#eastern jin dynasty

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

fragment of a wool rug or garment, patterned in stripes and wang 王 (king) characters crossed by contrasting colors. taken from the ruins of niya 尼雅 (recorded in han records as jingjue 精絕), a former oasis state near khotan in modern xinjiang. excavated in 1900 or 1901 by british archeologist aurel stein. three kingdoms era or western/eastern jin dynasty, 3rd century-4th century.

white s-plied two-ply warp, single-ply z-twist weft in yellow, blue, green, red, and rose. the green and red stripes are done in plain weave with single weft; the 王 crosses and the staggered boxes (lower left photo) are done in double weft. the crosses use discontinuous tapestry weave. the british museum notes that this textile may have been produced in india.

#china#three kingdoms era#western jin dynasty#eastern jin dynasty#textile history#museum trawling#image source: british museum#aurel stein#i see what they're getting at - the stripes are not very jin dynasty - but the crossed 王 characters do not necessarily say 'india' to me

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Eastern and Western cores had each split in two. In China, the Eastern Jin dynasty ruled the southern part of the old empire, but saw themselves as rightful heirs to the whole realm. Similarly, in the West a Byzantine Empire (so called because its capital, Constantinople, stood on the site of the earlier Greek city Byzantium) ruled the eastern part of the old Roman Empire but claimed its entirety (Figure 6.8).

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quotes#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#the east#the west#splitting#china#eastern jin dynasty#empire#rightful heir#byzantine empire#constantinople#byzantium#roman empire#division

0 notes

Photo

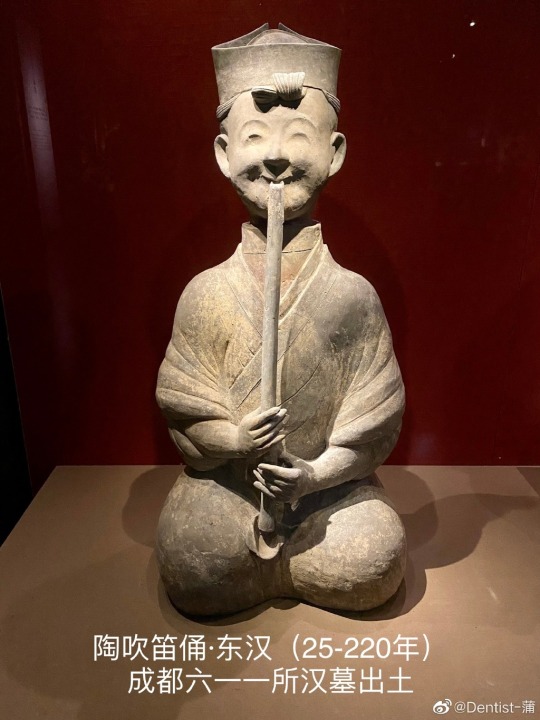

【Historical Artifacts Reference 】:

China Eastern Han Dynasty Playing Qin Pottery Figurine

China Eastern Han Dynasty Playing the Dizi(Chinese flute) Pottery Figurine

China Wei and Jin Dynasties "person who conveys official documents and letters" Mural Bricks

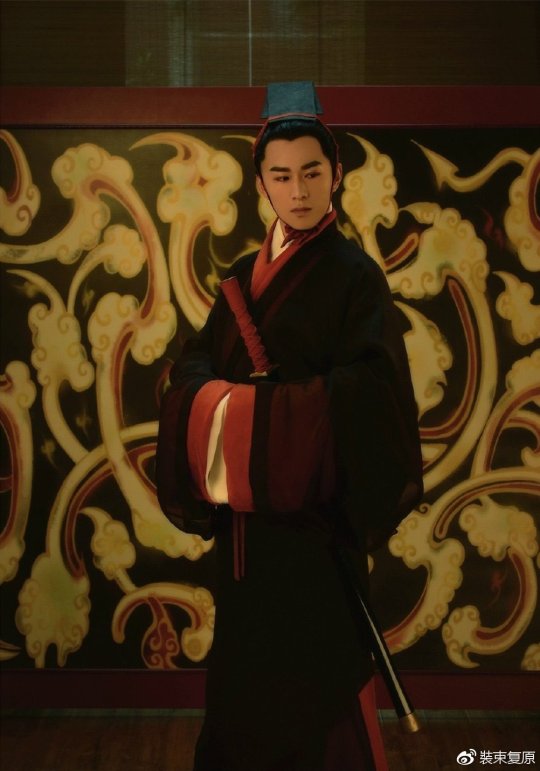

[Hanfu・漢服]Chinese Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 A.D.) Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Headwear

—–

【History Note】

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, men's attire was usually wider than the Western Han Dynasty period, which was more convenient for activities.The collocation of wearing Jie Zhi(介帻) and straight train robes(直裾袍服) is favored by scholars at the time.

This set of attire for the scholars/literati of the Eastern Han Dynasty is wearing a Jie Zhi /介帻 on head, with a purple brocade border cotton robe, red silk cotton trousers, waering a yellow gauze on the outermost layer, and a brocade pouch around the waist.

At the time, the fashion of wearing gauze robe was still popular, which looked elegant and dignified, without losing the beauty of agility and elegance.

This set of attire has existed among the literati until the Wei and Jin Dynasties.

————————

📝Recreation Work : @裝束复原

👗 Hanfu: @桑纈

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1656910125/MdvaOoRei

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 A.D.)#hanfu#hanfu history#hanfu accessories#chinese traditional clothing#chinese historical fashion#chinese history#Chinese Costume#chinese costume history#Chinese Culture#artifacts#Wei and Jin Dynasties#裝束复原#桑纈#漢服#汉服#Jie Zhi(介帻)#直裾袍服

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

INTERESTING

men’s hanfu

line 1 - line 5 :Han Dynasty

line 1 - line 3 : Western Han

line 4 - line 5 :Eastern Han

line 6 : Wei and Jin Dynast

line 7 - line 8 : Northern Song Dynasty

#hanfu#mens hanfu#mens headwear#hats#runway#history#reference#Han dynasty#western han dynasty#Eastern Han dynasty#wei/jin dynasties#Song dynasty#Northern Song#Coser小梦

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

直裾战国袍 / Straight-edged Warring States robe: Distinguished by the excessive amount of fabric for the sleeves and the waist-to-floor straight edge, this style of Warring States robe was worn between the Warring States period and the Han Dynasty.

Warring States robes can usually be purchased in 2 lengths; - trailing on the floor (great for photos, awful for walking) - hemmed right at the floor (not as beautiful in photos, a lot easier for walking) Most stores selling this style of robes have skipped the extra piece of fabric between the sleeve and body, changing the entire drape of the fabric. Instead of it naturally opening at the front, this small change in the design causes the fabric to be completely closed at the front which makes walking without stepping on the fabric impossible (speaking from personal experience) T___T

==**==**==**==**==**==**==**==

Hanfu, the historical clothing of the Han people in China, has thousands of years of history. Since the 2000s, there has been a revival of Hanfu within China, with many Hanfu stores opening in the past two decades.

I first became aware that I could purchase Hanfu in 2021 and hoarded a bunch. Recently, I started digging more and more into the topic and realized that, while many of the Hanfu being sold are beautiful, they're not exactly true to the styles of Hanfu in the past. That's not to say they shouldn't be sold or worn, I'm not interested in gatekeeping what others wear, but I became intrigued by what exactly DID the historical Hanfu styles look like based on historical artefacts.

For my own interest, and for any others who might be interested, I'm going to try and do a series of the various Hanfu styles throughout the dynasties.

Chinese dynasties timeline for reference:

Shang Dynasty 商 (1300–1046 BC) Zhou Dynasty 周 (1046–256 BC) Western Zhou 西周 (1046–771 BC) Eastern Zhou 东周 >> Spring and Autumn Period 春秋 (770–481 BC) >> Warring States Period 战国 (481–221 BC) Qin Dynasty 秦 (221–207 BC) Han Dynasty 汉 >> Western Han 西汉 (206 BC–8 AD) >> Xin Dynasty 新 (9–23) >> Eastern Han 东汉 (25–220) Three Kingdoms 三国 (220–265) Jin Dynasty 晋 >> Western Jin 西晋 (265–316) >> Eastern Jin 东晋 (317–420) Northern and Southern Dynasties 南北朝 (420–589) Sui Dynasty 隋 (581–618) Tang Dynasty 唐 (618–907) Five Dynasties 五代 (907–960) Song Dynasty 宋 >> Northern Song 北宋 (960–1127) >> Southern Song 南宋 (1127–1279) Yuan Dynasty (Mongols) 元 (1271–1368) Ming Dynasty 明 (1368–1644) Qing Dynasty (Manchus) 清 (1644–1911) Republic of China 民国 (1912–1949) People's Republic of China 中华人民共和国 (1949-present)

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 13, Xi'an, China, Shaanxi Archaeology Museum/陕西考古博物馆 (Part 4 - Sui and Tang dynasties):

This is another star of the museum, a Tang dynasty (618 - 907 AD) bronze mirror, the back of which is decorated with carved luodian/螺钿 (mother of pearl). Near the edge are various birds, while the inner ring is arranged in a "sunflower" shape. Kinda wish I can see a modern replica of this one without all these marks and discolorations from the passage of time:

A Tang dynasty yupei/玉佩 (jade pendant). Unlike the Western Zhou dynasty yupei in part 2, this type is most definitely supposed to be hung from the waist. This one in particular was one of a set of two (both worn on waist, one on each side), and these were part of the formal wear of first to fifth rank officials during Tang dynasty:

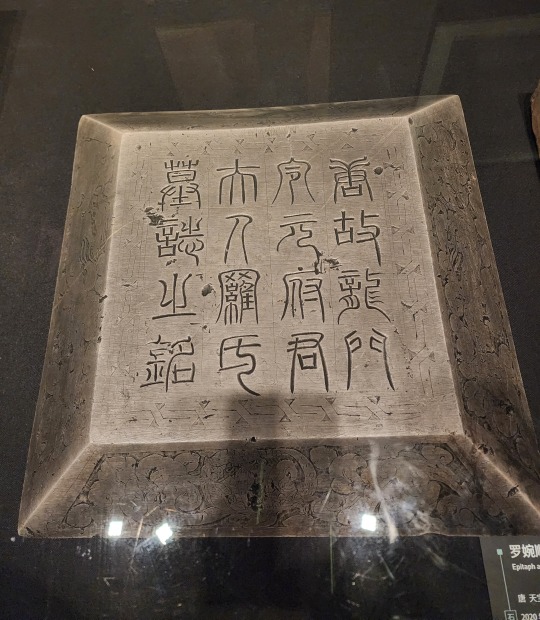

Luo Wanshun's Epitaph/罗婉顺墓志. As mentioned in the first Beilin museum post, ancient Chinese epitaphs have a two-piece structure, consisting of a tablet and the protective covering on top. This is the protective covering on top, with the large inscription identifying this as the epitaph stone of Luo Wanshun, engraved in seal script/zhuanshu/篆书:

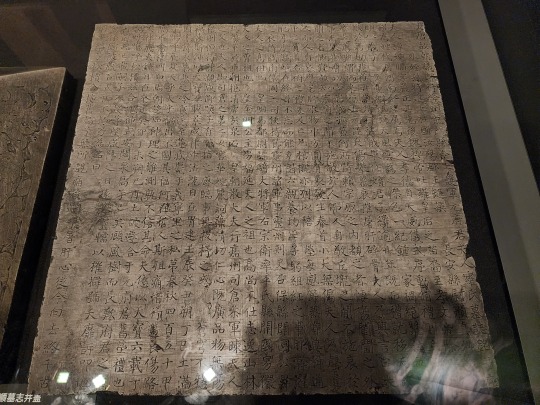

And here's the actual body of the epitaph. This particular epitaph was drafted by one of the "Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup"/饮中八仙, Li Jin/李琎 (he was also the nephew of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang/唐玄宗), and the calligraphy was provided by the famous calligrapher Yan Zhenqing/颜真卿:

Tang-era pottery figurines of the Chinese zodiac animals. This set is sadly incomplete, but the way these zodiac animals are partially anthropomorphized is pretty interesting. From left to right, these are tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, sheep, and dog (yep that is a dog head, apparently). Not sure why rabbit and dog figurines are missing their ears though, maybe the ears broke off and are lost?

Sui dynasty (581 - 618 AD) green-glazed boshanlu/博山炉 incense burner. Note the panlong/蟠龙 dragon curled around the base:

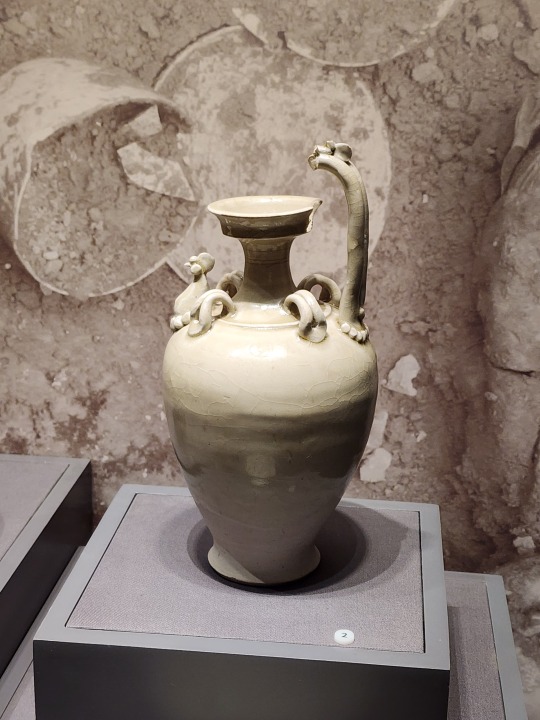

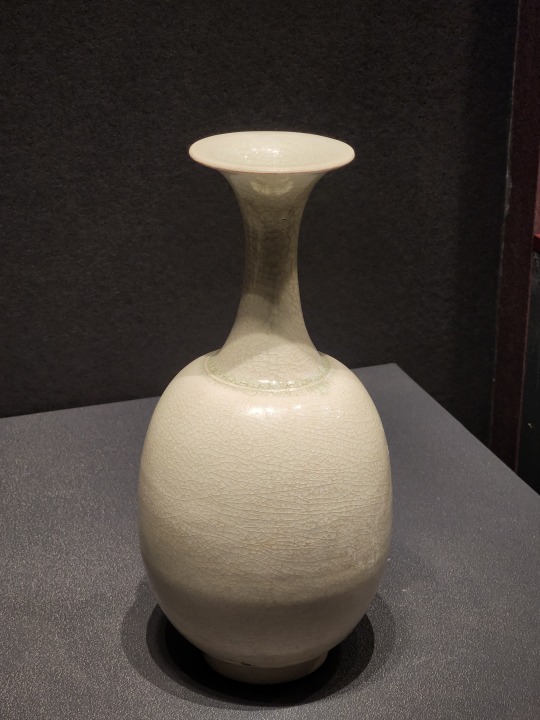

Left: Sui dynasty white-glazed ewer with a chicken head-shaped handle. Right: Sui dynasty white-glazed vase. The curves on this one is *chef kiss*

More Sui dynasty white glazed pottery, but the most incredible thing is the white porcelain cup in the middle. The lip of that cup is 1mm (~1/32 in) thick, and the sides are so thin, it's almost see through:

Tang-era sancai/三彩 glazed conjoined flasks that is shaped like a pair of fish. Similar twin-fish motif can be found in numerous traditional Chinese holiday decor, and symbolize auspiciousness, wealth, and surplus--especially surplus, since fish in Chinese (鱼) is pronounced yú, and "surplus" in Chinese (余) is also pronounced yú. This is why the phrase 年���有余 ("may there be a surplus every year") is often paired up with imagery of carps, children holding giant carps, or a twin-fish motif.

Absolutely beautiful Tang-era wall mural of a tiger, which was very sadly damaged over time. But from the pieces left, you can still appreciate the raw power of the tiger captured by these lines:

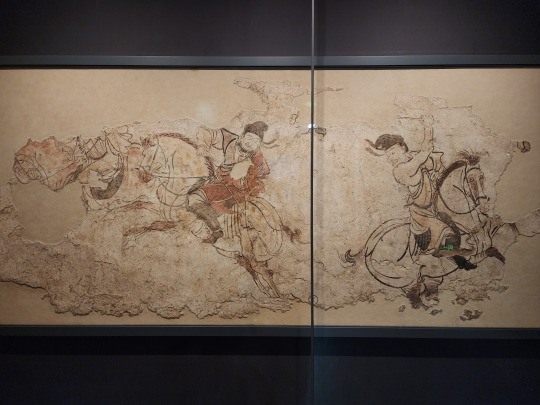

Another beautiful Tang-era wall mural depicting men on horseback playing "polo", called maqiu/马球 (lit. "horse ball") in Chinese. It's unclear whether the maqiu depicted here originated in China in late Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD) or was brought to China via the Silk Road at the beginning of Tang dynasty, but anyway this sport was very popular during Tang dynasty, and there were many female players at the time too.

The women of Tang dynasty as depicted by pottery figurines:

A small model of Tang-era triple que/阙 gate towers. Que gate towers first appeared in Western Zhou dynasty (1046 - 771 BC) and have been a part of Chinese architecture ever since. Que gate towers usually come in pairs, one on each side of the gate, and they were used to display status.

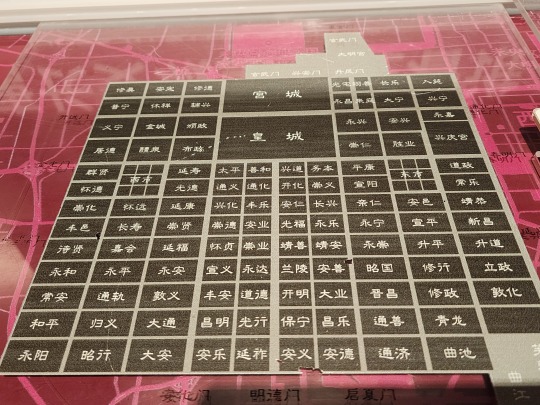

A map of Tang dynasty Chang'an city laid on top of the current map of Xi'an city, showing the imperial palace (top center), the East Market/东市 and West Market/西市, and the 108 districts (called fang/坊):

A Tang-era chiwen/鸱吻 (螭吻 is the original name, 鸱吻 is the alternative name, another alternative name is 蚩吻, but the pronunciation remains the same for all three) roof ornament. These are the pairs of horn-shaped pieces on the top of the roof of traditional Chinese architecture. These ornaments are made to represent the Ninth Son of the Dragon, called Chiwen/螭吻, which looks like a dragon-headed fish and has the power to control water, thus it's used in traditional Chinese architecture to ward off fires:

Sui-era gold gilded handle of a stone sarcophagus:

A pottery jar found buried in the tomb of Crown Prince Jiemin/节愍太子 (Li Chongjun/李重俊, son of Emperor Zhongzong of Tang/唐中宗 Li Xian/李显), partially shaped like a pagoda and decorated with various Buddhist motifs such as lotus petals and elephant heads. This is speculated to be a representation of a granary, which would hold grains for the crown prince in the afterlife:

And last but not least, a Sui-era pottery camel bearing sacks that have the imagery of the Greek god of wine Dionysus upon them, which shows the great amount of cultural exchange that took place back then:

#2024 china#xi'an#china#shaanxi archaeology museum#chinese history#chinese culture#sui dynasty#tang dynasty#chinese calligraphy#calligraphy#archaeology#history#culture

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did Hua Cheng name his house after Xie Lian's famous saying?

There's a pretty widely circulated post in the tgcf fandom saying that Hua Cheng named his manor Paradise Manor in direct reference to Xie Lian's famous saying "Body in the abyss, heart in paradise". This is a misinterpretation due to translation. Hua Cheng likely did name Paradise Manor after the famous saying, but the "paradise" in paradise manor is meant to be the opposite of "abyss".

Paradise Manor in the original text is 极乐坊, where the phrase 极乐 ji2 le4 is translated as paradise. Actually, this is a translation of Sanskrit Sukhāvatī, and in Buddhism it is often translated as the pure land, or the land of bliss, in which the faithful may be reborn.

Xie Lian's famous saying is translated as "body in the abyss, heart in paradise", and the important translations are the word choice of abyss and paradise. Paradise, here is a translation of 桃源 tao2 yuan2, which literally means peach [blossom] spring. This is a direct reference to a text written during the Eastern Jin Dynasty by Tao Yuanming (陶渊明) called 《桃花源记》 "The Tale of the Peach Blossom Spring". The text tells a tale that takes place during the reign of Xiao Wudi 孝武帝 (376-397 CE) of the Jin Dynasty, in which a fisherman finds a mysterious cave with a peach blossom spring in it, in which a population of people had lived there since escaping the turmoil of the Qin Dynasty several centuries prior, and who were so removed from the world in their little community that they had never heard of the Han Dynasty which followed the Qin, or the Three Kingdoms period that followed, and certainly not the Jin. Thus I would argue this phrase 桃源 should be translated as heart in utopia and not heart in paradise. At the very least, this paradise is NOT the same paradise as Hua Cheng's paradise.

But, it's not a baseless belief that Hua Cheng named his house after Xie Lian's motto, and this is where the abyss comes in. This is a translation of 无间 wu2 jian1 which refers to Avīcinaraka, also Sanskrit and also a Buddhist concept. This is a level of hell in which those who have committed the ten unforgivable crimes are reborn, and it is sometimes translated into English as interminable, or incessant, because the suffering hear has no gaps -- it is incessant. In that way, 极乐 and 无间 the paradise and the abyss between Hua Cheng and Xie Lian form a more direct parallel, both originating as Buddhist concepts describing where a person may be reborn based on their behavior in their past life, and this is a clearer paired set of concepts than the two being compared in Xie Lian's original motto. So I believe it truly can be said that Hua Cheng named Paradise Manor for Xie Lian, but not in the way that those who only read the English might think -- those two "paradises" are actually very different concepts.

#hualian#tgcf#tian guan ci fu#hua cheng#xie lian#heaven official's blessing#tgcf meta#translation meta

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Empress of China (throwback)

Today I want to do a throwback to a 2019 piece I did of Empress Li from the Chinese Jin Dynasty (266-420 AD). Chroniclers described her as "tall and black", characteristics for which the Emperor's concubines mocked her. Nonetheless, she would proceed to give birth to the Emperor Xiao Wu (r. 373-396 AD). It's anyone's guess where Empress Li came from, but I like to think it was somewhere in eastern Africa, especially since they tend to have taller stature than either Indian or Asian Negrito people in addition to being dark-skinned.

Sources:

#ancient china#chinese#jin dynasty#african#black woman#woman of color#dark skin#bipoc#woc#history#digital art#art

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Liu Shan’s religious heresy:

Today, the Wuhou Shrine (dedicated to the honor and worship of Zhuge Liang) is a part of Liu Bei’s royal temple (Zhaolie Emperor Temple), but the Wuhou Shrine actually began its life as a royal-commissioned temple, a rather controversial temple both during its construction and for hundreds of years afterwards, because an emperor is only supposed to commission temples for gods and royal ancestors. According to Han Dynasty rituals (and the Eastern Han court had a whole debate about this at one point to settle the issue), an emperor is to build temples for gods, the emperors who founded his dynasties, and his own direct line of forefathers (limited to just five generations above him), and that’s it. The greatest posthumous honor a government official can receive both before and after Liu Shan’s time, was to have his memorial tablet featured in an imperial temple (配享太庙), to “share” in the worship of the emperor. Even having his own shrine in a royal temple was unthinkable.

Liu Shan however, became the only emperor in all of Chinese history to commission a WHOLE NEW INDEPENDENT TEMPLE for a subject, Zhuge Liang.

Immediately after Zhuge Liang’s death, some court officials proposed building a temple to honor him but were met with resistance from conservative officials who noted, correctly, that it was against orthodox Han dynasty religious rites. Liu Shan asked for the court to hold an official debate to discuss the issue, the court could not come to an agreement, and the issue was shelved for 30 years. In the passing decades, subjects across the Shu-Han kingdom built private shrines and temples to honor Zhuge Liang (this practice is called “private worship” 私祭 or “improper worship” 淫祭), which was tolerated but not officially sanctioned by the royal court. 30 years later, the issue was raised at court again, and this time, Liu Shan simply signed off on it without a debate.

The Wuhou Temple was originally built next to Zhuge Liang’s grave in Dingjun Mountain, and completed before the fall of the Shu-Han Kingdom. The temple was moved to Chengdu during the end of the Western Jin Dynasty and rebuilt next to Liu Bei’s royal temple. In the Ming Dynasty, the grounds of the two temples were merged into one, forming the Zhaolie Temple / Wuhou Shrine which still exist in this form today.

Liu Shan was criticized over the next hundred years for commissioning a temple for Zhuge Liang because it violated the proper rites of royal worship. And this was a big deal because ancient people genuinely believed that the emperor’s ability to properly conduct religious duties would protect the kingdom from natural disasters and crop failures. Stuffy old men in the Song dynasty, who otherwise respected or even revered Zhuge Liang, were still bitching about Liu Shan’s heresy for building a temple for a subject.

#romance of the three kingdoms#rot3k#three kingdoms#liu shan#zhuge liang#fleshing out some thoughts I shared with a mutual while discussing potential Liu Shan x Zhuge Liang fics

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Buddhism in Ancient Korea

Buddhism, in Korean Bulgyo, was introduced by monks who visited and studied in China and then brought back various Buddhist sects during the Three Kingdoms period. It became the official state religion in all Three Kingdoms and subsequent dynasties, with monks often holding important advisory roles in governments. Korean Buddhism came to be much more inclusive than in other cultures with significant attempts made by important Buddhist scholars to reconcile the many diverging branches of the religion. Buddhism would have a profound influence on Korean art, literature, and architecture from bells to pagodas, ceramics, sculpture, and even developments in printing techniques.

Introduction From China

According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced first to the kingdom of Goguryeo (Koguryo) in 372 CE, followed by Baekje (Paekche) in 384 CE, and finally in the Silla kingdom between 527 and 535 CE. The first monk to bring Buddhist teachings was Sundo, who was sent for that purpose by the ruler of Eastern Qin, Fu Jian. It was hoped that stronger cultural ties with Goguryeo would lead to more practical cooperation in meeting the military threat posed by hostile Manchurian tribes. A decade later, Marananta, an Indian or Serindian monk, came from the Eastern Jin state and taught Buddhism in the Baekje kingdom. In both states, the new faith received a favourable reception. In the Silla kingdom, though, Buddhism was seen as a threat to the traditional religions of shamanism, animism, and ancestor worship, and not until the martyrdom of the monk Ichadon was Buddhism finally accepted and then promoted by the royal court.

Continue reading...

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Treasures of the Study · 文房四宝

蒲一永 Pu Yi Yong · The Brush

Eight Principles of Yong. Traditionally, it was believed that practicing the eight common strokes in regular script, all of which can be found in the character "Yong," could lead to writing all characters well. According to legend, it was created by Wang Xizhi in the Eastern Jin Dynasty, "Yong" is also the first character in his famous work 蘭亭集序 Lantingji Xu (Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion). The surname "Pu" could potentially be a homage to the famous Chinese writer Pu Songling in the Qing Dynasty. In his most popular work 聊齋誌異 Liaozhai Zhiyi (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio), the focus of the tales are on the emotional entanglements between humans and supernatural beings in the world.

陳楮英 Chen Chu Ying · The Paper

Chu, which refers to the paper mulberry plant, was historically used in ancient China as the raw material for making mulberry paper and Xuan paper. Additionally, "Chu" was used as a term synonymous with paper in ancient times. In EP4, Chuying mentioned that the "chu" in her name means paper.

曹光硯 Cao Guang Yan · The Inkstone

Yan, also known as Yantai, is the name of the inkstone used in calligraphy. The inkstone is used to grind the ink stick into powder, which is then mixed with water on the inkstone to create ink suitable for calligraphy.

執念 The Obsessions · The Ink

The obsessions are one of the ever-changing elements in the show, the elegiac couplets are uniquely written with whole heart and mind for the different obsessions.

#oh no! here comes trouble#oh no here comes trouble#不良執念清除師#不良执念清除师#twdramaedit#asiandramasource#dailyasiandramas#cdramasource#dramasource#twdrama#taiwanese drama#caps#chinese stuff#pu yiyong#Tseng Jing Hua#chen chuying#vivian sung#sung yun hua#Peng Cian You#cao guangyan#i dont even know if this is even interesting to anyone im just splurging thoughts and random meta#this post took 10yrs to make can you believe trying to do the write up was harder than trying to make the gifs#half way through making the gifs i realised i did it in simplified and when i tried to switch to traditional the font didnt work 🥴#i was trying to find a scene where guangyan was in his doctor action but i didnt want to use the cpr scene bc sads#this is he best one i could find where he's wearing a lab coat

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Late Warring States period(475–221 BC) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Based On Chu (state)Historical Artifacts

【Historical Artifact Reference】:

Late Warring States period(475–221 BC):Two conjoined jade dancers unearthed from Jincun, Luoyang,collected by Freer Museum of Art

A similar jade dancer was also unearthed from the tomb of Haihunhou, the richest royal family member in the Han Dynasty, and was one of his treasures.

Warring States period, Eastern Zhou dynasty, 475-221 BCE,jade dancer by Freer Gallery of Art Collection.

Warring States period(475–221 BC)·Silver Head Figurine Bronze Lamp.Unearthed from the Wangcuo Tomb in Zhongshan state during the Warring States Period and collected by the Hebei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology

The figurine of a man dressed as a woman holds a snake in his hand, and 3 snakes correspond to 3 lamps.

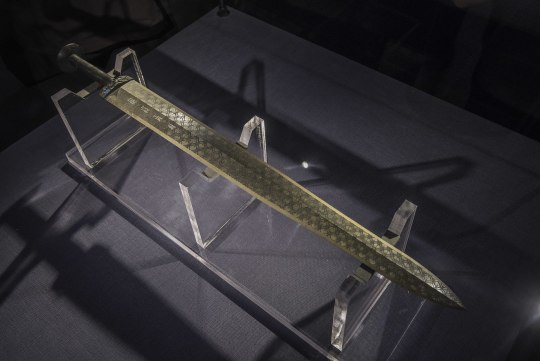

Sword of Goujian/越王勾践剑:

The Sword of Goujian (Chinese: 越王勾践剑; pinyin: Yuèwáng Gōujiàn jiàn) is a tin bronze sword, renowned for its unusual sharpness, intricate design and resistance to tarnish rarely seen in artifacts of similar age. The sword is generally attributed to Goujian, one of the last kings of Yue during the Spring and Autumn period.

In 1965, the sword was found in an ancient tomb in Hubei. It is currently in the possession of the Hubei Provincial Museum.

【Histoty Note】Late Warring States Period·Noble Women Fashion

The attire of noblewomen in the late Warring States period, as reconstructed in this collection, is based on a comprehensive examination of garments and textiles unearthed from the Chu Tomb No. 1 at Mashan, Jiangling, as well as other artifacts from the same period.

During the late Warring States period, both noble men and women favored wearing robes that were connected from top to bottom. These garments were predominantly made of gauze, silk, brocade, and satin, with silk edging. From the Chu Tomb No. 1 at Mashan, there were discoveries of robes entirely embroidered or embroidered fragments. The embroidery technique employed was known as "locked stitches," which gave the patterns a three-dimensional, lively appearance, rich in decoration.

The two reconstructed robes in this collection consist of an inner robe made of plain silk with striped silk edging, and an outer robe made of brocade, embroidered with phoenixes and floral patterns, with embroidered satin edging. Following the structural design of clothing found in the Mashan Chu Tomb, rectangular fabric pieces were inserted at the junction of the main body, sleeves, and lower garment of the robe. Additionally, an overlap was made at the front of the main body and the lower garment to enlarge the internal space for better wrapping around the body curves. Furthermore, the waistline of the lower garment was not horizontal but inclined upward at an angle, allowing the lower hem to naturally overlap, forming an "enter" shape, facilitating movement.

The layered edging of the collars and sleeves of both inner and outer robes creates a sense of rhythm, with the two types of brocade patterns complementing each other, resulting in a harmonious effect. Apart from the robes, a wide brocade belt was worn around the waist, fastened with jade buckle hooks, and adorned with jade pendants, presenting an elegant and noble figure.

The reconstructed hairstyle draws inspiration from artifacts such as the jade dancer from the late Warring States period unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun Tomb in Nanchang, and the jade dancer from the Warring States period unearthed at Jin Village in Luoyang. It features a fan-shaped voluminous hairdo on the crown, with curled hair falling on both sides, and braided hair gathered at the back. The Book of Songs, "Xiao Ya: Duren Shi," vividly depicts the flowing curls of noblewomen during that period. Their images of curly-haired figures in long robes were also depicted in jade artifacts and other relics, becoming emblematic artistic representations.

The maturity and richness of clothing art in the late Warring States period were unparalleled in contemporary world civilizations, far beyond imagination. It witnessed the transition of Chinese civilization into the Middle Ages. The creatively styled garments and intricate fabric patterns from the Warring States period carry the unique essence, mysterious imagination, and ultimate romanticism of that era, serving as an endless source of artistic inspiration.

--------

Recreation Work by : @裝束复原

Weibo 🔗:https://weibo.com/1656910125/O6cUMBa1j

--------

#chinese hanfu#Late Warring States Period#Warring States period(475–221 BC)#hanfu#hanfu accessories#chinese traditional clothing#hanfu_challenge#chinese#china#historical#historical fashion#chinese history#china history#漢服#汉服#中華風#裝束复原

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

责子 - Admonishing (my) sons

by 陶渊明 (Tao Yuanming, ~365 - 427)

白发被两鬓 肌肤不复实 bái fà bèi liǎng bìn jī fū bù fù shí White hair greys both temples, skin sags, no longer firm -

虽有五男儿 总不好纸笔 suī yǒu wǔ nán ér zǒng bù hǎo zhǐ bǐ though blessed with five boys, none have love for paper and brush.

阿舒已二八 懒惰故无匹 ā shū yǐ èr bā lǎn duò gù wú pǐ A-Shu now twice eight, is so lazy none can compare.

阿宣行志学 而不爱文术 ā xuān xíng zhì xué ér bù ài wén shù A-Xuan, coming to fifteen where others pursue study, dislikes all things literary.

雍端年十三 不识六与七 yōng duān nián shí sān bù shí liù yǔ qī Yong and Duan, aged thirteen, find strangers in the numbers six and seven.

通子垂九龄 但觅梨与栗 tōng zi chuí jiǔ líng dàn mì shí lízi yǔ lì Tongzi who is nearly nine, seeks only pears and chestnuts

天运苟如此 且进杯中物 tiān yùn gǒu rú cǐ qiě jìn bēi zhōng wù Now if Heaven’s will is truly thus, drink up, whatever’s in the cup

………………………………………………………………………………………….

Notes

(translations below are all mine):

This is a homework poem - from many weeks back xD - that I’d like to share. It’s by Tao Yuanming, a poet whose lifetime spanned the late Eastern Jin Dynasty and early Liu Song Dynasty.

I really like his writing, and one thing I appreciate a lot about it is that he (usually) writes very plainly, but if we think about it a little, we can uncover hidden delights! He’s also just a very cute* person in general, which I think is what makes reading his works such a pleasure xD It also feels quite safe leaving this poem without any commentary because of the above mentioned quality of his writing - perhaps the only thing that needed some clarification was 志学, which was glossed in the translation anyway.

So! Feel free to leave a message and tell me if I’m right, and also what you spot!

Also, as Jing said in the chat, tag yourself! Which lazy kid are you? :P

Oh and Tao Yuanming is a super famous writer of the Northern and Southern Dynasties actually, so you can probably look him up very easily if you want to. I’m just trying something different with him where I want to go through all of his works, and then go snooping through other people’s writing about his life.

* I said he was very cute earlier. Here is proof in his 归园田居·其三 Retiring to Fields and Home (part three).

种豆南山下 - Planting beans ‘neath the Southern Mountains, 草盛豆苗稀 - weeds abound, while the seedlings are sparse. 晨兴理荒秽 - Rising with the dawn to cull the weeds, 带月荷锄归 - retiring with the moon and a shouldered hoe; 道狭草木长 - the paths are narrow, the grasses tall, 夕露沾我衣 - and the evening dew dampens my clothes. 衣沾不足惜 - But dampened clothes aren’t worth lamenting, 但使愿无违 - so long as my ideals and actions, aligned, remain.

When he’s in a lighthearted mood, he likes to raise his readers’ expectations or tease at something and then reveal a hilarious twist. And often it’s very good naturedly self deprecating without being disparaging or underselling himself, so you laugh with him but not at him.

For example, in an earlier part (Part Two) of the above poem, he talks about the peaceful rural retirement with down-to-earth neighbours and the things he is doing with his land. Then in part three, he starts off with a romantic-ish image only to dash it immediately with the next paired line, stated soooooo proudly. It gets funnier with every addition as you realise how hard he worked to get that result. But then there is a twist again - he says, all this and he doesn’t mind! Why not? Because it was his choice. Bro is truly committing to the unworldly farming life.

…Anyway, there are six parts to 归园田居. I highly recommend reading it all if you can because I’m totally not doing him any justice xD

For all of y’all who can read Chinese with a bit of help, here is another piece of his writing related to his kids. They make quite a number of cameos in his other poems, but I chose this one because it's actually addressed to them! He was writing in anticipation of the birth of his first son - if internet sources are to be believed.

Note: Veryyyyyyy rough, first draft-y sort of translation. I was just trying to get the meaning across as easily as possible.

命子 - Guidance for my son 悠悠我祖 爰自陶唐 邈焉虞宾 历世重光 御龙勤夏 豕韦翼商 穆穆司徒 厥族以昌 Long, long ago, my ancestor lived; Yao, who was of Tao and Tang. In the distant past, honoured at Yu, Danzhu paved glory for generations after. Surnamed Yulong, they served in Xia, as Shiwei, were wings to Shang; Great Minister over the Masses, Tao Shu led our clan’s rise.

纷纷战国 漠漠衰周 凤隐于林 幽人在丘 逸虬绕云 奔鲸骇流 天集有汉 眷予愍侯 The chaos of the Warring States, the fall of weakened Zhou; the Feng fades into his forest, hermits retire to their mountains. The Qiulong winds through cloud, whales ride monstrous waves; heaven-blessed was the coming of Han, it favoured Marquis Min.

於赫愍侯 运当攀龙 抚剑风迈 显兹武功 书誓河山 启土开封 亹亹丞相 允迪前踪 Illustrious Marquis Min; the time for him and his Emperor just arrived. Sword in hand against the wind, he achieved impressive martial feats. Fulfilling his lord's promise of everlasting glory, he was bestowed land, titles. And a tireless, diligent Chancellor followed in the footsteps of his father. 浑浑长源 蔚蔚洪柯 群川载导 众条载罗 时有语默 运因隆窊 在我中晋 业融长沙 The gushing of a river long from its source, the luxuriance of towering trees; all streams began from somewhere, all branches grow from some trunk. There is time to speak or be silent, for fortune has sharp vicissitudes; In our Jin at its zenith, Changsha’s brilliant achievements shined.

桓桓长沙 伊勋伊德 天子畴我 专征南国 功遂辞归 临宠不忒 孰谓斯心 而近可得 The fearsome, heroic Duke Huan of Changsha, with outstanding merits and virtue upon whom the Son of Heaven bestowed a hereditary title, leads wars in the South. Victory achieved, he retires home, unwavering despite glory and favour. Who dares say that such a heart can be easily found in recent times?

肃矣我祖 慎终如始 直方二台 惠和千里 於皇仁考 淡焉虚止 寄迹风云 冥兹愠喜 Rigorous he was, my grandfather, careful to the end as he was at the start. Fair and upright was his influence at Court; wisdom spread through his lands. Praiseworthy was my late fathers benevolence, though he sought no fame. He gave himself to Office and took both gain and loss with equanimity.

嗟余寡陋 瞻望弗及 顾惭华鬓 负影只立 三千之罪 无后为急 我诚念哉 呱闻尔泣 Lamenting my ignorance, I look to my ancestors, unable to reach their heights. I was ashamed, for despite my greying hair, alone in my family I stand. Among three thousand crimes, gravest - to leave no descendants. Over this I was deeply worried… until I heard your babbling cries.

卜云嘉日 占亦良时 名汝曰俨 字汝求思 温恭朝夕 念兹在兹 尚想孔伋 庶其企而 Observing the portents on this good day, divining this to be a good time, I named you Yan, gave you the courtesy name of Qiusi. Be respectful and aspiring day or night; remember well your name as Kong Ji remembered his. Such is my wish for you.

厉夜生子 遽而求火 凡百有心 奚特于我 既见其生 实欲其可 人亦有言 斯情无假 A diseased man’s son was born at night; with lamp and urgency he went to check. Every person, being ordinary, would have such a worry; I am no different. Witnessing your birth, truly, I wish for your future success. Though something often said by man, the sentiment in this is sincere and true.

日居月诸 渐免于孩 福不虚至 祸亦易来 夙兴夜寐 愿尔斯才 尔之不才 亦已焉哉 Days and months will pass swiftly, my son will leave childhood behind. Fortune's roots are always there, disaster also easily arrives. Be diligent: rise early, sleep late; may you be blessed with talent and success. But if you do not, then alas, though that is also fine.

(Referenced this source and this one for annotations)

I thought the intertwining of the imagined past and illustrious connections with traceable ancestors, grandparents and parents was a very charming way of expressing this narrative. Especially so when you think about the way the whole longass grandmother story is told shapes the message to his son! Noticing his efforts to emphasize the great achievements that could come about because of opportunity and fortune right after his rather soul stirring introduction (Parts 1 and 2) was DELIGHTFUL and actually very touching.

What makes a man good? Diligence, steadiness and dedication to doing what is good and right. What makes a man great? First, opportunity i.e. luck, but also, most importantly - strength of character - not losing sight of his heart despite power or fame.

All that leads up to his concluding verses - that it's human nature for parents to wish sincerely that their children will do well, so that their own regrets in life do not repeat. But the world is so unpredictable! Just do your best to lay the foundations for fortune when it arrives, then let things happen as they will, and let's be contented whatever the outcome.

Just taking his attitude at face value, what an un-stressful way to live life :D !!!!!!!!

And after reading this poem, how do you feel about Admonishing Sons that we started with in this post? GO read it again!

I love him so much.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coffee shop AU part 2

It was 08:05 P.M. Mitsuri was five minutes late to meet him at his tiny apartment. Maybe she decided meeting what was relatively a stranger at his place was a bad idea. Obanai’s scalp itched as his mind ran through the possibilities. Maybe she was lost. Should he go out and look for her or call? Maybe she was playing a practical joke on him. Maybe- He shook his head to banish the anxious thoughts.

Mitsuri asked to watch a movie with him, specifically. Her brother was not even in the front of the cafe when she asked. Besides, she was not the type of woman to play with people’s emotions. She wore her heart on her sleeve.

Obanai glanced over his living room again to ensure nothing was out of place. He moved Kaburamaru’s enclosure in his room tonight, so the glare of the heat lamp wouldn’t alter how the television’s screen looked. There was a bowl of popcorn, movie theater candies, and strawberry soda on the coffee table.

Knock, Knock.

He rubbed his hands on his pants to wipe up the sweat forming as he stood up. Obanai walked to the door and opened it. Mitsuri stood holding four bags of snacks and drinks.

“Hey, sorry for running late, I stopped by the convenience store a block away. I wasn’t sure what all you liked, so I grabbed a little of everything,” she said and smiled shyly.

“It’s okay. I was worried that you got lost,” he said and stepped aside to let her in. Mitsuri was here in his apartment. The girl he obsessed over for the last two months was here in his apartment. It stunned him that she was here. He led her to the kitchen to unload the bags.

“I know your coffee order by heart, but not what you like to eat. I may have gone overboard,” Mitsuri said as she set the bags down and started pulling items out. Jerky sticks, chocolates, gummy worms, red licorice ropes, nerds, chex mix, chips, ice cream bars, and other random selections. She might as well have bought the whole store. “I know you like floral flavors, but they didn’t have any lavender or sakura flavored snacks.” She kept talking, but the words failed to register.

Mitsuri went to the trouble of buying all of this for a man she hardly knew. They only spent maybe a total of an hour talking to each other in two months. The majority of it was Obanai ordering coffee. The other part was asking about Mitsuri’s family, friends, and hobbies. He hardly shared any personal information, yet here she was because she wanted to get to know him. If he wasn't already completely infatuated with her before, he was now.

“I like black licorice,” Obanai said finally.

“I bought some!” Mitsuri said and her hands flew to another bag to pull out the bitter candy. She beamed as she handed it over. “Now I know for the future.” She was already planning to see him again? His face heated up and he turned his head to the side. She was so cute. He couldn’t handle it.

“So, what movie did you want to watch?” He asked.

“The Butterfly Lovers,” Mitsuri said and opened her shoulder bag to pull out a DVD. The cover looked like it was a drama with a man and woman standing back to back. Honestly, he would not be paying much attention to the movie with Mitsuri sitting next to him. “Are you ready to watch it?” He nodded.

—--

Obanai was hyper aware of every movement Mitsuri made as she sat next to him. He sat at one end of the couch and her on the other. During the film, she slowly inched her way towards him. Whether it was a conscious or subconscious decision, Obanai could not be sure. Now, her knees were nearly touching his. If he were to reach out, he could graze her bare knees. He swallowed and tried to focus on the screen.

The movie was nearly over. It was about Zhu Ying Tai, a woman who disguised herself as a man to study at a boarding school during the Eastern Jin Dynasty. During her education she met Liang Shan Bo, a poor, but industrious man who failed to realize her true gender. They bond over their love of learning and Zhu finds herself falling in love with him. Three years pass and near the end of their time together, Zhu is summoned back to her parents’ home. She reveals she is a woman to Liang and they confess their love with the promise for him to visit her and family. He gifts her a butterfly hairpin to solidify his promise.

When she returns home, her parents explain she is engaged to a rich merchant that her family is indebted to. When she marries the merchant, her family will be released from all of their debts. A week later Liang visits and officially meets Zhu as a woman. He is stunned by her beauty. Before she can explain the new circumstances, he proposes marriage. With tears in her eyes Zhu tells him she is promised to someone else. She tells him she made a mistake by asking him to come. She hands him a piece of her hair and returns the butterfly hairpin and tells him she no longer loves him. Liang is heart broken and leaves the estate.

At this point, Obanai looked over at Mitsuri. Tears streamed down her face and she sniffed quietly. He passed her a tissue and she took it gratefully. She dabbed her tears as the final act began.

A month passes in the movie. It shows the two lovers lamenting over their school days and what could have been. On the day of Zhu’s wedding, she receives a letter from Liang where he expresses his love one last time and says he’ll be dead by the time she reads it. The butterfly pin accompanies the letter. Zhu tucks the letter and hair pin into her top and her wedding procession starts. On the way, Zhu sees her ex lover’s grave and stops to pay her respects. She apologizes for lying and pledges her undying devotion to him even in death. Thunder clatters and his grave opens up. Zhu leaps forward to join Liang in death. Their spirits emerge as a pair of butterflies, so they can never be separated again. A soft, sweet melody played as the credits rolled.

Obanai blinked away the tears that formed at the corners of his eyes. Due to several misunderstandings, the lovers could not be together in life. He swallowed, but in death they were reunited. Emptiness settled in Obanai’s gut as he turned to look at Mitsuri. Her face was red from crying and her eyes were puffy. She blew her nose into the tissue before she tossed it onto the table. Obanai handed her another, their hands grazing each other.

“I’ve watched this movie so many times and I still cry like a baby at the end, sorry,” Mitsuri said, her voice cracking. Obanai shifted his feet. He had never been good at comforting sensitive people.

“It’s okay,” he murmured. “You can cry all you want, I won’t judge you,” he said. Mitsuri grabbed his arm and hugged it to her chest as she buried her face into his shoulder. He froze, unsure of what to do. The woman he liked was crying into his shoulder and hugging his arm. Hesitantly, he raised his free hand and gently patted her shoulder. Would it be too cliche to say, ‘There, there’?

Mitsuri nuzzled into his shoulder harder and a sob escaped her. “Zhu cared so much for her family, she gave up her chance at love,” she sobbed. Her tears soaked his t-shirt now. “Do you think you would be able to do that?”

“No,” Obanai answered immediately. He would never give up his lover for his family. Mitsuri lifted her head and met his gaze in a silent question. “My family, well, they’re not good people,” he said. His dad beat him and his mother ignored him growing up. Mitsuri didn’t need to learn all of his baggage on their first date. Wait-was this a date? They never clarified whether it was or not. He cleared his throat. “What about you?”

Mitsuri bit her lip. “I can’t say. I love my family and our life, but um,” she said and laid her forehead on Obanai’s shoulder again. “I’ve never been in love, or at least I don’t think I have.”

His heart rate quickened. Why did she have to be so adorable? He raised his hand to her hair and stroked the pink locks. “I’ve never been in love either,” Obanai admitted. It was easier to talk when she wasn’t looking directly at him.

“You haven’t?” Mitsuri said. Before he could respond, the credits broke and showed the modern day. Zhu appeared on screen waiting in line at a coffee shop. When she came up to the counter, Liang was waiting to take her order. They smiled, recognizing each other as past lovers and the screen went black.

Obanai’s eyes widened and nearly choked. Embarrassment flooded his senses. He knew exactly how the characters felt the first time he saw Mitsuri smile at him from over the cafe’s counters. Mitsuri shrieked and scooted away from him.

“Sorry, I forgot the after credits scene. This is really embarrassing,” Mitsuri said in a hurry and waved a hand in front of her. Obanai pursed his lips when he realized he missed the feeling of her leaning into his shoulder.

“A little,” he admitted before deciding to take a metaphorical leap into the grave. “When I first saw you at the cafe I wanted to ask you out, but I was too shy. I like you a lot, probably more than I should-”

Mitsuri’s lips pressed against his before he could say anything else. She tasted like cream soda, popcorn, and salt from her tears. His heart soared as he caressed her face and hair. This was not what he expected from tonight, but he was thankful. They broke the kiss.

“I like you too, Obamai,” she said dreamily. “Obanai!” Mitsuri corrected herself. She could call him whatever she wanted and he would be happy as long as they were together.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

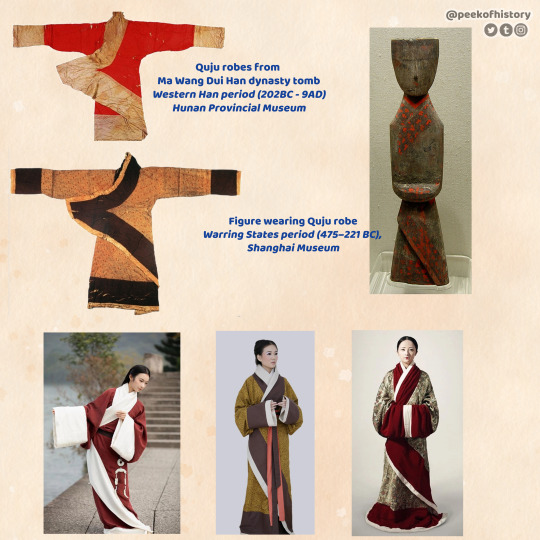

Quju robes are identified by the diagonal cut of the fabric at the front. It was worn around the same time period as the straight-edged Zhiju robes (直裾).

There are actually various types of Quju, some with curved sleeve bottoms, some are straight, some have thin collars, others are thick, etc. but they all share the same diagonal cut, with the fabric being wrapped around the body when worn.

For anyone interested in actually purchasing Hanfu for wear, Quju and Zhiju robes are AMAZING for fall/winter weather. You can wear multiple layers underneath, you can even throw a sweater and jeans underneath and no one would know. In the summer, however, the heavy and excessive fabric makes it feel like you're wearing a portable sauna 🥵🥵

==**==**==**==**==**==**==**==

Hanfu, the historical clothing of the Han people in China, has thousands of years of history. Since the 2000s, there has been a revival of Hanfu within China, with many Hanfu stores opening in the past two decades.

I first became aware that I could purchase Hanfu in 2021 and hoarded a bunch. Recently, I started digging more and more into the topic and realized that, while many of the Hanfu being sold are beautiful, they're not exactly true to the styles of Hanfu in the past. That's not to say they shouldn't be sold or worn, I'm not interested in gatekeeping what others wear, but I became intrigued by what exactly DID the historical Hanfu styles look like based on historical artefacts.

For my own interest, and for any others who might be interested, I'm going to try and do a series of the various Hanfu styles throughout the dynasties.

Chinese dynasties timeline for reference:

Shang Dynasty 商 (1300–1046 BC) Zhou Dynasty 周 (1046–256 BC) Western Zhou 西周 (1046–771 BC) Eastern Zhou 东周 >> Spring and Autumn Period 春秋 (770–481 BC) >> Warring States Period 战国 (481–221 BC) Qin Dynasty 秦 (221–207 BC) Han Dynasty 汉 >> Western Han 西汉 (206 BC–8 AD) >> Xin Dynasty 新 (9–23) >> Eastern Han 东汉 (25–220) Three Kingdoms 三国 (220–265) Jin Dynasty 晋 >> Western Jin 西晋 (265–316) >> Eastern Jin 东晋 (317–420) Northern and Southern Dynasties 南北朝 (420–589) Sui Dynasty 隋 (581–618) Tang Dynasty 唐 (618–907) Five Dynasties 五代 (907–960) Song Dynasty 宋 >> Northern Song 北宋 (960–1127) >> Southern Song 南宋 (1127–1279) Yuan Dynasty (Mongols) 元 (1271–1368) Ming Dynasty 明 (1368–1644) Qing Dynasty (Manchus) 清 (1644–1911) Republic of China 民国 (1912–1949) People's Republic of China 中华人民共和国 (1949-present)

#hanfu#chinese hanfu#china#chinese culture#chinese history#汉服#fashion#historical fashion#clothing#quju#曲裾

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 14, Xi'an, China, Shaanxi History Museum, Qin and Han Dynasties Branch (Part 3 – Innovations and Philosophies):

(Edit: sorry this post came out so late, I got hit by the truck named life and had to get some rest, and this post in itself took some effort to research. But anyway it's finally up, please enjoy!)

A little background first, because this naming might lead to some confusions.....when you see location adjectives like "eastern", "western", "northern", "southern" added to the front of Zhou dynasty, Han dynasty, Song dynasty, and Jin/晋 dynasty, it just means the location of the capital city has changed. For example Han dynasty had its capital at Chang'an (Xi'an today) in the beginning, but after the very brief but not officially recognized "Xin dynasty" (9 - 23 AD; not officially recognized in traditional Chinese historiography, it's usually seen as a part of Han dynasty), Luoyang became the new capital. Because Chang'an is geographically to the west of Luoyang, the Han dynasty pre-Xin is called Western Han dynasty (202 BC - 8 AD), and the Han dynasty post-Xin is called Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD). As you can see here, in these cases this sort of adjective is simply used to indicate different time periods in the same dynasty.

Model of a dragonbone water lift/龙骨水车, Eastern Han dynasty. This is mainly used to push water up to higher elevations for the purpose of irrigation:

Model of a water-powered bellows/冶铁水排, Eastern Han dynasty. Just as the name implies, as flowing water pushes the water wheel around, the parts connected to the axle will pull and push on the bellows alternately, delivering more air to the furnace for the purpose of casting iron.

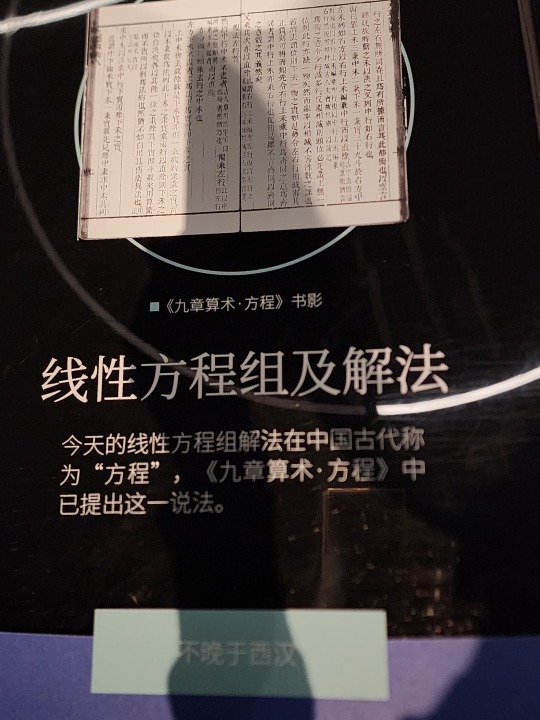

The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art/《九章算术》, Fangcheng/方程 chapter. It’s a compilation of the work of many scholars from 10 th century BC until 2 nd century AD, and while the earliest authors are unknown, it has been edited and supplemented by known scholars during Western Han dynasty (also when the final version of this book was compiled), then commented on by scholars during Three Kingdoms period (Kingdom of Wei) and Tang dynasty. The final version contains 246 example problems and solutions that focus on practical applications, for example measuring land, surveying land, construction, trading, and distributing taxes. This focus on practicality is because it has been used as a textbook to train civil servants. Note that during Han dynasty, fangcheng means the method of solving systems of linear equations; today, fangcheng simply means equation. For anyone who wants to know a little more about this book and math in ancient China, here’s an article about it. (link goes to pdf)

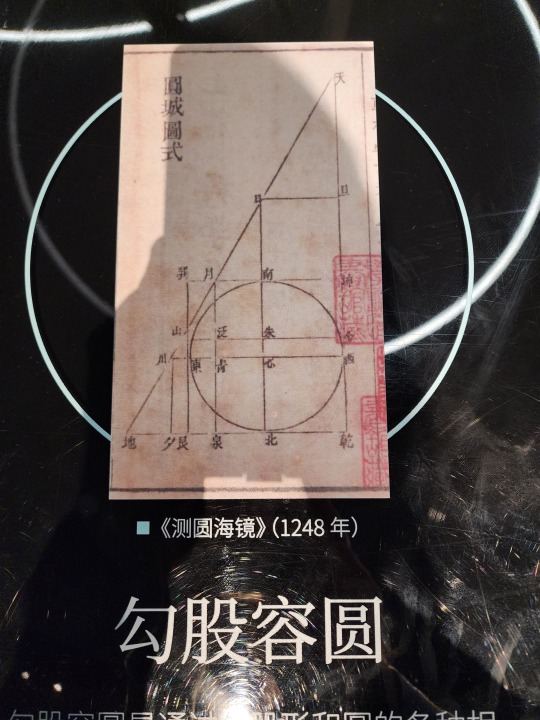

Diagram of a circle in a right triangle (called “勾股容圆” in Chinese), from the book Ceyuan Haijing/《测圆海镜》 by Yuan-era mathematician Li Ye/李冶 (his name was originally Li Zhi/李治) in 1248. Note that Pythagorean Theorem was known by the name Gougu Theorem/勾股定理 in ancient China, where gou/勾 and gu/股 mean the shorter and longer legs of the right triangle respectively, and the hypotenuse is named xian/弦 (unlike what the above linked article suggests, this naming has more to do with the ancient Chinese percussion instrument qing/磬, which is shaped similar to a right triangle). Gougu Theorem was recorded in the ancient Chinese mathematical work Zhoubi Suanjing/《周髀算经》, and the name Gougu Theorem is still used in China today.

Diagram of the proof for Gougu Theorem in Zhoubi Suanjing. The sentence on the left translates to "gou (shorter leg) squared and gu (longer leg) squared makes up xian (hypotenuse) squared", which is basically the equation a² + b² = c². Note that the character for "squared" here (mi/幂) means "power" today.

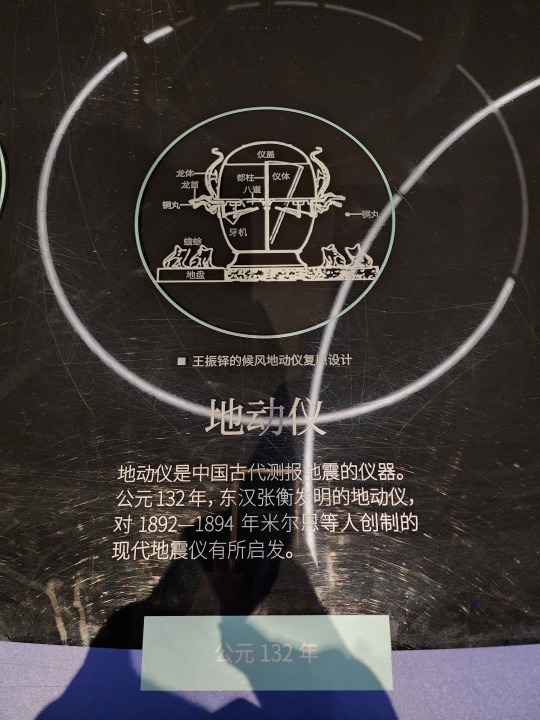

This is a diagram of Zhang Heng’s seismoscope, called houfeng didong yi/候风地动仪 (lit. “instrument that measures the winds and the movements of the earth”). It was invented during Eastern Han dynasty, but no artifact of houfeng didong yi has been discovered yet, this is presumably due to constant wars at the end of Eastern Han dynasty. All models and diagrams that exist right now are what historians and seismologists think it should look like based on descriptions from Eastern Han dynasty. This diagram is based on the most popular model by Wang Zhenduo that has an inverted column at the center, but this model has been widely criticized for its ability to actually detect earthquakes. A newer model that came out in 2005 with a swinging column pendulum in the center has shown the ability to detect earthquakes, but has yet to demonstrate ability to reliably detect the direction where the waves originate, and is also inconsistent with the descriptions recorded in ancient texts. What houfeng didong yi really looks like and how it really works remains a mystery.

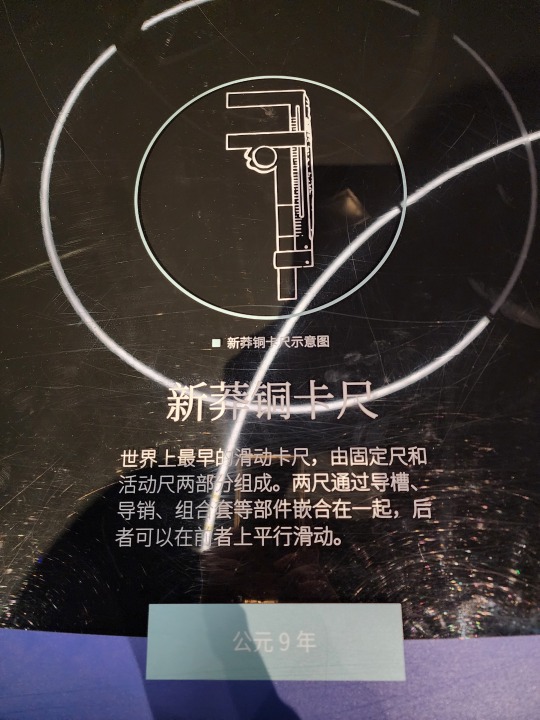

Xin dynasty bronze calipers, the earliest sliding caliper found as of now (not the earliest caliper btw). This diagram is the line drawing of the actual artifact (right).

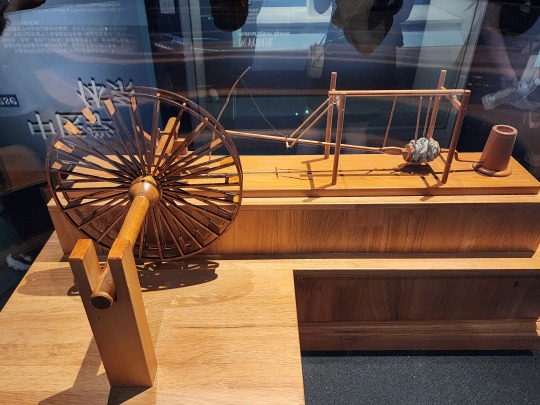

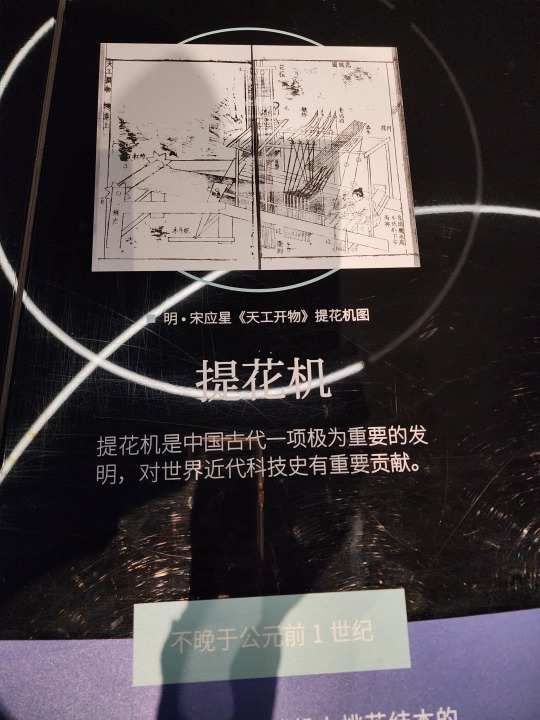

Ancient Chinese "Jacquard" loom (called 提花机 or simply 花机 in Chinese, lit. "raise pattern machine"), which first appeared no later than 1st century BC. The illustration here is from the Ming-era (1368 - 1644) encyclopedia Tiangong Kaiwu/《天工开物》. Basically it's a giant loom operated by two people, the person below is the weaver, and the person sitting atop is the one who controls which warp threads should be lifted at what time (all already determined at the designing stage before any weaving begins), which creates patterns woven into the fabric. Here is a video that briefly shows how this type of loom works (start from around 1:00). For Hanfu lovers, this is how zhuanghua/妆花 fabric used to be woven, and how traditional silk fabrics like yunjin/云锦 continue to be woven. Because it is so labor intensive, real jacquard silk brocade woven this way are extremely expensive, so the vast majority of zhuanghua hanfu on the market are made from machine woven synthetic materials.

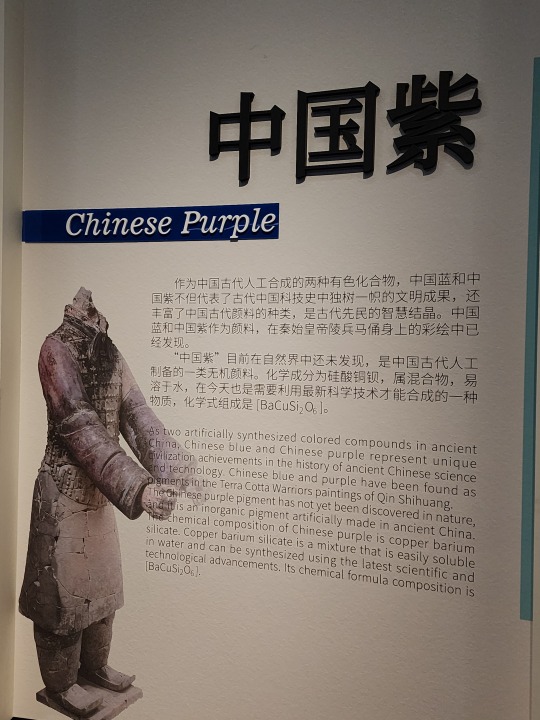

Chinese purple is a synthetic pigment with the chemical formula BaCuSi2O6. There's also a Chinese blue pigment. If anyone is interested in the chemistry of these two compounds, here's a paper on the topic. (link goes to pdf)

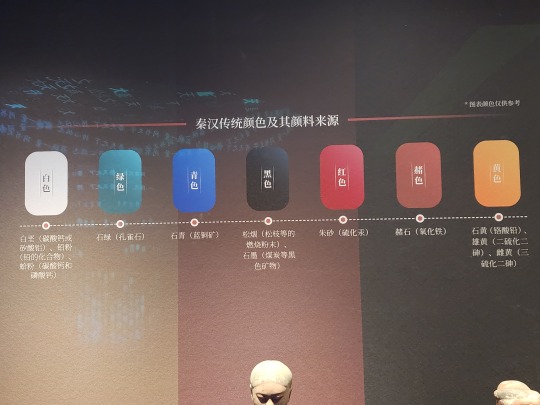

A list of common colors used in Qin and Han dynasties and the pigments involved. White pigment comes from chalk, lead compounds, and powdered sea shells; green pigment comes from malachite mineral; blue pigment usually comes from azurite mineral; black comes from pine soot and graphite; red comes from cinnabar; ochre comes from hematite; and yellow comes from realgar and orpiment minerals.

Also here are names of different colors and shades during Han dynasty. It's worth noting that qing/青 can mean green (ex: 青草, "green grass"), blue (ex: 青天, "blue sky"), any shade between green and blue, or even black (ex: 青丝, "black hair") in ancient Chinese depending on the context. Today 青 can mean green, blue, and everything in between.

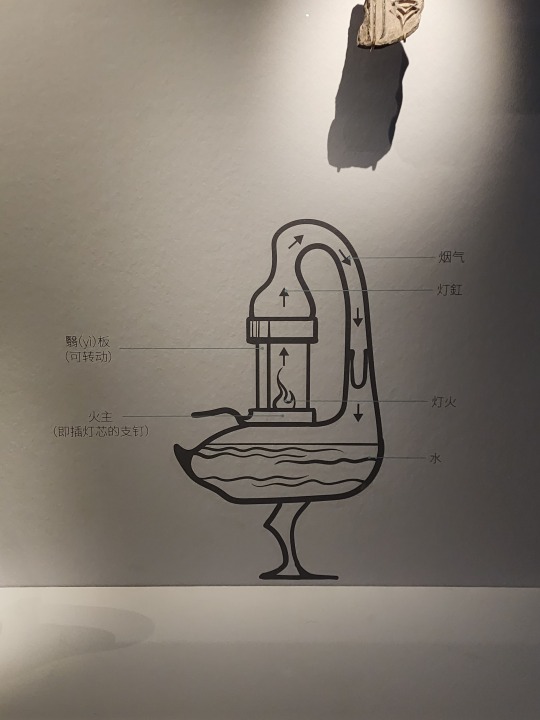

Western Han-era bronze lamp shaped like a goose holding a fish in its beak. This lamp is interesting as the whole thing is hollow, so the smoke from the fire in the lamp (the fish shaped part) will go up into the neck of the goose, then go down into the body of the goose where there's water to catch the smoke, this way the smoke will not be released to the surrounding environment. There are also other lamps from around the same time designed like this, for example the famous gilt bronze lamp that's shaped like a kneeling person holding a lamp.

Part of a Qin-era (?) clay drainage pipe system:

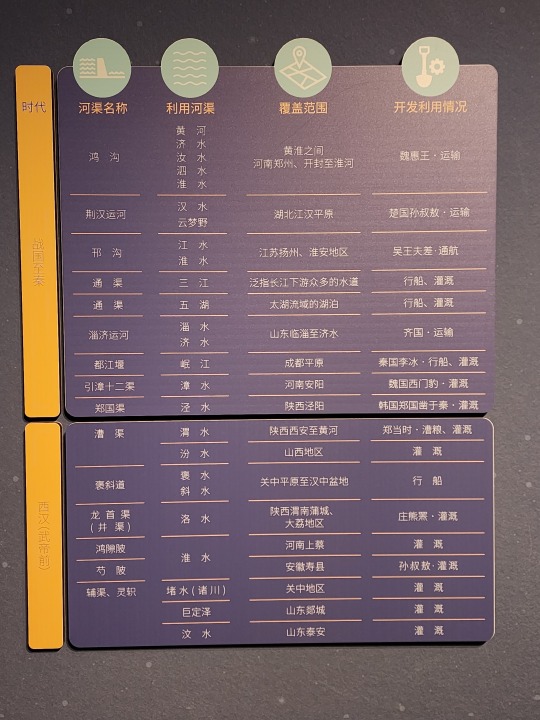

A list of canals that was dug during Warring States period, Qin dynasty, and pre-Emperor Wu of Han Han dynasty (475 - 141 BC). Their purposes vary from transportation to irrigation. The name of the first canal on the list, Hong Gou/鸿沟, has already become a word in Chinese language, a metaphor for a clear separation that cannot be crossed (ex: 不可逾越的鸿沟, meaning "a gulf that cannot be crossed").

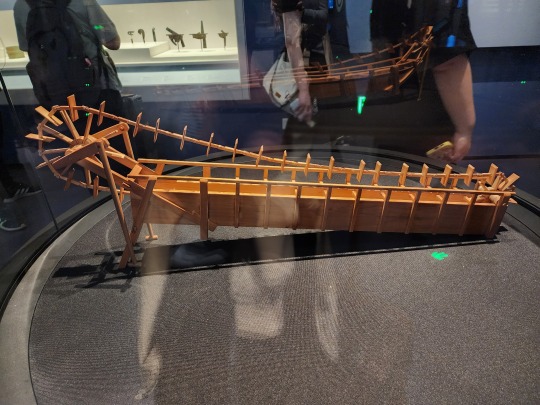

Han-era wooden boat. This boat is special in that its construction has clear inspirations from the ancient Romans, another indication of the amount of information exchange that took place along the Silk Road:

A model that shows how the Great Wall was constructed in Qin dynasty. Laborers would use bamboo to construct a scaffold (bamboo scaffolding is still used in construction today btw, though it's being gradually phased out) so people and materials (stone bricks and dirt) can get up onto the wall. Then the dirt in the middle of the wall would be compressed into rammed earth, called hangtu/夯土. A layer of stone bricks may be added to the outside of the hangtu wall to protect it from the elements. This was also the method of construction for many city walls in ancient China.

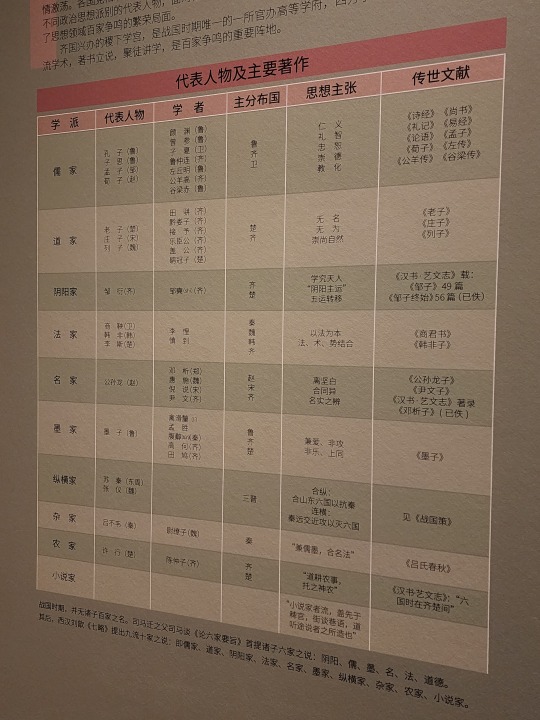

A list of the schools of thought that existed during Warring States period, their most influential figures, their scholars, and their most famous works. These include Confucianism (called Ru Jia/儒家 in Chinese; usually the suffix "家" at the end denotes a school of thought, not a religion; the suffix "教" is that one that denotes a religion), Daoism/道家, Legalism (Fa Jia/法家), Mohism/墨家, etc.

The "Five Classics" (五经) in the "Four Books and Five Classics" (四书五经) associated with the Confucian tradition, they are Shijing/《诗经》 (Classic of Poetry), Yijing/《易经》 (also known as I Ching), Shangshu/《尚书》 (Classic of History), Liji/《礼记》 (Book of Rites), and Chunqiu/《春秋》 (Spring and Autumn Annals). The "Four Books" (四书) are Daxue/《大学》 (Great Learning), Zhongyong/《中庸》 (Doctrine of the Mean), Lunyu/《论语》 (Analects), and Mengzi/《孟子》 (known as Mencius).

And finally the souvenir shop! Here's a Chinese chess (xiangqi/象棋) set where the pieces are fashioned like Western chess, in that they actually look like the things they are supposed to represent, compared to traditional Chinese chess pieces where each one is just a round wooden piece with the Chinese character for the piece on top:

A blind box set of small figurines that are supposed to mimic Shang and Zhou era animal-shaped bronze vessels. Fun fact, in Shang dynasty people revered owls, and there was a female general named Fu Hao/妇好 who was buried with an owl-shaped bronze vessel, so that's why this set has three different owls (top left, top right, and middle). I got one of these owls (I love birds so yay!)

And that concludes the museums I visited while in Xi'an!

#2024 china#xi'an#china#shaanxi history museum qin and han dynasties branch#chinese history#chinese culture#chinese language#qin dynasty#han dynasty#warring states period#chinese philosophy#ancient technology#math history#history#culture#language

90 notes

·

View notes