#ekistics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

some things i kept coming back to this week...

literally couldn't close the PDF of my scan of the first metabolist manifesto from 1960. specifically, i left it on this page for a bamboo type community. to see a single shoot of bamboo and think, "skyscraper" really blows my mind. it's so simple, to observe nature - the first and most efficient designer.

i was also introduced to ekistics, or, the scientific study of human settlements.

a connection i have yet to see made comes down to numbers. all proposals for 50s-70s utopia will state a rough population count that is generally from 50k to about 75k, which makes them pretty soundly definable as a polis or city.

i cannot seem to find a reason accounting for design of this specific population size. luckily i have an architectural historian i can ask lol

truly on an ursula arc rn...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species (1859)

Human Civilization

C. Doxiadis - Theory of Ekistics

0 notes

Text

Mãn nhãn với 3 sân golf ở Lâm Đồng

Sân gôn ở Lâm Đồng từ rất lâu đã nhận sự quan tâm và mếm mộ của các golfer bởi chiếm dụng sắc đẹp ấn tượng bầu không gian yên tĩnh cùng kiểu dáng thiết kế lạ mắt. khi đến Dùng thử những sân golf này, không chỉ là đc đoạt được những vòng golf tuyệt hảo, các golfer còn được chiêm ngưỡng và ngắm nhìn vẻ đẹp tựa thước phim điện Ảnh sau đây.

SAM Tuyền Lâm Golf câu lạc bộ

địa điểm sân gôn

Địa chỉ: Phân khu công dụng số 7 & 8, Khu Đi Phượt Hồ Tuyền Lâm, thành phố Đà Lạt

sân gôn ở Lâm Đồng - SAM Tuyền Lâm Golf CLB nằm trong khu vực thiên nhiên thơ mộng của khu quy hoạch Du Lịch hồ Tuyền Lâm. Sân Golf Sacom tọa lạc ở chỗ thuận tiện cho việc dịch rời của những golfer. ví dụ là:

Cách sân bay Liên Khương khoảng 15km về phía Bắc

Cách cơ sở thành phố Đà Lạt khoảng 8km về phía Nam

Độ thử thách cao

phong cách thiết kế bởi: C.ty Ekistics (Canada)

Số hố: 18

Tổng chiều dài sân: 7035 yards

Par: 72

sân gôn là sự việc hết hợp hợp lý giữa cảnh sắc thiên nhiên và bàn tay, khối óc con người từ đó phát sinh ra một thiên đàng golf dành cho những người đam mê bộ môn Thể Thao này đến Trải Nghiệm.

Địa hình của sân gôn 18 hố này đc tạo nên bởi thung lũng sâu và những gò đát cao tự nhiên, ở trung tâm đc bảo phủ bởi rừng thông hùng vĩ. điều đó đóng góp phần sinh ra những thách thức tuyệt hảo, mong chờ các golfer chinh phục. không chỉ có thế, vùng green còn cắt ngang bởi những hố cát lớn và còn lạch nhỏ, gây cản trở cho ngươi chơi khi đánh bóng vào khu vực green.

Theo đánh giá của đa số golfer, 2 hố golf khó đoạt được nhất là hố số 3 và 12. khi phát bóng tại số 12, người chơi có khả năng sẽ bị khuất góc nhìn vì đường quẹo của khu vực fairway nghiêng hẳn theo bên phải.

sân golf bên hồ Tuyền Lâm thơ mộng

Với vị trí nằm gần khu Du Lịch Hồ Tuyền Lâm, nơi đây là điểm đến không còn bỏ lỡ trong số những chuyến Du Lịch golf của bạn. Với cảnh quan đẹp tựa như những thước phim điện Hình ảnh, đây là điểm đến check - in được nhiều khách yêu mến. chiếm dụng đia hình da dạng từ rừng, núi, hồ, thác,... Giúp khác nước ngoài thuận lợi Trải Nghiệm những chuyển động Du Lịch hấp dẫn như cắm trại, câu cá, quốc bộ, leo nui, tham quan làng dân tộc K'ho, chèo thuyền,...

Nằm giữa thung lũng, nép mình bên những rừng thông, sân gôn và thảm cỏ xanh mướt mắt, khu nghỉ dưỡng Swiss - Belresort tựa như 1 tòa lâu đại nguy nga với sắc trắng cùng họa đồ thiết kế sang trọng. Với khối hệ thống gồm 125 căn biệt thự dựa sống lưng vào núi & có hướng view ra biển.

Bảng Báo Giá sân gôn

Báo Giá khuyến mãi khí đặt sân SAM Tuyền Lâm qua Alegolf là:

Ngày thường: 1.850.000đ

Cuối tuần: 2.250.000đ

Lưu ý: Giá trên rất có thể thay đổi tùy theo từng thời điểm. Để cập nhật những thông tin về Bảng Giá sân golf sam tuyền lâm tiên tiến nhất, quý golfer vui vẻ tương tác đến số Hỗ trợ tư vấn 19002093.

The Dalat at 1200 Golf Course

phong cách thiết kế sân golf

Địa chỉ: xã Đạ Ròn, huyện Đơn Dương, tình Lâm Đồng

sân gôn đà lạt nằm cách sân bay Liên Khương chỉ khoảng 15 phút dịch rời. điều ấy đã thu hút nhiều golfer từ Đà Lạt đến luyện tập & thi đấu.

thiết kế bởi: Peter Rousseau & Kyi Hla Han

Số hố: 18

Số gậy tiêu chuẩn: 73

sân golf ở Lâm Đồng - The Dalat at 1200 với thiết kế khác biệt là vấn đề đến không thể bỏ lỡ cả với các golfer chuyên nghiệp hóa và không chuyên. nguyên lý thiết kế sân gôn Đạ Ròn d��a theo sự hài hòa và hợp lý với thiên nhiên và môi trường.

Tọa lạc tại địa hình đồi núi của Đà Lạt, cao hơn 1200m so với mực nước biển. sân golf Đạ Ròn này có khí hậu ôn đới lanh tanh. điều đó giúp các golfer hoàn toàn có thể chơi gôn tại The Dalat at 1200 quanh năm.

không những được thỏa thích khắc ghi những cú swing điệu nghệ tại sân golf Đạ Ròn, các golfer còn đc cảm nhận vẻ đẹp của các sân golf tại đây.

sân golf với độ thách thức cao

Các hố golf được nằm rải rác bên trên một diện tích lớn, xen Một trong những rừng thông và đồi núi cùng một hồ nước tự nhiên khép kín tại chính giữa sân gôn. Sự chuyển đổi độ cao giữa các hố khiến cho người chơi cần di chuyển bằng xe điện. Sự kết hợp giữa các chướng ngại vật, Việc các chướng ngại vật đa dạng và phong phú và địa hình nhấp nhô của núi đồi cao nguyên nên đòi hỏi kỹ thuật và các cú đánh chính xác.

Các chướng ngại vật được bố trí quanh sân với sự đo lường cảnh giác làm không giảm ý chí đoạt được của những golfer. không chỉ là mang đến những thử thách thú vị, những chướng ngại vật đa dạng mẫu mã này như cánh đồng lúa, hồ nước, rừng thông, suối nước ngọt,... Cũng tô điểm thêm vẻ đẹp thơ mộng nơi đây. đặc trưng, lúc tập luyện tại sân gôn Đạ Ròn này, bạn cũng có thể dễ dàng bắt gặp những đám mây phủ bông bềnh & không gian mát lạnh khi cơ golf vào buổi sáng sớm.

Chất lượng mặt cỏ được chú trọng

sân gôn được dùng hai loại cỏ:

Vùng green: dùng cỏ Bentgrass Aprons

Fairway & rough: sử dụng cỏ Bermuda

Việc sử dụng những loại cỏ chất lượng cao, đạt chuẩn mức quốc tế mang đến cho các golfer những Dùng thử tuyệt vời.

Bảng Giá sân gôn

Bảng Giá khuyến mại khí đặt sân The Dalat 1200 qua Alegolf là:

Ngày thường: 1.800.000đ

Cuối tuần: 2.100.000đ

Lưu ý: Giá trên rất có thể thay đổi tùy thuộc vào từng thời điểm. Để cập nhật những thông báo về Báo Giá Sân Golf Sacom mới nhất, quý golfer vui mừng liên hệ đến số đường dây nóng 19002093.

Dalat Place Golf câu lạc bộ (Sân golf Đồi Cù)

vị trí sân golf

Địa chỉ: Đường Phù Đổng Thiên Vương, Tp. Đà Lạt, tỉnh Lâm Đồng

sân gôn Đồi Cù nằm ở gần trung tâm phố xá, dọc hồ Xuân Hương. do vậy, việc các golfer di chuyển đến Dalat Place Golf CLB khá thuận lợi. sân golf Đạ Ròn cách sân bay Liên Khương khoảng 15km. Bên cạnh đó, các golfer sinh sống & thao tác làm việc tại TP.HCM hoàn toàn có thể đến sân golf này bằng ô tô với quãng đường khoảng 250km.

sân gôn với bề dày lịch sử vẻ vang

sân golf ở Lâm Đồng - Dalat Place Golf câu lạc bộ được nghe đến là sân golf trước hết tại nước ta. Kế hoạch thành lập sân golf the dalat at 1200 xuất phát từ những năm 20 của thế kỉ XIX. Đầu những năm 1930, sau khoản thời gian vua Bảo Đại đến Pháp đã quyết định xây dựng một sân golf cho riêng mình như vậy tại Đà Lạt.

ban đầu, sân golf Đồi Củ chỉ có 6 hố. sân gôn này được xây đắp nhằm mục đích đáp ứng cho nhu yếu trong phòng vua và hoạt động đối ngoại của triều đình. Đến năm 1945, sân golf bị bỏ hoang. thông qua bao nhiêu thăng trầm của lịch sử vẻ vang, đến năm 1990, sân golf này đc bắt đầu khởi công cải tạo lại. sân golf đã được kiến tạo lại vào năm 1994.

thiết kế sân golf

Số hố: 18

Chiều dài sân: 7009 yards

Số gậy tiêu chuẩn: 72

sân gôn ở Lâm Đồng này được thiết kế theo phong cách dựa trên sự hợp lý giữa tự nhiên & môi trường thiên nhiên. đấy là một sân gôn nằm trong khuôn viên rộng lớn & được bao phủ bởi cảnh quan cây cỏ tự nhiên tươi đẹp của vùng núi Đà Lạt. sân golf nằm ngay ở kề bên hồ Đạ Ròn thơ mộng. chiếm hữu khí hậu lành tính, lanh tanh nơi đây là vị trí chơi gôn và nghỉ ngơi lý tưởng mà bạn không nên bỏ qua.

Loại cỏ đc dùng tại sân gôn ở Lâm Đồng - Dalat Place Golf Club:

Khu vực cỏ cao và fairway: cỏ Bermuda

Khu vực green : cỏ Bentgrass (PENN A- 4)

Khu vực tee : cỏ Paspalum

Hố golf đc xã hội golfer bình chọn khó đặc biệt là hố số 6:

Với sự sắp xếp của khu vực phát bóng vượt ra khỏi khu vực giới hạn phía bên phải, bên trái là hồ nước & có 1 fairway hẹp nhu cầu kỹ thuận cao & những cú đánh chuẩn chỉnh xác.

không chỉ vậy, bên trái đoạn ngoặt hẹp có nước & ngoài khu vực giới hạn để bằng mọi cách đánh tới hố gôn được phủ bọc bởi hố cát & nước

Địa hình gập ghềnh

Địa hình gập ghềnh thoải mái và tự nhiên là 1 trong những đặc điểm nhấn lúc nhắc đến sân gôn Đạ Ròn. Khu vực chơi của sân nằm rải rác bên trên diện tích 2.100 ha xen giữa là những đồi núi và rừng thông. cùng với một hồ nước thoải mái và tự nhiên khép kín. Sự chuyển đổi độ cao này đã tạo nên nhiều gian nan với các

bên trên đó là những thông báo về top 3 sân gôn ở Lâm Đồng mà bạn không nên bỏ lỡ. nếu như có dịp đến với Lâm Đồng, đừng bỏ qua thời cơ Trải Nghiệm những sân gôn sau đây nhé. Nếu quý golfer đang tìm kiếm tọa độ chơi golf hoàn chỉnh thì có thể xem thêm ngay những vị trí mà Alegolf đã đề cập ở bên trên.

0 notes

Photo

Masterplan for Islamabad, designed by Constantinos A. Doxiadis

#Islamabad#Pakistan#urbanism#urban planning#city planning#Doxiadis#ekistics#architecture#town planning

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The mineral rich ECBS (Enormous Coyote like Beast Scat) has a very high Ag (Silver) content. The ISEE team has been deployed to collect as many specimens as possible to discover how the ECBS digestion acts somewhat like an ore smelter. This is only one of the anomalies discovered while Exploring the surface of exoplanet EPIC 201505350 c. . #isee #interstellar_exoplanet_ekistics #Lego #classicspace #epic201505350c #joecow3d #stereolego #stereoscopic #stereogram #coyotescat #toy_photographers #toyphoto #toyphotography #brickcentral #stuckinplastic #exoplanet #ekistics #interstellar #legominifigure (at Saguaro Lake) https://www.instagram.com/p/CGNEIvPl0D4/?igshid=7yzlpbrknx29

#isee#interstellar_exoplanet_ekistics#lego#classicspace#epic201505350c#joecow3d#stereolego#stereoscopic#stereogram#coyotescat#toy_photographers#toyphoto#toyphotography#brickcentral#stuckinplastic#exoplanet#ekistics#interstellar#legominifigure

1 note

·

View note

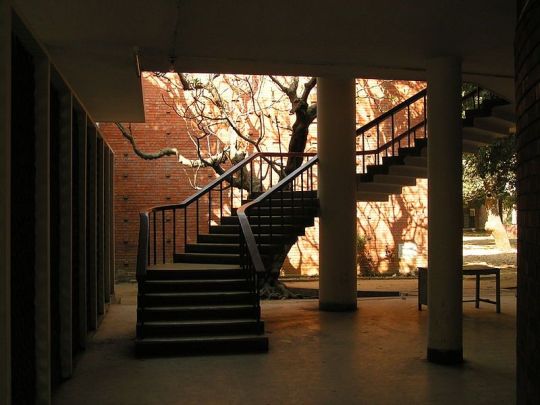

Photo

Faculty of Architecture and Ekistics, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Pic by: @ar.tanzeel_pasha ✔️Send Images to get featured on this Page 🔥 #jamiamilliaislamia #jamiamilliaislamiauniversity #jamiaphotos #jamia #central #jamiaentrance #student #jamiamilia #jmilove #photography #ekistics #jamiastudents #architecture #studentlife #jmientrance #engineering #throwbackphoto #lovecollege #lovecollegelife #centraluniversity #jamialovers #technology #jmi #collegephotography #jamiamilliaislamianewdelhi #jamialove #jamiainframe #beautiful #missingcollegedays #memoriesforlife (at Department of Architecture, FA+E) https://www.instagram.com/p/CWiEO-UPr_R/?utm_medium=tumblr

#jamiamilliaislamia#jamiamilliaislamiauniversity#jamiaphotos#jamia#central#jamiaentrance#student#jamiamilia#jmilove#photography#ekistics#jamiastudents#architecture#studentlife#jmientrance#engineering#throwbackphoto#lovecollege#lovecollegelife#centraluniversity#jamialovers#technology#jmi#collegephotography#jamiamilliaislamianewdelhi#jamialove#jamiainframe#beautiful#missingcollegedays#memoriesforlife

0 notes

Photo

Sexuality & Gender In Columbia

Okay, so this is a frankly huge topic to cover, and because there is so little direct reference to any non-heterosexual/cisgender culture in the games, a lot of this will be me sharing/explaining my headcanons/worldbuilding. My ideas will be based on historical record of LGBT+ struggles at the time (1890-1915) and mostly US-centric, as Columbia seems to be fairly westernized. in addition, I will be focusing purely on the lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans communities to cut down on post size and research time. Here we go!

Note: These all refer to Columbia (Rapture has a separate post) culture in the peak of the city’s life- a snapshot into queer Columbia circa 1910, roughly speaking. As such my talk about the culture is purely as I’d imagine it to be at that specific time only with no details as to the cultural development to that point.

cw for homophobia, transphobia, q slur

Sexuality In Columbia

If you’re not straight it’s over for you

Quips aside, just from playing the game you can tell Columbia is ruled by the most staunch of conservatism. The Edwardian Era in real-world history made heavy emphasis on modesty and a sense of duty but Columbia takes it a step beyond, and this can be seen in most every example of media or dialogue found in-game. Having such traditional Biblical leanings, it can easily argued that this also extends to sexuality.

Right off the bat, I feel like this is Heterosexual (& Cisgender) Land™. Any other sort of attraction, be it gay, bisexual, or anything else, is considered reckless experimentation at best and ungodly and deserving of punishment at worst. Aside from the religiously-motivated belief that only straight relationships are legit, there’s another reason they’re so heavily emphasized- population growth. Columbia, for all its pomp still has a relatively small population on a national scale- just from some educated guesses I’d put it around the borough to town region, as indicated on the settlement hierarchy of ekistics. While the limited space of the city means that the population can’t just continue to grow, a certain rate of births is needed to keep the population level.

Interestingly enough, even though Columbia is a hotspot of religious zealotry, the city still follows the conventions of Edwardian/Early WWI society- very proper, highly formalized in its ideals. Aside the propaganda and fearmongering, personal details are still taboo in polite conversation.

Cruising is done in places where social conventions are significantly different from formal events or even everyday conventions- namely the beach, pubs and lounges.

In the same vein, hookups, flings, and dates are called vague things like “going out to lunch/drinks”, “going for a stroll” or “having a picnic” and same-gender partners are typically referred to as close friends. It’s all very underhanded, the result of both Edwardian discreetness and closeted language.

Gender In Columbia

Like most of Columbian society, the queer groups in Columbia tend to gather based on gender. Lesbians share space with bisexual women, and gay men stick with bisexual men. As far as trans communities go, however, the cisnormative, rigid interpretation of gender predominant in Columbia means that they tend to be misunderstood among the other queer groups. Typically not in a blatantly hostile way but rather an obnoxiously condescending “poor confused dear” way.

Gender is not so much an identifier as much as an determinator; whatever you are assigned will be the factor driving not only your upbringing but your life choices as well.

There are quite a few social clubs that operate as safe spaces for the community- they typically rotate between the members’ houses and frequently merge or splinter with or from other groups, going from book club, to knitting social to any other politely banal gathering.

For those looking to dress how they’d like in safety, ‘costume clubs’ are popular among gender non-conforming, trans people and those interested in crossdressing. They present themselves as sort of novelty dance halls with every day being a masquerade. While technically legal, their image is strongly connected to immorality and looseness in Columbia and as such they’re rare and subject to higher levels scrutiny then other halls.

Because of the rigidity of the culture, the LGBT+ culture in Columbia uses nonverbal queues to state their identities- for example men place certain flowers in buttonholes or alternatively pin them to their lapels to let outsiders know they’re in the community. Women can put these same blossoms in their hats, brooches and hair. These include flowers such as lavender, violets, pansies, carnations and daffodils.

There are HRT gene tonics for sale- they’re marketed under the guise of improving a woman’s femininity or man’s masculinity, they’re sold in pharmacies in the health and beauty aisles without the need for a prescription. This helps some looking to transition do so much easier, though the issue of financial barriers for those who are younger and/or living in poverty still linger. As far as options like SRS go, the procedure is entirely underground, practiced by surgeons of varying repute. While being able to do so successfully is considered a show of skill, most practitioners and citizens are morally opposed to the idea.

Unlike Rapture, there’s not many fun or quirky terms for LGBT+ citizens. Those with same gender attraction are rudely referred to as “victims of unnatural passions” and those who ID as anything other then cisgender are accused of “falling into delusions of identity”. Among themselves though, WLW call themselves “Lady Lovers of Liberty” (as in the statue based on the Roman goddess Libertas) while MLM call themselves “Sons of Antinous” while trans citizens typically refer to themselves as “Children of Agdistis”. (Note that while Agdistis was portrayed as intersex in Roman mythology, their nonbinary existence and transformative identity made them a relatable icon for most trans people in Columbia)

Questions or comments? Let me know! Thanks for reading.

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo

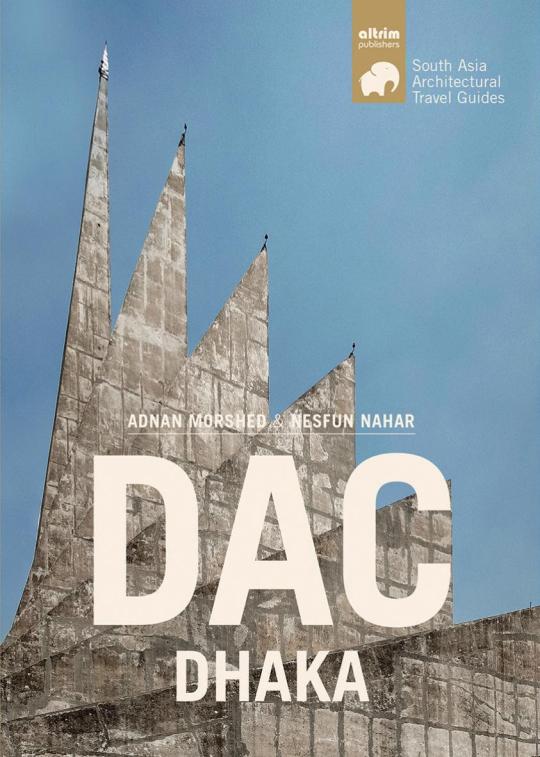

Kamalapur Railway Station in Dhaka

Architectural Optimism of Bangladesh

Saša Šimpraga, 2021.

Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect and architectural historian with focus on history and theory of modern architecture and urbanism; global history; urban poverty and spatiality; water and architectural historiography; and ecological urbanism in developing countries. He received his Ph.D. and Master’s in architecture from MIT and completed his pre-doctoral studies at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art and postdoctoral under Verville Fellowship at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Morshed is the author of several books among other: Impossible Heights: Skyscrapers, Flight, and the Master Builder which examines the American fascination with the skyscraper and the airplane as part of a widely shared cultural phenomenon--the aesthetics of ascension--that characterized the interwar period. His books also include DAC, Dhaka through Twenty-Five Buildings.

He is a professor at the School of Architecture and Planning of the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

Adnan Morshed is also involved with local and international intiatives on preservation of modernist architectural heritage of Bangladesh. We talk to him on the occasion of current international appeal to save the Kamalapur Railway Station in Dhaka from demolition.

SŠ: A gem of the Modern Movement in South Asia, The Kamalapur Railway Station in Dhaka, designed by Daniel Dunham and Robert Boughey in the 1960s is threatened due to the an urban expansion plan of the Dhaka Metro Rail's Line that includes its demolition and replacement by a new infrastructure, rather than its adaptation. What is the significance of the building and its current status?

Adnan Morshed: Kamalapur Railway Station is a rare modern train station in South Asia. It adopts an aesthetic vocabulary of tropical modernism for a public building in ways that have not been seen before in the region. The station’s modernist architecture breaks with colonial precedents both in the imperial center and on the subcontinent. In London, St. Pancras Station (1863–76) encapsulated modern values of mobility and exchange, while the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus; built in 1888 and now a UNESCO World Heritage) in Mumbai and Howrah Station (1906) in Kolkata functioned as symbols of imperial hegemony.

The histories of colonialism and train infrastructure are deeply intertwined in South Asia. In 1862, the Eastern Bengal Railway Company opened the first railway line in the region from which it took its name. Connecting Kolkata with the western Bangladeshi town of Kushtia, this expansion of train services signaled a new phase in the growth of East Bengal’s colonial economy. Due to geographical challenges posed by Bengal's deltaic terrain, the railway did not arrive in Dhaka until the following century, after the city’s economic profile had risen and it was subsequently made, in 1947, the provincial capital of then-East Pakistan. In 1958, the government approved the creation of a new railway depot, which was inaugurated a decade later as Kamalapur Railway Station. Not only was it one of the largest modern railway stations in South Asia, but it also embodied changing conceptions of modernity, from the bracing mobility of 19th-century railways to the soaring modernism that defined the 1960s.

Kamalapur Railway Station, Photo by Anik Sarker/ Wikipedia

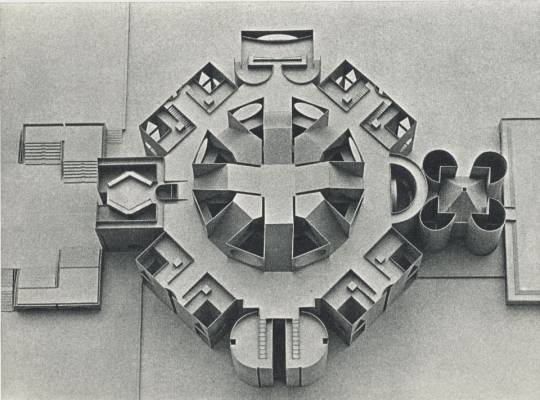

SŠ: Also in danger of demolition is the Dhaka University Teacher-Student Center Building by Greek architect Constantinos Doxiadis (the mastermind behind planning the city of Islamabad) from early 1960s. The structure exemplifies a modernist architectural sensitivity toward spatial needs for tropical climatic conditions. TSC's dome-shaped structure with empty spaces around is considered an iconic landmark not only inside Dhaka Uiversity campus, but in the broader cityscape of Dhaka. How optimistic are you about its future? And what is the general status of modernist architectural heritage of Bangladesh?

Adnan Morshed: I am concerned about the mid-20th-century buildings in Bangladesh because of the ways the notion of development is taking precedence over environment, history, and, generally, human wellbeing. Many buildings are about to face the wrecking ball. These buildings include the Teacher-Student Center or TSC. Located at the historic heart of the University of Dhaka, TSC exemplifies a type of tropical modernism that blends local architectural traditions of space-making—particularly the indoor-outdoor continuum and generation of space around courtyards—with the abstract idiom of the International Style. The complex of buildings was designed by the Greek architect, planner, and theoretician Constantinos Apostolos Doxiadis (1913–1975) in the early 1960s. This was a turbulent time marked by conflicting currents of political tension and architectural optimism in what was then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. On the one hand, the two wings of postcolonial Pakistan were at loggerheads because of the political domination of East Pakistan by the military junta based in West Pakistan. On the other hand, many architectural opportunities arose in East Pakistan, which benefitted from American technical assistance. The United States allied with Pakistan as part of its Cold War-era foreign policy to create a geostrategic buffer against the socialist milieu of the Soviet Union–India axis in South Asia. Under the purview of a technical assistance program, the United States Agency for International Development and the Ford Foundation provided support for building educational and civic institutions in East Pakistan. Since there was a dearth of experienced architects in East Pakistan, the government sought the services of American and European architects for a host of buildings that were constructed during the 1960s. Doxiadis was among them.

TSC, Photo by Fasiha Binte Zaman/ Wikipedia

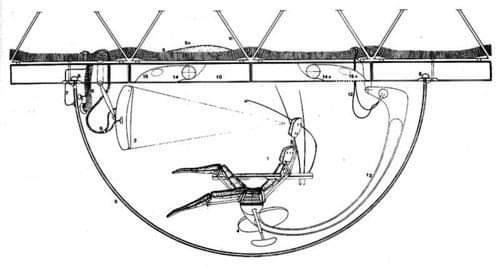

TSC is also a demonstration of Doxiadis’s idea of ekistics, by which he meant an objective, comprehensive, and integrative approach to all principles and theories of human settlements. Criticizing the top-down planning model which he viewed as a central problem associated with modernism, Doxiadis employed the notion of ekistics to promote a multidisciplinary, inclusive, and bottom-up approach. He hoped that such a method would create a synergy of local and global influences, by which one could successfully meld a data-driven theorization of planning, universal values of harmonious living, and place-based cultural inflections.

In this vein, Doxiadis aligned the TSC’s ensemble of buildings on an east-west axis, to take advantage of the prevailing breeze from the south or north. The three-story Student Union Building features a “double roof” that minimizes heat gain by allowing cool breezes to pass in between the two canopies. The ingenious solution proved to be a trendsetting feature, but it was just one of the complex’s many innovations. Doxiadis covered the auditorium with a reinforced concrete parabolic vault, a pioneering construction technique that had yet to be tested in the country. Covered walkways, supported on steel columns, weave together the major buildings and green spaces, serving as the social spine of the entire complex. In the post-Independence period, TSC became the epicenter of political agitation within Bangladesh, serving as a backdrop to political demonstrations.

SŠ: Pioneer od modernist architecture in Bangladesh, Muzharul Islam, began hes career in the 1950s. Born in 1923, he went to study architecture in the United States, and then returned to Bangladesh. Along with his teacher Louis Kahn, he also brought Paul Rudolph and Stanley Tigerman to work in Bangladesh, and three of them came to be known as the American Trio. Apart from the Trio, it was Islam's style that dominated Bangladesh architecture from 1950s onwards. What is his legacy in architectural history of Dhaka?

Adnan Morshed: Not only was architect Muzharul Islam Bangladesh's pioneering modernist architect, he was also an activist designer who viewed architecture as an effective medium for social transformation. His early work shows how architecture was deeply embedded in post-Partition politics.

Consider his ��master piece,” the Faculty of Fine Arts (1953-56) at Shahbagh in Dhaka. At first encounter, the building presents the image of an international-style building, with a quiet and dignified attention to the architectural demands of tropical Bengal. Closer inspection, however, hinders the Eurocentric tendency to measure the building's “modernity” exclusively through a “Western” lens. A host of nuanced architectural modulations and environmental adaptations reveals how Muzharul Islam's work cross-pollinates a humanising, modernist architectural language with conscious considerations of climatic needs and local building materials.

Faculty of Fine Arts, Photo by Rossi101/ Wikipedia

The literature on South Asian modern architecture usually identifies the Faculty of Fine Arts as the harbinger of a Bengali modernism, synthesising a modern architectural vocabulary with climate-responsive and site-conscious design programmes. What has not been examined in this iconic building is how Islam's work also provides a window into the ways his architectural experiments with modernist aesthetics were part of his inquiries into the ongoing politics of Bengali nationalist activism.

Muzharul Islam interpreted the prevailing political conditions in his homeland as a fateful conflict between the secular humanist ethos of Bengal and an alien Islamist identity imposed by the Urdu-speaking ruling class in West Pakistan. The turbulent politics in which he found himself influenced his worldview as well as his fledgling professional career. The young architect began his design career in a context of bitterly divided notions of national origin and destiny, and his architectural work would reflect this political debate. He felt the need to articulate his homeland's identity on ethno-cultural grounds, rather than on a supra-religious foundation, championed by West Pakistani power-wielders. Muzharul Islam's Faculty of Fine Arts embodied these beliefs.

With his iconoclastic building, Islam sought to achieve two distinctive goals. First, the building introduced the aesthetic tenets of modern architecture to East Pakistan. For many, its design signalled a radical break from the country's prevailing architectural language for civic buildings. These buildings were designed either in an architectural hybrid of Mughal and British colonial traditions, popularly known as Indo-Saracenic, or as utilitarian corridor-and-room building boxes, delivered by the provincial government's Department of Communications, Buildings, and Irrigation (CBI). The Faculty of Fine Arts was an unambiguous departure from the colonial-era Curzon Hall (1904–1908) at the Dhaka University, within walking distance of Islam's building, and the Holy Family Hospital (1953; now Holy Family Red Crescent Medical College Hospital).

Faculty of Fine Arts, Photo: Wikipedia

Second, the Faculty of Fine Arts' modernist minimalism—rejecting all ornamental references to Mughal and Indo-Saracenic architecture—was a conscious critique of the politicised version of Islam that had become a state apparatus for fashioning a particular religion-based image of postcolonial Pakistan. By abstracting his design through a modernist visual expression, Muzharul Islam sought to purge architecture of what he viewed as the political associations of instrumental religion.

SŠ: Internationally, perhaps the most known modernist structure in Bangladesh is the National Parliament Complex, designed by Louis Kahn and associates. Its construction began in 1964, in what is now known as the Decade of Development for Bangladesh and time when Dhaka was the second capital of Pakistan. When talking about architecture in general, Muzharul Islam stated that „practical aspects of architecture are measurable – such as, the practical requirements, climatic judgments, the advantages and limitations of the site etc. – but the humanistic aspects are not measurable.“ Those aspects come when the architect leaves and building starts its life. How did that highly acclaimed complex came to be a part of the national identity and how its architecture influences culture in a broader sence?

National Parliament Complex in Dhaka, Photo: Yes, Louis Kahn

Adnan Morshed: The American architect Louis Isadore Kahn's Parliament building in Dhaka is considered one of the architectural icons of the twentieth century. Intriguingly, Kahn was not the first choice for the project. After two masters, Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto, had turned down the invitation from the government of Pakistan, the megaproject went to the architect from Philadelphia. After multiple design iterations and many bureaucratic entanglements, the construction of the Parliament building began in October 1964, at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar.

Kahn first visited Dhaka in early March of 1963, after he had received the commission to plan the Parliament complex of East Pakistan. Five years earlier, the commander-in-chief of the Pakistani army, Mohammad Ayub Khan, took control of the government through a military coup and imposed martial law in October 1958. In 1960, the military man was “elected” to a five-year presidency. Pakistan's new constitution of 1962 called for a “democratic” election to be held in 1965. The decade of the 1960s was a politically tumultuous period in East Pakistan. Bengalis felt exploited and ignored by West Pakistan's military regime and, consequently, dreamed of independence from the doomed political geography of a nation with two units separated by over 1,000 miles. Aware of the political and economic disparity between the two halves of Pakistan and concerned about his own re-election bid, Ayub Khan's administration came up with a political strategy to mitigate the grievance of the Bengalis.

National Parliament Complex in Dhaka, Photo: Yes, Louis Kahn

The idea of a “second capital” for East Pakistan was born in this context. This showcase capital would, it was hoped, “bind East Pakistan more firmly to the nation by conducting the nation's business for half of each year.” The political drama that ensued from then on explains how the Parliament building, first conceived as a “bribe” for the Bengalis, gradually took on a whole new identity as a symbol of the people's struggle for self-rule. With rudimentary construction tools and bamboo scaffolding tied with crude jute ropes, approximately 2,000 lungi-clad construction workers erected a monumental government building. Slowly but steadily, they unwittingly portrayed the broader resilience of a nation revolting against economic and social injustice. If the Shahid Minar symbolised the language movement during the 1950s, the Parliament building portrayed the rise of the independence-minded Bengalis during the 1960s.

Kahn searched for inspirations from the Bengal delta, its rivers, green pastoral, expansive landscape, raised homesteads, and land-water geography. Soon after he had first arrived in Dhaka, he went on a boat ride on the Buriganga River and sketched scenes to understand life in this tropical land. He didn't have any problems in blending Bengali vernacular impressions with those of classical Greco-Roman and Egyptian architecture he had studied during the 1950s. As the war broke out in 1971, Kahn's field office in East Pakistan quickly closed and construction work discontinued. During the liberation war, an ironic story persisted that Pakistani pilots didn't bomb the building assuming that it was a ruin! That “ruin” eventually became an emblem of the country, adorning national currency, stamps, rickshaw decorations, advertisements, official brochures, and so on. When it was more or less completed in 1983—more than a decade after East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) emerged as a new nation-state and 9 years after Kahn's unexpected death in New York City—the Parliament complex emblematised the political odyssey of a people to statehood.

National Parliament Complex in Dhaka, Photo: Yes, Louis Kahn

Kahn searched for inspirations from the Bengal delta, its rivers, green pastoral, expansive landscape, raised homesteads, and land-water geography. Soon after he had first arrived in Dhaka, he went on a boat ride on the Buriganga River and sketched scenes to understand life in this tropical land. He didn't have any problems in blending Bengali vernacular impressions with those of classical Greco-Roman and Egyptian architecture he had studied during the 1950s. As the war broke out in 1971, Kahn's field office in East Pakistan quickly closed and construction work discontinued. During the liberation war, an ironic story persisted that Pakistani pilots didn't bomb the building assuming that it was a ruin! That “ruin” eventually became an emblem of the country, adorning national currency, stamps, rickshaw decorations, advertisements, official brochures, and so on. When it was more or less completed in 1983—more than a decade after East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) emerged as a new nation-state and 9 years after Kahn's unexpected death in New York City—the Parliament complex emblematised the political odyssey of a people to statehood.

National Parliament Complex in Dhaka, Photo: Yes, Louis Kahn

SŠ: Transformation of Dhaka today is intensive. What would be some of the significant architectural achievements in contemporary Dhaka and Bangladesh?

Adnan Morshed: The architectural scene in Bangladesh has been thriving with a “new” energy over the past two decades or so. Bangladeshi architects have been experimenting with form, material, aesthetics, and, most importantly, the idea of how architecture relates to history, society, and the land. Their various experiments bring to the fore a collective feeling that something has been going on in this crowded South Asian country. One is not quite sure about what drives this restless energy! Is it the growing economy? The rise of a new middle class with deeper pockets? Is it an aesthetic expression of a society in transition? Is it aesthetics meeting the politics of development?

Whatever it is, an engaged observer may call this an open-ended search for some kind of “local” modernity. Bangladeshi architects have been winning architectural accolades from around the world for a variety of architectural projects. High-profile national architectural competitions have created a new type of design entrepreneurship, yielding intriguing edifices. Architects have also been expanding the notion of architectural practice by engaging with low-income communities and producing cost-effective shelters for the disenfranchised. Traditionally trained to design stand-alone buildings, architects seem increasingly concerned with the challenges of creating liveable cities.

No doubt it is an exciting time in Bangladesh, architecturally speaking, even if the roads in the country's big cities are paralysed by traffic congestion and a pervasive atmosphere of urban chaos. In the midst of infernal urbanisation across the country, an architectural culture has been taking roots with both promises and perils, introducing contentious debates about its origin, nature, and future.

Architecturally, the 1980s was an interesting time, as divergent ideas began to permeate architectural thinking in the country. Three stories should be mentioned. An “avant-garde” architectural study group named Chetona (meaning awareness) sought to introduce critical thinking as an essential part of architectural practice. Many architects, senior and junior— disillusioned with the prevalent role of architecture as primarily a professional practice without broader social visions and engagement with history and culture—gravitated toward Chetona, meeting at Muzharul Islam's architectural office, Bastukalabid, at Poribagh. The iconoclasm of the study group revolved around reading critical writings in architecture, criticism of current methods of architectural pedagogy, and reasoned questioning of architecture as a technical discipline. The group's reading list ranged from Rabindranath Tagore to the Franco-Swiss architect Le Corbusier to the Norwegian architectural theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz.

The influence of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA), an architectural prize established by Aga Khan IV in 1977, was also felt strongly during the 1980s. The award sought to champion regional, place-based and culture-sensitive architectural impetuses in Islamic societies. Awardees included projects in contemporary design, social housing, community development, restoration, adaptive reuse, and landscape design. Architects were inspired to look for a “spirit of place.” Regionalism was in vogue.

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture's flagship magazine, Mimar: Architecture in Development, first published in 1981, influenced many Bangladeshi architects and architecture students in thinking beyond western modernism and the aesthetic conventions it allegedly created. At its inception, Mimar was the sole international architecture magazine focusing on architecture in the developing world. In many ways, the magazine's celebration of “local” expanded the scope of architectural practice in the country and gave rise to new aspirations among architects, who were willing to search for organic roots in architecture.

Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka by Marina Tabassum, 2016 Aga Khan Award Recipient

The new architectural aspirations coincided with the rapid urbanisation of Bangladesh and the rise of an urban middle class that spawned a flourishing culture of architectural patronage. A historically agrarian country, Bangladesh began to urbanise rapidly from the late 1980s. The country's total urban population rose from a modest 7.7 percent in 1970 to 31.1 percent in 2010. Impoverished rural migrants began to flock to major cities, particularly the capital, Dhaka, in search of employment and better lives. Its population skyrocketed from 1.8 million in 1974 to more than 6 million in 1991 and to nearly 18 million today. The capital city's massive population boom created an unsustainable demand on urban land, and in return, land values increased.

During this transitional period, real estate developers emerged as powerful economic actors in Dhaka and beyond, playing a key role in replacing traditional single-family houses with multi-story apartment complexes. Meanwhile, public-sector housing failed to meet the demand, and in this vacuum, private real estate companies flourished rapidly. As private developers became key actors in the city's housing market, a trade association was needed to regulate the real estate sector and to ensure fair competition among its members. The stratospheric rise of private real-estate developers suggested that there was a robust market for high-density, multifamily apartments, even though affordability remained a major hurdle. Many architects experimented with material, form, spatial organisation, construction, aesthetic expression, and the individual plot's urban relationship to the neighbourhood.

A burgeoning class of urban entrepreneurs—who made their fortunes in the country's export-oriented ready-made garments industry, manufacturing and transportation sectors, construction industry, and consumer market—emerged as a new generation of architectural patrons, investing hefty amounts of money to build their signature single-family houses and other projects, including apartment complexes, hospitals, shopping malls, private schools and universities, factories, spaces of worship, etc.

And, happily, architects began to find work abundantly from the mid-1990s. Design consultancy until the early 1990s was limited to a handful of architectural firms. But soon thereafter new, smaller firms, run by younger architects, began to reshape the traditional methods of architectural design practice in the country.

The liberalisation of the market, the emergence of a strong private sector, and rapid urbanisation resulted in the need for a range of building typologies and related architectural design services. In the public sector, government organisations began to evaluate the social and commercial value of aesthetic expression and hired architectural firms to compete in the building market. All of these developments ushered in a vibrant and dynamic opportunity for architectural experiments. The last two decades in Bangladesh witnessed an intense battle of architectural ideas. The earlier attitudes to orthodox modernism or regionalism in architecture dispersed into a more nuanced landscape of aesthetic abstraction.

SŠ: „For most of modern history, cities grew out of wealth. Even in more recently developed countries, such as China and Korea, the flight towards cities has largely been in line with income growth. But recent decades have brought a global trend for “poor-country urbanisation”, in the words of Harvard University economist Edward Glaeser, with the proliferation of low-income megacities.“ Dhaka is an example of such a city that has outpaced develepoment and has grown tremendously. Can planned urbanisation even tackle such a huge task in given circumstaces?

Adnan Morshed: While architecture rose and prospered as individual plot-based or stand-alone practices, cities—Dhaka as a glaring example—as a whole descended into unbearable chaos. In extreme cases, Taj Mahals coexisted with overflowing dumpsters. Private oases and sumptuous cafes overlooked the ghettoised world of slums. While architects searched for Bengali roots and global gravitas in their work, they mostly failed to promote an “ethical” view of how city should function and treat all its citizens.

While globalisation went on with a cutthroat consumerist and neoliberal agenda, and architecture patronage benefitting from it, social inequality grew manifold. Architects seemed confused as to how architecture could or should also play mitigating roles in addressing the issues of social justice. Slums burned and architects rushed to the site with naïve, superficial aesthetic solutions without trying to understand the exploitative economic and political systems that blight society in the first place. The feeling that “architecture is great but the city rots” sometimes seems overwhelming.

Walking in some of Dhaka's walkable streets fronted with exclusive-looking buildings, an observer might wonder how architecture could showcase the rising stature of a developing country, while failing to play a role in making it socially just.

_

In Croatian: https://vizkultura.hr/intervju-adnan-morshed/

_

Projekt Motel Trogir u 2021. godini podržan je od Ministarstva kulture i medija Republike Hrvatske i Zaklade Kultura nova.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOMA 37: Forgotten Greece

Forgotten Greece Masterpieces are obscure and understated, but still special in their own subtle way: it is the lack of fanfare, a certain restraint in the architecture that accentuates their genuine character, therefore they merit a closer look.

Concrete arches of Magoula Cemetery emanate an aura of Aalto’s wave designs or elements of Niemeyer’s Brasilia | Photo by Exporabilia

Each space comes with an interesting backstory and an evidence of how post-war ambition and civic pride fuses with classical tradition, science, folklore, religion and the natural environment. There is also an evidence of architectural brilliance mired in political persecution, indifference, schadenfreude or a lack of recognition by the establishment. Such storylines are as quintessentially Greek as drama and each might weave their unique pattern into the architecture.

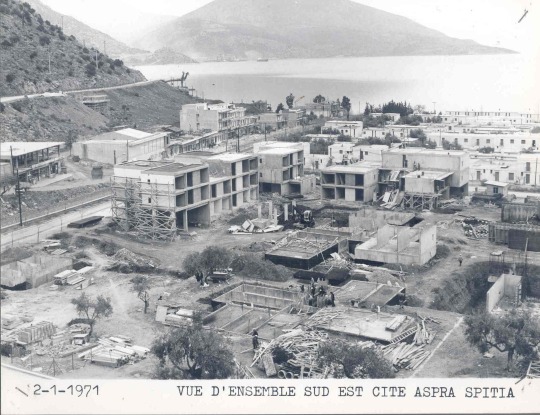

Aspra Spitia is a settlement to house employees of the Aluminum of Greece factory and mining operations west of Athens. | Photo via Fotiadis

Greeks demonstrated an innate affinity for siting and orientation since their temple building days of antiquity. Stillwell (1954) describes a mastery of form, angle, height and orientation: their temples were a planned succession of experiences that culminated into a grand, final approach of the cult image. Temple construction was an early use of architecture and urban planning principles to deliver a coherent visual and emotional result - exempli gratiaa transcendental, religious experience.

youtube

In post-war Greece, architect and urban planner Constantinos Doxiadis drew inspiration from the same fountain of knowledge. He created a seminal worker’s settlement that both transcended the provincial vernacular andchimed in fascinating consonance with its natural surroundings. It is like a place of eternal youth by design like Logan’s Run Caroussel), where residents never get to grow too old.

The construction phase on of Aspra Spitia. | Photo via © Doxiadis

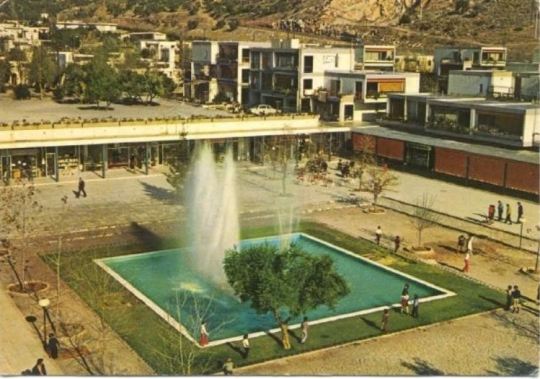

Through Ekistics, Doxiadis approached settlements as complex biological organisms. | Photo via Voiotias

Aluminum of Greece was launched in 1960 as a joint venture between the government of Greece and an industrial conglomerate led by the historic French firm Pechiney, a world leader in aluminum manufacturing. As a result, the first aluminum production facility in the country opened on the northern coast of the Corinthian Gulf in 1966. Capitalising on the nearby bauxite ore mines (one of the largest deposits in Europe), the vertically integrated manufacturing process ranged from raw material extraction to the delivery of a range of secondary bauxite and aluminium by-products. It was an ambitious and successful industrial project that created new opportunities for employment for those prepared to settle there. The sheer scale of the industrial unit and its ancillary facilities, however, created an urgent need for housing the employees, prompting the creation of a new settlement nearby. They called it Aspra Spitia (White Houses), and to this day, it remains a model for small scale urban planning with a unique blend of Modernist yet distinctively traditional Greek aura.

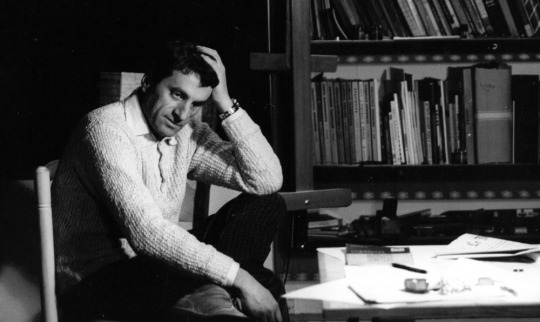

Constantinos Doxiadis in 1975

The urban planning, layout and design of the settlement was masterminded by Constantinos Doxiadis and his associates, who also delivered the first phase of the project. Doxiadis, an experienced urban planner who held various Public Works related government posts for the Greek government between 1937 and 1951, was a leading figure in the country’s post-war reconstruction effort. His private practice has been rising in international prominence since it was founded in the early 1950s; by 1959, he was appointed as chief urban planner for the city of Islamabad, Pakistan, while his firm was involved in numerous local and international projects, prompting him to construct a new headquarters in Athens to house their now 400 strong team of urban planners, architects, and engineers.

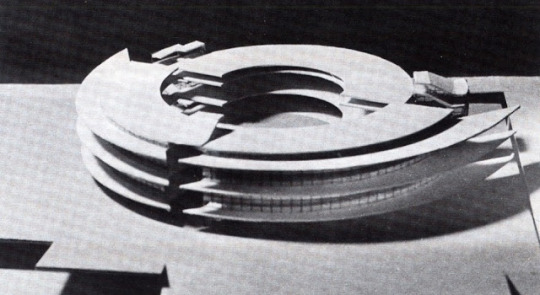

The model for Aspra Spitia. | Photo via © Doxiadis.org

Still, Aspra Spitia was a challenging brief: there was nothing but olive trees and a few vernacular shacks inside the tiny seaside valley. The first wave of French engineers settling at the newfound community were disheartened: this rugged slice of paradise had yet little to show in the way of creature comforts. And there was a looming danger in choosing to deliver a typical, prefab industrial settlement, with identikit housing units built around amenities: that choice of plan was expected to mark the marvellous landscape irreparably, presenting an unsuitable urban continuation of the industrial landscape at the nearby factories and mines. The new resident workers might feel disconnected, transient, and without a sense of belonging to the very habitat they might end up spending their entire career.

A commercial centre Tower | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

However, Doxiadis had a clear vision about Aspra Spitia. His plan was informed by his Ekistics philosophy, first proposed in 1942 and constantly developed since. Through Ekistics, Doxiadis approached human settlements as complex biological organisms - capable of forming connections with each other, constantly evolving, merging and scaling in orderly harmony with the natural environment. And preserving the purity and beauty of the hills, the seafront, and the olive tree fields within the planning scope of a factory, mines and a worker’s settlement at Aspra Spitia became a key challenge. These very different, both natural and man-made constituent units demanded to be re-shaped into a natural fit. This wouldn’t be about forcing an irreverent, modern smudge in the landscape: it’d be about the foundation of an orderly, organic urban environment.

A corner unit of the Phase 1. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

Stairs from the Phase 2. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

Units from the Phase 2. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

Thankfully, Doxiadis’ Ekistics already proposed such a scalable hierarchy for ordering urban settlements – an arrangement that social and biological sciences concluded was important for the avoidance of chaos. And at the beginning of the scale, there was Anthropos – the individual. It was expected that the aluminium workers would be mostly recruited from the nearby rural areas. Therefore, understanding the familiar traditions those new settlers were expected to carry with them was a crucial design element, as well as preserving the individuality of each constituent unit: each house, each cluster, each neighbourhood had to feel fresh and special, but still flow with identifiable tradition and heritage, also retaining a degree of deference to the natural environment. And the whole ensemble needed to remain functional for its intended purpose, without reverting to picturesque anachronisms.

All these elements were carefully infused into the inverse L-shaped city plan, which follows the organic contour of the landscape closely: The long leg is flanked by hills, while the short leg is laid across the seafront. Within the resulting space, four neighbourhoods were created, each circled by a peripheral road. The civic, business and administrative forum of the city is located at the junction of the legs, while a recreation and tourism area is laid along the seafront.

The settlement’s main square.

The design of the residences and public spaces is where it all comes together. Twelve unique house designs were utilized, each standardized with interchangeable elements that enabled the architects to alter the design in intermediate stages of construction. This technique increased the resulting variety of house types to twenty-five, while further variations were achieved by mixing-up the properties of each street in terms of house orientation, elevation, set back, and corner placement. Therefore, each home and each neighborhood look unique, but also retains a thematic familiarity with the whole ensemble of the town.

Both natural and modern materials are utilized, concrete, wood and local stone. The walls and stone are mostly whitewashed, offering a traditional Greek visual clarity to the settlement. Some stone walls remained natural with intent, in cases where these blended visually with the surrounding olive groves. The preservation and integration of existing olive trees in squares, yards and street layouts was prioritised, and supplemented by re-planting as well as new plantings. Stone fences, pergolas, steps and pavements complete the textured landscaping of each neighborhood, while well placed cul-de-sacs, squares and public thoroughfares complete the harmonious balance of private and public spaces.

Stairs from the Phase 3. | Photo via © Photiadis.gr

Aspra Spitia was completed in three phases, and now boasts 1072 residences housing approximately 3.000 residents. After the completion of the first houses and amenities by Doxiadis Associates, the city expanded both vertically and aesthetically with additions by C.Lembessis, P.Massouridis and M. Photiadis. A series of high rise, larger apartment blocks as well as specific amenities for the individual needs of the workers and the families were erected. These include a business centre, a nursery, and even a Catholic church for servicing the religious needs of the French settlers. One of the most ground breaking amenities was the installation of a sewage water treatment plant, which was the first of its kind in Greece at the time.

A series of specific amenities for the individual needs of the workers and the families were erected, like the nursery. | Photo via © Photiadis.gr

In terms of administration, Aspra Spitia is not far from the purpose-built, model socialist towns of the former Eastern Block. The settlement belongs to Aluminium of Greece (AL), and working in the mines or factories is a prerequisite for obtaining a house or a flat. A point system exists to help fulfil housing needs accurately, allocating the right type of property per household size. Residents are only required to pay a token monthly rent, while all property maintenance and upkeep is handled by the company. Naturally, these privileges last only for the duration of employment. Workers who wish to move on to another company or reach retirement age aren’t eligible to stay anymore: they are required to vacate their house, after making all necessary alternative arrangements. This is a town where people are not expected to grow old, and the reason why a cemetery was never planned as part of the urban grid (the nearest ones can be found in surrounding villages).

If Ekistics is about approaching urban environments in biological terms, then Aspra Spitia possibly holds the secret for urban immortality: free from the mortal vestiges of permanence and ownership, this is a model town that is, and will remain as fresh and tidy as planned over half a century ago.

The Church. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

The next stop is a few miles across the water from Aspra Spitia, where a forgotten Isthmia Prime Motel presents an abstract expression of three Classical disciplines: architecture, mathematics and music.

The unassuming roadside motel by the Isthmus of Corinth is an intriguing cross between Brutalism and the Classical Orders. | Photo by © Exporabilia

In its heyday, the main motorway linking the greater metropolitan area of Athens to the city of Corinth in the south west was one of the busiest arteries in Greece's road network. Built between 1960 and 1969, the motorway would hug the craggy cliffs outside the capital with its narrow ledge, offering breath-taking, and somewhat dangerous views of the sea below. Vehicles would naturally slow down at the Isthmus of Corinth, the canal that allowed shipping to navigate the strip of land connecting the Peloponnese to Attica. The slow crossing of the Isthmus Bridge enabled passengers to admire the view of the man-made chasm below, and traditionally led to a quick pit stop on the other side of the canal.

The Isthmus region was becoming a very popular weekend escape with Athenians post war. At about one hour drive from the capital, it was near, yet far enough to enjoy the sea and fresh air. Small villas and seaside hotels sprang out in local villages and hamlets for weekenders to escape the hustle and bustle of a rapidly urbanizing Athens.

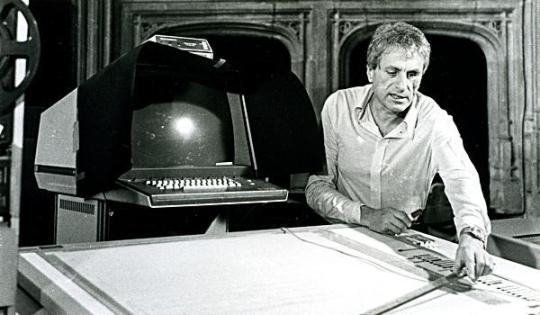

Panos Spiliotakos presenting his work. | Photo via © ema-arch.com

It is at this popular stopover area past the canal, where the strangely alluring hotel was built in 1969 in a collaboration between composer Iannis Xenakis and urban planner Panos Spiliotakos, two visionary friends expressing their common architectural heritage.

Iannis Xenakis | Photo via © Adelmann Collection of Françoise Xenakis

Xenakis was perhaps the most well-known of the duo. He was a Greek multidisciplinary artist with a passion for music and engineering and an unquestionable aptitude in both. He survived the war suffering a terrible face wound - caused by shrapnel from a shell fired by a British tank into a crowd of Communist protesters demonstrating in the streets of Athens in December 1944. As a qualified engineer, he left for Paris in 1947 where he worked under Le Corbusier at the Unite D'Habitation and Convent De La Tourette.

Le Corbusier with Iannis Xenakis. | Photo © Iannis Xenakis

During that period, and through his own musical culture, Xenakis soon realised that the same complex spatial geometrical patterns applied in Le Corbusier's architecture - the structural calculations, the intersecting tones and curves - could be applied to the composition of music too. His seminal 1955 musical work Metastaseis (lit.transmutations) was inspired by Einsteinian ideas about time and space, and utilised the mathematical principles of the Fibonacci sequence and the Golden Section structured around Le Corbusier's architectural calculations. It shocked the world of contemporary music at the time: this was original Brutalist music, with all the sonic cantilevers, rebar and board marking you could handle.

youtube

The Algorithmic Compositions of Metastaseis

Xenakis' knowledge of architecture allowed him to use graphic notation to represent his music. The string glissandi and other musical motions of his piece, representing sonic beams with time on one axis and pitch on another, looked less like sheet music, and more like a blueprint. With Le Corbusier occupied in the construction of Chandigarh in India, Xenakis went on to design the Phillips Pavilion in Brussels Expo 58 on his behalf. It's a unique marriage of music and architecture, with its hyperbolic paraboloid masses deriving from the musical landscape of his own Metastaseis.

Inside the Pavilion, an expansive array of speakers and dials were arranged in an acousmonium: an avant-garde playback device used to spatialize musical scores. The array had been invented in the 1940s by proponents of musique concrète, an experimental circle of composers with whom Xenakis was associated. Further musical scores by Xenakis and Edgard Varese were performed this way throughout the pavilion, creating a unique meta-experience that fused architecture and music like never before.

The Phillips Pavilion in Brussels Expo 1958. | Photo © Wouter Hagens

True to the genius of Iannis Xenakis, the building by the Corinthian Isthmus emanates a classical aura throughout. Built as a modern diversorium (a roadside inn), it reflects the long Graeco-Roman resort heritage of the area. The sulphur baths at nearby Thermae (today's Loutraki) attracted visitors since the antiquity. Many classical villas and baths have been discovered in the region through the years. It makes perfect sense that Isthmia Prime's characteristic main entrance colonnade is made of 12 stern, board-marked concrete columns, a Modernist throwback to the Doric order of the nearby Temple of Apollo. The colonnade is supporting the 3-storey main residential block, with the rooms arranged obliquely to the main axis to maximise the beautiful views of the Gulf of Corinth beyond.

The colonnade is supporting the 3-storey main residential block, with the rooms arranged obliquely to the main axis. | Photo by Exporabilia

The triangular concrete antefixeson the flat roof is another wink to the floral anthemiaof antiquity, the decorative palmettes that adorned the eaves of ancient Greek and Roman buildings. The block is intersected by the reception and services area at ground level, allowing for a practical green area at the front with a star shaped pond. Iannis Xenakis reminded us that rhythm, as symmetrical repetition, is the ancient, supernatural bond that links mathematics, music and architecture. Isthmia Prime is an elegant, if somewhat forgotten example of these classical and artistic traditions, fused expertly together with his characteristic elan.

The building at Corinth is a Modernist throwback to certain familiar artistic traditions of Classical antiquity. At the corollary of this Athenian-centric luminary ethos, there’s a counterpart a Spartan-centric ethos, founded on the principle of selfless sacrifice as the pinnacle of civic achievement. Naturally, there’s less opportunity to go down fighting under a hail of arrows in our day. But dedicating one’s life in the service of the state is here presented as a visual metaphor of Sparta’s finest traditions in the Modernist Necropolis of Magoula.

The waveform of the Magoula Cemetery is symbolic of the up's and downs we go through life. | Photo by Exporabilia

The new city of Sparta was founded in 1834 at the behest of Otto, the Bavarian prince who became the first King of Greece in the aftermath of the nation’s successful war of independence. He embarked on a revivalist program that aimed to modernize and urbanize Greek towns. The project was led by Eduard Schaubert,a Prussian architect and topographer who studied under Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin’s Bauakademie. Schaubert also re-designed Athens, Pireaus and other major Greek cities, finely tuning their plethora of Classical and Byzantine sites with the Neoclassical neighborhoods, squares, and administrative buildings that typified the Greek national revival. This is how Sparta, previously obliterated by the Goths in the 4thcentury, was restored by royal decree in 1837. The re-established Sparta became, in fact, the first of the new Greek towns whose design was based on an actual urban plan – thus breaking with the disorderly, vernacular yoke of medieval urban spaces.

A century later, Sparta remained a quaint agricultural town, virtually unchanged since Schaubert planned it. The beautiful neoclassical facades were crumbling, and the street grid had deteriorated and was unsuitable for the ever-increasing motor vehicle traffic. The sewage system was old, and problematic. What’s more, modern Sparta was a city with a distinctive lack of modern facilities and monuments – it was becoming lethargic, almost as if the Goths had somehow travelled forward in time, sacking it again into oblivion.

There are entrances to either end of the arches, one leading to a small functions area, and another to the ossuary. | Photo by Exporabilia

The man who changed all that was Georgios Sainopoulos, the philanthropist who became mayor of Sparta for two terms, over a period of 8 years between 1964 and 1978 (interrupted by the Colonels’ Junta, who ousted him between 1967 and 1974). Sainopoulos dedicated his life to the improvement of urban life in Sparta, delivering numerous projects related to sport and cultural facilities, new road & water network infrastructure, and monumental public art. The 1964 cemetery at the satellite hamlet of Magoula was created at his behest - this was his birthplace, and where he seemed to make an almost personal statement about his intention to take the city out of its enduring quagmire, and into an era of progress. The cemetery, alongside other luminary philanthropic projects, was realised via donations he secured from close relatives Ioannis and Catherine Sainopoulos, Greek emigres based in Oklahoma, USA. He then invited local architects Charilaos and Sophia Polychronopoulos to deliver his vision of a surprising modern necropolis that exceeded conventional expectations.

Windows reflect the bright Peloponnesian sunshine in the colors of the CIAM grid green, red, yellow and blue, creating a kaleidoscope of colours inside the space where the funerary chests are kept. | Photo by Exporabilia

Sainopoulos might have been informed by his own experience of monumental modernism as a visitor during the Olympic games of Helsinki in 1952. It would have been an inspirational showcase of Nordic Modernism, exemplifying Olympic ideals, and much of it can still be admired to this day. The waveform these arches form at Magoula is said to be symbolic of the ups and downs we experience throughout life. There are entrances to either end of the arches: one leading to a small functions area, and another to the ossuary, both decorated with saints and religious figures made out of bent rebar. The windows reflect the bright Peloponnesian sunshine in the colours of the CIAM grid: green, red, yellow and blue, creating a kaleidoscope of colors inside the space where the funerary chests are kept.

Ancient Spartan traditions exemplified order and simplicity in all aspects of life, which often carried into funerary rites. Spartans were buried among the living, in anonymous graves inside the city walls. Only those fallen in battle, or women dying in childbirth were deemed important enough to merit their names on gravestones, typically lined up along busy thoroughfares & promenades – therefore transforming their tombs into public monuments. Further inside the Magoula cemetery proper, it is evident that several graves have been created in deviation to the unremarkable, marble-clad basilica orthodoxy of Greek cemeteries: the scale, shapes and materials are different, and there are statues, busts, carvings and funerary symbols that simultaneously reflect a sense of civic grandeur, and a closer affinity to the Western European funerary canon.

Shapes and materials of graves are different, statues and symbols reflect a closer affinity to European funerary traditions. | Photo by Exporabilia

Leonidas, the famous king who fell in Thermopylae was perhaps the most well-known son of Sparta. It is said that his remains were posthumously transferred to Sparta and deposited at Leonideon, a rectangular tomb close to the agora that can still be seen today. And as opposed to the more modern, extra muros Roman burial traditions, there’s consequence in the way that the tombs of all true citizens become very much a part of the living urban space. But especially the tombs of those who, like Leonidas, contributed significantly more to perpetuate the lore of their communities, become monuments of civic pride, and public remembrance. Uniquely, Sainopoulos' own resting place is a sizeable vault, accessible through a flight of steps near the entrance to the cemetery. It is a feature rarely - if ever - seen in contemporary Greek cemeteries, and underlines the important character of the site’s mastermind. Arguably, this space represents a somewhat obscure link between the principled simplicity of the Spartans and the visual clarity of Modernist architecture. Deciphered in the key of the region’s Spartan heritage, the beautiful ensemble at the cemetery of Magoula is so much more than the average burial site usually seen in Greek towns : it is a poignant memorial showcase of lives well lived in the service of the local community, beautifully conveyed through the avant-garde architectural mind set of the 1960s.

An eclectic, monumental ensemble that fuses Classical, Byzantine and Romantic architectural styles. | Photo © M. Hulot

The civic principles of the Hellenistic world eventually clashed with the tenets of Christianity. In Greece this tectonic collision created new philosophical and artistic planes that inadvertently radiated their common roots, despite the necessities of doctrinal contrasts. Understanding this blend is quintessential to understanding the modern Greek psyche. The temple of Agia Foteini of Mantineia is the ideal visual representation for this melding process.

In the sunlit Arcadian plain close to the ancient city of Mantineia, there’s a church like no other. It’s an astonishing melange of styles, combining elements of Classical, Byzantine and Modern architecture, and yet remaining true to none. Its construction is the life’s work of architect and iconographer Kostas who has delivered an epic display of drama, faith and devotion that has astonished and divided ever since.

Heroic Tomb, Jacob’s Well and the Church’s Entrance. | Photo © M. Hulot

Papatheodorou was exposed to gothic religious architecture, particularly influenced by Erwin Von Steinbach's work in Strassbourg Cathedral. After his studies he returned to Greece in 1967, where he worked for the Ministry of Culture, studying further under the architect Dimitris Pikionis. During his tenure there, he was exposed to the idea of building a monumental church on behalf of the Mantineian Association, a cultural group dedicated to the preservation of the antiquities of Ancient Mantineia in the southern region of Peloponnese. Bewildered by the beautiful scenery, the majesty of the ancient site, and the character of local customs, he proposed the design of an extraordinary building that captured the region’s quintessence: a visual link among the Classical, Byzantine and Modern traditions of Arcadia.

A mosaic inside the church. | Photo © M. Hulot

He resigned his public service role in 1970 to dedicate himself to the project, which eventually became a lifelong commitment. No formal contract was drawn, funding was scarce, mostly based on charity grants and donations from locals and members of the Mantineian Association. Driven by an almost divine inspiration, Papatheodorou moved on location, living in a tent pitched next to the site. This way, he could absorb the spirit of the locality, and focus on the formative stages of the project unhindered. He was often seen roaming construction sites and recycling centres in nearby towns, gathering reject materials: cornerstones from demolished townhouses, leftover marble slab fragments, or broken clay tiles from old roofs. He worked mostly alone, collecting, measuring, chiselling the materials, shaping and piecing the fragments together into an astonishing monument that soon began taking shape. His only help was unskilled manual labour provided by local farmhands. The Classical and Byzantine parts and techniques merge into one another on the walls and bell towers of the church, creating a visual disruption that expresses the forward motion of history - as one era blends into another, leaving its indelible mark at the seams of history. The church becomes a visual representation of the area’s disparate yet interlinked memories, converging through the aeons to create a homogeneous body of local culture.

The main entrance. | Photo © M. Hulot

The main structure was completed by 1974, then the interior work began. Inside the church, we see the expression of the architect as an iconographer: The concept of stylistic variety continues, with sequences of religious and pagan themes combining on the mosaics and wall paintings. Classical symbolism such as meanders, pastoral or hunting scenes abound, and figures in ancient togas blend with Christian saints dressed in modern attire, such as jeans and t-shirts. It was too much for a portion of local clergy, who began raising eyebrows: certain offending visuals are then amended to avert the church being characterised as inappropriate for consecration. Conservative circles begin to gossip Papatheodorou, accusing him of irreverence and idolatry. Some others allege that he has unlawfully appropriated materials from the ruined temples and shrines of Ancient Mantineia to incorporate in his church.

But those who recognized and appreciated his work also lend their support – architects, archaeologists and art curators underlines the multidisciplinary reach of his work. The famous Greek painter Yiannis Tsarouchis described the church vividly as fresh water for those in thirst: “When I saw the church, I felt the elation one feels when a justified complaint is suppressed. I’ve heard people characterise Kostas Papatheodorou as an “aping architect”. What I found at the church, however, was a genuine heartbreak, a desperate confession. In our age of fake moralism and ludicrous rationalism, these rare qualities become as important as a vein of fresh water during drought”

The next few years saw the construction of two ancillary buildings, a miniature Classical shrine dedicated to local war heroes, and a fountain with a circular colonnade, representing the biblical fable of Jacob’s Well. The Church is considered work in progress to this day. Some contemporary critics stated that the Church of Agia Foteini of Mantineia is the Greek Sagrada Familia. This may be a somewhat flattering, even inflammatory characterisation for some. There are parallels, however, between the work of Antonio Gaudi and Kostas Papatheodorou as both churches are considered incomplete, both architects deployed their proficiency in a number of related disciplines, incorporating these in their design - ceramics and wrought ironwork for Gaudi, it’s iconography and mosaics for Papatheodorou. Gaudi pioneered the use of trencadís, his famous mosaics made of reject materials, broken tiles, shards of glass, china or shells. Papatheodorou employed a similar technique by fashioning reject materials - such as stones and tiles - as found into walls, towers and mosaics. Last, both architects are inspired by Gothic religious architecture, and they are driven and inspired by their faith, which leads them to wholly devote their lives in their work. Agia Foteini of Mantineia might not have the scale or monumental appeal of the Sagrada Familia. It is however an equally unique spiritual monument, and an important symbol of the historic, cultural and religious ties that bind the people of Arcadia together.

Conceptual Scale Model of the Round School. | Photo © leximata

The resurgent Greek culture of the 19th century was inspired by the glow of its classical heritage, yet emerged fatefully disconnected from it. The impetus with which Greeks used to strive to make sense of what constitutes justice, of what makes an ideal community, or what is good governance - all philosophical questions explored in Plato’s Republic - had become secondary to the medieval moral and civic conventions of the late Byzantine era, and its disastrous outcomes. By the 20th century, a Neo-Hellenic culture has taken hold, characterised by romantic reminiscence, counterproductive self-pity, blind revanchism, and endemic corruption. Inside this purgatory, a vicious circle of astonishing success is always followed by stupefying failure, in an unplanned state of permanent complacency that is always attributed to certain fantastical others. It is a moral decline that Constantine Cavafis alluded to in his poem “Waiting for the Barbarians”, and is without doubt the starting point of the country’s recent string of financial and political failures.

Breaking this craven mould, Takis Zenetos was the Greek modernist architect who demonstrated unbridled optimism and progressive vision through his work. He has a rightful place in my obscure pantheon, another important 20th century personality that epitomized the virtue of living up to one’s own high standards of moral and civic duty.

Round School top down view. | Photo © Dimitris Vosios

Agios Dimitrios (often referred to with its pre-1928 name, Brahami) is one of the most densely populated suburbs of Athens with a density comparable to Cairo or Seoul. The typical expedience and maladministration that characterized post-war Greece has left its indelible mark in the suburb’s architecture: its arbitrarily arranged streets define pocket upon pocket of unimaginative apartment blocks that connect to those of surrounding suburbs to form a veritable sea of concrete and tarmac. This is the result of the “flats for land” legislation of 1929, which enabled owners to give up their neoclassical houses in return for a flat or two in the uninspiring concrete tenements and high rises that soon began to blot out the quaint early 20c. suburban landscape. The desperate measure was initially brought in to manage the pressing housing needs of destitute immigrants from Asia Minor in the 1920s and 1930s. The 1.6 million displaced were joining a country of 5 million. This summary convenience was extended to solve later rapid urbanisation problems, such as the Axis occupation and its aftermath. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, people fled the Civil War and the prospect of a hard life in their devastated villages and sought a better future in the capital, whose extant high density infrastructure had been equally ruined in a month of tenacious urban confrontation between Communist guerrillas and Government forces (the Decembriana of 1944).

The new architecture principle is educational autonomy, its curves disrupt the sea of high rise blocks that surround it. | Photo © Thomas Andreopoulos

This short term, anarchic character of Greece’s urban planning mentality was deeply troubling for Takis Zenetos. Born and active in Athens for most of his life, he must have witnessed the entire devastating process first-hand: the consequence of conflict in the capital’s urban grid, coupled with the inexcusable sloppiness of the state managing it. The occupation interrupted his studies at the National Technical University (the Metsovion), but in 1945 he moved to Paris to continue at the Ecole Des Beaux Arts under Otello Zavaroni. He was influenced by the order and principles of Modernist architecture in France, before coming back to Athens to practice in 1955. For the next decade, Zenetos designed and built sensational, distinctively Modernist factories, apartment blocks and private villas, always in partnership with his friend Margaritis Apostolidis.