#circa 1832

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

IN HONOUR OF BARRICADE DAY, A DISCOVERY

oh my god ok so ITS BARRICADE DAY (THE ANNIVERSARY OF THE REBELLION ON WHICH A LOT OF LES MIS IS BASED, LIKE VICKY HUGEHOE MADE UP A BUNCH OF CHARACTERS AND STUCK THEM IN THE STUDENT UPRISING OF 1832 WHICH HAPPENED ON THE FIFTH AND SIXTH OF JUNE) SO IM CONSUMING NOTHING BUT LES MIS CONTENT TODAY WHICH HAS BEEN THE TRADITION FOR LIKE TEN YEARS FOR ME AND LIKE 191 YEARS FOR EVERYONE ELSE AND SO I WAS READING THIS NEWSPAPER FROM 1832 TALKING ABOUT THE REBELLION i was reading a newspaper about the rebellion and the paper was from 1832 and jesus, mary, joseph, and the cow you are not going to believe what i found, I THINK I MIGHT HAVE DISCOVERED THE INSPIRATION FOR GRANTAIRE????? OK SO. i m m e d i a t e l y after the article about the rebellion was this little mini-story abt this motherfucker:

LIKE PARDON????? OK BC AND LIKE ITS UNLIKELY BUT NOT IMPOSSIBLE THAT THAT FUCKING GUY THAT MOTHERFUCKER MIGHT HAVE BEEN THE INSPIRATION FOR GRANTAIRE?? BC LIKE. BEING IN A DRUNKEN STUPOR, ASSUMED TO BE DEAD, ONLY AT THE VERY LAST POSSIBLE MOMENT WAKING UP A N D DECLARING THAT HE'D NEVER GET DRUNK AGAIN BC 1 HE WAS GNA DIE WITH ENJOLRAS AND 2 HIS DRUNKENNESS WAS A METAPHOR FOR WHY HE WASNT LIKE NOBLE AND SHIT AND HIS CYNICISM BUT ENJYBABY TURNED HIM INTO A BELIEVER??? normalize believing very very very unlikely things bc it's funny shhh

#enjolras#grantaire#les mis#les miserables#les miz#victor hugo#barricade day#student uprising of 1832#circa 1832

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tago Bay near Ejiri on the Tokaido from the Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji series, Katsushika Hokusai, circa 1832

Woodblock print 9 ¾ x 14 ½ in. (24.8 x 36.8 cm)

#art#katsushika hokusai#hokusai#asian art#19th century art#19th century#1830s#works on paper#monut fuji#japan#japanese#ukiyo e#woodblock print#print

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hydrangea and Kingfisher (circa 1832) by Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese, 1797–1858).

Woodblock print. Published by Wakasaya Yoichi.

Carnegie Museum of Art.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Travel Question 58: Performances IV

These Questions are the result of suggestions from the previous iteration.

This category may include suggestions made too late to fall into the correct grouping.

Please add new suggestions below if you have them for future consideration.

*The Broadway Premiere names were lost over a year ago because I didn't realize how big this was until I'd spent several hours on first day telemetry for the very first Time travel poll.

Please Feel Free to share ones you want to see for future polls.

#Time Travel#Concerts#Lost Music#Luciano Pavarotti#Three Tenors#Ivan Rebroff#Percy Grainger#Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov#Broadway#Paris Catacombs Concert#Paris Catacombs#Lysistrata#Ancient Greece#Theater History#Plautus#Ancient Rome#Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky#Sarah Bernhardt#Music History#Queer History#Women in History#Marie Camargo#Dance History#Marie Taglioni#La Sylphide#18th Century

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flood Destroying the World, circa 1866. Illustration by Gustave Doré (1832-1883).

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashions of the Early 1830s: Large Hats and Leg-o-Mutton Sleeves

I was obsessed with Victorian era fashion for way too long! Let's jump back a few years and take a look at what royals and high-society women were wearing from 1830 to about 1836.

Vincente López Portaña (Spanish, 1772–1850) • Maria Cristina de Bourbon, Queen of Spain (fourth wife of Fernando VII) • 1830 • Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The style of the blue gown above is in keeping with Romantic era fashion, with its elbow-length puff sleeves with lace trim and pleated bodice. For formal attire, long gloves were worn.

The Maria Cristina de Bourbon portrait is of a royal subject, therefore the jewel-studded headpiece is especially grand, as is the bodice ornament and earrings. The feather was characteristic of the times – very large hats with feathers were in vogue, as well as large bonnets. The Spanish queen is wearing a lace mantila with her headpiece, which I assume is a symbol of her Spanish heritage.

The fabric of the queen's dress is extraordinarily elaborate, with all-over silver thread embroidery. The bodice on this and many early to mid 1830s dresses was called a bodice à la Sevigne, which was made up of a central boned band divided into horizontal folds of fabric.

Belts and wide ribbons around the waist were often featured on dresses of the early to mid 1830s.

The fashion from circa 1830 to 1835 was one of over-porportioned extravagance. Sleeves larger than were ever seen or since been, width at the shoulders, and dramatic hats and headpieces.

Hair too was over-the-top. Notice the perponderance of elaborate braids, coils, and curls in these images.

1830-34 • British • Printed Cotton Day Dress • Victoria and Albert Museum

One such dramatic feature of 1830s fashion was the pelerine, a lace covering that was worn over the shoulders. The cut of the neckline was already exagerated to emphasize width at the shoulders; adding a pelerine only added to that width as well further acting as more ornamentation to the outfit.

François-Joseph Navez (Belgian, 1787-1869) • Théodore Joseph Jonet and his two daughters • 1832 • Private collection

Sleeve style quickly evolved from simply puffy to Gigot or leg-o-mutton sleeves – a huge, billowy sheer sleeve over a smaller one, continuing with a tight-fitting long sleeve.

This flamboyance in sleeves was to suddenly come to an end around 1836. More about that in a future post, as I continue to flit willy-nilly along the fashion history timeline!

References:

��� Fashion History Timeline: 1830-1839

• Wikipedia: 1830s in Western Fashion

• Wikipedia: Pelerene

• Mimi Mathews: The 1830s in Fashionable Gowns: A Visual Guide to the Decade

#art#portrait#painting#fashion history#royal portraits#fine art#art history#romanticism and fashion#1830s fashion#historical fashion#art & fashion#family group#the resplendent outfit blog#art & fashion blog

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katsushika Hokusai ‘Yoshitsune’s Horse-Washing Falls at Yoshino in Yamato Province (Washu Yoshino Yoshitsune uma arai no taki),’ from the series ‘A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces (Shokoku taki meguri),’ circa 1832; Courtesy Heritage Auctions

#katsushika Hokusai #japanese artist painter #artist painter #original art

#art #xpuigc #raiko huyiro

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katsushika Hokusai, "The Waterfall Where Yoshitsune Washed His Horse at Yoshino in Yamato Province," from the series A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces, ca. 1832

Marguerite Thompson Zorach, Bathers, circa 1913-1914

#katsushika hokusai#Marguerite Thompson Zorach#waterfalls#nature#landscape#japanese prints#japanese art#asian art#japanese artist#woodcut#woodblock print#women artists#woman artist#landscape art#landscape aesthetic#art on tumblr#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#aesthetic#tumblrstyle#beauty

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The “Royal George” Sperm Whale tooth, circa 1860

Depicts the survey of HMS Royal George, 1832, which sank in the Spithead off Portsmouth in 1782.

#naval artifacts#scrimshaw#hms royal george#shipwreck#spithead#18th century#19th century#age of sail

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Cafetière" de Balzac en porcelaine de Limoges (circa 1832) présentée dans la “Maison de Balzac” dans le quartier de Passy, Paris, octobre 2024.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've had this thing for ages but haven't worn it as it does feel a touch embarrassing to wear, but on my way back from the gym it started raining, and all I had on me was this

Now two things went through my head. 1, I can either commit social suicide, have strangers who I momentarily will pass then never see again, who mean nothing to me and do not matter in the slightest, judge and mock me for wearing this, yet I stay dry and prioritise myself over what others think of me. Or 2, I can get soaking wet. Obviously the former is far worse, but I gaslit myself into thinking the latter was worse, and wore it

Honestly I kept smiling and laughing at myself. But ya'know what? It's a look. It's giving. It's giving peasant circa 1832. Cindy Lou who that bitch think she is? She thinks she could pull this off or better in her Louis Vuittons? I don't think so bitch. It's giving take me daddy trash man, I'm a naughty garbage bag and I deserve to be compacted. Keep your man on a tight leash when I strut up wearing this, it's all I'm saying. You know I had to do a little runway shoot to boast how good I looked in my black sack

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yoshitsune's Horse-Washing Waterfall at Yoshino in Yamato Province, Katsushika Hokusai, circa 1832

Woodblock print 37.6 x 24.6 cm (14 ¾ x 9 ¾ in.)

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

'White Heron and Iris' (circa 1832-34) by Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese, 1797-1858).

Woodblock print.

Image and text information courtesy Art Institute Chicago.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Born into slavery, he rose to the top of France’s art world

by Sebastian Smee - The Washington Post, July 12, 2024

Guillaume Lethière’s epic life is the subject of a stunning new exhibition, in the U.S. before it travels to the Louvre.

Guillaume Lethière, “Woman Leaning on a Portfolio,” circa 1799. (Frank E. Graham/Worcester Art Museum/Bridgeman Images)

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass. — During the most tumultuous period in France’s modern history, Guillaume Lethière was one of its most venerated artists. His story is epic. Charles Dickens or Alexandre Dumas (who delivered a eulogy at Lethière’s funeral) would have struggled to make it sound credible. Pity me, your poor reviewer.

He was the third child (“Le Thière” is French for “the third”) of an enslaved, mixed-race woman and a White plantation owner. Today, his paintings — some of them cinematic in scale — can be found in museums in the United States and Europe, including the Louvre, and also in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Among his smaller works is one of the most tender and beautiful portraits I know.

Don’t feel bad if you’ve never heard of him. But be aware that in Guadeloupe, where he was born in 1760, Lethière has long been celebrated. According to Esther Bell, the curator of an extraordinary new exhibition about Lethière, there is an auto-body repair shop in the coastal town of Sainte-Anne bearing the name “Guillaume Lethière.” Nearby, in the center of a busy rotary in the French neighborhood — previously the site of the plantation whereLethière grew up — is a huge steel sculpture in the shape of an artist’s palette alongside two enormous paintbrushes. Shapes cut out of the steel reveal the face of Lethière as he looked in an 1815 drawing by his pupil, the great neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

This summer, you might see Lethière’s loveliest portrait (scholars think it probably depicts his stepdaughter, Eugénie Servières, herself an accomplished artist) blown up on highway billboards advertising “Guillaume Lethière” at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., through Oct. 14. The exhibition will travel to the Louvre in November.

Guillaume Lethière, “Lafayette Introducing Louis-Philippe to the People of Paris,” 1830-1831. (Tokyo Fuji Art Museum/Bridgeman Images)

Researched and developed over many years by Bell, the Clark’s deputy director and chief curator, with Olivier Meslay, the museum’s director, and accompanied by a 432-page catalogue, the exhibition tells the story of Lethière’s improbable life.

To understand his significance, it’s not enough just to look at his paintings and drawings — although these are very good and earned him accolades aplenty during his lifetime. You need to consider his own complicated proximity to the world-historical events through which he lived.

Born into slavery (or so it’s assumed, given his parentage and the telling absence of baptismal records), Lethière was brought to France by his father, the French king’s public prosecutor in Guadeloupe, in 1774, when he was 14. He began training as an artist in Rouen. Thanks to his father’s influence, he was already close to serious power by his late teens.

Guillaume Lethière, “Académie,” 1782 (Beaux-Arts de Paris/RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York)

But of course, staying close to power is not easy when the personnel keeps changing. Like others of his generation, Lethière had to steer a course through the last days of the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, the Terror, the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, European conquest, imperial collapse, a brief Bonapartist revival, a restored monarchy, and finally, just before Lethière’s death in 1832, a constitutional monarchy.

What makes him uniquely interesting is that he managed all this while also navigating the shifting implications of his illegitimate, mixed-race origins in Guadeloupe.

Lethière was neither smarmy nor sycophantic, but he knew how to ingratiate himself to others. He “won the esteem and friendship of everyone by his honesty, his politeness, and a frank and loyal character that never wavered,” wrote Francois-Guillaume Ménageot, the director of the French Academy.

Alexandre Clément, after Louis-Léopold Boilly, “Reunion of Artists,” 1804. Guillaume Lethière is shown at center. (Clark Art Institute)

Lethière and his mother, Marie-Françoise Pepeye, were both emancipated by his father, Pierre Guillon. But it was many years before changes to the law allowed Guillon to recognize Lethière as his son. Lethière and his sister were named as Guillon’s heirs around the time Napoleon seized power in 1799.

Even so, years later, Lethière had to defend himself against an embarrassing challenge by a distant cousin, who claimed he was the rightful heir. This was in 1819, when the artist was at the height of his renown. The courts eventually found in Lethière’s favor — but not before humiliating references in the press to the esteemed painter’s “naive and modest genealogy.”

Louis-Léopold Boilly, “Guillaume Lethière and Carle Vernet” circa 1798. (Stéphane Maréchal/Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille/RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York)

Moral and political complexities choked almost every aspect of Lethière’s life. There’s no doubt, for instance, that he was an abolitionist. And yet he benefited financially from his father’s plantation, which depended on enslaved labor.

Although Lethière never returned to the Caribbean, he cared deeply about the fate of its people. He supported the revolution in Haiti, which began in 1791, just before the French monarchy was abolished, and welcomed the French government’s decision, in 1794, to end slavery in all its territories.

When, eight years later, Napoleon reinstated slavery in the colonies, brutally suppressing an attempt at resistance in Guadeloupe, Lethière was surely disappointed. But by now he was in with the Bonapartes. He painted portraits of, among others, Napoleon’s Caribbean-born wife, the Empress Joséphine, and hitched his fortunes to Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother.

Guillaume Lethière, “Joséphine, Empress of the French,” 1807. (Franck Raux/Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon/RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York)

In 1807, Lethière’s friendship with Lucien Bonaparte led directly to his appointment as director of the French Academy in Rome — an immensely prestigious post. There he reinvigorated the academy andoversaw the training of dozens of France’s best artists — among them Ingres, who made a series of stunning drawings of Lethière’s family (included in the show), and a female pupil, Antoinette Cécile Hortense Lescot, who went on to exhibit more than 100 paintings in the Paris Salon.

Ancient Rome was of intense interest not only to France’s revolutionaries, who looked to republican Rome as a model, but also to Napoleon, who of course saw more upside for himself in Rome’s imperial period. Art played a huge role in establishing these lines of pedigree.

Guillaume Lethière, “Brutus Condemning His Sons to Death,” circa 1788. (Clark Art Institute)

The French Revolution had broken out while Lethière was a student at the same academy in Rome. At the time, inspired by his environs, he worked on a major canvas, “Brutus Condemning His Sons to Death.” In a carefully structured, frieze-like composition, he depicted the founder of the Roman republic, Lucius Junius Brutus, looking on stoically as his sons, who had plotted to restore a monarchy, are decapitated.

Lethière returned repeatedly to this subject and to another episode from ancient Rome, “The Death of Virginia.” We can perhaps imagine the painting’s special significance for him when we understand that its subject — a father killing his daughter, at her own request — hinges on the dishonor of being enslaved.

Guillaume Lethière, “The Death of Virginia,” circa 1823-1828. (Rebecca Vera-Martinez/ J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Versions of both paintings enjoyed great success when they were exhibited in Rome and London. But in Paris, tastes were changing, and by the 19th century’s second decade, romanticism was on the rise. Lethière’s neoclassical style began to fall out of favor.

Winning the 1819 inheritance case seems to have inspired Lethière to turn his attention back to the Caribbean, and in 1822 he painted one of his most audacious canvases — an enormous (approximately 11 by 7 feet) painting owned by the Musée du Panthéon National Haitien in Port-au-Prince. It shows two generals, one mixed-race and the other Black, swearing an oath to fight together for the freedom and independence of the people of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti).

Guillaume Lethière, “Oath of the Ancestors,” 1822. (Gérard Blot/Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien, Port-au-Prince)

After a risky and clandestine sea voyage, Lethière’s son personally delivered the painting to Haiti’s President Jean-Pierre Boyer in Port-au-Prince. Two years later, France’s Charles X grudgingly recognized Haiti — but only in return for an indemnity payment that would cripple the young nation for decades.

Unfortunately, the recent civil strife in Haiti has prevented the painting from traveling to the United States. Lethière himself intended the painting for a Haitian audience and, according to Bell, who has tastefully installed a reproduction of it in the exhibition, it “encapsulates Lethière’s fidelity to his place of origin.”

The Clark show immerses us in several decades of political tumult that continue to reverberate today. It has much to say about other French artists and writers with ties to the Caribbean. So it is much more than just a monographic exhibition. For all the stately arrangement of the Clark’s galleries and the superficial stiffness of Lethière’s neoclassical style, the exhibit is like a pinwheeling firecracker, blazing out light, knowledge and cultural energy, and deepening our understanding of a remarkable inheritance.

Guillaume Lethière Through Oct. 14 at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., and then at the Louvre in Paris from Nov. 13 through Feb. 17. clarkart.edu.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katsushika Hokusai ‘Yoshitsune’s Horse-Washing Falls at Yoshino in Yamato Province (Washu Yoshino Yoshitsune uma arai no taki),’ from the series ‘A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces (Shokoku taki meguri),’ circa 1832.

digitally enhanced

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

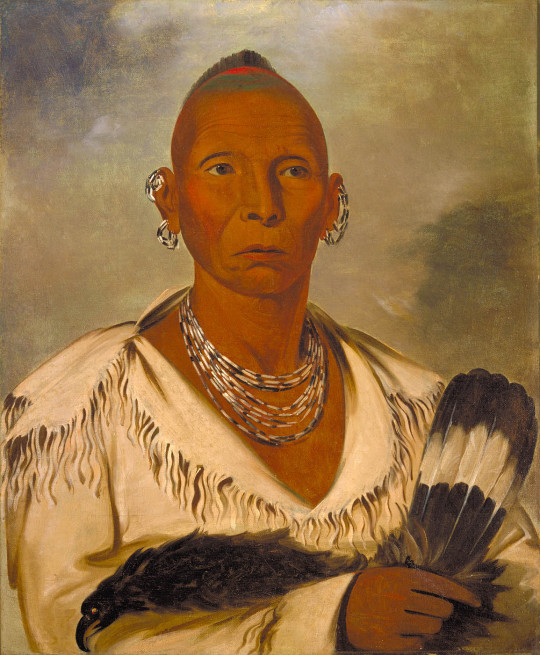

Father Black Hawk in Voodoo.

Who Was He: Indian name is Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, or Black Sparrow Hawk, and he was born in 1767 at Saukenuk, located along the Rock River. Black Hawk was born into the Thunder clan. He chose to have only one wife, As-she-we-qua, or Singing Bird, they had five children—two girls and three boys.

Black Hawk was a leader and warrior of the Sauk American Indian Nation. Then he was an appointed war chief. During the War of 1812, Black Hawk fought on the side of the British. Later he led a band of Sauk and Fox warriors against settlers in Illinois and present-day Wisconsin in the 1832. After the war, he was captured and taken to the eastern United States, he died in 1838 in what is now southeastern Iowa.

A Spiritualist Saint: According to some Spiritualists, Black Hawk is a Saint sent by God. It is said that when Black Hawk comes to help, God is right behind him. Anyone who is recognized as doing the work of the Creator is considered a saint, whether or not they have been officially canonized by the Catholic Church.

Mother Leafy Anderson (circa 1887–1927), medium and miracle healer, from the black spiritual churches is considered by some as one of the founders of the Spiritual Churches here in New Orleans. Black Hawk was a spirit that she used and probably was apart of her spiritual court. He first appeared to her in a vision in Chicago, where she lived before moving to New Orleans. She described him as “The Saint For The South,” while White Hawk, served the north.

After being brought to the spiritual churches in the south like where I'm at New Orleans we honor the Native American spirit of Black Hawk. Black Hawk is also considered a Voodoo saint, He is liked by many hoodoo practitioners as well. Because of exploitation by fake marketeers, the image of this Indian spirit guide has had a big influence in my opinion fake commercial hoodoo products.

The Indian is a significant part in the art and organization of the Mardi Gras Indians, as well.

Father Black Hawk, is what he was called because no one could pronounce his given name, so it was change to Father Black Hawk by fake Root Workers. (In my opinion if you don't know who Black Hawk is and understand why he is important in southern history then don't contact him)

Is He Apart Of Hoodoo Or Voodoo: No. Black Hawk is a spirit similar to St. Expedite meaning he is a conjured spirit and like Saint expedite he's called upon us to do certain things. But he is respected in the south and apart of our history.

What Is He Invoked For:

He is invoked for help with money and protection, justice, release from prison, to win court cases, and to overcome tragedy. He is the consummate warrior, and wants to fight your battles for you. They say he will come to those who have enough patience to sit still.

Setting Up His Altar: You need a statue or picture of him with his candle incense. But Do Not get a statue and place it in a bucket or a ceremonial bowl of sand or dirt a statue of an Indian warrior, along with a hatchet, tomahawk, and a spear. (Example above☝️) this is not hoodoo this is fake new age practice.

Give him his own space don't cram him in with others stuff on your altar.

Incense: It is usually a good idea to burn sage, cedar, or sweet grass or even Indian spirit incenses while petitioning Black Hawk.

Color: Red or White

Dislikes: Some people insist on giving him whiskey to “fire him up,” But this is a stereotype of a Indian man drunken on fire water. Disrespect.

Don't put lightning-struck wood on his altar is good (remember, he is of the Thunder clan)

Petitioning Him: put on some traditional Native American music or play a drum, rattle or flute. (I prefer a rattle while listening to native music)(see my post in rattles)

Offering: Offer him tobacco and food like beans, rice. Then recite one of the prayers to Black Hawk, afterwards talk to him and tell him what you need.

Days Of The Week: Wednesday, Sunday

Prayer:. Isaiah 62:6-9 KJV. Is good.

Prayer to Black Hawk: Oh Great Spirit, hear my voice, I believe in your power and your ability to defend me. In the name of all that is good, I ask for your help with this battle, my battle, with those who intend to harm me. Oh Powerful Spirit, you are the Great Chief, Help me with your Warrior medicine and guide me to safety with your Divine protection, shield me from the attacks of my enemies, with your bow and arrow, protect me from the evil thoughts and actions hurled towards me. With your hatchet, cut the chains and ropes that bind me. With your feathers, brush away the negative energy surrounding me. With your eyes, see that no jealousy and envy penetrates me. With your peace pipe, create harmony where there is discord. See that no evil befalls me. Fight the battle to destroy those who will harm me. Take revenge on my behalf and destroy the insurrection of the wicked. This prayer I ask not just for myself but for all of my relations past and present, and for those yet to come, Amen.

#Voodoo spirit#Blackhawk#New Orleans voodoo#Hoodoo spirit#Traditional hoodoo#Conjuring#Native American Spirit#like and/or reblog!#Southern magic#Prayer#Saint#Hoodoo Saint#Voodoo Saint#follow my blog#root work#rootwork questions

11 notes

·

View notes