#clara/doctor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A paltry 3 people have asked me to expand on my opinion that Clara (who I like) is bad for the Doctor, so here I go below.

Strap in, this will be long. I disliked Clara back when her tenure was happening live, but upon rewatching the show now, with my husband, I completely changed my mind and grew to really appreciate her and cried when she died. I like Clara. But I came to this conclusion you’re about to read during that rewatch. In a nutshell, Clara and the Doctor’s relationship is unhealthy. Stop wait let me explain-

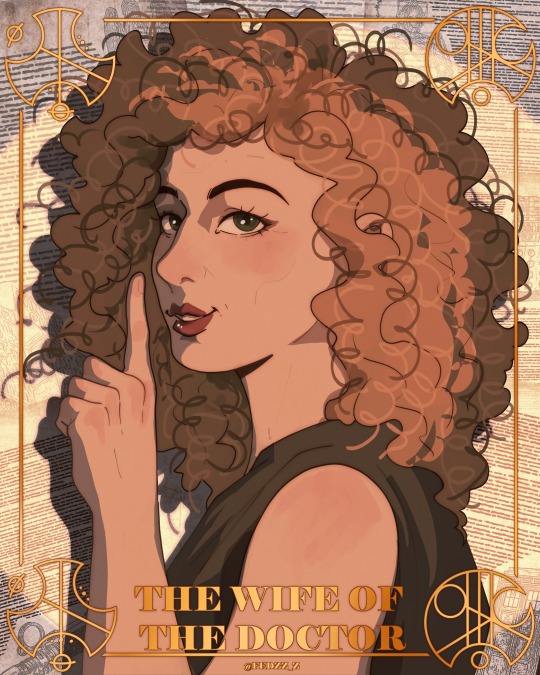

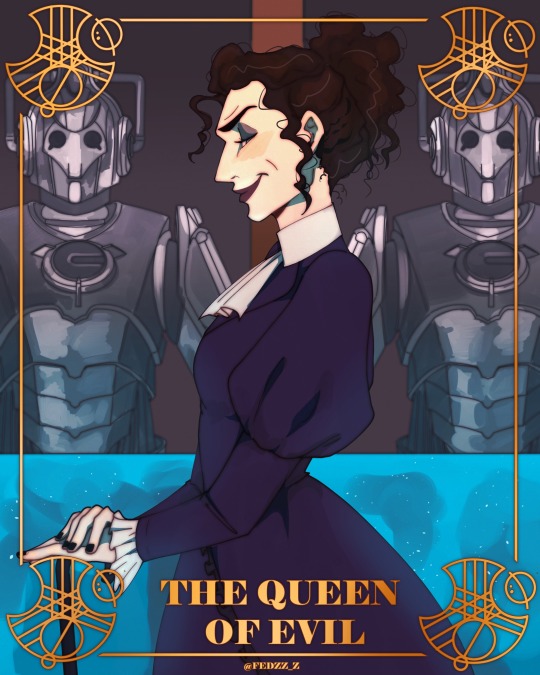

*hands you the nutshell* First. The show itself acknowledges that this Doctor/companion relationship is something unprecedented and ugly and bad for both of them towards the end. Why? Is it Clara? YES AND NO children. Clara as a companion, personality-wise, is not different from or more special than many Classic Who companions, and Jenna Coleman is ridiculously likeable as Clara. I know Clara is The Impossible Girl (because Moffat can’t write 100% ordinary people), and I know she has met all of the Doctors up to Twelve at least once, but take away her decision to throw herself into his timeline – take away the fact that the Master literally orchestrated events so that Clara and the Doctor would travel together because their personalities would create something dangerous and unhealthy in the end – and Clara herself really is just a twenty-something who wants to travel and acts like she’s the coolest person in the room. So Clara herself on the surface wasn’t the catalyst for the relationship becoming unhealthy. At least not the way she was written in the beginning. At first, it’s the Doctor making big Red Flag decisions. And I say that with so much love towards Matt Smith’s Doctor, who is dearly missed in these trying times. The Doctor meets the first version of Clara (from his perspective) as a barmaid/nanny in 20th century London. She’s exceptional (and unnecessarily flirty because Moffat can’t write women who don’t lust after the protagonist) and the Doctor invites her to travel with him. This is huge because the Doctor has just spent who-knows-how-long mourning the Ponds, who he was not ready to lose and who he had grown increasingly afraid of losing before he lost them. He sits on a cloud and has sworn off of travelling or helping anyone because he is that sick of losing people. He’s hurting and he doesn’t want to go through something like that again. The Ponds were just the latest in a very long line of lost people—remember, directly before Amy and Rory, the Doctor had to say goodbye to Donna, Martha, Wilf, Mickey, Jackie, Jack Harkness, Sarah Jane Smith oh my goodness, and Rose Tyler. And then he loses the Ponds. It’s agony. And it just keeps happening to him over and over again, and the Eleventh Doctor is especially vulnerable because he’s so tender-hearted and raw from Tennant’s losses, and this is the first time he’s lost companions with this face. The Eleventh Doctor is literally described by Moffat as the incarnation of the Doctor who chooses to forget. He’s consistently not addressing things like Gallifrey, the Time War, Rose, Donna, Martha, etc. When he’s reminded of them, the only thing he really reacts with is a strained admission of guilt (Let’s Kill Hitler and The Doctor’s Wife, anyone?). Eleven does not focus on what he has lost and worked really, really, selfishly-at-times hard to preserve the safety of the Ponds in particular. And then he loses them and throws a Doctor pity party on a cloud in a top hat.

Enter Nanny Clara, and she reminds him of what he’s missing and how things should be and helps him get his mojo back. Great, good. But she also reminds him of this one chick in the Dalek Asylum who begged the Doctor for help and was already dead. And the Doctor not only loves a mystery, but hates losing (losing people in particular). So he invites this Clara to come away with him and begin his never-ending adventure all over again, because she seems perfect for the job. And then she dies. Just like Oswin the crazy Dalek. Just like Amy and Rory, and the DoctorDonna, and Rose Tyler on the list of fatalities during the incident at Canary Wharf. Like Adric. But the Doctor doesn’t give up and pout in the 20th century this time. Instead, he gets determined to figure out what is connecting Nanny Clara and Dalek Clara, and determined to find a version of this mystery girl who can travel with him and not die this time. Third time’s the charm.

He finds Clara Oswald in the present, saves her life, freaks her out with his desperation to befriend her, and then she finally comes away with him. It’s played incredibly sweet specifically because it’s the Doctor trying to entice a companion and working for it, because he’s already seen she’s the one—twice—and is determined to keep her. This is an inversion of what usually happens, which is that the companion has to prove themselves worthy of the position to the Doctor during a meet-cute adventure. Classy. Fun. But we see from that point forward that the Doctor is kind of…weirdly obsessed with Clara. And not just because she’s appeared as three different-but-the-same people in his life lately, but because he’s the man who forgets and he lost people and never deals with that, and now he has this girl who he’s been unable to save twice before and he wants to make sure that doesn’t happen again. What’s worse, Clara becomes “the ultimate companion”, saving the Doctor throughout all his lifetimes by jumping into his timeline so she’s technically companion to all of him at one point. This is bad because not only is it not fair (as the gamers call it, it’s OP, yes I’m hip with the kids) it solidifies to the Doctor that she is the culmination of all his past failures in companion tenures.

She’s not the ultimate companion; she’s the ultimate do-over.

He’s obsessed with keeping Clara safe. He’s obsessed with keeping her with him. It’s not because Clara is this gorgeous, super-special, Not Like Other Girl(s). It’s not because he’s madly in love with her (though Moffat wants repeatedly to be able to imply that without properly saying it because he can’t write a female who is not in lust with the protagonist, hey let go of my soapbox I’m using that-). It’s not even because he lost two Claras previously and he feels really bad about that. It's because he’s projecting every single failure to keep a companion onto this one girl. The Doctor is trying so hard not to be controlled by the circumstances around him. He is trying so hard to keep this one, just this one, with him this time that he kind of turns into a withdrawal maniac when she’s in danger or choosing to do anything other than travel with him. The Master (Missy) orchestrated events so that Clara and the Doctor would be able to travel together because it was obvious the two of them would destroy each other in the end. The Doctor was such a person (Eleven) at such a time in his long life that could not stand the idea of losing one more friend and would do anything to keep history from repeating itself. He has to have Clara. He can’t quit Clara. She’s all of them. She’s everyone. And poor Clara—Clara is great, but being with the Doctor brings out only the worst in her. The woman is obsessed with herself. She was better off before he came around! Keeping pace with the Doctor, traveling the universe with him, feeling like she had something with him no one else could touch—all of that inflated her sense of importance; she has to be special. She has to be in control. She’s bossy and confident and as long as the Doctor is around, she’s the most incredible human being in her species and he is lucky to have her. That’s how he makes her feel—because it’s obvious he can’t let her go. (“Traveling with you made me feel really special.”) And worse, Clara can’t let him go—but not even specifically the Doctor. The Doctor, to Clara, is only as valuable as he makes her feel. It’s very sad because the two of them are kind of convinced they’re best friends and that’s why they’re together, but that’s not it. They’re not best friends. They’re toxic.

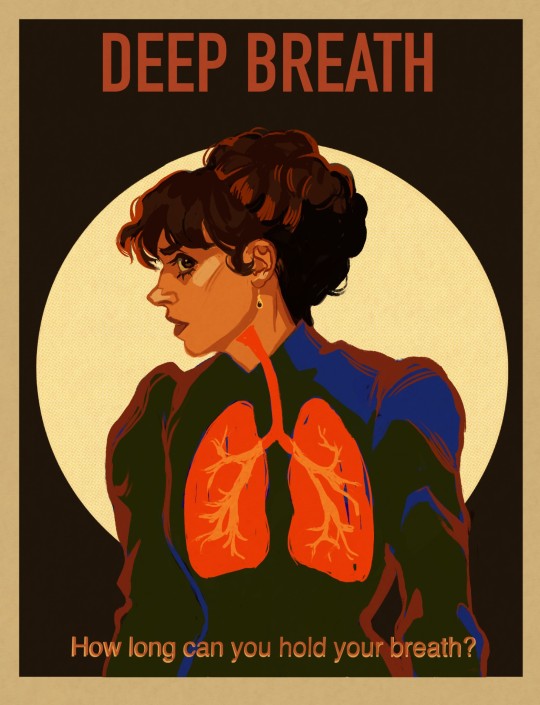

(Best friends do not trick other best friends, lie to them, threaten their way of life and only home to get their boyfriends back and then say “I’m sorry but I’d do it again”. Best friends do not notice that their best friend is there for them in spite of that line of action and then still disregard their best friend’s safety and needs in order to get what they themselves want above all else. Death in Heaven, I hate you.) And! Clara was so rattled by Eleven changing into Twelve. The sweet young man who flirted with her and made her feel so romantically important was gone, now there’s this grisly old fella who is rude to her and makes disparaging personal remarks about her physical appearance, and who doesn’t like hugs. But they’re not done. Because now the relationship has changed even further—we went from “he likes me and he should because I am Important” and “she’s staying with me and she should because I am gonna keep her safe and it won’t be like last time(s) and that’s why she’s special, that’s why she’s Impossible” to “I’m with him because he needs me and because I am Important like he is” and “she’s staying with me and she should because I am gonna keep her safe and she’s still special and she’s still Impossible and I can’t lose her no matter what”.

Clara is controlling and the Doctor is controlling. Missy would have you believe the Doctor won’t be controlled, but that’s just another form of control. The Doctor can’t stop travelling with Clara. Twelve will not let her rest, Twelve will not let her die. Clara will not stay home, Clara will not put anyone or anything else before herself, before traveling and saving the day and feeling special. In fact, it’s gotten to the point where the Doctor treats Clara with such reverence, she actually believes she’s 100% his equal and should be him. That was not a typo. I did not say she should be like him. I said she thinks she should be him. It gets worse and worse as time goes on. Clara thinks she can be the Doctor. She can travel anywhere, she can do whatever she wants, and she will always win. Because she’s important. Because she’s special. She doesn’t realize that she can’t, and that that’s not who the Doctor is anyway. And the Doctor watches Clara get eaten up by this addiction to travel, addiction to heroics. Clara loses Danny and that’s her last tether to normal life. It’s sad because Danny was twice the man anybody expected him to be and he was almost there, almost good enough for Clara to stay and be safe with. But the Doctor and time and space are a tough act to follow, and when Danny died, Clara felt she was owed better. She wasn’t angry because Danny was young and she loved him and she wanted better for him. She was angry because as a time traveling hero, she deserved to have her boyfriend alive and not hit by an ordinary car in the middle of an ordinary day on Earth. (But she wouldn’t have stayed with him anyway, and she wasted so much time with him treating him like he wasn’t special enough and then it was too late. If the Doctor had not been part of the equation, treating her like she hung the stars and making her believe it, they could have been happy. She could have been okay.)

More adventures, more close calls. At this point everything likeable about Clara in the past has faded away because she is just not the same person anymore. She’s ruined. And it’s her fault, and it’s the Doctor’s fault. Clara isn’t addicted to travel or heroics. Now she’s addicted to feeling important. She’s addicted to being special. And she needs to feel that so badly that she decides she is the Doctor and can do what he does and ignores the danger and ignores the rules and the risks and what it might do to the Doctor to lose her, and she faces the stupid raven. This girl legit dies a painful, scary death because she thought she could do whatever she wanted, control every situation, and it couldn’t possibly turn out badly because she’s Clara Oswald, the Impossible Girl. Did the Doctor ever give her any idea that that wasn’t true? Didn’t he worship the ground she marched on? She dies for it. And the Doctor, bless his poisoned hearts, cannot handle it. No way, it is not happening again. Not Clara! He’s avoided her death every other time. It’s not even about Clara anymore—Clara is actually a pretty rotten friend to the Doctor at this point; he’s nothing to her, not really, just a means to an end (and you can tell because when push comes to shove, she will choose herself and time and space over him, and over any sense at all, but if anyone asks, that’s her best friend and do you know why? because it’s very special to be the Doctor’s best friend). It’s not about her, it’s about them. About Adric, and River, and Rose, and Donna, and Tegan and Susan and Ace and Vicki. It’s about Ian and Barbara and Wilfred Mott. Not this time, universe! Not this time, Clara! "I have a duty of care." "Which you take very seriously, I know." Twelve goes through the most contrived, horrendous, comically-lengthened torture Moffat can think of (Heaven Sent) and comes out on the other side only to bring Clara back from the dead. Think of that. The woman is actually very long dead at this point and the Doctor braves literal Gallifrey to pull her out of the moment before the end. He breaks every single rule he has ever, ever had. And he does it violently, are you telling me for real that Clara is the best companion for him? She drives him to do right, to be the greatest he can be? She helps, she brings him back to who he’s always tried to be? No she doesn’t. She drives him to total depraved madman status because they can’t quit each other, and no, not the cutesy quippy Madman With A Box type of madman.

What makes Clara so different from all the other people the Doctor had to lose and who remained lost? Nothing at all. Nothing except that the Doctor decided this one isn’t going anywhere. Because she is every companion to him. This poor woman has a sack full of the Doctor’s past-companion baggage tied to her back but to her it feels light, because he treats it outwardly like a pedestal. So he “brings her back” and she figures out what he’s done and what he went through to do it, and they both learn that their relationship is actually so toxic that together, they would destroy the universe just to have what they want. Because that’s what they bring out in each other. The Doctor has to keep Clara safe, and Clara has to be special. They’re so unhealthy it affects everything around them, to the point where the Time Lords literally have a name for their destructive dynamic in their prophecies called the Hybrid (go lie down, Moffat). And the Master knew that because Time Lord…stuff…and deliberately ensured that Clara and the Doctor get together.

Luckily the Doctor is still, somewhere, miraculously, himself—so he recognizes at last that this is going too far and it’s bad, it’s all bad. The only solution, because he still can’t just return Clara to her fate, is to wipe her memory (hello Donna) of him so that they aren’t together but she also doesn’t have to die. So that he still doesn’t have to deal with losing people. And then the very worst part, writing-wise, happens. Clara complains and decides she must be allowed her memories, she’s entitled to them (too special to lose her memories!) but goodie for her, she doesn’t lose them. The Doctor, instead, loses his memories of her. Now, this is ultimately a good thing for him because of the horse I beat to death over there, don’t make eye contact, but—how sad is it that he still has to lose? That he still can’t keep someone, even after all that carnage? The healing process is beginning and he’ll be a better man than ever after this, but take a moment to mourn because that really sucks for him.

Okay here’s the worst part—Clara lives. And not only does Clara live, Clara lives forever. Clara is immortal. Clara gets her own Tardis. Clara gets her own immortal companion! (Ashildr.) Who learned something? Anyone? Not Clara! Who grew as a person around here? No one? Not Clara! Poor Clara Oswald, who started out nicely enough and likeable enough, at least on level with Classic Who companions, is ruined in the end. She gets exactly what she wants. She’s the Ultimate Companion! She’s met all the Doctors. He even fancied her at one point, well, how could he not? She didn’t die, she didn’t learn anything, she didn’t even really grow, she just got worse. Danny died and the Doctor lost, but Clara got to keep her memories, lose her mortality, and gain her own infinite time travelling machine. She became the Doctor. Yippee. Neither of them were made better by the other’s company. Rose Tyler said more than once, at least in three different ways, that the Doctor’s influence, that the opportunity to travel in time and space and help, brings out the extraordinary qualities ordinary people already have. He taps into their potential to be better, even better than him sometimes. The human factor, I call it. And they inspire him to be better, which is important for someone who is essentially immortal and can essentially go anywhere and do anything he likes. Wilfred said it, too, that Donna was better with the Doctor. But the codependency, the noxious way the Doctor and Clara interacted with each other—their whole relationship—it’s devoid of that improving quality. It wasn’t at first, at least not on Clara’s side, but that’s what it turned out to be. At least Moffat acknowledges that in Hell Bent, but he does it more in a way that is trying to communicate to you that that’s how deep and special the Doctor and Clara’s relationship is, isn’t it so important, isn’t it the best companion/Doctor relationship ever? Isn’t she hot, isn’t he whipped? Have you ever seen such devotion? Gag me. He doesn’t say it like it’s a bad thing. He’s just trying to win the 60-year-long companion race. And Clara and the Doctor both suffer for it.

I still like Clara. I blame the writing entirely for how things turned out, because I genuinely, really enjoyed her this last rewatch, and I wish that she’d met a better end. I wish she’d stayed with Danny and figured out what Danny was trying to tell her all along—that normal life is precious and worth it, and worth giving up the big sparkly universe for if you find someone else to live for besides yourself. I wish she’d sacrificed herself to save the Doctor in the present, not just throughout his past, because she proved that at one point she was capable of that. I wish she’d come to terms with the fact that she couldn’t control everything, couldn’t have what she wanted every time, and then chose to learn from that and use what she could control for the benefit of others (including the Doctor). I wish she’d gotten out the way Martha had gotten out. And I really, really wish the Doctor hadn’t had to prolong the pain he was always going to feel when someone else had to say goodbye. Anyway, that’s the essay a trifling three lovely people asked me for. Not really an essay, just word vomit. If you read it all, please let me know what you think! I could be wrong.

#clara oswald#clara oswin oswald#whouffle#whouffaldi#matt smith#jenna coleman#doverstar's thoughts#clara#the doctor#oswin#dw#doctor who#bbc#clara/doctor#doctor/clara#claradoctor#doctorclara#elevenclara#twelveclara#twelve x clara#clara x eleven#clara x twelve#eleven x clara#moffat#moffat era#thoughts#opinion piece

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whouffaldi non-canon AU. 8 chapters, 32,000 words. Rated Mature for heavier themes in later chapters, alluded to and discussed but not shown; please contact me privately if you’re worried about triggering topics.

Clara Oswald/Twelfth Doctor. Mystery, pining and angst with a happy ending. Available on AO3 under the same username and title. Originally posted in 2020.

This Isn't A Ghost Story

Chapter 1 - The House

14 November 2014, London

There was a certain amount of irony, Clara reflected, that her first reaction was I’m going to kill him.

Her ‘special friend’ had just cost her the sale of her late grandmother’s house. Again. This had to be roughly the twelfth adorable family or nice couple that had stepped into her ancestral family home only to turn tail and run before they’d even had a chance to hear about the antique hardwood floors or the fully restored kitchen. At this point, he wasn’t even being subtle about it anymore.

The longer the house sat on the market, the fewer calls she was getting to schedule walk-throughs of the property. She was beginning to worry that word of the house’s strangeness was getting around the local real estate community. If things kept up at this rate, she was going to end up permanently saddled with an inheritance whose tax burden she could barely afford, in the form of a one hundred and thirty year old, gorgeous, sprawling, haunted house.

Clara used her key to let herself in through the ornate front door, grumbling under her breath. As soon as she closed the door behind her, the cabinets in the kitchen began to rattle ominously.

“Oh, shut up,” she snapped, dropping her purse and keys on the small table in the foyer. “It’s just me.”

The door to one of the bedrooms upstairs slammed shut.

She groaned and buried her face in her hands and counted to ten before looking up again. “Listen, I get that you’re cross with me for bringing people by, but I am beyond livid with you, so let’s skip the part where I yell and you throw things and just agree to be angry with each other in silence, okay?”

The house went quiet in a manner entirely too creepy for her liking. If not for the undercurrent of petulant passive-aggressiveness, she might have actually been scared.

Not that Clara had ever really been scared of the ghost that lived in her Gran’s house. He had never once made her feel unsafe, not since she’d first spoken to him as a small child. But the sudden silence was still unnerving.

“Well, good,” she said into the preternatural stillness, more to prove to herself that she wasn’t scared than anything else. “It’s nice to actually be able to hear myself think, for a change.”

The top step of the staircase creaked once, as if to make a point.

“Still shut up,” she grumbled.

She went about the short list of tasks she’d come to see to, putting away the food she’d set out for the potential home buyers, watering the plants, closing the curtains, and flicking on a few lamps to make the house look lived-in. Of course, she didn’t envy anyone who tried to break into the house while it sat apparently empty. At some level, a poltergeist was better home protection than a dog could ever be.

Her chores complete, Clara returned to the foyer to find her purse where she’d left it, but her keys conspicuously missing. She sighed, hands on her hips, and turned towards the cold spot she could feel forming near the foot of the stairs. He was nothing but a faint wispy outline in the direct light of the setting sun filtering through the stained glass window over the front door, but even that outline was familiar enough that Clara was able to find his eyes and fix him with a displeased glare.

“Where are my keys?” she demanded. She still hadn’t forgiven him for his behaviour earlier, and she was in no mood to play find-the-lost-trinket tonight.

“I didn’t want you to leave before I could apologise,” the ghost said, not quite meeting her gaze. His voice raised gooseflesh along her arms, as usual, but she much preferred the low rumble of his Scottish brogue to the slamming of doors and rattling of cupboards. Not that she would ever openly admit that to him.

“So apologise and tell me where you’ve hidden my keys!”

“Clara,” he said, and she clenched her teeth against the shivery reaction she always had to the way he said her name, like it had been invented just so he could say it. There were days when she lived for that rush — and many, many lonely nights, in her love-struck teenaged years — but today was absolutely not one of them.

“...Was there more to that sentence?” she asked when he didn’t go on. “Saying my name does not constitute an apology.”

He glanced up at her, looking increasingly solid as the sunlight waned. “I’m sorry I upset you. That wasn’t my intention.”

“No, your intention was to make certain I can’t sell this house, and don’t bother to deny it.”

He chewed his incorporeal lip for a moment, then shrugged. “I won’t deny it. I don’t want you to sell the house. But I’m still sorry I upset you.”

Clara sighed. “I have to sell it. You know this. And someday, someone too brave or too stupid to fall for all your clattering will decide to buy this place, and that’ll be that.”

“Don’t say that,” he pleaded, his eyes glinting blue in the gathering dusk.

“It’s the reality of the situation, so you’d best start making peace with it,” she said evenly. Another irony not lost on her: arguing the state of reality with a man dead nearly a century. “Now, where are my keys?”

Her ghost hesitated. “You don’t have to leave,” he said. “You could stay?”

“I never stay the night in this house. That was your advice to me, more than twenty years ago. No sense in breaking with tradition.”

“I think maybe I was being overly paranoid at the time.”

“And I think maybe you’re acting like a lonely old man now,” Clara snarked back.

“Alone in a house that you of all people are dead-set on evicting me from? I can’t imagine why I’d be lonely!”

“It’s not like you’re stuck here! You’re not tied to the house, you can go anywhere you want!”

“But it’s my house!”

“Keys, now!” she snapped. “Traffic is already going to be horrendous—”

“All the more reason to stay,” he said petulantly.

“But,” she went on forcefully, speaking over him, “tomorrow’s Saturday, so I have the day off work. If you tell me where my keys are, I’ll come back first thing in the morning. I still need to finish going through all those old boxes in the attic. We can spend the day working on that together, okay?”

“You’re going to drive all the way home only to turn around and come back in the morning? Why not just—”

“Or I could spend the day doing something fun with people my own age, very far away from here,” she bluffed. “Your choice.”

“Oh, fine,” he said, shoulders sagging. “Your keys are hidden in the parlour, I’ll show you where.”

“Thank you,” she said mildly, and followed him into the next room.

--

As promised, Clara arrived back at her grandmother’s house early the next morning, take-away coffee cup in hand. There had been a moment, whilst she stood in the queue to order, when she’d found herself thinking she ought to get two coffees, bring her ghost a peace offering to smooth over their row from the night before. Thankfully she’d realised how ridiculous that sounded before it was her turn to order, but she still felt strangely off balance as she unlocked the front door and let herself in, like she had forgotten something important.

“Hey,” she called to the empty house, as soon as she closed the door behind her. “It’s just me, no need to go rattling the hinges on my account.”

Her ghost appeared in a shadowy corner of the foyer, smiling at her shyly. “Good morning, my Clara,” he said. “You look lovely today. Have you had a wash?”

She narrowed her eyes at him, trying to ignore the somersaulting of her heart at the way he said her name. My Clara. “Why are you being nice?”

“Because it works on you,” he shrugged nonchalantly. “And because I really am sorry about yesterday,” he added.

“Well, apology accepted,” Clara said. “And I’m sorry I yelled at you. The process of selling this place has been entirely too stressful, and I’m really starting to worry it won’t happen before the property taxes are due,” she sighed.

He ran a semi-transparent hand through the short curls at the back of his head, the ring he wore on his left hand briefly catching the light. “Yeah, about that...”

She winced. “What did you do?”

“The post came early today,” he said, voice even more apologetic than before. “I didn’t open it, but one of the envelopes has a rather official looking return address. I put it on the dining room table for you.”

She left her keys and purse on the table by the door and trudged off to the dining room, unable to contain her groan when she saw the envelope in question. Opening it, she found that he was right: property taxes were due in six weeks, the total even higher than she had anticipated. It was more than she made in a month at her teaching job. Even with the small amount she had stashed away in savings, she would hardly be able to pay it and the rent on her flat, and still expect to feed herself.

“What about the rest of your inheritance?” he asked, sounding genuinely worried.

“I put it all into fixing up this place to sell,” she said.

“Which I’ve made impossible,” he murmured.

Clara covered her face with her hands, trying not to cry and hoping he wouldn’t notice. Yes, he was the reason she hadn’t been able to sell the house to any of the dozen or so buyers who had shown initial interest. But he was also the only one in her life who even knew or cared what she was going through.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” she told him honestly, still hiding behind her hands. “If I don’t pay it, they’ll just add late fees on top of that already ridiculously large sum. If I can’t sell the house soon...”

She felt a cold touch drift across the back of her hands, felt her hair stir in a nonexistent breeze, and wished, not for the first time in her life, that her ‘special friend’ was the sort of friend who could offer a hug when she so desperately needed one.

“I don’t suppose there’s a secret stash of diamonds in the attic?” she asked him, only half joking. “Or a map to buried treasure?”

“You are descended from a line of exceptionally adventuresome women,” he replied, voice sounding distant and thoughtful. “I haven’t been up to the attic in years. I don’t know what all is in there, but anything is possible.”

Clara dropped her hands from her face and squared her shoulders, not looking at her ghost until she was certain she wouldn’t spontaneously burst into tears. “Well, let’s hope there’s something up there that will help.”

--

The attic had never been Clara’s favourite place in her Gran’s house, cramped and dusty and full of ancient boxes that gave off a far creepier vibe than the literal ghost had ever managed to do. But on the plus side, it was also windowless, dim enough that he was able to appear to her in a fairly solid state and even move lightweight objects as though he were a real person existing in the real world.

She had removed the larger pieces from the attic weeks ago, furniture and blanket chests and trunks of old clothing, all sorted through and donated to charity or brought back to her flat, or else restored to the best of Clara’s ability and set out to decorate the house in a manner befitting its age. All that remained were boxes of keepsakes, photographs and journals and old letters, small family things that required far more of her attention to sort through.

Despite the lingering threat of the taxes due, it was a pleasant morning, sitting together amidst the papers and dust, slowly uncovering the history of her family, layer on layer, like an archaeologist digging through levels of sediment. Her Gran had spent her entire life in this house, from the time she was a baby, used it as a homebase during her adventurous youth, married and raised her own daughter in it, and continued to live in it after her husband died. The boxes that littered the attic bore witness to all those many decades.

“Oh my god, these photos of Mum,” Clara said, turning the yellowed album towards her ghost so he could see them, in all their early 1970s glory. “She must have been, what, about fifteen in these?”

“Ellie’s first formal school dance,” he confirmed, leaning in to examine the photos. “With that older boy, I forget his name. Your grandfather did not approve.”

Clara snorted. “Can’t say I blame him. Look at those sideburns. I’m not sure I would have let her go out with him at all.”

“They had a huge row about it, if I remember correctly. In the end, your grandmother took your mother’s side, and she was allowed to go.”

“Why didn’t you ever appear to any of them?” she asked, flipping through the pages and pausing to linger on what looked to be polaroids of a rugby game. “You were here all that time, but you never talked to anyone until I came along?”

He shrugged. “You were the only one that was you.”

“Thanks. That clears it right up.”

“It’s the only answer I’ve got,” he objected.

“I scared the daylights out of Mum and Gran when I told them about you, I was probably all of six years old at the time.”

“Five, I think,” he said quietly.

“God, five. I might have a heart attack if my five year old started talking very confidently about her special friend the ghost that lives at Gran’s house.”

“I seem to remember advising you against telling them.”

“And in all the time you’ve known me, when have I ever taken your advice?” she asked archly.

“Hmm. There was that one time you actually listened to me, about that chap you were dating, what’s-his-name.”

Clara winced, remembering it all too well. “I thought we agreed never to speak of him again.”

“Gladly,” her ghost replied emphatically.

She shook her head, more than happy to dismiss the subject. “As a child it didn’t make sense to me not to tell Mum and Gran about you. You live in Gran’s house, the house where Mum grew up, I just assumed they already knew about you. I mean, why wouldn’t they?”

“I’m not sure I could have talked to them, even if I’d wanted to. And I never did want to.”

Clara turned her gaze to him, studying his face in the dimness. Without direct sunlight, he looked almost human, almost alive, the blue of his eyes and the salt and pepper of his hair appearing so very real, so very close at hand. He still seemed as ageless to her now as he had when she was a child. Ageless and ancient, wise and funny, solemn and sardonic. She thought perhaps she knew his face better than any other, living or dead.

“But why didn’t you ever want to talk to them?” she pressed.

“Why do you need a key to enter the house?” he asked in response.

She felt her eyebrows come together in consternation. “Because the door is locked.”

“But why that key?”

“Because... that’s the key that fits. That’s the key that goes with that lock.”

He shrugged, most of his attention on the page of the journal he’d been perusing. “You are the key that fits. I can’t give you a better answer than that.”

Chapter 2 - The Box

When Clara’s stomach informed her that it had to be well past lunchtime, she glanced up from a shoebox full of black and white photos of her Gran’s travels and spotted the ghost standing in the far corner of the attic, staring at a dusty and crumbling box she didn’t recognise, a calculating expression wrinkling his brow.

“I forgot this was here,” he murmured so quietly she almost didn’t catch it.

“What’s that?” she asked.

“Oh, just letters and photos and journals and such,” he said louder, not shifting his gaze. “The same as the rest.”

“I’m not sure I like the way you’re looking at it,” she told him playfully, shuffling through the photos in her hands. “What are you thinking?”

He hesitated. “I’m wondering if I can get it downstairs now,” he said slowly, “or if I’ll have to wait until after sunset to be able to move it.”

“Why do you want to take it downstairs?” she asked absently.

“That’s where the fireplace is. Probably ought to keep it contained. Don’t want to burn down the whole house.”

That caught her attention, and Clara put down the photos she’d been concentrating on, giving him her entire focus. “What? Why would you want to burn it?”

“It’s for the best,” he said obliquely.

“What is in that box?” she demanded, standing and crossing the cramped space towards him to get a better look at it.

“Clara,” he admonished, trying ineffectually to block her view of the box.

“That’s my family history you’re contemplating burning there, mister,” she told him. “I think I should at least get to see it first.”

“I would really rather you didn’t—”

She felt his cold touch brush against the back of her hand as she reached into the box, but it wasn’t nearly enough to deter her.

“These photos are ancient,” she said, noting the sepia colours of the few she’d managed to snag. “Who is the woman in these pictures? It’s not Gran.”

“Clara, would you please just—”

“You don’t want me to see these,” she said, putting together the pieces. “Why?”

“There are parts of the history of this house that you’re better off not knowing,” he said, more ominous than the rattling of cupboards that had scared away so many potential buyers.

“No, hang on a second,” she said, looking closer at the photos in the dim light. “Who is this? She looks exactly like—”

He winced. “Please don’t.”

“Exactly like me.”

“Clara, please.”

“What is going on with you?” she demanded, turning her gaze to him. “In all the time I’ve known you, you’ve never behaved like this.”

His jaw worked soundlessly for a moment before he finally said, “That’s your great-grandmother. The one you’re named for.”

She peered at the photos, pacing closer to the bare lightbulb hanging from the slanting ceiling to try to see them better. “Okay, but that is actually creepy. I look just like her. Why has no one ever mentioned that?”

“No one alive now remembers what she looked like. She died when your grandmother was a baby, you know that.”

“Why would you not want me to see these?” she asked, a chill working its way down her spine.

“Clara—”

“You’re scaring me,” she told him. “Really, properly scaring me, for the first time in my life. Why would you want to burn this box, rather than let me see these photos?”

“Sometimes the past is better left buried.”

“But this is ancient history! Nearly a century ago! What harm could it possibly—” she cut off as he abruptly disappeared, leaving her with the dust and her lingering questions and the echoes of familial pain.

--

After their confrontation in the attic, Clara didn’t want to leave the strange old box alone with her ghost, so she carefully carried it downstairs with her, setting it on the kitchen table as she scrounged up a make-shift lunch out of what little food there was on hand. The house had gone eerily silent after he’d disappeared, and she found herself humming under her breath as she ate and cleared up, trying to calm her jagged nerves.

“Could you not?” his voice came from behind her, and she jumped, spinning to face him. He was hazy and translucent in the early afternoon sunlight streaming through the windows near the table, but she could tell his eyes were fixed on the box and not on her.

“Don’t sneak up on me like that!”

“Would ghostly footsteps really have been any better?” he asked sourly, cutting his gaze to her briefly.

“When I know they’re from you, yes! And since when has my humming bothered you?”

“It’s not the humming so much as your choice of song.”

Clara blinked at him, trying to remember the tune. “I don’t even know what it was.”

“That’s exactly my point.” She watched him try to grasp one corner of the box, his hand passing through it, as insubstantial as cobwebs. He made a face and dropped his arm, but didn’t move away from the box.

“You still want to burn it,” she said, not quite a question.

“I’m reconsidering my stance on burning down the entire house, if that’s what it takes. Would you still have to pay the tax bill if the house were no longer here? What’s the insurance situation like?”

“I cannot believe I have to say this, but please don’t burn down the house. I will figure out how to pay the taxes, one way or another. And whatever is in that box can’t possibly be that bad.”

He looked up at her and held her gaze across the width of the kitchen. “Can’t it?”

“What is it that you’re so afraid of me knowing?” Clara asked, and he turned away, staring down into the box again. “So I look like my great-grandmother, what of it? I’m named for her, too. It’s just family resemblance, it’s hardly surprising.”

She honestly wasn’t sure which of them she was trying to convince. She’d hoped that in the bright daylight and modern setting of the kitchen, a reexamination of the photos would prove that she only somewhat resembled the long-dead woman, but her ghost’s odd behaviour was throwing that fragile hope into serious doubt.

“It’s more than that, and you know it,” he murmured, still faced away from her. “Deep down, you know it. And now it’s only a matter of time until you realise...”

The hairs on the back of her neck stood on end, and her heart thudded against her ribs. “Please tell me what’s going on,” she breathed.

He reached into the box, the shadow cast by its raised edge allowing him enough substance to shuffle through the contents within. “I never spoke to Margot — your grandmother,” he said, voice distant and detached. “Or anyone else after she was born, not until you were old enough to talk to me. But I’ve always been here. I moved things, when no one would notice. Hid things. I hid this box so long ago, I’d forgotten it was there. But I’m certain Margot never found it.”

“Why did you hide it from her? If it’s just old photos, then why—”

“I made a promise, Clara. I had a duty of care. Almost eighty-seven years keeping that promise, only for this box to resurface now.”

Clara frowned, confused. “But Gran wouldn’t have turned eighty-seven until next summer.”

“I didn’t make the promise to Margot. I made it to the only person I’ve spoken to since my death. The only one who could ever see me.”

“Besides me, you mean.”

He glanced at her over his shoulder, his expression like an open wound. “Clara.”

“What aren’t you telling me?” she asked again, trying to shake the unnerving feeling that look elicited. “There’s some deep, dark, family secret, I’m getting that much. But why does it have to remain a secret? Whatever it is, everyone connected with it is gone now. There’s only you and me left.”

He turned back to the box, gaze fixed on something inside that she couldn’t see. “I would like to think that I could tell you the basics of it and you’d leave it be. The trouble is, I know you too well for that. I know you won’t stop digging until you’ve uncovered all the gory details. If I can spare you any part of that pain...”

“I think I’d rather have the truth,” she told him bluntly.

“I know,” he said, sounding resigned. Carefully, as though it took all of his focus to accomplish, he lifted a single photograph from the box. When his hand cleared the edge of the box, the sunlight rendered it insubstantial again, and the photo drifted down to the tabletop, unsupported. “You always did demand absolute honesty from me, Clara, my Clara.” He met her eyes once more, and then was gone.

Alone again in the silence of the kitchen, Clara hesitated before crossing to the table to pick up the picture he’d taken from the box, curiosity eventually winning out over her lingering fear.

Like the photos she’d seen earlier, it was composed of monotones of brown, surrounded by a thick off-white border, but it was the image captured there that made the breath catch in her throat. A man and a woman stood side by side, gazing at each other rather than out at the camera, both smiling broadly. He was dressed in a dark suit and crisp white shirt, and she wore a pale satin gown with a dropped waist and a boxy cut. She held a bouquet of flowers in her hands, and there were more flowers in her short dark hair, formed into a circlet that held a long lace veil in place.

Any hope that Clara might have clung to that she bore only a passing resemblance to her namesake was shattered, the longer she looked at the photo. The likeness was uncanny, and downright eerie given the fuss made over this box. So far as she could tell, they were identical in every way, from their height and their facial features to the dimple that only appeared when she smiled. It easily could have been her in that photo. If she didn’t know better, she would have sworn that it was.

And if there was any other face that she knew as well as her own, it was that of her ghost. His ageless, expressive face had been seared into her consciousness since childhood, doodled in the margins of homework assignments in adolescence, and featured in her dreams for as long as she could remember. There was absolutely no question in her mind, not at first glance nor after careful examination, that the man stood beside her great-grandmother was one and the same. She would know him anywhere. His hair was perhaps a touch longer now, more untamed, but he didn’t look like he had aged a day.

Turning the photo over, she found a short inscription on the back. Clara and John, 12 May 1923 was written in large block letters, but John had been neatly crossed out, and above it small, looping handwriting had added the Doctor in its place.

She’d never known her ghost’s name, and when she had prodded him for personal information as a child, he had given her only a few sparse details. It had never particularly bothered her — she knew him, so as a child she had simply accepted that he was her ghost, and she was his Clara, and that was all that mattered. Besides, it wasn’t as though she could speak to anyone else about him, certainly not after the way her Mum and Gran had reacted.

But she wondered at it now, at the life he had led, long before she was born. She wondered about the man in the photograph, John or the Doctor or whatever he preferred to be called, this man that was so clearly her ghost. Had he had a good life? And what had made him want to linger in this house after it had ended?

She turned the photo back over, her eyes catching on his familiar face again. He looked so very happy in that frozen moment, gazing with absolute adoration at the woman who could have been her. Her great-grandmother wore a matching expression, giddy with happiness and clearly very much in love. Clara didn’t think she had ever looked at anyone that way. In her nearly twenty-eight years of life, she had never once felt for anyone what the two people in that photo so obviously felt for each other. Not anyone, except—

That thought cut short at the sound of music drifting down from upstairs, ethereal and haunting, even discounting the fact that she knew it was played by a man dead almost a century. Still cradling the photograph in both hands, Clara followed the music up the stairs, and found him in the dim back bedroom, perched on an old blanket chest with an acoustic guitar across his lap. He glanced up at her when she paused in the doorway, but didn’t stop playing. She didn’t want him to stop.

Clara watched his long fingers move effortlessly across the frets, felt the way the familiar melody reverberated out from the guitar, full of love and longing, and thought again about the expression he’d worn on that long ago day, captured in the photograph in her hands. As a teenager she had entertained fantasies that he might one day look at her like that, but as she’d gotten older she had come to accept the futility of it. He was a ghost, dead decades before she was born, and no matter how special he was to her, or she to him, there would never be any way to alter those facts.

But now she found herself confronted with something almost infinitely worse: here was her ghost directing that look at her great-grandmother. The familial implications were obvious, and distressing in a way she couldn’t even quite articulate to herself. It wasn’t just the likelihood that she was descended from this man who had featured so prominently in her life, or that he had never bothered to reveal that bit of information to her. It wasn’t even jealousy, exactly, but rather a sort of longing for what could have been. It could have been her in that photo. It should have been her.

She leaned in the doorway and listened to him play, and tried to imagine a world in which he wasn’t dead, and she was free to love him.

“That’s the song I was humming earlier,” she said softly, once the last note had faded away. “What’s it called?”

He was silent a long moment. “It’s called Clara,” he murmured, carefully setting aside the guitar and not meeting her gaze. “I wrote it, a very long time ago, for your great-grandmother. I used to hum it for you sometimes, when you were a baby. I don’t know if you were always that fussy, or if you’ve just never slept well in this house, but it seemed to... help, I suppose.”

“I didn’t know you appeared to me when I was a baby,” she said. “But I guess it makes sense.” She glanced down at the photograph in her hands, thought again on the familial relationship that could be inferred from it. “I’m not sure I have a first memory of you,” she told him honestly. “I remember the first time I spoke to you, the first time you responded, but even before that, you were always just there, every time I visited Gran.”

If she didn’t know his face so well, she would have missed the sad smile that briefly curled one corner of his mouth. “Ellie brought you here when you were a week old. Your grandfather’s health was failing, and he hadn’t been able to visit her in hospital. She let him hold you, but rather than look at him, you looked directly at me. Focused on me like I’ve never seen out of a newborn. It’d been fifty-eight years since anyone had seen me, and then there you were, staring right at me. My Clara.”

Her heart flipped over in her chest, and she looked down the photo again and willed herself to speak. “I need to ask you something, and I need you to tell me the truth.”

“And there you go again, demanding utmost honesty from me,” he said with fond ruefulness.

She hesitated, chickening out and deciding to take a slightly different tack. She held up the photo so he could see it. “Is this you?”

He glanced from the photo up to her face, like he was surprised at the question. “Yes.”

“Are you my great-grandfather?” she blurted out before she could lose her nerve again.

He winced. “That’s a complicated question.”

“It’s really not,” she pressed, gripped with the need to know, no matter how much it might hurt. “Either you are or you’re not.”

“Clara—”

“This is a photo of you and my great-grandmother, on what certainly looks like your wedding day,” she said, pushing the words out in a rush, as though that would make it easier. “You said you had a ‘duty of care’ for my Gran, a promise strong enough to keep you here for the last eighty-seven years. So are you or are you not my great-grandfather?”

He sputtered a moment, clearly not wanting to answer the question. “Legally, technically, yes,” he finally said. “If you go digging into the paperwork — wills and birth certificates, that sort of thing — you’ll find my name there. But in reality? Biologically? No. Margot wasn’t mine. There was no way she could have been mine, and your great-grandmother knew it.”

A strange sort of relief washed through her, quickly followed by confusion. “Wait, that’s the dark and terrible family secret?” she asked in disbelief. “That you’re not Gran’s father?”

He hesitated. “That’s part of it, yes,” he hedged. “And if anyone had ever found out, it would have cost her this house and the rest of her inheritance, every bit of anything that provided her with stability and security, as a girl orphaned at three months old.”

“That’s why you were trying to keep it hidden from her,” Clara realised.

He nodded. “Margot lived her entire life never knowing the truth of her parentage, which is exactly what her mother wanted. That was part of the promise I made, to spare Margot from as much of that pain as I could.”

“Why have you never told me any of this before?”

“It didn’t seem right to speak of it while Margot was alive,” he shrugged. “But you’re right, there’s only the two of us left, now. And I suppose there are some things you are entitled to know, as much as I might wish for nothing to change.”

Clara watched him for a long moment, studying his face. “There’s more you’re not telling me,” she said, trying to keep her tone from turning accusatory. “What else is in that box?”

He held his hand out for the photo, taking it from her carefully when she offered it to him. “This was a good day,” he said, staring down at the man he had been, and the woman who could have been her. “We were very, very happy. But there were less happy days, memories I would protect you from, if I can. If you’ll let me.”

“You can’t protect me from everything,” she told him, gently but firmly. “I’m not part of your duty of care. I never asked you for that.”

He looked up from the photo to find her gaze again. “My Clara. You shouldn’t have to ask.”

Chapter 3 - The Journal

Clara couldn’t sleep that night. Alone in her flat, she tossed and turned in bed, the day’s events replaying on a loop in her mind. The revelation of the identity of her ghost, the family secret he had spent almost a century protecting, her uncanny resemblance to her great-grandmother, it all felt like a complicated knot she needed to untangle. Beyond everything she’d learned, there was still more her ghost refused to tell her, and the thought nagged at her, keeping her awake.

Shortly after midnight she gave up on sleep, getting up and padding down the hall to her small sitting room. Given that it was early Sunday morning, she wouldn’t have to be up for work in a scant few hours, so if she was awake anyway she might as well do something useful. She flicked on the lamp closest to the sofa and pulled over the ancient box she’d brought from her Gran’s house, positioning it at the near end of the coffee table.

Before she left, she’d managed to extract a promise from her ghost that he wouldn’t burn down the house while she was away. But she still hadn’t completely trusted him alone with the box that had caused so much upset, so she’d loaded it into her car and brought it home with her, uncertain of exactly what she intended to do with it.

It’d been obvious that he was no more comfortable with the idea of her in sole possession of the box than she was with the thought of leaving it with him. You won’t stop digging until you’ve uncovered all the gory details, he had said to her, and she knew herself well enough to admit that he was probably right. Now that she knew of the existence of this box, she could hardly just let it be.

But it was more than simply feeling entitled to her family history. There was something there, some hidden edge of the mystery that called to her, something she felt like she should know. It wasn’t just her resemblance to her great-grandmother, or her attachment to her ghost, or his unwillingness to explain the situation to her. It’s more than that, and you know it, he’d told her. Deep down, you know it. And now it’s only a matter of time until you realise...

Clara shivered a little, remembering his words, more unnerved in the silence of her flat than she’d been when he’d first said them. Whatever this was, wherever this led, she had to know.

Glancing into the box, she picked up the wedding photograph from the top of the pile of papers and leaned towards the lamplight to examine it again. It was less disconcerting than it had been earlier, now that she knew some of the context behind it, but it was still odd to see her own face in a photo taken more than ninety years ago, in the spring of 1923. Staring at it, she was struck again by the feeling of what should have been, of how fiercely she wished it was her in that photo, marrying the man she loved.

But it wasn’t her in the photo. It couldn’t possibly be her, no matter how much it looked like her and no matter how much she wished it was. Perhaps getting to know the woman depicted there, her great-grandmother and namesake, would help her shake the feeling that somewhere along the line, fate had gone horribly awry. With that thought firmly in mind, she reached into the box and began pulling items from it.

There was no sense of order to the box, but as she dug through it, Clara began to suspect that it was the contents of her great-grandmother’s writing desk, quickly and haphazardly transferred to the box, however long ago. It was a mix of correspondence and shopping lists, photographs and small pieces of memorabilia, all jumbled together, fragile with age. She took each item out one by one, sorting them into piles as she went — a stack for photos, another for letters, a third for keepsakes, and a smaller pile for the ephemera of everyday life, things she probably didn’t need to keep. She could spend tomorrow going through them in more detail, reading the letters and looking at the photos in the light of day.

At the bottom of the box she found what appeared to be a well-loved brown leather travel journal, thick with envelopes and postcards and loose leafs of paper fitted between the pages. The front was emblazoned with a globe and the words 101 Places To See. She smiled softly, running her fingertips over its dips and ridges, and thought of her own brief travels after university. When her Dad had balked at the idea of her travelling on her own, her Gran had declared it a family tradition for the women in their family to travel. Apparently it was one that went back further than Clara realised.

Curious about the sorts of travels her namesake had chosen, she leaned closer to the lamp and opened the journal to the first entry, written in the same small, looping handwriting as on the back of the wedding photo:

1 March 1921, London

I purchased this journal for my upcoming holiday, but I fear the title may be more aspirational than factual. Mother and Father have agreed to allow me a solo European tour, perhaps under the mistaken belief that giving me that much freedom will quench my thirst for more far-flung adventures. If they knew of my ambitions, they would certainly forbid me from leaving home at all. We shall see how far I can get on the stipend they have gifted me, before their disapproval catches up with me.

A family tradition indeed, Clara thought, smiling wider, and flipped ahead a few pages.

16 March 1921, Paris

Paris is lovely, if not so very different from London. It is, however, an excellent hub from which to book further travel...

The next several pages were devoted to cataloguing life in Paris in the early ‘20s, an era that had fascinated Clara during her literature studies at university. She scanned through the entries on the off-chance that her great-grandmother might have crossed paths with a famous name during her time there. Seeing none, she ran her thumb along the outer edge of the pages to jump further ahead and get an idea of where she had gone after Paris.

Of its own accord, the journal opened to a place where a small sepia photograph had been wedged between the pages, and Clara carefully prised it free to examine it closer. Though it wasn’t nearly as crisp as the wedding photo, the two figures in it were instantly identifiable as her ghost and her great-grandmother. They stood side by side, her arm slung around his back and his draped over her shoulders, smiling at the camera and squinting in bright sunlight, a desert landscape rolling away behind them. Surprised, she turned it over to find her great-grandmother’s handwriting on the back had labeled it Doctor John Smith, Thebes Egypt, 19 May 1921.

Egypt? Her curiosity piqued, Clara backtracked a few pages to try to find the context of the photo, and when exactly her ghost had first entered her great-grandmother’s life.

2 May 1921, Cairo

Egypt is enthralling, everything I had dreamed it would be. Thankfully I find I am able to stretch my budget further here than I could on the continent. I sent my last letter home from Athens, and carefully did not mention my future plans — my hope is that I can spend a few weeks here before returning to Europe via Malta and then on to Italy, and Mother and Father will never be the wiser. To that end (and to ensure I don’t run out of funds and thus be forced to resort to begging parental assistance), I have already booked passage aboard a ship departing in three weeks.

The next few days detailed her sightseeing in and around Cairo, and Clara scanned ahead until her eyes caught on an entry almost two weeks later:

14 May 1921, Cairo

I met the most fantastic and intriguing man at the museum party last night! We spoke like old friends for near an hour and a half before he was pulled away by his compatriots, and it was only after he was gone that I realised we did not so much as exchange names. At the time, names felt superfluous, secondary to my desire to know him, but this morning I find myself wishing I could put a name to the face that hasn’t left my mind these last twelve hours.

He is Scottish, an academic of some description, though his interests and expertise seem so wide ranging, I can hardly guess at what his specialty might be. His has the nose of a Roman emperor, more regal than the bust of Marcus Aurelius that lives on the shelf in my bedroom back home, but recently burnt to peeling by the hot desert sun in a way I found entirely too endearing. There is no question that he is significantly older than myself, but he carries none of the condescension I typically associate with such an age difference. He showed more than polite interest in hearing of my travels and my thoughts on all that I have seen, and in exchange told me stories of his many adventures.

He is exactly the sort of kindred spirit I have for so long dreamed of knowing, and yet I know no hard facts about him at all. I don’t suppose we will ever meet again — and isn’t that sad? To have met someone as singular as him, spent an hour and a half in one another’s company, only to be forever lost to each other in the shuffle of humanity. At least he will be a fond memory of my time in Cairo.

Gripped by this introduction to the ghost she had known all her life and the man she had never had the chance to meet, Clara turned the page and read on.

15 May 1921, Cairo

I wrote yesterday that I know no hard facts about the man I met at the museum party, but on reflection I find that isn’t entirely true. His friends called him only ‘Doctor’, though that hardly narrows down his identity, with so many educated men roaming about the country. He has lived in Egypt for several years, can read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, and mentioned he was in Cairo on a brief respite from some activity in Thebes, on which he did not go into detail.

But a ‘brief respite’, by definition, should mean that he will return to Thebes, shouldn’t it? And then there is the matter of his sunburnt nose...

The on-going archaeological work at Thebes is widely known in Cairo, especially amongst those who frequent the museum. Could it be that this ‘Doctor’, this man who has not left my thoughts since Friday evening, could now be found in Thebes? I so wish to see him again, even if only to exchange our names and other such information, so that I might send him a postcard from time to time. And perhaps more, if he is agreeable.

And if he is not to be found in Thebes, at least I will have tried. I will be able to board the ship to Malta knowing that at least I tried to find him.

Despite knowing that her great-grandmother would, inevitably, cross paths again with the man who would become her husband, Clara read on without pause, enthralled by the unfolding drama.

17 May 1921, en route

I have left Cairo for Thebes, though it may well mean I will miss my ship to Malta. He has not been out of my thoughts, and I find I cannot wait any longer. I cannot talk myself out of this. And if there were anyone in a position in my life to talk me out of it, I would not let them, either. My mind is made up.

An adventure, then. To see the archaeological work at Thebes, and perhaps recognise a friendly face. I do hope his sunburn has not got any worse.

The next entry, adjacent to where the photograph had been tucked away, read simply:

19 May 1921, Thebes

His name is John, and I am besotted. I fear I may never recover.

Clara set the journal down in her lap and picked up the photo, looking again at their smiling faces. She tried to imagine it, meeting an interesting stranger and then striking out into the unknown, alone, on the hope of finding him again. Studying the picture, she could almost feel the desert sun on her face, and the giddy joy of new love. In just under two years, they would be married, but it had begun there, with a conversation in the Cairo museum and her great-grandmother’s bold decision to follow him to Thebes.

In the spring of 1921, she would have been just barely twenty-two years old, and Clara couldn’t help but wonder about the age of her ghost. He looked so unchanged in the photographs she had seen, the length of his salt and pepper hair the only thing that indicated any passage of time. He had always been ageless to her, but her namesake had commented on the age difference, and as she neared twenty-eight herself, Clara had to admit that he still looked significantly older than her. In his forties, easily, perhaps fifties. He’d told her that if she dug into the paperwork she would find him there, and she decided to look into it in the morning, see what information could be gleaned from genealogical websites and the like, since he’d always shown such unwillingness to answer any sort of personal question.

She turned back to the journal, curious where their story had gone in the two years between meeting and marrying. The next section was filled to bulging with postcards and envelopes tucked between the pages — a period of extensive correspondence, clearly. Clara hesitated. Reading her great-grandmother’s travel journal was one thing, but in the current moment, alone in the post-midnight silence of her flat, she wasn’t sure she could bear to read the letters her ghost had written to his future wife as they fell in love. Instead, she flipped through quickly until she reached the last of the postcards, and then read the first journal entry that followed it.

4 March 1923, London

He is in Glasgow! After all these months of correspondence, of knowing my true feelings but being unwilling to divulge them via the impersonal medium of paper, the Doctor is no more than a train ride away. And yet after the fiasco of my extended stay in Egypt in ‘21, I cannot imagine that Mother and Father will react well to my desire to go to Scotland to see him.

His postcard did not say how long he plans to be in Glasgow, only that letters sent to the university there might reach him faster than if sent via the normal address. I worry that he will be this close by for only a short time. With all the news out of the Valley of the Kings these last few months, I don’t expect he will stay in dreary old Scotland for long.

I’m afraid that if I don’t seize this opportunity, I will never get another chance to tell him of my feelings for him in person. I worry that if I ask to go, Mother and Father will not permit it, and that if I take the initiative and go without asking, they will never forgive me.

And I am afraid that the Doctor does not love me as I love him, that he won’t be able to see past the differences in our ages to all that we could be, the life that we could build together. I worry that in running off to see him, I will destroy not only my relationship with my parents, but also my friendship with him.

What fear should I let rule me? Which worry is the most likely to be true?

No.

Instead, better questions: How will I live with myself if I let myself be ruled by fear? If I do not live by the truth of my heart, how can I live at all?

I will follow him to Glasgow, as I followed him to Thebes. Let me be brave. Let the fates do as they will.

The next entry was written a few days later, detailing her clandestine departure from home and the long train journey from London to Glasgow, peppered with her simmering fears at how her unannounced arrival would be greeted by the Doctor. Her worry and her longing were palpable, and Clara felt an odd sort of kinship with this woman, her great-grandmother and namesake, as she abandoned everything in her life on the chance to be with the man she loved. She had never done anything like it herself — she had never felt that strongly about anyone, besides her ghost — but somehow it felt like something she would do.

She turned the page, looking for their reunion, but found that the next entry was dated weeks later.

28 March 1923, Glasgow

The days have been too full and too happy to find a scrap of time to add my thoughts here, so in short: one of my fears was unfounded, the other not.

The Doctor loves me as I love him. It is the truth that will chart the course of our lives together, from now until the stars all burn from the sky.

And Mother and Father will never forgive me.

The pages that followed were filled with hastily jotted down notes, interspersed with little keepsakes: a visitor’s guide to the Kelvingrove art museum, a program from an orchestral performance, a short love letter scrawled on university stationary in handwriting Clara had to assume belonged to her ghost. She folded that one back up without reading it, then skipped ahead to the date on the back of the wedding photo and found that her great-grandmother had written:

12 May 1923, Glasgow

Tomorrow we will make our farewells to Scotland and start the long journey south to Egypt, but today marks the beginning of a different and far greater adventure: marriage!

It will be a very small wedding, with only a few of the Doctor’s friends and cousins in attendance, but I find I do not care. I get to keep him, and any other concerns fade out of existence in the blinding light of that fact.

Tomorrow will also be two years since our first meeting in Cairo, and I am looking forward to revisiting the scene of that fateful interaction, this time as a married woman. How wonderful it is to have not lost that intriguing stranger to the shuffle of humanity, after all.

The journal shifted in tone after that, chronicling their journey from Glasgow to Cairo and the beginnings of their life together in Egypt, as the Doctor returned to his archaeological work in the field. In the summer of ‘23, her great-grandmother decided to take up drawing, and many of the pages that followed were filled with pencil sketches of the monuments of Egypt, the series of small homes they lived in, and the familiar face of her ghost, growing ever more accurate as her skill improved.

Clara thought of her own childhood habit of sketching his face on any blank corner of paper she could find, and wondered how they might compare. Her great-grandmother’s drawings were occasionally dated, and by the spring of 1925, the journal shifted back to being more of a travelogue again, though the entries were more sparse than they had been before, and sketches continued to fill the margins.

15 June 1925, London

Even in the height of summer, London feels grim and drab after two years in Egypt. When I said as much, the Doctor merely laughed and pointed out that it could be worse: it could be Glasgow. He has spent so many years now, off and on, living in Egypt, moving from dig site to dig site as the work demands, and I think he is ready for a more settled existence for a while. The position at the British Museum suits him well, and will provide us with a more stable foundation on which to build our life — and as much as I enjoyed our transient circumstances in Egypt, there is a certain allure to building something lasting together. A new sort of adventure.

I had hoped that with our return to London, and after two years of marriage, Mother and Father might have found a way to forgive me, but it seems that door is forever closed. I am determined to focus on the future instead, and on the family the Doctor and I mean to create together.

Reading that, Clara felt a pang of heartsickness for this woman she had never known. She had been close with both of her parents before their deaths, and was grateful to have had that time with them. She couldn’t imagine her parents being so angry with her that they would shut her out of their lives, but scanning ahead, she didn’t see any indication that her namesake’s parents had ever relented. Instead, the journal dealt with the process of settling back into life in London, and her great-grandmother’s dreams for the future, with small sketches peppering the edges of each page.

As she turned the pages, Clara’s eyes caught on the rare use of colour in one of her drawings, and with a surprised blink she realised she recognised it as the stained glass window over the front door of her Gran’s house. The journal entry beside the drawing read:

1 August 1925, London

The House, as I have determined it must always be called, is a ridiculous rambling Victorian thing, all gabled roofs and ornate woodwork and stained glass windows, such as the one I have drawn here. It is entirely too large for the two of us, but it was love at first sight for both the Doctor and myself, and no house we have considered since has compared. At least there will be enough room for our ever-growing legion of books. And there are several bedrooms — perhaps it is too ambitious of me to imagine them someday filled, but despite all our failed efforts, I remain hopeful.

Having dealt so closely with her Gran’s personal details the last few weeks, Clara knew that she would be born barely three years later, in late August of 1928. Her great-grandmother died only a few months after that, and it felt strange to read of her hopes for a large family, knowing it didn’t happen in the end. Through reading her journal, it had become clear to Clara that they were alike in many ways, but on that one point they couldn’t be more different. She enjoyed children, she wouldn’t have become a teacher if she didn’t, but she’d never felt drawn to motherhood. She was almost the same age as her namesake had been when her Gran was born, and she couldn’t imagine having a baby now, much less hoping for multiple children.

Of course, she wondered if she might feel differently if she’d had the sort of fairy tale romance her great-grandmother had had. Starting a family with someone she loved felt a lot less abstract than the vague idea of having a baby. Maybe that was the difference. She could certainly understand her great-grandmother wanting children with the Doctor—

At that thought, it all came back to her in a rush, everything her ghost had revealed that afternoon, the truth of her Gran’s parentage — and with it, one of the few facts about him that she’d managed to wring out of him as a child. With dread turning her stomach, Clara quickly flipped ahead to the autumn of 1927, scanning the journal entries for any indication, any clue. There was a brief note in early November about plans for Christmas, but then nothing until:

1 December 1927

He is gone. He is gone, and I will never, ever recover.

The bruises may heal, but I will not.

Tears sprung to Clara’s eyes, but she blinked them away, reading on.

8 December 1927

Is it the House that is haunted, or me?

She stared at the words, knowing that almost eighty-seven years later, the house was very much haunted. She turned the page, feeling the tears begin to roll down her face.

12 December 1927

Perhaps it is only my mind playing tricks on me, but perhaps it is something more. Perhaps there is some magic that ties us together even now. I live in hope — for what other way is there to live, now?

The following pages were full of nothing but undated sketches of the Doctor, looking exactly as Clara knew him. I made that promise to the only person I’ve spoken to since my death. The only one who could ever see me, her ghost had told her, not twelve hours earlier. Gripped with the need to know, she turned the journal pages quickly, looking for her great-grandmother’s familiar handwriting amongst all the drawings of her ghost, until finally:

3 February 1928

I have counted out the days and counted them again. My memory of last November is far from clear, but there is no mistake in this: I am with child. And this is no parting gift, no consolation prize from the universe, only one more tragedy to heap onto the pile. This baby will not have the Doctor’s eyes or his smile or his laugh. This baby—

How am I to endure this? Alone in the House we had hoped to fill, how can I possibly find the strength to face what is to come?

I continue to dream of him, to have visions, even. Some days I fear I have gone mad with the grief, but other days, those visions are my only comfort, those dreams my only reprieve from the nightmares that plague me. Something in my heart refuses to believe that the Doctor is truly gone. Something compels me to speak to him, and hope that he will, somehow, impossible though it may be, hear me and respond.

And then:

8 February 1928

They are not visions, and I am not mad.

But more importantly — I am no longer alone.

Clara set down the journal, taking a moment to swipe at the tears on her face. She had known, deep down she had known that she would find only pain at the end of this story, and yet she hadn’t been able to stop herself. I know you won’t stop digging until you’ve uncovered all the gory details, he’d said to her, and he’d been right, of course he’d been right. Her ghost had tried to protect her from this, but she had charged ahead anyway, disregarding his warnings.

And that edge of the mystery still called to her, the unanswered questions still nagged at her. However much it hurt, she had to know. Picking up the journal again, she skipped ahead, flipping pages until she reached her Gran’s birthday.

21 August 1928

It is a girl. I have named her Margaret Eleanor, as we so long discussed. Our little Margot. None of this is her fault, and I do not love her less for it. I only wish I could love her more. I wish my heart were still capable of it. I wish I could have greeted her arrival with the joy she deserves. I wish I didn’t have to welcome her into the world alone.

The more days pass, the more I am convinced the Doctor meant what he said as a final goodbye. The last six months with him have revived me in a way I didn’t think possible, and to have that ripped away, to once again be facing the prospect of a future without him—