#contrarianism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

running people-pleaser software on contrarian hardware and vice versa

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because I'm stressed out right now, and also because i'm a contrarian who hates new things and hates seeing something i don't understand get discussed constantly, i am going to just allow myself to pick some targets to be my punching bags. Better to yell at media than at my dad or at others, i suppose. Although knowing me, i could still end up yelling at my dad before the night's over. I'm not the most pleasant person. sigh...

Anyways, it's contrarian aggression time! My targets: stupid greek mythology musicals! Epic the musical and hadestown and anything that isn't Percy Jackson or Disney's Hercules, I'm going to be attacking you to release some aggression. I don't know why we need musicals about horribly depressing pieces of media made up by horrible people centuries ago, but get out of here! Screw you, Orpheus! Take your tragic harp and go hang yourself with it! Take it too, Odysseus! I can't understand your story because it's written in horrible ancient writing styles, so screw you!

Screw the Greek and Roman afterlife! Might actually be worse than the stupid Christian concept of heaven and hell, and i say that as someone who hates the abrahamic faiths! Screw the illiad, the Odyssey, the Aeneid, and all these other stupid ancient books! One ancient religious text is just as bad as another! It's incomprehensible nonsense, and most of the time it's so sad that I want to strangle the author for making me feel even more depressed than I usually do! Screw all of this nonsense! Burn it, bury it, start fresh with more optimistic myths! I said it! Mythology should be mostly hopeful, not tragic!

I hate tragedy! I hate horror! The only genre I really like is comedy, but heaven forbid we get any good clear, comprehensible ancient comedies! gods forbid! I hate it! And don't get me started on that idiot Shakespeare! If we switch from idiots like Homer and whoever the hell wrote the bible to shakespeare, then we'll be here for another five paragraphs. So I'm ending this here. But who knows? I might come back for Shakespeare later. I certainly hate him enough to do so.

#i wrote this because i was stressed#but i don't want to apologize for it currently#i'm a coward so i will if i'm mocked#but i don't want to!#stressed#stress#anger issues#anger#angry#contrarianism#contrarian#anti epic the musical#epic the musical critical#anti hadestown#hadestown critical#greek mythology critical#anti tragedies#asd#autism#neurodivergent#my thoughts#autistic#adhd#actually autistic#audhd#complaining#complaints#stress relief

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve seen several people who claim to be TG, when asked why they are TG, say it is because they have more “interesting” or “complex” characters. Do you think TG does have more interesting/complex characters? Also why does a character being more “interesting” or “complex” automatically mean they must support their whole ideology and what they fight for? Why can they not find a character interesting and yet still understand that said character is not a good, or even morally grey, character?

My Twitter post/thread abt it

My tumblr post HERE.

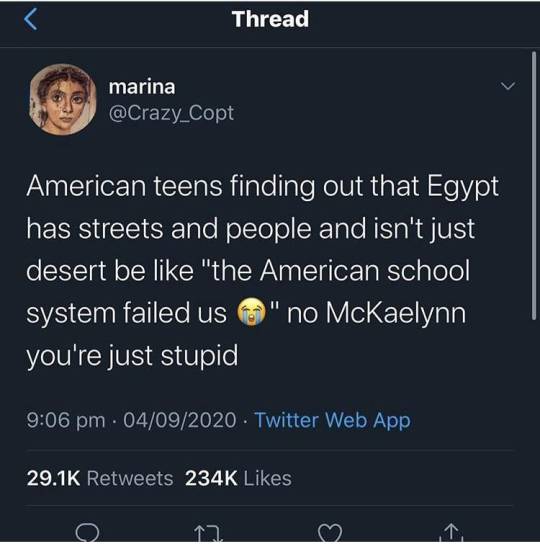

I'll add: it's a by-product of some status quo people thinking being contrarian--esp to "wokeness"--makes you somehow smarter, better, etc. bc you must be if you are to "beat" the "rising" challenge to said status quo.

#asoiaf asks to me#green stans#hotd fandom#the greens' characterization#the greens#hotd comment#house of the dragon#asoiaf#contrarianism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To do the opposite of something is also a form of imitation."

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, scientist and philosopher (1st July 1742-1799)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's so weird to me when people talk about how you should own games/movies/whatever in physical formats because the streaming service might shut down, because physical media is far more likely to get lost or destroyed. The average lifespan of a streaming platform is much longer than the average lifespan of a DVD!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

calm down debbie downers like what is with the pain porn misery obsession i think it's best if teams who haven't suffered win it LOL like fackkkkk legacy and meritocracy. keep it pushing... twitter bros are like they haven't suffered enough to deserve this joy etc but isn't it best if things are unpredictable enough to keep the sport interesting and not so plastered that orgs can be in comfortable positions... whatever!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

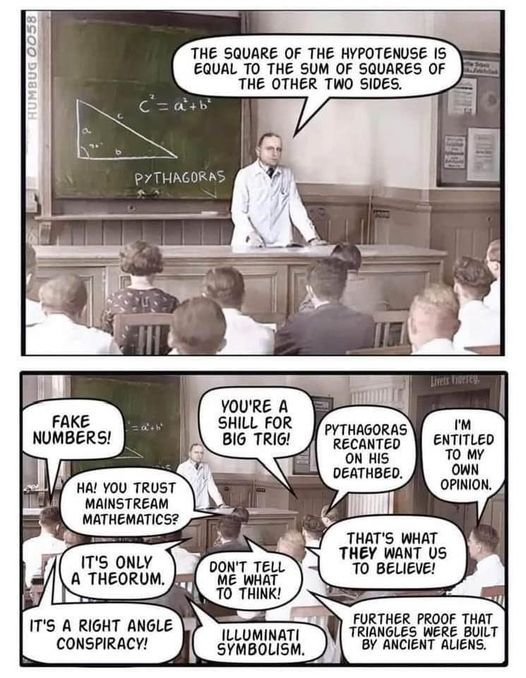

Teenage contrarianism, teenage contrarianism everywhere

110K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fighting my inner contrarian

I hold my own ideological camp to higher standards than the opposing one. The result is that to an uninformed observer, I look like a supporter of ideals opposite to what I actually believe in.

When I spot a logical or rhetorical flaw in an argument of someone I fundamentally agree with, I am quick to jump to criticizing them.

However when the same thing happens with someone I fundamentally disagree with, I feel less disappointed because I already expect their argument to be flawed. So I spend less effort on correcting them.

I am trying to shift to a more positive argumentative approach where I focus on stating things I believe to be true rather than correcting things I believe to be false. I have found that it leaves me with much less of a stomach ache afterwards.

0 notes

Text

see the problem with every person i've ever seen posting "i enjoy being a hater" in relation to things that are pretty much fundamentally innocent, like D&D actual plays or whatever, is that they're all incredibly boring people.

they have nothing interesting to say and their edgy contrarianism reminds me of people i've seen wearing shirts that say "i love dogs and maybe three people".

yeah, okay, you enjoy being a hater. you're also fucking boring and an easy person to dislike. you're as much a symbol of American individualism as all the carelords and sincerityposters who you consider beneath you, you dull, bitter fuck.

#personal#rant#contrarianism#individualism#cynicism#hater#complaining#real shit#annoying#relatable#opinion

1 note

·

View note

Text

For being 19, I hate modern music so much. Well, that's not fully true. There's some stuff that's fine. But i think i have a nasty contrarian streak, where seeing a name too many times and not knowing much about them makes me just get sick and tired of hearing about them. I am a mystery and an enigma, even to myself. But i think i have a very bad habit of complaining solely because i can't help wanting to be a contrarian.

#I saved that first sentence in my drafts weeks ago#but i only got around to making it a post now#asd#autism#neurodivergent#my thoughts#autistic#adhd#actually autistic#audhd#vent#venting#i confuse myself#i don't even understand myself#contrarianism#rambles#rambling#ramblings

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#couldnt find this in my archives so im posting it again#animal collective#it is strawberry jam btw altho i am a contrarian hipster virgen

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

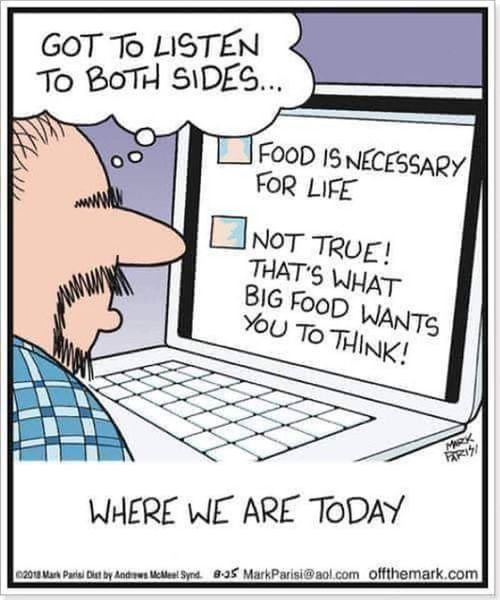

What I'm trying to give people the confidence to do, is to not only think that: even if you're the only one that thinks it, it could be true. But to imagine that actually: if the majority thinks one thing, it's more likely than not to be wrong.

Christopher Hitchens

1 note

·

View note