#classical exempla

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hiii, I hope you're well.

As far as I understand, the idea/debate of whether Alexander and Hephaistion were lovers goes back centuries. As far as I know, it was the roman writer Klaudios Ailianos in 'Miscellaneous History' who first called them lovers.

But how did it come about? Did it come out of nowhere? Why exactly did some Roman writers consider this possibility, that they were lovers?

Alexander and Hephaistion in Roman-era Authors

We’re not actually sure who first (unambiguously) called them lovers. Aelian’s comment postdates one in Arrian’s writings on Epiktatos, which also claims it, not to mention the not-so-subtle hints in Arrian’s biography, where Hephaistion is compared to Patroklos (the only Alexander historian who makes that comparison, btw). Arrian was probably dead before Aelian was born. Similarly, Curtius implies it in his history, as well, although it may not be meant in a good way, there. Curtius is (probably) even earlier than Arrian.

We must remember that Alexander was an object lesson by the Roman era—mostly as a cautionary tale, but sometimes for good, too. That lent itself to oversimplifications. Seneca uses him to talk about uncontrollable rage with the murder of Kleitos, and excessive mourning with his reaction to Hephaistion’s death. He was also used to warn against overweening ambition and Too Much Drink. In short, all examples of “excess,” which was a big Roman no-no, and a Greek no-no, too. Sophrosunē (self-control) was much lauded; so also Latin disciplina. Plutarch presents the young Alexander as a shining example of sophrosunē, thanks to his Good Greek Paideia (education). But success spoilt him. While not a Roman, Plutarch lived under Roman rule and was part of the Second Sophistic—as was Lucian, who’s even more harsh towards Alexander. His “Dialogues of the Dead” includes one between Philip and Alexander where Alexander is presented as a pompous ass. There’s another dialogue just below, between him and Diogenes, which is more of the same. ATG comes out better in the dialogue with Hannibal and Scipio (and Minos).

But all that gives you some idea of how Alexander was used as (negative) exempla. Plutarch in his “On the Fortune or Virtue of Alexander” goes the other way and presents Alexander as Ubermensch. It was a standard piece of rhetoric from Plutarch’s youth, so shouldn’t be taken as his opinion on Alexander. He was showing off his speech-writing chops.

This is how Alexander was used by the imperial period and why certain anecdotes about him were repeated over and over. Hephaistion wasn’t remembered as Alexander’s chiliarch and right-hand guy, but as Alexander’s beloved friend and alter-ego: Alexander too. The story of Hephaistion and Alexander before the Persian women was quite popular, popping up again and again, sometimes to show Alexander’s generosity but sometimes to show the vicissitudes of fate (Oh, how the mighty have fallen). The nature of such anecdotes is their very malleableness. They can be used and reused to make several different points.

Hephaistion wasn’t unique. All the bit-players around Alexander came to symbolize something for stock usage. And the move from dear friend to lover isn’t a big one, in the game of ancient rhetorical telephone. 😉

It may also reflect reality. But that entails determining whether it’s the removal of prior coy language, or exaggeration for rhetorical purposes. That’s not at all straightforward.

Greeks were somewhat reticent on certain matters, and “Friend” could have romantic overtones in the right context. It’s the problem of “When is a cigar just a cigar?” Ha. In this case, when they met would have a lot to do with it. Were they indeed friends from their youth (as Curtius claims)—or only later, once Alexander was already in Asia (as Hephaistion is never mentioned in our sources about Alexander’s youth)? That’s why Sabine Müller thinks they didn’t meet until Alexander was an adult, and Hephaistion came from Athens, wasn’t just of Athenian descent. They would have met too late to be lovers, although Hephaistion was still very dear to Alexander and a perfectly capable commander (on that, we agree). By contrast, I do think they met as boys, and were lovers, and that attachment persisted into their adulthood (although perhaps not the physical affair). And that comes down to which sources we trust, and why: the historiography.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Aelian#Arrian#Curtius Rufus#Lucian#Second Sophistic#Greek rhetorical writing#ancient rhetorical writing#ancient rhetoric#Alexander as exempla#alexander x hephaestion#Alexander x hephaistion#Classics#historiography#tagamemnon#ancient Greece#ancient Rome

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Travelling Tales

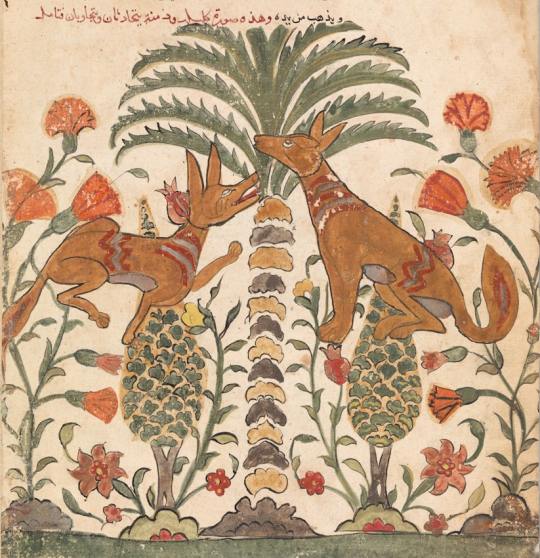

Kalīlah wa-Dimnah and the Animal Fable

By Marina Warner

Influencing numerous later animal tales told around the world, the 8th-century Arabic fables of Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ’s Kalīlah wa-Dimnah also inspired a rich visual tradition of illustration: jackals on trial, airborne turtles, and unlikely alliances between species. Marina Warner follows these stories as they wander and change across time and place, celebrating their sharp political observation and stimulating mix of humour, earnesty, and melancholy.

Kalīlah and Dimnah are two jackals, wily and ambitious, one virtuous and the other rather less so, who give their names to the eponymous cycle of animal fables in Arabic that is framed by the stories of their friendship, adventures, and mishaps.1 The collection bears a family likeness to Aesop’s Fables and to other classics of moral exempla, but the volumes vary one from one another and even when the stories coincide, they aren’t identical. They share certain generic features: animal protagonists above all (lions, wolves, monkeys, asses, mice, magpies); a narrative of braided tales passing between speakers, often imbricating one story inside the other; and a prevailing tone of tragi-comic moralising coupled with world-weary wisdom about the folly and the treachery of humans.

Most of all, the story of the two jackals Kalīlah and Dimnah, and the tales told in the course of their adventures, are travelling tales, which have been travelling for a long while, migrating from language to language, culture to culture, religion to religion. The Arabic stories’ rich history ranges from Benares to Baghdad and Basra and Rome and beyond, appearing in numerous iterations over centuries, moving across borders, carrying the sparkling hope and mordant cynicism, the canniness and the wit of a form of wisdom literature that originated in the Sanskrit Panchatantra (The Five Books, or Five Discourses) and the Mahabharata, sometime in the second century BCE. Two significant branches grew from this trunk: first, a collection often attributed to a legendary Indian sage, known as Bidpay or Pilpay, and second, the Arabic branch, beginning in the eighth century with the work of the scholar Ibn al-Muqaffa‘ (d. 139/757), who translated and compiled Kalīlah wa-Dimnah. Ibn al-Muqaffa‘ worked from a lost Pehlevi (Middle Persian) composition by a writer called Barzahwayh, which he treated freely, mixing into the Panchatantra’s original fables four more tales, and a highly circumstantial and persuasive explanation of how the manuscript was obtained; he also added a crucial dramatic chapter about Dimnah’s trial, self-defence, and ultimate punishment.

Read the whole essay https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/travelling-tales/

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incest and the Medieval Imagination, by Elizabeth Archibald: Chapter 5: Siblings and Other Relatives: Other Relatives

Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 Part 1 | Chapter 3 Part 2 | Chapter 3 Part 3 | Chapter 4 Part 1 | Chapter 4 Part 2 | Chapter 4 Part 3 | Chapter 5 Part 1 | Conclusion

As mentioned in Chapter 1, medieval incest laws targeted not only the immediate family but also extended relatives; surviving court documents indicate that the majority of public cases dealt with relationships between cousins, in-laws, and those connected through spiritual or carnal bonds, rather than within the nuclear family itself. However, these broader familial incest scenarios are rarely explored in the literature from the period.

Other Relatives

Among the most frequent narratives of step-family incest are those involving a stepmother, likely influenced by the myth of the Phaedra and Hippolytus. For instance, Fingal Rónáin (12th Century), a prince is executed by his father due to his stepmother's false claims. Similarly, in Generides (14th century), a young prince escapes his father's kingdom after his stepmother wrongly accuses him of rape. Ultimately, she confesses her lie and begs him to kill her death, but he refuses and she dies of sorrow. In both cases, the stepmother makes the accusation after her advances her rejected by the prince.

Another classical story that remained present and reimagined was that of Philomela's rape and mutilation by her brother-in-law Tereus. In some variations of the Calumniated Queen (see Chapter 4), such as Crescentia (12th Century) and Le Bone Florence de Rome (13th Century). In these versions, instead of an evil mother-in-law, it's the evil brother-in-law that lies about the Queen and attempts to have her killed or forced into exile. Usually, she is given healing powers by the Virgin or a Saint and later uses these powers to heal those thar had persecuted her, the truth then comes out and she's reunited with her husband. This plot in often found in exempla, with the incest representing sins in general and the temptation of the flesh, with the protagonist being rewarded in the end for staying loyal to her husband.

While there doesn't seem to be narratives of incest between father-in-law and daughter-in-law, that between mother-in-law and son-in-law appears in quite a few exempla, such as in the collection Alphabetum Narrationum by Etienne de Besançon (15th Century). In this story, the mother-in-law kills the son-in-law because rumours begin to circulate of their inappropriate relationship, she confesses to the priest, who spreads the news to the townspeople. The woman is taken to court and sentenced to death by fire, but she prays to the Virgin, who saves her from the fire, but the woman dies a few days later. Once again, the story serves to showcase the power of the Virgin and of repentance.

Regarding uncles and nieces, there are quite a few stories about the niece killing the children conceived by her uncle and tries to kill herself, but is saved by the Virgin. Cousins are also found in many French tale, but are rarely central to the plot. In a exception to this rule, in Tristan de Nanteuil (14th Century), the protagonist unwittingly sleeps with his cousin, who bears a son that grows up to kill him. The combination of incest leading to parricide is reminiscent Mordred (and opposite to Oedipus, which is the parricide leading to incest).

In the collection Les Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles (15th Century), there's a comical account of grandmother-grandson incest. After a man attempts to lay with his grandmother, his father becomes enraged and they fight. When a onlooker asks what caused the fight, the man says that it's "because of the one time I wanted to mount his mother. He’s done the same to mine, and more than five hundred times at that, and I’ve never said a word about it."

There are some stories that deal with incest between godparents and godchildren, such as in Manuel des Pechiez, in which a godfather seduces his goddaughter, the men confesses the sin in regret and dies, with a fire later destroying his grave. The woman's fate doesn't seem to have been mentioned. It was also considered incest to lay with your children's godparents and this is also reflected in some stories.

Overall, incest outside the nuclear family doesn't seem to have been of much interest for readers and writers, despite the many laws that forbid relationships with any kind of kinship.

#elizabeth archibald#shipcest#proship#scholarly review#Incest and the Medieval Imagination#book review

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Examining the evolution of kingship in the Ancient Near East from the time of the Sumerians to the rise of the Seleucids in Babylon, this book argues that the Sumerian emphasis on the divine favour that the fertility goddess and the Sun god bestowed upon the king should be understood metaphorically from the start and that these metaphors survived in later historical periods, through popular literature including the Epic of Gilgameš and the Enuma Eliš. The author’s research shows that from the earliest times Near Eastern kings and their scribes adapted these metaphors to promote royal legitimacy in accordance with legendary exempla that highlighted the role of the king as the establisher of order and civilization. As another Gilgameš and, later, as a pious servant of Marduk, the king renewed divine favour for his subjects, enabling them to share the 'Garden of the Gods'. Seleucus and Antiochus found these cultural ideas, as they had evolved in the first millennium BCE, extremely useful in their efforts to establish their dynasty at Babylon. Far from playing down cultural differences, the book considers the ideological agendas of ancient Near Eastern empires as having been shaped mainly by class — rather than race-minded elites."

Table of Contents

Introduction: Laying the groundwork / Dying kings in the ANE: Gilgameš and his travels in the garden of power / Sacred marriage in the ANE: the collapse of the garden and its aftermath / Renewing the cosmos: garden and goddess in first millennium ideology / The Seleucids at Babylon: flexing traditions and reclaiming the garden / Synthesis: cultivating community memory.

Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides is a senior Lecturer in Classical Studies at Monash University, Australia. She holds degrees from Aristotle University, Greece, and the Universities of Leeds and Kent at Canterbury in the UK. She studied Akkadian through Macquarie University, Australia. She has published extensively on ancient comparative literature and religion and her work has appeared in a number of journals including The Classical Quarterly, Viator, GRBS, American Journal of Philology, The Classical Journal, Arethusa, Maia and Latomus.

Source: https://www.routledge.com/In-the-Garden-of-the-Gods-Models-of-Kingship-from-the-Sumerians-to-the/Anagnostou-Laoutides/p/book/9780367879433

Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Speaking of fin de siècle end-of-history texts, I’m perpetually on the verge of finally reading through Sexual Personae, though there always seems to be another philosophical work half its length or a novel of comparable size to read… In any case this will be the year I think. I’ll confess based on the little Paglia I’ve read always pegged her as the last of the great intellectual trolls, but we’ll see. I was amused to discover recently that she herself identifies as transgender while opposing gender ideology, which throws a rather different light on a joke once I made (in the fashion that all properly educated people do, throwing around the names of thinkers whom they’ve not read comprehensively and have only a mental caricature of) that my own position on gender is the dialectical synthesis of Butler and Paglia.

You don't have to read the whole book, though, just the long first chapter, which is the "theory" part. The rest are almost freestanding critical essays on the literary or artistic exempla of the theory; they can be visited and revisited whenever you're actually reading Spenser, Shakespeare, Dickinson, Wilde, etc. I'm sure I've read every page, some many more times than once, but I've never sat down and read the book qua book cover to cover. The "cancelled preface," collected in Sex, Art, and American Culture, is really fun too:

I pity the poet or novelist in this age of mass media, but my envy is frank and unconcealed for the musician, who is able to affect the audience with such emotional directness, a pre-rational manipulation of the nerves. I long for a prose of Classic structure yet Romantic fire, as in Monteverdi or Chopin. A prose with both clarity and passion, eternal opposites of Apollo and Dionysus, a harmony of brain hemispheres. My domination by music is total. Sexual Personae could be subtitled, after a 1972 Stevie Wonder album, Music of My Mind. My "reading" of Western civilization was directly inspired by the four Brahms symphonies, which entranced me in college—in particular, the third, which I listened to hundreds of times while writing this book.

Her transgender provocation is similar (which is to say maybe I stole it from her) to my own probing at the nonbinary category, since it seems to me that I am nonbinary if anyone is, and yet I am really not, and I would pretty much die if anyone called me "they." I'm just not going to go back to the playground where brutes and mean girls said my tastes, interests, and disposition meant I wasn't a man!

The "dialectical synthesis of Butler and Paglia" is, I think, already more or less contained entire in Paglia underneath the shock rhetoric, not that I've ever been the world's great reader of the turgid and humorless Butler. Paglia does believe in the autonomy (thus necessarily the performativity) of human culture, except that for her it's (1) constrained more than it is for a poststructuralist like Butler by a biological base and—this is the far more important part—(2) subject to aesthetic criteria rendering illegitimate the kind of clumsy, coercive interventions activists and bureaucrats dream up. I know she said "you can't change sex" recently, but I think that whole question is an angels-on-pinheads abstract imponderable of no great relevance to on-the-ground questions of, say, civil liberties or pediatric medicine—themselves two distinct and separable issues, by the way, which I say as a strong civil libertarian who strongly distrusts technocratic institutions.

(P. S. The last time an anon used the phrase "gender ideology" on here, I got yelled at for an entire day by a graduate student, who, following Butler, called me a "fascist." I couldn't care less about the phrase "gender ideology," and if it bothers anybody, please substitute a more neutral label for what is, after all, an extant phenomenon, namely, the anti-essentialist critique of gender and sexual categories. I am practically a pacifist who doesn't give anybody a grade lower than "B" for finished work. If people think I am a fascist, I really hope they are able to remain sheltered and therefore never encounter the genuine article.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cellular automata - 1D Binary. silent 4k

Cellular automata - 1D Totalistic. silent 4k

Cellular automata - Cyclic CA. silent 4k

Cellular automata - General Binary. silent 4k

Cellular automata - Generations . silent 4k

Cellular automata - Larger than Life. silent 4k

Cellular automata - Life. silent 4k

Cellular automata - Conway's Life. silent 4k

Cellular automata - Life - Day&Night. silent 4k

Cellular automata - Margolus. silent 4k

Conway's life, game of life, classical cellular automaton, classical game of life, patterns of a classical cellular automaton, dynamics of a classical cellular automaton, evolution of a classical cellular automaton, classical model, classical life, classical game, cellular dynamics, cell dynamics, cell population, virtual cells, Self-organization patterns, Dynamic patterns, Emergent patterns, Emergent patterns, Stable structures, Self-organization dynamics, Self-replicating structures, Sierpinski triangle, fractal self-organization, fractal models, dynamic fractals, fractal dynamics, fractality, fractal modeling, Fractal, fractal self-similarity, fractal generation, fractal expansion, fractal propagation, fractal growth, fractal reproduction

logic gates, logical elements, basic algorithms, computing system, Turing completeness, Turing complete rule, Cellular automata, Discrete Simulation, Math modeling, Computer modelling, computer models, Discrete Models, Models of self-organization, abstract video, Science video art, Cellularum automata, Discrete Simulatio, Math modeling, Computer modeling, computatrum exempla, Exempla discreta, Exempla auto-organization, abstractum video, Scientia video art

Psychedelic, psychonautics, psychedelic patterns, psychedelic video, psychedelic animation, video psychedelic, movie psychedelic, psychedelic animation, psychedelic colors, psychomodeling, psychedelic modeling, cellular automata psychedelic, self-organizing psychedelic, self-organized criticality, cellular psychedelic, psychedelic models, visual psychedelic, line patterns, linear-angular patterns,

Generative art, modeling art, cellular automaton art, model art, scientific creativity, interactive painting, evolving art, dynamic art, generative art, computer art, digital art, digital paintings, dynamic paintings, mathematical art, mathematical art, vanishing paintings, vanishing art, discrete creativity, discrete art, discrete art, art models, art modeling, art mathematics, athematic art, art-and-mat, artimatics

Virtual creatures, virtual creatures, virtual creatures, virtual insects, artificial creatures, artificial creatures, imitation of the living, imitation of life, imitation of living beings, imitation of mobility, imitation of movement, imitation of birth, imitation of death, virtual birth, virtual death

Sedimentation, conglomerate formation, aggregation, sedimentation, crystallization, modeling, spherization

Self-organization patterns, Dynamic patterns, Emergent patterns, Emergent patterns, Stable structures, Self-organization dynamics, Self-replicating structures, Self-replicating patterns, Emergent sets, Stable dynamics, Dynamic structures, Abstraction, Emergence, Virtual evolution, Virtual population, Phase transition, Self-organization, CA , Cellular automata, Discrete modeling, Mathematical modeling, Computer modeling, Computer models, Discrete models, Self-organization models, Abstract video, Science video art, Sci art, Science art

Science cartoons, Science cartoons, Self-organized symmetry, Science art cartoons, Cartoon cartoons, Cartoons for geeks, Cartoons for insiders, Cartoons for scientists, Intellectual cartoons, Abstract cartoons, abstract cartoons, scientific cartoons, mathematical cartoons, mathematical animation, computer cartoons, computer animation,

discrete animation, algorithmic animation, algorithmic cartoons, cell animation, cartoons about cells, cell cartoons, cartoon cell atoms, moving patterns, cartoon patterns, cartoon patterns, cartoon evolution, cartoon dynamics, animation, animated video, computer animation, abstract animation, discrete a nimation , self-organization animation, simulation animation, model visualization, self-organization visualization, self-organization dynamics visualization, cellular automata visualization, cellular animation,

dynamic mosaic, dynamic population, population dynamics, symmetrical growth, fractal-like growth, flickering mosaic, flickering pattern, dynamic pattern, symmetrical pattern,

Паттерни самоорганізації, Динамічні патерни, Емерджентні патерни, Емерджентні візерунки, Стійкі структури, Динаміка самоорганізації, Саморепліковані структури, Саморепліковані патерни, Емерджентні множини, Стійка динаміка, Динамічні структури, Абстракція, овий перехід, Самоорганізація, CA , Клітинні автомати, Дискретне моделювання, Математичне моделювання, Комп'ютерне моделювання, Комп'ютерні моделі, Дискретні моделі, Моделі самоорганізації, Абстрактне відео, Науковий відеоарт, Sci art, Science art

Наукові мультики, Наукова мультиплікація, Самоорганізована симетрія, Science art мультфільми, Мультики-пультики, Мультфільми для гіків, Мультфільми для посвячених, Мультфільми для вчених, Інтелектуальні мультфільми, абстрактні мультфільми, абстрактні мультфільми чеська мультиплікація, комп'ютерні мультфільми, комп'ютерна мультиплікація,

дискретна мультиплікація, алгоритмічна мультиплікація, алгоритмічні мультфільми, клітинна мультиплікація, мультики про клітини, клітинні мультики, мультяшні клітинні атомати, рухомі патерни, мультиплікаційні патерни, мультиплікаційна еволюція, мультиплікаційна ктна анімація, дискретна анімація , анімація самоорганізації, анімація моделювання, візуалізація моделі, візуалізація самоорганізації, візуалізація динаміки самоорганізації, візуалізація клітинних автоматів, клітинна анімація,

динамічна мозаїка, динамічна популяція, динаміка популяції, симетричне зростання, фракталоподібне зростання, мерехтлива мозаїка, мерехтливий патерн, динамічний візерунок, симетричний візерунок,

Wzorce samoorganizacji, Wzorce dynamiczne, Wzorce wyłaniające się, Wzorce wyłaniające się, Struktury stabilne, Dynamika samoorganizacji, Struktury samoreplikujące się, Wzorce samoreplikujące się, Wyłaniające się zbiory, Stabilna dynamika, Struktury dynamiczne, Abstrakcja, Wyłanianie się, Wirtualna ewolucja, Wirtualna populacja , Przejście fazowe, Samoorganizacja, CA , Automaty komórkowe, Modelowanie dyskretne, Modelowanie matematyczne, Modelowanie komputerowe, Modele komputerowe, Modele dyskretne, Modele samoorganizacyjne, Abstrakcyjne wideo, Nauka wideo-art, Sztuka naukowa, Sztuka naukowa

Bajki naukowe, Komiksy naukowe, Samoorganizująca się symetria, Komiksy naukowe, Kreskówki Bullet, Kreskówki dla maniaków, Kreskówki dla wtajemniczonych, Kreskówki dla naukowców, Kreskówki intelektualne, Kreskówki abstrakcyjne, bajki abstrakcyjne, bajki naukowe, bajki matematyczne, bajki matematyczne, bajki komputerowe , animacja komputerowa,

animacja dyskretna, animacja algorytmiczna, animacja algorytmiczna, animacja komórkowa, animacja o komórkach, animacja komórkowa, rysunkowe atomy komórek, ruchome wzory, rysunkowe wzory, rysunkowe wzory, ewolucja rysunkowa, dynamika rysunkowa, animacja, wideo animowane, animacja komputerowa, animacja abstrakcyjna, dyskretna animacja, animacja samoorganizacji, animacja symulacyjna, wizualizacja modelu, wizualizacja samoorganizacji, wizualizacja dynamiki samoorganizacji, wizualizacja automatów komórkowych, animacja komórkowa,

dynamiczna mozaika, dynamiczna populacja, dynamika populacji, symetryczny wzrost, fraktalny wzrost, migocząca mozaika, migoczący wzór, dynamiczny wzór, symetryczny wzór,

Pattern di auto-organizzazione, Pattern dinamici, Pattern emergenti, Pattern emergenti, Strutture stabili, Dinamiche di auto-organizzazione, Strutture autoreplicanti, Pattern autoreplicanti, Insiemi emergenti, Dinamiche stabili, Strutture dinamiche, Astrazione, Emergenza, Evoluzione virtuale, Popolazione virtuale , Transizione di fase, Auto-organizzazione, CA , Automi cellulari, Modellazione discreta, Modellazione matematica, Modellazione al computer, Modelli computerizzati, Modelli discreti, Modelli di auto-organizzazione, Video astratto, Video arte scientifica, Sci arte, Arte scientifica

Cartoni animati scientifici, Cartoni animati scientifici, Simmetria auto-organizzata, Cartoni artistici scientifici, Cartoni proiettili, Cartoni animati per smanettoni, Cartoni animati per addetti ai lavori, Cartoni animati per scienziati, Cartoni intellettuali, Cartoni astratti, Cartoni astratti, Cartoni scientifici, Cartoni matematica, Cartoni matematica, Cartoni computer , animazione al computer,

animazione discreta, animazione algoritmica, cartoni algoritmici, animazione cellulare, cartoni animati sulle cellule, cartoni animati delle cellule, atomi delle cellule dei cartoni animati, modelli in movimento, modelli di cartoni animati, modelli di cartoni animati, evoluzione dei cartoni animati, dinamica dei cartoni animati, animazione, video animato, animazione al computer, animazione astratta, discreto un'animazione, animazione di auto-organizzazione, animazione di simulazione, visualizzazione di modelli, visualizzazione di auto-organizzazione, visualizzazione di dinamiche di auto-organizzazione, visualizzazione di automi cellulari, animazione cellulare,

mosaico dinamico, popolazione dinamica, dinamica della popolazione, crescita simmetrica, crescita simile a un frattale, mosaico tremolante, motivo tremolante, motivo dinamico, motivo simmetrico,

#animación discreta#animación algorítmica#dibujos algorítmicos#animación celular#dibujos animados sobre células#dibujos animados de células#átomos de células de dibujos animados#patrones en movimiento#patrones de dibujos animados#evolución de dibujos animados#dinámica de dibujos animados#animación#video animado#animación por computadora#animación abstracta#discreto animación#animación de autoorganización#animación de simulación#visualización de modelos#visualización de autoorganización#visualización de dinámicas de autoorganización#visualización de autómatas celulares#треугольник Серпинского#фрактальная самоорганизация#фрактальные модели#динамические фракталы#фрактальная динамика#фрактальность#моделирование фракталов#Фрактал

1 note

·

View note

Note

I'm gonna add my reply as well because answering this is WAY better than job hunting.

A good basic overview for beginners is:

Kerr, Julie. (2009). Life in the Medieval Cloister (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Also the Rule of Saint Benedict is a classic one.

There is also:

The Cambridge History of Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West, edited by Alison I. Beach and Isabelle Cochelin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Kerr, Julie. "Health and Safety in the Medieval Monasteries of Britain." History 93, no. 1 (309) (2008): 3-19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24428624.

For gender and sexuality...

you should look into Ruth Mazo Karras' work. She is a BIG name in the medieval gender and sexuality studies world. Like, so big, at a conference I went to just about everyone cited her in their papers on gender and sexuality. One book is:

Karras, R. M., & Pierpont, K. E. (2023). Sexuality in Medieval Europe : doing unto others (Fourth edition.). Routledge. (I've not read the whole book but what I have read has been useful.)

Another one is this book:

Elliott, Dyan. The Corrupter of Boys: Sodomy, Scandal, and the Medieval Clergy. The Middle Ages Series Edited by Ruth Mazo Karras. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

The Corrupter of Boys focuses on sexual abuse in the medieval church and makes you stare at the wall for a bit while reading it. I've not had the stomach to read the whole thing. One criticism I've seen of the book is that Elliot occasionally conflates sexual abuse with consenting relationships between adults, so make of that what you will.

Some other sources on gender and sexuality are:

Brozyna, Martha A. "Gender and Sexuality in the Middle Ages : A Medieval Source Documents Reader." edited by Martha A. Brozyna, xii, 316 p. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2005.

Medieval Masculinities, edited by Clare A. Lees, Thelma Fenster and Jo Ann McNamara. Regarding Men in the Middle Ages, University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. "Jesus as Mother and Abbot as Mother: Some Themes in Twelfth-Century Cistercian Writing." The Harvard Theological Review 70, no. 3/4 (1977): 257-84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1509631.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. Jesus as Mother : Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Publications of the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Ucla. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

Coon, Lynda L. Dark Age Bodies : Gender and Monastic Practice in the Early Medieval West. The Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Doss, Jacob W. "Making Masculine Monks: Gender, Space, and the Imagined “Child” in Twelfth-Century Cistercian Identity Formation." Church History 91, no. 3 (2022): 467-91.

Hotchkiss, Valerie R. Clothes Make the Man : Female Cross Dressing in Medieval Europe. New York ; London: Garland, 1996.

Kolve, V. A. "Ganymede/Son of Getron: Medieval Monasticism and the Drama of Same-Sex Desire." Speculum 73, no. 4 (1998): 1014-67. https://doi.org/10.2307/2887367. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2887367.

For primary sources on monastic life it would be worth taking a look at these sources:

Brakelond, Jocelin of. Chronicle of the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds. Translated by Diana Greenway and Jane E. Sayers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Clairvaux, Bernard of. The Letters of St. Bernard of Clairvaux. Translated by Bruno Scott James. London: Burns Oates, 1953.

Daniel, Walter. The Life of Aelred of Rievaulx. Translated by F. M. Powicke. Edited by Marsha Dutton. Kalamazoo, Mich.: Cistercian, 1994.

Heisterbach, Caesarius Of. The Dialogue on Miracles. Translated by H. von E. Scott and C. C. Swinton Bland. London: G. Routledge & Sons, 1929. (There has also been a new translation of this source that has been put out as this translation is not the best, especially when it comes to the queer monk exempla. Great source in general if you want to learn about medieval ideas about demons.)

McNeill, John T., and Helena M. Gamer. Medieval Handbooks of Penance : A Translation of the Principal "Libri Poenitentiales" and Selections from Related Documents. New York ; Chichester: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Odo Rigaldus, Archbishop of Rouen. The Register of Eudes of Rouen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1964. (This source also has an instance of two monks getting caught committing sodomy and have been sent to different monasteries as a result.)

Paris, Matthew. Translated by David Preest. The Deeds of the Abbots of St Albans, edited by James G. Clark. Gesta Abbatum Monasterii Sancti Albani. Boydell & Brewer, 2019.

Shopkow, Leah. The Chronicle of Andres, Catholic University of America Press, 2017.

Walsingham, Thomas. The St Albans Chronicle: The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham, Vol. 1: 1376–1394. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Twelfth-Century Statutes from the Cistercian General Chapter. Edited by Chrysogonus Waddell. Vol. XII, Brecht: Cîteaux, Commentarii Cistercienses, 2002.

Also, I am currently reading Fortune and Misfortune at Saint Gall by Ekkehard IV. If you're looking for a funny source, this one is really good. However, Ekkehard IV is a bad historian and takes a lot of creative liberties with truth (or just doesn't remember them). That being said, he was a 10th/11th century monk so I am willing to forgive his errors as Fortune and Misfortune documents a lot of oral history at Saint Gall.

Some online sources:

Okay, I am going to stop here as I have overloaded you. I've not read all of these sources in their entirety but I have at least read part of each one I've recommended. If you have any more questions, so feel free to reach out.

hi! I have a kinda unusual question - do you (or any of your followers) know of any good resources about how the everyday life of medieval monks looked like? or anything that discusses gender and/or sexuality questions in the medieval period (especially if it's in a monastery setting)? books, articles, or whatever format there is!

sorry if it's kinda out of nowhere, just you're The™ monkposting blog in my brain so I thought you might know. No worries if not!

I would not know of books ab the everyday lives of medieval monks unfortunately :[ I did recently pick up a book called The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction by Jamie Kreiner.. haven't gotten too far into it yet but it is a Fun read so far :]

as for gender and sexuality.. these books I have not read, but found them recommended among people whom I'm sure know better:

John Boswell's stuff, such as Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality

Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography by Alicia Spencer-Hall

monktuals chime in if you've got suggestions u_u

#research#monkposting#medieval history#also birbwell I am sorry for taking over your ask#I got excited#and I hate writing cover letters#so this was great procrastination

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There will be poems”

(This is my long-winded journey to interpreting this line from episode 9 of The Terror (2018) because my first reaction was wrong (or incomplete?) and I now feel the need to compensate... Having finished watching The Terror all of two days ago, I have only just now discovered the wealth of top-tier analysis on this show, and feel almost certain that the points I want to make are super obvious to almost everyone at this point but I’m writing this because I really, really need to talk about it. I have so many feelings. So here goes.)

One of the many scenes that really resonated with me emotionally was Fitzjames’ death scene in episode 9, and in particular Mr. Bridgens tearfully assuring him that he was a good man and that “there will be poems”. This single line made me burst into tears at the sheer tragedy of it all. Because when I first heard it, I interpreted it in a very negative, very sad way. I saw it, essentially, as the well-meaning, and sincerely-meant words of a man (Mr. Bridgens) to whom these things (poems, being remembered) mean something important, spoken to another man (Fitzjames), who no longer views those things as important. Fitzjames, after all, now views the desire to be remembered in such a way as foolish and futile in the face of the death and suffering himself and his men are experiencing, in the face of the extremity of the situation and the absence (and the vanity) of all relevant social context. I believed that at this point Mr. Bridgens simply had not come to the realisation that Fitzjames had about the reality of the situation. The line therefore appeared to me to be an expression of that very futility. Mr. Bridgens’ statement, I thought, could only be interpreted by Fitzjames himself as a sad reminder both of the man that he used to be and the illusions that he harboured, and of the ultimate emptiness of those illusions.

However, once I had recovered from the initial emotional impact of the scene, I almost immediately realised that there could be a very different interpretation of these words. The statement can be read, deceptively superficially, as an acknowledgement that Fitzjames truly was a good man, regardless of his origins or motives, and that the things he did made a real positive impact on the expedition and on the men in it (and on Mr. Bridgens specifically, of course). All of this means something beyond the realm of “vanity” – Mr. Bridgens’ praise of Fitzjames comes from someone who, as a man serving under him as a member of the expedition, has had real and tangible experience of the Commander’s actions and their impact. However, in order to truly appreciate this positive interpretation, I also have note the significance of the words chosen to convey praise and the significance of the man who speaks them.

Mr. Bridgens is arguably the character who has the most explicit and most consistent relationship with literature and poetry as a source of comfort and inspiration, as well as a means of establishing and developing important relationships, most notably with Harry Peglar. Mr. Bridgens’ reliance on classical literature for comfort and inspiration is neither a form of escapism, nor, as I mistakenly assumed, does it derive from ignorance of his situation. The support which literature provides is by no means superficial; it remains with him through thick and thin, to the very end of his life. The words “there will be poems” therefore mean something very, very important to him personally and practically. Mr. Bridgens is claiming that Fitzjames is a man whose life and actions can and “will” be counted as a source of comfort and inspiration to people. Fitzjames, for Mr. Bridgens, is a man worthy of being numbered among literary heroes. I do not believe it would be a stretch to say that among these are the Classical exempla which littered Victorian Classical education.

This is interesting because Fitzjames himself has been shown to implicitly link himself to important Classical figures (e.g. in episode 1: “I was thinking of… Caesar crossing the Rubicon”). Fitzjames clearly does this in order to bolster his stories and to feed his vanity. He does it, we realise in the context of his confession to Crozier in episode 8, essentially in order to obscure his “true” self, which he sees as fraudulent and unworthy, and of overcoming these insecurities. Caesar is chosen because Victorian Education held figures like him up as exempla, projecting Victorian values onto Classical figures (partly) in order to lend those values weight and importance. This is very much what Fitzjames does with himself: he projects himself, or an ideal of himself, onto figures like Caesar in order to highlight his own importance. He relies on Classical figures (amongst other things) for validation. (At least initially – we could argue about the significance of his costume at Carnivale in episode 6. Perhaps this is a return to his previous, vain, foolish, self in a more self-aware manner. The Carnivale in part represents “home”, England, “all that we miss”. Fitzjames donning a Roman costume here, I think, is an acknowledgement that he has moved on from that part of himself which used Classical figures for validation, a recognition that although he might still “miss” this aspect, it is no longer part of him).

However, Mr. Bridgens’ statement is not about validation, or about projecting modern men onto the past in order to aggrandise them. Mr. Bridgens has personal experience of both the importance of literature and history, and of the goodness of Fitzjames himself. He views Fitzjames as great independently of any comparison, because he has truly known him, and therefore his implicit linking of Fitzjames and great historical figures/exempla is completely organic. The words are not spoken in an attempt to validate Fitzjames, either for Fitzajmes’ benefit or for Mr. Bridgens’ own comfort – and after all, Mr. Bridgens does not need to see Fitzjames in this way, he already has his books to turn to and does not appear to need any more tangible sources of comfort and inspiration, the classics work for him in themselves (though perhaps not entirely independently of the Victorian social/educational context as a whole). Mr. Bridgens says “there will be poems” simply because he has personal experience of Fitzjames’ actions and nature, and independently makes the link with his experience of classic literature. Fitzjames’ actions have a comparable effect on him to that of Xenophon’s account of the Ten Thousand. His statement is therefore a very profound acknowledgement, a recognition. He does not need to project Fitzjames onto Classical figures in order to make sense of him, to validate his station etc. as Fitzjames himself does; he is merely acknowledging the goodness he sees in him independently. I know this may be labouring the point, but I do want to emphasise that Mr. Bridgens sees the truth and the greatness in Fitzjames which Fitzjames, who had to make hollow appeals to the Classics in order to project said greatness, did not see in himself. Mr. Bridgens’ appeal is anything but hollow.

James Fitzjames deserves to be remembered, in poetry, in literature, in culture, as a source of comfort and inspiration: as an exemplum. We have this on the best possible authority: that of a man who is an expert in finding comfort in poetry, and who recognises his feelings towards his Commander as the same feelings he holds towards literature. I can, now, only imagine Fitzjames’ recognition of Mr. Bridgens’ authority on this matter, and the realisation of what those words mean coming from him. It does not matter whether there are in fact poems or not; Fitzjames dies knowing that his actions have been great and good, have meant something to someone in themselves, knowing that his true self has been known and understood to be worthy. He dies understanding that himself. And that is, now, more than enough for him.

(So much for that. Was it strictly necessary to spend a thousand words purely for the benefit of working this all out for myself coherently? Probably not, but I love Mr. Bridgens, I love James Fitzjames, The Terror is Very Good and I have too many feelings with nowhere to put them.)

Tl; dr - James Fitzjames is Valid and Mr. Bridgens knows it.

#the terror#james fitzjames#john bridgens#mr bridgens#fitzjames#there will be poems#classical exempla#random thoughts#mostly just rambling#amc terror#mr. bridgens said fitzjames is valid#james fitzjames is valid

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm currently reading lattimore's iliad, and I'm planning to read an oresteia translated by Anne Carson. What are some other works you'd recommend/love? And the translation you like. I want to read up on the classics as I didn't really go to school past 14, and I love how passionate you are about them, so I thought I'd ask, thanks either way!

hi! sorry for taking one million years to reply to this :/ every time i try to make a Brief list of my fave texts i explode. also please bear in mind that this is a list of Texts I Personally Really Like and not a list of Texts That Are The Hashtag Classical Canon.

if you enjoy(ed. it's been a while) the iliad and An Oresteia then probably try the odyssey? i like emily wilson's translation and also ive said this before but her introduction is soooooo good. she has a translation of the iliad coming out next year and i'm probably more excited to read her introduction to it than like. the actual translation

also in the genre of epic (the best genre) i actually prefer latin epic so. definitely the aeneid (post on different translations here!) which is also very uhhh foundational for so so much of subsequent latin literature. including my other favourite epic poem, lucan's pharsalia (post on translations again!) which is a historical epic about the civil war between caesar and pompey.

this is where the list gets very much into things i personally like. the pharsalia is so cool to me because it's not a history/historiography but it Does do weird things To history and gets away with them because of its genre. veryyy similarly, aeschylus' persians is a tragedy (the only surviving tragedy based on historical events!) about the persian response to defeat at the battle of salamis. i don't have a preferred translation for this one just read whatever! but definitely read some sort of introduction or the wikipedia page because it's weird for a Lot of reasons. also necromancy happens. and there's boats. what more can anyone want!

i've also been really into livy's ab urbe condita atm. it's a history of rome but the first 5 books especially are very. well i just don't think that actually happened. BUT the early roman like. political myth making is cool actually! (if only because if you read it then when lucan is like oh and the ghost of curius dentatus was there you can be like oh i know who that guy is! a Lot of latin lit involves invoking historical exempla and livy is a major source for a Lot of those.) i actually care very little about greek myth (and the take that the romans just 'stole' greek religion. like what) because i think the romans' mythologisation of e.g. lucius junius brutus is way more fun. but ALSO livy was writing a history starting from the Foundation of rome at a time when augustus was 'ReFounding' rome so you're always a bit like. hmmmmmm. or like you read about coriolanus in livy and you're like oh wow foreshadowing of the political situation that would later lead to the civil wars! but then you remember that livy was writing it After the civil wars and then you fall into the livian timeloop and then you explode.

ok now ignore livy because my favourite historian is actually sallust. would recommend william batstone's translation of (and introduction to) the bellum catilinae. Catilina Is There. sallust's catiline is soooooo sexy like his countenance was a civil war itself! enough eloquence but not enough wisdom! animus audax subdolus varius! he's haunted by sulla's ghost! he's didn't cause the fall of the republic so much as he was a symptom of it! he's an antihero! he's cicero's mimetic double! he probably doesn't drink blood! he would have died a beautiful death IF it had been on behalf of his country (except that quote is actually from florus maybe via livy lol)! He Did Nothing Wrong. you want to read the bellum catilinae soooooo bad. also it is v fun to read alongside with cicero's catilinarian orations (the invective speeches against catilina). i think i read the oxford world's classics translation of those but i Cannot remember who it is by.

also you know what i really like what i've read of florus' epitome of roman history which is maybe kind of a summary of livy but also florus is totally doing his own thing (he is sooo influenced by lucan! nice!) highly recommend the (relatively brief) section on the first punic war. it does cool things with boats.

i also love plutarch's life of cato the younger!!! one of my favourite ancient texts of all time ever. like a) it's plutarch and he is fun. would recommend the life of alexander the great as well tbh. and b) it's cato the younger and he is so so so fucked up.

finallyyyyyy bcs this is getting long. the poetry of catullus (and a post on translations is here!) like It's Catullus. the original poor little meow meow. what more can i say

#please be aware also that i made this list via What Came Into My Brain and in a few hours i'll probably be like#how the fuck did i forget like. idk. seneca's thyestes#actually real and true. senecan tragedy does also slap. emily wilsons translations are good also.#book list#beeps

32 notes

·

View notes

Quote

On the eve of the defining event of England’s tortuous sixteenth-century relationship with Spain, the Gran Armada, the Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneira published the Historia Ecclesiastica del scisma del Reyno de Inglaterra (Ecclesiastical history of the schism of the kingdom of England), a book that appeared that portentous year of 1588, in editions at Antwerp from the Plantin press, twice in Madrid on July 20 and then on September 16, as well as in Barcelona, Valencia, Zaragosa and Lisbon. There were two further editions in Madrid the following year, from two different printers, and another Lisbon version, again from a different press. A slew of five further republications of this treatise followed between 1593-5. This cluster-bombing publication cannot be separated from the pressing contemporary need for propaganda, a battle of hearts and minds, to parallel the attempted land invasion by Alejandro Farnesio, Duke of Parma’s troops on ships commanded by Alonso Pérez de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia. For a work of propaganda, however, Ribadeneira’s account is surprisingly anodyne in its treatment of Elizabeth I, the figure the military operations sought to usurp and displace. (..) Where there was an obvious whiff of scandal, Ribadeneira inexplicably refrains from exploiting it. The suggestion that Elizabeth had consummated her relationship with Robert Dudley is resisted, although the rumor that he had his wife murdered to clear the way for a marriage is recorded. It is odd that Ribadeneira lets this golden opportunity to blacken her reputation pass, but what is notable about this account is that while at times he does not use the term ‘queen’ when talking about Elizabeth, there is no imputation of sexual impropriety, despite her association with evil exempla, biblical and classical women like Athalia, Eudoxia, and Jezebel.

Alexander Samson, “Cervantes Upending Ribadeneira: Elizabeth I and the Reformation in Early Modern Spain” in The Image of Elizabeth I in Early Modern Spain by Eduardo Olid Guerrero (ed.) and Esther Fernández (ed.)

#Alexander Samson#Pedro de Ribadeneira#Elizabeth I#Elizabeth I of England#Elizabeth Tudor#non-fiction#odd indeed#I have an idea why but it's probably wistful thinking

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Bob Dylan was a hard sell in 1985, when I first began teaching HU 417, "The Art of Song Lyrics," at Philadelphia's University of the Arts. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Doors, the Mamas and the Papas, Simon and Garfunkel, Led Zeppelin – all these groups were respectfully listened to in class by the student musicians for whom I created the course. But Dylan was another matter. To my shock, young people who had never heard Dylan before found his voice irritating, his lyrics confusing and his worldview incomprehensible. It was horrifying to realize that so titanic an artist of my own college years in the 1960s could have fallen so completely off the cultural map. This story has a happy ending. Step by step through the 1990s, students taking that course began to be intrigued, then mesmerized, by Dylan's classic songs. Why the change? First, the grunge movement, whose tragic falling star was Kurt Cobain, revived the image of the suffering, alienated artist and refamiliarized audiences with an abrasive, nasal (and probably white proletarian) vocal style that is half a strangled howl. Second, the commercial triumph of hip-hop among white teens sparked new interest in socially conscious lyrics after a period in which lyric substance had diminished, thanks to production-heavy recreational disco and operatic heavy metal. Dylan's compassion for the poor and dispossessed (as in the epic "Desolation Row") was back in fashion, and alongside rap, his packed, speed-freak lyrics suddenly made sense. Listening for the first time to "Subterranean Homesick Blues," Dylan's first hit single, students would laugh in amazement as they recognized rap's rhythmic ranting. But if Dylan's homage to the agrarian "talking blues" helps reveal the artistic ancestry of hip-hop, exposure to his work can partly undermine rap lyrics, which are sometimes formulaic and limited in scope. After twenty flourishing years of that urban genre, surprisingly few rap tag lines have passed into general consciousness or can stand as exempla of their era in the way that dozens of Dylan's axiomatic one-liners have (e.g., "But even the president of the United States/Sometimes must have/To stand naked"). Despite his pose as a Woody Guthrie-type country drifter, Dylan was a total product of Jewish culture, where the word is sacred. In his three surrealistic electric albums of 1965-66 (which remain massive influences on my thinking and writing), Dylan betrayed his wide reading, sensitivity to language, mastery of irony and satire, and acute observation of society. Next to his dazzling achievement, with its witty riffs on mythology and its vast perspective on history (as in "All Along the Watchtower"), the lyrics of too much current popular music look adolescent and parochial. Dylan is a perfect role model to present to aspiring artists. As a young man, he had blazing vision and tenacity. He rejected creature comforts and lived on pure will and instinct. He catered to no one but preserved his testy eccentricity and defiance. And his best work shows how the creative imagination operates – in a hallucinatory stream of sensations and emotions that perhaps even the embattled artist does not fully understand.

Camille Paglia, “Happy Birthday, Bob: An Appreciation of Dylan at 60″

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Snake-Poo Doctor

In 1862, an Edinburgh-trained physician, John Hastings, published a slim volume about the treatment of tuberculosis and other diseases of the lungs. It advocates the use of substances that much of the profession would regard as unorthodox, as he acknowledges in his preface:

It has been suggested that the peculiar character of these agents may possibly prove a bar to their employment for medicinal purposes.

Hastings then anticipates another likely objection—that the “medicine” he recommends is difficult to get hold of. Fear not: He can recommend some suppliers.

It may be useful to add that these new agents may chiefly be procured from the Zoological Gardens of London, Edinburgh, Leeds, Paris, and other large towns. They may also be obtained from the dealers in reptiles, two of whom—Jamrach and Rice—reside in Ratcliffe-highway, whilst two or three others are to be found in Liverpool.

One might reasonably ask what sort of medicine can be purchased only at a zoo or pet shop. Hastings explains that he spent several years trying to find novel medicinal substances in nature, without success. Deciding that pharmacies were already “crowded with medicines derived from the vegetable and mineral world,” he resolved to investigate possible miracle cures in the animal kingdom.

It would be foreign to my purpose to detail here the various animals I put in requisition in the course of this investigation, or the animal products I examined during a prolonged inquiry. It is enough to state that I found in the excreta of reptiles agents of great medicinal value in numerous diseases where much help was needed.

Yes, Hastings’s miracle cure was reptile excrement. His book is titled An Inquiry Into the Medicinal Value of the Excreta of Reptiles. Which reptiles, you may be asking?

My earliest trials were made with the excreta of the boa constrictor, which I employed in the first instance dissolved simply in water. A gallon of water will not dissolve two grains, and yet, strange as the statement may appear, half a teaspoonful of this solution rubbed over the chest of a consumptive patient will give instantaneous relief to his breathing.

This post is adapted from Morris’s new book.

Not just the boa constrictor, either. Hastings provides a list of the species whose droppings he has investigated: nine types of snake (including African cobras, Australian vipers, and Indian river snakes), five varieties of lizard, and two tortoises. After his eureka moment, the intrepid physician was eager to introduce the new medicinal agents into clinical practice, and so he started to prescribe reptile excrement for his patients. Since his specialty was tuberculosis, most of the people who came to see Hastings would have been scared and desperate. In the 1860s, there was no cure for TB; although it was not universally fatal, around half of those who contracted the disease would die, most of them within two years.

[Read: The danger of ignoring tuberculosis]

Hastings includes a number of case reports. The first concerns “Mr. P.,” a 28-year-old musician who consulted him about a troublesome cough. Unexplained weight loss had eventually prompted the diagnosis of tuberculosis:

I prescribed the 200th part of a grain of the excreta of the monitor niloticus (warning lizard of the Nile) in a tablespoonful of water, to be taken three times a day, and directed an external application of the same solution to the diseased side. He was much better at the end of a week, and after a further week’s treatment I lost sight of him in consequence of his believing himself cured.

Another was “the Reverend Q.C.,” who sought treatment after he started to cough up blood, the classic presentation of tuberculosis. He was treated with two different types of lizard poo:

I applied to the walls of the left chest a lotion composed of the excreta of the boa constrictor of the strength of the 96th part of a grain to half an ounce of water. Under this treatment his amendment made rapid progress, until the month of May, when I prescribed for him a solution of the excreta of the monitor niloticus ... of the strength of the 200th part of a grain in two teaspoonfuls of water three times a day, and directed him to use the same mixture externally.

The clergyman’s symptoms improved dramatically, and a few weeks later, he was able to walk eight or 10 miles “with ease.” But my favorite case is that of “Miss E.,” described as a “public vocalist,” which contains this magnificent paragraph:

This case is interesting, from the fact that I gave her the excreta of every serpent I have yet examined, and they all, without exception, after a few days’ use, occasioned headache or sickness, with diarrhoea to such an extent that I was obliged to relinquish their use. From the excreta of the lizards she experienced no inconvenience. She is now taking the excreta of the [common chameleon] with great advantage, and is better than she has been at any one period during the last three years.

It’s all pretty ridiculous—a fact that the medical journals of the day did not fail to point out. An 1862 review in The British Medical Journal makes an excellent point about the nature of scientific evidence, suggesting that the “positive” results he recorded were nothing of the sort:

This doctor, unfortunately, gives his cases—his exempla to prove his thesis; and we must, indeed, announce them as such to be lamentable failures as supporters of his proposition. We verily believe, and we say it most conscientiously, that if Hastings had rubbed in one-two-hundredth of a grain of cheese-parings, and had administered one-two-hundredth of a grain of chaff, and had treated his patients in other respects the same as he doubtless treated them, he would have obtained equally satisfactory results.

If The British Medical Journal was uncomplimentary, The Lancet was positively scathing. Its reviewer pointed out that 20 years earlier, Hastings had published another book in which he claimed to be able to cure consumption—using a flammable hydrocarbon called naphtha. And 12 years after that, he had decided that the cure for consumption was “oxalic and fluoric acids” (both toxic in large doses); oh yes, and “the bisulphuret of carbon” (also toxic). Hastings had in fact discovered not one but five cures. The reviewer adds, with considerable sarcasm:

As regards that—to ordinary men—unmanageable malady, consumption, all our difficulties are now at an end. The public may fly to Hastings this time with the fullest confidence that the great specific is in his grasp at last.

But he saves the best till last:

What can the public be thinking about, we would ask, when it supports and patronizes such absurd doings? Will there still continue to be found persons ready to allow their sick friends to be washed with a lotion of serpents’ dung?

Hastings was so offended by this article that he attempted to sue the publisher of The Lancet for libel. The matter was heard before the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Alexander Cockburn, who dismissed the case, ruling:

It might be that he had discovered a remedy, and, if so, truth would prevail in the end; but it was not to be wondered at that the matter was treated rather sarcastically when the public were told that phthisis could be cured by the dung of snakes.

Well said!

This post is adapted from Morris’s new book, The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth: And Other Curiosities From the History of Medicine.

Article source here:The Atlantic

0 notes

Text

Panel 1

Panel 1 : Espaces de la consommation. Investir les lieux / Spaces of Consumption. Investing Places

Président de panel : Philippe Depairon

Alyssa C. Garcia Université de Pennsylvanie Alyssa C. Garcia is a rising second-year PhD student in the History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania, specializing in ancient Roman art and architecture, with a minor focus on Byzantine art and architecture. There, she receives both the Benjamin Franklin and William Fontaine Fellowships. In 2012 and 2014, she received full fellowships to excavate at Villa San Marco (Stabiae) and Villa Adriana (Tivoli), respectively, each issued and conducted by Columbia University. She received her B.A. in Art History (2013) and a post-baccalaureate certificate in Classics (2014), both from Columbia University.

"The Holy Land Experience": Performing Jerusalem in America In the United States, an idealized Jerusalem has been created and consumed through ritual engagement with architectural reproductions of that city’s Christian monuments, in a tradition we may call “performing Jerusalem.” This paper examines this architectural genre, heretofore undiscussed collectively, via exempla of its main typologies: nineteenth-century topographic models, twentieth-century biblical theme parks and Passion Play stages, and today’s fusions of all three. The earliest imitations derive their authenticity materially, from the scientific accuracy of the reconstruction. Later reproductions lose this visual correspondence with their referent, retaining the aesthetic language of “history” and “science,” but eschewing the original compositions they claim to replicate. Instead, they base their forms on evangelical ideology, illustrating a “religious truth” that is derived only exegetically and culturally. In tracing how biblical history is literally constructed for popular consumption, a gap between archeological fact and constructed fiction emerges—one with dangerous social implications.

Émilie Hamel Université de Montréal Émilie Hamel fait sa maîtrise en histoire de l'art depuis la session d'hiver 2016 à l'Université de Montréal avec Denis Ribouillault. Elle travaille sur les statues grotesques qui ornent la villa Palagonia (XVIIIe siècle) et leur rôle dans l'expression d'une autonomie politique du pouvoir féodal sicilien par rapport à la domination espagnole et les autres qui suivirent. En avril 2017, elle a donné une conférence lors du forum étudiant du séminaire des Nouveaux Modernes intitulée « Symbolique et pouvoir à Palerme : Les Quattro Canti (1608-1630) et les processions de la Sainte Rosalie ».

Le rôle politique des sculptures grotesques de la villa Palagonia (1721) à Bagheria Située à Bagheria en Sicile, la villa des princes de Palagonia a choqué l’Europe à l’époque du Grand Tour par son décor baroque construit en 1721 et ses sculptures grotesques qui ornaient son enceinte à partir de 1753. Bien que ces dernières furent longtemps considérées comme l’expression de l’esprit dérangé de son commanditaire Ferdinando Francesco Gravina e Alliata, l’aspect et le propos carnavalesque de cet ensemble ainsi que la théâtralité de sa disposition dans un contexte de villégiature expriment également le rapport de la classe féodale à la domination des Bourbons d’Espagne et aux instabilités politiques que subissait la Sicile au XVIIIe siècle.

Clorinde Peters McMaster University Clorinde Peters is a PhD candidate in English and Cultural Studies at McMaster University and a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholar. Her work addresses the political and educative role of photography in a creative labor economy marked by neoliberal social policy. Specifically, she investigates neoliberal politics of disposability - in which particular populations are rendered collateral damage in the pursuit of capital accumulation – and the way that shifting uses of documentary photography can both visualize and resist such a politics. She has published in Afterimage (2017), the Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory (2016), and Policy Futures in Education (2015).

Counter-Narratives in Women’s Prison Photography: La Toya Ruby Frazier and Kristen S. Wilkins Incarcerated women comprise the fastest growing prison population in Canada and the United States. This paper examines the photographic work of LaToya Ruby Frazier to shed light on the neoliberal structural conditions of disposability that funnel women into the prison system, and Kristen S. Wilkins’ collaborative work with incarcerated women to rethink prison uses of photography and resistant modes of representation. Their work is poised not only to resist punitive mechanisms of the neoliberal state, but to reconfigure the masculinist genre of documentary photography. Such contemporary photographic work has the potential to oppose the prison-industrial complex and to operate as a response to the problem of images in popular and entertainment culture misrepresenting the realities of the over-incarceration crisis.

0 notes