#curtius

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

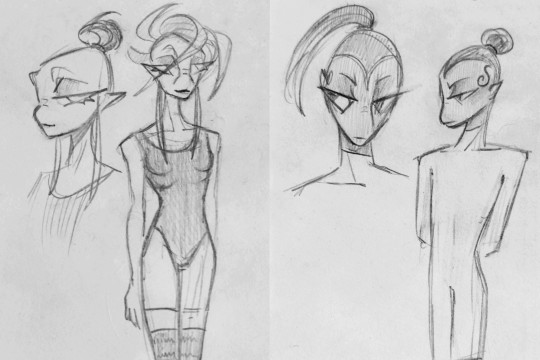

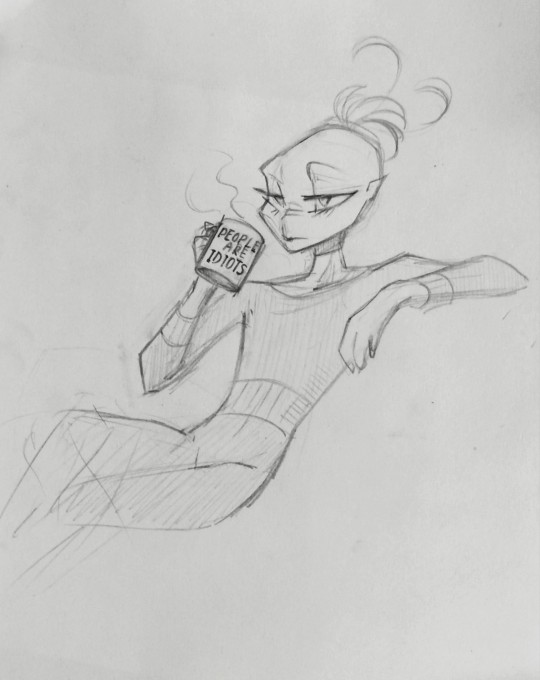

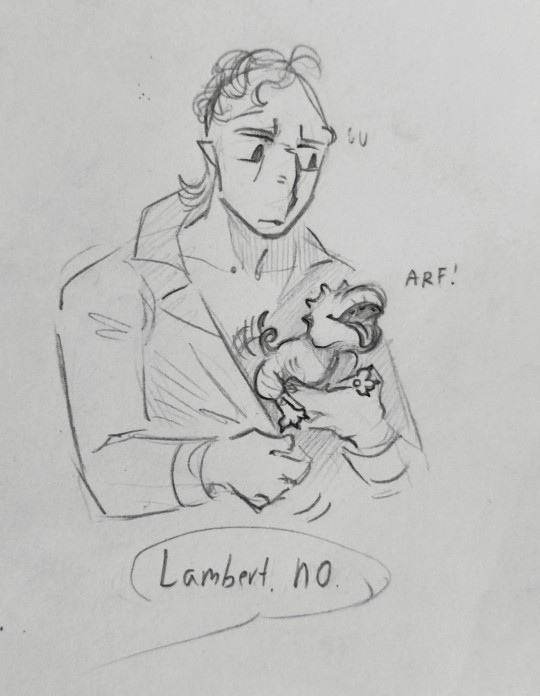

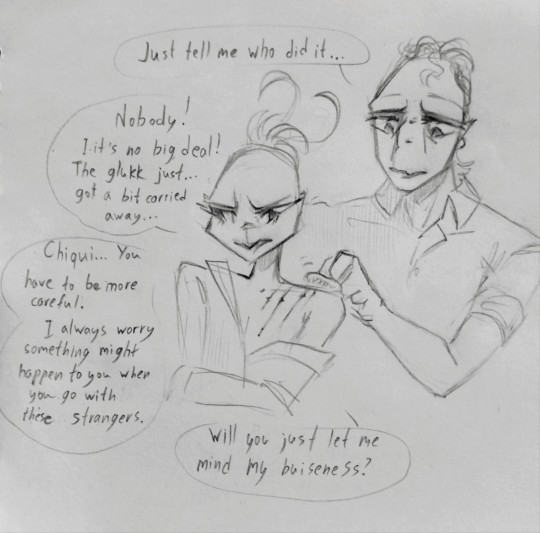

Aveth and Curtius.

Aveth is the only Queen dancer in the troupe. Queen ballerinas are rare, and just that fact makes her significantly more valuable than the other dancers. Because of that, she gets away with way more than a regular worker can ever allow themselves, and has privileges that others don't have.

Those privileges didn't make her arrogant though. Aveth is pretty down to earth and straightforward, and likes to help out others if she can. But sometimes she can be quite careless. Too careless for her own good sometimes.

Curtius is the one who's always there to keep her out of trouble. He is the exact opposite of Aveth.

Most of all he values hard work, discipline and diligence, and holds himself up to very high standards.

He's had to work especially hard to earn a place in the ballet industry, because for dancers, light and pale skin colours are the most valued, and his unusual dark complexion has created many obstacles for him. Though, he's managed to turn it into a strength that makes him a unique and special dancer.

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Following up on your answer to that person’s question about Barsine, if Herakles was Alexander’s son, why did he ignore him? Maybe I’m wrong, but I haven’t gotten the impression from what I’ve learned about Alexander that he’s indifferent to family, especially a baby that’s his.

Aaaaand this is precisely why I’m still not 100% sold that Herakles was his.

Herakles of Macedon, Alexander's "Forgotten?" Son

Although as Monica (D’Agostini) reminded me, the baby would have been only about four when ATG died, so at that age, it was quite traditional for children to remain with their mother—and he’d sent Barsine to Pergamon, the Aeolian area where her family had a great deal of power and land. Typically, very young children were left out of historical accounts without a particular reason to mention them. One would think the birth of a healthy prince would count, but we hear about Alexander’s own birth only because notice of it coincided with two other pieces of good news for Philip (and because he became so important later). We don’t hear about Arrhidaios’s birth, much less any of the girls. Even the last is mentioned only because of how she died at Olympias’s hands.

Similarly, we know about Roxane’s pregnancy and stillbirth/miscarriage from the (very late) Metz Epitome. And we know Statiera died in childbirth from a tossed off comment in Plutarch and Justin. Arrian doesn’t mention either of these. That’s caused some to dismiss them both as fabricated, but the problem is we wouldn’t expect the campaign/military-focused Arrian to talk about them. Curtius does at least talk about Statiera, but because she fits into his narrative of an (early) clement ATG, he doesn’t attribute her death to childbirth but exhaustion—in part because a pregnant Statiera would conflict with how he’s presenting Alexander at that point in his narrative, suggesting that maybe he didn’t keep his hands off another man’s wife.

Monica thinks Barsine stayed with Alexander all the way into Baktria and was probably sent to Pergamon either when she became pregnant or after the baby was born. I’d bet on the former, to get her the best medical care. Remember Barsine’s age; she was older than Alexander—possibly approaching 40. Her daughter by Memnon was old enough to be married to Nearchos at Susa—which is why, after Alexander’s death, Nearchos brought Herakles forward as a candidate for king. The daughter may have been as young as 14/15, but that still makes her mother 35+ in 324. Barsine was married to Mentor before Memnon, although perhaps not for very long. Alexander probably didn’t want her trying to have a baby at the back of nowhere at her age, regardless of how many she’d already had. Artabazos “retired” around that same time, so perhaps they traveled back west together. (I’d have to check whether he stayed at the court.)

But the histories don’t reveal any of this. It’s pieced together from the age of Herakles at his death and mention of Barsine being given to Alexander as a mistress after Issos, plus the later prominence of her family—although that could have owed to long-standing guest-friendship between Artabazos and the Macedonian court. IOW, Barsine likely got her position as mistress because of her family’s earlier connection to the Argeads, and in turn, her position as mistress led to Artabazos’s elevated treatment later.

So that’s one likely scenario. But there are a few others. Barsine may have been a cover for Alexander’s affair with Statiera. As we know, Statiera (probably) died in childbirth but the baby couldn’t have been Darius, and therefore almost had to be Alexander’s. After she died (right before Gaugamela), Alexander may have left all the women in Babylon. He certainly didn’t drag Darius’s daughters off to Baktria. If that were the case, timing-wise, Herakles couldn’t be Alexander’s.

Or it's possible Barsine was Alexander’s mistress (not just a cover) even as he also had an affair with Statiera. No expectations existed for Alexander to have only one mistress at a time. I find it unlikely that he took up with Statiera until after he’d received at least the first letter from Darius, making it clear Darius wouldn’t negotiate for his family. So he may have started with Barsine, then took up with Statiera too, but also kept Barsine. Barsine's knowledge of Persia would have been invaluable to him. As for bringing Barsine to Baktria but not Darius’s daughters, they were much younger and perhaps less tough. Certainly they were less experienced politically, compared to the older, bilingual Barsine. So, I can see reasons for bringing her and not them.

The problem is simply that, when it comes to the women traveling with Alexander’s army, we are told so VERY little, from which we are then forced to infer so much. Ergo, disagreement easily ensues over how to interpret the titbits. That’s a large part of why I was open to hearing Monica’s alternative theories. (Well, that and the fact it’s not central to anything I’ve published, so any course-correction isn’t personal—ha.)

The difficulty is just that, after she’s brought to Alexander following Issos, we hear nothing about Barsine again until her daughter is selected for Nearchos’s wife. Then not again till Alexander’s death when Nearchos champions her son (and fails). Then not again until after Arrhidaios and Alexander IV are both dead, and Polyperchon tries to put Herakles forward but is bribed/talked out of it by Kassandros, so instead he kills both the 18-year-old Herakles and Barsine.

The problem is, we wouldn’t necessarily expect to hear about Barsine and Herakles, so that silence isn’t especially significant. That’s why an argument from silence is problematic. Alexander may, in fact, have taken an interest in his son, but wanted to keep him away from court until he was older, especially if he wasn’t legitimate. Alexander was all-too-accustomed to the politics of polygamy and recognized that bringing him to Babylon could make him a target, especially if he wasn’t old enough yet to travel with his father (under his father’s eye and protection). Alexander NOT taking a big interest in him would, ironically, act as protection.

Also, we don’t actually know where Barsine and Herakles were when Alexander died, except apparently not in Babylon. Alexander might have seen the boy earlier, however, once he was back in the west. Barsine could very well have met him to Ekbatana, as the Persian Royal Road goes from Sardis north until east of the Tigris, when it swings south towards Susa. But Persia had a LOT of roads, not just that one, and a road forked off the main trek to the capital of Ekbatana in Media. Easy travel. ATG was to have held a major festival there with athletic contests and all sorts of things, but everything got overshadowed by Hephaistion’s death.

Of more import is why he was passed over at Alexander’s death. I actually find this to be the one REAL sticking point in arguments about his parentage, but it cuts both ways.

Given that nobody knew if Roxane’s baby would be male, and the mental infirmity of Arrhidaios (enough that Perdikkas was appointed regent, as for a child, of a man in his mid-30s!), not choosing Herakles presents a problem. Any Argead male could inherit. Some have pointed out the resistance to Roxane’s son to explain resistance to Herakles too; not only was he part Persian, but the son of a mere mistress, not wife. I find that a weak argument. Barsine was half Greek (her mother was Greek, sister of Mentor and Memnon of Rhodes), making Herakles less than half Persian. If anything, the son of the thoroughly Hellenized Barsine would have been preferable to the unborn child of “barbarian” Roxane, legitimate or not.

If there were doubts about him AS Alexander’s son, however, that could explain why Nearchos’s suggestion was ignored. Except if he’d expected that to be a problem, it seems unlikely Nearchos would've put him forward. Perhaps years later, when Polyperchon tried, a cuckoo could have been slipped in, but in 323, that would've been harder. Also, the fact Kassandros paid off Polyperchon to kill Herakles, the last surviving Argead—didn’t just claim he wasn’t Alexander’s son—suggests Kassandros believed he was Alexander’s son.

Yet it's still a puzzle to me why Herakles was passed over, a healthy male child, in favor of the mentally incapable brother and unborn baby. Perhaps if we had more of Diodoros’s book 18, as well as Arrian’s account of what happened immediately after (the book exists in only in a few tantalizing fragments)—or for that matter Nearchos’s own account!—we’d get a better idea of what transpired in Babylon that July.

#asks#Barsine#Herakles of Macedon#Alexander the Great#Artabazos#Nearchos#Nearchus#Arrian#Curtius#Plutarch#Justin#Alexander's children#sons of Alexander the Great

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

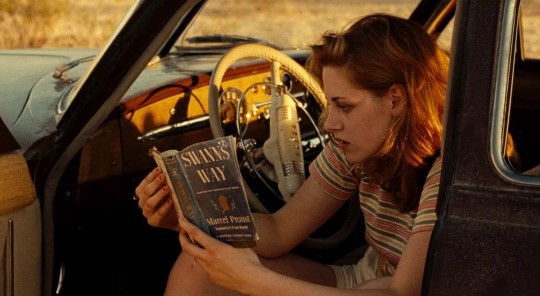

'this term of great art, which seems to me to be necessary to qualify Proust.' (Robert-Ernst Curtius)

Marcel Proust: "I became aware of the tangible reality of Wagner's work again when I revisited these insistent and fleeting themes that visit an act, only to depart and return, sometimes distant, drowsy, almost detached, yet at other times, while remaining vague, so urgent and so close, so internal, so organic, so visceral that it seems less a reprise of a motif than of a neuralgia." (French text)

Photo: Kristen Stewart reads Marcel Proust

Robert-Ernst Curtius: "What did we experience at our first encounter with Proust's books? The sudden surprise of touching something unknown; of feeling a new substance whose structure eluded us. We felt disoriented and compelled to engage in a mode of expression for which none of the habits of our mind were prepared. Strange encounter. Initially bewildered, then intrigued, and finally captivated, we soon found ourselves drawn in by a mysterious allure. Barely having entered this unexplored territory, we were charmed, then conquered, and something of our most intimate life was changed. Like Ulysses' companions in the land of the Lotus-eaters, we had tasted a fruit that made us forget the past of our mind and removed the desire to return to our former nourishment. Intoxicated by our discovery, we couldn't distinguish whether it was a new form of art or a new plan of life that was presenting itself to us. But upon regaining our composure, retracing the path through analysis, we recognized this very impossibility of distinguishing between aesthetic emotion and the upheaval of our entire being as the infallible sign of the revelation of a great work of art.

I would like to give full significance to this term of great art, which seems to me to be necessary to qualify Proust. Certainly, there is no lack of fine, engaging, and powerful works in contemporary production. But do almost all of them not seem to have their starting point in transmitted literary forms—either continuing them or taking them in the opposite direction, which is just another way of depending on them? But alongside this production grafted onto earlier literature, the steady growth of which would be sufficient to attest to its somewhat secondary quality, there are few works that arise as if outside the literary concerns of the time; they do not seem called upon by the "moment" or motivated by an artistic movement; they differ profoundly from usual literature but without any sense of a desire to differ. These works, which do not depend so much on literature as literature will not depend on them, born from the original effort of a powerful mind focused on life itself, are the ones I was thinking of when using the term great art.

In Marcel Proust's work, the creative power presents a spectacle all the more admirable in that it has been exercised upon the richest literary and intellectual culture, which, in a less powerful mind, could have posed an obstacle to such a fresh realization by either paralyzing it or leading it astray into delightful yet bookish alexandrines. Proust's art, instead of being hindered by the treasures of his literary memory, manages instead to highlight them or, furthermore, to render them anew to us. He knows how to blend spontaneous life with the entire inheritance of the past. In handling it, he maintains direct and immediate contact with the elusively fleeting material from which our life is woven. Proust presents himself to it with a sensitivity that seems untouched by any prior contact—otherwise, how would it succeed in capturing nuances of reality that had previously eluded us? The slightest layer of transmitted experience or habit that would have intervened between them and the receiving apparatus would have acted as a barrier, preventing them from being inscribed there. But this sensitivity is accompanied by a mind nourished by the richest and most diverse tradition—and one that lives in familiarity with Ruskin as well as Saint-Simon. It is from the encounter of two things that seem to exclude each other— the most freshly spontaneous sensitivity and the most culturally laden intelligence— (but which, in him, by penetrating each other, mutually lend support) that Proust's art derives its new and moving beauty.

In a more general sense, the profound originality of the great artist who has just passed away is revealed in this, that attitudes of the mind that we are accustomed to consider as distinct penetrate each other in him to the point of forming a homogeneous whole. Intelligence does not merely overlay emotion but becomes one with it. Feeling and analysis do not appear as two opposed terms between which a relationship can be established. Art will be life, and vice versa. Lastly, thought in Proust never gives the impression of being a foreign and external element. One can consider separately in his work psychology, poetry, science, observation, emotion. But it will always involve an artificial isolation that distorts the truth. All these elements that analysis attempts to separate form in him not a mixture, not even a fusion, but the blossoming of an identical, primordial, and indivisible experience. By pushing the analysis further, I believe one would be led to understand this profound unity that is perceived beneath the delightful complexity of his work as the externalization of the creative impulse from which it originates. His art arises from this unified and total vision that constitutes the life of the mind at its principle and in its fullness. In Proust, I can never dissociate beauty from truth. The profound and purifying emotion suggested by the evocation of the mysteries of life; the intimate contentment caused by highlighting the infinitely small aspects of our existence; the happiness felt in the revelation of its unsuspected richness; the introduction to a deeper inner life—these are the gifts we receive from Proust's art, but bathed in the same atmosphere and melted into a single harmony.

It is a new era in the history of the great French novel that begins with Proust. Solely to better delineate his originality and without aiming at a judgment at this moment, which is one of homage to a great deceased, one can nevertheless say that he surpasses Flaubert in intelligence as he surpasses Balzac in literary qualities and Stendhal in the understanding of life and beauty. Therefore, he must be regarded as the founder of a realm that he shares with no other.

To our intelligence as well as to our admiration, he imposes himself as a master among the greatest.

He is among the three or four names in contemporary French literature that are already or will be European names. Rooted in the most authentic French soil, he nevertheless far exceeds the boundaries that some seem eager to set for the French spirit. He has expanded the domain of the human soul; he has embellished all our lives. Allied with the great classical lineage of his homeland, he has nevertheless strayed from the confines of a too timid classicism. He has given himself free rein without conforming to a pre-established aesthetic. Here again, he has shown himself to be a creator. With the freedom permitted by mastery, he has annexed to the French tradition domains hitherto left fallow.

Emerging at a time when intellectual Germany was turning away from manifestations of the French spirit to focus more exclusively on its own heritage, he made us feel once again—speaking on behalf of a few, until others may come to know and offer their testimony—that today, as in the past, there are treasures common to the nations of our divided and troubled Europe."

ROBERT-ERNST CURTIUS

Tribute to Marcel Proust, La Nouvelle Revue Française, 1923

VIDEO:

'He who this love into my heart had breathed, whose will had placed the Wälsung at my side, true only to him, thy word did I defy.'

(German: 'Der diese Liebe mir in's Herz gehaucht, dem Willen, der dem Wälsung mich gesellt, ihm innig vertraut, trotzt' ich deinem Gebot.')

Brünnhilde: Gwyneth Jones Wotan: Donald McIntyre Die Walküre The Ring of the Nibelung (Der Ring des Nibelungen) Bayreuth 1979, Patrice Chéreau / Pierre Boulez

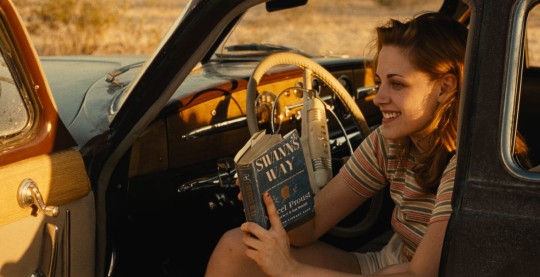

Photo: Kristen Stewart reads Marcel Proust (On the Road, Walter Salles)

#of great art#art#artist#literature#music#marcel proust#kristen stewart#writer#heroine#musician#proust#opera#kstew#richard wagner#wagner#french literature#the ring#in search of lost time#book#critics#singer#novel#remembrance of things past#à la recherche du temps perdu#goddess#brunnhilde#curtius#pierre boulez#patrice chéreau#bayreuth

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcus Curtius Plunging into the Chasm by Lucas Cranach the Elder

#lucas cranach the elder#art#marcus curtius#sacrific#roman republic#ancient rome#roman#romans#antiquity#history#mythology#europe#european#medieval#middle ages#german#renaissance

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

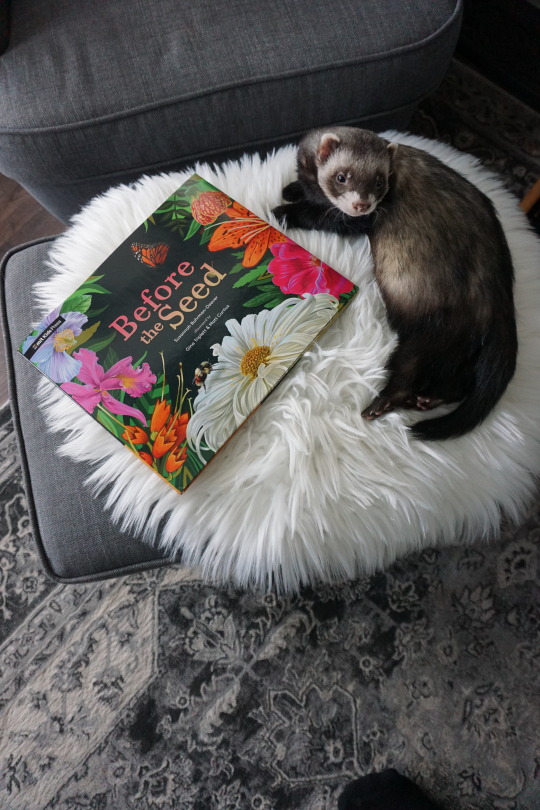

We live in a world of green that grows from seeds, but what happens before there are seeds?

#thebookferret#book addict#booklr#book worm#book nerd#book pets#book photography#bibliophile#ferret#ferrets of tumblr#pets of tumblr#before the seed#mitkids press#gina triplett#matt curtius

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

oiiii, besties!!! queria compartilhar minha felicidade do dia: fui na bienal e comprei três livrinhos e um chaveiro de hello kitty 🤓🤓🤓🤓🤓🤓🤓 minha mãe disse que eu tenho vinte anos com a cabeça de cinco mas ela não entende que i'm just a girl afeeeer 🎀💋🍰💌🐇🌷 plus que eu tô me sentindo a mais mais de tão bonitinha que tô hoje tipo eu me beijaria ? e um gostosinho curtiu minha foto no story awn own ele tem o antebraço fechado de tatuagem awn own a vida é bela demaaaaaaaaaaais

#౨ৎ⠀ׄ⠀. dear diary#e meu ex também curtiu a foto ��💥💥💥💥💥💥💥💥#ainda to atônita com isso#eu genuinamente travei no lugar quando vi a notificação#like bitch WTF#desabafo bobinho do dia 🎀🎀🎀🎀

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHY ARE THERE SO MANY REARRANGEMENT REACTIONS

#pinacol benzilic hofmann curtius lossen beckmann ANYBODY ELSE???#can't those goddamn atoms and electrons just sit in one place#why the hell are they moving#just. sit down#mine#chemblr#op

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

juro esse ngc de ver os curtido das pessoas é uma benção

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Essa é a minha coleção de CDs do MGMT até agora. MGMT é a minha banda favorita de todos os tempos, e não consigo me conter de alegria com essa nova fase que está começando na banda...

Obrigada por sempre me acompanhar nos fones de ouvido, nos momentos bons e ruins, com suas músicas mágicas. Eu amo vocês! 💗

#mgmt#photography#mgmt cd#cd collection#O JAMES CURTIU QUANDO POSTEI NO INSTA#E A ESPOSA DO BEN TAMBÉM#AAAAAAA

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

More ballet guys sketches cause I can't stop thinking about them.

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

I see you talk a lot about historiography! What would you consider the most important development of Alexander’s historiography?

What the Hell is Historiography? (And why you should care)

This question and the next one in the queue are both going to be fun for me. 😊

First, some quick definitions for those who are new to me and/or new to reading history:

Historiography = “the history of the histories” (E.g., examination of the sources themselves rather than the subject of them…a topic that typically incites yawns among undergrads but really fires up the rest of us, ha.)

primary sources = the evidence itself—can be texts, art, records, or material evidence. For ancient history, this specifically means the evidence from the time being studied.

secondary sources = writings by historians using the primary evidence, whether meant for a “regular” audience (non-specialists) or academic discussions with citations, footnotes, and bibliography (sometimes referred to as “full scholarly apparatus”).

For ancient history, we also sometimes get a weird middle category…they’re not modern sources but also not from the time under discussion, might even be from centuries after the fact. Consider the medieval Byzantine “encyclopedia” called the Suda (sometimes Suidas), which contains information from now lost ancient sources, finalized c. 900s CE. To give a comparison, imagine some historian a thousand years from now studying Geoffry Chaucer from the 1300s, using an entry about him in some kid’s 1975 World Book Encyclopedia that contains information that had been lost by his day.

This middle category is especially important for Alexander, since even our primary sources all date hundreds of years after his death. Yes, those writers had access to contemporary accounts, but they didn’t just “cut-and-paste.” They editorialized and selected from an array of accounts. Worse, they rarely tell us who they used. FIVE surviving primary Alexander histories remain, but he’s mentioned in a wide (and I do mean wide) array of other surviving texts. Alas this represents maybe a quarter of what was actually written about him in antiquity.

OKAY, so …

The most important historiographic changes in Alexander studies!

I’m going to pick three, or really two-and-a-half, as the last is an extension of the second.

FIRST …decentering Arrian as the “good” source as opposed to the so-called “vulgate” of Diodoros-Curtius-Justin as “bad” sources.

Many earlier Alexander historians (with a few important exceptions [Fritz Schachermeyr]) considered Arrian to be trustworthy, Plutarch moderately trustworthy if short, and the rest varying degrees of junk. W. W. Tarn was especially guilty of this. The prevalence of his view over Schachermeyr’s more negative one owed to his popularity/ease of reading, and the fact he wrote on Alexander for volume 6 of the first edition (1927) of the Cambridge Ancient History, later republished in two volumes with additions (largely in vol. 2) in 1948 and 1956. Thus, and despite being a lawyer (barrister) not a professional historian, his view dominated Alexander studies in the first half of the 20th century (Burn, Rose, etc.)…and even after. Both Mary Renault and Robin Lane Fox (neither of whom were/are professional historians either), as well as N. G. L. Hammond (with qualifications), show Tarn’s more romantic impact well into the middle of the second half of the 20th century. But you could find it in high school and college textbooks into the 1980s.

The first really big shift (especially in English) came with a pair of articles in 1958 by Ernst Badian: “The Eunuch Bagoas,” Classical Quarterly 8, and “Alexander the Great and the Unity of Mankind,” Historia 7. Both demolished Tarn’s historiography. I’ve talked about especially the first before, but it really WAS that monumental, and ushered in a more source-critical approach to Alexander studies. This also happened to coincide with a shift to a more negative portrait of the conqueror in work from the aforementioned Schachermeyr (reissuing his earlier biography in 1973 as Alexander der Grosse: Das Problem seiner Persönlichtenkeit und seines Wirkens) to Peter Green’s original Alexander of Macedon from Praeger in 1970, reissued in 1991 from Univ. of California-Berkeley. J. R. Hamilton’s 1973 Alexander the Great wasn’t as hostile, but A. B. Bosworth’s 1988 Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great turned back towards a more negative, or at least ambivalent portrait, and his Alexander in the East: The Tragedy of Triumph (1996) was highly critical. I note the latter two, as Bosworth wrote the section on Alexander for the much-revised Cambridge Ancient History vol. 6, 1994, which really demonstrates how the narrative on Alexander had changed.

All this led to an unfortunate kick-back among Alexander fans who wanted their hero Alexander. They clung/still cling to Arrian (and Plutarch) as “good,” and the rest as varying degrees of bad. Some prefer Tarn’s view of the mighty conqueror/World unifier/Brotherhood-of-Mankind proponent, including that He Absolutely Could Not Have Been Queer. Conversely, others are all over the romance of him and Hephaistion, or Bagoas (often owing to Renault or Renault-via-Oliver Stone), but still like the squeaky-nice-chivalrous Alexander of Plutarch and Arrian.

They are very much still around. Quite a few of the former group freaked out over the recent Netflix thing, trotting out Plutarch (and Arrian) to Prove He Wasn’t Queer, and dismissing anything in, say, Curtius or Diodoros as “junk” history. But I also run into it on the other side, with those who get really caught up in all the romance and can’t stand the idea of a vicious Alexander.

It's not necessary to agree with Badian’s (or Green’s or Schachermeyr’s) highly negative Alexander to recognize the importance of looking at all the sources more carefully. Justin is unusually problematic, but each of the other four had a method, and a rationale. And weaknesses. Yes, even Arrian. Arrian clearly trusted Ptolemy to a degree Curtius didn’t. For both of them, it centered on the fact he was a king. I’m going to go with Curtius on this one, frankly.

Alexander is one of the most malleable famous figures in history. He’s portrayed more ways than you can shake a stick at—positive, negative, in-between—and used for political and moral messaging from even before his death in Babylon right up to modern Tik-Tok vids.

He might have been annoyed that Julius Caesar is better known than he is, in the West, but hands-down, he’s better known worldwide thanks to the Alexander Romance in its many permutations. And he, more than Caesar, gets replicated in other semi-mythical heroes. (Arthur, anybody?)

Alfred Heuss referred to him as a wineskin (or bottle)—schlauch, in German—into which subsequent generations poured their own ideas. (“Alexander der Große und die politische Ideologie des Altertums,” Antike und Abendland 4, 1954.) If that might be overstating it a bit, he’s not wrong.

Who Alexander was thus depends heavily on who was (and is) writing about him.

And that’s why nuanced historiography with regard to the Alexander sources is so important. It’s also why there will never be a pop presentation that doesn’t infuriate at least a portion of his fanbase. That fanbase can’t agree on who he was because the sources that tell them about him couldn’t agree either.

SECOND …scholarship has moved away from an attempt to find the “real” Alexander towards understanding the stories inside our surviving histories and their themes. A biography of Alexander is next to impossible (although it doesn’t stop most of us from trying, ha). It’s more like a “search” for Alexander, and any decent history of his career will begin with the sources. And their problems.

This also extends to events. I find myself falling in the middle between some of my colleagues who genuinely believe we can get back to “what happened,” and those who sorta throw up their hands and settle on “what story the sources are telling us, and why.” Classic Libra. 😉

As frustrating as it may sound, I’m afraid “it depends” is the order of the day, or of the instance, at least. Some things are easier to get back to than others, and we must be ready to acknowledge that even things reported in several sources may not have happened at all. Or at least, were quite radically different from how it was later reported. (Thinking of proskynesis here.) Sometimes our sources are simply irreconcilable…and we should let them be. (Thinking of the Battle of Granikos here.)

THIRD/SECOND-AND-A-HALF …a growing awareness of just how much Roman-era attitudes overlay and muddy our sources, even those writing in Greek. It would be SO nice to have just one Hellenistic-era history. I’d even take Kleitarchos! But I’d love Marsyas, or Ptolemy. Why? Both were Macedonians. Even our surviving philhellenic authors such as Plutarch impose Greek readings and morals on Macedonian society.

So, let’s add Roman views on top of Greek views on top of Macedonian realities in a period of extremely fast mutation (Philip and Alexander both). What a muddle! In fact, one of the real advantages of a source such as Curtius is that his sources seem to have known a thing or three about both Achaemenid Persia and also Macedonian custom. He sometimes says something like, “Macedonian custom was….” We don’t know if he’s right, but it’s not something we find much in other histories—even Arrian who used Ptolemy. (Curtius may also have used Ptolemy, btw.)

In any case, as a result of more care given to the themes of the historians, a growing sensitivity to Roman milieu for all of them has altered our perceptions of our sources.

These are, to me, the major and most significant shifts in Alexander historiography from the late 1800s to the early 2100s.

#asks#historiography#alexander the great#arrian#curtius#plutarch#diodorus#justin#w.w. tarn#fritz schachermeyr#a.b. bosworth#peter green#n.g.l. hammond#mary renault#robin lane fox#j.r. hamilton#ernst badian#classics#ancient history#ancient macedonia

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Benjamin Robert after Haydon - Marcus Curtius.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcus Curtius by François Gérard

#marcus curtius#curtois#art#françois gérard#ancient rome#roman#history#livy#ab urbe condita#romans#rome#roman republic#hero#heroes#antiquity#sacrifice#virtuous#roman forum#soldier#earthquake#chasm#pit#horse#steed#stallion#city#gods#leaping#leaps#earthquakes

247 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcus Curtius John Martin (1789–1854) (attributed to) The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation

1 note

·

View note

Text

Abordagens Para Ver Só O Quê Uma Pessoa Curtiu No Instagram

No campo em constante evolução de sites de mídia social, sistemas como o Instagram estão continuamente ajustando inclusões para impulsionar indivíduo experiência e privacidade. Uma atual ajuste que capturou vários usuários desprevenidos foi a remoção da aba dedicado para ver o que os outros têm gostaram. Para quem que encantou espreitou em o digital impactos de seus amigos, essa atualização deixou um visível espaço. No entanto, medo não! Embora o Instagram pode tenha feito um pouco muito mais difícil, ainda há métodos para por favor sua interesse. Aqui mesmo estão alguns abordagens para ver quem curtiu o story de outra pessoa:

Técnicas Para Descobrir O Que Uma Pessoa Curtiu No Instagram

Descubra Seus Seguidores

Entre o mais simples métodos para ver quem curtiu o story de outra pessoa é por verificar as contas que eles cumpre. Frequentemente, indivíduos irá envolver-se com conteúdo da web que endireita com seus paixões ou reverbera com eles pessoalmente. Por navegar para o perfil do indivíduo preocupado e mergulhar em seu "Cumprindo com" listagem, você pode navegar as contas que eles aderem. Assista às postagens que pode ter acumulado suas curtidas. Este abordagem suprimento mais amplo visão de suas preferências e o material que captura seu foco.

Estudo Posts Curtidos

Enquanto o Instagram pode ter eliminado a aba especializado, a plataforma ainda permite usuários ver as curtidas nas postagens private. Se você curtir ver quem curtiu o story de outra pessoa, dê mais perto olhe as postagens com as quais eles na verdade interagiu. Apenas open um post no blog que pega seu paixão, e tap na listagem de curtidas. Aqui mesmo, você vai localizar uma escolha identificado "Outros", que permite você ver a completa lista de usuários que tem curtiu o post. Este técnica suprimentos insights direito certo conteúdo que reverbera com o usuário e pode fornecer ideias concernente suas escolhas.

Confira Gostou Reels

youtube

Com o surge de vídeo conteúdo web no Instagram, o Reels tem torna-se um destaque feature para indivíduos para engajar com e compartilhar clipes divertido. Se você pergunta a respeito os tipos de clipes de vídeo alguém gosta, você pode conferir os Reels que eles've gostaram. Comparável a assistir posts curtidos, navegar a um Reel que estimula seu taxa de juros e tap na listagem de curtidas. A partir daí, escolher "Outros" para revelar a lista de usuários quem tem com o Reel. Este abordagem suprimentos um olhar direito em o cliente vídeo preferências e o material que registra seu foco no dinâmico mundo do Reels.

Descobrir Gostou Comments

Comentários são uma parte importante de engajamento no Instagram, permitir indivíduos para expressar seus ideias e interagir com postagens de outros. Se você quer descobrir o que alguém gostou, leve em consideração verificando os comentários seção de apropriado posts. Toque em "curtidas" alternativa ao lado um comentário para revelar o clientes que tem valorizado ele. Este técnica usa entendimentos direito o certo interações e conversas que ressoam com o usuário, dá uma compreensão mais profunda de suas interações sociais na plataforma.

Veredicto

Enquanto o Instagram pode ter removido a aba dedicado para ver o que os outros gostaram, ainda há métodos para revelar essa informação. Ao verificar os seguidores do usuário, mergulhar em curtiu posts e Reels, e descobriu curtiu observações, você pode obter útil entendimentos em suas preferências e interações na plataforma. Embora possa chamar muito mais manual abordagem, a capacidade para descobrir o que alguém curtiu no Instagram permanece acessível. Então, se você tá curioso preocupação o conteúdo da web que captura uma pessoa interesse, não espere para explorar esses abordagens e por favor sua interesse.

0 notes