#celtic era

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i had to do it guys..

#hansu speaks#yautja#predator franchise#predator#avp#alien vs predator#celtic#chopper#feral predator#predalien#scar#alexa woods#scarlex#wolf predator#hunter borgia#conrete jungle#royce i-forgot-his-surname#scarface#crucified predator#jungle hunter#im entering my yautja fucker era

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

i desperately crave full power merlin. he was messing with time when he didn't even know one (1) spell, imagine what he could do at his peak bc i genuinely believe we never saw that. a man said to be the embodiment of magic?? said not to have magic but to be magic?? god just imagine it, wielding power like an extension of himself, taking down armies with a wave of his hand, not uttering a single word, traveling through the wind, carried by the elemental magic and reappearing halfway around the world in a single moment, traveling the same through time, reappearing in greece centuries before the romans invade, reappearing in the aztec empire before colonizers landed on their shores, reappearing in new york as cars fly past him and buildings reach up to the heavens.

#bbc merlin#merlin emrys#bamf merlin#powerful merlin#god what i would give to see borderline god/deity merlin#merlin learning magic from all civilizations around the world in every era#being the embodiment of worldly magic#not just celtic#learning from various tribes and kingdoms and nations across time and space#GOD sorry i really want to see it#i dont just want it i NEED it#fanfictions#fanfic#fic ideas#headcanon#head canon#hc#PLEASE SOMEONE WRITE IT#IM TRYING BUT I DONT THINK ILL FINISH IT#AND IF BY SOME MIRACLE I DO FINISH IT#I DONT THINK ITLL EVER ENCOMPASS WHAT IM ENVISIONING

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celtic Design of Interlaced Dogs // The Tortured Poets Department (The Black Dog Variant) – Taylor Swift

#i know this one isn't really in the style of the album covers#but i saw this design and COULD NOT RESIST#ZOOMORPHIC INTERLACING MY ABSOLUTE BELOVED#so anyway i guess now y'all get this version too lmao#anyway i swear 'the black dog' had better be about or at least reference black shuck#taylor swift eras (art history version)#the black dog#black dog#dog#dogs#dogs in art#celtic art#zoomorphic interlace my beloved#the tortured poets department#tortured poets department#ts ttpd#ttpd#taylor swift#ttpd taylor swift#taylor swift ttpd#ts edit#tsedit#tswiftedit#tswift edits#art#art history

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 1: Brittonic Body Paint

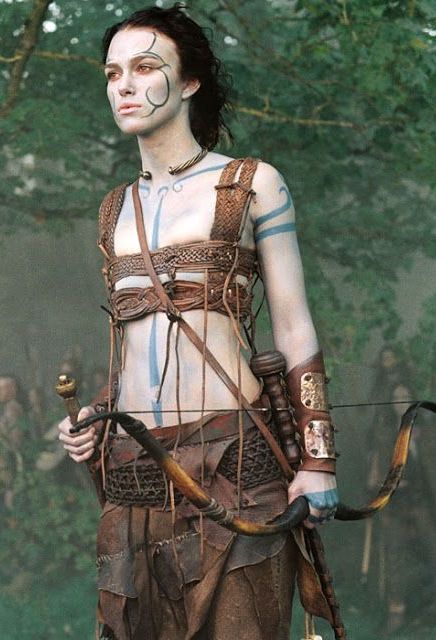

Clockwise from top left: participants in the Picts Vs Romans 5k, a 16th c. painting of painted and tattooed ancient Britons, Boudica: Queen of War (2023), Brave (2012).

The idea that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted themselves blue or tattooed themselves with woad is common in modern culture. But where did this idea come from, and is there any evidence for it? In this post, I will examine the evidence for the use of body paint among the ancient peoples of the British Isles, including both written sources and archaeology.

For this post, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group that lived in the British Isles from the late Iron Age through the early Roman Era. (Later Roman and Medieval sources will be discussed in part 2.) The relevant text sources for Brittonic body paint date from approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Written Sources:

The earliest source for our notion of blue Celts is Julius Cesar's Gallic War book 5, written circa 50 BCE. In it he says, "Omnes vero se Britanni vitro inficiunt, quod caeruleum efficit colorem, atque hoc horridiores sunt in pugna aspectu," which translates as something like, "All the Britons stain themselves with woad, which produces a bluish colouring, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Hollywood sometimes interprets this passage as meaning that the Celts used war paint, but Cesar says that all Britons colored themselves, not just the warriors. The blue coloring just had the effect (on the Romans at least) of making the Briton warriors look scary. The verb inficiunt (infinitive inficio) is sometimes translated as 'paint', but it actually means dye or stain. The Latin verb for paint is pingo (MacQuarrie 1997).

The interpretation of vitro as woad is supported by Vitruvius' statements in De Architectura (7.14.2) that vitrum is called isatis by the Greeks and can be used as a substitute for indigo. Isatis is the Greek word for woad; this is where we get its modern scientific name Isatis tinctoria. Woad and indigo both contain the same blue dye pigment, hence woad can be used as a substitute for indigo (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016). The word vitro can also mean 'glass' in Latin, but as staining yourself with glass doesn't make much sense, it's more commonly interpreted here as woad (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997). I will revisit this interpretation during my discussion of the archaeological evidence.

Almost a century later in De situ orbis, Pomponius Mela says that the Britons "whether for beauty or for some other reason — they have their bodies dyed blue," (translation by Frank E. Romer) using virtually identical language to Cesar, "vitro corpora infecti" (Lib. III Cap. VI p. 63). Pomponius Mela may have copied his information from Cesar (Hoecherl 2016).

Then in 79 CE, Pliny the Elder writes in Natural History book 22 ch 2, "There is a plant in Gaul, similar to the plantago in appearance, and known there by the name of "glastum:" with it both matrons and girls among the people of Britain are in the habit of staining the body all over, when taking part in the performance of certain sacred rites; rivalling hereby the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians, they go in a state of nature." In spite of the fact that glastum means woad in the Gaulish and Celtic languages, Pliny seems to think glastum is not woad. In Natural History book 20 ch 25, he describes different plant which is almost certainly woad, a “wild lettuce” called "isatis" which is "used by dyers of wool." (Woad is a well-known source of fabric dye (Speranza et al 2020)).

Of course, "rivaling the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians" doesn't necessarily mean blue. Pliny seems to think Ethiopians literally have coal-black skin (Latin ater). Additionally, Pliny is taking about a ritual done by women, where Cesar was talking about a practice done by everyone. Are they talking about 2 different cultural practices, or is one of them reporting misinformation? Or are both wrong? Unfortunately, there is no way to know.

The Roman poets Ovid, Propertius, and Marcus Valerius Martialis all make references to blue-colored Britons (Carr 2005), but these are literary allusions, not ethnographic reports. As such, they don't really provide additional evidence that the Britons were actually dyeing or painting themselves blue (Hoecherl 2016). These poetic references merely demonstrate that the Romans believed that the Britons were.

In the sources that come after Pliny the Elder, starting in the 3rd century, there is a shift in the terms used. Instead of inficio which means to dye or stain (Hoecherl 2016), probably a temporary application of color to the surface of the skin, later sources use words like cicatrices (scars) and stigma/stigmata (brand, scar, or tattoo) (Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997, Carr 2005) which suggest a permanent placement of pigment under the skin, i.e. a tattoo. This evidence for tattooing will be discussed in a second post.

Discussion:

Although the Romans clearly believed that the Britons were coloring themselves with blue pigment, that doesn't necessarily mean that Julius Cesar, Pomponius Mela, or Pliny the Elder are reliable sources.

In the sentence before he claims that all Britons color themselves blue, Julius Cesar says that most inland Britons "do not sow corn [aka grain], but live on milk and flesh and clothe themselves in skins." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). This is demonstrably false. Grains like wheat and barley and storage pits for grain have been found at multiple late Iron Age sites in inland Britain (van der Veen and Jones 2006, Lightfood and Stevens 2012, Lodwick et al 2021). This false characterization of Insular Celts as uncivilized savages would continue to show up more than a millennium later in English descriptions of the Irish.

Pomponius Mela, in addition to believing in blue-dyed Britons, also believed that there was an island off the coast of Scythia inhabited by a race called the Panotii "who for clothing have big ears broad enough to go around their whole body (they are otherwise naked)" (Chorographia Bk II 3.56 translation from Romer 1998). Pliny the Elder also believed in Panotii.

15th-century depiction of a Panotii from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Was Celtic body paint as real as these guys?

The Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio make no mention of body paint in their coverage of Iron Age British history (Hoecherl 2016). Their silence on the subject suggests that, in spite of Cesar's claim that all Britons colored themselves blue, the custom of body staining or painting was not actually widespread.

Considering all of these issues, is any of this information trustworthy? Based on my experience studying 16th c. Irish dress, even bigoted sources based on second-hand information often have a grain of truth somewhere in them. Unfortunately, exactly which bit is true is hard to identify without other sources of evidence, and this far in the past we don't have much.

Archaeological Evidence:

There are no known artistic depictions of face paint or body art from Great Britain during this time period. There are some Iron Age continental European coins that show what may be face painting or tattoos, but no such images have been found on British coins (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

In order for the Britons to have dyed themselves blue, they needed to have had blue pigment. Woad is not native to Great Britain (Speranza et al 2020), but Woad seeds have been found in a pit at the late Iron Age site of Dragonby in England, so the Britons had access to woad as a potential pigment source in Julius Cesar's time (Van der Veen et al 1993). Egyptian blue is another possible source of blue pigment. A bead made of Egyptian blue was found at a late Bronze Age site in Runnymede, England. Pieces of Egyptian blue could have been powdered to produce a pigment for body paint. (Hoecherl 2016). Egyptian blue was also used by the Romans to make blue-colored glass (Fleming 1999). Perhaps this is what Cesar meant by 'vitro'.

Potential sources of blue: Isatis tinctoria (woad) leaves and a lump of Egyptian blue from New Kingdom Egypt

Modern experiments have found that reasonably effective body paint can be made by mixing indigo powder either with water, forming a runny paint which dries on the skin, or with beef drippings, forming a grease paint which needs soap to be removed (Carr 2005, reenactor description). The second recipe is very similar to one used by modern east African argo-pastoralists which consists of ground red ocher mixed with cow fat (unpublished interview*).

Finding blue pigment on the skin of a bog body might confirm Julius Cesar's claim, but unfortunately, the results here are far from conclusive. To my knowledge, Lindow II is the only British bog body that has been tested for indigotin, the dye pigment in woad and indigo. No indigotin was found (Taylor 1986).

The late Iron Age-early Roman era bog bodies Lindown II and Lindown III show some evidence of mineral-based body paint (Joy 2009, Giles 2020). Both of them have elevated levels of calcium, aluminum, silicon, iron, and copper in their skin. Lindow III also has elevated levels of titanium. The calcium levels may simply be the result the of the bog leeching calcium from their bones. Some researchers have suggested that the other elements may be from mineral-based paints applied to the skin. The aluminum and silicon may be from clay minerals. The iron and titanium could be from red ocher. The copper could be from malachite, azurite, or Egyptian blue (CuCaSiO4), pigments that would give a green or blue color (Pyatt et al 1995, Pyatt et al 1991). These elements may have other sources however, and are not present in large enough amounts to provide definitive proof of body paint (Cowell and Craddock 1995, Giles 2020). Testing done on the early Roman Era (80-220 CE) Worsley Man has found no evidence of mineral-based paint (Giles 2020).

One final type of artifact that provides some support for Julius Cesar's claim is a group of small cosmetic grinders from late Iron Age-Roman Era Britain. These mortar and pestle sets are found almost exclusively in Great Britain and are of a style which appears to be an indigenous British development. They are distinctly different from the stone palettes used by the Romans for grinding cosmetics which suggests that these British grinders were used for a different purpose than making Roman-style makeup (Carr 2005). Archaeologist Gillian Carr has suggested that these British grinders might have been used by the Britons for grinding, mixing, and applying a woad-based body paint (Carr 2005).

Left and center: Cosmetic grinder set from Kent. Right: Cosmetic mortar from Staffordshire. images from Portable Antiquities Scheme under CC attribution license

The mortars have a variety of styles of decoration, but the pestles (top left and top center) typically feature a pointed end which could be used for applying paint to the skin (Carr 2005). The grinders are quite small, (most are less than 11 cm (4.5 in) long), making them better suited to preparing paint for drawing small designs rather than for dyeing large areas of skin (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

Conclusions:

Admittedly, this post is a bit off-topic, since the Irish are not mentioned, but dress history is also about what people did not wear. Hollywood has a tendency to overgeneralize and expropriate, so I want to be clear: There is no known evidence that the ancient Irish used body paint.

So, who did? For the reasons I have already discussed, I don't consider any of the Roman writers particularly trustworthy, but I think the following conclusions are plausible:

A least a few people in Great Britain dyed/stained or painted their bodies between circa 50 BCE and perhaps 100 CE, after which mentions of it end. Written sources from c. 200 CE on talk about tattoos rather than painting or staining. The custom of body dyeing/painting may have started as something practiced by everyone and later changed to something practiced by just women.

None of the writers mention any designs being painted, but Julius Cesar's description could encompass designs or solid area of color. Pliny, on the other hand, states that women were coloring their entire bodies a solid color. The dye was probably blue, although Pliny implies it was black. (I know of no plants in northern Europe that resemble plantago and produce a black dye. I think Pliny was reporting misinformation.)

Archaeological evidence and experimental recreations support the possibility that woad was the source of the pigment, but they cannot confirm it. Data from bog bodies indicate that a mineral pigment like azurite or Egyptian blue is more likely, but these samples are too small to be conclusive.

The small cosmetic grinders are suitable for making designs which might match Cesar and Mela's descriptions, but not Pliny's description of all-over body dyeing.

*Interview with a Daasanach woman I participated in while doing field school in Kenya in 2015.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowell, M., and Craddock, P. (1995). Addendum: Copper in the Skin of Lindow Man. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 74-75). British Museum Press.

Fleming, S. J. (1999). Roman Glass; reflections on cultural change. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Roman_Glass/ONUFZfcEkBgC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Joy, J. (2009). Lindow Man. British Museum Press, London. https://archive.org/details/lindowman0000joyj/mode/2up

Lightfoot, E., and Stevens, R. E. (2012). Stable Isotope Investigations of Charred Barley (Hordeum vulgare) and Wheat (Triticum spelta) Grains from Danebury Hillfort: Implications for Palaeodietary Reconstructions. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(3), 656–662. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.10.026

Lodwick, L., Campbell, G., Crosby, V., Müldner, G. (2021). Isotopic Evidence for Changes in Cereal Production Strategies in Iron Age and Roman Britain. Environmental Archaeology, 26(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1718852

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

Pomponius Mela. (1998). De situ orbis libri III (F. Romer, Trans.). University of Michigan Press. (Original work published ca. 43 CE) https://topostext.org/work/145

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Buckland, P.C., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Storey, D.M. (1995). Mobilization of Elements from the Bog Bodies Lindow II and III and Some Observations on Body Painting. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 62-73). British Museum Press.

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Buckland, P.C. (1991) Non isatis sed vitrum or, the colour of Lindow Man. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 10(1), 61–73. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227808912_Non_Isatis_sed_Vitrum_or_the_colour_of_Lindow_Man

Speranza, J., Miceli, N., Taviano, M.F., Ragusa, S., Kwiecień, I., Szopa, A., Ekiert, H. (2020). Isatis Tinctoria L. (Woad): A Review of Its Botany, Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Biotechnical Studies. Plants, 9(3): 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9030298

Taylor, G. W. (1986). Tests for Dyes. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 41). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Van der Veen, M., and Jones, G. (2006). A Re-analysis of Agricultural Production and Consumption: Implications for Understanding the British Iron Age. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 15 (3), 217–228. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0040-3 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27247136

Van der Veen, M., Hall, A., and May, J. (1993). Woad and the Britons painted blue. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 12(3), 367-371. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249394983

#cw anti-black racism#romano-british#period typical bigotry#iron age#bog bodies#no photographs of bog bodies though#roman era#ancient celts#celtic#woad#insular celts#anecdotes and observations#body paint#brittonic#archaeology

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

#celtic witch#pagan witch#baby witch#beginner witch#pagan stuff#witch#witches#witch community#witchcraft#folk witchcraft#herbal magic#witchs heart#green witch#solitary witch#traditional witchcraft#eclectic pagan#wicca#witch au#witch altar#witch academia#witch blog#witch boy#witch craft#witch era#witch friends#witch girl#witch goth#hedge witch#witch in the woods#witch journal

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herman Melville on Napoleon’s love for Ossian

Context: Ossian is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as Fingal (1761) and Temora (1763), and later combined under the title The Poems of Ossian.

“I am rejoiced to see Hazlitt speak for Ossian. There is nothing more contemptable in that contemptable man (tho' good poet, in his department) Wordsworth, than his contempt for Ossian. And nothing that more raises my idea of Napoleon than his great admiration for him.—The loneliness of the spirit of Ossian harmonized with the loneliness of the greatness of Napoleon.”

Melville wrote this around 1862 in the margins of his copy of Hazlitt’s Lectures on the English Comic Writers and Lectures on the English Poets

Source: Hershel Parker, Herman Melville: A Biography - Volume 2, p. 436

#Herman Melville#Melville#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Hershel Parker#Herman Melville biography#Herman Melville: A Biography#Hazlitt#Lectures on the English Comic Writers#Ossian#romanticism#napoleonic era#napoleonic#american literature#American lit#american renaissance#Wordsworth#the poems of Ossian#celtic mythology#fingal#temora#british literature#Scottish#scottish literature#Scotland#writers and Napoleon

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

still thinking about the jays win last night and it made me realize how much i’ve missed nba tumblr 🫶🏾

#thinking about cazluvsu’s post about being the Celtics mutual and realizing I need to be active to become the sixers mutual 🙏🏾#nba#basketball#nba finals#the jays#tb to my active era circa 2022 :(#guys trust im funny on the tl sometimes#last night convinced me to stop abandoning my blog every few months

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

i should be studying for the klausuren but instead i have been drinking at the stammtisch and watching the letzten spieltag der gruppenphase this is truly what erasmus is all about god i love deutschland (i am going to fail all my exams)

#anyway no i dont want city in the playoffs BUT#my brother supports celtic and he’ll genuinely never speak to me again if bayern draw them and win#like i will be disowned#bad either way ig???????#fc bayern#the germany era

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023/24 SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP MATCH DAY 31

Rangers 3-3 Celtic 7th April 2024 Ibrox Stadium

Tavernier (55' pen), Sima (86'), Matondo (90+3') Maeda (1'), O'Riley (34' pen), Idah (87')

#rangers fc#rangers#glasgow rangers#rangers football club#rangersfc-1872#rangersfc#ClementEra#2023/24#2023/24 season#old firm#old firm derby#scottish premiership#spfl#rangers v celtic#glasgow rangers v glasgow celtic#james tavernier#abdallah sima#rabbi matondo#john souttar#connor goldson#philippe clement#clement era#cyriel dessers#ibrox#rivalry#rivals#derby#glasgow

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

He's feeling himself and I wish I could feel him too ✌🏻😩

#IT'S GAMES BACK TO BACK TO BACK TO BACK TO BACK TO BACK TO BACK TO BACK TO BACK TO BACK#HOW DID I EVER DO THIS BEFORE??#CELTIC IS ALWAYS PLAYING THEN I'M WATCHING THE AMERICANS TO KEEP AN EYE ON A SEXY MF THEN I'M WATCHING RACES BECAUSE IT'S MY COUGAR ERA#WHAT IS THIS#I'M OLD I'M TIRED I NEED A BREAK DON'T Y'ALL NEED A BREAK OR SUMTIN'??#HOW DOES HE HAVE THIS MUCH ENERGY AT 38?? I'M NOT EVEN THERE YET AND I'M **TIRED**#LET ME SUCK THE SOUL OUT OF YOU KASPER I KNOW YOU HAVE ACCESS TO THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH#this mf looks so damn good..#his whole 🍑 was on my screen during the game.. what a blessed night#Kasper Schmeichel#king thicccness#big daddy 😩😩😩

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

are you okay or do you cry watching videos of the 2003 patriots game where the seats weren’t shoveled out and everyone had to sit on snowbanks and threw snowballs at the dolphins players? because i totally just didn’t

#I’m one of those Patriots fans#I could write a whole essay on how much the Brady era meant to me#we just had so much fun#that era of the Sox / Bruins / Celtics too

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like you know how all the clowns are clowning for Taylor Swift to announce reputation Taylor’s version in Dublin (June 30th)? What if she announces debut? Like I get the evidence for reputation because of the old catholic legend that St Patrick (the patron saint of ireland) banished all the snakes from ireland in like 500 AD (sorry primary school teachers, I forgot when st Patrick was alive). Which doesn’t make a lot of sense for reputation really… mainly because he banished the snakes. But with cáil is feminine reputation so that could work with the ttpd logo. (Irish/Gaelige is one of the languages with fem and masc words like Spanish/Español). But back to my debut theory- Ireland’s nickname is Emerald Isle because of its lucious greenery. This makes sense with debut because debut is all nature vibes. And Éire (Irelands name is Gaelige) is derived from Ériu who is the goddess of the island of ireland according to Celtic legend. Celtic mythology is mostly associated with nature (not that it is all about that).

I don’t mind whether Taylor Swift announces rep or debut but I just really want an announcement for ireland !! <3

#ireland#éire#ériu#celtic#celtic mythology#reputation#debut#taylor swift debut#taylor swift#st patrick#if I have to hear the snake & st patrick story ONE MORE TIME I’m going to kms#because since I was 5 years old every single st Patrick’s day we learn about that same story#same with st brigids day#she’s another patron saint of ireland#she’s really cool tho#I LOVE her#she got her name from the Celtic goddes brigid actually!#I should stop with the fun facts#the eras tour#the eras tour Dublin#dublin

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tbh I miss celtic comet

#it was an era.....#morgan rambles#my ramblings#Celtic thunder#colm keegan#emmet cahill#celtic comet#ct#morgan lives up to her old url

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should this Celt be blue?

An irish-dress-history game.

I've been researching the actual historical evidence behind the idea that ancient Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves blue, and I thought it would be fun to make a game out of it. Below are various depictions of this idea along with the culture and date they are supposed to be depicting. The game is to guess whether each use of body paint or tattoos is supported by actual historical evidence. Answers are in the image descriptions.

(Note: This game is not intended to mock or criticize the artists and costume designers of any of these works. Good information on this topic is hard to find, and movie creators and artists frequently have goals other than historical accuracy. I am mocking Mel Gibson though, because f*** that guy.)

1 A 'Woad' (ie Pict) from 5th c. Britain. 2. Tattooed Irish warrior in 1170

3. A Medieval Scottish lord 4. Iceni Queen Boudica c. 60 CE

5. Ancient? Ireland 6. Britons during the time of Julius Cesar

7. Picts in 149 CE 8. Scots in 1297

Bibliography:

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

#iron age#roman era#early medieval#ancient celts#celtic#pict#tattoos#body painting#medieval#insular celts#gaelic irish#Hoecherl#brittonic celts#britons#gaels#scots

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I’ve just watched this video discussing the issue of contemporary fantasy novels using/appropriating Welsh culture as well as other Celtic cultures.

And I would really recommend watching it to anyone thinking of writing fantasy set in or inspired by Wales, who is hoping to do so sensitively and respectfully.

I thought this might also be particularly useful for those of us in the Marauders fandom who love Welsh Remus and want to incorporate Welsh folklore/mythology/modern day culture into the world building to compliment his backstory.

There is a way to do these things respectfully and a way that there is not.

As someone with Welsh grandparents and family who live there, I can assure you that Wales, while beautiful and magical in its own way, is also a thoroughly modern nation with the same issues we all face in the modern world. Wales is not some fantasy nation stuck 1000 years in the past.

Welsh culture is also not in any way limited to its mythology. There is such a rich culture including, but not limited to, things like sport (e.g rugby), the arts (much of the bbc is based there) and so so much more.

There is also a very rich and important modern history in Wales that many people entirely bypass. For example, the mining industry has a huge importance and impact in Wales’ history, among many other things.

And very very importantly, if you choose to utilise the Welsh language in any way, make sure that you ask a Welsh speaker politely to read it over for you.

Because Welsh is NOT a fantasy language. It is a living, modern language, and is some people’s first language. We should treat it with the respect it deserves.

#and if you want to learn more about Welsh culture… please do!#research!#read!#but unfortunately this lil English gal is vastly unqualified to expand any further on these things myself#fantasy#appropriation of Welsh culture#‘Celtic inspired’ fantasy#marauders era#Welsh Remus#welsh remus lupin#Youtube

0 notes