#eastern wei dynasty

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Ancient Tombs Discovered in China's Henan

A cemetery found in Zhucang Village in Mengjin District of Luoyang City, central China's Henan Province. A cemetery consisting of three tombs was recently listed as one of the five key archaeological discoveries in Henan Province in 2022. In the tombs probably built between the late period of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) and the Eastern Wei Dynasty (534-550), large-scale and well-organized stone beds with stone folding screens were found. This is the first time that stone beds dating back to this period have been unearthed in Luoyang City.

#Ancient Tombs Discovered in China's Henan#ancient tombs#ancient graves#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient china#chinese history#northern wei dynasty#eastern wei dynasty

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

【Historical Artifacts Reference 】:

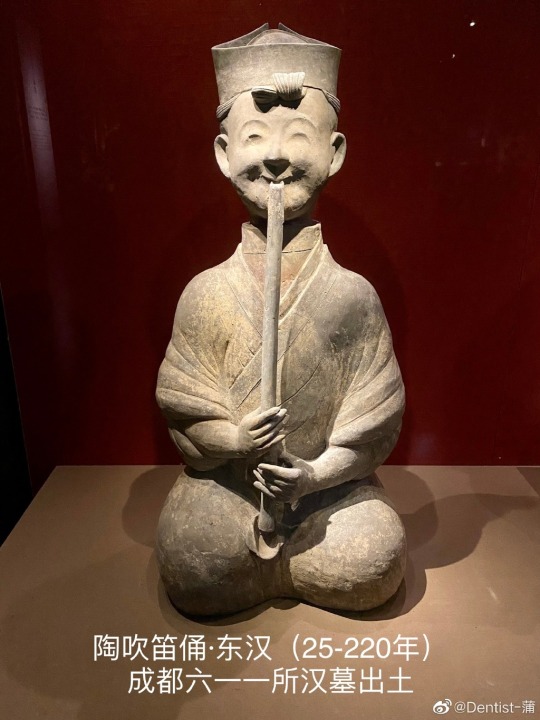

China Eastern Han Dynasty Playing Qin Pottery Figurine

China Eastern Han Dynasty Playing the Dizi(Chinese flute) Pottery Figurine

China Wei and Jin Dynasties "person who conveys official documents and letters" Mural Bricks

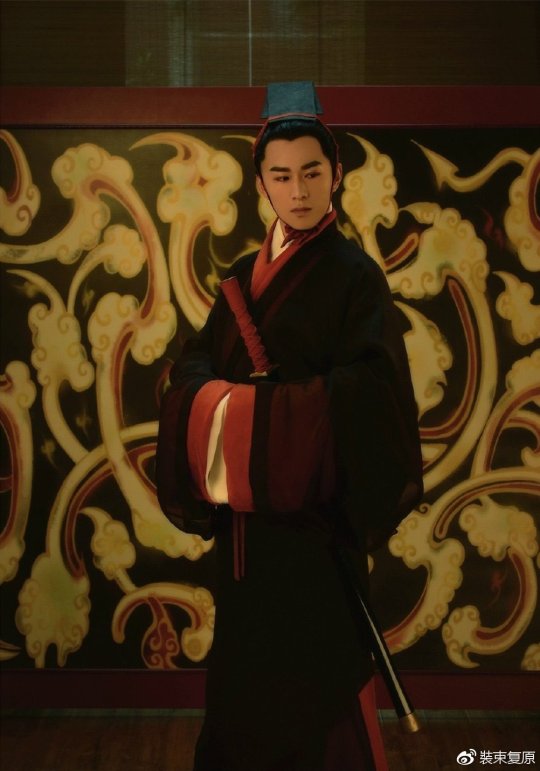

[Hanfu・漢服]Chinese Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 A.D.) Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Headwear

—–

【History Note】

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, men's attire was usually wider than the Western Han Dynasty period, which was more convenient for activities.The collocation of wearing Jie Zhi(介帻) and straight train robes(直裾袍服) is favored by scholars at the time.

This set of attire for the scholars/literati of the Eastern Han Dynasty is wearing a Jie Zhi /介帻 on head, with a purple brocade border cotton robe, red silk cotton trousers, waering a yellow gauze on the outermost layer, and a brocade pouch around the waist.

At the time, the fashion of wearing gauze robe was still popular, which looked elegant and dignified, without losing the beauty of agility and elegance.

This set of attire has existed among the literati until the Wei and Jin Dynasties.

————————

📝Recreation Work ��� @裝束复原

👗 Hanfu: @桑纈

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1656910125/MdvaOoRei

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 A.D.)#hanfu#hanfu history#hanfu accessories#chinese traditional clothing#chinese historical fashion#chinese history#Chinese Costume#chinese costume history#Chinese Culture#artifacts#Wei and Jin Dynasties#裝束复原#桑纈#漢服#汉服#Jie Zhi(介帻)#直裾袍服

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

INTERESTING

men’s hanfu

line 1 - line 5 :Han Dynasty

line 1 - line 3 : Western Han

line 4 - line 5 :Eastern Han

line 6 : Wei and Jin Dynast

line 7 - line 8 : Northern Song Dynasty

#hanfu#mens hanfu#mens headwear#hats#runway#history#reference#Han dynasty#western han dynasty#Eastern Han dynasty#wei/jin dynasties#Song dynasty#Northern Song#Coser小梦

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cryptic Motif of “Three Hares with Conjoined Ears”

On the Heavenly Palace decorative patterns found in the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang from the late Northern dynasties are images with cryptic patterns, including Buddha's head, the Taotie beast, deer, animals copulating, three hares with conjoined ears, and also writings. This type of decorative pattern is cryptic and difficult to understand and may be closely related to the history of the popular Eastern iconology and divination philosophy from the Han and Wei dynasties and Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou's suppression of Buddhism. They are important references for studying the related history of this period.

#china#motif#three hares with conjoined ears#silk road#culture influenced by buddhism from ancient india#art#reference

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

April 14, Xi'an, China, Shaanxi History Museum, Qin and Han Dynasties Branch (Part 3 – Innovations and Philosophies):

(Edit: sorry this post came out so late, I got hit by the truck named life and had to get some rest, and this post in itself took some effort to research. But anyway it's finally up, please enjoy!)

A little background first, because this naming might lead to some confusions.....when you see location adjectives like "eastern", "western", "northern", "southern" added to the front of Zhou dynasty, Han dynasty, Song dynasty, and Jin/晋 dynasty, it just means the location of the capital city has changed. For example Han dynasty had its capital at Chang'an (Xi'an today) in the beginning, but after the very brief but not officially recognized "Xin dynasty" (9 - 23 AD; not officially recognized in traditional Chinese historiography, it's usually seen as a part of Han dynasty), Luoyang became the new capital. Because Chang'an is geographically to the west of Luoyang, the Han dynasty pre-Xin is called Western Han dynasty (202 BC - 8 AD), and the Han dynasty post-Xin is called Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD). As you can see here, in these cases this sort of adjective is simply used to indicate different time periods in the same dynasty.

Model of a dragonbone water lift/龙骨水车, Eastern Han dynasty. This is mainly used to push water up to higher elevations for the purpose of irrigation:

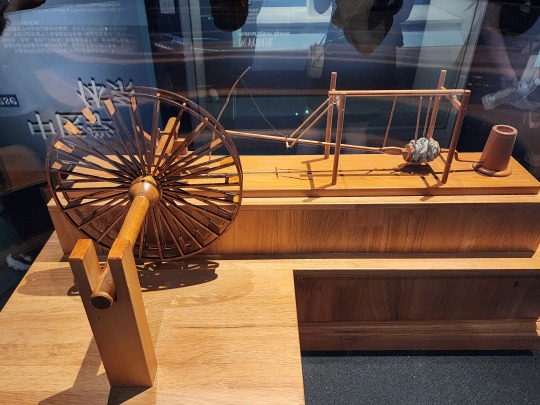

Model of a water-powered bellows/冶铁水排, Eastern Han dynasty. Just as the name implies, as flowing water pushes the water wheel around, the parts connected to the axle will pull and push on the bellows alternately, delivering more air to the furnace for the purpose of casting iron.

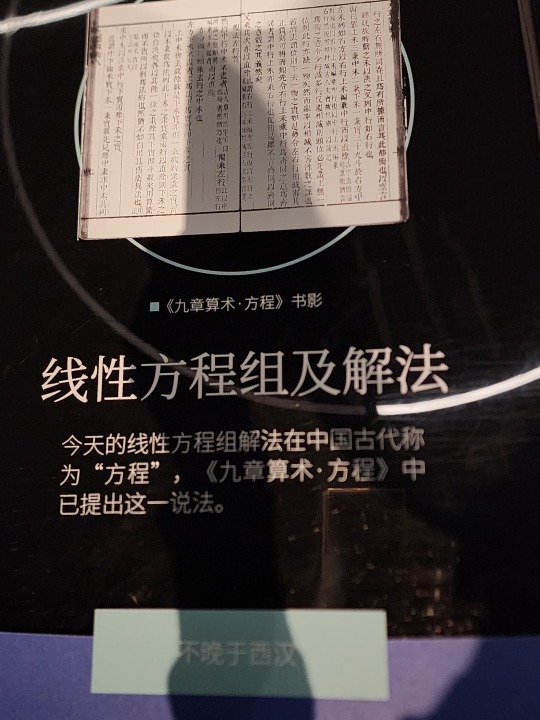

The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art/《九章算术》, Fangcheng/方程 chapter. It’s a compilation of the work of many scholars from 10 th century BC until 2 nd century AD, and while the earliest authors are unknown, it has been edited and supplemented by known scholars during Western Han dynasty (also when the final version of this book was compiled), then commented on by scholars during Three Kingdoms period (Kingdom of Wei) and Tang dynasty. The final version contains 246 example problems and solutions that focus on practical applications, for example measuring land, surveying land, construction, trading, and distributing taxes. This focus on practicality is because it has been used as a textbook to train civil servants. Note that during Han dynasty, fangcheng means the method of solving systems of linear equations; today, fangcheng simply means equation. For anyone who wants to know a little more about this book and math in ancient China, here’s an article about it. (link goes to pdf)

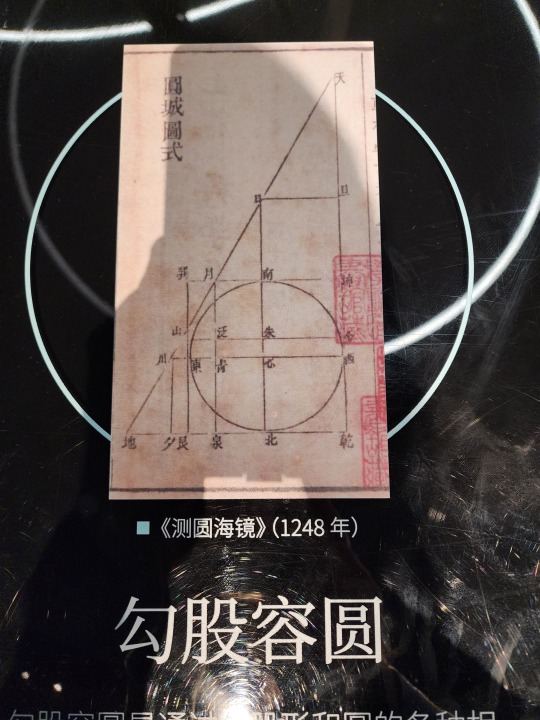

Diagram of a circle in a right triangle (called “勾股容圆” in Chinese), from the book Ceyuan Haijing/《测圆海镜》 by Yuan-era mathematician Li Ye/李冶 (his name was originally Li Zhi/李治) in 1248. Note that Pythagorean Theorem was known by the name Gougu Theorem/勾股定理 in ancient China, where gou/勾 and gu/股 mean the shorter and longer legs of the right triangle respectively, and the hypotenuse is named xian/弦 (unlike what the above linked article suggests, this naming has more to do with the ancient Chinese percussion instrument qing/磬, which is shaped similar to a right triangle). Gougu Theorem was recorded in the ancient Chinese mathematical work Zhoubi Suanjing/《周髀算经》, and the name Gougu Theorem is still used in China today.

Diagram of the proof for Gougu Theorem in Zhoubi Suanjing. The sentence on the left translates to "gou (shorter leg) squared and gu (longer leg) squared makes up xian (hypotenuse) squared", which is basically the equation a² + b² = c². Note that the character for "squared" here (mi/幂) means "power" today.

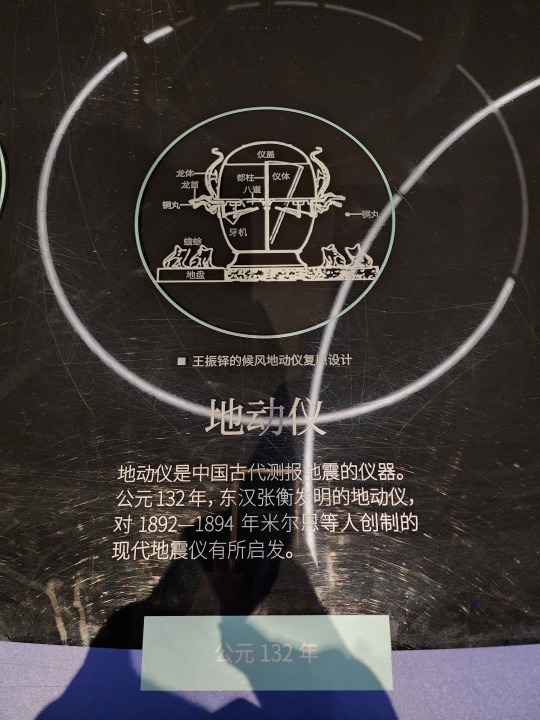

This is a diagram of Zhang Heng’s seismoscope, called houfeng didong yi/候风地动仪 (lit. “instrument that measures the winds and the movements of the earth”). It was invented during Eastern Han dynasty, but no artifact of houfeng didong yi has been discovered yet, this is presumably due to constant wars at the end of Eastern Han dynasty. All models and diagrams that exist right now are what historians and seismologists think it should look like based on descriptions from Eastern Han dynasty. This diagram is based on the most popular model by Wang Zhenduo that has an inverted column at the center, but this model has been widely criticized for its ability to actually detect earthquakes. A newer model that came out in 2005 with a swinging column pendulum in the center has shown the ability to detect earthquakes, but has yet to demonstrate ability to reliably detect the direction where the waves originate, and is also inconsistent with the descriptions recorded in ancient texts. What houfeng didong yi really looks like and how it really works remains a mystery.

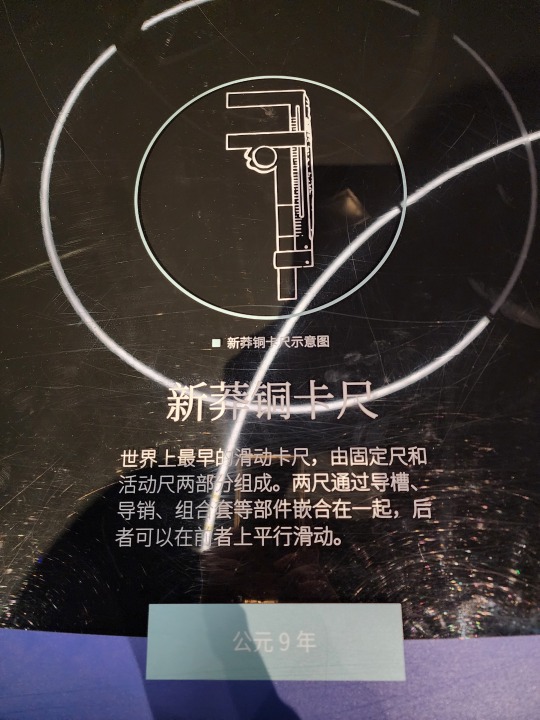

Xin dynasty bronze calipers, the earliest sliding caliper found as of now (not the earliest caliper btw). This diagram is the line drawing of the actual artifact (right).

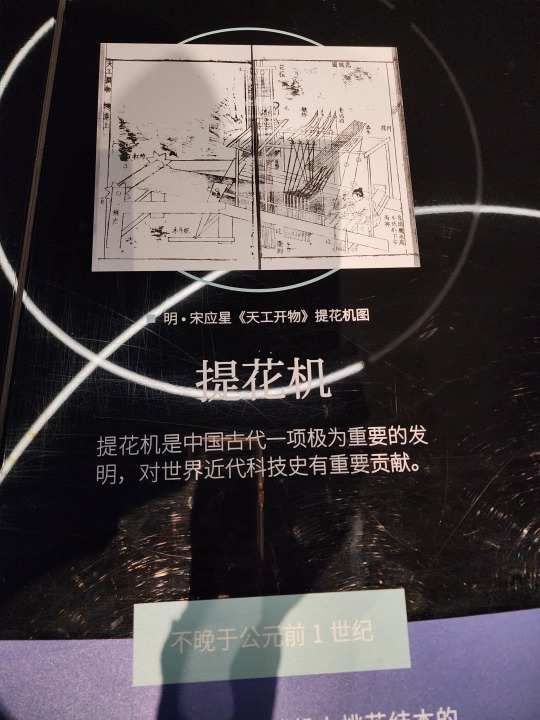

Ancient Chinese "Jacquard" loom (called 提花机 or simply 花机 in Chinese, lit. "raise pattern machine"), which first appeared no later than 1st century BC. The illustration here is from the Ming-era (1368 - 1644) encyclopedia Tiangong Kaiwu/《天工开物》. Basically it's a giant loom operated by two people, the person below is the weaver, and the person sitting atop is the one who controls which warp threads should be lifted at what time (all already determined at the designing stage before any weaving begins), which creates patterns woven into the fabric. Here is a video that briefly shows how this type of loom works (start from around 1:00). For Hanfu lovers, this is how zhuanghua/妆花 fabric used to be woven, and how traditional silk fabrics like yunjin/云锦 continue to be woven. Because it is so labor intensive, real jacquard silk brocade woven this way are extremely expensive, so the vast majority of zhuanghua hanfu on the market are made from machine woven synthetic materials.

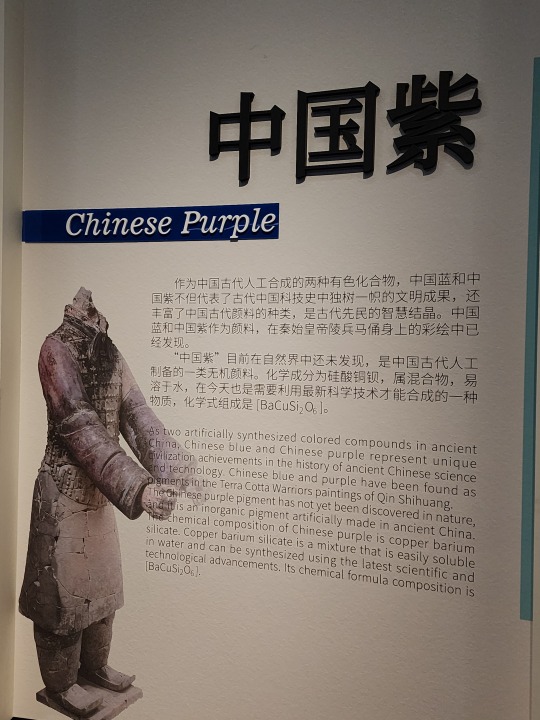

Chinese purple is a synthetic pigment with the chemical formula BaCuSi2O6. There's also a Chinese blue pigment. If anyone is interested in the chemistry of these two compounds, here's a paper on the topic. (link goes to pdf)

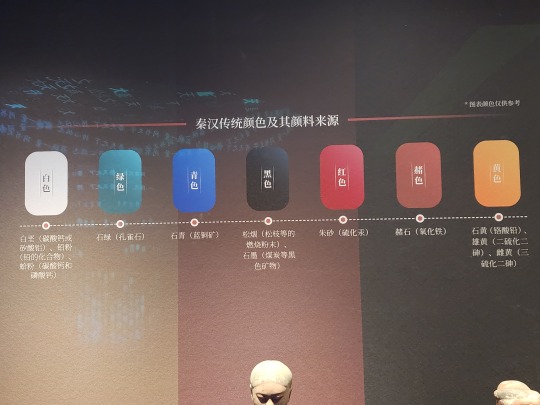

A list of common colors used in Qin and Han dynasties and the pigments involved. White pigment comes from chalk, lead compounds, and powdered sea shells; green pigment comes from malachite mineral; blue pigment usually comes from azurite mineral; black comes from pine soot and graphite; red comes from cinnabar; ochre comes from hematite; and yellow comes from realgar and orpiment minerals.

Also here are names of different colors and shades during Han dynasty. It's worth noting that qing/青 can mean green (ex: 青草, "green grass"), blue (ex: 青天, "blue sky"), any shade between green and blue, or even black (ex: 青丝, "black hair") in ancient Chinese depending on the context. Today 青 can mean green, blue, and everything in between.

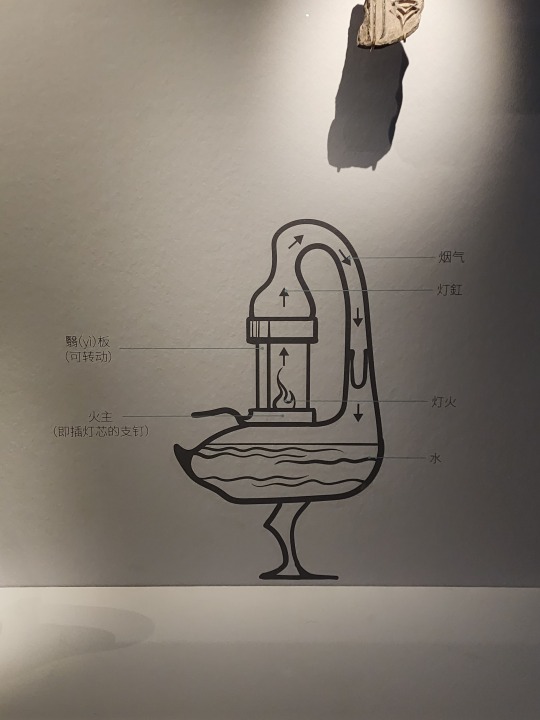

Western Han-era bronze lamp shaped like a goose holding a fish in its beak. This lamp is interesting as the whole thing is hollow, so the smoke from the fire in the lamp (the fish shaped part) will go up into the neck of the goose, then go down into the body of the goose where there's water to catch the smoke, this way the smoke will not be released to the surrounding environment. There are also other lamps from around the same time designed like this, for example the famous gilt bronze lamp that's shaped like a kneeling person holding a lamp.

Part of a Qin-era (?) clay drainage pipe system:

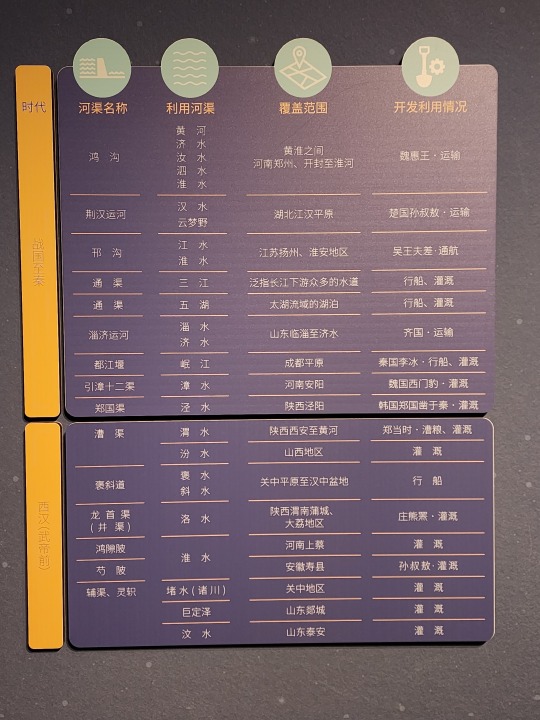

A list of canals that was dug during Warring States period, Qin dynasty, and pre-Emperor Wu of Han Han dynasty (475 - 141 BC). Their purposes vary from transportation to irrigation. The name of the first canal on the list, Hong Gou/鸿沟, has already become a word in Chinese language, a metaphor for a clear separation that cannot be crossed (ex: 不可逾越的鸿沟, meaning "a gulf that cannot be crossed").

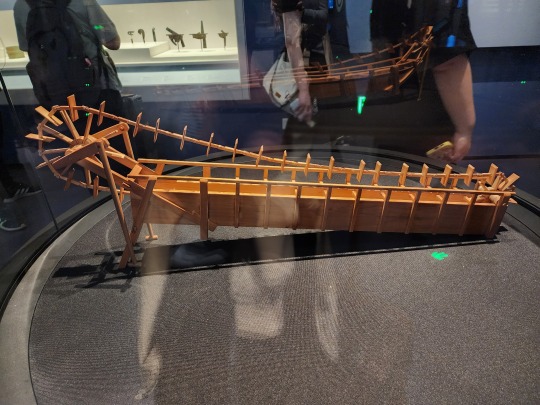

Han-era wooden boat. This boat is special in that its construction has clear inspirations from the ancient Romans, another indication of the amount of information exchange that took place along the Silk Road:

A model that shows how the Great Wall was constructed in Qin dynasty. Laborers would use bamboo to construct a scaffold (bamboo scaffolding is still used in construction today btw, though it's being gradually phased out) so people and materials (stone bricks and dirt) can get up onto the wall. Then the dirt in the middle of the wall would be compressed into rammed earth, called hangtu/夯土. A layer of stone bricks may be added to the outside of the hangtu wall to protect it from the elements. This was also the method of construction for many city walls in ancient China.

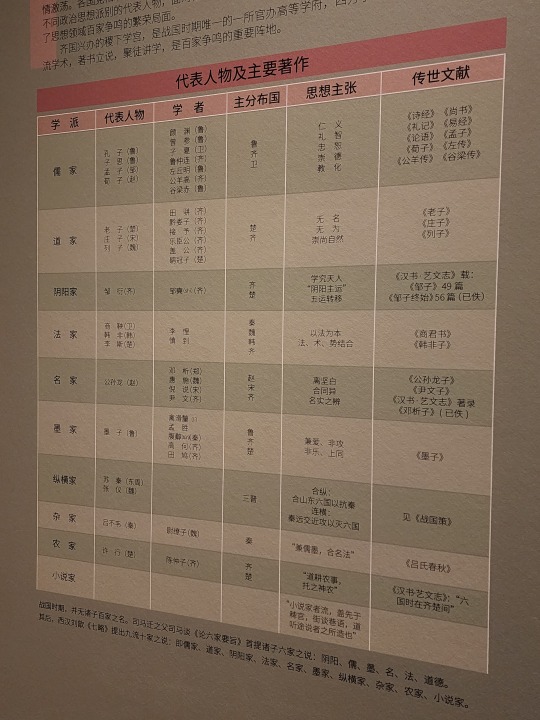

A list of the schools of thought that existed during Warring States period, their most influential figures, their scholars, and their most famous works. These include Confucianism (called Ru Jia/儒家 in Chinese; usually the suffix "家" at the end denotes a school of thought, not a religion; the suffix "教" is that one that denotes a religion), Daoism/道��, Legalism (Fa Jia/法家), Mohism/墨家, etc.

The "Five Classics" (五经) in the "Four Books and Five Classics" (四书五经) associated with the Confucian tradition, they are Shijing/《诗经》 (Classic of Poetry), Yijing/《易经》 (also known as I Ching), Shangshu/《尚书》 (Classic of History), Liji/《礼记》 (Book of Rites), and Chunqiu/《春秋》 (Spring and Autumn Annals). The "Four Books" (四书) are Daxue/《大学》 (Great Learning), Zhongyong/《中庸》 (Doctrine of the Mean), Lunyu/《论语》 (Analects), and Mengzi/《孟子》 (known as Mencius).

And finally the souvenir shop! Here's a Chinese chess (xiangqi/象棋) set where the pieces are fashioned like Western chess, in that they actually look like the things they are supposed to represent, compared to traditional Chinese chess pieces where each one is just a round wooden piece with the Chinese character for the piece on top:

A blind box set of small figurines that are supposed to mimic Shang and Zhou era animal-shaped bronze vessels. Fun fact, in Shang dynasty people revered owls, and there was a female general named Fu Hao/妇好 who was buried with an owl-shaped bronze vessel, so that's why this set has three different owls (top left, top right, and middle). I got one of these owls (I love birds so yay!)

And that concludes the museums I visited while in Xi'an!

#2024 china#xi'an#china#shaanxi history museum qin and han dynasties branch#chinese history#chinese culture#chinese language#qin dynasty#han dynasty#warring states period#chinese philosophy#ancient technology#math history#history#culture#language

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Not done with the Qin/Han robes yet, but taking a quick break to hop to the next time period for something a bit different.)

魏晋南北朝的襦裙 Ruqun (2-piece outfit) during the Wei-Jin + Northern/Southern Dynasties (220 - 589 AD)

This time period spans over 350 years and incorporates: 1) the Three Kingdoms era, 2) the Jin Dynasty, 3) the Northern/Southern dynasties

History background: Towards the end of the Eastern Han dynasty, the Han empire split into three kingdoms (Wei, Han, Wu) with Wei being the most powerful. Following almost a century of fighting, the three kingdoms were unified under the Jin Dynasty. Unfortunately, this didn't bring peace to the country as power struggles continued. Due to the continuous fighting, China's population was reduced drastically and many tribes from the north attacked, hoping to enlarge their own territory. This was a period of non-stop fighting and conflict, and it wasn't until the Sui Dynasty(581- 618 AD) that the country once again found peace.

Hanfu during this period: In terms of Hanfu, many new styles appeared influenced by a clash of different ethnic groups and cultures. In the Eastern Han/Three Kingdoms period, Hanfu started to evolve from a 1-piece long robe (known as "Shenyi"/深衣) to a 2-piece set with the top and bottom separated (known as "Ruqun"/襦裙). The bottom skirt is pieced together using several long, rectangular pieces, pleated at the top and attached to a waist belt, allowing the bottom to flare out.

This 2-piece Ruqun style reached a peak during the Wei-Jin Northern/Southern dynasties period, and laid the foundation for many Hanfu styles in later dynasties.

*NOTE: Since there are so many different styles during this period, there's a lot of information to dig through. I'm going to do my best to keep the it simple and straightforward, but if I get anything wrong or if there's anything confusion feel free to let me know :D

#hanfu#汉服#china#中国#chinese hanfu#culture#history#fashion#clothing#historical clothing#weijin dynasty#魏晋#南北朝#襦裙#ruqun

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chang'an

Chang'an, located near modern Xian in Shaanxi Province, was the capital of several dynasties of ancient China from the Zhou to the Tang and eventually became one of the world's great metropolises. With regular tree-lined avenues, high walls, pleasure parks, and areas dedicated to specific functions, it provided a model which was copied by other Asian capitals, notably in Japan and Korea.

Early Settlement & Geography

A settlement from Neolithic times, Chang'an was an ideal location for a capital as it was surrounded on all sides by mountains, providing a useful obstacle to invading armies, and was close to the Yellow and Wei Rivers. The advantages of the geographical location are described in the History of the Former Han Dynasty by Pan Ku,

In abundance of flowering plants and fruits

It is the most fertile of the Nine Provinces

In natural barriers for protection and defence

It is the most impregnable refuge in heaven and earth

(in Dawson, 59)

The name Chang'an translates as 'Forever Peace', and although not quite living up to its name, the city did remain important for well over a millennium. Chang'an was an important city in the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) but first became a capital under the Western Zhou (1046-771 BCE). When the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771-256 BCE) arose, the capital moved to Luoyang, Chang'an's great rival city which several times in Chinese history replaced it as capital.

Continue reading...

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomb of An Bei 589 CE. Sogdian tomb.

I couldn't find the translation for the epitaph for this one.

"Differently from the other tombs quoted in this paper, Anbei’s tomb was not excavated by archaeologists, but found and looted by the robbers, therefore the archaeological context of this tomb, even the date of this accidental finding are lost. Until now, all we know is that this tomb robbery happened someday between 2006 and 2007. Several stone figurines, a funerary couch and Anbei’s epitaph stone were found in the tomb. Two stone figurines, parts of the base of the couch and the epitaph are now exhibited in the Tang West Market Museum in Xi’an (Fig.20), four panels belonging to the private owners, including two processing and two banqueting scenes, were published, too (Fig.21).

Although owning the typical Sogdian name An, which means his ancestors migrated into China from Bukhara, his homeland was described in a completely different name, the state of Anjuyeni, which was never recorded by any source before. An’s family moved to China during the Northern Wei dynasty, some of his family members once served in the Bureau of Tributaries. For the court, it’s also an usual way to adopt expatriate immigrants to work in the diplomatic system. Anbei’s father, An Zhishi, served as a middle-rank commanding officer among the honour guards of the court.

As a, likely, third generation immigrant, Anbei’s life depicted in the epitaph was very brief, too. Except for the usual eulogies commonly written in every epitaph, two main parts of his experience were emphasized: his mercantile ability and simple bureaucratic career. The one who wrote the text made a metaphor, assimilating Anbei with two famous ancient Chinese merchants, Baigui and Xiangao during the Eastern Zhou Period (approximately between 8th c. - 3rd c. BC); After that, Anbei’s only short official career as a very lower status clerk of the military headquarters of vassal leader Xuchang was recorded, probably happened in 575 AD when he was 20 years old. Soonafter the Northern Qi was replaced by Northern Zhou dynasty in 577 AD, Anbei returned home in Luoyang, the place where he died and was buried in 589 AD at the age of 34.

The motivation for me to list this robbed tomb here, together with the other tombs which have detailed background obtained through scientific archaeological excavation is, however, mainly not for its elaborate funerary couch, but because of his distinctive identity depicted in the epitaph. Prior to the discovery of Anbei’s tomb, the deceased of all five tombs which constituted the most important foundation of the studies of the foreign immigrants in early medieval China, namely the tombs of Lidan, Kangye, Anjia, Shijun and Yuhong, owned high-ranked official positions such as head of a prefecture or Sabao, which may result in a misconception that only aristocrats of the foreign immigrants could be buried with such elaborate funerary furniture. However, Anbei’s tomb provided an additional possibility about the status of the tomb occupant who used the stone funerary furniture. What is expressly shown in the epitaph, during his 34-year-long life, Anbei was just a very ordinary person, without any notable ancestry from homeland, neither held any high-ranked post, nor received anyone as a posthumous reward.

Except for the basic information above, there is also a remarkable narration during the introduction in the beginning of Anbei’s epitaph, which may reflect the collective mindset among most of the foreign immigrants in China and their efforts in social integration, ‘Although he is a foreigner, after a long life in China, there is no difference between him and the Chinese’.

-Yusheng Li, Study of tombs of Hu people in late 6th century northern China

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

some notes on population and economic decline during the three kingdoms period:

Eastern Han Dynasty population census 156 AD: ~50M people

Western Jin Dynasty population census 280 AD: ~8.2M people

That is an ~83% decline in registered population.

Causes of decline in registered population

1

People dying in famine and war (interrelated causes) during the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period

2

Refugees driven from their lands by war & famine and farmers whose lands were taken from them, through force or debt-traps, by local landlords ( “great families”) overwhelmingly became indentured servants (basically slaves) of local “great families” and weren’t counted as members of the household in the census.

This was a way for “great families” to avoid paying taxes on their employees, since landowners are taxed based on the amount of land they own and the number of people in their “household”, which includes their family members and officially registered employees. When refugees leave their provinces of origin and when peasant farmers sell themselves into indentured servitude, they lose their household registration and cease to be counted as “people”

The only way for these undocumented people to become “registered” again is if the government forces their owners to free them and provide them with land of their own to farm and pay taxes on. As you can imagine, the “great families” were violently resistant to this kind of policy. But from a king’s perspective, registering and assigning land to former indentured servants is an excellent way to increase taxes and soldiers, since it would make a large portion of the population finally “visible” to the tax officials and army recruitment.

Cao Cao tried to implement this kind of reform and achieved limited success because elites across the kingdom refused to cooperate. His son Cao Pi had to scrap this initiative entirely and give the “great families” even more tax breaks because he needed their political support to stabilize the newly formed Wei Dynasty, which in turn made these families more powerful. And when the Sima family usurped the Wei throne, they abolished taxes for much of the “great families”, which helped them achieve political stability for the newly formed Jin Dynasty. But this also sowed the seeds for the eventual economic decline and fracturing of their dynasty as more ordinary people fell into slavery and more economic and political power became concentrated in the hands of local elites.

The Shu-Han kingdom fell into a similar trap as the Wei. Zhuge Liang (at Liu Bei’s request) created a new legal code called called the “Shu Ke” for the Shu-Han kingdom, which is largely based on the Eastern Han dynasty legal code but contained new tax policies that increased taxes on large landowners and reduced the privileges and exemptions that “great families” enjoyed during the Eastern Han. While Zhuge Liang was regent, these new policies were strictly implemented, along with other economic reforms. This allowed the Shu-Han kingdom raise enough money to fund Zhuge Liang’s northern campaigns and also maintain economic growth at the same time.

But after Zhuge Liang’s death, the execution of these economic reforms began to wane. As a result the great families expanded their lands, paid less taxes, more people fell into indentured servitude, and the royal coffers gradually emptied. And Jiang Wei, who was a brilliant military commander but no economist, didn’t understand why the court was increasingly unwilling (and unable) to fund his wars.

The situation was also similar in the Wu Kingdom. When Sun Quan took over the kingdom from his brother, he granted the “great families” of Wu political privileges, more land, and tax breaks to solidify his control as a new and young ruler. In his old age, he realized that these families had way too much power and un-taxable wealth and tried to reduce their influence, but ultimately failed, and the tax burden fell onto ordinary peasant farmers. Farmers who could not pay their taxes were then forced to sell their land and children to those “great families”, who don’t pay taxes on these new “properties”, thus perpetuating the vicious cycle.

To make things worse, to raise money for war, both the Wu and Wei kingdoms simply minted more money (using less silver), which led to skyrocketing inflation. As a result, in some parts of the Wei Kingdom, the monetary system completely collapsed, and people went back to bartering. Say what you will about Liu Shan’s mediocrity, but at least he managed to maintain Zhuge Liang’s monetary policy and the Shu-Han currency remained stable and in circulation both at home and abroad into the final years of the kingdom’s existence.

Oh, and don’t forget climate change: the end of the Eastern Han dynasty saw the beginning of a little ice age, which led to cooling temperatures all across the north, which led to crop failures, famines, and the migration (and invasion) of nomadic peoples from the north

#rot3k#romance of the three kingdoms#three kingdoms#I set out to write a Liu Shan x Zhuge Liang fic#and ended up reading about population census and taxation

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

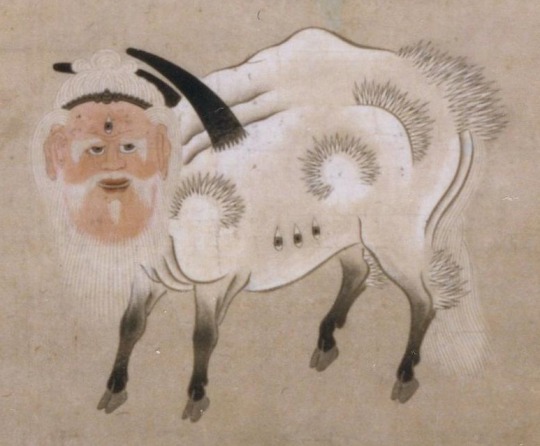

1000 followers special: the history of the hakutaku

I recently hit a major milestone. It would appear that over a thousand people apparently want to see more on their dashboards. To celebrate, I decided to go back to the roots of this blog. While I doubt many of you remember it, some of my first posts were complaints about Touhou fanworks failing to account for the fact that the hakutaku was not a boogeyman, but a good luck charm. In this article, I will explain how come, what exactly the role of an "auspicious beast" entailed, and how different people utilized the story of the hakutaku through history. I will also check how does the Touhou portrayal compare to the historical sources - though that's not the only case of modern reception you will be able to learn about. As usual, more under the cut.

The earliest history of the hakutaku As in the case of many other Japanese mythological beings, the history of the hakutaku actually starts in China. The creature was originally known as baize (白澤); hakutaku is simply the Japanese reading. The name can be literally translated as “white marsh”, but how it initially developed is unknown. Donald Harper argues that baize can effectively be considered a deity. For what it’s worth, there is clear evidence that it could be invoked in theophoric names in the first millennium. The first known case is a certain Zhang Zhongkui (張鍾葵; obviously, his old name is related to the well known figure of the demon queller Zhong Kui) from Northern Wei, who was renamed Zhang Baize (張白澤) by emperor Xianwen. Crown prince Xiao Zhangmao of the Southern Qi was nicknamed Baize, too. Multiple other examples are apparently known, but sadly I was unable to track down any information beyond a confirmation they existed. Generally speaking, the baize played an apotropaic role. Bernard Faure argues that the creature effectively fulfilled many of the roles of the fangxiangshi, a class of ancient exorcists. Pictures of it could be hung in houses to ward off malign spirits and misfortune. Textual sources indicate this custom was widespread among various social strata. Images of the baize could also be embroidered on clothes, banners and other items. An interesting practice tied to this is documented in sources pertaining to the life of empress Wei from the Tang dynasty. Reportedly her younger sister Qiyi (七姨) slept on a pillow with a depiction of the baize to ward off malicious spirits.

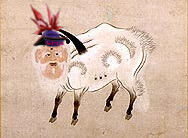

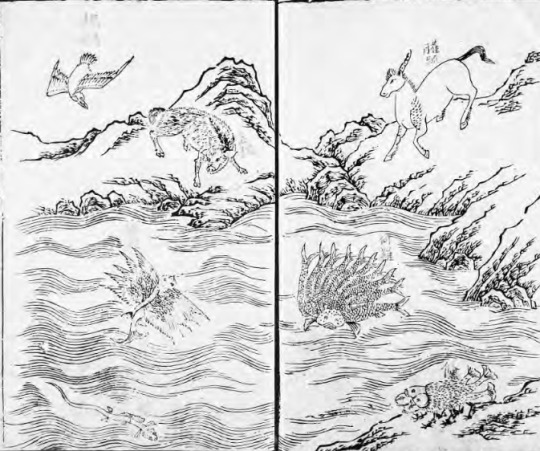

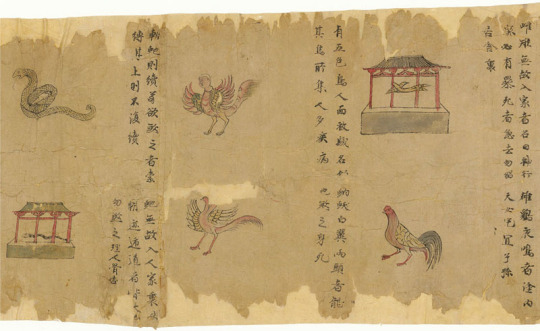

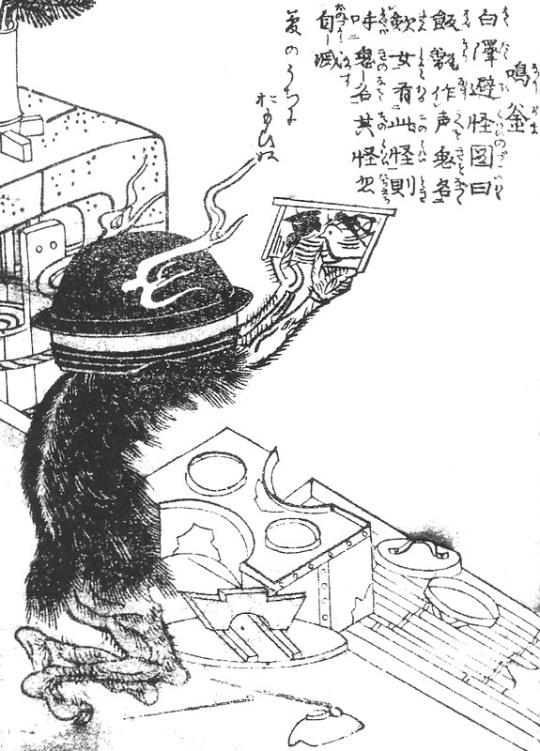

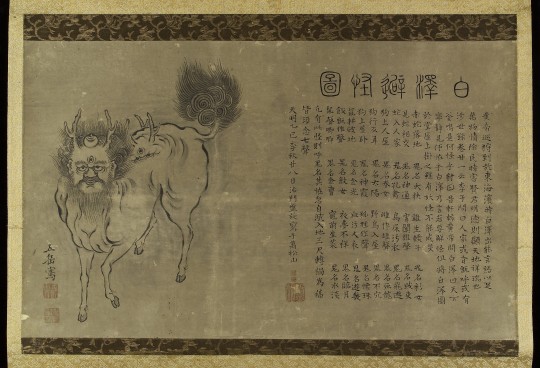

A typical illustration of various creatures from the Shanhaijing (from Richard E. Strassberg's translation; reproduced here for educational purposes only) While the Tang period is when the belief in baize flourished, the creature was actually older. The first references have been dated to the fourth century. Sometimes even in academic publications you can find claims that it is as old as the Shanhaijing, but this is a mistake. It is true that copies of Shanhaijing which mention the baize exist, but they were only produced in the Ming period and the description was likely sourced from a contemporary encyclopedia, Sancai Tuhui. It is not impossible that the baize ultimately did originate before the Six Dynasties period, but this cannot be proven conclusively. From Baopouzi to Dunhuang manuscripts: Baize, the Yellow Emperor and the Baize Tu The first certain attestation of the baize has been identified in Ge Hong’s Baopuzi, which you might remember from my Ten Desires and Zanmu articles. In the section dedicated to the Yellow Emperor, the author states that in addition to his other famous deeds, this legendary ruler recorded the words of the baize. A more detailed account of this event in preserved in a more recent source, the Yunji Qiqian, specifically in the chapter Xuanyuan benji (軒轅本紀; “Basic annals of Xuanyuan”, ie. the Yellow Emperor). It relays how the Yellow Emperor encountered the baize on Mount Huan (桓山) during a hunting expedition to the eastern frontiers of his kingdom, close to the sea. The creature appeared before him to share esoteric knowledge. It relayed that there are eleven thousand five hundred and twenty types of malign beings, the “spectral prodigies” (精怪, jing guai), in the world, and explained how people could protect themselves from each of them. There’s no real theme to the creatures mentioned: they include animal spirits, spirits of places and objects (for example a stove), as well as various beings which can be broadly described as genius loci. The key to overcoming them was to know their true names. This is not a belief unique to the baize tradition. The Yellow Emperor ordered this to be written down so that this knowledge can be preserved and further disseminated. The compilation of baize’s advice came to be known as the Baize Tu (白澤圖), literally “Diagrams of White Marsh”. This tradition must predate Ge Hong, as he mentions the Baize Tu as a work which can be consulted to gain additional insights when it comes to repelling demons. However, he does not connect it with the Yellow Emperor legend directly. Multiple other sources attest that various variants of this treatise actually existed. Song shi (宋史; “History of the Song”), attributes its composition to a certain Li Chunfeng (李淳風; 602–670). Despite apparently relatively wide circulation, every single version of this work is now lost, save for a ninth or tenth century fragment discovered in Dunhuang, the so-called Baize Jingguai Tu (白澤精怪圖), “White Marsh Diagram of Spectral Prodigies”. It was originally identified by Jao Tsung-i in the 1960s, around 60 years after discovery. The surviving sections describe and depict some of the, well, “spectral prodigies”, as promised by the title, as you can see below:

Illustrations sourced from a recent reprint of Jao Tsung-i's article, via Brill; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

Other manuscripts from Dunhuang mention the baize alongside Zhong Kui in the context of new year celebrations. As both of them were believed to keep nefarious forces at bay through different methods, it presumably felt natural to invoke both at once. The Dunhuang texts discussing the baize do not contain any images of the creature. However, the exact same site did provide us with a depiction of it, most likely:

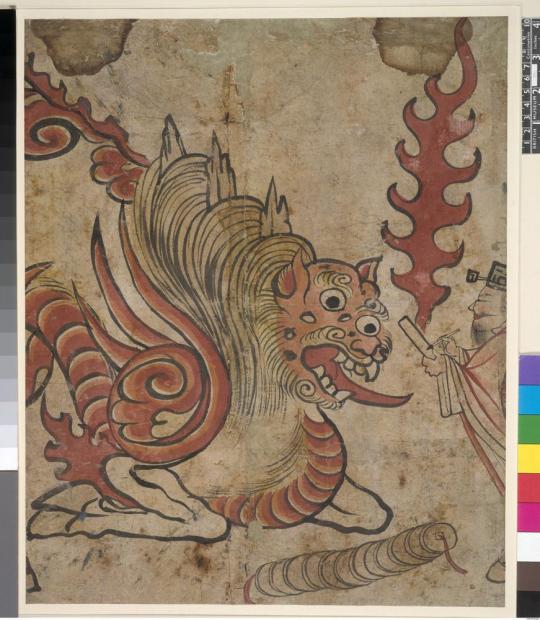

The supposed baize painting from Dunhuang (British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While the enormous creature in painting above was initially interpreted as some sort of longma, according to Donald Harper its distinctly cow-like shape indicates it should be interpreted baize. The human figure is presumably a scribe, which might indicate we’re dealing with a pictorial version of the legend about Yellow Emperor’s encounter with the baize. After all, someone had to be present to write the creature’s advice down, as requested. The string of coins might be there to provide the image with further apotropaic qualities - the use of coins as talismans is a well established part of new year customs dating as far back as the Tang period. That’s actually where the modern custom of giving kids money in red envelopes comes from. While the supposed baize painting is a unique and remarkable work of art from a modern perspective, it was likely not regarded as such when originally made. At some point parts of it have been cut, and a Buddhist woodblock print has been pasted on top of it (obviously they were separated during restoration). Before that it was presumably meant to serve as an ephemeral amulet, discarded after it had served its purpose. This obviously does not diminish its value as a historical source. History is not just just about grand codes of law or royal declarations, as the fact that the study of the culture of some of the oldest states rests largely on the equivalent of receipts and school exercises. I guarantee that in a few hundred years trivial newspaper articles will similarly be the subject of serious inquiries. Buddhist reception of the baize

A Chinese depiction of Manjushri (wikimedia commons) Baize also occurs in Buddhist sources from the Tang period, where the creature is linked to Manjushri. This was rooted in a new development, namely the reinterpretation of this bodhisattva as a figure associated with auspicious signs, rather than his traditional domain, wisdom. Additionally, it was presumably easy to link an at least semi-divine distinctly bovine creature with the custom of referring to certain buddhas and bodhisattvas with the title of “ox king” (牛王). The first source to mention the association between the baize and Manjushri is a text written by the Buddhist monk Kuiji (632-682), a disciple of the famous Xuanzang. He states that a cow giving birth to a baize is one of the signs that the rebirth of Manjushri draws closer, similarly to a feng bird hatching from a chicken egg, a horse giving birth to a qilin, or an elephant with six tusks appearing. As you can see, the baize is in esteemed company here. For instance, the qilin was said to only appear to virtuous rulers, while the six-tusked elephant appears in the traditional account of the historical Buddha’s birth. This tradition is also documented in the Sutra of Manjushri’s Auspicious Signs (文殊吉祥經,Wenshu Jixiang Jing), only known from a small fragment. Here the birth of the baize is actually elevated to the rank of the final omen in the cycle preceding the appearance of the eponymous bodhisattva. The text also alludes to the baize’s apotropaic role as a figure meant to ward off demons. Additionally it states that the creature normally lives in heaven, but can choose to reincarnate on earth, among humans - obviously to foretell the birth of Manjushri. Apparently all of the “auspicious beasts and numinous birds” rejoice when that happens.

The decline of baize in China It seems that after the Tang period, the popularity of the baize declined in China, mostly at the expense of Zhong Kui. It was not a complete disappearance, but while the early baize largely belonged in the domain of popular belief, later on most attestations reflect courtly and scholarly interests only. For unknown reasons at some point baize’s iconography was reinvented, with the ox-like form replaced by one with leonine features. The Southern Song encyclopedia Gujin Hebi Shilei Beiyao outright suggests baize is simply a term referring to lions. In a source from the Yuan period, a banner depicting the baize as a creature with “tiger head, red hair with horns, dragon body” is mentioned, though, so evidently not everyone accepted this rationalization. Some references to the baize can still be found in texts from the Qing period. One example is a poem by a Tiantai Buddhist monk, Zhang Hengwu (張亨梧; 1633–1708), based on the well established Yellow Emperor narrative. In his version, the legendary ruler specifically seeks the baize while traveling to the east. Japanese reception of the baize

The baize/hakutaku, as depicted by Gusukuma Seihō (wikimedia commons)

Baize’s illustrious career was not limited to one country. At some point, the creature was also introduced to Japan. Most likely it reached the archipelago either through Buddhist sources or Sa Shouzhen’s (薩守真) treatise Tiandi Ruixiang Zhi (天地瑞祥志; “Treatise on auspicious signs in heaven and earth”). The latter was transmitted to Japan as early as in the ninth century, and it is possible the baize - or rather the hakutaku, following the Japanese reading of the name - was already recognized as an apotropaic creature in Japan at this time. By the 1200s, the belief in its auspicious power was well established. Tachibana no Narisue states in Kokon Chomonjū (1254) that in the private chambers of the emperor (Seiryōden) there was an “oni room” (鬼の間, oni no ma) in which a painting of hakutaku repelling demons was displayed. Japanese art did not adopt the younger Chinese convention of portraying the creature as leonine. It was not entirely unknown, with the best known example being an illustration from the Edo period encyclopedia Wakan Sansai Zue, but it never became popular. The ox-like shape remained the norm. The iconography of the hakutaku is thus pretty consistent: the body of a white ox, the head of an old man with a vertical third eye and sometimes a pair of horns, plus additional eyes and horns on the flanks. The human head might be a Japanese innovation, reflecting the ability of human speech ascribed to the creature. Probably the single best known Japanese depiction of the hakutaku is that painted by Gusukuma Seihō (1614-1644). He was the official painter of the royal court of Ryukyu and somewhat of an international celebrity in his times, considering his work was renowned not just in his homeland, but also among Chinese envoys to Ryukyu and by the Tokugawa court. Sadly, this is his only surviving painting, unless there are more in private collections inaccessible to historians (this is not impossible, and reportedly a second hakutaku painting attributed to him belonged to a private Okinawan collector in the 1920s at the very least). As noted by Bernard Faure, hakutaku was effectively a visual reversal of Gozu Tenno, who could be portrayed as a man with a bull’s head, and often played a similar apotropaic role. Additionally, through the title of “ox king”, which recurs in Japanese sources, hakutaku can be indirectly linked to many other major figures of esoteric Buddhism, including Daiitoku Myōō, Ishana and Yama. If you really want to stretch it you can even make a case for parallels with Matarajin, considering both his demon-repelling properties and his association with oxen.

Hakutaku and baku

The baku, as depicted by Hokusai (wikimedia commons)

As mentioned by the sixteenth century author Naotomo Isshiki (一色直朝), in addition to warding off demons hakutaku was also believed to eat bad dreams. This indicates confusion or conflation with the baku. The two are also treated as synonymous in Gen’i Nagoya’s (名古屋玄医; 1628-1696) Minkan Saijiki (民間歲時記 ; “Everyman’s record of the year and seasons”), which is about a century younger. He pretty clearly describes the hakutaku rather than the baku, since the “diagrams” known from Chinese sources and the Yellow Emperor legend are both mentioned. The original tradition must have been well known at least among

“King baku” (Gohyaku Rakanji website; reproduced here for educational purposes only) By far the best example of this phenomenon of conflationg baku and hakutaku a statue from Gohyaku Rakanji (“Temple of the Five Hundred Arhats”) which depicts a hakutaku, but is referred to as “king baku” (獏王) today. It was originally sculpted by the monk Shōun (松雲; 1648 - 1710) in the late seventeenth century, much like the rest of the still displayed statuary. I actually first learned about the hakutaku in 2012 or so from the baku article on Zack Davidsson’s blog Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, which mentions the Gohyaku Rakanji statue and the conflation between the two creatures. Lafcadio Hearn also asserted hakutaku is simply another name for baku.

Hakutaku in the Edo period For unknown reasons the popularity of hakutaku increased in the Edo period, especially over the course of the eighteenth century. Sekien Toriyama included it in one of his compilations of yokai illustrations. He also refers to the hakutaku (or rather to baize, as the note is in Chinese) in his description of the narigama (a type of tsukomogami), stating that the way to get rid of this creature’s forerunner renjo was shared with humans by the auspicious beast.

The norigama illustration in mention (wikimedia commons)

Most importantly, amulets depicting hakutaku were used for protection while traveling and to ward off illness and misfortune. This custom relied on a Chinese source, the twelfth century treatise Sheshi lu (涉世錄), literally “Record of Experiencing the World” which prescribed hanging an image of the baize at home to prevent misfortune. This work is now lost and the relevant passage, known from quotations in Japanese sources, is its longest surviving section. The increase in apotropaic usage of hakutaku images lead to the creation of the so-called White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies (白澤避怪圖, Hakutaku Hikai Zu). This term refers to talismans consisting of a painting of the creature and a short version of the already discussed Yellow Emperor legend. It culminates in a scene with no Chinese forerunner, in which the hakutaku announces to the emperor that hanging an image representing it in a house protects from, well, “ominous prodigies”. A list of some of them was also provided. The Zen monk Hakuin (白隱; 1686–1768) already describes the hakutaku talismans as popular, though he stresses neither he nor the people using them were aware of their origin. The precise history of their development remains unknown to researchers too. Seemingly they couldn’t be older than the seventeenth century at the earliest. Why did apotropaic images of hakutaku aimed at general population resurface in Japan centuries after their use ceased in China is unknown. Their spread might have been tied with the practices of the shugenja, as many of them were distributed among pilgrims visiting Mt. Togakushi, a well known center of the Shugendo tradition.

The most famous apotropaic depiction of hakutaku (wikimedia commons)

A well known example of the White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies, presently in the collection of the British Museum, was painted by Gogaku Fukuhara, with the text provided by the Buddhist monk Bansen (盤旋). Based on the colophon of their work, it was completed on October 30, 1785. It’s worth highlighting that it situates the creature in Buddhist context (if that was not clear enough from the involvement of a monk), as the structure on its head is pretty clearly a wish-fulfilling jewel. To my best knowledge, this has no forerunners among Chinese depictions. This specific work of art has been characterized as a “deluxe” example of a talisman, painted and calligraphed by hand, presumably made with a connoisseur in mind. Most people relied on cheap woodblock prints instead for their hakutaku needs. These were obviously perishable, so few of them survive, though two of the woodblocks used to make them, both from Togakushi, have been preserved. Notably, hakutaku talismans were employed during the cholera epidemic of 1858. Reportedly in Tokyo people placed them on their headrests before going to sleep. I sadly did not find any source explaining whether this was a conscious revival of the Tang custom discussed earlier, or if the similarity is entirely accidental. Hakutaku talismans were also utilized by travelers. this custom is documented in an Edo period book which can be considered an early example of a travel guide, Ryokō yōjinshū (旅行用心集; “Precautions for travelers”) by Yasumi Roan (八隅蘆菴). It was published in 1810 as part of what can be described as an early case of a domestic tourism boom resulting in the flourishing of travel literature. Much of the advice is surprisingly timeless, for example to abstain from leaving graffiti and stickers at landmarks such as temples and shrines, but also trees and sufficiently big rocks. I have to say the suggestion that a halberd is too heavy to carry around while on a trip is pretty solid too. Roan has many other great suggestions, but ultimately this is not an article about him, so they have to wait for another time. When it comes to the hakutaku, he states that travelers should equip themselves with images of this creature and the five great mountains of China (gogaku) to ward off spirits, but also wild animals and mundane accidents. Last thing which needs to be discussed here is that in addition to the apotropaic paintings, hakutaku was also sometimes portrayed in the form of a netsuke. However, such depictions are apparently not common.

A hakutaku netsuke from the British Museum (photo proided by my friend Li)

The modern reception of the hakutaku It remains unclear when apotropaic depictions of the hakutaku ceased to be made. It seems to me that it can be plausibly assumed it occurred in the Meiji period, but I have no solid evidence. However, the hakutaku was not entirely forgotten.

To my best knowledge, the single highest profile portrayal of a hakutaku in modern fiction is still Keine from Imperishable Night. What little spotlight she received paints an image remarkably close to the genuine accounts: as we learn from her bio, “she loves humans and always tries to help them” and she is pretty consistently portrayed as a staunch protector of the villagers and Mokou. The fact she’s not fully human doesn’t seem to be a mystery in-universe, and she is evidently accepted nonetheless. This doesn’t seem to be universally acknowledged in fanworks which is puzzling to me. There are dozens of yokai which are little more than boogeymen, but there are very few distinctly auspicious ones, and I prefer the canon approach of emphasizing that Keine and the village community mutually like each other. Keine’s role as a teacher presumably is meant to be a nod to the lecture about malign spirits the baize delivered to the Yellow Emperor. I am a huge fan of specifying the school she teaches at is a terakoya; whether ZUN was aware of it or not, hakutaku talismans and temple schools are both expressions of Edo popular culture, so the theme does more or less fit together. What little we learn about hakutaku in Touhou in general from Perfect Memento in Strict Sense also draws from historical sources. I will however note that as far as I can tell that revealing that a new ruler is going to be virtuous is a role assigned of various “auspicious beasts” like qilin, longma and so on in general rather than exclusively to the baize/hakutaku. There are also no legends about a hakutaku meeting with any Japanese rulers, even though most of Keine’s spellcards reference the imperial family (or attempts at overthrowing it; is she an anti-monarchist?). The rest of Keine's character seems to be ZUN’s invention. The only account of the hakutaku (well, baize’s) origin makes it clear the creature is a type of supernatural cattle, not a human, and there is obviously no such a thing as a “were-hakutaku”. I presume this was meant to highlight her human side and tie her more closely to the moon theme of Imperishable Night, though I think her character would still work perfectly fine without that. At the same time, I won’t deny I wouldn’t mind getting some more insights into Keine’s backstory in the future. Nothing major, just something similar to the Ran hints we just got in Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost. There is also no strong connection between the hakutaku and recording history, though you can probably make a case that as a mainstay of chronicles and encyclopedias it does have a distinctly historical theme. I personally like this innovation, and especially how it is described in PMiSS.Touhou aside, it’s worth mentioning that a resurgence in the interest in hakutaku occurred in the early months of the covid pandemic. This is an example of a broader surge in interest in various apotropaic disease-repelling mythical and folkloric figures in response to the rise of the novel coronavirus (as you might remember, the amabie fad in particular even managed to cross language barriers). It probably helped that a statue representing the hakutaku was rediscovered in the Tennō-ji in Osaka recently.

The Tennō-ji hakutaku (Asahi Shimbun; source contains more photos and a video. Reproduced here for educational purposes only) Some of the articles covering the brief hakutaku resurgence seemingly confuse it with the kutabe (kudan), but these are actually two separate creatures. The source of confusion is probably Shigeru Mizuki, who did depict kutabe as notably hakutaku-like, since he believed the it was a local adaptation of the standard hakutaku narrative.

Shigeru Mizuki’s kutabe (reproduced here for educational purposes only) Mizuki’s portrayal in turn influenced figures of kutabe made by local craftsmen from Takaoka in 2020. The English edition of Asahi Shimbun covered this in some more detail here, though ultimately it is beyond the scope of this article. As far as I know the connection, while plausible, does not permit full conflation, and in particular kutabe never attained the sort of religious significance hakutaku once had. Bibliography

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Donald Harper, 'Hakutaku hi kai zu' 白澤避怪図 (White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies)

Donald Harper, Pictures of Baize / Hakutaku 白澤 (White Marsh): Ephemera and Popular Culture in Tang China and Edo Japan (not accessible online but there is a digital lecture version on youtube)

Jao Tsung-i, Postface to the Two Dunhuang Manuscript Fragments of the Baize jingguai tu 白澤精怪圖 (White Marsh’s Diagrams of Spectral Prodigies; P.2682, S.6261)

Richard E. Strassberg, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas

Kathryn Tanaka, Amabie as a Play in Kansai

Constantine N. Vaporis, Caveat Viator. Advice to Travelers in the Edo Period

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

When does Dungeon Meshi take place?

This is an excerpt from Chapter 2 of my paper, "Real World Cultural and Linguistic Influences in Delicious in Dungeon." Dungeon Meshi takes place in the year 514, however we don’t know how that number relates to anything else in the Dungeon Meshi world, so it isn’t really useful for identifying what era Kui is trying to depict.

It can’t be that the Ancient Cataclysm happened 514 years ago (it was still referred to as ancient history by Thistle and Delgal a thousand years ago), and it can’t be when the current elf queen’s reign began (she’s only 372), so it’s either marking some other major event, like the beginning of the reign of a royal family or the end of a war, or they reset their calendar at regular intervals, such as every two-thousand years for record-keeping purposes.

In the real world, 514 CE would have been the early Medieval era, just after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, which left Europe fractured into many small Germanic kingdoms competing with each other. It was also the beginning of the Asuka period in Japan, and the end of the Northern Wei Dynasty in China.

This has some similarities to the world we’re shown in Dungeon Meshi: the Western elves have abandoned most of their land in the Eastern hemisphere, leaving the local dwarven, gnomish and tall-man people (whose cultures are primarily Germanic) to fight amongst themselves for the land. A massive upheaval caused by a major imperial power collapsing.

However, based on character behavior, culture, clothing and technology, Dungeon Meshi appears to be set in a vaguely Renaissance (1450 CE-1650 CE) time period, with some elements from classical antiquity (800 BCE-500 CE), the Medieval era (476 CE-1300 CE), as well as some hyper-advanced steampunk/magic technology and modern day anachronisms. (Potential spoilers beyond the cut.)

The technological and artistic development of the different cultures is very different, with the long-lived races appearing to live a more modern lifestyle than the short-lived races. In the extra materials, Toshiro implies that Falin might find the Island of Wa “primitive” because they lack the social and technological advancements that come from contact with the long-lived races, and the Western elf Fleki calls the Eastern Continent a “primitive land” while complaining about the quality of life.

Based on this and additional evidence, we can reasonably conclude that the elven lands in the West are probably the most “modern”, followed by the lands in the Eastern hemisphere, with the Eastern Archipelago lagging the furthest behind.

Because of this difference between the races, it makes sense that we see a mix of different eras and styles of technology and clothing. For example, we see characters wearing Neolithic fur garments, Greco-Roman tunics, and Medieval garments as everyday clothes at the same time that other characters wear Renaissance and even 19th century-influenced garments.

Meanwhile, many things in the Dungeon Meshi world have also remained unusually stagnant for far longer than they did in the real world. Realistic oil painting seems to have remained unchanged for more than a thousand years, and Medieval-looking clothing that was worn a thousand years ago is still being worn in the “present” day, virtually unchanged.

There are also some things that are much more advanced than the Renaissance period, like steampunk elevators, and magical communication that works through birds/fairies/crystal balls/telephones and allows for instant contact across the globe… A huge advancement that should impact every element of life and society, thanks to the ability to easily exchange information.

In the real world, instant communication is the foundational element that makes things like precise time-keeping, time-zones, advanced banking, stock markets and news reporting possible… So one can assume that some of these things might possibly exist in some form in the Dungeon Meshi setting.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

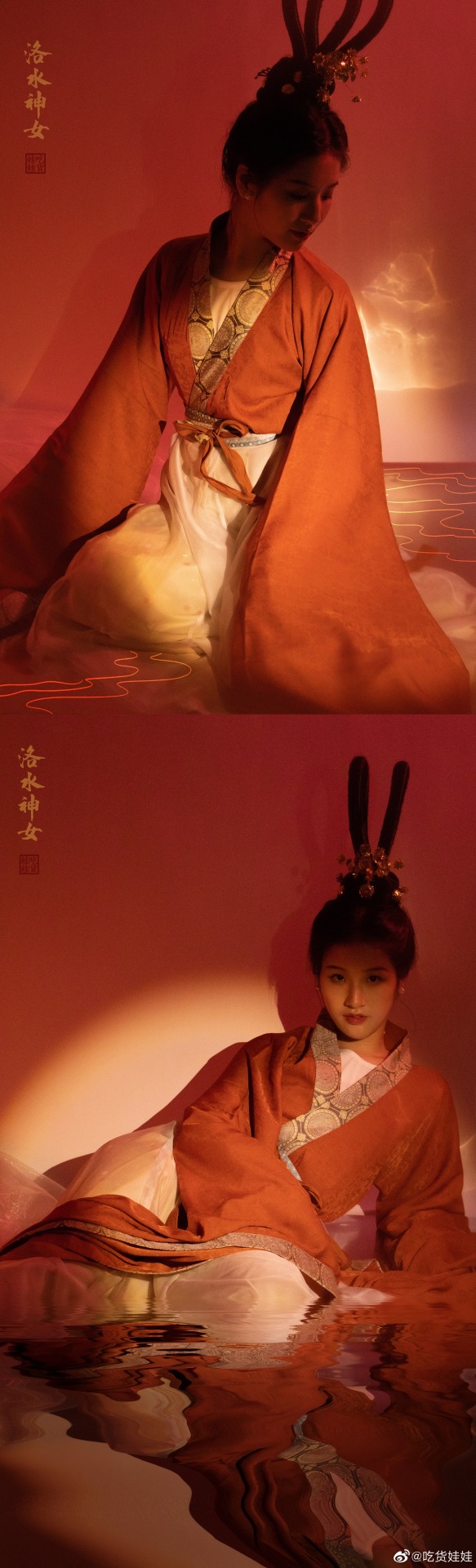

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

China Eastern Jin Dynasty Silk Painting:《The Goddess of the River Luo /洛神赋图》BY 顾恺之(Song Dynasty copy ver.)

China Western Wei & Northern Wei Dunhuang Murals and Lacquer Paintings

China Southern Dynasties Portrait Bricks

[Hanfu・漢服]Chinese Jin Dynasty-Northern and Southern Dynasties Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Hairstyle

--------------

Gu Kaizhi(顾恺之)'s work "The Goddess of the River Luo / Luoshen Fu Tu" in the Eastern Jin Dynasty had a profound influence on people's impression of gods in all subsequent Chinese dynasties.Although the original painting has been lost, there are many copied ver in various dynasties China.

Wu Daozi, who is known as the "painting fairy",his works about godness can also be seen to be deeply influenced by the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties.

Eighty seven celestial people, Wu Daozi,Tang Dynasty

Therefore, we can often see Chinese gods (except Buddhist Bodhisattvas) wearing attire in the style of the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties.

————————

📸Recreation Work: @吃货娃娃

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1868003212/M36MNh5wL

————————

#chinese hanfu#Jin Dynasty-Northern and Southern Dynasties#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#chinese traditional clothing#china#chinese#chinese art history#historical fashion#historical costuming#吃货娃娃#漢服#汉服#中華風#chinese style

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

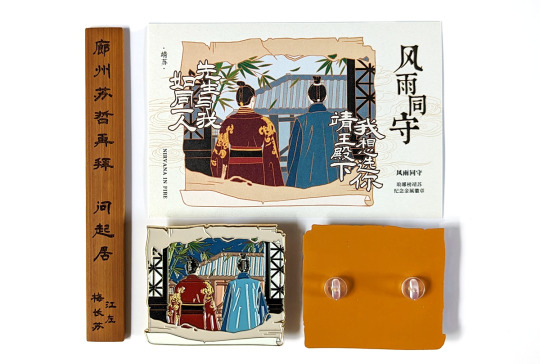

The trouble with collecting merch is it’s difficult to stop once you start. This Jingsu enamel pin is by the prolific 长风万里, who is responsible for some of the most iconic NiF pins (check out the weidian store for a partial selection). Like many fan-made pins, it’s a re-rendering of a scene from canon, in this case episode 52 [x], where Jingsu look on as thunder and wind portend the storm brewing on the horizon after Princess Liyang has agreed to present Xie Yu’s confessed crimes at the Emperor’s banquet.

The pin emphasizes the storm in both design (bamboo leaves scattering in the wind) and name: 风雨同守, loosely enduring the tempest together. As for why the image has been transposed onto a tattered scroll, the pin maker said the inspiration came from rubbings/拓印 and elaborated some more:

Personally, I think of this as an excavated artwork (with the surface damaged in its old age) that was created out of Jingyan’s longing. As if Jingsu actually existed in history and will live on for a long, long time. 我自己把这个当做是一件出土的画作(年岁久远画面有所破损),是景琰怀念所做。���好像历史上真有他们的存在,靖苏真的来日方长。

Historically, rubbings not only create an impression of existing artwork but are themselves artworks that take skill and patience. The typical process starts with adhering paper to a stone carving, then ink is dabbed to the paper such that the flat surface takes on the color of the ink while carved areas remain white (here’s a process video). Collecting rubbings was a popular pastime of the literati, and rubbings of good calligraphy were especially in demand for study and appreciation, serving a similar purpose to block printing in allowing many people to see replicas of an original. The originals may have also come from a non-stone medium: some artworks originally on paper or fabric were replicated onto stone so that rubbings could be made and collected [x]. Nowadays, ancient rubbings are valuable artifacts, especially in cases where the carving has been lost.

The rubbing influence is very clear in the second version of the pin, here juxtaposed against one of its inspirations:

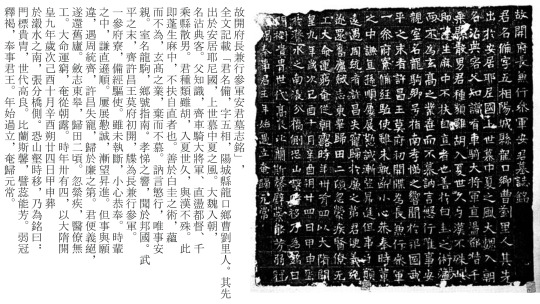

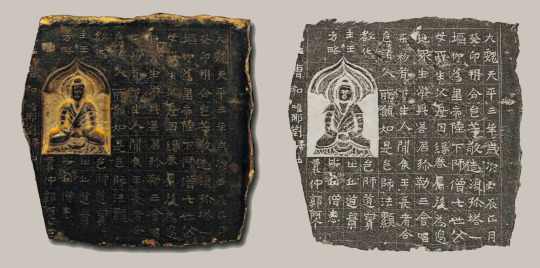

Though the text on the right rubbing says it’s from the Tianping Era of Eastern Wei, Year 2/魏天平二年 (535 CE), which is contemporaneous with the Liang dynasty that loosely inspired the fictional NiF Liang, I couldn’t find an actual historical artwork corresponding to this rubbing, and the mass antique market is flooded with fabrications (it’s also thoroughly possible I simply failed to find the original). But here’s a real fragment of a stone Buddhist votive tablet and its rubbing that’s now at the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong [x]:

The text says that this was made in Tianping Era, Year 3, one year after the one above, and describes the building of a Buddhist pagoda in offering, which was a common practice at the time. This monochromatic rubbing style was also quite typical; though both black ink and red ink (cinnabar-based) rubbings existed separately, they were not really seen in combination in a single rubbing until much later. What is believed to be the only surviving book of bicolor rubbings before the modern era was made in the Qing dynasty around the 1800s and was itself a copy of a lost multicolor work from the same dynasty [x].

In this context of transference of art and meaning between mediums, it’s all too easy to imagine a backstory for this Jingsu scroll: first there was a stone carving, close enough to the actual scene that the artist must have worked from Jingyan’s memory of that day. Instead of the more common approach of carving the outline or the background, the artist decided to carve the foreground so the figures were sunken into the stone. And later, a rubbing was made and mounted onto a scroll, buried and excavated, then finally rendered from fiction to reality in the form of an enamel pin. Each creation is an act of remembering and reinventing, of placing yourself in the observer’s shoes, of stoking the flames of the original story—the fire burns on through metaphorical wood replaced over the centuries, its appearance ever-changing, its core not forgotten.

That’s enough of reading too much into things—I also like the pin on its own. One thing that 长风万里 does well is not just sell pins but also communicate the entire behind-the-scenes process with the QQ group, which is several months’ worth of iterations that I find at least as interesting as the final product. For this pin, you can trace through chat logs how the pin evolved all the way from the original concept sketch to the pieces of metal that fit in your hand (thanks to 长风万里 for letting me share the draft versions here):

Once the pin maker comes up with an idea and decides to go for it, the initial sketch is given to the commissioned artist (this pin was drawn by Forwrite, on weibo and lofter) along with reference images. The artist turns these into a line drawing following the design rules of enamel pins (each block of solid color should be fully enclosed by lines, for example). Some artists will color in the line art while other pin creators commission only the line art and fill in the colors themselves. The final colors are limited to the available palette at the factory chosen to make the pins, and once the color vector art is handed to the pin factory along with instructions on detailing and finishes, the physical manufacturing process begins in earnest (this could be the subject of its own long post).

You may have noticed that there are some color changes from the vector design to the physical pins, most notably the sky in the top pin. This came about as a serendipitous accident where the factory colored the sky of the sample pin dark blue instead of the requested sunset yellow, but the pin buyers active in the group chat liked the dark blue enough that it was kept as the final color. The light grayish blue variant ended up being chosen for the backing card/背卡 instead:

Though backing cards are nominally named for their purpose in supporting the pin, practically no one sticks their pins through these cards in Chinese fandom; instead, collectors generally buy cases and books to keep each piece in pristine condition. And so unlike utilitarian cards that are meant to serve as a background to the pin, fully designed backing cards that stand on their own are very much a thing. The card also adds back in the iconic Jingsu lines that were in the original concept sketch, I want to choose you, Your Highness Prince Jing/我想选你靖王殿下 from Mei Changsu and Sir and I are as one person/先生与我如同一人 from Jingyan.

And now for the last part of the merch package that comes with the pin: the wooden piece on the left is an inscribed bamboo name slip/名刺 meant to resemble what MCS might have presented Jingyan when he visited his manor in episode 9 [x]. This was a preorder bonus to encourage buyers to get on board early, since the upfront costs to commission the artist and get a sample made at the factory are a significant portion of the overall costs (if not enough people preorder, the pin is canceled and the payment refunded, and the pin maker has to take the loss of at least the artist’s fees).

Name slips were the ancient analogs to modern business cards and an important tool of connection building in the ancient bureaucracy. The tradition of presenting a slip before you visit someone’s residence, especially if you’re lower in status than the person you’re visiting, persisted for many dynasties while the form of the slip evolved over time. Even though the visitation slip in canon appeared to be a bound paper booklet, folded books wouldn’t appear until the Tang dynasty—though paper was invented in the Han dynasty, it took time for the manufacturing process to improve sufficiently for a fundamental shift in writing mediums. Bamboo slips were what they would have used in the real Liang dynasty (plus, the modern-day replica is objectively great merch that can be used as a bookmark/fidget stick/cosplay prop/whatever else you can think of).

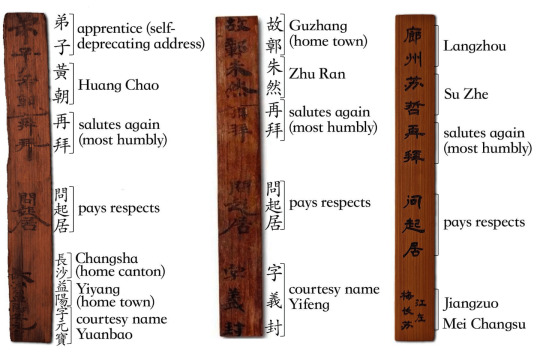

Slips from around the NiF time period generally stated some combination of your given name/名, your courtesy name/字, the region you’re from, and some boilerplate deferential language. Here are two real ones from Huang Chao/黄朝 and Zhu Ran/朱然 of the Three Kingdoms period next to MCS’s, with the meaning of some phrases listed in parentheses after the literal translation (using two of MCS’s names is a good solution for the lack of courtesy names in canon):

To balance out all the white background product photography, I’ll close with some texture shots:

#cost for everything was ¥90 or about $13#overseas shipping not included#先生与我,如同一人#chinese fandom#nirvana in fire#琅琊榜#merch review#long post

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

Gunpowder was invented in China sometime during the first millennium AD. The earliest possible reference to gunpowder appeared in 142 AD during the Eastern Han dynasty when the alchemistWei Boyang, also known as the "father of alchemy", wrote about a substance with gunpowder-like properties. He described a mixture of three powders that would "fly and dance" violently in his Cantong qi, otherwise known as the Book of the Kinship of Three, a Taoist text on the subject of alchemy. At this time, saltpeter was produced in Hanzhong, but would shift to Gansu and Sichuan later on. Wei Boyang is considered to be a semi-legendary figure meant to represent a "collective unity", and the Cantong qi was probably written in stages from the Han dynasty to 450 AD.

While it was almost certainly not their intention to create a weapon of war, Taoist alchemists continued to play a major role in gunpowder development due to their experiments with sulfur and saltpeter involved in searching for eternal life and ways to transmute one material into another. Historian Peter Lorge notes that despite the early association of gunpowder with Taoism, this may be a quirk of historiography and a result of the better preservation of texts associated with Taoism, rather than being a subject limited to only Taoists. The Taoist quest for the elixir of life attracted many powerful patrons, one of whom was Emperor Wu of Han. One of the resulting alchemical experiments involved heating 10% sulfur and 75% saltpeter to transform them.

That's it, im grabbing gunpowder to eat. I'm basically craving it at this point.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

I thank you for answering my previous question! (I'm so glad there are people on social media who work together to share knowledge like this!)

One of things I guess I did get confused with in my research is Nezha's origin story. It does help that you clarified about the many versions being different but they all are a part of telling the story. I overheard a rumor that there was an official book that told the "original" version of his story, but that is what my research is mainly trying to solve. I see a few titles saying they talk about Nezha's backstory, but none that claimed to be original. So I suppose I could be wrong in what I heard. Again, I thank you fir answering my questions! It's been fun learning new things about these topics!

Hello Hello!

I see, I understand what you’re trying to get here. To the best of my knowledge the earliest version of Nezha’s origin myth comes from The Grand Compendium of the Three Religion’s Deities. There is an edition from the Ming Dynasty (1368AD-1644AD) and an edition from the Qing Dynasty (1636AD–1911AD), but both editions cover roughly the same information and the distinction isn’t necessary here.

When he was five days old, Nezha went bathing in the Eastern Ocean. He trampled over the [dragon king's] Crystal Palace. He somersaulted straight to the top of the Precious Pagoda. Because he had trampled over his palace, the infuriated dragon king challenged him to fight. By then, Nezha was already seven days old, and he could overcome the nine dragons. The old dragon had no choice, except complaining to the [Jade] Emperor. The General [Nezha] knew of his intention. Intercepting him by Heaven's Gate, he killed the dragon. Mounting the Jade Emperor's altar, Nezha took the Buddha's bow and arrows. He shot an arrow, unintentionally killing Lady Rock's son. Lady Rock raised an army to fight him. The General [Nezha] took the Demon-Felling Club from his father's altar and, fighting his way Westwards, slew her. Considering that Lady Rock had been the demons' chief, Nezha's father was infuriated. He worried lest his son's killing her would provoke the demon hordes to war. Therefore, the General [Nezha] sliced off his flesh and bones, returning them to his father. Holding fast to his inner soul (zhen ling), he hastened to the Buddha's side, pleading that the World-Honored One make him complete once more. Considering that Nezha could subdue demons, the Buddha snapped a lotus flower. He fashioned it's stem into bones, it's roots into flesh, it's fiber into tendons, and it's leaves into clothes, giving life to Nezha once more.

I do hope this was helpful in your search. It’s entirely possible this story was imported from India during the Tang Dynasty (618AD-907AD) or Song Dynasty (960AD-1279AD) or even as early as the Wei Dynasty (386AD-535AD)

A majority of literature about Nezha was written during the Tang Dynasty (618AD-907AD) which was followed by one (of many) instances where China was no longer unified in a warring states period. It would be (705AD-960AD) where China was not unified and no further literature about Nezha was either written or survived.

Nezha had of course existed before the 7th century, but in terms of a timeframe Nezha and any written record of him was brought to China some centuries before Tang Sanzang went to India. Figure he formally entered China around 266AD-420AD while Sanzang left for India around 629AD.

It is wholly possible a story like this existed while Nezha was still Nalakubara, third son of the Heavenly King Vaisravana. I’ve yet to locate anything like that yet but this post will be amended to reflect if new information has been found.

#li nezha#nezha#lmk nezha#monkie kid nezha#nezha 2019#nezha reborn#the legend of nezha#dislyte nezha#nezha lego monkie kid#third lotus prince

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 11: Taizong's trip to the Underworld

-Fun fact: "Taizong's trip to the Underworld" is actually a tale that predated JTTW, and its earliest surviving form could be dated to a book called 朝野佥载.

-Another late Tang version could be found in the Dunhuang collections, in which Taizong's bargain with Cui Jue was a lot more complicated. In JTTW novel proper, Cui Jue/Ziyu was just another high-level official who took his work into the afterlife, but in the Dunhuang version, much like Wei Zheng, he was a living person working part-time for the Underworld.

-However, his position in court was nowhere as high as Wei Zheng's, so he took the chance to blackmail Taizong into giving him a promotion, and the whole exchange was full of subtle psychological warfare——Judge Cui offhandedly mentioning "Hey, you heard the ghosts crying next door? That's your dead brothers (whom you totally didn't murder in a coup)", Taizong being scared out of his mind but also trying to keep up appearances while figuring out the appropriate bribe for this guy…

-Fun Fact #2: Dead People Lawsuits were a common trope in Tang legends and folklore, where people explained sudden deaths as the dead getting a summon to the Underworld courts, or, in slightly more fortuious cases, appointed as ghostly officials.

-The novel sadly skips the courtroom scene and handwaves it with a "Yeah, the prosecutor had already been sent to reincarnation", which kinda defeats the whole purpose of summoning Taizong here, but whatever.

-On the plus(?) side, he got a free tour of the afterlife!

-I'm a big fan of Underworld tales in Chinese mythos, because, aside from all the brutal tortures and horrors, it can also be pretty damn funny.

-Like the Ten Kings asking Taizong for some pumpkins ("southern melons") just to complete their Directional Melons Set.

"Wait, pumpkins? Isn't that from the Americas? And aren't they still missing the 'northern melons'?"

-Precisely! This could actually give us some clue about when the book was compiled: pumpkins were most likely brought to Ming China in the 1520s by Portuguese ambassadors visiting Nanjing and Beijing, and the earliest JTTW novel was printed in 1592.

-So, when this segment was added, pumpkins were still considered a rare, exotic vegetable. Further research also suggests that, throughout the Ming and Qing dynasty, "northern melons" was just another name for pumpkins of lesser quality.

-How Taizong managed to find a pumpkin in 639 C.E. to give to our conveniently suicidal delivery guy is beyond anyone's guess. Hey, maybe the immortals of the eastern seas ran a cross-Pacific mailing service with their cranes or something.

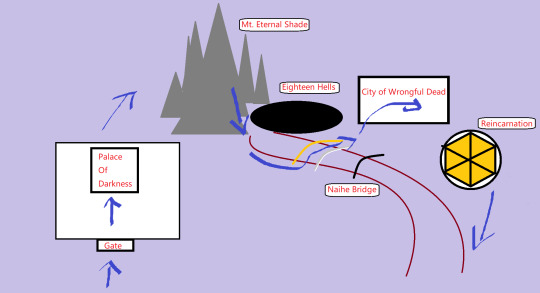

-This is clearer in the Chinese version, but the law of Underworld's reality literally dictates that you cannot walk back from the way you come. So…does the road disappear behind you as you go? Are buildings in the City of the Dead constantly shifting and rearranging themselves like an Escher painting in Lego form? Or do you just have to go round in circles, a lot?

[A very rough map of Taizong's route through the Underworld, as I visualize it]

-In Buddhist canon, the Wheel of Reincarnation isn't like, a literal magical wheel. However, in JTTW novel and illustrations, this is very much the case, and might be a result of people mixing IRL scripture wheels (轮藏) with reincarnation (轮回).

-Personally, I'd like to see more creative reimagining of the thing; for example, a giant waterwheel on the Nai River that sifts through souls like droplets.

@journeythroughjourneytothewest

31 notes

·

View notes