsletter#deltarune analysis#undertale newsletter#elnina and lanino#lanino and elnina#lanino deltarune#elnina deltarune#the weather#i had a beta so we don’t die like berdly

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

As many of you know, my blog(s) have a years long tradition of closely following the annual Atlantic Hurricane Season. I've slacked off in the last couple years but expect a return to day by day updates as I will be on a Caribbean island for the coming months. This hurricane season promises to be one of our craziest yet- it's barely July and the Atlantic has already yielded two storms, one of which (Hurricane Beryl) has already reached Category 5. All-time record sea surface temperatures, the latest El Niño Southern Oscillation, one of the hottest and strongest we've ever seen, weakening to a neutral phase, leaving extremely hot seas in the Main Development Area of the Atlantic Ocean. With the ENSO further shifting into La Niña, which has a stabilizing effect on the Atlantic atmosphere, neutralizing the wind shear generated by El Niño that impedes cyclone formation, we're looking at a vastly above average hurricane season. The average expected Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) for an Atlantic Hurricane Season is between 72 and 111 units, but this year estimates for total ACE put the season above 200 points in almost all estimates by various sources, with all predicting more named storms than the average 14. Some estimates are unprecedented: up to 33±6 named storms, with an overwhelming majority of forecasters expecting more than 5 major hurricanes this season. As trade winds continue to shift, and the monsoon trough deepens over western Africa in preparation for the rainy season, only time will tell how bad the 2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season will be, but it does not bode well. I will be watching the Inter-Tropical Convegence Zone closely. With that, it's my honor and privilege to introduce our coverage of the Atlantic Hurricane Season of the year 2024!

#hs2024

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

El Niño and climate change fuel Brazil floods

Catastrophic flooding in Brazil in April and May was a stark reminder of the compound effect of El Niño and climate change. Unprecedented rainfall led to devastating flooding across Rio Grande do Sul.

Record-breaking rainfall in the Rio Grande do Sul (RGDS) province of Brazil — equivalent to three normal months of rainfall in a two-week period — caused flooding over an area the size of the U.K. (Figure 1).

Two-week rainfall accumulations reached almost 1,000 millimeters in some parts of RGDS, and the state’s capital, Porto Alegre, registered 327 millimeters of rainfall in less than a week at the end of April (Figure 2).

The flooding has also been long-lasting, persisting for almost all of May with flood depths reaching 5 meters in some locations.[1] Economic losses are expected to exceed 22 billion Brazilian Reals (US $4 billion).

More than 580,000 residents were displaced,[2] over one-third of RGDS’s population lost access to running water,[3] hundreds of thousands were without power for weeks, and 170 fatalities were reported. The flooding also disrupted health services and infrastructure, and outbreaks of waterborne diseases, particularly leptospirosis, compounded the challenges faced by health authorities and emergency responders in the region.

Both the phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and climate change are thought to have contributed to the severity of the recent flooding.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#environmentalism#environmental justice#climate change#rio grande do sul floods 2024#image description in alt#mod nise da silveira

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

with the news of yet another la niña following one of the wettest el niños i've experienced, we have taken yet another step towards the breakdown of the enso and the return of the great primordial gondwanan rainforests and megalake systems in eastern australia

#it would be objectively be awful.#i mean the 2021-23 la niñas fucked everything up and that was only three years#an eternal la niña would kill a lot of people and eradicate entire ecosystems#not to mention the consequences of an eternal la niña for the eastern pacific#and you know. all the americas#but on an intellectual level. got dam it would be interesting

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from The Revelator:

In southern Brazil, especially the state of Rio Grande do Sul, severe flooding has caused an emergency being reported around the world. Human losses and homelessness there represent the biggest socioenvironmental catastrophe affecting the country.

One aspect that hasn’t yet garnered much media attention is the impact of these floods on rare and at-risk wildlife. For 11 years I worked on Marinheiros Island, situated on the estuary of Patos Lagoon in the heart of the now-flooded areas. On this island I identified the presence of three species of small vertebrates threatened with extinction, whose populations there are of great conservation importance.

Patos Lagoon is the most extensive lagoonal system in the world. Within this estuary Marinheiros is the largest island, covering an area of about 62 square kilometers (24 square miles).

Even before the current crisis, over the past few years, Marinheiros has experienced harsh flooding associated with massive rainfall. The floods are even more intense during El Niño phenomena, which produce heavy rain in southern Brazil. Three main factors there, together, result in the rapid rise of estuarine water levels and consequent flooding of the lagoon’s islands and marginal mainland:

The low elevations of marginal areas.

Heavy rains that increase the flow of rivers into the Patos Lagoon system and the subsequent discharge of water in the choked estuary.

Wind directions against the water flow from the estuary to the Atlantic Ocean, acting as a barrier for water discharging into the ocean.

The year 2023 saw a severe flood in Marinheiros Island and the marginal mainland of the Patos Lagoon estuary. This year has been even more calamitous. Flooding of 70% of the municipalities of Rio Grande do Sul — which includes the whole extension of the Patos Lagoon marginal zone — has, as of this writing, caused 149 people to lose their lives and forced more than 615,000 to leave their homes. Many of the more than 1,100 inhabitants of Marinheiros Island were rescued and sent to temporary shelters.

But rescuing the wildlife of Marinheiros Island has not become a priority. Three species deserve to be highlighted due to their very restricted distribution, habitat specificity, and conservation status.

A Toad, a Glass Snake and a Guinea Pig

The tiny red-bellied toad (Melanophryniscus dorsalis) — with a body length about 2 centimeters (just .78 inches) — can be considered a flagship species of Marinheiros Island.

The species’ existence on the island was only discovered in 2006, and it’s the southernmost known population of the species. Red-bellied toads are restricted to the coastal, marshy fields of the Brazilian states of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina and are considered threatened both regionally and nationally.

The estuarine glass snake (Ophiodes enso) was described only in 2017, and it is known from only three localities in the estuary of Patos Lagoon, one of which is Marinheiros Island. Like other reptiles commonly known as “glass snakes,” these animals are, in fact, legless lizards.

This species’ conservation status has not yet been officially evaluated by specialists at national and global levels. In the paper on the species description, however, Ophiodes enso is suggested as “critically endangered” given the small area of occurrence and the human-induced impacts on its habitats.

Finally, the greater guinea pig (Cavia magna) is a medium-sized rodent with a body length reaching 30 centimeters (about 1 foot). It lives on the borders of marshes and wet fields of a narrow coastal strip of Uruguay and southern Brazil’s Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina states.

The species is classified as “endangered” in Uruguay and “vulnerable” in Rio Grande do Sul. Importantly, greater guinea pigs from Marinheiros Island are genetically distinct from other populations in terms of the number of chromosomes (individuals from Marinheiros Island have 64 chromosomes, while mainland populations have 62).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2023, the relentless increase in global heating will continue, bringing ever more disruptive weather that is the signature calling card of accelerating climate breakdown.

According to NASA, 2022 was one of the hottest years ever recorded on Earth. This is extraordinary, because the recurrent climate pattern across the tropical Pacific—known as ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation)—was in its cool phase. During this phase, called La Niña, the waters of the equatorial Pacific are noticeably cooler than normal, which influences weather patterns around the world.

One consequence of La Niña is that it helps keep a lid on global temperatures. This means that—despite the recent widespread heat waves, wildfires and droughts—we have actually been spared the worst. The scary thing is that this La Niña will end and eventually transition into the better-known El Niño, which sees the waters of the equatorial Pacific becoming much warmer. When it does, the extreme weather that has rampaged across our planet in 2021 and 2022 will pale into insignificance.

Current forecasts suggest that La Niña will continue into early 2023, making it—fortuitously for us—one of the longest on record (it began in Spring 2020). Then, the equatorial Pacific will begin to warm again. Whether or not it becomes hot enough for a fully fledged El Niño to develop, 2023 has a very good chance—without the cooling influence of La Niña—of being the hottest year on record.

A global average temperature rise of 1.5°C is widely regarded as marking a guardrail beyond which climate breakdown becomes dangerous. Above this figure, our once-stable climate will begin to collapse in earnest, becoming all-pervasive, affecting everyone, and insinuating itself into every aspect of our lives. In 2021, the figure (compared to the 1850–1900 average) was 1.2°C, while in 2019—before the development of the latest La Niña—it was a worryingly high 1.36°C. As the heat builds again in 2023, it is perfectly possible that we will touch or even exceed 1.5°C for the first time.

But what will this mean exactly? I wouldn't be at all surprised to see the record for the highest recorded temperature—currently 54.4°C (129.9°F) in California's Death Valley—shattered. This could well happen somewhere in the Middle East or South Asia, where temperatures could climb above 55°C. The heat could exceed the blistering 40°C mark again in the UK, and for the first time, top 50°C in parts of Europe.

Inevitably, higher temperatures will mean that severe drought will continue to be the order of the day, slashing crop yields in many parts of the world. In 2022, extreme weather resulted in reduced harvests in China, India, South America, and Europe, increasing food insecurity. Stocks are likely to be lower than normal going into 2023, so another round of poor harvests could be devastating. Resulting food shortages in most countries could drive civil unrest, while rising prices in developed countries will continue to stoke inflation and the cost-of-living crisis.

One of the worst-affected regions will be the Southwest United States. Here, the longest drought in at least 1,200 years has persisted for 22 years so far, reducing the level of Lake Mead on the Colorado River so much that power generation capacity at the Hoover Dam has fallen by almost half. Upstream, the Glen Canyon Dam, on the rapidly shrinking Lake Powell, is forecast to stop generating power in 2023 if the drought continues. The Hoover Dam could follow suit in 2024. Together, these lakes and dams provide water and power for millions of people in seven states, including California. The breakdown of this supply would be catastrophic for agriculture, industry, and populations right across the region.

La Niña tends to limit hurricane development in the Atlantic, so as it begins to fade, hurricane activity can be expected to pick up. The higher global temperatures expected in 2023 could see extreme heating of the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico surface waters. This would favor the formation and persistence of super-hurricanes, powering winds and storm surges capable of wiping out a major US city, should they strike land. Direct hits, rather than a glancing blow, are rare—the closest in recent decades being Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which made landfall immediately south of Miami, obliterating more than 60,000 homes and damaging 125,000 more. Hurricanes today are both more powerful and wetter, so that the consequences of a city getting in the way of a superstorm in 2023 would likely be cataclysmic.

#we're going to hit 1.5C...#El Niño will probably take us a little above 1.5C...#I think the Southwest will need to be evacuated... the problem there is so much worse than the states are letting on#they've been lying to their citizens... not informing them of the full danger#cc

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is now forecasting a moderate-to-strong El Niño season to continue through February 2024. The forecast itself mostly piques the interests of meteorologists, oceanographers, fishers, and the global network of food commodity traders and crop insurers whose fortunes live and die in the technical arcana of the weather report.

But this forecast has vast implications: Even a typical El Niño can reduce harvests for important crops, increase the disease burden, hammer developing and middle-income countries’ economic prospects, increase armed conflict risk in the tropics, and fuel maritime conflict and territorial ambitions in the East and South China Seas.

Some of these challenges—such as civil wars and maritime conflict in the South China Sea—would manifest as immediate, hurricane-like clear and present dangers. But many would not. Like climate change, perhaps the greater danger lays in the accumulation of thousands of small cracks in the global food, public health, and other systems that are the bedrock of life.

Most of these hazards will hit hardest in countries that are ill-equipped for the economic and political fallout. They add urgency to easing developing and middle-income countries’ debt burdens and building more resilience into the global food system. For the United States, they highlight the need to adopt a more comprehensive strategy for defining national security threats and government responses to them.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a cyclic pattern of warming and cooling in the waters of the east-central Pacific Ocean. ENSO oscillates between cool (La Niña) and warm (El Niño) phases at intervals averaging five to seven years. Climate change is giving ENSO a “push,” making the swings back and forth deeper and potentially longer lasting. The currently forming El Niño follows a rare “triple dip” La Niña that ended in June lasted nearly three years—the longest in over 50 years.

But what happens in the east-central Pacific doesn’t stay there. As Jet Propulsion Laboratory scientist Josh Willis has said, “When the Pacific speaks, the whole world listens.” ENSO is the single most important driver of year-to-year variation in global climate. ENSO’s teleconnections—links between weather phenomena separated by vast distances—shape weather across the southern United States, Africa, Latin America, and closer to “home” in Southeast Asia and Oceania. They cause or strengthen droughts as well as extreme rainfall events and affect temperature and humidity levels over much of the world.

Both El Niños and La Niñas cause weather-related hazards. The crushing three-year drought that’s been devastating the Horn of Africa since October 2020? It’s partly a result of that triple-dip La Niña. South America’s severe drought, gripping many of the world’s most significant grain exporters? ENSO’s effect is there, too. Ditto for drought in the U.S. south and southwest. The transition to an El Niño will likely bring some relief to these areas, though that “relief” has come to the Horn in the form of torrential rains and flooding that burst the banks of the Juba and Shabelle rivers and forced 300,000 Ethiopians and Somalis from their homes. This whipsawing between extremes is the “push” climate change is providing.

But more broadly, the effects aren’t symmetrical. Shifting from La Niña to El Niño conditions doesn’t just redistribute good and bad weather around the globe. El Niños come with much more downside risks to global food supplies, public health, economic recovery in the global south, as well as to peace and stability – in the Global South where its impacts are most acute, but also in East Asia.

Let’s start with food. Though global food prices are down a bit from record highs following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, they are still among the highest prices seen in the last 60 years. And these prices don’t yet fully reflect the effect of Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative and attacks on Ukrainian export infrastructure, both of which further weaponize Russia’s role in food markets and have led prices to begin creeping back up at a time when more than 250 million people are experiencing acute food insecurity.

Some qualified good news: In the past, El Niños haven’t caused global food prices to spike, with price effects being relatively modest. A multinational team of scientists found both El Niños and La Niñas suppress global yields for maize, rice, and wheat, with the effects of El Niño particularly strong for maize. On average, El Niños slightly reduce global food supply, though the effects are typically modest and can be offset by planting more acreage to offset lower productivity.

But at the country or regional level, as in western and southern Africa, the effects can be quite strong, sending local prices higher and increasing rural unemployment. El Niño effects for food production aren’t confined to land, either. The warming of the West-Central Pacific suppresses catches for important fisheries like the Peruvian anchoveta—the world’s most productive fishery—and in heavily fished areas like the East and South China Seas.

The effects of weather-related crop failures on food markets operate on two levels. First, they constrict actual supply in a market where demand is both constantly growing and price-inelastic: The prevailing price doesn’t change biological necessities. Second, they shape current expectations about future production and thus hedging behavior. Expecting a bad harvest, buyers with the means and the foresight—like China—may begin stockpiling grains in anticipation of failed harvests or potential market disruptions.

In the past, these activities have only had modest effects on prices. Yet this time may be different. These hedging strategies are now being implemented in the context of rising economic nationalism in which governments—especially authoritarian ones—are resorting to export bans to address concerns about domestic food shortages and explicitly weaponizing food trade; that is, they are occurring in markets that are more risky than in the recent past. This could be bad news for a global food security picture already hammered by the Ukraine war and the lingering effects of coronavirus-related supply chain disruptions.

Speaking of the coronavirus: A strong El Niño could increase the infectious disease burden. Analyzing the strong El Niño of 2014 to 2015, researchers found increases in cases of plague in Colorado and New Mexico, cholera in Tanzania, and dengue fever in Brazil and Southeast Asia. In the U.S. southwest and Tanzania, the culprit was wetter-than-normal conditions that increased the abundance of plague-carrying fleas and overwhelmed drainage and sanitation systems, causing drinking water to become contaminated with cholera. In Brazil and Southeast Asia, higher temperatures and droughts had a more complicated impact: Bereft of standing water in the natural environment, mosquitos penetrated further and in larger numbers into urban areas with open water sources, then matured more rapidly—and developed more voracious appetites, thus infecting more people.

At the macro scale, the economic losses from El Niños can be significant. Failed crops are foregone income that drive up demand for imports. Burst riverbanks and dams must be repaired and often come with considerable damage to infrastructure such as roads and electricity grids, which are critical for the normal functioning of the economy.

But that’s just a fraction of the story. A recent article in Science by Christopher Callahan and Justin Mankin attributes massive economic losses to the persistent negative effects of El Niños on growth, estimating total global losses of $5.7 trillion from the 1997 to 1998 El Niño.

That’s an enormous number. But it’s not as if the world lost nearly a sixth of total economic output in 1998 (world GDP was roughly $31.5 trillion at the time). Many of those effects emerged in the years after the event due to the compounding effects of forgone growth investment—the same reason money saved now is worth more than money saved later—and the high costs of building back after associated natural disasters such as floods and mudslides. And because we never “see” foregone growth due to lack of investment or diversion of resources from building new schools to repairing roads, we don’t typically think of these losses when counting up the economic consequences of natural disasters. It’s an example of how many of the costs of climate-related events are almost imperceptible in the moment but add up to real (and large) numbers.

The estimates reported in the Science article are orders of magnitude above previous ones of El Niño–associated economic losses. While some economists have questioned the astounding size of these estimates, even losses in parts of Africa and countries where the historic relationship between El Niños and GDP growth is strongest—such as Peru, Ghana, and Indonesia—could still wind up being in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

El Niño’s effects for economic growth and food supplies help us understand one of its other consequences: elevated risk of civil conflict. Over a decade ago, Solomon Hsiang, Kyle Meng, and Mark Cane found that civil conflicts—armed conflicts between rebels and governments—were more than twice as likely to break out during El Niños relative to La Niñas in world regions whose local climate is affected by ENSO teleconnections, with conflict outbreaks clustering between July and November. In doing so, their study was the first to link climate at the global scale with armed conflict, a topic that is now the subject of exhaustive study and discussion.

When studying climate impacts on conflict, researchers almost never find a smoking gun. To date, no rebel leader has cited El Niño as their rallying cause. Rather, what researchers find is that climatic factors “load the dice,” making conflict marginally likelier to occur. Again, the impact is hard to detect in any given conflict but emerges from analyzing hundreds if not thousands of conflict events over time.

El Niño’s adverse consequences for fisheries also increase the risk of militarized conflict on the seas. Of particular concern are its effects in the East and South China Seas, where the impact on fish populations is strong, fishing pressure is high, and the regions’ major fishing nations—China, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan among them—have tense security relationships in the best of times. While it’s extremely unlikely a Taiwan invasion would begin over a fisheries dispute, these types of militarized conflicts are one of the few scenarios in international affairs where the coast guards and navies of rival countries may come into conflict over the actions of third parties—such as fishing vessels crossing disputed maritime boundaries—that they do not command or control.

Facing these potential outcomes, what can be done? Countries with strong ENSO teleconnections—which are mostly developing and middle-income—need resources and budgetary space to address problems such as rising food import bills, disaster preparedness and relief, and adequate provisioning for their security forces.

For this reason, creditor countries—especially China and those in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—need to address the large debt overhangs many of these countries accumulated during the coronavirus pandemic. Ghana’s $3 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund is a signal that creditor countries, including China, can work together to address these challenges.

Consistent with the increasing role armed forces are playing in disaster response and relief, countries such as the United States may be called upon to provide more emergency services that leverage their considerable airlift capacity and ability to move medical supplies and emergency food aid in difficult circumstances.

Stepping back from immediate responses, a bigger picture take-home point emerges for the U.S. government. The evidence of strong, adverse health, economic, and security consequences has made clear that the conventional approaches to defining national security interests and threats are lacking. Climate impacts—El Niños among them—are security impacts, but identifying and responding to them shouldn’t be the exclusive domain of national security and intelligence agencies like the Department of Defense and National Security Council. The Biden administration has done more to mainstream climate security than any of its predecessors—but there is far more work to be done.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

TELL ME MORE OCEAN FACTS BOSS

- superfan anon sprayed by spritz bottle AOOOOUUUUUUCHHH MT EYEEE

You may have heard people discuss El Niño, the weather event— but do you know why it happens? Called El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), it's a climatic phenomenon related to sea temperature in the tropical stretch of the Pacific. The Southern Oscillation part refers to the atmospheric changes that radiate out from this.

El Niño means the sea surface is warm; the rains are pushed into a low pressure zone between Indonesia and South America. In contrast, La Niña is cold, and Indonesia gets dumped on.

This shift in atmospheric pressure and conditions has effects over much of the world. Here's some maps:

A neutral pattern is somewhere between the two, but honestly kind of weighted towards La Niña.

We are currently in a pretty strong El Niño condition, and it's expected to continue for a while. It usually cycles every 2-7 years.

Because this has such strong climactic effects, it's really important for agriculture and fisheries; dooming or booning you, depending on where you live and whether its strong or weak, Niño or Niña.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coral reefs in peril from record-breaking ocean heat - Technology Org

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/coral-reefs-in-peril-from-record-breaking-ocean-heat-technology-org/

Coral reefs in peril from record-breaking ocean heat - Technology Org

Record breaking marine heatwaves will cause devastating mass coral bleaching worldwide in the next few years, according to a University of Queensland coral reef scientist.

Corals – illustrative photo. Image credit: Pixabay (Free Pixabay license)

The alarming finding is the result of an international study led by UQ’s Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg of UQ’s School of the Environment, who is currently attending the COP28 climate change meetings in Dubai.

“We were shocked to find heat stress conditions started as much as 12 weeks ahead of previously recorded peaks and were sustained for much longer in the eastern tropical Pacific and wider Caribbean,” Professor Hoegh-Guldberg said.

“Historical data suggests the current marine heatwaves will likely be the precursor to a global mass coral bleaching and mortality event over the next 12 to 24 months, as the El Niño phase of El Niño-Southern Oscillation or ENSO continues.

“Across July 2023, Earth experienced its warmest days on record since 1910, as well as the warmest month ever recorded for sea surface temperatures.

“This puts immense pressure on vital but fragile tropical ecosystems, such as coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass meadows.

“For example, a coral reef in the Florida Keys called Newfound Harbor Key accumulated heat stress almost 3 times the previous record and it occurred 6 weeks ahead of previous peaks.”

Professor Hoegh-Guldberg said the findings come at a critical point in protecting global biodiversity, with commitment to climate change mitigation slipping in many nations.

“The latest environmental information indicates that we’re well off-track when it comes to keeping global surface temperatures from reaching a very dangerous condition by mid to late this century,” he said.

“Frankly, we’re hurtling in the opposite direction.

“Compounding this is the fact these devastating impacts appear to be rolling into a vast record-breaking global event.”

Professor Hoegh-Guldberg said that without serious and swift action, the persistence of coral reefs beyond the next few decades is in serious jeopardy.

“Our study shows that ENSO is a major determinant of the fate of the world’s coral reefs,” he said.

“Rising sea temperatures, coupled with other stressors such as ocean acidification and pollution, have severely weakened their resilience.

“This puts coral reefs and a quarter of the ocean’s biodiversity at serious risk of annihilation.”

Professor Hoegh-Guldberg said efforts to introduce of heat-tolerance genes into the natural coral population have shown promise, but the reality of scaling these efforts remains logistically challenging.

“Given the complex and interconnected nature of marine ecosystems such as coral reefs, a comprehensive approach is necessary for mitigating the impacts of changing oceanic conditions,” he said.

“The importance of reducing our emissions is underscored in our findings, where massive changes to oceanic warming are set to destroy coral reefs and many other ecosystems.

“With this in mind, there are extremely tough discussions underway at the COP28 climate meetings.”

This research is published in Science.

Source: The University of Queensland

You can offer your link to a page which is relevant to the topic of this post.

#2023#approach#biodiversity#Biology news#change#climate#Climate & weather news#climate change#comprehensive#coral bleaching#coral reef#coral reefs#corals#data#direction#earth#Ecosystems#el niño#Emissions#Environment#Environmental#Experienced#genes#Geoscience & Environment news#Global#Heat#Impacts#it#LED#Link

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 / 20

Aperçu of the Week:

"Music is a language in which you can't lie."

(Hubert von Goisern, Austrian singer-songwriter and founder of alpine rock)

Bad News of the Week:

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is upon us again. This weather phenomenon of the equatorial Pacific happens at irregular intervals of two to eight years and refers to the occurrence of unusual, non-cyclical, altered ocean currents in the oceanographic-meteorological system. Without going into detail about Walker cells, trade winds and surface waters, let's just say that the weather between South America and Southeast Asia is tipping. With worldwide effects.

Plankton dies en masse and leads to the collapse of entire food chains, e.g. there are no more fish off Peru, seabirds die in the entire Pacific. Unnaturally heavy rainfall on the western side of the Andes causes landslides and flooding. In Southeast Asia and Australia, the lack of rain causes huge bush and forest fires, and the Amazon region and southern Africa dry out. Huge hurricanes develop in Mexico, the monsoon intensifies in India, and coral bleaching increases significantly worldwide. Everywhere it becomes noticeably warmer.

El Niño has already been documented by the pre-Columbian Incas and is even believed to have led to the extinction of the Moche civilization. It is therefore a natural phenomenon for which, for once, humans are not to blame. However, since man-made climate disasters such as floods, hurricanes and forest fires have increased dramatically in recent years, more than a few experts expect a reciprocal amplification that could be devastating due to its cascading effect. In the best case, humanity gets a temporary taste of circumstances to come, hopefully leading to more immediate action to mitigate climate change impacts. At worst, this heated combination pushes climatic tipping points past their very tipping point. Which, as we know, is irreversible.

Good News of the Week:

The annual G7 summit is over. This time under Japanese leadership in Hiroshima. This cooperation format of the seven economically strongest Western nations (Japan, USA, Canada, France, Great Britain, Italy and Germany) with the participation of the European Union originally saw itself as a forum for discussing issues of the global economy. And in recent years, it has evolved into a hub that also has security and sociopolitical relevance. Therefore, an unsurprising item on the program this year was the visit of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Selenski to promote fighter jets.

Just as predictable as the condemnation of Russia's war of aggression was the theme of economic cooperation with China while distancing oneself from its geopolitical and human rights positions. The same applies to concerns about climate change, declining biodiversity and the too-slow expansion of renewable energies - albeit without any significant breakthroughs. Also, security of supply in globalized trade and cooperation with emerging economic powers. So no surprises at all?

Yes, in my opinion there are. After the delivery chain issues at the time of the Corona pandemic, the grain exports from Ukraine and fertilizers from Russia, which have been stopped in the meantime, have thrown another spotlight on the global food situation. Which is shitty to say the least. Among other things, because it is precisely the poorest countries that are most affected by the effects of climate change that are already being felt today.

Last year, under German auspices, the G7 and the World Bank founded the Global Alliance for Food Security (GAFS). According to its statutes, the alliance is committed to an agile, targeted and rapid response to food crises, which at the same time takes the right path toward sustainable agricultural systems. And pools the corresponding resources of its members: Germany, for example, has already been giving 2 billion euros annually for years to fight hunger in needy countries.

Now, according to a communiqué, the G7 have decided to provide a further 21 billion U.S. dollars in emergency aid. German Development Minister Svenja Schulze, initiator of the GAFS, commented: "The fact that the G7 are now united in their commitment to a further and holistic commitment one year later is a strong sign of solidarity with the Global South."

Of course, this is not enough. Oxfam, for example, points out that the UN has put the financial requirement in this regard at 55 billion. The G7 would have therefore failed in terms of development policy. But if you take a look at the bare figures, you will see that the G7 are contributing their fair share according to their economic performance. I am not aware of any corresponding initiative by China, India, Russia, Brazil or the Arab world. So we are on track so far. At least we are. And at least on a topic that too rarely makes it into the headlines.

Personal happy moment of the week:

My two children are getting older - and on their own feet. First, my daughter, who just turned 20, was in Budapest with the political science department of her university. Although only in her first year of study already as a group leader. And then my son, who just turned 15, was at the partner school in Paris. As the only one from the 8th grade and the youngest participant of the student exchange. Both not only completed their trip with aplomb, but also took the opportunity to present themselves as cosmopolitan, curious, self-confident young people. And made their dad proud.

I couldn't care less...

...about the voting behavior of Turks in Germany. Because they are allowed to vote in their home country, even if they are resident abroad. And they do. In large numbers. Unfortunately, two-thirds for Recep Erdogan. That was the case in the regular presidential election a week ago and that will be the case in the runoff election a week from now. I do not understand that. People who live in a well developed prosperous democracy should actually appreciate its canon of values - and not keep an autocrat in power.

As I write this...

...I am sitting on the train to Cologne. As I or my employer had booked it. Which is no longer a matter of course in view of the frequent strikes lately. The next round of negotiations between the union and Deutsche Bahn is scheduled for the day after tomorrow, so my return trip should also work out that day. On schedule. Which is tantamount to being late. Right now, we've been theoretically on the move for 12 minutes - but we're still standing on the platform in Munich. So everything is completely normal.

Post Scriptum

The Arab League has welcomed Syria's ruler Bashar al-Assad back into its midst - with a brotherly kiss. Those who were still waiting for proof that human rights do not always feel at home in the Arab cultural area (to put it mildly) now have it. The greeting "Salam alaikum" means "(May) peace be upon you". Yeah - but some terms and conditions apply.

#thoughts#aperçu#good news#bad news#news of the week#happy moments#politics#music#hubert von goisern#el nino#climate change#tipping point#g7#hiroshima#GAFS#Hunger#children#on own feet#turkey#election#train#cologne#bashar al assad#arab league#salam alaikum#erdogan#crisis#global warming#post script#global south

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Isn’t Every Year the Warmest Year on Record?

This just in: 2022 effectively tied for the fifth warmest year since 1880, when our record starts. Here at NASA, we work with our partners at NOAA to track temperatures across Earth’s entire surface, to keep a global record of how our planet is changing.

Overall, Earth is getting hotter.

The warming comes directly from human activities – specifically, the release of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels. We started burning fossil fuels in earnest during the Industrial Revolution. Activities like driving cars and operating factories continue to release greenhouse gases into our atmosphere, where they trap heat in the atmosphere.

So…if we’re causing Earth to warm, why isn’t every year the hottest year on record?

As 2022 shows, the current global warming isn’t uniform. Every single year isn’t necessarily warmer than every previous year, but it is generally warmer than most of the preceding years. There’s a warming trend.

Earth is a really complex system, with various climate patterns, solar activity, and events like volcanic eruptions that can tip things slightly warmer or cooler.

Climate Patterns

While 2021 and 2022 continued a global trend of warming, they were both a little cooler than 2020, largely because of a natural phenomenon known as La Niña.

La Niña is one third of a climate phenomenon called El Niño Southern Oscillation, also known as ENSO, which can have significant effects around the globe. During La Niña years, ocean temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean cool off slightly. La Niña’s twin, El Niño brings warmer temperatures to the central and eastern Pacific. Neutral years bring ocean temperatures in the region closer to the average.

El Niño and La Niña affect more than ocean temperatures – they can bring changes to rainfall patterns, hurricane frequency, and global average temperature.

We’ve been in a La Niña mode the last three, which has slightly cooled global temperatures. That’s one big reason 2021 and 2022 were cooler than 2020 – which was an El Niño year.

Overall warming is still happening. Current El Niño years are warmer than previous El Niño years, and the same goes for La Niña years. In fact, enough overall warming has occurred that most current La Niña years are warmer than most previous El Niño years. This year was the warmest La Niña year on record.

Solar Activity

Our Sun cycles through periods of more and less activity, on a schedule of about every 11 years. Here on Earth, we might receive slightly less energy — heat — from the Sun during quieter periods and slightly more during active periods.

At NASA, we work with NOAA to track the solar cycle. We kicked off a new one – Solar Cycle 25 – after solar minimum in December 2019. Since then, solar activity has been slightly ramping up.

Because we closely track solar activity, we know that over the past several decades, solar activity hasn't been on the rise, while greenhouse gases have. More importantly, the "fingerprints" we see on the climate, including temperature changes in the upper atmosphere, don't fit the what we'd expect from solar-caused warming. Rather they look like what we expect from increased greenhouse warming, verifying a prediction made decades ago by NASA.

Volcanic Eruptions

Throughout history, volcanoes have driven major shifts in Earth’s climate. Large eruptions can release water vapor — a greenhouse gas like carbon dioxide — which traps additional warmth within our atmosphere.

On the flip side, eruptions that loft lots of ash and soot into the atmosphere can temporarily cool the climate slightly, by reflecting some sunlight back into space.

Like solar activity, we can monitor volcanic eruptions and tease out their effect on variations in our global temperature.

At the End of the Day, It’s Us

Our satellites, airborne missions, and measurements from the ground give us a comprehensive picture of what’s happening on Earth every day. We also have computer models that can skillfully recreate Earth’s climate.

By combining the two, we can see what would happen to global temperature if all the changes were caused by natural forces, like volcanic eruptions or ENSO. By looking at the fingerprints each of these climate drivers leave in our models, it’s perfectly clear: The current global warming we’re experiencing is caused by humans.

For more information about climate change, visit climate.nasa.gov.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

i understand the instinct to tie the warm winter this year to climate change, and I'm not gonna say it's wrong to assume climate change has something to do with it obviously, but everyone in the tags talking about how they're so scared that it's so warm out should still make sure they know that it's an el niño year. how el niño precisely impacts weather events varies wildly depending on your location and the season (sometimes warmer/drier, sometimes colder/wetter), and if it helps assuage your fears i recommend checking out what meteorologists in your area have to say about how el niño will play out for you. but i at least know most of the united states and canada are projected to have a warmer winter than average because of it. the next question might be, can we attribute the particular warmth of this el niño winter so far to climate change? it's true that some climate models show that el niño events "will become more frequent and more intense" as climate change continues, but it's complex, there's a lack of consistency across different models, and folks are still working hard to figure it out. a 2021 IPCC report (link to helpful overview) showed an increased strength in ENSO sea-surface temperature anomalies since 1950, but "both paleoclimate data and climate models indicate that any changes seen are well within the range of natural variability"—it's possible that climate change accounts for increased strength, but at least right now, it's not really clear. for now, just try your best to make the most of whatever weird weather comes your way.

#i am so not an expert i took one (1) earth & weather class that i got a woefully average grade in lmao. i just felt like the fear in the#tags was missing some context#if someone who's actually knowledgeable in this would like to add or correct me that'd be great.#also sorry to my southern hemisphere girlies for the winter-centrism.......hope summer is going well

152K notes

·

View notes