#census of the poor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

john price who gets retired out, discharged when he gets some shrapnel in his knee, but he’s still a soldier at heart and needs to scratch some kind of itch. living out an idle retirement simply isn’t an option. with combat of any kind off the table, he picks up a random job as a census worker to occupy his time. government bureaucracy and paperwork, his old enemy—but better the devil you know, right?

it’s not a job he enjoys, as dull as it is, but if john price is anything, it’s not being a quitter. he’s thanking his stars that the season’s nearly done and wondering if he might be able to pitch in at the local carpentry shop when he’s sent to go meet a truant form-taker, some big house a bit of a ways out of town that hasn’t responded to the mail to fill out the census. big, old, and clearly falling apart with an overrun garden and a cracked drainpipe and a trampled, rotted fence.

he’s expecting a pensioner at the door given the state of the place, but when he knocks his big fist and the peeling door swings back, a pretty young thing is standing behind it. he explains why he’s there and the poor bird nearly bursts into tears with apologies. she’s so sorry for the display, she says, she’s just been very overwhelmed lately which is why she forgot to fill out the form and doesn’t mean to cry. the place used to be her gran’s, and apparently she’s in way over her head with the repairs and renovations.

john pokes his head in the door and takes a look at what he can see. bit of water and smoke damage on the walls, a bucket kicked under a leak, musty carpet, some stairs that could definitely use a good replacement on the planks. what he doesn’t already know how to fix, he knows how to figure out, and if push came to shove, he knows for sure he can handle wrangling a contractor better than the sweet woman before him; she’d probably get taken advantage of by some mean, leering electrician, and that just won’t do.

so he smiles at her, blue eyes crinkling up and mustache bristling against his cheeks as he leans back. tells her that they can do the paper census form now together and that he’ll keep her ‘out of trouble’ with the government in his books, and hell, afterwards he can show her how to fix that stubborn leak in the kitchen sink, and insists that the only repayment he needs is a cup of tea.

if he’s a bit hasty in checking off the ‘married’ box on the form when she’s busy fussing over the kettle and imagining the sound of tiny feet running up and down those stairs, well, that’s his business.

#captain john price#og post#cod mw2#price x reader#price x f!reader#call of duty#this was originally going to be way darker but i think it turned out rather sweet actually. life of its own#this was very much inspired by the latest make some noise episode i saw that prompt and went PRICE.

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Blood Meridian Headcanons Masterpost, order of appearance

Under the cut, see here for my collection of every physical description (or lack thereof) for each major character

The Kid

refuses to shave his shitty teenager mustache wispy silliness and is in denial about how unfinished it is (except for the one time he was kind of made to for a formal occasion)

never can really grow a proper beard, even in middle age, always patchy

bites his nails

light brown, mouse-colored hair

blue eyes

freckles

never had a proper haircut til Chihuahua due to childhood neglect

matted hair before and later after

5.1ft/1.55448m (childhood malnutrition)

Holden

abnormally unaffected by alcohol but consumes it anyway as a social thing

walking around naked was initially a result of him just being incalculably ancient (pre-clothes) and having no internalized sense of modesty due to this, but this soon became a power play similar to Lyndon Baines Johnson's behavior (look up LBJ Jumbo)

everyone's teeth are pretty disgusting, except for his, which are unusually pristine

he maintains his teeth with chewing-sticks and rinses with urine (both of these are ancient practices that are proven to be effective, albeit repulsive to modern sensibilities)

every item of clothing he wears is tailored (otherwise, how would anything fit him?), and his footwear is custom-made (meaning they have distinct lefts and rights to begin with, unlike many premade and military-issued footwear at the time, which had to be broken in and developed lefts and rights over time being worn)

files his nails meticulously and often, keeping them uniformly oval

has gone by the forenames Abernathy and William at times

knows classical Latin not just in the phrases he uses but to the extent of fluency, as well as classical Greek and Hebrew (common scholarly pursuits for men of means at the time)

red-pink eyes

Toadvine

surprisingly low alcohol tolerance

limited mobility in the areas of his face near where he was branded, the skin just doesn't stretch, resulting in limited expression

the sides of his head are not completely flat, he has lumpy bits of flesh and cartilage where his ears were unevenly cut and burn scars from when the wounds were cauterized

due to the burns from cauterizing, his hearing is slightly affected, but generally clear, and he makes up for it by being observant to the slightest sound

he only grew his hair long after his ears were docked, more to push it back and jumpscare people with his ear stumps than out of any insecurity (ego death long ago)

from Kentucky (the surname Toadvine is most common there, and he has canonically never seen the sea until the chapter where he visits California)

black-brown eyes

6.1ft/1.85928m

born 1821

Glanton

files his nails carelessly and somewhat square just so they don't get long and break

knee problems that he just tries to tough out, but he massages them at night when he thinks no one sees

Irish ancestry (his surname is most common in the US as well as Ireland, where it is rare and held only by Catholics, according to census data)

from Georgia (his surname is most common there)

long eyelashes

5.5ft/1.6764m

born 1804

White Jackson

Cajun, looks down on Creoles of color, valuing his culture higher and fearing being lumped in with Creoles of color (Cajuns in Louisiana are Creole, but not all Creoles are Cajun, Cajuns are a White, French-speaking ethnic group descended from settlers in Acadia, Canada from primarily West-Central France who were forced out of Canada by the British, many eventually resettling in Louisiana)

his name at birth was Jean (French variant of John), but others say it as John

his family was poor, and he was looked down on for being Cajun

his aggressive racism is a result of deep insecurity and a need to feel superior (NOT JUSTIFYING, JUST THEORIZING MOTIVATION)

from Louisiana (his surname was most frequent in the US there according to 1880 census data)

thick, dark brown hair

medium brown eyes

5.7ft/1.73736m

born 1824

Black Jackson

self-emancipated at a very young age by escaping to the West

he was given a stupid, humiliating literary name (common at the time) and was unimaginative, so he changed it for John

gave himself his surname too, ironically out of admiration for Andrew Jackson, who he knew little about but he had heard propaganda about him and did not know Jackson had a plantation, having heard of him as a rugged man of the people from the frontier and the scourge of Natives, nothing more

you just know he was ashy and unmoisturized and didn't know how to take care of his hair, so he just cut it short

resents Christianity (see: his drunken threat to shoot the ass off of Jesus Christ) due to it being used as justification of slavery, and the Bible being used to sell the idea that being Black was the mark of Cain or something

never talks about his past, as it would just be used as ammunition against him

illiterate (as per Southern law), too proud to admit it, let alone ask anyone to teach him

whip scars, though not as severe as some well-known images

5.8ft/1.76784m

born 1828

Bathcat

surprisingly low alcohol tolerance too

cuts the whites of his nails with a knife, which is careful and practiced, never bleeds from it

bi, see that one scene where he was asleep with his arm around one of the musicians

ear necklace made Toadvine flinch just slightly before he could catch himself when they first met

Bathcat, noticing Toadvine's lack of ears, torments him with it initially but gives up when Toadvine shows no reaction after the first

the offense he was sent to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania/Lutruwita) for was S/A or similar

his hand injury is from unsafe working conditions when performing unpaid prison labor

his eye injury is the result of violence from another inmate

realized he was into men too in prison and just saw it as a natural result of separation from women

tonedeaf (cannot distinguish musical notes by ear or repeat/carry a tune)

knows some Welsh from his childhood, mostly songs and expressions

naturally thin, blond hair

grey-blue eyes

5.7ft/1.73736m

born 1807

sent to Van Diemen's Land 1829

Tobin

raised as a charity case by the Church rather than by family at times

former choir boy, still sings and hums when he thinks no one can hear

quit seminary due to struggling with celibacy and certain moral things justified in the Bible that seem contradictory to restrictions for Priests, as well as the Bible being used as justification for slavery

closest thing Black Jackson has to a friend in the gang

bad back

after he disappeared from the narrative, he returned to ministry

he no longer believed after everything he had seen, but wanted to provide aid and comfort regardless

from Massachusetts (his name is most common there in the US)

greying, balding ginger hair

blue eyes

needs reading glasses

5.8ft/1.76784m

born 1803

David Brown

from what became Arkansas (canonically never saw an ocean before he went to California)

blond

hazel eyes

nearsighted (things that are further are less clear)

5.6ft/1.70688m

born 1818

James Robert Bell

severe Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, his older brother has a more mild form which is visible in subtle features but not significantly disabling, their mother's alcoholism worsened by the time she had James

his mother died as a complication of alcoholism

his consumption of fecal matter is a result of having been starved in the past (see: Blanche Monnier)

his brother trimmed his nails for him so he wouldn't hurt himself or others

Holden did not, but watched Bell at all times for entertainment, as Holden did not sleep, and would physically prevent severe harm (to prolong his entertainment)

muscular atrophy due to being kept in a cage, resulting in posture and movement difficulties, as well as exhaustion (see: the "Genie" child neglect case)

his being drawn to the river and to fire was not mere curiosity but a desire for death

thin, dark brown hair

born 1830

#blood meridian#blood meridian or the evening redness in the west#the kid#the kid blood meridian#judge holden#the judge#john joel glanton#toadvine#louis toadvine#cormac mccarthy#davy brown#david brown#white jackson#black jackson#the jacksons blood meridian#ben tobin#benjamin tobin#tobin#james robert bell#bathcat#the vandiemenlander

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Held off on this because it's becoming disheartening to see a lot of the BoB Tumblr research reposted or remastered with dubious credit, but at the end of the day I really want people to know about Norma Jean Darland Grant, Chuck Grant's wife.

Norma, I don't even know where to start with you. As I dive into the records to find people and make their stories known, nobody has had so much tragedy and absolutely bizarre circumstances revolving around their lives as you. I've never wanted to reach back in time and give someone a hug so badly as I do with this lady. I hope Chuck was your sunshine, I hope you found happiness, I wish you were not the victim of circumstances beyond your control.

Norma was born in Mahaska. Co, Iowa on February 11, 1923. Her father George was a farmer. Her mother Mable Moody Darland , was the daughter of a farmer. She had an older brother Donald. In 1925 they moved to Newton, Iowa, then ended up in Detroit.

Full stop, because George Darland...holy shit did this guy get into everything. And I do mean unbelievable non-stop news. In 1920 George was tearing down a cow barn with his father in law, barn collapses, father in law gets scalped. They have to take William Moody to town on a stretcher, George has a broken shoulder and helps carry him, Moody ends up with 21 stitches and no broken bones. In 1921 George , recently recovered from pneumonia, pulls some Oregon Trail shit and tries to get to his corn farming island in the river when the ferry rope broke, wagon fell off the barge, his team drowns and he almost drowns under one of them. Even the paper is like "damn, this is the unluckiest guy in Iowa." Oh...it's only 1921. Just wait.

He also got into a fight with some guy in town and got busted up earlier that summer, something about a cheese knife and billiard cue and- no- the article does not explain that. Oh, and don't forget the spreading viper he decided to catch in September. Throw in a modest sprained ankle in 1922. There are a few years without news, and I am sure it's just because it's not available to us a 100 years later, yet.

Mable Moody Darland dies in Detroit in 1929, of diffuse peritonitis, after what appears to have been a two year stint in the city to work at Braggs Mfg. After Mable dies, George goes home and the kids are at his parents in Barnes City while he heads to Des Moines to work for his brother. In 1930 Norma Jean writes to Santa and breaks my heart.

However, earlier that year in 1930 George gets involved in the B.O. Darland Grocery Store bullshit and gets shot. Here's the story.: There is a cop, William J. Aiken, who lives a few houses down from George's brother Bert and his family. George's brother Bert has a grocery store on the corner. George is working for him even though the census says he's a mechanic. Mrs. Aiken might be getting more than groceries from Darland's Grocery store. Husband goes to drag her out of the store, punches Bert, draws a gun, gun goes off and George is shot in the leg, then Aiken kicks the shit out of his wife all while Aiken's partner sits in the car and doesn't watch. Trial ensues, Aiken says he used the gun as a club to defend himself and doesn't know who's finger pulled the trigger. Front page Des Moines news, complete with maps! The Judge dismissed the case against Aiken, but Aiken loses his job as detective, and is also later arrested for bootlegging. Wild Norma has not one, but two, men in her life who get shot for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. This poor girl.

It seems George rebounded and found a new Mabel to marry, Mabel Kerr in 1931. Mabel #2's husband Jack, a coal miner who had been working the mines since he was orphaned at 9, was arrested for bootlegging. That left her and their 6 children out of luck as Jack was sentenced to 3 months in jail and a fine of $300. Well, along came the unluckiest guy in Iowa and they were married at her sister's house in Raritan, Illinois in 1931. (If you think Raritan sounds familiar it's because Raritan, NJ was home of Basilone. The Raritan River was where the Nixon Nitration Works was located on. People from this area in NJ left in the 1850s to go start a town with NJ names in Illinois just to fuck with me.)

In 1932 in Tracey, Iowa the schoolhouse George and family are living in, burns down. How much family? Unclear.

1933 rolls around. In Des Moines, Darland's Grocery-- Bert specifically--gets robbed at gunpoint March 16, for $15, milk, sugar, butter and eggs. The same day Jack Kerr visits his family in Albia. George dies March 30, 1933 in Oskaloosa?(maybe?) and I have no idea how. Mabel #2 moves on an remarries in 1938, and her Kerr kids go with her and the Darland kids eventually go west with the Darland family to LA. Norma lives with her aunt Mrytle Darland Morrow and goes to school in Santa Monica. Bert Darland moves west too, restarts the grocery business out there and sells it a few times. He avoids being shot, but a poodle did bite him at one point and couldn't be found so Bert probably got a lot of painful Rabies shots.

George is buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery where Mable #1 is, along with loads of Mable #2 family. There is a death notice in the paper, no obit. 'What Killed George Darland' haunts me because this man survived so much and there is no news about what finally got him.

Back to Norma . She goes to Santa Monica High School. Joins the World Friendship Club and Riding Club. In 1938 is at a party celebrating the engagement of her cousin Thelma. She joins the marines in 1943 and by war's end is a corporal. She is stationed at Miramar in San Diego, muster roll says she is with the aviation women's reserve squadron. In 1945 is maid of honor for a fellow marine friend. On her marriage certificate in Nov 1946 she lists her residence as Santa Monica.

How does she meet Chuck Grant who at this point has been out of the hospital a year and is dealing with paralysis and speech issues? Another burning question. However in November 1946 they go to Vegas with Chuck's friend Keith Morgan and his wife and get married. They move to San Diego where she becomes a cashier at the Naval Training Station. 40 hours a week as a payroll clerk. Chuck is used as an example of Navy efforts to assist wounded veterans in a newspaper article, possibly because Norma is working there. They have their first son Dan in 1947 and Charles Jr in 1951.

Then in September 8, 1954, Norma ODs. 7am Chuck goes to the bedroom and finds her, takes the kids to a friends house in Clairemont, and returns to call the cops at 9:15 am and answer questions. He told the detective he wanted to spare the kids the details of their mother's death and didn't want them present from the inquiry. It is ultimately ruled a suicide by the coroner, overdose by barbiturates.

Norma Jean Darland Grant was cremated and is buried in Rosecrans military cemetery in San Diego under her maiden name. I don't know if Chuck just signed off on paperwork and didn't correct it or what. The burial form stipulates there are interment rights in her grave but he ends up buried in Forest Lawn in LA instead.

Norma was 31 years old. From what we can tell, Chuck never remarried.

Thank you to @noneedtoamputate for caring about Chuck and his family and going on this journey of research into the Darlands. For every fact we unearth, we still gain no insight into Chuck's personality. But we've earned those Oregon Trail T-Shirts for learning about George. Thank you for listening to my screaming in the inbox because every. damned. person in Chuck Grant's orbit has some truly messed up shit in their lives. This post is a summary of months of research that has been interesting for sure.

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you restore the ‘Hazbin Hotel’ Wikipedia page ‘That’s Entertainment (Hazbin Hotel)’ on Wikipedia? The same person keeps blanking it.

Hi, thank you for your question! I appreciate the request - I’m actually really flattered! - but I’m not going to do that at this moment. This is actually a very interesting microcosm of Wikipedia backdoor activities and we can use it as a learning opportunity.

Background: anon said the same person (not the same person) keeps “blanking” the page and that’s not entirely true. People have turned into it a redirection page or a redirect (let me know if the terminology is too technical). A redirect is one of the series of pipes that keeps Wikipedia moving smoothly; it would be a massive time waste and hassle to have to enter every article title perfectly to search for it. This is also helpful when you have multiple names for the same topic. Okay great now we all know what a redirect is.

Timeline: on 23 July 2023, someone made a redirect for the Hazbin Hotel pilot.

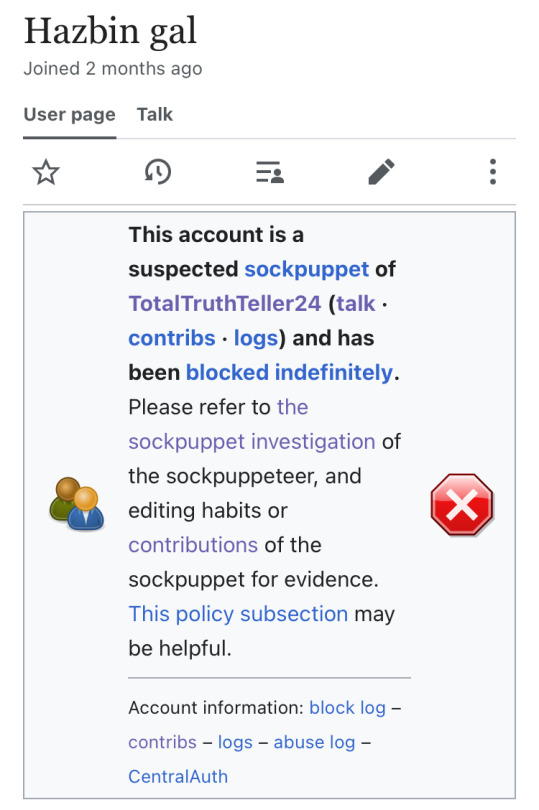

Then on 6 November 2024, as if I didn’t have enough problems, someone turns that redirection page into a standalone article and adds a massive increase in characters to go with it. This page is user Hazbin girl. Remember this one.

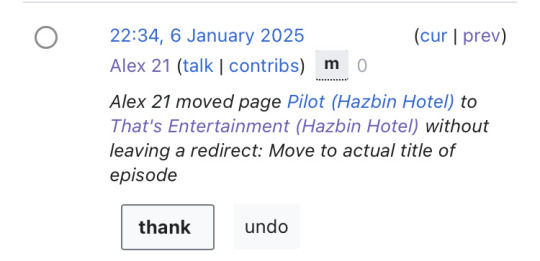

And we all sort of putter around improving that until 6 January 2024, when someone redirects the page, which is currently using the title Pilot (Hazbin Hotel) to That’s Entertainment (Hazbin Hotel).

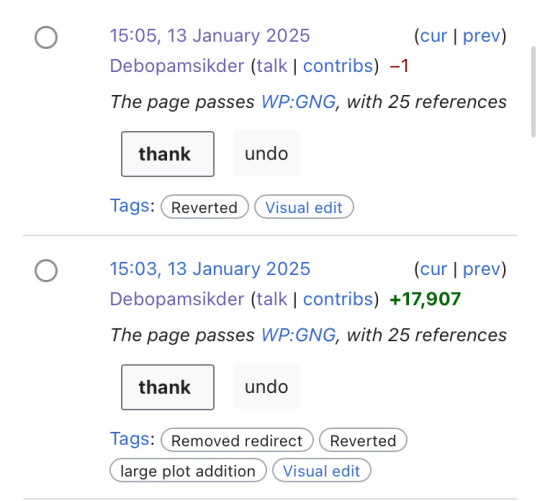

They also do a kind of sloppy job (see the tag about having not left a redirect). People add meme categories to it a few times, they get removed, and the activity goes back and forth until one of the admins gets fed up and reverts it back to a redirect to Hazbin Hotel on 13 January 2025. And I see the logic behind this - there is very little that is stated in the episode article that isn’t already stated in the show’s article. Between production, development, the actual episode summary, and the references, having an article for every single episode would be a massive reduplication of efforts. Wikipedia is also not a fandom site - what’s notable to fans of the show is not notable per our general notability guidelines. Some episodes get that but at this point, I don’t think the pilot of HH cuts the mustard. So the redirect from 13 January stands.

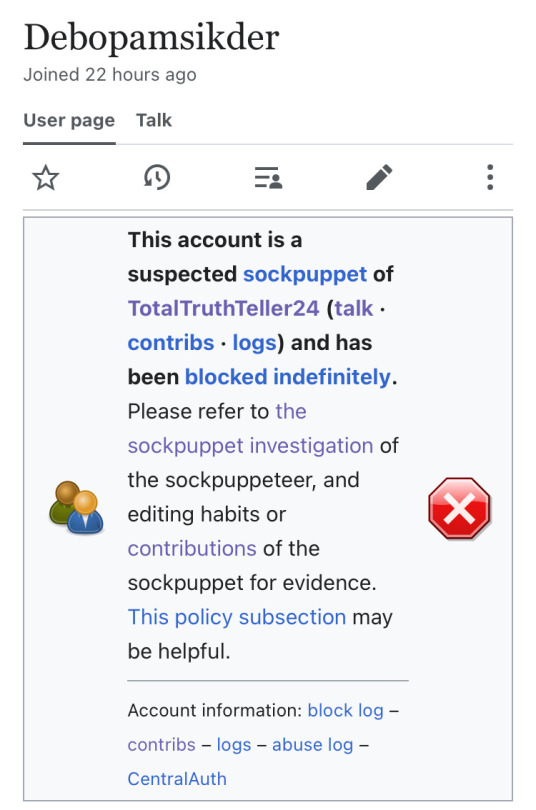

Then on the same day, someone reverts the redirect to restore the standalone article. That person is Debopamsikder. Also remember this name.

It’s fine to have a difference of opinion as to what should be on Wikipedia. We can work that out with community census-building which is a beautiful thing.

Here’s what’s not fine: sockpuppetry.

Shortly after the redirect is undone, both Debopamsikder, whose account had been created on 13 January 2025, and our old friend Hazbin girl get suspected of being sock puppets and get blocked. More specifically, they are suspected of being sockpuppets for a user who was blocked back in 2017 for, get this, creating multiple accounts to argue for articles about their favourite franchises. You can check out the original sockpuppetry investigation here

Conclusion: I’m not sure if this is the same person behind TotalTruthTeller24, although that would be wild, but I think it’s extremely poor form to ask me to wade into something like this and haha yeah man can you just fix it there’s no larger issue happening ahhahaha nooooooo don’t use critical thinking skills ur so sexy, someone keeps blanking the page that’s it I prommy. That’s simply not true, and now I have spent over 40 minutes digging into this because you want more fandom cruft for your favourite show to repeat information that’s already present or would get immediately removed for being non-notable to anyone but a hardcore fan. No thank you. Go write something on the fandom wiki and be done with it.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

"if you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything"

the poverty line is set so low that many people living in difficult conditions are actually not considered 'poor' by the government?

Rs 1,632 per month for rural areas

Rs 1,944 per month for urban areas

This means if someone earns Rs. 55 per day, they are not considered poor!

the finance ministry is blind to how much indians actually earn and how much is needed to actually survive- remember, we haven't had the census yet, so no data available.

this govt is lying blatantly at this point and people are cheering for it.

#india needs a census#we need real data.#this makes no sense at all#most of the country is struggling but yay!! we need to dig for temples!!#baby your religion is not in danger#your entire livelihood will be stolen by them in the name of god#india#desiblr#hindublr#hindutva

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Argentina's poverty rate fell sharply in the second half of 2024, according to official data released this week, marking a major milestone for President Javier Milei's sweeping economic reforms.

According to the country's official statistics agency, the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC), the poverty rate fell to 38.1 percent between July 2024 and December 2024—down nearly 15 percentage points from the first half of the year. Household poverty also declined by 13.9 percentage points, hitting 28.6 percent. And extreme poverty was cut by more than half, falling from 18.1 percent to 8.2 percent.

It's a major turnaround from the beginning of Milei's presidency. When he took office in December 2023, he inherited a poverty rate of 41.7 percent, which quickly surged to 53 percent as his administration launched a "shock therapy" program to end Argentina's economic misery.

One of the biggest drivers behind the poverty decline is the sharp drop in inflation. Annual inflation, which reached 276.2 percent a year ago—one of the highest in the world—dropped to 66.9 percent last month. Monthly inflation has also dropped, from 25.5 percent in December to just 2.4 percent in March.

"These figures reflect the failure of past policies, which plunged millions of Argentines into precarious conditions while promoting the idea of helping the poor, even as poverty continued to increase," Milei's office said in a statement following the release of the INDEC report. "The current administration has shown that the path of economic freedom and fiscal responsibility is the way to reduce poverty in the long term."

In other words, Milei's bet on free market reforms is starting to pay off.

It's worth remembering the situation he walked into. "Milei inherited a country suffering from more than 200% inflation in 2023, 40% poverty, a fiscal and quasi-fiscal deficit of 15% of GDP, a huge and growing public debt, a bankrupt central bank, and a shrinking economy," writes Ian Vásquez of the Cato Institute.

In response, Milei promised a radical shift in Argentina's economic model. His government slashed government spending, eliminated price controls, devalued the peso, cut subsidies, suspended public works, and laid off thousands of government workers. The changes weren't popular, but they were necessary. And now, the numbers are catching up.

The economy is growing again. Gross domestic product grew in the last two quarters. The gap between the black-market dollar and the official rate has narrowed. Rents have fallen and the housing supply has increased since rent control laws were scrapped. Meanwhile, investor interest in Argentina is beginning to return, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is in talks with Milei's government over a new program. The IMF projects a 5 percent growth for Argentina in 2025.

Still, challenges remain. Despite the improvement, over 11 million Argentines are still living in poverty, with 2.5 million facing extreme poverty. And more than half of all children ages 14 and under in Argentina are poor.

Milei has consistently said that his adjustment plan would have a "negative impact on the level of activity, employment, real wages, and the number of poor and indigent people," before it started to work. Things are finally starting to get better and at the right time.

With midterm elections coming in October, Milei's party, La Libertad Avanza, has an opportunity to expand its influence. Right now, the party holds only a small share of congressional seats. But with half of the lower house and a third of the Senate up for grabs, the growing economic momentum could give Milei the support he needs to deepen and accelerate his reforms.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Accumulation by Dispossession, Trump Style

How Trump turned the machinery of the state into a tool of extraction—and why naming the theft is the first step toward repair.

James B. Greenberg

Jun 25, 2025

In an age where corruption is sold as competence and cruelty as clarity, the line between governance and grift has grown dangerously thin. Under Trump, that line didn’t blur—it vanished. What emerged wasn’t just mismanagement or ideological extremism, but a systematic mode of extraction, where the state itself was turned into an engine of enrichment for the few.

This wasn’t new. The mechanics were already in place. But Trump stripped them of pretense. What took shape under his leadership was a raw and visible form of what might best be called accumulation by dispossession—not through innovation, but by seizure. Through privatization, deregulation, defunding, and destabilization, wealth was moved upward by force of policy.

The pandemic revealed this with brutal clarity. Relief funds intended to cushion the blow for workers and small businesses were rerouted to major corporations and political allies. Contracts for protective equipment flowed to the connected, not the competent. Oversight mechanisms were sidelined, and accountability dissolved. What should have been a moment of collective care became a marketplace of opportunity for those already positioned to profit.

Or take public lands. Under Trump, millions of acres were opened to extraction—drilling, mining, grazing—not for public benefit, but for private gain. Environmental protections were stripped, tribal sovereignty undermined, and sacred sites desecrated in the name of “freedom.” This wasn’t policy in the traditional sense—it was liquidation. What belonged to all was transferred to a few.

Even immigration policy was part of this calculus. Migrants were not only criminalized; they were commodified. Detention contracts, surveillance technologies, biometric databases, border walls—all became opportunities for profit. The state’s power to detain, sort, and exclude was outsourced and monetized. What looked like enforcement was, in fact, extraction.

What links these moves is not chaos, but coherence. Degrade the commons, discredit public institutions, and redirect the flow of value toward private interests. This wasn’t the dismantling of the state. It was the weaponization of its infrastructure for dispossession. A state repurposed not to serve, but to siphon.

But the logic of dispossession goes deeper than land and money. It erodes time, possibility, and the basic scaffolding of democratic life. Under Trump, trust in public systems was not merely lost—it was actively dismantled. Public education was politicized. The census was manipulated. The Postal Service was hobbled in plain sight. These weren’t isolated failures. They were deliberate efforts to fracture the systems that sustain social reproduction and civic belonging.

This form of rule draws from an older logic. What was once called primitive accumulation—the seizure of land, labor, and resources in the formation of early capitalism—now plays out inside the borders of established democracies. It no longer requires conquest abroad. It cannibalizes institutions at home. The tools are legal, bureaucratic, and digital. The violence is slower, but no less real.

Today, dispossession moves through zoning laws and budget line items, through the privatization of housing, water, and care. It travels through digital networks—data harvested, identities tracked, benefits denied by algorithm. It is ecological, too: extractive industries strip land and poison water while vulnerable communities bear the cost. Climate denial is not ignorance; it is strategy. A way to prolong profit at the expense of planetary survival.

All of this was wrapped in a populist script—a claim to speak for “the forgotten.” But the real beneficiaries were never the working poor. The tax cuts went to the wealthy. The deregulation favored polluters and profiteers. The rhetoric masked the fact that what was being restored was not dignity, but dominion—the power of wealth to go unchallenged.

And yet, dispossession is never just about theft. It is also about narrative. Trump didn’t just strip resources—he rewrote the moral economy. He told people they had been wronged, then sold them a performance of revenge: against immigrants, against environmentalists, against the very idea of collective responsibility. Extraction was reframed as justice. Looting as loyalty.

What was taken wasn’t only tangible. It was temporal. The future was foreclosed for many—through student debt, housing precarity, degraded schools, and unsafe work. This is how accumulation works now: not by creating wealth, but by extracting life from the margins—one hour, one service, one body at a time.

This is why the Trump era cannot be dismissed as mere chaos. It revealed something deeper: a governance model that no longer aims to build, only to strip; that sees care as waste and solidarity as threat. It exposed the machinery of extraction that had been running for decades—but now without shame, without brakes, without apology.

Yet even in the wreckage, the story isn’t over. Dispossession often generates its opposite: solidarity. When people lose what was promised—land, labor, dignity—they look to each other. Mutual aid networks surged in the pandemic. Teachers, nurses, transit workers, and tenants organized. The commons is not gone. It is damaged. But it can be rebuilt—not by nostalgia, but by design.

Reclaiming what has been taken will not be easy. The machinery of extraction is deeply embedded. But history teaches that even the most entrenched systems crack when the stories upholding them collapse. What we need now are new stories—grounded in dignity, interdependence, and a future not for sale.

Because what was lost in the Trump years wasn’t just public money. It was the idea that government could be something other than a shell game for the powerful. Recovering that idea will take more than elections. It will require repair—material, institutional, and moral.

And that begins by naming what happened for what it was: not just corruption or chaos, but a calculated project of dispossession. And by insisting, again, that the public belongs to the people—not to those who see it only as something to plunder.

Suggested Readings

Harvey, David. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Greenberg, James B., and Thomas K. Park, eds. Terrestrial Transformations: Political Ecology, Climate, and the Remaking of Planet Earth. New York: Lexington Books, 2023.

Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019.

Pulido, Laura. Environmentalism and Economic Justice: Two Chicano Struggles in the Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996.

Sassen, Saskia. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014.

Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State:

How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Streeck, Wolfgang. Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism. London: Verso, 2014.

Vélez-Ibáñez, Carlos G. The Rise of Necro/Narco-Citizenship: Belonging and Dying in the National Borderlands. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2025.

Weizman, Eyal. The Least of All Possible Evils: Humanitarian Violence from Arendt to Gaza. London: Verso, 2012.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

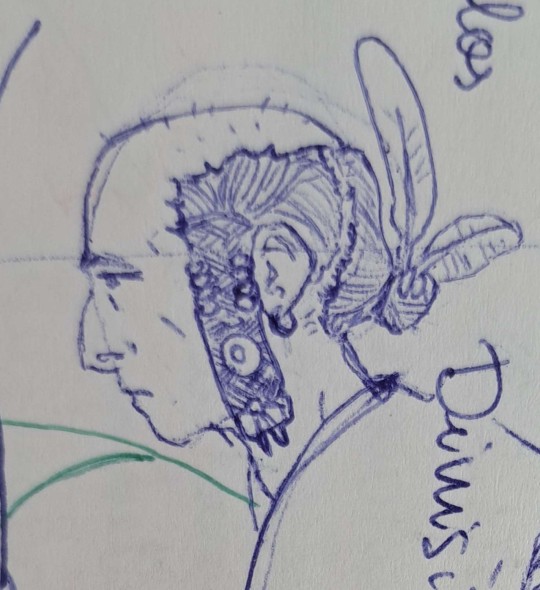

Sketch of common people from the Twisted Islands. Left to right: llama herder, guild apprentice, fisherman, guild militia man.

The archipellago is mostly made up of rocky atolls, coral reefs and small islands mostly inhabited by shrubs, migratory birds, seals and rodents. (Also llamas introduced by humans).

These poor ecosystems are not suited for large human population yet many people are attracted to the islands because of it's high portal activity (you can read about the magic system here, but I will later do another post about the "mages" of the islands). People from the islands come from many regions of the eastern seaway but mainly belong to the Iliryi seafaring etnithity, and most people speak their language and practice their religion centered around the sea and the portals.

For a long time the islands were not united but each ruled by a "monastic guild" wich investigated portals and lead rituals, divination and offers using them. Certain branches of the guilds opperated as beaurocrats, port tax collecters and managers, defence of the islands and barbers.

The importance of haircuts in the islands stems from their obsession with physical and spiritual cleanliness. People in the islands live in comunal spaces and often travelled between them, so they were very prone to epidemics. Most islands enforce quarantines, daily ritual bathing and frequent body inspections and shaving done by guild officials. This prevents lice from spreading but quickly became a sort of weekly census. Non guild people such as fishermen, divers, some sailors or shepperds shave their hair completely while guild members leave certain locks of hair wich they braid according to their guild branch and status within it.

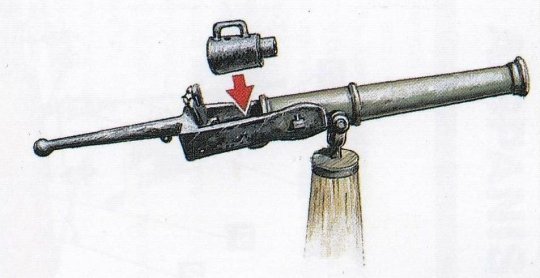

After the unification of the islands, guilds were standardized into a single secretive entity. Their biggest secret is their use of portals for trade (wich requires years of training and deep knowledge of geometry) and their firearms. While people in the western continent are starting to use iron or bamboo handcannons and bronze mortars, the island's militia have precise matchlocks and powerful breech loading swivel cannons.

Most islands have rocky shores and only one suitable well defended port, so deploying large armies on the islands is basically imposible. These fortified atolls can hold a siege for years while reciving food and suplies from other islands vía portals and even keep making profits by trading.

For an object to be transported between to portals, the portal needs to be opened/primed on the two sides, so many small trading outpost have been set in foreign lands, sometimes willingly by local population and other times by force, wich creates tension with the twisted island's diasphora in other nations.

#fantasy worldbuilding#worldbuilding#fantasy art#art#concept art#fantasy#encounters in the frontier#yzegem#worldbuilding project#twisted islands#magic system#culture#illustration#civilization#magic#mage

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is so horrific.

———————

I have been following Siro’s story for 30 years, ever since I went to interview her and four other rural midwives in India’s Bihar state in 1996.

They had been identified by a non-governmental organisation as being behind the murder of baby girls in the district of Katihar where, under pressure from the newborns’ parents, they were killing them by feeding them chemicals or simply wringing their necks.

Hakiya Devi, the eldest of the midwives I interviewed, told me at the time she had killed 12 or 13 babies. Another midwife, Dharmi Devi, admitted to killing more - at least 15-20.

It is impossible to ascertain the exact number of babies they may have killed, given the way the data was gathered.

But they featured in a report published in 1995 by an NGO, based on interviews with them and 30 other midwives. If the report’s estimates are accurate, more than 1,000 baby girls were being murdered every year in one district, by just 35 midwives. According to the report, Bihar at the time had more than half a million midwives. And infanticide was not limited to Bihar.

Refusing orders, Hakiya said, was almost never an option for a midwife.

“The family would lock the room and stand behind us with sticks,” says Hakiya Devi. “They’d say: ‘We already have four-five daughters. This will wipe out our wealth. Once we give dowry for our girls, we will starve to death. Now, another girl has been born. Kill her.’

“Who could we complain to? We were scared. If we went to the police, we’d get into trouble. If we spoke up, people would threaten us."

The role of a midwife in rural India is rooted in tradition, and burdened by the harsh realities of poverty and caste. The midwives I interviewed belonged to the lower castes in India’s caste hierarchy. Midwifery was a profession passed on to them by mothers and grandmothers. They lived in a world where refusing orders of powerful, upper-caste families was unthinkable.

The midwife could be promised a sari, a sack of grain or a small amount of money for killing a baby. Sometimes even that was not paid. The birth of a boy earned them about 1,000 rupees. The birth of a girl earned them half.

The reason for this imbalance was steeped in India’s custom of giving a dowry, they explained. Though the custom was outlawed in 1961, it still held strong in the 90s - and indeed continues into the present day.

A dowry can be anything - cash, jewellery, utensils. But for many families, rich or poor, it is the condition of a wedding. And this is what, for many, still makes the birth of a son a celebration and the birth of a daughter a financial burden.

Siro Devi, the only midwife of those I interviewed who is still alive, used a vivid physical image to explain this disparity in status.

“A boy is above the ground - higher. A daughter is below - lower. Whether a son feeds or takes care of his parents or not, they all want a boy.”

The preference for sons can be seen in India’s national-level data. Its most recent census, in 2011, recorded a ratio of 943 women to every 1,000 men. This is nevertheless an improvement on the 1990s - in the 1991 census, the ratio was 927/1,000.

By the time I finished filming the midwives’ testimonies in 1996, a small, silent change had begun. The midwives who once carried out these orders had started to resist.

This change was instigated by Anila Kumari, a social worker who supported women in the villages around Katihar, and was dedicated to addressing the root causes of these killings.

Anila’s approach was simple. She asked the midwives, “Would you do this to your own daughter?”

Her question apparently pierced years of rationalisation and denial. The midwives got some financial help via community groups and gradually the cycle of violence was interrupted.

Siro, speaking to me in 2007, explained the change.

“Now, whoever asks me to kill, I tell them: ‘Look, give me the child, and I’ll take her to Anila Madam.’”

The midwives rescued at least five newborn girls from families who wanted them killed or had already abandoned them.

One child died, but Anila arranged for the other four to be sent to Bihar’s capital, Patna, to an NGO which organised their adoption.

The story could have ended there. But I wanted to know what had become of those girls who were adopted, and where life had taken them.

Anila’s records were meticulous but they had few details about post-adoption.

Working with a BBC World Service team, I got in touch with a woman called Medha Shekar who, back in the 90s, was researching infanticide in Bihar when the babies rescued by Anila and the midwives began arriving at her NGO. Remarkably, Medha was still in touch with a young woman who, she believed, was one of these rescued babies.

Anila told me that she had given all the girls saved by the midwives the prefix “Kosi” before their name, a homage to the Kosi river in Bihar. Medha remembered that Monica had been named with this “Kosi” prefix before her adoption.

The adoption agency would not let us look at Monica’s records, so we can never be sure. But her origins in Patna, her approximate date of birth and the prefix “Kosi” all point to the same conclusion: Monica is, in all probability, one of the five babies rescued by Anila and the midwives.

When I went to meet her at her parents’ home some 2,000km (1,242 miles) away in Pune, she said she felt lucky to have been adopted by a loving family.

“This is my definition of a normal happy life and I am living it,” she said.

Monica knew that she had been adopted from Bihar. But we were able to give her more details about the circumstances of her adoption.

Earlier this year, Monica travelled to Bihar to meet Anila and Siro.

Monica saw herself as the culmination of years of hard work by Anila and the midwives.

“Someone prepares a lot to do well in an exam. I feel like that. They did the hard work and now they’re so curious to meet the result… So definitely, I would like to meet them.”

Anila wept tears of joy when she met Monica. But Siro’s response felt different.

She sobbed hard, holding Monica close and combing through her hair.

“I took you [to the orphanage] to save your life… My soul is at peace now,” she told her.

But when, a couple of days later, I attempted to press Siro about her reaction, she resisted further scrutiny.

“What happened in the past is in the past,” she said.

But what is not in the past is the prejudice some still hold against baby girls.

Reports of infanticide are now relatively rare, but sex-selective abortion remains common, despite being illegal since 1994.

If one listens to the traditional folk songs sung during childbirth, known as Sohar, in parts of north India, joy is reserved for the birth of a male child. Even in 2024, it is an effort to get local singers to change the lyrics so that the song celebrates the birth of a girl.

While we were filming our documentary, two baby girls were discovered abandoned in Katihar - one in bushes, another at the roadside, just a few hours old. One later died. The other was put up for adoption.

Before Monica left Bihar, she visited this baby in the Special Adoption Centre in Katihar.

She says she was haunted by the realisation that though female infanticide may have been reduced, abandoning baby girls continues.

“This is a cycle… I can see myself there a few years ago, and now again there’s some girl similar to me.”

But there were to be happier similarities too.

The baby has now been adopted by a couple in the north-eastern state of Assam. They have named her Edha, which means happiness.

“We saw her photo, and we were clear - a baby once abandoned cannot be abandoned twice,” says her adoptive father Gaurav, an officer in the Indian air force.

Every few weeks Gaurav sends me a video of Edha's latest antics. I sometimes share them with Monica.

Looking back, the 30 years spent on this story were never just about the past. It was about confronting uncomfortable truths. The past cannot be undone, but it can be transformed.

And in that transformation, there is hope.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some call women's segregation into low-paid work a choice. But it's a funny kind of choice when there is no realistic option other than the children not being cared for and the housework not getting done. In any case, fifty year's worth of US census data has proven that when women join an industry in high numbers, that industry attracts lower pay and loses 'prestige’, suggesting that low-paid work chooses women rather than the other way around. This choice-that-isn't-a-choice is making women poor…Women earn between 31% and 75% less than men over their lifetimes.

This all leaves women facing extreme poverty in their old age, in part because they simply can't afford to save for it. - Caroline Criado Perez (Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men)

#womanhood#feminism#low paid wok#patriarchy#sexism#sex based oppression#Caroline Criado Perez#invisible women#Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men#worker wages#glass ceiling#pay equality#this is why we need feminism#working women#radical feminism#dibs

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

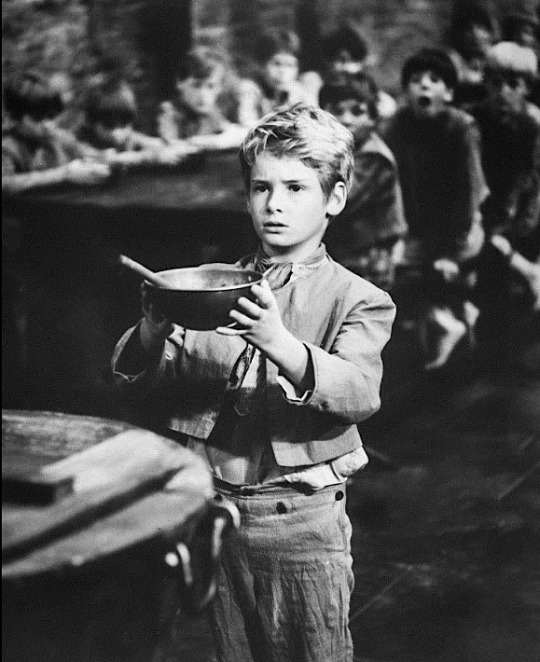

Social Change in the British Industrial Revolution

The British Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) witnessed a great number of technical innovations, such as steam-powered machines, which resulted in new working practices, which in turn brought many social changes. More women and children worked than ever before, for the first time more people lived in towns and cities than in the countryside, people married younger and had more children, and people's diet improved. The workforce become much less skilled than previously, and many workplaces became unhealthy and dangerous. Cities suffered from pollution, poor sanitation, and crime. The urban middle class expanded, but there was still a wide and unbridgeable gap between the poor, the majority of whom were now unskilled labourers, and the rich, who were no longer measured by the land they owned but by their capital and possessions.

Urbanisation

The population of Britain rose dramatically in the 18th century, so much so that a nationwide census was conducted for the first time in 1801. The census was repeated every decade thereafter and showed interesting results. Between 1750 and 1851, Britain's population rose from 6 million to 21 million. London's population grew from 959,000 in 1801 to 3,254,000 in 1871. The population of Manchester in 1801 was 75,000 but 351,000 in 1871. Other cities witnessed similar growth. The 1851 census revealed that, for the first time, more people were living in towns and cities than in the countryside.

More young people meeting each other in a more confined urban setting meant marriages happened earlier, and the birth rate went up compared to societies in rural areas (which did rise, too, but to a lesser degree). For example, "In urban Lancashire in 1800, 40 per cent of 17-30-year-olds were married, compared to 19 per cent in rural Lancashire. In rural Britain, the average age of marriage was 27, in most industrial areas 24, and in mining areas about 20" (Shelley, 98).

Urbanisation did not mean there was no community spirit in towns and cities. Very often people living in the same street pulled together in a time of crisis. Communities around mines and textile mills were particularly close-knit with everyone being involved in the same profession and with a community spirit and pride fostered by such activities as a colliery or mill band. Workers also got together to form clubs to save up for an annual outing, usually to the seaside.

Life became cramped in the cities that had grown up around factories and coalfields. Many families were obliged to share the same cheaply-built home. "In Liverpool in the 1840s, 40,000 people were living in cellars, with an average of six people per cellar" (Armstrong, 188). Pollution became a serious problem in many places. Poor sanitation – few streets had running water or drains, and non-flushing toilets were often shared between households – led to the spread of diseases. In 1837, 1839, and 1847, there were typhus epidemics. In 1831 and 1849, there were cholera epidemics. Life expectancy rose because of better diet and new vaccinations, but infant mortality could be high in some periods, sometimes over 50% for the under-fives. Not until the 1848 Public Health Act did governments even begin to assume responsibility for improving sanitation, and even then local health boards were slow to form in reality. Another effect of urbanisation was the rise in petty crime. Criminals were now more confident of escaping detection in the ever-increasing anonymity of life in the cities.

Cities became concentrations of the poor, surviving off the charity of those more fortunate. Children roamed the streets begging. Children without homes or a job, if they were boys, were often trained to become a Shoe Black, that is someone who shined shoes in the street. These paupers were given this opportunity by charitable organisations so that they would not have to go to the infamous workhouse. The workhouse was brought into existence in 1834 with the Poor Law Amendment Act. The workhouse was deliberately intended to be such an awful place that it did little more than keep its male, female, and child inhabitants alive, in the belief that any more charity than that would simply encourage the poor not to bother looking for paid work. The workhouse involved what its name suggests – work, but it was tedious work indeed, typically unpleasant and repetitive tasks like crushing bones to make glue or cleaning the workhouse itself. Despite all the problems, urbanisation continued so that by 1880 only 20% of Britain's population lived in rural areas.

Continue reading...

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

America isn’t suffering from a housing shortage. Housing production has lagged behind household growth since 2010, but this doesn’t account for the massive overhang of housing produced in the previous decade. Fueled by the housing bubble of 2000-07, 160 homes were added to the stock for every 100 households formed during the aughts, our analysis of Census Bureau data shows. This level of production created a huge surplus of housing, which has yet to be fully absorbed. Put differently, from 2000-21, the nation grew by 18.5 million households. To maintain an adequate inventory of vacant housing, which historically would be 9.3% of the total, the housing stock needed to expand by 20.2 million units. Instead, it grew by 23.7 million housing units, producing a surplus of 3.5 million units.

[...]

It’s conceivable that a huge increase in supply would eventually lead to lower prices. But that would require a major intervention in the market, and the case for it is weak. U.S. housing policy should focus less on adding to the already ample stock of housing and more on raising the incomes of low-income households and giving them access to good-quality housing in safe neighborhoods. We know how to do this. Raising minimum wages to the living-wage level will help the working poor afford housing. Zoning reform can encourage the production of multifamily housing, accessory apartments, and other less-expensive housing formats. Subsidized construction should be targeted for supportive housing and for affordable rental housing in places with actual housing shortages. The most effective housing assistance for low-income households is not found in building more units but in helping low-income households afford the units that already exist through housing vouchers for renter households and down-payment assistance for home buyers. The U.S. cannot build itself out of its housing crisis.

291 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Simon Sebag Montefiore

There is a myth that the last antisemitic pogrom in the British Isles was in medieval York. It was far more recent than that: The long-forgotten Limerick pogrom happened in 1904. It began with a sermon given by a priest and gathered momentum because it was backed by Arthur Griffith, the founder of the original Sinn Féin and friend of Michael Collins.

The story of the Limerick pogrom (or “boycott,” as it is also known) has a special resonance for me because my grandfather and his family, the Jaffes, lived in Limerick then—though they never mentioned it. Indeed, Irish Jewry, including its most famous son, Chaim Herzog, late president of Israel, had protested that Ireland was the most tolerant land in Europe. Now it appears that they protested too much. The strangest thing of all is that the Jews of today’s Ireland are still frightened of telling this story. When I made a television film about the pogrom, most Irish Jews were too scared of “making trouble, attracting attention” to take part in it.

I had always been proud of my Irish roots. My late grandfather, Henry Jaffe, who lost his Irish accent but kept his debonair Irish charm, used to say that he had seen mermaids at Ballybunion, and Aunt Rose used to reminisce in an Irish brogue about the Limerick Races. While talking to a distinguished Irish political writer, I mentioned that I was descended from Limerick Jews. He told me the story that became the basis of my film about the origins of Sinn Féin.

Virtually the whole Jewish community in Limerick, numbering about 170, were from the village of Akmenė in the Tsar’s Baltic territories, which are now Lithuania—part of the Pale of Settlement, the only area where Jews were allowed to live. When in the 1880s Nicholas II stepped up his anti-Jewish legislation, my great-great-grandfather Benjamin Jaffe and most of Akmenė decided to leave before the Cossacks returned. Benjamin bought a ticket for New York, but when he arrived at the picturesque imperial British port of Queenstown in southern Ireland (now called Cobh, whence the Titanic departed on its final voyage), he was told that he had arrived in the New World. “But that doesn’t look like New York,” the Jews protested as they disembarked. “New York’s the next parish,” they were told. When they discovered this was not the case, they settled in Limerick.

They lived together in considerable poverty on Colooney Street, which soon became known as Little Jerusalem. In the 1901 census, four years before the pogrom, my maternal family were registered as peddlers. The patriarch, Benjamin, a magnificent man with a long white beard, was a peddler, though really he was the chazan (singer) and mohel (circumciser) of the little community. He lived at 64 Colooney Street and his son Max, aged 26, lived at Number 31 with his own family, which included my grandfather Henry, aged 3, and my great-aunt Rose, aged 1.

The family has always been proud that Max was a dentist, but I soon discovered that he was not technically qualified; the census called him, alarmingly, “dental mechanic.” It comments dryly that the family could read and write. They must have been the most erudite peddlers who ever existed, for they were as scholarly as they were poor. My grandfather’s bar mitzvah speech is written in both English and in fluent ancient Hebrew, and filled with biblical references.

However hard it was to do business in Limerick, it seemed a safer sanctuary than Russia. But three years after the census, when my grandfather was 6, hatred of this tiny Jewish community reached fever pitch among the very poor Irish to whom they sold their wares. They often sold on credit, and this caused savage resentment. Sometimes when a Jew went to the surrounding countryside to collect a debt, peasant women would pull out their breasts, shout “Rape!,” and then the men would beat up the Jew. An ostentatious Jewish wedding apparently caused jealousy. The pogrom was the result of the increasingly vicious agitation of the spiritual director of Limerick’s Redemptorist Order, Father John Creagh, whose church overshadowed Little Jerusalem. The climax came when Creagh, “a speaker of fervid eloquence,” gave his sermon entitled “How the Israelites trade,” on Monday, January 11, 1904. It reads like a grotesque parody of antisemitism:

The Jews rejected Jesus, they crucified Him and called down the curse of His precious blood on their own heads. . . they did not hesitate to shed Christian blood. Nowadays they dare not kidnap and slay Christian children, but they will not hesitate to expose them to a longer and more cruel martyrdom by taking the clothes off their backs and the bit out of their mouths.

Then Creagh came to the Jews of Limerick:

Twenty years ago and less, Jews were known only by name and evil repute in Limerick. They were sucking the blood of other nations, but those nations turned them out. And they come to our land to fasten themselves like leeches. Their rags have been exchanged for silk. They have wormed themselves into every business. . . the furniture trade, the milk trade, the drapery trade—and they have even traded under Irish names. . . . The victims of the Jews are mostly women. . . .The Jew has a sweet tongue when he wishes. . . . If you want an example, look to France. What is at present going on in that land?

The reference to the Dreyfus scandal is significant.

The injustice of it was little consolation to the Jews of Colooney Street when the thousand or so worshippers of Creagh’s church poured out, as they were to do daily for a month. A huge drunken mob gathered, wielding burning torches. They worked their way down Colooney Street smashing windows and front doors, and forcing their way into the houses which they then looted. For more than a month the Jews of Limerick waited, terrified in their own homes, almost starving, for Creagh had urged the people not to pay their debts. No one would do business with them. If they walked in the streets, they were beaten. The only miracle was that no one lost his life, but for the Jews who had just escaped the Cossacks, it was terrifying.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

what would actually happen if one were to go into jervis' cell and hug him? would he like... snap your neck? im confused as to why we are being dissuaded from hugging the cuddle boy

WELL, Jerv wouldn't just snap someones neck for no reason! that's a waste of resources and people he could use or make connections with, if he did manage to make one with staff or something.

Killing is messy and causes a lot of conflict with other parties if it happens to be he somehow snuffed out a semi important person. For the most part he only does that when as stated he has no choice/it's a bigger hassle to let someone live....ooooor you pressed a big huge red button that said "I'm going to hurt someone he is fixated on/loves."

like say for example some poor sods trying to attack the trio of rogues and manage to hurt either Ed or Jon, even worse, both? that's when he'd be like a semi truck sprinting in your direction at full force to straight up take you off the census,regardless of his own status physical or otherwise.

Tipping the emotional teapot over will get an anger that could rival the red queen.

he's just a gamble, less so than the other two but still...

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

US President Donald Trump has said he will cut all future funding to South Africa over allegations that it was confiscating land and "treating certain classes of people very badly".

Last month, President Cyril Ramaphosa signed into law a bill that allows land seizures without compensation in certain circumstances.

Land ownership has long been a contentious issue in South Africa with most private farmland owned by white people, 30 years after the end of the racist system of apartheid.

There have been continuous calls for the government to address land reform and deal with the past injustices of racial segregation.

South Africa's president responded to Trump with a post on X: "South Africa is a constitutional democracy that is deeply rooted in the rule of law, justice and equality. The South African government has not confiscated any land."

He added that the only funding South Africa received from the US was through the health initiative Pepfar, which represented "17% of South Africa's HIV/Aids programme".

The US allocated about $440m (£358m) in assistance to South Africa in 2023, according to US government data.

Elon Musk, who was born and grew up in South Africa and is now a Trump adviser, has also joined in the debate, saying the new law discriminated against white people.

"Why do you have openly racist ownership laws?" Mr Musk said to Ramaphosa in a post on X.

South Africans' anger over land set to explode

On Sunday, Trump wrote on his social media platform Truth Social: "I will be cutting off all future funding to South Africa until a full investigation of this situation has been completed!"

He later said, in a briefing with journalists, that South Africa's "leadership is doing some terrible things, horrible things".

"So that's under investigation right now. We'll make a determination, and until such time as we find out what South Africa is doing — they're taking away land and confiscating land, and actually they're doing things that are perhaps far worse than that."

South Africa's new law allows for expropriation without compensation only in circumstances where it is "just and equitable and in the public interest" to do so.

This includes if the property is not being used and there is no intention to either develop or make money from it, or when it poses a risk to people.

Land ownership has long been a contentious issue in South Africa for more than a century. In 1913, the British colonial authorities passed legislation that restricted the property rights of the country's black majority.

The Natives Land Act left the vast majority of the land under the control of the white minority and set the foundation for the forced removal of black people to poor homelands and townships in the intervening decades until the end of apartheid three decades ago.

Anger over these forced removals intensified the fight against white-minority rule.

In 1994, leader of the African National Congress (ANC) Nelson Mandela became the country's first democratically elected president after all South Africans were given the right to vote.

But until the recently passed law, the government was only able to buy land from its current owners under the principle of "willing seller, willing buyer", which some feel has delayed the process of land reform.

In 2017, a government report said that of the farmland that was in the hands of private individuals, 72% was white-owned. According to the 2022 census white people make up 7.3% of the population.

However, some critics have expressed fears that the new land law may have disastrous consequences like in Zimbabwe, where seizures wrecked the economy and scared away investors.

South African Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe responded to Trump's comments by telling a mining conference that the country should withhold its minerals if "they [US] don't give us money".

South Africa exports a variety of minerals to the US, including platinum, iron and manganese.

AfriForum, a group focused on protecting the rights and interests of South Africa's white Afrikaner population, wants the government to change the new law to "ensure the protection of property rights".

However, it said it did not agree with Trump's threat to cut funding, suggesting that any punitive measures should be directed at "senior ANC leaders" and not South Africans.

The ANC, led by Ramaphosa, currently governs South Africa as part of a coalition government with nine smaller parties.

Trump also hit out at South Africa during his first term as US president, asking the-then US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to study the country's "farm seizures and expropriations and the large-scale killing of farmers".

At that time, South Africa accused Trump of seeking to sow division, with a spokesperson saying he was "misinformed".

14 notes

·

View notes