#depending on the preceding consonant

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

That POG moment when a language's /w/ patterns as velar

#inspired by: kinyarwanda consonant clusters#wherein apparently /w/ is prestopped in clusters with one of [k ɡ ŋ]#depending on the preceding consonant#language#linguistics

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a Welsh question if that’s okay: if you have a word that might change when followed by a vowel (like gyda[g]) and a word that might change when preceded by a vowel (like [f]e) which one would take precedence? Would you go for gydag e or gyda fe?

... oh, wow, I have literally never thought about this. You've challenged me with this one! Hmm, let's see.

In the case of this specific example it's gydag ef to be formal, but gyda fe is completely acceptable outside of a formal or literary setting. Let's see, what other examples are there? Hmm.

Okay. So, as stated, a quirk of Welsh is that it really hates putting two vowels together, hence you sometimes get this fun Wandering Consonant. I can think of many common examples of ending changes: y/yr, a/ac, etc. But actually, the only real example I can think of where the start changes is fe, actually (or fo if you're northern.)

So, after a quick check, I think I have an answer. The original (very old and literary) Welsh male pronoun is actually efe - these days only seen in some old hymns, really, as it kind of evolved away with Middle Welsh becoming Modern Welsh. So, it would be abbreviated to e, ef or fe all the time depending on context.

Traditionally, the first syllable was kept - hence, literary Welsh still uses gydag ef. But, oral Welsh will happily use fe (thinking about it I hear a lot of "Mae fe'n mynd" in oral Welsh these days, rather than "Mae e'n mynd"), which means as long as you're speaking informally, there's no longer any need to alter the gyda.

I do not know how this works out with the Gogs developing "o/fo". Insert your favourite 'Gogs talk funny' joke here, and enjoy being pelted with tomatoes when they catch you.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ancestors of modern Ukrainians lived in dozens of premodern and modern principalities, kingdoms, and empires, and in the course of time they took on various names and identities. The two key terms that they used to define their land were “Rus” and “Ukraine”. (In the Cyrillic alphabet, Rus’ is spelled Русь: the last character is a soft sign indicating palatalized pronunciation of the preceding consonant.) The term “Rus’,” brought to the region by the Vikings in the ninth and tenth centuries, was adopted by the inhabitants of Kyivan Rus’, who took the Viking princes and warriors into their fold and Slavicized them. The ancestors of today’s Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians adopted the name “Rus” in forms that varied from the Scandinavian/Slavic “Rus” to the Hellenized “Rossiia.” In the eighteenth century, Muscovy adopted the latter form as the official name of its state and empire. The Ukrainians had different appellations depending on the period and region in which they lived: Rusyns in Poland, Ruthenians in the Habsburg Empire, and Little Russians in the Russian Empire. In the course of the nineteenth century, Ukrainian nation builders decided to end the confusion by renouncing the name “Rus” and clearly distinguishing themselves from the rest of the East Slavic world, especially from the Russians, by adopting “Ukraine” and “Ukrainian” to define their land and ethnic group, both in the Russian Empire and in Austria-Hungary. The name “Ukraine” had medieval origins and in the early modern era denoted the Cossack state in Dnieper Ukraine. In the collective mind of the nineteenth-century activists, the Cossacks, most of whom were of local origin, were the quintessential Ukrainians. To link the Rus’ past and the Ukrainian future, Mykhailo Hrushevsky called his ten-volume magnum opus History of Ukraine-Rus’. Indeed, anyone writing about the Ukrainian past today must use two or even more terms to define the ancestors of modern Ukrainians. (..) Since the independent Ukrainian state’s creation in 1991, its citizens have all come to be known as “Ukrainians,” whatever their ethnic background.

Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian Pronunciation

You can give me a tip on Ko-fi if you like this post ☺️ Researching and writing this kind of posts takes time (and my Russian lessons come at a cost), so any amount of support would be greatly appreciated.

Vowels

Although Russian has ten vowel letters (а, е, ё, и, о, у, ы, э, ю, я), there are only five vowel sounds, as they are grouped in pairs according to whether they are hard or soft:

а - я (a - ja) [a] - [ʲa]/[ʲæ]

э - е (e - je) [ɛ] - [ʲe]

ы - и (y - i) [ɨ] - [ʲi]

о - ё (o - jo) [o] - [ʲɵ]

у - ю (u - ju) [u] - [ʲu]/[ʲʉ]

Soft vowels (second column) make the preceding consonant soft. When found in unstressed syllables, some vowels undergo reduction:

о immediately before the stress → а [ɐ]: окно́ [ɐkˈno], Москвá [mɐskˈva]

о and а after the stress and more than one syllable before the stress → [ə]: ко́смос [ˈkosməs], лáмпа [ˈɫampə], хорошо́ [xərɐˈʂo], карандáш [kərɐnˈdaʂ]

е and я right before the stress → и [ʲɪ]: сестрá [sʲɪˈstra], язы́к [ʲɪˈzɨk]

е after the stress and more than one syllable before the stress → [ʲɪ]: но́мер [ˈnomʲɪr], семена́ [sʲɪmʲɪˈna]

я after the stress and more than one syllable before the stress → [ʲɪ]/[ʲə]: де́сять [ˈdʲesʲɪtʲ], вре́мя [ˈvrʲemʲə], языкозна́ние [(j)ɪzɨkɐzˈnanʲɪje]

у before and after the stress → ʊ: мужчи́на [mʊˈɕːinə], Бо́гу [ˈboɣʊ]

Я undergoes another sound change. Reflexive verb endings such as -ться and -тся are pronounced -ца [t͡sə]. For example, учиться [ʊˈt͡ɕit͡sːə], одева́ется [ɐdʲɪˈva(j)ɪt͡sə].

Consonants

Russian consonants also form pairs, depending on whether they are voiced or voiceless:

б - п (b - p) [b] - [p]

в - ф (v - f) [v] - [f]

г - к (g - k) [ɡ] - [k]

д - т (d - t) [d] - [t]

ж - ш (zh - sh) [ʐ] - [ʂ]

з - с (z - s) [z] - [s]

Voiced consonants (first column) at the end of words become voiceless:

б -> [p]: лоб [ɫop]

в -> [f]: о́стров [ˈostrəf]

г -> [k]: ма́ркетинг [ˈmarkʲɪtʲɪnk]

д -> [t]: наро́д [nɐˈrot]

ж -> [ʂ]: муж [muʂ]

з -> [s]: зака́з [zɐˈkas]

When voiced and voiceless consonants are adjacent, the nature of the second consonant determines that of the first:

voiced + voiceless -> voiceless + voiceless: ю́бка [ˈjupkə]

voiceless + voiced (except в) -> voiced + voiced: сде́лать [ˈzʲdʲeɫətʲ]

There are also four unpaired voiced consonants:

л (l) [ɫ]

м (m) [m]

н (n) [n]

р (r) [r]

And four unpaired voiceless consonants:

х (kh) [x]

ц (ts) [t͡s]

ч (ch) [t͡ɕ]

щ (shch) [ɕː]

Consonants have an additional distinction: they can be soft or hard. Soft consonants are palatalized and thus pronounced as if y [ʲ] followed them.

й [j], ч [t͡ɕ], and щ [ɕː] are always soft or palatalized.

ж [ʐ], ш [ʂ], and ц [t͡s`] are always hard or unpalatalized.

All other consonants can be either soft or hard depending on the letter following them. Palatalization typically occurs in these cases:

Before soft vowels (е, ё, и, ю, я): апте́ка [ɐpˈtʲekə], ребёнок [rʲɪˈbʲɵnək], мини́стр [mʲɪˈnʲistr], костю́м [kɐsʲˈtʲum], ку́хня [ˈkuxnʲə]

Before the soft sign (ь): конь [konʲ]

In many loanwords, consonants are not palatalized before е, e.g., тест [tɛst].

The hard sign (ъ) is rarely used and indicates the hardness of the preceding consonant. So, even if the consonant is followed by a soft vowel, it still reads hard: объе́кт [ɐbˈjekt], съёжиться [ˈsjɵʐɨt͡sə], синъицю́ань [sʲɨˈnʲit͡sʲuʌnʲ], адъю́нкт [ɐˈdjunkt], объя́ть [ɐbˈjætʲ]. Ъ is often added after prefixes.

In the genitive pronoun его and endings -его and -ого, г is pronounced as в [v]: его́ [(j)ɪˈvo], моего́ [mə(j)ɪˈvo], но́вого [ˈnovəvə]. They can also appear in compound words, such as the word for “today” which literally means “this day”: сего́ + дня = сего́дня [sʲɪˈvodʲnʲə]. This only applies to endings and not when -его and -ого are part of the word’s stem, e.g., мно́го [ˈmnoɡə].

Г also changes its pronunciation before ч, becoming х [x] in two words and their derivatives, лёгкий [ˈlʲɵxʲkʲɪj] and мягкий [ˈmʲæxʲkʲɪj].

Ч is pronounced as ш [ʂ] before н and т: конечно [kɐˈnʲeʂnə], что [ʂto].

Some consonant clusters are simplified by dropping one of the consonants, e.g., расще́лина [rɐˈɕːelʲɪnə]. Dental stops are dropped between a dental consonant and a dental lateral or nasal one: со́лнце [ˈsont͡sə], се́рдце [ˈsʲert͡sə].

The cluster -вств- is pronounced -ств- [stv] in the words здра́вствуй(те) [ˈzdrastvʊj(tʲe)], чу́вство [ˈt͡ʃu̟fstvo], and безмо́лвствовать [bʲɪzˈmoɫstvəvətʲ].

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started watching the @letshaveabouba livestream on youtube, I'm 2 streams in and its really nice! the only bad thing is that because its a recording of a livestream I can't really add my input or share my ideas so I'm gonna blurt it all here.

The proto inventory they came up with is this:

In their documentation they put /a/ as a low central vowel, so its a classic 5 without /e/, but I decided for me I'll make it a square system, it'll make vowel stuff easier for me - so /i/ /u/ high, /æ/ (a for ease) /ɔ/ (/o/ for ease). I also interpreted the back consonants as +pharyngeal, and split the back non stops as one being a fricative and thr other an approximant, instead of having both be both.

regarding syllable structure, they came up with CCVT. I elaborated on it and made it #CC-VCCV-T#, which stands for:

initial cluster of any 2 different consonants allowed. yes, every cluster, even /jqa/ is allowed, but /tta/ is not.

intervocallic clusters of any 2 different consonants allowed, no 3 or more consonants in a row. so /aqba/ but not /ut.ska/

word finally only single consonants allowed, and specifically only alveolars. /klat/ not /pgum/

regarding sound changes, they talked about tone, and having epinthetic vowels breaking up initial clusters and vowel lowering. These are the sound change I came up with to achieve these goals, and some other stuff that seemed cool to me:

Tonogenesis: high tone after voiceless consonants, low tone after voiced. A voiceless consonant preceded by a voiced one gives low tone, and voiced preceded by voiceless gives high tone: /tá/, /dà/, /ntà/, /kná/. Im pretty sure something similar happens in tibetan, but it has aspiration involved, and im not going to have that, so this is only inspired by it.

voicing assimilation: stops and fricatives assimilate to the voicing of a following consonant of the same cluster. now tone is phonemic :) yay: /kná/ > /gná/, /ztì/ > /stì/, but /ntì/, /lsì/ stay as is.

pharyngeal spreading: a consonant in a cluster with a pharyngealized or back consonant become pharyngeal aswell: /psˁì/ > /pˁsˁì/, /ħɡʷà/ > /ħɡʷˁà/.

epinthetic vowel insertion: a vowel is inserted between all initial clusters. its quality depends on the surounding consonants. if one of them is palatal its /i/, if one of them is labialized velar, its /u/. if its both, it depends on the initial cons. else its /a/: /ctú/ > /citú/, /skʷò/ > /sukʷà/, /wɲù/ > /wuɲù/, /tkú/ > /takú/. idk what tone the new syllable gets I haven't thought about that.

pharyngeal lowering: vowels are lowered as follows after pharyngealized and back consonants: /i/ > /e/, /u/ > /o/, /æ, ɔ/ > /ɑ/. now we have 7 phonetic vowels - /i, u, e, o, ɛ, ɔ, ɑ/ yayyy yippee I love big vowel systemsss!! /tˁicˁá/ > /tˁecˁɑ́/ etc.

/ji/ /wu/ > /i/ /u/: because I don't like those sequances. I also think /wra/ >> /urà/, /jki/ >> /igì/ is pretty cool.

Here the current inventory after these changes:

and a few notes:

phonemic destinction between H and L tones

kept the lowered vowels allophones. You could just make pharyngealization go away and phonemicize the vowels but I like this gigantic inventory better lol

Potential /q ħ ʕ/ > /ʔ ∅ ∅/, to make the vowels phonemic. maybe /q/ > /k/. or even /q/ > ∕∅/ aswell?? it'll be a bold decision to make

syllable structure - #CVCCVT#. Initial clusters are now forbidden, but everything else is the same. I think V{j, w, ɰ, ħ, ʔ}C can lead to vowel length or more qualities or something, the sequance has potential.

So yeah this is all the ideas I have in my head rn, I hope it was an interesting read lol. I also recommend you go and watch the streams yourself, the vibe is very nice and help the creative juices flow, like I'm really happy with what I came up with here based on their protolang. it was like a fun colab challenge thing :) here's a link to the channel:

#letshaveabouba#conlang#conlanging#constructed language#conlangs#historical linguistics#phonology#sound change#paizau

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

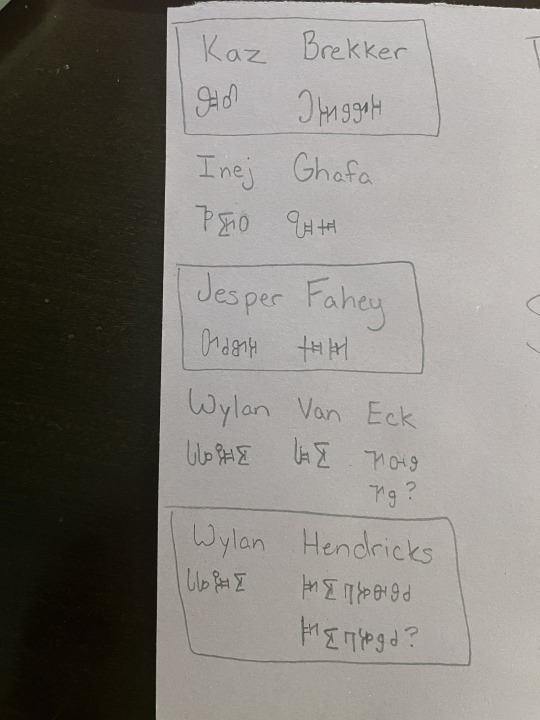

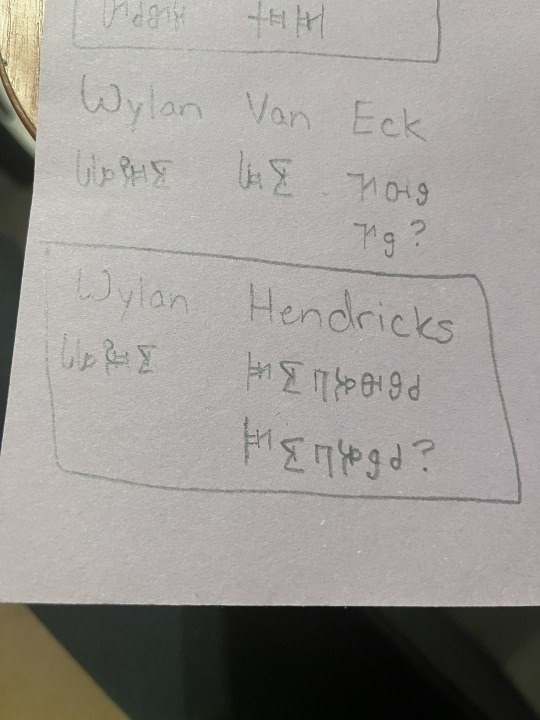

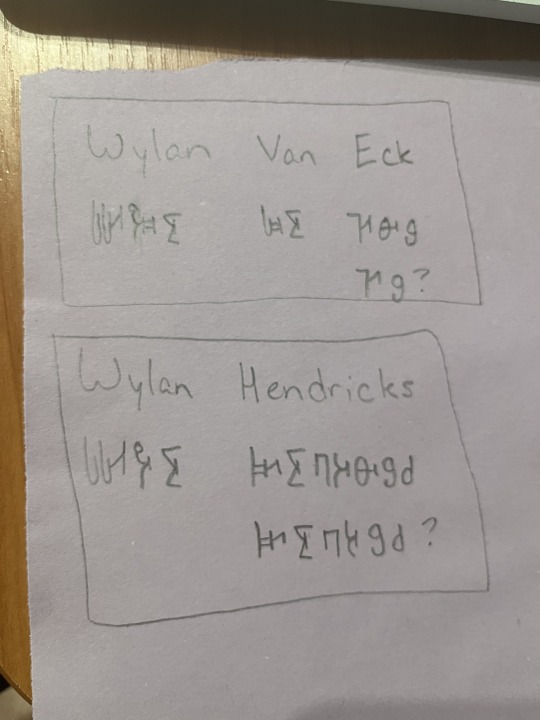

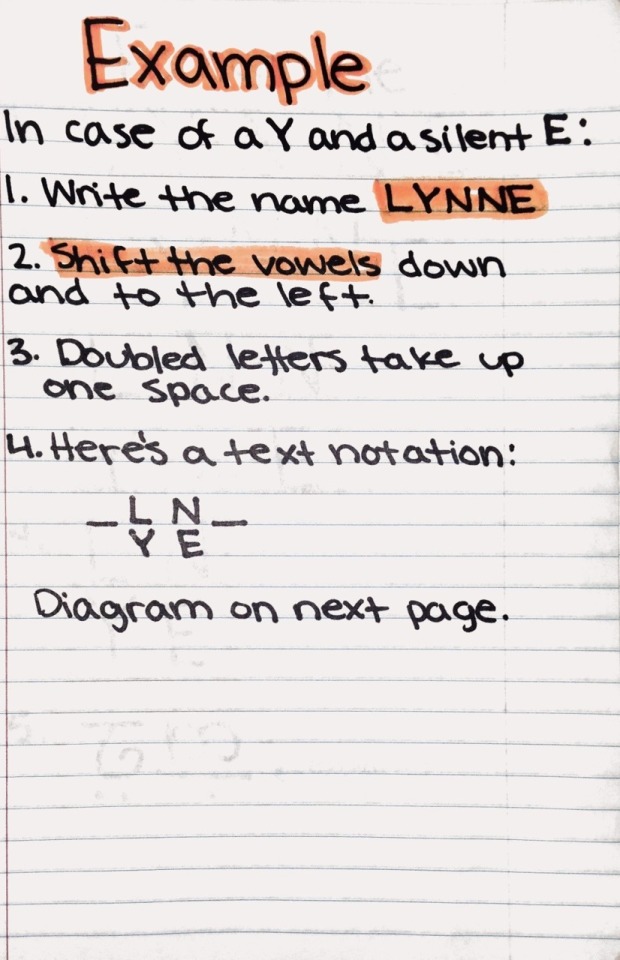

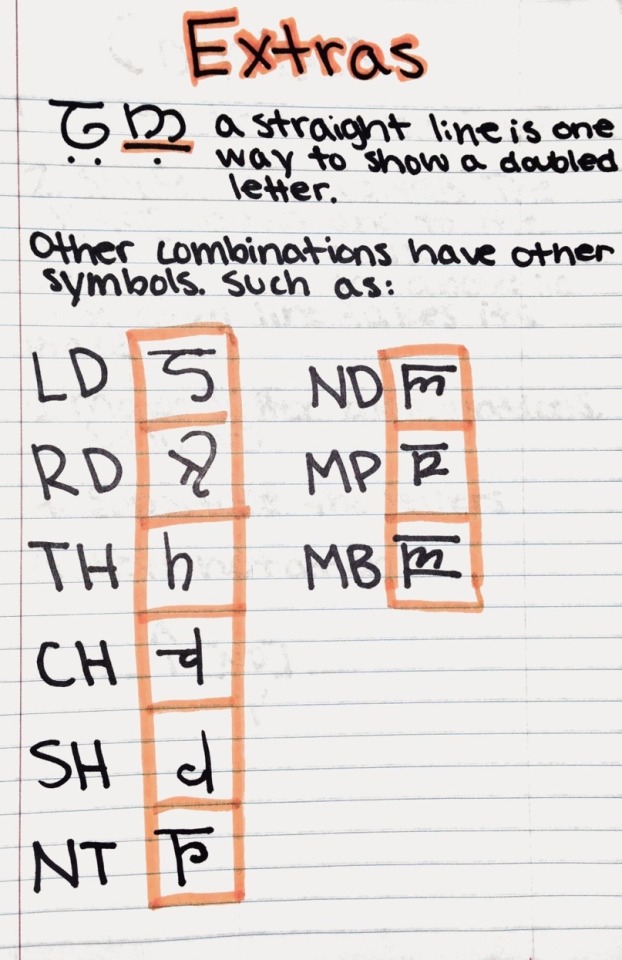

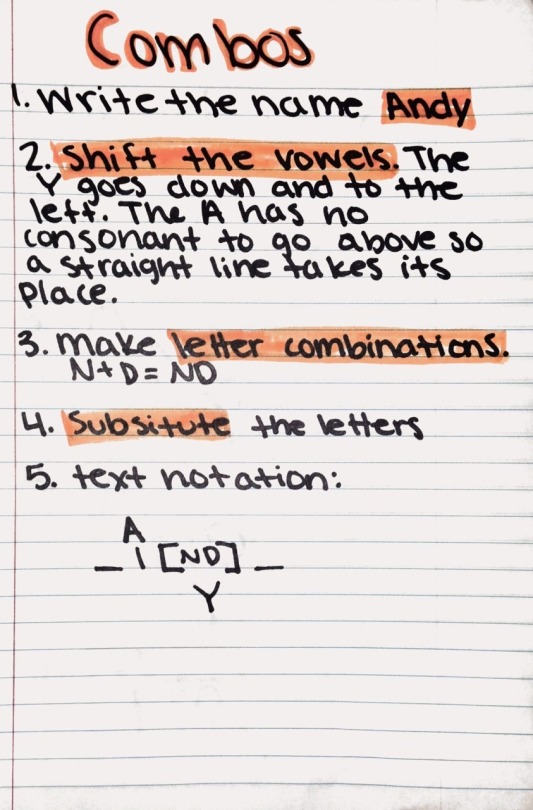

Crow Names Written in Kerch

Here are all of the Crow's names written in a Kerch alphabet. Just for fun. (And the vowel discrepancy and subsequent meltdown I had trying to write Wylan's names.)

So some things of note while creating this...

I am not an artist and drawing fictional letters is hard.

Your eye/my lighting and camera are not bad, the paper is a soft purple color left over from Valentine's Day.

More importantly:

When in doubt about spelling, I stuck to the English direct letter translation for the spelling.

For example: Inej's last name Ghafa, starts with a G so I wasn't sure whether to use the regular G or the GH character, which in words like laugh, does not use a hard G and sounds more like an F. I used the GH.

While the Kerch alphabet uses a J/Y (ja/ya) the Y at the end of Jesper's last name is written as a vowel, EE.

I actually didn't see the second chart that went into more detail about the vowels connecting to the consonants until after I wrote the names. Therefore, I didn't see the difference between the soft A (example: apple) and hard A (example: can). Technically, that means soft A character in Kaz, Nina, and Matthias' should be longer.

Aaaaand now I realize I messed up Nina's name too. Instead of a soft I, the EE vowel should have been used.

Unpictured, I also wrote out Six of Crows. There is no letter X in Kerch, unless I read the charts wrong. So in Kerch there is only the Si-- of Crows. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Wylan (his names deserves their own list of bullet points) and Matthias:

There is no hard I (as in ice) sound in Kerch, according to the the two character/letter charts I saw (linked above). HAVE WE BEEN PRONOUNCING WYLAN'S NAME WRONG THIS WHOLE TIME?!

Seriously, did I not read the charts correctly?

So in the first photo (left) I wrote his Wylan's name using the soft I just in case the vowel, like English could be used as hard or soft depending on the word. But, given that the other vowels in Kerch, like hard A, E, and O are written differently than soft A, E, and O, I don't think this is likely.

The spelling with the soft I (example: igloo) would pronounce his name as Will-lan

I also wrote Wylan's name using the hard E (which makes his name pronounced Wee-lan) in the 2nd photo (right). Personally, I'm inclined to believe it would be written this way, but there's literally no precedent, the points are made up and the rules don't matter!

The lack of hard I vowel would effect Matthias too, but I didn't realize that until after his name was written. (Matt-- i-as or Matt-ee-as: he probably hates Kerch as a language for this reason, let's be real)

Mildly related, but I feel Wylan and Matthias's pain. I moved across the world and now live within a language and alphabet that does not recognize a letter in my name. The consonant just doesn't exist. So the sound and letter use similar sounding substitutes.

The English spelling of Eck uses the letters C and K, but I wasn't sure if Kerch would combine the letters into one sound. Therefore I wrote both for funsies. Not sure which I aesthetically prefer.

The same C and K issue came up writing Hendricks too. So I wrote an example of of the English directly translated spelling and the combined K sound too just to see what they would look like.

Thanks for letting me nerd out about the Kerch language used in Shadow and Bone. It was super fun!

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

so anyway I really did start compiling a kinyarwanda/english dictionary/grammar guide out of all the random resources i've been hoarding on my phone (it doesn't have to be great, it just has to be better than searching multiple different files every time I'm looking for some obscure vocab or grammar detail) and one of these resources is some PDF uploaded to the internet archive and it's... not great. from the writing and contents it's clearly

old (my guess is mid-1900s. I don't remember colonial and post-colonial Rwandan history specifically enough to guess well here, but based on some of the typos, it was done on a typewriter and then scanned with OCR)

intended for missionaries (some examples of actual sentences in the "translate this" exercises include "I praise God because He saved me and He gave me peace and joy" and, I shit u not, "The blind man cannot see the Word of God, but he can hear and he can know the love of Jesus." it's. well for one thing this is basically useless vocabulary for me, and also it's cringe af)

written by someone who was not a linguist (at one point instead of just saying "if T is preceded by an unvoiced consonant, it turns into D" they give you a list of every unvoiced consonant and then recommend that you invent a mnemonic phrase to memorise the list?! why?)

written by someone who was shit with pronunciation (legit so many places where they're like "there's no way to describe how this sounds, you just have to ask someone to make the sound for you" my good bitch the phoneme might not be in english but I could describe it just fine. skill issue.)

but the thing that's really killing me about all this is that every time they try to explain tonal vowels or phonemes that aren't in english, they tell you to "ask an African to say it for you."

an. an what now? an African? babe there are approximately 1.5 billion people in Africa. Africa accounts for about 20% of the land on earth, it's the second-biggest continent, and it has an estimated two thousand living languages spoken throughout the continent.

and kinyarwanda? it has maybe 15-25 million native speakers, depending on which source I trust. it's spoken (almost*) exclusively in rwanda, which is the 9th smallest country in Africa--and that roundup includes islands off the coast of the continent. It has the second densest population in Africa but it still only has like 13 million people in it. and it's a very unique language. its closest relatives do not have the same phonemes that kinyarwanda has, and its closest relatives are also spoken by relatively few people. I don't know enough about kirundi to say much but I do know that it doesn't have the same vowel tones in all instances and it doesn't have some of the same consonant clusters. and the more widely spoken related languages that you're more likely to stumble on someone who knows how to speak? they're even worse for a reference; ask someone who speaks kiswahili to pronounce kinyarwanda for you and they will not pronounce the difference between, say, umuceri (rice) and umucyeri (berry), or the tonal difference between words like umusambi (floor mat) and umusambi (crested crane).

so, like. it's just absolutely sending me, this random white lady who was obviously a colonialist missionary, bothering to make a whole language guide to teach me how to proselytise in kinyarwanda, but along the way she's like "just ask an african--any african--how to say this" lady less than 1% of them are going to know this language but go off i guess

*almost because there's the diaspora of rwandan expats and immigrants in other countries plus the banyamulenge which is a whole aspect of it that has so much fraught history on all sides that I won't even try to say something intelligent about it, it's totally not my place/something i'm educated enough about, but to my knowledge most of them speak dialects that are more or less dissimilar to kinyarwanda; kinyamulenge and kinyabwisha are not the same as kinyarwanda. take it from my munyamulenge coworker who could never pronounce the difference between c and cy

#i meant to write a snappy salty thing but i kind of just got going#like. i am scavenging this because it's one of the few things I can find that includes verb tenses charted out#and past tense suffixes are a bitch#but it's also like. i do not trust it. anything i don't personally know already goes in a file to be fact checked#legit this thing tried to tell me that 'komera' is a phrase you use to say 'excuse me' if you cause harm or witness harm#like if you see someone have an accident I guess?#newsflash that is NOT what it's used for we have words for that we have mbabarira and ihangane i just like#look if any rwandan is on here and wants to correct me please do but i cannot imagine any scenario in which komera means excuse me#imagine you knock someone over and instead of saying any variety of sorry or excuse me or oh yikes i hope you're okay you say 'tough it out#like i know 'tough it out' is not a literal translation of komera but it's contextually a good translation in certain circumstances#not all obv but whatever#anyway this is. i wish anyone in my household also spoke this language bc i'm dying over how absurd this stupid reference is#kinyarwanda#languages#we'll see how long before I realise that there's a reason it took samuel johnson that long to write a dictionary#granted he didn't have ctrl+c/ctrl+v on his side sooooo i have that#tw colonisers#i guess idk if those phrases from the book are like triggering to anyone but they put a sour taste in my mouth at least so

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

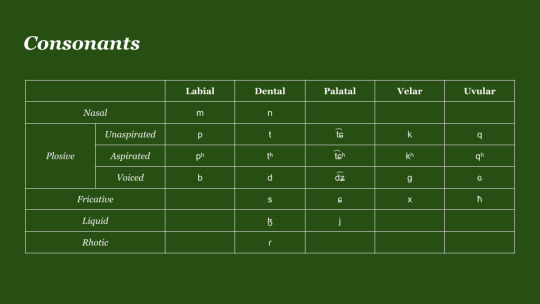

Movelang #001 - Phonology and Sound System

Nophhurra, and hello again everyone! It's time for another post showing off my experimental conlang, Movelang! This time around, I'll be going over Movelang's sound system: the consonants and vowels used, along with a currently loosely-defined syllable structure, as well as allophony!

Admittedly, the Phonology has been one of the aspects of Movelang which has been altered several times over, and has gone through several iterations before reaching the point at which it exists in the present. Since the emphasis for this conlang was moreso on grammar than on the phonoaesthetic, I had largely loosely defined it at the start, with only a vague idea of what Movelang would sound like. At the start, I took a lot of inspiration from the Coptic Language, as well as several African and Caucasian Languages. Later on as I began being more deterministic about the phonetic inventory of the language, it did change from this original vision in several ways, but I ended up ultimately with something I really like!

(My charts tend to prioritize neatness over exactness, so if there's a sound somewhere that doesn't exactly describe it completely correctly, please don't fight me 😭)

Phonemically, the consonant inventory consists of 2 nasals, 15 plosives, 4 fricatives, 2 liquids, and 1 tap. The plosives are split three ways by mode of articulation, where 5 stops are unaspirated: /p t t͡ɕ k q/, 5 stops are aspirated: /pʰ tʰ t͡ɕʰ kʰ qʰ/, and 5 are voiced: /b d d͡ʑ g ɢ/. Each mode of articulations contains a labial, dento-alveolar, palatal, velar, and uvular stop respectively. This was a choice inspired by both Ancient Greek, as well as the Coptic and Caucasian influence I mentioned earlier, and in an earlier version of the phonology, the palatal affricates were instead alveolar affricates: /t͡s t͡sʰ d͡z/. Accompanying the stops are 4 fricatives that roughly match 4/5 of the same manners of articulation: /s ɕ x ħ/. These were selected mainly for that reason, that they lie in the same POA as their stop counterparts, but I decided to throw in an oddball for the fricative furthest towards the back of the mouth. Originally, this was /h/ phonemically, but I was intrigued by Maltese's presence of /ħ/ as the sole voiceless fricative closest to the back of the mouth, so I decided to do this for Movelang, and I do love how it sounds! I personally think /x/ and /ħ/ pair nicely with each other! The Approximants and Nasals then weren't that hard to reckon, I simply filled in the gaps in the chart respectively. When I got to my /l/ sound though, I decided to make this a little bit different as well, and follow the lead of Mongolian, and make it /ɮ/ instead. I also made the decision to omit /w/ or any similar sound, since I have a habit of using this sound a lot whenever I make new sound systems, as a bit of a monkey-wrench to try and make myself work with.

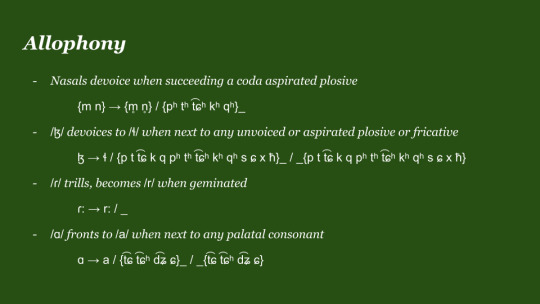

For Allophony, most of this deals with the pronunciation of consonants. There are 3 major rules that come into effect when pronouncing consonants in particular places within a word. First, the nasals, /m n/, devoice to /m̥ n̥/ whenever they are preceded by a syllable that has an aspirated plosive in the coda, any of /pʰ tʰ t͡ɕʰ kʰ qʰ/. Secondly, /ɮ/ may devoice to /ɬ/ when next to any voiceless sound: a voiceless plosive or fricative. Finally, the alveolar tap /ɾ/ becomes trilled /r/ when it is geminated. These rules as you'll notice mostly depend on a sound's locale within a syllable, which I'll explain in greater detail when discussing syllable structure...

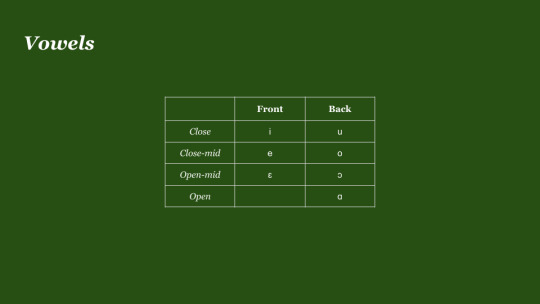

As for the vowels, these are quite simple. Movelang consists of seven phonemic vowels, which compliment the front and the back of the mouth. Movelang contains no phonemic length, tone, nasality, or anything else that would affect vowel quality in this way, at least phonemically, and only has these 7 plain oral vowels. There are 3 front vowels: /ɛ e i/, all of which are unrounded, and 4 back vowels: /ɑ ɔ o u/, all of which are rounded, except for the open back vowel.

In terms of vowel allophony, nothing really major happens to vowels. The only major rule which takes place with vowels, is that /ɑ/ goes to /a/ when near a palatal sound.

Additionally, the syllable shape in Movelang is pretty straightforward, it's pretty much CVC, but with a few additional caveats. The main difference, is that /j/ cannot be a coda consonant, which is reflected by the use of D for the coda consonant in my syllable shape notation, and additionally, only 6 consonants can end a word: /m t k q s r/, which is reflected by the use of K for a word-final coda consonant.

In addition to these tactical features, hiatus is permitted in Movelang, meaning that the onset consonant in syllables is optional even word-internally, and when this happens, the parallel vowels flow together smoothly, rather than having some epenthetic consonant placed between them, like a glottal stop. Gemination also happens quite frequently in Movelang, especially in compounds, and it is under these circumstances when /j/ technically can appear in the coda of a syllable, but only as a part of a geminate /j:/.

=-=-=-=

Alright! Well, that's pretty much it for phonology, at this point I'm going to try and stick to this phonology and not impulsively change it again, but knowing me, I can't make any promises XD. I hope you all enjoyed this look at the sound system! I look forward to posting some lexical samples in the next post, with these sounds intact, where I'll be showing you Movelang's class system in action! More on that later of course... Until then, I look forward to it, and I hope you all enjoyed this post! If you all have any questions, feel free to leave me a comment, or an ask!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

@kuroyrii : Quietly places flowers in his hair, she quickly turns to conceal her laughter only to snicker, "The colors go well with your complexion"

In the miscellany of woodland monoculture, she found him once again in the embrace of solitude listening to the sound of the water falling and the sighing of the wind in trees, malformation of mossy stairs carved to the mountainside reminding of an old stronghold long forgotten. His targets less inclined to drive to natural places for enjoyment, now laying lifelessly on the pile not far than a halfcropped kilometer. There will hardly be an ounce of anything but bones and ashes consumed soon either by flames or rot. Monkeys still refuse to put envy of his people behind them, they may still begrudge Sorcerers in their relics and things of beauty; he remembered such fact with each wipe of crimson from his face.

Blood was a peculiar thing that made even most cultured and neat man look like a wild beast in stillness, it could bore cute pink blush or deep brown spots. His sense for restoration dark yet mighty, carrying visual trademarks like insignia of battle on sword. Eyes like pits of smoldering opiates after ferocity of fresh kill.

A kindred spirit dances among trees, her every cadence a bravado breaking etiquette in moonlit gait, stalwart and dependable from both sundry and mirthful times of their storied history, masterful in the art of hunting and stealth, stiff-necked and suspicious only by wit of her tongue, the black lily that comes seeping with fanged smile more liberated than ever before, intruding reverie of his seclusion with ignorance to the carnage behind. The God Hand must have followed the track from sudden outburst of cursed energy evoked by his special grade. She would not ask what had transpired there, instead, it was her hands that spoke louder secrets in her stead, and he almost understood their unhinged language where he recalled distinct soothing. Captivity may prove too great a strain for bunny, so her crimson rather concealed on him colors that came to life and blossomed with his dark excellence when the odds were stacked against them. Something entangled among straight carbon strands. A brisk blink of fluttering lashes sorting inventory in perceptional warehouse of thinking, evoking perplexion, discarding creeping mildew, and awakening consonance from grim tidings. What is this? There's something on his head. Hand wandered up to test out his new enlightened image, caressing something soft and what's next in line for commendation when he realized what kind of structure formed under his fingertips, touch becomes light as a caterpillar's footsteps, drinking in the aromas of velvets producing scent from each little twist. Those were petals from vivid flowers, from what still left of seasonly green; jewel gift of flora that loomed on him like a black crown. Heartbeat skipped up with increasing pulse into his very throat. Sayuri might be the first step in some scheme crammed into small rooms. He breathed out in realization, '' Today I am all soil and ruin and yet you still can't help yourself but to be personally accountable for my beautification? Thought you'd have more urgent errands to undertake like entertaining snoozy patrons. If you ever decide to repeat such practioning in public be wary; it could make some women jealous. '' From string of defense, chuckle preceded deficit in melting venom. Thank you. Rivulets and bouncing waterdrops provided natural a reflection pool for him to lean in closer and check his new decoration. An apparition emerges from behind large oak; manifesting several meters away from them; offering a lined humanoid grin covered by sleeve of vermilion kimono.

'Well?' - a grin the one she could not see while he seemed so distracted and enchanted by blossoms in his strands. Or he purposely pretended to be distracted. 'You want her, don't you? Try and get her.~'

#kuroyrii#Muse: Geto#!Sayuri#反応‚ㅤ╱ 𝐒𝐔𝐆𝐔𝐑𝐔 𝐆𝐄𝐓𝐎 reacted.#{ Scoots over remembering practicular mention of certain special grade -- so HE HE HE uwu . }#{ He's just going to grab himself popcorn if this will errupt in a game of chase. }#{ The contrast in situations when Sayuri receives flowers from him vs when Geto from her. }#{ -BREATHES-THEY ARE SO COMPLICATING!! }

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conlang Year - Phonology

Important update before I get into the phonology, I have decided on a name for this language. I am calling it Awloya and the speakers are called the Awlo.

Awloya’s consonants are:

/m n ɲ ŋ/ m n nh ng

/p b t d c ɟ k ɡ/ p b t d c j k g

/s z/ s z

/w l j/ w l y

The only notable feature of this consonant inventory is the palatal series. I was considering including prenasalized stops, but after playing around with them I found they didnt fit the aesthetic Im going for. I plan bringing in more fricatives as I evolve the language.

/l/ becomes /ʎ/ before we palatals /ɫ/ before velars.

The sequence /ng/ is written as <n’g> to distinguish it from /ŋ/, which is written as <ng>

Awloya’s vowels are:

/i e ä o u/ i e a o u

Fairly standard 5 vowel system

Phonotactics

Awloya has a maximal syllable structure of (C)V(S). C being consonants, V being vowels, and S being sonorants (m, n, nh, ng, w, l, and y).

Stress falls on final syllable if it is closed, otherwise the penultimate syllable is stressed.

Phonotactic restrictions:

No nasal except /n/ can precede a fricative

/n/ cannot precede /ɲ/ or /ŋ/

/ɲ/ cannot precede another nasal or /j/

Vowel hiatus is not allowed. In the case that two vowels are next to each other, an epenthetic approximant is inserted between the two depending on the second vowel. /j/ before /i/ or /e/, /w/ before /u/ or /o/, and /l/ before /.

And that’s it for this post! See yall soon!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

it's not not legit... it's an ad hoc way of using Tengwar (the Elvish alphabet) to write English

the vowels go on top of the conconants that precede them, as they do in Quenya or High Elvish (they go on following consonant in Sindarin or Grey Elvish, which btw, was the language spoken in the films) but the consonantal values don't line up perfectly with the Quenya

for example, the letter given above for C was indeed transliterated by Tolkien with <c> and makes a [k] sound. the letter above for K should be the same, but instead gives the letter for <qu> [kʷ], and the letter given for QU is really <nqu> [ŋkʷ]. similarly the letter for G above is really <ngw> [ŋgʷ].

the English J-sound doesn't exist in Elvish ; the letter given for J above is really the <g> [g] (well, the plain voiced stops [b d g] are technically the Sindarin pronunciations, not Quenya, but close enough)

the so-called "red-R" and "car-R" also don't represent different sounds, they're simply different versions of the <r> depending on whether there's a vowel following/above them or not.

now to be clear, this isn't meant as a criticism per se. just like there were different modes of Tengwar for writing Quenya and Sindarin, it stands to reason that there can be a different mode for writing English. Tolkien himself never settled on one, official, consistent way to transcribe English in Tengwar. so the above method is fine if that's how you want to do it... Just be aware that it's not how the alphabet is used to write either version of Elvish, and it's also not the only way to use it for English. other fan systems will be different

YOU WANNA LEARN ELVISH?! HERE YA GO!

#I'm adding this to a decade old post with over 400k notes#I don't expect this to reach anyone but I couldn't let it go... and I wasn't being disingenuous this method does work#I just don't think it's a good or intuitive way to write English in Tengwar#and there are more issues like that letter for H#tengwar#writing system#elvish

481K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ro3 Yanese conlang rambling

So... A while ago, I worked on one of my fanlangs (a constructed language taking place in an already existing setting) for my Arknights Rule of Three AU. The conlang was to be spoken by the people of Yan and, since I always strived to make my conlangs weird, I wanted to do something weird with the grammar of this language.

I got a pretty good phonology where plosives, fricatives, and other consonants were preceded, followed, and surrounded by puffs of air in addition to plain consonants without any puffs of air. These puffs were orthographically marked by acutes, graves, carons, and circumflexes to indicate whether before, after, or on both sides of that consonant the puffs of air occur. I even came up with some orthographic rules for the diacritics to occur in certain ways, especially when the consonants formed clusters.

Then I came up with a pretty robust derivation system to help with the forming of new words. Some of my favorites are the -shan from the Hungry City Chronicle's Zan Shan sacred mountain, which I borrowed into Yanese as Zanshan lit. "sacred mountain". Then there was the suffix -kleng which derives tools of nouns and verbs which evolved from an onomatopoeia of clang-clang-clang of hammering on metal.

Unfortunately, those were the easy parts. I decided that the Ro3!Yan would be big on protocol and politeness. Thus, I conceptualized a rule that morphemes in Yanese would be isolating in the polite register and agglutinating in the more informal ones. The degree of synthesis between the two could even be an indicator on the spectrum of politeness as well.

The problem I have with this is what would separate affixes from syntactic particles? I keep hearing that particles are syntactic morphemes that are free and depend on word order while affixes are bound to a free morpheme. What separates a fixed word order of function words from a template of affixes? Should I differentiate them by having the grammatical particles be more syntactically free than the bound affixes? Or should I embrace the ambiguity for the sake of depth and "naturalism"?

Anyways, that's all I got to say. If you made it this far, I appreciate you taking your time to do so and would even more so like to hear your thoughts on this.

Take care and till next time... ;)

#conlanging#language construction#language creation#glossopoeia#linguistics#help request#grammar#terminology#arknights#arknights fanfiction#arknights au

0 notes

Text

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part III: Poem 66.

〽 Taikai wo ashirau-toki ha ō-yubi wo kata ni kakeru zo narai nari-keru

[大海を遇う時は大指を 肩に掛けるぞ習いなりける].

“When handling a taikai, [you] should practice resting the thumb [of your left hand] on the shoulder.”

This poem refers to the handling of the taikai (along with its sub-category naikai [内海]¹).

The Chinese jars of this type were probably used as containers for medicinal herbs (much as were the kansaku-katatsuki that had come from Korea).

The Korean pieces (which were always the more common variety of taikai in Japan) were usually produced as containers for salt or crushed red-pepper, and were intended to be placed on the dining table for use during the meal².

The way this poem teaches that these taikai should be held seems to have come from the way they were held when used for their original purposes.

Katatsuki are held wholly from the side. The ko-tsubo are held with the little finger of the left hand touching the bottom. And taikai are more fully cupped in the hand, with the thumb of the left hand resting on the shoulder in front of the mouth. Since taikai were often quite large³, and so might be easier to drop as a result, keeping the left thumb on the shoulder of the taikai would effectively lock the chaire into the hand.

Though this matter is not addressed in poem 66, it might be good to mention that there were two different ways to approach the transfer of the matcha into the chawan when a taikai was being used. The older (and, perhaps more logical) way was that it should be scooped out (kumu [汲む]), since this is the method that the wide mouth invites. However from a certain point during the second half of the sixteenth century -- and, more openly, around the middle of the seventeenth century -- certain chajin began to argue that, in order to contrast⁴ the host’s actions with the extremely wide mouth (and to distinguish this action from the way salt or crushed pepper would be added to one’s food), the tea should be pulled over the mouth with the side of the chashaku (sukuu [掬う]), in the same way as when pulling the tea out of a narrow-mouthed ko-tsubo. While scooping has pretty much become the norm today, it is important to recognize that there are still several modern schools that adhere to the other way of doing things.

In the case of poem 66, all of the received versions agree. While some might argue that this is because its handling was ubiquitous, based on the precedent of the o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚] (where the large taikai was the traditionally preferred chaire on account of its size and ease of use when preparing multiple bowls of tea at the same time), the more likely reason was because the taikai was falling from favor as the sixteenth century progressed toward its end⁵, so there was no real occasion for divergent opinions to arise that could be passed on to the chajin of the Edo period (who were intent on fanning the flames of contention between their own school and those that were increasingly viewed as “the competition”).

_________________________

¹The first reference to the naikai* [内海] (the word can also be pronounced uchi-umi) seems to appear around the middle of the seventeenth century.

The shape is similar to the taikai, though generally smaller (rarely larger than 2-sun 5- or 6-bu in diameter), and with a narrower mouth. Since the mouth is poetically likened to the face of the ocean, the term nai-kai refers to a smaller sea or bay surrounded by land masses -- when viewed from above, this chaire gives a similar impression with its wider shoulders surrounding the narrower mouth. ___________ *In certain dialects of Japanese, native speakers recognize a certain consonance between the sounds of “t” [/t/] or “d” [/d/] (as in taikai, which can also be pronounced to sound like daikai) and “n” [/n/] (naikai). This argument is used both to lump the naikai in with the taikai, as well as segregate this sub-category from the taikai, depending on who is making the argument.

²Since this would have included the tables of the sovereign, as well as the high nobles, the quality of many taikai could be expected to be exceptional.

³The large taikai (usually measuring between 3-sun and 3-sun 2-bu in diameter) was the chaire of choice for use on the o-chanoyu-dana (the large, built-in shelf, resembling a daisu, in the 2-mat preparation area that adjoined the private shoin or sitting rooms, in the mansions of the nobility).

This kind of container was chosen for this purpose because it would hold enough tea for the entire day’s consumption, while also being easier to hold (important when doling out matcha into multiple bowls at the same time for tate-dashi service).

⁴The notion of contrasting one thing with another was an aspect of the performative style of chanoyu that first made its appearance during the 1570s (when many of the important chajin from Sakai were openly courting the favor first of Nobunaga, and, following his death, then Hideyoshi -- by proposing new, visually inspiring, and sometimes unprecedented approaches to the practice of chanoyu*), becoming increasingly widespread in the half century following Rikyū’s death (in the late spring of 1591).

The chanoyu of the Edo period (and that of the present day, as well) can generally be described as performative. ___________ *Hideyoshi’s selection of Rikyū as his chief sadō [茶頭] (tea official) and intimate counselor, whose temae tended to eschew the performative aspect in favor of simplified practicality, appears to have put the brakes on this approach among the tea community, at least so long as he remained in Hideyoshi’s favor.

⁵This is the only real reason why the shifuku for taikai have a long himo.

Originally, the shifuku for all chaire had long himo (called naga-o [長緒]), which were tied into various decorative knots (with two different knots being used for each chaire over the course of the tea gathering: a slip-knot before tea was served, and a locking-knot that was tied at the end, since the remaining tea was no longer suitable for use when serving koicha to another group of guests).

Hosokawa Sansai, for example, recorded the knots that he learned in Korea in a section of a manuscript that was archived as Sansai-kō o-chagaki [三齋公御茶書] (”Lord Sansai’s writings on tea”), entitled Koryū ketsu-hō zu [古流結法図] (”sketches of the Korean ways to tie knots” -- where Koryū is a hentai-gana approximation of the Korean Goryu [고려], meaning Korea). This series of sketches is shown above.

The change to the shorter himo is attributed to Shukō, as part of his effort to simplify the details of chanoyu (by eliminating unnecessary complicating elements, such as the different ways for tying the long himo).

The naga-o remained associated with the taikai because, after a half-century and more of disuse, these chaire were being “rediscovered” in the storehouses of the tea families, and reused during the Edo period, when antiques of all sorts were being venerated as precious (and so costly) relics of chanoyu’s early days.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator.

To contribute, please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

1 note

·

View note

Text

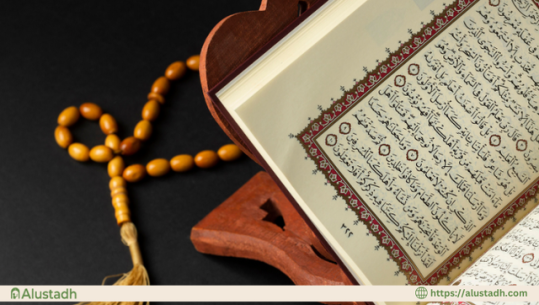

What Is Madd In Tajweed, Its Types And Common Differences?

Madd, meaning "extension" or "prolongation" in Arabic, refers to the lengthening of specific vowel sounds in the recitation of the Quran. It plays a crucial role in Tajweed, ensuring the correct pronunciation and preservation of the Quran's meaning and beauty.

Here's a detailed breakdown of Madd in Tajweed:

1. The Letters of Madd:

There are three letters associated with Madd, known as Huruf al-Madd:

Alif (ا)

Waw (و)

Ya (ي)

These letters must be silent (without a vowel sound) and preceded by a vowel sign (Fatha, Damma, or Kasra) depending on the letter:

Alif: Preceded by Fatha (e.g., غَافِرٌ - Ghafoor)

Waw: Preceded by Damma (e.g., وَالضُّحَى - Ad-Duhaa)

Ya: Preceded by Kasra (e.g., رَحِيمٌ - Raheem)

2. Types of Madd:

There are seven main types of Madd, each with specific rules and varying lengths of extension:

Madd Asli (Natural Madd): This is the inherent lengthening of the Madd letter due to its nature. It extends for two counts.

Madd Far'i (Branching Madd): This lengthening occurs when a Madd letter is followed by a hamza (ء) without a vowel sign. It extends for two counts.

Madd Wajib (Obligatory Madd): This occurs when a Madd letter sits at the end of a word and is followed by a pause (Waqf). It extends for two to six counts depending on the recitation style.

Madd Jaiz (Permissible Madd): This allows for the lengthening of a Madd letter even when it's not followed by a pause, but only in specific contexts. It extends for one to four counts.

Madd Muttasil (Connected Madd): This type of Madd occurs when a Madd letter is followed by another Madd letter within the same word. The first Madd is slightly extended for one count.

Madd al-Lin (Madd of Ease): This is a subtle lengthening applied to a Madd letter at the end of a word followed by a Sukun (no vowel sign) and then another letter with a vowel. It extends for less than one count.

Madd Aridh Li-s-Sukun (Madd due to Sukun): This lengthening occurs when a Madd letter has a Sukun and is followed by a word that begins with a consonant. It extends for one to two counts.

Intrigued to learn more about Madd and elevate your Quranic recitation? Dive deeper into our comprehensive guide on Madd in Tajweed, exclusively on Alustadh Academy. This in-depth exploration will equip you with the knowledge and practical guidance to master this essential Tajweed skill.

You can learn more and get benefits with us:

Quran memorization course

Quran tafseer course

Best online tajweed course

Advanced Arabic course

0 notes

Text

Some people have accents or speech impediments that are most notable in certain sounds.

Also, sound systems in languages, especially if they aren't related, are something you need to practice. Mandarin Chinese is nice because the pinyin system of pronunciation is reliable (unlike English), but the sounds and tonals do take some practice to get used to. It uses the ü sound a lot which English doesn't have at all (and is therefore very tricky to grasp for English speakers) and it's presence is often more implied depending on the preceding consonants.

I'm not saying it doesn't frustrate me a little when people badly mispronounce things but it's way worse if they don't even acknowledge it.

youtubers love to say “i hope i’m pronouncing that correctly” while recording themselves in a video that they upload to the internet, which they have access to

#languages#textpost#i have a pretty good aptitude for foreign languages#but i still struggle with this every once in a while

52K notes

·

View notes

Text

Spelling Reform VI: Yod

Palatalization in English happens in two main ways, which I will here call Trochaic and Long U palatalization.

Trochaic Palatalization

This form happens to a few consonants when they appear in a unstressed ultimate syllable preceded by a stressed penultimate syllable, and have a front vowel (i, y) followed by another vowel orthographically (a, o, u, sometimes e). The reason I call it Trochaic is because this only happens when the last pair of syllables in multi-syllabic words form a trochee. I know the definition seems a bit hard to understand, but some examples will hopefully clear this up.

I don't know why ⟨t⟩ represents /s/ but it does and I don't want to change an established pattern like this one.

As you can see, the trochaic palatalization for ⟨c⟩ yields a different sound than regular softening. I think this is because in this case, the ⟨ci⟩ is standing for /s/ which then itself gets palatalized to /ʃ/. The pattern for ⟨g⟩ is the exact same, but I thought I would include it for completeness.

Why does ⟨s⟩ give /ʒ/? Because in this context, ⟨s⟩ is between vowels and so represents /z/ which then gets palatalized to /ʒ/. The examples I gave are also a good example of a minimal pair in English between /dʒ/ and /ʒ/.

Trochaic palatalization of ⟨d⟩ and ⟨x⟩ is in fact so rare than when it does happen, as in the example words, the ⟨i⟩ changes to a ⟨j⟩ to really emphasize the palatalization. So yes, ⟨dj⟩ is /dʒ/ and ⟨xj⟩ is /kʃ/.

Long U Palatalization

The other main source of palatalization comes from the pseudo-diphthong /ju/, variously written as «ú, ue, eu, ew». It's not really technically a diphthong but it sure behaves like one (due to the fact that it is the simplification of a few Middle English diphthongs.) After most consonants, the C and the /j/ are just pronounced one after the other, e.g. «mút» [mute] /mjut/ or «hue» /hju/.

After some consonants, the yod (/j/) is always dropped. This includes the palatal /tʃ, dʒ, ʃ, j/ and the liquids /r, l/. For example, the yod is not there in the words «ćew, júce, ćhút, yew, threw, blue» [chew, juice, chute, yew, threw, blue] /tʃu, dʒus, ʃut, ju, θru, blu/.

For the letters ⟨t, d, s⟩ (or more precisely, the consonants /t, d, s/) however, things get a little messy. Depending on dialect and word, the yod can either remain, be dropped, or coalesce. In the first case, the two consonants are pronounced one after the other no problems. In the second, the /j/ disappears entirely, like in "sue."

And finally, in the third case, the consonant cluster palatalizes into a new sound. This can be seen in the following table. A note: the suffixes «-túr» [-ture] and «-súr» [-sure] are (nearly) always palatalized. Other than that, it varies so much between dialects and speakers that it would be of no use to specify the workings here.

I should mention that if the yod is dropped when used with one of the following, «ú» is written as «ù», e.g., «sùt» [suit]. Both are permissible after «r, l».

I should also mention briefly, as this is not the vowels section, that the quality of «ú» is more important than its length, despite the aigu.

1 note

·

View note