#but was not a provincial king himself

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tropes-To-Lovers

Characters: All NRC boys x fem!reader (seperately)

Fandom: Twisted Wonderland

Genre: fluff

What were you to the NRC boys, before you were lovers?

Includes: Childhood friends to lovers, best friends to lovers, strangers to lovers, enemies to lovers, exes to lovers.

Childhood Friends to Lovers

Trey Clover the boy next door

Everyone and their mother knows Trey Clover, the golden boy in your little provincial town. Sweet, intelligent, and he can bake? He’s a heartthrob in every definition of the word. But Trey’s only ever had eyes for you, his parents’ best friends’ daughter and the girl next door.

Joined at the hip from the moment you met, you’ve done it all together- but Trey’s been away at NRC for three years. You were sure he would move to the city after getting a taste of the wider world. So you’re caught off-guard when he returns to take over his family’s bakery, eight inches taller than you remember.

His eyes crinkle at the corners when he sees you, and you can feel the firmness of muscles under his shirt when you launch yourself at him, embracing him tightly. He has to bend down to hug you now, you realize. And his face is sharper now, jaw angular instead of the soft cheeks you were used to. When did that happen?

And when did he get so handsome?

Leona Kingscholar betrothed to his brother

Leona has only ever had one friend- you, the heir from the neighboring kingdom. It shouldn’t be a problem to love you the way he does, but the stars in the sky had other plans, it seemed. Because from the moment you were born, you were meant to marry Falena.

Leona has long-since learned that no matter what he does, he’ll never be enough to win the public’s love. It didn’t matter that he knew you never had feelings for Falena, or that Falena was seeing someone else in secret. His brother will be king, not him. He’ll watch you walk down the aisle towards him, and then he’ll go back to his room and take a nap, and tell himself that he won’t be upset. That’s just the way life will be.

One day, while napping behind a curtain in the royal library, he catches wind of something so very interesting. Your parents arrived in the kingdom that morning, bearing news: Falena’s engagement has been peaceably broken, by your own choice, nonetheless. It’s a huge, life-changing decision and so a formal dinner is being held, to re-discuss the terms of the treaty. Leona wants to snap you up right away to be his, but he has to bide his time. For now, he’ll meet your eye across the banquet table, scowl softening a little. He should have known that he has always been king in your heart.

Silver childhood soulmates

Right person, right place, right time. Rarely did the universe ever align so beautifully. From your first meeting at the tender age of five to the time you were accepted into NRC, Silver has always been by your side.

He’s the first thing you see when you wake up in the mornings and the final good night you say before going to sleep. When small birds land on your desk and deposit gifts of acorns and flowers to you, you know exactly who they were from and who was thinking of you at the moment. And when you look at your handsome knight, you can’t help but imagine him by your side, every step of the way for the rest of your life.

Silver is more than just your best friend and first love. He is your person, through and through.

Best Friends to Lovers

Epel Felmier first friend, first love

You met Epel on the first day of school, getting beat up by a blonde upperclassman in the hallway. Much to the surprise of both boys, you jumped in to help him- pulling him off the ground and scolding the taller boy, who merely scoffed and wandered off. Though Epel’s ego was a bit bruised, he was grateful to you for helping him.

Epel became your constant companion after that. You could listen to him talk for hours while laying on the floor of your dorm room, a bag of apple chips in hand. His roguish accent and mischievous jokes charm you a little more each day, making him more than just the rough-hewn boy you met at the entrance ceremony not long ago.

His grandparents know all about you from the letters he sends home. Even in ink, they can sense his lovestruck heart. They had felt the same way when they started courting all those years ago. The Felmier family are fools in love, it seems. You would call him your best friend if someone asked, but Epel wants to be so much more.

Ace Trappola best friends to lovers

It’s pathetic how fast Ace changed his tune. The first time he met you, he was jeering you for being a magicless human. Now, he’s in love with you? When did that happen? And why did it have to be with you of all people?

Ace isn’t fooling himself. He knows why it’s you. It’s simply because no one could ever capture his heart the same way you do, with your smiles and your laughs and the way you look at him in both disapproval and exasperated fondness when he makes a crude joke.

Don’t act surprised when he holds your hand out of the blue or when he searches your face with those eyes, wondering what it would feel like to kiss you silly right then and there. He wants you, not anyone else, and it’s driving him crazy.

Kalim Al-Asim what are we?

Everyone thinks you and Kalim are dating already. You joke about it all the time. Oh, yeah, we’re partners in crime! Soulmates! Two sides of the same coin- but the line between teasing and reality has begun to blur. Once, you even made a jibe that you’d marry him one day, and Kalim got you an actual ring! It was so extravagant- a ruby inlaid with smaller gilded gems along the edges. He told you it was a family treasure, kept in the storerooms of Scarabia and just waiting to adorn the hand of the right person.

You tried to refuse, but he insisted. Money wasn’t something the Al-Asim heir ever had to worry about. So you go along with it, the golden band rubbing between your fingers and his when you walk down the halls, hands interlaced.

How does Kalim really feel about you? You’re not sure, so one day you ask- Kalim, what are we?

He looks at you curiously. “Aren’t we engaged?”

Strangers to Lovers

Deuce Spade the hallway crush

Every day between alchemy and history of magic, Deuce finds himself scanning faces in the hallway for someone who makes his face flush and his palms turn sweaty. And every day when you catch his eye and send him a wave, he finds himself tangled up a little more in his heartstrings, tripping over his feet as he tries to return your greeting.

He’s not sure when he first noticed you. Maybe it was when he fumbled and nearly dropped a potion on the carpet, and you caught it. His heart did flutter a bit then, but maybe that was because he nearly messed up the project he had been working on all night. He wants to talk to you again so badly- more than just a ‘hello‘ or a ‘thanks.’ He wants to brighten up your day just by walking by, like you do for him. Maybe if he becomes an honors student, then you’ll finally notice him too.

Jack Howl the mysterious savior

Being hounded by a group of rogue students wasn’t in your plans for the day. Trying to slip between the mob, avoiding their prying hands and sharp words, a sudden growl makes them all look up. A tall boy with wolflike ears towers over them.

Leave them alone. His voice is sharp, like a dog's canines. Golden eyes meet yours, steely and cold, but they soften for a moment when you manage to say thank you.

Your savior rubs the back of his neck. ‘S nothing, he says gruffly, but the lingering traces of blush on his face tell a different story. Only when he leaves do you realize that you had never gotten his name. Perhaps fate will lead you to meet once again, in the near future.

Azul Ashengrotto love at first sight

One minute he’s discussing the best way to mix a potion with his lab partner. The next, he’s sitting straight in his chair, eyes blown wide when you walk into the room. You’ve ensnared Azul Ashengrotto’s attention and heart without a single word. And when you finally say hi to him, ignorant of his shady dealings and strange company, he’s caught- hook, line, and sinker.

Azul begins to do things for you. Not in the way he does for others, with a flourish of his pen and a snap of his fingers. No, you’re special. He could never ask anything of you.

It’s so obvious, the way he favors you and gives you the best of everything he has. But he can’t bring himself to care- not when this new feeling brings him such happiness.

Idia Shroud closer than he thought

Idia Shroud has never met you irl. No way. All you are to him is a profile picture on a leaderboard, telling him to dodge the next attack or that he’ll never beat you in the latest game the two of you are playing. You make his gloomy days a little brighter. And when they’re brighter, he finally takes a chance to step outside for a bit and go to class.

In class is where he met you. His charming desk partner, whose presence he enjoyed far more than he thought he would. He likes your jokes. He likes that you play the same games as him and nerd out about the same topics. But when he returns to the world of online anonymity, he can’t help but feel disloyal- so much so that he doesn’t notice the lilt of the voice in his speakers is the same one that rings in his ears when he falls asleep in class.

Malleus Draconia love from afar

No one knows who you are, a mere human who attends NRC. You could be dangerous as far as his retainers know. Malleus isn’t supposed to speak with you- but oh, does he want to.

He’s tried to ignore the pull towards you, but he just can’t. Why is this mere child of man lingering in his thoughts, ensnaring his every waking moment?

One night when Sebek is busy berating Silver for falling asleep on the job, he sneaks away and finds you beneath the moonlight, staring up at the stars. He’s caught like a fly in a web from the first hello.

Enemies to Lovers

Riddle Rosehearts academic rivals

He’s so annoying. With a loud voice, short stature, and short temper, you could consider Riddle Rosehearts to always be underfoot. But even you have to admire his academic prowess, his name topping the scores at every turn. And just under him, is you. How very frustrating.

You’re so focused on one-upping one another that you don’t even catch yourself when thoughts of him wander into your mind throughout the day. Of course you think of him, you’re trying to beat him. But slowly the competition turns into wondering. What does he do in his free time? What’s his favorite food, his favorite color?

Little do you know, he thinks of you too.

Ruggie Bucchi the goodhearted thief

You heard from your neighbors about the slum thief who steals things from their shops. It’s only a matter of time before he comes to you next, they warn, so be ready.

And ready you are. When a skinny boy with rounded ears atop his head tries to slip something into his pocket, you call him out. And when he dashes away, you scramble after him- tackling him in a paved alley near some dumpsters. Cans go crashing over to reveal several homeless youngsters, shivering in the cold and barely more than bones. The boy tosses the food to them before you can intervene- but why would you, when you’ve just seen what you saw?

When he comes into the bakery next time, you make sure he pays. But you also slip an extra loaf or two into his order, with a wink and a nod. Your conversations become a bit longer, a bit friendlier. He’s quite charming and you have to berate yourself for falling for a thief.

He’s stolen your heart, hasn’t he?

Floyd Leech the hallway bully

Floyd Leech. Just his name makes you groan and roll your eyes. It’s not just you he teases you in the hallway by holding your things over his head, but you seem to be his favorite. How are you supposed to get your notebook back when it’s dangling almost 8 feet above the ground, courtesy of his freakishly long arms?

The graceful solution you come up with is to kick him. Right in his eel, to summarize. His twin brother is by his side in an instant while you walk off.

Jade expects Floyd to be livid. But even when he’s doubled up on the ground in pain, he’s got a grin plastered across his face.

His shrimpy is such a badass.

Jamil Viper flirting rivals

For someone who’s usually level-headed and cool, you sure bring out Jamil’s temper. He can find a million ways to insult and discredit you, but still you’ll bounce back with some snarky, suggestive comment that just makes his blood boil.

He swears he can feel your eyes on him from across the hallways. It makes him want to pull his hood up over his face. But when you approach him, he’s as calm as ever. Why are you leaning closer, prefect, and running your hands over his tie? He’s not going to fall for your ruse, so don’t even try.

Still, his eyes can’t help but wander down to your lips, wondering if they would taste like he imagined.

Rook Hunt one-sided annoyance

It seems like you’ve gained yourself a one-man paparazzi recently. If Rook is meant to be a hunter, you have to wonder if he’s any good at his job. He never seems to conceal his presence, following you down the hallways brazenly while spouting off fake compliments about your demeanor and beauty.

Well, you thought they were fake. It’s hard to believe anyone is genuine in a school full of villains, but you might have caught the attention of the one person who actually is. His company isn’t so bad sometimes, especially when you can talk his ear off about anything and everything.

Sebek Zigvolt forced proximity

This was meant to be a partner project, not a threeway. But being paired with the great Malleus Draconia means putting up with his annoying, self-proclaimed bodyguard for the next week as well.

You pity Sebek’s alchemy partner, because he’s ignoring his own work in favor of hovering over you and his liege. His loud, unsolicited advice and passive-aggressive comments don’t make him any more bearable. By the time Thursday rolls around, you’re about ready to drop-kick him into the cauldron.

Thankfully, you and Malleus get your work done early. When you’re packing up your things to leave, you find Sebek quiet for once, deep in concentration as he rushes to finish his own work.

I don’t need the help of a human, he proclaims in that loud, obnoxious bark of his. But he doesn’t complain when you settle down next to him, stirring the potion while he measures out ingredients.

Exes to Lovers

Cater Diamond the one that got away

Cater knows you probably hate his guts. Hell, he hates his own guts for fucking up so badly. You were the best thing that ever happened to him and he drove you away with his constant neediness and self-deprecation. It took him years to realize that he was so focused on himself that he didn’t realize that you needed support too.

He’s been lonely for a while, working on himself and his problems in the shadows. It’s been a while since he last saw you- he knows you might not want to see him again anyways, but he’s changed now- both for himself and for you.

Cater wants you back, if you’ll have him.

Jade Leech second chance romance

Jade was nothing more than a talking stage that never got off the ground. He was fun to be around and a good hiking partner, but you stopped seeing him after first year ended and you no longer shared a class together.

You didn’t think of him much throughout your second and third year at NRC . But when you arrive at your new work study to meet your partner for the program, a tall, familiar figure greets you at the door.

“Jade?”

Vil Schoenheit right person, wrong time

Vil has no one but himself to blame for the downfall of your relationship. He broke things off with you after his manager advised him to- she said that a young, taken idol isn’t marketable. You need to think about your image.

The stage lights blinded him and he dropped you without a second thought. Any trace of you in his life was erased; smoothed over to perfection like a beauty filter.

But oh, how Vil regrets it when he scrolls on his phone late at night, your Magicam account pulled up to a photo of you laughing. What he wouldn’t give to have you smile like that at him again.

The icon for a DM request sits beside your profile picture. Vil regards it for a second, finger hovering over the button, then clicks.

Lilia Vanrouge facing the future

Lilia has always known that humans live short lives. In his time, he’s seen countless people born and died. It’s just a fact of human life; a phenomena he watches from the outside in- disconnected. It doesn’t dawn on him that yours too will run out until Malleus points it out- and then Lilia becomes scared.

He’ll cut you off, hiding in the shadows and avoiding your eyes until a great danger almost befalls you. It is then that Lilia realizes he’d rather have loved and lost you than never have known you at all.

Please, stay with him. You have the rest of your life, however short or long, to live by his side. Lilia would gladly warp time and face the consequences just for one more minute with you.

#twisted wonderland imagines#twisted wonderland x reader#twisted wonderland#riddle rosehearts x reader#trey clover x reader#cater diamond x reader#deuce spade x reader#ace trappola x reader#leona kingscholar x reader#ruggie bucchi x reader#jack howl x reader#azul ashengrotto x reader#jade leech x reader#floyd leech x reader#kalim al asim x reader#jamil viper x reader#vil schoenheit x reader#rook hunt x reader#epel felmier x reader#idia shroud x reader#malleus draconia x reader#lilia vanrouge x reader#twst silver#silver x reader#sebek zigvolt x reader

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

John's Passion narrative has a never-ending fascination for me, because it's where you get Jesus at his most divine--knowing everything that was going to happen, making the guards fall to their faces when he speaks the name of God--while the people around him are at their most human.

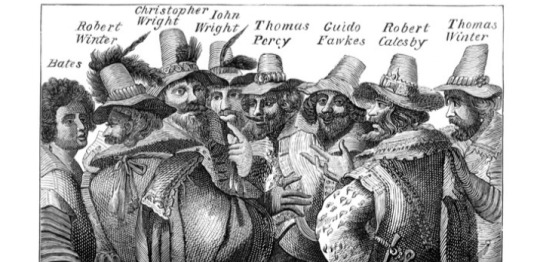

There's an entire political drama going on. Pilate the Roman pagan getting dragged into this provincial Jewish religious dispute. These Jewish leaders and Jesus providing different visions of truth to a politician who doesn't care what the truth is. There's extremely sharp political back-and-forth between the Roman and the Jewish authorities--the Pharisees trying to force Pilate's hand by saying that everyone who makes himself a king opposes Caesar, then Pilate backing them into proclaiming Caesar as their king and twisting the knife of pettiness by labeling Jesus as the Jewish king in four different languages while He hangs on the cross.

Petty, personal, political human drama taking up all their attention.

And meanwhile, God is dying.

#catholic things#good friday#every year i think the story's going to be old hat#and every year i get sucked into the drama of the west-wing-level political backbiting#mixed with all the divine drama happening in the background#but reading it last night i was shocked by how much of the story goes by while jesus fades into the background#only to come back into focus so dramatically

403 notes

·

View notes

Text

《苦昼短》 唐 · 李贺

飞光,飞光,劝尔一杯酒。

吾不识青天高黄地厚,唯见月寒日暖,来煎人寿。

食熊则肥,食蛙则瘦。

神君何在,太一安有?

天东有若木,下置衔烛龙。

吾将斩龙足,嚼龙肉,使之朝不得回,夜不得伏。

自然老者不死,少者不哭。

何为服黄金,吞白玉?

谁似任公子,云中骑碧驴。

刘彻茂陵多滞骨,嬴政梓棺费鲍鱼。

(punctuation added by me)

"Short Bitter Days" Tang Dynasty, Li He

Oh fleeting time, may you drink this cup of wine. I do not know how high the blue sky, nor how thick the yellow earth, I only see the cold of the moon and warmth of the sun (the days and seasons passing), wearing away our lifetimes.

Those who eat bear grow fat, those who eat frogs become thin.

Where are the gods, is there truly a heavenly emperor?

In the east of the sky there is a celestial arbor*, beneath it the zhulong**.

(*) borrowing this translation from hsr because hsr chinese also sometimes uses 若木 to refer to the 建木 as both terms refer to a massive mythical tree

(**) mythical dragon that controls the day night cycle

I shall cleave the dragon's feet, and eat the dragon's flesh, so it cannot fly during the day nor rest at night.

Thus the old will not die, and the young will not weep.

What use is there in eating yellow gold or swallowing white jade?

Who can be like Master Ren, riding through the clouds on a white/green* donkey? (*) there exists some debate on if this is supposed to be white or green in this line

Liu Che's* grave at Maoling is full of withered bones, Ying Zheng's** catalpa coffin wasted many abalone.

(*) Liu Che was the 7th emperor of the Han Dynasty, living from 156 to 87 BCE, and his gravesite is called Maoling. He was interested in seeking immortality.

(**) Ying Zheng was the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty, and really the first emperor in Chinese history, responsible for uniting all the warring states and establishing the imperial system that would last for over two millennia after his life from 259 to 210 BCE. He died while touring the nation, suspected foul play by one of his sons trying to usurp the throne, and to keep his death hidden while they were returning to the capital his coffin (emperor's coffins were traditionally made of catalpa wood) was covered in abalone to hide the stench of his slowly rotting corpse.

Another poem I had previously read but didn't understand fully. Li He wrote this poem during the Yuanhe era (806-820 CE) of the Tang Dynasty's Xianzong Emperor Li Chun's rule. At the time Li Chun was extremely obsessed with obtaining immortality himself, to the point where he even famously appointed an alchemist as a provincial governor. Naturally whatever the emperor is interested in, the entire court is interested in in order to gain his favor. Knowing this historical background it's very clear what Li He was criticizing.

I also think this poem is a good concrete example of the Chinese attitude towards divinity. I believe @999-roses at one point showed a xhs post in which a Chinese user was asking why Westerners didn't have any stories about fighting their gods, whereas Chinese mythology is full of examples of characters fighting against the highest gods, most famously the three "rebels of heaven" Sun Wukong (the Monkey King), Nezha, and Yang Jian (Er Lang Shen). Many coastal regions had temples to the dragon kings who were believed to control the rain, however during long droughts people in some regions have a tradition of taking the dragon king's statue out of the temple and exposing it to the harsh sunlight, and even whipping it to give the offending gods a taste of the pain they inflict on the people by denying them rain. In this poem Li He is proclaiming he will slay and eat the dragon that controls the day night cycle (and by extension the normal passage of time) and bring immortality to all.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Splendid You rise in the lightland of the sky, O living Aten, creator of life ! You have dawned in the eastern lightland. You fill every land with your beauty." -Great Hymn to the Aten, 1-4.

Aten/Aton Talon Abraxas

Ancient Egyptian Aten: Sun God And Creator Deity Symbols: sun disk, heat and light of the sun Cult Center: Akhetaten (Tel El-Amarna) Aten was a being who represented the god or spirit of the sun, and the actual solar disk. He was depicted as a disk with rays reaching to the earth. At the end of the rays were human hands which often extended the ankh to the pharaoh. Aten's origins are unclear and he may have been a provincial Sun-god worshipped in one of the small villages near Heliopolis. Aten was called the creator of man and the nurturing spirit of the world. In the Book of the Dead, Aten is called on by the deceased, "Hail, Aten, thou lord of beams of light, when thou shinest, all faces live." It is impossible to discuss Aten without mentioned his biggest promoter, the pharaoh Amenhotep IV, or Akhenaten. Early in his reign, Akhenaten worshipped both Amon (the chief god in Thebes at the time) and Aten. The first as part of his public duties, the latter in private. When he restored and enlarged the temple of Aten first built by his father Amenhotep III, relations between him and priests of Amon became strained. The priests were a major power in Egypt and if another god became supreme they would lose their own prestige. Eventually, relations became so strained that Akhenaten decided to built his own capital by the Nile, which he called, "Akhetaten", the Horizon of the Aten. At Akhetaten, Akhenaten formed a new state religion, focusing on the worship of the Aten. It stated that Aten was the supreme god and their were no others, save for Akhenaten himself. It has been said that Akhenaten formed the first monotheistic religion around Aten. However, this is not the case. Akhenaten himself was considered to be a creator god and like Aten was born again every day. Aten was only accessible to the people through Akhenaten because Akhenaten was both man and part of the cosmos. Akhenaten systematically began a campaign to erase all traces of the old gods, especially Amon. He erased the name of Amon from the temples and public works. He even went so far as to erase his own father's cartouche because the word "Amon" was featured in it. Even the word "gods" was unacceptable because it implied there were other deities besides Aten. It is clear that the Egyptian people never accepted their king's religion and view of the world. Even at his own capital, Akhetaten, amulets featuring Bes and Tauret have been found. Following Akhenaten's death, Atenism died rapidly. Mostly because the people never really believed in it and also because Akhenaten's successors did all they could to erase Akhenaten and Aten from the public eye. Eventually, Akhetaten became abandoned and the name "Akhenaten" conjured the dim memory of a "heretic king."

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Alexander Hamilton: A Timeline

As Alexander Hamilton’s time serving as Captain of the New York Provincial Company of Artillery is about to become my main focus within The American Icarus: Volume I, I wanted to put a timeline together to share what I believe to be a super fascinating period in Hamilton's life that’s often overlooked. Both for anyone who may be interested and for my own benefit. If available to me, I've chosen to hyperlink primary materials directly for ease. My main repositories of info for this timeline were Michael E. Newton's Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton and The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series on Founders Online, and the Library of Congress, Hathitrust, and the Internet Archive. This was a lot of fun to put together and I can not wait to include fictionalizations of all this chaos in TAI (literally, 20-something chapters are dedicated to this) hehehe....

Because context is king, here is a rundown of the important events that led to Alexander Hamilton receiving his appointment as captain:

Preceding Appointment - 1775:

February 23rd: The Farmer Refuted, &c. is first published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. The publication was preceded by two announcements, and is a follow up to a string of pamphlet debate between Hamilton and Samuel Seabury that had started in the fall of 1774. The Farmer Refuted would have wide-reaching effects.

April 19th: Battles of Lexington and Concord — The first shots of the American War for Independence are fired in Lexington, Massachusetts, and soon followed by fighting in Concord, Massachusetts.

April 23rd: News of Lexington and Concord first reaches New York. [x] According to his friend Nicholas Fish in a later letter, "immediately after the battle of Lexington," Hamilton "attached himself to one of the uniform Companies of Militia then forming for the defense of the Country by the patriotic young men of this city." It is most likely that Hamilton enlisted in late April or May of 1775, and a later record of June shows that Hamilton had joined the Corsicans (later named the Hearts of Oak), alongside Nicholas Fish and Robert Troup (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 127; for Fish's letter, Newton cites a letter from Fish to Timothy Pickering, dated December 26, 1823 within the Timothy Pickering Papers of the Massachusetts Historical Society).

June 14th: Within weeks of his enlistment, Hamilton's name appears within a list of men from the regiments throughout New York that were recommended to be promoted as officers if a Provencal Company should be raised (pp. 194-5, Historical Magazine, Vol 7).

June 15th: Congress, seated in Philadelphia, establishes the Continental Army. George Washington is unanimously nominated and accepts the post of Commander-in-Chief. [x]

Also on June 15th: Alexander Hamilton’s Remarks On the Quebec Bill: Part One is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 22nd: The Quebec Bill: Part Two is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 25th: On their way to Boston, General Washington and his generals make a short stop in New York City. The Provincial Congress orders Colonel John Lasher to "send one company of the militia to Powle's Hook to meet the Generals" and that Lasher "have another company at this side (of) the ferry for the same purpose; that he have the residue of his battalion ready to receive" Washington and his men. There is no confirmation that Alexander Hamilton was present at this welcoming parade, however it is likely, due to the fact that the Corsicans were apart of John Lasher's battalion. [x]

Also on June 25th: According to a diary entry by one Ewald Shewkirk, a dinner reception was held in Washington's honor. It is unknown if Hamilton was present at this dinner, however there is no evidence to suggest he could not have been (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 129; Newton cites Johnston, Henry P. The Campaigns of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn, Vol. 2, pg. 103).

August 23-24th: According to his friend Hercules Mulligan decades later in his “Narrative” (being a biographical sketch, reprinted in the William & Mary Quarterly alongside a “Narrative” and letters from Robert Troup), Hamilton and himself took part in a raid upon the city's Battery with a group composed of the Corsicans and some others. They managed to haul off a good number of the cannons down in the city Battery. However, the Asia, a ship in the harbor, soon sent a barge and later came in range of the raiding party itself, firing upon them. According to Mulligan, “Hamilton at the first firing [when the barge appeared with a small gun-crew] was away with the Cannon.” Mulligan had been pulling this cannon, when Hamilton approached and asked Mulligan to take his musket for him, taking the cannon in exchange. Mulligan, out of fear left Hamilton’s musket at the Battery after retreating. Upon Hamilton’s return they crossed paths again and Hamilton asked for his musket. Being told where it had been left in the fray, “he went for it, notwithstanding the firing continued, with as much unconcern as if the vessel had not been there.”

September 14th: The Hearts of Oak first appear in the city records. [x] Within the list of officers, Fredrick Jay (John Jay’s younger brother), is listed as the 1st Lieutenant, and also appears in a record of August 9th as the 2nd Lieutenant of the Corsicans. This, alongside John C. Hamilton’s claims regarding Hamilton’s early service, has left historians to conclude that either the Corsicans reorganized into the Hearts of Oak (this more likely), or members of the Corsicans later joined the Hearts of Oak.

December 4th: In a letter to Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, John Jay writes “Be so kind as to give the enclosed to young Hamilton.” This enclosure was presumably a reply to Hamilton’s letter of November 26th (in which he raised concern for an attack upon James Rivington’s printing shop), however Jay’s reply has not been found.

December 8th: Again in a letter to McDougall, Jay mentions Hamilton: “I hope Mr. Hamilton continues busy, I have not recd. Holts paper these 3 months & therefore cannot Judge of the Progress he makes.” What this progress is, or anything written by Hamilton in John Holt’s N. Y. Journal during this period has not been definitively confirmed, leaving historians to argue over possible pieces written by Hamilton.

December 31st: Hamilton replies to Jay’s letter that McDougall likely gave him around the 14th [x]. Comparing the letters Hamilton sent in November and December I will likely save for a different post, but their differences are interesting; more so with Jay’s reply having not been found.

These mentionings of Hamilton between Jay and McDougall would become important in the next two months when, in January of 1776, the New York Provincial Congress authorized the creation of a provincial company of artillery. In the coming weeks, Hamilton would see a lot of things changing around him.

Hamilton Takes Command - 1776:

February 23rd: During a meeting of the Provincial Congress, Alexander McDougall recommends Hamilton for captain of this new artillery company, James Moore as Captain-Lieutenant (i.e: second-in-command), and Martin Johnston for 1st Lieutenant. [x]

February-March: According to Hercules Mulligan, again in his “Narrative”, "a Commission as a Capt. of Artillery was promised to" Alexander Hamilton "on the Condition that he should raise thirty men. I went with him that very afternoon and we engaged 25 men." While it is accurate that Hamilton was responsible for raising his company, as acknowledged by the New York Provincial Congress [later renamed] on August 9th 1776, Mulligan's account here is messy. Mulligan misdates this promise, and it may not have been realistic that they convinced twenty-five men to join the company in one afternoon. Nevertheless, Mulligan could have reasonably helped Hamilton recruit men between the time he was nominated for captancy and received his commission.

March 5th: Alexander Hamilton opens an account with Alsop Hunt and James Hunt to supply his company with "Buckskin breeches." The account would run through October 11th of 1776, and the final receipt would not be received until 1785, as can be seen in Hamilton's 1782-1791 cash book.

March 10th: Anticipating his appointment, Hamilton purchases fabrics and other materials for the making of uniforms from a Thomas Garider and Lieutenant James Moore. The materials included “blue Strouds [wool broadcloth]”, “long Ells for lining,” “blue Shalloon,” and thread and buttons. [x]

Hamilton later recorded in March of 1784 within his 1782-1791 cash book that he had “paid Mr. Thompson Taylor [sic: tailor] by Mr Chaloner on my [account] for making Cloaths for the said company.” This payment is listed as “34.13.9” The next entry in the cash book notes that Hamilton paid “6. 8.7” for the “ballance of Alsop Hunt and James Hunts account for leather Breeches supplied the company ⅌ Rects [per receipts].” [x]

Following is a depiction of Hamilton’s company uniform!

First up is an illustration of an officer (not Hamilton himself) as seen in An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Uniforms of The American War For Independence, 1775-1783 Smith, Digby; Kiley, Kevin F. pg. 121. By the list of supplies purchased above, this would seem to be the most accurate depiction of the general uniform.

Here is another done in 1923 of Alexander Hamilton in his company's uniform:

March 14th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that "Alexander Hamilton be, and he is hereby, appointed captain of the Provincial company of artillery of this Colony.” Alongside Hamilton, James Gilleland (alternatively spelt Gilliland) is appointed to be his 2nd Lieutenant. “As soon as his company was raised, he proceeded with indefatigable pains, to perfect it in every branch of discipline and duty,” Robert Troup recalled in a later letter to John Mason in 1820 (reprinted alongside Mulligan’s recollections in the William & Mary Quarterly), “and it was not long before it was esteemed the most beautiful model of discipline in the whole army.”

March 24th: Within a pay roll from "first March to first April, 1776," Hamilton records that Lewis Ryan, a matross (who assisted the gunners in loading, firing, and spounging the cannons), was dismissed from the company "For being subject to Fits." Also on this pay roll, it is seen that John Bane is listed as Hamilton's 3rd Lieutenant, and James Henry, Thomas Thompson, and Samuel Smith as sergeants.

March 26th: William I. Gilbert, also a matross, is dismissed from the company, "for misbehavior." [x]

March-April: At some point between March and April of 1776, Alexander Hamilton drops out of King's College to put full focus towards his new duties as an artillery captain. King's College would shut down in April as the war came to New York City, and the building would be occupied by American (and later British) forces. Hamilton would never go back to complete his college degree.

April 2nd: The Provincial Congress having decided that the company who were assigned to guard the colony's records had "been found a very expensive Colony charge" orders that Hamilton "be directed to place and keep a proper guard of his company at the Records, until further order..." (Also see the PAH) According to historian Willard Sterne Randall in an article for the Smithsonian Magazine, the records were to be "shipped by wagon from New York’s City Hall to the abandoned Greenwich Village estate of Loyalist William Bayard." [x]

Not-so-fun fact: it is likely that this is the same Bayard estate that Alexander Hamilton would spend his dying hours inside after his duel with Aaron Burr 28 years later.

April 4th: Hamilton writes a letter to Colonel Alexander McDougall acknowledging the payment of "one hundred and seventy two pounds, three shillings and five pence half penny, for the pay of the Commissioned, Non commissioned officers and privates of [his] company to the first instant, for which [he has] given three other receipts." This letter is also printed at the bottom of Hamilton’s pay roll for March and April of 1776.

April 10th: In a letter of the previous day [April 9th] from General Israel Putnam addressed to the Chairmen of the New York Committee of Safety, which was read aloud during the meeting of the New York Provincial Congress, Putnam informs the Congress that he desires another company to keep guard of the colony records, stating that "Capt. H. G. Livingston's company of fusileers will relieve the company of artillery to-morrow morning [April 10th, this date], ten o'clock." Thusly, Hamilton was relieved of this duty.

April 20th: A table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress titled "A Return of the Company of Artillery commanded by Alexander Hamilton April 20th, 1776." The Library of Congress itself lists this manuscript as an "Artillery Company Report." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table and describe the return as "in the form of a table showing the number of each rank present and fit for duty, sick, on furlough, on command duty, or taken as prisoner." [x]

The table, as seen above, shows that by this time, Hamilton’s company consisted of 69 men. Reading down the table of returns, it is seen that three matrosses are marked as “Sick [and] Present” and one matross is noted to be “Sick [and] absent,” and two bombarders and one gunner are marked as being “On Command [duty].” Most interestingly, in the row marked “Prisoners,” there are three sergeants, one corporal, and one matross listed.

Also on April 20th: Alexander Hamilton appears in General George Washington's General Orders of this date for the first time. Washington wrote that sergeants James Henry and Samuel Smith, Corporal John McKenny, and Richard Taylor (who was a matross) were "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. stark was President for “Mutiny"...." The Court found both Henry and McKenny guilty, and sentenced both men to be lowered in rank, with Henry losing a month's pay, and McKenny being imprisoned for two weeks. As for Smith and Taylor, they were simply sentenced for disobedience, but were to be "reprimanded by the Captain, at the head of the company." Washington approved of the Court's decision, but further ordered that James Henry and John McKenny "be stripped and discharged [from] the Company, and [that] the sentence of the Court martial, upon serjt Smith, and Richd Taylor, to be executed to morrow morning at Guard mounting." As these numbers nearly line up with the return table shown above, it is clear that the table was written in reference to these events. What actions these men took in committing their "Mutiny" are unclear.

May 8th: In Washington's General Orders of this date, another of Hamilton's men, John Reling, is written to have been court martialed "for “Desertion,” [and] is found guilty of breaking from his confinement, and sentenced to be confin’d for six-days, upon bread and water." Washington approved of the Court's decision.

May 10th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington recorded that "Joseph Child of the New-York Train of Artillery" was "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. Huntington was President for “defrauding Christopher Stetson of a dollar, also for drinking Damnation to all Whigs, and Sons of Liberty, and for profane cursing and swearing”...." The Court found Child guilty of these charges, and "do sentence him to be drum’d out of the army." Although Hamilton was not explicitly mentioned, his company was commonly referred to as the "New York Train of Artillery" and Joseph Child is shown to have enlisted in Hamilton's company on March 28th. [x]

May 11th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington orders that "The Regiment and Company of Artillery, to be quarter’d in the Barracks of the upper and lower Batteries, and in the Barracks near the Laboratory" which would of course include Alexander Hamilton's company. and that "As soon as the Guns are placed in the Batteries to which they are appointed, the Colonel of Artillery, will detach the proper number of officers and men, to manage them...." Where exactly Hamilton and his men were staying prior to this is unclear.

May 15th: Hamilton appears by name once more in General George Washington’s General Orders of this date. Hamilton’s artillery company is ordered “to be mustered [for a parade/demonstration] at Ten o’Clock, next Sunday morning, upon the Common, near the Laboratory.”

May 16th: In General Washington's General Orders of this date, it is written that "Uriah Chamberlain of Capt. Hamilton’s Company of Artillery," was recently court martialed, "whereof Colonel Huntington was president for “Desertion”—The Court find the prisoner guilty of the charge, and do sentence him to receive Thirty nine Lashes, on the bare back, for said offence." Washington approved of this sentence, and orders "it to be put in execution, on Saturday morning next, at guard mounting."

May 18th: Presumably, Hamilton carried out the orders given by Washington in his General Orders of May 16th, and on the morning of this date oversaw the lashing of Uriah Chamberlain at "the guard mounting."

May 19th: At 10 a.m., Hamilton and his men gathered at the Common (a large green space within the city which is now City Hall Park) to parade before Washington and some of his generals as had been ordered in Washington's General Orders of May 15th. In his Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene (on page 57), William Johnson in 1822 recounted that, (presumably around or about this event):

It was soon after Greene's arrival on Long Island, and during his command at that post, that he became acquainted with the late General Hamilton, afterwards so conspicuous in the councils of this country. It was his custom when summoned to attend the commander in chief, to walk, when accompanied by one or more of his aids, from the ferry landing to head-quarters. On one of these occasions, when passing by the place then called the park, now enclosed by the railing of the City-Hall, and which was then the parade ground of the militia corps, Hamilton was observed disciplining a juvenile corps of artillerist, who, like himself, aspired to future usefulness. Greene knew not who he was, but his attention was riveted by the vivacity of his motion, the ardour of his countenance, and not less by the proficiency and precision of movement of his little corps. Halt behind the crowd until an interval of rest afforded an opportunity, an aid was dispatched to Hamilton with a compliment from General Greene upon the proficiency of his corps and the military manner of their commander, with a request to favor him with his company to dinner on a specified day. Those who are acquainted with the ardent character and grateful feelings of Hamilton will judge how this message was received. The attention never forgotten, and not many years elapsed before an opportunity occurred and was joyfully embraced by Hamilton of exhibiting his gratitude and esteem for the man whose discerning eye had at so early a period done justice to his talents and pretensions. Greene soon made an opportunity of introducing his young acquaintance to the commander in chief, and from his first introduction Washington "marked him as his own."

Michael E. Newton notes that William Johnson never produced a citation for this tale, and goes on to give a brief historiography of it (Johnson being the first to write about this). While it is possible that General Greene could have sent an aide-de-camp to give his compliments to Hamilton after seeing his parade drill, there is no certain evidence to suggest that Greene introduced Hamilton to George Washington. Newton also notes that "John C. Hamilton failed to endorse any part of the story." (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 150-152).

May 26th: Alexander Hamilton writes a letter to the New York Provincial Congress concerning the pay of his men. Hamilton points out that his men are not being paid as they should be in accordance to rules past, and states that “They do the same duty with the other companies and think themselves entitled to the same pay. They have been already comparing accounts and many marks of discontent have lately appeared on this score.” Hamilton further points out that another company, led by Captain Sebastian Bauman, were being paid accordingly and were able to more easily recruit men.

Also on May 26th: the Provencal Congress approved Hamilton’s request, resolving that Hamilton and his men would receive the same pay as the Continental artillery, and that for every man he recruited, Hamilton would receive 10 shillings. [x]

May 31st: Captain Hamilton receives orders from the Provincial Congress that he, “or any or either of his officers," are "authorized to go on board any ship or vessel in this harbour, and take with them such guard as may be necessary, and that they make strict search for any men who may have deserted from Captain Hamilton’s company.” These orders were given after "one member informed the Congress that some of Captain Hamilton’s company of artillery have deserted, and that he has some reasons to suspect that they are on board of the Continental ship, or vessel, in this harbour, under the command of Capt. Kennedy." Unfortunately, I as of writing this have been unable to find any solid information on this Captain Kennedy to better identify him, or his vessel.

June 8th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that Hamilton "furnish such a guard as may be necessary to guard the Provincial gunpowder" and that if Hamilton "should stand in need of any tents for that purpose" Colonel Curtenius would provide them. It is unknown when Hamilton's company was relieved of this duty, however three weeks later, on June 30th, the Provincial Congress "Ordered, That all the lead, powder, and other military stores" within the "city of New York be forthwith removed from thence to White Plains." [x]

Also on June 8th: the Provincial Congress further orders that "Capt. Hamilton furnish daily six of his best cartridge makers to work and assist" at the "store or elaboratory [sic] under the care of Mr. Norwood, the Commissary."

June 10th: Besides the portion of Hamilton's company that was still guarding the colony's gunpowder, it is seen in a report by Henry Knox (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 920) that another portion of the company was stationed at Fort George near the Battery, in sole command of four 32-pound cannons, and another two 12-pound cannons. Simultaneously, another portion of Hamilton's company was stationed just below at the Grand Battery, where the companies of Captain Pierce, Captain Burbeck, and part of Captain Bauman's manned an assortment of cannons and mortars.

June 17th: The New York Provincial Congress resolves that "Capt. Hamilton's company of artillery be considered so many and a part of the quota of militia to be raised for furnished by the city or county of New-York."

June 29th: A return table, reprinted in Force, Peter's American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 1122 showcases that Alexander Hamilton's company has risen to 99 men. Eight of Hamilton's men--one bombarder, two gunners, one drummer, and four matrosses--are marked as being "Sick [but] present." One sergeant is marked as "Sick [and] absent" and two matrosses are marked as "Prisoners."

July 4th: In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress approves the Declaration of Independence.

July 9th: The Continental Army gathers in the New York City Common to hear the Declaration read aloud from City Hall. In all the excitement, a group of soldiers and the Sons of Liberty (who included Hercules Mulligan) rushed down to the Bowling Green to tear down an equestrian statue of King George III, which they would melt into musket balls. For a history of the statue, see this article from the Journal of the American Revolution.

Also on July 9th: the New York Provincial Congress approve the Declaration of Independence, and hereafter refer to themselves as the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York. [x]

July 12th: Multiple accounts record that the British ships Phoenix and Rose are sailing up the Hudson River, near the Battery, when as Hercules Mulligan stated in a later recollection, "Capt. Hamilton went on the Battery with his Company and his piece of artillery and commenced a Brisk fire upon the Phoenix and Rose then passing up the river. When his Cannon burst and killed two of his men who I distinctly recollect were buried in the Bowling Green." Mulligan's number of deaths may be incorrect however. Isac Bangs records in his journal that, "by the carelessness of our own Artilery Men Six Men were killed with our own Cannon, & several others very badly wounded." Bangs noted further that "It is said that several of the Company out of which they were killed were drunk, & neglected to Spunge, Worm, & stop the Vent, and the Cartridges took fire while they were raming them down." In a letter to his wife, General Henry Knox wrote that "We had a loud cannonade, but could not stop [the Phoenix and Rose], though I believe we damaged them much. They kept over on the Jersey side too far from our batteries. I was so unfortunate as to lose six men by accidents, and a number wounded." Matching up with Bangs and Knox, in his own journal, Lieutenant Solomon Nash records that, "we had six men cilled [sic: killed], three wound By our Cannons which went off Exedently [sic: accidentally]...." A William Douglass of Connecticut wrote to his wife on July 20th that they suffered "the loss of 4 men in loading [the] Cannon." (as seen in Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 142; Newton cites Henry P. Johnston's The Campaigns of 1776 in and around New York and Brooklyn, vol. 2, pg. 67). As these accounts cobberrate each other, it is clear that at least six men were killed. Whether these were all due to Hamilton's cannon exploding is unclear, but is a possibility. Hamilton of course was not punished for this, but that is besides the point.

One of the men injured by the explosion of the cannon was William Douglass, a matross in Hamilton's company (not to be confused with the William Douglass quoted above from Connecticut). According to a later certificate written by Hamilton on September 14th, Douglass "faithfully served as a matross in my company till he lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors date Douglass' injury to June 12th, but it is clear that this occurred on July 12th due to the description Hamilton provides.

July 26th: Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives (who he mistakenly addresses as the "The Honoruable The Provincial Congress") concerning the amount of provisions for his company. He explains that there is a difference in the supply of rations between what the Continental Army and Provisional Army and his company are receiving. He writes that "it seems Mr. Curtenius can not afford to supply us with more than his contract stipulates, which by comparison, you will perceive is considerably less than the forementioned rate. My men, you are sensible, are by their articles, entitled to the same subsistence with the Continental troops; and it would be to them an insupportable discrimination, as well as a breach of the terms of their enlistment, to give them almost a third less provisions than the whole army besides receives." Hamilton requests that the Convention "readily put this matter upon a proper footing." He also notes that previously his men had been receiving their full pay, however under an assumption by Peter Curtenius that he "should have a farther consideration for the extraordinary supply."

July 31st: The Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York read Hamilton's letter of July 26th at their meeting, and order that "as Capt. Hamilton's company was formally made a part of General Scott's brigade, that they be henceforth supplied provisions as part of that Brigade."

A Note On Captain Hamilton’s August Pay Book:

Starting in August of 1776, Hamilton began to keep another pay book. It is evident by Thomas Thompson being marked as the 3rd lieutenant that this was started around August 15th. The cover is below:

For unknown reasons, the editors of The Papers of Alexander Hamilton only included one section of the artillery pay book in their transcriptions, being a dozen or so pages of notes Hamilton wrote presumably after concluding his time as a captain on some books he was reading. The first section of the book (being the first 117 image scans per the Library of Congress) consists of payments made to and by Hamilton’s men, each receiving his own page spread, with the first few pages being a list of all men in the company as of August 1776, organized by surname alphabetically. The last section of the pay book (Image scans 181 to 185) consists of weekly company return tables starting in October of 1776.

As these sections are not transcribed, I will be including the image scans when necessary for full transparency, in case I have read something incorrectly. Now, back to the timeline....

August 3rd: John Davis and James Lilly desert from Hamilton's company. Hamilton puts out an advertisement that would reward anyone who could either "bring them to Captain Hamilton's Quarters" or "give Information that they may be apprehended." It is presumed that Hamilton wrote this notice himself (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 147-148; for the notice, Newton cites The New-York Gazette; and the weekly Mercury, August 5, 12, and September 2nd, 1776 issues).

August 9th: The Convention of the Representatives resolve that "The company of artillery formally raised by Capt. Hamilton" is "considered as a part of the number ordered to be raised by the Continental Congress from the militia of this State, and therefore" Hamilton's company "hereby is incorporated into Genl. Scott's brigade." Here, Hamilton would be reunited with his old friend, Nicholas Fish, who had recently been appointed as John Scott's brigade major. [x]

August 12th: Captain Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives concerning a vacancy in his company. Hamilton explains that this is due to “the promotion of Lieutenant Johnson to a captaincy in one of the row-gallies, (which command, however, he has since resigned, for a very particular reason.).” He requests that his first sergeant, Thomas Thompson, be promoted as he “has discharged his duty in his present station with uncommon fidelity, assiduity and expertness. He is a very good disciplinarian, possesses the advantage of having seen a good deal of service in Germany; has a tolerable share of common sense, and is well calculated not to disgrace the rank of an officer and gentleman.…” Hamilton also requested that lieutenants James Gilleland and John Bean be moved up in rank to fill the missing spots.

August 14th: The Convention of the Representatives, upon receiving Hamilton’s letter of August 12th, order that Colonel Peter R. Livingston, "call upon [meet with] Capt. Hamilton, and inquire into this matter and report back to the House."

August 15th: Colonel Peter R. Livingston reports back to the Convention of the Representatives that, "the facts stated by Capt. Hamilton are correct..." The Convention thus resolves that "Thomas Thompson be promoted to the rank of a lieutenant in the said company; and that this Convention will exert themselves in promoting, from time to time, such privates and non-commissioned officers in the service of this State, as shall distinguish themselves...." The Convention further orders that these resolutions be published in the newspapers.

August ???: According to Hercules Mulligan in his "Narrative" account, Alexander Hamilton, along with John Mason, "Mr. Rhinelander" and Robert Troup, were at the Mulligan home for dinner. Here, Mulligan writes that, after Rhineland and Troup had "retired from the table" Hamilton and Mason were "lamenting the situation of the army on Long Island and suggesting the best plans for its removal," whereupon Mason and Hamilton decided it would be best to write "an anonymous letter to Genl. Washington pointing out their ideas of the best means to draw off the Army." Mulligan writes that he personally "saw Mr. H [Hamilton] writing the letter & heard it read after it was finished. It was delivered to me to be handed to one of the family of the General and I gave it to Col. Webb [Samuel Blachley Webb] then an aid de Champ [sic: aide-de-camp]...." Mulligan expresses that he had "no doubt he delivered it because my impression at that time was that the mode of drawing off the army which was adopted was nearly the same as that pointed out in the letter." There is no other source to contradict or challenge Hercules Mulligan's first-hand account of this event, however the letter discussed has not been found.

August 24th: Alexander Hamilton helped to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Herman Zedwitz from committing treason. On August 25th, a court martial was held (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 5th Series, vol. I, pp. 1159-1161) wherein Zedwitz was charged with "holding a treacherous correspondence with, and giving intelligence to, the enemies of the United States." In a written disposition for the trial, Augustus Stein tells the Court that on the previous day [this date, August 24th] Zedwitz had given him a letter with which Stein was directed "to go to Long-Island with [the] letter [addressed] to Governour Tryon...." Stein, however, wrote that he immediately went "to Captain Bowman's house, and broke the letter open and read it. Soon after. Captain Bowman came in, and I told him I had something to communicate to the General. We sent to Captain Hamilton, and he went to the General's, to whom the letter was delivered." By other instances in this court martial record, it is clear that Stein had meant Captain Sebastian Bauman (and to this, Zedwitz's name is also spelled many different times throughout this record), which would indicate that the "Captain Hamilton" mentioned was Alexander Hamilton, Bauman's fellow artillery captain. Bauman was the only captain serving by that name in the army at this time (see Heitman, Francis B. Historical Register of the Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, pg. 92). It could be possible that Alexander Hamilton personally delivered this letter into Washington's hands and explained the situation, or that he passed it on to one of Washington's staff members.

August 27th: Battle of Long Island — Although Alexander Hamilton was not involved in this battle, for no primary accounts explicitly place him in the middle of this conflict, it is significant to note considering the previous entry on this timeline.

May-August: According to Robert Troup, again in his 1821 letter to John Mason, he had paid Hamilton a visit during the summer of 1776, but did not provide a specific date. Troup noted that, “at night, and in the morning, he [Hamilton] went to prayer in his usual mode. Soon after this visit we were parted by our respective duties in the Army, and we did not meet again before 1779.” This date however, may be inaccurate, for also according to Troup in another letter reprinted later in the William & Mary Quarterly, they had met again while Hamilton was in Albany to negotiate the movement of troops with General Horatio Gates in 1777.

September 7th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington writes that John Davis, a member of Alexander Hamilton's company who had deserted in early August, was recently "tried by a Court Martial whereof Col. Malcom was President, was convicted of “Desertion” and sentenced to receive Thirty-nine lashes." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered that it be carried out "on the regimental parade, at the usual hour in the morning."

September 8th: In his General Orders of this date, Washington writes that John Little, a member of "Col. Knox’s Regt of Artillery, [and] Capt. Hamilton’s Company," was tried at a recent court martial, and convicted of “Abusing Adjt Henly, and striking him”—ordered to receive Thirty-nine lashes...." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered it, along with the other court martial sentences noted in these orders, to be "put in execution at the usual time & place."

September 14th: Hamilton writes a certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who “lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships” on July 12th. Hamilton recommends that a recent resolve of the Continental Congress be heeded regarding “all persons disabled in the service of the United States.”

September 15th: On this date, the Continental Army evacuated New York City for Harlem Heights as the British sought control of the city. According to the Memoirs of Aaron Burr, vol. 1, General Sullivan’s brigade had been left in the city due to miscommunication, and were “conducted by General Knox to a small fort” which was Fort Bunker Hill. Burr, then a Major and aide-de-camp to General Israel Putman, was directed with the assistance of a few dragoons “to pick up the stragglers,” inside the fort. Being that Knox was in command of the Army’s artillery, Hamilton’s company would be among those still at the fort. Major Burr and General Knox then had a brief debate (Knox wishing to continue the fight whereas Burr wished to help the brigade retreat to safety). Aaron Burr at last remarked that Fort Bunker Hill “was not bomb-proof; that it was destitute of water; and that he could take it with a single howitzer; and then, addressing himself to the men, said, that if they remained there, one half of them would be killed or wounded, and the other half hung, like dogs, before night; but, if they would place themselves under his command, he would conduct them in safety to Harlem.” (See pages 100-101). Corroborating this account are multiple certificates and letters from eyewitnesses of this event reprinted in the Memiors on pages 101-106. In a letter, Nathaniel Judson recounted that, “I was near Colonel Burr when he had the dispute with General Knox, who said it was madness to think of retreating, as we should meet the whole British army. Colonel Burr did not address himself to the men, but to the officers, who had most of them gathered around to hear what passed, as we considered ourselves as lost.” Judson also remarked that during the retreat to Harlem Heights, the brigade had “several brushes with small parties of the enemy. Colonel Burr was foremost and most active where there was danger, and his con-duct, without considering his extreme youth, was afterwards a constant subject of praise, and admiration, and gratitude.”

Alexander Hamilton himself recounted in later testimony for Major General Benedict Arnold’s court martial of 1779 that he “was among the last of our army that left the city; the enemy was then on our right flank, between us and the main body of our army.” Hamilton also recalled that upon passing the home of a Mr. Seagrove, the man left the group he was entertaining and “came up to me with strong appearances of anxiety in his looks, informed me that the enemy had landed at Harlaam, and were pushing across the island, advised us to keep as much to the left as possible, to avoid being intercepted….” Hercules Mulligan also recounted in his “Narrative” printed in the William & Mary Quarterly that Hamilton had “brought up the rear of our army,” and unfortunately lost “his baggage and one of his Cannon which broke down.”

September 28th: In his General Orders of this date, Washington wrote that William Higgins of Hamilton’s artillery was “convinced by a General Court Martial” where “Col. Weedon is President” for the crime of “‘plundering and stealing’.” Higgins was “ordered to be whipped Thirty-nine lashes.” Although this noted court martial is written in the present tense, the editors of The George Washington Papers reveal in the second note of the document that Higgins was “convicted the previous day [September 27th] for having “‘[broken] open a Chest & stealing a Number of Articles out of it in a Room of the Provost Guard’” as was written in the court marrial’s proceedings, which can be found in the Library of Congress’ George Washington Papers.

September ???: As can be seen in Hamilton's August 1776-May 1777 pay book, while stationed in Harlem Heights (often abbreviated as "HH" in the pay book), nearly all of Hamilton's men received some sort of item, whether this be shoes, cash payments, or other articles.

October 4th: A return table for this date appears in Alexander Hamilton’s pay book, in the back. These return tables are not included in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton for unknown reasons.

The table, as seen above, provides us a snapshot of Hamilton’s company at this time, as no other information survives about the company during October. His company totaled to 49 men. Going down the table, two matrosses were “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder, four gunners, and six matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and two matrosses were marked as “On Furlough.” Interestingly, another two matrosses were marked as having deserted, and two matrosses were marked as “Prisoners.”

October 11th: In Hamilton’s pay book, below the table of October 4th, another weekly return table appears with this date marked.

The return table, as seen above, again records that Hamilton’s company consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, two matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and one captain-lieutenant [being James Moore], one sergeant, and two matrosses were marked as being “On Furlough.”

To the right of the date header, in place of the usual list of positions, there is a note inside the box. The note likely reads:

Drivers. 2_ Drafts_l?] 9_ 4 of which went over in order to get pay & Cloaths & was detained in their Regt [regiment]

Drafts were men who were drawn away from their regular unit to aid another, and it’s clear that Hamilton had many men drafted into his company. This note tells us that four of these men were sent by Hamilton to gather clothing for the company, and it is likely that they had to return to their original regiment before they could return the clothing. This, at least, makes the most sense (a huge thank you to @my-deer-friend and everyone else who helped me decipher this)!! In the bottom left-hand corner of the page, another note is present, however I am unable to decipher what it reads. If anyone is able, feel free to take a shot!

October 25th: Another weekly returns table appears in Hamilton’s company pay book. Once more, this table of returns was not transcribed within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

The table, as seen above, shows that Hamilton’s company still consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, it can be seen that one matross and one drummer/fifer were “Sick [but] present,” and one sergeant, two bombarders, one gunner, and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent.” Interestingly, one matross was noted as being “Absent without care”. Two matrosses were listed as “Prisoners” and again two matrosses were listed as having “Deserted.”

Underneath the table, a note is written for which I am only able to make out part. It is clear that two men from another captain’s company were drafted by Hamilton for his needs.

October 28th: Battle of White Plains — Like with Long Island, there is no primary evidence to explicitly place Alexander Hamilton, his men, or his artillery as being involved in this battle, contrary to popular belief. See this quartet of articles by Harry Schenawolf from the Revolutionary War Journal.

November 6th: Captain Hamilton wrote another certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who was injured during the attacks on July 12th. This certificate is nearly identical to the one of September 14th, and again Hamilton writes that Douglass is “intitled to the provision made by a late resolve of the Continental Congress, for those disabled in defence of American liberty.”

November 22nd: As can be seen in Hamilton's pay book, all of his men regardless of rank received payments of cash, and some men articles, on this date.

December 1st: Stationed near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General Washington wrote in a report to the President of Congress, that the British had formed along the Heights, opposite New Bunswick on the Raritan River, and notably that, "We had a smart canonade whilst we were parading our Men...." Alexander Hamilton's company pay book placed he and his men at New Brunswick in around this time (see image scans 25, 28, 34, and others) making it likely that Hamilton had been present and helped prevent the British from crossing the river while the Continental Army was still on the opposite side. In his Memoirs of My Own Life, vol. 1, James Wilkinson recorded that:

After two days halt at Newark, Lord Cornwallis on the 30th November advanced upon Brunswick, and ar- Dec. 1. rived the next evening on the opposite bank of the Rariton, which is fordable at low water. A spirited cannonade ensued across the river, in which our battery was served by Captain Alexander Hamilton,* but the effects on eitlierside, as is usual in contests between field batteries only, were inconsiderable. Genei'al Washington made a shew of resistance, but after night fall decamped...

Though Wilkinson was not present at this event, John C. Hamilton similarly recorded in both his Life of Alexander Hamilton [x] and History of the Republic [x] that Hamilton was part of the artillery firing the cannonade during this event. Though there is no firsthand account of Hamilton's presence here, it is highly likely that he and his company was involved in holding off the British so that the Continental Army could retreat.

December 4th?: Either on this date, or close to it, Alexander Hamilton’s second lieutenant, James Gilleland, left the company by resigning his commission to General Washington on account of “domestic inconveniences, and other motives,” according to a later letter Hamilton wrote on March 6th of 1777.

December 5th: Another return table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress. This table is headed, "Return of the States of part of two Companeys of artilery Commanded by Col Henery Knox & Capt Drury & Capt Lt Moores of Capt Hamiltons Com." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table, and note that Hamilton's "company had been assigned at first to General John Scott’s brigade but was soon transferred to the command of Colonel Henry Knox." They also note that the table "is in the writing of and signed by Jotham Drury...." [x]

The table, as seen above, notes part of the "Troop Strength" (as the Library of Congress notes) of Captain Jotham Drury and Captain Alexander Hamilton's men. As regards Hamilton's company, the portion that was recorded here amounted to 33 men.

December 19th: Within his Warrent Book No. 2, General George Washington wrote on this date a payment “To Capn Alexr Hamilton” for himself and his company of artillery, “from 1st Sepr to 1 Decr—1562 [dollars].” As reprinted within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

December 25th: Within Bucks County, Pennsylvania, hours before the famous Christmas Day crossing of the Delaware River by Washington and the Continental Army, Captain-Lieutenant James Moore passed away from a "short but excruciating fit of illness..." as Hamilton would later recount in a letter of March 6th, 1777. According to Washington Crossing Historic Park, Moore has been the only identified veteran to have been buried on the grounds during the winter encampment. His original headstone read: "To the Memory of Cap. James Moore of the New York Artillery Son of Benjamin & Cornelia Moore of New York He died Decm. the 25th A.D. 1776 Aged 24 Years & Eight Months." [x] In his aforementioned letter, Alexander Hamilton remarked that Moore was "a promising officer, and who did credit to the state he belonged to...." As Hamilton and Moore spent the majority of their time physically together (and therefore leaving no reason for there to be surviving correspondence between the two), there is no clear idea of what their working relationship may have looked like.

December 26th: Battle of Trenton — Alexander Hamilton is believed to have fought in he battle with his two six-pound cannons, having marched at the head of General Nathanael Greene's column and being placed at the end of King Street at the highest point in the town. Michael E. Newton does note however that there is no direct, explicit evidence placing Hamilton at the battle, but with the knowledge of eighteen cannons being present as ordered by George Washington in his General Orders of December 25th, it is highly likely the above was the case (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 179-180; Newton cites a number of sources for circumstantial evidence: William Stryker's The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, Jac Weller's "Guns of Destiny: Field Artillery In the Trenton-Princeton Campaign" [Military Affairs, vol. 20, no. 1], and works by Broadus Mitchell).

December ???: Within Hamilton’s pay book, a note appears for December on the page dedicated to Uriah Chamberlain (misnamed as “Crawford” on the page itself), a matross in his company (who is likely the same Uriah who was court martialed and punished in May). See a close up of the image scan below.

The note likely reads:

To Cash [per] for attendance during sickness [ampersand?] funeral expenses —

This note would thus indicate that Chamberlain likely passed away and a funeral was held, or attend the funeral of someone else, sometime during the month. That Hamilton paid the expenses for the funeral is quite a telling note. Chamberlain was also provided a pair of stockings in December.

Final Months - 1777:

January 2nd: Battle of Assumpink Creek — Near Trenton, the Continental Army positioned itself on one side of the Assumpink Creek to face the approaching British, who sought to cross the bridge into Trenton. In a letter of January 5th to John Hancock, Washington explained that "They attempted to pass Sanpink [sic: Assumpink] Creek, which runs through Trenton at different places, but finding the Fords guarded, halted & kindled their Fires—We were drawn up on the other side of the Creek. In this situation we remained till dark, cannonading the Enemy & receiving the fire of their Field peices [sic: pieces] which did us but little damage." According to James Wilkinson, who was present at this battle, Hamilton and his cannons were present. [x] Corroborating this, Henry Knox wrote in a letter to his wife of January 7th that, "Our army drew up with thirty or forty pieces of artillery in front", and an anonymous eyewitness account which noted that "within sevnty of eighty yards of the bridge, and directly in front of it, and in the road, as many pieces of artillery as could be managed were stationed" to stop the crossing of the British (see Raum, John. History of the City of Trenton, New Jersey, pp. 173-175). Further, another eyewitness account from a letter written by John Haslet reported a similar story (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 181; for Haslet's account, Newton cites Johnston, Henry P. The Campaigns of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn, Vol. 2, pg. 157). This surely would have been a sight to behold.

January 3rd: Battle of Princeton -- Overnight, the Continental Army marched to Princeton, New Jersey with a train of artillery. Once more, Alexander Hamilton was not explicitly mentioned to have been present at the battle, however with 35 artillery pieces attacking the British (see again Henry Knox's letter of January 7th), and the large role these played in the battle, there is little doubt that Hamilton and his men played a part in this crucial victory (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 182). According to legend, one of Hamilton's cannons fired upon Nassau Hall, destroying a painting of King George II. However, this has been disproven by many different scholars and writers, including Newton.