#contemporary philosophy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“Observe those around you, and you will see them wandering about, lost in their lives; they move like sleepwalkers in the midst of their good or evil fortune, without the faintest suspicion of what is happening to them. You will hear them speak in categorical formulas about themselves and their surroundings, which would suggest that they have ideas about all of it. But if you examine those ideas briefly, you will notice that they scarcely reflect reality, if at all, and if you delve further, you will find that they do not even aim to align with reality. Quite the opposite: the individual uses them to block their own vision of the real, of life itself.

For life, first and foremost, is chaos in which one is lost. The individual suspects this, but he is terrified to face that dreadful reality and tries to hide it with a phantasmagoric curtain where everything seems clear. He does not care that his ‘ideas’ are untrue; he uses them as trenches to defend himself from life, as scarecrows to ward off reality.

The man with the clear head is the one who frees himself from these phantasmagoric ‘ideas,’ looks life directly in the face, and realizes that everything in it is problematic, and feels lost. Since this is the pure truth—namely, that to live is to feel lost—he who accepts it has already begun to find himself; he has already started to uncover his authentic reality and is standing on solid ground. Instinctively, as do the shipwrecked, he will look around for something to which to cling, and that tragic, ruthless glance, absolutely sincere, because it is a question of his salvation, will cause him to bring order into the chaos of his life.

These are the only genuine ideas: the ideas of the shipwrecked. Everything else is rhetoric, posturing, and intimate farce. He who does not truly feel lost is inexorably lost—that is, he never finds himself, never encounters his own reality.”

Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#had to sacrifice sucking pigs and the tame animals#tumblr won't fucking let me get all the options there#philosophy#foucault#michel foucault#french philosophy#contemporary philosophy#postmodernism#postmodern philosophy#gender#judith butler#gender trouble#gender studies#categories#categorization#fuck sake tumblr ruins the italics for the et cetera which was way funnier

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

PhD Journal - 27 10 2024

I was reading this article on Aristotle's ideas on human and animal rational abilities, and some things the author wrote struck me.

He wrote "The world, however, looks very different to humans. Things can appear red or painful to an animal, but not noble or unjust", I simply think this is untrue in many ways.

The statement seems to dismiss the possibility that animals can perceive qualities beyond basic sensory or emotional experiences. While it’s true that human perception of concepts like nobility or justice is deeply tied to our social structures and language, it’s a bit presumptive to assume animals don’t have their own complex experiences or social behaviors that might parallel some of our more abstract ideas.

For example, certain animals exhibit behaviors that suggest a sense of fairness or altruism. Elephants have been observed mourning their dead, which could indicate some level of emotional complexity that goes beyond just pain or pleasure. Similarly, primates have shown behaviors that suggest a rudimentary sense of justice or fairness.

Dismissing these possibilities might be limiting our understanding of animal cognition and consciousness.

I think that we can't know what is going on truly in another's mind, whether it might be a human or an animal, an if we presume that other people have the same notion of what is just or unjust as we do, then why not presume animals also have that ability or that notion? It wouldn't be that much of a stretch either.

Indeed, assuming we can know with certainty what is going on in another's mind—whether human or animal—is a profound leap. My understanding about assuming that other people share our notions of justice and injustice opens up a fascinating angle: if we grant this assumption to humans, it’s a small step to extend it to animals as well.

Different cultures and individuals can have varied perceptions of justice, shaped by their experiences, social structures, and personal beliefs. Similarly, animals, with their own social structures and behaviors, may possess their own notions of fairness or injustice that we simply don't fully understand yet. Observations of animals showing empathy, cooperation, and even mourning behavior hint at complexities in their social interactions and emotions that may parallel human experiences in some way.

Moreover, Aristotle’s idea that humans are “social/political animals” highlights our inherent need for community and governance, but it also suggests that social structures aren't unique to humans. Many animals exhibit social and political behaviors within their groups. Take wolves, for example—they have complex social hierarchies and cooperation mechanisms. Elephants demonstrate empathy and mourning, which indicate an awareness of right and wrong within their social context.

Assuming that humans, as animals, are the only ones capable of moral reasoning ignores the nuanced behaviors of other species. The same principles that govern human social and ethical behavior can often be observed in the animal kingdom, albeit in different forms. So, it's quite reasonable to propose that animals might have their own versions of what is morally right or wrong based on their social structures and interactions.

Recognizing that animals might have their own notions of right and wrong, based on their social behaviors, encourages us to approach them with greater empathy and respect. It challenges us to rethink our interactions with all creatures, fostering a sense of shared existence.

Greater consideration for animals and insects can lead to more compassionate and protective actions on our part. This might mean advocating for their habitats, reducing our ecological footprint, and ensuring that our advancements do not come at the expense of their well-being. Embracing this perspective not only enriches our ethical frameworks but also enhances the way we coexist with the natural world.

Further along in this article, the author wrote "This story commits Aristotle to the claim that non-human animals are incapable of restraint. Nothing we have said so far suggests a view about animal cognition without restraint. One possibility is that, without restraint, the perceptual/imaginative stream has no effect on behavior, as a car's engine does not power its wheels when the car is stuck in neutral. But that account seems absurd, since animals get around just fine without rational cognition and therefore without restraint". Which, I still find myself conflicting with. I would argue that animals have some imagination, some phantasia in the aristotelian sense, like, say, squirells who imagine a hard winter and pile up, or bears who eat a lot before hibernating in preparation, having had phantasmata, of a hard winter.

I would think this personal interpretation aligns with a nuanced understanding of Aristotle. Aristotle did acknowledge that animals possess phantasia (imagination), which allows them to perceive and respond to their environment in complex ways. This phantasia involves the ability to form images or representations of things not immediately present, influencing behavior.

When Aristotle discusses animals and restraint, he distinguishes between rational restraint (unique to humans) and non-rational restraint. Humans use rational deliberation to exercise restraint, while animals rely on a form of non-rational restraint guided by phantasia.

Examples like squirrels hoarding nuts or bears preparing for hibernation illustrate that animals anticipate future needs based on imagined scenarios (phantasmata). This anticipation shapes their behavior, indicating that animals do have a form of cognitive processing that impacts their actions, albeit different from human rationality.

However, while it's traditionally thought that animals operate on instinct and phantasia rather than rational planning, recent studies suggest that some animals do engage in what appears to be foresight and planning. Squirrels caching nuts and bears preparing for hibernation might indeed involve more complex decision-making processes. These behaviors could indicate a form of non-human rationality, shaped by environmental cues and learned experiences. It’s a fascinating area where philosophy and ethology intersect, challenging our understanding of cognition across species.

The idea that animals may exhibit a form of rational behavior—distinct from human rationality—opens up fascinating possibilities. It challenges us to consider cognition on a broader spectrum, recognizing that animals might plan and make decisions in ways we don’t fully understand.

By acknowledging our limitations as humans in comprehending animal cognition, we invite a more nuanced appreciation of their capabilities. This perspective underscores the importance of approaching animal behavior with humility and curiosity.

Later, the writer stated : "he comparison to animals is still explicit: appearances cause movement in humans against their better judgment, in animals because they have no better judgment". Still, I find it difficult to agree with such a statement. For, from my experience and understanding, we see animals hesitate, like humans, out of doubt, out of fear, because they, like us, don't have enough information to be sure of their movements.

Observing animal behavior often reveals moments of hesitation, suggesting a level of decision-making complexity akin to human doubt and uncertainty. Animals, like humans, can exhibit caution and deliberation when faced with unclear situations, indicating that they do possess forms of judgment that guide their actions.

This implies that animals’ responses aren't merely automatic reactions to stimuli but involve a form of assessment based on available information. Thus, dismissing their actions as lacking "better judgment" underestimates their cognitive abilities.

The author continues, stating that "When Aristotle claims that animals acquire experience (empeiria), I think he means to tell this kind of story. He makes that claim in the opening chapter of the Metaphysics, in yet another comparison between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom. Humans have craft (technê) and reasoning (logismos) to help them get by, while beasts do not. Beasts live by their imagination, memory and apparently a small share of experience: But anyway, the other [animals] live by imaginings and memories, and have a small share of experience (empeiria), but humankind [lives] also by craft and reasoning". I still find myself disagreeing with this.

Indeed, I'd argue we should challenge such an interpretation. Bees producing honey, birds communicating through song, and animals using strategies to overcome obstacles all suggest a level of technê (craft) and practical reasoning in animals. Aristotle's distinctions might reflect the perspectives of his time, but contemporary ethology shows that animals possess complex skills, problem-solving abilities, and social behaviors that go beyond mere imagination and memory.

Bees, for instance, exhibit sophisticated behaviors in honey production, which involves communication through the waggle dance and precise construction skills. Birds, like parrots, use vocalizations that serve meaningful social functions, similar to human language. Many animals demonstrate problem-solving skills and the ability to devise and execute plans, reflecting a form of reasoning.

I would, in the end, perhaps argue that we should ackowledge modern perspectives, which might highlight the evolution of thought and encourage readers to reflect on how our understanding has progressed. It’s a way to show the growth of knowledge and the necessity of questioning and adapting ancient ideas to contemporary insights. Because, not acknowledging modern perspectives on animal cognition could indeed limit the relevance and adaptability of Aristotle's thoughts today. To truly honor the evolution of knowledge, it's essential to integrate current understandings while recognizing the historical significance of past thinkers.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haraway, 1985

Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg is a radical archetype for emancipatory self-construction that models conscious reshaping of socially imposed identities. The cyborg represents the plasticity of our socially constructed identities: our ability to transcend the limits of prefabricated identities and overwrite oppressive, socially imposed roles. Understanding social construction through this lens gives social workers and clients the conceptual tools to deconstruct rigid identities—particularly those of gender identity—imposed by society. These identities are the subject of active political contestation; they are the product of economic, social, and cultural relations and institutions. The concept of the cyborg provides an emancipatory model that denaturalizes and destabilizes rigid essentialist binaries and instead recognizes the chimeric multiplicity of the individual.

Abstract by Nicholas D. Tolliver, 2022

https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/mar4-1k48

We are all cyborgs: How machines can be a feminist tool

By Nour Ahmad

Upon hearing the word “cyborg”, perhaps the first thing that comes to mind is a fusion of human and machine. Our imagination might even drift to an image of Frankenstein’s monster or a depiction such as Major Mira Killian in the anime Ghost in the Shell. A cyborg is actually just a hybrid — part mechanism, part organism. The cyborg, as a concept, is associated with scientist, innovator and musician Manfred Clynes, who deployed it in his 1960’s article Cyborgs and Space, where he argued for altering the human body to make it suitable for space travel.

We, thus, might perceive this concept as being in the future, far from the here and now. However, Donna Haraway, an American biologist and feminist, claims the opposite. She believes that we are all already cyborgs. More significantly, she posits that the advent of cybernetics might help in the construction of a world capable of challenging gender disparities, a proposal she made in her 1985’s essay titled A Cyborg Manifesto.

How, then, would the notion of cybernetics make for a post-gender understanding of the world? And how would it be a tool for women to undermine the roles imposed on them by society?

Cyborgs and human nature

The investigation into human nature has always been an essential pursuit for schools of philosophy and a basic assumption made by political ideologies. The answer to the question “what does it mean to be a human?” determines the orientation of a political movement or an ideology. Patriarchal societies have historically adopted an essentialist interpretation of human nature, so as to justify male domination over women. It makes the claim that each of the sexes has a specific role to play and, ultimately, considers the feminine to be secondary to the masculine and thus subjugates women. In such societies, predetermined sets of values and behavioural patterns are strictly enforced on both sexes.

In A Cyborg Manifesto, Haraway explores the history of the relationship between humans and machines, and she argues that three boundaries were broken throughout human history which have changed the definition of what is deemed cultural or otherwise natural. The first such boundary was between humans and animals, and was broken in the 19th century after the publishing of On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin. As the biological connection between all organisms was discovered and publicised in this book, it served as a rejection of notions of human exceptionalism and superiority, turning the evolution of the organism into a puzzle. It also introduced the concept of evolution as necessary for understanding the meaning of human existence.

The second boundary-breaking event relates to the relationship between machines and organisms (be they human or animal). As the industrial revolution arrived, all aspects of human life became mechanised. As human dependence on machines surged, machines became an inseparable part of what it is to be human; an extension of human capability.

As for the third boundary, it concerns the technological advancement that has produced evermore complex machines which can be miniscule in size or, in the case of software, altogether invisible. First came developments in silicon semi-conductor chips that now pervade all of life’s domains. As these machines are practically invisible, it is then difficult to decide where the machine ends and humans start. This machine thus represents culture intruding over nature, intertwining with it and changing it in the process. As a result, boundaries between the cultural and the natural became more and more intangible.

“…the advent of cybernetics might help in the construction of a world capable of challenging gender disparities.”

In this context, Haraway uses the cyborg as a model to present her vision of a world that transcends sexual differences, expressing her rejection of patriarchal ideas based on such differences. Because a cyborg is a hybrid of the machine and the organism, it merges nature and culture into one body, blurring the lines between them and eliminating the validity of essentialist understandings of human nature. This includes claims that there are specific social roles reserved for each of the sexes which are based in biological differences between them, in addition to other differences such as age or race.

You are cyborg!

Since first practicing agriculture, using tools to increase production and developing language and writing, humans have been able to boost capabilities and expand their potential. Today, the implantation of artificial organs has been a vital development in the field of medicine, while the smartphone, for example, serves as an extension of human memory, our senses and our mental functions as well. The advancements made in GPS and communication technologies allow us to be present remotely and even grant us the ability to exist outside of the limitations of our time and space frameworks. All these aspects of technology are an expansion of human beings and an augmentation of our physical and cognitive abilities.

Taking all of this into consideration, the cyborg seems present here and now. In an interview with Wired magazine, Haraway said that being a cyborg does not necessarily mean having silicon chips implanted under one’s skin or mechanical parts added to one’s body. The implication is, rather, that the human body has acquired features that it could not have been able to develop on its own, such as extending life expectancy. Indeed, in our current state, cybernetics exist around us, and in simpler forms than futuristic visions. Even maintaining our physical fitness is today cybernetic, from the use of exercise machines to the many food supplements available as well as clothing and footwear engineered for athletic activity. Moreover, the culture surrounding fitness could not have existed without viewing the human body as a high-performance machine whose performance can be improved over time.

On the other hand, a cyborg is “a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” according to Haraway’s manifesto. The internet has brought about profound changes in human consciousness and human psychology. Virtual reality does not only surround us, but it also involves us in its own processes. The social dimension to technology plays a role in the construction of our identities, whether through online games, discussion forums or social media, where our identities can be as multiple as the online platforms that we use.

Therefore, we can now say that we are all cyborgs, as technology “is not neutral. We’re inside of what we make, and it’s inside of us,” as Haraway formulates it. In modern life, the link between humans and technology has become inexorable to the extent that we cannot tell where we end and the machines begin.

Cybernetics and feminism

Feminist issues lie at the heart of the concept of cybernetics, since the latter’s prospects erase major contradictions between nature and culture, such that it is no longer possible to characterise a role as natural. When people colloquially use the word “natural” to describe something, this is an expression of how they view the world, but also a normative claim about how it should be as well as a statement on what cannot be changed.

In this context, the cybernetics erase gender boundaries. For generations, women have been told that their “nature” makes them weak, submissive, overemotional and incapable of abstract thought, that it was “in their nature” only to be mothers and wives. If all these roles are “natural” then they are unchangeable, Haraway said.

Conversely, if the concept of the human is itself “unnatural” and is instead socially constructed, then both men and women are also social constructs, and nothing about them is inherently “natural” or absolute. We are all [re]constructed when given the right tools. In short, cybernetics have allowed a new distinction of roles, based on neither sex nor race, as it provided humans the liberty and agency to construct themselves on every level.

“Because a cyborg is a hybrid of the machine and the organism, it merges nature and culture into one body, blurring the lines between them and eliminating the validity of essentialist understandings of human nature. This includes claims that there are specific social roles reserved for each of the sexes which are based in biological differences between them, in addition to other differences such as age or race.”

Therefore, through her notion of the cyborg, Haraway calls for a new feminism that takes into account the fundamental changes that technology brings to our bodies, to reject the binaries that represent the epistemology of the patriarchy —binaries such as body/psyche, matter/spirit, emotion/mind, natural/artificial, male/female, self/other, nature/culture. Technology is simply one of the means by which the boundaries between identities are erased. Cyborgs, in addition to being hybrids, transcend gender binaries and can thus constitute a way out of binary thinking used to classify our bodies and our machines and accordingly “lead to openness and encourage pluralism and indefiniteness.”

Haraway’s idea is based on a full cognisance of the ability of technology to increase the scope of human limitation and thus open opportunities for individuals to construct themselves away from stereotypes. And while Haraway describes A Cyborg Manifesto as an ironic political myth that mocks and derides patriarchal society, she still claims that cybernetics lay the foundation for a society in which we establish our relations not on the basis of similarity, but on harmony and accord.

(mediasupport.org)

#donna haraway#contemporary philosophy#american philosophy#queer theory#feminist philosophy#politics resource#politics texts#philosophy resource#philosophy texts#80s#90s#2000s#2010s#a cyborg manifesto#american writing

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no democracy in any love relation: only mercy.

Gillian Rose

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

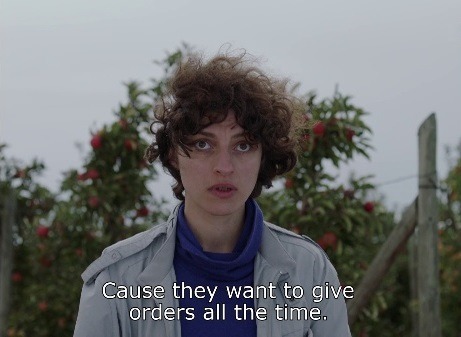

Selbstkritik eines bürgerlichen Hundes [Self-Criticism of a Bourgeois Dog] (Julian Radlmaier - 2017)

#Selbstkritik eines bürgerlichen Hundes#communism#power#Self-Criticism of a Bourgeois Dog#anarchism#anarchists#Johanna Orsini-Rosenberg#Johanna Orsini-Rosen#women#philosophy of history#Deragh Campbell#Julian Radlmaier#contemporary philosophy#Zurab Rtveliasvili#Ilia Korkashvili#pursuit of happiness#Kyung-Taek Lie#Berlin#Deutschland#Anton Gonopolski#Bruno Derksen#Germany#2010s movies#European society#political comedy#self deception#progress#proletarians#thoughts#freedom

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

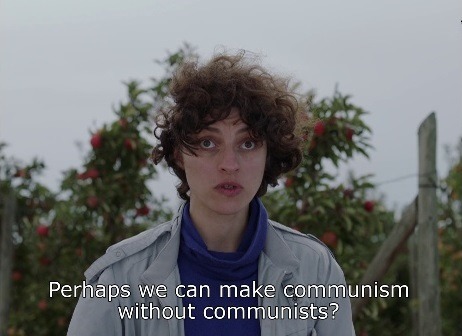

René Girard - Il Capro Espiatorio

#french literature#philosophy#rene girard#philosopher#modern philosophy#contemporary literature#contemporary philosophy#french language#french translation#italian literature#italian#italiano#history#literature#quotes#uni student#histoire#the lovers#protest#protesta#dissension#music#art#ancient literature#ancient history#latin literature#love#passion#university#current mood

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#I dont know why i did this#but there you go#descartes#merleau-ponty#my undergrad thesis#barbie#barbie 2023#philosophy#modern philosophy#contemporary philosophy#mind body dualism#mind body dualist#ontology of the flesh#Meditations on first philosophy#the visible and the invisible#eye and mind#contemporary aesthetics

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi! Teddie here.

In December, 2022, Oliver Misraje published this article in Zine, “The Internet is a Graveyard”. Misraje talks about four case studies in which ghosts have infiltrated the online realm – from AI "reviving" lost loved ones, to immortal memorialization on the internet, the freelance writer reveals the less-than-lively aspects of our generated world. As a philosophy fanatic, the thing that spoke out most to me in this article was Misraje’s final case study, labelled “Future Ghosts”.

Briefly, in the history of philosophy there has been endless back and forth regarding the immortality of the human soul or mind. Essentially, whether or not we exist after we die. And the implications of this reach all the way back to Plato, who claimed that death should be the philosopher’s ultimate goal, so we can more or less finally free our minds from the physical world and become omnipotent/transcendent beings.

But as someone who does consider life a wholly unique and miraculous experience, this cheap acceptance of death does not come easy, and I feel a need to believe that there is something more to the mortal world that we are missing. I think a lot of people would agree with me there.

Misraje explains, in the fourth case study of the article, an old event in 1994 where “techno-pagans” reframed the internet as more than a realm for enhanced globalization and human connection – where the internet becomes a hub for a kind of “magical evocation”. Misraje also connects this to the more recent paper by Melanie Swan, in which she coins the term “cloudminds”: a form of transhumanism (the idea that humans can evolve beyond our bodies and minds), where we have some processing power that is entirely virtual (think crypto-currency, but instead of having monetary value it makes decisions for us). We would be able to upload our minds (our experiences, memories, decisions) to an online database where our own individual knowledge and histories could connect and collectively be used in a kind of uni-mind (credit to Marvel), which could be used to solve much more difficult, large-scale human problems. Apart from completely eradicating the importance of human engineers, though, what does this mean for the rest of us? What might that tell us about life and death?

I’d love to take this in a non-conventional direction, so bear with me. Let’s pretend that the afterlife does not matter, whatsoever. It doesn’t exist, it doesn’t get experienced, it doesn’t affect anyone living or anyone dead. Imagine it as a junk drawer, or a trash bin: out of sight, out of mind. Now, we introduce this cloudmind: instead of our knowledge being carried with us into the trash, we keep a record of all of it, every experience and memory and thought. Everything except our physical bodies and brains would remain in our mortal world, where it could forever be interacted with and investigated. The living can interact with every intangible quality of the dead. Is this what it looks like to achieve immortality?

Short answer: No. Even if we could capture every essence of one person on some sort of virtual hard drive, if we could upload it into a computer so we could “ChatGPT” it, or if we could plug it into some sort of rain-proof, life-sized sex doll, this is not immortality. The essence (for lack of better term) of this being would be trapped in this state of simultaneous existence and non-existence, where it no longer feels or senses the way a human does, it doesn’t interact with its environment or manipulate the objects in its life the way a human does. Regardless of if it ever gains its own consciousness, it’s the same thing as taking a human mind and soul and welding it to a rock instead of a body – think of “Everything, Everywhere, All At Once”.

So, yes, Plato might be proud – we found a way to potentially transcend, to tether a part of human consciousness to an immortal virtual world. But if our consciousness is primarily connected to our human experiences, perceptions, and memories, would you want to be rock? A computer? A ChatGPT?

#teddie speaks the truth#social dilemma#immortality#mortality#marvel#eternals#everything everywhere all at once#future ghosts#CyberSamhein#cloudmind#ChatGPT#contemporary philosophy#hauntology#realm of forms#meatverse#meat world

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

We aspire by doing things, and the things we do change us so that we are able to do the same things, or things of that kind, better and better. In the beginning, we sometimes feel as though we are pretending, play-acting, or otherwise alienated from our own activity. We may see the new value as something we are trying out or trying on rather than something we are fully engaged with and committed to. We may rely heavily on mentors whom we are trying to imitate or competitors whom we are trying to best. As time goes on, however, the fact (if it is a fact) that we are still at it is usually a sign that we find ourselves progressively more able to see, on our own, the value that we could barely apprehend at first. This is how we work our way into caring about the many things that we, having done that work, care about.

agnes callard, aspiration: the agency of becoming

still a little upset tbqh that everyone was dunking on agnes callard in march, after that one new yorker article…i don’t care what she’s done in her (entirely consensual and imo ethically permissible) first and second marriages…her work has changed my life and that is something to honour in a contemporary academic philosopher.

aspiration is what taught me to not be afraid of trying to become someone new. to not be embarrassed of aspiring towards something before having attained it. to see my self-conscious striving towards a different self as something admirable about me, worth cherishing instead of criticising.

#agnes callard#quotes#contemporary philosophy#what does it mean to live an existentially meaningful life?#quotes on writing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer, cover design by Gray318, published 2009.

#eating animals#jonathan safran foer#gray318#contemporary philosophy#environmentalism#conscientious diets

1 note

·

View note

Text

PhD Journal - 09 11 2024

The paradox of Libet’s experiment : the proof of free will

How do we prove we have free will, as fully conscious agents? This question has puzzled philosophers, neuroscientists, and thinkers for centuries. The concept of free will—the ability to make choices independent of external determinants—sits at the heart of our understanding of human agency and responsibility. In this article, we will explore the intersection of philosophical ideas and scientific experiments, focusing on the groundbreaking work of Benjamin Libet and its implications for our understanding of free will.

We find that there is quite a lot of philosophical foundation to ground and think about the concept of free will. Philosophers like Descartes, Kant, and Sartre have grappled with the notion of free will. Descartes emphasized the importance of human consciousness and rationality, while Kant argued for the autonomy of moral agents. Sartre, on the other hand, posited that humans are condemned to be free, bearing the weight of complete responsibility for their actions. These philosophical perspectives provide a rich backdrop for our inquiry into the nature of free will. Within this thought process exists the debate of compatibilism versus incompatibilism. The debate between compatibilists and incompatibilists further complicates our understanding of free will. Compatibilists argue that free will can coexist with determinism, suggesting that our choices, while influenced by prior states and events, still allow for meaningful autonomy. Incompatibilists, however, contend that true free will is incompatible with determinism, asserting that for our choices to be genuinely free, they must not be determined by preceding events.

In the ongoing debate about free will, I align myself with the philosophy of compatibilism. This perspective recognizes that while our actions are undoubtedly influenced by a multitude of factors—such as our historical, social, economic, psychological, emotional, and academic backgrounds—we still possess the ability to make conscious decisions. Compatibilism allows for a nuanced understanding of human behavior, where individuals are seen as agents capable of acting according to their preferences, belief systems, and personal knowledge. It acknowledges that we can choose to act through or against our biases, driven by our will to navigate the complex interplay of influences that shape our lives.

In the 1980s, neuroscientist Benjamin Libet conducted experiments to investigate the timing of conscious intention and brain activity. Participants were asked to move their fingers at a time of their choosing while Libet measured the brain's readiness potential, an electrical signal indicating the brain's preparation for movement. Libet conducted experiments showing that brain activity related to movement (the readiness potential) occurs before the conscious intention to move. This suggests that the brain initiates actions before we are consciously aware of deciding to perform them. Participants in his experiments reported that they felt free to move whenever they wished and were not compelled to act. This introspective feeling of free will was a crucial part of his experimental design and interpretation. If participants had felt compelled to move, it would have undermined the validity of the experiments, as the subjective experience of free will was essential to Libet's conclusions. The experiments sought to demonstrate that the conscious decision to act follows the brain's initiation of that action, rather than being the instigator. Libet also proposed the concept of "veto power," suggesting that while the initiation of actions might be unconscious, the conscious mind has the ability to veto or inhibit these actions. This idea adds another layer to the debate about free will and conscious intention.

In Libet's studies, participants were indeed required to be willing and cooperative, meaning they needed to perform the task as instructed, which involved moving their finger at a time of their choosing. This cooperation ensured that the data collected was relevant to the question Libet was investigating: the timing of conscious intention relative to the brain's readiness potential. If participants were uncooperative or deliberately chose not to move, it would have skewed the results and made it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions about the relationship between brain activity and conscious intention. Cooperative participants who chose to move were essential for Libet to observe and measure the precise timing of brain activity and conscious intention. This helped to substantiate his theory that the brain initiates actions before we become consciously aware of deciding to perform them.

In the context of Libet's experiments, if participants didn't feel compelled to move their finger "at will" and chose not to move, it could indeed be interpreted as evidence of free will. This refusal to act would suggest that participants have the conscious ability to veto or inhibit a movement initiated by unconscious brain activity. Libet himself proposed the concept of "free won't," the idea that while the brain might initiate an action unconsciously, the conscious mind can still choose to stop it. This implies that the conscious mind has a sort of veto power over the actions initiated by the brain, allowing for a form of free will to be exercised in deciding whether or not to complete the action. The concept of "free won't," or the ability to consciously veto an action initiated by unconscious brain activity, supports the idea that we do have some level of control and agency over our actions. This nuanced understanding indicates that while our decisions may be influenced by unconscious processes, we still possess the capacity to exercise conscious choice and control.

Libet's experiments, which reveal that the brain initiates actions before conscious intention, pose an intriguing challenge to traditional notions of free will. However, from a compatibilist perspective, these findings do not negate the existence of free will. Instead, they highlight the intricate relationship between unconscious brain processes and conscious decision-making. The concept of "free won't," where individuals retain the power to veto or inhibit actions initiated by the brain, aligns well with compatibilism. This nuanced understanding supports the idea that while unconscious processes may influence our actions, we retain the capacity for conscious control and intentionality.

Libet's experiments present a unique paradox when it comes to proving the existence of free will. On the one hand, the experiments show that the brain's readiness potential—an unconscious signal—precedes the conscious intention to move. This finding challenges the traditional notion of free will, suggesting that our actions may be initiated by unconscious processes before we become aware of them. However, the concept of "free won't" adds a layer of complexity to this paradox. Libet proposed that while the brain may initiate actions unconsciously, individuals have the conscious ability to veto or inhibit these actions. This idea suggests that we do possess a form of free will, even if it's not in the way we traditionally understand it.

The paradox posed by Libet’s experiment stands as such: On the one hand, there is proof of free will through our actions. Indeed, if participants move their finger, the readiness potential precedes the conscious decision, which seems to argue against traditional free will. On the other hand, there is also proof of free will through our inaction. Because, if participants choose not to move, their conscious veto demonstrates an exercise of free will. This paradoxical nature of Libet's findings highlights the complexity of studying free will. It suggests that free will may not be about the initiation of actions but rather about the conscious ability to control and inhibit those actions. This perspective aligns with compatibilism, which posits that free will can coexist with deterministic processes.

By examining both the movement and non-movement of participants, we see that free will might exist in the nuanced interplay between unconscious brain activity and conscious control. This understanding encourages us to rethink the nature of free will, moving beyond binary notions of free vs. determined actions.

In embracing compatibilism, we acknowledge the complexity of human agency. By integrating the insights from Libet's experiments with philosophical perspectives on free will, we gain a richer understanding of the interplay between unconscious influences and conscious choices. The paradox in Libet's experiments does not provide a straightforward answer to the question of free will. Instead, it invites us to embrace the complexity of human consciousness and agency. It challenges us to consider that free will might be more about our ability to consciously influence and control our actions rather than solely about initiating them. This approach not only deepens our understanding of free will but also affirms the profound capacity for human autonomy and responsibility.

#contemporary philosophy#philosophy#philosophie#my writing#neurology#neuroscience#Libet's experiment#compatibilism#free will#phdjourney#phdjournal#phdblr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haraway, 2016

In the midst of spiraling ecological devastation, multispecies feminist theorist Donna J. Haraway offers provocative new ways to reconfigure our relations to the earth and all its inhabitants. She eschews referring to our current epoch as the Anthropocene, preferring to conceptualize it as what she calls the Chthulucene, as it more aptly and fully describes our epoch as one in which the human and nonhuman are inextricably linked in tentacular practices. The Chthulucene, Haraway explains, requires sym-poiesis, or making-with, rather than auto-poiesis, or self-making. Learning to stay with the trouble of living and dying together on a damaged earth will prove more conducive to the kind of thinking that would provide the means to building more livable futures. Theoretically and methodologically driven by the signifier SF—string figures, science fact, science fiction, speculative feminism, speculative fabulation, so far—Staying with the Trouble further cements Haraway's reputation as one of the most daring and original thinkers of our time.

dukeupress.edu

#donna haraway#contemporary philosophy#american philosophy#queer theory#feminist philosophy#politics resource#politics texts#philosophy resource#philosophy texts#80s#90s#2000s#2010s#staying with the trouble

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝙌𝙪𝙤𝙩𝙖𝙗𝙡𝙚 𝙌𝙪𝙤𝙩𝙚𝙨.

❝seem at times, we have to accept that some people can only be in our hearts, not in our lives.❞

— Juan Francisco Palencia.

#writers on tumblr#attempt at poetic action#juan francisco palencia#spilled ink#writing#reflexions of my life#feelings#words from the bottom of the heart#from mexico to the universe#spring 2024#love quote of the day#light academia#love poem#impressions#quotable quotes#life philosophy#contemporary philosophy portal#vitruvio#writers and poets#writer tumblr#literary aesthetic#friendship#love#sad truth

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

love (loath) this version of ‘empathy’ for characters that exists in fandoms that somehow means taking any articulation of the fact that x character is given responsibility and context by the story and that their poor choices lead to poor outcomes is actually a slight against the character (and implicitly somehow whatever oppressed group which they belong to or are alleged to belong to by sections of fandom)

to be clear this is something i’ve noticed in several fandoms which is why the beginning of this is general language but the pertinent example to my current frustration is liliana temult and the defence of her that lays on a claim that those who enjoy the narrative showing her poor actions leading to poor outcomes for her have somehow failed the empathy test is beyond incomprehensible to me. like even ignoring the very basic level understanding that fiction is a place to experience satisfaction in narratives that we cannot fulfil in non-narrative reality, it’s also like… holy fuck do I not want the kind of empathy that tells me it will all work out no matter what choice I make. it is actually imperative to human life that the choices we make have substance in the outcomes we arrive in, otherwise we would’ve long given up on the notion of free will. and to look at a narrative, particularly one built in the context of a ttrpg. a game notably influenced by the choices that players-as-characters make. and then see sections of an audience find it compelling and enjoyable that a character who has made categorically poor choices that have caused immeasurable harm to others is now dealing with the very obvious face-eating panthers consequences… idk man. if you see that as a lack of empathy i implore you to consider what role empathy is playing in your world.

like. if empathy to you is about comfort and stagnancy and not about growth and community, then sure i can understand how it might not be empathetic in your view to notice patterns and see their obvious outcome and acknowledge that . but as someone who has been in the position of making horrible choices with obvious outcomes, far more essential to my personhood was those who looked at me with careful but critical eyes than those who nearly babyed me into my grave. that’s actually why i love imogen’s choice to insist that liliana make her own choice and then quasi-encouraging her to stay, because it was a clear reminded to liliana that her choices have consequences, and one of those is that the terrible things she’s down in the name of her daughter have led to that daughter not being able to easily trust her.

and i think another thing that’s related that gets misconstrued with liliana (and as always unfortunately many such cases) is that the satisfaction of seeing her absorbed isn’t that it’s retributive harm done or some sort of punishment (at least not for me, skill issue if people in your fandom spaces are that cop-minded but, yknow, what can you expect from the thought-crimes capital of fandom spaces). the satisfaction is in the analogue (that i’ve seen well memed) to the face-eating panthers joke that liliana’s actions which have pushed an agenda that’s depended on the consumption and threat to her child and the children she specifically has aided in placing in danger via her choices, has led to situations where a) she’s ‘burdened’ by her care for imogen and the children (both of which she has played a hand in inviting into the context of danger) b) she is now the person in danger of being consumed after spending weeks simply shrugging off concerns about what might be consumed in the name of ludinus’ Just World™. like it’s not just ‘liliana does bad things, must be punished’ it’s ‘liliana has played a hand in creating a situation that is threatening to many including herself, it is narratively satisfying and engages in Common Narrative Tool: Irony to have that create situation negatively impact her directly.’

to that end that’s why the ‘if you’re like this about liliana you should also be like this about essek’ takes are beyond missing the point (without getting into the horribly built scarecrow that it is, understand that it’s actually undermining decades of feminist’s philosophical and political development to see a critique of a female character and go ‘well actually if she were a man you wouldn’t be saying that’ when it’s a provable fact that people Would be (and have been) saying that if she were a man. so not the feminist slay you think it is). like, as someone who Was just as interested in essek’s story having consequences as I am in liliana’s, there very much WERE consequences for essek that, just like liliana, were well contextualized and suited to the specific choices he made. they are ones that should be obvious even to the most surface read of the campaigns given that essek still appears in disguise years after the end of c2, should also probably be obvious in the rebuilding of relationships essek had to do with mn after they discovered his betrayal. like the notable difference between liliana and essek is not their gender, it’s that we’ve seen the end of essek’s story (in the sense of like. campaign containment, obviously his Story™ is ongoing) and have yet to see liliana’s— it’s entirely possible that liliana does get saved and goes on to repair her relationship with imogen (or goes on and is unable to repair it) or she just dies and part of imogen’s story is dealing with it; all of those are narratively satisfying. what wouldn’t have been satisfying, in the sense that would leave liliana feeling like a non-agent in a story dependent on her agency, is if her role was entirely dictated by imogen’s interest in reconciliation. because sure if you want to look very microscopically the current threat to liliana that exists is 1-to-1 caused by the fact that she’s been helping imogen, but taking seriously the story, the consequences bloom from all the choices that liliana has made leading to ludinus’ decision to trust her however far he does that made liliana’s choice a betrayal and affirmed ludinus’ strength and position so that he can do something like siphon someone’s life force away.

further the ‘why does liliana deserve to be funnelled and relvin gets off easy’ relvin doesn’t get off easy. once again the satisfaction of his narrative is that he did his best and it was insufficient and that cost him a relationship with imogen they both clearly wish for but neither can rectify. the consequence for relvin is that he’s in an empty house that is no longer home to the woman he loved or the daughter he was left to raise alone. surely i don’t need to unpack why i think someone who tried but wasn’t well equipped to raise a daughter with superpowers doesn’t need to evoke as ‘drastic’ consequences in their story as the stated right hand of the campaign’s bbeg for their story to feel complete.

and idk at least for me that’s the salient point; that the consequences that are happening feel like a plausible and suitable conclusion to the story we’ve seen of liliana even if she perishes at ludinus’ hand. it will be sad but it’ll be satisfying, and maybe i should have realized seeing the frequency with which parts of fandom have been campaigning to undo maybe the most weighty and narratively satisfying choices & consequence of vox machina’s story, but it’s truly confounding to me the amount of people treating the presence of any complex and non-traditional happy ending notion in a story set in a world defined by pyrrhic victories. like, empathy for vax isn’t saying he’s the puppet of a god that manipulated him into service, it’s acknowledging that he made a choice that he knew would have consequences and acknowledging that the consequences he demanded with that choice were pretty severe ones. that doesn’t mean i’m watching the end of cr1 seeing the characters destroyed by the loss of vax being like ‘dumbasses, they knew this was coming, vax chose this, these are his consequences’ it means that when i’m crying watching the end of cr1 it’s paired with my deep love for a story that takes seriously the weight of the character’s choices in the determination of their lives. idk man. maybe interrogate how much of your notion of empathy is dependent on individualism to the point of near complete alienation and get back to me on how empathetic it is to look at someone who has caused unarguable pain with their choices and say ‘no no it’s fine you didn’t mean to + you’re a woman :/‘ while the victims of those choices rot in their graves

#not to make fiction about real life but CURIOUS what so called liliana defenders have to say about alcoholics who drunk drive#critical role#cr fandom#on fandom#liliana temult#worst part of this is that i actually am a liliana lover she’s an incredibly interesting character to me#but. i see a post about her it’s like a 70% chance it’s just turning her into a agencyless zombie or otohans girlfriend (so a different kind#of agencyless zombie) like. can we engage in the story.#i bring a philosophy student who hates choice feminism vibe to discussions that contemporary fandom really doesn’t like#cr3

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

" Shitty Philosophy "

Acrylic painting on Canvas.

Size 23 x 30 cm.

#Shitty Philosophy#vaxo lang#vaxolang#vaxo art#creepy art#contemporary art#contemporary artist#acrylic painting#creepy#dark art#macabre artist#macabre art#astethic#horror#horror art

139 notes

·

View notes