#crustaceans are out its time for cephalopods

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

eldritch viend concept

#risk of rain#risk of rain 2#risk of rain returns#ror2#ror#rorr#risk of rain void fiend#void fiend#risk of rain fanart#concept#art#my art#keebyz art#crustaceans are out its time for cephalopods

676 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's October and I want to talk about something creepy, so this Wet Beast Wednesday is about the lancetfish. These things look like what would happen if a fish became a vampire. Lancetfish are the only members of their family, Alepisauridae and consist of two species: The longnose lancetfish Apleisaurus ferox and the shortnose lancetfish Apleisaurus brevirostris. While they are often caught as bycatch, there is still a lot we don't know about them.

(image: a lancetfish held by an angler. Its body is long, skinny, and silvery. Its dorsal fin extends down most of its back and is supported by a series of long, thin spines. Its head is pointed and the moth is very wide. It has a large, green eye. The tail is out of frame)

Lancetfish are long and skinny fish capable of reaching up to 2.08 meters (6.8 ft). Their dorsal fins are especially notable, stretching down most of their backs and being spiny, resulting in one common name for them being the "handsaw fish". The fin likely gives stability when the fish swims fast and can fold down. The fin is situated in a groove so when it folds down, the top of the fish is smooth and reduces drag. Lancetfish are also one of the relatively few fish to have an adipose fin. The mouth is large and opens very wide. It has long, skinny teeth that point backwards and are adapted to hold onto struggling prey. Their bodies have no scales, only smooth skin with pores for the lateral line. The name "Alepisaurus" means "scaleless lizard", a reference to their body shape and lack of scales. The stomach can expand to hold a very large volume. Lancetfish lack swim bladders and are simultaneous hermaphrodites, posessing male and female gonads at the same time. They show some anatomical differences from other hermaphroditic fish, including testicles that are independent from the ovaries.

(image: a lancetfish held by a child on a boat. More detain can be seen on the dorsal fin, which includes four spines that grow long past the webbing. The tail ends in a forked fin.

Lancetfish are found worldwide except for arctic regions and are more common in temperate to tropical waters, but have been found as far north as Greenland. They are found in the mesopelagic (twilight) and bathypelagic (midnight) zones, but sometimes swim closer to the surface and can be found at a huge variety of depths. They are unusually large for fish that live in those areas. They are generally believed to be solitary, but may gather together to mate. They may also be migratory, as they have been reported seasonally appearing and disappearing in some locations. Lancetfish do also travel to colder waters if food is scarce. They are predators with extremely wide diets that include fish, cephalopods, tunicates, and crustaceans. They are also notoriously cannibalistic, as lancetfish show up in the stomachs of other lancetfish very frequently. There have even beec cases of scientists finding a lancetfish inside of a lancetfish inside of a lancetfish. They are so well known for cannibalism that they are often named "cannibal fish". Lancetfish are likely ambush predators. Their muscles are gelatinous, which is unsuitable for chases but does work for sudden bursts of speed. They most likely hang motionless in the water, waiting for prey to pass. How lancetfish reproduce is unknown, but they are probably broadcast spawners.

(image: a lancetfish in its natural habitat. It is suspended vertically in the water, with the head pointing up. Its dorsal fin is folded back)

One interesting feature of lancetfish is how slow their digestion is. Lancetfish are often found with undigested or partially digested food in their stomachs. One hypothesis is that They digest food slowly wile living a low-energy lifestyle to make the energy gained from each meal last as long as possible. Another is that the stomach acts like storage and will only begin digestion if the fish is low on energy. This provides an interesting avenue of research. Lancetfish caught as bycatch or that was up on beaches can be dissected to investigate their stomach contents, which are so much more pristine than those of other species. This means each lancetfish acts as a net, containing tons of specimens that give us a good (if biased) look at the bathypelagic food web and local biodiversity. Scientists are starting to find a lot of plastic in lancetfish stomachs. It is hypothesized that some of this plastic may be ingested by prey who practice daily vertical migration bringing tiny pieces of plastic down into deeper waters where they are ingested by larger predators. Some plastic pieces found may be too large to be explained by this method alone, such as a fragment of a black plastic bag around the same size as a hand towel found in one lancetfish. This is part of growing evidence that shows plastic pollution is not just a problem for the surface as was previously though, but exists throughout the water column.

I told you, its a vampire fish (image: a close-up of a lancetfish head. Its mouth is open, showing the teeth. They are long, skinny, and sharp. Most are short, but a few on the top and bottom are much larger than the others)

Lancetfish are not commercially caught as there is no market for them. Their gelatinous meat is considered unappetizing, though it is also said to taste sweet. They are considered pests in longline fishing industries for taking bait intended for other species. The amount of lancetfish bycatch is increasing, possibly indicating population growth due to overfishing of their competition and prey. Known predators of lancetfish include tuna, cod, opah, salmon sharks, and sea lions. Because of how deep they live, not much is known about any conservation needs

(image: a juvenile lancetfih. Its body is green and translucent and much shorter than that of the adult. The head has the same shape as the adult. The dorsal fin is much smaller and less distinct. The body is curved at the spine and the internal organs are visible through the skin)

#wet beast wednesday#lancetfish#lancet fish#fish#fishblr#marine biology#biology#zoology#ecology#animal facts#pictures#long boi

689 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Can-do Pelican Eel

The pelican eel, also known as the gulper eel (Eurypharynx pelecanoides), are the only known species of eel in the family Eurypharyngidae. They are found exclusively in the deeper parts of the water column, from depths of 500 up to to 3,000 m (1,600 to 9,800 ft), but are distributed throughout all the world's oceans.

The gulper eel is perhaps most famous for its unique body shape. Like many deep-sea fish, this species is highly adapted to its environment; maximum energy efficiency is the highest priority. To that end, the pelican eel has a large head, and a jaw estimated to be quarter of the total length of its body. The jaw is loosely hinged, meaning that gulper eels can open their mouths extremely wide. The rest of the eel, in contrast, is quite slender and long, about 0.75 m (2.5 ft) in length on average. Most individuals are black--so black, in fact, that they only reflect 0.5% of light; perfect for hiding from potential predators.

Although they look skinny, E. pelecanoides can expand their stomachs to hold prey much larger than themselves. Their primary prey consists of crustaceans and cephalopods, though they may feed opportunistically on other fish. Because it is so well camouflaged, it uses bioluminescent organs on the tip of its tail to attract prey. Gulper eels themselves are preyed upon by lancetfish and other larger deep-sea fish. To deter predators, they will gulp down a large amount of water; this stretches the loose skin around their head and throat, and inflates them to several times their usual size.

Because of their remote location, the breeding habits of gulper eels are relatively unknown. However, it is believed that smell plays a large part in attracting a mate, as pelican eels have highly developed olfactory organs. Like other eels, they're born as tiny, transparent larvae in a state known as the leptocephalus stage. At this stage, they do not have any red blood cells. Researchers aren't sure how long it takes gulper eels to become fully mature, or how long they live, but many believe that adults die shortly after mating.

Conservation status: The population size of E. pelecanoides has not been assessed, and thus the IUCN has not made a determination on its status. The greatest threat for this species is deep-sea trawling, which frequently brings up gulper eels as by-catch.

Photos/Video

Paul Caiger

Schmidt Ocean Institute

EV Nautilus Team (I highly recommend checking out their 2023 highlights reel!)

#pelican eel#gulper eel#Anguilliformes#Eurypharyngidae#eels#ray-finned fish#bony fish#fish#pelagic fauna#open ocean fauna#pelagic fish#deep sea#deep sea fish#Atlantic Ocean#Pacific Ocean#Indian Ocean#Arctic Ocean#Southern Ocean#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology#marine fauna#marine fish#Youtube

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fish of the Day

Today's fish of the day is the blacktip shark! Requested by @isrusin

The blacktip shark, scientific name Carcharhinus limbatus, is a common coastal shark. Coming from the Carcharhinidae family, this makes these sharks "requiem sharks" relating them to many other sharks in a similar area. Found worldwide in the tropic and subtropic, this shark has multiple populations spread across the pacific and atlantic coasts, the mediterranean sea, Canary islands, Galapagos islands, and Indian ocean. This shark is in water less than 30 meters of depth (about 100 feet of depth) along the continental shelf, they prefer to live along areas with murky waters, island lagoons, coral reef drop offs, and murky bays. They will also tolerate low salinities, being found on occasion within estuaries and swamps. This species is known to migrate seasonally moving north in the summers, and south in the winters to be in their prefered temperatures.

Similar to many others within the Carcharhinidae family visually, the black tip shark can be identified by the black tips along the pectoral, pelvic, doral, and caudal fins. One of the behaviours that gets these sharks mixed up with their relatives is spinning. Like the spinner shark, the blacktip shark is known to complete a corkscrew motion, launching itself out of the water as fast as 21ft/second. THe shark, once above water, will then rotate along the axis 3-4 times before landing. It is thought that this behavior is used to dislodge sharksuckers. Another behavior of blacktip sharks, is an agnostic display, which is a response to when threatened or challenged. The blacktip responds by swimming toward its competitor, rolling side to side and making sideways biting motions.

Similar to other requiem sharks, the blacktip shark can get as large as 9.2 feet maximum, but are usually only around 5 feet in length. The diet of the shark is made primarily of fish, and they will eat any fish they can catch within their range. IN addition to the fish, they will also eat other sharks, crustaceans, and cephalopods. Hunting occurs at the busiest times underwater, dusk and dawn, and although they do not always do this, blacktips will form feeding frenzies when large amounts of food are available. On the other side of the coin, the blacktip shark has no known predators as adults, but they do have several small crustacean parasites, which infest the gills.

The life of the blacktip sharks begins in swamps. The blacktip shark is known for having one ovary and two uteri, only one of which is used at a time, and sharks will get pregnant every other year after reaching sexual maturity. During the early summer or late spring blacktip sharks breed, and a total of 4-7 pups will then gestate for about a year, before being born in shallow coastal swamps, only 22-24 inches in length. These swamps are referred to as nurseries, and this is where the juveniles will spend the first months of their life, until early winter when they will migrate south.When older, these sharks will return to these same nurseries to have their children. Sexual maturation is then reached in these sharks at 4-5 years in male sharks and 7-8 years in female sharks with a total lifespan of 12 years on average, with the longest surviving blacktip living to 15 years.

Have a wonderful day, everyone!

#Carcharhinus limbatus#blacktip shark#shark#sharks#fish#fish of the day#fishblr#fishposting#aquatic biology#marine biology#animal facts#animal#animals#fishes#informative#education#aquatic#aquatic life#nature#ocean

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abraxasverse Headcanon(s) - The Skull Island Kraken

Some thoughts I had about how the Kraken from ‘Skull Island’ could be adapted into the Abraxasverse, not least when musing on its chimeric fish-cephalopod-lobster-bird design and origin, and its psychotic personality. ;)

What if the reason for the above two things is because the Abraxasverse version of the Kraken’s design doesn’t turn up in the world for the first time until the 2020s. (Of course, this would have to mean that if the events of the 'Skull Island’ series DO happen in Abraxasverse, they’ll probably have to have another Titan or at least Titan design in the Kraken’s role, like you said about wishing the Kraken’s design in the show had been more like a 'Gamera’ sea monster. ;))

Why the dating change? Well…

What if the Abraxasverse adaptation of the Skull Island Kraken is the result of a Many remnant assimilating various animals and/or Hollow Earth Titans/subtitans - mostly sea creatures like octopi, fish, squids and crustaceans, and also a bird - into itself, and then with time and some other influence, the Many instance’s DNA and biology stabilised into a permanent, fully-realised and fully-functioning organism?

Obviously, if the Abraxasverse Kraken still has its canon personality, then it very much succeeded in taking after Dear Old Triple-Dad Ghidorah.

Maybe the Ghidorah-like personality in the Kraken could also be because the Many instance which ultimately became the Kraken was part of the Many that were involved in transporting MaNi’s unattended-to head away to safety after Abraxas sucked MaNi dry and MaNi’s head ran out of power, and that Many instance had enough Many-ish physical contact with MaNi’s head before separating to permanently soak up some of the personality that had been inside the head?

---

This would certainly cleanly explain the Kraken’s bonkers design and overall being Like That, and massively up the stakes regarding Mike’s poisoning and uncertain fate in the series, not to mention a huge bump in the danger everyone on Skull Island is in!

(Also you know damn well that an AbraxasVerse take on Skull Island’s events would absolutely ensure Dog gets out of that mess safe and with his best friend Annie because I love Dog and I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t give him a happy ending! He’s a good boy!!)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

[There is no god.

…

Correction, there is a god. Just not for us. I don’t know much about the Maker, but I know this. It made mythical, ancient beings, such as humans, insects, mammals…

…

And while it made cephalopods… it didn’t anticipate our birth. The turflings and the jellyfish and the crustaceans that walk this earth, did not come from the divine hand.

I fought in the Octarian army. I was an Octoling Elite. I don’t remember the fight but I remember being injured so gravely I almost died.

…

Second correction, I did die. The world around me went from artificial, sickly light to a radiant light of utmost purity. I was met with an Angel, with a thousand heads, with even more eyes.

It gazed at me with its many faces. It had the head of a boar, a snake, a crane, a mantis, the human…. I could go on.

However… I did not see any face resembling modern day cephalopods.

No Inklings… no Octolings… no jellyfish… no Octarians…. Everything but us. We were born of human, not of god.

The Angel gazed at me for a fraction of a second. It need not to hesitate it’s decision.

“REJECTED”

It had said to me, and suddenly the light was gone.

It was all dark. It was darker than dark. It was so black, the black had wrapped around itself and made it white again. I had no body. No eyes. No heart. No mind. I spent an eternity, floating in the void where heaven’s rejects are left to rot. I touched an infinity in a second, yet it was just a mere second of infinity. And it was cold. The cold turned me inside out and froze me from whatever inside I had…

And then there was light again. I was yanked from purgatory and cemented into my inky prison.

The doctors hunched over me, told me they almost lost me… that I was too invaluable to lose… what they didn’t know is that I had lost myself.

Years went by, and I devoted my time researching our mortality. Upon finding out that there’s nothing behind the veil, I did as any sane would…

I built a powerful computer, where I immortalized my consciousness… of course.

I froze my body too… I don’t want to be trapped in binary forever.

…

…

…

But do you see now?

I’m trying to help you!

There is nothing once you die. I’m trying to save you!

…

…

…

What’s wrong with me? You don’t get it. I’m just merely choosing how I’ll spend the rest of eternity. I can’t spend it alone. I’ll need company. And I want to save my kin from endless nothingness.

Please. Join me.

Come spend my digital immortality with me…

It’s the better choice… not that you have one as it is.]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Together, they crossed lush meadows of tender seagrasses that stroked invitingly along Crowley’s bare legs and feet, so unlike the grasses of land that scratched and sliced bare skin. Fish darted past them, disturbed by their presence while above, beyond the waves flights of birds passed overhead, leaving their shadows to skim across the sandy bottom. There was so much to see that Crowley could not help but marvel at sights he could never have imagined to exist. Massive reefs buzzing with unusual sounds, teeming with color and life. Corals of all shapes and colors growing in profusion like strange stony plants, the gentle swaying of sponges and the wriggling petals of nearly transparent anemones. Schools of fish swam by them without ever seeming to noticing them. The multitudes were of all sizes; tiny fish barely visible to the naked eye, massive fish that dwarfed humans, heavily-armoured crustaceans that peeped out from under rocks, brilliantly colored shrimp and sea slugs, and even the occasional cephalopod that came by to inspect Aziraphale before disappearing off into the shelter of a crevice.

A large shadow passed by overhead, and when Crowley looked up, he saw the gentle placid passing of a massive manta ray. In his heart he felt a jolt of affection for these creatures that he had never seen alive or in their own habitations. So much lived here under the surface of the obscuring ocean that he never knew existed, and he vowed that he would use these newly acquired powers to do his best for them too.

The light that filtered down from the surface flickered and faded with the movement of the water and Crowley found himself standing at times fully mesmerized, as if unable to look away from the beauty of a branching coral, or a strange armour-plated seahorse that briefly wrapped its tail around his pointing outstretched finger like a ring, or the goings-on of a little hermit crab that made its life scurrying about the ocean floor.

A small roundish creature darted out, vivid red, and Crowley watched as it swam over to inspect him, to flit through the cloud of his crimson hair that floated around his head in a halo, to look at him with big round eyes before doing the same to Aziraphale. Short curling tentacles waggled at them; unlike other octopuses most of its tentacles were webbed and part of its body; it looked a bit like a round flatbread that had bubbled in the center while cooking.

“Is this some kind of octopus?” Crowley asked. It didn’t look like any kind of octopus that he recognized, though he also recognized that he had not seen that many octopuses to begin with.

“Oh yes.”

“One of yours?”

“Hmm. Oddly enough, no.” Aziraphale reached out to the octopus, whose stubby tentacles wrapped briefly around his index finger before letting go. “This one is their own octopus.”

“I thought you were the Lord of the Octopuses..."

x

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHEF ILONA: Hearty Squash Fishcakes

Canned tuna has become a pantry essential, but in the last 40 years has declined in its consumption due to health and environmental concerns. I grew up as a first generation Canadian to parents who grew up in landlocked countries where seafood of any kind was a rarity and as such was not something we often ate at home except for tinned tuna. Its delicate pale flesh and not overtly fishy flavour combined with an affordable price tag became a regular in the meal rotation.

With concerns over to our personal and environmental health as it relates to tuna consumption, here are some things to contemplate when buying tinned tuna:

When you are looking to buy a sustainably caught product that is lower in mercury, it is imperative that you take a good read of the labels and do a little research ahead of time. Some tuna species are riskier for consumers than others. Albacore can contain three times more mercury than skipjack because albacore are big predators, capable of growing up to 1.4 meters. Typically, it is reasonable to assume the bigger and longer-lived a predatory fish is, the more mercury it tends to have accumulated in its flesh.

As for sustainability, I have found that the Marine Stewardship Council is an excellent resource to refer to when looking to purchase seafood of any variety. Tunas range widely across the ocean, travelling thousands of kilometers during migrations. The tuna’s diets consist of fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans. Tuna fish require 25% of their body weight in food daily to maintain their energy requirements.

Hearty Squash Fishcakes

Chef ILona Daniel

Makes 16 fishcakes

1 ¾ cups canned pumpkin puree

3 x 5 ounce cans msc/sustainably caught tuna, drained

4 green onions sliced

½ corn kernels

½ cup carrot, grated

3 Tbsp cilantro, chopped

3 eggs

1 lime, juiced

1 tsp each cumin, paprika, Old Bay Seasoning, paprika, ground coriander & onion powder

2 ½ cup fresh breadcrumbs

Preheat the oven to 400F.

Mix all of the ingredients together in a bowl.

Using a large spring loaded ice cream scoop, portion and shape the mixture into flat patties onto a parchment lined cookie sheet that has been brushed with vegetable oil. Drizzle the top of the fish cakes with a little bit more vegetable oil or a little bit of melted butter for an extra flavour boost.

Bake at 400 for 15 minutes and then take the cookie sheet out of the oven, flip the cakes over and cook for an additional 10- 15 minutes. Both sides should be golden brown and crispy.

I like to make sliders/burgers with tuna cakes. I pop them onto buns with sriracha mayo, tomato, lettuce, red onion and avocado. Soup, salad, or oven fries make great side dish options for the tuna burgers.

#pei#chefilona#canadianchef#eastcoast#eater#cbcpei#chefsofinstagram#yum#explorecanada#foodwriter#canadasfoodisland#tuna#can tuna#canned tuna#tunarecipe#budgetfriendly#cookingonabudget#budget meals

0 notes

Text

Today's #Spectember concepts come from three submitters: anonymous, Jonas Werpachowski, and Novaraptoria.

Despite having a convergent resemblance to penguins or gannetwhales, the humdertaker (Suchomergus pollinctor) is actually a distant descendant of modern hummingbirds.

Its ancestor was a hummingbird species similar to the tooth-billed hummingbird, with tooth-like pointed serrations along the edges of its beak – initially developed for fighting, but later co-opted for better catching insects. Some of these hummingbirds shifted their diet fully away from nectar and became aerial hunters more like their relatives the swifts, and one lineage that commonly fed on insects at the water's surface began also snatching up aquatic prey like tadpoles and small fish.

These birds became larger kingfisher-like divers with waterproof feathers, and eventually some became increasingly aquatic, spending most their time swimming at the surface of lakes and rivers like mergansers or loons. These forms rapidly became flightless, specializing for penguin-like wing-based swimming, but due to their front-heavy build and ancestrally small legs also became completely unable to stand or walk on land, instead restricted to an ungainly motion somewhere between a tobogganing penguin and stiff-spined galumphing seal.

Growing up to about 2m long (6'6"), the humdertaker is a semi-aquatic ambush predator occupying a similar ecological role to small crocodilians. With a heavily serrated beak able to hold onto slippery prey, it feeds mainly on fish, amphibians, and crustaceans, but will also opportunistically snatch other animals from the water's edge and scavenge on carrion – and like a giant aquatic version of a shrikes it often caches "larders" of surplus food on snags in the water.

Although it has a much slower metabolism than its nectar-fueled flying ancestors, it has retained some of their other biological quirks. Tolerance for very low oxygen and the ability to enter a torpor-like resting state allow it to hold its breath underwater for much longer than many other air-breathing vertebrates, and to better conserve its energy during periods of food scarcity.

———

One offshoot lineage of small humdertakers began using their beaks and wings to excavate burrows into the riverbanks, and gradually specialized more and more for digging rather than swimming.

The humderminer (Iposkapteryx werpachowskii) is an especially mole-like form, a fully subterranean tunneler with reduced eyes and broad shovel-like 'flippers'. Only about 10cm long (4"), it primarily hunts worms and other small underground animals, and has retained somewhat iridescent plumage due to the structural benefits when moving through soil.

———

The humdingers are another offshoot from early humdertakers, specializing into even more aquatic lifestyles and eventually moving out from freshwater into the ocean.

Voragornis novaraptoriae here is one of the largest humdingers, about 5m long (16'4"). It's a fully wing-propelled swimmer with a highly streamlined body, and its still-relatively-small legs are adapted into rudders and stabilizers similar to the hind flippers of turtles.

It's an especially accomplished diver, able to reach depths of close to 2000m (~6600 ft), preying on soft-bodied deepwater cephalopods and fish. Lacking echolocation it mainly uses sight to hunt in the deep dark waters, looking for glimpses of bioluminescent prey.

Although humdingers are the equivalent of "whale-sized" compared to their much tinier hummingbird ancestors, they're currently limited from growing much larger due to their reproductive requirements – these almost-fully-aquatic birds do still need to be able to haul themselves out onto land once a year to molt and breed.

Much like penguins humdingers undergo a seasonal "catastrophic molt", replacing all their insulating feathers at once and being stuck on shore unable to swim for a few weeks at a time. This molting coincides with their nesting season, when females use their flippers to dig out a turtle-like nest on the shore – burying the clutches to incubate since their bulky bodies are too heavy to safely sit on them. They'll guard the nests until they've completed molting, but then abandon them, leaving the young to hatch superprecocial and fully independent a few more weeks later.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#spectember#spectember 2022#speculative evolution#hummingbird#apodiformes#bird#art#scientific illustration#punningbirds

590 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best News of Last Week

Edition #018 - A lot of environmental news this week:

1. Octopuses, crabs and lobsters to be recognized as sentient beings under UK law following LSE report findings

Octopuses, crabs and lobsters will receive greater welfare protection in UK law following an LSE report which demonstrates that there is strong scientific evidence that these animals have the capacity to experience pain, distress or harm.

The UK government has today confirmed that the scope of the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill will be extended to all decapod crustaceans and cephalopod molluscs.

2. Great Barrier Reef 'gives birth' in massive coral spawning event

Australia's Great Barrier Reef is spawning in an explosion of color as the World Heritage-listed natural wonder recovers from life-threatening coral bleaching episodes.

Scientists on Tuesday night recorded the corals producing billions of offspring by casting sperm and eggs into the Pacific Ocean off the Queensland state coastal city of Cairns. The annual spawning event lasts for two or three days.7

3. Germany's new government to give millions of people a 25% pay rise by hiking the minimum wage

Germany plans to increase its minimum wage by the equivalent of nearly $3, or a 25% rise. It's part of a deal agreed by a three-party coalition to form a new government.

As many as 10 million workers could receive a pay rise in Germany under plans unveiled by the country's incoming government.

4. Portugal to stop using coal

Portugal becomes fourth EU country to stop using coal plants. Environmental activists are welcoming the end of electricity generation from coal in Portugal, though they said Monday the possible conversion of the country’s last coal-fired power plant into one that burns wood pellets would be a step in the wrong direction.

The Pego plant located 150 kilometers (90 miles) northeast of the Portuguese capital Lisbon stopped generating over the weekend, as Portugal became the fourth European Union country to stop burning coal to produce electricity. Belgium quit coal in 2016, and Austria and Sweden followed suit last year.

5. Unconscious mom saved by heroic 3-year-old who learned to call police from cartoon

youtube

A three-year-old boy from West Midlands, U.K. dialed police after his mom fell unconscious earlier this month, having picked up the skill from an unlikely source: a YouTube cartoon. The heroic toddler's impressive abilities, especially in a time of crisis, underscores the life-saving potential of teaching children how to handle emergencies from a young age.

Toddler Thomas Boffey dialed 999 after his mom, 33-year-old Kayleigh Boffey, fell down the stairs. Upon hitting her head, the mom reportedly lost consciousness. Because he had watched Robocar Poli—an animated kids' show from South Korea that features a police car, ambulance, and fire engine—Boffey knew to call 999.

6. You can’t see them to count them, but Amazonian manatees seem to be recovering

Following intense commercial hunting from the 1930s to the 1950s, scientists and community members are seeing signs that the manatee population in the Amazon is growing. A study carried out in the Piagaçu-Purus Sustainable Development Reserve in the state of Amazonas shows large manatee populations nearby human communities, apparently co-existing in peace.

7. The world finally has a malaria vaccine.

Since 2019, more than 800,000 African children have had at least one dose of the RTS,S vaccine as part of a pilot in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. Now, with the right investment, millions more children could be immunized and grow up with less malaria, fewer hospitalizations and healthier lives.

____

That's it for this week. Until next week,

You can follow me on twitter . Also, I have a newsletter :)

Subscribe here to receive a collection of wholesome news every week in your inbox :D

473 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please share your knowledge of goblin sharks! ❤️

Please share your knowledge of goblin sharks! ❤️

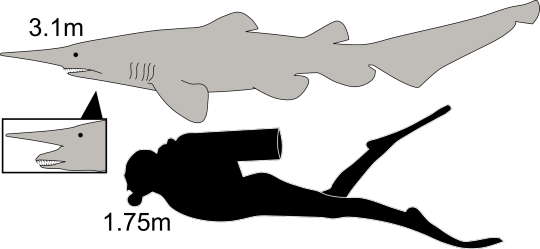

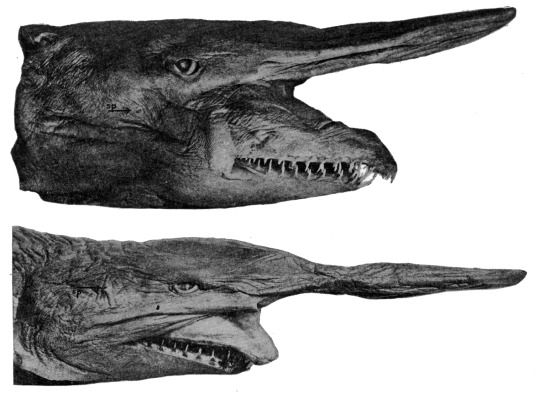

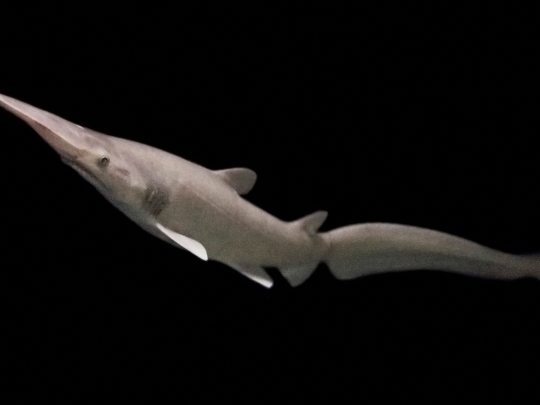

Goblin sharks huh… those with the pointy noses ala probably why they’re called “goblin” sharks… okay, I can do that!

Goblin sharks: the Basics™

[Image source: mentalfloss.com]

Okay so, these weird looking kids drawings brought to life are actually a real rare species of deep-sea shark — that means they live deep out in the ocean, something like 100 metres (330 feet) below in the clear blue. They’re found throughout the world and there’s some researchers out there who argue Goblin Sharks can dive over 1300 metres down (4270 feet) for short pockets of time. That’s almost one-seventh of the height of Mount Everest (29000 feet) by the way. For y’all Americans, your football fields are about 91 metres long, so that means the Goblin Shark can possibly dive 14 football fields.

Not gonna lie, I’m pretty impressed; and slightly scared lol.

Goblin Sharks are the only surviving member of the Mitsukurinidae family of sharks; they have a lineage then of 125 million years and then some! They come from the larger order of Lamniformes which get called Mackerel Sharks and one of its cousins is the Great White.

Heckin’ interesting family reunion I guess; being the only member of that branch of the family still kicking when you see the beefcake great-great-great baby cousin of yours the Great White looking like the Ideal™ Shark. Poor Goblin Shark with his absurd body design and old as balls evolutionary structure.

It hunts cephalopods and crustaceans (squid and crabs or shrimp basically) as well as teleost fish. Teleost fish are, to put it simply, a bony fish that can do like a shark with their jaw and pop them out. Because fish needed to become more terrifying to consider, of course. So the Goblin Shark hunts squid, shrimp, crabs, and fish like fucking Giant Oarfish and the Anglerfish and even Seahorses; depending on where they are in the oceans.

Lovely.

[Image Source: factanimal.com]

Goblin Sharks were “discovered” some time in the 1800s after a description of an immature male was caught in Sagami Bay, Japan and described by David Starr Jordan in 1898, an American ichthyologist who determined that the Goblin Shark caught in Sagami Bay was a new genus and family entirely from other sharks known at the time. Jordan gave the name for the Goblin Shark based on the ship master (Alan Owston) who caught it and the professor at University of Tokyo who assessed it (Kakichi Mitsukuri). Thus, the Goblin Shark’s scientific name is: Mitsukurina owstoni.

[Image source: Wikipedia]

Incidentally, Goblin Shark as a term is a calque (or loan translation borrowed from another language) of its traditional Japanese name tenguzame which is a creature in Japanese mythology with a long nose and red face. Goblin Sharks are also called Elfin Sharks by the way; again, probably due to their facial structure with the nose… idk, that one still confuses me.

Goblin Sharks are considered to be one of the oldest root members of the Lamniformes order; basal meaning base aka near the root/actually the root of a species/order/family etc. Because it’s the last member of a lineage that dates back to the — Middle Eocene (which is around 49 million years ago by the way) for the Goblin Shark as we know it right now — Cretaceous (125 million years ago), the Goblin Shark is called a “living fossil” because it also retains several of the traits “primitive” sharks once had.

Goblin Shark: Description

Goblin Sharks are pink, not the traditionally expected countershading black/grey/blue/some colour and white belly set up other sharks have, and have that long flat snout with very poppy-outty jaws (protrusible, the word is protrusible) with nail-like teeth. Because needle teeth weren’t bad enough obviously. They can grow around 3 to 4 metres, around 13 feet long, but some have been recorded around 6 metres (20 feet).

[Image source: Wikipedia]

It also has a flabby old body with small pectoral and dorsal fins which suggest it’s not a fast mover like its cousin the Great White. So this is a pink, blobby thing with stubby fins and a pointy nose that definitely means it ain’t winning any Prettiest Of The Ocean competitions any time soon. Poor fella.

[Image source: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute]

Goblin Shark snouts are long and flat like a blade (think… which one was it in Pacific Rim with the pointy nose over its face… that’s basically a Goblin Shark head lol), and the snout decreases in length the older they get. They have little eyes with no protective nictitating membrane and behind each eye is a spiracle that leads to the respiratory system of an animal; basically nostrils. Their jaws can extend almost as far as to the end of their snout which is just Not Okay. And with something like 100 rows of teeth in its jaws, you do not want to be bitten by this long nosed nightmare blob from the depths.

[Image source: Wikipedia]

Goblin Sharks also only have five gill slits which are pretty short to be honest. With a relatively slender, flabby body, and two small dorsal fins that are similar in size and shape, as well as little rounded pectoral fins, Goblin Sharks really don’t scream Effective Fast Predator at all. They’re more ambush predators since they can extend those damned jaws out so damned much. Unlike a lot of other sharks, Goblin Sharks have a rougher skin texture since their dermal denticles are shaped like spines with ridges lengthwise which point upright… charming.

[Image source: National Geographic]

Like other sharks, the Goblin Shark has a field of ampullae of Lorenzini which allow it to sense electric fields in the water that prey produce. This is one of the reasons, by the way, why it can be advised that you punch a shark in the snout when attacked, because that’s where the ampullae of Lorenzini are located. A punch to the snout is essentially a burst of loud as fuck static in your headphones for a shark.

Might get your arm bitten off in the attempt though.

Anyway, digression!

Goblin Sharks: Where to find em

You’ll find these nightmare nail teeth monstrosities in all the major oceans from the Atlantic where its been found in the Gulf of Mexico, southern Brazil, France, Portugal, and Senegal (to name a few), to the Indo-Pacific and Oceanic where it’s been found in the waters off South Africa, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia. So yeah… basically everywhere. Great!

[Image source: Wikipedia]

Just something extra

So back when the Goblin Shark was being discovered and information about it getting published in journals etc, in 1910, a researcher wrote about the Goblin Shark and, honestly, bit harsh man… bit harsh. The wrote:

“...the new shark is certainly grotesque… the most remarkable feature is the curiously elongated nose…” — Hussakof, L, 1910, The Newly Discovered Goblin Shark of Japan. Scientific American: A Division of Nature.

So there ya go! Stuff about Goblin Sharks! Now I’m going to go be thankful I don’t swim in the ocean for the next ten hours while rocking in a corner :D

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

#1902 - Phocarctos hookeri - New Zealand Sealion

Spotted on the beach at Sandfly Bay on the South Island. @purrdence didn’t want to get any closer because she didn’t want to disturb the animal, and sealions are entirely capable of biting your face off if they feel threatened. They are one of the largest remaining native animals in New Zealand, with males up to 350 centimetres long and weighing up to 450 kilograms.

The Māori call them pakake, whakahao (male) and kake (female), and they’re endemic to New Zealand and its subantarctic islands. They’re the rarest sealion species with only 12,000 or so in the world - 99% of the global population breed on the Auckland and Campbell Islands, and they only started pupping again on the mainland in 1995. The entire mainland population was wiped out by hunters in the mid-19th century, but not for the first time. A previous genetically distinct population had been wiped out by the Maori between 1300 and 1500 CE, until they were replaced by ones from the Subantarctic, and a third population in the Chatham Islands wiped out by the Moriori around 1500 CE.

Pakake are unique among pinnipeds in that they prefer to have their pups up to 2km inland, in forests. This allows them to avoid aggressive males, severe weather, and parasitic infection, and is probably only possible because New Zealand had no large predators apart from the enormous Haast’s Eagle, right up until humans arrived. The eagles probably enjoyed the change in diet when they did.

The sealion’s diet includes various fish, crustaceans, cephalopods, seabirds, and other mammals including the New Zealand Fur Seal, but over a quarter of adult seals show scarring from close encounters with Great White Sharks. Populations are also threatened by starvation, introduced disease, car collisions when moving inland to pup, and attacks by people and dogs.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taming the Tiger Shark

The tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) is a common sight for divers, fishermen, and tourists in the tropical waters of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. They are often found around sea grass fields or coral reefs, and tend to prefer warm, shallower waters near the coastline or surrounding atolls and islands. The northern end of their range extends up to the northern borders of the United States and China, while their southern range reaches down to Brazil, Madagascar, and the eastern coast of Australia.

While they're slightly smaller than great whites, G. cuvier is still one of the largest carnivores in the ocean. Adults can grow up to 4.7 m (15 ft 5 in) long and weigh between 300 and 900 kg (700 and 2,000 lb). Females tend to be larger than males, but the two sexes are otherwise indistinguishable. Individuals are typically bluish gray or green, with a white or light yellow underbelly; this provides them with camouflage, as fish swimming overhead or below are unable to pick out the shark's silhouette against the dark or light background, respectively.

As an apex predator, G. cuvier has few predators of its own. Juvenile tiger sharks will often fall prey to other sharks, including adults of their own species. Orcas are also occasionally known to prey on tiger sharks, but these occurrences are rare. In their own food chain, G. cuvier has a large appetite and will eat almost anything. Coral reef fish are a common target, though their speed and small size makes them harder to catch. More often tiger sharks will prey on cephalopods, crustaceans, sea snakes, turtles, sea birds, and a host of marine mammals like dolphins, dugongs, sea lions, and young, injured, or dead whales. Inadvertently, tiger sharks will also consume garbage such as bottles tires, earning them the nickname 'The Garbage Can of the Ocean'.

Tiger sharks are primarily active at night. Contrary to other sharks, G. cuvier has excellent eyesight, as well as a keen sense of smell. In addition, tiger sharks have two special sensory organs. The lateral line extends down the length of the body and can detect minute vibrations in the water. Ampullae of Lorenzini are small electroreceptors located on the snout; these detect the weak electrical impulses generated by prey. All these features make it easy for tiger sharks to find a meal, and once located their body shape allows them to put on a burst of speed and make quick turns to catch their target. Most of the time, this hunting practice is done alone, but occasionally groups of tiger sharks will gather to scavenge a large carcass or for the mating season.

Male tiger sharks mate every year, while females only reproduce every three years. Breeding seasons differ based on location; in the Northern Hemisphere mating occurs between March and May, while in the Southern Hemisphere it's between November and January. During this time, dozens or even hundreds of sharks may gather to find mates. Females carry their young for up to 16 months, at which time they give live birth. Tiger sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning that eggs are fertilised and hatch inside the mother; this species is also unique in that they employ a technique called embryotrophy, in which young gestate in sacks which are filled with an embryonic fluid. A single litter of tiger sharks may contain between 10 to 80 pups, and each one may live up to 12 years in the wild.

Conservation status: The IUCN has classified the tiger shark as Near Threatened. While exact numbers are unclear, a great many tiger sharks are killed each year for their skin, fins, and liver. This species also has a reputation for vicious attacks, and while they can be aggressive when threatened, only a handful of shark attacks occur each year.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Neil Hammerschlag

Brian Skerry

David Snyder

#tiger shark#Carcharhiniformes#Galeocerdonidae#ground sharks#sharks#cartilaginous fish#fish#marine fauna#marine fish#coral reefs#coral reef fish#coasts#coastal fish#atlantic ocean#Pacific Ocean#indian ocean#indo pacific#animal facts#biology#zoology

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancardia's Unusual Animals--The Kraken

Classification: Beast (arthropod)

Habitat: Deep ocean, concentrated around continental shelf zones.

The Kraken is one of the most feared and revered oceanic predators, as well as one of the largest. It isn’t the apex predator, however, especially not as a much smaller juvenile. These unusual crustaceans have traded out a jointed tail and lower body for a membranous, tough, multi-branched back half, its structure supported partially by water and partially by an internal fibrous pseudo-skeleton made up of struts and discs that produce a very flexible result. Each of these “tentacles” is capable of prehensile grasping as well as a whipping motion which both intimidates parasites and intruders away from itself and provides swimming propulsion. For more delicate movements, kraken possess a soft-tissue water siphon coincidentally very similar to the siphon of a cephalopod, and it can also be found “walking” along rocky, cold seafloors in the outer shallows’ faint sunlight using its front pair of powerful claws, especially while foraging and feeding. Its front end very strongly resembles a black-colored lobster with long paired feelers, large, reflective eyes that give the kraken great clarity of vision, and high, pointed ridges along the back of its shells.

Kraken begin life after hatching from small eggs hidden gravelbeds and sandy bottoms on the ocean shelf by their parents. These eggs number up to 10,000 per pair of kraken, though most of the eggs will be discovered and eaten by a variety of bottom-dwelling fish, crustaceans, and other creatures before they have any chance to hatch. Of the roughly 1,000 tiny kraken that hatch per clutch, very few of those survive to adulthood; a freshly-hatched kraken is only slightly larger than a human baby and has a soft carapace that needs days to harden, and their natural predators include a wide variety of shark species, seals and sea lions, orca whales and some other predaceous tooth whales, conger eels, gajah-mina (“fish-elephants”) and giant sea-worms. Kraken juveniles grow quickly, and molt eight times in their first year to reach a size similar to that of a large shark or dolphin—at which point they lose many of their hatching predators. Once larger than a human, young kraken are generally only susceptible to attack from orcas, livayatan, gajah-mina and large sharks.

Kraken take roughly fifteen years to reach adulthood, and continue growing slowly throughout their lives. The average adult kraken measures 14 meters from head to the end of the tentacles, and weighs in excess of 18 tons. Some particularly venerable kraken have measured in at more than 20 meters. Kraken do not have a known natural lifespan—most kraken live between 20 and 90 years, and most of all ages in this range suffer premature mortality from their main predators. It is believes that kraken are like some other low-metabolism sea beasts, and can live as long as their food supply and space supports them. Due to its massive size, there are a select few animals which can hunt kraken adults: The Sperm Whale, which hunts these odd crustaceans at certain times of year or in the absence of giant and colossal squid shoals, and the Livayatan, which is the Ancardian oceans’ apex predator. Kraken themselves are primarily carnivorous, though do opportunistically consume kelps in certain times of abundance. As hatchlings, they root around for sea-worms, krill, and small bottom-dwelling crabs and fishes; as juveniles they scale up to hunting larger bottom-feeders such as skates, smaller rays, flounder and invertebrates like spider crabs and sea urchins. As adults, kraken hunt a variety of animals, but seem to prefer hard-shelled creatures: Giant clams and abalone are favorites, which the kraken crushes open with its powerful claws, but it also pursues deep-water swimmers like oarfish, slower-moving squid, giant dragonfish and larger rays and carpet sharks. Kraken are also surprisingly docile regarding swimmers and divers as adults—it is the human-sized juveniles which respond most defensively to human-sized creatures approaching them—and most kraken ignore creatures of a human-like size and shape unless attacked by one. The violent reputation of kraken is owed to the behavior of some individuals after being disoriented by electrical storms at sea and forced to surface—several reports of kraken latching onto ships and boats and capsizing or breaking holes in them are the result of the kraken misidentifying ships as pieces of floating driftwood and flotsam, and clinging to it to avoid being further battered by waves during storm swells.

#ancardia#ancardian homebrew#bestiary#mixed media#creatures#animals#Ancient Domains of Mystery#ADOM#Dnd-like#Kraken#sea monster#big strange lobster dudes#not even the biggest sea creature in this homebrew

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Middle Glaciocene: 110 million years post-establishment

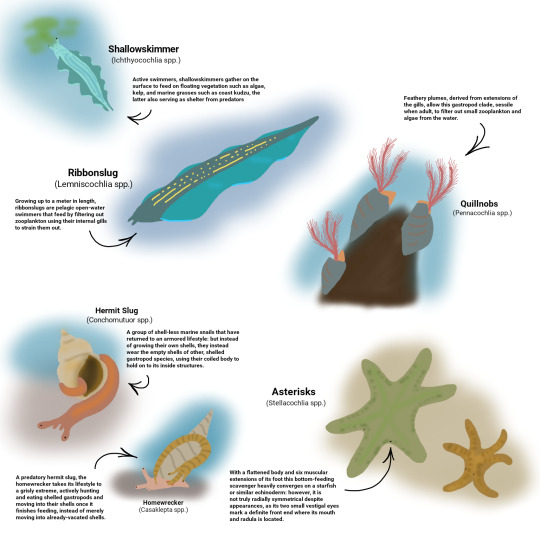

Tales of Snails: Marine Gastropods of the Middle Glaciocene

Since the beginning of the age of life at the start of the Early Rodentocene, the hamsters had dominated megafaunal niches on the planet as the ecosystem's sole vertebrate, while the shrish-- swimming crustaceans descended from krill-- have flourished in the oceans with the absence of piscine competitors into shoalers, filter-feeders, burrowers and shark-like predators. But for the past 110 million years another clade in the seas had been slowly but surely rising in prominence: the gastropods.

Descended from a few species of marine snails introduced into the waters of HP-02017, indeed, perhaps accidentally as a few dormant eggs that remained attached to the transplanted coral and algae during the planet's founding period, the colder, nutrient-rich waters of the Glaciocene has given this slowly-growing clade a chance to explode into a diversity unlike anything before. Now the gastropods are found in all of the seas and oceans worldwide, in a stunning variety of forms one would never have assumed from their humble ancestors.

Basal forms akin to conches and whelks are very abundant in the shallow-sea reefs, grazing on corals and algae and in turn being food for a wide range of aquatic fauna. Some lineages independently lost their shells, forming a polyphyletic group of "slugs", with one group, the slugworms, developing brilliant coloration and showy displays in a manner quite akin to Earth's nudibranchs. But more remarkable are another group of these shell-less "slugs" that, instead of creeping along on the sea floor, instead become active swimmers that propel themselves through the water with muscular contractions of a membranous fin-like extension of their foot- the pescopods.

Pescopods, in all their diversity, have avoided competition with the shrish with the help of a key gastropod feature: the rasping radula, or toothed tongue, that allow them to file away at tough food that the shrish are less-equipped to deal with. While most shrish are filter feeders, bottom sievers, or active predators, the pescopods gnaw away at floating vegetation, scavenge on sunken carrion, and feed on corals, sponges and hard-shelled bivalves with the help of their unique mouthpart allowing to rasp, scrape, drill and shave their way into a broad range of niches that are less pressured by the shrish.

Among the diversity of gastropods now colonizing the ocean are a diverse array of snails and slugs that, in the vacancy of many niches in the sea have twisted apart the basic gastropod body plan into forms better filling empty marine invertebrate niches. Shallowskimmers (family Ichthyocochlidae) are among the most widespread of the swimming slug-like forms, gathering near the surfaces of shallow tropical seas to feed on algae and water plants, and flourish in such numbers that certain species of marine predators such as shrarks and cricetaceans have specialized to specifically feed on them. Their bigger cousins, the ribbonslugs (family Lemniscochlidae) drift slowly across the open seas in enormously large numbers filtering out algae in a manner akin to the manta rays of Earth's oceans.

While some species of aquatic gastropods became highly active swimmers, other would become bottom feeders that are sessile, or at least nearly so. Quillnobs (family Pennacochlidae) are one such species: originating from a hard-shelled ancestor, these snails have evolved to fuse themselves to a single spot once mature, never to move again. Anchored to the spot by secreted cement derived from the mucous slime coat of most snails, they extend feathery extensions of their gills to trap drifting algae and zooplankton for nourishment. As they no longer move, they tend to cluster in large groups as to easily find a mate, and at times tend to overwhelm reefs and form entirely new biomes made entirely of these strange, barnacle-like creatures.

Some other bottom feeders would take on forms akin to echinoderms--a clade highly diverse in Earth's oceans, but absent here. The asterisks ( family Stellacochlidae) are one such clade of bottom-dwelling, soft-bodied "slugs" whose foot possesses strong muscular extensions that help them anchor themselves to hard objects on the sea floor or on food sources that they feed on. With small, vestigal eyes that can only detect light and dark, asterisks rely mostly on touch, smell and taste to navigate, feeding on whatever they can find at the ocean floor, including algae, sponges, corals and scavenging sunken carrion of shrish and marine hamsters such as seavers, though some asterisks are active predators of hard-shelled prey such as quillnobs, using a specialized radula to drill right into their shells.

But even basal forms can be downright bizarre in their own ways. Of the basal, unremarkable clade of shell-less slugs is one truly bizarre clade that seems almost like an example of evolution gone wrong: the hermit slugs (family Conchomutoridae). Hermit slugs have, over the years, lost their protective shells. But now they have returned to a lifestyle akin to a typical hard-shelled snail, except that instead of being born with a shell of their own, they instead borrow one. Shells of aforementioned whelk or conch-like species are particular favorites, but they are not especially picky: some use broken-off corals, shed shrish exoskeletons, and even the seed pods of coastal-growing cloverferns that end up in the water. And one genus, in its quest for house-hunting, turned to active predation in order to acquire both a house and an easy meal in one: the homewrecker (Casaklepta spp.) which hunts shelled gastropods, harpooning them with specialized neurotoxins, then gradually eats away all the soft tissues of their unlucky victim, leaving only an empty shell--which the homewrecker then moves right into.

But without a doubt the most fascinating and derived of these marine snails are the notiluses (family Gastrocephalopoda), a group of basally-shelled gastropods that have developed six fleshy arms from the anterior portion of their foot, functioning like grasping arms that they use to move about and capture food. Some of the shelled forms are ammonite-like floaters that feed on small shrish and crustaceans, while others are bottom dwellers that use their arms to clamber about on the sea floor.

This lineage would eventually, during the Therocene, spawn a lineage of shell-less active swimmers with rippling foot-fins convergent with the pescopods-- the skwoids (subclade Cochleoteuthidae), which are even more convergent with Earth cephalopods such as octopi and cuttlefish. However, they are distinct in many ways: their eyes, surprisingly well-developed for a snail, are mounted on retractable stalks, their arms, which only have six instead of a cephalopod's eight or ten, are equipped with a single row of rectangular gripping pads as opposed to round suckers, and instead of a hooked beak, possess toothed radulas that are equipped with harpoon-like ends for spearing their prey.

Skwoids are exclusively carnivorous, feeding on shrish, crustaceans, and other snails such as pescopods, and are found in a wide array of aquatic environments. While most live in the sea, a few have ventured into freshwater, and have colonized rivers and streams as well, with freshwater skwoids typically being very small, measuring at most several inches and feeding on small shrish, aquatic insects, and on rare occasion small swimming pondrats as well. They are in turn prey for many other predators as well: and many species defend themselves by squirting a thick, gooey mucous that forms net-like ropy threads that entangle and confuse enemies and allow them to escape.

But in the deep, chilly regions of the southern Centralic Ocean, in the waters surrounding Peninsulaustra, there lives one species that dwarfs them all: the giant skwoid (Craccinus relasi). This deep-water species thrives on the abundance of massive swarms of aphotic-zone pescopods and shoals of shrish that gather at the nutrient-rich upwellings from the deep currents that are a breeding ground for plankton. In this near-abyssal region, relatively free of the air-breathing marine hamsters, the giant skwoid is free to grow to tremendous sizes, straddling the absolute upper limit for an invertebrate: a body length of up to four meters, coupled with six long arms extending up to an additional eight meters tops off its full length to a whopping twelve meters in the largest specimens, though smaller sizes of eight meters or less, with two-meter bodies, are far more common.

With its powerful arms, immense size, and harpoon-like radula, the giant skwoid is a force to be reckoned with: while generally a placid creature, it is a dangerous quarry for even the largest of the predatory shrish to tackle should it lash out when threatened, and for the majority of its existence during the Late Therocene and Early Glaciocene, the giant skwoid enjoyed a relatively safe existence. But as the cold seas of the Glaciocene favored ever-bigger marine hamsters, reaching sizes unlike anything before, the Middle Glaciocene will soon have the giant skwoid finally meet its match-- in the form of the largest marine predator, and largest hamster yet, to live on the planet of HP-02017.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

History Of The World - Part 5

Greetings learned traveler.

It has come to my attention that there are still many who don’t yet have a sound grasp of the history and origin of our most illustrious and beloved Saint Lura. Fear not, I have transcribed for you here an excellent excerpt from the authority on the subject, Eylia Featherhurst, an accomplished magus in her own right. I hope this serves to illuminate you on the history of The World and by extension, shed light on things happening in the magi’s tower at present.

Behold.

Lachrimory of Lura

Lura was their name. They were known variously as Lura the Red, or Lura Cruensanti, or Lura the Savior.

Lura was said to have been born Aethla fen Seon to a poor but beloved

Trita-wed family circa 35 B.L. They’d had an ordinary childhood and a mercantile livelihood until the age of 29, when the Tide-fever of 6 B.L. that swept through the Mitterean region nearly claimed their life.

Though spared from the ever-scorch of the Southern desert and the ever-frost of the Northern wastelands, the temperate Mitterean was ripe with disease at that time.

Some 50 million lives were lost to the terrible seaborne malady within a decade. Having narrowly escaped death, Aethla was bed ridden for months thereafter and began to manifest visionary abilities like healing by song and seeing through dreams. Their family and village were among the first to be saved.

Soon, word spread, and Aethla was discovered by the Ancient Order of Magi and given the Unveiling rite, whereby their true name, Lura, was revealed to them.

But all was not well. The world was in upheaval, violent seamouth eruptions and famine shook the land and its inhabitants. Idol-worshipping tribes and warrior-ruled city-states resorted to rituals and sacrifices to their multitudes of Devarna and in desperate attempts to curry favors and protection. But these the Devarna were silent.

That’s when Lura was granted a prophetic vision by the Devarna and learned of the Rite of Hsava, an ancient ritual of offering one’s very Waters to the Seas and to the Devarna in order to heal The World’s wound and restore its health and balance.

When Lura and their disciples began spreading the rite, indeed, did rejuvenation came to pass. The fevers cooled in many of the sick, and the Seas themselves relented in their tantrums.

Scholars and Magi disagree over whether it was the efficacies of the rite itself or the preternatural determination of Lura the Magus that expanded Thearudin influence, but all concur that by age 36, Lura had united the ordered world under AOM and became its leader as Lura The Anumatta, one who is beyond greatness.

Things, however, would take an unexpected turn, just as Lura and their order were enjoying a streak of success with dispelling the sickness. On an ominous daybreak, when the horizon was painted sanguine by S’ruthrul’s rising, a singular massive eruption shook the continent like a thunderbolt out of cloudless seas, flattening entire cities and forests. By forenoon, birds fell like rain, creatures of land hid in their burrows, and uncountable carcasses of fish, eels, crustaceans, cephalopods and agari surfaced and covered every seamouth from the southern tip of Tulan Desert to the southern edge of the Kahna Tundra.

It did not rain for two full turns. Peoples had only the moisture stored in grand-succulents to relieve their deadly thirst. Many perished.

The Devarna were silent. Some said that even they were in despair at the ruin facing the world. But unwilling to bow defeat in even such a dire circumstance, Lura went beyond the efforts of ordinary recluses and magi and sought true knowledge beyond the realm of the Devarna. They sealed themself within a sanguine shrine and meditated for 23 unbroken days to seek an answer from S’ruthrul themself.

Reliable accounts of this period are scant and prone to inconsistencies, but what could be patched together from extant sources suggests Lura appeared before their followers, some 50 thousand thousand souls young and old, through a miracle of the seeing bowls, where the water of every bowl in every household turned a deep crimson and Lura’s image could be seen and their voice heard. They urged, roused, inspired and instructed the great throngs of suffering and destitute people to carry out a grand Rite of Hsava, as commanded by the great S’ruthrul. As the ardent and devout followers that they are, all 50 thousand thousand people obeyed.

Once the sealife began to recover and the world stabilized enough to support agriculture and trade for the survivors,

Only an estimated 1 million people remained in all the lands of the Mitterean, the rest followed Lura’s words, waded into the Seamouths, and gave their Waters to the Seas so that The World may be healed. Thus is Lura remembered as the Savior of humanity. They themself was never seen again. Many believe that they had attained Nisipetti as all the sanguine sages of present day still do. Some claim to possess Luran relics, hairs, ashes, prayer beads, seeing bowls, and so on and so forth, but no authenticity is attributed by any of the extant magus orders.

Excerpt from the Savior - A Brief Recounting, Eylia Featherhurst, K.S.M, OGS Publishing 515 DS

26 notes

·

View notes